Paul Gilster's Blog, page 79

September 9, 2019

Internal Pressure and Planet Formation

Our thinking on how planetary systems form includes the accretion of rocky bodies within a disk surrounding a young star, and we’re examining such disks in numerous systems, such as the well studied Beta Pictoris. But the idea of accretion leaves many issues unsettled, such as what happens when large rocky bodies collide in the violent endgame of system formation. The Earth evidently underwent such a collision, with our own Moon being the tangible result.

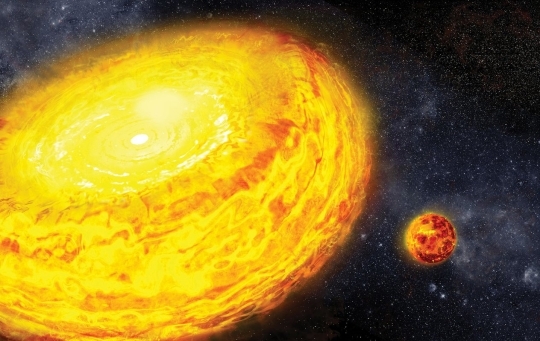

Caltech postdoc Simon Lock has been working with Sarah Stewart (UC-Davis) to study how such giant impacts unfold, running simulations of early planetary materials whose collisions can form bodies with masses between 0.9 and 1.1 Earth masses. The energy involved in such impacts is thought to allow, in some cases, the two colliding bodies to form a ‘synestia,’ or a rotating torus of planetary materials that will later cool into one or more spherical planets.

The synestia is, however, but one outcome out of many produced by these simulations. What the researchers found is that when a major collision occurs, the internal pressure of the resulting objects is much lower than we would expect. Lock explains how the computer modeling changes earlier thinking about pressure within a young planet:

“Previous studies have incorrectly assumed that a planet’s internal pressure is simply a function of the mass of the planet, and so it increases continuously as the planet grows. What we’ve shown is that the pressure can temporarily change after a major impact, followed by a longer term increase in pressure as the post-impact body recovers. This finding has major implications for the planet’s chemical structure and subsequent evolution.”

Image: Artist’s depiction of a synestia, a rotating donut of planetary material that can result from the collision of two planetary bodies. In time, the synestia cools back into one or more spherical planetary bodies. Credit: Ron Miller/Scientific American.

Lock and Stewart’s modeling indicates that the lower post-impact pressure is the result of rapid rotation induced by the collision, which could push material away from the object’s spin axis. Moreover, the now partially vaporized object is hot and its density is correspondingly reduced.

Modeling like this is important in the study of early stellar systems because we have no observational data as yet on how Earth-class planets grow, and according to this work, the physical properties of a planet as shaped by collisions are highly variable. Lower internal pressure (and the pressure inside the Earth not long after the impact that formed the Moon was, the researchers believe, half that of present-day Earth) could help us tie together geochemical analysis of the Earth’s mantle with the collision model of planet formation now current.

The paper argues that the internal pressure of a planet like ours helps to determine the chemical composition of the mantle. Objects colliding with the early Earth would have delivered metals into the mantle which, along with other elements already there, would sink to the core. By studying the amount of elements dissolved into the metal, we can determine Earth’s internal pressure at the time. Thus today’s mantle is a window into the mantle pressure at play during the planet’s formation.

The contradiction has been that studies of the metal content of the mantle show the pressure during formation would have been the same as found in the middle of the mantle today. But our models of giant impacts show that most of the mantle should melt, thus producing much higher pressure, equivalent to that found near the core. The researchers resolve the problem by showing that the pressure would be lower after these impacts, rising as the planet recovers. Evidence in the mantle should show how it solidified and how the earliest planetary crust formed. As the paper notes, this is an area that has been little explored before now:

…we show that cooling and tidal evolution of satellites after giant impacts can lead to increases in pressure. Pressure increases in the lower mantle could lead to partial melting. Pressure-induced melting provides a new mechanism for the creation of chemical heterogeneity early in Earth’s history and could explain the existence of seismologically anomalous regions in the present-day lower mantle. Pressure-induced phase transitions during the recovery of a body after a giant impact are a previously unrecognized phenomenon in planet formation.

So we have a new model, one that examines the changing nature of internal pressure in planetary bodies late in the planet-formation process. The lower average pressures that Lock and Stewart find help to explain the concentrations of elements between the core and mantle and reconcile them with the melting expected after giant impacts. The way thus opens to test various Moon formation scenarios using geochemical and geophysical observations of today’s Earth because how the mantle solidifies varies depending on the kind of impact. Adds Lock:

“We have shown that the pressures in planets can increase dramatically as a planet recovers, but what effect does that have on how the mantle solidifies or how Earth’s first crust formed? This is a whole new area that has yet to be explored.”

The paper is Lock et al., “Giant impacts stochastically change the internal pressures of terrestrial planets,” Science Advances 5 (9), 2019. Abstract/full text.

September 6, 2019

Tales from Iceland: Extreme Solar Systems IV

Reykjavik is an old haunt of mine, a favorite place to which I have not returned in all too long. I was delighted, then, to hear from Angelle Tanner, who in August attended the Extreme Solar Systems IV conference there. I had the pleasure of getting to know Dr. Tanner in Knoxville when we both spoke at a biosignatures session at the 2017 symposium of the Tennessee Valley Interstellar Workshop. Dr. Tanner received her PhD at UCLA, did postdoc work at both Caltech and Georgia State, and is now an associate professor at Mississippi State University. Her work specializes in exoplanet detection and programs devoted to understanding the properties of stars that host planets, as well as the architecture of the systems that evolve around them. It’s a pleasure to turn today’s essay over to Dr. Tanner for a look at exoplanetary events in Iceland’s capital.

by Angelle Tanner

Mid-August marked the fourth meeting of the Extreme Solar Systems conference — this one in Reykjavik, Iceland – touted as one of the biggest exoplanet-themed astronomy conferences of the year. Meetings I-III were hosted in Santorini, Greece; Jackson Hole, Wyoming and The Big Island of Hawaii – all parts of the world with extreme geology. Reykjavik was no exception, with glaciers, volcanoes and geysers within driving distance of the conference venue at the Harpa Concert Hall and Conference Center. It is a beautiful building right on the water with sharp cliffs and fishing and excursion boats in plain view.

To keep with the conference theme, I’ll cover some of the science highlights by investigating the extreme properties of exoplanets, their host stars and our own Solar System. Some of these results may sound familiar as they were announced globally via press releases that were embargoed until their presentation at the meeting.

Image: Harpa Concert Hall and Conference Center in Reykjavik. Credit: Angelle Tanner.

Common vs. Rare

As expected, planets around M-dwarfs were in full force at this meeting as we heard about exciting new discoveries on the first day. David Charbonneau (Harvard), speaking for his postdoc Jennifer Winters, told us about the complex triple M-dwarf system LTT 1445. It has a TESS-discovered transiting planet orbiting the A stellar component of the system. While the mass of the planet around LTT 1445 A still needs to be determined, the fact that it transits its M-dwarf host star makes it a good target for JWST.

We will be able to determine the composition of the atmosphere of the planet from transit spectroscopy not currently possible with ground or space-based telescopes as we can’t quite reach the necessary signal-to-noise yet. M-dwarfs constitute the majority of stars in our galaxy and have become high priority targets for planet search programs. This system will join the Trappist-1, GJ 1214 and GJ 518 M-dwarf planetary systems, to name a few which are getting plenty of attention, as we characterize each planet and further investigate these types of systems. They are not only the most common in our galaxy but may be our best chance to look for life outside of our Solar System.

At the other population extreme are those rare planets in orbits with very high eccentricities. Shasha Hinkley (University of Exeter) spoke about what could eventually be the first directly imaged hot Jupiter planet. How? Well, turns out the planet orbiting HD 20782 has an orbital eccentricity of 0.97! With an orbital period of ~600 days, the planet gets as close as 0.04 AU and as far as 2.7 AU (0.072”) from its host G1.5V star (data from exoplanet.eu).

With its widest separation of 0.07” at apastron, this planet is tantalizing close to the limit on the inner working angle of many coronagraphic systems available today like SPHERE on the VLT or GPI on Gemini. Hinkley’s team was not able to image the planet due to a little too much stellar saturation in their non-coronagraphic images, but I’m sure they will try again. They were able to determine that there are not any 20-60 MJ objects further out from the star, which makes us wonder why this planet still retains such a high orbital eccentricity.

Young vs Old

Discoveries of new planets around young stars were some of the highlights of the meeting. Young stars are problematic for planet search programs, as their tendency to be photometrically active hinders planet discovery via radial velocities, and the large distances to young stellar clusters (50 – 100 pc) requires sophisticated coronagraphic direct imaging instruments and analysis tools.

Marie LaGrange (INST) announced the detection of an additional planet around Beta Pictoris. This young star has been in the news for decades, as its edge-on debris disk was first observed with the IRAS telescope in 1983 and the planet beta Pic b, which is in an edge-on orbit but does not quite transit, was first confirmed in 2018. This time the existence of the second planet, beta Pic c, is inferred from radial velocity measurements. Getting a thorough census of the planets in this system is important to help understand planet formation and evolution and also how the planets influence the structure of the disk, which has moving clumps and is warped.

There was another announcement of the discovery of a planet (or two) around a well-known young star with an edge-on disk. Peter Plavchan (George Mason University) announced the discovery of the planets via both TESS transit photometry, and follow-up radial velocity measurements with the new iSHELL infrared echelle spectrometer on the NASA IRTF telescope. Due to the fact that the paper is still under review by Nature (I’m a co-author), the name of the host star is still hush, hush. Stay tuned!

At the other age extreme, we have the remains of dead planets being detected in the atmospheres of white dwarfs. White dwarfs have very simple spectra, with mostly just absorption lines from H and He. Over the past few years, astronomers have detected multiple heavy elements including Fe, Mg, Ca and Si. This meeting hosted a few different speakers including Christopher Manser (University of Warwick) who announced the first detection of a planetesimal orbiting a white dwarf. His team tracked changes in the shape of the Ca II line and noticed variations over a timeframe of just 2 hours. They then determined that the material causing the variations is a solid object and, therefore, is a chunk of material still in orbit around the white dwarf [see White Dwarf Debris Suggests a Common Destiny]. This is a young and super exciting sub-field of exoplanet research which allows us to study the composition of the insides of rocky planets while we are still developing new methods to study their atmospheres.

Image: Iceland’s Blue Lagoon, a popular geothermal spa. There is a volcano caldera in the background. Credit: Angelle Tanner.

Hot vs Cold

One of the hottest extrasolar planets both literally and figuratively at this meeting was Kelt 9b. At an orbital distance of 0.034 AU around an A-class star, this planet has an average surface temperature of 4050 K. The intense heat this planet is receiving from its star results in a unique set of elements detectable in its atmosphere. Enric Palle (Gran Telescopio Canarias) updated us on the Carmenes planet atmosphere survey of 25 known transiting planets. Kelt 9b is on their target list and they have detected ionized iron and titanium in the atmosphere of this super-heated planet. This survey has also detected He in the atmospheres of three different planets, which is good to know as we make plans to travel across the galaxy.

From the extremely hot to the extremely cold (kinda), Sarah Blunt discussed the detection of a planet around the G0V star HR 5183 using radial velocity measurements. Proto-doctor Blunt made some audience members groan as she mentioned that the first RV measurement in her data set was collected before she was born (1997); however, our persistence as observers has paid off as the RV signal shot up over the past few years, revealing the presence of an extremely eccentric planet at a current distance of 18 AU from the host star. It will reach a distance of 30 AU over the course of its ~74 year orbit. We again are left to ask why this planet has such a high eccentricity with no known other planets in the system and no stellar companion close enough to cause its current configuration. Additional direct imaging and Gaia astrometric measurements will give us more information about this puzzling system [see HR 5183 b: Pushing Radial Velocity Techniques Deeper into a Stellar System].

Image: An iceberg from Iceland’s Jökulsárlón, or ‘Glacier’s-River-Lagoon’. Credit: Angelle Tanner.

Bright vs. Dark

Our final set of extremes comes from pitting the bright against the dark. We start with thinking about objects which are so bright we can see them with binoculars – the Galilean moons! Laura Mayorga opened the Thursday session reminding us that there are objects in our own Solar System that we can study to help us better understand exoplanets. She looked at the phase curve of the reflected light from Io and concluded that we need to stop using Lambertian curves (consider a cueball) to model reflected light curves. She also determined that an Earth-sized planet with a surface similar to Io would have a reflected light contrast of 10-9 to 10-10. This is indeed the contrast ratio being targeted by upcoming space missions such at LUVOIR and the Origins telescope, intent on direct imaging of Earth-like worlds. While we’ve known these contrast values are necessary for future direct imaging missions it is still useful to have observational confirmation and new phase curves for direct comparisons to future data sets.

We finish with one of the biggest announcements of the meeting, as Laura Kreidberg gave an exciting talk about measuring the first thermal phase curve of a terrestrial planet. Her team observed the transiting planet, LHS 3844 b with the Spitzer Space Telescope. Over the course of the planet’s very close 0.006 AU orbit around the M-dwarf host, Spitzer can detect changes in the amount of infrared light from the planet as seen here in our Solar System similar to the change in the phase of Venus we see on Earth as we both orbit the Sun [see LHS 3844b: Rocky World’s Atmosphere Probed].

From the significant amplitude of the change in thermal emission over the planet’s orbit, we can infer that this planet not only lacks any appreciable atmosphere but is most likely composed of a dark, basaltic rock like the moon and Mercury. In this golden age of exoplanet science, we are not only detecting and characterizing the atmospheres of extrasolar planets now but are now making informed assertions on the composition of the surface materials!

There were two other results that caught my attention but could not be cleverly placed in the context of extremes. Eric Nielsen (Stanford) and a few other folks reported on the statistical results of direct imaging programs like GPI and SHINE. There appears to be a difference in the types of stars that have planetary companions on wide orbits versus those with brown dwarfs.

Stars with masses > 1.5 Msun are more likely to host planetary mass companions, which suggests these objects were formed via the core accretion mode of planet formation. Brown dwarfs, on the other hand, seem to form more around stars < 1.5 Msun, favoring the gravitational instability planet formation model. These trends are observed from their 300-star GPI direct imaging survey.

Finally, Lisa Kaltenegger (Cornell University) stayed true to her appointment at the Carl Sagan Institute and went way out there with a trip into alien oceans. She talked about the different depths to which light would penetrate the oceans on a habitable planet around early vs late-type stars. The light from an M-dwarf star, mostly in the infrared, would penetrate only the top few meters of an alien ocean, while light from an F-type star would make it into deeper depths.

Most intriguing was her suggestion that life in some of these M-dwarf worlds would need to somehow break down the UV light expected from the flares that are common for these types of stars. Recall that the habitable zone for M-dwarfs can be a fraction of an AU and well within the reach of life-damaging flares. She then showed a cool animation of the surface of an alien world fluorescing in reaction to a UV flare, which made us all wonder if this could one day be detectable from own humble world [see Looking for Life Under Flaring Skies].

This was a small sample of the menagerie of juicy exoplanet news covered during a subset of the talks presented at this meeting. There were also a few hundred posters covering anything from new planets to new instruments to upcoming NASA exoplanet missions. The best is yet to come! There has been no news yet about the location of Extreme Solar Systems V… I’m rooting for New Zealand!

September 4, 2019

Looking for Lurkers: A New Way to do SETI

SETI, the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence, has kept its focus on the stars, through examination of electromagnetic wavelengths from optical to radio signals. But Jim Benford has been advocating that we consider near-Earth objects as potential SETI targets, prompted by Ronald Bracewell’s thoughts in a 1960 paper advancing the ‘sentinel hypothesis.’ A Bracewell probe could linger in a target system for millions of years, monitoring developments on worlds with the potential for life. Couple that thought with the rarely studied co-orbital’ objects that approach the Earth both frequently and closely and you have a map for a realm of SETI that is only now coming into investigation.

What follows is a news release from The Astrophysical Journal covering Benford’s new paper, one we discussed on Centauri Dreams back in March [see A SETI Search of Earth’s Co-Orbitals]. I want to get this out now because Benford will be delivering the 2019 Eugene Shoemaker Memorial Lecture tomorrow, Thursday September 5, at 1900 MST (0100 UTC). The lecture, at Marston Exploration Theater in Tempe, AZ can be accessed online at https://asunow.asu.edu/asulive. For those not familiar with it, the Shoemaker Lecture has been set up by the BEYOND Center for Fundamental Concepts in Science as a special award to a leading scientist to honor the life and work of Eugene Shoemaker who, together with his wife Carolyn, pioneered research in the field of asteroid and comet impacts.

The most recently discovered group of rocky bodies nearby Earth are termed co-orbital objects. These may have been an attractive location for extraterrestrial intelligence (ETI) to locate a probe to observe Earth throughout our deep past. Co-orbital objects approach Earth very closely every year at distances much shorter than anything except the moon. They have the same orbital period as Earth. These near-Earth objects provide an ideal way to watch our world from a secure natural object. Co-orbitals provide resources an ETI might need: materials, constant solar energy, a firm anchor, concealment.

Co-orbitals have been little studied by astronomy and not at all by SETI or planetary radar observations. James Benford has proposed both passive and active observations of them as possible sites for ET probes that may be quite ancient.

A ‘Lurker’ is a hidden, unknown and unnoticed observing probe. They may respond to an intentional signal and may not, depending on unknown alien motivations. Lurkers would likely be robotic, like our own Voyager and New Horizons probes.

Long-lived robotic lurkers could have been sent to observe Earth long ago. As they would remain there after their energy supply runs out, this is extraterrestrial archaeology. If we find nothing there, this gives us a profound result: no one has come to look at the life of Earth, which has been evident in our atmosphere’s spectral lines over interstellar distances for over a billion years.

Co-orbitals are attractive targets for SETI searches because of their proximity. Benford thinks we should move forthrightly toward observing them, both in the electromagnetic spectrum of microwaves and light, and planetary radar. And we can visit them with probes. The most attractive target is ‘Earth’s Constant Companion‘ 2016 HO3, the smallest, closest, and most stable (known) quasi-satellite of Earth. Getting there from Earth orbit requires little rocket propulsion and can be done in short trips. China has announced they are going to send a probe to 2016 HO3.

The well-regarded astronomy journal of record, Astrophysical Journal, is publishing Benford’s paper “Looking for Lurkers: Co-orbiters as SETI Observables” in the near future.

This is the latest in an agenda Benford has carried out in imaginative searches for interstellar communication. His first work with other family members yielded the term ‘Benford Beacons’—short microwave bursts to attract attention, like lighthouses. Later he pointed out the uses of powerful electromagnetic beams to send light spacecraft, ‘sails’, in interplanetary exploration. His Lurkers proposal moves on to actual relic alien spacecraft that may have been nearby for longer than humans have existed.

Interstellar travel is challenging – no craft engineered by humans has yet traveled further than the outskirts of our own Solar System. One project working to change that is Breakthrough Starshot, which aims to send a gram-sized spacecraft to a nearby star system at around 20% of the speed of light. “Within the next few decades we hope humanity will become an interstellar species,” remarked Breakthrough Initiatives Chairman Dr. Pete Worden. “If intelligence arose elsewhere in our galaxy, it may well have sent out similar probes. It’s intriguing to think that some of these may already have reached our own Solar System.”

The paper is Benford, “Looking for Lurkers: Objects Co-orbital with Earth as SETI Observables,” soon to be published by the Astrophysical Journal (preprint). To attend Benford’s lecture at the University of Arizona online, the address is https://asunow.asu.edu/asulive.

September 3, 2019

Spectroscopic Evidence of a Possible Exomoon

It shouldn’t surprise us that first discoveries can be extreme. Consider that the first main sequence exoplanets we detected were ‘hot Jupiters.’ Nobody expected these (unless you discount John Barnes and Buzz Aldrin in Encounter with Tiber, and Greg Matloff, who advised them — see Probing Ultrahot Jupiters — but a radial velocity detection is rendered far more likely if a large planet is orbiting close to its star. And so we got 51 Pegasi b, and soon, others in the hot Jupiter category. Incidentally, the Barnes & Aldrin novel was finished though not published when the discovery of 51 Pegasi b was made in 1995. Nice prediction!

Hot Jupiters may not be all that common, but they show up in early radial velocity work. I could throw in the first exoplanets of another kind as well, these being planets around a pulsar. Who, as Isidor Rabi once said about muons, ordered that? Extreme objects that push hard enough on their environment to be flagged by our current instrumentation are of course what we will see first. We then start widening our capabilities and building our catalogs.

Now we have interesting work on a possible exomoon, a kind of Io (itself an extreme object, as witness the contortions of its surface) that seems to be shedding material at a fantastic rate. Remember, Io has more volcanic activity than any body in the Solar System, and thus an Io analog elsewhere might well do the same. But untangling this spectral signature’s import is no small matter, and the paper’s authors are forthright about sharing the uncertainties.

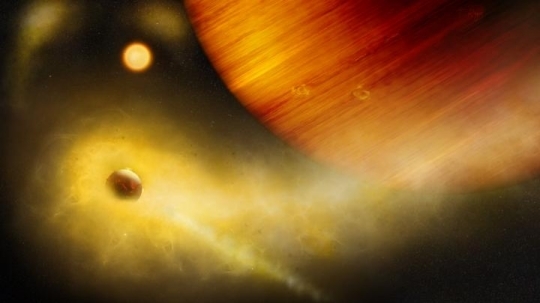

Image: Artist’s composition of a volcanic exo-Io undergoing extreme mass loss. The hidden exomoon is enshrouded in an irradiated gas cloud shining in bright orange-yellow, as would be seen with a sodium filter. Patches of sodium clouds are seen to trail the lunar orbit, possibly driven by the gas giant’s magnetosphere. Credit: © University of Bern, Illustration: Thibaut Roger.

The system in question is WASP-49, a G-class star about 555 light years out in the constellation Lepus near Orion, which is circled by the transiting gas giant planet WASP-49b in an orbit of less than three days at a distance of 0.0379 AU. The prospect of an exo-Io in turn orbiting this world has Apurva Oza, a postdoctoral fellow at the Physics University of Bern and associate of NCCR PlanetS, speaking of the place in apocalyptic, or at least cinematic, terms:

“It would be a dangerous volcanic world with a molten surface of lava, a lunar version of close-in Super Earths like 55 Cancri-e, a place where Jedis go to die, perilously familiar to Anakin Skywalker.”

Oza is lead author of the paper on this work, which is a study of sodium and tides. It’s also a tale of circumstantial evidence, so that we have to keep in mind that we have no discovery of an exomoon here, but rather hints that something unusual is happening in this system that an exomoon could explain. That something would be the effect of enormous tides that, if an exomoon exists around WASP-49b, would heat the moon to stress and reinforce its own volcanic activity, spewing sodium and potassium into space. Both sodium and potassium are useful because they create distinct spectral signatures, and sodium has been detected in the spectra of other exoplanets, but nowhere so far from the planet itself as at WASP-49.

In other words, we could be looking at a geologically active moon interacting with ambient plasma. If sodium is being drawn from an exomoon’s surface, we would expect it to contribute to a plasma torus, according to the authors, because volatiles are being fed into the magnetosphere of the gas giant. The paper uses the Jupiter/Io system as a benchmark to model the sodium torus, noting that about a dozen exoplanet systems show similar detections.

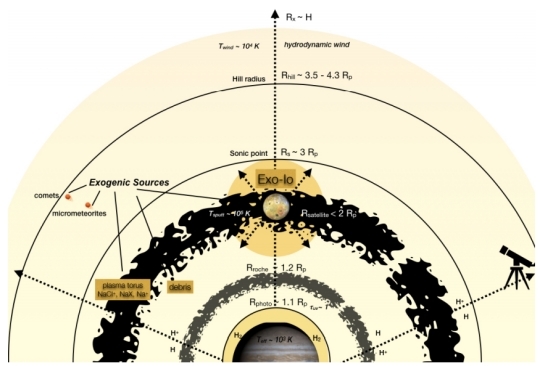

The authors use the term endogenic to describe processes that are intrinsic to the gas giant planet, while processes that are external — i.e., related to a moon or debris ring near the planet — are referred to as exogenic. Distinguishing between these sources is difficult, as the scientists acknowledge, but based on recent observations of sodium at Jupiter, the spectral signature of sodium shows a clear origin at Io. Thus the idea that a similar moon might contribute to the spectral signature at WASP-49b seems reasonable, and here, the sodium is far enough away from the planet to indicate an external source. From the paper:

A unique consequence of exomoons orbiting hot Jupiters is that they would be directly embedded in the hydrodynamically escaping endogenic medium rendering the distinction between the two difficult at present. However, the recent discovery of Na I at a remarkably high altitude RNa ∼ 1.5Rp for WASP 49-b (Wyttenbach et al. 2017) we discuss may be a strong indication of exogenic sodium [i.e., sodium drawn from the surface of a moon], although not unambiguous at present. Further testable predictions as we have described include non-solar Na/K ratios, and spectral shifts due to radiation pressure.

Thus we see sodium from both planet and possible exomoon, but the distance between the sodium signature and the planet gives credence to the idea that the primary source is a moon. The image below shows the concept.

Image: This is Figure 4 from the paper. Partial caption: 2-D “Birds-Eye” Architecture of a Sodium Exosphere at a Close-in Gas Giant Exoplanet System. Endogenic: An extended sodium layer above the hot Jupiter is shown to illustrate a well-mixed Na I component (yellow). Exogenic: An exo-Io sodium cloud (yellow) is shown at ∼ 2Rp. Parameters for an escaping atmosphere are overlayed, inspired by the 1-D hot Jupiter atmosphere by Murray-Clay et al. (2009). Several other desorbing-exogenic sources (comets, micrometeorites, debris) illustrate the possible endogenic-exogenic interaction contributing to the light yellow exosphere. A full Monte Carlo simulation is likely necessary to describe the precise ion-neutral and electron-neutral interactions in detail, yet a upper atmosphere model by Huang et al. (2017) along with high-resolution observations of HD189733b (Wyttenbach et al. (2015)) and WASP 49-b (Wyttenbach et al. (2017)) are suggestive of the parameter space. Credit: Oza et al.

But is it likely that a moon could survive in this configuration, orbiting a hot Jupiter this close to its star? The authors concede the possibility that we are looking at the remnants of a disintegrated moon, but add that we can’t discount a stable orbit here:

Survival of an exo-Io should,,,be considered in tandem with its mass loss, as orbital stability dependent on semimajor axis is a necessary yet insufficient condition. Although the stellar proximity and insolation is threatening for the above systems, we find that, for the majority of systems, the stellar tides not only force the exo-Io to remain in orbit, but also drive significant tidal heating within the satellite, roughly 5 orders of magnitude higher than Io.

Thus if Io’s escaping sodium can dominate Jupiter’s own emission of sodium, the possibility that the WASP-49b detection is the signature of an exomoon cannot be ruled out. The authors make the interesting point that the physical processes they describe in this paper can expand material to the edge of the magnetosphere in a gas giant system, which means that we need to consider exoplanets in a larger context, as part of an exoplanetary system that may include moons. And while we have no clear detection of such a moon here, we have intriguing hints of the possibility, and a research direction that includes the effects of nearby objects in these environments.

The paper is Oza, “Sodium and Potassium Signatures of Volcanic Satellites Orbiting Close-in Gas Giant Exoplanets,” accepted at The Astrophysical Journal (preprint).

August 30, 2019

Is Enceladus Prebiotic?

Centauri Dreams regular Alex Tolley here examines a new paper with a novel take on Saturn’s moon Enceladus. Tempting us with its geysers and the organic compounds Cassini detected in their spray, Enceladus offers the prospect of life within its internal ocean. But are there other explanations for what we see, pointing to what may be a prebiotic environment? For that matter, what features of life’s chemistry could emerge on such a world without yet maturing into what we would recognize as living organisms? The paper Alex examines offers us quite an interesting take on a possible origin for life not just on Enceladus but elsewhere in the universe.

by Alex Tolley

Image: “Snow on Enceladus.” Credit: David Hardy.

The discovery of subsurface oceans in the icy moons of Europa and Enceladus has increased interest in the exploration of these moons. The logic of the mantra “Follow the water” implies that there may be extant life in these oceans, most excitingly from a unique genesis at hypothesized ocean hot vents that release the tidal heat. The Europa Clipper is one such Probe.

A new review article published in Astrobiology by Amit Kahana (Weizmann Institute of Science, Israel) and colleagues makes a case that rather than being biotic, Enceladus is prebiotic, a state such as has been speculated on Titan. As the authors state:

The enceladan subglacial ocean appears to be the first observationally discovered concrete example of what may well be a primeval soup.

They come to this conclusion via a chain of logic which follows.

The first piece of evidence is that the Cassini probe detected organic compounds in the plumes of Enceladus and Saturn’s rings. This should not be surprising as we might expect organic compounds as they are common on icy bodies like comets, which include the primordial compounds that can be converted to compounds that are presumed to be the basic building blocks of life on Earth. They tabulate 53 compounds identified in space, most of which are organic with up to 10 carbon atoms. There is also abundant insoluble organic matter (IOM), like kerogens that can be broken down into small molecules. The authors interpret the Cassini data to suggest the detected organic compounds may have up to 150 carbon atoms, similar in composition to the IOM detected elsewhere. The authors believe that the these organics are rich in carbon and hydrogen, and depleted in oxygen and nitrogen. This indicates methane and other alkanes, longer chain organics or aromatics, rather than the mix of organics that might be expected if life was extant..

On the other hand, the observations are consistent with a predominance of relatively long unsaturated hydrocarbon chains, aliphatic or aromatic, with a small number of polar heteroatoms.

The authors take pains to suggest that the origin of life research is dependent on the primordial compound mix and the energy sources to transform them to prebiotic compounds. For example, they counter the requirements of the classic Miller-Urey experiment that added electrical energy to reducing gas mixtures to create amino acids. They contrast the results of this experiment with the speculated abundance and composition of organics in the plumes of Enceladus to suggest other means of production. These organics could have been delivered by comets, or created de novo within Enceladus, beneath a thick ice crust, a very different environment from that on the early Earth. The authors paint a picture that favors Oparin’s primordial soup model in which heterotrophic early life feeds off the energy in the organic molecules in this soup. [Heterotrophic life consumes these “soup” compounds, rather than autotrophic life, such as methanogens which consumes inorganic CO2 and hydrogen to extract the energy from methane (CH4) synthesis, as we see in many Archaea extremophiles.]

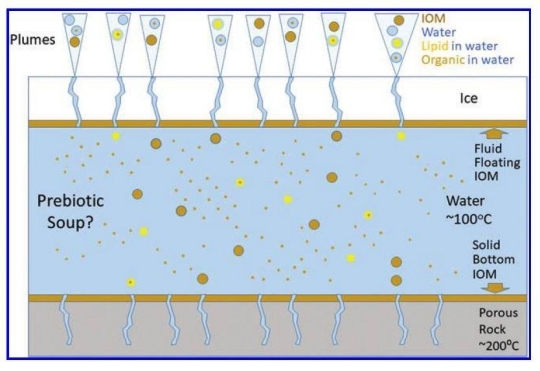

A primordial soup is the model they have of Enceladus, with organics delivered by infall, with perhaps a rich layer of IOM between the ocean surface and the ice crust above (see figure 1 below).

If the ocean contains mainly high molecular weight organic material, then how are the lower molecular weight organics created? Experimental work suggests that it is the energy, and possibly mineral catalysts, at the hot vents that convert the IOM to the smaller molecules:

In parallel, high-temperature hydrous pyrolysis experiments of solid fossil fuels such as kerogen and bitumen, in the presence or absence of mineral catalysts, gave rise to a plethora of low-molecular-weight organics. The products included alkanes, alkenes, and isoprenoids (Huizinga et al., 1987) as well as long-chain fatty acids (Kawamura et al., 1986; Siskin and Katritzky, 1991). In another set of studies, hydrous pyrolytic degradation of petroleum sediments (kerogen) has been examined both in hydrothermal vents and in the laboratory (Leif and Simoneit, 1995). A major set of products constituted amphiphilic n-alkanones with chain lengths from C11 to C33. A similar set of results showed how hydrothermal pyrolysis leads to the formation of diverse polar compounds, including alkanoic acids and alcohols, isoprenoid ketones, and alkanoate esters, in the C9–C33 range (Rushdi and Simoneit, 2011). All these results are consistent with the possible generation of monomeric organics from insoluble polymers under conditions similar to those prevailing on Enceladus. Whether this actually happens on Enceladus could only be verified by future missions and analyses.

The authors’ model is that of an ocean rich in organics primarily from impactors. Much of this material is IOM. The silicate material detected in the plumes infers that there are hot vents on the ocean bottom that help break down the IOM into simpler, C, H rich molecules, which can then form the lipid membranes of micelles and vesicles. It is the mix of vent emissions and these lipids and IOM that Cassini detected in the plumes. The apparent paucity of nitrogen and oxygen in the plume organics leads the authors to suggest that the compounds likely have an abiotic origin, although they do not rule it out:

However, in the absence of evidence to the contrary, a biotic origin of Enceladus’ organics remains a remote possibility (Postberg et al., 2018).

Figure 1. Enceladus cross-section, showing the different potential components of the soup and the plumes. IOM stands for insoluble organic matter, which is taken to be synonymous with nondispersive organic matter. Such polymeric compounds can still be carried in the plume as small particles detached from insoluble organic layers at the top of the water layer. Lipid in water alludes to monomers and aggregates such as micelles and vesicles. Organic in water is dispersed, for example as a microemulsion. Inspired by the data in Postberg et al. (2018).

Figure 1 above shows the authors’ model of the organic chemistry of Enceladus.

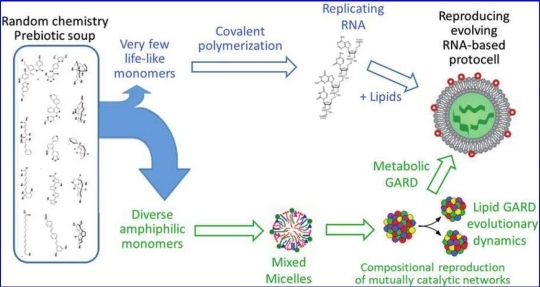

Given the authors’ assumption that abundant lipids exist, and that they have a mechanism for creating them, what does this mean for abiogenesis and life? The two most dominant theories for the origin of life are the RNA First and Metabolism First theories. Both can exist without surrounding cell walls to contain either the RNA (as both catalysts and information molecules) or the metabolites for autocatalytic sets. However, some form of concentration and protection from degradation is eventually needed, and terrestrial life used lipid membranes to provide that solution. However, there are other theories, and Lipid First is more akin to the idea that lipids can form mono and bilayer membranes that can then encapsulate the metabolisms and replication machinery of the protocells. In such a world, we might expect to see vesicles or coacervates that concentrate the needed components for the transition to life.

The authors argue that the best origin of life model is one that fits with the observed chemical environment, rather than with a predetermined set of molecules and energy sources such as the Miller-Urey experiment required. They use their speculated set of lipid precursors to define the organic soups and from this favor the Lipid World hypothesis. In other words, having built up a case for long-chain unsaturated carbon molecules from their interpretation of the data, they use this as the given compound environment to base their origin of life scenario. They then argue that cell reproduction occurs by membrane splitting and that information about the membranes was added by the later incorporation of informational molecules like RNA. Thus their Lipid World would predate the RNA world and Metabolism World in this scenario.

Assuming that the authors are correct and Enceladus’s ocean contains a “Lipid World”, the next question they ask is this even prebiotic? It is generally accepted that lipids can form abiotically and organize into vesicles or micelles. Can the lipid membranes help catalyze reactions? A paper very recently published [1] suggests that amino acids can bind to lipid membranes, both stabilizing them and providing the means to catalyze reactions such as peptide formation. This would then allow the concentration of metabolites into these protocells. The experimental results from this paper would support a Lipid First model of the origin of life.

Figure 2. From soup to protocells, delineating the underpinnings of two different models, RNA First (RF, top) and Lipid First (LF, bottom). In RF, specific monomers are singled out from a heterogeneous chemical mixture and undergo polymerization, culminating in the emergence of a self-replicating polymer. This is then enclosed in a lipid bilayer, leading to protocells capable of selection and evolution. In LF, a large variety of amphiphiles spontaneously generates a plethora of assemblies, for example, micelles. The GARD model then predicts that very specific micellar compositions establish a mutually catalytic network, which may exhibit homeostatic growth. This, when followed by fission events, constitutes a reproduction system, capable of selection and evolution (see ‘‘How do lipids reproduce?’’ Section 8.4 and Lancet et al. [2018]). Subsequent prolonged evolution may lead to the emergence of RNA, proteins, and metabolism (See Section 8.5, ‘‘How would lipids beget full-fledged protocells’’ and Lancet et al. [2018] Section 11.1). Caption source: Kahana et al.

Figure 2 above shows the authors’ view of the Enceladus Lipid World hypothesis that would culminate in prebiotic protocells, but not fully living cells.

If their hypothesis is correct, then Enceladus is in a prebiotic state. The components to start life may be present, but mostly concentrated in protocells, but not in any form that we would call life. They may show some features of life, such as motility and replication by division, but no true metabolism to liberate energy for growth and reproduction, nor the information molecules needed to encode the instructions that can evolve under natural selection to drive these protocells to transition to living cells. Such a state would still be a fascinating one for study as it would offer a prebiotic environment that has long been lost to us once life emerged on Earth.

However, it should be borne in mind that their argument is based on a chain of logic. Any link that proved false could break that chain. The organic material may not be as depleted in nitrogen and oxygen as inferred. The organic material in the plumes may not be as complex as believed. The ocean may not have a lot of IOM as a feedstock, and reactions may not result in lipid chains, but rather a mix of different molecular weight organics, both linear and aromatic. The organics may therefore be primordial rather than prebiotic. The Cassini data are tantalizing and beg for further missions to elucidate the nature of this moon. Hopefully we may get further clues from the Europa Clipper mission.

The paper is Kahana A et all “Enceladus: First Observed Primordial Soup Could Arbitrate Origin-of-Life Debate”, Astrobiology v12 (10) 2019. Full Text.

References

1. Caitlin E. Cornell, Roy A. Black, Mengjun Xue, Helen E. Litz, Andrew Ramsay, Moshe Gordon, Alexander Mileant, Zachary R. Cohen, James A. Williams, Kelly K. Lee, Gary P. Drobny, and Sarah L. Keller. Prebiotic amino acids bind to and stabilize prebiotic fatty acid membranes. PNAS 116 (35), (27 August, 2019), 17239-17244 (abstract).

August 29, 2019

A Major Step for the James Webb Space Telescope

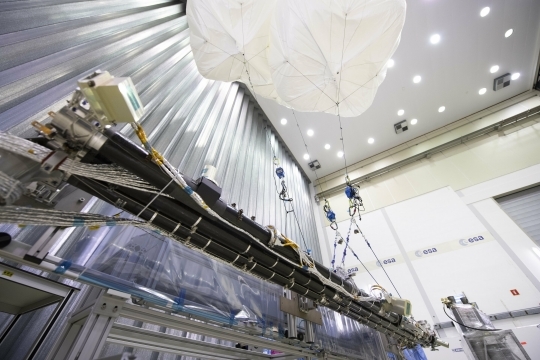

The James Webb Space Telescope has been assembled for the first time, meaning its two halves — the spacecraft and the telescope — have been connected, following up earlier testing in which the two parts were temporarily connected by ground wiring. The latter took place almost a year ago, in September of 2018, allowing spacecraft and telescope test teams to begin working together as the process pointed to the physical connection that has now been achieved.

The connection was completed at Northrop Grumman’s facilities in Redondo Beach, California, with the telescope, its mirrors and science instruments, lifted by crane above the sunshield and spacecraft, which had already been combined. With the mechanical connection complete, the next step will be the electrical connection of the two halves and subsequent testng.

Image: The fully assembled James Webb Space Telescope with its sunshield and unitized pallet structures (UPSs) that fold up around the telescope for launch, are seen partially deployed to an open configuration to enable telescope installation. Credits: NASA/Chris Gunn.

“This is an exciting time to now see all Webb’s parts finally joined together into a single observatory for the very first time,” says Gregory Robinson, the Webb program director at NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C. “The engineering team has accomplished a huge step forward and soon we will be able to see incredible new views of our amazing universe.”

The next round of testing includes full deployment of the JWST sunshield. Its critical role: To keep the observatory’s mirrors and scientific instruments cold to allow its infrared observations to achieve maximum resolution. The sunshield, layered in five sections, will have one side, facing the Sun, that can reach 383 Kelvin (110 degrees Celsius), while the other side has a modeled minimum temperature of 36 Kelvin, or -237 degrees Celsius. And it’s big, measuring 21.197 m x 14.162 m (this makes it about the size of a tennis court, a fact I throw in for those Centauri Dreams readers who enjoy sports comparisons in relation to space topics).

Image: Integration teams carefully guide Webb’s suspended telescope section into place above its Spacecraft Element just prior to integration. Credit: NASA/Chris Gunn.

The sunshield should allow the telescope, once at the L2 Lagrangian point, to cool down below 50 Kelvin (-223 degrees Celsius) by simply radiating its heat into space. This will allow successful functioning of the near-infrared instruments, which include the Near Infrared Camera (NIRCam), the Near InfraRed Spectrograph (NIRSpec) and the Fine Guidance Sensor / Near Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph (FGS/NIRISS) — all of these work at 39 K (-234°C). The Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) will operate at 7 K (-266 degrees Celsius) using a cryocooler system. Thermal stability will allow proper alignment of the primary mirror segments.

Image: NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, post-integration, inside Northrop Grumman’s cleanroom facilities in Redondo Beach, California. Credit: NASA/Chris Gunn.

With launch scheduled for 2021, extensive environmental and deployment testing will now be undertaken for the fully assembled observatory. All of the telescope’s major components have gone through rounds of environmental tests including launch stress and vibration, but we now have to put the integrated assembly through its paces. As if launch wasn’t stressful enough, we’ll have to sweat out deployment of the sunshield and the 6.5-meter primary mirror, all destined for Earth-Sun L2, which is far beyond the orbit of the Moon. Plenty of suspense ahead as we tune-up for 2021. Getting this expensive bird in place is going to be a nail-biter.

August 28, 2019

HR 5183 b: Pushing Radial Velocity Techniques Deeper into a Stellar System

Radial velocity methods for detecting exoplanets keep improving. We’ve gone from the first main sequence star with a planet (51 Pegasi b) in 1995 to over 450 planets detected with RV, a technique that traces minute variations in starlight as a star nudges closer, then further from us as it is tugged by a planet. Radial velocity, then, sees gravitational effects while not directly observing the planet, which may in some cases be studied by its transits or direct imaging.

Image: 51 Pegasi b, also called “Dimidium,” was the first exoplanet discovered orbiting a star like our sun. This groundbreaking find in 1995 confirmed that planets around main sequence stars could exist elsewhere in the universe. Credit: NASA.

Transit methods have accounted for more planets, but radial velocity techniques are increasingly robust and continue to provide breakthroughs. Consider this morning’s news about HR 5183, which is now known to be orbited by a gas giant designated HR 5183 b. Astronomers at the California Planet Search have employed data from Lick Observatory in northern California, the W. M. Keck Observatory in Hawaii and McDonald Observatory in Texas to identify the planet around a star they have been studying since the 1990s. Even now, they do not have data corresponding to a single full orbit of the planet.

Thus the inherent dilemma of radial velocity work: To analyze Doppler data, observations taken over a planet’s entire orbital period are optimal, but as the distance between planet and host star widens, a full orbit can take decades or even centuries. But with data on a timescale of decades, the California Planet Search team identified this one because of its odd orbit. Andrew Howard (Caltech), who leads the effort, points to the unusual nature of its motion:

“This planet spends most of its time loitering in the outer part of its star’s planetary system in this highly eccentric orbit, then it starts to accelerate in and does a slingshot around its star. We detected this slingshot motion. We saw the planet come in and now it’s on its way out. That creates such a distinctive signature that we can be sure that this is a real planet, even though we haven’t seen a complete orbit.”

Just how HR 5183 b got into such an interesting orbit is an intriguing question, one that is most likely answered by gravitational interactions with a planet of roughly the same size. The scenario: One planet is pushed out of the system to become a ‘rogue’ planet without a star, while HR 5183 b is forced into the orbit we observe, one that takes somewhere between 45 to 100 years to complete. Needless to say, we have nothing like this in our Solar System, but the new world reminds us how a system can be shaped by encounters between giant planets.

Moreover, there is an interesting twist here, a possible stellar companion that the authors have identified in the form of HIP 67291, a K-class star on the order of 15,000 AU from HR 5183. At this distance, the companion star is too far away to affect HR 5183 b, but it has to be included in any discussion of this system’s evolution. From the paper:

The extreme eccentricity and decades-long orbital period of HR 5183 b, coupled with the existence of a widely separated, eccentric stellar companion…raise interesting questions about the system’s formation. High eccentricity is a signature of past dynamical interactions (Dawson et al. 2014). Moreover, recent dynamical simulations by Wang et al. (2018) revealed that systems hosting multiple young massive planets, presumably near their formation locations, are likely unstable on Gyr or shorter timescales. Therefore, the HR 5183 system might have initially contained multiple massive planets with moderate eccentricities.

All of which backs the theory of a slingshot effect, with one planet coming close to the other and, in Howard’s words, coming “in like a wrecking ball, knocking anything in its way out of the system.”

We’re also reminded that radial velocity methods are now moving deeper into stellar systems, helping us to learn about planets that do not necessarily transit but leave their signature on the host star’s motion. The paper goes on to point to another system, HR 8799, which contains at least four massive planets whose orbital motion was confirmed by direct imaging.

Planet-planet interactions in such a system could have ejected some planets and transferred angular momentum to the remaining planet(s), pumping their eccentricities. If this is true, the HR 5183 system could be viewed as the “fate” of systems like HR 8799. Dynamical work aiming to distinguish between this and other possible formation scenarios (for example, potential past interactions with HIP 67291) would be an excellent avenue for future studies. It will be interesting to learn whether HR 5183 b represents the eventual evolution of multiple giant planet systems like HR 8799, or if it is in a class all its own.

So radial velocity finds its way into a previously unexplored parameter space, the realm of long-period gas giants on eccentric orbits. Usefully, HR 5183 b is a candidate for future detection through high-contrast imaging and stellar astrometry, which would make it possible to measure its mass directly. The authors believe the planet will be detectable in data from Gaia, ESA’s space observatory designed to use astrometry to measure the positions and motions of stars with the highest precision yet. We’ll be hearing a good deal more about HR 5183 b.

The paper is Blunt et al., “Radial Velocity of an Eccentric Jovian World Orbiting at 18AU,” accepted at The Astronomical Journal (preprint).

August 27, 2019

Upwelling Oceans: Modeling Exoplanet Habitability

We usually talk about habitability in binary form — either a planet is habitable or it is not, defining the matter with a ‘habitable zone’ in which liquid water could exist on the surface. Earth is, of course, the gold standard, for we haven’t detected life on any other world.

But it is conceivable that there are planets where conditions are more clement than our own, as Stephanie Olson (University of Chicago) has recently pointed out. The work, presented at the just concluded Goldschmidt Geochemistry Congress in Barcelona, models circulatory patterns in oceans, some of which may support abundant life if they exist elsewhere. The emphasis here is not so much on surface ocean currents but upwelling water from deep below. Says Olson:

“We have used an ocean circulation model to identify which planets will have the most efficient upwelling and thus offer particularly hospitable oceans. We found that higher atmospheric density, slower rotation rates, and the presence of continents all yield higher upwelling rates. A further implication is that Earth might not be optimally habitable–and life elsewhere may enjoy a planet that is even more hospitable than our own.”

All this has implications for how we use the term ‘Earth-like,’ and reminds us to be careful, as Olson told a Los Angeles Times interviewer in 2018:

“The phrase Earth-like does not refer to a planet that necessarily resembles modern-day Earth at all… It’s actually a very broad term that encompasses a broad variety of worlds. It includes hazy worlds like the Archean; it includes icy worlds like the ‘snowball Earth’ intervals; it includes anoxic worlds with exclusively microbial ecosystems; it includes worlds with complex and intelligent life; and it includes worlds that we haven’t even seen yet.”

Image: Geophysicist Stephanie Olson. Credit: University of Chicago.

Stephanie Olson makes the case that life has to be far more common than what we can detect at our current stage of technology. An ecosystem beneath the surface of an icy moon may defeat our methods, as could microorganisms deep within a planet’s mantle. So what we need to do, in this scientist’s view, is build our target lists for future study around a subset of planets, those that meet the habitability demands of forms of life that are global, active and detectable. This also builds the list of those worlds for which a non-detection would be the most telling.

In general, our developing models for habitability have tracked our interest in finding atmospheric biosignatures, for we are closing in on the capability of doing this for small, rocky worlds circling nearby M-dwarf stars. The complexities of ocean dynamics have been left out of the picture other than when used as a mechanism for climate regulation or heat transport.

In her conference abstract at the Goldschmidt conference, Olson argues that the implications of circulatory patterns in oceans should be folded into the habitability question. Cycles of ocean upwelling driven by winds can recycle nutrients from the deep ocean back to shallower waters where they can play a role in stimulating photosynthesis. From the abstract:

Photosynthesis,,,provides energy in the form of chemical disequilibrium that sustains life more broadly on our planet. Ocean circulation is thus a first-order control on the productivity and distribution of life on Earth today and throughout our planet’s history. Moreover, ocean circulation patterns, sea ice coverage, and sea-to-air gas exchange kinetics modulate the extent to which biological activity within the ocean is communicated to the atmosphere. The chemical evolution of Earth’s atmosphere has ultimately been an imperfect reflection of the evolution of Earth’s marine biosphere owing to these oceanographic phenomena.

Models of Habitability

Olson’s tool for exploring ocean dynamics on a range of modeled, habitable exoplanets is a global circulation model (GCM) called ROCKE-3D. The software is designed to examine different periods in the evolution of terrestrial-class planets, with the goal of finding what kind of techniques might flag the presence of life in these environments. You can have a look at ROCKE-3D in action in this NASA page on the simulation of planetary climates. Different parameters can be selected on a form to create maps of a number of climate variables.

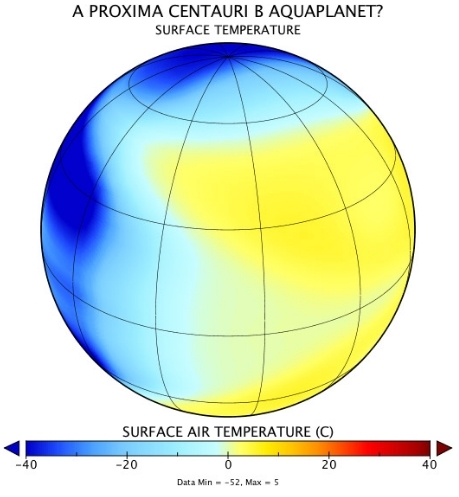

Below is an example of one of these maps, as created by the ROCKE-3D software.

Image: The discovery of the planet Proxima Centauri b orbiting the star closest to Earth has generated much research about whether it has a chance to be habitable. With ROCKE-3D we have imagined Proxima Centauri b as an “aquaplanet” covered by water. Because the planet is close to its star, it may show the same face to the star all the time, as the Moon does to the Earth. If so, the dayside remains a few degrees above freezing (yellow colors). Elsewhere, the ocean is perpetually covered by ice (dark blue colors), except near the equator where winds and ocean currents push sea ice eastward onto the dayside where it breaks up and melts (pale blue to light yellow colors). Credit: NASA Nexus for Exoplanet System Science (NExSS) / NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS).

Three-dimensional planetary general circulation models have been used to project climate change into future decades, but have matured to the point that they can probe habitability questions such as how a planet can become habitable under variations in stellar radiation and atmospheric chemistry. The NASA Nexus for Exoplanet System Science (NExSS) effort works on these matters in a cross-disciplinary effort to parse habitability in terms of the factors that make it happen, from host stars to protoplanetary disks and rocky planet atmospheres.

ROCKE-3D stands for Resolving Orbital and Climate Keys of Earth and Extraterrestrial Environments with Dynamics, now developing as a collaborative investigation within NExSS. At NASA GSFC, the Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS) developed ROCKE-3D to run global circulation model simulations deploying and manipulating past climates of Earth and other planets by way of analyzing climates and ocean habitats. The idea is to produce model spectra and phase curves for future observations. Let me quote from the GISS website:

Our project uses solar radiation patterns and planetary rotation rates from simulations of spin-orbit dynamical evolution of planets over Solar System history provided by our colleagues at the Columbia Astrobiology Center and at other institutions that are part of our NExSS team. In turn, the synthetic disk-integrated spectra we produce from the GCM will be used as input to a whole planetary system spectral model that emulates observations that candidate future direct imaging exoplanet missions might obtain…

Here you can see the direction of this work. What these teams are trying to do is model what future observatories may see when we become capable of directly imaging rocky exoplanets. We need to learn what kind of signals may be detectable as we allocate precious observing time to those targets most likely to repay the effort. Here theory about the kind of spectral details that life may produce is the foundation for later direct observational data.

Olson’s Oceans

Back to Olson, who wants to fold ocean dynamics into this effort and consider how they may be manifested on habitable exoplanets. Can features of ocean circulation that we cannot observe be inferred from atmospheric properties we can see? Olson’s work is an attempt to link ocean circulation with key planetary parameters, invoking the biological constraints differing ocean habitats may place on worlds around a variety of stars.

We can’t say how this work will develop, but there is the real prospect for the telescope design of future missions — think LUVOIR (Large UV/Optical/IR Surveyor) or HabEx (Habitable Exoplanet Observatory) — to be affected as we learn more about what we need to look for. Adds Olson:

“Our work has been aimed at identifying the exoplanet oceans which have the greatest capacity to host globally abundant and active life. Life in Earth’s oceans depends on upwelling (upward flow) which returns nutrients from the dark depths of the ocean to the sunlit portions of the ocean where photosynthetic life lives. More upwelling means more nutrient resupply, which means more biological activity. These are the conditions we need to look for on exoplanets.”

Immense effort is going into modeling planetary climate and evolution to guide our investigation of habitability. It will be fascinating to watch the trajectory of these studies as we begin to deploy advanced space-based resources to probe for biosignatures. My guess is that we will see early detections of potential biosignatures — these will receive huge press coverage — but we will not find anything that is unambiguous.

That may seem like a letdown when it happens, but ruling out abiotic mechanisms for possible biosignatures is equally a part of global circulation modeling, and this work will take time.

August 26, 2019

JUICE: Targeting Three Icy Moons

Because Europa Clipper has been on my mind, what with the confirmation of its next mission phase (see Europa Clipper Moves to Next Stage), we need to continue to keep the mission in context. What is playing out is a deepening of our initial reconnaissance of the Jovian system, and the JUICE mission (Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer) is a significant part of that overall effort. The European Space Agency has the spacecraft under development, with Airbus Defence and Space as the primary contractor.

We saw last week that while Europa Clipper will use flybys of Ganymede and Callisto for gravity maneuvers intended to refine its orbit, the latter two moons are not science priorities. JUICE, on the other hand, focuses on all three, each thought to house liquid water beneath the surface. JUICE is slated for a June, 2022 launch, reaching Jupiter in 2029 with the help of five gravity assists along the way, so its operations will overlap with Europa Clipper, the NASA craft launching in 2023. The coming decade will be busy indeed as we journey to and explore these compelling icy targets.

The orbital maneuvers chosen for JUICE are intriguing, for after its first flyby of Europa in 2030, the spacecraft is to enter a high-inclination orbit to study Jupiter’s polar regions and magnetosphere. Repeated flybys of Europa, Ganymede and Callisto are planned, and following a Callisto flyby in 2031, the spacecraft will actually enter orbit around Ganymede, making it the first spacecraft to orbit a moon other than our own. I’m simplifying these complicated orbital maneuvers for the sake of brevity, but the point is that JUICE will greatly expand our datasets on all three moons.

In June of 2019, engineers at Airbus Defence and Space’s site in Toulouse tested the navigation camera that will be essential for radio tracking and position and velocity information of the spacecraft relative to the moon it is currently studying. Given the powerful radiation found near Jupiter, the spacecraft will, like Europa Clipper, be radiation-hardened, allowing it to operate between 200 and 400 kilometers from its targets at closest points of rendezvous. The pointing accuracy demanded of NavCam during fast and close approaches like these is critical to the mission’s success.

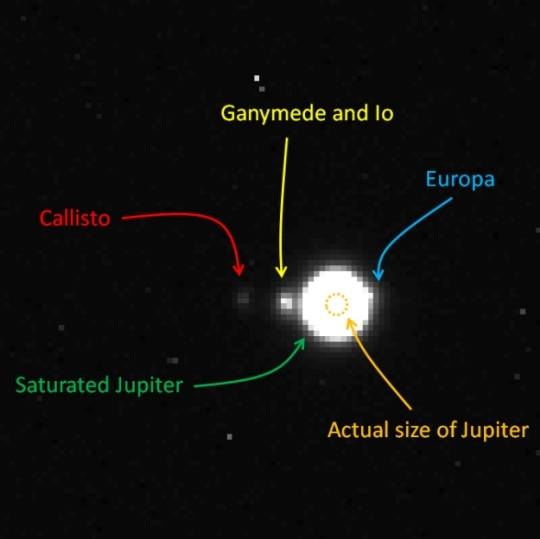

The June tests looked at the NavCam engineering model in real sky conditions, the point being to stress the hardware and software interfaces to validate their design, as well as to prepare the image processing and onboard navigation software that JUICE will use to acquire its images. The engineers observed Earth’s own moon and a variety of sky objects included Jupiter itself as part of these tests, running NavCam in ‘imaging mode’ and ‘sky centroiding mode’ as part of fine tuning attitude control software.

Image: The Navigation Camera (NavCam) of the Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE) has been given its first glimpse of the mission’s destination while still on Earth. The camera was mounted to an equatorial mount and pointed towards different targets, including bright stars, Jupiter and its moons in order to exercise its ‘Imaging Mode’ and ‘Stars Centroiding Mode’. The integration time was optimized for capturing the stars and moons acquisition, so Jupiter appears saturated. In this annotated image the size of Jupiter is indicated. Credit & Copyright: Airbus Defence and Space.

“Unsurprisingly, some 640 million kilometres away, the moons of Jupiter are seen only as a mere pixel or two, and Jupiter itself appears saturated in the long exposure images needed to capture both the moons and background stars, but these images are useful to fine-tune our image processing software that will run autonomously onboard the spacecraft,” says Gregory Jonniaux, Vision-Based Navigation expert at Airbus Defence and Space. “It felt particularly meaningful to conduct our tests already on our destination!”

Image: Impressions of how the Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer will see moons Europa (left), Ganymede (middle) and Callisto (right) with its Navigation Camera (NavCam). To generate these images, the NavCam was fed simulated views – based on existing images of the moons – to process realistic views of what can be expected once in the Jupiter system. Credit & copyright: Airbus Defence and Space.

The actual flybys will provide close inspection of surface features on Europa, Ganymede and Callisto. In the suite of tests, NavCam also received simulated views of the three moons in order to process the kind of imagery it will acquire in Jupiter space. NavCam will capture imagery that will be greatly augmented by the high-resolution camera suite that will give us our best views of the icy surfaces below.

By the end of 2019, the test NavCam will be augmented with a full flight representative performance optics assembly that will support onboard tests of the complete spacecraft. Meanwhile, a test version of the spacecraft’s 10.5-m long magnetometer boom developed by SENER in Spain has undergone testing at ESA’s Test Centre in the Netherlands, as part of what ESA is describing as “… the most powerful remote sensing, geophysical, and in situ payload complement ever flown to the outer Solar System.”

Image: Magnetometer boom built for ESA’s mission to Jupiter by European Space Agency. Credit: ESA–G. Porter, CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO.

August 23, 2019

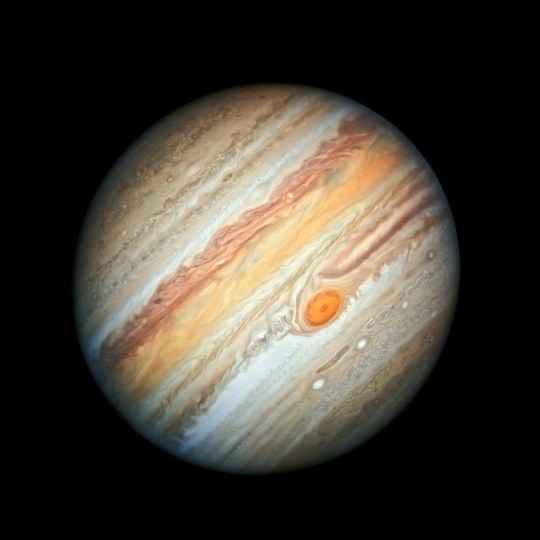

Going Deep into Jupiter’s Storms

Having just looked at events that may have shaped Jupiter’s core, it seems a good time to note the new Hubble image of the planet, taken on June 27, 2019. A couple of things to focus on in the image below: The vast anticyclonic storm we call the Great Red Spot, about the diameter of the Earth, is evident as it rolls counterclockwise between bands of clouds moving in opposite directions toward it.

We still don’t know why, but the storm itself continues to shrink. Smaller storms show up vividly as white or brown ovals, some of which dissipate within hours, while others may be as long lasting as the Great Red Spot, which has dominated Jupiter’s face for at least 150 years. Note the cyclone showing up south of the Spot, visible as a worm-shaped feature. You can also see other anticyclones, appearing as white ovals.

Image: The NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope reveals the intricate, detailed beauty of Jupiter’s clouds in this new image taken on 27 June 2019. It features the planet’s trademark Great Red Spot and a more intense colour palette in the clouds swirling in the planet’s turbulent atmosphere than seen in previous years. This image was captured by Hubble’s Wide Field Camera 3, when the planet was 644 million kilometres from Earth. Credit: NASA, ESA, A. Simon (Goddard Space Flight Center), and M.H. Wong (University of California, Berkeley).

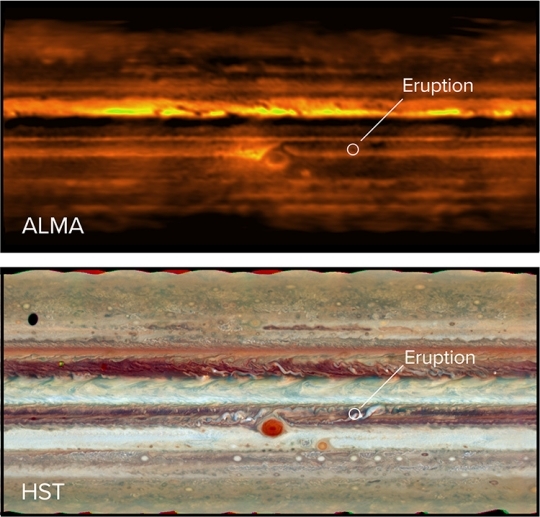

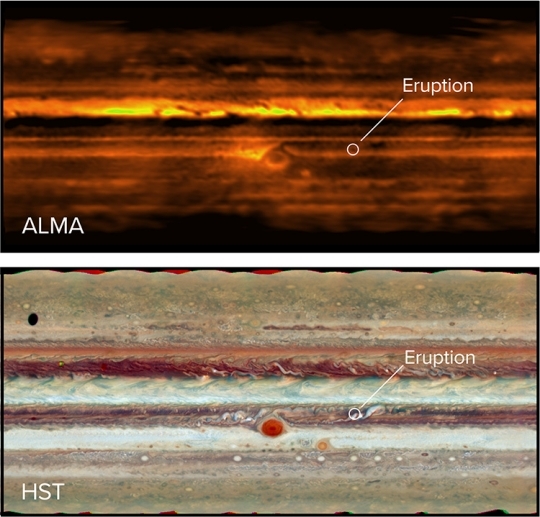

But let’s move beyond Hubble. New work on the storm clouds of Jupiter swirling through the planet’s atmospheric belts has just appeared, drawing not only on space-based resources but also a mix of optical and radio telescopes that have gone into recent tracking of their activity. In January of 2017, Australian amateur astronomer Phil Miles observed the bright plume of a storm that was subsequently picked up by observations with the Atacama Large Millimeter/Submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile. The latter work was led by UC-Berkeley astronomer Imke de Pater, producing a paper that has been accepted at the Astronomical Journal (citation below).

Things happen quickly enough on Jupiter that we can track them by daily observation, and Hubble images taken a week after the ALMA work showed that what had been a single plume had spawned a second plume and left visible downstream changes in Jupiter’s south equatorial belt. Moreover, four bright spots seen three months earlier in the north equatorial belt had disappeared, while the belt itself had widened as well as changed colors, from a striking white to orange-brown. This may be the result of gas from plumes now depleted of ammonia falling back into the lower atmosphere.

“If these plumes are vigorous and continue to have convective events, they may disturb one of these entire bands over time, though it may take a few months,” says de Pater. “With these observations, we see one plume in progress and the aftereffects of the others.”

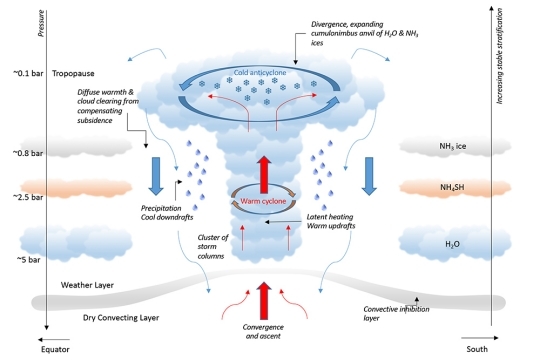

The paper posits that plumes like these emerge about 80 kilometers below the cloud tops, in a region where clouds of liquid water droplets are common. Jupiter’s atmosphere is primarily hydrogen and helium, with trace amounts of methane, ammonia, hydrogen sulfide and water. What we’re seeing at the top-most cloud layer, with its brown belts and white zones, is largely made up of ammonia ice. A layer of solid ammonium hydrosulfide particles is found below this in the upper cloud deck.

Image: ALMA’s view of Jupiter at radio wavelengths (top) and the Hubble Space Telescope’s view in visible light (bottom). The eruption in the South Equatorial Belt is visible in both images: a dark spot in radio, a bright spot in visible. Credit: ALMA image by Imke de Pater and S. Dagnello; Hubble image courtesy of NASA.

The radio telescopes of ALMA are able to see beneath the upper ammonia clouds that are opaque in visible frequencies, but de Pater’s team also brought data from Hubble, the Very Large Array, the Gemini, Keck and Subaru observatories in Hawaii and the Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Chile into the mix, homing in on the storm seen above as it emerged from the lower cloud levels into the upper ammonia ice clouds.

Image: A closeup of the two bright white plumes (center) in the South Equatorial Belt of Jupiter and a large downstream disturbance to their right. Credit: Imke de Pater, UC Berkeley; Robert Sault, University of Melbourne; Chris Moeckel, UC Berkeley; Michael Wong, UC Berkeley; Leigh Fletcher, University of Leicester.

The storm clouds, reaching Jupiter’s tropopause, where the atmosphere is at its coldest, spread out in much the same way as the anvil-shaped formations of thunderstorms we see in Earth’s atmosphere. The ALMA data were sufficient to show that high concentrations of ammonia gas are forced upward during an eruption like this. Convection, the scientists believe, brings both ammonia and water vapor high enough for the water to condense into liquid droplets, releasing heat along the way.

Now we have a plume with enough momentum that, as heat is released from condensing water, can break out above the clouds of the upper deck, where the ammonia will freeze to create the white plume of these images.

“We were really lucky with these data, because they were taken just a few days after amateur astronomers found a bright plume in the South Equatorial Belt,” adds de Pater. “With ALMA, we observed the whole planet and saw that plume, and since ALMA probes below the cloud layers, we could actually see what was going on below the ammonia clouds.”

Image (click to enlarge): An illustration of “moist convection” in Jupiter’s atmosphere shows a rising plume originating about 80 kilometers below the cloud tops, where the pressure is five times that on Earth (5 bar), and rising through regions where water condenses, ammonium hydrosulfide forms and ammonia freezes out as ice, just below the coldest spot in the atmosphere, the tropopause. Credit: Adapted from illustration by Leigh Fletcher, University of Leicester.

This useful analysis was made possible because of simultaneous observations at different wavelengths, in this case homing in on transient events and showing us how the atmosphere at different levels, from cloud tops to deep below, responds to them. This is new ground in the study of Jupiter’s weather, as the paper notes:

These data are the first to characterize the atmosphere below the cloud layers during/following such outbreaks. Aided also by observations ranging from uv to mid-infrared wavelengths, we have shown that the eruptions are consistent with models where energetic plumes are triggered via moist convection at the base of the water cloud. The plumes bring up ammonia gas from the deep atmosphere to high altitudes, where NH3 gas is condensing out and the subsequent dry air is descending in neighboring regions. The cloud tops are cold, as shown by mid-infrared data, indicative of an anticyclonic motion, which causes the storm to break up, as expected from similarities to mesoscale convective storms on Earth. The plume particles reach altitudes as high as the tropopause.

The paper is de Pater et al., “First ALMA Millimeter Wavelength Maps of Jupiter, with a Multi-Wavelength Study of Convection” (preprint).

Paul Gilster's Blog

- Paul Gilster's profile

- 7 followers