Paul Gilster's Blog, page 176

June 10, 2015

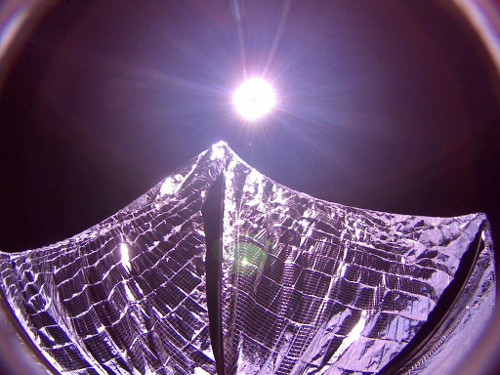

Sail in View

The main post for today will be online around 1230 EDT (1630 UTC), but first I have to publish this image from LightSail, along with Jason Davis’ description. Nice work!

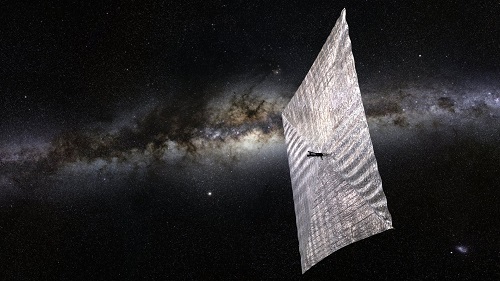

“The Planetary Society’s LightSail test mission successfully completed its primary objective of deploying a solar sail in low-Earth orbit, mission managers said today [June 9]. During a ground station pass over Cal Poly San Luis Obispo that began at 1:26 p.m. EDT (17:26 UTC), the final pieces of an image showcasing LightSail’s deployed solar sails were received on Earth. The image confirms the sails have unfurled, which was the final milestone of a shakedown mission designed to pave the way for a full-fledged solar sail flight in 2016.”

A second image may include a view of the Earth, according to Davis. What may happen next is a further tensioning, or ‘walking out,’ of the sail booms, which should further flatten the sail. Davis notes, too, that the ‘fish-eye’ lens of the camera produces a bit of distortion in the image.

Addendum: Bill Nye’s statement on LightSail’s success.

“I’m very proud to say that our LightSail test mission was a success. We saw again that space is hard. It’s a test flight, and sure enough our little spacecraft tested us. I’ve got to congratulate our remarkable team. They solved some unexpected big problems up there with nothing but short radio signals sent from down here. This LightSail test taught us a lot, just as we hoped it would, and so we’re ready to do some real solar sailing with LightSail’s 2016 mission. Let me finish by reminding everyone that this mission and next year’s flight are funded entirely by our supporters and especially our members— people of Earth, who want to participate in space exploration. We’re changing the way humankind explores space. Today is a big day for The Society and for space explorers everywhere.”

June 9, 2015

Mission Updates Far and Near

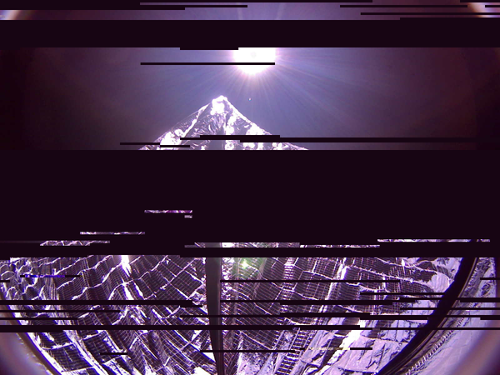

The Planetary Society’s Emily Lakdawalla tells us (via Twitter) that she has a history with jigsaw puzzles, one that finally paid off in the image below. You’re looking at her work on a partially de-scrambled image from LightSail, fragmentary because the entire image was not downloaded during a Cal Poly (San Luis Obispo) overflight on the afternoon of the 8th. The complete image should be downloaded later today, and perhaps shown at an upcoming press conference with LightSail engineering team leaders scheduled for Wednesday June 10 at 1730 UTC (1330 EDT).

At any rate, LightSail’s deployed sails are in view. Bill Nye, CEO of The Planetary Society, was on National Public Radio yesterday (audio here) in a brief spot in which he described the unfurling of the solar sail as a ‘sail Mary pass,’ a longshot required by circumstance as the spacecraft continued to tumble. If the phrase ‘sail Mary pass’ is inscrutable to you, you may not be familiar with American football, where ‘hail Mary pass’ has become a routine way of describing desperate plays made under pressure (this exhausts my knowledge of football — I know only baseball — and I will send you to the Wikipedia for details). At any rate, sail deployment was the purpose of this first LightSail mission, and sail deployment we had.

Ceres in Motion

Meanwhile, spectacular views from ongoing space missions continue to flow in. The next few weeks in particular are going to be rich in imagery as New Horizons closes on Pluto/Charon and Dawn continues its work at Ceres. The latest video animation from Ceres is something to enjoy more than once with a cup of coffee. If this doesn’t start your day right, what will?

Eighty images were combined to create the video, with the vertical dimension exaggerated by a factor of two. The views are from Dawn’s first mapping orbit at 13,600 kilometers and include later navigation images from 5100 kilometers, providing a detailed view of the terrain. I’m using the copy of the JPL video that io9 kindly posted to YouTube.

Dawn’s second mapping orbit began on June 3, with the rest of the month slated for observations about 4400 kilometers above the surface. Of the video, Dawn team member Ralf Jaumann (DLR, Berlin) says: “We used a three-dimensional terrain model that we had produced based on the images acquired so far. They will become increasingly detailed as the mission progresses — with each additional orbit bringing us closer to the surface.”

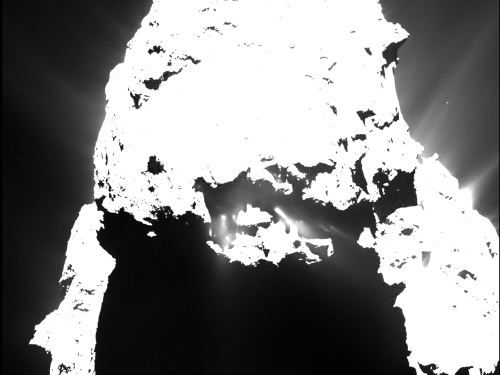

A Restive Comet

The Ma’at region at comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko’s ‘head’ clearly stays active even after it falls into shadow, as we can see from the latest imagery from the Rosetta spacecraft. Here we’re looking at jets of dust escaping into space, the result, researchers believe, of the increased heating of the comet as it moves closer to the Sun. Perihelion is coming up in mid-August, and this image was taken with a scant 270 million kilometers separating Sun and comet. “Only recently have we begun to observe dust jets persisting even after sunset”, says OSIRIS principal investigator Holger Sierks (Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research).

Image: This image of Rosetta’s comet taken on 25 April, 2015 from a distance of approximately 93 kilometers shows clearly distinguishable jets of dust after nightfall. Credit: ESA/Rosetta/MPS for OSIRIS Team MPS/UPD/LAM/IAA/SSO/INTA/UPM/DASP/IDA.

OSIRIS scientist Xian Shi (MPS) adds that although the dusty cometary surface cools rapidly after sunset, deeper layers of the comet — evidently containing frozen gases — retain their heat, a phenomenon that has also been observed on comet 81P/Wild 2 and Deep Impact comet 9P/Tempel 1. We’ll learn a good deal more about how comets awaken as Rosetta follows 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko into the summer in the long fall toward perihelion.

June 8, 2015

LightSail Deployment Apparently Successful

After a nerve-wracking week in which contact was repeatedly lost and then regained, The Planetary Society’s LightSail has successfully charged its batteries and deployed its solar sail. Deployment began at 1947 UTC (1547 EDT) June 7, just off the coast of Baja California, with telemetry showing climbing motor counts and power levels consistent with ground testing. In a late afternoon update, Jason Davis also noted that the spacecraft’s cameras were on (see Deployment! LightSail Boom Motor Whirrs to Life).

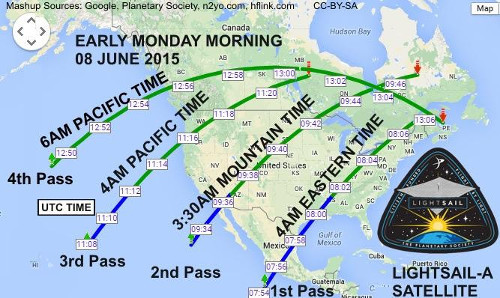

If you’re following this mission closely, you’ll want to know about Ted Molczan’s page LightSail-A: Estimated Post-Sail Deployment Orbital Elements, with early predictions on

orbital decay with the sails extended. Bonnie Link (hflink.com) produced a map showing Monday’s LightSail passes over North America that you can see below. Here the white boxes are UTC times. The green arcs are sunlit, the blue in shadow and thus not visible.

Further confirmation of sail deployment came in a tweet from Davis noting that early post-deployment telemetry showed the spacecraft’s tumble rate had slowed dramatically. So a tiny spacecraft the size of a shoebox paid for by private donors has apparently managed to achieve its primary goal despite early questions about the effectiveness of its solar arrays and battery and a series of communications breakdowns caused by software issues. We’ll learn more later today, with the first team teleconference scheduled for 1330 UTC.

Images of full sail deployment should become available at some point today and I’ll update this post then. LightSail is likely to remain in space no more than about three days, given the drag it’s already experiencing. Remember that this was expected, as the first LightSail mission wasn’t designed as a test of true solar sailing, but rather a way to shake out deployment issues (and plenty of them, obviously, turned up, especially with regard to attitude control).

Cees Bassa reported the first visual observations from Dwingeloo (Australia) post-deployment, noting the increase in the rate of orbital decay:

LightSail [40661/15025L] was with the video camera! At about 15 deg elevation it first was invisible, but then gave a long flare up to about 4th or 5th magnitude. It was running about 10s early on the last JSpOC elset, suggesting the sail has deployed, increasing the drag significantly. Congratulations to the Planetary Society!

A subsequent observation (via Ron Dantowitz, Clay Center Observatory) was of about 4th magnitude and stable in brightness. As Ted Molczan points out, you can go to the Heavens Above page, enter your location, and view a chart of visible passes of LightSail. Or check the LightSail viewing tips Jason Davis gives in the article referenced above. Flyovers around dawn and dusk are the best time to see a spacecraft still illuminated by sunlight.

June 5, 2015

The View from Outside the Galaxy

The Russian Federal Space Agency (Roscosmos) has recently released a video (viewable here on YouTube) showing how a number of celestial objects might look if they were substantially closer to Earth than they are. The image of the Andromeda galaxy and its trillion stars projected against an apparent Earthscape is below. Unfortunately, this seems to be an astronomical image inserted into a view that purports to show what we would see in visible light. What we would actually see if we were standing in such a location is much different. After all, astronomical images are teased out of lengthy exposures in carefully chosen wavelengths.

In reality the Andromeda galaxy is gigantic even when viewed from 2.5 million light years, but I doubt the average person has any idea where it is in the sky. Although considerably wider than the Moon as seen from Earth, M31 is visually faint, a fact that reminds us of the importance of photographs and charged coupled devices (CCDs) in light gathering as we probe the universe. The human eye is a very limited instrument. As it happens, I’m currently reading Alan Hirshfeld’s Starlight Detectives: How Astronomers, Inventors, and Eccentrics Discovered the Modern Universe (2014), which examines the transition between sketches of visual observations and the steady advances in photography in the 19th Century that brought so much more of the galaxy into view.

About a year ago I looked at Poul Anderson’s novel World Without Stars, which tells of a starship crew dispatched to a planet far outside the Milky Way, a place where from 200,000 light years, galaxy-rise is a rather muted event (see The Milky Way from a Distance). Anderson depicts a galaxy filling 22 degrees along its major axis, but one that appears ‘ghostly pale across seventy thousand parsecs.’ In the same issue of Analog (June, 1966) in which the novel was originally serialized, John Campbell published Anderson’s letter describing the calculations that went into that description, and explaining why the galaxy from outside would be so dim.

One point came up which may interest you. Though the galaxy would be a huge object in the sky, covering some 20⁰ of arc, it would not be bright. In fact, I make its luminosity, as far as this planet is concerned, somewhere between 1% and 0.1% of the total sky-glow (stars, zodiacal light, and permanent aurora) on a clear moonless Earth night. Sure, there are a lot of stars there — but they’re an awfully long ways off!

But it’s not just the distance. Galaxies, as UC-Santa Cruz astrophysicist Greg Laughlin has explained on his systemic site, are mostly empty space, or as he puts it, “To zeroth, to first, to second approximation, a galaxy is nothing at all.”

Building the Galactic Map

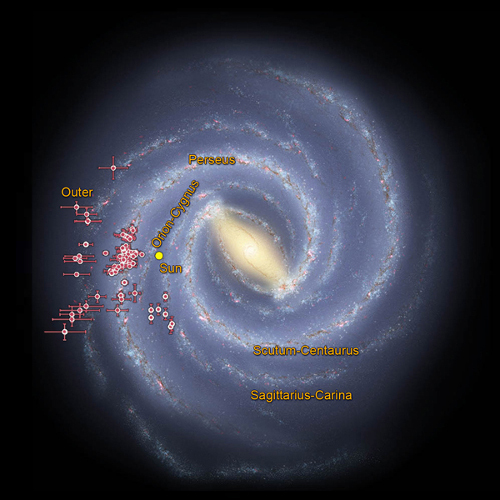

Interesting, then, to think about recent work on mapping the galaxy. The WISE mission (Wide-Field Infrared Survey Explorer) produced the data used in this effort to improve our understanding of the Milky Way’s spiral arm structure. Precisely because we don’t have the kind of overview of the galactic disk referred to above, we’re trying to sense the shape of our galaxy from within a disk obscured by dust and seen from our vantage two-thirds of the way out from the galaxy’s center. The new work supports a four-arm model for the Milky Way.

To derive this result, Denilso Camargo (Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil) and team worked with WISE data revealing over 400 embedded star clusters, stellar nurseries of the kind that form in the dust- and gas-packed spiral arms, where most stars originate. Usefully for the purposes of the study, young clusters like these have not had the chance to drift out of the arms, thus providing a powerful tool for visualizing spiral arm structure.

In the paper, Camargo and team investigated 18 embedded clusters, seven of which are newly discovered in the WISE images — this complements a list of 437 new clusters Camargo recently published. The work supports the hypothesis that embedded clusters are predominantly found in the galactic thin disk and along its spiral arms. The Perseus and Scutum-Centaurus arms are the most prominent, while the Sagittarius and Outer arms show fewer stars but appear to have the same amount of gas as the other two arms.

Image: This illustration shows where WISE data revealed clusters of young stars shrouded in dust, called embedded clusters, which are known to reside in spiral arms. The bars represent uncertainties in the data. The nearly 100 clusters shown here were found in the arms called Perseus, Sagittarius-Carina, and Outer — three of the galaxy’s four proposed primary arms. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul.

Our Sun is in a minor arm called Orion Cygnus, marked on the image. You can see what a mapping challenge it is to work out, from within the disk itself, what kind of spiral arm structure exists. What we wouldn’t give for a perspective like the one above…

Supernovae in the Deep

Backing out to see the galaxy whole would take us far into intergalactic space, where we’re also learning about three supernovae found between galaxies in large galactic clusters. Melissa Graham, a UC-Berkeley postdoc, is the leader of a study of these objects. She also turns out to be a science fiction fan, one whose reference to the intergalactic deep isn’t the Anderson story I cited above, but Iain Banks’ novel Against a Dark Background (Orbit, 2009). There, the planet Golter lies a million light years from the nearest star.

We can imagine Anderson’s pale galaxy in an otherwise starless night sky, and Banks’ as well. Planets around the three supernovae in Graham’s study would have been destroyed in the event, but if there were any before, their night skies would likewise have been depleted of stars. “It would have been a fairly dark background indeed,” Golter adds, “populated only by the occasional faint and fuzzy blobs of the nearest and brightest cluster galaxies.”

Graham’s work using Hubble Space Telescope imaging confirms the earlier discovery (at the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope on Mauna Kea) of the three supernovae and shows that they reside in a population of solitary stars in regions where the density of stars is about a million times less than we see from Earth. Gravitational interactions in massive galactic clusters can sometimes fling as many as 15 percent of a single galaxy’s stars out of the main disk, though the stars remain gravitationally bound within the cluster itself. Stars like these are going to be all but invisible unless they explode as Type Ia supernovae. Their explosions thus prove useful as a way to study the broader population of intracluster stars.

And this is intriguing: A fourth exploding star was found by the same observatory, one that may well be inside a globular cluster. If this is the case, we have an unusual event, the first time that a supernova has been found inside a globular cluster (GC). From the paper:

We have shown that the SN Ia in Abell 399 was very likely hosted by a faint red point-like source that has a magnitude and color consistent with both dwarf red sequence galaxies and red GCs. Our statistical analysis of the expected surface densities has shown that a dwarf galaxy is less likely at that location than a GC, due to the presence of a nearby elliptical galaxy. We have demonstrated that the rate enhancements in dwarfs or GCs implied by this new faint host are plausible under current observational constraints, and we do not reject either hypothesis.

Image: One of the four supernovae (top, 2009) may be part of a dwarf galaxy or globular cluster visible on the 2013 HST image (bottom). Credit: Melissa Graham, CFHT and HST.

The supernovae paper is Graham et al., “Confirmation of Hostless Type Ia Supernovae Using Hubble Space Telescope Imaging,” accepted at The Astrophysical Journal (preprint). The paper on galactic mapping is Camargo et al., “Tracing the Galactic spiral structure with embedded clusters,” Monthly Notices of the Royal Society Vol. 450, Issue 4 (20 May, 2015), pp. 4150-4160 (full text).

June 4, 2015

Science Fiction: An Updated Solar System

Having written yesterday about the constellation of missions now returning data from deep space, I found Geoffrey Landis’ essay “Spaceflight and Science Fiction” timely. The essay is freely available in the inaugural issue of The Journal of Astrosociology, the publication of the Astrosociology Research Institute (downloadable here). And while it covers some familiar ground — Jules Verne’s moon cannon, Frau im Monde, etc. — it also highlights Landis’ insights into the relationship between the space program and the genre that helped inspire it.

My friend Al Jackson has written in various comments here (and in a number of back-channel emails) about Wernher von Braun’s ideas and their relation to science fiction. As Landis notes, von Braun was himself a science fiction reader who credited an 1897 novel called Auf Zwei Planeten (Two Planets) by Kurd Lasswitz with inspiring his interest in rocketry. So, by the way, did Walter Hohmann, the German engineer who helped develop the area of orbital dynamics and demonstrated fuel-efficient ways to move between two orbits.

Although there have been numerous editions of the Lasswitz book since its original publication, it would not be until 1971 that an English translation (badly abridged) was published. The story depicts the discovery of a Martian base at the Earth’s north pole, with humans being taken back to Mars for a look at its canals. Lasswitz followed Schiaparelli and Percival Lowell in his fascination with a thriving, fertile Mars and the ancient race that lived there. The science fiction historian Everett F. Bleiler believes Lasswitz was a major influence on Hugo Gernsback and hence on the shape of science fiction in the 1920s and ‘30s.

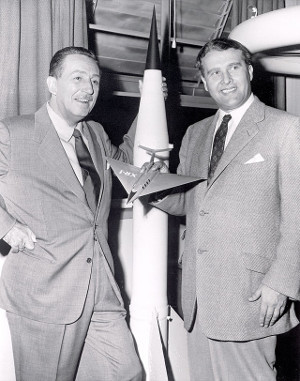

Image: Wernher von Braun with Walt Disney, with whom he collaborated on a series of three films. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

But back to von Braun, who lived in a Germany in which Fritz Lang made the 1929 film Frau im Mond (‘Woman in the Moon’) with the help of rocket scientists Hermann Oberth and Willy Ley, who were hired to build a real rocket to launch in synch with the film’s opening. That stunt didn’t happen, but Oberth, Ley and von Braun would have worked together in the early 1930s as part of the Verein für Raumschiffahrt, a rocket club created by amateurs that would go on to influence the development of the deadly V-2.

In his early years in the United States, von Braun wrote a short science fiction novel in German about a trip to Mars, one that describes intelligent Martians in the context of a carefully designed mission. This is where things get tricky for the bibliographer. The technical appendix for this novel was published as Das Marsproject in 1952, appearing as The Mars Project the following year. The novel that had included it was not published until a 2006 edition from a Canadian publisher, who offered it as something of a historical curiosity (available as Project Mars: A Technical Tale, from Collector’s Guide Publishing).

Science fiction, meanwhile, had entered a robust post-war era in which spaceflight seized the public imagination. Landis comments:

The V-2 brought the reality of rockets public in a highly visible way; rockets were no longer comic-strip stuff, but real and highly-visible tools of warfare and, presumably, spaceflight. Following the end of the war, the rockets on science fiction magazine and covers now all looked remarkably like the V-2, and science fiction entered a golden age, with spaceflight stories written by a number of classic writers such as Robert Heinlein, Arthur C. Clarke (who was also noted for inventing the concept of a geosynchronous communications satellite), Isaac Asimov, and Andre Norton reaching new audiences.

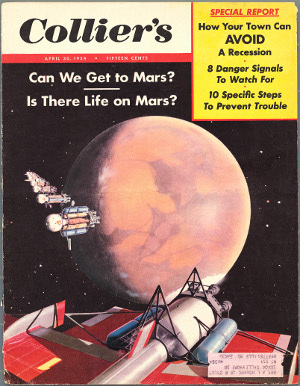

It was in this same era that Collier’s ran its highly popular series of articles on von Braun’s ideas, with eight issues illustrated by Chesley Bonestell and other artists between 1952 and 1954. Soon von Braun was a household name thanks not only to Collier’s but also Walt Disney’s TV programs, on which he appeared three times. By 1956, von Braun had scaled down his Mars mission and published his later thinking in The Exploration of Mars, written with co-author Willy Ley.

What effect did the space program von Braun did so much to launch have on the science fiction of its day? It’s an interesting question, and one that Landis is ambivalent about, for as we began to probe the planets, we learned that they differed sharply from what writers had imagined:

In some respects the space program was a disappointment to science fiction. Spaceflight has not become as simple and ubiquitous (nor as cheap) as science fiction predicted. The cratered Mars revealed by the Mariner and Viking missions was not nearly as colorful a setting for science fiction as the Mars of Percival Lowell, with its canals and ancient, dying civilization; the furnace of the Venus surface revealed by Russian and American probes was not nearly as picturesque a setting for science fiction as the earlier swampy or even ocean-covered Venus hypothesized by astronomers when all that could be seen were clouds. Even the moon, dry and grey and mostly lacking in resources, was a disappointment.

Image: The April 30, 1954 issue of Collier’s, part of a series that explored von Braun’s ideas.

What grows out of this is a turn in the field’s direction. If the Solar System was the great venue of exploration for the science fiction of the Gernsback and later Campbell eras, by the mid-1960s many of its destinations had been revealed as barren places (think Mariner 4 and its images of a cratered, evidently lifeless Mars). Interstellar destinations, Landis notes, became the new terra incognita, but so did an entirely different kind of exploration into social and psychological realms (Bradbury becomes an interesting bridge between these two worlds). Landis doesn’t say it but I assume he’s thinking that trends like science fiction’s ‘New Wave’ grew directly out of this impulse.

Think back, then, to some of science fiction’s precursors. Johannes Kepler could write in his Somnium (1609) about space travel by non-technological means in a book that used the Moon as a place where basic ideas of astronomy could be discussed. Edgar Allen Poe would develop his 1835 story “The Unparalleled Adventure of One Hans Pfaall” with a lunar trip using actual technology, in his case a balloon, finding ways to make Earth’s atmosphere extend high enough for a balloon filled with a new kind of gas to get there.

From Voltaire (Micromegas, 1752) to Verne, science fiction shaped spaceflight around technologies available at the time, like Verne’s 274-meter cannon driven by 200 tons of gun cotton. What could be envisioned drove the narrative, but so did the desire for an exotic destination on which humans could walk. It’s interesting that we’re again seeing Solar System destinations as revealed by the space program as settings for modern SF — I think of tales like Gerald Nordley’s “Into the Miranda Rift” as a classic in this vein — but the interstellar impulse has never been stronger as SF continues its quest for alien, habitable worlds.

June 3, 2015

Mission Data: An Early Summer Harvest

What a time for space missions, with data returning from far places and a nail-biter close at hand. On the latter, be advised that the LightSail mission team has decided to divide sail deployment into two operations, one of them starting today as the CubeSat’s solar panels are released and an imaging session verifies the craft is ready for sail deployment. The actual deployment will then follow on Friday, and is currently scheduled for 1647 UTC (1247 EDT).

From Jason Davis:

The first indication the sail sequence has started should come from the spacecraft’s automated telemetry signals, which include a motor revolution count for the boom system. The next few orbits will be used to check LightSail’s health and status, transfer imagery from the cameras to flight computer, and begin sending home to Earth.The last contact of the day comes during a Cal Poly ground pass at 4:16 p.m. EDT (20:16 UTC). By then, the team hopes to at least part of a sail image on the ground. If not, the next series of ground pass orbits begin at 2:45 a.m. EDT Saturday.

On to Pluto

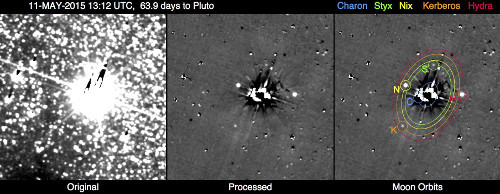

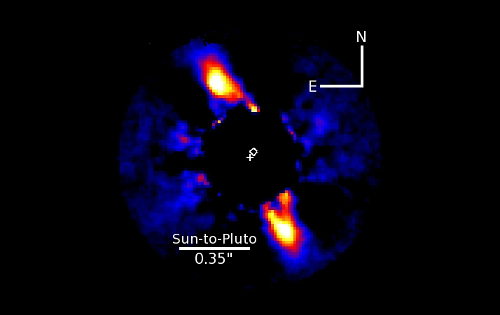

At the outer edge of the system (or, if you prefer, the inner edge of the Kuiper Belt), New Horizons pushes on toward Pluto/Charon. As we wait with great anticipation for the views that lie ahead, a new study published in Nature looks at what we have learned about Pluto’s moons, with interesting findings regarding Nix and Hydra. Evidently the gravitational interactions in this system are complex, with the smaller moons tumbling unpredictably. But if the rotational motions are odd, the Plutonian moons’ orbits are governed by resonance.

“The resonant relationship between Nix, Styx and Hydra makes their orbits more regular and predictable, which prevents them from crashing into one another,” says Douglas Hamilton (University of Maryland). “This is one reason why tiny Pluto is able to have so many moons.”

We also learn that tiny Kerberos, discovered in 2011, is distinctively dark compared with the other moons. We can hope that New Horizons helps to solve the riddle of this variation. The study in Nature is based on a new analysis of Hubble Space Telescope data on the four smaller Plutonian moons. Hamilton notes that because Pluto and Charon comprise a binary system, what we learn about the orbits of moons here may help us understand how planets could behave orbiting a binary star, useful information for the exoplanet hunt.

Meanwhile, the New Horizons team has reported that the first set of hazard-search images of Pluto/Charon show, at least so far, no signs of trouble for the approaching spacecraft.

Image: This image shows the results of the New Horizons team’s first search for potentially hazardous material around Pluto, conducted May 11-12, 2015, from a range of 76 million kilometers. The image combines 48 10-second exposures, taken with the spacecraft’s Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI), to offer the most sensitive view yet of the Pluto system. Credit: New Horizons / JHU/APL.

Off on a Comet

You would think New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern would have enough on his plate just now, but Stern is also principal investigator for the Alice instrument at the Southwest Research Institute in Colorado. Alice has just made the news again in relation to its findings aboard the European Space Agency’s Rosetta spacecraft, which show that electrons near the surface of comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko cause the swift breakup of water and carbon dioxide there rather than photons from the Sun, which had been the prior explanation.

“The discovery we’re reporting is quite unexpected,” said Stern. “It shows us the value of going to comets to observe them up close, since this discovery simply could not have been made from Earth or Earth orbit with any existing or planned observatory. And, it is fundamentally transforming our knowledge of comets.”

Rosetta has been orbiting within about 160 kilometers of the comet since last August. What the Alice spectrograph does is to study the far-ultraviolet wavelength band in order to reveal the chemistry of the gases in the cometary coma. Much of the water and carbon dioxide being found in the coma comes from eruptions on the surface. Analysis of the Alice data shows that it is seeing water and carbon dioxide being broken up about one kilometer from the cometary nucleus by electrons produced by solar radiation.

Image: This composite is a mosaic comprising four individual NAVCAM images taken 31 kilometers from the center of comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko on Nov. 20, 2014. The image resolution is 3 meters per pixel. Credit: ESA/Rosetta/NAVCAM.

And on to Ceres

The Dawn spacecraft sent the image below back to Earth on May 23, after which it moved toward its second mapping orbit, which it is scheduled to enter today. The spacecraft will spend the rest of June observing Ceres from roughly 2400 kilometers above the surface. What we see below is part of a sequence of images from 5100 kilometers, with resolution of about 480 meters per pixel. This image is part of OpNav9, the final set of Ceres imagery taken by Dawn for navigation purposes. Note the numerous secondary craters now visible, caused by the impact of debris from the larger impact sites.

Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/UCLA/MPS/DLR/IDA.

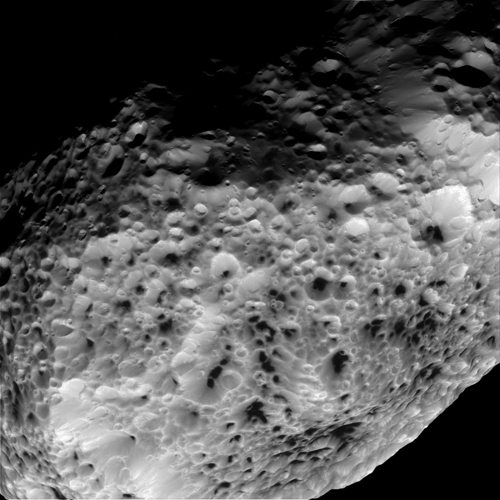

And Finally, Hyperion

Cassini has been doing yeoman work for years now, but the image below shows its final close approach to Saturn’s moon Hyperion. Given the wide range in moons we’ve found at both Jupiter and Saturn, the discovery of the odd surface of Pluto’s moon Kerberos swims into context. When has a new encounter in deep space failed to offer up a few surprises? In the face of this, Hyperion’s odd, sponge-like appearance fits right in, an indication that the moon has an unusually low density and is porous, so that impactors compress the surface.

Image: Cassini’s view of Hyperion was acquired at a distance of approximately 38,000 kilometers from Hyperion and at a Sun-Hyperion-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 46 degrees. Image scale is 230 meters per pixel.

Cassini does have several more close flybys of Saturnian moons scheduled for 2015, but after that follows a departure of the planet’s equatorial plane as controllers prepare the craft for its final events. The ‘Grand Finale’ plunge, closing to within 4000 kilometers of Titan’s cloud tops, is part of this, as are maneuvers close enough to the F ring to do radar backscatter measurements for the first time. Cassini will ultimately burn up in Saturn’s atmosphere, and this seems like a good time to quote The Planetary Society’s Emily Lakdawalla on the matter:

When Cassini finally flies low enough to fall into Saturn’s atmosphere on September 15, 2017, it will be a day not to mourn it, but rather to celebrate its achievements. The day for mourning will come a month or few later, when Juno’s mission likewise comes to an end. On that day, for the first time since the 1970s, Earth will have no active missions exploring any of the giant planets. There won’t even be a mission on the way. The Voyagers and New Horizons will (hopefully) still be active way beyond Neptune, but Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune will only be visible through telescopes on Earth.

All of which makes the constellation of space achievements we’re celebrating this summer both dazzling and a bit poignant. At the very least, an exploration hiatus approaches.

June 2, 2015

A Kuiper Belt in the Making

The Scorpius-Centaurus OB association is a collection of several hundred O and B-class stars some 470 light years from the Sun. Although the stars are not gravitationally bound, they are roughly the same age — 10 to 20 million years — their formation triggered by a series of supernovae explosions in large molecular clouds. Now the Gemini Planet Imager on the Gemini South instrument in Chile has uncovered a young planetary system within the association, one with solid similarities to our own Solar System in its infancy.

In fact, says lead author Thayne Currie (Subaru Telescope), the ring orbiting the star HD 115600 could be a Solar System clone. “It’s kind of like looking at [our] outer solar system when it was a toddler,” the astronomer adds, noting that the ring is about the same distance from its host star as the Kuiper Belt is from the Sun, receiving about the same amount of light from an F-class star that is about fifty percent more massive than our own G-class Sol.

Image: The F-class star HD 115600 showing a bright debris ring viewed nearly edge-on and located just beyond a Pluto-like distance to its star. One or more unseen planets are causing the disk center to be offset from the star’s position (cross). Credit: Thayne Currie/NAOJ.

Distortions in the observed debris disk indicate that it is interacting with at least one thus far unseen planet, creating an eccentricity in the disk itself that is among the largest yet observed. A gas giant of Jupiter or Saturn class could explain the distortions, but there are also other possibilities depending on the models used — the researchers explored ‘gap opening’ models as well as ‘planet stirring’ explanations. From the paper:

Interior to ∼ 30 AU only a superjovian-mass planet can sculpt the ring by gap opening… Planets with masses and semimajor axes comparable to the outer solar system planets could stir the disk to appear as a bright debris ring with an eccentricity of 0.1–0.2 (e.g. a Saturn with e = 0.2). In both cases, Super-Earths just interior to the ring edge could sculpt the ring.

So we have a range of planetary possibilities here amidst a disk whose spectrum shows similarities to the Kuiper Belt, with a composition of ice, silicates and dust, although the researchers note that HD 115600’s disk is, in comparison with other debris disks, more efficient at scattering starlight, implying a higher percentage of ices:

HD 115600’s disk is reflecting light more efficiently than HR 4796A’s disk while having less thermal emission, a result explicable if HD 115600s disk is dominated by higher albedo species like water-ice. Multi-wavelength photometry/spectroscopy is needed to more decisively assess the composition of HD 115600’s disk.

Even so, it’s clear that HD 115600 is a promising source for further information about the early development of disks like the Kuiper Belt, with clear evidence for the sculpting effects of at least one planet. This work was conducted with the Gemini Planet Imager, a new generation of adaptive optics instruments whose numbers are soon to grow. The HD 115600 system thus becomes a useful reference as we tighten our focus on planet-disk interactions.

The paper is Currie et al., “Direct Imaging and Spectroscopy of a Young Extrasolar Kuiper Belt in the Nearest OB Association,” in press at The Astrophysical Journal Letters (preprint). A Subaru Telescope news release is available.

June 1, 2015

LightSail Reboots: Sail Deployment Soon

It was a worrisome eight days, but LightSail has broken its silence with an evident reboot and return to operations, sending telemetry to ground stations and taking test images. We now have sail deployment possibly as early as Tuesday morning EDT (15:44 UTC), but according to The Planetary Society’s Jason Davis, much will depend on today’s intensive checkout.

Planetary Society CEO Bill Nye issued this statement on the spacecraft’s reawakening:

“Our LightSail spacecraft has rebooted itself, just as our engineers predicted. Everyone is delighted. We were ready for three more weeks of anxiety. In this meantime, the team has coded a software patch ready to upload. After we are confident in the data packets regarding our orbit, we will make decisions about uploading the patch and deploying our sails— and we’ll make that decision very soon. This has been a rollercoaster for us down here on Earth, all the while our capable little spacecraft has been on orbit going about its business. In the coming two days, we will have more news, and I am hopeful now that it will be very good.”

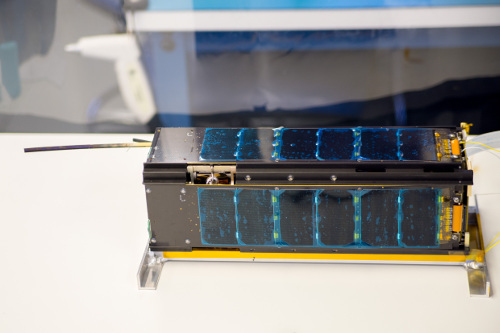

Image: LightSail-A back in August of 2014 during a testing period at Cal Poly. The craft is a three-unit CubeSat no larger than a loaf of bread, but it packs 32 square meters of sail inside. Four metal booms will, if all goes well, unfold the craft’s four triangular sails. Credit: The Planetary Society.

What we get from Davis is largely positive (see LightSail Team Prepares for Possible Tuesday Sail Deployment). The diminutive craft made twelve passes over the Cal Poly and Georgia Tech ground stations on Sunday, returning 102 data packets. You’ll recall that errant software was suspected in LightSail’s problems, with engineers crafting a software patch that they tried unsuccessfully to upload. The trick is that the satellite is tumbling, able to receive some commands and transmit data, but lacking the kind of stable downlink that would allow the software changes to be made. For that reason, the patch idea is now being abandoned.

Instead, a series of reboots will keep the beacon.csv file reset so that it doesn’t fill up and crash the system. Understandably, the LightSail team wants to begin sail deployment as soon as it is safe to do so. We should have a final decision on a possible Tuesday deployment by Monday night. We’re going to find out what effect the spacecraft’s tumble has on sail deployment the hard way. As Davis noted in an earlier post:

… the rotation rate has increased from -7, -0.1 and -0.3 degrees per second about the X, Y, and Z axes to 10.8, -7.3 and 2.9 degrees. The cause for the tumbling uptick currently unknown, but with the spacecraft’s attitude control system offline [see What Images Will We Get Back from the LightSail Test Mission?], sail deployment is likely to be a wild ride.

The best Tuesday ground pass window begins at 11:44 EDT. To keep up with the latest, follow Jason’s Twitter account @jasonrdavis, and we’ll see just how wild a ride it is. Remember, this mission is not designed to demonstrate controlled solar sailing, but serves as a test of the craft’s attitude control system and sail systems before it is pulled back into the Earth’s atmosphere. The tumbling we’re seeing now is obviously a concern because just next year the next LightSail mission is scheduled to perform controlled Earth-orbit sail flight. We’re going to need to find the bugs in this spacecraft’s attitude control system long before then.

May 28, 2015

Into Plutonian Depths

The image of Pluto on the right — an artist’s impression, to be sure (credit: NASA, ESA and G. Bacon, STScI) — suggests Ganymede to me more than Pluto, but we’ll have to wait and see what New Horizons turns up as it continues to close on its target. It’s worth thinking about how our views of this place have changed over time. The world found by Clyde Tombaugh seemed small enough when he found it, but a fraction of its light was actually coming from its yet smaller moon, which wouldn’t be discovered until USNO astronomer James Christy nailed it in 1978.

Gregory Benford depicted Pluto with a nitrogen sea in a 2006 novel called The Sunborn, one in which he explored the possibility of life at -185 degrees Celsius, the lifeforms themselves the result of an experiment by heliopause beings who drew energy from magnetic interactions far from the Sun. Even more speculative is Stephen Baxter’s story “Goose Summer” (from the Vacuum Diagrams collection of 2001), in which Plutonian life physically interacts with Charon, the latter ‘seeding’ the Plutonian surface.

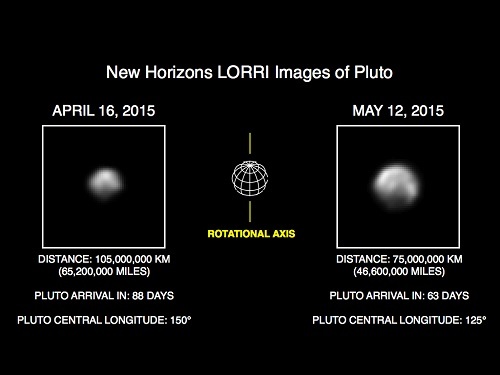

But the real thing beckons. We now have images taken between May 8 and 12, downlinked last week. Here we’re looking at Pluto from a distance of 77 million kilometers using the now familiar Long-Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) aboard New Horizons. The differences between this view and what we saw in April are striking. We’re now 35 million kilometers closer and have twice the pixels to work with, aided by image deconvolution techniques to tease out detail.

Here’s the May 12 imagery as contrasted with April 16 — a click on the New Horizons link will show you two other photo sets contrasting the earlier and later views.

Image: These images show Pluto in the latest series of New Horizons Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) photos, taken May 8-12, 2015, compared to LORRI images taken one month earlier. All images have been rotated to align Pluto’s rotational axis with the vertical direction (up-down), as depicted schematically in the center panel. Between April and May, Pluto appears to get larger as the spacecraft gets closer, with Pluto’s apparent size increasing by approximately 50 percent. Pluto rotates around its axis every 6.4 Earth days, and these images show the variations in Pluto’s surface features during its rotation. All of the images are displayed using the same linear brightness scale.

The deconvolution method used to sharpen the images can, the New Horizons team reminds us, sometimes create artifacts, meaning that we’ll need to have the smaller details of these images confirmed as New Horizons gets closer. According to mission project scientist Hal Weaver (JHU/APL), as quoted in the New Horizons update linked to above, we’ll be seeing images with 5000 times better resolution when we reach closest approach during the July 14 flyby.

Are we looking at a polar cap in this imagery? Mission principal investigator Alan Stern comments:

“These new images show us that Pluto’s differing faces are each distinct; likely hinting at what may be very complex surface geology or variations in surface composition from place to place. These images also continue to support the hypothesis that Pluto has a polar cap whose extent varies with longitude; we’ll be able to make a definitive determination of the polar bright region’s iciness when we get compositional spectroscopy of that region in July.”

We’re just seven weeks away from the flyby, with Stern now moving to the east coast for the encounter operations through late July. As excitement builds, a Pluto Safari smartphone app has appeared, available for iOS as well as Android. Produced by Simulation Curriculum Corp., the free app offers interactive views of the locations of Pluto and New Horizons, along with a timeline of New Horizons mission milestones and the latest news about the spacecraft. Pluto Safari is available here in its iOS version and here for the Android iteration.

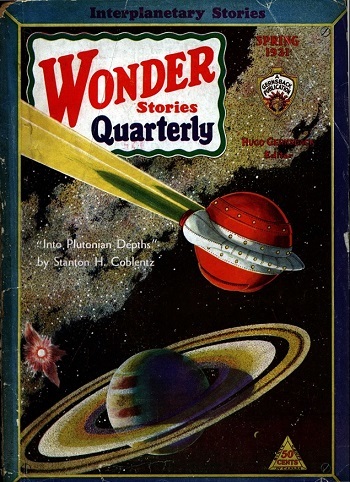

Meanwhile, looking over my collection of old science fiction magazines, I enjoyed tracking down Stanton A. Coblentz’ story “Into Plutonian Depths,” which ran in Wonder Stories Quarterly in the Spring 1931 issue. To my knowledge, this was the first story written with knowledge of Clyde Tombaugh’s discovery. Using a ‘gravity insulator,’ our protagonist and Stark, his science mentor, set out for the most distant planet known. Coblentz refers to ‘the trans-Neptunian planet’ found by Tombaugh and conjures up mystery in the name Pluto. As Stark exclaims:

“Think of it a billion miles or so beyond Neptune, a globe perhaps no larger than the earth, lost in the blackness of the outer void, its years longer than our centuries, its seasons longer than our lives! What stories it would be able to tell! Are there any living creatures there? Were any living beings ever able to endure the terror of its sunless, frozen plains? Would we find the imprint of lost races upon its shores? — races that flourished while the planet was heated from within, but that have long ago fallen in the struggle with the cold?”

And so on. It’s a lively tale, a bit mesmerizing in its day (though it goes on far too long), and it mimics the approach of New Horizons as it describes the travelers’ view of “silvery white plains and its broken and enormous mountain ranges, whose snowy summits were offset by sheer black escarpments and ravines as hideous to contemplate as the craters of the moon…” The inhabitants of the ninth planet turn out to be nothing like Benford or Baxter’s creations, and the tale turns into something closer to Rider Haggard than modern SF as it winds its way to a conclusion.

But still, what fun to think about Pluto as it was first envisioned in fiction while we have a spacecraft moving in on the Pluto/Charon system at 1.2 million kilometers per day. Each new set of New Horizons images is going to sharpen our view of a world. If only Stanton Coblentz, and for that matter Clyde Tombaugh himself, were able to watch this encounter unfold.

May 27, 2015

LightSail Glitch: Hoping for a Reboot

The Planetary Society’s LightSail won’t stay in orbit long once its sail deploys, a victim of inexorable atmospheric drag. But we’re all lucky that in un-deployed form — as a CubeSat — LightSail can maintain its orbit for about six months. Some of that extended period may be necessary given the problem the spacecraft has encountered: After returning a healthy stream of data packets over its first two days of operations, the solar sail mission has fallen silent.

Jason Davis continues his reporting on LightSail, with the latest update on the communications problem now online. We learn that the suspected culprit for LightSail’s silence is a simple software glitch. Everything else looked good when communications ceased, with power and temperature readings stable. Davis explains that during normal operations, LightSail transmits a telemetry beacon every 15 seconds. The Linux-based flight software writes data on each transmission to a .csv file, a spreadsheet-like record of ongoing procedures.

This file continues to grow, and when it reaches a certain size, trouble can happen:

As more beacons are transmitted, the file grows in size. When it reaches 32 megabytes—roughly the size of ten compressed music files—it can crash the flight system. The manufacturer of the avionics board corrected this glitch in later software revisions. But alas, LightSail’s software version doesn’t include the update.

Late Friday, the team received a heads-up warning them of the vulnerability. A fix was quickly devised to prevent the spacecraft from crashing, and it was scheduled to be uploaded during the next ground station pass. But before that happened, LightSail fell silent. The last data packet received from the spacecraft was May 22 at 21:31 UTC (5:31 p.m. EDT).

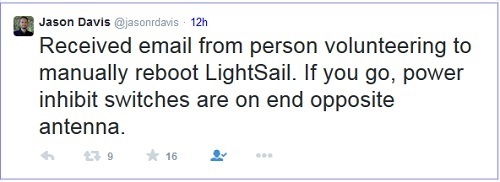

Let’s hope we’ll still see a deployed LightSail, as in the image above. But anyone who has stared at a PC frozen into immobility knows the feeling that LightSail’s ground controllers must have experienced. The machine is not responding, which means it’s time for a reboot. A manual reboot being out of the question, a reboot command from the ground has to be used, and more than one has been sent. In fact, Cal Poly has been transmitting a new reboot command every few ground station passes. So far, no luck.

A fix may still be in the works from a natural source, but first, the situation led to a bit of humor, in the form of an email Davis received, as recorded in this tweet:

Davis also suggests a LightSail successor to be called BourbonSat, a flight spare that sits in each team member’s kitchen to offer quick stress relief. The humor is edgy but that’s because we may now be reliant on a hands-off fix: Charged particles striking an electronic component in just the right way to cause a reboot. If that sounds extreme, be aware that the phenomenon is not unusual in CubeSats. In fact, Cal Poly’s experience says that most reboot within the first three weeks of operations. You can place this in the context of the 28-day sail deployment timeline and see we might come out just fine.

What happens next depends upon when — and if — that reboot occurs, assuming the continued reboot commands from the ground are not effective. Various software fixes are being tested to see which could be inserted after contact is restored, so that the troublesome .csv file doesn’t cause further problems. Davis also says that when LightSail comes back online, the team will probably begin a manual sail deployment as soon as possible. Let’s make sure, in other words, that when we have a communicating spacecraft, we do what we sent it out there to do.

Paul Gilster's Blog

- Paul Gilster's profile

- 7 followers