Paul Gilster's Blog, page 114

January 24, 2018

M-Dwarf Planets: ExTrA and TRAPPIST-1

A new project called Exoplanets in Transits and their Atmospheres (ExTrA) has been set in motion at the European Southern Observatory’s site at La Silla (Chile). Funded by the European Research Council and the French Agence National de la Recherche, ExTrA’s three 0.6-metre telescopes will be operated remotely from Grenoble, France. This is an exoplanet transit effort centered around finding and characterizing Earth-sized planets orbiting M-dwarf stars.

Not an easy task from the ground, as lead researcher Xavier Bonfils makes clear, though if you’re going to attempt it, northern Chile offers optimum conditions:

“La Silla was selected as the home of the telescopes because of the site’s excellent atmospheric conditions. The kind of light we are observing — near-infrared — is very easily absorbed by Earth’s atmosphere, so we required the driest and darkest conditions possible. La Silla is a perfect match to our specifications.”

To do its work, ExTrA weds spectroscopic information to traditional photometry. The collected light from the target star is fed through optical fibres into a multi-object spectrograph. Known as differential photometry, the method involves collecting light not only from the target but also from four comparison stars. The comparison helps the technology filter out atmospheric distortions and effects produced by the instruments and detectors themselves.

Image: A new national facility at ESO’s La Silla Observatory has successfully made its first observations. The ExTrA telescopes will search for and study Earth-sized planets orbiting nearby red dwarf stars. ExTrA’s novel design allows for much improved sensitivity compared to previous searches. Astronomers now have a powerful new tool to help in the search for potentially habitable worlds. Credit: ESO.

Bonfils adds:

“With the next generation of telescopes, such as ESO’s Extremely Large Telescope, we may be able to study the atmospheres of exoplanets found by ExTra to try to assess the viability of these worlds to support life as we know it. The study of exoplanets is bringing what was once science fiction into the world of science fact.”

Thus ground-based observation continues to increase in precision, soon to be supplemented by space missions like the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and the European CHaracterising ExOPlanet Satellite (CHEOPS).

Close Look at TRAPPIST-1

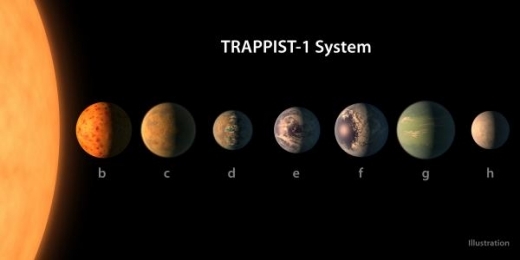

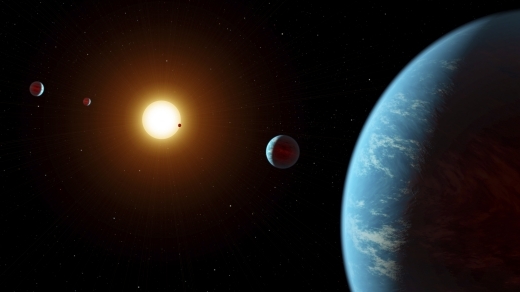

And while we’re talking about M-dwarfs, a new paper is out looking at one of the most interesting systems yet discovered, comprising the seven planets around TRAPPIST-1. Lead author Amy Barr (Planetary Science Institute) and colleagues go to work on the interior structures of these planets as well as their tidal heating and convection given what we know about their mass and radius. The balance between tidal heating and convective transport has implications for the mantles of each planet.

Image: A size comparison of the planets of the TRAPPIST-1 system, lined up in order of increasing distance from their host star. The planetary surfaces are portrayed with an artist’s impression of their potential surface features, including water, ice, and atmospheres. The paper from Amy Barr, Vera Dobos and László L. Kiss shows that planets d and e are the most likely to be habitable due to their moderate surface temperatures, modest amounts of tidal heating, and because their heat fluxes are low enough to avoid entering a runaway greenhouse state. Planet d is likely covered by a global water ocean. Credit: NASA/R. Hurt/T. Pyle.

Given that their orbits are slightly eccentric, there is the possibility of tidal heating, which in the Galilean moons has intrigued us for its possibilities at providing an energy source for life beneath an icy crust, and indeed, the paper notes that “…on planets b, e, f, g and h, life might appear in the tidally heated (subsurface) ocean close to hydrothermal vents.“

In the TRAPPIST-1 system, though, we have much to learn about the composition of the respective worlds. The Barr paper examines the limits of present knowledge:

Assuming the planets are composed of water ice, rock, and iron, we determine how much of each might be present, and how thick the different layers would be. Because the masses and radii of the planets are not very well-constrained, we show the full range of possible interior structures and interior compositions.

The paper is a thoroughgoing examination of the TRAPPIST-1 planets, with planets d and e flagged as the most likely to produce habitable conditions. Here tidal heating would be modest and heat flux low enough to avoid runaway greenhouse conditions:

Planet d is likely to be covered by a global water ocean, and can be habitable if its albedo is ≳ 0.3. Planetary albedos may be estimated from photometric measurements during occultations (see e.g. Rowe et al., 2008) which may give an additional constraint on the habitability of TRAPPIST-1d. As discussed in Section 5, planet e is likely to have liquid water on its surface, too, according to climate models (Turbet et al., 2017; Wolf, 2017).

Planets f, g, and h, the authors believe, are rich in H2O, possibly containing liquid water oceans beneath a thick ice mantle. Planets b and c likely harbor magma oceans in their interiors. Planet b in particular demands further work, given its proximity to the central star and its “seemingly water-rich composition,” while c may experience eruptions from its magma ocean, a phenomenon that may eventually become detectable.

But note how far we have to go:

Our knowledge of the compositions of the four interior planets, chiefly, their water content, can significantly be improved if their masses can be determined to within ∼ 0.1 to 0.5M⊕, which will require further observations of the TRAPPIST-1 system.

The paper is Barr et al., “Interior Structures and Tidal Heating in the TRAPPIST-1 Planets,” accepted at Astronomy & Astrophysics (preprint).

January 23, 2018

Defining a Brown Dwarf / Planet Boundary

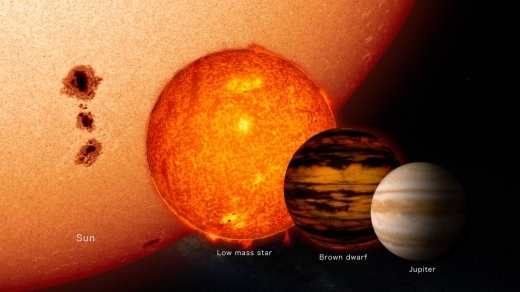

A paper that crossed my desk this morning proves timely in light of our recent discussions about brown dwarfs. Specifically, the question of when to declare an object a planet or a brown dwarf has come up, with the cutoff often cited at about 13 Jupiter masses. Now I see that Johns Hopkins’ Kevin Schlaufman is proposing a cutoff somewhere closer to 10 Jupiter masses, but the idea takes us beyond mass as the determinant of the object’s status.

We tend to turn toward the IAU Working Group on Extrasolar Planets for our ideas on the planet/brown dwarf distinction, though the fact that we can find objects with 10 times Jupiter’s mass both in orbit around stars and also in isolation makes the definition a challenging one. The IAU has defined a planet as an object with a mass below the limiting mass for deuterium fusion that orbits a star or stellar remnant. Objects above this limiting mass have been defined as brown dwarfs, no matter how they formed or where they are located. This is where the 13 Jupiter mass cutoff comes from, although other models have also been proposed.

Image: Johns Hopkins astrophysicist Kevin Schlaufman has proposed a new definition of a planet. Credit: Johns Hopkins University.

But this gets tricky, because much depends on composition — the mass needed for deuterium fusion depends on the object. Under this definition, a metal-poor object of 13 Jupiter masses would be considered a planet, while a metal-rich object of the same mass would be considered a brown dwarf. Nor does this definition take into account formation models.

Schlaufman has made a close study of some 146 planetary systems in his efforts to distinguish between huge planets and tiny brown dwarfs. As the paper says:

This combined sample of 146 giant planets, brown dwarfs, and low-mass stars that have Doppler-inferred masses and transit solar-type primaries (most with homogeneously derived stellar parameters) is the best sample available to calculate the mass at which low-mass secondary companions no longer preferentially orbit metal-rich solar-type primaries.

Mass, in Schlaufman’s view, is simply not enough of a determinant when making the call between planet and brown dwarf. Instead, he proposes looking at the chemical composition of host stars. Giant planets will be found orbiting stars with high metallicity because planets like Jupiter form by building up a rocky core that is later enveloped by a gaseous envelope — this is core accretion. Gas giants are invariably found orbiting dwarf stars that are rich in metals.

Brown dwarfs and stars, on the other hand, form from the top down, clouds of gas collapsing to produce the object through the model referred to as gravitational instability. And indeed, we don’t see brown dwarfs necessarily associated with stars with high metal content. In Schlaufman’s study, objects more massive than 10 times Jupiter mass can be found near stars with varying degrees of metal content. The lack of correlation tells the tale.

Thus the paper:

Celestial bodies with M ≲ 10 MJup preferentially orbit metal-rich solar-type dwarf stars, while celestial bodies with M ≿ 10 MJup do not preferentially orbit metal-rich solar-type dwarf stars. A preference for metal-rich host stars is thought to be a property of objects formed like giant planets through core accretion, while objects formed like stars through gravitational instability should not prefer metal-rich primaries. As a result, these data suggest that core accretion rarely forms giant planets with M ≳ 10 MJup and objects more massive than M ≈ 10 MJup should not be thought of as planets. Instead, objects with M ≳ 10 MJup formed like stars through gravitational instability.

Image: This illustration shows the average brown dwarf is much smaller than our sun and low mass stars and only slightly larger than the planet Jupiter. Credits: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

Usefully, we will soon be able to test this prediction at a new level of precision. Schlaufman is saying that planets in the mass range of 1 to 10 Jupiters should preferentially be found around metal-rich solar-type dwarf stars, while brown dwarfs between 10 and 80 Jupiter masses should be found around solar-type dwarf stars that span the entire range of metallicity. The European Space Agency’s Gaia mission is expected to find and characterize 21,000 ± 6000 giant planets and brown dwarfs, a sample large enough to put Schlaufman’s theories to the test.

The paper is Schlaufman, “Evidence of an Upper Bound on the Masses of Planets and Its Implications for Giant Planet Formation,” published online by The Astrophysical Journal 22 january 2018 (abstract/preprint).

January 22, 2018

Planet Mimicry: Disk Patterns in Infant Systems

The wrong initial assumption can easily lead anyone down a blind alley. The problem comes across loud and clear in new work from Marc Kuchner (NASA GSFC) and colleagues, which Kuchner presented at the recent meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Washington. At issue is the matter of the disks of gas and dust around young stars, in many of which we can find patterns such as rings, arcs and spirals that suggest the formation of planets.

But are such patterns sure indicators or merely suggestions? Kuchner’s team has been looking at the question for several years now, presenting in a 2013 paper the possibility that a phenomenon called photoelectric instability (PeI) can explain the narrow rings we see in some disk systems. PeI happens when high-energy ultraviolet light strikes dust and ice grains, stripping away electrons. The electrons then strike and heat gas in the disk, causing gas pressure to increase and more dust to be trapped. Rings can form that begin to oscillate, along with arcs and clumps — bright, moving sources of light that could be mistaken for planets.

Photoelectric instability is a cascading phenomenon as rising gas pressure affects the orbiting dust, with clumps forming with many times the dust density found elsewhere in the disk. In the new paper, submitted to The Astrophysical Journal, Kuchner and Wladimir Lyra (California State University) worked with Penn State doctoral student Alexander Richert to factor in radiation pressure.

Photons have no mass but they do convey momentum. Conceive a dust particle as a tiny solar sail and consider how that momentum can push the dust surrounding a young star into highly eccentric orbits. The team shows that by including radiation pressure in their model, spirals like those found around the star HD 141569A, a star studied in the 2013 paper, can be created. These do not necessarily indicate a planet.

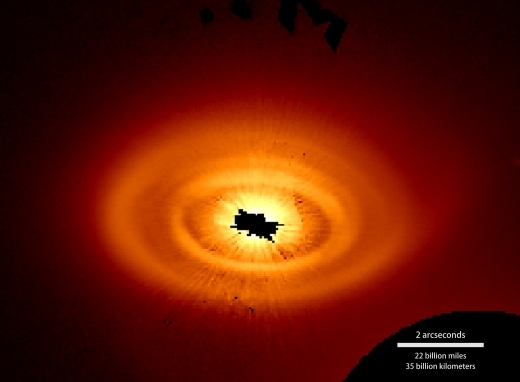

Image: Arcs, rings and spirals appear in the debris disk around the star HD 141569A. The black region in the center is caused by a mask that blocks direct light from the star. This image incorporates observations made in June and August 2015 using the Hubble Space Telescope’s STIS instrument. Credits: NASA/Hubble/Konishi et al. 2016.

“Carl Sagan used to say extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence,” Lyra said. “I feel we are sometimes too quick to jump to the idea that the structures we see are caused by planets. That is what I consider an extraordinary claim. We need to rule out everything else before we claim that.”

We can now view some prominent disk structures with an eye toward photoelectric instability, as the paper notes:

…the non-axisymmetric clumps and spiral arms seen in the gas distributions in several of our models suggest that interactions between gas and small-to-medium grains could underlie the asymmetric structures seen in the 49 Ceti and AU Mic edge-on disks (Hughes et al. 2017; Boccaletti et al. 2015), though explanations for the AU Mic moving blobs involving only rocky body collisions (no gas) have also been proposed (Sezestre et al. 2017; Chiang & Fung 2017). We also underscore that so far the PeI is the best candidate for producing arcs, a feature that is not predicted from planet-disk interaction. That the PeI leads to arcs was predicted by Lyra & Kuchner (2013), before the discovery of these features in the disk around HD 141569A (Perrot et al. 2016).

We’ve got a long way to go in studying these phenomena, and the new paper casts a critical eye on what physical processes and parameters still need to be explored, among them turbulence and varying types of dust and gas. This roadmap of future work should be useful, particularly as we try to extend these simulations beyond stars like the Sun into the realm, for example, of A-class stars. The point is that untangling the numerous conceivable interactions in young disks is necessary before we can construct truly accurate models of planet formation.

…planet–disk interactions in optically thin disks may manifest themselves very differently than they do in existing, simpler models. The formation of gaps, rings, and other disk morphologies associated with planets may be inhibited, enhanced, or otherwise affected by the presence of gas.

Go easy on the assumptions, in other words, and tune up the modeling of infant stellar systems. What looks for all the world to be planets in formation may yet prove an earlier stage of system evolution. Run on the Discover computing cluster at NASA GSFC, the Kuchner team’s simulations are showing just how complicated the interactions in a young disk can be.

The paper is Richert et al., “The interplay between radiation pressure and the photoelectric instability in optically thin disks of gas and dust,” submitted to The Astrophysical Journal (preprint). The 2013 paper is Kuchner and Lyra, “Formation of sharp eccentric rings in debris disks with gas but without planets,” Nature 499 (11 July 2013), pp. 184-187 (abstract). Kuchner also heads up a citizen science project called Disk Detective that has produced 2.5 million classifications of potential disks.

January 19, 2018

K2-138: Multi-Planet System via Crowdsourcing

As Centauri Dreams readers know, I always keep an eye on the K2 mission, the rejuvenated Kepler effort to find exoplanets with a spacecraft that had originally examined 145,000 stars in Cygnus and Lyra. Now working with different fields of view, K2 has examined a surprisingly large number of stars, some 287,309, according to this Caltech news release. Digging around a bit, I discovered that each 80-day campaign brings in data on anywhere from 13,000 to 28,000 targets, all released to the public within three months of the end of the campaign. In the paper we’ll discuss today, this influx is referred to as a ‘deluge of data.’

Our datasets just continue to grow in a time of exploration that seems unprecedented in scientific history. I’ve heard it compared to the explosion in knowledge of microorganisms after their detection by van Leeuwenhoek in the 17th Century, though of course it also conjures up thoughts of early exploratory voyages as humans pushed into hitherto unknown terrain. But given that we are finding exoplanets in huge variety and by the thousands, this era surely has an edge because of the speed with which it is happening and its related search for life.

No wonder that public interest is high, and it’s gratifying to see projects like Exoplanet Explorers available (through the Zooniverse site) to serve as a platform for crowdsourced research. Exoplanet Explorers sifts through K2 data to look for transiting planets, with calibrated data files up through Campaign 14 (C14) and the uncalibrated data from Campaign 15 now available. The project, which went online for the first time last April, has already snagged, among other things, a highly interesting multi-planet system dubbed K2-138, and in a highly visible way.

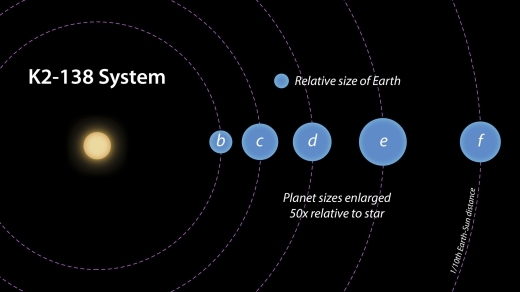

Image: Artist’s visualization of the K2-138 system, the first multi-planet system discovered by citizen scientists. The central star is slightly smaller and cooler than our sun. The five known planets are all between the size of Earth and Neptune; planet b may potentially be rocky, but planets c, d, e, and f likely contain large amounts of ice and gas. All five planets have orbital periods shorter than 13 days and all are incredibly hot, ranging from 425 to 980 degrees Celsius. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/R. Hurt (IPAC).

Potential transit signals can be spotted by computers using signal-processing algorithms, but detections can be iffy. Many features that might seem to flag a transit can turn out to be astrophysical in origin, everything from eclipsing binaries to flare stars, pulsating variables, even cosmic-ray pixel strikes. We also have to account for instrument issues like spacecraft pointing drift. All this makes human eyes on the data a sensible idea, for the human brain is optimized for pattern matching and has proven successful at distinguishing between transits and artifacts.

Exoplanet Explorers runs a signal detection algorithm first to identify potential transit signals and then asks its users to examine the resulting candidates. K2-138 is the first K2 planetary system discovered by the project, and the first multi-planet system found entirely by crowdsourcing.

To help boost interest among the public, UC-Santa Cruz astronomer Ian Crossfield and Caltech staff scientist Jessie Christiansen worked with a British TV show, in co-production with ABC Australia, called Stargazing Live. Last April they introduced Exoplanet Explorers in a three-day event. The enthusiasm for crowdsourcing exoplanet research became immediately evident, as over 2 million classifications came in from more than 10,000 users, some of them analyzing the C12 dataset, which had yet to be examined by professional astronomers.

The quickly identified planet candidates included 44 Jupiter-sized planets, 72 Neptune-sized, 44 Earth-sized, and 53 ‘Super Earths.’ Each potential transit is looked at by a minimum of 10 volunteers using the Exoplanet Explorers platform, with each needing a minimum of 90 percent positive votes to proceed to further characterization. Crossfield and Christiansen determined to look for a signal likely to be confirmed for discussion on the show’s last night.

“We wanted to find a new classification that would be exciting to announce on the final night, so we were originally combing through the planet candidates to find a planet in the habitable zone—the region around a star where liquid water could exist,” says Christiansen. “But those can take a while to validate, to make sure that it really is a real planet and not a false alarm. So, we decided to look for a multi-planet system because it’s very hard to get an accidental false signal of several planets.”

Within the crowdsourced data, Christiansen and colleagues found a star with four planets, three of the four with 100 percent ‘yes’ votes from over 10 volunteers and a fourth with 92 percent. Having announced the discovery on Stargazing Live, the scientists went to work on K2-138, determining that the four planets orbit in a resonance, and finding a fifth planet on the same chain of resonances, with some possibility of a sixth. The five planets are all sub-Neptune in size, ranging from 1.6 to 3.3 Earth radii. All have periods under 13 days, making this an example of a tightly packed system of small planets.

Image: Artist’s concept of a top-down view of the K2-138 system discovered by citizen scientists, showing the orbits and relative sizes of the five known planets. Orbital periods of the five planets, shown to scale, fall close to a series of 3:2 mean motion resonances. This indicates that the planets orbiting K2-138, which likely formed much farther away from the star, migrated inward slowly and smoothly. Credit: Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/R. Hurt (IPAC).

In a paper accepted at The Astronomical Journal, the scientists describe the discovery and characterization of the system, calling it:

…a compact system of five sub-Neptune sized planets orbiting an early-K star in a chain of successive near-first-order resonances; in addition, the planets are locked in a set of three-body Laplace resonances. The planets may be accessible to mass measurement via dedicated radial velocity monitoring, and possibly via TTVs with improved timing precision.

and going on to note:

The Exoplanet Explorers project has provided an additional 68 candidate planets from the C12 light curves that likely contain additional planet discoveries, and we plan to upload potential detections for consideration from the rest of the available K2 campaigns.

These may be interesting planets, as the paper notes, for atmospheric characterization. In any case, multi-planet systems are useful as laboratories for planet formation, allowing us to test models of migration and system evolution. Caltech’s Konstantin Batygin, who was not involved in the paper, points to the “…rather gentle and laminar formation environment of these distant worlds.” It’s an interesting point also echoed by Christiansen. Chaotic scattering of materials in an early planetary system seems unlikely to produce quite so orderly a configuration.

The paper is Christiansen, Crossfield et al., “The K2-138 System: A Near-resonant Chain of Five Sub-Neptune Planets Discovered by Citizen Scientists,” accepted at The Astronomical Journal (preprint).

January 18, 2018

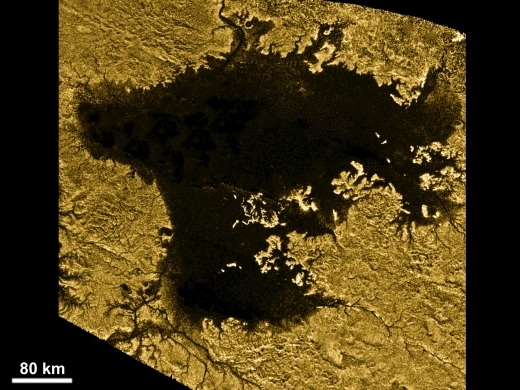

New Titan Findings from Topographical Map

Cassini’s huge dataset will yield discoveries for many years, as witness the global topographical map of Titan that has been assembled by Cornell University astronomers. The map draws on topographical data of the moon from multiple sources by way of studying its terrain and the flow of its surface liquids. Bear in mind that only 9 percent of Titan has been observed at relatively high resolution, and another 25-30 percent at lower resolution. For the remainder, the team mapped the surface using an interpolation algorithm and a global minimization process described in the first of two papers in Geophysical Review Letters.

The methods are complex and described in detail in the paper. For our purposes, let’s look at the result:

We present updated topographic and spherical harmonic maps of Titan making use of the complete Cassini RADAR data set for use by the scientific community. These maps improve on previous efforts (Lorenz et al., 2013; Mitri et al., 2014) through their increased coverage, higher resolutions, a global minimization of the data, and incorporation of observational errors, with the intent to serve a broader range of studies within the Titan community.

What stands out here are new mountains, none of them higher than 700 meters, and a global view of Titan’s topography that confirms that two locations in the equatorial region are depressions, a sign of cryovolcanic flows or, perhaps, ancient, now dried seas. There is also an implication that Titan’s crust may be more variable in thickness than previously believed, for the map shows a flatter (more oblate) Titan than our view up until now has suggested.

Three significant results emerge in the second of the two papers. We learn that Titan’s three seas share a common equipotential surface; i.e., a sea level. Although Titan’s seas are filled with hydrocarbons instead of water and are surrounded with a water ice bedrock, they do, just like Earth’s oceans, follow a constant elevation relative to Titan’s gravitational pull. Put another way, the oceans on Titan are all at the same elevation, the result of either flow through the subsurface between them or actual channels between the seas allowing liquid flow.

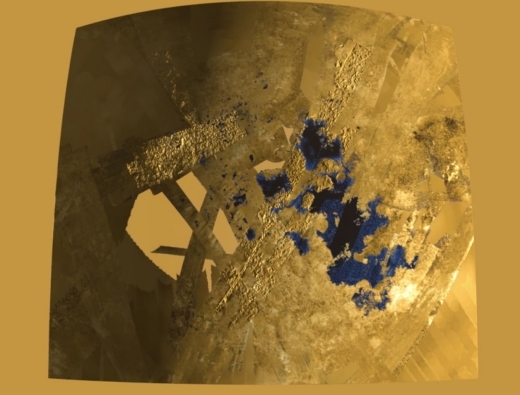

Image: Ligeia Mare, shown here in a false-color image from NASA’s Cassini mission, is the second largest known body of liquid on Saturn’s moon Titan. It is filled with liquid hydrocarbons, such as ethane and methane, and is one of the many seas and lakes that bejewel Titan’s north polar region. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/ASI/Cornell.

Here’s Cornell’s Alex Hayes, senior author on the paper, describing the finding:

“We’re measuring the elevation of a liquid surface on another body 10 astronomical units away from the sun to an accuracy of roughly 40 centimeters. Because we have such amazing accuracy we were able to see that between these two seas the elevation varied smoothly about 11 meters, relative to the center of mass of Titan, consistent with the expected change in the gravitational potential. We are measuring Titan’s geoid. This is the shape that the surface would take under the influence of gravity and rotation alone, which is the same shape that dominates Earth’s oceans.”

Thus the seas form a sea level, although, again like Earth, smaller lakes can appear at elevations several hundred meters higher than Titan’s sea level — this suggests that the lakes are isolated from the seas. There is also evidence in the topographical work that Titan’s lakes within a given ‘watershed’ communicate with each other through the subsurface. The floors of empty lakes are all at higher elevations within a watershed than any nearby filled lakes. No empty lakes are found below nearby filled lakes because they would then fill. An active flow has to be at work here in the form of liquid hydrocarbons below the surface.

From the paper:

Formation cannot involve significant fluvial processes unless the widths of the resulting channels and/or valleys remain smaller than the ~300 m resolution of the Cassini RADAR. Regardless, fluvial channels cannot be the dominant method for removing material from the basin. Within a regional topographic basin, the lakes appear dynamically linked such that their fill state is determined by the elevation of their basin floors as compared to the local phreatic surface or impermeable boundary.

Image: This frame from a colorized flyover movie from NASA’s Cassini mission shows the two largest seas on Saturn’s moon Titan and nearby lakes. The liquid in Titan’s lakes and seas is mostly methane and ethane. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/ASI/USGS.

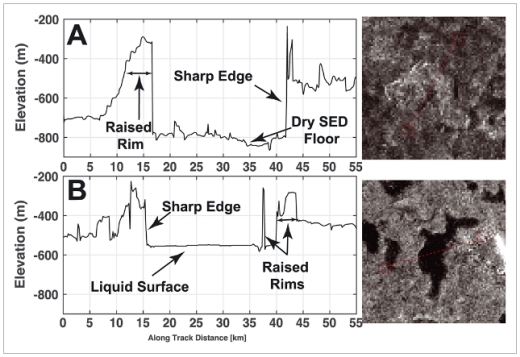

Titan’s lakes, concentrated in the polar regions, prove to be curiosities. Most of them are in depressions with sharp edges that, says Hayes, “literally look like you took a cookie cutter and cut out holes in Titan’s surface.” The ridges surrounding the lakes can be hundreds of meters high in some areas, making the lakes topographically closed; they stand out starkly from the surrounding undulating plains. Understanding the process that shapes these lakes and their sharply defined edges will be key to making sense of the evolution of the polar basins on Titan.

Image: This is Figure 1 from the “Topographic Constraints on the Evolution and Connectivity of Titan’s Lacustrine Basins” paper. Caption: Closest-approach altimetry profiles an unfilled and filled SED observed in (a) May 2007 (T30) and (b) April 2017 (T126), respectively. The profiles were processed to improve along-track resolution using the delay-Doppler algorithm described in Michaelides et al. (2016). Note that raised rims border the steep-sided depressions in both the empty and filled SEDs. Credit: Hayes et al.

The sharp-edged depressions, referred to in the paper as SEDs, are a unique feature of Titan, as the second of the two papers on the topographical map makes clear:

SEDs include the majority of Titan’s smaller lakes and are morphologically distinct from the larger, broad depressions (Hayes, 2016). The morphologic similarities between filled and empty SEDs have been used to suggest that dry SEDs represent previously filled, but now empty, lakes (Hayes et al., 2008). The spatial ubiquity and distinct morphologic expression of the SEDs make them a distinctive landform of Titan’s polar terrain (e.g., Aharonson et al., 2014).

First author Paul Corlies, a Cornell doctoral student, says that the data set aroused immediate interest among scientists, with the first inquiries about its use coming in within 30 minutes of the data being made available online. Out of this should come useful tweaks to our current models of Titan’s climate, as well as new work on interior models and studies of the moon’s gravity.

The papers are Corlies et al., “Titan’s Topography and Shape at the End of the Cassini Mission,” published online at Geophysical Research Letters 2 December 2017 (full text); and Hayes et al., “Topographic Constraints on the Evolution and Connectivity of Titan’s Lacustrine Basins,” published online at Geophysical Research Letters 2 December 2017 (full text).

January 17, 2018

Substellar Objects in Orion

Although I carry on about upcoming observatories on the ground and in space, I never want to ignore the continuing contribution of the Hubble telescope to our understanding of planet and star formation. As witness the latest deep survey made by team lead Massimo Robberto (Space Telescope Institute) and colleagues, which used the instrument to study small, faint objects in the Orion Nebula. At a relatively close 1,350 light years from Sol, the nebula is something of a proving ground for star formation, and now one that is yielding data on small stars indeed.

Identifying some 1,200 candidate reddish stars, the survey tapped Hubble’s infrared capabilities to extract 17 candidate brown dwarf companions to red dwarf stars, one brown dwarf pair and one brown dwarf with a planetary companion. We also learn that a planetary mass companion to a red dwarf has turned up as well as, interestingly enough, a planet-mass companion to another planet, the duo orbiting each other in the absence of a central star.

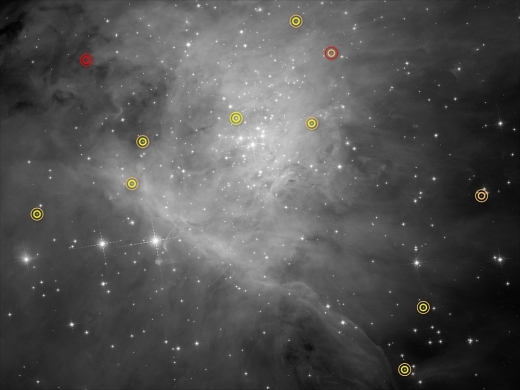

Image: This image is part of a Hubble Space Telescope survey for low-mass stars, brown dwarfs, and planets in the Orion Nebula. Each symbol identifies a pair of objects, which can be seen in the symbol’s center as a single dot of light. Special image processing techniques were used to separate the starlight into a pair of objects. The thicker inner circle represents the primary body, and the thinner outer circle indicates the companion. The circles are color-coded: Red for a planet; orange for a brown dwarf; and yellow for a star. Located in the upper left corner is a planet-planet pair in the absence of a parent star. In the middle of the right side is a pair of brown dwarfs. The portion of the Orion Nebula measures roughly 4 by 3 light-years. Credit: NASA , ESA, and G. Strampelli (STScI).

How to separate brown dwarf candidates from small red dwarfs? The technique in play was identification of water vapor in their atmospheres, which can peg cool red dwarfs as well, according to this Space Telescope Science Institute news release:

“These are so cold that water vapor forms,” explained Robberto. “Water is a signature of substellar objects. It’s an amazing and very clear mark. As the masses get smaller, the stars become redder and fainter, and you need to view them in the infrared. And in infrared light, the most prominent feature is water.”

The free-floating brown dwarfs and planets within the Orion Nebula are all new discoveries, a tribute to Hubble’s continuing role in astrophysical discovery. The search for binary companions to the 1,200 candidate stars in the original sample relied on high-contrast imaging techniques developed at STScI by Laurent Pueyo. The presence of water vapor in the atmospheres of the candidate companions is evidence that they are not the result of a chance alignment with background stars but rather must be brown dwarfs or exoplanet companions. Says Pueyo:

“We experimented with a method, high-contrast imaging post processing, that astronomers have been relying on for years. We usually use it to look for very faint planets in the close vicinity of nearby stars, by painstakingly observing them one by one. This time around, we decided to combine our algorithms with the ultra-stability of Hubble to inspect the vicinity of hundreds of very young stars in every single exposure obtained by the Orion survey. It turns out that even if we do not reach the deepest sensitivity for a single star, the sheer volume of our sample allowed us to obtain an unprecedented statistical snapshot of young exoplanets and brown dwarf companions in Orion.”

What other discoveries are waiting to be made in the Hubble archive? That data trove is soon to be complemented with the launch of the James Webb Space Telescope next year, an observatory designed to operate at infrared wavelengths.

Meanwhile, we have an early sample of low-mass objects early in the formation process, some of them solitary stars or brown dwarfs, others companions to other objects. Watching the formation process here may provide helpful insights into the boundary between star and planet as they evolve in such stellar nurseries.

January 16, 2018

Pulsar Navigation: Mining Our Datasets

Science fiction dealt with interstellar navigation issues early on. In fact, Clément Vidal’s new paper, discussed in these pages yesterday, notes a George O. Smith story called “Troubled Star,” which originally ran in a 1953 issue of Startling Stories and later emerged as a novel (Avalon Books, 1957). Smith is best remembered for a series of stories collected under the title Venus Equilateral, but the otherwise forgettable Troubled Star taps into the idea of using an interstellar navigation network, one that might include our own Sun.

The story includes this bit of dialogue between human and the alien being Scyth Radnor, the latter explaining why his civilization would like to turn our Sun into a variable star:

“We use the three-day variable to denote the galactic travel lanes. Very effective. We use the longer variable types for other things – dangerous places like cloud-drifts, or a dead sun that might be as deadly to a spacecraft as a shoal is to a seagoing vessel. It’s all very logical.”

“…you’re going to make a variable star out of Sol, just for this?”

Well, why not, in Scyth Radnor’s view — after all, what’s one star in a galaxy-spanning navigation network? From our point of view, distant pulsars make for less local disruption, and as we saw yesterday, navigation by X-ray millisecond pulsars is already undergoing testing.

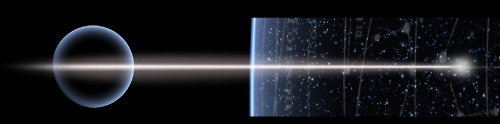

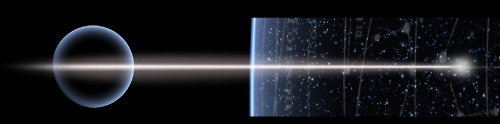

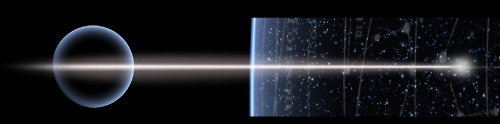

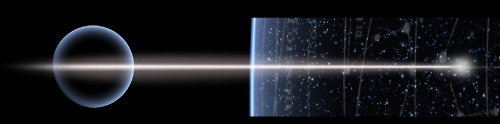

Image: Our early experiments, described yesterday, explore how we might use millisecond X-ray pulsars (MSPs) to provide autonomous spacecraft navigation. Credit: Astrowatch.net.

Visualizing a Pulsar Navigation Network

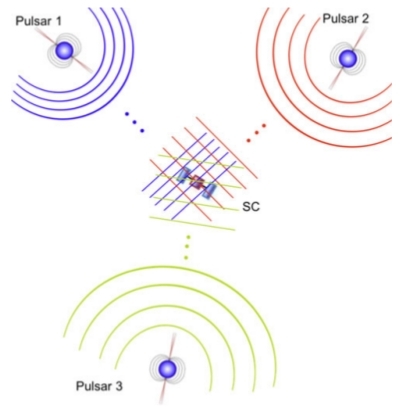

Using millisecond X-ray pulsars (MSPs) for galaxy-spanning navigation raises more than a few questions, especially when we try to predict what an artificial pulsar navigation system might look like to outside observers. If we are willing to posit for a moment a Kardashev II-level civilization moving between stars at relativistic velocities, then we would make as one of our predictions that such a system would be suitable for navigation at such speeds. In following the predictive model of Vidal’s paper, we would then check through our voluminous pulsar data to see how such a prediction fares. The answer, in other words, is in our datasets, and demands analyzing the viability of pulsar navigation at high fractions of c.

To my knowledge, no one has yet done this, making Vidal’s paper a spur to such research. The key here is to make predictions to see which can be falsified. But a quick recap for those just coming in on the discussion. What Vidal (Universiteit Brussel, Belgium) offers is an examination of millisecond X-ray pulsars as navigational aids, of the sort we’re already beginning to exploit through experiments via NASA, Chinese efforts and studies at the European Space Agency.

Specifically, the idea here is to develop a methodology for studying cases where astrophysical phenomena may have as one proposed explanation an extraterrestrial technology. Vidal also wonders whether we might find SETI implications even if a fully natural network like this were simply put to work by civilizations more advanced than our own, using it as we might wish to do.

Image: From Vidal’s paper, Fig. 4. Caption: A three-dimensional position fix can be obtained by observing at least three pulsars. Given three well-chosen pulsars, there is only one unique set of pulses that solve the location of the spacecraft (SC). Figure adapted from Sheikh (2005, 200).

Vidal is hoping to make predictions that are testable against our accumulating data to assess the likelihood of natural and artificial explanations, with pulsars as the case in point. The paper examines the kinds of predictions we would want to weigh against available data in a program the author calls SETI-XNAV. Whatever conclusions it reaches, such a program would improve our knowledge of pulsars themselves and our techniques at using them, possibly leading to our augmenting existing resources like the Deep Space Network with XNAV capabilities.

The author’s approach assumes that subjecting decades of data to analysis will teach us much about pulsar navigation as well as future SETI efforts:

Scientifically, SETI-XNAV is a concrete ETI hypothesis to test. The data is here, the timing and navigation functionalities are here. Historically, the suspicion of artificial canals on Mars triggered space missions to Mars and developed knowledge about Mars. Similarly, the project to try to decipher any potentially meaningful information in pulsar’s signals… could lead to the development of tools and methods that can be used for any future candidate signal.

That, of course, would augment the SETI effort as we expand into Dysonian SETI and the examination of possible engineering as the explanation for enigimatic astrophysical observations. If we assume a galaxy with a completely natural navigational system of this power, then we can imagine other civilizations putting it to use. Thus MSPs are likely to be standards in timekeeping and navigation for all putative civilizations in the Milky Way.

The Landscape of Prediction

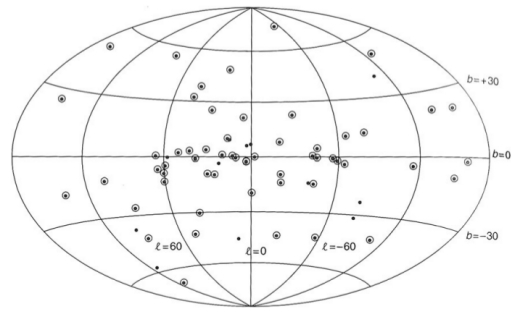

Millisecond pulsars account for perhaps 10% of known pulsars, and as I mentioned yesterday, they appear to be distributed isotropically in the galaxy, a contrast to the rest of the pulsar population, which appears more concentrated in the galactic disk. MSPs offer numerous advantages from a navigational standpoint given that, according to Vidal, they are more than 100,000 times more stable than normal pulsars. Timing noise, an irregularity found in normal pulsars, and so-called ‘glitches’ (abrupt changes in rotation speed) are less frequent in MSPs. The latter are also associated with lower velocities than the other 90 percent of the pulsar population.

From the standpoint of artificiality, Vidal breaks the possibility terrain down seven ways (this is drawn from the paper’s Figure 1):

0 – Natural. All pulsars are natural. We are just lucky they provide stable clocks and an accurate navigation system

1 – Pulsars as standards. All pulsars are natural, but ETIs use them for timing, positioning and navigation purposes. Communication is galacto-tagged and time-stamped with a pulsar standard

2 – Natural and alterable. Some ETIs have the technology and capability to jam, spoof or interfere with a natural pulsar positioning system

3 – Artificial MSXP for navigation. Only a few millisecond X-ray pulsars have been modified by ETI for galactic navigation and timing purposes

4 – Artificial MSXP for navigation and communication. Only a few MSXPs have been modified by ETI, for navigation, timing and communication purposes

5 – Artificial pulsars. All pulsars are artificial. ETI build them, even the new ones, by intentionally triggering supernovas

6 – Artificial pulsars for us. All pulsars are artificial. ETI build them and they are currently sending us Earth-specific messages

The point here is telling for Dysonian SETI in general. We have established pulsar formation models that seem to work. To establish a program of XNAV-SETI, examining our storehouse of pulsar data, we do not need to challenge it.

But as we have learned more about pulsars over the years, we have learned that there is no unified pulsar model that explains the variety we have seen among this population. We can look toward understanding what MSPs are doing by asking what new hypotheses explain this rich set of observations.

The wide range of Vidal’s seven scenarios makes his case straightforward: “…we do not necessarily need to contradict existing pulsar models to entertain the possibility that ETI might be involved.” The issue then becomes, Vidal adds, to make and validate new predictions.

Emergent Questions

Yesterday I mentioned a recent paper examining radio pulsars in a SETI context. It was Chennamangalam, Siemion, Lorimer & Werthimer, “Jumping the energetics queue: Modulation of pulsar signals by extraterrestrial civilizations,” New Astronomy Volume 34, January 2015, pp. 245-249 (abstract). The paper examines the possibility of pulsars as ‘naturally occurring radio transmitters’ onto whose emissions information has been encoded. Vidal likewise thinks about millisecond X-ray pulsars in the context of possible information content, noting that Carl Sagan pondered studying pulsar amplitude and polarization nulls as far back as 1973.

It might be argued that communications signals would likely be compressed, making decoding extremely problematic, but Vidal’s point here is that navigational systems differ in fundamental ways from communications systems. Navigational signals should be more regular and easier to process than highly modulated signals with communications intent. If we are looking for content grafted onto the navigational signal, we can bring to bear the entire SETI toolkit, perhaps examining pulsar data in light of delay-tolerant networking and discontinuities in connectivity.

We move back into the area of predictions. World clocks on Earth are regularly re-synchronized, just as the time on global positioning satellites is synchronized through methods Vidal discusses, using a control segment that communicates with a satellite segment. Can we observe anything like this in our pulsar data? The author frames the matter this way:

The fastest and most stable MSPs might constitute such a control segment, to which the other pulsars would synchronize. Concretely, we could look for time correction signals broadcasts (that exist in GNSSs [Global Navigation Satellite Systems]), or synchronization waves. For example, synchronization might occur first on pulsars nearest the putative control segment and then diffuse to further away pulsars. This could be investigated via rare MSP glitches, or other remarkable features, such as giant pulses in MSPs.

Synchronization between MSPs would be evidence for a distributed solution on an interstellar level.

Other questions to explore: Do we find that MSPs further away from the galactic plane are more powerful than those closer in, potentially designed for low-density regions of the galaxy? Is MSP distribution random or does it show a pattern fitting the needs of galactic navigation? Estimates of the number of MSPs needed to navigate the entire galaxy might be contrasted with astrophysical predictions of the MSP population, currently estimated to be between 30,000 and 200,000. This one, of course, is tricky: We can only derive a theoretical lower boundary.

How MSPs form and evolve is fruitful ground for inquiry, given that some scientists have argued that the most commonly cited scenario for MSP evolution does not produce the X-ray MSP population we see. It is hard to see how an MSP in a non-binary system can maintain its spin without degrading over time, making the single MSP ground for study. Thus another round of prediction is possible. Single MSPs, those without an energy source, may simply be non-working parts of the network. Do we see redundancy between single and binary MSP coverage, given that binary MSPs are likely more reliable over long time periods?

What Vidal calls SETI-XNAV makes a significant departure from conventional SETI in the sense that it is not localized around a single star, but rather involves a search for a distributed signal that exists in the form of a navigation system, one either established by extraterrestrial engineering or simply relying on a natural phenomenon to pursue its own activities. That we can begin to use millisecond X-ray pulsars as navigation standards implies that more advanced civilizations have done so. Thus SETI-XNAV as constructed in this paper intends to survey the testable predictions against which we can run our expanding dataset on pulsars.

…all pulsars could be perfectly natural, but we can reasonably expect that civilizations in the galaxy will use them as standards… By studying and using XNAV, we are also getting ready to receive and send messages to ETI in a galactically meaningful way. From now on, we might be able to decipher the first level of timing and positioning metadata in any galactic communication.

But I would also emphasize that making testable predictions about pulsar navigation also exercises our skills at analyzing future astrophysical data that may prove enigmatic. That, in and of itself, is a useful contribution in this era of KIC 8462852 and ‘Oumuamua.

The paper is “Pulsar positioning system: a quest for evidence of extraterrestrial engineering,” published online in the International Journal of Astrobiology 23 November 2017 (abstract / preprint). See also Vidal, “Millisecond Pulsars as Standards: Timing, Positioning and Communication,” Proceedings IAU Symposium No. 337, edited by P. Weltevrede, B. B. P. Perera, L. Levin Preston, and S. Sanidas. Jodrell Bank Observatory, UK (2017). Preprint available.

January 15, 2018

Pulsar Navigation: Exploring an ETI Hypothesis

Pulsar navigation may be our solution to getting around not just the Solar System but the regions beyond it. For millisecond pulsars, a subset of the pulsar population, seem to offer positioning, navigation, and timing data, enabling autonomous navigation for any spacecraft that can properly receive and interpret their signals. The news that NASA’s SEXTANT experiment has proven successful gives weight to the idea. Station Explorer for X-ray Timing and Navigation Technology is all about developing X-ray navigation for future interplanetary travel.

At work here is NICER — Neutron-star Interior Composition Explorer — which has been deployed on the International Space Station since June as an external payload. NICER deploys 52 X-ray telescopes and silicon-drift detectors in the detection of the pulsing neutron stars called pulsars. Radiation from their magnetic fields sweeps the sky in ways that can be useful. A recent demonstration used four millisecond pulsar targets — J0218+4232, B1821-24, J0030+0451, and J0437-4715 — to track NICER within a 10-mile radius as it orbited the Earth.

X-ray Pulsar Navigation (XNAV) has become an active area of research, pursued not just at NASA but by Chinese satellite testing and by conceptual studies at the European Space Agency. Having barely left our own planet, we are far ahead of ourselves to talk about a galactic positioning system for future spacecraft, but there is reason to believe that the principles of pulsar navigation can be extended to make accurate deep space navigation a reality.

Pulsars as Navigational Matrix

The SEXTANT experiment dovetails with a new paper from Clément Vidal (Universiteit Brussel, Belgium), whose work falls into the broader context of recent studies of unusual astrophysical phenomena. The author of the ambitious The Beginning and the End (Springer, 2014), Vidal’s work has been the subject of several articles in these pages (see, for example, A Test Case for Astroengineering and related entries accessible in the archives). In this era of the enigmatic KIC 8462852 and the interstellar object ‘Oumuamua, we have begun to ask how to address possible extraterrestrial engineering within the confines of rigorous astrophysics.

Millisecond pulsars may offer a way to examine such questions, but it is important to point out at the outset the Vidal is not arguing that this type of pulsar is evidence of extraterrestrial engineering. What he is trying to do is ask a question with broader implications. How do we study unusual astrophysical phenomena in ways that include an extraterrestrial hypothesis? How, in fact, do we conclude when that hypothesis is remotely relevant? And are there ways to make observable and refutable predictions that would help us distinguish purely astrophysical phenomena from what Vidal calls ‘astrobiological’ phenomena that imply intelligence?

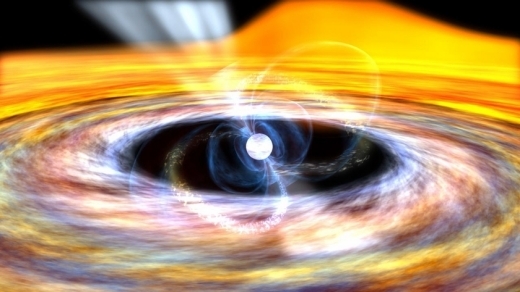

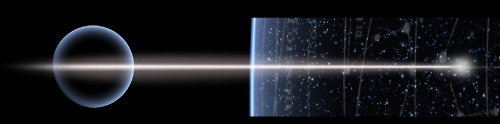

Image: An artist’s impression of an accreting X-ray millisecond pulsar. The inflowing material from the companion star forms a disk around the neutron star which is truncated at the edge of the pulsar magnetosphere. Credit & copyright: NASA / Goddard Space Flight Center / Dana Berry.

We’ve seen in the analysis of KIC 8462852 how many hypotheses have been put forward to explain that star’s unusual light curves, with more and more attention now being paid to a natural explanation involving dust in the system. Vidal’s lengthy paper examines the question of millisecond pulsars being useful for navigation, as with our own civilization’s global navigation satellite systems, like the Global Positioning System (GPS) or the Russian GLONASS (GLObal NAvigation Satellite System).

If we can derive a navigational methodology out of astronomical objects found throughout the galaxy, it seems reasonable to believe that more advanced civilizations would have deduced the same facts and might be using a pulsar positioning system (PPS) in their own activities. Pulsar navigation might thus have SETI potential — might some future SETI candidate signal contain timing and positioning metadata? Might some astrophysical phenomena like pulsars be modified by advanced cultures for use as beacons?

And if we push the issue to its conclusion, is it conceivable that what we see as a pulsar navigation capability is the result of deliberate engineering on a vast scale, the sort of thing we’ve imagined the builders of Dyson spheres and Kardashev Type II civilizations engaging in? Vidal does not argue that this is the case, but calls instead for using pulsar navigation as a way into what he calls SETI-XNAV, a program of research that would use existing and future astronomical data to examine millisecond pulsars in the context of testable predictions.

Vidal sees this as a way to “join pulsar astrophysics, astrobiology and navigation science,” one whose benefits would include developing new methods to design more efficient global navigation satellite systems here on Earth even as we explore how to refine our early XNAV experiments. Not incidentally, we would also be examining our methods when, as seems inevitable, we are confronted with another case of an astrophysical object that raises questions about possible artificial origins.

Implications of Galactic Navigation

An ETI hypothesis has played around the idea of pulsars from the beginning, with a brief interest in extraterrestrial technologies leading to the objects being nicknamed ‘LGM stars,’ for ‘Little Green Men.’ But as Vidal explains, models explaining pulsar behavior are available that invoke nothing but natural processes. It’s fascinating to see that Italian astrophysicist Franco Pacini predicted pulsars based on his studies of neutron stars some months before their discovery was announced by Jocelyn Bell and Anthony Hewish in 1967. Vidal goes on to say:

Pacini’s and [Thomas] Gold’s models were the very first modeling attempts. Pulsar astronomy has immensely progressed since then, and pulsars display a phenomenology that requires much more advanced models (see the section Pulsar behavior). There is no single unified pulsar model that can explain all the variety of observations… nobody predicted that our Galaxy would host some pulsars with pulsations rivaling atomic clocks in stability, or that their distribution would make them useful for an out-of-the-spiral galactic navigation system.

It’s a system we’ve begun to explore because of the need for autonomous navigation, in which a spacecraft is capable of navigating without recourse to resources on Earth or in nearby space. Homing in on millisecond pulsars (MSPs) as a unique subset of the broader population of pulsars, Vidal asks what observable predictions we might make that could help us distinguish natural phenomena from artificial. Galactic distribution turns out to be one such marker.

The distribution of MSPs is isotropic, while normal pulsars appear to be concentrated in the galactic plane. Because they are formed in binary systems, this distribution of MSPs causes us to ask why there would be more binary star systems outside the galactic disk than in it.

Image: Figure 7 from the Vidal paper. Caption: The distribution of MSPs in Galactic coordinates, excluding those in globular clusters. Binary MSPs are shown by open circles. From Lyne & Graham-Smith (2012, 116). Credit: Clément Vidal.

Bear in mind that while pulsar navigation became an early topic, proposed as far back as 1974 by JPL’s George Downs, it was the proposal to use X-ray pulsars instead of radio pulsars (Chester and Butman, 1981) that demonstrated both improved accuracy and the ability to use the kind of small detectors that would be feasible for inclusion in a spacecraft payload.

The discovery of X-ray millisecond pulsars shortly thereafter illustrated the difference between ‘normal’ pulsars and MSPs (for more on this, see Duncan Lorimer’s “Binary and Millisecond Pulsars,” Living Reviews in Relativity December 2008, 11:8; abstract here). Although there is much to say about this issue, for now keep in mind the key difference noted above: MSPs accrete matter from a companion. They are generally found in binary systems.

Now we enter the realm of prediction. If there is a case to be made for MSPs as evidence of engineering, we would expect them to be distributed in ways that would appear non-random. We would expect few redundancies in their coverage areas, and in terms of their numbers, there should be enough for galactic navigation but not necessarily more. Moreover, we would expect artificial navigation sources like X-ray millisecond pulsars to beam preferentially in the galactic plane. If we do not find these things, the astrophysical model is supported.

What emerges in this paper is a series of such predictions that can be used to examine our growing data about pulsar, and in particular MSP, behavior. The data offer a rich enough hunting ground that we can look at such things as MSPs in globular clusters as opposed to elsewhere in the galaxy. We find that about half of MSPs appear in globular clusters, a fact that supports an astrophysical explanation, since stellar encounters are likely in such quarters and thus the formation of the binary star systems that produce MSPs in the first place is to be expected.

If MSPs are engineered objects, we would expect different properties between cluster MSPs and those in the disk. We should examine such questions as beaming direction, which an astrophysical explanation would find to be random. We would study as well whether pulsar beaming overlaps with other pulsar beaming within such clusters. Such a study under the SETI-XNAV rubric might help us uncover new binary MSPs, Vidal asserts, by modeling the coverage areas of MSPs and searching in places where coverage would be non-existent. The prediction would then be that we should find an MSP filling in the putative coverage gap.

Vidal’s paper offers numerous areas for such investigation. SETI-XNAV, he writes:

…draws on pulsar astronomy, as well as navigation and positioning science to make SETI predictions. This concrete project is grounded in a universal problem and needs: navigation. Decades of pulsar empirical data is available and I have proposed nine lines of inquiry to begin the endeavor… These include predictions regarding the spatial and power distribution of pulsars in the galaxy; their population; their evolutionary tracks; possible synchronization between pulsars; testing the navigability near the speed of light; decoding galactic coordinates; testing various directed panspermia hypotheses; as well as decoding metadata or more information in pulsar’s pulses.

My interest is in seeing how Vidal makes the distinction between astrophysical and astrobiological — in other words, as with KIC 8462852 and the interstellar object ‘Oumuamua, are we making progress as we begin to investigate under what some have called the ‘Dysonian’ SETI paradigm? That approach takes its name from the postulated Dyson spheres that have been the subject of early work and continue to be studied through projects like the Glimpsing Heat from Alien Technologies (G-HAT) program at Penn State (see Jason Wright’s Glimpsing Heat from Alien Technologies for more). These issues will grow in relevance as our observational tools hasten the pace of discovery.

More thoughts on all this in my next post. The paper is Vidal, “Pulsar positioning system: a quest for evidence of extraterrestrial engineering,” published online in the International Journal of Astrobiology 23 November 2017 (abstract / preprint). Also of interest: Chennamangalam, Siemion, Lorimer & Werthimer, “Jumping the energetics queue: Modulation of pulsar signals by extraterrestrial civilizations,” New Astronomy Volume 34, January 2015, pp. 245-249 (abstract).

January 12, 2018

SETI and Astrobiology: Toward a Unified Strategy

Will we recognize life if and when we find it elsewhere in the cosmos? It’s a challenging question because we have only the example of life on our own world to work with. Fred Hoyle’s The Black Cloud raised the question back in 1957, a great memory for me because this was one of the earlier science fiction novels that I ever read. I remember sitting there with it in my 5th grade class in St. Louis, Missouri, having been loaned the paperback that had begun to circulate among my fellow students. I was mesmerized by the account of life as I had never imagined it.

Hoyle, you’ll recall, creates a vast cloud of gas and dust that turns out to be a kind of super-organism, and I leave the rest of this tale to those fortunate enough to be coming to it for the first time. But we’ve had the same conversation about Robert Forward’s ‘Cheela’ recently, living as they do on the surface of a neutron star. The question is one Jacob Bronowski circulated widely through his televised series The Ascent of Man back in the 1970s:

…it does not at all follow that the evolutionary path which life (if we discover it) took elsewhere must resemble ours. It does not even follow that we shall recognise it as life — or that it will recognise us.

Let’s talk about all this in terms of astrobiology and SETI. For many of us, the two have a seamless character. Detect a radio beacon from another civilization and you have, ipso facto, detected life or, at least, a technological product that life has produced. SETI then is clearly an aspect of astrobiology, just as the discipline also takes in lichen growing around a pond, or aquatic creatures of high intelligence but no technologies. With both SETI and our search for non-technological life, we’re hoping to detect living things that evolved elsewhere.

Thus I find myself in agreement with a new white paper that has been submitted to The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine as part of the process of carrying out upcoming decadal surveys in astronomy, astrophysics and planetary science. The authors are major figures from the SETI community: Jill Tarter and John Rummel (SETI Institute); Andrew Siemion (Berkeley SETI Research Center and Breakthrough Listen); Martin Rees (Breakthrough Listen, among so many other things); Claudio Maccone (chair, IAA SETI Permanent Committee); and Greg Hellbourg (International SETI Collaboration).

Titled “Three Versions of the Third Law: Technosignatures and Astrobiology,” the document makes the case that there has arisen an artificial distinction between astrobiology and SETI, with the former deemed acceptable for funding in ways that SETI has often not been, given the controversies in its history. As evidence, take the current 2015 NASA Astrobiology Strategy document, which baldly states: “While traditional Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI) is not part of astrobiology, and is currently well-funded by private sources, it is reasonable for astrobiology to maintain strong ties to the SETI community.”

Strong ties are good, surely, but the distinction is artificial. In what sense is SETI not part of astrobiology? As the white paper notes, the Galileo flyby described by Carl Sagan and fellow authors in a 1993 paper in Nature found that a critical lifemarker (for both life itself and intelligent life) was the presence of narrow-band, pulsed, amplitude modulated radio signals. This is the kind of data rejected by the exclusion of SETI from astrobiology.

This delightful quote from the white paper nails the issue:

This is an arbitrary distinction that artificially limits the selection of appropriate tools for astrobiology to employ in the search for life beyond Earth, one that it is not supported scientifically. The science of astrobiology recognizes life as a continuum from microbes to mathematicians. It is time to remove this artificial barrier, and to re-integrate the community of all those who wish to study the origin, evolution, and distribution of life in the universe.

From microbes to mathematicians indeed!

This is more than a matter of splitting hairs in academic documents, for how we define things can play a major role in how we as a society fund our scientific investigations. Here I would urge you to read the paper, which you can find here — click on ‘View the Submitted White Papers.’

Bear in mind the imminence of further debate. A meeting on Astrobiology Science Strategy for the Search for Life in the Universe will take place from January 16-18 in Irvine, CA, with a second meeting scheduled for March 6-8, 2018 in Washington, DC to discuss these matters. A unified astrobiology/SETI strategy may yet emerge from all this.

Background is everything in this discussion. It was in 1993 that funding for NASA’s High Resolution Microwave Survey was terminated, with SETI essentially being sent into the wilderness. The National Science Foundation actually prohibited SETI funding in language that was not removed until 2000. SETI then achieved eligibility for funding in 2001, according to NASA associate administrator Ed Weiler, even as the various astrobiology roadmaps leading up to today’s strategy at times included and at other times excluded SETI.

Similarly inconsistent have been the annual NASA funding efforts known as ROSES — Research Opportunities in Earth and Space Science. The white paper goes through the history of these changes.

There is no question that SETI has at various times become a political football, which accounts for its inclusions and exclusions from the astrobiology roadmaps of past years. We need a unified strategy sans politics. Goal 7 of previous astrobiology roadmaps has been stated as: “Determine how to recognize the signatures of life on other worlds.“ Searching for technosignatures is clearly one such method, leading the authors of the white paper to make their case:

It is time that we end this scientific schizophrenia. It is of course reasonable for a funding agency to elect not to fund any given proposal, but it is unscientific to exclude clearly related proposals from consideration. Historical politics or a perceived (but unverified) funding status from other sources should not enter into an estimation of the scientific value of an approach.

The title of the white paper, incidentally, is a nod to Arthur C. Clarke’s third law: “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” In this case, the quote is used to explore how difficult it may be to find extraterrestrial life of any kind. If intelligent, such life might build enormous structures observable by our astronomy.

Or perhaps not: Karl Schroeder has posited that advanced technologies may be indistinguishable not from magic but from nature. In other words, the future means continual advances in efficiencies “…until our machines approach the thermodynamic equilibria of their environment, and our economics is replaced by an ecology where nothing is wasted.” That’s yet another possibility for the so-called Great Silence.

We can’t know exactly where or how to look, which is why all feasible strategies have to be on the table in the search for biosignatures as well as technosignatures. The paper concludes:

There is no scientific justification for excluding SETI, or any other technosignature modality, from the suite of astrobiological investigations. Arguments based on political sensitivities or apparent access to other funding sources are inappropriate. In this white paper, we argue for a level playing field.

January 11, 2018

PicSat: Eye on Beta Pictoris

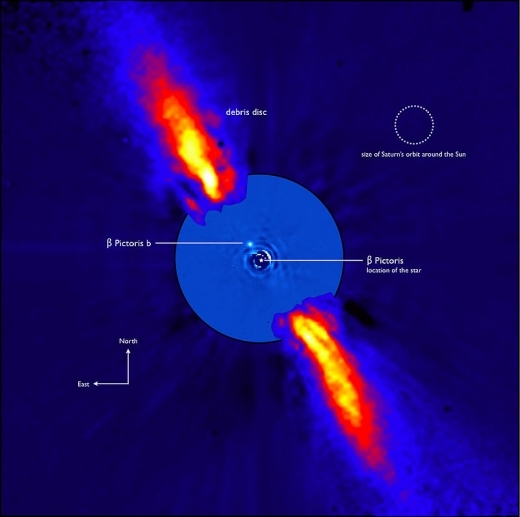

To understand why Beta Pictoris is receiving so much attention among astronomers, particularly those specializing in exoplanets, you have only to consider a few parameters. This is a young star, perhaps 25 million years old, one with a well observed circumstellar disk, the first actually imaged around another star. We not only have a large gas giant in orbit here, but also evidence of cometary activity as seen in spectral data. β Pic is also relatively nearby at 64 light years.

Image: This composite image represents the close environment of Beta Pictoris as seen in near infrared light. This very faint environment is revealed after a careful subtraction of the much brighter stellar halo. The outer part of the image shows the reflected light on the dust disc, as observed in 1996 with the ADONIS instrument on ESO’s 3.6 m telescope; the inner part is the innermost part of the system, as seen at 3.6 microns with NACO on the Very Large Telescope. The newly detected source is more than 1000 times fainter than Beta Pictoris and aligned with the disc. Both parts of the image were obtained on ESO telescopes equipped with adaptive optics. Credit: ESO/A.-M. Lagrange et al.

Consider this star, then, a conveniently close laboratory for the study of how stellar systems form. β Pic b, about seven times as massive as Jupiter, was discovered in 2009 by a French team led by Anne-Marie Lagrange (CNRS/Université Grenoble Alpes). The planet orbits at 1.5 billion kilometers, roughly the distance of Saturn from our Sun, but there is also the possibility of other planets now in formation within the debris disk. Indeed, the observed structure of planetesimal belts here is a possible indication of smaller planets we have not yet observed.

While β Pic b was discovered by direct imaging, there are interesting transit possibilities that are now being explored by scientists at the Paris Observatory and the Centre National De La Recherche Scientifique (CNRS). With launch scheduled for tomorrow, PicSat is a nanosatellite built on a CubeSat platform, one containing a 5 cm telescope destined for the study of β Pic. PicSat will use no more than 5 watts of power in the attempt to view a transit of β Pic b.

Image: An artist’s impression of PicSat in orbit around the Earth. Credit and copyright: T. Pesquet ESA / NASA – LESIA / Observatoire de Paris.

We don’t have a firm idea of exactly when the transit will occur, but scientists with the project peg any time between now and the summer of this year. A transit here would last only a few hours, but it would give us information about the size of the planet, the extent of its atmosphere and its chemical composition. The beginning of a transit will trigger an alert to the 3.6 meter telescope at the European Southern Observatory’s La Silla site, where the HARPS (High Accuracy Radial velocity Planet Searcher) spectrograph can be used to study the event.

Keeping a continuous eye on β Pic to spot the beginning of the transit is thus an imperative. Transits are expected to occur only every 18 years, and indeed PicSat was designed and constructed in just three short years. Modular methodologies to the rescue as we are reminded once again that simple resources like CubeSats are capable of world-class science.

Launch is scheduled for 12 January at 0358 UTC (2258 EST) aboard an Indian PSLV launcher, with the satellite inserted into a polar orbit at an altitude of 505 kilometers, a tandem launch that will include some thirty other satellites. While the satellite will be operated from Meudon in France, a facility of the Paris Observatory, PicSat uses radio amateur bands for communication.

Citizen scientists therefore take note: The PicSat team is opening the door for radio amateurs worldwise to collaborate in tracking the satellite, receiving data and relaying them to the PicSat database over the Internet. Have a look at the PicSat website for information on how to register to become part of this ad hoc radio network and follow PicSat updates. The site has been down this morning, presumably because of last minute updates, but keep checking.

Pssst everyone. It is PicSat, from the inside on top of the #PSLVC40 launcher, whispering, must disturb my co-travellers. It is 9h28m AM here in Sriharikota, 4h58m AM in Paris. That means 24 hours to ignition … & counting 23:59:59, 23:59:58, 23:59:27 …. sooo excited! #CubeSat pic.twitter.com/dnTqJPZ3EY

— PicSat (@IamPicSat) January 11, 2018

Achieving great things with small packages is becoming part of our culture, and we can wish French space agency CNES and PicSat a safe launch as it begins its one year mission. The launch will be covered live here and you can keep up with PicSat events at https://twitter.com/IamPicSat, or check out its YouTube channel.

Paul Gilster's Blog

- Paul Gilster's profile

- 7 followers