Lars Iyer's Blog, page 56

June 3, 2013

The last, laconic sentence of the novella merely informs ...

The last, laconic sentence of the novella merely informs us: 'So lebte er hin' ('And so he lived on'). Not happily ever after, as in a fairy-tale, but numbed out, resigned to fate, condemned (like Beckett's characters) simple to endure that 'living on' (or Fortleben) which, according to Walter Benjamin, characterizes the afterlife of originals in translation.

Goethe observes in a letter: 'Lenz is among us like a sick child, and we rock and dandle him and give him whatever toy he wants to play with'. Realizing that his role at Weimar, as he puts it in his play Tantalus, is 'to serve as a farce for the gods', he retires to the rural hamlet of Berka for the summer ...

Buechner's reading of Lenz's innovative Sturm and Drang prose dramas is evident in many of the formal features of his play [...] in the utterly un-Aristotelian distribution of the dramatic action into a series of fragmentary episodes or tableaux whose rapid-fire scene and mood changes acquire an almost stroboscopic or hallucinatory intensity.

No wonder Gutzkow wrote him upon hearing that he had written his masterpiece, Danton's Death, 'in five weeks at most'; 'You seem to be in a great hurry. Where do you want to get to? Is the ground really burning under your feet?' Or as Camille Desmoulins remarks in Danton's Death: 'We have no time to waste'. To which the world-weary Danton retorts, quoting Shakespeare's Richard II: 'But it is time that wastes us'. This state of urgency (or emergency) is the hallmark of Buechner's finest writing. Danton's Death is the fastest moving historical drama in the entire modern repertory and the precipitous paratactic pace of Lenz is unmatched by anything in nineteenth century prose until Rimbaud's Illuminations.

Richard's Sieburth's afterword to his translation of Buechner's Lenz

He raced this way and that. A song of hell triumphant was...

He raced this way and that. A song of hell triumphant was in his breast.

[...] [H]e was now standing at the abyss, driven by an insane desire to peer into it over and over, and to repeat this torture.

At times he walked slowly and complained his limbs had grown very weak, then he would pick up astonishing speed, the landscape was making him anxious, it was so narrow he was afraid he would bump into everything.

... the world he has wanted to benefit from had a gaping rip in it, he had no hate, no love, no hope, a horrible emptiness, and yet a tormented desire to fill it. He had nothing. Whatever he did, he did in full self-awareness, and yet some inner instinct drove him onward. When he was alone he felt so terribly lonely he constantly spoke to himself aloud, called out, grew afraid again, it seemed to him as if the voice of a stranger had spoken to him. [...]

... The incidents during the night reached a horrific pitch. Only with the greatest effort did he fall asleep, having tried at length to fill the horrible void. Then he fell into a dreadful state between sleeping and waking; he bumped into something ghastly, hideous, madness took hold of him, he say up, screaming violently, bathed in sweat, and only gradually found himself again. He had to begin with the simplest things in order to come back to himself. in fact he was not the one doing this but rather a powerful instinct for self-preservation, it was as if he were double, the one half attempting to save the other, calling out to itself; he told stories, he recited poems out loud, wracked with anxiety, until he came to his senses. [...]

.... [I]t was the abyss of irreparable madness, an eternity of madness. [...]

The half-hearted attempts at suicide that he kept on making were not entirely serious, it was less the desire to die, death for him held no promise of peace or hope, than the attempt, at moments of excruciating anxiety or dull apathy bordering on non-existence, to snap back into himself through physical pain. [...]

Can't you hear it, can't you hear that hideous voice screaming across the entire horizon, it's what's usually called silence and ever since I've been in this quiet valley I can't get it out of my ears, it keeps me up at night, oh dear Reverend, if I could only manage to sleep again. [...]

He seemed quite rational, conversed with people; he acted like everybody else, but a terrible emptiness lay within him, he felt no more anxiety, no desire; he saw his existence as a necessary burden. - And so he lived on.

from Georg Buechner, Lenz

May 16, 2013

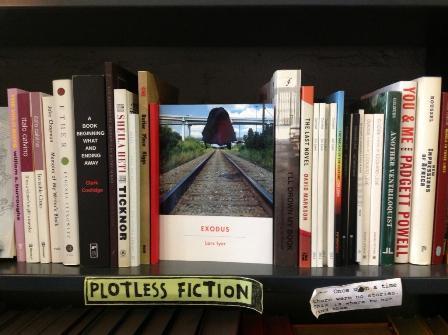

Picture by Janet Joy Wilson.

[With reference to Jabès's The Book of Questions] A host ...

[With reference to Jabès's The Book of Questions] A host of imaginary rabbis. They have names ('names of listening'), but are not individualized, They are not characters. Not even the shadowy kind of character that Yukel is ('you are a shape moving in the fog.... You are the toneless utterance among anecdotal lies'). Most of them do not speak more than once, though a few are allowed to dispute for several pages. Even then they do not really become persons. What they say is not necessarily consistent. They do not represent a position. They are not authorities. Gabriel Bounoure calls them 'candidates for presence, but hesitant to quit their status of shadows'.

Voices, rather. A chorus. Of commentary and interpretation. Of exchange. a chorus that points to the phenomenon of voice as such or, rather, to the phenomenon of changing voice, changing pespective. In a rhythm of voice - absence of voice - voice. This is why, in his later books, the rabbis, privileged interpreters though they are, disappear. They become absorbed into the white space between paragraphs, between aphorisms.

Waldrop, Lavish Absence

Even when his time is his own, later, Edmond Jabès works ...

Even when his time is his own, later, Edmond Jabès works in snatches, in fragments. No matter where, in cafés, in the métro, while walking, at dinner, on little bits of paper, on matchbooks, napkins, in his mind.

Waldrop, Lavish Absence

Three rhythms layer [Jabès's The Book of Questions]. On t...

Three rhythms layer [Jabès's The Book of Questions]. On the micro-level, there is the rhythm of the individual line or sentence. A rhythm that, in te verse, comes out of the tension between sentence and line, and in the prose, out of the tension between speech and the more formal syntax of writing[....]

On the structural level, there is the rhythm of prose and verse and, more importantly, of question and answer, question and further question, question and commentary, commentary on commentary and, later, aphorism after aphorism.

Rhythm of midrash, of the rabbinical tradition. Not a dialectic aiming for synthesis, but an open-ended spiralling. A large rhythm, come out of the desert, a rhythm of sand shifting as if with time itself.

Then, there is a third rhythm. It is on the level of the book: a rhythm of text and blank space, of presence and absence.

Rosmarie Waldrop, Lavish Absence

'How can I know if I write in verse or prose', Reb Elati ...

'How can I know if I write in verse or prose', Reb Elati remarked. 'I am rhythm'.

Jabès, The Book of Questions

The meandering word dies by the pen, the writer by the sa...

The meandering word dies by the pen, the writer by the same weapon turned back against him.

'What murder are you accused of?' Reb Achor asked Zillieh, the writer.

'The murder of God', he replied. 'I will, however, add in my defence that I die along with Him'.

Jabès, The Book of Yukel

A young disciple asks his master, 'If you never give me a...

A young disciple asks his master, 'If you never give me an answer, how shall I know that you are the master and I the disciple?' And the master responds, 'By the order of the questions'.

Jabès, interviewed by Jason Weiss

Even in 'normative' Judaism, the opening of interpretatio...

Even in 'normative' Judaism, the opening of interpretation is extraordinary.... The rabbinical word remains ever open, unfulfilled, in process. Yet there is great risk here; this inner dynamic accounts for both the creativity of Judaism and its own inversions and undoing. Where is the line between interpretation and subversion? I have elsewhere called this a 'heretic hermeneutic', which is a complex of identification with the text and its displacement. Jabès's book is precisely this identification with the Sacred Book and its displacement. The Book is now opened to include even its own inversions.

Susan Handelman, The Sin of the Book

Lars Iyer's Blog

- Lars Iyer's profile

- 99 followers