Sheenagh Pugh's Blog, page 32

October 8, 2014

Thinking about Norway

Most Norwegian towns and cities are very tidy, and though that is also true in the English sense, I mean it mostly in the Welsh sense, ie respectable, well to do and with an indefinable sense of everything being right. Bergen, it's true, has a slightly raffish air, like the younger son of a prosperous family who's decided to play at bohemians for a few years before settling down to practise law. (Oslo, from my admittedly limited experience of it, is more like the daughter who went to the Sorbonne and came back thinking herself several cuts above all her relatives). Bergen is less sophisticated and more fun. If you're there in summer, don't miss visiting the former leper hospital, which is one hell of a story.

Going up the coast, Ålesund, like almost all the wooden towns in Norway, was forever burning down; in Ålesund's case it was destroyed in 1904. It was their good luck that Kaiser Bill, of all people, used to go yachting there (it still has a considerable marina and port area) and he put a lot of money into rebuilding it in the art nouveau style. Since there were no more fires of note, it's still very much in one style, and its palette is pastel, rather than the bright primary colours of many Norwegian towns. Ålesund is an older second cousin, pretty and elegant but inclined to hark back to whichever decade saw her heyday.

Trondheim used to burn down a lot too, until after one such conflagration in 1681, the then mayor thought "what a good idea it'd be if all our houses didn't burn down every few years" and hired a Luxemburger called Johan Caspar von Cicignon to make a city plan based on broad streets so that any fires could be contained. The result is that today's centre has a lot of old buildings, wide tree-lined boulevards and no real congestion. And the river Nid, and an austerely lovely cathedral. Trondheim is a beautiful maiden aunt of indeterminate age and independent means, with impeccable taste and manners but a very relaxed outlook on life. As may be obvious, I'm rather besotted by it.

Next up, just inside the Arctic Circle, comes Bodø, tidy, with an aviation museum and, at least to a visitor's eye, very dull. But its inhabitants love it, even taking pride in its frankly undistinguished architecture, so there must be more to it than meets a tourist's eye. (It does have the original maelstrom nearby). I think of it as the male cousin who's essentially friendly and decent, if a bit of a bore.

Tromsø is the big exception to the "Norwegian towns are tidy" rule, and I can only put this down to the big student population. It has many old buildings and some spectacular new ones, but a lot of its streets look run-down, the pavements are a danger to life and limb and the whole place has a frontier-town, unfinished air. It's definitely a student son, and not a bookish one either, more the kind who gets out of bed just in time to watch Bargain Hunt and never remembers when it's bin day.

Very unlike Hammerfest, which is further north but definitely tidy. North of Tromsø you are into the tract where the retreating German forces in WW2 carried out a shocking scorched-earth policy as the Red Army approached. Lothar Rendulic, the Austrian Nazi governor of North Norway, burned entire towns to the ground, with winter coming on; Hammerfest folk were reduced to living in caves. There's a Reconstruction Museum that details it all. From the sea, and from above, Hammerfest is a white triangle among greenery, not unlike the fanciful mediaeval descriptions of Algiers as a diamond set among emeralds. Hammerfest is your bachelor uncle who lives in a penthouse, all glass and wood and the sort of minimalist design you pay a fortune for.

In Kirkenes, close to the Russian border, the people took shelter from Rendulic's burnings in the town's mines, from which they were literally brought back to light by the Red Army. There's a lot of Russian influence, with a Russian market every last Thursday of the month, and Russian street signs. The actual border is in a forest that looks like Narnia, and the Pasvik river valley is very pretty, but the town is plain, cheerful, no-nonsense industrial and maritime; they repair ships and are profiting from increased petroleum-drilling activity in the Barents Sea. Kirkenes is your uncle who's always on his travels, and turns up every so often with exotic presents and even more exotic stories which your mother wishes he wouldn't tell in mixed company.

Going up the coast, Ålesund, like almost all the wooden towns in Norway, was forever burning down; in Ålesund's case it was destroyed in 1904. It was their good luck that Kaiser Bill, of all people, used to go yachting there (it still has a considerable marina and port area) and he put a lot of money into rebuilding it in the art nouveau style. Since there were no more fires of note, it's still very much in one style, and its palette is pastel, rather than the bright primary colours of many Norwegian towns. Ålesund is an older second cousin, pretty and elegant but inclined to hark back to whichever decade saw her heyday.

Trondheim used to burn down a lot too, until after one such conflagration in 1681, the then mayor thought "what a good idea it'd be if all our houses didn't burn down every few years" and hired a Luxemburger called Johan Caspar von Cicignon to make a city plan based on broad streets so that any fires could be contained. The result is that today's centre has a lot of old buildings, wide tree-lined boulevards and no real congestion. And the river Nid, and an austerely lovely cathedral. Trondheim is a beautiful maiden aunt of indeterminate age and independent means, with impeccable taste and manners but a very relaxed outlook on life. As may be obvious, I'm rather besotted by it.

Next up, just inside the Arctic Circle, comes Bodø, tidy, with an aviation museum and, at least to a visitor's eye, very dull. But its inhabitants love it, even taking pride in its frankly undistinguished architecture, so there must be more to it than meets a tourist's eye. (It does have the original maelstrom nearby). I think of it as the male cousin who's essentially friendly and decent, if a bit of a bore.

Tromsø is the big exception to the "Norwegian towns are tidy" rule, and I can only put this down to the big student population. It has many old buildings and some spectacular new ones, but a lot of its streets look run-down, the pavements are a danger to life and limb and the whole place has a frontier-town, unfinished air. It's definitely a student son, and not a bookish one either, more the kind who gets out of bed just in time to watch Bargain Hunt and never remembers when it's bin day.

Very unlike Hammerfest, which is further north but definitely tidy. North of Tromsø you are into the tract where the retreating German forces in WW2 carried out a shocking scorched-earth policy as the Red Army approached. Lothar Rendulic, the Austrian Nazi governor of North Norway, burned entire towns to the ground, with winter coming on; Hammerfest folk were reduced to living in caves. There's a Reconstruction Museum that details it all. From the sea, and from above, Hammerfest is a white triangle among greenery, not unlike the fanciful mediaeval descriptions of Algiers as a diamond set among emeralds. Hammerfest is your bachelor uncle who lives in a penthouse, all glass and wood and the sort of minimalist design you pay a fortune for.

In Kirkenes, close to the Russian border, the people took shelter from Rendulic's burnings in the town's mines, from which they were literally brought back to light by the Red Army. There's a lot of Russian influence, with a Russian market every last Thursday of the month, and Russian street signs. The actual border is in a forest that looks like Narnia, and the Pasvik river valley is very pretty, but the town is plain, cheerful, no-nonsense industrial and maritime; they repair ships and are profiting from increased petroleum-drilling activity in the Barents Sea. Kirkenes is your uncle who's always on his travels, and turns up every so often with exotic presents and even more exotic stories which your mother wishes he wouldn't tell in mixed company.

Published on October 08, 2014 05:17

September 20, 2014

The poem of six words

In an earlier post, I talked about different things coming together to produce a poem. The poet Bethany W Pope has been discussing sestinas on Facebook lately, and it reminded me of how long I'd wanted to write a sestina before I actually did. Like Bethany, I love the intricacy and playfulness of this form, based around six key words that recur in different places in the verse, ideally not always with the same meaning but using all possible senses, homonyms, even grammatical forms. One issue I had with it, however, was that in a conventional sestina, it's pretty obvious from the start what one is doing; the form is like scaffolding left up on a building and to my eye, dominates the subject matter too much. I didn't see how to get over this one until I read sestinas by people like Paul Muldoon and Paul Henry, who disguised the form by putting line and verse breaks where they aren't expected, so that at first reading it might not strike the reader as a sestina at all.

But I still had a problem with finding what seemed to me to be suitable subject matter, so that the form would seem natural and organic to the poem, rather than the poem seeming to have been invented for the sake of filling out the form. This happened when I read a biography of Sir Francis Walsingham, Elizabeth I's spymaster. He ran many agents, who naturally used aliases, fake IDs, codes and all the other paraphernalia of their trade, and I could see how this could be mirrored both in the six key words with their shifting shapes and meanings, and by disguising the form itself. For the first time ever, I was looking at a theme - secrecy, personation, encoding and code-breaking - that actually seemed to want this abstruse form. Of course, having taken years, three of them then came along at once, like buses, and became a sequence called "Walsingham's Men", which is in my new collection Short Days, Long Shadows , to be had from Messrs Seren and no doubt very few good booksellers... Here's one.

WALSINGHAM'S MEN

3. Decoder

Thomas Phelippes, alias John Morice, alias Peter Halins, 1598

When, in the street, he catches foreign words

- Spanish, Italian, French – he can sense

his thought shifting, see the world remade,

but if the language be one he does not know,

he follows, caught, longing for sounds to resolve

into a pattern, to begin to mean

something.

This maggot has been the means

of his advance; it is not only words

he has a feel for. He can make sense

of symbols, letters, language unmade

by cipher, a crafted chaos he knows

for a world, for plans that dissolve

in the code's chrysalis, and will resolve

again to damn their authors. All means

of ciphering can be unlocked: the words

run together, the strings of nonsense

that mask how sentences are made,

the nulls, the substitutes.

He seeks to know

what the enemy knows, what they think he knows,

to read their mind's language, to solve

their uncertainties, decode what they mean

to do. When sometimes they put into words

less than he knows they think, he turns the sense

to speak the truth. Their letters remade,

he sends them on their way, having first made

copies for all who need to know.

Some trust to alum ink, that dissolves

and fades on the page; he reads it by means

of fire. Their cipher keys, their passwords

open to him. People see him, and sense

no danger: so small and thin, in no sense

memorable, a null.

His fortune's made,

yet, for all the languages he knows,

figures are the code he can't solve,

the closed book. His debts many, his living mean,

he will get out of jail only with words,

demeaning himself to men who see sense

in his accounts, that wordless hash, who know

how to solve his life, the mess he's made.

But I still had a problem with finding what seemed to me to be suitable subject matter, so that the form would seem natural and organic to the poem, rather than the poem seeming to have been invented for the sake of filling out the form. This happened when I read a biography of Sir Francis Walsingham, Elizabeth I's spymaster. He ran many agents, who naturally used aliases, fake IDs, codes and all the other paraphernalia of their trade, and I could see how this could be mirrored both in the six key words with their shifting shapes and meanings, and by disguising the form itself. For the first time ever, I was looking at a theme - secrecy, personation, encoding and code-breaking - that actually seemed to want this abstruse form. Of course, having taken years, three of them then came along at once, like buses, and became a sequence called "Walsingham's Men", which is in my new collection Short Days, Long Shadows , to be had from Messrs Seren and no doubt very few good booksellers... Here's one.

WALSINGHAM'S MEN

3. Decoder

Thomas Phelippes, alias John Morice, alias Peter Halins, 1598

When, in the street, he catches foreign words

- Spanish, Italian, French – he can sense

his thought shifting, see the world remade,

but if the language be one he does not know,

he follows, caught, longing for sounds to resolve

into a pattern, to begin to mean

something.

This maggot has been the means

of his advance; it is not only words

he has a feel for. He can make sense

of symbols, letters, language unmade

by cipher, a crafted chaos he knows

for a world, for plans that dissolve

in the code's chrysalis, and will resolve

again to damn their authors. All means

of ciphering can be unlocked: the words

run together, the strings of nonsense

that mask how sentences are made,

the nulls, the substitutes.

He seeks to know

what the enemy knows, what they think he knows,

to read their mind's language, to solve

their uncertainties, decode what they mean

to do. When sometimes they put into words

less than he knows they think, he turns the sense

to speak the truth. Their letters remade,

he sends them on their way, having first made

copies for all who need to know.

Some trust to alum ink, that dissolves

and fades on the page; he reads it by means

of fire. Their cipher keys, their passwords

open to him. People see him, and sense

no danger: so small and thin, in no sense

memorable, a null.

His fortune's made,

yet, for all the languages he knows,

figures are the code he can't solve,

the closed book. His debts many, his living mean,

he will get out of jail only with words,

demeaning himself to men who see sense

in his accounts, that wordless hash, who know

how to solve his life, the mess he's made.

Published on September 20, 2014 06:36

September 18, 2014

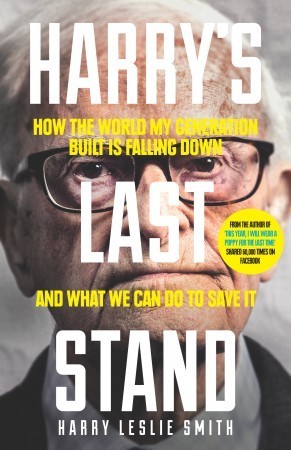

"I am history"… review of Harry's Last Stand by Harry Leslie Smith, pub. Icon Books

"I am not an historian, but at 91 I am history and I fear its repetition"

Harry Leslie Smith's father was a miner in the early years of the last century, like my own grandfather, and the only difference between them was that, as Smith observes, a miner in those days was only ever one accident away from destitution. My grandfather was relatively lucky, surviving to his sixties with an impressive collection of lung diseases: Smith's had the accident that plunged the family into real poverty.

It isn't often I go in for saying "if you liked this, you'll like that", but in this case it is a fair guide: if you found Ken Loach's film "Spirit of 45" both moving and alarming, you will want to read this book. Harry Leslie Smith is another from the same stable as Sam Watts and Ray Davies, interviewed in that film. Born in 1923, he grew up in the Depression years in such poverty that joining the army to fight in World War 2 felt more like an escape than anything else. He then emerged, with so many other young working-class people, into the sunlit uplands of a country that for the first time in its history was actually trying to bring about decent housing, education and a health service for people like him. And naturally he thought it was going to last, so that his own children and grandchildren would never be in danger of repeating the life of his mother, worn down by poverty and so suspicious of authority that she saved as much as she could of her pension in case the government might suddenly change its mind and want it back. Or of his father, whose marriage broke up when he became unable to support his family, or his sister Marion, who died of TB in childhood.

Now in his nineties, seeing the wreck of all he once saw built up, he is naturally puzzled and annoyed: "Sometimes I try and think how I might explain to Marion how we built these beautiful structures in our society – which protected the poor, which kept them safe at work, healthy in their lives, supported them when they were down on their luck - only to watch them be destroyed within a few short generations. But I cannot find the words".

That, though, is just what he did do, by setting down the story he sees the world in danger of forgetting: the narrative of the slum housing in which he grew up, where no amount of cleaning could eradicate damp and vermin, of disease which could not be cured because doctor's fees could not be afforded, of education unavailable to children whose families could not spare the wages they might bring in. (Harry's own education, like so much else, really began in 1945 when he went to adult education classes.) As one of his chapter headings says, "everything old is new again" and he is concerned in this book to warn "we have to take back control, or soon we won't have a social welfare system, we won't have free or affordable health care, we won't have safe neighbourhoods and we won't have decent school. We will have the world of my youth, where people died from poverty and preventable illnesses and lived short, unfulfilled lives".

How this control might be returned is a tricky question, because one thing that has changed about the world is the amount of power in the hands of multinational corporations with no aims or obligations outside the making of money. Harry Leslie Smith is an unusual man, who sees beyond boundaries that restrict the vision of others, as he showed when, in post-war Germany, he overcame his hostility to his former enemies to the extent of marrying a German woman. He has no time for the demonisation of minorities, the fragmenting of those who have a common cause if they could only see it, nor for the fashionable apathy that says "what's the point of voting?". He does have some practical suggestions for making our world better, like going after corporate tax evaders and amending the voting system. But mostly, as I think he himself suspects, it is a matter of spirit, the spirit in which he and his generation not only "voted for the future" in 1945 but were prepared also to work and pay tax for it. It's a question of whether that spirit still exists: when he says "I am history", we must hope this is only true in the sense that he and his kind lived through it, and not in the modern slang sense of the phrase.

Published on September 18, 2014 04:32

September 12, 2014

Dept of Hollow Laughter

An article in yesterday's Grauniad quoted the Poem We Don't Mention and linked to a page at the Wondering Minstrels site that had printed it. Foolishly I followed to see if they'd at least printed it without any typos, and was soon helpless with mirth. The site had recorded my known views on the poem, so of course there were the usual hurt remarks below, saying for instance "you must try to like it" (no, actually I "must" do nothin' - to quote Barbossa). I'm sure the word "ungrateful" cropped up too; it usually does, to my complete bafflement.

But the laugh-out-loud bits - two priceless quotes:

1. "the fact that you sold it to (sic) a English GCSE exam board" Ha! Dear punter, GCSE exam boards in the UK are exempt from copyright. They can and do take and use anyone's work without paying, asking or even having the courtesy to inform them. Sell them anything? I'd like to see you try!

2. "I bet you still take the buckets of royalties that Sometimes brings in!" Oh, pick me up from the floor, someone! Now, Mr Know-all, please listen carefully. Most people who reprint poems don't bother to ask, and certainly don't offer money. That includes national newspapers; the Telegraph once reprinted this one, without my knowledge. Those that do ask are almost always representing charitable anthologies and don't have money to offer either, not that I wouldn't give them poems free for a charity I approve of; I'd just rather it wasn't this poem). As it happens, I do not accept money for this one because on the rare occasions I let some charity use it, I insist they leave my name off. But I'm not exactly losing much, because those anthologies etc that do offer money for reprints, which in my case happens maybe twice a year, will be offering about £20 if you're lucky. Yeah, rolling in it, us poets are.

But the laugh-out-loud bits - two priceless quotes:

1. "the fact that you sold it to (sic) a English GCSE exam board" Ha! Dear punter, GCSE exam boards in the UK are exempt from copyright. They can and do take and use anyone's work without paying, asking or even having the courtesy to inform them. Sell them anything? I'd like to see you try!

2. "I bet you still take the buckets of royalties that Sometimes brings in!" Oh, pick me up from the floor, someone! Now, Mr Know-all, please listen carefully. Most people who reprint poems don't bother to ask, and certainly don't offer money. That includes national newspapers; the Telegraph once reprinted this one, without my knowledge. Those that do ask are almost always representing charitable anthologies and don't have money to offer either, not that I wouldn't give them poems free for a charity I approve of; I'd just rather it wasn't this poem). As it happens, I do not accept money for this one because on the rare occasions I let some charity use it, I insist they leave my name off. But I'm not exactly losing much, because those anthologies etc that do offer money for reprints, which in my case happens maybe twice a year, will be offering about £20 if you're lucky. Yeah, rolling in it, us poets are.

Published on September 12, 2014 08:45

help!

Is there a way of disabling LJ messages? I've gone through the FAQ but can't find it. I hardly ever remember to check them and it'd be much better (and less embarrassing) if folks couldn't contact me that way.

ED: dunnit, thanks to Espresso Addict!

ED: dunnit, thanks to Espresso Addict!

Published on September 12, 2014 01:28

September 11, 2014

The solitary stars

In a recent Facebook post, I mentioned that I'd written a couple of poems after a long fallow period, or more accurately, a long period when I had written, but not thought anything worth keeping. In the comments, someone asked a question, not the old chestnut "where do you get your ideas from", but the far more interesting question of why some of these ideas end up as poems while others prove intractable, and what the process is that sends them one way or t'other.

To start with the two I wrote this week, which came from two very different places and followed different routes to completion. The first derived from a thought I had about my neighbour's trees, and an image I could pretty immediately see them providing. This, for me, is a good place to start, because poems that start from things or images, for me, are a lot more likely to get written than ones that start because I feel like writing a poem on a certain theme. The latter usually end up more like lectures, or at least prose. The core image then meshed with a couple of other things currently going on in my mind and the neighbourhood, all of which I could see were tending the same way. I wrote the poem quite quickly, over a couple of days.

The second was quite different. It derived from something I'd read in a history book about a year or more ago and been, at the time, much moved by. I'd had a perfunctory go at writing about it at the time and got nowhere. I was reminded of it because an email arrived with some proofs to check, of an interview I'd done for a book. In this interview I'd mentioned that I was working on this idea, and when I read the proofs, I thought perhaps I'd better go back and do something about it.

I was into half-rhymed terza rima at the time, and started out trying to work the idea into this form. It fell into it easily enough, but it wasn't exciting me and I could see the thing going the way of so many poems I'd started and abandoned as not being keepers. But I was sure this one had something going for it as an idea, so I persisted, but abandoned the terza rima. The breakthrough was an idle reflection that if Cavafy had happened to know of this particular event, he'd surely have written about it. Light went on in head: okay, thinks I, we'll channel him and see if we can figure out how he'd have handled it. Which I did, and ended up with something I liked. It isn't, I hope, imitation Cavafy; apart from anything else, it doesn't rhyme, which most of his did, but there's definitely an influence there, especially in the way the incident gets seen through the eyes of a character in the poem, which I hadn't been doing when I first read about it. Perhaps because of this, the poem didn't turn out to say quite what I thought it was going to when I began. Once I had his viewpoint, the poem took shape quite quickly but it had essentially taken over a year from the first idea.

Now my notebook is still full of other ideas that didn't make it - or haven't made it yet. It's possible some of them need a nudge, like the one my second poem got when I read those proofs. Or a lucky insight, like the one about Cavafy. It is certainly a fact that the older I get, the less easily satisfied I am with my work and the more I reject. It isn't enough for there to be nothing obviously wrong about the poem - there needs to be something not only right but necessary about it. This may partly be down to my being aware of so many more poems now, of knowing how many poets have handled this or that material and thinking well, there'd better be something different about yours, or there's no point in writing it down. I think I have also become more exacting in the same way about reading. I have read a lot of poetry collections and thought "it's all right, good even, but it isn't essential; I wouldn't grieve unduly if I could never read a collection by that poet again". With the poets I love - Louis MacNeice, Edwin Morgan, Sorley MacLean, Paul Henry, Louise Glück - I do feel they're essential; if one of the ones still living brings out a new book, I know I'll have to buy it.

I don't know if this business of heightened expectations happens to other poets as they age, meaning they complete, and keep, fewer poems the older they get. I think it's true for me. Also that being intrinsically idle, the odd nudge can help. But mainly I think it is things coming together - an image links with an incident, or a phrase wanders into the mind and changes the rhythm of how you were going to clothe an idea. Maybe some writers work like sculptors and chisel a poem out of a single block of marble, as it were. I think I'm more like a jackdaw who has to assemble it from various materials collected in different places and sometimes over a very long time.

Oh, the title of this post - from a poem of Housman's in which he uses the image of gardening for his own creative process:

And some the birds devour,

And some the season mars,

But here and there will flower

The solitary stars.

To start with the two I wrote this week, which came from two very different places and followed different routes to completion. The first derived from a thought I had about my neighbour's trees, and an image I could pretty immediately see them providing. This, for me, is a good place to start, because poems that start from things or images, for me, are a lot more likely to get written than ones that start because I feel like writing a poem on a certain theme. The latter usually end up more like lectures, or at least prose. The core image then meshed with a couple of other things currently going on in my mind and the neighbourhood, all of which I could see were tending the same way. I wrote the poem quite quickly, over a couple of days.

The second was quite different. It derived from something I'd read in a history book about a year or more ago and been, at the time, much moved by. I'd had a perfunctory go at writing about it at the time and got nowhere. I was reminded of it because an email arrived with some proofs to check, of an interview I'd done for a book. In this interview I'd mentioned that I was working on this idea, and when I read the proofs, I thought perhaps I'd better go back and do something about it.

I was into half-rhymed terza rima at the time, and started out trying to work the idea into this form. It fell into it easily enough, but it wasn't exciting me and I could see the thing going the way of so many poems I'd started and abandoned as not being keepers. But I was sure this one had something going for it as an idea, so I persisted, but abandoned the terza rima. The breakthrough was an idle reflection that if Cavafy had happened to know of this particular event, he'd surely have written about it. Light went on in head: okay, thinks I, we'll channel him and see if we can figure out how he'd have handled it. Which I did, and ended up with something I liked. It isn't, I hope, imitation Cavafy; apart from anything else, it doesn't rhyme, which most of his did, but there's definitely an influence there, especially in the way the incident gets seen through the eyes of a character in the poem, which I hadn't been doing when I first read about it. Perhaps because of this, the poem didn't turn out to say quite what I thought it was going to when I began. Once I had his viewpoint, the poem took shape quite quickly but it had essentially taken over a year from the first idea.

Now my notebook is still full of other ideas that didn't make it - or haven't made it yet. It's possible some of them need a nudge, like the one my second poem got when I read those proofs. Or a lucky insight, like the one about Cavafy. It is certainly a fact that the older I get, the less easily satisfied I am with my work and the more I reject. It isn't enough for there to be nothing obviously wrong about the poem - there needs to be something not only right but necessary about it. This may partly be down to my being aware of so many more poems now, of knowing how many poets have handled this or that material and thinking well, there'd better be something different about yours, or there's no point in writing it down. I think I have also become more exacting in the same way about reading. I have read a lot of poetry collections and thought "it's all right, good even, but it isn't essential; I wouldn't grieve unduly if I could never read a collection by that poet again". With the poets I love - Louis MacNeice, Edwin Morgan, Sorley MacLean, Paul Henry, Louise Glück - I do feel they're essential; if one of the ones still living brings out a new book, I know I'll have to buy it.

I don't know if this business of heightened expectations happens to other poets as they age, meaning they complete, and keep, fewer poems the older they get. I think it's true for me. Also that being intrinsically idle, the odd nudge can help. But mainly I think it is things coming together - an image links with an incident, or a phrase wanders into the mind and changes the rhythm of how you were going to clothe an idea. Maybe some writers work like sculptors and chisel a poem out of a single block of marble, as it were. I think I'm more like a jackdaw who has to assemble it from various materials collected in different places and sometimes over a very long time.

Oh, the title of this post - from a poem of Housman's in which he uses the image of gardening for his own creative process:

And some the birds devour,

And some the season mars,

But here and there will flower

The solitary stars.

Published on September 11, 2014 04:20

August 15, 2014

Agent 160 and the Fun Palace

Agent 160 is a writer-led theatre company that produces work from its female playwrights, based across the UK. (In 2010, Sphinx Theatre Company hosted a conference where it was revealed just 17 per cent of produced work in the UK is written by women. It seemed like a good idea to do something about that.) I have a huge interest in their work, naturally, because one of their playwrights is my daughter Sam Burns.

Right now, they are involved in a project to create a Fun Palace, a concept first mooted by Joan Littlewood. In 1961 Littlewood had a vision, of a Fun Palace that would be a temporary, moveable “laboratory of fun” that would welcome everyone. It never happened. But now, her vision is being brought to life for the 21st century. On 4th-5th October 2014, hundreds of pop-up local Fun Palaces will appear across the country, open to everybody, and free.

Agent 160 is working with the Wales Millennium Centre to make one in Cardiff this October; the idea is for lots of short plays to be performed and for the audience to join in a massive, group-written play, and see it performed. However, as is so often the case, they need a bit more money and are raising it via a Kickstarter. It's already got to well within £1000 of its target, but momentum is all in these things, so here I am promoting it. It's here, and well worth supporting especially if you live close enough to go down and have a look at some of the brilliant young women writers' work. Here's the list of playwrights:

Sandra Bendelow

Sam Burns

Vittoria Cafolla

Poppy Corbett

Branwen Davies

Abigail Docherty

Clare Duffy

Samantha Ellis

Sarah Grochala

Katie McCullough

Sharon Morgan

Kaite O'Reilly

Lisa Parry

Marged Parry

Lindsay Rodden

Shannon Yee

Right now, they are involved in a project to create a Fun Palace, a concept first mooted by Joan Littlewood. In 1961 Littlewood had a vision, of a Fun Palace that would be a temporary, moveable “laboratory of fun” that would welcome everyone. It never happened. But now, her vision is being brought to life for the 21st century. On 4th-5th October 2014, hundreds of pop-up local Fun Palaces will appear across the country, open to everybody, and free.

Agent 160 is working with the Wales Millennium Centre to make one in Cardiff this October; the idea is for lots of short plays to be performed and for the audience to join in a massive, group-written play, and see it performed. However, as is so often the case, they need a bit more money and are raising it via a Kickstarter. It's already got to well within £1000 of its target, but momentum is all in these things, so here I am promoting it. It's here, and well worth supporting especially if you live close enough to go down and have a look at some of the brilliant young women writers' work. Here's the list of playwrights:

Sandra Bendelow

Sam Burns

Vittoria Cafolla

Poppy Corbett

Branwen Davies

Abigail Docherty

Clare Duffy

Samantha Ellis

Sarah Grochala

Katie McCullough

Sharon Morgan

Kaite O'Reilly

Lisa Parry

Marged Parry

Lindsay Rodden

Shannon Yee

Published on August 15, 2014 03:39

July 12, 2014

Oh, what a surprise...

I'm the Saturday Poem in the Guardian! One from the new book, Short Days, Long Shadows. Nobody told me that was happening, just came across it while faffing about on the net doing serious research. Of course it's one about being terrified of mortality; I don't really do much else...

Extremophile

Extremophile

Published on July 12, 2014 10:37

July 9, 2014

Virtual house move

Confusingly, I now have two websites. This came about because webs.com, which had been very easy to edit, got "improved", and of course you can guess with what result. It became very hard to edit, so I set up a new site at http://sheenagh.wix.com/sheenaghpugh.

I moved all the poetry-related stuff across, including the pages of resources for exam students. When it came to the stuff relating to novels and fan fiction articles though, I wondered if that was necessary. I don't really write either any more, so the pages at the old site were not going to need editing, which was the problem. Plus I don't trust any site builder not to go offline or just "upgrade" and make itself unusable. So I decided to keep the old site at http://sheenagh.webs.com/ as an archive site for the translations and prose-related stuff, and just in case I ever needed it again....

It's weird, because last time I moved house in real life, we kept the old house up for some years, because there was a very old cat living there who couldn't be moved...

I moved all the poetry-related stuff across, including the pages of resources for exam students. When it came to the stuff relating to novels and fan fiction articles though, I wondered if that was necessary. I don't really write either any more, so the pages at the old site were not going to need editing, which was the problem. Plus I don't trust any site builder not to go offline or just "upgrade" and make itself unusable. So I decided to keep the old site at http://sheenagh.webs.com/ as an archive site for the translations and prose-related stuff, and just in case I ever needed it again....

It's weird, because last time I moved house in real life, we kept the old house up for some years, because there was a very old cat living there who couldn't be moved...

Published on July 09, 2014 11:37

June 29, 2014

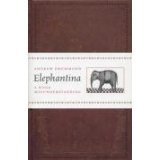

The elephant in the room: Review of Elephantina by Andrew Drummond (Polygon 2008)

Dr Blair's cook is outraged by the storage of parts of dead elephant in her kitchen, while his assistant Gilbert Orum, who is to make sketches and engravings of the beast, finds his mind turning to mortality:

Never mind, Miss Gloag!" shouted the doctor […] "Just think that your splendid kitchen has this evening played a part in the History of Philosophical Experiment!"

Miss Gloag expressed her ardent desire that Philosophical Experiment would rot slowly from its **** upwards, die painfully and be ****** by Satan forever. […]

All I can think of is Death: the age of an Elephant; the age of Man; the age of Woman. Three-score and ten is considered the usual allotted span of our years. But it seems to me that the age of Man is either grossly exaggerated or that it has diminished considerably since the days of the Patriarchs, for the common age of death among the people of Dundee is perhaps thirty or forty, by which time the trials and burdens of the world have taken their toll; a fresh-faced young woman of eighteen may turn, in a matter of three years of marriage, to a woman of middle years, haggard, bitter, bowed, lined, grey; a man of thirty will pass, within a twelve-month, to a white-haired cripple if he suffers one of many possible accidents in his labour

Florentia the elephant died at Dundee in 1706, and remained there in a stuffed condition, having been dissected by Dr Patrick Blair. It will be noted that another death was imminent, that of independent Scotland, for the Act of Union would be signed the following year and the negotiations leading up to it were going on while Dr Blair (an anti-unionist, who would later join the uprising of 1715) was busy on his elephant; indeed Blair explicitly compares his own dissections to those of the Commissioners "cutting and butchering the Body Politick of Scotland".

Of the real Gilbert Orum, engraver, not much is known, but here his imagined journal forms the basis of the novel. It is rediscovered in 1828 by a man using the pseudonym "Senex" and published, with Senex's footnotes, in tribute to Dr Blair. Senex, however, is both an ardent pro-unionist, which means he has constantly to blind himself to the views of his hero Blair, and a prig who disapproves vehemently of the caustic, independent-minded Orum without ever understanding him. His indignant footnotes to Orum's MS provide a rich comic seam running through the novel.

Orum is, in fact, a thoughtful, fallible, likeable narrator who comes to have his own agenda with regard to the elephant. Blair, dissecting and reassembling the skeleton, sees it purely in a scientific light, but Orum has a sense of it as a living creature – indeed he ends up being visited by its spirit – and wants, through his engravings, "to ensure that the world knew what the Elephant had looked like, how it moved, how it lived". Meanwhile though, he also has his family's pressing financial problems to consider, and frequently staves them off by selling various bits of elephant to interested parties.

What is the elephant? We should never forget that she was real; she lived, and died alone and in exile (as will Orum's descendant who inherits the journal and hands it on before departing for Canada, only to die almost as soon as he gets there). But what does she connote, apart from herself? Scotland? Knowledge? A cause; something to live for? All are possible; the novel's sub-title, "A Huge Misunderstanding", rather suggests that no one sees everything about her, like the six blind men in the Hindu proverb who feel different parts of the beast and come to six different conclusions about its appearance.

A final irony: this book about a huge beast is easily his shortest and sparest so far. But that doesn't mean there's any lack of the usual wit, fascinating detail and thought-provoking strangeness that characterises his writing. I've read my way through all his four novels now, more's the pity, and cannot wait for number 5.

Published on June 29, 2014 07:10