Dermott Hayes's Blog: Postcard from a Pigeon, page 52

August 22, 2016

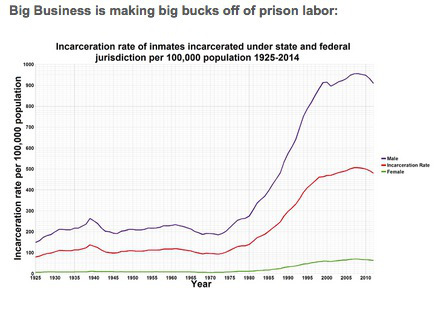

Slavery’s alive and well, doing time and making profits

How Prison Labor is the New American Slavery and Most of Us Unknowingly Support it

June 13, 2016 at 11:58 pm

If you buy products or services from any of the 50 companies listed below (and you likely do), you are supporting modern American slavery

American slavery was technically abolished in 1865, but a loophole in the 13th Amendment has allowed it to continue “as a punishment for crimes” well into the 21st century. Not surprisingly, corporations have lobbied for a broader and broader definition of “crime” in the last 150 years. As a result, there are more (mostly dark-skinned) people performing mandatory, essentially unpaid, hard labor in America today than there were in 1830.

With 5 percent of the world’s population and 25 percent of the world’s prison population, the United States has the largest incarcerated population in the world. No other society in history has imprisoned more of its own citizens. There are half a million more prisoners in the U.S. than in China, which has five times our population. Approximately 1 in 100 adults in America were incarcerated in 2014. Out of an adult population of 245 million that year, there were 2.4 million people in prison, jail or some form of detention center.

The vast majority – 86 percent – of prisoners have been locked up for non-violent, victimless crimes, many of them drug-related.

While prison labor helps produce goods and services for almost every big business in America, here are a few examples from an that highlights the epidemic:

Whole Foods – You ever wonder how Whole Foods can afford to keep their prices so low (sarcasm)? Whole Foods’ coffee, chocolate and bananas might be “fair trade,” but the corporation has been offsetting the “high wages” paid to third-world producers with not-so-fair-wages here in America.

The corporation, famous for it’s animal welfare rating system, apparently was not as concerned about the welfare of the human “animals” working for them in Colorado prisons until April of this year.

You know that $12-a-pound tilapia you thought you were buying from “sustainable, American family farms?” It was raised by prisoners in Colorado, who were paid as little as 74 cents a day. And that fancy goat cheese? The goats were raised and milked by prisoners too.

McDonald’s – The world’s most successful fast food franchise purchases a plethora of goods manufactured in prisons, including plastic cutlery, containers, and uniforms. The inmates who sew McDonald’s uniforms make even less money by the hour than the people who wear them.

Wal-Mart – Although their company policy clearly states that “forced or prison labor will not be tolerated by Wal-Mart,” basically every item in their store has been supplied by third-party prison labor factories. Wal-Mart purchases its produce from prison farms, where laborers are often subjected to long hours in the blazing heat without adequate food or water.

Victoria’s Secret – Female inmates in South Carolina sew undergarments and casual-wear for the pricey lingerie company. In the late 1990’s, two prisoners were placed in solitary confinement for telling journalists that they were hired to replace “Made in Honduras” garment tags with “Made in USA” tags.

AT&T – In 1993, the massive phone company laid off thousands of telephone operators—all union members—in order to increase their profits. Even though AT&T’s company policy regarding prison labor reads eerily like Wal-Mart’s, they have consistently used inmates to work in their call centers since ’93, barely paying them $2 a day.

BP (British Petroleum) – When BP spilled 4.2 million barrels of oil into the Gulf coast, the company sent a workforce of almost exclusively African-American inmates to clean up the toxic spill while community members, many of whom were out-of-work fisherman, struggled to make ends meet. BP’s decision to use prisoners instead of hiring displaced workers outraged the Gulf community, but the oil company did nothing to reconcile the situation.

The full list of companies implicated in exploiting prison labor includes:

Bank of America

Bayer

Cargill

Caterpillar

Chevron

Chrysler

Costco

John Deere

Eli Lilly and Company

Exxon Mobil

GlaxoSmithKline

Johnson and Johnson

K-Mart

Koch Industries

McDonald’s

Merck

Microsoft

Motorola

Nintendo

Pfizer

Procter & Gamble

Pepsi

ConAgra Foods

Shell

Starbucks

UPS

Verizon

WalMart

Wendy’s

While not all prisoners are “forced” to work, most “opt” to because life would be even more miserable if they didn’t, as they have to purchase pretty much everything above the barest necessities (and sometimes those too) with their hard-earned pennies. Some of them have legal fines to pay off and families to support on the outside. Often they come out more indebted than when they went in.

“Prison farms” aka “modern plantations”

In places like Texas, however, prison work is mandatory and unpaid – the literal definition of slave labor.

According the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, prisoners start their day with a 3:30 a.m. wake-up call and are served breakfast at 4:30 a.m. All prisoners who are physically able are required to report to their work assignments by 6 a.m.

“Offenders are not paid for their work, but they can earn privileges as a result of good work habits,” the website says.

Most prisoners work in prison support jobs, like cooking, cleaning, laundry, and maintenance, but about 2,500 of them work in the Texas prison system’s own “agribusiness department,” where they factory-farm 10,000 beef cattle, 20,000 pigs and a quarter million egg-laying hens. The prisoners also produce 74 million pounds of livestock feed per year, 300,000 cases of canned vegetables, and enough cotton to clothe themselves (and presumably others). They also work at meat packaging plants, where they process 14 million pounds of beef and 10 million pounds of pork per year.

While one of the department’s stated goals is to reduce operational costs by having prisoners produce their own food, the prison system admittedly earns revenue from “sales of surplus agricultural production.”

Prisoners who refuse to work – again, unpaid – are placed in solitary confinement. When asked if Texas prisons still employ “chain gangs” in the FAQ section, the department responds:

“No, Texas does not use chain gangs. However, offenders working outside the perimeter fence are supervised by armed correctional officers on horseback.”

Similar “prison farms” exist in Arizona, Alabama, Alaska, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Louisiana, Mississippi, Ohio and other states, where prisoners are forced to work in agriculture, logging, quarrying and mining. Wikipedia says while the agricultural goods produced on prison farms is generally used to feed prisoners and other wards of the state (orphanages and asylums) they are also sold for profit.

In addition to being forced to labor directly for the profit of the government, inmates may be “farmed out” to private enterprises, through the practice of convict leasing, to work on private agricultural lands or related industries (fishing, lumbering, etc.). The party purchasing their labor from the government generally does so at a steep discount from the cost of free labor.

SOURCE: http://returntonow.net/2016/06/13/prison-labor-is-the-new-american-slavery/

RELATED: Kids Spend Less Time Outdoors Than Prisoners

Women in Chains

Why Are There So Many Women in Jail?

The number of women in jails has skyrocketed over the past four decades.

By Michelle ChenTwitter

Inmates in a women’s jail in Los Angeles County, where a program focuses on rehabilitating women who have pled guilty to non-violent crimes. (Reuters / Lucy Nicholson)

There are 14 times more women in jail in this country today than there were in the 1970s. That’s not a typo.

The political sphere is brimming with talk of liberal reform these days, often celebrating a policy shift toward ending mass incarceration, toward a more “humane” criminal justice system focused on rehabilitation. Yet despite recent measures aimed at curbing harsh incarceration policies, the number of women in local jails is only growing.

In a detailed new analysis of the experiences of women in jail—the fastest growing correctional population—the Vera Institute of Justice shows that in many ways the rise in the female jail population over recent years parallels the rising male jail population. Both have largely been driven by harsher sentencing policies, crackdowns on drug use, and “Broken Windows” policing policies that disproportionately criminalize black and Latino youth. But women typically become incarcerated after experiencing gender-based trauma throughout their lives. About eight in ten have experienced domestic partner abuse. A large majority have survived sexual violence.

Most women in jail are detained pre-trial; others are serving shorter sentences, which makes it arguably a less severe form of incarceration than prison. (While jails often house people awaiting trial, state and federal prisons primarily hold those already convicted of crimes.) But at the same time, jail is potentially more destabilizing in a woman’s life.

Women are often ensnared at the jagged edge of Broken Windows policing. Aside from drug offenses, other common charges for women include “minor property crimes, such as shoplifting; and simple assault, such as threats or minor attacks like biting, shoving, hitting, or kicking.”

The Vera report notes that generally women “tend to have less extensive criminal histories than their male counterparts,” even though their arrest rates have grown at a faster rate than that of men. Overall, the share of arrests of women versus men jumped from just 11 percent in 1960 to 26 percent in 2014.

Co-author Elizabeth Swavola says via email:

Women have consistently been charged with lower-level, nonviolent offenses. As criminal justice agencies have come to place greater emphasis on those types of offenses, women have become swept up into the system to a greater extent….While the number of women in prison has begun to decrease, the number of women in jails has continued to increase.

With about a third of women in jail having experienced serious mental illness and over half having suffered medical problems, jail is basically the worst place for them to access the services they need, particularly because many have faced specific forms of gender-related trauma and abuse. Swavola adds that since jail stints tend to be just a few months rather than years:

there is more turnover as people cycle in and out, which means more volatility and fewer programs and services, including health care….Jails are run by the county or municipality and therefore tend to have fewer resources than state or federally run prisons.

Many women are jailed for only tangential involvement with a crime. The Vera report notes that “Complicity law…recognizes no difference between ‘major’ or ‘minor’ accomplices…As a result, women and other lower-level participants can face the same sentences as their more significantly involved counterparts, for instance, by simply taking a phone message.”

This means a young mother who was was forced to serve as a mule for her abusive boyfriend’s meth business may ultimately be pressured to plead guilty in order to obtain a shorter sentence, especially if she’s got a child waiting for her at home. A bout in jail could also interfere with or exacerbate a family’s reliance on public benefits, while a criminal record could foreclose legitimate employment opportunities post-jail.

But by then the damage to the family may already be done. Even a few days in jail could trigger a child welfare agency intervention, sweeping a child into foster care and launching a separate legal quagmire in family court. Trapped in the negative feedback loop between the child welfare and criminal justice systems, a woman just released from prison—often facing joblessness, poverty and perhaps ongoing mental health or substance abuse issues—may end up losing her parental rights in family court if she cannot meet the strict requirements for family reunification.

Still, while women appear to have been disproportionately affected by the mass incarceration drive and the War on Drugs, there’s also real potential to intervene with gender-conscious criminal justice reforms, which are now slowly steering the system toward rehabilitation-based approaches rather than punishment.

Some states and cities have already experimented with jail diversion programs, which sentence people to, for example, drug treatment services instead of jail, or route a homeless person arrested on public nuisance charges away from jail and into supportive housing. Similarly, bail reforms and measures to expand access to legal counsel help keep people in their communities pending trial.

Cities and towns have established a network of 3,000 “problem solving courts” to help those charged with low-level offenses avoid jail and instead get sentenced to, for example, case managers or mental health counselors. In Cook County, Illinois, the Department of Women’s Justice Programs targets its furlough program to accommodate mothers by allowing them to “be released with electronic monitoring to receive outpatient services during the day and care for their families in the evening.”

These interventions are far from perfect; diversion programs for prostitution have been criticized as invasive social engineering. Alternative courts still operate on a tiny scale, compared to a mainstream criminal court system that is rife with corruption and racial inequality. And in many cases, those who face charges should never have been arrested in the first place, as their initial encounter with the police was the result of racial profiling or civil rights violations. Still, the women who are disproportionately victimized and silenced by the country’s incarceration obsession also have that much more to gain from the incipient movements to drive the justice system toward rehabilitation, restorative justice and harm reduction instead of punishment.

The evolving movement for decarceration will only be meaningful for women if their voices are heard from behind bars and beyond, as we rethink how to make communities truly secure.

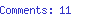

The Oxford Book of English Short Stories

The Short Story as fiction’s ultimate form of fiction.

I’m sitting at the front of the class, with my notes and my presentation, throwing out leading questions on the two short stories we’ve read for our homework. Sounds like school, but this is adult education. We’re in the church hall, on a sunny Autumn morning, by choice.

My paperback copy of The Oxford Book of English Short Stories, edited by Antonia Byatt, is battered, but still holding together. It’s a working copy, with a continually shifting fringe of post-its. The terse notes on them have, here and there, strayed onto the pages. You’ll have gathered that, as an object, this book is no longer a thing of beauty.

My paperback copy of The Oxford Book of English Short Stories, edited by Antonia Byatt, is battered, but still holding together. It’s a working copy, with a continually shifting fringe of post-its. The terse notes on them have, here and there, strayed onto the pages. You’ll have gathered that, as an object, this book is no longer a thing of beauty.

As a source book for a reading group though, this anthology is a joy. The stories provide a taste of how short story ideas changed during the twentieth century, and they’re a challenge.

Half of my class, at least, are not sure about…

View original post 277 more words

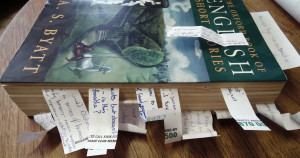

Musical Mood

How to Get Book Reviews

Essential, no-nonsense, waffle free guide to getting reviews. Priceless

Let’s face it, waiting for book reviews can seem to take a lifetime. These all important book reviews are a necessity in getting your book viewed and purchased by more readers. Without them, you’re screwed.

Waiting for Book Reviews?

While your waiting for your book reviews to increase in number you can begin a campaign that will help them do just that.

Ask for reviews: There is absolutely nothing wrong with asking for reviews. In fact, you can send out a newsletter to your subscribers advertising your new book and ask for reviews.

Query book reviewers: You don’t need to pay for this service, although you can. I recommend you get real reviews, because paid ones stand out from the rest, they’re a bit obvious. Start assembling your list of book reviewers well before your publication date. This is something you want to be prepared for so that when your…

View original post 954 more words

50 words

https://dailypost.wordpress.com/prompts/fifty/

So they set me a task. Write a story, they said and I asked, who are you? but they looked at me like they found me on their shoes then they ignored me, snubbed me, wouldn’t tell me why or what to write. I asked, how many words? ‘Fifty’.

Essential Reading for Writers

“I don’t want someone else to destroy me work.” I have heard innumerable writers make some variation of that statement. But often having someone else critique a manuscript is the only way for an author to improve it. After all, he or she has been staring at it for months, grown attached to scenes and […]

via In Defense of Copy Editors: Why Writers Should Use One — Kristen Twardowski

Happy birthday, Philo

Phillip Parris (Philo) Lynott would be 67, if he’d lived. His birthday was celebrated two days ago and I posted a notice on my Facebook page. As a former music journalist, our paths crossed quite often but the first time I came across him was in 1972 when Thin Lizzy, then an unknown Irish rock band, played in our school hall. Myself and a friend were running the soft drinks concession. Several years later, I worked on the security at a show Thin Lizzy headlined in Dublin in 1977, supported by Boomtown Rats, graham Parker and The Rumour and Aswad. This photograph was taken outside the Bailey bar in Dublin, one of Philo’s regular haunts. It was August 1985, a week after his birthday and a little over four months before his tragic death on January 4, 1986.

August 21, 2016

Owning Up

This story is NOT gender exclusive. Switch the he’s and the she’s, the story remains the same.

He takes the blame, comes clean, admits his guilt. It’s a fair cop, he’s caught, he acknowledges, bang to rights, trousers down and red handed, too. He doesn’t have a leg to stand on. ‘What did I do?’ he says, ‘What?’ she asks. He doesn’t want to jeopardize their relationship.

Youth – six word story

Postcard from a Pigeon

- Dermott Hayes's profile

- 4 followers