Dermott Hayes's Blog: Postcard from a Pigeon, page 44

September 13, 2016

Radical

Jameson was not taking ‘no’ for an answer. He would run the race, he assured them. The only problem was for the first time in his life, he was stumped. He couldn’t run and needed to save face. A radical solution occurred to him. He shot himself in the foot.

Cat, Pigeons, which is which?

When We Have to Talk About Kevin author, Lionel Shriver addressed the Brisbane Writers’ Festival last week, she was under no illusion about the importance or potential impact of what she would say. So she came out with all guns blazing. Australian writer, Yasmin Abdel-Magied took exception to her speech and walked out. Her reaction to the speech was published in The Guardian three days ago and here’s a link to the full speech. I must say I don’t think Shriver did herself any justice when she opened her speech quoting an article published online by a site noted for satirical spoof news releases. But that said, the points she makes are valid. read both stories and decide for yourself.

Lionel Shriver’s full speech: ‘I hope the concept of cultural appropriation is a passing fad’

This is the full transcript of the keynote speech, Fiction and Identity Politics, that author Lionel Shriver gave at the Brisbane Writers Festival

‘The ultimate endpoint of keeping our mitts off experience that doesn’t belong to us is that there is no fiction.’ Picture – Lionel Shriver delivers the Brisbane Writers Festival opening address, 8 September, 2016. Photograph: Daniel Seed

Tuesday 13 September 2016

I hate to disappoint you folks, but unless we stretch the topic to breaking point this address will not be about “community and belonging.” In fact, you have to hand it to this festival’s organisers: inviting a renowned iconoclast to speak about “community and belonging” is like expecting a great white shark to balance a beach ball on its nose.

The topic I had submitted instead was “fiction and identity politics,” which may sound on its face equally dreary.

But I’m afraid the bramble of thorny issues that cluster around “identity politics” has got all too interesting, particularly for people pursuing the occupation I share with many gathered in this hall: fiction writing. Taken to their logical conclusion, ideologies recently come into vogue challenge our right to write fiction at all. Meanwhile, the kind of fiction we are “allowed” to write is in danger of becoming so hedged, so circumscribed, so tippy-toe, that we’d indeed be better off not writing the anodyne drivel to begin with.

Let’s start with a tempest-in-a-teacup at Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine. Earlier this year, two students, both members of student government, threw a tequila-themed birthday party for a friend. The hosts provided attendees with miniature sombreros, which—the horror— numerous partygoers wore.

When photos of the party circulated on social media, campus-wide outrage ensued. Administrators sent multiple emails to the “culprits” threatening an investigation into an “act of ethnic stereotyping.” Partygoers were placed on “social probation,” while the two hosts were ejected from their dorm and later impeached. Bowdoin’s student newspaper decried the attendees’ lack of “basic empathy.”

The student government issued a “statement of solidarity” with “all the students who were injured and affected by the incident,” and demanded that administrators “create a safe space for those students who have been or feel specifically targeted.” The tequila party, the statement specified, was just the sort of occasion that “creates an environment where students of colour, particularly Latino, and especially Mexican, feel unsafe.” In sum, the party-favour hats constituted – wait for it – “cultural appropriation.”

As Lionel Shriver made light of identity, I had no choice but to walk out on her

Lionel Shriver’s keynote address at the Brisbane writers festival was a poisoned package wrapped up in arrogance and delivered with condescension

‘Lionel Shriver’s real targets were cultural appropriation, identity politics and political correctness. It was a monologue about the right to exploit the stories of “others”, simply because it is useful for one’s story.’ Photograph: Murdo Macleod for the Guardian

Saturday 10 September 2016

I have never walked out of a speech.

Or I hadn’t, until last night’s opening keynote for the Brisbane writers festival, delivered by the American author Lionel Shriver, best known for her novel, We need to talk about Kevin.

We were 20 minutes into the speech when I turned to my mother, sitting next to me in the front row.

“Mama, I can’t sit here,” I said, the corners of my mouth dragging downwards. “I cannot legitimise this …”

My mother’s eyes bore into me, urging me to remain calm, to follow social convention. I shook my head, as if to shake off my lingering doubts.

As I stood up, my heart began to race. I could feel the eyes of the hundreds of audience members on my back: questioning, querying, judging.

I turned to face the crowd, lifted up my chin and walked down the main aisle, my pace deliberate. “Look back into the audience,” a friend had texted me moments earlier, “and let them see your face.”

The faces around me blurred. As my heels thudded against they grey plastic of the flooring, harmonising with the beat of the adrenaline pumping through my veins, my mind was blank save for one question.

“How is this happening?”

So what did happen? What did Shriver say in her keynote that could drive a woman who has heard every slur under the sun to discard social convention and make such an obviously political exit?

Her question was — or could have been — an interesting question: What are fiction writers “allowed” to write, given they will never truly know another person’s experience?

Not every crime writer is a criminal, Shriver said, nor is every author who writes on sexual assault a rapist. “Fiction, by its very nature,” she said, “is fake.”

September 12, 2016

Land of the Free

By John Nichols

Amy Goodman receives the Right Livelihood Award, also known as the alternative Nobel Prize, from Johan von Uexkull in Stockholm, December 8, 2008. (Reuters / Henrik Montgomery / Scanpix)

So much for the First Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

Despite well-established freedom of the press protections that outline and guarantee the rights of reporters who cover breaking news stories—including confrontations between demonstrators and authorities—North Dakota officials have charged Democracy Now! host Amy Goodman with criminal trespassing after she documented private security personnel’s use of dogs to attack Native American foes of the Dakota Access Pipeline project.

Video footage obtained by Goodman, an internationally respected and frequently honored independent journalist, helped to alert Americans to the tactics being used to stop demonstrations against the pipeline by the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe and their allies. On Friday, the Obama administration halted work on key portions of the $3.8 billion pipeline project—recognizing concerns raised by the tribe and environmental activists.

Amy Goodman calls the the battle against the pipeline “a renewed assertion of indigenous rights and sovereignty…”

That might have been expected to temper the zeal of local officials in North Dakota’s Morton County—who issued warrants charging Green Party presidential candidate Jill Stein and her vice-presidential running mate Ajamu Baraka with criminal trespass and criminal mischief after they joined the demonstrations Tuesday. But on Saturday afternoon, North Dakota’s Dickinson Press reported that:

Authorities have issued an arrest warrant for Amy Goodman of New York for a Class B misdemeanor, according to court documents.

Goodman, a reporter for the independent news program, can be seen on news footage from Sept. 3 documenting the clash between protesters and private security personnel with guard dogs at a Dakota Access construction site, including footage showing people with bite injuries and a dog with blood on its mouth.

The video footage has been widely cited by people who have since criticized the use of dogs by the security personnel.

Goodman has been open and outspoken with regard to her reporting from North Dakota.

In a detailed account of events that took place on September 3, the day the dogs were used, Goodman and Denis Moynihan wrote that “security guards attempted to repel the land defenders, unleashing at least half a dozen vicious dogs, who bit both people and horses. One dog had blood dripping from its mouth and nose. Undeterred, the dog’s handler continued to push the dog into the crowd. The guards pepper-sprayed the protesters, punched and tackled them. Vicious dogs like mastiffs have been used to attack indigenous peoples in the Americas since the time of Christopher Columbus and the Spanish conquistadors who followed him. In the end, the violent Dakota Access guards were forced back.”

Goodman’s accounts helped to raise awareness of the pipeline fight at a critical stage. And her assessment of the struggle has helped to put it in historical and contemporary context. “The battle against the Dakota Access Pipeline is being waged as a renewed assertion of indigenous rights and sovereignty, as a fight to protect clean water, but, most importantly, as part of the global struggle to combat climate change and break from dependence on fossil fuels,” Goodman and Moynihan wrote. “At the Sacred Stone, Red Warrior and other camps at the confluence of the Missouri and Cannonball rivers, the protectors are there to stay, and their numbers are growing daily.”

That is a fair assessment. It is also fair to say that an arrest warrant will not keep Amy Goodman from speaking up.

“This is unacceptable violation of freedom of the press,” Goodman said Saturday. “I was doing my job by covering pipeline guards unleashing dogs and pepper spray on Native American protesters.”

Her assertion is backed up by a constitutional amendment that reads: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”

That amendment applies everywhere, and to officials at every level of government—even those serving in Morton County, North Dakota.

20 brutal truths about life

Time is your most valuable asset–you need to prioritize how you spend it.

NOT MY USUAL STYLE OF POST AND SOME IT I REGARD AS COMPLETE RUBBISH BUT SOME INTERESTING, IF ON REFLECTION, PATENTLY OBVIOUS, POINTS ARE MADE.

Source:http://www.inc.com/matthew-jones/20-brutal-truths-about-life-no-one-wants-to-admit.html

By Matthew Jones

CREDIT: Getty Images

It’s much easier to talk about the weather, sports, and celebrities than your fear of mortality.

Unfortunately, the more time you spend pretending that ultimate truths don’t exist, the more time you waste not being your authentic self and getting the most out of every precious second.

Time, not money, is your most valuable asset. Allow the list below to ignite the spark of motivation you need to make better use of the time you have on this planet.

Sometimes we need to head into the storm to appreciate the light and have a renewed passion for the beauty of life.

Here are 20 brutal truths that every single person needs to hear.

1. You’re going to die and you have no idea when.

Stop pretending that you’re invincible. Acknowledge the fact of your own mortality, and then start structuring your life in a more meaningful way.

2. Everyone you love is going to die, and you don’t know when.

This truth may be saddening at first, but it also gives you permission to make amends with past difficulties and re-establish meaningful relationships with important figures in your life.

3. Your material wealth won’t make you a better or happier person.

Even if you’re one of the lucky ones who achieves his or her materialistic dreams, money only amplifies that which was already present.

4. Your obsession with finding happiness is what prevents its attainment.

Happiness is always present in your life–it’s just a matter of connecting to it and allowing it to flow through you that’s challenging.

5. Donating money does less than donating time.

Giving your time is a way to change your perception and create a memory for yourself and others that will last forever.

6. You can’t make everyone happy, and if you try, you’ll lose yourself.

Stop trying to please, and start respecting your values, principles, and autonomy.

7. You can’t be perfect, and holding yourself to unrealistic standards creates suffering.

Many perfectionists have unrelenting inner critics that are full of so much rage and self-hate that it tears them apart inside. Fight back against that negative voice, amplify your intuition, and start challenging your unrealistic standards.

8. Your thoughts are less important than your feelings and your feelings need acknowledgment.

Intellectually thinking through your problems isn’t as helpful as expressing the feelings that create your difficulties in the first place.

9. Your actions speak louder than your words, so you need to hold yourself accountable.

Be responsible and take actions that increase positivity and love.

10. Your achievements and successes won’t matter on your death bed.

When your time has come to transition from this reality, you won’t be thinking about that raise; you’ll be thinking about the relationships you’ve made–so start acting accordingly.

11. Your talent means nothing without consistent effort and practice.

Some of the most talented people in the world never move out from their parent’s basement.

12. Now is the only time that matters, so stop wasting it by ruminating on the past or planning the future.

You can’t control the past, and you can’t predict the future, and trying to do so only removes you from the one thing you can control–the present.

13. Nobody cares how difficult your life is, and you are the author of your life’s story.

Stop looking for people to give you sympathy and start creating the life story you want to read.

14. Your words are more important than your thoughts, so start inspiring people.

Words have the power to oppress, hurt, and shame, but they also have the power to liberate and inspire–start using them more wisely.

15. Investing in yourself isn’t selfish. It’s the most worthwhile thing you can do.

You have to put on your own gas mask to save the person sitting right next to you.

16. It’s not what happens, it’s how you react that matters.

Train yourself to respond in a way that leads to better outcomes.

17. You need to improve your relationships to have lasting happiness.

Relationships have a greater impact on your wellbeing and happiness than your income or your occupation, so make sure you give your relationship the attention and work it deserves.

18. Pleasure is temporary and fleeting, so stop chasing fireworks and start building a constellation.

Don’t settle for an ego boost right now when you can delay gratification and experience deeper fulfillment.

19. Your ambition means nothing without execution–it’s time to put in the work.

If you want to change the world, then go out there and do it!

20. Time is your most valuable asset–you need to prioritize how you spend it.

You have the power and responsibility to decide what you do with the time you have, so choose wisely.

Source: http://www.inc.com/matthew-jones/20-brutal-truths-about-life-no-one-wants-to-admit.html

Cynthia, the spy

During WWII, Betty Pack used seduction to acquire enemy naval codes.

by Hadley Meares

September 08, 2016

Betty Pack on her wedding day. (Photo: Churchill Archives Center, Papers of Harford Montgomery Hyde, HYDE 02 011/Courtesy Harper Collins)

These days the “honeypot” is a popular trope in espionage thrillers, with seemingly every high-level informant recruited via seduction by a ravishing female spy. But long before James Bond ever jumped across the roof of a moving train in books or film, the globe-trotting spy Betty Pack was wooing suitors for classified information on both sides of the Atlantic. Few people have elevated the habit of pillow talk to an art form quite like the crafty American-born intelligence officer, who “used the bedroom like Bond used a beretta,” Time magazine noted in 1963.

Pack’s code name at the British spy agency MI6 was “Cynthia,” and her clandestine escapades during World War II led her boss, Sir William Stephenson, to call her unequivocally “the greatest unsung heroine of the war.” Her discovery of the French and Italian naval codes, as well as her work aiding in the decades-long effort to crack the Enigma code, helped the Allies stay a few steps ahead of the Axis powers, and eventually, win the war.

Amy Elizabeth “Betty” Thorpe was born in Minneapolis, Minnesota, in 1910. She was an uncommonly restless child. “Always in me, even when I was a child, were two great passions—one to be alone, the other for excitement,” Betty told her fellow spy and lover Harford Montgomery Hyde, according to a new biography, The Last Goodnight. “Any kind of excitement—even fear.”

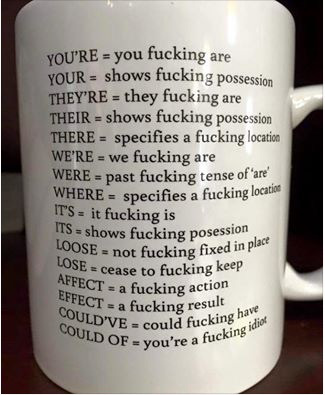

Bad grammar, busted

Seeing Things

So, I was sitting at home, flicking through a small book of Seamus Heaney‘s poems, entitled ‘Seeing Things‘ and, in the strange way these things happen, wrote this story. My story, of course, bears no relation to Heaney’s poetry or his 1991 collection of poems of the same name.

50 word stories

Guy at the bus stop asked for a light and I shrugged, did that pull my pockets out thing. The bus was late. It was cold. We both blew on our hands, stomped our feet. Suzie turned up.

‘Who were you talking to?’

‘That guy.’

‘What guy?’

‘You’re seeing things.’

Missing Zing

Police, security forces, media outlets and the general public were put on alert and asked to assist in the search for Zing, reported missing sometime in the 1970s, presumed lost. Zing is described as energetic, fun-loving and lively. You are advised to alert authorities and please, approach Zing with caution.

Story?

Photo Credit: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/sep/10/creative-writing-lesson-god-of-story-robert-mckee-tim-lott#img-1

A creative writing lesson from the ‘God of Story’

Robert McKee, has taught creative writing for 30 years. His seminars have attracted more than 60 Oscar winners, but are treated with suspicion by many novelists – including Tim Lott. Can he be won over?

‘Thou shalt not make life easy for thine protagonist’ … Robert McKee

Tim Lott Saturday 10 September 2016 09.00 BST

One of the main differences between humans and animals is that we compulsively tell stories – to ourselves and to others. The question of why this should be remains a mystery. Did our need to create narratives simply arise out of our facility for language? Is it nothing more than a form of rarefied entertainment? And do all the global and historical stories, in their multitude of forms, have anything in common – some fundamental strand of shared DNA that endures to this day?

Many thinkers, writers and critics have tried to identify the underlying meaning, origin and structure of stories, from Kipling, Goethe and Joseph Campbell right back to the original dramatic theorist, Aristotle, who in Poetics came up with the still extant three-act structure, along with catharsis, denouement, reversal (peripeteia) and much more besides.

The closest we have in the contemporary world to Poetics may be the classic text Story by Robert McKee. The so-called “God of Story” (as Vice magazine dubbed him) has been explaining his theory of how and why dramatic narratives emerge for 35 years, to the fascination of playwrights and screenwriters – his alumni have so far mustered 60 Oscar wins, including, among many others, William Goldman (Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid) Paul Haggis, Peter Jackson, John Cleese (who has attended the story seminar three times) and the entire writing staff of Pixar. However, McKee receives a more sceptical response from most novelists, at least, most non-genre novelists like myself.

Jonathan Coe, for instance, straightforwardly rejects McKee’s approach to storytelling: “For me, the essence of creative writing – whether it’s in the form of a novel, a play or a screenplay – is absolute freedom. So I have an instinctive horror of all systems which try to reduce writing to a series of rules to do with three-act structures and narrative arcs. It’s a sure recipe for formulaic writing.”

‘He has struck terror into my heart’: Esther Freud.

Esther Freud agrees. “McKee has always struck terror into my heart with the idea that something important and gripping has to happen on page 27,” she says. “Actors and writers I knew were always going to his courses, but my reality is that there are no real rules with writing – you just have to get on with it, and trust your instincts.”

Sadie Jones, who attempted for several years to make it as a screenwriter before she turned to novels, was the only writer I talked to who showed some sympathy for McKee. “When I was younger I entirely rejected the notion of being taught to write, and McKee’s name made me run in horror,” she says. “I later realised we can reject or accept the teachings of others as we choose. It’s a question of confidence. Insecurity doesn’t want to be lectured, but if we want to break the rules we can do it more thoroughly if we master them first.”

It is instructive that all three writers use the words “horror” or “terror” when talking about the “rules” of storytelling. It seems to indicate that novelists don’t merely dislike McKee, they fear him.

***

An intensive inquiry into the nature and structure of narrative, McKee’s “Story seminar” has been running in one form or another since he first gave the lecture at the University of Southern California in 1983.

McKee credits himself as inventing the language of Hollywood – it is not an empty boast

McKee credits himself with inventing the language of Hollywood – with its talk of the “mid-point climax”, the “inciting incident” and the “negation of the negation”, a phrase that originated with Hegel, but in movies means something like “the ultimate negative”: a fallen hero who is not merely defeated but wants to die, or a character who doesn’t simply lose faith in God but begins to hate God.

His claim is not an empty boast. So prominent is McKee in film-making circles that he had the rare honour, for a writing teacher, to be depicted at some length – satirically, but not without tenderness – by Brian Cox in the Charlie Kaufman-written film Adaptation. Kaufman, not incidentally, also distrusts “craft”. At a 2011 lecture at the BFI, he said: “I think craft is a dangerous thing,” suggesting that, at heart, it was “very hard to separate … from marketing”.

Sitting among something like 200 would-be writers, directors, producers and editors in the audience of a three-day story seminar at Regent’s College in London, I intend to find out if this scepticism is justified. A teacher of story myself, formerly with the Faber Academy and now for the Guardian Masterclasses, I do not have the same deep aversion to “craft” as some of my peers. But McKee is the most pure – perhaps even puritanical – of all modern story theorists, and I don’t expect to find his fundamentalism to my taste.

The audience has come from all over the world – from Australia, Thailand, Italy, Barcelona, even Siberia. They are mostly in their 20s and 30s. McKee, 75, shambles about the stage cradling a cup of coffee. A heavy brow embroidered with impressive eyebrows and a full head of hair give him a prophetic aspect. He reminds me of Charlton Heston playing Moses – a similarity underlined by his course literature offering his “Ten Commandments of Storytelling”, which include “Thou shalt not make life easy for thine protagonist” and “Thou shalt take thine story into the depth and breadth of human experience”.

McKee is a tartar about maintaining order and timekeeping. He makes it clear that if you turn up late, you will not be admitted. If you use a mobile phone, you will be fined. If you use it more than once you will be excluded. There’s a £10 fine for talking.

He reiterates these amiable threats sitting on a high stool, legs dangling in front of him like late-period Sinatra or the Irish comic Dave Allen. He does, in fact, consider himself a comic – “a comic says the world is shit. And you have to destroy it.”

He begins by making some fairly grandiose statements: “What we do as storytellers is crucial to the success of our species on the planet”… “All stories say how and why life changes. They equip us to live.” He poses crucial questions at the start of his lectures: “What is a story? What do all the story cultures and genres have in common?”, and spends the next three days trying to answer them, beginning with this suggestion: “All stories have same universal form. Not formula. There is no formula. But it’s like saying the form of music is remarkably simple – just 12 notes on a scale.”

Having started exactly on time the lecture continues from 9am in the morning to 8pm, with only three short breaks per day, two of which McKee works through, taking questions from individuals. His fundamental insight concerns the relationship between storytelling and the human psyche – how a story is structured basically reflects how a human mind, and a human life, is structured.

Every lived moment is an event taking place at a number of levels – interpersonal, internal, societal, institutional

Drama, for him, arises when we make “value-laden choices under pressure”. It is through these choices that we find out who we are – since all of us live under the cover of masks, which hide our selves from others, and even ourselves. Every lived moment of human life is a multilayered event taking place at a number of different levels – interpersonal, internal, societal, institutional. Story, then, is the sea in which all of us swim, and dramatists, screenwriters and novelists create “story” with the boring bits of life cut out. In story nothing moves forward except through conflict, and stories are metaphors for life – because to be alive is to be in perpetual conflict.

To grasp how McKee actually talks it is necessary to use italics extensively, as he constantly emphasises – in his slightly abrasive Detroit drawl – the key words in any passage of speech.

“Story design means choices – boiling down from life, far more material [than] you could ever use. A story is a series of events that have been chosen then composed. Like composing music.

“An event is a meaningful choice; that is, a choice with a value at stake. Values are at the heart of storytelling. A binary of human experience, positive or negative, truth and lies, love and hate, war and peace – all are binaries. They shift charge constantly. An event – in story terms – equals meaningful change in the value-charged condition of a character’s life, achieved through conflict.”

McKee doesn’t confine himself to talking about writing: he wanders off-piste frequently. The course literature warns the audience to be aware that “Mr McKee has strong opinions on religion, politics and society and uses strong language.” This is not an understatement. What follows is a selection of quotes from the lecture, all of which are extracts from larger anecdotal reflections.

“People are not equal. If you’re a liberal at 30 you have no brain.”

“If you show your woman your inner crybaby she’s out the door. Never say what you deeply feel and think to your woman.”

“A lot of women’s films just say, ‘All men are shit’ – can you imagine a man writing something the same?”

If McKee’s tongue is in his cheek – and it may well be – he conceals it well. But his predilection for winding up his audience does little to dilute what I am beginning to realise is the strength and clarity of his teaching.

At the conclusion of the third day, when he has finished his scene-by-scene deconstruction of Casablanca, he sings, in a slightly quavery voice, the theme tune of the movie, “As Time Goes By”. This song, he believes, points to the underlying message of the film, the tension between Being and Becoming – that is, the idea of holding on to what is permanent within you while you are forced into incessant change by circumstance.

“You can have both – if you learn to love. And that is what I wish you all.”

With these words, the three-day seminar is concluded. He promptly receives a standing ovation from the entire audience.

***

When we meet, after the course, in McKee’s sparsely furnished rented flat in Chelsea, I ask first about the element of his lecture I found particularly fascinating – the relationship of life as it is lived to the scene-by-scene dramatic structure of a story.

“In film, there’s this constant irony of expectation not meeting result. Out of this turning point comes the opposite – a turning point for the better. Then the positive shifts to the negative almost automatically. No wonder primitives believed in the unseen hand, because this dynamic is so relentless,” McKee says. “We focus in story on moments when life is interesting … when the world reacts in a way which, in retrospect, you think you should have seen coming. Human beings have imagination and that makes the shit really hit the fan. Because you also have animal instincts. Therefore you have inner conflicts. It’s not only the world that doesn’t react the way you expect: you don’t react the way you expect.”

Story, for McKee, is a consolatory refraction of reality. By witnessing our own true inner dilemmas realistically on screen or page we receive a form of relief. But it is also, at some level, an exercise in denial. “Denial makes the world go round,” he says. “If you live in unvarnished reality for one minute you have to fantasise … it’s just too awful. You have to deny it. Story mediates the contradictions that make life unlivable. It is an evolutionary adaptation to consciousness.”

Is this element of denial – in many Hollywood films in particular – the reason so many fiction writers are nervous about the dynamics, or even existence, of story structure? McKee looks scornful – an expression that comes easily to him. “That’s because they think ‘art is instinctive’. Which is fucking nonsense. You don’t want constipation from analysis, you don’t want to get in your own way; but you have to learn your craft. ‘It won’t stop you being a genius’ as Delacroix said.”

Is that also true for literary, non-genre novelists?

“Every writer is a genre writer. If you don’t know the genre, the audience does. There’s no such thing as non-generic story; if you think that, your head is up your ass.”

When I suggest there are elements of his lecture with which many people might not agree, feminists in particular, his voice rises several decibels.

“Really? You think I’m not a feminist? I say just as many critical things about male behaviour, but it goes unnoticed. I treat people in a universal way. Women are just as fucked up as men, but you’re not allowed to say that. Once you say it you’re perceived as an anti-feminist. Women cannot be criticised. Well, guess what …”

He leaves the sentence unfinished.

Does he really believe that if you’re liberal at 30 you have no brain?

Anything that puts meaning and beauty into the world in the form of story helps people live with more peace and purpose

“My attitude is, they’re both wrong. If liberalism becomes extreme and sentimental and unthinking it’s a dead end – same with the right wing. I hate them all. I hate institutions.

He has spent so much of his life doing these lectures, rather than actually writing screenplays. What’s his motivation?

“Life is absurd. But there is one meaningful thing, one inarguable thing, and that is that there is suffering. Fine writing helps alleviate that suffering – and anything that puts meaning and beauty into the world in the form of story, helps people to live with more peace and purpose and balance, is deeply worthwhile.”

McKee’s political opinions may certainly appear overripe to most contemporary readers, but he doesn’t give a damn, which is perhaps one of the things that makes him a good teacher. At the end of his seminar I was handed a piece of paper on which I was asked to write the most important thing I learned on his course. A great number of possibilities crossed my mind – particularly how a narrative only progresses through conflict and meaningful change (with a value at stake), or how to show deep character (“choice of action in pursuit of a desire under the pressure of life”); but in the end I decided very quickly. “Everything is subtext,” I wrote. This is really what McKee teaches above all else – that the best drama always happens below the surface.

As I hack away at my eighth novel, his voice is now in my head much of the time. If McKee is the God of Story, then I am no longer an agnostic – I am a convert.

• Tim Lott offers mentoring for writers at theguardian.com/masterclasses. Robert McKee’s new book, Dialogue, is published by Twelve.

September 11, 2016

Writing today?

Creative writing

My best writing tip by William Boyd, Jeanette Winterson, Amit Chaudhuri and more

Got a brilliant beginning, or the seed of an idea? Authors offer their most important piece of advice – from finding a voice to the all-important ending

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/sep/10/my-best-writing-tip-william-boyd-jeanette-winterson

Jeanette Winterson, Rose Tremain, William Boyd, Philip Hensher, Tessa Hadley, Toby Litt, Amit Chaudhuri, Kathryn Hughes, Naomi Alderman, Jonny Geller, Nikita Lalwani and Blake Morrison

Saturday 10 September 2016 08.00 BST

Audition your ideas – Rose Tremain

Most writers experience what I call the “September paradox”: just when the weather is warning of the dying season to come, the creative mind (probably refreshed by a hot foreign holiday, or a breezy one on the north Norfolk shore) discovers that an internal springtime has arrived and new ideas are popping up all over the place.

It’s important to snatch this moment. Give these green stems of thought your passionate attention, otherwise they may be dead by Christmas. Water well and weed diligently. But here’s my advice on how to proceed: treat these seedlings like job applicants. You don’t know who they are yet. They may seem feisty, clever or captivatingly beautiful, but are they going to offer anything original? Most important, are they likely to be inspirational companions, who will lead you to create the best work that you’re capable of? WB Yeats’s advice to writers, “Do not hurry, do not rest”, is relevant here.

As the autumn advances, keep a vigil on the applicants. Then, you’ll gradually begin to know what they’re leading you towards. Are you embarking on the long road to something truthful, or just moving towards a heaving skip of recycled bullshit? The landmass of the western world is slowly being submerged by bad books. You don’t want to add to this tonnage, so go slowly into your analysis of what it is you’ve got to say. Does it have real emotional and intellectual grip? If so, then start gathering all the knowledge you’ll need to set forth on your great writing adventure.

Only remember that the September applicants may not fulfil their promising CVs. The “big novel” that shrinks into a Christmas card list is, in the writer’s world, a familiar disaster of the festive season.

• Rose Tremain taught creative writing at the University of East Anglia and is its former chancellor

Pay attention – Philip Hensher

Think about how people reveal themselves through behaviour, and focus on the externals of gesture, expression, dialogue and settings. It’s tempting, given the limitless power of the omniscient novelist, to plunge into a character’s head and write, baldly, “Laura felt painfully envious”. But what has more energy is the analysis of how a character in the grip of painful envy carries herself, speaks, looks, and even dresses. We always know, if we are observant, how a person who is desperately, secretly in love with another behaves. The trick of fiction is to extract the ways in which other emotions affect the outer crust, too, and by observing the characteristic walk of a human being overcome with happiness, say, making the reader feel observant, and not just laboriously informed.

How this carriage affects the characters around her, too: because fiction does not amount to much if it is just one character standing in a stairwell, pondering gravely about past events. If the first lesson of fiction is about the leakage of the abstract into the world of the physical, the second ought to be that fiction is about the way one character’s desires will crash into another’s, and a third, and a fourth, when all that seems to be happening is four friends meeting in a pub, or working together in an office, or finding themselves thrown together by chance. The episode that consists of one person alone leads to nothing much: the episode of four different characters with their own ways of life moves in multiple directions.

To do this, the beginning writer is going to have to undertake some systematic observation, notebook in hand. No novelist worth reading ever sat at home, entranced with the words spooling out. They paid attention to the life of the streets, to the mannerisms of their friends, to the way a small child speaks when he is hoping not to get found out. Fiction looks outwards.

• Philip Hensher is professor of creative writing at Bath Spa University

Plan your ending – William Boyd

About once a month or so, when someone says to me, “I’ve got this great idea for a novel/film/play/TV series” and then outlines the (usually pretty good) opening, I say: “So – how does it end?”. Ninety-nine times out of a hundred the answer is: “I haven’t quite figured that out yet.”

Therefore my default response to all “great” ideas in the writing business is to do with the ending. A good ending can redeem a mediocre idea. A bad ending can sink a really good idea. As soon as you know how your narrative ends – in whatever medium – then a huge percentage of the problematic issues that arise in the writing will be solved.

If you have a clear sense of how your story will end then you can, as it were, rewind to the beginning and plot any number of various routes that will allow you to arrive at that desired ending – with its attendant catharsis, of course. If you start writing (however striking your original idea) with no sense of how your story will end, then life becomes progressively harder. Flailing around. Writer’s block. Draft after draft. This is how novels get abandoned; film scripts bottom-drawered. The thing to do is to stop and envisage your final pages, your final scene. Take your time. What note do you want to strike? What surprise do you want to spring? What denouement will justify this journey?

It may sound mechanical, but story-telling is a very complicated business, full of moving parts and many cogs engaging. You can’t rely on the Muse to descend and sort it all out for you. A bit of serious forethought about the conclusion will mean you don’t need the Muse’s help at all.

William Boyd is a novelist and screenwriter

Know your characters – Claire Messud

In fiction, character is (almost) everything. We discuss “the elements of craft” – characterisation, plot, point of view, dialogue, detail, setting, style, and so forth – as if they were separable, as if you could disentangle them one from another. You can’t, of course; but when you filter almost all things through the specificities of character, many questions resolve themselves, almost miraculously.

Each of us is, in any given moment, the sum total of our temperament and experiences up to that point. Our baggage and idiosyncrasies may be suggested in our appearance; but much is invisible to the world. We all know that if there are three people in a room, each will tell a different story about what happened there – so character determines the story itself. But it also determines what will unfold – the plot.

Ten rules for writing fiction

As a writer, when you create a character, you don’t simply create his exterior (the wispy goatee, the receding hairline, the Liberty print shirt and expensive loafers); you must also come to know who he is (bullied in school, uneasy in friendships, veering between eager to please and cruel; vain but pretending not to be), and what has formed him (a Catholic school in the Sydney suburbs? A comprehensive in Exeter? Born with a silver spoon; or things started off comfortably, but his father’s business failed when he was 11? Raised in the shadow of three older siblings? Or alone with a single mum?). You must know his passions (loves pugs? Bicycle racing? First world war history? Talmudic study?) and his fears.

Once you know this person as well as you know yourself (or better), and once you put him, or her, in a particular place in a particular time, your character can only really act (or react) in a limited number of ways. He will notice only certain things, and those things only from a particular perspective; he will interact with others as only he can. If you’re using the first person, or the third person privileging this character, your diction and syntax – your very writing style – will be shaped by this person.

So much about a character is invisible, in fiction as in real life; but what lies beneath the surface will affect every aspect of your story. If you really take the time to figure out who you’re dealing with, much will become clear.

• Claire Messud is a senior lecturer in creative writing at Harvard

Distance yourself – Tessa Hadley

This is something I talk about with my students until they’re sick of it: teaching yourself to read your own writing as a reader. It’s very difficult; it makes your mind ache – not only when you first start trying, but always. Three minutes ago you were tussling down inside the sentences, trying to drag out of the air the perfectly right words to express a mood, or catch a person’s physical presence or a place’s, or trying to find the perfectly right thing for your character to say. Then you blink your eyes, pull back from the screen or the notebook, try to imagine you’ve never seen this writing before.

This is the exact equivalent of a painter pulling back from her canvas, squinting at her work, before she dives forward and changes it again. It’s a revelation, really – how surprisingly visual reading is. Go back a few pages, start reading as if you’ve never seen these words before. How does it seem? Suddenly you’ll see what you couldn’t see when you were down among the undergrowth. It’s going on too long, it’s sentimental, the tone’s too heavy, there are too many sentences with same rhythm, there’s an inadvertent repetition. Or, something’s missing. You could print out your work, to try to see it freshly – or type it up, if you’re writing longhand. Or you could look at it full screen on the computer, with a different background, more like the pages of a book. The trouble is you have to make this effort not once, but over and over. Your mind will be sore from the effort of reading the same old thing so many times as if it were new. But unless you do it you won’t know what you’ve written, or whether you’ve got it alive and whole, faithfully, on to the page.

• Tessa Hadley is professor of creative writing at Bath Spa University

Don’t be afraid to start again – Jeanette Winterson

Creativity is inexhaustible. Experiment, play, throw away. Above all be confident enough about creativity to throw stuff out. If it isn’t working, don’t cut and paste – scrap it and begin again.

• Jeanette Winterson is professor of new writing at the Centre for New Writing, University of Manchester

Be surprising – Blake Morrison

When the sweetly idealistic Nina asks Trigorin, in Chekhov’s The Seagull, to describe what it’s like to be a famous writer, he tells her it’s torment. Day and night, the compulsion to write never leaves him, he says. He can’t rest; can’t forget the unfinished novel he’s meant to be working on; can’t see a cloud in the sky without thinking of a comparison (with a grand piano, say) he might use somewhere; can’t trust the praise of encouragement of friends; feels nervous, miserable, overwrought, half-mad, and when any new work of his appears in print realises that it’s all wrong. Nina doesn’t listen, to her cost. But aspiring writers would do well to heed the warning. To be forever “consuming your own life”, as Trigorin puts it, is no picnic.

But as he also admits, the act itself, when you’re fully immersed, is enjoyable. And to write “in a sort of haze”, unsure what you’re up to but simply compelled, may be no bad thing. Say you sit down to write a poem, or an episode, set on an autumn morning. You have the idea but feel stuck, hamstrung, overwhelmed by your literary forebears: mist and mellow fruitfulness have been done to death. So has woodsmoke but suddenly you’ve the smell in your nostrils and are reminded of (or imagine) a particular fire, logs crackling in a grate, two wine-glasses, a bitter argument, a crimson stain on a sheepskin rug – perhaps the scene is a winter night rather an autumn morning and the logs are imitation logs in a modern gas fire, but that’s fine, where you’re being taken is more interesting than what you’d planned. Just go with it – you can always change it later.

In other words, if you only write what you’re expecting to write, you’ll be bored. Take a risk. Work against the grain. Don’t be afraid to make a deathbed scene comic, or to show a murderer being kind to animals. Truth is surprising, and surprise is the key – surprising the reader but also, in the first place, surprising yourself.

• Blake Morrison is professor of creative and life writing at Goldsmiths

Use a pseudonym – Toby Litt

Trying to write your very best can stop you writing your very best. There’s a couple of ways to get around this. Most obviously, you can let yourself off writing as well as you’re possibly able. You can say: “This is draft zero, not even a first draft, so there’s no need for it to be anything but an exciting mess.” Lots of writing advice is about taking the pressure off by lowering the expectations you have of each draft. That’s the very best part of your very best.

A different approach, one I often suggest to writers who are struggling, is to dodge the issue entirely.

Instead of writing your novel or story as you, and anticipating all that pressure of owning your work (having friends read it as yours, reading it out in public after being introduced as you), give yourself a pseudonym to work with. Make up the name of a writer you just might have been, if you hadn’t been yourself. Type it in at the top of the manuscript. Print it out. Sign it. (I’m serious.) This draft is no longer by you (at your very best). This draft is by them, whoever they turn out to be.

Sign up to our Bookmarks newsletter

Read more

Now, whenever you need to figure something out about your story, from the overall form to the punctuation of a sentence, you can shift responsibility. The question isn’t “How do I, at my very best, write this?” but “How does so-and-so write this?”

By writing under a secret pseudonym, you will gain a collaborator who has no hang-ups, no responsibilities, no history. They will, I promise, help you write better – perhaps even better than your very best.

• Toby Litt is a senior lecturer in creative writing at Birkbeck, University of London

Do your research – Kathryn Hughes

There’s this odd idea that, when it comes to writing non-fiction and biography, all you have to do is get the facts straight in your head and then spool them out in a listless monotone. The experience is rather like sitting next to a pub bore, who starts every sentence with “The interesting thing is …” without noticing that you’ve already turned away and started to talk to someone else.

So it’s all about finding a way to tell your story about the past as if it is actually very present. And, no, that doesn’t mean employing the historic present tense, which is used far too often, and mostly badly. Instead, you need to marinate yourself in your material, consuming everything that you can get your hands on about your subject (we’ll assume you’re writing a biography) and the period in which they lived. Read the books that they read, not just the ones that they actually wrote. Track down their great-great-granddaughter and ask if there any relics (snuffboxes, spectacles diaries, not actual bones) that you could sniff or finger. Saturate yourself in your subject’s correspondence until you know the name of their neighbour’s dog or the date on which their child’s first tooth fell out.

Only once you’ve metabolised this material, taken it into your own body, let it settle and mulch inside you for weeks, months or years, will you have a hope of making it live again. The first time you sit down to write, after a period of research immersion, try it freestyle. Don’t hug your notes, or pore over timelines. Write the narrative from memory, letting details float to the front of your imagination, while others recede into the background. With any luck, your narrative will feel fresh and juicy because that is how it lives in your imagination. Only at this point should you go back to your data and make sure that you haven’t invented anything. Because that really isn’t OK.

• Kathryn Hughes is professor of life writing at the University of East Anglia

Commit to finishing – Nikita Lalwani

Making the decision to finish a piece of work is crucial. It is this seriousness of intent that gives you half a chance of writing something that will have a life beyond your desk. It might be easier to deny this aspect and pretend that you will never get there – how dare you presume that this folly of a story you are bashing out can be something real, a book for an actual audience, and more to the point, isn’t it very likely you will write a bad ending? You made the whole thing up, after all, and this contraption that we call plot could easily come apart. So goes the insecure writerly mind in the dark hours. But once you believe that you will reach the end of your book, whatever shape that takes, then it can make it easier to write with the kind of conviction and purpose that makes a reader want to turn the page.

In Six Walks in the Fictional Woods, the playful and profound series of essays on writing by Umberto Eco, he likens the act of reading to playing a game: “a game by which we give sense to the immensity of things that have happened, are happening or will happen in the world”. By saying to yourself that you will complete the story, you are acknowledging the nature of this transaction between yourself and a potential reader – you are in the game.

Of course, your story may never have a reader, but I believe there are very few benefits to thinking in that way. Time and time again I have seen talented students ditch their manuscripts at the half-way point, and less talented students reach the end, rewrite the whole book enthusiastically, and get published. Something about ending your novel can elevate it beyond what you might feel is a shameful and insubstantial piece of drivel that you have written in your pyjamas and make it a contender in your own mind. Respect your process and make a pact to close the deal.

Nikita Lalwani is a lecturer in creative writing at Royal Holloway, University of London

Forget brilliance – DBC Pierre

One intimidating thing about starting to write is the array of polished advice about it. Pearls seemingly formed between tennis and cocktails, brilliantly deployed by the greats between six and nine every morning but Sunday. Suddenly our biggest hurdle isn’t character, pace or plot, but that we can’t even play tennis.

I’m talking about the otherness of our peers. If our toolkit belongs to Fitzgerald and Faulkner, our first issue will be getting over writing relative crap at the outset. But whoever said “writing is rewriting” knew the science of crap, the practical lesson being: it’s easier to improve it than to originate brilliance. To improve it we need to have it, which means writing it, and that requires a different ethos than the one we probably sat down with, glowing with hope and expectation.

My suggestion is this: we stop ourselves from writing what we have to write by pausing to fret over details and risks, and by filtering ourselves through subconscious juries. Sparkles of gold can appear if we just get enough words written, which means write like the wind, don’t look down. Make a pact never to show anyone, build a mound of dirt, skim it later for anything that excites you. Skimming is a different job, sober and honest, of an archaeologist crumbling dirt in her hands. Separate any glimmers into a new document and build on them, connect them, repeat the process. Those glimmers are also evidence that things can work out, making them power pills for the will; use them to press on. We might start by sifting crap but a couple of passes can lure out real pipe-puffing linen-wearing tennis-playing vigour.

The key then is to not try playing tennis.

• DBC Pierre is author of writing guide Release the Bats

Ignore tips – Amit Chaudhuri

The one tip I give to students of writing is to disregard tips. These might have to do with arresting opening sentences, or they may simply concern the tools of the trade – character, setting, description, plot. The four words, chosen randomly, are vague descriptive categories once used in literary departments, where, with “tone”, they’ve been abandoned, only to be repeatedly invoked in creative writing classes along with “craft”, “sentence”, and that nervous-making shibboleth, “point of view”. I’m not sure what “character” means. Is it an aggregate of physical features – nose, eyes, hair – which add up to a bodily presence into which, as if it were a vessel, you pour psychological life: thoughts, memories, political views? Can you “fictionalise” a real person by adding a moustache to his face, or a stammer to his speech?

Why is it that, when we invent characters, the process of invention involves an excavation from the subconscious, as if we were trying to remember someone we knew decades ago; while when we write of people we know, we see them in our imagination as independent entities who are essentially strangers to us? To create a character is to unlearn what we know: tips will be unhelpful. Unhelpful, too, is the hierarchy in which these categories arrive, with character at the centre, and setting important inasmuch as it is where plot or story – or what happens to the protagonist – unfolds.

For me, the protagonist is only one element in a story: evening, room, wall, smoke, car, are other possible ones. It’s a prejudice inherited from the European Renaissance that the human must occupy centre stage, everything else being secondary. A work of the imagination gives us not a protagonist, but the intimation of a world. No one thing in a world – object or person – has centrality.

If I have one more tip, it’s this: give nothing centrality, because writing is about continually shifting weight from one thing and moment to the other.

• Amit Chaudhuri is professor of contemporary literature at the University of East Anglia

Just do it – Naomi Alderman

You learn the most from sitting down and doing the work, regularly, patiently, sometimes in hope, sometimes despairingly. When you have something that seems complete, show your work to people you trust to be honest but not malicious. Put it aside for six months and reread it. Expect to be disgusted by your own early work. If writing is your vocation, if you hope that it might be your salvation, push on through the disgust until you find one true sentence, a few words that say more than you expected, something you didn’t know until you set it down.

There are no “tips” for this process really; it’s painstaking and intense and doesn’t often feel pleasant.

However, I think there are tips for how to sit your bum on the chair and do the work.

Stop reading so many articles on the internet about how to write. You’re allowed one a week. Instead, spend that time actually writing.

Use a writing prompt to get you started. I recommend Judy Reeves’ book A Writer’s Book of Days.

Write for 15 minutes every day. Set a time in advance, set a timer. Try to write at the same time every day. Your subconscious will get used to the idea and will start to work like a reliable water spout.

Remind yourself, every day, that you’re doing this to try to find something out about yourself, about the world, about words and how they fit together. Writing is investigation. Just keep seeking.

• Naomi Alderman is professor of creative writing at Bath Spa University

Once you’ve written your masterpiece, it’s time to get it published …

Once you’ve written your masterpiece, it’s time to get it published …

How to get an agent

Jonny Geller, joint chief executive of Curtis Brown

Research: Who does an agent represent? What is their area of expertise? How many new writers do they nurture? If you sent your romantic saga to an agent who specialises in military history, you will have wasted your stamp.

Be brief: If you can’t write a short letter, you probably can’t write a long novel.

Don’t do the agent’s work for them: A mis-pitch is an unnecessary hurdle to jump, so no “Sherlock Holmes meets Jack Reacher” combinations, please.

Don’t send your first three chapters until they are so good you couldn’t bear changing a word: If you don’t love it, we won’t. You only get one chance to read something for the first time so don’t think you can fix that problem later. There won’t be a later.

Wait: Leave at least four to six weeks before hassling the agent for a response.

Be positive: We are looking for terrific books by great new authors so be confident and expect success. If you write to us anticipating rejection, we will smell it and probably agree with you. It is a wonderful thing to create, produce and believe in yourself.

• Jonny Geller’s recent Tedx talk was “What Makes a Bestseller?”

How to get published

Susanna Wadeson, publishing director at Transworld

There are six elements I think about when considering a project.

Story: This comes first, in both fiction and non-fiction. What’s the story? Do I care? And am I the right editor to help tell it? Does it grab me? This starts with the all-important pitch – a two-line summary – but I have to be sure the whole book will deliver on that promise and has a fluent and compelling narrative thread.

Platform: Who is the author and do they have a public profile to help us promote the book? Do they have an existing following/readership on TV/radio/social media? Essentially, is there a chatter-factor?

Voice: Is the writing distinctive and a pleasure to spend time with? Is it elegantly constructed? Witty? Surprising? Am I moved to laugh? Cry?

Authenticity: Am I comfortable with the match of author and subject? Does it feel opportunistic or manufactured, or does the author have a genuine passion to convey?

Originality: Is it really new? Will the book shift our views about who we are, the world we live in?

Audience: Yes it is interesting/fun/moving/different and I love the author, but is there a market for it? Will anyone feel they need it to the extent that they will pay £15 for it?

Postcard from a Pigeon

- Dermott Hayes's profile

- 4 followers