Jon Bloom's Blog, page 9

June 27, 2020

What Sin Will Never Quench: Why We Trust in Broken Cisterns

What exactly is “evil”? Given that the first manifestation of human evil recorded in Scripture involved a desire for this kind of knowledge, the question itself should inspire some trembling. Only God has the capacity to comprehend and the wisdom to administrate the depths, dimensions, expressions, and purposes of evil.

Yet Scripture makes clear that God wants us to understand what it means for us to commit evil. The whole Bible, from the fall in Eden onward, is one long account of the catastrophic fallout of evil’s infection of the human race and God’s unfolding plan to ultimately overcome that unfathomable evil with an even more unfathomably wonderful good. God can give us the strength to sufficiently comprehend what he wants us to comprehend (Ephesians 3:18). In fact, God wants our “powers of discernment trained by constant practice to distinguish good from evil” (Hebrews 5:14) so that we might “turn away from evil and do good” (Psalm 34:14).

One of the wonderful things Scripture teaches us is that turning away from evil is not, at its essence, mastering a long list of bad things to stop doing and good things to start doing. Rather, at its essence, God is inviting us to abandon what will ultimately impoverish us and increase our misery, and to choose instead what will ultimately enrich us and increase our joy.

Essence of Evil

One of God’s clearest explanations of this reality comes through the prophet Jeremiah. This man had a very hard calling, spending his forty-year public ministry preaching to stubborn, stony hearts and weeping as God brought his long-forewarned judgment on Israel for centuries of idolatrous rebellion (2 Kings 17:7–14). Through Jeremiah, God expressed his profound dismay and grief over how, in spite of all he had done to create, redeem, establish, protect, and provide for them, as well as warn them over and over, his people had abandoned him and sought their protection and prosperity in the false “gods” of the nations around them:

Cross to the coasts of Cyprus and see, or send to Kedar and examine with care; see if there has been such a thing. Has a nation changed its gods, even though they are no gods? But my people have changed their glory for that which does not profit. (Jeremiah 2:10–11)

Not even the pagan nations, whose gods didn’t even exist, had done what Israel had done. Which led God to exclaim in pained exasperation,

Be appalled, O heavens, at this; be shocked, be utterly desolate, declares the Lord, for my people have committed two evils: they have forsaken me, the fountain of living waters, and hewed out cisterns for themselves, broken cisterns that can hold no water. (Jeremiah 2:12–13)

This is a remarkable statement. God lays open the human heart and shows us what evil really looks like. Evil is when the creatures of God, his own image-bearers, forsake him, their very source of life, the source of all that quenches their deepest thirsts, and try to quench those thirsts apart from him. Evil is trying to find life anywhere but in God.

We hear echoes of Eden in the Lord’s words. Like Adam and Eve eating the forbidden fruit, Israel’s sin wasn’t merely that they disobeyed God’s commands. Their disobedience exposed a deeper, deadly problem: treachery against God had taken root in the deepest places of their hearts. Sin revealed that they placed their trust, pledged their allegiance, and sought their satisfaction in something or someone other than God. They exchanged God for things that were no gods (Romans 1:23).

And this has always been the core evil of every sin — of all our sins: forsaking the Source of greatest joy (Psalm 16:11), believing we’ll find more joy elsewhere.

Broken-Cistern Builders Meet the Fountain

But God did not leave us to perish beside our broken cisterns. Although we forsook the Source of living water to slake our thirst in empty wells, the Source, rich in mercy, sent the Fountain to bring us living water.

On a hot Samaritan midday, just outside of Sychar, an experienced builder of broken cisterns was on her way to Jacob’s well. In her heart were the ruins of five relational cisterns she had tried so hard to make, each now desolate and bone-dry. If nothing changed, soon there would be a sixth.

When she arrived at the well, she found the Fountain sitting beside it. The Fountain was waiting for her. He had come to save her from all her futile hewing and to give her “living water” that would “become in [her] a spring of water welling up to eternal life” (John 4:10, 14). She was skeptical till he gave her a taste. Then she drank deeply, and for joy went and told all her fellow townsfolk about the Fountain. Many of them drank deeply too.

In the woman at the well, we see ourselves. The cisterns she tried to make may be different than ours, but ours are no less futile and empty. Apart from God, everything becomes a dry well. Nothing in this world can channel or store the water we long for most. Everything here leaks and eventually breaks apart and ends. And choosing such broken cisterns over the Fountain of living water is the essence of human evil, evil that appalls the heavens.

But in Jesus’s encounter with this woman, we see the heart of God for broken-cistern builders. Like ancient Israel, we all are warned that a judgment is coming upon those who prefer arid dirt to God’s living water (2 Corinthians 5:10). The Fountain has come first, though, not to bring judgment, but to seek and save all who will repent of the evil of forsaking God, turn away from their dry wells, and receive the water the Fountain will give them (John 12:47). And it’s not uncommon that we find the Fountain waiting for us beside one of our ruined wells.

Choose the Greatest Joy

The core evil of the original sin was believing the forbidden knowledge of good and evil would yield more satisfaction than God. The core evil of ancient Israel was believing idols would yield more protection and prosperity than God. The core evil in all our sins is believing some broken cistern will give us greater life and joy than God.

Which means the fight between good and evil in the human heart is a fountain-fight: Which fountain do we believe will really satisfy us — right now, in this moment of temptation? The struggle to discern good from evil is a joy-struggle: Which well has the most real and longest-lasting joy in it? Christian Hedonism is a serious and essential enterprise, because everything hangs on choosing the superior joy.

Which is what the Fountain of living water holds out to us. He offers us the deepest satisfaction, the sweetest refreshment, and life forever (John 4:15), and he offers to fully pay the wages of our sin, the appalling evil of our futile broken-cistern hewing (Romans 6:23). And as with the man who found a treasure in a field or the merchant who found the pearl of great price (Matthew 13:44–46), what he essentially requires of us is almost unbelievably wonderful: to forsake what will lead us only to misery and despair, and to choose the greatest joy.

June 22, 2020

Groaning, Waiting, Hoping: How to Live in a Fallen, Fragile World

A late verdant spring is at this moment giving way to a lush early summer in Minnesota, the state where I have sojourned these nearly 55 years. Walking outside on a fair morning, when the brilliant new variegated greens of the trees and grasses are bursting with life, when a gorgeous spectrum of colorful, fragrant blossoms waves in the gentle breeze and seems to silently sing for joy, when the deep blues of our abundant rivers and lakes quiet frenetic thoughts, and everything is awash in the golden light of a blazing star ascending in a sky-field of azure, one can almost wonder if Eden has returned.

Almost. Then a police vehicle speeds by me, followed soon by a blaring ambulance. Then beneath the bridge I see the decaying body of a songbird whose voice so recently added more beauty to our urban avian choir. Then I pass by burned-out, boarded-up buildings that testify to the great pain and anger that just days ago surged through our streets after a man was needlessly killed under the knee of an officer of the peace. Then I read of another priceless life lost to a global pandemic, adding to the terrible death toll of hundreds of thousands and to the millions of living hearts broken. And then I read of the global economic crises driving hundreds of millions to desperate places.

The stories keep coming. Another child subjected to the nightmare of sexual abuse, the impending demise of the Great Barrier Reef, the slaughter of 92 soldiers at the hands of armed religious zealots in central Africa. I don’t wish to read more. Eden has not returned.

Looking at this sun-drenched spring morning world, I delight in its glory and the glory of the One who created it. But woven into this sublime beauty is sorrowful gore. The world labors under a profound and horrible brokenness. I hear its groaning and groan with it to the One who created it. But there is hope in this groaning, for the world’s Creator is also its Redeemer, and he has promised that something greater than Eden is coming.

Not the Way It Should Be

Why is this world so profoundly and horribly broken? And why do we intuitively and deeply feel it should not be this way? The fact that mankind can’t help but ask both questions is revealing.

Modern man, try as he might to convince himself of naturalism — that the world is not broken, just brutal, that we are merely the products of a long, ruthless organic competition for survival, that there is no objectively moral way the world “should” be — he cannot escape the instinctive sense that something here is deeply disordered.

There’s something about our life that ought to mean more than spawning more life. There’s something about sickness that ought to be cured. There’s something about calamity that ought to be prevented. There’s something about injustice that ought to be brought to justice. There’s something about death that ought not to be our ultimate end.

And there’s something about our own moral depravity that ought not to be part of us — that dark dimension of us that history and headlines remind us has potential to metastasize into something horrific if given rein and that makes us long for forgiveness and redemption and emancipation.

Genesis of the Groaning

These deep, inescapable intuitions come from somewhere. And the Bible tells us where. They are part of our collective human memory, recalling an ancient catastrophe, when our first ancestors, and all of us since then, defied the Creator, resulting in a devastating fallout.

Because you have . . . eaten of the tree of which I commanded you, “You shall not eat of it,” cursed is the ground because of you; in pain you shall eat of it all the days of your life; thorns and thistles it shall bring forth for you; and you shall eat the plants of the field. By the sweat of your face you shall eat bread, till you return to the ground, for out of it you were taken; for you are dust, and to dust you shall return. (Genesis 3:17–19)

And when “sin came into the world through one man, and death through sin . . . so death spread to all men because all sinned” (Romans 5:12). But death was not the only consequence of the human fall; the entire “creation was subjected [by God] to futility” and “has been groaning” ever since (Romans 8:20, 22).

When humanity fell by attempting to seize what belongs solely to God (Genesis 3:5), God commanded that the infection of appalling evil that entered us spread into the entire created world we inhabit. Why? In order that we would have reflected back to us in the profound and horrible brokenness of the world the moral horror of sin.

That’s why the world seems to writhe with suffering. That’s why we know things shouldn’t be this way. Creation’s anguish is a witness and reflection of the cataclysm it is for creatures to reject their Creator.

Groaning in Hope

But when “the creation was subjected to futility,” the one who subjected it did so “in hope” (Romans 8:20). What hope? The hope “that the creation itself will be set free from its bondage to corruption and obtain the freedom of the glory of the children of God” (Romans 8:21). The futility infecting creation is not ultimately futile. It points to a coming liberation.

The harbinger of that liberation occurred when the Creator suddenly stepped into creation, groaned with and entered into its horrific suffering, and in the place of such rebels as us, bore the full brunt of the Father’s righteous judgment “to the point of death, even death on a cross” (Philippians 2:8). And then rose from the dead; “the firstborn of all creation” (Colossians 1:15) became the firstborn of the new creation, “that in everything he might be preeminent” (Colossians 1:18).

It is not only the redeemed children of God who will experience resurrection to new life. God has promised to make “all things new” (Revelation 21:5). Which means the whole creation will experience a kind of resurrection, a newness of life free of corruption.

Free from blaring ambulances and silenced songbirds and murdered men and deadly pandemics and child abuse and dying reefs and senseless violence. These things, as unbearably horrible as they are, as much as they cause creation and the children of God in this age to groan, are “the pains of childbirth” (Romans 8:22) as the great Redeemer brings his work to a close and history builds to its great climax.

Eager Longing

It really is not Eden I long for when a sublime spring morning in Minnesota takes my breath away. It stirs in me the sweet longing, as C.S. Lewis said, “to find the place where all the beauty came from” (Till We Have Faces, 86). The glory in creation I see makes me long, “with unveiled face,” to “[behold] the glory of the Lord,” the Creator (2 Corinthians 3:18).

The profound brokenness of the world is not the way it should be. It is cursed. But it is not cursed forever. It will not always be broken. It will become, at the word of the Creator, another world, a renewed world. And so, “the creation waits with eager longing for the revealing of the sons of God” (Romans 8:19). And the sons of God eagerly long for the creation’s liberation.

Is this all just a fool’s fantasy? There is an empty tomb bearing witness that life has great meaning, that all sickness for God’s children will find its cure, that all calamities will meet their end, that all injustice shall be put right, that our sin-debts have been fully paid and our depravity will be eradicated.

And our sweet, deep, and groaning longings? Again, in the words of C.S. Lewis, “If I find in myself a desire which no experience in this world can satisfy, the most probable explanation is that I was made for another world” (Mere Christianity, 181). Although we cannot see everything now, we hope for what we cannot see and wait for it with patience (Romans 8:24–25).

May 28, 2020

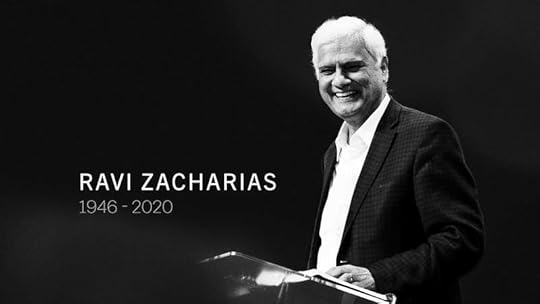

From Chaos to Christ: Gratitude for Ravi Zacharias (1946–2020)

Countless thousands of us around the world, with tearful gratitude, are saying our earthly goodbyes to Ravi Zacharias, who passed away on May 19 after being diagnosed with cancer just a couple of months ago. Someone whose life enriches ours is worthy of honor — and, if he enriched us through faithfully laboring in preaching and teaching, double honor (1 Timothy 5:17). Ravi enriched mine.

I benefited from a number of Ravi’s books and many of his recorded messages. But what stands out most in my memory is reading Can Man Live Without God at a crucial time in my life nearly 25 years ago. I don’t know that I’ve read or heard a public intellectual more fluent and incisive regarding the history of Western philosophy and its consequences — at times horrifically brutal — on Western civilization, especially in the twentieth century. And this from someone born and raised in the East (India).

Ravi ruthlessly described the psychological and social ramifications of atheism’s existential meaninglessness and moral bankruptcy. If God doesn’t exist, the inescapable human need to make sense of the world has no foundation; it’s a castle in the air. If God doesn’t exist, we have no objective basis for our inescapable, deeply intuitive sense of good and evil; it’s a human construct projected onto an amoral reality, perhaps an adaptation favored by natural selection to advance our genes into future generations. Nothing more.

Once man realizes he has no inherent meaning and there are no objective morals — that he must create both himself — and once the restraining vestiges of theism have been removed, terrible consequences will follow. Chilling consequences like the Nietzschean superman madness of the Third Reich and the Marxian utopic madness of Soviet and Sino Communism and their unprecedented carnage. Or on the individual level, consequences like the violence and suicide that result from nihilism and existential despair.

Such despair was not theoretical for Ravi. At 17, seeing no hope for his future, he attempted suicide at his family’s home in Delhi. That proved to be the turning point. For Jesus, as he does for so many of his disciples, came to Ravi at his lowest point and gave him a future and a hope. A Youth for Christ worker visited him in the hospital and left him with this text: “Because I live, you also will live” (John 14:19). In these written words, Ravi heard his living Lord speak, and this previously unremarkable teen made a remarkable resolution: “I will leave no stone unturned in my pursuit of truth.”

For more than half a century, Ravi not only relentlessly pursued the Truth (John 14:6), but relentlessly taught and defended the truth all over the world. The good fruit of his labors can be seen in the legacy of Ravi Zacharias International Ministries (RZIM), the Oxford Centre for Christian Apologetics, Wellspring International (humanitarian aid), 28 books, and the list could go on and on.

All this is the harvest of a seed sown in a Delhi hospital bed after a failed suicide attempt. I would say the seed fell into good soil, though only Jesus would have known it at the time. One thing Ravi knew: he could not live without God. He spoke from his own experience when he wrote,

When man lives apart from God, chaos is the norm. When man lives with God, as revealed in the incarnation of Jesus Christ, the hungers of the mind and heart find their fulfillment. For in Christ we find coherence and consolation as he reveals to us, in the most verifiable terms of truth and experience, the nature of man, the nature of reality, the nature of history, the nature of our destiny, and the nature of suffering. (Can Man Live Without God, 179)

I have one more reason to be grateful for the life and ministry of Ravi Zacharias: Michael Ramsden. Michael was installed last year as president of RZIM, succeeding Ravi. But prior to that, he led RZIM’s European outreach for many years. In the early 2000s, Michael graciously served on the board of Desiring God’s short-lived European arm, and he became a personal friend. More important than being perhaps the most brilliant person I have ever met, Michael is also among the most faith-filled, sincere, and humble people I have ever met. Ravi has handed this baton to another laborer worthy of double honor.

Father, thank you for the life of Ravi Zacharias. Thank you for showing him that he could not live without you. And when all he believed was that he could not live, thank you for showing him you. Thank you for his faithful and fruitful pursuit of stone-turning for the truth and for his double-honor-worthy labors in preaching and teaching and evangelizing and contending for the truth. Thank you that, in the words of Ajith Fernando, in “an era that has heralded the demise of reliance on objective truth as the primary source of direction to the lives of individuals,” Ravi showed “that a ministry committed to demonstrating the validity of objective truth is still relevant and desperately needed.”

Thank you for hundreds and hundreds of thousands of souls, like mine, that you have enriched and strengthened through Ravi. Thank you that he finished his course, kept the faith, left a legacy of financial and moral integrity, and enjoyed a strong marriage of 48 years. And thank you for the next generation of leaders in the RZIM family of ministries, who are taking the helm and leading in the same spirit and by the same Spirit. Give them a double portion of Ravi’s anointing. I have no doubt he would join me in saying, in Jesus’s name, amen.

May 25, 2020

What Billions Say in Silence: The Deafening Sermons of the Stars

“When I look at the stars, I see someone else.” (Switchfoot)

When David looked up in the Near Eastern night sky 3,000 years ago, what he saw almost took his breath away. And in an attempt to express the wonder that flooded him as he contemplated his minuteness in view of such vastness, and God’s design in it all, he did something uniquely human: he transposed his awe into art.

When I look at your heavens, the work of your fingers, the moon and the stars, which you have set in place, what is man that you are mindful of him, and the son of man that you care for him? (Psalm 8:3–4)

The “heavens,” that mysterious realm of marvelous lights, have astonished mankind from our earliest days. When we look at the heavens today, our understanding of what we see, due to advances in science and technology, far exceeds David’s understanding. David only had a hint of how minute he was in relation to the heavens. Our fuel for awe is astronomically greater. We know more, but do we marvel more?

Silent Sermons of the Stars

The starlit sky is speaking. In Psalm 19, which C.S. Lewis considered “one of the greatest lyrics in the world” (Reflections on the Psalms), David again wrote,

The heavens declare the glory of God,

and the sky above proclaims his handiwork.

Day to day pours out speech,

and night to night reveals knowledge.

There is no speech, nor are there words,

whose voice is not heard.

Their voice goes out through all the earth,

and their words to the end of the world. (Psalm 19:1–4)

If the heavens are the work of God’s “hands,” and if they are declaring the glory of God, what are these silent preachers telling us? To listen closely, I have leaned on David Blatner’s book, Spectrums: Our Mind-Boggling Universe from Infinitesimal to Infinity to help capture the wonder of what we too often take for granted.

All That We (Do Not) Know

When David surveyed the sky, part of what he saw belonged to our solar system (sun, moon, and a couple “stars” that were really planets), part belonged to our Milky Way galaxy, and part were distant stars and (probably) other faraway galaxies. David would have barely had a clue how massive and distant these heavenly bodies were.

To give us some perspective, Blatner writes, “if our solar system . . . were the size of a grain of salt, the Milky Way galaxy would be about the length of a football field.” That “milky” stripe we can see on a clear, dark night is a dense collection of stars in one of the Milky Way’s spiral arms — and it’s about 1,000 light-years thick! And what these starry arms (and we with them) are spiraling around is a supermassive black hole, called Sagittarius A, located about 27,000 light-years from us. Scientists estimate that our galaxy is about 100,000 light-years wide.

Looking at the sky with the naked eye, as David did, we can see a few thousand stars at most. But, “look through the telescope, do the math, and you’ll find there are somewhere between 200 and 400 billion stars in the Milky Way.” That’s a lot of stars! But our neighboring galaxy Andromeda appears to contain a trillion or more stars.

And that’s not even a chip on the tip of the cosmic iceberg. A recent estimate of the total number of galaxies in the universe is 150 to 200 billion, but the Hubble Telescope is indicating that the real number might be ten times that amount. And when it comes to the total number of stars, we really don’t know. One estimate is around 1 septillion (that’s a “1” followed by 24 zeros). And all this inhabits a universe that has an estimated radius of about 46 billion light-years.

All this information doesn’t begin to scratch the surface of what we as a species collectively now know. And scientists say that what we now know barely scratches the surface of what we don’t yet know.

What Are the Heavens Declaring?

So, if these heavens declare the glory of God, what are they declaring?

Having spent hours pouring over scientific expositions of the silent sermons of the starry hosts, I first want to put my hand over my mouth. I want to say with Job that far too often “I have uttered what I did not understand, things too wonderful for me, which I did not know” (Job 42:3). I fear trivializing what is ineffably profound.

These glory heralds don’t have three points and an application. They join all who in the presence of God cry “Glory!” (Psalm 29:9); they join all who in the presence of God cry, “Holy, holy, holy, is the Lord God Almighty, who was and is and is to come” (Revelation 4:8). And it seems to me that worshipful prayer is the only appropriate response.

Praying Through the Heavens

Lord God Almighty, when I look to your heavens, I join the choir in ascribing to you absolute glory. And I echo David in saying, “What is man, who occupies this pale blue dot, a dust mote in the vast heavens, that you are mindful of him? And who am I, a man so often consumed with the tiny microcosm of my own concerns, to speak of you who speaks this whole cosmos into being? Indeed, ‘there is none like you’” (Psalm 86:8).

When I look to your heavens, I hear them declare that there is none like you possessing such wisdom. For you, Lord, “by understanding . . . established the heavens” (Proverbs 3:19), “determin[ing] the number of the stars [and giving] to all of them their names” (Psalm 147:4), and conferring upon each one unique aspects of your glory (1 Corinthians 15:41). And they declare that your wisdom is infinitely greater than ours: “For as the heavens are higher than the earth, so are my ways higher than your ways and my thoughts than your thoughts” (Isaiah 55:9). In view of such wisdom, I repent of all my foolish leaning on my own understanding (Proverbs 3:5).

When I look to your heavens, I hear them declare that there is none like you who possesses such power. For “by the word of the Lord the heavens were made, and by the breath of his mouth all their host” (Psalm 33:6). For it is you alone “who brings out [this] host by number, calling them all by name; by the greatness of [your] might and because [you are] strong in power, not one is missing” (Isaiah 40:26). Yes, “yours, O Lord, is the greatness and the power and the glory and the victory and the majesty, for all that is in the heavens and in the earth is yours. . . and you are exalted as head above all” (1 Chronicles 29:11). In view of such omnipotence, I repent of all my foolish trust in the strength of man (Psalm 118:8).

When I look to your heavens, I hear them declare your sheer immensity, since even “the highest heaven cannot contain you” (1 Kings 8:27). And they declare your incomparable creativity, since “the universe was created by [your] word, so that what is seen was not made out of things that are visible” (Hebrews 11:3). And they declare your supreme authority, since “all things were made through [you], and without [you] was not any thing made that was made” (John 1:3). And they declare your sovereignty (Psalm 115:3), your righteousness (Psalm 50:6), your faithfulness (Genesis 15:5–6), and your steadfast love (Psalm 136:9). In view of such glory, I repent of my foolish, selfish pride and bow my knee and confess with my tongue that Jesus Christ, the Word through whom the cosmos was created (John 1:3) and the Word made flesh (John 1:14), “is Lord, to the glory of God the Father” (Philippians 2:10–11).

More Valuable Than Galaxies

When David looked up at the heavens, he did not know what we now know: the unfathomable extent and scope of the universe. And when he asked, “What is man that you are mindful of him, and the son of man that you care for him?” (Psalm 8:4), he did not know what we now know: the unfathomable extent and scope of God’s care for us in sending the incarnate Jesus “to be the propitiation for our sins” (1 John 4:10).

The heavens will not tell us that Jesus came or why. Only Scripture’s special revelation tells us that. But the heavens do declare in a silent shout, literally around the whole world, glorious things about our Creator’s and Savior’s “eternal power and divine nature” (Romans 1:20).

All that is involved in creation and all that is involved in redemption is nothing less than fearful and wonderful. The deeper we look into these things, the more fearful and wonderful it all becomes. A child can take joy in the sun, the moon, the stars, and the empty tomb. And scholars will never plumb the full depths of such glorious things.

But children and scholars alike can take comfort in this: the God who remembers the names of a sextillion stars, and knows all sextillion molecules in a drop of water, knows and remembers us.

God does not measure value or significance in size, but in his creative design. The cross reminds us that he is mindful of us in ways that galaxies will never know. Of how much more value are you than they?

May 20, 2020

God Made You for a Body: How Resurrection Will Make Us Whole

What comes to your mind when you think about your soul? How does it relate to your body? Do you have a spirit that is in some way different from your soul? Are your body, soul, and spirit just one inseparable unit? What happens to these dimensions of you when you die? And what happens at the resurrection?

Christians have debated these questions throughout history. This is partly because the Bible can sound like it’s saying different things about the body, soul, and spirit in different places, and partly (particularly for western Christians) because of Plato’s influence on our thinking. Today, we also have the additional influence of the discoveries in neuroscience.

But the majority of Christian theologians throughout history have agreed that the Bible reveals human beings as fundamentally comprised, as the Athanasian Creed puts it, of a “rational soul and flesh,” meaning two main dimensions: an immaterial and a material.

These two dimensions were not designed to be torn apart, but due to sin and its wages (Romans 6:23) the tragic abnormality is that they are torn apart in death. And therefore, the ultimate goal of what Jesus purchased on the cross, and the great hope of the Christian faith, is not disembodied souls living in an ethereal heaven after bodily death, but the resurrection of the body.

The Great Divide

God created us as embodied souls and designed these two dimensions to function in complete harmony. But then came the fall, and “sin came into the world through one man, and death through sin, and so death spread to all men because all sinned” (Romans 5:12). And when death occurs, the Bible describes our soul being torn from our body.

Not all Christians affirm such cleaving. There are a minority of theologians who hold to monism, the belief that a human is one inseparable being, that no aspect of a person can live apart from his body, and that “the scriptural terms soul and spirit are just other expressions for the “person” himself, or for the person’s “life.” Monists believe that when people die, they undergo a kind of soul sleep until the resurrection, pointing to numerous texts like John 11:11 and 1 Corinthians 15:20, where death is described as sleep.

But there’s a reason the vast majority of Christians have not been monists: so many texts point to our soul (or spirit) living on after death claims our bodies (Genesis 35:18; Psalm 31:5; Luke 23:43, 46; Acts 7:59; Philippians 1:23–24; 2 Corinthians 5:8; 1 Thessalonians 4:14; Hebrews 12:23; Revelation 6:9; 20:4). Therefore, “sleep” is a euphemism for what happens to the body, not the soul.

The Intermediate State

One of the clearest Scriptures on this is Jesus’s parable of the rich man and Lazarus (Luke 16:19–31). In the story, both poor Lazarus and the rich man die. Their souls are torn from their bodies and sent to “Hades,” the realm of the dead, where Lazarus is at Abraham’s side, across the chasm from where the rich man is in torment. Jesus may have employed fiction in his parables, but he always used realistic fiction. If this parable didn’t in some significant way reflect what really happened after death (until Christ himself went in human soul to Hades, and drew up with him saved souls to his Father’s presence in heaven), it would have been a strange anomaly and uncharacteristically misleading.

Theologians refer to the place where Lazarus’s and the rich man’s soul go (with a great chasm fixed between them, Luke 16:26) as the “intermediate state,” where souls of those who have died await the resurrection of the dead and the final judgment (John 5:28–29). For those who die in their sin (John 8:24), it is literally a hellish state of torment. But for those who die in faith, it is wonderful beyond imagination, what we call “heavenly,” because it is where God is. That’s why Jesus said to the thief on the cross, “today you will be with me in paradise” (Luke 23:43). And it’s why Paul said that to “be away from the body [is to be] at home with the Lord” (2 Corinthians 5:8), which is “far better” (Philippians 1:23) than remaining in a fallen “body of death” (Romans 7:24).

But while this temporary paradise is far better for the Christian than this futile world, the Bible does not describe it as being the best thing. There is some sense in which our souls will be “unclothed” at the loss of our physical bodies (2 Corinthians 5:4), though the Bible doesn’t describe it in specifics. It may be a heavenly experience for us to be with the Lord, but we will be incomplete until we “attain the resurrection from the dead” (Philippians 3:11).

Your Spiritual Body

Christianity is not merely a go-to-heaven-when-you-die religion; Christianity is foremost a resurrection religion. The cross of Jesus is of course crucial. But it is the resurrection of Jesus that not only points to his death’s efficacious substitutionary atonement for our sins (1 Corinthians 15:17–19), but also points to our ultimate future hope: our resurrection (1 Corinthians 15:20).

When Jesus came, it was to inaugurate the new creation. The current creation is groaning under the weight of “futility” and its “bondage to corruption,” eagerly waiting for “the revealing of the sons of God” (Romans 8:19–21). And the sons of God will be revealed when they experience the “redemption of [their] bodies,” meaning their new bodies (Romans 8:23). And this will happen at the return of Jesus, the great Christian “blessed hope” (Titus 2:13), which will initiate that great gathering in the clouds (1 Thessalonians 4:15–17). The entire New Testament rings with resurrection.

God is not content to give us an ethereal heaven where we’ll live as a great gathering of disembodied souls. God originally made this creation “very good” (Genesis 1:31). But since it has been corrupted by sin, he now intends to make “all things new” (Revelation 21:5). And a central part of this new creation is the reunion of our purified souls with our new resurrected bodies:

What is sown is perishable; what is raised is imperishable. It is sown in dishonor; it is raised in glory. It is sown in weakness; it is raised in power. It is sown a natural body; it is raised a spiritual body. (1 Corinthians 15:42–44)

The Great Reunion

God is giving his Son, Jesus, a kingdom of a new heavens and new earth (Isaiah 65:17; 2 Peter 3:13), and all who have been adopted as sons in Jesus (Ephesians 1:5) will reign with him, all having shared in his resurrection (Revelation 20:6). For, in our case, the last enemy Jesus will destroy is death (1 Corinthians 15:26).

Behold! I tell you a mystery. We shall not all sleep, but we shall all be changed, in a moment, in the twinkling of an eye, at the last trumpet. For the trumpet will sound, and the dead will be raised imperishable, and we shall be changed. For this perishable body must put on the imperishable, and this mortal body must put on immortality. When the perishable puts on the imperishable, and the mortal puts on immortality, then shall come to pass the saying that is written:

“Death is swallowed up in victory.”

“O death, where is your victory?

O death, where is your sting?” (1 Corinthians 15:51–55)

And so the great divide between our immaterial soul and our material body that happens at our curse-caused death will become, in the resurrection, the great reunion of our soul and body — a glorious body that, like Jesus’s, “will never die again” (Romans 6:9).

And of all the glorious things we will experience in our resurrected, reunified state as inhabitants of God’s new creation, the joy of our joys, our light of our new life, the heaven of the new earth, will be this: that “we will always be with the Lord” (1 Thessalonians 4:17).

May 16, 2020

‘My Soul Refuses to Be Comforted’: A Song for Long Nights in Darkness

His soul was in such turmoil he could not sleep. So confused and disturbed were his emotions (and the questions that fueled them), he couldn’t capture them all in words. He wasn’t experiencing a generalized, undefined depression. He mentioned no specific enemy threatening his life. The person he was in anguish over was God. When Asaph penned Psalm 77, he was experiencing a crisis of faith.

I cry aloud to God,

aloud to God, and he will hear me.

In the day of my trouble I seek the Lord;

in the night my hand is stretched out without wearying;

my soul refuses to be comforted.

When I remember God, I moan;

when I meditate, my spirit faints. Selah

You hold my eyelids open;

I am so troubled that I cannot speak. (Psalm 77:1–4)

Why was Asaph so troubled? Because from his perspective it appeared God had decided to abandon his promises to Israel. And if God doesn’t keep his word, those who trust in him build the house of their faith on the sand — a very disturbing thought.

You Hold My Eyelids Open

Many who have endured a faith crisis recognize the experience Asaph describes. Something happens that shakes our confidence in what God has said, causing us to waver over what we’ve understood to be true about him or his character. This uncertainty produces anxiety and fear. In an effort to quell our anxiety, our mind becomes an incessant investigator, diligently searching for answers that will restore our confidence (Psalm 77:6).

Such anxiety can rob us of sleep. It did for Asaph. During the day, other responsibilities, activities, and people require our attention, offering some distracting respite. But in the dead of night, it’s just us and our troubled thoughts. So we lie awake in bed or pace a dark room with our figurative (or literal) “hand . . . stretched out [toward God] without wearying,” and our “soul refus[ing] to be comforted” (Psalm 77:2).

Refusing to be comforted? Is that okay? Asaph’s example here doesn’t endorse every inconsolable moment we have. We all battle sinful unbelief. But this psalm, I believe, is not a clinic in sinful unbelief, but in honest, anguished spiritual wrestling. There can come desperate moments in life — and we’ll see shortly just how desperate Asaph’s moment was — where telling our turmoil-afflicted soul to “hope in God” (Psalm 43:5) doesn’t bring quick comfort, because at that moment we’re wondering if God can be hoped in. This is why Asaph says, “When I remember God, I moan; when I meditate, my spirit faints” (Psalm 77:3).

Before we go on, we simply need to let this sink in: Asaph’s faith in God was shaken, the resulting anxiety was keeping him awake at night (he even told God, “You hold my eyelids open”), and this experience made it into the canon of Scripture. There’s a reason God preserved this psalm for us.

Has God Forgotten to Be Gracious?

Psalm 77 doesn’t tell us what was fueling Asaph’s distress. But Psalm 79, also attributed to Asaph, very likely does:

O God, the nations have come into your inheritance;

they have defiled your holy temple;

they have laid Jerusalem in ruins.

They have given the bodies of your servants

to the birds of the heavens for food,

the flesh of your faithful to the beasts of the earth.

They have poured out their blood like water

all around Jerusalem,

and there was no one to bury them.

We have become a taunt to our neighbors,

mocked and derided by those around us. (Psalm 79:1–4)

Asaph had witnessed horrors, even if he speaks of them in poetic language. Many of us have seen gruesomely prosaic photographs of war — of brutalized corpses of men, women, and children rotting in the streets. Those who have actually seen the violence, walked those streets, and personally known some of the slain are often scarred by such trauma for a lifetime.

Asaph knew God’s judgment (most likely the Babylonian conquest of Judah) had fallen upon the nation due to unfaithfulness (Psalm 79:8). But the experience of it, described even more graphically by the author of Lamentations, was overwhelmingly horrific on every level. It didn’t just look like judgment; it looked like wholesale abandonment. So, in his midnight anguish, Asaph was asking,

Will the Lord spurn forever,

and never again be favorable?

Has his steadfast love forever ceased?

Are his promises at an end for all time?

Has God forgotten to be gracious?

Has he in anger shut up his compassion? (Psalm 77:7–9)

He was asking these disturbing questions because, from his vantage point, at that moment, the answer to each of them had every appearance and emotional impact of yes.

I Will Appeal to This

But Asaph knew his Bible. He knew the covenants God had made with Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, and David. He knew Israel’s history, from Abraham’s sojourning to the Egyptian slavery to the exodus to the Mosaic law to the conquest of the Promised Land to the reign of kings. He knew the holiness and power God had manifested (Psalm 77:13–14).

And so, in the midst of his disorientation and disillusionment and fear, having witnessed traumatic devastation of God’s people and God’s land, Asaph looked backward for hope:

Then I said, “I will appeal to this,

to the years of the right hand of the Most High.”

I will remember the deeds of the Lord;

yes, I will remember your wonders of old.

I will ponder all your work,

and meditate on your mighty deeds. (Psalm 77:10–12)

In particular, he focused his troubled mind on the crossing of the Red Sea, reminding himself of how, at that desperate moment, when by all appearances it had looked like Egypt would wipe Israel out and the covenants would fail, God had “redeemed [his] people, the children of Jacob and Joseph” (Psalm 77:15).

When the waters saw you, O God,

when the waters saw you, they were afraid;

indeed, the deep trembled. . . .

Your way was through the sea,

your path through the great waters;

yet your footprints were unseen.

You led your people like a flock

by the hand of Moses and Aaron. (Psalm 77:16, 19–20)

In his crisis of faith, Asaph reminded himself how, repeatedly through history, those who hope in God have had to hope against hope (Romans 4:18) that God would keep his promises despite circumstances appearing hopeless. If we read Asaph’s psalms (Psalms 73–83), we’ll see how many times he had to remember God’s faithfulness in the past to keep his faith in God’s promised future grace from failing in the present — or in his words, to keep his foot from slipping (Psalm 73:2).

Hope When Circumstances Are Unchanged

Psalm 77 was birthed during an anguished, sleep-deprived night. And it has no explicit resolution; no pretty bow of hopeful words to wrap it up. It just ends, “You led your people like a flock by the hand of Moses and Aaron” (Psalm 77:20). However, the hope is implicit: God, as horrible as this looks right now, as much as it appears that you have forgotten to be gracious, redemptive history tells me that you will still keep your promises and bring your deliverance.

That is one reason God has preserved this psalm and this experience: to help us if and when our faith undergoes severe testing. Asaph provides us language for lament, and an example of what to do when anxiety is surging, and by all appearances it looks like God’s “promises [may be] at an end for all time” (Psalm 77:8).

Like Asaph, our horrible moment might make it appear like God isn’t being or won’t be faithful to his promises, fueling sleepless nights of anxious praying and pondering. Like Asaph, we can pour out our heart to God with profound candor during such a moment. Like Asaph, we can remember God’s faithfulness in the past to keep our faith in God’s future grace from failing in the present.

And like Asaph, we might not quickly receive the comfort we long for, but we fight for it with all our might.

April 16, 2020

When a Pandemic Falls on the Poor: Desperate Needs in the Global Church

For related teaching, see our Coronavirus resource collection.

When I was a 20-year-old serving with Youth With A Mission in an impoverished section of an immense Asian city, I grew close to a Christian family that lived near our base house. These dear friends still live in that same neighborhood, and we’ve managed to stay in contact for 35 years.

Life for my friends has always been extraordinarily hard by Western standards. Now, the coronavirus pandemic that’s prompted a lockdown in their nation has made life extraordinarily hard by their standards. They can’t work. Which means no money. Which means no food, no medicine — nothing. Those in their network of relationships, including their church, share the same level of poverty, so there’s very little to go around. And there’s no government relief payment coming their way. We are seeking to help them, but their network of extended family and friends is so big that our help feels like five loaves and two fish. We are praying our Lord multiplies it.

My friends represent hundreds and hundreds of millions of precious souls who live in areas of the world where the pandemic is forcing them into impossible situations. Many millions of these souls are Christians.

In this global emergency, God is once again issuing a call to Christians everywhere, with any amount of means to help, to “remember the poor” (Galatians 2:10).

Remember the Poor

When Paul and Barnabas went to Jerusalem to make sure the gospel they were preaching to the Gentiles had the approval of the church’s “pillars” — including James, Peter, and John — they received, along with the official blessing, the request to “only . . . remember the poor” (Galatians 2:9–10).

Many scholars believe that “the poor” in this text refers specifically to impoverished Christians living in Judea — those whose dire situation Paul sought to help relieve through the financial collections he gathered from Gentile churches (Romans 15:25–26; 1 Corinthians 16:1–3). But if so, this directive certainly would not have been exclusive to the Christian poor in Judea, even if they were the most sizable and notable of the world’s Christian poor at the time.

Rather, this call demonstrates that right from the beginning, the entire Christian church was instructed to be mindful of, and feel some measure of responsibility for, the plight of other Christians, however geographically and culturally remote they might be. And from Jesus’s own example, we know that Christians’ concern for the poor also extends beyond the church’s boundaries into the unbelieving world.

From Riches to Rags

The incarnation of God the Son is a massively influential, church-shaping, Christian-forming example of God’s heart to bring relief to the poor. In fact, Paul pointed to this example when raising funds for the Judean poor: “You know the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ, that though he was rich, yet for your sake he became poor, so that you by his poverty might become rich” (2 Corinthians 8:9). Paul’s words highlight two realities: First, before God we all are extremely spiritually poor and needy, and God moved to meet our deepest need. Second, Jesus’s willingness to “empty himself” (Philippians 2:7), identify with our poverty, and address our greatest needs models how we should move to meet the profound spiritual and material needs of believers and unbelievers.

Think of Jesus’s entire life. He was born and raised in a poor family. During his years as a public figure, he and his disciples refused to monetize their ministry (Matthew 10:8), living off the charitable gifts of supporters (Luke 8:3). He taught that those who are “poor” (Luke 6:20), and “poor in spirit” (Matthew 5:3), are “blessed” since “theirs is the kingdom of heaven.” And he healed, delivered, and performed miracles for those who were destitute, afflicted, and across-the-spectrum needy.

Jesus also regularly gave to the poor. We know this because, during the Last Supper, when Jesus told Judas, “What you are going to do, do quickly,” the other disciples assumed Judas, who kept the moneybag, might be going to “give something to the poor” (John 13:27–29). The disciples would have assumed this only if such giving were not unusual.

The Church’s Care for the Poor

The church’s early days show that the example of Jesus’s remembering the poor had taken root in the apostles’ lives and shaped the church’s culture. We see it in these famous verses:

All who believed were together and had all things in common. And they were selling their possessions and belongings and distributing the proceeds to all, as any had need. (Acts 2:44–45)

Out of the mass conversions emerged a new community of Christians, and with it all kinds of needs. Many were likely already poor when they converted, and others could have found themselves suddenly facing financial hardship when following Jesus cost them the support of family or other sources of income. Whatever the causes, the church quickly mobilized to meet these needs so that “there was not a needy person among them” (Acts 4:34).

The controversy regarding the neglect of the Hellenistic widows in Acts 6:1–6 gives us a helpful picture of how they approached this. Without neglecting the “preaching [of] the word of God,” those early Christians created new social structures and systems to meet people’s basic needs and make sure the poor were remembered.

Christian history is replete with examples of Christians serving the poor and the sick (yes, with some glaring failures too). The sheer number of individuals, churches, and Christian charities rushing to the front lines of crises and chronic troubles to meet both Christians’ and non-Christians’ needs demonstrates that what Jesus and the apostles modeled and taught continues to live on in the living church around the world. Millions of Christians continue to “remember the poor.”

Remembering Reveals Our Treasure

Now, as the coronavirus pandemic builds steam, particularly in the Global South, where countries have nowhere near the wealth and infrastructures of the more industrialized nations, God is calling us Christians again to remember the poor — all those in need, with a particular responsibility for poor believers.

This crisis is not like a famine or tsunami or hurricane, or even like HIV/AIDS or Ebola. It is a global health crisis with a global economic crisis on top of it — and the latter crisis may cost more lives than the former in the poorest nations. And these crises are unlike the regionally contained crises that occur in far-flung places in the world, because we are now being called to remember the poor while dealing with various consequences of the crises ourselves. Which means this is a time of real treasure-testing for us. Where is our treasure stored up? Where is our heart (Matthew 6:19–21)?

This is a time to remember the poor. It’s part of what it means to be a Christian. This is our calling and our joy. We must remember the poor among us, those in our local churches who have been furloughed or laid off and find themselves in sudden financial or some other need. We must remember the poor in our cities or regions that are particularly vulnerable. And we must remember the poor in impoverished countries who are at the greatest risk on the greatest scale. These needs are overwhelming, but we cannot allow ourselves to shut down due to the staggering size of the needs, and retreat to Netflix, while they perish.

You’ll notice a conspicuous lack of specific recommendations for where to give and what to do. That’s because we each have unique situations, unique needs right in front of us, and unique prompts from God regarding where he wants us to give and serve. But also, our Lord tends to use our prayerful discernment and research to help us more fully engage in our acts of remembering. And the more engaged we are, the more likely we will see and feel the treasure that has our hearts.

Generosity Born from Affliction

As I was finishing this article, I received a message from my dear friend in that impoverished region of that immense city on the other side of the world. And as I read, I was humbled.

She confessed the sin of losing her temper with someone. (Knowing the very stressful and grievous nature of that situation, my response likely would have been worse.) She also shared her deep trust in Jesus to provide for their needs. And she told me of opportunities she’s had to pray with neighbors and share words of gospel hope with them, and that she’s been trying to meet the material needs of others around her who also are in a desperate place. Like the ancient Macedonians, “in a severe test of affliction, [her] abundance of joy and [her] extreme poverty have overflowed in a wealth of generosity on [her] part” (2 Corinthians 8:2).

She is carrying on the great tradition of her Lord and centuries of Christian witness. If she can remember the poor, so can I. So can we all.

April 15, 2020

Don’t Wait to Be Done with Sin: What Mercy Says in Calamity

When they told Jesus about the horror that had happened, his response caught them completely off guard.

Pontius Pilate, from what we know from the Gospels and the Jewish historian Josephus, was a politically and morally pragmatic Roman governor willing to employ humiliation and brutality when he wanted to exert imperial authority over a fomenting rebellion. He did both when he ordered the assassination of some Galilean Jews while they were offering sacrifices in the temple according to the law of Moses.

We aren’t told the historical reason behind the killings. Perhaps these particular Galileans had engaged in some seditious act against Rome, or perhaps they happened to be in the right place at the wrong time when Pilate decided to send a general message of terror to the agitating Jewish people. What we are told is that Pilate had the Galileans’ “blood . . . mingled with their sacrifices.” This added the insult of religious defilement to the horror of the murders, ensuring that whatever message he was sending would spread throughout Palestine with the speed of fear and outrage (Luke 13:1).

We’re also told that when Jesus received the news, he completely ignored whatever message Pilate was sending. And his answer to the people’s theological question as to why this happened likely shocked his hearers almost as much as it shocks us today.

Unexpected Message

Jesus’s response was brief and blunt:

Do you think that these Galileans were worse sinners than all the other Galileans, because they suffered in this way? No, I tell you; but unless you repent, you will all likewise perish. (Luke 13:2–3)

What Jesus didn’t say was shocking. He said nothing about a messianic deliverance of God’s people from the humiliating Roman oppression and the grievous Gentile occupation of the Promised Land. He said nothing about the offense to God’s glory in the temple’s defilement. He said nothing about specific sins the Galileans may have committed to warrant God’s allowing such ignominious deaths — nothing that might allay his hearers’ fears that such a horror could befall them. He didn’t even say anything about forgiving one’s enemies.

What Jesus did say was even more shocking: the Galileans’ tragedy should lead his hearers to repent before God. The fact that they were still alive was owing not to their goodness, but to God’s mercy.

Before these hearers had time to formulate questions or objections, Jesus drove his point home with a different example:

Or those eighteen on whom the tower in Siloam fell and killed them: do you think that they were worse offenders than all the others who lived in Jerusalem? No, I tell you; but unless you repent, you will all likewise perish. (Luke 13:4–5)

In both the premeditated murder of the Galileans and in the accidental deaths resulting from the tower’s collapse, Jesus wanted his hearers to hear an urgent message from God: repent.

Why This Suffering?

The people listening to Jesus that day were looking for an answer that all people of all eras look for: Why this suffering? Why this evil, and why did it befall these victims? What can I do to escape from it befalling me?

We know, not only from this text in Luke 13:1–5 but from numerous places in Scripture, that many held to a theology of suffering that drew direct lines from an individual’s specific suffering to a specific sin against God. We hear it in Job’s anguished spiritual wrestlings and centuries later in the disciples’ question about why a man was born blind (John 9:1–3).

The answer Jesus gave accomplished, in one stroke, a number of crucial theological corrections. It removed unwarranted social stigma from victims of such calamities and their families by emphasizing that their guilt wasn’t necessarily worse than anyone else’s. It undercut anyone’s errant belief that their current lack of suffering amounts to God’s endorsement of their righteousness. And most importantly, it revealed the sin-guilt of every person before God.

‘Unless You Repent’

That last point was Jesus’s main point, the urgent message he wanted the people to hear in the headline-news tragedies of the day. Whether perishing came through the agency of evil human volition (Pilate), or the various effects of futility-infused creation (falling tower), or, as he would address just a few verses later, the effects of evil spiritual oppression (Luke 13:10–17) — for Jesus, the primary issue was the perishing itself, not its agent. The primary issue wasn’t how people died, but that people died, and death’s eternal ramifications.

That’s the problem Jesus had come to address. The collective human problem is that “all we like sheep have gone astray; we have turned — every one — to his own way,” and Jesus had come to have “the iniquity of us all” laid on him (Isaiah 53:6). The wages of our sin is a death far more profound than the ceasing of life in our bodies, and Jesus had come to provide us God’s “free gift of . . . eternal life” (Romans 6:23). He hadn’t come to deliver the Jews from Rome’s temporal oppression, but to deliver all people everywhere who would believe in him from eternal perishing, and to give them everlasting life in a Promised Land of which the Israel of this age was but a copy and shadow (John 3:16).

And this is why Jesus responded to the news of the Galileans’ deaths with the shocking words “unless you repent, you will all likewise perish.” It may sound harsh. But there are moments when seemingly harsh words are great mercies, as every parent of a young child about to dash into the street knows.

Jesus’s hearers didn’t need to know the specific guilt of the Galileans or Pilate’s political motivations or any other secondary issue. They needed to know that if they still had breath, the offer of forgiveness for sin and escape from terrible perishing was still offered to them — if they would repent.

And the same is true for us today.

Judge with Right Judgment

Jesus is not simplistic when it comes to the agonies of human suffering. Reading through the Gospels, we see that “repent” is not the only way he responds to our afflictions. He responded with manifest compassion and kindness to many, such as a mother about to bury her son (Luke 7:11–15), a leper who longed for healing (Matthew 8:1–4), and a man paralyzed for thirty-eight years who thought he’d never walk again (John 5:1–17).

But Jesus said something during the controversy erupting from that last example that we can apply here. Having healed the paralyzed man on the Sabbath, he was rebuked and opposed by the Jewish leaders. His response to them was, “Do not judge by appearances, but judge with right judgment” (John 7:24). In other words, the leaders and observers had not seen the most important reality in the man’s suffering and deliverance: the mercy of God and the offer of repentance (John 5:14).

When we examine our own suffering or someone else’s, we are often tempted to ask why. What did we or they do to deserve this? Or we may try to decipher God’s purposes in a Gordian knot of secondary causes. But this is far above our creaturely pay grade, for God’s purposes are often opposite of our perceptions. Instead, the most helpful truth to hear, and heed, might be Jesus’s words “Do not judge by appearances, but judge with right judgment.”

Headline in Every Tragedy

We are called to respond to the myriad human suffering in the world in many ways. But one takes precedence above them all. As with his original hearers, the urgent message Jesus wants all of us to hear in the headline-news tragedies of our day is “unless you repent, you will all likewise perish.”

These are shocking words to hear in the face of suffering. They catch us off guard, because they are answering a question most people are not asking. But coming from Jesus, especially hearing them this side of the cross, we know they are not the heartless ravings of a hateful prophet. No one loved like Jesus (John 15:13). Rather, they are the mercifully frank diagnosis of the Good Physician, who offers to bear our eternally terminal disease himself if we will repent and receive his free gift of eternally healthy life.

April 6, 2020

Your Strength Will Fail: Why God Gives Us More Than We Can Handle

Paul wrote the letter we know as 2 Corinthians right on the tail end of an experience of severe suffering. Here’s how he described it:

We do not want you to be unaware, brothers, of the affliction we experienced in Asia. For we were so utterly burdened beyond our strength that we despaired of life itself. Indeed, we felt that we had received the sentence of death. (2 Corinthians 1:8–9)

Paul doesn’t specify what his affliction was. He didn’t need to, since the letter’s carrier would have briefed the Corinthian believers on the painful details. From the surrounding context (2 Corinthians 1:3–11), it sounds like he suffered persecution nearly to the point of execution. But in the merciful wisdom of the Holy Spirit, we don’t know for sure. And this is a mercy because it encourages us to apply what Paul says in this section to “any affliction” (2 Corinthians 1:4).

But it’s important that we note the degree of Paul’s suffering. This great saint, who seems to have had a much higher-than-average capacity to endure affliction, felt “so utterly burdened beyond [his] strength.” He thought this affliction would kill him.

It didn’t kill him (his lethal affliction was still eight to ten years in the future). But it did accomplish something else:

Indeed, we felt that we had received the sentence of death. But that was to make us rely not on ourselves but on God who raises the dead. (2 Corinthians 1:9)

Paul’s suffering brought him to the end of himself: not just to the end of his bodily strength, but to the end of his earthly hopes and plans. He was staring death in the face. What could he trust at the end that would give him hope? The God who raises the dead.

God of All Comfort

Knowing the severity of Paul’s suffering and what it produced in him helps us better understand the comfort he testifies to in his opening words:

Blessed be the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, the Father of mercies and God of all comfort, who comforts us in all our affliction, so that we may be able to comfort those who are in any affliction, with the comfort with which we ourselves are comforted by God. (2 Corinthians 1:3–4)

Although we know that Paul was delivered from this particular “deadly peril” (2 Corinthians 1:10), the deliverance from death wasn’t the primary comfort he received from God. Nor was it the primary comfort he wanted to give to others in their affliction. The primary comfort was that at the very end, when death finally approaches, and there is no more hope of prolonging earthly life, there is one, great, death-defying hope for the Christian: the God who raises the dead.

We know that Paul is speaking of the comfort of resurrection hope because he goes on to say, “for as we share abundantly in Christ’s sufferings, so through Christ we share abundantly in comfort too” (2 Corinthians 1:5). Christ suffered death “for the joy that was set before him” (Hebrews 12:2), the comforting joy that he would be raised from the dead, and through him all who believe in him (John 5:24). And he was raised from the dead (1 Corinthians 15:20), and therefore everyone who believes in him shall be as well, even though they die (John 11:25).

Comfort in Any Affliction

But which of our sufferings qualify as sharing in Christ’s sufferings? If the affliction Paul experienced in Asia was indeed persecution, it’s easy to make that connection. But what if our afflictions don’t fall into that category?

I believe the answer lies in Paul’s point that the “God of all comfort . . . comforts us in all our affliction, so that we may be able to comfort those who are in any affliction” (2 Corinthians 1:3–4). All and any are comprehensive words.

We know just from this particular letter that Paul had other kinds of suffering in mind than just persecution. There’s his list of various dangers and deprivations he endured (2 Corinthians 11:25–28), and there’s his “thorn . . . in the flesh” (2 Corinthians 12:7), which I take to be some kind of physical malady or disability.

But the Bible’s category of afflictions extends far wider. Just a sampling would include the affliction and grief of illness and death (like Lazarus in John 11 and Epaphroditus in Philippians 2:25–27), the anguish of what feels like spiritual desertion (Psalm 22), the disillusioning confusion when circumstances appear as if God is not keeping his promise (Psalm 89), the disorientation of undergoing serious doubt (Psalm 73), or the agony of prolonged and dark depression (Psalm 88).

All of these experiences and more are forms of suffering — many of which Jesus himself experienced, and all of which he cares very much about. What makes “all our affliction” a sharing in Christ’s sufferings is that when they befall us, we turn in faith to “him [on whom] we have set our hope” for the deliverance he intends to provide for us (2 Corinthians 1:10).

On Him We Have Set Our Hope

That’s actually one of the most important outcomes that God intends for “all our affliction” to produce: “to make us rely not on ourselves but on God who raises the dead” (2 Corinthians 1:9). It’s not the only outcome. As John Piper says, “God is always doing 10,000 things in your life, and you may be aware of three of them.” But when it comes to our ultimate joy and comfort, few are more important than weaning our trust off ourselves and placing it onto God.

In fact, that’s why sometimes our afflictions come as God’s unexpected answers to our prayers, and therefore at first unrecognized. When we ask God to increase our desire for him and our faith in him and our love for him and our joy in him, we imagine how wonderful the answers would be to experience. But we don’t always anticipate what the process of transforming our desires and trusts and affections and joys will require.

Sometimes, it requires afflictions to reveal ways we rely on ourselves or idols or false hopes instead of God. In and of itself, God does not enjoy afflicting his children (Lamentations 3:33), but when necessary, as a loving Father, he will discipline us (Hebrews 12:7–10). But God’s purposes in such discipline are always for our good, even though at the moment they are painful, because they ultimately produce profound hope and joy (Hebrews 12:11).

This is why Paul, who during his affliction had been “so utterly burdened beyond [his] strength that [he] despaired of life,” ended up exulting in his heavenly Father as the “God of all comfort.” As a result of his suffering, he experienced a more profound reliance on the God who raises the dead, which brought him a comfort that nothing else in the world affords.

Whatever it takes to help us experience this comfort, to help us set our real, ultimate hope on God, is worth it. It really is. I don’t say this lightly. I know some of the painful process of such transformation. I’ve received some of the unexpected answers of God to my prayers. But the comfort God brings infuses all temporal comforts with profound hope. And when all earthly comforts finally fail, it is the one comfort that will remain.

March 26, 2020

When Guilty Men Go Free: The Gospel According to Barabbas

Only a relatively few people are mentioned by name in all four New Testament Gospels. Besides Jesus, of course, there are such notables as his mother Mary, John the Baptist, Mary Magdalene, and Pontius Pilate. Given the roles each of these played in the life of Jesus, their mentions are understandable.

Another name in this somewhat exclusive group may be far more surprising, however: Barabbas.

Barabbas’s inclusion might be all the more unexpected when we think that not even all twelve disciples are cited by name in all four Gospels (John doesn’t catalog them all). Nor is Jesus’s earthly father, Joseph (he’s absent in the Gospel of Mark). Clearly, we must not assume an explicit four-Gospel mention has any necessary correlation to God’s esteem of an individual. But then again, neither should we ignore Barabbas’s presence in all four accounts. The Holy Spirit clearly wants us to take notice of something. He wants us to learn from Barabbas.

Notoriously Offensive

Barabbas is famous for his infamy. He suddenly appeared on the stage of world history at his most ignoble moment. In fact, all we know about Barabbas is that he was a “notorious” criminal (Matthew 27:16).

Mark and Luke report that he had participated in some kind of insurrection in Jerusalem and had committed murder (Mark 15:7; Luke 23:18–19). John just refers to him as “a robber” (John 18:40) — choosing the Greek word lēstēs, connoting one who pillages and loots. In certain contexts, it can also mean “insurrectionist.” But these explicit four-Gospel mentions lead us to believe that Barabbas’s Jewish countrymen likely viewed him more as a thug than a heroic freedom fighter for Israel’s national independence.

The most telling indicator of this is the fact that Pontius Pilate, in his political chess game with the Jewish leaders over whether to free or execute Jesus, gave the crowd a choice between freeing Barabbas or Jesus (Matthew 27:15–18). Piecing the Gospel accounts together, it appears that Pilate thought he could frustrate the Jewish leaders’ desire for Jesus’s death through Rome’s annual act of grace at the Jewish Passover: freeing a condemned prisoner.

Pilate wanted that prisoner to be Jesus. Therefore, if he wanted to give the crowd a choice, he wouldn’t make Jesus compete against a popular hero. He’d want to offer the crowd an alternative to Jesus they would find morally offensive, whose clear guilt would starkly contrast with Jesus’s clear innocence. Surely the crowd wouldn’t choose Barabbas. Pilate was wrong.

‘I Find No Guilt in Him’

The Jewish leaders countered Pilate’s move by coaching the crowd (Matthew 27:20), and to Pilate’s bewilderment, the people chose Barabbas (John 18:40). It did not matter how often Pilate repeated, “I find no guilt in him” (John 18:38; 19:4, 6), all of his attempts to spare Jesus proved vain. And after the Jewish leaders backed him into a corner with a not-so-veiled political threat (John 19:12),

Pilate decided that [the crowd’s] demand should be granted. He released the man who had been thrown into prison for insurrection and murder, for whom they asked, but he delivered Jesus over to their will. (Luke 23:24–25)

The guilty man was pardoned, and the innocent man was condemned to death.

On a human level, this was a great evil. It was terrible evil that Jesus was betrayed by a friend. It was a terrible evil that the Jewish leaders pursued his execution through devious means. It was a terrible evil that Pilate forsook justice, trying to free Jesus on the political sly. It was a terrible evil that the crowd chose to free a man guilty of capital murder over a man guilty of nothing. The murder of Jesus was, as John Piper calls it, “history’s most spectacular sin.”

Barabbas, Melchizedek, and Me

That’s all we know of Barabbas. Just as suddenly as he appears on history’s stage, he disappears. We remember him as the guilty man who received a life-giving pardon because the innocent Son of Man was condemned to death.

In a sense, Barabbas is a little like Melchizedek, the king and priest of ancient Salem who made a sudden appearance for only a few hours in the life of Abraham (Genesis 14:18–20). But his brief appearance became a powerful foreshadow and type of Jesus, our great King and Priest (Psalm 110:4; Hebrews 5:6; 6:20–7:17). Barabbas, who appeared for only a few hours of Jesus’s life, is a different type. He has become a type for all sinners — all of us.

We all have sinned (Romans 3:23); we all stand guilty before God. We all deserve the sentence of eternal death (Romans 6:23). But Barabbas is a gospel parable, and the lesson is this: “God shows his love for us in that while we were still sinners, Christ died for us” (Romans 5:8). Our freedom from condemning guilt isn’t achieved by anything we do; it’s achieved by Jesus dying in our place. It’s given to us as a free gift (Romans 6:23), a gift that we receive by faith (Ephesians 2:8–9).

All who receive this free gift not only are freed from the death sentence of sin; they also receive “the right to become children of God” (John 1:12). Barabbas is a powerful parable for all who put their faith in Jesus and his cross, not themselves and their innocence.

His Story Is Ours

God wants us to pay attention to Barabbas, because in Barabbas we are to see ourselves. God placed Barabbas in every Gospel account of Jesus’s trial and crucifixion to show us that Jesus came to willingly lay down his life (John 10:17–18) in order that the guilty could go free.

So, as we enter the Easter season, it may do our souls good to take a longer than normal look at Barabbas, the guilty man who went free — not as a bit player in history’s most momentous drama, but as a mirror of ourselves, as a reminder that we, though guilty of terrible evil, are able to receive life-giving pardon because the Son of Man was condemned in our place. And “if the Son sets you free, you will be free indeed” (John 8:36).

Jon Bloom's Blog

- Jon Bloom's profile

- 110 followers