Jon Bloom's Blog, page 18

March 15, 2018

The Path to Short-Lived Greatness

What greatness do you really value? If you’ve been a Christian very long, you know the right answer — Jesus’s answer (Matthew 23:11). But if you’re ruthlessly honest, who would you list as “the greatest among you”? The greatness you value is not necessarily what you can articulate to others, or preach from your pulpit — or write in your article — but what you secretly wish you were or who you wish you were more like.

Throughout history, human greatness has almost always been measured within some framework of meritocracy. By meritocracy, I mean any social system — great or small, formal or informal — where people earn rewards or status based on achievements that their social system values highly. Alexander the Great merited greatness through his military and leadership achievements, Shakespeare through literary achievements, Steve Jobs through technological design achievements. They each lived in very different eras and socio-cultural-political environments. But they’re remembered for their merits — for what they each achieved.

Every human culture and subculture has its meritocracies. And that's not necessarily evil. In many cases they are the most just and beneficial systems, all things considered in this age. But since we tend to have an upside-down definition of greatness — the measure of our superiority to others rather than our love for them — our meritocracies have a powerful tendency to appeal to the sinful, selfish, self-exalting parts of us.

A Strange Greatness

Which is why Jesus's definition of greatness can sound so foreign and disorienting to us:

“The greatest among you shall be your servant.” (Matthew 23:11)

It’s very tempting to take Jesus’s statement as a sort of poetic flourish, a metaphor for remembering to be kind and somewhat generous as we pursue achieving some level of relative greatness compared with others (like everybody else does). The only problem is, Jesus wasn’t speaking metaphorically. He very literally meant we should aspire to be servants.

In every culture throughout history, servants have been those who, by virtue of birth or circumstances, have been forced to spend much of their lives pursuing the good of someone else above their own. The vast majority of servants have occupied the lower tiers of social status. And while a servant might aspire to a more socially recognized and rewarded level of servitude, it has been extremely rare that a free person would aspire to servanthood. In almost every human culture, servanthood is not the path to greatness. The best servants can hope for is to serve great people (Matthew 20:25).

But in the kingdom of God, as Jesus demonstrated, servanthood is the path to greatness (Philippians 2:5–11). “The last will be first” (Matthew 20:16). Those who humble themselves will be exalted, while those who exalt themselves will be humbled (Matthew 23:12). God incentivizes our freely and joyfully choosing to put others’ interests above our own (Philippians 2:3¬–4).

This is a strange greatness to fallen humans. It is an otherworldly meritocracy — not in terms of meriting salvation (Ephesians 2:8–9), but in terms of meriting God’s commendation and rewards (1 Peter 5:6; 1 Corinthians 3:14–15; 2 Corinthians 5:9–10). It is a greatness so counter-cultural, so counter-intuitive that it is impossible to pursue unless a person really believes the gospel is true.

The Mark of Misplaced Greatness

When Jesus said, “The greatest among you shall be your servant,” the context was a scathing public rebuke of the Jewish religious leaders. Here’s some of what he said:

“The scribes and the Pharisees sit on Moses’ seat, so do and observe whatever they tell you, but not the works they do. For they preach, but do not practice. They tie up heavy burdens, hard to bear, and lay them on people’s shoulders, but they themselves are not willing to move them with their finger. They do all their deeds to be seen by others. For they make their phylacteries broad and their fringes long, and they love the place of honor at feasts and the best seats in the synagogues and greetings in the marketplaces and being called rabbi by others.” (Matthew 23:2–7)

A key — and convicting — phrase is, “they do all their deeds to be seen by others.” This revealed the heart’s affections that were fueling leaders’ behaviors. They were operating in a fallen human-defined meritocracy. They were pursuing the rewards and commendation their culture valued. In all their pious-appearing achievements, they were aiming for this-worldly greatness — and probably mistaking it for next-worldly greatness too. The evidence was that they were too preoccupied with appearing righteous in order to win human approval than to attend to “the weightier matters of the law: justice and mercy and faithfulness” (Matthew 23:23).

That is the mark of misplaced greatness: valuing one’s personal benefit and reputation more than the real good of other people.

A Greatness Only Grace Produces

So, what greatness do we really value? The ambitions that govern our motives and actions will tell us. We will always desire the treasure we believe most valuable. We will always pursue what we believe is true.

It’s not sinful to desire to be great; it’s sinful to desire idolatrous, selfish greatness. Kingdom greatness reveals the character and genius of God: the greatest among us are those who love and serve others most — who love others most by serving others most. The truly greatest among us are those who by their actions demonstrate they trust God to exalt them at the proper time and to the appropriate degrees (1 Peter 5:6), and, like Jesus, don’t measure their greatness by the commendation and rewards they receive from their social systems (John 5:41).

This is an otherworldly greatness we only pursue when we truly understand the grace of God — that the Triune God has so utterly and completely served us in every facet of our experience that we wish to freely give what we have freely received (Matthew 10:8), and in love present our bodies as living sacrifices of worshipful service (Romans 12:1).

March 12, 2018

You Must Fight Hard for Peace

The dove is a nearly universal symbol of peace. And a very appropriate one. Doves are beautiful, gentle, faithful creatures. They’re also, well, flighty creatures. It doesn’t take much to send a dove fluttering away. A harsh word, a rash gesture, and off she goes. If you want a dove to stay around, you have to be very careful how you speak and act. Which is a lot like what it takes to be at peace with other people.

The author of Hebrews tells us to “strive for peace with everyone” (Hebrews 12:14). His implication: peace — real, honest peace, not dysfunctional conflict avoidance — is hard to keep. How hard? Well, pursuing peace fits into the list of hard things he groups around this statement:

It’s hard like lifting drooping hands and strengthening weak knees when you’re tired and discouraged (Hebrews 12:12).

It’s hard like continuing to walk when your leg is injured (Hebrews 12:13).

It’s hard like living in a holiness that evidences the reality of your faith even though your indwelling sin continually tries to derail you into unholy passions (Hebrews 12:14).

It’s hard like not allowing the constant barrage of deceitful sin to harden our hearts and lead us away from God into apostasy (Hebrews 3:12–13), which is what the writer means by being defiled by a “root of bitterness” (Hebrews 12:15, quoting Deuteronomy 29:18).

It’s hard like the constant vigilance required to remain sexually pure (Hebrews 12:16).

Striving for peace with everyone is hard, like all aspects of the good fight of faith (1 Timothy 6:12). It’s spiritual warfare. Peace will always be attacked, and we have to do everything we can to stand firm (Ephesians 6:13) and live peaceably with all (Romans 12:18). It’s a great kingdom irony that we must fight hard for peace.

“Persecute” Conflict

The Greek word translated as “strive for” in Hebrews 12:14 is diōkō. It’s a strong word — stronger than modern English speakers typically mean when say “strive.” Versions of diōkō are used many times in the New Testament. Here are a few familiar examples (in italics):

Jesus: “Blessed are you when others . . . persecute you” (Matthew 5:11).

Jesus: “Saul, Saul, why are you persecuting me?” (Acts 9:4).

Paul: “I press on toward the goal for the prize of the upward call of God in Christ Jesus” (Philippians 3:14) — and Paul meant “by any means possible” (Philippians 3:11).

John: “And when the dragon saw that he had been thrown down to the earth, he pursued the woman who had given birth to the male child” (Revelation 12:13).

These examples give us some sense of what the author of Hebrews had in mind when exhorting us to diōkō (strive) for peace. We are to press on toward peace by any appropriate means possible. We are to pursue peace with relentless determination. We might even think about it as persecuting conflict — by which I mean vigorously working to prevent or end sinful conflict and putting sin to death, not persecuting people in conflict!

Patient Discernment

Obviously, not all conflict can or should be avoided. The Bible clearly warns us that “all who desire to live a godly life in Christ Jesus will be persecuted” (2 Timothy 3:12). Jesus said, “You will be hated by all for my name’s sake” (Luke 21:17). Jude instructs us to “contend for the faith” against false teachers (Jude 3). Jesus rebuked sinful religious leaders (Matthew 23:13–39), Paul rebuked Peter (Galatians 2:11–14), Peter rebuked Simon the Magician (Acts 8:20–23), and John had to confront Diotrephes (3 John 9–10).

But most of the conflicts we experience are not as clear-cut as these. Most of them are difficult to navigate because they are a mixture of valid concerns, misunderstandings, fears, and what James calls sinful warring passions, like jealously, selfish ambition, and a prideful unwillingness to admit error (James 4:1; 3:16).

And trying to discern the chemistry of a conflict, how much of which ingredient is in the mix, requires discernment and patience and endurance and forbearance and wisdom and charity (agapē love) — often just to get to the place where we can determine if a conflict really is, at root, unavoidable. It requires a rigorous, disciplined commitment to being quick to listen, slow to speak, and slow to become angry (James 1:19). It requires pressing on, doggedly pursuing; it requires diōkō — striving for peace. Because most of our conflicts are unnecessary, or unnecessarily acrimonious.

Pursue Peace to the Death

Just how far are we to “strive for peace”? Further than most of us want to go; further than we frequently feel we should go when our passions are engaged in conflict with someone.

The Bible calls Jesus the “Prince of Peace” (Isaiah 9:6). And the Prince of Peace, the Son of God, said, “Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called sons of God” (Matthew 5:9). How far did the Prince of Peace, the Son of God, go to make peace with us? To the death. Jesus made peace between us and God “by the blood of his cross” (Colossians 1:20). When we were still sinners (Romans 5:8).

How far should the sons of God go to make peace? To the death. What does that mean? It depends on the nature of the conflict. But at the very least it means, “Put to death therefore what is earthly in you” (Colossians 3:5). It means, “Love one another with brotherly affection” and “outdo one another in showing honor” (Romans 12:10). It means, “Bless those who persecute you,” “live in harmony with one another,” “never be wise in your own sight,” never “repay . . . evil for evil,” and “do what is honorable in the sight of all,” never seeking revenge when wronged, treating our enemies with graciousness and compassion, and, so far as it depends on us, living “peaceably with all” (Romans 12:14–21).

This is what it looks like to “strive for peace with everyone” (Hebrews 12:14). Most of the time, when a conflict is brewing, we should assume it is avoidable and do everything to pursue peace. We should assume the best of the other(s) and assume we are misunderstanding something or being tempted by warring passions. We should not enter into conflict as such until we have clear confirmation that it is unavoidable in the biblical sense. And even then, we speak the appropriate truth in the appropriate form of love, whether it be tough or tender (Ephesians 4:15).

This is hard. Like all forms spiritual endurance and warfare, we must strive. We must die. But this kind of dying to make peace is blessed. It’s what sons of God do. And God’s reward to his peace-making sons will be out-of-this-world wonderful.

February 27, 2018

How Do I Know If I Really Love Jesus?

How do we know if we really love Jesus? The Bible’s answer might surprise you.

We know if we love Jesus by what we consistently (not perfectly) do and don’t do. We know this because Jesus said, “If you love me, you will keep my commandments” (John 14:15). And the apostle John echoed Jesus when he wrote, “This is the love of God, that we keep his commandments” (1 John 5:3).

At face value, these statements should make any lover uncomfortable. We all know intuitively that the essence of love is not merely its actions. Love cannot be reduced to a mere verb. That’s why everyone laughs at John Piper’s illustration of a husband handing his wife a big bouquet of flowers on their wedding anniversary and then telling her he’s just fulfilling his obligation as a dutiful husband. It’s why everyone understands Edward John Carnell’s illustration of a husband asking, “Must I kiss my wife goodnight?” Because we know the answer is “Yes, but not that kind of must.”

Not That Kind of Must

Neither Jesus nor John meant that obeying Jesus’s commandments is the same thing as love. What they meant was that love for God, by its very nature, produces the consistent characteristic of “the obedience of faith” (Romans 1:5). So, on earth, love for Christ tends to look like obeying Christ.

Now, love, faith, and obedience are not the same things. Love is our cherishing or treasuring Christ, faith is our trusting Christ, and obedience is our doing what Christ says. The essence of each is different. Bad things, like dead orthodoxy and legalism, happen when we make them the same thing. We must keep Christ’s commandments — but not that kind of must.

Though they are distinct, they are inseparable. We cannot love Christ without trusting (exercising faith in) him (1 Peter 1:8). We cannot trust Christ without obeying him (James 2:17). So, naturally, we cannot love Christ if we live in persistent, conscious disobedience to him (1 John 1:6; Luke 6:46).

Wearing Our Love on Our Sleeves

This is an elegant, devastatingly simple design. God made us to wear our love on our sleeves. He wired us to serve what we treasure. How we love ourselves is evident by how we serve ourselves, for good (Ephesians 5:29) or for evil (2 Timothy 3:2). How we love our spouse or children or friends or pastors or co-workers or pets is evident by how we serve or neglect them. Whether we love God or money is evident by how we serve or neglect one or the other (Luke 16:13). In the long run, we cannot fake who or what we really serve.

It’s true that we sometimes can hide our sleeves from human view — sometimes even from ourselves — at least for a while. But God has a way of exposing our sleeves eventually.

This is what the parable of the good Samaritan was about, which nearly all of us are granted the opportunity to live out in different ways and at different times. The priest, the Levite, and the Samaritan all outed their sleeves by the ways they responded to the injured man (Luke 10:31–35).

It’s also what the story of the rich young man in Mark 10 was about. He seemed at least partially blind to the love on his own sleeve, because though he thought he had done lots of obedient things (Mark 10:19–20), something was troubling his soul — which is why he came to Jesus. But Jesus saw the man’s sleeve clearly and with one sentence drew everyone’s attention to it: “You lack one thing: go, sell all that you have and give to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven; and come, follow me” (Mark 10:21). Then it was clear: the man could not obey Jesus because he loved and trusted money more than Jesus.

We see this all over the Bible: love for God or love for idols is made visible by obedience or disobedience to God. We see it in Cain with Abel (Genesis 4), Abraham with Isaac (Genesis 22), Reuben with Bilhah (Genesis 35), Joseph with Potiphar’s wife (Genesis 39), David with Saul in the cave (1 Samuel 24), David with Bathsheba (2 Samuel 11), Judas with his silver (Matthew 26), Peter with his denials (John 18), Peter with the Sanhedrin (Acts 4), Ananias and Sapphira with others’ admiration (Acts 5), and Demas with Thessalonica (2 Timothy 4) — just to name a few.

By This We Know Love

But the most important place in Scripture (or anywhere else) we see love demonstrated through faith-empowered obedience is in Jesus:

By this we know love, that he laid down his life for us (1 John 3:16).

God shows his love for us in that while we were still sinners, Christ died for us (Romans 5:8).

Greater love has no one than this, that someone lay down his life for his friends (John 15:13).

Supreme love was made visible in Jesus’s death on the cross, where “the founder and perfecter of our faith” (Hebrews 12:2) pursued his, and our full, eternal joy (John 15:11) through his obedience in the midst of the greatest suffering (Hebrews 5:8). God wore his love on his bloody sleeve. Jesus did not merely “love in word or talk but in deed and in truth” (1 John 3:18). “By this we know love.”

How do we know if we love Jesus? By what we consistently (not perfectly) do and don’t do. All lovers of Jesus keenly know we don’t love him perfectly. “We all stumble in many ways” (James 3:2), and “if we say we have no sin, we deceive ourselves, and the truth is not in us” (1 John 1:8). But “if we say we have fellowship with [Jesus] while we walk in darkness, we lie and do not practice the truth” (1 John 1:6).

We know what love is by what love does. All lovers of Jesus refuse to walk in persistent, conscious disobedience to him. Our faith-empowered obedience in public and private places is the God-designed evidence of our love for Jesus.

February 23, 2018

The Best Way to Find God’s Will for Your Gifts

Let’s imagine, for the sake of illustration, that you’re not very familiar with fish (perhaps you don’t have to imagine). And you’ve agreed to participate in an experiment where you’re asked to identify whatever is placed before you. You don’t know it, but you’re about to view anatomical parts of a largemouth bass.

First comes the translucent green pectoral fin in a petri dish. You look at it and answer, “Is it some kind of leaf?” Next comes the slimy swim bladder. “Gross! I’m guessing it’s some small animal’s intestine or something.” Next comes a red piece of gill tissue. “I have no idea what that is!”

Now, had you viewed these parts in the context of the fish’s body, you’d grasp to some degree their importance in helping the fish function properly. But taken out of the context of the body, the parts make little sense. It takes the fish’s body to understand the function of a part and it takes all the parts to make a fish function.

“So it is with Christ” (1 Corinthians 12:12). Each of us is a part of the body of Christ and has a particular function. But it takes the body of Christ to understand the function of a part and it takes all the parts to make the body function.

Designed to Depend

If you’re struggling to figure out how God wants to use you, one possibility is that you’re examining yourself out of context, isolated in a petri dish, so to speak.

This is essentially the way we in the West (especially in the United States) are trained to see ourselves. Perhaps more than at any other time in history, our culture understands individuals as autonomous units rather than interdependent parts of a larger social organism.

Today, we largely view interdependence on others as optional, not necessary — partly due to our nearly sacred cultural value of individual liberty, and partly due to all the technological advancements that enable us to pursue it in unprecedented ways. We’re free to voluntarily associate, and free to go it alone. Interdependence on others is only really necessary on the meta-scale, where we need large-scale systems to distribute things like food, clothing, and energy, or facilitate things like mass communication, mass transportation, government, and finance.

As a result, when it comes to determining how each of us should use our time, abilities, resources, and relationships, we primarily assess them based on how these things will advance our individual goals and dreams or cater to our individual preferences. In the abstract, we think working toward the common good is a good thing. But in the concrete world of day-to-day life, we see ourselves as independent, autonomous bodies, and so the individual good is the best thing.

But there’s a problem: we aren’t designed to be billions of independent, autonomous bodies primarily doing our own thing. God designed us to be interdependent body parts that contribute to the healthy functioning of a larger social body.

So if we conceive of the purpose of our lives as primarily an individual pursuit of happiness, it’s no wonder we can find discerning where God wants us to invest our lives illusive and perplexing. It’s like a pectoral fin or swim bladder or gill tissue trying to figure out in the petri dish what it should do. Body parts don’t make sense, much less function right, apart from the body.

Where Your Life Is Meant to Make Sense

That’s what 1 Corinthians 12 (and 13 and 14) is all about. Paul writes,

For just as the body is one and has many members, and all the members of the body, though many, are one body, so it is with Christ. (1 Corinthians 12:12)

We aren’t each individual bodies of Christ. We collectively “are the body of Christ and individually members of it” (1 Corinthians 12:27). Our lives are meant to make sense in the context of the body of Christ because each of us has a God-given function to perform — a function that is interdependent on other functioning parts.

Christ’s body is the primary context in which God intends for our unique gifts and kingdom callings to be revealed, confirmed, and engaged. And what Paul primarily has in mind by “Christ’s body” in 1 Corinthians 12 is our local church.

Millennia before there were tests for profiling our personalities, finding our strengths, or identifying our spiritual gifts, there was the local church, where each member was “given the manifestation of the Spirit for the common good” (1 Corinthians 12:7). That’s what the spiritual gifts — both more supernatural gifts (like miracles and healing) and more constitutional gifts (like administrating and helps) — are for: the common good of the expression of Christ’s body we belong to.

God eventually calls a few of us to serve broader portions of Christ’s body in various ways. And he calls some of us to isolated situations, like remote church planting, frontier missions, and imprisonment — where “body life,” at least for a while, doesn’t look or feel typical. But like Paul and the church in Antioch, such callings are meant to be confirmed in, commissioned by, and accountable to our local church body, if at all possible.

Like every thing else in our defective world, there are exceptions — diseased local churches that aren't facilitating a healthy body made up of interdependent members. Sometimes God calls us to be agents of improved health for such a body, and sometimes he directs us to find a healthier body.

And, of course, no church does "body life" perfectly because they're all comprised of imperfect people, like us. But nonetheless, the local church is God's bodily provision for us, the context where our lives are meant to make sense.

Where Do You Look for God’s Direction?

Understanding ourselves and each other as interdependent members of a corporate body is very different from what we’ve learned from our culture. And even though we might be very familiar with 1 Corinthians 12, and abstractly admire Paul’s “body” analogy as a theological concept, it does not mean we’ve internalized it and that it’s shaping and governing us.

We can tell what understanding of ourselves and others shapes and governs us by how we answer this question: Where do we look for God’s direction on how we should use our giftings? Do we see this as primarily an individual quest for self-actualization, or are we looking for it in the context of Christ’s body as we seek to meet the needs of others? Most of us Americans naturally gravitate to the former, and we must relearn to seek for it in the latter.

And there is no neat-and-clean formula. It’s not fast, like a test. It happens in the messiness of the life of the body. But if we fixate less on our particular part and more on the good of others and the common good of the larger body, God will faithfully show us what members we are. That’s God’s design. Pursue love (1 Corinthians 14:1), and we will discover his will for us. Seek first the kingdom, and all we need will be provided (Matthew 6:33).

It takes the body of Christ to understand the function of a part, and it takes all the parts to make the body function.

February 15, 2018

Know What Not to Say

Christians should be the most careful speakers in the world. We ought to be characterized by two kinds of trembling when it comes to words: we should tremble at the words God speaks and we should tremble at the words we speak.

We know we should tremble at God’s word, for he tells us,

“This is the one to whom I will look: he who is humble and contrite in spirit and trembles at my word.” (Isaiah 66:2)

But why should we tremble at the words we speak? Because Jesus said,

“I tell you, on the day of judgment people will give account for every careless word they speak, for by your words you will be justified, and by your words you will be condemned.” (Matthew 12:36–37)

“Every careless word.” That should stop us in our tracks. It should set us trembling, considering how many words we speak. And by “speak” I mean every word that comes out of our mouths, our pens, and our keyboards. We speak thousands of words every day, sometimes tens of thousands.

When we experience these two kinds of trembling, they occur for the same reason: we love and fear God and don’t want to profane his holy word or to profane his holiness with our unholy words. Such trembling makes us want to speak carefully and sometimes not speak at all. Because we believe,

For everything there is a season, and a time for every matter under heaven: . . . a time to keep silence, and a time to speak. (Ecclesiastes 3:1, 7)

A Time to Be Silent

There really is a time to keep silent. And that time comes more often than most of us are conditioned to think.

We live in an age of unceasing talk. Never in human history has the noise of human communication been so constant. Even when we are quiet we are not silent, as we receive and dispense talk through our digital media. Our culture does not believe that “a fool multiplies words” (Ecclesiastes 10:14).

On one level, it believes that multiplied words brings multiplied knowledge, and multiplied knowledge brings multiplied wisdom. On another level, not fearing God, it simply doesn’t really care how many words flow. So it relentlessly inundates us with information, analysis, commentary, critique, punditry, and mockery through every communication stream. We cannot help but be conditioned by this environment.

And with the advent of social media, nearly everyone now has a broadcast platform from which they can publicly hold forth on any social, cultural, political, economic, or theological issue, any controversy, any scandal, any whatever anytime they wish, regardless of what they know. And while the democratization of public communication is a remarkable historic phenomenon and certainly has some wonderful benefits, it is a dangerous thing, spiritually speaking. It’s an immense, cacophonous forum of multiplied, foolish, careless words, for which every participant, whether they know it or not, will give an account to God.

The Beginning of Wisdom

Christians know that “the fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom” and “the beginning of knowledge” (Psalm 111:10; Proverbs 1:7). And one expression of that fear is trembling at God’s holy word, and at our own.

We are taught that it is profoundly wise for us to cultivate the discipline of being slow to speak (James 1:19). Slow to speak implies that there is a time for silence. Sometimes it means we are silent for some appropriate brief or extended period of time while being quick to hear (listening carefully), so we gain an accurate understanding of an issue before we speak carefully. And sometimes it means we don’t speak at all. The former is always a necessity for us; the latter is often a necessity.

God calls us to live counter to our hair tongue-trigger culture. In a world where rapid-fire information, rapid-fire commentary, and rapid-fire counter-commentary are continually igniting raging forest fires of words (James 3:5), the sons and daughters of God are called to be fire-quenching peacemakers (Matthew 5:9). And one of the underutilized ways of peacemaking is recognizing the time to keep silence. Less words can be less fuel for the fires.

A Time to Speak

But Christians must not always keep silence. There is a time to speak and there are things we must say. Our God is a speaking God and we know he most definitely wants us to speak (Matthew 24:14; 28:19–20).

But when God speaks, he speaks very intentionally and, considering his omniscience, he speaks with tremendous restraint. And that’s the way he wants us to speak, as his exceedingly non-omniscient children and ambassadors (2 Corinthians 5:20): intentionally and with restraint. He wants us to learn to speak like Jesus.

We, like Job, have the tendency to speak rashly and confidently about things we really don’t understand (Job 42:3). But Jesus often said less than he knew because he was prayerfully listening to the Father and saying only what he discerned he was supposed to say (John 8:26). Just because he had a mouth and a public platform did not mean he should always employ them. Rather, he said, “I do nothing on my own authority, but speak just as the Father taught me” (John 8:28). He perfectly lived out and modeled for us this verse:

Set a guard, O Lord, over my mouth; keep watch over the door of my lips! (Psalm 141:3)

God deploys his children strategically in every sphere. He gives us each a few assignments and gives us each some things to say in order to bring the gospel to bear in our limited spheres. Each of us must prayerfully discern our spheres and limitations. None of us, as individuals, churches, or organizations, is called to address every current issue. And if this is true of issues we have knowledge about, it’s especially true of issues with which we have little or no personal experience.

If we are in some form of leadership where we are called to address such an issue, we should first pray for wisdom, then we should be publicly honest about what we don’t know and not succumb to pressure and try to speak more than we do know. And then, if the Lord leads, we should pursue the understanding required to speak more helpfully.

And when we do discern God’s direction for us to speak, we, like Jesus, remember that our mouths, fingers, and platforms still belong to God. We are not free to say whatever we wish about what we know. We do nothing on our own authority, but must say only what we discern God wants us to say.

Tough, Tender, or Quiet?

We speak the truth in love (Ephesians 4:15), but we don’t speak for human “likes”; we speak for God’s approval. So that means we sometimes speak a loving truth that’s tender and sweet (Proverbs 16:24), and other times we speak a loving truth that’s graciously hard (Proverbs 27:6). This is speaking like Jesus, who sometimes said things like, “Come to me, all who labor and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest” (Matthew 11:28), and who at other times said things like, “Unless you repent, you will all likewise perish” (Luke 13:5).

Discerning when to say a loving tender truth, when to say a loving tough truth, and when to say nothing at all is the tension God has purposefully designed to keep us prayerfully dependent on him. It is frequently not patently obvious. There are times we really want to speak and we should not. And there are times we really don’t want to speak and we should.

What will help us most in discerning when it’s a time to keep silence or a time to speak is cultivating a holy trembling at God’s word and at our words. The right kind of fear of the Lord is our best mouthguard.

February 11, 2018

Lord, Set Me Free from Fear

On Thursday night, Peter said to the One he knew was “the Christ, the Son of the living God” (Matthew 16:16), “Even if I must die with you, I will not deny you!” (Matthew 26:35). Then, in the wee hours of Friday morning, Peter said to a couple of servant girls he didn’t know at all, “I do not know the man” (Matthew 26:69–72).

What in the world happened to Peter that made him do exactly what he swore he would not do? Fear happened to Peter.

Then, just a few weeks later, Peter found himself in front of the Sanhedrin — the same Sanhedrin that had terrified him the night of Jesus’s trial — and instead of denials, out of his mouth came these words: “Whether it is right in the sight of God to listen to you rather than to God, you must judge, for we cannot but speak of what we have seen and heard” (Acts 4:19–20).

What in the world happened to Peter that suddenly made him so bold? Faith happened to Peter.

Like Peter, we too are no match for the crippling fear that will seize us when faced with potential or real danger, if we only see things with the eyes of our flesh. In fact, we’ll tend to be easily intimidated by all sorts of things. But if by the power of the Holy Spirit, we see with the eyes of faith, we’ll see things as they really are and our fears will melt away.

That power, which freed Peter from fear and fueled his boldness, is available to every Christian. It is ours for the asking, and ours for the taking.

Malfunctioning Mercy

Like everything God made, fear is very good when it functions according to its intended purpose. Fear is designed to keep us away from dangerous things. When fear moves us to avoid things that are truly dangerous, we experience just how merciful a gift it can be. God created fear to help keep us free. He meant it to protect us from all manner of real harm so we can remain as free as possible to live in the joy he intended.

But after the fall, like everything else God made for us, fear has been distorted by sin, and by the brokenness of our fallen bodies and minds. So, it frequently does not function the way God designed. Due to our fleshly pride and unbelief in what God promises us, we fear things that aren’t truly dangerous at all. We feel too much fear of things that are relatively small threats and too little fear over things that can cause us far greater harm (Luke 12:4–5). Our fears are disordered and disproportionate.

Disordered fear is what Peter experienced during Jesus’s trial. The Son of the living God, whose power he had personally observed and experienced — power that raised the dead (Mark 5:41) and even made demons subject to Peter (Luke 10:17) — was now in the custody of the Sanhedrin. Things had taken a perilous turn. All those strange things Jesus had been saying about suffering and dying at the hands of the rulers — the things Peter had told Jesus should never happen to him (Matthew 16:21–23) — looked like they were happening.

Seeing Wrongly Leads to Fearing Wrongly

That was the root issue: how things looked. The things Jesus said would happen were indeed happening, but Peter’s mind was still set on the things of man, not God (Matthew 16:23). He was only seeing the human side of things, so it looked like everything was happening wrongly. This sucked the faith right out of him — and filled him with fear.

The same thing happened to the prophet Elisha’s servant. Do you remember the story? The king of Syria discovered Elisha was receiving words from the Lord about Syria’s military plans, and informing the king of Israel. So, the Syrian king took a big army and surrounded the city where Elisha was staying. In the morning, Elisha’s servant saw the troops and was terrified. So Elisha prayed, “O Lord, please open his eyes that he may see,” and suddenly the servant saw the mountains full of the host of heaven (2 Kings 6:17). When the servant only saw the human side of things, he was overcome by fear because he saw wrongly. But when, by the Spirit’s power, he saw rightly, his faith revived and his fear melted away.

So too, when Peter, by the Spirit’s power, saw rightly, his faith was revived and his fear melted away. He went from cowering in front of servant girls to boldly confronting the very leaders who had crucified Jesus (Acts 4:8–12).

O Lord, Open Our Eyes!

Elisha prayed for his servant, and he saw the spiritual reality. Someone prayed for Peter, too: “I have prayed for you that your faith may not fail” (Luke 22:32). Jesus prayed for Peter’s faith. The timing and purposes for Elisha’s and Jesus’s answered prayers were different. But the outcome was the same: the formerly fearful men became bold in faith.

Are we fearful? Do we find ourselves easily intimidated into silence or inaction or even outright denials? It is because we are seeing reality wrongly. We are blind to what God is actually doing. For if, by the Spirit, we see what God is doing in the spiritual realm, we would not stop speaking of what we have seen or heard.

This is available to us! That’s why God put these stories in the Bible. And it’s why he has surrounded us with the great cloud of Christian witnesses throughout history. Let’s ask God for freedom from unbelieving fear and a new boldness. Let’s lay hold of him until he grants our prayer. And let’s not just ask — let’s begin to confront our fears by stepping out in faith and obediently trusting his promises. The provision of boldness is often given to the one willing to act in obedience.

Father in heaven, whatever it takes, set us free from unbelieving fear by opening our eyes to reality. Do not allow us to remain silent or inactive. The freest people in the world are those who trust you most. We will not let you go until you bless us, because you are too glorious and souls are too precious for us to remain muted by fear. In Jesus’s name, Amen.

February 8, 2018

God Wants More for You Than You Do

If January is often a month of new beginnings, a New Year’s clean slate, which we greet with a this-year-is-going-to-be-different kind of optimism, then February is often a month of discouraging realism. We often find our inflated hopes for change have sprung a leak, and our feet are back on the difficult ground where we started.

The euphoria we felt when we made our resolutions once again didn’t carry us over the arduous terrain to the promised land of transformation.

We’re all familiar with that euphoric feeling. It’s the surge of optimism we experience when we see the gracious benefits we could enjoy if we were to achieve a certain goal. The euphoria inspires us to form a new resolve to pursue that goal. And if kept in its proper perspective, it’s very helpful. God designed us to experience that feeling to encourage us to undertake the struggle of pursuing a new and better direction.

But God did not design the euphoria to carry us through the struggle. He intended us to follow through with prayerful determination, planning, discipline, perseverance, accountability, and endurance. Euphoria is the foretaste of the future grace we desire. It helps launch us on the difficult journey to obtain it. But if we mistake the euphoria as being the same thing as a resolution, we should not be surprised when our “resolutions” seem to evaporate.

Infatuation Isn’t Enough

Here are a few illustrations of what I mean:

To see the euphoria of a weight loss resolve, talk to someone who has just started a new diet program, or who has just lost 20 pounds in the last few months. But to know the real nature of the struggle and the benefits of weight loss, talk to someone who has kept off the weight for five years or more.

To see the euphoria of a Bible reading and prayer resolve, talk to someone who has just started a new plan, or has been keeping up with a plan for a few weeks now. But to know the real nature of the struggle and benefits of these spiritual disciplines, talk to someone who has persevered in them for many years.

To see the euphoria of romantic infatuation, talk to someone who has recently fallen in love. But to know the real nature of the struggle and benefits of romantic love, talk to someone who has faithfully loved the same person for decades, for better or for worse.

Now, in most cases, things like successful long-term weight loss, long-term exercise of spiritual disciplines, and long-term covenantal love begin with the excitement and hope of a new beginning. The eager enthusiasm is a good thing as far as it goes — as long as we remember it doesn’t go very far. No one who’s been on a real adventure very long is sustained by the adrenaline rush of initial excitement. Infatuation is not enough. It wasn’t meant to be. We need something more.

God Wants More for Us Than We Do

We actually need a lot more. And the reason we need a lot more than excitement to keep us going is because the transformation we need most — the transformation God is aiming for — goes far deeper and involves far more than we typically understand or expect at first.

Let’s take weight loss for example. If we’re overweight, we think what we need is to lose the weight and then we’ll be happy. Therefore, what we think we need is to stick to a diet and exercise regimen. Seems simple.

We make an enthusiastic, optimistic start, and maybe even make some encouraging progress, only to discover reality isn’t nearly so simple. We discover all sorts of powerful appetites and habits and fears and past pain and temptations at work in us that we didn’t fully appreciate. Jesus captured the difficulty in these few words: “The spirit indeed is willing, but the flesh is weak” (Matthew 26:41).

The Flesh Is Weak

The flesh is weak. That is the primary reason our resolves, especially worthy resolves, are so hard to keep. Like the disciples in their early days with Jesus, we are prone to underestimate the weakness of our flesh. And like the disciples, this is not only true regarding our fortitude, but also our motives. Unless the Lord disciplines us (Hebrews 12:3–11), we too tend to be more motivated in our resolves by a desire to be the greatest than a desire to truly serve others out of love for them (Luke 22:24).

God wants far more for us than we typically want for ourselves. Jesus said, “It is the Spirit who gives life; the flesh is no help at all” (John 6:63). In his school of discipleship, he is aiming at helping us learn to walk by the Spirit so we won’t gratify the sinful desires of the flesh (Galatians 5:16). For the Christian, God uses the futility (Romans 8:20), as well as our sufferings (2 Corinthians 4:17), as a means of producing a more profound transformation in us.

What God wants for us is faith, virtue, knowledge, self-control, steadfastness, godliness, brotherly affection, and love (2 Peter 1:5–7). And all these things are cultivated through the various difficult struggles of pursuing a resolve.

How to Fulfill Every Good Resolve

We were never meant to fulfill our resolves on our own, because the transformation we need most requires a wisdom and power far beyond ours. Which is why Paul wrote,

To this end we always pray for you, that our God may make you worthy of his calling and may fulfill every resolve for good and every work of faith by his power, so that the name of our Lord Jesus may be glorified in you, and you in him, according to the grace of our God and the Lord Jesus Christ. (2 Thessalonians 1:11–12)

Every resolve for kingdom good — which are the only kind we should pursue, whether it’s weight loss, spiritual disciplines, a potential marriage partner, or something else (Matthew 6:33) — and every work of faith requires the power and wisdom of God, because the outcomes God wants are bigger than we can produce.

God set it up this way so that we would experience the maximum, multilayered, fruit-producing joy from each outcome and his multifaceted glory would shine most brightly through us. If we understand this from the outset, we can receive as God’s gift the euphoric feeling we experience when we first resolve to undertake a work of faith. God grants it as a foretaste of future grace and to help us get started. But it is not a balloon to float us over the difficult road.

The real, substantial, faith-growing, love-expanding, endurance-training, joy-producing benefits are only realized through the hardship of pursuing our resolves. So do not lose heart in pursuing yours.

February 1, 2018

Holiness Will Make You Unbelievably Happy

Christian, when have you been most free from sin?

When have you been least motivated by selfish ambition and laziness and lust and self-righteousness? When has the fear of man, the general cares of this world, and the deceitfulness of riches wielded the least influence over you (Matthew 13:22)? When have you felt the most capacity to love others and the most concern for perishing unbelievers, the persecuted church, and the destitute poor?

In other words, when has your life been most characterized by holiness?

I can tell you when. It’s when you’ve been most in love with Jesus. It’s when you’ve been most full of faith in his promises so that you live by them. It’s when his gospel has been most meaningful and his mission has been most compelling, so that they dictate your life’s priorities.

In other words, you’ve been most holy when you’ve been most happy in God.

Holiness is fundamentally an affection issue, not a behavioral issue. It’s not that our behaviors don’t matter — they matter a lot. It’s just that our behaviors are symptomatic. They are the outworking of our affections in the same way that our behaviors are the outworking of our faith (James 2:17).

Why Holiness Has a Bad Rap

For many Christians, holiness has largely negative connotations. They know holiness is a good thing — because God is holy — and it’s something they should also be — because God says, “You shall be holy, for I am holy” (Leviticus 11:44; 1 Peter 1:16). But they think of holiness primarily in terms of denial, as sort of a sterile existence. In fact, God’s holiness is something they tend to fear more than desire.

This is understandable, especially if the teaching they have received has emphasized behavioral holiness over affectional holiness. The Old Testament has a lot of very serious things to say about holiness. When Yahweh called Moses (Exodus 3:10) and delivered the people of Israel, it is clear his holiness was nothing to be trifled with. It was lethal if it was ignored or neglected (Exodus 19:12–14). Also, eight, arguably nine, of the Ten Commandments are prohibitions: “You shall not . . . ” (Exodus 20:1–17). Reading through the requirements in Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy, the overall emphasis we get is the rigor that was required to maintain holiness before God and the warnings given if it wasn’t.

God’s Mercy in All His Prohibitions

But while that impression of holiness is understandable, it is very wrong. Holiness is neither dominantly denial, nor is it sterile purity. We need to remember why God instituted the rigorous moral and ceremonial laws: “in order that sin might be shown to be sin” (Romans 7:13).

[For] if it had not been for the law, I would not have known sin. For I would not have known what it is to covet if the law had not said, “You shall not covet.” But sin, seizing an opportunity through the commandment, produced in me all kinds of covetousness. For apart from the law, sin lies dead. (Romans 7:7–8)

All the prohibitions and all the warnings are all mercy, because God wants us to know what our biggest problem is, how deep it goes (Romans 7:15–18), its horrific consequences (Colossians 3:5–6), and how hopeless we are to make ourselves holy (Romans 7:24), in order to point us to the glorious solution he has provided to our biggest problem (Romans 7:25; Romans 5:6–10).

God only emphasizes our unholiness, our sinful state, so that we can escape its grip and its consequences — and know the full joy of living in the abundant, satisfying goodness of God’s holiness. We must understand the nature and seriousness of our disease in order to pursue and receive the right treatment. But, remember, the diagnostic tool’s job is to emphasize the nature of the disease more than the essence of health.

What Holiness Is Really Like

If we want to know the essence of the health of holiness, we need to look elsewhere, like Psalm 16:11: “In your [holy] presence there is fullness of joy; at your right hand are pleasures forevermore.” That is what holiness is really like: as much joy and pleasure as we can contain for as long as is possible — which, because God grants it, is forever.

Do you see it? Holiness is not a state of denial, characterized by abstaining from defiling thoughts, motivations, and behaviors. True holiness is a state of delight. And the more true holiness we experience, the fuller our joy and greater our pleasures!

Holiness is fundamentally an affection issue, not a behavioral issue. This is only emphasized by the fact that all the Law and the Prophets — all the prohibitions and warnings pertaining to our behaviors, the height of holiness — are summed up in the greatest commandments to love God with all we are and our neighbors as ourselves (Matthew 22:37–40). Holiness looks most like the delight of true love. And if we love Jesus, we will keep his commandments — meaning that when our affections are really engaged, our behaviors naturally follow (John 14:15).

To Be Holy, Seek Your Greatest Happiness

God is supremely holy. And God is supremely happy (1 Timothy 1:11). God is love (1 John 4:8). And he is all light with no darkness (1 John 1:5). All that is good, all that brings true, lasting joy, and all that is truly, satisfyingly, eternally pleasurable comes from him.

And we are to be holy as he is holy (1 Peter 1:16). So, to pursue holiness, we must pursue our greatest happiness. Who has delivered us from our bodies of indwelling, sin-induced death? Jesus Christ (Romans 7:24–25)! Our unholy sin disease has been given a cure in the cross. We no longer need to fixate on the diagnostic tool of the law. Now, in pursuit of holiness, we aim primarily at our affections, not primarily at our behaviors. For behaviors are symptomatic of the state of our affections. What is a delight to us ceases to be a duty for us.

So God’s call to move “further up and further in” in holiness is an invitation to joy! Your fullest happiness ends up being the “holiness without which no one will see the Lord” (Hebrews 12:14).

January 29, 2018

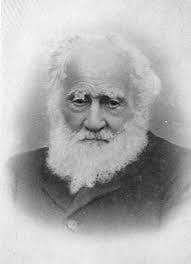

The Best Leaders Are Often Least Noticed: Robert Chapman (1803–1902)

Robert Cleaver Chapman tried his best to be forgotten, but God intervened on our behalf.

An unusually humble man, Chapman would have been pleased if you haven’t heard of him — and most Christians haven’t. And he would have likely protested my drawing your attention to him here. But I’m doing it anyway because I know you’ll be the richer for knowing him. And I doubt he minds now, having lived in heaven for nearly 120 years.

You might be surprised to know that he was one of the most influential Christians in 19th-century England. Many prominent English leaders of that era whose names you do know, like Charles Spurgeon, J.C. Ryle, Hudson Taylor, George Müller, even Prime Minister Gladstone, knew, loved, and revered Robert Chapman, and sought his counsel. Why?

He became legendary in his own time for his gracious ways, his patience, his kindness, his balanced judgment, his ability to reconcile people in conflict, his absolute fidelity to Scripture, and his loving pastoral care. (Agape Leadership)

In short, it was the beautiful and (sadly) rare way Chapman loved others that made it crystal clear to everyone whose disciple he was (John 13:35). Spurgeon called him “the saintliest man I ever knew.”

From Birth to Barnstaple

Robert was born in 1803, to Thomas and Ann Chapman. It was clear early on that he was very bright. At age fifteen, he left home to apprentice as a lawyer in London. He excelled in his apprenticeship and by age twenty became an attorney of the Court of Common Pleas and of the Court of the King’s Bench. A couple years later he started his own law practice. Experienced lawyers saw a promising professional future for Robert.

But during his apprenticeship he also experienced a growing spiritual hunger. An older Christian lawyer befriended Robert and invited him to John Street Chapel, where, under the evangelical preaching of Harington Evans, the twenty-year-old Chapman understood the gospel and was converted.

Over the next few years, Chapman became increasingly involved in the ministry of John Street Chapel and Evans mentored him in preaching. But as his interest in studying the Bible and participating in gospel outreach increased, his interest in law decreased.

Finally, at age twenty-nine, Chapman gave up law altogether and agreed to become the pastor of a little Baptist church called Ebenezer Chapel in Barnstaple, a town of about seven thousand in the southwest of England. He would minister there for the next seventy years.

Agape Leader

Before becoming a pastor, Chapman had resolved to not merely preach Christ, but to live Christ. And when he stepped into pastoral leadership at Ebenezer Chapel, he had ample opportunity to exercise his resolve.

Ebenezer had so many internal conflicts that it had burned through three pastors in the eighteen months before Chapman arrived. Not only that, but some of Chapman’s theological convictions differed significantly from the church’s. The situation was ripe for another short pastorate, but that didn’t happen. Why?

Because Chapman really believed in the power of and practiced prevailing prayer. And he had supreme confidence in the power of the word faithfully and prayerfully preached to transform people. And he determined to be doggedly patient and tender with the people. Rather than exacerbate tensions by trying to push through theological and structural changes quickly, even ones he felt strongly about, Chapman committed them to prayer, faithfully preached and taught the Bible, and extended to the people tenacious, persevering love. Eventually, most people in the church embraced what Chapman taught and modeled.

Division in the Church

But not everyone did, which provided Chapman a very different opportunity to live Christ in an even more profound way.

Two years into his ministry, despite doing all he could to prevent it, a small group of Ebenezer members split off to form their own church. Not only that, but this group demanded that the rest of the church move out of the building, since they saw themselves as the faithful remnant of the church’s original convictions. In response to this, Chapman did something unusual: he led the rest of the saints at Ebenezer (the majority group) to relinquishing the building to the splinter group. He believed it was better to be wronged than to have Christ’s name put to shame in the town because of infighting over property. The Ebenezer saints made due for a few years until they were able to build what later became known as the Grosvenor Street Chapel.

But this turned out not to be exceptional for Chapman. He practiced this kind of love at all levels, great and small. He frequently gave needy people he met the literal coat off his back. Or he’d give away the last bit of money he had, even if it was his train fare home from some place. This happened with some regularity, and when it did, Chapman would board the train and simply ask the Lord to provide his fare, which he always did. The frequent guests who stayed overnight at his home always found their shoes cleaned and set outside their doors in the morning. And since many of the folks who attended his church were domestic workers who had precise work start times, he sought to always begin and end meetings on time.

As you can imagine, Chapman’s consistent, godly agape leadership over the course of decades fostered a culture of love in the church he led. And its effects lasted beyond his life. A generation later, the church resulting from the small splinter group ended up revering Chapman. And the Grosvenor Church remains a thriving, evangelical witness for Christ in Barnstaple to this day.

Blessed Peacemaker

Chapman became renown for the gracious and tender way he treated people. But that didn’t mean he wasn’t tough. He stood firm on his settled biblical convictions, and once said to a friend, “My business is to love others, not to seek that others shall love me.” But, since he was so consistently patient and kind, even in disagreement, others tended to love him.

A man strong in the Scriptures, full of wisdom, and deeply concerned that Jesus’s church not veer into unfaithfulness, Chapman was drawn into numerous theological controversies and conflicts between church leaders. He really did grieve over the damage that leaders’ pride and impatience caused in the body of Christ. He rigorously practiced, and encouraged others to practice, Paul’s admonition that “the Lord’s servant must not be quarrelsome but kind to everyone, able to teach, patiently enduring evil, correcting his opponents with gentleness” (2 Timothy 2:24–25).

In cases where people became angry with Chapman and withdrew from him, he always pursued them, doing everything he could to be at peace with them (Romans 12:18). And as long as the tension and distance remained,

Chapman referred to them as “brethren dearly beloved and longed for” (Philippians 4:1). His sorrow was genuine. There was no sense of “good riddance” on his part. He had no sense of relief to be done with those who . . . opposed him and would have no further Christian fellowship with him. These were his “brethren whose consciences lead them to refuse my fellowship and to deprive me of theirs.” (Robert Chapman: Apostle of Love)

Apostle of Love

From the time of his arrival in Barnstaple till the end of his life, because of his deep love and concern over people’s souls, Chapman was a relentless evangelist.

He talked with people on the streets and at their houses or rooms. He frequently held gospel meetings in the workhouses and talked individually with the homeless and destitute inmates. . . . He began open-air preaching . . . and became quite good at it. (Robert Chapman: Apostle of Love)

Many came to Christ due to Chapman’s personal witness.

He also carried the unreached nations heavy on his heart, and he interceded daily for them. He had a particular burden for Spain. He taught himself Spanish and took three different extended trips, walking the length and breadth of the country for months at a time to personally evangelize lost Spanish people and to encourage the few Christians there. He also spent time in Ireland doing the same thing.

Chapman developed a friendship with Hudson Taylor and was an enthusiastic intercessor, financial supporter, and U.K. representative for the China Inland Mission. And he loved George Müller and his orphan work in Bristol. Müller considered Chapman one of his most trusted counselors.

Chapman never married. But his home was rarely lonely because he made it into a place of refuge and refreshment for weary and discouraged Christian workers. Many pastors and missionaries were profoundly encouraged by spending time with and receiving counsel from this godly, gentle saint.

Example Worth Examining

Robert Chapman had a long and fruitful ministry — he lived to be 99 years old and left no blemish of moral failure. He preached his final sermon at Grosvenor Street Chapel when he was 98 (and went an hour and a quarter!). He was spiritually, mentally, and physically healthy and vigorous right up to the end — evangelizing, visiting, counseling, teaching, and especially interceding. Then on June 2, 1902, he suffered a stroke, which led to his death ten days later, on June 12th.

One of the reasons we haven’t heard more about Robert Chapman is that he sought to remain anonymous. He was disturbed by the phenomenon of Christian celebrity in his day and didn’t want people thinking more highly of him than they ought to think. He discouraged most efforts to publish his sermons and other writings, and even burned most of his personal papers to discourage the tendency he saw for people to turn leaders into posthumous heroes. Because, as he once said, “What is most precious in the sight of God is often least noticed by men” (Agape Leadership).

Robert Chapman didn’t want people to look at him; he wanted them to look at Jesus Christ. He didn’t want to distract others from Christ. And, of course, he was right about this: no one surpasses Jesus as a model of loving leadership. No one has shown greater love (John 15:13). More than anyone else, we need to keep “looking to Jesus” (Hebrews 12:2).

But I do think Robert Chapman is worth examining, and I wish he hadn’t destroyed his papers. I’m thankful for Robert Peterson and Alexander Strauch, who have compiled most of what is available about Chapman into helpful biographies. For Jesus said, “By this all people will know that you are my disciples, if you have love for one another” (John 13:35). And Chapman took that “if” very seriously. He lived that verse.

We need as many models of such love as possible.

January 25, 2018

God Is More Precious in the Valley

David was trekking through the arid Judean wilderness when he wrote,

Because your steadfast love is better than life, my lips will praise you. So I will bless you as long as I live; in your name I will lift up my hands. (Psalm 63:3–4)

David’s wilderness wandering was no “Walden” experience for him. He was not on a desert spiritual retreat to escape the busyness of life and reconnect with God. David was retreating from people who wanted to kill him (Psalm 63:9). Once again, he was trying to keep a step between himself and death (1 Samuel 20:3), and he felt its chill breath on his neck.

So, telling God that his love was “better than life” was no hyperbolic, romantic, poetic flourish for David. It was the cry of his heart while facing the fierce reality of death. It was his privation of apparent security that heightened David’s sense of the preciousness for what God had promised to be for him. And so, it was another example of the sweet psalmist of Israel (2 Samuel 23:1) writing one of his sweetest psalms in one of his bitterest experiences.

God’s Greater Gifts

That is a consistent experiential pattern in the lives of saints throughout the Bible and the history of the church. The people of God typically experience the preciousness of God more in seasons of privation —

in hardship or need — than in seasons of prosperity. Which is why Christians pray strange things like this:

Let me learn by paradox

that the way down is the way up,

that to be low is to be high,

that the broken heart is the healed heart,

that the contrite spirit is the rejoicing spirit,

that the repenting soul is the victorious soul,

that to have nothing is to possess all,

that to bear the cross is to wear the crown,

that to give is to receive,

that the valley is the place of vision. (“The Valley of Vision”)

The valley is the place of vision? The preciousness of God is experienced in privation? At first this can seem counterintuitive. Didn’t Jesus tell us that the Father loves to give good gifts to his children (Luke 11:9–13)? Yes. Wouldn’t prosperity more effectively communicate God’s goodness to us than privation? Ultimately, yes. In fact, isn’t privation the withholding of good gifts while prosperity is giving good gifts? No, not if privation is a means God uses to give us the best gifts of the best prosperity — which is precisely what he does.

The Prospering Power of Privation

One place (of many) the divine logic can be seen is in something the apostle Paul wrote a millennium after David:

So we do not lose heart. Though our outer self is wasting away, our inner self is being renewed day by day. For this light momentary affliction is preparing for us an eternal weight of glory beyond all comparison, as we look not to the things that are seen but to the things that are unseen. For the things that are seen are transient, but the things that are unseen are eternal. (2 Corinthians 4:16–18)

In other words, the temporary physical privation Paul and his partners experienced pointed to an eternal spiritual prosperity for Paul, his partners, and his hearers/readers. Their privations helped them all look beyond the transient seen to the eternal, infinitely prosperous unseen promised to them, and their inner selves were renewed in an unconquerable hope that could never be disappointed here, no matter what happened on earth.

But their earthly privations were more than pointers to a future prosperity. They were producing some of that future prosperity. That’s what Paul meant in verse 17, when he said that our seen light and momentary afflictions — like being perplexed, persecuted, and struck down (2 Corinthians 4:8–9) — are preparing for us an unseen incomparable weight of glory. The Greek word Paul used (katergazetai), translated “is preparing,” means to produce or bring about.

Paul knew Jesus clearly taught that the privations his followers endured for his sake and in faith would be abundantly rewarded by the Father (Mark 10:28–30). He knew our faithful suffering would be rewarded. But Paul also knew that the one great reward worth having more than any other was Christ himself forever (Philippians 3:8–11), and that our faithful sufferings would be most rewarded with that Reward.

A Prosperity That’s Better Than Life

That was the reward David also desired most (Psalm 23:6; 27:4). It’s why he was able to say in that dry and weary wilderness, with death nipping at his heels, that God’s steadfast love was better than life to him. David did not love his earthly prosperity more than he loved God, or more than God’s purposes, or more than God’s promises.

David learned what his greatest prosperity was, where his most valuable treasures were laid up, through his many wilderness wanderings, his many desperate moments, and his many persecutions. David’s privations, far more than his earthly prosperity, prepared for him an incomparable weight of glory. And because of them, he has pointed the rest of us to true prosperity for three thousand years.

The true, biblical, Christian gospel is a prosperity gospel. It is discovering a treasure of such surpassing worth that those who find it simply aren’t willing to settle for the mud-pie prosperity of this fallen world. It is a treasure that is better than life, and nothing demonstrates the value of a treasure more than what we are willing to suffer and lose in order to have it (Matthew 13:44; Philippians 3:7–8). And this treasure is discovered and experienced far more often in the field of earthly privation than earthly prosperity.

Jon Bloom's Blog

- Jon Bloom's profile

- 110 followers