Terry Teachout's Blog, page 254

February 15, 2011

TT: O tempora, o mores!

William Schuman, the composer of New England Triptych, appears as a mystery guest on What's My Line? in 1962:

Published on February 15, 2011 05:00

TT: Almanac

"When I get sick of what men do, I have only to walk a few steps in another direction to see what spiders do. Or what the weather does. This sustains me very well indeed."

E.B. White, letter to Carrie A. Wilson (May 1, 1951)

E.B. White, letter to Carrie A. Wilson (May 1, 1951)

Published on February 15, 2011 05:00

February 14, 2011

TT: George Shearing, R.I.P.

George Shearing, who in his day was both an immensely popular and an impeccably tasteful jazz pianist, died this morning at the age of ninety-one. I wrote at length about him for the New York Times in 2002. That

piece

was quoted in this morning's Associated Press

obituary

. Here's the relevant part:

He never did.

* * *

.

The George Shearing Quintet plays Denzil Best's "Move":

Bad habits die hard, but now that ''crossover'' is no longer a dirty word, the time has come for George Shearing to be acknowledged not as a commercial purveyor of bop-and-water, but as an exceptionally versatile artist who has given pleasure to countless listeners for whom such critical hair-splitting is irrelevant. At 82, he is still active, still witty and still playing piano with the same luminous touch that put him on the map back when 52nd Street was lined with grubby little nightclubs instead of jumbo office towers. May he never stop swinging.

He never did.

* * *

.

The George Shearing Quintet plays Denzil Best's "Move":

Published on February 14, 2011 19:52

February 13, 2011

TT: Almanac

"Humor can be dissected, as a frog can, but the thing dies in the process and the innards are discouraging to any but the pure scientific mind."

E.B. White, preface to A Subtreasury of American Humor

E.B. White, preface to A Subtreasury of American Humor

Published on February 13, 2011 16:58

TT: Lashed to the mast

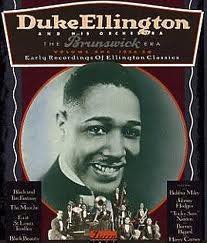

Early on Saturday evening I finished editing the 16,000-word, seventy-one-page first draft of the fourth chapter of my Duke Ellington biography. (To give you some perspective on this piece of work, my Wall Street Journal drama columns are about 850 words long.) This section of the book takes Ellington from the fall of 1926, when he made his first electrical recordings and signed a management contract with Irving Mills, to the summer of 1929, when he made his Broadway debut.

Early on Saturday evening I finished editing the 16,000-word, seventy-one-page first draft of the fourth chapter of my Duke Ellington biography. (To give you some perspective on this piece of work, my Wall Street Journal drama columns are about 850 words long.) This section of the book takes Ellington from the fall of 1926, when he made his first electrical recordings and signed a management contract with Irving Mills, to the summer of 1929, when he made his Broadway debut.It was a long, backbreakingly complicated chapter to write, not merely because it deals with one of the most eventful and consequential periods of Ellington's life, but because I also had to write concise character sketches of Mills and seven key players in the Ellington band who were hired during this time: Barney Bigard, Wellman Braud, Harry Carney, Johnny Hodges, Freddie Jenkins, Tricky Sam Nanton, and Cootie Williams. In addition, I had to describe the Cotton Club, where Ellington's band made its debut at the end of 1927, and write extended discussions of three important Ellington recordings, "East St. Louis Toodle-Oo," "Black and Tan Fantasy," and "Creole Love Call."

To pack so much material into the span of a single chapter is an alarmingly difficult conceptual feat. To do it without having the results seem dry and fact-crammed is more difficult still. In order to avoid the latter fate, I devoted a couple of pages to a description of what America was like in 1927, and I confess to liking the results:

To pack so much material into the span of a single chapter is an alarmingly difficult conceptual feat. To do it without having the results seem dry and fact-crammed is more difficult still. In order to avoid the latter fate, I devoted a couple of pages to a description of what America was like in 1927, and I confess to liking the results:Nineteen twenty-seven was a rich year for American culture. It was the year of Show Boat, The General, Elmer Gantry, Irving Berlin's "Blue Skies," Aaron Copland's jazz-flavored Piano Concerto, Stuart Davis' equally jazzy "Egg Beater No. 1," and the last volume of H.L. Mencken's Prejudices. Charles Lindbergh had flown from New York to Paris in May, and Sacco and Vanzetti were executed in August. For those who knew how to make it, there was money to burn: Babe Ruth earned $70,000 playing for the Yankees, the equivalent of $857,000 today. (A laborer at Fisher Body's assembly plant in Flint, Michigan, made $1,783.) You could buy a loaf of bread for nine cents, a copy of Time for fifteen cents, a raccoon coat for $40, an Atwater Kent radio for $70, or a Model T for $290. Radio was big, but the phonograph was bigger: one hundred million records were sold in America, and among them were Louis Armstrong's "Potato Head Blues" and Bix Beiderbecke's "Singin' the Blues."The entertainment listings in the "Goings On About Town" section of the December 3 issue of The New Yorker read like a magic carpet ride. On Broadway Katharine Cornell was starring in Somerset Maugham's The Letter, Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne in George Bernard Shaw's The Doctor's Dilemma, and Fred and Adele Astaire in George and Ira Gershwin's Funny Face. If you felt like taking in a movie, you could check out The Jazz Singer, which had opened in October and was still going strong, though the magazine's anonymous critic gave it a mixed notice: "Al Jolson superb in the Vitaphone which accompanies this dull movie." Alfred Stieglitz was showing works by John Marin, America's first cubist painter, at Room 303, the photographer's modernism-friendly art gallery. Among the books reviewed in the magazine that week was Thornton Wilder's The Bridge of San Luis Rey, and the list of recommended new titles for Christmas shoppers included Willa Cather's Death Comes for the Archbishop, Ernest Hemingway's Men Without Women, and P.G. Wodehouse's Carry On, Jeeves.

"Goings On About Town," however, had not yet discovered the Cotton Club. The only Harlem nightspots mentioned in the December 3 issue, and for many more issues to come, were Barron's Exclusive Club, Small's Paradise, and Club Ebony. "The later the better, and do not dress," the magazine advised readers interested in visiting Harlem. A week later Lois Long, the wife of society cartoonist Peter Arno and the cabaret correspondent of The New Yorker, whose "Tables for Two" column she wrote under the fey pseudonym of "Lipstick," announced that "I am mad at Harlem. It is getting too refined. All the Harlemites are getting a little ashamed of the Black Bottom, that quaint old native dance handed down by levee-working grandfathers...Give me a Holy Rollers meeting any time. Or Small's. Or, possibly, the Ebony. If I were you, I'd avoid those little places where the 'real Harlemites' go."

The New Yorker had only just started to cover "Popular Records" in 1927, and the reviewer who wrote about them seemed not to have heard any black musicians. (He favored Paul Whiteman, Ben Bernie, and the Clicquot Club Eskimos.) Indeed, one could read The New Yorker for month after month without running across a single hint that black people of any kind existed, though a couple of weeks later a poetess named Frances Park opined on "Harlem 1927": A slim brown girl/With a heart of flame/Will never admit/She feels it shame/To be dark of skin/With ink-black hair,/Nor wish she were/As the white folk there. But "Lipstick," unlike her colleagues, knew her way around certain parts of Harlem, and she also knew that certain of its nightspots were friendlier than others to visitors from downtown. In due course "Goings On About Town" started advising its readers to stick to Connie's Inn and Small's unless you have "a friend who'll personally conduct you." A week later, the advice was more candid: "Better find a friend who knows his way about; the liveliest places don't welcome unknown whites." By then, the "Popular Records" columnist had unbent enough to recommend a coupling of "Somebody Stole My Gal and "Thou Swell" recorded by "Bix Beiderberg [sic] and His Gang" in language that made his musical predilections obvious: "Hot and lusty interpretations which still are not chaotic."

That part was fun to write, though it was also damned hard work.

If I had to guess, I'd say that I've now written between a fourth and a third of the book, not counting source notes. My schedule for the next couple of weeks is awfully hectic, so I doubt that I'll be plunging straight into the next chapter. But I'm far ahead of schedule, and I mean to stay that way.

By the way, I also saw two shows, wrote two drama columns, paid a visit to an artists' colony, made several fixes to the libretto for Danse Russe, and turned fifty-five last week. I did, however, take yesterday off!

* * *

The Ellington band plays "Old Man Blues" in Check and Double Check, filmed in 1930. The trumpet soloist is Freddie Jenkins:

Published on February 13, 2011 16:58

February 10, 2011

TT: Almanac

"This country is merciless to good small talents. A writer who doesn't take chances and swing for the fences (whether or not he has a prayer of reaching them) is less than a man."

Wilfrid Sheed, review of Letters of E.B. White

Wilfrid Sheed, review of Letters of E.B. White

Published on February 10, 2011 16:38

TT: You'll just have to wait

If you're curious, I explain at the end of today's Wall Street Journal drama column why we didn't review Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark this week. Here's what I wrote:

More next month....

Contrary to any impression you might have garnered from the reviews that appeared on Tuesday in other publications, "Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark" is still in public previews, is still being rehearsed and is still undergoing changes, some of which may prove to be significant. The official opening date is Mar. 15. Critics will not be invited to see it until a few days prior to that date, after the show has assumed its final form and has been "frozen" by Julie Taymor, the director and co-author. In keeping with this long-standing professional courtesy, I have not seen "Spider-Man" and won't do so until the show is officially frozen. My review will run on Mar. 16.

More next month....

Published on February 10, 2011 16:38

TT: I'd rather be in Philadelphia

In this morning's Wall Street Journal I report on a Phildelphia show, the Arden Theatre's revival of Eugene O'Neill's

A Moon for the Misbegotten

. Here's an excerpt.

* * *

Six decades after his death, Eugene O'Neill is still widely considered to be America's greatest playwright--but productions of his major plays are growing fewer and farther between. Only four O'Neill revivals have been mounted on Broadway in the past decade, and major regional productions aren't much more common. Hence Philadelphia's Arden Theatre is swimming upstream by performing "A Moon for the Misbegotten," O'Neill's last completed play, which I haven't seen since the 2007 Broadway version that starred Kevin Spacey and Eve Best. I liked it well enough then, but I liked it a lot more in Philadelphia.

Why has O'Neill gone out of fashion? Because his plays are usually long-winded and almost always devoid of poetry. His characters talk and talk (the original production of "Mourning Becomes Electra" ran for six hours) without ever getting around to saying anything memorable. I looked O'Neill up in "The Yale Book of Quotations" the other day and found just five entries, only four of which are from his plays and the most famous of which is remembered because it was the first line that Greta Garbo ever spoke on screen: "Gimme a whiskey--ginger ale on the side. And don't be stingy, baby." That's not what I call quotable, much less poetic.

"A Moon for the Misbegotten" suffers from both of these problems, and by all rights they ought to kill it stone dead. Not only does the play open with an hour and a half of wholly unnecessary exposition, but there's not a quotable line in it--not even in the second half, which is when O'Neill finally steps on the gas pedal and gets moving. But what started out as a stage-Irish yukfest then turns into a deeply compassionate study of a drunken ex-actor (Eric Hissom) and a poor, unattractive farm girl (Grace Gonglewski) who are too proud to let themselves love one another, and almost before you know it you find yourself caught up in their plight.

"A Moon for the Misbegotten" suffers from both of these problems, and by all rights they ought to kill it stone dead. Not only does the play open with an hour and a half of wholly unnecessary exposition, but there's not a quotable line in it--not even in the second half, which is when O'Neill finally steps on the gas pedal and gets moving. But what started out as a stage-Irish yukfest then turns into a deeply compassionate study of a drunken ex-actor (Eric Hissom) and a poor, unattractive farm girl (Grace Gonglewski) who are too proud to let themselves love one another, and almost before you know it you find yourself caught up in their plight.

Ms. Gonglewski is by all accounts one of Philadelphia's top actors, and in "A Moon for the Misbegotten" you can see how she got that reputation. Performing in a subtly padded costume that makes her look much more broad-beamed than she is in real life, she plays the part of Josie Hogan with a force and authority worthy of the way that O'Neill describes her character in the play's stage directions: "She is so oversize for a woman that she is almost a freak...She is more powerful than any but an exceptionally strong man, able to do the manual labor of two ordinary men. But there is no mannish quality about her. She is all woman." Ms. Best's performance on Broadway was phenomenal, but Ms. Gonglewski doesn't have to make any apologies: She comes on like a typhoon....

* * *

Read the whole thing here .

* * *

Six decades after his death, Eugene O'Neill is still widely considered to be America's greatest playwright--but productions of his major plays are growing fewer and farther between. Only four O'Neill revivals have been mounted on Broadway in the past decade, and major regional productions aren't much more common. Hence Philadelphia's Arden Theatre is swimming upstream by performing "A Moon for the Misbegotten," O'Neill's last completed play, which I haven't seen since the 2007 Broadway version that starred Kevin Spacey and Eve Best. I liked it well enough then, but I liked it a lot more in Philadelphia.

Why has O'Neill gone out of fashion? Because his plays are usually long-winded and almost always devoid of poetry. His characters talk and talk (the original production of "Mourning Becomes Electra" ran for six hours) without ever getting around to saying anything memorable. I looked O'Neill up in "The Yale Book of Quotations" the other day and found just five entries, only four of which are from his plays and the most famous of which is remembered because it was the first line that Greta Garbo ever spoke on screen: "Gimme a whiskey--ginger ale on the side. And don't be stingy, baby." That's not what I call quotable, much less poetic.

"A Moon for the Misbegotten" suffers from both of these problems, and by all rights they ought to kill it stone dead. Not only does the play open with an hour and a half of wholly unnecessary exposition, but there's not a quotable line in it--not even in the second half, which is when O'Neill finally steps on the gas pedal and gets moving. But what started out as a stage-Irish yukfest then turns into a deeply compassionate study of a drunken ex-actor (Eric Hissom) and a poor, unattractive farm girl (Grace Gonglewski) who are too proud to let themselves love one another, and almost before you know it you find yourself caught up in their plight.

"A Moon for the Misbegotten" suffers from both of these problems, and by all rights they ought to kill it stone dead. Not only does the play open with an hour and a half of wholly unnecessary exposition, but there's not a quotable line in it--not even in the second half, which is when O'Neill finally steps on the gas pedal and gets moving. But what started out as a stage-Irish yukfest then turns into a deeply compassionate study of a drunken ex-actor (Eric Hissom) and a poor, unattractive farm girl (Grace Gonglewski) who are too proud to let themselves love one another, and almost before you know it you find yourself caught up in their plight.Ms. Gonglewski is by all accounts one of Philadelphia's top actors, and in "A Moon for the Misbegotten" you can see how she got that reputation. Performing in a subtly padded costume that makes her look much more broad-beamed than she is in real life, she plays the part of Josie Hogan with a force and authority worthy of the way that O'Neill describes her character in the play's stage directions: "She is so oversize for a woman that she is almost a freak...She is more powerful than any but an exceptionally strong man, able to do the manual labor of two ordinary men. But there is no mannish quality about her. She is all woman." Ms. Best's performance on Broadway was phenomenal, but Ms. Gonglewski doesn't have to make any apologies: She comes on like a typhoon....

* * *

Read the whole thing here .

Published on February 10, 2011 16:38

February 9, 2011

TT: Almanac

"Jean's undoing, in my view, was nothing as humdrum as booze or tobacco or malnourishment, but a deadly streak of passivity of a kind that sometimes goes with perfectionism, and which I think she loathed in herself."

Wilfrid Sheed, "Miss Jean Stafford"

Wilfrid Sheed, "Miss Jean Stafford"

Published on February 09, 2011 19:51

TT: If this doesn't make you laugh, you're dead

Louis Armstrong and Rex Harrison sing Cole Porter's "Now You Has Jazz" in 1957:

(No, I didn't know about this clip when I wrote Pops!)

(No, I didn't know about this clip when I wrote Pops!)

Published on February 09, 2011 19:51

Terry Teachout's Blog

- Terry Teachout's profile

- 45 followers

Terry Teachout isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.