Terry Teachout's Blog, page 166

April 25, 2012

TT: So you want to see a show?

Here's my list of recommended Broadway, off-Broadway, and out-of-town shows, updated weekly. In all cases, I gave these shows favorable reviews (if sometimes qualifiedly so) in The Wall Street Journal when they opened. For more information, click on the title.

BROADWAY:

• Anything Goes (musical, G/PG-13, mildly adult subject matter that will be unintelligible to children, closes Sept. 9, reviewed here)

• The Best Man (drama, PG-13, closes July 1, nearly all performances sold out last week, reviewed here)

• Death of a Salesman (drama, PG-13, unsuitable for children, all performances sold out last week, closes June 2, reviewed here)

• Evita (musical, PG-13, nearly all performances sold out last week, reviewed here)

• Godspell (musical, G, suitable for children, reviewed here)

• How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying (musical, G/PG-13, perfectly fine for children whose parents aren't actively prudish, reviewed here)

• Once (musical, G/PG-13, reviewed here)

• Other Desert Cities (drama, PG-13, adult subject matter, closes June 17, reviewed here)

• Venus in Fur (serious comedy, R, adult subject matter, closes June 17, reviewed here)

OFF BROADWAY:

• Avenue Q (musical, R, adult subject matter and one show-stopping scene of puppet-on-puppet sex, reviewed here)

• The Fantasticks (musical, G, suitable for children capable of enjoying a love story, reviewed here)

• 4000 Miles (drama, PG-13, closes June 17, reviewed here)

• Million Dollar Quartet (jukebox musical, G, off-Broadway remounting of Broadway production, original run reviewed here)

• Saint Joan (drama, G/PG-13, unsuitable for children, extended through May 13, reviewed here)

• Tribes (drama, PG-13, closes Sept. 2, reviewed here)

OGIC: Knowing beasts

Two-thirds of the way through J. F. Powers's novel Morte D'Urban , I'm wondering where this book has been all my life. Father Urban, the ambitious Clementine priest at its center, surprised me from the beginning. He treats his vocation, Terry wrote in the New Criterion years ago, "precisely as he would any other job: with one eye firmly fixed on the main chance." He doesn't suffer his less worldly, less canny colleagues gladly, and Powers does a wonderful job of satirizing both his main character and those around him as they appear through Father Urban's ever appraising eyes.

I've been laughing helplessly through the book, but have also read far enough in Terry's essay to know that this comedy is headed somewhere serious. Not having reached that point yet, I want to pull out for your amusement something very small and inconsequential in the book, and very charming: dogs.

I've been laughing helplessly through the book, but have also read far enough in Terry's essay to know that this comedy is headed somewhere serious. Not having reached that point yet, I want to pull out for your amusement something very small and inconsequential in the book, and very charming: dogs.In what seems to me a purely playful impulse--though for such a meticulous writer, I wonder whether something more is going on--Powers outright anthropomorphizes the three dogs I've encountered so far in Morte D'Urban. In a few quick strokes, he makes them seem to observe the human folly playing out in front of them with bemusement, as you might imagine some of the dogs drawn by James Thurber or George Booth doing. Here, they even (sort of) speak. In some passages you get the sense they are secretly running the show. I find them among the most memorable people in the book.

The first dog to appear remains unnamed. It resides in the station at Duesterhaus, the Minnesota outpost to which Father Urban has been banished from the place he deems his proper setting, Chicago. On arrival, Father Urban instantly gets a taste of his new isolation:

The station agent, writing at his desk, seemed unaware of [Father Urban]. An old dog lying behind the counter woke up and gave him a look that said, Can't you see he's working on his report?

"I'd like to call a taxi, if I may," said Father Urban, giving the town the benefit of a doubt, and then he waited.

Presently the agent got up and came to the counter. He pushed the telephone at Father Urban and tossed him a thin directory. "Cost you a dime to call," he said.

The dog opened its eyes, as if it wanted to see how Father Urban would take the bad news.

Father Urban put a dime on the counter.

The dog closed its eyes.

The next dog, Rex, belongs to a local man who sells the land for a golf course to the Clementine order, a deal put together by Father Urban with the backing of Billy Cosgrove, a patron from Chicago. On his first visit, "Father Urban found Mr. Hanson and the dog at home," Powers writes. "The dog seemed to recognize him, but Mr. Hanson didn't, and so Father Urban introduced himself."

The next dog, Rex, belongs to a local man who sells the land for a golf course to the Clementine order, a deal put together by Father Urban with the backing of Billy Cosgrove, a patron from Chicago. On his first visit, "Father Urban found Mr. Hanson and the dog at home," Powers writes. "The dog seemed to recognize him, but Mr. Hanson didn't, and so Father Urban introduced himself."The black dog largely takes over the situation when Father Urban arrives with several associates on his next visit.

Mr. Hanson and the truck were elsewhere, but Rex showed the party around the farm. Most of the time they walked in silence, Mr. Robertson occasionally raising small binoculars to his eyes. When they were back where they'd started from a half hour before, Billy said:

"Well?"

Mr. Robertson gave the frozen ground, which he'd been eying from all angles, from close up and afar, one last kick, and said:

"I don't see why not."

"Let's make it a standout course," said Billy.

As they were getting into the cars, Monsignor Renton now alone in his, Rex spoke to them, and a moment later Mr. Hanson and the truck appeared.

Billy, who had been told about Father Urban's accident, said to Mr. Hanson: "Paid that bill yet--that collision bill?"

"Yar, I got to pay it," said Mr. Hanson.

"Yar," said Rex to Monsignor Renton.

It's worth noting that the buyers eventually negotiate for Hanson to throw in the dog with the land, in a conversation Rex follows closely. Later an "aged Airedale" named Frank turns up, the color of "dark chocolate that had melted and hardened and lightened," but I'll let you discover him yourself if you happen to pick up the book--which you really, really should. In the meantime, I'll try to find out whether Powers was a dog owner, and what his dogs thought about it all.

TT: Alsop's foibles

* * *

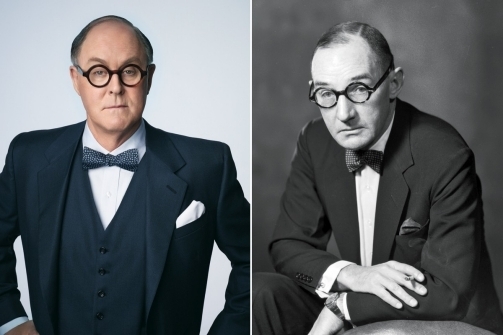

David Auburn has written a pretty good play about an immensely promising subject. It's the gap between expectation and result that makes "The Columnist" a disappointment, though there's nothing at all disappointing about the Manhattan Theatre Club's production, cleanly and clearly staged by Daniel Sullivan, or John Lithgow's elegantly flamboyant performance as Joseph Alsop, the once-celebrated newspaper columnist who coined the phrase "domino theory." A blue-blooded WASP who supported the Vietnam War long after most of his fellow journalists jumped ship, Alsop got into boiling-hot water when the KGB found out in 1957 that he was also a closeted homosexual and attempted to blackmail him. "The Columnist" revolves around these two facts, but Mr. Auburn devotes far more time and energy to the first one, and my guess is that by intermission you'll be thinking that he should have written his play the other way around.

David Auburn has written a pretty good play about an immensely promising subject. It's the gap between expectation and result that makes "The Columnist" a disappointment, though there's nothing at all disappointing about the Manhattan Theatre Club's production, cleanly and clearly staged by Daniel Sullivan, or John Lithgow's elegantly flamboyant performance as Joseph Alsop, the once-celebrated newspaper columnist who coined the phrase "domino theory." A blue-blooded WASP who supported the Vietnam War long after most of his fellow journalists jumped ship, Alsop got into boiling-hot water when the KGB found out in 1957 that he was also a closeted homosexual and attempted to blackmail him. "The Columnist" revolves around these two facts, but Mr. Auburn devotes far more time and energy to the first one, and my guess is that by intermission you'll be thinking that he should have written his play the other way around."The Columnist" starts off, so to speak, with a bang. In the first scene, we see Alsop in bed with Andrei (Brian J. Smith), the young Russian whose job it is to lure him into the clutches of the KGB. But instead of capitalizing on that exciting opening, Mr. Auburn embarks on a stodgy tour d'horizon of the second half of Alsop's life. We meet Stewart (Boyd Gaines), his younger brother, erstwhile writing partner and lifelong rival; Susan Mary (Margaret Colin), the widowed society lady with whom he entered into an uneasy mariage blanc in 1961, and Abigail (Grace Gummer), Susan's daughter; and an unrecognizably fictionalized version of David Halberstam (Stephen Kunken), the earnest young reporter who opposed the Vietnam War as ardently as Alsop backed it.

"The Columnist" covers an 11-year span of time, which is too much for Mr. Auburn to fit gracefully into a two-hour play. In short order it turns into a pageant--the Kennedy inauguration, a side trip to Vietnam, the Kennedy assassination, Joe's divorce, Stewart's death, even an antiwar protest. It would have taken a Tom Stoppard to shape this endless succession of events into a dynamically theatrical plot. Mr. Auburn, for all his skill, lacks that kind of flair, nor does he have Mr. Stoppard's knack for bringing historical figures to life....

Mr. Auburn finds his footing in the more personal parts of "The Columnist," especially the well-written scenes in which Alsop interacts with his wife and stepdaughter (who are portrayed with winning sensitivity by Ms. Colin and Ms. Gummer). He also has Mr. Lithgow in his corner, which makes all the difference in the world. Yes, Mr. Lithgow's Alsop is a slightly over-arch caricature--the real Joe Alsop played it rather closer to the vest than that--but the grandiose panache with which he coaches Abigail for a Latin exam or banters with his Soviet bedmate about the evils of communism is impossible to resist....

* * *

Read the whole thing here .

To see Brian Lamb interviewing Joseph Alsop on C-Span in 1984, go here .

April 24, 2012

TT: Snapshot

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday and Wednesday.)

TT: Almanac

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Faust, Part II (trans. Bayard Taylor)

April 23, 2012

TT: The lighter side of cancer

* * *

One of the reasons why we expect so much out of Broadway shows is that they cost so much to see. Nicky Silver's "The Lyons," which transferred to Broadway this week, is a clever little dysfunctional-family comedy that contains at least twice its fair share of laughs. Though it's more than a bit of a mess, "The Lyons" has its moments, and Linda Lavin, the star, is in sensational form. Off Broadway, that amounted to a passable bargain--but is it really worth $126.50 to see an amusing but inconsistent show? All I can tell you is that despite its extreme unevenness, "The Lyons" is never boring.

Part of what's wrong with "The Lyons" is that it feels more like a medley than a play. The first act is a skit about a Jewish family whose members despise one another. Ben (Dick Latessa), the father, is suffering from one of those extra-special symptom-free varieties of theatrical cancer that kill you in a week or two without causing any visible discomfort. Rita (Ms. Lavin), the mother, is a gleeful gargoyle who can't wait for him to expire so that she can redecorate their house ("Do you think plaid is too casual?"). As for the kids, Lisa (Kate Jennings Grant), the daughter, is an alcoholic divorcée, while Curtis (Michael Esper), the son, is gay and unemployed. Put them all in a hospital room and you get an hour's worth of horrifically malicious one- and two-liners: "You know, there's a very nice young man down the hall, Leonard something, end stages of lymphoma--and I think he's Jewish!" Imagine a middle-period Neil Simon play rewritten by Christopher Durang and you'll get the idea.

Part of what's wrong with "The Lyons" is that it feels more like a medley than a play. The first act is a skit about a Jewish family whose members despise one another. Ben (Dick Latessa), the father, is suffering from one of those extra-special symptom-free varieties of theatrical cancer that kill you in a week or two without causing any visible discomfort. Rita (Ms. Lavin), the mother, is a gleeful gargoyle who can't wait for him to expire so that she can redecorate their house ("Do you think plaid is too casual?"). As for the kids, Lisa (Kate Jennings Grant), the daughter, is an alcoholic divorcée, while Curtis (Michael Esper), the son, is gay and unemployed. Put them all in a hospital room and you get an hour's worth of horrifically malicious one- and two-liners: "You know, there's a very nice young man down the hall, Leonard something, end stages of lymphoma--and I think he's Jewish!" Imagine a middle-period Neil Simon play rewritten by Christopher Durang and you'll get the idea.That's a nice start, but Mr. Silver skids off the road after intermission. The second act of "The Lyons" opens with a scene that appears to have been lifted from some other show (alas, it can't be described without giving away the game). Then we return to the hospital for a grand finale that staggers into seriousness and gets all gooey....

Even if the world had been breathlessly awaiting yet another Broadway revival of "A Streetcar Named Desire," Emily Mann's mediocre new multi-racial version of Tennessee Williams' most familiar play wouldn't have been anywhere near good enough to pass muster. Most of the acting, especially by Blair Underwood as Stanley and Nicole Ari Parker as Blanche, is about what you'd expect from a TV movie, and Ms. Mann's predictable-looking staging is devoid of anything remotely approaching a convincing sense of time or place....

The musical version of "Ghost," Jerry Zucker's 1990 film about how a cute young murder victim saves the life of his cute young widow by haunting a fraudulent but funny medium, belongs not on Broadway but in the Smithsonian Institution. Not only would such a transfer free up a valuable piece of real estate, but it might also help historians of the future to understand what went wrong with the Broadway musical in the 21st century....

The cast is a box of stale Twinkies. The songs, by Dave Stewart, Glen Ballard and Mr. Rubin, are just the sort of thing you'd expect to hear on a low-budget knockoff of "American Idol." If that sounds good to you, get out the steel wool and clean your ears....

* * *

Read the whole thing here .

TT: Lookback

From 2006:

From 2006:I was sitting on a rowing machine at the gym the other day when I looked up at the bank of television sets just above my head and saw Peri Gilpin (remember her?) chatting earnestly with Tony Danza (remember him?) about her latest venture, a Lifetime TV movie about child abuse. It was as if I'd inadvertently glanced through an astral portal into a parallel universe inhabited exclusively by second-tier ex-celebrities....

Read the whole thing here .

TT: Almanac

Cesare Pavese, This Business of Living

April 22, 2012

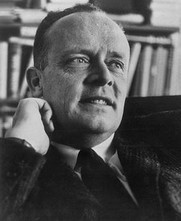

TT: The other O'Connor

* * *

The O'Connor everyone remembers is Flannery, who wrote herself into the history of American literature by looking at the poor white Protestants of her native Georgia through the X-ray glasses of Roman Catholic dogma. But there was another Catholic novelist named O'Connor at work in the Fifties and Sixties, and for a time he was both better known and vastly more popular than his opposite number.

Edwin O'Connor first rang the gong of success with The Last Hurrah, a 1956 novel about an aging Boston politician that added a phrase to the English language and made the man who coined it rich and famous. Like his opposite number in the Deep South, O'Connor was a devout, wholly orthodox Catholic, a daily communicant who stuck close to home, settling in Boston and writing about the people whom he saw there every day. But unlike the prickly author of Wise Blood and A Good Man Is Hard to Find, the other O'Connor, who died in 1968, had the gift of immediate accessibility, and readers in every corner of the land reveled in his stories of Irish-American life in mid-century New England. The Edge of Sadness, his 1961 tale of an alcoholic priest, was chosen by the Book-of-the-Month Club, condensed by Reader's Digest, and awarded a Pulitzer Prize. Not surprisingly, it was also one of the top ten best sellers of the year, sharing the list with The Agony and the Ecstasy, Franny and Zooey, and To Kill a Mockingbird.

Edwin O'Connor first rang the gong of success with The Last Hurrah, a 1956 novel about an aging Boston politician that added a phrase to the English language and made the man who coined it rich and famous. Like his opposite number in the Deep South, O'Connor was a devout, wholly orthodox Catholic, a daily communicant who stuck close to home, settling in Boston and writing about the people whom he saw there every day. But unlike the prickly author of Wise Blood and A Good Man Is Hard to Find, the other O'Connor, who died in 1968, had the gift of immediate accessibility, and readers in every corner of the land reveled in his stories of Irish-American life in mid-century New England. The Edge of Sadness, his 1961 tale of an alcoholic priest, was chosen by the Book-of-the-Month Club, condensed by Reader's Digest, and awarded a Pulitzer Prize. Not surprisingly, it was also one of the top ten best sellers of the year, sharing the list with The Agony and the Ecstasy, Franny and Zooey, and To Kill a Mockingbird.Such popularity is not easily forgiven in certain cultural circles. Edmund Wilson, who knew O'Connor and admired him greatly, observed apropos of The Edge of Sadness that "a literary intellectual objects to nothing so much as a best-selling book that also possesses real merit." Small wonder that the book in question, like its author, is now all but forgotten...

Hugh Kennedy, the narrator of The Edge of Sadness, is a fifty-five-year-old priest from a city not unlike Boston who has just climbed back up from the end of his rope. Sent into an emotional tailspin by the death of his beloved father, he takes to drink and is sent to an Arizona retreat for wayward priests, there to grapple with a spiritual emptiness that has left him vulnerable to depression in the middle of life....

The self-effacing Father Kennedy starts off by informing the reader that the story we are about to hear is not about him: "I am in it--good heavens, I'm in it to the point of almost never being out of it!--but the story belongs, all of it, to the Carmodys, and my own part, while substantial enough, was never really of any great significance at all." The Carmodys are a well-to-do family that Father Kennedy knew and loved as a boy and whose irascible octogenarian patriarch takes a renewed interest in him after he returns to Boston to pick up the pieces of his life. Charlie Carmody and his children, each one representing a different facet of the immigrant experience, are drawn with striking vividness and sympathy, so much so that it is not until well into The Edge of Sadness that we realize that the author has contrived to throw us off the scent: his real subject, it turns out, is not the Carmodys but Father Kennedy's painful journey from the slough of despond to the brink of renewal....

In The Living Novel, V.S. Pritchett praised those novelists "who are not driven back by life, who are not shattered by the discovery that it is a thing bounded by unsought limits, by interests as well as by hopes, and that it ripens under restriction. Such writers accept. They think that acceptance is the duty of a man." Pritchett was talking about Walter Scott, but he could just as well have had The Edge of Sadness in mind, for it is above all a story of acceptance, a portrait of a group of men and women who find themselves forced at last to face the fact that their dreams will not come true....

In The Living Novel, V.S. Pritchett praised those novelists "who are not driven back by life, who are not shattered by the discovery that it is a thing bounded by unsought limits, by interests as well as by hopes, and that it ripens under restriction. Such writers accept. They think that acceptance is the duty of a man." Pritchett was talking about Walter Scott, but he could just as well have had The Edge of Sadness in mind, for it is above all a story of acceptance, a portrait of a group of men and women who find themselves forced at last to face the fact that their dreams will not come true....Yet the closing pages of The Edge of Sadness are also suffused with the warm glow of possibility, and never for a moment does it have the factitious feel of a confidence trick played by a best-selling author determined to send his audience home happy. For even though Father Kennedy continues to believe in "the essential goodness of man," he also knows that "only a fool can look around him and smile serenely in unwatered optimism." He knows, too, that the spiritual dryness that came close to destroying him can only be held at bay if he immerses himself in the daily life of his shabby parish, trading the easy familiarity of his old existence for the awareness that

while something was over forever, something else had just begun--and that if the new might not seem the equal of the old, that might be because the two were not to be compared....that something might be ahead that grew out of the past, yes, but was totally different, with its own labors and rewards, that it might be deeper and fuller and more meaningful than anything in the past.

After The Edge of Sadness, Edwin O'Connor published only one more full-scale novel, All in the Family, which was as popular and artistically successful as its predecessors. But the pace of change in America had sped up between 1961 and 1966, and a new generation of critics who had cut their teeth on high modernism now found little to like in an unselfconsciously old-fashioned storyteller who worshipped the gods of directness and simplicity. Two years after he died, Edmund Wilson and Arthur Schlesinger put together The Best and the Last of Edwin O'Connor, a well-meant anthology that sought in vain to keep his memory green. Denis Donoghue, who wrote about it in The New York Review of Books, declared that O'Connor's oeuvre was "a public success but still, in the artistic sense, incomplete, his possibilities unfulfilled."

Perhaps--but to read The Edge of Sadness today is to doubt the finality of that reasonable-sounding judgment. I thought that it was an extraordinarily fine book when I first read it a quarter-century ago, and now that I am almost as old as Father Hugh Kennedy, I think it better still. Few American novels have done a more honest job of telling how it feels for a man to come to the middle of life's journey, and even fewer have the power to fill their readers with a sense of hope strong enough to be felt not merely in the bright light of day but in the middle of the dark night of the soul.

TT: Just because (in memoriam, Levon Helm)

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday and Wednesday.)

Terry Teachout's Blog

- Terry Teachout's profile

- 45 followers