Terry Teachout's Blog, page 148

July 11, 2012

TT: So you want to see a show?

Here's my list of recommended Broadway, off-Broadway, and out-of-town shows, updated weekly. In all cases, I gave these shows favorable reviews (if sometimes qualifiedly so) in The Wall Street Journal when they opened. For more information, click on the title.

BROADWAY:

• Anything Goes (musical, G/PG-13, mildly adult subject matter that will be unintelligible to children, closes Aug. 5, reviewed here)

• The Best Man (drama, PG-13, closes Sept. 9, most performances sold out last week, reviewed here)

• Evita (musical, PG-13, most performances sold out last week, reviewed here)

• Once (musical, G/PG-13, all performances sold out last week, reviewed here)

OFF BROADWAY:

• Avenue Q (musical, R, adult subject matter and one show-stopping scene of puppet-on-puppet sex, reviewed here)

• The Fantasticks (musical, G, suitable for children capable of enjoying a love story, reviewed here)

• Tribes (drama, PG-13, closes Sept. 2, reviewed here)

IN CHICAGO:

• Freud's Last Session (drama, PG-13, restaging of off-Broadway production, closes Sept. 2, reviewed here)

• A Little Night Music (musical, PG-13, closes Aug. 12, reviewed here)

CLOSING SOON ON BROADWAY:

• Anything Goes (musical, G/PG-13, mildly adult subject matter that will be unintelligible to children, closes Aug. 5, reviewed here)

CLOSING SATURDAY IN PITTSFIELD, MASS.:

• Fiddler on the Roof (musical, G, reviewed here)

CLOSING SUNDAY IN CHICAGO:

• Floyd Collins (musical, G, very problematic for children, reviewed here)

CLOSING SUNDAY IN PASADENA, CALIF.:

• Jitney (drama, PG-13, transfer of South Coast Repertory revival, original run reviewed here)

TT: When this you see

One of my fellow colonists had a piece on the program, but for me the real draw was the original thirteen-instrument version of Aaron Copland's Appalachian Spring, a masterpiece that I love with all my heart. Appalachian Spring has a special meaning for me, for it's the first piece of modern classical music to which I ever listened closely. That was all the way back in 1968, but I can recall with perfect clarity how overwhelmed I was by the sound of the transparent, luminous arpeggios with which the piece begins. I still am.

One of my fellow colonists had a piece on the program, but for me the real draw was the original thirteen-instrument version of Aaron Copland's Appalachian Spring, a masterpiece that I love with all my heart. Appalachian Spring has a special meaning for me, for it's the first piece of modern classical music to which I ever listened closely. That was all the way back in 1968, but I can recall with perfect clarity how overwhelmed I was by the sound of the transparent, luminous arpeggios with which the piece begins. I still am.Amazingly enough, though, I'd forgotten that Copland wrote Appalachian Spring at the MacDowell Colony, and somehow that fact heightened the intensity with which I received it on Friday. Though I know every bar of the piece, it sounded as new as the smell of fresh-cut grass.

I've been buttoned up tightly ever since my mother died two months ago. I thought that writing about her death would help, but all it did was put my emotions in a neatly wrapped box, and it wasn't until after I got to MacDowell that I peered inside. One of my fellow colonists gave a reading of a piece about a personal experience that had a near-exact parallel in my own life. She and I had talked about the experience a few days earlier, but I had no idea that she was planning to write about it until she started reading. Then she caught my eye, and we both burst into tears.

Not at all surprisingly, much the same thing happened to me as I listened to Appalachian Spring last Friday. I don't think it would have happened, however, if I'd been listening to an explicitly emotional piece. No, it was the coolly detached radiance of Copland's harmonies that drew out my own feelings. He didn't presume to speak for me, or anyone else: all he did was fill the air with light, and my soul responded.

After the concert I saw a young poet from MacDowell standing in a corner, scribbling urgently in a notebook. When she finished writing, I walked over to her and said, as casually as I could, "You'd never heard it before, had you?"

She looked at me, shook her head, and said, "It was so wonderful! I didn't know that music could do that!"

Three days later I received a report from Martha's Vineyard about the first public reading of the revised version of Satchmo at the Waldorf that will open at Shakespeare & Company a few weeks from now. That same night another new friend of mine read a piece that I found both powerfully moving and deeply disturbing. When she was done, I said to myself, I've got to get out of here for a little while.

It wasn't that I wanted to end my stay--far from it--but I knew that I needed to put some space between myself and the sparks thrown off by thirty-two hard-working artists who are simultaneously trying to make everything more beautiful . So I borrowed a car yesterday morning, rolled down the windows, and drove all over Peterborough and the surrounding countryside, blissfully thinking about nothing at all.

A couple of hours later I made a random turn onto a tree-lined road, and all at once I knew where I was. On my left was a fenced-off hill, and just beyond the fence were tombstones. I had come to the half-forgotten cemetery that inspired Thornton Wilder to write the graveyard scene of Our Town.

A couple of hours later I made a random turn onto a tree-lined road, and all at once I knew where I was. On my left was a fenced-off hill, and just beyond the fence were tombstones. I had come to the half-forgotten cemetery that inspired Thornton Wilder to write the graveyard scene of Our Town.It was four years ago that Mrs. T and I came to this place the morning after seeing James Whitmore play the Stage Manager in a Peterborough Players revival of Our Town. We were both overwhelmed by the visit, and I took it for granted that we would never return. Some things should only be done once. But as I looked at the gate, I felt an irresistible urge to climb the hill again, partly because I missed my wife so much and partly because...well, because it seemed appropriate.

I needed no reminder that Thornton Wilder wrote Our Town at the MacDowell Colony, for it was written in the same studio where Paul Moravec worked on The Letter, our first opera. I knew, too, that it was Copland who composed the score for the film version of Our Town. and who wanted very much to turn the play into an opera. Now that I, too, was spending my days in the same place where Copland and Wilder once worked, I thought it right to pay a second visit to the plot of land that had meant so much to both of them.

Once more I climbed the steep hill, but this time I knew what I was looking for. No sooner did I stumble across the tombstone of Samuel Stanton four years ago than I knew that Thornton Wilder had almost certainly stood where I was standing, for one of the characters in Our Town is a desperately unhappy church organist named Simon Stimson. It took me a few minutes to find the spot, and when I did, I stood in silence for a very long time, gazing at the stone.

Once more I climbed the steep hill, but this time I knew what I was looking for. No sooner did I stumble across the tombstone of Samuel Stanton four years ago than I knew that Thornton Wilder had almost certainly stood where I was standing, for one of the characters in Our Town is a desperately unhappy church organist named Simon Stimson. It took me a few minutes to find the spot, and when I did, I stood in silence for a very long time, gazing at the stone.I sat on the ground to take a picture of Samuel Stanton's grave. I haven't been in a cemetery since my mother died, I thought. But this time I didn't cry. Instead I sat in the afternoon sunshine and remembered the piercing question that Emily Webb asks at the end of Our Town: "Do any human beings ever realize life while they live it?--every, every minute?"

To which the Stage Manager replies, gently but inexorably, "The saints and poets, maybe--they do some."

I vowed to do my very best to be present for each and every moment of my blessed life, knowing even as the words formed in my head that it is in the nature of such vows to be broken. Then I walked down the hill to my car and drove back to the MacDowell Colony, there to rejoin my friends and resume my work.

* * *

Excerpts from Appalachian Spring, choreographed by Martha Graham, scored by Aaron Copland, and designed by Isamu Noguchi. This historic silent film, shot in 1944 with a single sixteen-millimeter camera, documents the original cast, including Graham as the bride, Erick Hawkins as the husband, and Merce Cunningham as the Revivalist. The soundtrack comes from Graham's 1958 film version of Appalachian Spring:

The 1940 film version of Our Town, directed by Sam Wood, scored by Aaron Copland, and starring Frank Craven, who created the role of the Stage Manager in the original 1938 Broadway production:

July 10, 2012

TT: Snapshot

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday and Wednesday.)

TT: Almanac

Alan Ayckbourn, The Crafty Art of Playmaking

July 9, 2012

TT: Lookback

From 2003:

From 2003:I told a friend of mine at lunch the other day that I thought the day would come when the producers of smart movies aimed at older viewers (i.e., anyone over 21) would bypass theatrical release altogether and market such films in more or less the same way novels are sold in bookstores. If that happens, I'll be sorry to spend less time in theaters. The enveloping experience of watching a good film in a big, dark room--and in the company of a rapt audience--is unique and irreplaceable. Alas, it's already been replaced, at least for most of us who love classic films. How many of the great movies of the past have you seen in a theater? Not many, I suspect....

Read the whole thing here .

TT: Almanac

Alan Ayckbourn, The Crafty Art of Playmaking

July 8, 2012

TT: Just because

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday and Wednesday.)

TT: Almanac

Alan Ayckbourn, The Crafty Art of Playmaking

July 5, 2012

TT: Lost illusions

* * *

When Writers' Theatre, a Chicago-area company that operates out of a 108-seat house, announced that it would try its hand at "A Little Night Music," I decided at once to go, and can now report that William Brown, who directed the company's unforgettable 2011 revival of "Heartbreak House," has outdone himself. While first-class small-house stagings of "A Little Night Music" are no longer rare, this one tops them all.

Kevin Depinet, whose long list of memorable design credits includes Chicago Shakespeare's "Follies" and the Goodman Theatre's recent revival of "The Iceman Cometh," has conjured up the simplest of sets, a two-step platform framed by elegant-looking curtains. The wide-open playing area is a pebble's throw from the audience. As a result, the members of the cast never have to exaggerate: Not only is every word audible down to the last "and/or," but every thrown-away gesture registers like a pistol shot in a walk-in closet. Mr. Brown's exemplary actors can thus scale their performances down to the point where you feel as though you're not hearing Mr. Sondheim's songs so much as overhearing them. Moreover, the sheer sexiness of "A Little Night Music" (which is, among other things, a musical about the difference between sex and love) comes across with breath-catching directness.

Kevin Depinet, whose long list of memorable design credits includes Chicago Shakespeare's "Follies" and the Goodman Theatre's recent revival of "The Iceman Cometh," has conjured up the simplest of sets, a two-step platform framed by elegant-looking curtains. The wide-open playing area is a pebble's throw from the audience. As a result, the members of the cast never have to exaggerate: Not only is every word audible down to the last "and/or," but every thrown-away gesture registers like a pistol shot in a walk-in closet. Mr. Brown's exemplary actors can thus scale their performances down to the point where you feel as though you're not hearing Mr. Sondheim's songs so much as overhearing them. Moreover, the sheer sexiness of "A Little Night Music" (which is, among other things, a musical about the difference between sex and love) comes across with breath-catching directness.Such a presentation demands a cast whose members are capable of taking full advantage of their close proximity to the audience. Mr. Brown has assembled a team that is uniformly up to the challenge. It's no slight to her colleagues, though, to say that Shannon Cochran, who plays Desirée Armfeldt, the much-bedded actress who longs for a bit of quiet comfort in her middle age, is the brightest star of the night. Ms. Cochran, who was stunning in Long Wharf Theatre's 2006 revival of "Private Lives" and the 2008 production of "The Lion in Winter" that introduced me to Writers' Theatre, proves to be a first-class singer as well. You'll never hear a more powerfully affecting performance of "Send in the Clowns," or be more touched by the way in which she chastises to the idealistic Henrik (Royen Kent) with the gentle disillusion of a woman who knows too much....

* * *

Read the whole thing here .

The trailer for Writers' Theatre's A Little Night Music:

TT: Forged in sorrow, cloven by anger

In today's Wall Street Journal "Sightings" column, I write about the Louvin Brothers. Here's an excerpt.

In today's Wall Street Journal "Sightings" column, I write about the Louvin Brothers. Here's an excerpt.* * *

Family acts have long exerted a powerful pull on audiences. Whether it's a brother-and-sister musical duo like Yehudi and Hephzibah Menuhin or a husband-and-wife acting team like Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne, it's irresistibly fascinating to see them perform together on stage. When they get along--and sometimes even when they don't--they very often give the uncanny impression of being able to think, move or sing like a single person. Alas, such acts are no longer as common in the music business as they used to be, perhaps because families aren't as close as they used to be. Nor have they ever been all that common in classical music. It is in the field of pop music that family members are far more likely to collaborate, and it is in country music that they have left the deepest mark.

Why is this so? Because many country musicians were children of the Great Depression who were born into poor rural families. If they wanted to hear music, they usually had to make it themselves, and if they did it well enough, they had a chance to lift themselves out of poverty. What's more, it's natural enough for siblings who make music together as children to keep on doing so in adulthood.

Brother acts have usually been more popular in country music than sister or husband-and-wife acts, and none has been more admired or influential than the Louvin Brothers, who cut their first record in 1947. Like many sibling acts, they were a match made in hell, so much so that Ira Louvin's violent, alcohol-fueled temper finally led his younger brother Charlie to break up the duo in 1963, two years before Ira died in a car crash. But you'd never have guessed it from hearing them sing together, for their high, hard-bitten voices wound round one another in harmonies so closely woven that you couldn't always tell which brother was singing what part.

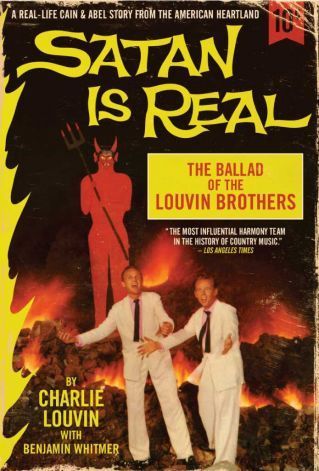

Two months before his own death in 2011, Charlie Louvin finished work on a memoir that was published earlier this year. "Satan Is Real: The Ballad of the Louvin Brothers" (Igniter/HarperCollins), which has the rough-hewn sound of a real person swapping stories after hours, is one of the most important and illuminating memoirs ever written by a country singer. Not only is it as readable as a first-rate novel, but "Satan Is Real," which is named after the Louvin Brothers' best-known album, a 1959 collection of gospel songs, offers urbanites a joltingly vivid glimpse of what it was like to grow up on a Depression-era farm....

* * *

Read the whole thing here .

The Louvin Brothers sing "I Can't Keep You in Love With Me" on Pet Milk Grand Ole Opry in 1961:

Terry Teachout's Blog

- Terry Teachout's profile

- 45 followers