Terry Teachout's Blog, page 104

February 1, 2013

PLAY

KNOWN BUT NOT LOVED

January 31, 2013

TT: Kill or be killed

* * *

Long before Neil Simon was America's hottest playwright, he was the youngest writer on the staff of NBC's "Your Show of Shows." Still fondly remembered by octogenarian connoisseurs of TV comedy, "Your Show of Shows," which aired from 1950 to 1954, was a weekly series starring Sid Caesar and Imogene Coca that featured some of the best comic sketches ever to grace the small screen. The movie "My Favorite Year" was inspired by "Your Show of Shows," and in 1993 Mr. Simon turned his own memories of working on the show into "Laughter on the 23rd Floor," a very thinly disguised roman à clef about the writers of a variety series called "The Max Prince Show."

Long before Neil Simon was America's hottest playwright, he was the youngest writer on the staff of NBC's "Your Show of Shows." Still fondly remembered by octogenarian connoisseurs of TV comedy, "Your Show of Shows," which aired from 1950 to 1954, was a weekly series starring Sid Caesar and Imogene Coca that featured some of the best comic sketches ever to grace the small screen. The movie "My Favorite Year" was inspired by "Your Show of Shows," and in 1993 Mr. Simon turned his own memories of working on the show into "Laughter on the 23rd Floor," a very thinly disguised roman à clef about the writers of a variety series called "The Max Prince Show."Mr. Simon's career was in terminal decline by then, and "Laughter on the 23rd Floor" ran for just nine months on Broadway. But TACT/The Actors Company Theatre's 2012 Off-Broadway revival of "Lost in Yonkers" was so noteworthy that I've been seeking out regional productions of Mr. Simon's other plays to see how they hold up. That's what brought me to Orlando's Mad Cow Theatre, which mounted an impressive "Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead" in 2010 and is now doing "Laughter on the 23rd Floor." While Mr. Simon is no Tom Stoppard, Mad Cow's "Laughter on the 23rd Floor" is pulverizingly funny. Not only does the play work, but this production, directed by David Russell, is a case study in how to stage punch-line humor. It doesn't just make you laugh--it rips the laughs out of you.

"Laughter on the 23rd Floor" doesn't have much of a plot: NBC wants Max Prince (Philip Nolen) to dumb down his program in order to satisfy the small-town rubes, and he responds by declaring war on the network. While that really did happen to "Your Show of Shows," it feels like a contrivance, an excuse for comedy. Fortunately, the real point of "Laughter on the 23rd Floor" is not Max's relationship with the network but his relationship with his writers, who have no illusions about their half-crazy boss. As one of them explains, "Max gets in his limo every night after work, takes two tranquilizers the size of hand grenades and washes it down with a ladle full of scotch." That's a recipe for trouble, and for lunatic slapstick.

The excellence of this revival lies in the kill-or-be-killed ferocity with which the actors tear into the script, taking their cue from this exchange between Val (Tim Williams), the head writer, and Kenny (David Almeida), the show's resident egghead: "A little aggression is good for writers. All humor is based on hostility, am I right, Kenny?" "Absolutely. That's why World War II was so funny. Schmuck." Everybody in the cast, especially Mr. Williams, throws their punches savagely hard, knowing that the Jewish humor in which Max's writers specialize is rooted in anger--and honesty....

* * *

Read the whole thing here .

Sid Caesar and Imogene Coca in "The Recital," a sketch from Your Show of Shows:

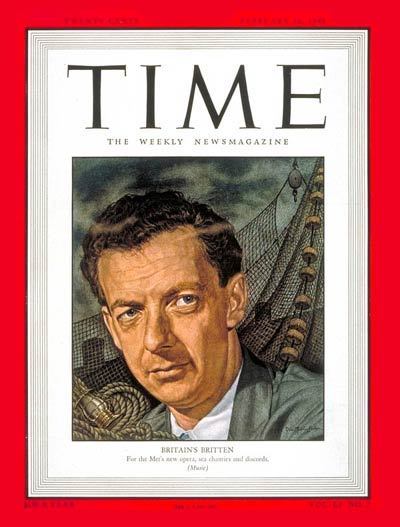

TT: Britten up, Britten down

* * *

No one can resist a centennial. Benjamin Britten, England's foremost classical composer, was born on Nov. 22, 1913, and the world of music has already started to mark the occasion. Go to www.britten100.org and you'll find a list of more than 1,500 world-wide Britten-related events. That's a lot of performances--but, then, Britten wrote a lot of music. He was the 20th century's most successful opera composer, and most of his operas, including such masterpieces as "Peter Grimes" (1945) and "The Turn of the Screw" (1954), continue to be staged regularly. He also wrote vast amounts of vocal and instrumental music, and in addition to being a composer, he was also a supremely gifted conductor and pianist who left behind dozens of remarkable recordings...

Yet critics as a group have been slow to admit Britten to the pantheon of top-tier composers. His unfailingly accessible, straightforwardly beautiful music, like that of Aaron Copland, his opposite number in America, is widely--if by no means universally--thought to be too "easy" to be great. But there's more to it than that. Throughout his life and to this day, Britten's reputation has risen and fallen for reasons that have at least as much to do with his complex personality.

Yet critics as a group have been slow to admit Britten to the pantheon of top-tier composers. His unfailingly accessible, straightforwardly beautiful music, like that of Aaron Copland, his opposite number in America, is widely--if by no means universally--thought to be too "easy" to be great. But there's more to it than that. Throughout his life and to this day, Britten's reputation has risen and fallen for reasons that have at least as much to do with his complex personality.For openers, he was a pacifist who refused to serve in World War II, instead registering in 1942 as a conscientious objector. Not surprisingly, Britten was angrily criticized by his contemporaries for refusing to fight the Nazis....

In addition, Britten was homosexual at a time when "gross indecency" between consenting adults was a criminal offense in England (it remained so until 1967). While his sexuality was never mentioned publicly, it was known throughout the world of music and fairly well known outside it. Britten never pretended to be heterosexual--he lived with a male partner, the tenor Peter Pears--and while homosexuality was no less common then than it is today, anti-gay attitudes were far more widespread in artistic circles....

By the time of Britten's death in 1976, the mere fact of his homosexuality was no longer controversial. But his own sexual attitudes have lately generated a different kind of controversy, for he never managed to come fully to terms with the fact that he was gay....

* * *

Read the whole thing here .

A complete studio performance of Peter Grimes, taped by the BBC in 1969. Peter Pears performs the title role and the composer conducts the London Symphony Orchestra:

TT: Almanac

Benjamin Disraeli, The Wondrous Tale of Alroy

January 30, 2013

TT: Almanac

Samuel Johnson (quoted in James Boswell, Life of Johnson)

TT: So you want to see a show?

Here's my list of recommended Broadway, off-Broadway, and out-of-town shows, updated weekly. In all cases, I gave these shows favorable reviews (if sometimes qualifiedly so) in The Wall Street Journal when they opened. For more information, click on the title.

BROADWAY:

• Annie (musical, G, reviewed here)

• The Mystery of Edwin Drood (musical, PG-13, closes Mar. 10, reviewed here)

• Once (musical, G/PG-13, nearly all performances sold out last week, reviewed here)

• The Other Place (drama, PG-13, closes Mar. 3, reviewed here)

• Picnic (drama, PG-13, closes Feb. 24, reviewed here)

• Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (drama, PG-13/R, closes Mar. 3, reviewed here)

OFF BROADWAY:

• Avenue Q (musical, R, adult subject matter and one show-stopping scene of puppet-on-puppet sex, reviewed here)

• The Fantasticks (musical, G, suitable for children capable of enjoying a love story, reviewed here)

CLOSING SATURDAY IN SARASOTA, FLA.:

• The Best of Enemies (drama, PG-13, reviewed here)

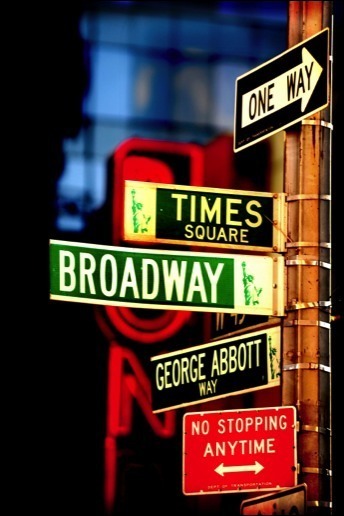

TT: The one good reason to take a chance on Broadway

* * *

I'm supposed to keep it short, and I approve of that. In case you've never heard it, this is the Drama Critic's Prayer: Dear God, if it can't be good, let it be short. So I'll be brief--and, I hope, to the point. I'm here to ask all of you a tough question: exactly why do you want to be on Broadway?

I'm supposed to keep it short, and I approve of that. In case you've never heard it, this is the Drama Critic's Prayer: Dear God, if it can't be good, let it be short. So I'll be brief--and, I hope, to the point. I'm here to ask all of you a tough question: exactly why do you want to be on Broadway?If you're out to make money, you've come to the wrong place. The odds aren't just against you, they're way against you. But does that ever stop anybody? Not as far as I can tell. Most people in the theater business long above all things to make it to Broadway, whether it's on or off stage. And I wouldn't dream of trying to talk anybody in this room out of that goal. What I want to do is ask you not to change your goal, but to look at it in a different way.

So let's start with what I call the One Terrible Fact About Broadway. Here it is:

Seventy-five percent of all Broadway shows lose money. Three shows out of four.

This being the case, I'm damned if I know why they call investors investors. What they're doing is gambling. And so are you, no matter what role you play in the process. Writers, actors, directors, designers, producers, publicists, stagehands...you're all gamblers, every last one of you, and you're betting against the house.

But let's take that One Terrible Fact and look at it from a different point of view. Why do people gamble? I don't mean addicts, but ordinary folks who like to visit a casino and shoot some craps or play the slots. Why do they do that, knowing that they're almost certainly going to lose money? Because it's fun. It's exciting. Stimulating. Not for everybody, of course, but if you're not the kind of person who finds gambling exciting and stimulating, you're probably not going to spend your next vacation in Las Vegas. And since we're taking it for granted that you're not an addict, then we can also take it for granted that you're O.K. with losing the money going in. Why? Because you know that you're using it to purchase pleasure.

Now let's suppose that you're not a casino gambler, but a Broadway gambler. You're not an addict, you're not a fool, you're a person who goes in with his eyes wide open. You know that you're shooting craps. You're betting against the house. You've only got one chance in four of succeeding, and you've been around long enough to know that there's nothing much you can do to change the odds. Sometimes good shows hit, and sometimes they don't. Sometimes bad shows hit, and sometimes they don't. What William Goldman said about Hollywood goes double on Broadway: nobody knows anything. And that means that there's only one reason for you to be on Broadway--and that's to have fun.

Now let's suppose that you're not a casino gambler, but a Broadway gambler. You're not an addict, you're not a fool, you're a person who goes in with his eyes wide open. You know that you're shooting craps. You're betting against the house. You've only got one chance in four of succeeding, and you've been around long enough to know that there's nothing much you can do to change the odds. Sometimes good shows hit, and sometimes they don't. Sometimes bad shows hit, and sometimes they don't. What William Goldman said about Hollywood goes double on Broadway: nobody knows anything. And that means that there's only one reason for you to be on Broadway--and that's to have fun.So how do you do that? If you're a creative person--and everybody on Broadway is, or should be, creative in one way or another--then the best way to have fun is to try to do something good. Really good. To roll the dice on excellence.

I know what you're thinking. So far as I know, nobody in the real world has ever set out to write a mediocre show. Even the author of Springtime for Hitler thought it was good. But just as there are different ways to flop, so are there different ways to be good. At bottom, though, I think there are really only two ways. You can try to shorten the odds a little bit by making a nice, safe show, or you can say, "The hell with it, I'm really going to roll the dice. I'm going to make the best and most original show that I've got in me. I want to work on the best and most original show I can find. Because it's probably going to lose money anyway--so why shouldn't I take a chance?" And that's the one good reason to take a chance on Broadway: to do something that's never been done. To know the exhilaration of embracing creative risk. To take a chance at being powerfully, excitingly, unforgettably fresh and original.

Here are four possibilities. Let's think about them for a minute.

• You can make a nice, safe show that misses the target and loses its investment. We won't name any names. You know who I'm talking about. And if I had to guess, I'd say that most Broadway shows belong in that box. Nothing ventured, nothing gained, no fun, no money. Why bother?

• You can make a safe show that hits. The 2011 revival of How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying fits in this box very neatly. It was about as risk-free as you can get. A musical that everybody loves, a star whom everybody knows. And it hit. It should have hit. I loved it. But...it was safe. Safe for the audience, safe for the makers, safe for all the people who worked on it. Nobody involved with that revival got to go home after opening night and say, "Look, I made a hat where there never was a hat."

• You can make a risky show that isn't a hit. Consider Lincoln Center Theater's revival of Clifford Odets' Golden Boy. It was brilliant. Every critic in town went nuts over Golden Boy, as well they should have. Because Lincoln Center went back to the well and revived a classic American play that nobody does, a show that hadn't been seen on Broadway since 1952...and they did it right. No creative compromises. No unsuitable movie stars. Nothing but a great script and a great production. And no, it didn't exactly make the box-office needle bounce--but everybody involved with that production is proud to say that they worked on Golden Boy, because everybody who bought a ticket to see it was stunned speechless by how great it was. I can tell you, it was the kind of show that makes people cry. Lots of people.

• You can make a risky show that isn't a hit. Consider Lincoln Center Theater's revival of Clifford Odets' Golden Boy. It was brilliant. Every critic in town went nuts over Golden Boy, as well they should have. Because Lincoln Center went back to the well and revived a classic American play that nobody does, a show that hadn't been seen on Broadway since 1952...and they did it right. No creative compromises. No unsuitable movie stars. Nothing but a great script and a great production. And no, it didn't exactly make the box-office needle bounce--but everybody involved with that production is proud to say that they worked on Golden Boy, because everybody who bought a ticket to see it was stunned speechless by how great it was. I can tell you, it was the kind of show that makes people cry. Lots of people. That's the right kind of gamble--to gamble on excellence--and not just because it makes you feel really good inside. Because every once in a while, excellence and originality hit the box-office bull's-eye.

And that brings us to:

• The risky show that hits. One word: Once. I don't know anybody who thought it made sense to bring Once to Broadway. I wouldn't have done it. A small, intimate, starless musical. No fancy sets. Nothing fancy at all. And the boy and girl don't even get together as the curtain slowly falls. And you know what? Once is minting money! A small, intimate, starless, cheap musical that sells out every show. Virtue has been rewarded.

Is that a case for taking offbeat musicals to Broadway? Absolutely not. It's the case for gambling on excellence. On originality. On accepting the One Terrible Fact of Broadway--good or bad, most shows fail--and letting it liberate you. If you can't count on getting rich, then forget playing it safe. Why not take a shot at being great?

Seeing as how I'm a Broadway critic, I'll end with a Broadway story. It's about Leland Hayward, one of the great producers of the Forties and Fifties. He was going to put on a play by Maxwell Anderson called Anne of the Thousand Days, and he asked Anderson who should play Henry VIII. So Anderson gave it some thought, and then he played it safe and suggested a good, solid actor with no flair, no panache.

Hayward got red in the face, banged on the desk, and said, "No, no, Max! Suppose there were absolutely no problems in getting anyone in the world you wanted. Who would you pick?"

Hayward got red in the face, banged on the desk, and said, "No, no, Max! Suppose there were absolutely no problems in getting anyone in the world you wanted. Who would you pick?"Anderson didn't hesitate for a moment. He said, "Rex Harrison--but you'll never get him."

And Hayward grinned and said, "Why not ask?" He picks up the phone, he starts placing calls, and an hour later, Rex Harrison had agreed to play Henry VIII in Anne of the Thousand Days.

Hayward hangs up. He grins. He says, "There's a lesson in this, Max. Never start out asking for someone you'd eventually settle for."

And that's the moral of the story. If there's ever a time in life for you to shoot high, this is it. Don't start out settling for safe--gamble on great. Forget about making money. You're not going to make money. Instead, make something beautiful. Something special. Something new. Something that makes you proud. Do that and you always win...and who knows? You might even get rich.

January 29, 2013

TT: John Gielgud's Jewish problem

One of them was written after he saw a 1965 Metropolitan Opera production of Aida that starred Richard Tucker, whom Gielgud referred to as "Radames in a tea-cosy gold helmet on top of a fat Jewish face. He is a cantor at one of the synagogues and looks like it. 35 dollars a ticket and a hideous audience for some Israelite Benefit."

One of them was written after he saw a 1965 Metropolitan Opera production of Aida that starred Richard Tucker, whom Gielgud referred to as "Radames in a tea-cosy gold helmet on top of a fat Jewish face. He is a cantor at one of the synagogues and looks like it. 35 dollars a ticket and a hideous audience for some Israelite Benefit."That's nasty enough, but what he wrote about War and Remembrance, a 1988 TV adaptation of Herman Wouk's historical novel about World War II in which Gielgud played a Jewish character who died in the gas chambers, is...well, I'll let you decide: "This endless appetite to go on plugging the Nazi horrors--wildly pro-Jewish American, of course."

It is, I think, revealing that none of the reviews of Sir John Gielgud: A Life in Letters, so far as I know, made mention of these passages, or others like them. Presumably the reviewers thought them unimportant. Gielgud, after all, never said anything invidious about Jews for public consumption. His anti-Semitism appears to have been a purely private matter, one of which we would know nothing had the editor of his letters chosen to omit it from the book.

Being a biographer who has grappled with closely similar problems, I can't say I wish that Richard Mangan had sanitized Sir John Gielgud: A Life in Letters. I believe deeply in telling the truth about great men, even when it isn't pretty. Here is the epigraph to my forthcoming biography of Duke Ellington: "There is one very good thing to be said of posterity, and this is that it turns a blind eye on the defects of greatness." Somerset Maugham said that, and I think he was right--up to a point.

On the other hand, I don't believe in pretending that such defects don't exist, or that they don't matter. John Gielgud's anti-Semitism casts no shadow on the quality of his art, but it most definitely casts a shadow on the quality of his soul, and I don't think it makes me a prig to care about such things.

It is, of course, futile to do so. Artists are strange creatures, flawed and weak and inconsistent, and only a fool takes them for anything else. As I wrote in this space nine years ago:

But, then, artists also incline to ruthlessness, don't they? As William Faulkner once observed, "If a writer has to rob his mother, he will not hesitate: The 'Ode on a Grecian Urn' is worth any number of old ladies." This is not, thank God, a universal rule. Most of my friends are artists, and most of them seem disinclined to rob their mothers. But most of the great artists I've known--and it's a short list--have done things in the service of their art at one time or another (though never to me) that were so selfish as to make my hair stand up.

Plenty of great artists have said and done things that make us shudder today, and wise critics endeavor to separate their bad behavior from the beautiful objects of art that they created. To do otherwise is to run the risk of falling victim to retrospective self-righteousness. I'll always love John Gielgud's artistry, and I doubt I'll be thinking of the fact that he didn't like Jews the next time I watch Ages of Man or Arthur . But I have no intention of forgetting it, any more than I would ever allow myself to forget that George Bernard Shaw was a Stalinist or Alfred Cortot a Nazi collaborator.

The ability to make great art excuses no man his basic human responsibilities. That is a debt he owes to us all.

* * *

A 1930 recording of John Gielgud performing Gratiano's speech from the first act of The Merchant of Venice:

TT: Snapshot

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday and Wednesday.)

Terry Teachout's Blog

- Terry Teachout's profile

- 45 followers