Nerissa Nields's Blog, page 6

October 2, 2013

Martha, Mary and Michaelmas (And Cheryl Wheeler and Louis C.K.)

Sept. 29, 2013

Sept. 29, 2013Scripture: Luke 10:38-423

8 As Jesus and his disciples were on their way, he came to a village where a woman named Martha opened her home to him. 39 She had a sister called Mary, who sat at the Lord’s feet listening to what he said. 40 But Martha was distracted by all the preparations that had to be made. She came to him and asked, “Lord, don’t you care that my sister has left me to do the work by myself? Tell her to help me!”

41 “Martha, Martha,” the Lord answered, “you are worried and upset about many things,42 but few things are needed—or indeed only one.[a] Mary has chosen what is better, and it will not be taken away from her.”

…and second scripture:

In every instant, two gates.

One opens to fragrant paradise, one to hell.

Mostly we go through neither.

Mostly we nod to our neighbor,

lean down to pick up the paper,

go back into the house.

But the faint cries—ecstasy? horror?

Or did you think it the sound

of distant bees,

making only the thick honey of this good life?

-Jane Hirshfield

Today is Michaelmas, a lesser Catholic feast that somehow always gets my attention. It makes me think of midlife. Maybe it makes everyone think of midlife. It comes, after all, just a few days after the autumn equinox, and autumn is certainly the season of midlife, what with the balding maples, the falling leaves, the drama before the long quiet.

This year Michaelmas falls also on a waning moon. It seems all of nature is conspiring to force us to think about the brevity of life. The two readings—the Martha/Mary story which Steve has preached about often, and the Jane Hirshfield poem—both touch on this idea of the choices we make, and it seems to me that midlife can be an especially painful time to sit with our choices. (Though I suspect every phase of life has this potential pain…)

When we were kids, we were Marys. My kids are Mary-like. They pay attention to the important stuff. They know that it’s good for them to play, to move their bodies, to climb on things. They know a good story when they hear one, and they also know justice. They have an acute sense of what is fair.

As we age, we become more Martha-like. We don’t pause from our dinner preparations to run outside during one of those summertime micro rain storms, to dance in the rain after a long dry dusty hot spell. We do the never ending laundry—Mount Washmore, my friend calls it. We go to the grocery store. We pick up the kids. We exercise—but on a schedule. And we justify our good, hard disciplined work: in any revolution there is work to be done, and Jesus surely was a revolutionary.

And don’t the ones who do the work get the praise? So why is Jesus saying that Mary’s the one who gets it?

Part of the gift of midlife is that we do get it. We see how painfully brief it all is. Now I know Mary’s got the right idea. And I still can’t stop doing doing doing. Still can’t stop frantically doing the dishes, doing the laundry, telling my kids to hurry up so we won’t be late to school. I do my meditation and my yoga—but I time myself with my iPhone and don’t let myself linger. I tell myself I will go on a meditation retreat when the kids are older.

But I have the usual questions. Is Jesus saying we should always listen to God? Or just when he comes over for dinner? Does Jesus really want us to forgo making the beds in the morning and instead practice piano? Wasn’t Jesus glad that Martha was making preparations? I know I’m not alone in having some feminist annoyance with this passage. Would it have been better if Martha had sat down too? But then there’d be no food for anyone. Maybe they would have just eaten locusts, then. Is Jesus saying “Sorry, babe. You’re just a Martha. Marthas cook and clean. Marys sit and listen. Try again next life, and you might luck out.”

Well, of course not. Jesus’s whole point was to free us from the binary thinking of the old world, teach us non-dualism. No I, no Thou. Jesus said, “I and the Father are one. And so it is with you.” Jesus said, “I am the vine, you are the branches.” Last time I looked, it was hard to tell the difference between vine and branches. We’re always Martha and Mary, just as God is in each of us, beyond all of us, and in the interactions between everything.

Moreover, when I grumbled a version of this to my friend Peter Ives, he pointed out that at the time of Jesus, women were barely considered human. For Jesus to say that Mary should sit and listen to him, and in fact Martha should put down her dishrag and join in too, was completely revolutionary. He was calling them, these two sisters, to be disciples, equals to his male followers. It’s not really news in Bible scholarship that Jesus elevated the role of women to that of equal, though the Nicene Creed and fifteen hundred years of organized religion put the kibosh on much of that. But when I heard this, I had to look at my own internalized sexism. It hadn’t occurred to me on first read-through that in fact Jesus might indeed have been saying, “Dudes, your turn. Go make the dinner while Martha and Mary get their time with me. And if you don’t know how to make the dinner, go find some locusts.” For all we know, that was in the original text, only to be nixed three hundred years later during the Council of Nicea. Three hundred years later, women were back in their historical place.

This came through my email-box this morning from Richard Rohr, a Franciscan friar:

Did you know the first half of life has to fail you? In fact, if you do not recognize an eventual and necessary dissatisfaction (in the form of sadness, restlessness, or even loss of faith), you will not move on to maturity. You see, faith really is about moving outside your comfort zone, trusting God’s lead, instead of just forever shoring up home base. Too often, early religious conditioning largely substitutes for any real faith.

Usually, without growth being forced on us, few of us go willingly on the spiritual journey. Why would we? The rug has to be pulled out from beneath our game, so we redefine what balance really is. More than anything else, this falling/rising cycle is what moves us into the second half of our own lives. There is a necessary suffering to human life, and if we avoid its cycles we remain immature forever. It can take the form of failed relationships, facing our own shadow self, conflicts and contradictions, disappointments, moral lapses, or depression in any number of forms.

All of these have the potential to either edge us forward in life or to dig in our heels even deeper, producing narcissistic and adolescent responses that everybody can see except ourselves.

And the other wise sage I came across was the comedian Louis CK who went on a rant about iPhones on the Conan O’Brien show. He basically says the same thing as Father Richard:

…you need to build an ability to just be yourself and not be doing something. That's what the phones are taking away, is the ability to just sit there. That's being a person. Because underneath everything in your life there is that thing, that empty—forever empty. That knowledge that it's all for nothing and that you're alone. It's down there.

And sometimes when things clear away, you're not watching anything, you're in your car, and you start going, 'oh no, here it comes. That I'm alone.' It's starts to visit on you. Just this sadness. Life is tremendously sad, just by being in it...

To be an artist, or a revolutionary, or just a good person trying to feel our way through life with a modicum of consciousness, we need to rest, Mary-style, fill the well. We need to do nothing. We need to look up at the sky, notice what kind of moon it is, breath in the smell of falling leaves and pond scum and compost and fall-bearing raspberries. To love someone, to really love someone, we need to give them years of our attention. Years. Focus and appreciation every single day. That’s the sunlight they need to grow.

Last week, I happened to notice, as I occasionally do, all the people around me who were doing it better than me. By “it” I mean everything from having a music career to gaining spiritual insights. I couldn’t help but notice all my spiritual friends who all seem to be gaining enlightenment at a frightening clip. My friend Julie went on a 10 day silent retreat, and now she has no more anger. My friend Charlotte did this three year long inventory of her greater defects and now she hears God’ voice loud and clear and never has any questions about what she should do. All this makes me want to give up, give in, throw in the towel, text and drive, abandon my highly scheduled meditation practice. Instead I called my mom and asked her what she thought of Sheryl Sandberg, the latest voice in the Mommy wars. Sandberg wrote a book called Lean In, which points out the sexism still rampant in our culture, and how hard it is for career women to be mothers and gives excellent advice to women who want to fight to keep their careers thriving. Sandberg exhorts women to lean in rather than lean back when they even begin to think about having a child. Recently, I’ve heard my peers rumbling with discontent about this message. “The problem is,” said one of my closest friends, a highly successful author, “I really do want to lean back right now. I want to volunteer at my daughter’s school. I want to make her Halloween costume. Is that so wrong?”

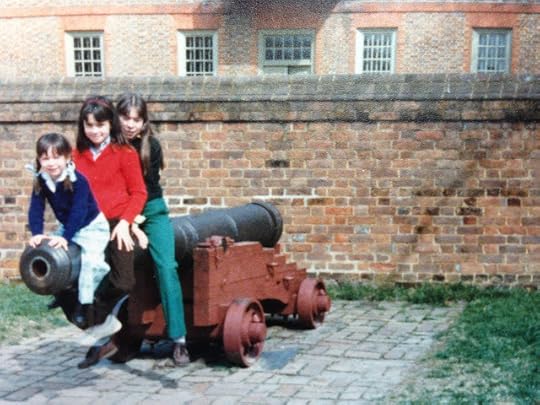

“Well there’s just so much to hate about Sheryl Sandberg,” my mother began. “She has nannies raising her children! What are all these people thinking, making $300,000 a year! I am so glad I invested my time in you girls.”

I’m pretty sure my mother hasn’t read the book. She, like me, had a career and also had kids, and tried to balance them as well as she could, which seemed to involve a lot of yelling and tossing of backpacks into the car with a hot cup of coffee sloshing about. It’s true that when push came to shove, she would choose her children every time. But still, my mother worked hard. She sure as hell leaned in. She was always grading papers at the kitchen table, cooking our dinner, making our lunches, or playing extremely competitive tennis during those hours after school and before dinner. She did not get on the floor and play games with us, or engage in imaginative play. But she did sit on my bed at the day’s end and ask me to talk about things. She knew what the better part was. Mostly. Like all of us, she was sometimes Martha, sometimes Mary.

So if Jesus is calling us to be disciples, if Jesus is calling women to be disciples with the same urgency that he calls men, this brings us right back to the question women have been wrestling with since the dawn of the women’s movement. I, for one, certainly can make the dualism about choosing family over career, for instance. Last week, Katryna and I opened for a great singer songwriter Cheryl Wheeler. Cheryl is one of a kind. She looks like what she is: a 62 year old who dresses in LL Bean (onstage and off), loves her dogs and Cathleen, her wife of 10 years, and doesn’t give a whit about what the music business—or anyone else for that matter—thinks of her. She is hilarious, occasionally raunchy, onstage, so funny that my sides often hurt from laughing so hard when I am at one of her shows. She has a song on her latest CD called “Shutchier Piehole”, making the point that it would be really hard if your last name were “Piehole” and your parents named you “Shutchier.” Hard, yes, but funny. A few songs later, she delivered her 1980’s love ballad “Arrow,” a song so achingly beautiful we were all in tears by the end. Her following is as strong today as it ever was. Her fans are loyal; we opened for her in 1992 at the Iron Horse, and a couple from last Friday’s concert came up to us and said, “I remember seeing you at that show, 21 years ago…”

Cheryl has what I always wanted. A career that keeps growing. She sang songs she’d just written, along side songs that were over thirty years old. But what’s most enviable about her show is that she is just…Cheryl. She is totally herself. There is no artifice. She is completely unconcerned about whether or not we like her. She performs sitting down and refuses to leave the stage for the encore. She asked the lighting engineer to turn down the lights because “No one paid to see the visuals. If they did they would be sorely disappointed. They came to listen.”

Though I can try to make this about right and wrong, Martha and Mary, kids versus career, what I really want is that comfort with myself. I want to not care whether or not you notice that my face isn’t airbrushed. I want not to care if you notice that I’ve gained or lost a few pounds. But more than that, I want to not care what you think about how hard I’m working, how much I’m doing, how the fact that I spent the last seven years trying to raise human beings has resulted in flaws, in big gaping holes in my artistic work, not to mention the more painful flaws in my parenting. I want to stop trying to prove my worth by scrubbing the dishes for the revolutionaries. I want instead to sit around, the way Cheryl did, and chew the fat with her old buddies who’d paid $25 a head just to see her. And I want the humility to keep learning, keep growing. I want to laugh. And this is both the gift of an awake, aware midlife passage, and the gift of discipleship.

As Hirshfield seems to be saying, every instant has two gates, but it’s true that we mostly go through neither. We’re just not that awake most of the time. Martha didn’t choose incorrectly just because Mary happened to see the instant and go through the gate of paradise. Martha just missed seeing the gate. We all do, all the time. We get worried and upset—that’s a guarantee if we are human. It’s more than guaranteed if we’re parents. In fact, every single day I vow, on my knees, that I will do better, that I will be patient with my kids, that I will not be short with them, that I will react to frustration with humor (in fact I have “react to frustration with humor” as a reminder on my iPhone, and it pops up regularly, along with “don’t read your iPhone right now—pay attention to the kids instead.” And still, every day, I lose it. I lose it even as I am praying not to. Even as I am thinking, “don’t shame her, let her be herself,” I say, “You’re wearing THAT to school?”

But then, there is grace, too. Somehow, I can sometimes see the gates and choose the better one. Yesterday, a perfect September afternoon with a cloudless sky, I abandoned my agenda and let the kids stay late at school to play on the playground. Johnny found a pick up game of soccer. I stood and watched him race across the field, galloping after the ball, kicking, falling, getting up again, chasing the bigger kids, leaping from one foot to the other. I breathed in the sweet smell of cut grass, the late blooming sedum, and said Yes. This is the better part. Or maybe it’s just the thick honey of this good life.

Published on October 02, 2013 09:51

How to Be an Adult Introduction, Part Three: Missing Owner's Manual

There Is Always Someone Who Can Help, So Ask

There Is Always Someone Who Can Help, So AskBeware: this is a spiritual lesson as well as a practical one. There is always someone out there who can help you. If he or she doesn’t respond to your call for help right away, keep calling. Eventually someone will, and in the meantime, you will have made lots of connections. Ask questions. How to Be an Adult Golden Rule: If you want to do something well, find someone who is doing it beautifully (or at least adequately) and ask her how she does it. People love to give advice. They love to feel like they know something you don’t know. You aren’t bothering them. Figure out the channels. And thank God for Google. When we were your age, there was no internet! (At least, not that I nor any of my friends knew about, though of course, Al Gore and people at NASA did.) Today, finding out information is as easy as typing, “How do I change my oil?” into the search box.

And thank God (or whatever you think runs this ship) that we live in a world where we’re supposed to intermingle and get to know each other. Ignorance and abject terror are wonderful prods toward this end.

And thank God (or whatever you think runs this ship) that we live in a world where we’re supposed to intermingle and get to know each other. Ignorance and abject terror are wonderful prods toward this end. Speaking of God, I should let you know that I believe in God. I don’t mind at all if you don’t, but you should know this about me, because it informs all of the advice in this series. The older I get, the less confidence I have in the aging, creaky body that used to be able to leap from the top bunk halfway across the room unharmed, and more confidence in 1. the wisdom of those who have gone before me, 2. the wisdom of the ages, 3. what actually works, and 4. what I know resonates in my bones as true. All this fits into my definition of God. So if God talk bugs you, feel free to translate the “G” word to “the Universe” or “Truth” or “The Great Reality” or “Presence” or “Big Cheese” or “Yo Mama” for all I care. Or else—and I give you my permission—just roll your eyes when I bring up God.

Speaking of God, I should let you know that I believe in God. I don’t mind at all if you don’t, but you should know this about me, because it informs all of the advice in this series. The older I get, the less confidence I have in the aging, creaky body that used to be able to leap from the top bunk halfway across the room unharmed, and more confidence in 1. the wisdom of those who have gone before me, 2. the wisdom of the ages, 3. what actually works, and 4. what I know resonates in my bones as true. All this fits into my definition of God. So if God talk bugs you, feel free to translate the “G” word to “the Universe” or “Truth” or “The Great Reality” or “Presence” or “Big Cheese” or “Yo Mama” for all I care. Or else—and I give you my permission—just roll your eyes when I bring up God. Missing Owner’s Manual

Missing Owner’s ManualBut regardless of your spiritual beliefs, you don’t need to suffer the way we did! Because Katryna and I have put everything you need to know into one handy volume, with each book highlighting a different delightful area of adultification. Within these pages, we address: time management (er…consciousness), goal-setting and goal-resistance, mental and physical health, jobs and work life, home, food, money, cars, insurance, getting along with others, voting, marriage, divorce, remarriage, and parenthood.

Even though I probably would have ignored it, I wish I’d had a manual like this back when I was 21. When I went to the bookstore looking for how-to books, they inevitably intimidated me with their length and writing style. Things with numbers threw me for a loop. Some people really do have a knack for navigating their way through the world and finding out how it works as they go—like my friends Jenny, Susan and Giselle. But others of us would much rather spend our time reading The New Yorker or Ann Patchett novels and have someone else figure out the quarterly taxes.

So for those of us who are artists or marchers to the beat of a different drummer, I attempted to create a series that speaks in the language we can understand: the language of poetry, humor, literature—a set of right-brained manuals. There is some concrete practical advice about money and insurance and stuff like that (think of this part of the book as the raisins in the cookie). The cookie part of the book is a series of how-tos in essay form, told through anecdote, in a way that is (I hope) palatable and memorable. A portable older sister, if you will. And like an older sister, it is full of partisan opinions. Other so-called adults will surely take issue with me on many of my claims, especially when I bash consumerism or blow the horn for the environment. I am sure I will annoy you at times; feel free to ignore me when I do. Also like an older sister, I will probably change my mind and do things differently a few years from now; after all, adulthood is not a static state any more than adolescence is. I’ve given you a lot of my own stories and life experiences because it’s the life I know best. When I had scant experience, I asked all my smart friends on your behalf. Thus, it’s the absolute best advice I can give you today. It’s the book I wish I’d been given at my graduation, or better yet, it’s the instructions my Latin diploma should have included, scrawled on the back like the Dead Sea scrolls.

Published on October 02, 2013 09:34

September 22, 2013

How to Be an Adult Introduction, Part Two: What We Learned About Life in 20 Years on the Road

What We Learned About Life in 20 Years on the Road

What We Learned About Life in 20 Years on the RoadKatryna first got the idea to write a book called How to Be an Adult after graduating college. She felt clueless, living with her sister and brother-in-law in a prep-school dorm and eating the prep-school’s free food, while trying to figure out things like how to get health insurance and how to pay her taxes on the non-existent income of a budding folk singer. She pronounced, “Someone should write a book called How to Be an Adult. How are we supposed to know any of this stuff? We all need a manual. Someone should write it, and since no one else will, I guess it’s got to be me. Except I don’t know how to be an adult, so why don’t you do it?”

We had grand plans to research the topic, but we never followed through. Over the years, we’d revive the project and toss around some ideas, but mostly the concept of either of us writing a book about how to be an adult reduced us to fits of tearful laughter. Who would take a couple of folk singers as their models for responsible adulthood?

But by my mid-thirties, I had observed two things. First of all, somehow along the way, like everyone else, I’d figured it out, mostly, and so had Katryna. It took years, and we made lots of painful and hilarious mistakes. But many of those mistakes were wonderful lessons.

Secondly, what I hadn’t figured out (taxes, insurance, retirement accounts, bill-paying) were easily deciphered by the simple act of homing in on someone who clearly appeared to be a competent adult and asking that person how she did what she did. Believe me, if you ask enough people, someone will have a strong opinion on this topic and feel it’s their mission in life to sit you down and set you straight.

Published on September 22, 2013 06:57

September 17, 2013

How to Be an Adult Introduction, part one

Introduction

On the occasion of my college graduation, I received my diploma and immediately began to examine it. It was written, unhelpfully, in Latin, a language I studied for one year at age thirteen. Undaunted, I flipped it over in the hopes that somewhere among the ovems and the isimuses there would be some final directive, some code that would tell me what to do next. I’d been an English major in college, taking the advice of my favorite high-school teacher who told me the purpose of college was to read all the books you’d never get around to reading otherwise. So while my roommates were studying pre-med, pre-law and economics, I was immersed in Shakespeare, Elizabeth Bishop, and Samuel Beckett. In March, Jenny was accepted to medical school, Susan was off to Stanford Law, and Giselle had a job offer on Wall Street. When anyone asked me what I was going to do, I said something vague about bringing my acoustic guitar to England, where I was planning to become a famous folk singer.

As the snow melted and the hackysackers returned to the green in the spring of my senior year, I noticed a consistent shortness of breath accompanied by a low buzzing in the back of my head. The approximate content of the low buzz was something along the lines of, “What the hell am I supposed to do now?” How, for example, was I supposed to find an apartment? What exactly was a down payment? Or a security deposit? For how long could I live solely off peanut butter and jelly sandwiches and ramen noodles? What was the difference between a premium and a deductible? Were they really serious about that whole filing taxes thing? That just seemed mean.

Hence the frantic fumbling with the diploma. There were no instructions on the diploma, just the smudged signature of the college president and some unintelligible Latin. So I did what any sensible, practical-minded person would do; I married my current boyfriend, David, who happened to be seven years older than I and, in my mind, a bona fide adult.

This worked out well for a while. David was happy to deal with what I termed the “grown-up stuff”: security deposits, medical insurance, bill-paying, and yes, taxes. My twenties rolled by pleasantly enough: I started a rock band along with David and my younger sister Katryna, and we drove around the country in a fifteen-passenger van.

Although in the early days of the band, I’d had to do a lot of what seemed like pretty “adult” stuff—booking gigs, putting together press kits, opening and maintaining a checking account—eventually, we hired a manager to do all that for us. Once again, I was off the hook. “Your job,” said our new manager Dennis, “is to write songs, stay in good shape, and rest up for your performances. Let me take care of everything else. After all, that’s why you pay me 16.67% of your gross income.”

So I spent my days in a kind of prolonged adolescent summer vacation: writing, reading, shopping for clothes that would make me look like a hot rock star (and running up credit card debt), exercising like a maniac so I would fit into said clothes, and driving around the country performing at festivals, coffeehouses, theaters and rock clubs. It was a blissful existence.

But nothing lasts forever, and by September 2001 the band had broken up, David and I had separated, and I was thirty-four years old—clearly an adult no matter how you did the math. I needed to learn how to function on my own and fast.

To read more, or to order the book, go here. Or...just wait until tomorrow when I post the next part.

On the occasion of my college graduation, I received my diploma and immediately began to examine it. It was written, unhelpfully, in Latin, a language I studied for one year at age thirteen. Undaunted, I flipped it over in the hopes that somewhere among the ovems and the isimuses there would be some final directive, some code that would tell me what to do next. I’d been an English major in college, taking the advice of my favorite high-school teacher who told me the purpose of college was to read all the books you’d never get around to reading otherwise. So while my roommates were studying pre-med, pre-law and economics, I was immersed in Shakespeare, Elizabeth Bishop, and Samuel Beckett. In March, Jenny was accepted to medical school, Susan was off to Stanford Law, and Giselle had a job offer on Wall Street. When anyone asked me what I was going to do, I said something vague about bringing my acoustic guitar to England, where I was planning to become a famous folk singer.

As the snow melted and the hackysackers returned to the green in the spring of my senior year, I noticed a consistent shortness of breath accompanied by a low buzzing in the back of my head. The approximate content of the low buzz was something along the lines of, “What the hell am I supposed to do now?” How, for example, was I supposed to find an apartment? What exactly was a down payment? Or a security deposit? For how long could I live solely off peanut butter and jelly sandwiches and ramen noodles? What was the difference between a premium and a deductible? Were they really serious about that whole filing taxes thing? That just seemed mean.

Hence the frantic fumbling with the diploma. There were no instructions on the diploma, just the smudged signature of the college president and some unintelligible Latin. So I did what any sensible, practical-minded person would do; I married my current boyfriend, David, who happened to be seven years older than I and, in my mind, a bona fide adult.

This worked out well for a while. David was happy to deal with what I termed the “grown-up stuff”: security deposits, medical insurance, bill-paying, and yes, taxes. My twenties rolled by pleasantly enough: I started a rock band along with David and my younger sister Katryna, and we drove around the country in a fifteen-passenger van.

Although in the early days of the band, I’d had to do a lot of what seemed like pretty “adult” stuff—booking gigs, putting together press kits, opening and maintaining a checking account—eventually, we hired a manager to do all that for us. Once again, I was off the hook. “Your job,” said our new manager Dennis, “is to write songs, stay in good shape, and rest up for your performances. Let me take care of everything else. After all, that’s why you pay me 16.67% of your gross income.”

So I spent my days in a kind of prolonged adolescent summer vacation: writing, reading, shopping for clothes that would make me look like a hot rock star (and running up credit card debt), exercising like a maniac so I would fit into said clothes, and driving around the country performing at festivals, coffeehouses, theaters and rock clubs. It was a blissful existence.

But nothing lasts forever, and by September 2001 the band had broken up, David and I had separated, and I was thirty-four years old—clearly an adult no matter how you did the math. I needed to learn how to function on my own and fast.

To read more, or to order the book, go here. Or...just wait until tomorrow when I post the next part.

Published on September 17, 2013 18:18

September 8, 2013

How to Be an Adult is Here! Preface Excerpt

I can't believe how long it's taken me to do what seemed a small task: to turn my 2008 paperback book How to Be an Adult into an ebook. Answer: almost 2 years. Really five years, since I had the thought as soon as I published the paperback. How hard could it be?

I can't believe how long it's taken me to do what seemed a small task: to turn my 2008 paperback book How to Be an Adult into an ebook. Answer: almost 2 years. Really five years, since I had the thought as soon as I published the paperback. How hard could it be? The problem was, once I reviewed the book, sometime last summer, I saw all the places I wanted to add, expand, and in a couple of cases, subtract. So I set about rewriting. And rewriting. And then factor in 2 kids, 5 careers, husband, beautiful summer weather, computer fatigue, etc and here you have it. September 6, 2013. A good a date as any to get started.

Once a week, I am going to publish an excerpt from the book. So here is the new Preface.

Preface to the 2013 Edition

In the five years since this book has come out, I have wanted, almost daily, to revise How to Be an Adult. This is natural, of course, as Adulthood is not a static state: one never arrives. New insights, new ways of changing car tires, organizing one’s finances, even new ways of roasting a chicken emerge, and I as an extroverted blabbermouth feel compelled to trumpet the new findings to the masses. Moreover, as the mother of two children (ages 7 and almost 5 as of this writing), I’ve had some good practice with some adultish skills that helped me to refine my perspective since the first edition, which was mostly written before motherhood, though edited and published when Lila was just two and Johnny was three months from being born. Those two kids have taught me more than all my life experiences to date combined. Also, as I am fond of saying, I was this close to enlightenment before I had kids. All that forgiveness work and cultivation of a relaxed attitude about the things that really matter, which I spout on about in the earlier edition—well, let’s just say I have been put to the test. And failed miserably. But as I have also written, it’s in the failing that we learn most.

When I asked for suggestions for the new edition, here were the requests:

• An expanded Vocation/Avocation section, especially with the advent of Facebook and Twitter and LinkedIn.

• Advice on resumés and interviewing

• More on time management (er, consciousness)

• A section on common illnesses and what to do about them

• A discussion of the importance of getting enough sleep

• A handy domestic toolbox full of tips

• Eggs and egg recipes

• More healthy recipes

• Skin care suggestions

I wrote this book because I love to give advice. I love to get advice too, and it’s extremely gratifying for me to find out the answers to the nagging questions—my own, and those of my friends. To this end, I regularly annoy my family by grabbing my iPhone as soon as anyone says, “I wonder how…” or “I wonder when…” or “I wonder what…” and then Googling like a madwoman. In my work as a life coach, I work with many twenty-somethings. I love it when they ask me basic questions to which I know the answers. But I love it even more when we work together to figure out some of the deeper problems we all confront—like how to break an addiction, or how to figure out what career would bring the most joy, or whether or not to marry the guy (or girl). I wanted to condense some of my coaching experience, too, in this new edition.

It can be lonely to be in one’s twenties. Not always, and not for everyone—sometimes the twenties are a rowdy extension of those bright college years. Some twenty-somethings are already married. But even then, even so, many folks I have spoken with confess to a sinking feeling of being alone with their cluelessness. Everyone else seems to know what to do. Why don’t I?

In her book The Gifts of Imperfection, Brené Brown talks about the important distinction between “fitting in” and “belonging.” We think these terms are synonyms, but actually they are worlds apart. “Fitting in,” to my mind, has always been about trimming off objectionable parts of myself so that I take up less space and don’t stand out in any way. I think that if I can do this, more people will love me. “Belonging” is the feeling I get when I’m among people who see my whole self––all the parts of me––and love me anyway. In fact, in many cases, it’s exactly those objectionable parts that create bonds between people. For me, my twenties were a journey that began as a “fitter-inner” and ended with a profound sense of belonging, and the way I got to this brave new place was through embracing my own objectionable parts. In doing so, I found my people, my Tribe, and through their collective wisdom, I got my answers, at least most of the time. When they failed me, when I had to strike out on my own, I came back with answers for them.

In this age of easy access to all kinds of information, we are training ourselves to Google things like, “Will my daughter have friends in Junior High School?” and “Is my neighbor stockpiling weapons of mass destruction?” as if Google were an oracle. The answers to many questions, in ancient Greece and modern-day America, are equally unknowable, but my sense is that when we’re compelled to reach out to the faceless unknown for answers, what we really want is to connect with the Tribe.

This book is in large part about identifying and finding that Tribe. In the beginning, you might start by looking among others who are equally clueless, and begin to commiserate with them. And then, ask questions. To that end, please join the conversation this book has launched at www.howtobeanadult.org where I will be posting regularly. Here, you can actually ask questions and get answers. We need your input!

In the meantime, I hope you enjoy this book. I hope I have kept the very best aspects of the original and added and improved where it was lacking. If you have suggestions on other topics, send them my way. And of course, if you have better ideas on how to manage time, organize a budget, roast a chicken or change a tire, let me know.

Published on September 08, 2013 07:30

September 6, 2013

Everyday Minefields

Last week I found out that a high level administrator from the school where my sisters and I were students from 1974 to 1990, pled guilty to multiple counts of “indecent liberties,” including “abduction with intent to defile,” fancy legalese for “he was a perv.” In fact, that’s exactly what we girls referred to him as—a perv. And being 12-13, I just assumed that schools had male administrators who occasionally copped a feel, who chaperoned every single student event including dances; who regularly stuck his head into the girls’ locker room to tell us to “keep it down” while we were changing into our field hockey uniforms. This man was a fixture at the school by the time I arrived in second grade. At a school with a strict uniform, he wore his own version: a Brooks Brothers button down with preppy chinos or cords, always in some outrageous combination of colors: one leg red, one green, one yellow, one blue. At our occasional and thrilling dances, he’d be standing near the sound system, flirting with the pretty ninth grade girls, sometimes dancing with them, occasionally slow dancing with them. He was a little scary as a disciplinarian. He was larger than life. Some kids adored him. He was a loving father and husband, from all accounts. Like all of us, he was and is good and bad. What he did cannot be undone. The hurt he caused lives on. And still, I feel very sad for him and for his wife and children. I'm not writing this to pass judgment. I'm writing this because I am curious about my own strange blindness to a crime that was going on all around me.

Last week I found out that a high level administrator from the school where my sisters and I were students from 1974 to 1990, pled guilty to multiple counts of “indecent liberties,” including “abduction with intent to defile,” fancy legalese for “he was a perv.” In fact, that’s exactly what we girls referred to him as—a perv. And being 12-13, I just assumed that schools had male administrators who occasionally copped a feel, who chaperoned every single student event including dances; who regularly stuck his head into the girls’ locker room to tell us to “keep it down” while we were changing into our field hockey uniforms. This man was a fixture at the school by the time I arrived in second grade. At a school with a strict uniform, he wore his own version: a Brooks Brothers button down with preppy chinos or cords, always in some outrageous combination of colors: one leg red, one green, one yellow, one blue. At our occasional and thrilling dances, he’d be standing near the sound system, flirting with the pretty ninth grade girls, sometimes dancing with them, occasionally slow dancing with them. He was a little scary as a disciplinarian. He was larger than life. Some kids adored him. He was a loving father and husband, from all accounts. Like all of us, he was and is good and bad. What he did cannot be undone. The hurt he caused lives on. And still, I feel very sad for him and for his wife and children. I'm not writing this to pass judgment. I'm writing this because I am curious about my own strange blindness to a crime that was going on all around me.What surprised me was how thoroughly I’d know this and how I hadn’t bothered ever to tell anyone in authority. Why? Because his perviness was wallpaper in my life. I didn’t know any different. And what’s bothering me is, of course, what else do I know and yet not know? What else is wallpaper?

At that same school, in the 6th grade, I had a woman teacher whose husband worked for the entertainment industry. It was 1979, and he'd give his teacher wife posters of the current blockbuster movies: Jaws, Star Wars, Grease, which she'd hang up on the perimeter of the upper walls of the classroom. He also gave her posters of the day's pin up girls: Farrah Fawcett in her famous wet bathing suit, Cheryl Tiegs in a yellow bikini, Bo Derek who was lauded at the time a perfect "10." As a reward to the rambunctious eleven-year-old boys, she'd hand out these posters at the end of the day for good behavior.

There's so much wrong with this picture, I don't know where to begin. "What did she give the girls?" a friend recently asked when I relayed this story. "Nothing," I said. "We always behaved." So boys behave badly, and then they get a treat for containing themselves? Girls, whose bodies are just starting to change, are presented with models (literally) of women whose bodies have been deemed "10"s, while the boys drool over them, equally longing for something they can't really have. But what I really see when I squint back at this memory is loneliness. There was a whole culture at this school that encouraged competition and judgment (discernment). We were all trying like mad to fit in, to feel OK, to understand our changing bodies, to find a kindred spirit. The grown ups, as far as I can remember, seemed remote, or else they seemed to mock us in our confusion. How dare we be so nubile and confused? Like many in my generation, I took this in. Now, as an adult, I want to take it on. I want to take over. I want to take it back.

I started a conversation on Facebook about the Upper school administrator. I included everyone I could think of, though only the girls. At first, only the people I had been close to at the time joined in. But a few days later, one girl who’d been touched spoke up. Then another, and then another. Now there’s a healthy dialogue, with all sorts of memories pinging about. We’re talking about how and if to bring up with our own children the potential dangers that might lurk in their schools. We’re talking about the sexism rampant in our culture in the late 70s and early 80s, and all that remains today despite great gains by women and girls. It’s not over. There is so much wallpaper in my own sexism, I expect to be scraping it down for years.

I am thinking about a story my daughter told me last year about a teacher who unfairly disciplined her. At the time, I thought my daughter might have been stretching the truth. I am not going to assume that ever again. I want my daughter to know that I am militantly on her side no matter what. I want her to know that she can trust me with stories about adults acting strangely.

I took a break from my work this afternoon to visit the farm where we have a share. The city was going to spray it with Round-Up, a horrible pesticide with potentially lethal ramifications for mammals. But people had banded together to protest. The mayor listened. The organic farms won, and the fields remained organic. I was alone today in the field, to lean forward, choose a sunburst orange tomato, choose another, toss away the cracked ones fill my quart to the brim. I paused to stretch my back and looked up at the sky, something I try to do every day. It’s all we have, really—the sky, the relationships we make, the tomatoes we pick. We don’t know where danger lies until it’s here in our midst. That’s why it’s dangerous. And yet, I keep thinking, “God is in the repair.” I don’t want pesticides in my tomatoes, but neither did I want my friends molested by a trusted school administrator. We don’t always get to choose. But we do get to choose to pay attention, to love our friends enough to listen deeply to their stories, to repair the damage we have done.

Published on September 06, 2013 12:02

August 19, 2013

Beautiful Falcon Ridge 2013

My music project went well through Falcon Ridge, which was its main purpose. I played some guitar every single day, even if it was only a scale, though more often it was an old song, a new song and a Beatles tune. Truthfully, I started with the "a's" and the first "a" for some reason was "A Day in the Life." That's maybe my favorite song, so I lingered on it, learning the bass part as well as reviewing the guitar. I picked up the violin, too, and even contemplated taking some lessons. I also contacted both a guitar teacher and a piano teacher to see if they had time for me. Unfortunately, they both did, which meant it was back on me to have to admit that I didn't really have the time. Every hour seems to be accounted for. Truly,every half hour is accounted for, if you include exhorting my son to stop eating live ants off the sidewalk as the "family time"I have highlighted in my schedule. Yes, a schedule. I have a schedule with the hours of the week graphed out and highlighted with four different colors, and there is no white. I am full to the brim with lovely activities involving beloved people. There is nothing I would want to give up. And still I want more. I want piano lessons and violin lessons and guitar lessons and bass lessons, and I want to write my novel, market How to Be an Adult (it's really truly almost ready, folks), record songs, perform all over the country, take a yoga class with my kids, learn French and raise chickens. I want more time to read great novels like the one I just finished (Colum McCann's newest, TransAtlantic which was so rich and tightly woven that it made me want to quit writing). I want time to learn how to use this app called Buffer that would allow me to post more efficiently. I want to actually read my Twitter feed so I know what the heck to do with Twitter. I want more evenings where the clouds turn dark pink and the air holds the still point. I want to just sit and watch my kids play. Not even to play with them--just to watch. But I don't want to give anything up to slow down enough to do these other things.

My music project went well through Falcon Ridge, which was its main purpose. I played some guitar every single day, even if it was only a scale, though more often it was an old song, a new song and a Beatles tune. Truthfully, I started with the "a's" and the first "a" for some reason was "A Day in the Life." That's maybe my favorite song, so I lingered on it, learning the bass part as well as reviewing the guitar. I picked up the violin, too, and even contemplated taking some lessons. I also contacted both a guitar teacher and a piano teacher to see if they had time for me. Unfortunately, they both did, which meant it was back on me to have to admit that I didn't really have the time. Every hour seems to be accounted for. Truly,every half hour is accounted for, if you include exhorting my son to stop eating live ants off the sidewalk as the "family time"I have highlighted in my schedule. Yes, a schedule. I have a schedule with the hours of the week graphed out and highlighted with four different colors, and there is no white. I am full to the brim with lovely activities involving beloved people. There is nothing I would want to give up. And still I want more. I want piano lessons and violin lessons and guitar lessons and bass lessons, and I want to write my novel, market How to Be an Adult (it's really truly almost ready, folks), record songs, perform all over the country, take a yoga class with my kids, learn French and raise chickens. I want more time to read great novels like the one I just finished (Colum McCann's newest, TransAtlantic which was so rich and tightly woven that it made me want to quit writing). I want time to learn how to use this app called Buffer that would allow me to post more efficiently. I want to actually read my Twitter feed so I know what the heck to do with Twitter. I want more evenings where the clouds turn dark pink and the air holds the still point. I want to just sit and watch my kids play. Not even to play with them--just to watch. But I don't want to give anything up to slow down enough to do these other things.

Amelia played with us at Falcon Ridge, and she also played with her band Belle Amie, a trio of girls in their early teens (actually, not even-two of them are twelve) who blew everyone at the festival away. With us, she picked up the bass for "Jack the Giant Killer," "Back at the Fruit Tree" and "This Town Is Wrong," then swapped with her dad for the electric guitar and rocked out on "Gotta Get Over Greta." My parents drove all the way up from Virginia to see her on Friday, then drove to Long Island for my cousin Luke's wedding, then drove back to Hillsdale to see us on the main stage Sunday afternoon. We played a number of workshops, including one dedicated to the late Eric Lowen who, along with his music partner Dan Navarro, was a lifelong singer songwriter, on the trail, on the circuit. We sang "We Belong," and cried our eyes out as others shared their tributes. We were recorded singing "Which Side Are You On" by a cameraman overlooking the festival from the hillside. Below, my kids, aged 7 and almost 5, discovered their independence, and armed with a walkie talkie and some change earned from busking with their violins, discovered the joys of "shopping" in the festival vendors. Their favorite was a booth where some craftsman or woman was making bows and arrows--the arrow heads being soft pompoms. The weather was fairly kind to us, especially considering past years, and it only rained a little, never soaking the ground and turning the campsites to a mud river.

We sang "Iowa" with Dar on Friday night.

We discovered CJ Chenier at the Dance tent and kicked up our heels.

We discovered CJ Chenier at the Dance tent and kicked up our heels.

My family camped while I escaped to various local hotels in search of hot water and clean sheets, but one night after tucking my kids in, I hurried back to the main stage to see my old friends Dave Matheson and Mike Ford from the late great Moxy Fruvous. As I made my way in the dark with iphone cum flashlight, I heard their clear sharp voices as tight as ever singing Johnny Saucepan." I found a seat by the edge of the stage and drunk in their show, hanging onto every word. If ever there was a band of which I was a total abject fan, it was this one. So sweet to see them still so smart and funny and musical and relevant.

My family camped while I escaped to various local hotels in search of hot water and clean sheets, but one night after tucking my kids in, I hurried back to the main stage to see my old friends Dave Matheson and Mike Ford from the late great Moxy Fruvous. As I made my way in the dark with iphone cum flashlight, I heard their clear sharp voices as tight as ever singing Johnny Saucepan." I found a seat by the edge of the stage and drunk in their show, hanging onto every word. If ever there was a band of which I was a total abject fan, it was this one. So sweet to see them still so smart and funny and musical and relevant.

Some days it seems ridiculous that Katryna and I are still at this. It's been 22 years. We're in our mid forties, and we have full and busy lives even without playing the circuit and making CDs and books. A few days before Falcon Ridge, Tom took the kids to Cape Cod for a midweek vacation, timing it well because he knew that his wife would be completely unavailable to him and his children in the days leading up. Their absence was stunning in its completion. I was able to finish two songbooks for CDs we released in 2008 and 2012 as well as make great progress on my novel, my ebook and some songs I was working on. Plus I cleaned the whole house. I am not even that engaged as a mom--I don't spend a lot of time playing with my kids or taking them on adventures. And still, the time I was afforded by them being gone seemed to stretch on and on. I couldn't believe how productive I was.

This is the theme of our latest CD The Full Catastrophe. "All of our cups are overflowing/Somebody still wants to pour."

That somebody would be me. I missed them terribly and ran down to the car at 11pm the Wednesday night when they returned, carrying my five year old up to bed, lying with my seven year old as she drowsily told me about the beach. My heart ached to have missed that beach trip, to have missed seeing my kids playing with their second cousins whom I have never even met. I think about Sheryl Sandburg exhorting us to lean in, and I think also of the generation of moms who gave up careers so they could go on beach trips mid-week, and I think of Dar and Eric Lowen and the Kennedys and Ellis Paul and Dave and Mike and the community of musicians of whom I'm a part, and some days I feel more like the gave-it-up moms, and some days I feel like Sheryl Sandburg. Either way, it's my life, and I love every minute of it, even the ones where I feel like I can't breathe from the busyness. One of the last workshops we did was all Beatles. We learned "Oh! Darling," via this cool duet by Ingrid Michaelson and Brandi Carlile, and jammed with the Kennedys on all manner of other tunes, including "A Day in the Life" (so my music project totally paid off.) As I sat there with my peers, I could hear the time going by; Eric Lowen and Dave Carter remind us that we never know how long we have to savor this delectable dish called life.

That somebody would be me. I missed them terribly and ran down to the car at 11pm the Wednesday night when they returned, carrying my five year old up to bed, lying with my seven year old as she drowsily told me about the beach. My heart ached to have missed that beach trip, to have missed seeing my kids playing with their second cousins whom I have never even met. I think about Sheryl Sandburg exhorting us to lean in, and I think also of the generation of moms who gave up careers so they could go on beach trips mid-week, and I think of Dar and Eric Lowen and the Kennedys and Ellis Paul and Dave and Mike and the community of musicians of whom I'm a part, and some days I feel more like the gave-it-up moms, and some days I feel like Sheryl Sandburg. Either way, it's my life, and I love every minute of it, even the ones where I feel like I can't breathe from the busyness. One of the last workshops we did was all Beatles. We learned "Oh! Darling," via this cool duet by Ingrid Michaelson and Brandi Carlile, and jammed with the Kennedys on all manner of other tunes, including "A Day in the Life" (so my music project totally paid off.) As I sat there with my peers, I could hear the time going by; Eric Lowen and Dave Carter remind us that we never know how long we have to savor this delectable dish called life. I came home and sent an email back to the piano teacher. I'll start lessons in September.

Published on August 19, 2013 16:48

July 19, 2013

My Music Project

There is something queerly liberating about starting over.

Last week, I followed Elle around her Suzuki Institute, taking notes, practicing iPhone resistance, commiserating with other parents, and mostly being in awe. In awe of the kids, of the teachers, of the parents, of the beautiful commitment that turns ADD youngsters into prodigies. (Actually, they are not at all prodigies; they are simply kids who are fluent in two languages, or becoming so, anyway.)

But what I really thought about a lot was the benefit of structure. Artists, I have found, need more structure than most. Of course we do: we are grappling with the protean forms that come from the bottomless depths of our rivers. My work as a life coach is often about teaching artists how to structure their lives so that they can both create their work and pay their bills without too much angst.

As a child (who had, instead of a Suzuki parent, a tennis champion parent), I spent many hours per day lying in bed spaced out, sitting in a desk, spaced out, even playing tennis spaced out. I was a spacey kid. I was always in my head, dreaming dreaming dreaming dreaming. When I was 13 or so, I read a biography of John Lennon in which he copped to the same crime––only instead of being apologetic, he flaunted this state as the natural, nay necessary state of being an artist.

Still, if one is to be an artist, one has to have some exterior structure going on, or one’s dreams never get written down, or painted, or danced. The stuff needs to get out of our heads somehow. And once out, it needs a container. And it’s in the journey from head to world where art meets craft, and craft needs practice.

I learned practice not from taking piano lessons. I never practiced the piano. Well, maybe the day before the lesson I might go over what the teacher told me to do the week before, but other than that, nada. I learned how to practice from playing tennis. You show up, you get run around the court, you play other kids, you do this a lot and you get better. I got very good at tennis, but when I was 14 I gave it up for the guitar.

I didn’t practice my guitar so much either, at least not in that Deep Practice way Suzuki kids do, but I did play all the frigging time. I got a job as the music teacher for the local day camp and learned about a hundred songs and played from 8:30am till 3, and then went home and spent my evenings figuring out Suzanne Vega and Neil Young songs. And then eventually I was in the band and we played more nights than not. I put in my 10,000 hours that way. (Suzuki is famous for saying "ability is knowledge plus 10,000 times.")

So the Suzuki concept of “daily” is not new to me. I learned that if you want to make growth happen you had to show up every day. I became a writer by writing three pages every day. I became a runner by running a mile or 3 every day. I became a meditator by meditating every day (badly, but still, for 15 years and counting), and I became a musician by playing every day.

As I wrote before, I am in the middle of a Happiness Project (thank you, Gretchen Rubin), and this month’s focus is Music. What I meant by this, back in April when I set my goals for each month for the next year, was that I would focus on some specific music projects in preparation for Falcon Ridge; namely writing two new songbooks to go with our most recent CDs (Rock All Day/Rock All Night, 2008 and The Full Catastrophe, 2012). But after my week at Suzuki Camp I got a new idea.

What if I put as much time and effort into my own music practice as I do with my kids’?

At this camp, there is an elective called “Fiddling.” A fabulous teacher named Sarah Michel taught the kids Irish, Old Time and Bluegrass tunes. On day 2, I asked if I could bring my own violin and try to play along. I played violin for two years, ages 8-9, and probably only ever played the A string and E string, but I do retain that muscle memory. So I played a bunch of fiddle songs and noticed how much fun I was having. Playing music with others is a lot like playing tennis or hockey: you have to be in the moment, focused on your body and hand/eye co-ordination. It’s a game. A really fun game. Good to remember.

What if, I thought, I married my Happiness Project mojo with my (ongoing) Mindfulness Project mojo with my inner musician who is, right now, kind of lost and directionless? As I posted last week, I have no idea what I am going to write next. I need to get back to being that spacey kid again. But I also need a structure.

The piece that most appealed to me about Gretchen’s Happiness Project was the Ben Franklin Virtues Chart aspect. I loves me a chart. So I have made myself monthly charts where I get to check off boxes at the end of each day. I also give myself a mood score to see if there is a correlation between number of boxes checked off and how I am feeling. (There is.) Why not do a Music Project too?

In their Suzuki lessons, my kids have a weekly practice sheet, which is a grid. They get to put stickers in the boxes when they fulfill their little tasks. On the grid: Listening, Scale, Tone, Rhythm, Technique, Review, Working Piece, Polishing Piece, Something Special. Review is the heart of the practice: here is where the new technique really gets practiced. Obviously you can’t get better at your craft when you are trying to bend your brain around a brand new piece. You improve your craft—say you are trying to learn vibrato–– on some Twinkle variation.

Last night my family sat down to dinner and I felt my heart beating hard. I swallowed and then screwed up my courage.

“Guys, I have something to tell you.” They all looked up at me over their corn cobs. I cleared my throat.

"What is Mommy’s job?"

“Musician,” they grunted.

“Yup. And how do musicians get to be better musicians?”

“Practice.”

“Right! And how often do you ever see Mommy practice?”

They looked at each other.

“Never. Right?”

They nodded.

“So I am going to practice from now on, just like you do. And when I practice, I want you guys to let me practice.”

They rolled their eyes. But they didn’t say no.

So here is my music practice:

Every day:

-I play one scale.

-I do a five minute free write on a prompt.

-I play through one Nields song (I am going chronologically. Yesterday it was "Be Nice to Me." Today, "James.")

-I play through one Beatles song, strumming the chords and singing. The next day, I play the bass part. After that, I try to learn any extra parts that are within my musical reach (like the violin part on " Am the Walrus"––but not, perhaps, the violins on "Eleanor Rigby.")

That’s it. I get ½ hour a day. I am putting it first, before exercise, before tidying, before showering. That’s how I know I mean business. I will keep you posted on my progress.

Last week, I followed Elle around her Suzuki Institute, taking notes, practicing iPhone resistance, commiserating with other parents, and mostly being in awe. In awe of the kids, of the teachers, of the parents, of the beautiful commitment that turns ADD youngsters into prodigies. (Actually, they are not at all prodigies; they are simply kids who are fluent in two languages, or becoming so, anyway.)

But what I really thought about a lot was the benefit of structure. Artists, I have found, need more structure than most. Of course we do: we are grappling with the protean forms that come from the bottomless depths of our rivers. My work as a life coach is often about teaching artists how to structure their lives so that they can both create their work and pay their bills without too much angst.

As a child (who had, instead of a Suzuki parent, a tennis champion parent), I spent many hours per day lying in bed spaced out, sitting in a desk, spaced out, even playing tennis spaced out. I was a spacey kid. I was always in my head, dreaming dreaming dreaming dreaming. When I was 13 or so, I read a biography of John Lennon in which he copped to the same crime––only instead of being apologetic, he flaunted this state as the natural, nay necessary state of being an artist.

Still, if one is to be an artist, one has to have some exterior structure going on, or one’s dreams never get written down, or painted, or danced. The stuff needs to get out of our heads somehow. And once out, it needs a container. And it’s in the journey from head to world where art meets craft, and craft needs practice.

I learned practice not from taking piano lessons. I never practiced the piano. Well, maybe the day before the lesson I might go over what the teacher told me to do the week before, but other than that, nada. I learned how to practice from playing tennis. You show up, you get run around the court, you play other kids, you do this a lot and you get better. I got very good at tennis, but when I was 14 I gave it up for the guitar.

I didn’t practice my guitar so much either, at least not in that Deep Practice way Suzuki kids do, but I did play all the frigging time. I got a job as the music teacher for the local day camp and learned about a hundred songs and played from 8:30am till 3, and then went home and spent my evenings figuring out Suzanne Vega and Neil Young songs. And then eventually I was in the band and we played more nights than not. I put in my 10,000 hours that way. (Suzuki is famous for saying "ability is knowledge plus 10,000 times.")

So the Suzuki concept of “daily” is not new to me. I learned that if you want to make growth happen you had to show up every day. I became a writer by writing three pages every day. I became a runner by running a mile or 3 every day. I became a meditator by meditating every day (badly, but still, for 15 years and counting), and I became a musician by playing every day.

As I wrote before, I am in the middle of a Happiness Project (thank you, Gretchen Rubin), and this month’s focus is Music. What I meant by this, back in April when I set my goals for each month for the next year, was that I would focus on some specific music projects in preparation for Falcon Ridge; namely writing two new songbooks to go with our most recent CDs (Rock All Day/Rock All Night, 2008 and The Full Catastrophe, 2012). But after my week at Suzuki Camp I got a new idea.

What if I put as much time and effort into my own music practice as I do with my kids’?

At this camp, there is an elective called “Fiddling.” A fabulous teacher named Sarah Michel taught the kids Irish, Old Time and Bluegrass tunes. On day 2, I asked if I could bring my own violin and try to play along. I played violin for two years, ages 8-9, and probably only ever played the A string and E string, but I do retain that muscle memory. So I played a bunch of fiddle songs and noticed how much fun I was having. Playing music with others is a lot like playing tennis or hockey: you have to be in the moment, focused on your body and hand/eye co-ordination. It’s a game. A really fun game. Good to remember.

What if, I thought, I married my Happiness Project mojo with my (ongoing) Mindfulness Project mojo with my inner musician who is, right now, kind of lost and directionless? As I posted last week, I have no idea what I am going to write next. I need to get back to being that spacey kid again. But I also need a structure.

The piece that most appealed to me about Gretchen’s Happiness Project was the Ben Franklin Virtues Chart aspect. I loves me a chart. So I have made myself monthly charts where I get to check off boxes at the end of each day. I also give myself a mood score to see if there is a correlation between number of boxes checked off and how I am feeling. (There is.) Why not do a Music Project too?

In their Suzuki lessons, my kids have a weekly practice sheet, which is a grid. They get to put stickers in the boxes when they fulfill their little tasks. On the grid: Listening, Scale, Tone, Rhythm, Technique, Review, Working Piece, Polishing Piece, Something Special. Review is the heart of the practice: here is where the new technique really gets practiced. Obviously you can’t get better at your craft when you are trying to bend your brain around a brand new piece. You improve your craft—say you are trying to learn vibrato–– on some Twinkle variation.

Last night my family sat down to dinner and I felt my heart beating hard. I swallowed and then screwed up my courage.

“Guys, I have something to tell you.” They all looked up at me over their corn cobs. I cleared my throat.

"What is Mommy’s job?"

“Musician,” they grunted.

“Yup. And how do musicians get to be better musicians?”

“Practice.”

“Right! And how often do you ever see Mommy practice?”

They looked at each other.

“Never. Right?”

They nodded.

“So I am going to practice from now on, just like you do. And when I practice, I want you guys to let me practice.”

They rolled their eyes. But they didn’t say no.

So here is my music practice:

Every day:

-I play one scale.

-I do a five minute free write on a prompt.

-I play through one Nields song (I am going chronologically. Yesterday it was "Be Nice to Me." Today, "James.")

-I play through one Beatles song, strumming the chords and singing. The next day, I play the bass part. After that, I try to learn any extra parts that are within my musical reach (like the violin part on " Am the Walrus"––but not, perhaps, the violins on "Eleanor Rigby.")

That’s it. I get ½ hour a day. I am putting it first, before exercise, before tidying, before showering. That’s how I know I mean business. I will keep you posted on my progress.

Published on July 19, 2013 17:15

July 9, 2013

Too Many Pots on the Stove

The last thing I should be doing right now is posting a blog. So maybe that's why I need to do it.

I am navigating the world of ebooks, to self-publish my 2008 title How to Be an Adult. The first time around, I had a deal with a local publisher to format the book. This time I am trying to figure all that out myself. Also, I am trying to write songs, and learn the 3 songs I've written so far this year, in time for Falcon Ridge. And I want to publish songbooks to go with our CDs Rock All Day/Rock All Night, and with our CD The Full Catastrophe. For the latter, I have a vision to put together a collection of essays on motherhood culled from this very blog. And I am deep in revisions of The Big Idea, my novel about a family rock band.

And even writing this, I am having trouble breathing.

I know I would be a lot more sane if I simply picked one project at a time to focus on and stopped trying to rotate the hot pans on the stove. But to let any of these projects go feels like death to me.

Add to all this a work schedule and a family schedule that's kept me extremely happy and occupied to the tune of not having a day off since Memorial Day. So on Saturday, Tom sent me to Williamstown, my ancestral home and the birthplace of my band (we got our start at the Williamstown Theatre Festival) for about 22 hours. What did I do? Sat in air conditioning and worked on all my projects. I sang through my new songs, recorded them on GarageBand for Katryna; worked on laying out How to Be an Adult and uploading it to CreateSpace; typed in a new first scene for The Big Idea; walked to the Co-op to eat dinner from their salad bar; and in the morning I went for a run to the graveyard where my grandfather and his family are buried.

Today I spent the day at Elle's Suzuki Institute, which meant I followed her around and took notes, avoided my iPhone, stretched my back a lot and listened to countless kids aged 5-14 playing a huge range of the Classical music canon. It's been beastly hot in New England––and everywhere I imagine––and no one is in an especially good mood. As I made a commitment this year to shake my bad moods, this didn't sit well with me. But the more I tried to "snap out of it," the more unpleasant I found the entire experience. And I kept asking myself, "Why am I not feeling the magic I always feel when I'm here?" Because for the past 3 years, Suzuki Camp has been one of my favorite places to be. I am usually a sucker for the whole package: the play-ins, the awesome teachers from New York, Maine and Boston, the lunches on the lawn, the antics during group class, the camaraderie of both kids and parents. But today, I was just bored and uncomfortable and sick of “Perpetual Motion.”

I'm sick of my own work too, at times. And sick of myself and my inability to pour my everything into just one project. I wish I had a boss, or a life coach, or a really tough friend, or my sister to tell me "Drop this and this and this and focus on that." I wish sometimes that someone would make me choose.

In the middle of the day, after lunch, the whole campus troops over to an old church where kids have their recitals. Over the course of a week, every kid in the camp gets a turn by him- or herself on stage to play a solo. Elle is playing something called “Gavotte from Mignon” by a composer named A. Thomas. It's cool–– and sounds the littlest bit like the theme from NPR. But today she wasn’t playing, so the two of us sat with another family, turned our programs into fans, and took turns fanning each other while we listened to the 13 or so kids get up and take their turn. Some were good, some were beginners, most had that stereotypical Suzuki Glaze in their faces that made me doubt the method way back when I thought I had a choice about my life. That was before Elle grabbed me by the hand at age 3 and dragged me to our current teacher, Emily Greene and insisted on studying the violin with her. And pretty much, until today, I haven't looked back or regretted any of it. Suzuki has given a lovely structure and flow to our lives, and I mark my days by the CD we put on for the kids to listen to in the morning, and the check boxes on their weekly assignment sheets as we go through our practice items together every day (Suzuki says, "We only practice on the days we eat.") As I listened to the kids play, I felt listless and hot and despairing. Completely uninspired. My new songs are ok, but they are all over the place. There is no core to them, nothing that links them together in any way. I can't see our next CD. I have no idea in what direction to write.

The last kid to play was a 12 or 13-year-old boy. He put a chair down on the stage and sat down with his cello. The director of the institute, who doubles as the piano accompanist, left her post; the boy began playing a movement from the sixth of Bach's suites for unaccompanied cello: the Allemande in D. He played with his eyes closed, as though he were as much a listener as a player. After a minute, I poked Elle who was busy fanning her neighbor. "Listen to this," I whispered, and she did, sitting up in her pew for the rest of the eight-minute piece. The room held the music tenderly: the bruised sentiment of a man who had recently lost his wife. I was absorbed into the music, forgetting about my own artistic woes, forgetting about my big problem about how to get out of my bad mood, forgetting the heat, forgetting the glazed faces. I rode the current of the music. And when the boy pulled that last lovely D out of his cello, I rose to my feet and applauded, tears spanking my eyes.

The rest of the day I was more present for what I love about Suzuki and this camp in particular. Elle took a fiddle class with a remarkable teacher named Sarah the Fiddler who explained to the kids that the great thing about fiddling is that when you make a mistake you get to incorporate it into your playing and figure out why it works: which is basically my modus operandi. Then there was orchestra, where the amazing Tyson somehow gets a group of kids who sound like they are each playing the “Star Spangled Banner” at a different speed to pay attention enough to him to get them, by the end of the week, to sound coherent. And he does this without ever yelling. I knew the day was a success when I told Elle it was time to go, and she narrowed her eyes suspiciously. "Is every single other kid at this whole camp going home too?" I said yes. And only then did she say, "Well, OK" and followed me out the door.

Maybe this is what being an artist in midlife is all about: moving the different pots around. Maybe it’s about doing the thing that calls you in the moment, even if different things yell at different frequencies. As I wrote a few months ago, it’s become clear to me that my mission is not, after all, to write some memorable songs that will outlive me and be sung by kids 100 years from now on the back of school busses, or whatever it is they might be driving. My mission is to have a good life and to spread around some of whatever it is I’ve been taught so that others get some of the goods as well and get a chance to live as well and joyfully as I have lived. Process over product has been my motto of late. So this evening I played with my kids. We got wet, and I picked a bouquet of flowers from my garden. And instead of working on either of my books or trying to write a new song, I wrote this post. Tomorrow I will pack our cooler and violin and music stand and we’ll go back for another day of Suzuki, and let my own projects simmer on the stove.

I am navigating the world of ebooks, to self-publish my 2008 title How to Be an Adult. The first time around, I had a deal with a local publisher to format the book. This time I am trying to figure all that out myself. Also, I am trying to write songs, and learn the 3 songs I've written so far this year, in time for Falcon Ridge. And I want to publish songbooks to go with our CDs Rock All Day/Rock All Night, and with our CD The Full Catastrophe. For the latter, I have a vision to put together a collection of essays on motherhood culled from this very blog. And I am deep in revisions of The Big Idea, my novel about a family rock band.

And even writing this, I am having trouble breathing.

I know I would be a lot more sane if I simply picked one project at a time to focus on and stopped trying to rotate the hot pans on the stove. But to let any of these projects go feels like death to me.

Add to all this a work schedule and a family schedule that's kept me extremely happy and occupied to the tune of not having a day off since Memorial Day. So on Saturday, Tom sent me to Williamstown, my ancestral home and the birthplace of my band (we got our start at the Williamstown Theatre Festival) for about 22 hours. What did I do? Sat in air conditioning and worked on all my projects. I sang through my new songs, recorded them on GarageBand for Katryna; worked on laying out How to Be an Adult and uploading it to CreateSpace; typed in a new first scene for The Big Idea; walked to the Co-op to eat dinner from their salad bar; and in the morning I went for a run to the graveyard where my grandfather and his family are buried.

Today I spent the day at Elle's Suzuki Institute, which meant I followed her around and took notes, avoided my iPhone, stretched my back a lot and listened to countless kids aged 5-14 playing a huge range of the Classical music canon. It's been beastly hot in New England––and everywhere I imagine––and no one is in an especially good mood. As I made a commitment this year to shake my bad moods, this didn't sit well with me. But the more I tried to "snap out of it," the more unpleasant I found the entire experience. And I kept asking myself, "Why am I not feeling the magic I always feel when I'm here?" Because for the past 3 years, Suzuki Camp has been one of my favorite places to be. I am usually a sucker for the whole package: the play-ins, the awesome teachers from New York, Maine and Boston, the lunches on the lawn, the antics during group class, the camaraderie of both kids and parents. But today, I was just bored and uncomfortable and sick of “Perpetual Motion.”

I'm sick of my own work too, at times. And sick of myself and my inability to pour my everything into just one project. I wish I had a boss, or a life coach, or a really tough friend, or my sister to tell me "Drop this and this and this and focus on that." I wish sometimes that someone would make me choose.