Christopher Priest's Blog, page 11

October 14, 2014

His Beast Yet

Bête is a novel of well chosen sly references – lines from pop songs, other books, puns on cultural icons, TV shows, bits of well known slang – but one of the slyest, and perhaps best chosen, since we know Adam Roberts is an English academic, is on the last page. ‘This is the best of me,’ says Roberts on his Acknowledgements page. Is that an acknowledgement, or a boast? Interest aroused, I go in search.

Bête is a novel of well chosen sly references – lines from pop songs, other books, puns on cultural icons, TV shows, bits of well known slang – but one of the slyest, and perhaps best chosen, since we know Adam Roberts is an English academic, is on the last page. ‘This is the best of me,’ says Roberts on his Acknowledgements page. Is that an acknowledgement, or a boast? Interest aroused, I go in search.

It takes some tracking down, but the remark comes from Sesame and Lilies, by John Ruskin. (It was also quoted by Edward Elgar on the manuscript score of The Dream of Gerontius.) Here it is in full, in quotation marks because Ruskin placed it in them:

‘This is the best of me; for the rest, I ate, and drank, and slept, loved, and hated, like another; my life was as the vapour, and is not; but this I saw and knew: this, if anything of mine, is worth your memory.’

The context is Ruskin’s definition of the difference between the sort of book that conveys news or amusement and a ‘true’ book, which is written for permanence. Of permanence, Ruskin says, ‘The author has something to say which he perceives to be true and useful, or helpfully beautiful. So far as he knows, no one has yet said it; so far as he knows, no one else can say it.’ Unless I am completely misinterpreting Adam Roberts’ intentions, I take this to mean he was aiming high with Bête, a book no one else can or would write, worthy of our memory.

That’s a classy boast, and I like it. After one novel a year for the last decade and a half, and heaven knows how many parody novels, he’s entitled to that. But is it the best of him?

It’s an unusual novel, unusual even for Roberts, whose fiction has never been what might be called expectable, but also unusual within the genre of fantastika. Like much of his work it has a distinct satirical streak, but unlike the earlier novels of his I’ve read, which depended on exact but often dodgy plotting, it is almost sluttishly freeform. It therefore escapes the need to make sense in plot terms. In fact, there is hardly any discernible plot – just a sequence of events, many of which are static or internalized, and the rest of which are the sort of long rambling conversations, full of stupid generalizations and cheerful abuse, overheard in a pub.

What will happen in the course of the story seems fairly predictable, once you understand the parameters of the set-up. Animals have gained the use of words, through the fitting of an AI chip. With the gaining of words comes an animalistic point of view, and, concomitantly, the power of persuasion. It’s not long before they are running things: e.g., farms are worked by humans, with the beasts occupying the farmhouse, so to speak. A shade of Orwell’s Animal Farm (1945) is being summoned of course, and Adam Roberts, one of our most intelligent and well read writers, knows exactly what he is doing. The famous last line of Animal Farm is one of the many cultural references that are scattered throughout the book.

The sequence of events is not all that exciting: the oddly named narrator, Graham Penhaligon, a former abattoir worker, butcher and farmer, lives rough in and wanders around the Thames Valley. He is in squalid circumstances for most of the story: unwashed, starving, sleeping rough in Bracknell Forest, killing animals for food – he spends half the book crippled by a damaged Achilles tendon. He is living on the fringe of a weird and dysfunctional society, where isolated houses, villages and suburban towns are empty (there’s an ebola-like epidemic called Sclera killing humans in the millions), while the M4 motorway is a hell of rushing vehicles and roadside squatters. Canny animals (i.e. those fitted with AI chips) are fighting back, and in Graham’s case biting back. He’s a high-profile enemy to the new master race, having notoriously slaughtered a talking cow in the first five pages of the novel. He meets and falls in love with Anne, a cancer victim, and after her death, a haunted and lonely man, he seeks a sort of revenge on the world until another kind of solution is offered to him.

So it’s an unusual novel, but does that make it any good? Not all unusual books are. Most of us would accept Animal Farm and Russell Hoban’s Riddley Walker (1980) as good novels — properly referenced here, as their precedence is clear — but Will Self’s recent modernist novel Umbrella (2013) was both unusual and more or less unreadable. One also remembers with a shudder some of the modernist attempts at New Wave stories from untried SF writers in the 1960s. In large, the genre of science fiction is in formal terms unadventurous, employing conventional narratives and plot structures, depending more on its exploration of ideas than deep characterization or beautiful or experimental prose, so a book like Bête tends to stand out purely for its way of being told.

As anti-heroes go, Graham Penhaligon is a consummate act. His narrative is remarkable for his self-loathing, cynicism, intolerance, stubbornness and gritty determination. When he loses the love of his life the contrast in his feelings is telling. But most of the time his attitude and manners are appalling, and you can’t help liking him for that:

Eventually a junior officer came to fetch us. ‘You all right going upstairs with that stick?’ he asked me, in a voice plumped with the peculiar smugness of the very posh. ‘It’s just that the elevator is on the fritz.’

‘I can walk,’ I replied. ‘Unless you fancy giving me a fucking piggy back, lard-face.’

The answer to my question above (‘does that make it any good?’) is yes, but I think Bête is good mainly in what it tells us about the progress of the writing of Adam Roberts, rather than as a novel in itself. Although it is clearly likely to be one of the stand-out novels of 2014, I believe in overall terms Bête’s unusualness of attack is not enough to counteract the feeling of familiarity created by the smallness of its scale, the limits of its ambition. In the end, the society is drawn too vaguely, the revolution amongst the animals is unconvincing and slightly risible, the puns too many, the references to pop music and TV too dating, the events too meandering. However, the real reason to read this book is to see a good writer getting better, and doing so in unexpected and uncommon ways. The prospect of a new novel from Roberts is always a matter of expectation, but I believe after Bête we should be genuinely keen to see what he will come up with next.

Bête by Adam Roberts. Gollancz, 2014, ISBN: 978 0 575 12768 5, £16.99

September 30, 2014

Let the notebook be the judge

Ian McEwan and I are almost contemporaries. He is five years younger than me, and his first book was published about five years after mine. The mid-1970s was a good time for a young, apparently radical writer to appear, because around then several literary commentators had been perceiving there was a vacuum, where no young or apparently radical writers were coming through. McEwan, an alumnus of the University of East Anglia’s Creative Writing Course, then emerged and was greeted as the new best hope. Like a lot of people I read his first couple of books (both of them story collections), and I was impressed. I saw him as a bit of a literary rebel, independent-minded, someone who wasn’t going to be easily categorized. He was clearly gifted, had a nice sense of the macabre or disgusting, and his use of English was excellent.

I was not alone, though, in noticing that some of his stories bore remarkable similarities to stories by other writers. The first of these was ‘Dead as They Come’ (1978), which appeared in his second collection, In Between the Sheets (1978). This was almost exactly the same story as J. G. Ballard’s ‘The Smile’, published two years earlier. Several people pointed out other alleged examples of McEwan similarities, but the most publicized from this period was his first novel, The Cement Garden (1978), found by many to be a retread of Julian Gloag’s Our Mother’s House, published fifteen years earlier. Gloag himself was so irate about his work being pilfered that he wrote a novel based on McEwan’s assumed plagiarism, called Lost and Found (1983).

McEwan himself of course denied being a plagiarist. At the time I believed him, but I also thought that he was guilty of something almost as bad for a writer serious about his work. He wasn’t imagining properly, not thinking deeply enough.

He kept producing stuff that was like other writers’ work. It happens from time to time to many writers, but most of those coincidences are one-offs. McEwan has been dogged by accusations of copying all his career – it’s beyond coincidence. So what was going on if it wasn’t plagiarism? I came to the conclusion he had a lightweight imagination: he would see something on TV, or he would read a newspaper article, or hear an anecdote of some kind, then think he could get a story out of it. If you respond in such a shallow way, it’s inevitable that somewhere else in the world another writer will have had the same ‘inspiration’. Later I discovered from a television interview that McEwan carried his notebook everywhere and filled it with thoughts – some of them were his own, but many of them were extracts he found in other books. Nearly all writers use notebooks, so that doesn’t make him unusual. But apparently McEwan neglected to note the source – he made the excuse that years later he might come across something in one of his notebooks and not realize it was by another writer.

In recent years his copying has become even less ashamed than before. He was castigated in the press for copying out (and minutely modifying) passages from Lucinda Andrews’ memoir No Time for Romance, and including them in his novel Atonement. McEwan wisely kept his head down and waited the storm out, which duly blew over, but the plagiarism remains like a malignant lump in a sensitive part of the body. (Atonement is one of his most widely read novels.) When I reviewed his novel Solar (2010), I pointed out that a central plot-turn was obviously based on an identical sequence in the film Groundhog Day. Later in the same novel, he reported as a real event a familiar urban myth (the one about unwittingly sharing chocolate biscuits, or potato crisps, with a stranger in a station buffet), but on second thoughts he made a belated ham-fisted attempt to convert it into a serious point about industrialization.

McEwan’s new novel

And now here we are with his most recent novel, The Children Act, and he is still revealing either his lightweight thinking, or his willingness to copy stuff down and transfer it to his novel. It’s done a bit more subtly this time, and his source is impeccable, but he remains in literary terms a copyist.

The plot of the novel, though, is original to McEwan. Here it is: Fiona Maye is a middle-aged woman whose husband suddenly announces that he wants to have an ‘ecstatic’ sexual affair with a younger woman. He walks out on her. Fiona immediately has the locks changed. A few days later she finds her chastened husband sitting in the hall outside their apartment, his possessions scattered around. She reluctantly lets him back in, and they co-habit in separate rooms. By the end of the book they have reconciled, and are sleeping together again.

That’s a thin plot for a 200+ page novel, so there must be something more? Of course: there’s a sub-plot, and this concerns Fiona’s job. She is a High Court judge in the Family Division, and she has to make a tricky decision about an adolescent boy whose parents are Jehovah’s Witnesses. He is dying of leukaemia. The parents will not agree to the blood transfusion that might save his life, which the doctors feel they have a Hippocratic obligation to provide. Fiona finds for the doctors, the transfusion goes ahead and the boy survives. She reads his romantic poetry. He begins stalking Fiona and on catching up with her asks if he could move in and live with her. They share a brief but passionate kiss. Afterwards, Fiona thinks better of this, and cuts off contact. A few months later she hears that after the boy turned 18, and was therefore capable of making his own decisions, the leukaemia returned. He himself refused another transfusion, and died.

This sub-plot is much more complex and interesting than the main plot (although it does include an overlong description of court proceedings, page after page of barrister characters, legal references, applications, statements, witnesses, meticulous post-Rumpole stuff without John Mortimer’s wit), but a sub-plot it remains.

Unfortunately, the dying Jehovah’s Witness is not a McEwan invention but an actual case, presided over by a leading Appeal Court judge in 2000. By McEwan’s own admission, freely made and repeated, he met the judge socially, rather admired the elegant linguistic style of top judges, made friends with the judge and listened avidly to his recollections of tricky decisions made in the past. (If you’re wondering how this formerly radical and independent literary firebrand came to meet top judges socially, the story is here: ‘Some years ago I found myself at dinner with a handful of judges’. As one does.)

Of course, McEwan attends to details, introduces differences – the real boy was a football fan and not a poet, the judge took him to a football match, not a quiet moment in a judges’ lodgings – but the story is the same and it carries the same literary freight as any extended passage in a novel. In this case it is in literary terms a fake.

It can be argued, and McEwan would presumably argue, that all novelists research their subjects, take notes, interview people who have had experiences, and that in this he is no different from any other novelist. There is a difference, though. A serious writer will consider the information gained from research, digest and absorb it, think about it and wonder about it, seek a significance that is greater than that of mere plotting, look for any relevance that might exist on a symbolic or unconscious level, then write it from the heart. Ian McEwan does none of this: he copies down a story, fiddles around with names and a few details, then presents it as his own, written from the head. (There is a back-page acknowledgement to the real judge, so that’s OK then. I wonder if the learned judge realizes McEwan made a similar back-page acknowledgement in Atonement, to Lucinda Andrews?)

Ian McEwan is routinely described as Britain’s leading contemporary novelist. Could that possibly be true?

The Children Act by Ian McEwan. Jonathan Cape, 2014, 213pp, ISBN: 978-0-224-10199-8, £16.99

September 27, 2014

Cheltenham Literary Festival

I shall be appearing next weekend (Saturday 4th October) at the Cheltenham Literary Festival, on a panel discussion about the ever-cheerful subject of dystopian fiction. With me will be Jane Rogers (who recently won the Arthur C. Clarke Award for her novel The Testament of Jessie Lamb; also longlisted for the Man Booker) and Ken MacLeod (whose novel Descent, his eighth, was published earlier this year and will be out in paperback in November). The discussion will be moderated by the multi-award winning critic Cheryl Morgan. Details of the event can be found here.

I have been brought in at fairly short notice as a replacement for Brian Aldiss, who is indisposed – one fervently hopes not too greatly indisposed. I also note that the panel was originally to be moderated by my colleague Adam Roberts, but for reasons unknown (to me) he has pulled out. I wonder if word reached him that I am currently reading his new novel, Bête? Surely not – it’s the best of his I’ve read. So far.

September 10, 2014

Graham Joyce

My obituary of Graham will be published in the Guardian. An advance copy is online here. I found the news of his sudden death distressing.

September 7, 2014

A Kind of Lucky

When I was still a teenager, in search of cheap thrills (as I hoped and expected), I bought a Penguin paperback edition of Stan Barstow’s novel A Kind of Loving (1960). I remember enjoying it – but not for the sexy bits, which were few and far between and in their depiction of youthful callowness a bit too close to home to be either educative or erotic.

The film directed by John Schlesinger came out soon afterwards. The sexy bits in this were a bit more explicit (though not much more). I was interested to see that many of the exterior shots were filmed in Stockport, a depressing post-industrial town close to where I lived as a child. For some reason the Luftwaffe had failed to flatten Stockport, so its terraced slums and empty mills and former factories remained standing until at least the early 1960s. IMDb describes some of the filming locations as ‘Greater Manchester’, which I think now includes Stockport. I’m certain that the final scenes in the film were shot in a place called Gas Lane, next to the gasworks and close to Mersey Square in the centre of the town, which even in the context of Stockport’s neglected Victorian areas was picturesquely decrepit.

(I suppose I should add that since those days Stockport’s slums and horrible old gasworks have all been demolished, and it has no doubt become a lovely place to live.)

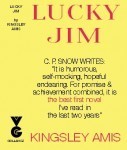

Stan Barstow, a good writer if somewhat neglected these days, was one of those post-war novelists dubbed by the press ‘angry young men’. They were the immediate literary context in which I began writing: I read several of the books then current, by John  Braine, Alan Sillitoe, Keith Waterhouse, David Storey and, of course, Kingsley Amis. His novel Lucky Jim (1954) is often said to have started that particular literary genre, even though it is different in tone from all the others, and a distinct cut above them. Although it is by far Amis’s best-known novel, and probably brought him more money than any of the others, it is not in my view his best. Some of his later novels are written more subtly (unsurprisingly), and in many cases are much funnier and their satire is more effective. However, it remains a favourite from that period.

Braine, Alan Sillitoe, Keith Waterhouse, David Storey and, of course, Kingsley Amis. His novel Lucky Jim (1954) is often said to have started that particular literary genre, even though it is different in tone from all the others, and a distinct cut above them. Although it is by far Amis’s best-known novel, and probably brought him more money than any of the others, it is not in my view his best. Some of his later novels are written more subtly (unsurprisingly), and in many cases are much funnier and their satire is more effective. However, it remains a favourite from that period.

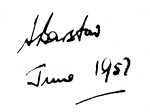

The other day I bought a secondhand hardback of Lucky Jim on the internet. Not a collector’s item in the usual sense (it is from the twelfth impression, printed fifteen months after the first edition), but a nice copy in undamaged binding. I was pleased to find it. I was even more pleased when it arrived in the mail: from the signature inside the front cover it turns out to have been Stan Barstow’s own copy. His signature is dated June 1957.

The other day I bought a secondhand hardback of Lucky Jim on the internet. Not a collector’s item in the usual sense (it is from the twelfth impression, printed fifteen months after the first edition), but a nice copy in undamaged binding. I was pleased to find it. I was even more pleased when it arrived in the mail: from the signature inside the front cover it turns out to have been Stan Barstow’s own copy. His signature is dated June 1957.

Everything joins up in the end.

August 6, 2014

The Best Brits?

There are twenty short stories in this anthology, which is called The Best British Short Stories 2014: nearly all of them are good or interesting or unusual, deserving to be in a book with this title, nearly all are by writers whose work I had not previously come across. The publisher is Salt, the editor is Nicholas Royle.

Three of the stories are of outstanding quality, each one of which would alone justify the cost of buying the book.

“Getting Out of There” by M. John Harrison (first published as a chapbook by Nightjar Press – a Nick Royle imprint), is a story set in what sounds and feels like my former hometown Hastings. The sceptical, defensive mood of the seaside town on its uppers is accurately if selectively caught. The two characters have a marginal, edgy, entirely believable relationship, fleetingly based on knowing each other years before when they were kids. They both reek of authentic Hastings-ness. Mike Harrison is writing better than ever. His reputation seems overshadowed by his contemporaries – Kureishi, Swift, McEwan, etc – but they are shallow, minor, facile writers in comparison.

“The Faber Book of Adultery” by Jonathan Gibbs is the first story in the book, and it set a standard I thought would be difficult to match in what followed. A middle-aged writer seduces (or is seduced by) his best friend’s wife. They do it standing up, leaning against a bookcase. Perhaps that makes the story sound unoriginal, but the delicacy and natural observation of the writing makes the story exceptional. The sub-text is the man’s rambling, almost disorganized thoughts about books, the adultery that is always in them, the way adultery is written. Books are sexy. I particularly liked the description of a book pulled away from a shelf that is too tightly packed with titles: “When it came free, almost with a pop, the books alongside seemed to sigh into the space it left, their pages filling with air.” The story was first published in Lighthouse 1.

The book concludes with a story as good as, or even better than, the Gibbs. It is “Barcelona” by Philip Langeskov, first published by Daunt Books. A man plans a surprise anniversary celebration for himself and his wife, in Barcelona. In spite of several minor worries and problems – pre-existing plans, lost baggage at the airport, the presence of his wife’s former lover in Barcelona, a sudden illness – they arrive there more or less intact, and the holiday goes ahead. It is another story about the effects of literature: Langeskov riskily summons the ghost of Graham Greene, specifically in a short story he reads on the plane, “The Overnight Bag”, which describes a not dissimilar European flight. The uncertainties of the Greene story resound through the visit to the Catalonian city. I think the risk Langeskov took came off: “Barcelona” is a sort of post-Greenean study of a loving marriage, with its nervous ambiguities and shadows. From beginning to end the reader senses unease, things about to go catastrophically wrong, the impact of the past not fully comprehended.

The Best British Short Stories 2014, edited by Nicholas Royle. Salt Publishing, 2014, 240pp, ISBN: 978-1-907773-67-9, £9.99

July 28, 2014

The Way Ahead

A man is seeking an appointment he has to keep. He is inside a vast modernist structure, made of concrete and glass, with unsignposted stairwells and unobliging elevators. Other people are present: tourist groups, businessmen, transient visitors. Meeting rooms have long tables and reconfigurable walls to make the rooms into whatever size, shape and function is necessary. Abstract paintings hang on every wall. Members of staff are present, unfailingly courteous and blandly unhelpful. There are hints and suspicions of close personal contacts: rooms where people are eating, where there is a dance floor, where bedroom doors are firmly closed and labelled Do Not Disturb. Offices are glassed-in, or set up as boxed workstations. A motorway runs past. Could this be a hotel? Or a hospital, an office block, an airport terminal, a convention centre?

The images come from a masterpiece of the cinema, these days a forgotten and largely unseen one: Playtime. Three years in the making, and then delayed by several post-production snags, Playtime was eventually released in 1967, starring and directed by the French comedian Jacques Tati. It was then the most expensive film ever made in France, but it did not receive the worldwide success it needed to recoup the expense of filming, and Tati was bankrupted by it. It is rarely seen these days. Although Playtime is available on DVD, the original 70mm frame is cropped, and there have been cuts made to the immense running time. However, with the hindsight of nearly half a century it can be seen as a brilliant foresight into the worst and most soulless aspects of our modern life.

Playtime was made at roughly the same time as two other comparable French films – Jean-Luc Godard’s Alphaville (1965), and Chris Marker’s La Jetée (1962), although the delays meant it came out some time later. All three films have a distinctly Ballardian flavour – not a coincidence, because J. G. Ballard’s work has always been highly regarded in France.

To say that Will Wiles’s new novel The Way Inn is strongly reminiscent of Playtime is intended as a compliment. The narrator, the protagonist, has the symbolic-sounding name of Neil Double. Double is a professional conference-goer, standing in for middle-grade executives who either do not want to go to the conference, or cannot. He attends the symposia on their behalf, takes notes and reports back. This is his job, and he moves from one hotel and conference to the next, frequently running into the same individuals, and always encountering the same types of people. He has relationships with some of them: he knows which of the other attendees are bores or pests, and he is constantly interested in the women he tries to pick up.

However, Double’s true passion is hotels. He loves hotels, everything about them: the furniture, the abstract paintings, the cuboid armchairs, the TV screen that displays an electronic welcome, the hum of the air-con, the room-service pan-seared salmon, the electronic door key that stops working if you carry it next to your mobile phone, and so on. He also relishes the environment of the modern business hotel: the adjacent motorway, the half-constructed new buildings next door and the muddy areas which will be developed next, the vast parking lots, the nearby airport and its lights, the attached conference centre that can only be reached by courtesy bus. Wiles describes all this with economy and precision, almost a litany of the details of that over-familiar if faintly repellent world of the chain hotel. Anyone who has stayed at the Radisson next to Heathrow Airport (location of several SF conventions in recent years) will recognize the endless corridors, the mile after mile of corporate carpet, the soundproofed windows, the view from those windows across concrete to nothing of human scale, the ease with which you can get lost in the identical corridors and landings and the concomitant habit of always taking the same, safely memorized route to your room, the particular type of bland “international” cooking, the inoffensively abstract paintings, the sense of being surrounded by a Ballardian urban wilderness which you cannot enter or understand, and which will endanger you if you try to walk through it or traverse it.

I have summoned the spirit of J. G. Ballard a couple of times, not accidentally. The Way Inn strikes me as the first authentically post-Ballardian vision of the world as it has become and as it is going to continue to be. Towards the end of his career, Ballard produced a couple of social satires: Millennium People (2003) and Kingdom Come (2006), with discernable elements of social satire in the two much stronger novels that preceded them: Cocaine Nights (1996) and Super-Cannes (2000). Will Wiles has taken up the satire where Ballard left off, while joyfully reviving memories of the great Ballard novels from an earlier period: The Drowned World (1962), Crash (1973) and Concrete Island (1974).

There are also Ballardian echoes in the way Wiles characterizes women (in particular the dominant, Amazonian and sometimes enigmatic figure of the hotel para-manager Dee) – there is a constant sense of male sexual awe, without anything ever happening. (Not true of Crash, though!) Wiles’s dialogue too has that odd Ballard characteristic: an errant, oblique, declarative, almost shouted way of coming at you, non-realist but also mundane and worldly. It gives the novel the weirdest feeling, a sense that there is more going on than you think, and then you find out that there is. The final Ballardian touch I will not spoil, as the pleasure in revealing it should be Wiles’s, not mine, but I was reminded happily of one of Ballard’s Borgesian short stories published in 1982. I’ll leave it to others to trace the reference, but to narrow the search the story I’m thinking of was included in his collection War Fever (1990).

I loved The Way Inn, read it with endless pleasure and interest, and am delighted that in this year, apparently doomed to be eponymed by a class of emergent young science fiction sensation-mongers, a mature, expert and wonderfully original talent has appeared in the person of Will Wiles. For me, The Way Inn is the most satisfying and radical new novel I have read so far this year, way ahead of the rest.

The Way Inn by Will Wiles, Fourth Estate, 2014, 343pp, ISBN 978-0-00-754555-1, £12.99

July 16, 2014

Worldcon schedule

Here is my programme schedule for the London worldcon, Loncon 3. We are planning to arrive on Thursday afternoon, 14th August, leaving on the Monday morning. Nina has listed her own programme items here – there is only one unfortunate clash of same-time scheduling between us (13:30 on Sunday). Everything in italics is from the convention’s schedule.

Friday 18:00 – 19:00 – In Conversation: Naomi Alderman and Christopher Priest

Every 10 years, Granta publishes a list of “The Best of Young British Novelists”; and every so often, a writer whose work includes the speculative and fantastic gets included. Christopher Priest was included in the 1983 list, while Naomi Alderman made the 2013 list; for this item they will discuss their work and careers, and ask to what extent literary values and attitudes to “genre” stories have changed over time.

Naomi Alderman, Christopher Priest

Friday 21:00 – 22:00 – You Write Pretty

Beauty is in the eye of the beholder, they say, so let us behold some fine fantastical sentences. Our panel have each picked a sentence, and will have a chance to make their case for why theirs is the fairest of them all — but it will be up to the audience to decide.

Geoff Ryman (Moderator), Greer Gilman, Frances Hardinge, Christopher Priest, E. J. Swift

Sunday 11:00 – 12:00 – Becoming History

In a review of Kate Atkinson’s Life After Life, John Clute wrote, “It is not easy — it should not really be feasible — to write a tale set in twentieth century that is not a tale about the twentieth century.” A number of other recent books, including Peter Higgins’ Wolfhound Century, Christopher Priest’s The Adjacent, and Lavie Tidhar’s The Violent Century, are also ‘about’ historicising the near-past in this sense. How is the fantastic gaze operating on the twentieth century? Do we have enough distance to see it clearly yet?

Graham Sleight (Moderator), John Clute, Peter Higgins, Elizabeth Hand, Christopher Priest

Sunday 13:30 – 15:00 – Looking Back On Anger: remembering 70s sf in the 21st century

Almost 30 years on from Jeanne Gomoll’s “Open Letter to Joanna Russ” , this panel will look at how the science fiction of the 70s is remembered today. Which works have stayed in the public eye, and which have faded away? Whose commentary still speaks to us, and what was the conversation like back then? What has proven to be problematic, and what remains unresolved?

Graham Sleight (Moderator), Jeanne Gomoll, Pat Murphy, Lesley Hall, Christopher Priest

Sunday 15:00 – 16:30 – SF and the English Summer

Summer is the time for picnics, discovering the countryside and falling through portals, a rainy summer day sends us into the far reaches of the old house. Winter brings mystery, spring brings sacrifice. To each season there is an adventure. The panellists will discuss the “traditional” English weather, its role in fantasy and the effect of Climate Change on our perennial topic of conversation. Bring your own umbrella and sun block.

Caroline Mullan (Moderator), Prof Euan Nisbet, Christopher Priest, Jo Walton

June 24, 2014

RIP Felix

In 1967 I was living in a small basement flat in Fulham Road, London. One of the people who lived there too (I shrink from the word ‘flatmate’) was the millionaire publisher, Felix Dennis, who died at the weekend. He was neither a millionaire nor a publisher when I knew him, but a drummer in a band.

The flat was close to the epicentre of what the American press called ‘Swinging London’, and all that hippie and flower-power stuff now identified with the 1960s was going on around us. Most of it passed me by: I wanted to be a writer and was wrapped up in that, endlessly working at my typewriter.

There were four of us originally living in the flat: myself and Graham Charnock, and two others (who remain nameless). When one of these other two could stand living there no longer (he was having to share a room with the second unnamed one, another millionaire-publisher-to-be, for whom the phrase ‘personal hygiene’ would be entirely inappropriate), Felix Dennis took his place. After that, Graham and I had living with us two people who never cleaned anything, never washed themselves, never flushed the toilet or ever changed their underclothes. I already knew Dennis as a regular visitor to the flat, sometimes staying over: he was uncouth, scruffy and unintelligent. He had a sly, aggressive and cunning manner. He was a heavy drinker and a persistent user of drugs. A few weeks earlier we had had a burglary at the flat, which the local police never solved but said it had all the signs of an inside job. Graham and I were both opposed to Dennis moving in, but there were no alternatives. He came in, bringing his faux-hippie lifestyle and mates with him. Life in the flat quickly became untenable, and a few weeks after Dennis’s arrival I too moved out, but not before a rapidly deteriorating situation culminated on one memorable night, with Dennis threatening me and Graham Charnock with a knife.

He later became famous in the media when he and two others were charged with several offences, including conspiracy to corrupt the morals of minors (for which he was found not guilty) and an offence under the Obscene Publications Act (for which he was jailed). The conviction was later quashed on appeal. He went into magazine publishing and rapidly became rich. During the 1980s I was running a small software company with David Langford, and part of my job was to buy advertising space in computer magazines. We had a monthly spend in the thousands of pounds. I routinely received canvassing phonecalls from advertising departments at these magazines, but whenever one of the calls was from a Dennis magazine I invariably refused to buy space. Because we were advertising everywhere else, one day I took a call from the advertising director at Dennis Publishing – she wanted to know why we would not advertise with them. ‘Because in 1967 your boss tried to murder me with a knife,’ I said. The hilarious reaction from this hapless woman was, to say the least, intriguing. Later, when she was back in control of herself, she said in an understanding voice that we would never be bothered again. We weren’t. In 2008 Felix Dennis bragged to a reporter from the Times that he had murdered a man by pushing him off a cliff. When it became clear that the police were interesting themselves in the incident, Dennis hastily withdrew the claim, saying he had been drunk when talking to the newspaper.

He later became known as a philanthropist, tree-planter and poet. I have no knowledge or opinion of any of that. He suffered some terrible illnesses in later life, and in recent years was a victim of throat cancer, which eventually killed him.

May 16, 2014

House Clearance

Fay Ballard at the Eleven Spitalfields gallery

The artist Fay Ballard has an exhibition in London called House Clearance. This consists of a large number of touching and beautifully executed drawings and paintings inspired by the familiar clutter she found when clearing out the house of her father, J. G. Ballard. We were fortunate enough to visit the gallery yesterday, where Fay herself was present. Although I had met her father several times over the years, I had not met Fay before and it was a great treat to sit in the peaceful gallery and hear her memories of life at home with him.

Information about the gallery Eleven Spitalfields can be found here — the exhibition is continuing until 27th June 2014. And Fay’s own website has many of the images to be glimpsed online — but are no substitute for seeing the originals.

Christopher Priest's Blog

- Christopher Priest's profile

- 1073 followers