Alia Amir's Blog: Languaging, literature, culture and landscape, page 2

August 15, 2023

Weaving Life’s Tapestry: Reflections on Relationships and Growth

Image from Pixabay

Image from PixabayThis week, I’ve gained insights from two resonant Instagram posts, shaped by my personal interactions. This write-up does not focus on any singular interaction; rather, it reflects the progression of my own contemplations.

People may continually enter and exit our lives, whether in platonic or romantic contexts. These encounters shape our perceptions, attitudes, and even our identity. Sometimes, these relationships persist, fostering deep emotional connections that enrich our lives. Other times, they fade away, leaving us with memories and lessons. In the tapestry of life, relationships are the threads that weave intricate patterns. We forge bonds, experience joy and heartache, and accumulate a treasure trove of experiences. Each connection leaves an indelible mark, contributing to the masterpiece of who we become. As we journey forward, it is essential to embrace the ebb and flow of relationships, cherishing the moments they bring and the wisdom they bestow.

Image from Pixabay

Image from PixabayI am grateful to @hautehijab for their insightful post which emphasizes the significance of not succumbing to stress regarding marriage, highlighting that the Quran teaches that individuals of inner beauty are destined for one another. It is vital to recognize that what is considered beautiful in one context may not necessarily align with another’s perception, and this principle extends beyond physical attributes.

Equally crucial is the understanding that if a relationship, whether platonic or romantic, fails to flourish, it is part of a Divine design. This resonates with the question @theclaycouple were asked, ‘how do I get over someone’? I liked their reply that the person remains a significant chapter in your narrative, offering lessons and memories to reflect upon. It encourages us to embrace the ebb and flow of relationships, recognizing that each encounter shapes our journey, irrespective of its outcome. Just as beauty must harmonize, so too must our experiences contribute to the beauty of our personal story.

[image error]August 1, 2023

Traveling While Brown: A Pakistani Perspective

Thanks to the newly built section for Scandinavian Airlines at Arlanda airport in Stockholm, the airport experience has become very swift. You are allowed to bring as much liquid as you wish. Hand luggage need not be emptied for electronics and so forth.

Unbelievably, I deplore airports since they unnecessarily exhaust travellers even before the flight. Some of this detestation on my part is not merely because of the impractical structures and procedures, but because of being a woman of colour. Even with light skin, one can tell my desi-ness from miles apart, although I am often mistaken for being a Turk or a Syrian — at the airports though, even this kind of perception by others does not give me any privileges.

For these reasons, as a woman of colour, flying solo comes with a lot of anxiety on my part. Despite my frequent travels, airports consistently elicit insecurities about my physical being. But it is not just about that, it is about my past experiences at the security checks at the airports which have reinforced this anxiety.

This week, the experience was so pleasant that despite the sombre moments, I was struck with surprise when I was not asked to be randomly checked or asked to remove my shoes. Nothing! Zilch! I froze at that moment!

I was shocked! I looked at the security personnel in disbelief. Have I for some reason been able to erase the visible markers of my brownness, I wondered, and looked into the eyes of the two of them in disbelief as I walked out of the security door slowly. It was too good to be true. I walked very slowly while looking at my hand luggage on the left coming out of the new machines installed in this section of the airport. I still walked slowly expecting to be called out of the queue any moment. My son had passed the security door even before me — he was carrying nothing, but still — a young brown man passed the security without randomly being selected!

I stood there for a few seconds asking the security personnel, that is it? And in my head, I uttered, you do not want to further explore my bags or pat down? I thought about the one-litre water bottle, my avocado sandwich, an apple, a few almonds, my cardamom & cloves pouch, and lipstick in my backpack. I was even carrying George Orwell’s, Why I Write? Not even that or my small prayer book in Arabic warranted further investigations? Nothing belonging to this brown woman was extraordinary which was shocking for me at the moment!

As a person who has had to solo fly very frequently, I have memorized security checks so much that I keep certain items packed at home, and some items ready for travelling specifically for budget airlines’ requirements (read no checked-in baggage and limited space). Between 100–200 SEK, this is a great deal but comes with compromises — I repurpose empty medicine bottles for all the liquids I need to carry and save almost empty toothpaste for such occasions. My hand luggage is organized slickly and in astonishing order!

With this success — no patting, no random selection, no further exploration of my bag, no questions asked, I swayed to the gates with my son. My sandwiches are intact. My water bottle is untouched. My ego was boosted so much that I even sipped the lightly brewed free tea provided by SAS! With every bite of my sandwich, I wondered, is this how being white might feel? Is this how our privilege — or the absence of privilege in public spaces feels? Is this how fear or lack of fear is reinforced?

But most of all, is this how we would feel when all the norms, policies, structures, and hierarchies are demolished?

I will wait for that day. I wait for that day with my whole being.

Today, I am grateful for my water bottle, and my sandwich to have experienced a different world.

Safely buckled up with the safety belt in the tiny plane, I moved my gaze from the tiny plane’s propeller visible from the plane’s window on the right side and I looked at the young, brown, Pakistani man with dark hair — my young son — laying his head on my shoulder in a carefree early morning nap. I am sure he would have different experiences if he were blonde or fair or not Muslim, or Pakistani. Even in social behaviours (online and offline) I have experienced how unfairness, bias and bigotry for certain races, and ethnicities is played out. I have experienced it for my children. I have experienced it for myself.

Looking at him, a prayer, a wish came out of my heart in those moments that his brown body is always protected from structural discrimination and racism — even more so, our activism and writing about it brings more awareness and empathy. My last a dream is that may somehow racism disappear from this world!

#TravelingWhilePakistani #Traveling #Racism

[image error]February 3, 2023

Professor Li Wei on trans languaging, inclusion and social justice

Today I had the absolute honor and privilege to host Professor Li Wei, who is the Director and Dean of IOE, UCL, in a webinar at the English section of the Mid-Sweden University.

It was an extremely successful webinar (even if I may say so myself 🙂). Despite the technical glitches, we had an amazing turnout of about 135 participants joining us from all around the globe. Thank you very much to everyone who joined us.

Professor Li Wei needs no introduction as he is a world-leading scholar in the interdisciplinary field of applied linguistics and language education focusing primarily on bilingualism, bilingual education and minority languages.

Among other scholarly feathers to his cap, in 1998, became the first person of Chinese origin to become the full professor of Applied Linguistics in a UK university, which is a huge achievement in itself. In his academic career, he has founded several Journals, written about 160 articles, handbooks, textbooks and been awarded by various prestigious academies.

While unfortunately, we did not record the seminar, here are some key takes from his lecture for those interested (not his exact words but my rough notes 😉 ):

Translanguaging, its origin and term used in Applied Linguistics and other disciplines:

Cen Williams (1994) used transweithiu in the Welsh context in the Welsh revitalization programme for Welsh medium schooling, while Colin Baker (2001) used transliguifying in English later. There are no monolingual Welshs in the community; to begin with, in this bilingual context, Cen Williams taught Welsh in Bangor by using Welsh whereas the pupils responded in English, or mixed English and English. This was against the school policy of using only one language at a time or compartmentalizing them in water tight separate spaces. In bilingual contexts, restricting bilinguals to monolingual ways of speaking is unnatural because human beings do not speak or think in named languages. Naming languages is a political, social construct which has been brought to us through social conditioning. For bilingual/multilinguals, a popular belief is that languages live in different parts of the brain, which is not true. Bilinguals/multilinguals do not think in one language at a time, although this has been taken for granted. Bilinguals/multilinguals draw from the knowledge of all their languages.

For a long time policy and practice has tried to enforce monolingual norms and policy to bilinguals by restricting or keeping the languages separate whereas the bilingual/multilingual brain does not work in monolingual ways.

Even though decades of research on bilingualism/multilingualism has shown the benefits of using the students’ L1s in the classroom, home language/L1’s are still frowned upon in the classroom in many contexts. Home languages/L1s are deemed as something which should be left outside the target language classroom’s walls, and often are deemed as inferior and bringing in negative implications for learning a foreign language, for example, it is assumed that a pupil/ student learning English/ Swedish etc. should leave their home languages outside of the classroom as it will interfere with their learning. Also, the labeling by linguists and practitioners is not without political stance, and has social consequences, for example (from Li Wei’s talk), a child born to Chinese heritage parents (in the UK) might be labeled and put in a class of English as an additional language, who might be assumed as requiring to be exposed to a specific threshold and input in the target language.

Translanguaging (it is not translating one’s utterances in different languages) is a pedagogical practice which draws from all languages of the learners, in which one receives information through the medium of one language and gives information through another language. Translanguaging helps challenge the monolingual ideas of keeping ‘the named languages’ separately, it helps to maximize the learner’s ability to learn when input and output are in different languages. Translanguaging as a pedagogy helps maximize the bilingual/multilingual learner’s potential by centering the learners and teachers as facilitators. The main idea or crux is to change the mindset about languaging and adapting a co-learning mindset where all learning is valued for true linguistic inclusion and social justice.

[image error]January 2, 2023

Radical Love for 2023

Every year, I write and set some goals for my professional and private life. I write some lofty and some pragmatic resolutions too, but what has helped me even more in the last five years or so is to think of one word as a theme for the coming year. This year I have chosen two words: Radical love. It can be roughly translated to ishq عشق in Urdu, and a few other neighboring languages.

The words ‘Radical love’ have been used by many philosophers, theologians, and educationists to mean different things from their point of view. When there is no consensus about what love is, how can there even be any agreement about how to define it, and how to describe it. The definitions about love, and how, what, wheres of love from the East and the West differ as well, although I must add that they are nuanced, and can not longer be divided into strict boundaries and binaries of the East and the West.

In Urdu poetry, and Sufi writings, for instance, God and (radical) love/ ishq can appear synonymous at times. God is love, love is God. The very essence of God is love.

In modern day popular culture, love is mostly projected as romantic love, but in Islamic mystic poetry (es. Urdu) and religious contexts, love is of two types:

ishq-e-haqiiqi (divine love)ishq-e-majazi (mundane, carnal love)

To the mystics, love is not a fleeting feeling in the external material world, but an inward journey of becoming, developing and contemplating. A journey to self is, thus, a journey to God.

Nietzsche’s conception of radical love is amor fati — true self-love, but love is not an emotion which can be turned on and off, even when it is self-love, and especially when it the cultivation of self-love in one’s self. Neither are easy, not easy to put into practice, but intention is the key, I believe.

Professor Omid Safi quoting Rumi reminds us that divine love is light, it is fire, it is pre-existing, pre-eternal alchemy:

Look:

Love mingles with Lovers

See:

Spirit mingling with body

How long will you see life

As “this”

And “that”?

“Good”

And “bad”?

Look at how this

And that

Are mingled

But it is Quran’s words which bring more clarity to me:

This is God’s command: love and justice (16:90)

God loves them, they love God (5:54)

So, for me radical love would be God-centered slow and contemplative journey to self — because self-love is also love for the Beloved and it is radical love done tenderly to our inward selves. Radical self-love makes ethics and justice as its anchor and permeates all dimensions beyond the self!

So doing being ‘radical love’ is my intention, God willing!

Ready to receive and ready to give!

[image error]December 27, 2022

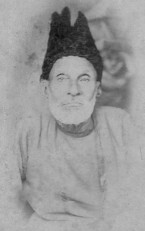

Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib, a preeminent Mughal & British-Indian era poet

Today is Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib’s #225thbirthday.

Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib, a Mughal & British-Indian era poet, was one of the most preeminent poets from the Indian sub-continent who like others at that time, wrote poetry in Persian & Urdu (known with other names at that time, like Hindustani, lang of the Moors etc.)

Ghalib’s grandfather was a Seljuk Turk who had immigrated to the-then India from Uzbekistan; Ghalib’s father married a lady who was ethnically a Kashmiri, and later he himself settled in Delhi & married Umrao Begum who was the daughter of an aristocrat.

Ghalib grew up among Urdu (the-then Hindustani), and Persian; to some extent, he was also acquainted with Turkish and Arabic. Ghalib wrote extensively in Persian — the official court language of Mughal India before the Crown rule and switch to Urdu and English as the languages of education came into practice.

Ghalib was the product of his times — exposure to multiple and diverse languages strengthened his linguistic prowess. Even though, he chose Persian and Urdu as his medium of expression, he is primarily a poet of love, who provides versatility and variety to other topics he touches upon with the help of poignant imagery and allusion in an attempt to convey his point:

کیا فرض ہے کہ سب کو مِلے ایک سا جواب

آؤ نہ ہم بھی سیر کریں کوہِ طور کی

Kya farz hai ke sab ko mile ek sa jawab,

Aao na hum bhi sair karen Koh-e-Toor ki

Why should one assume that we will all get the same reply,

Let’s go, we should also stroll around on the Mount Sinai

Ghalib’s Persian divan (poetical works) is much longer than his Urdu divan, however, his fame rests on his Urdu poetry. His best poems were written in three forms: ghazal (lyrics), masnavi (moralistic parable), and qasidah (panegryric).

He is equally renowned for his prose pieces s d letters.

Ghalib grew up in an aristocratic family during his youth, but his later life was full of struggles due to his frivolous nature, personal circumstances & traumatic nature of his times, which compelled him to make some poignant observations about life:

قید وحیات وبند. غم، اصل میں دونوں ایک ہیں

موت سے پہلے آدمی غم سے نجات پائے کیوں؟

The prison of life and the bondage of grief are the same,

Why should humans get rid of all grief before dying?

Lauded by the highest ranks of Dabir-ul-Mulk, Najm-us-Daula and Mirza Nosha of his times bestowed by the Mughal Emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar. He was also appointed the poet laureate to the last Mughal Emperor. Bahadur Shah Zafar.

During the British Raj, Ghalib struggled to get his full pension, and at one point, it was fully suspended, but finally he was granted a small pension

His financial troubles were compounded by his reckless style of living, especially because of him not forgetting the past of his ancestral nobility. His romantic tendencies could not be curbed as well, even after his marriage — about which he writes in his letters too. While his marriage was shook by his amorous misadventures, the added impact to further his troubles was the death of their seven children one after another.

At the time of the War of Independence (also known as War of Mutiny in the British history books) in 1857, to add to his misfortunes, his only brother Yusuf passed away, but Ghalib did not even have enough money to give him a proper burial.

Ghalib expresses his love for him here:

تم ماہِ شبِ چار. دہم تھے میرے گھر کے

You were the moon of the fourteenth night (full moon), effulgence of my home!

This was not all, he was often in trouble from the debt collectors & the dragged to court, which was all the result of him living beyond his means.

When he was sentenced for three months on the charges of running a gambling den at his home, he was so mortified of the stigma and shame that he thought of leaving Delhi, which he expressed here:

رہیے اب ایسی جگہ چل کر جہاں کوئی نہ ہو،

ہم سخن کوئی نہ ہو، اور ہم زباں کوئ نہ ہو

To live in such a place where no one else is there to give me company,

No one to share my thoughts, and no soul to converse in my tongue

Sources:

Brittanica , T. Editors of Encyclopedia (2022, December 23). Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib. Encyclopedia Britannia. https://www.brittanica.com/biography/...

K. C. Kansa (2005). Mirza Ghalib: Selected Lyrics and Letters. Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

https://rahulnegi.blogspot.com/?m=1

Rekhta.org

Picture source: The only surviving photograph of Mirza Ghalib (circa 1860–1869) from Wikimedia commons in the public domain

[image error]Benazir Bhutto — the first democratically elected Muslim woman Prime Minister

Wikpedia commons: File:Rueda de prensa de Felipe González y la primera ministra de Paquistán. Pool Moncloa. 14 de septiembre de 1994 (cropped 2).jpeg

Wikpedia commons: File:Rueda de prensa de Felipe González y la primera ministra de Paquistán. Pool Moncloa. 14 de septiembre de 1994 (cropped 2).jpegToday I want to reminisce Benazir Bhutto, the former Prime Minister of Pakistan, who, in 1988, became the first democratically elected Prime Minister of a Muslim majority country after eleven years of a harsh military dictatorship in the newly independent former British colony, Pakistan, which was still juggling the throes of its birth and the tremors of two hundred years of British colonisation.

In my opinion, Benazir Bhutto’s name — as a Pakistani woman — to become the first Muslim woman Prime Minister should be mentioned and remembered with all her self- identified identity makers because erasure of any such element from the lived-history is unethical and corrupts the actual documentation about communities and nations. Erasure of people’s idenitity markers are specially important for minorities within minorities, nations of the global south, women, and, so on and so forth. I would, however, like to add a caveat here that women empowerment and breaking of glass ceilings sometimes become empty cliched words, often used in echo chambers. However, considering the comparative newnewss of Pakistan as a country with all its burdens of its colonial past, the brutal partition, corruption of the politicians, dynasty politics, military dictatorship, global war on terror, a woman becoming a Prime Minister in Pakistan after some twenty-six years when the first woman in the world history — Sirimavo Bandaranaike — became the first democratically elected woman Prime Minister in Sri Lanka in 1960.

Pakistan, a male-dominated patriarchial society is a young nation which is developing & prospering on the soils and foundations enriched by its ancient history — and the mash-up and melting-pot of all its traditions and learning from its foreign invaders and the heritage of the indigenous populations. Paradoxically, it is a place where women have historically, culturally, and socially been the powerful matriarchs who actively participated in their communities, in both public and grassroots leadership positions as well as in private lives. With the rise of external and non-indigenous ways of performing faith practices of Islam — the majority religion of Pakistan — at the time of return of Benazir Bhutto in 1986, it was still being debated in private drawing room conversations of Pakistan & Pakistani diasporas, whether a woman can become a Prime Minister or not. Amidst the ISI (Inter-services intelligence of Pakistan) sponsored Afghan jihad and the longest military dictatorship of General Zia-Ul-Huq in Pakistan, the return of Benazir Bhutto from London to Lahore in 1986 as a young, educated, eloquent speaker was an inconic imagery and visual power in the discursive and linguistic landscape of Pakistan. BB as she is foundly called by her supporters did inherit the power and support her party supporters had for her father, Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto.

As a teenager in the eighties, I was also dreaming about my educational goals, and my future, in general. Thatcher, Gandhi and then (Benazir) Bhutto (despite their political stances, and failures) — emerging in the power houses of politics in the eighties was not only a feminist success of that time, but also left an impacting visual in the global cultural memory — but especially for women from the global south, as well as for women with roots from the global south. The news of a proud moment ‘back home’ was greeted with enthusiasm and fervour by my abu ji (father) at our home as he was a supporter of Pakistan People Party (PPP), and especially Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto (ZAB) — despite my mother’s opposition; as opposites attract (or not), this scenario of divided political stance is probably reflective of many households in Pakistan and among diasporas.

Despite the divided political stance in Pakistan, Benazir Bhutto’s coming of power in 1988 as the first elected Prime Minister has probably set the debate of whether a woman can become a Prime Minister or not. Like all first attempts, and first experiences of any sort, it always opens up space -little or big — for the next generations, Benazir, despite all her faults and failures, has also opened up many spaces in Pakistan and among Pakistani diasporic imaginary homelands.

Today, I solemnly commemorate her death. Rest in peace, Benazir!

So, here is to all sorts of firsts!

[image error]December 22, 2022

The country without a postcode and my imaginary homeland

Yesterday, it was a day when pherans are celebrated as #theworldpheranday or #theinternationalpheranday — an effort to reclaim and rekindle the love for the slowly diminishing traditions of Kashmir and last but not the least, to resist through fashion. This is my ode to the fatherland where the art of weaving wool and stories has been a tradition since centuries!

My dilemma though is that I get stuck at the word ‘Kashmir’ — the ever-present conundrum of describing its geo-political location from within and outside. As a diaspora Kashmiri, I do feel, I do not have the right to speak for the Kashmiris living in Kashmir, however, I do feel the desire and the obligation to amplify their voices through the soft images of Kashmiri tea, shawls, and the stories that have been transferred to me by elders in the family. I call it my ‘imaginary homeland’ and I am happy visiting it from time to time even though no one lives in that imaginary homeland anymore — even if the ancestral home might be standing there and taking its last breaths in the actual material world.

Kashmir, popularly known as the jewel of Asia, the Asian Switzerland, the paradise on earth is not devoid of controversies when it comes to what and who are authentic Kashmiris — both from within and outside its communities. Agha Shahid Ali, a renowned American-Kashmiri poet writing in English once shunned using the word ‘Kashmir’ for many many years, and when he wrote the third collection of his poetry, The country without a postcode, he moaned Kashmir in several languages, which at times is a cry of my confused mind and identity dilemma:

Let me cry out in that void, say it as I can. I write on that void:

Kashmir, Kaschmir, Cashmere, Qashmir, Cashmir, Cashmire,

Kashmere, Cachemire, Cushmeer, Cachmiere, Cašmir. Or Cauchemar

in a sea of stories? Or: Kacmir, Kaschemir, Kasmere, Kachmire, Kasmir. Kerseymere?

[image error]December 21, 2022

The cake with a transcript! How do conversation analysts create cakes, erm transcripts?

Many of my friends and colleagues on Facebook and Twitter where I shared the picture of a cake with a Jeffersonian transcription admired the cake which was created by a colleague, Cat Holt, for the competition of Loughborough Conversation Analysis Day, 2022. Many thanks for your interest both in the cake and the transcript that was on the cake. I, as a conversation analyst, as you might have gathered, was thrilled to see the transcript on the cake 🙂 — and, obviously, to taste the cake.

Among the researchers who use conversation analysis to study (human) interactions, detailed transcripts (which we use in conversation analysis) are hard work — a lot of hard work! A transcript is not just a minute-by-minute verbatim detail of an interaction in our case i.e., conversation analysis — transcripts are our blood, sweat and tears literally!

Decades of empirical research and findings from Conversation analysis since the late 1960s and early 1970s when it was developed, have demonstrated how systematic interaction is, and the remarkable orderliness of our conversations. Each specific type of conversation has particular kind of patterns, i.e. there is a beginning and there is an end, and things happen in between, for example, a normative place of a greeting is always at the beginning of an interaction which is paired with a reply in return — which can be missing in some interactions. The distance — pauses which are measured by the conversation analyst — between the two turns-in talk (greetings in this case) inform the analysts what is going on between the interlocutors. Simply put, Conversation analysis provides a model to study talks — a scientific method to study talks.

We start our research project with video recordings, which are forensically transcribed, and then they are analyzed. The data used in CA is preferably in the form of video-recorded conversations, which are gathered with the help of one or more cameras after seeking permission from the participants. Video recordings provide the analyst with authentic information and all researchers (who are not present during the recordings) can observe the data directly without the help of a narrative created by another researcher or the participant under study. In other words, instead of someone (a participant) informing us what they think they were doing, we look at what the participants were actually doing.

Conversation analysts study conversations of all sorts, for example, anything from a dental appointment to court trials, and from family dinners to first dates. Everything we do as humans are done through talks, from complaints to arguments, to questioning, and so on and so forth.

A conversation analyst is trained by working on tons of video-recorded data in data sessions where a close group of researchers bring their video-recorded data and transcripts. In my case, for example, during my PhD studentship days between 2009–2014, I went to our fortnightly data sessions every single month with a few exceptions. The data sessions are where conversation analysts look at a video clip and transcripts prepared by the presenting researcher. Usually, the video clips are no more than one to two minutes long — and the data sessions are usually about two-hour-long work-in-progress seminars where video recorded data is repeatedly watched and analysis is done collaboratively by each researcher commenting on the various aspects, which, in turn, is drawn from the theoretical and methodological readings of the subject.

The transcripts are created by spending hours and hours listening to intonation, speech markers, breath, laughter etc. Everything is marked in the transcript, nothing is left behind including gestures and bodily movements.

Transcripts are like a cake with the icing — for the conversation analysts, more details are always better; video-recorded data are like raw ingredients for the cake! I hope you got some this insight into how conversation analysis is done, and it is not a piece of cake to create such transcripts!

[image error]December 16, 2022

Family language policies among transnational families

Family language policy is the explicit and overt planning in relation to language use within the home among family members (King et al., 2008) — and it starts with when a couple elopes and decide to have a family together.

Family language policy is the explicit and overt planning in relation to language use within the home among family members (King et al., 2008) — and it starts with when a couple elopes and decide to have a family together.My acquaintance’s fiancé is an Urdu speaker but they themselves are ethnically from an Arabic speaking country. I felt some extra bonding with her on this mention of Urdu — kind of liberating when you know that you won’t have to explain yourself more to the interlocutor. Some sort of mental cautiousness engulfed me as well when I pondered how much of the community secrets the other person might know.

They mentioned chicken tikka, butter chicken, biryani and some spices. I felt their internationalness — and I felt connection to them even more.

We took a stroll and then sat down in a glorious summer garden of Stockholm. Our conversation shifted to the topic of languages. We will not be teaching Urdu to our children we have discussed, they said. I missed a beat. We will teach Swedish and English, of course, and my first language, but what good and of use is Urdu? I go quiet, not questioning their decision because it is none of my business. My acquaintance’s future family language policy of not using Urdu among their future children is not a neutral decision. Many mixed race families choose this and that language, and report sometimes accurately what they use and sometimes assume that they only use one language, i.e., the majority language.

At this point, I am reminded of the work in the field of family language policy and how little we know about diverse family language policies. I don’t ask for details, and about her fiancé’s opinion about it. I don’t want to know that either. I am okay with as much as they share or not. But I get stuck in my mind at the argument — the utilitarian discourse and hierarchical construction about languages.

Families choose languages they deem important, and according to their needs and political ideologies. While from the perspective of the science of languages, all languages are equal, it is human nature to put languages in some sort of hierarchies. The underlying factors of such linguistic hierarchies is always racism — or some sort of ‘othering’ for the other language group.

A bi-/ multilingual family often focuses on the majority language at home as well because of the pressure to assimilate. In other families, that might not be the case, and they might choose to use the heritage language. Often times, bi-/ multilingual families will naturally be mixing languages. However, the general assumption is that mixing languages corrupts language use. Purity of languages is not possible all the time and especially by keeping them in strict water-tight container like spaces. Majority of the world is multilingual rather than monolingual, but due to power, prestige and purist ideologies of keeping languages in water-tight compartments, language mixing is often frowned upon. Languages are dynamic, and fluid living entities. Only dead languages do not evolve or — borrow and mix words from other languages.

In folk linguistics, there is always a concern of losing the competence in a majority language. Take, for example, migrants from Asian and African countries in Scandinavia. Their L1s (first languages) might be of not much use in school or majority work places except within their own language communities in Scandinavia or in their country of origin. But that language might be the language one uses with grandparents. Humans have the possibility to maintain more than one language — but only when they deem that language vital for them. I have seen this in my immediate family; my father migrated three times, and so did I. We have lost some languages, some dialects, and kept and maintained some along the journey of life. Our inherited languages are part of what makes us who we are, whether they are directly connected with our ethnic identity or not. At the same time, I know that maintaining heritage language away from its natural environment is not easy — and often at the third generation, the language is often used either in limited capacity or not used at all. Why go far? I see that in my own children. Will it fade away later or would they have the desire to learn more about our heritage languages besides and beyond music, faith practices, food, and other cultural practices? What if they lose it, and what if they don’t? Would I as a grandmother be able to tell my childhood stories to my grand children if I get to see them, or would I need to switch to another medium, another language, another bolee?

[image error]Languaging, literature, culture and landscape

- Alia Amir's profile

- 41 followers