Adam Roberts's Blog, page 5

April 11, 2019

Small in Japan

It seems my story “Between Nine and Eleven”, or more precisely its Japanese translation, has been shortlisted for a 2019 Seiun Award. Which is いいね.

Finnegans Wake in Latin

I translated Finnegans Wake (yes, the whole thing: it wouldn't do into skimp on a project like this) into Latin. If you're interested you can buy a copy of the ebook for £1.54; and I blogged a little bit about the hows, whys and wheretofores over on my Morphosis blog. So there you have it.

February 21, 2019

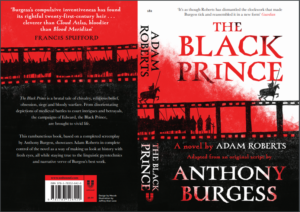

Blackest Prince

The mass-market paperback cover for The Black Prince had been more-or-less finalised [click to embiggen], when Margaret Drabble (!!!) up and reviewed the novel, in amongst a number of other Burgess titles, for the 21st Feb 2019 edition of the TLS. So now it looks like the mmp cover will be redesigned to incorporate a quotation from her. And, well: wow. This was her take on the book:

The overall mood of [Puma] is vigorous and life-enhancing, a celebration of literature, art, music, good food and good wine. These things will perish, and the food on America 1 will be unpalatably dull, but it is good that they have been. Not so the mood of Adam Roberts’s novel The Black Prince, which is as dark and bloody as its protagonist, and some of it unreadably though not, alas, implausibly violent. It is a chronicle of a period in the Hundred Years War, suggested by an original script by Burgess, and it spares us nothing of the horrors of warfare. Roberts employs techniques from film, newsreel and press headlines (“God on our side, claims Fighting Cleric: WALDEMAR IV, KING OF DENMARK, DIES IN HIS 55th YEAR”), and uses typographical experimentation to make his points, somewhat in the manner of Dos Passos. The rich narrative exhibits impressive historical research into medieval battles and sieges (credited to Dr Catherine Nall), and gives us horrifying accounts of Cressy and Poitiers, and of the extreme pointlessness and unheroic brutality of the entire campaign. I had to skip the sack of Limoges. I often have to shut my eyes in the cinema; this was all too cinematic for me. Like Burgess, Roberts does not shy away from the scatological. The bodily sufferings and double incontinence of Ned the Black Prince and others are described in horrific and pitiable detail. Like Burgess, he also enjoys verbal and visual puns. The darkness has flashes of light, such as the bowmen’s response to news of the fighting Genoese: “They had heard of Italy. The land of Pompey. And of Julius, the king aptly named Seizer for his skill at conquest”.

It is a large and at times confusing canvas, a colourful medieval tapestry combined with the grimness of twentieth-century newsreel. We meet figures of nobility and chivalry, with much questioning of the notions of chivalry; we meet foot soldiers and priests and John of Gaunt and John Wyclif. We meet the Black Prince’s bride, the beautiful Joan of Kent, and Alice of Henley with her psychic camera eye. It is a relief when, all too rarely, the camera pulls away from the close-up shots and pans out to the landscape of France and the wheatfields and the trees. But overall, we are left, probably intentionally, with a sense of the utter wastefulness of these hundred-plus years, when England was attempting to cling onto and extend its claim to French territories. We do not emerge with credit, although we list these battles as victories.

As you can see, she goes on to connect the book to the present Brexit national and cultural travails. Margaret Drabble, no less!

December 19, 2018

My 2018

I published a few things in 2018, and here they are. First off: The Black Prince (Unbound). The author is never best placed accurately to judge his/her own work's merit of course. That goes without saying. But this still seems to me one of the two or three best things I've written. That doesn't mean it's good in any larger context of course. Still: I'm more pleased than I can say that my name appears on the same title-page as Anthony Burgess, and I'll be honest: that's probably enough for me.

By The Pricking of Her Thumb (Gollancz) is a kind-of sequel to The Real-Town Murders, and is another near-future SFnal impossible murder whodunit. If you're curious who dunit you could read the book. I mean, I can tell you: it was money, but it's always money, in these things, isn't it?

Haven (Solaris) is a sequel to Dave Hutchinson's excellent Shelter (Solaris). Dave is writing book 3 right now, after which d.v. I will write book 4.

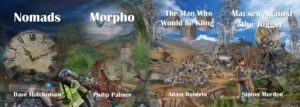

I put out a couple of novellas this year: one, The Man Who Would Be Kling (NewCon), was part of a foursome of 'alien among us' stories that Ian Whates's press issued. Mine is a kind of Kipling/Star Trek mash-up, as the title suggests. The four books' artwork aggregates, rather neatly, into one long canvas, like Chris Foss's covers for the old Pan Foundation novels. You may need to click-to-embiggen to see them properly.

Also with NewCon is my standalone novella The Lake Boy. This started life as a section of The Thing Itself that outgrew its slot. It's my version of that venerable sf tradition, a Wold Newton Meteorite tale.

I also did some academic work. For example, Cambridge University Press published this:

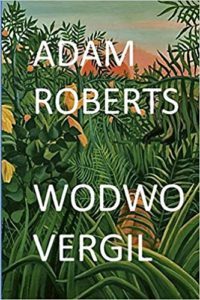

And last, but not, in my judgement, least is this new translation of Vergil's Eclogues into the idiom of Ted Hughes, plus an accompanying essay on pastoral.

These books appeared on no Best of 2018 roundups and none of them have been, or will be, shortlisted for awards or other signs of community esteem. But I've come to terms with that, esteemless as I have been for the last many years. Turns out it's OK, actually.

I won't publish so much in 2019.

October 20, 2018

The Financial Times reviews “The Black Prince”

October 1, 2018

One, two, “Princes” here before you/That’s what I said

August 15, 2018

SFX reviews “Thumb”

August 1, 2018

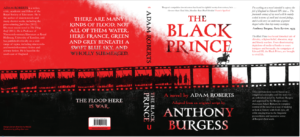

Final cover layout for “The Black Prince”

I'm absolutely delighted with this, which is a thing of beauty and a joy forever: gorgeous Jeffrey Alan Love art, generous blurb from Francis Spufford, Big Wilson and Little Ad. Click to embiggen!

June 8, 2018

Minigraph

I was asked to contribute a 'minigraph' (which is what the cool kids of academic publishing call a 20-30k-word monograph) to CUP's new Cambridge Elements Series: “A new series of research-focused collections of minigraphs on aspects of Publishing and Book Culture.” So I did.

You can find more about the Elements series here:

This new series aims to fill the demand for easily accessible, quality texts available for teaching and research in the diverse and dynamic fields of Publishing and Book Culture. Rigorously researched and peer-reviewed minigraphs will be published under themes, or 'Gatherings'.

I'm not sure when my vol is due out (later this year, I think) but Cambridge have now sent me the cover art, above. Brown and understated, which I quite like. Publishing and the Science Fiction Canon looks at the step-changes in the technologies of book and magazine publishing and distribution, and the connected explosion in literacy rates, that occurred at the end of the 19th and start of the 20th-century (I focus mostly on the UK and France) in order to make a particular argument about the science fiction of the period. Something remarkable happens to SF around the time of the Verne-Wells 'scientific romance' boom, I think. For centuries science fiction had been an interesting but small-scale aspect of a larger cultural context; but from roughly the 1870s-80s through to the 1930s it expanded hugely in terms of cultural production and popular appeal, growth that set the genre on its path to becoming what it is today, a massive and global popular culture. Exactly what did happen back then is a large question, and I try to unpack one aspect of it by reading key works in the context of the techologies of their material production and distribution. At any rate, it's one of the things I've been doing during my research leave.

June 5, 2018

FRSL

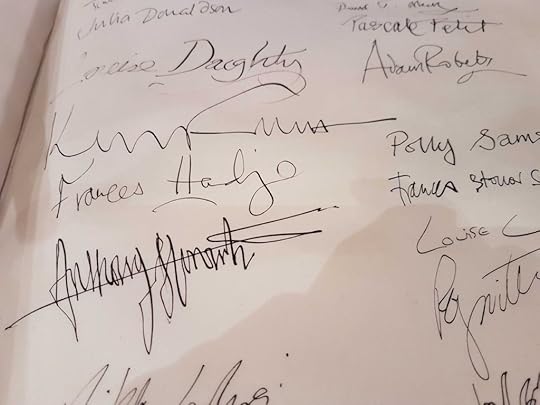

Yesterday evening I was one of the latest batch of Fellows elected to the Royal Society of Literature. We all gathered in a venue in Bloomsbury, with existing Fellows and friends and family, for the induction process. The Society's President, Marina Warner, made a speech, and one by one we went on stage and signed the RSL's big book—the same one that they've used since the Society's creation, by George IV, in 1820. To sign our name we were offered the choice of: Byron's quill, George Eliot's quill, or T S Eliot's fountain pen. I chose the last of these. Above you can see my signature, top right; middle-left is that of my friend (and amazing writer) Frances Hardinge, just above Anthony Horowitz. So: my name, in the book itself! Blimey.

Amongst the other inductees were two friends and colleagues from the RHUL Creative Writing department, Nikita Lalwani and Ben Markovits. Royal Holloway Creative Writing is a subset of the English Department and not a large outfit as these things go nationally; but since our colleague Jo Shapcott is already a Fellow our small department is now home to four FRSLs. That's unmatched and, I think, unprecedented anywhere in the country.

Being made a Fellow gives me the right to add the letters FRSL after my name, and to take part as much or as little as I wish in the Society's various outreach and literary activities (I think I'll aim for the more rather than the less, so far as I'm able). It is, I hardly need to say, an immense and indeed rather staggering honour, wholly unexpected on my part, and just as wholly delightful and wonderful. As I sat and looked at the calibre of the writers around me being inducted, and reminded myself I was joining a select group that included my beloved Samuel Taylor Coleridge, not to mention Tolkien, Yeats, Kipling, Hardy, Shaw and Chinua Achebe (and amongst the living: Margaret Atwood, David Hare, Kazuo Ishiguro, Hilary Mantel, Paul Muldoon, Zadie Smith, Nadeem Aslam, Sarah Waters and J. K. Rowling) I found it, simply, hard to believe. And yet here we are. Honoured and humbled doesn't begin to cover it.

Adam Roberts's Blog

- Adam Roberts's profile

- 558 followers