Tanner Campbell's Blog, page 28

October 20, 2022

In Defense of Podcast Ads

Before I became a "full-time" philosophy podcaster, I was a full-time audio engineer, podcast consultant, and pundit in the podcasting space. I've recently seen an uptick in concern over the ads in the Practical Stoicism podcast, I wanted to spend a little bit of time explaining the reality of podcasting full-time and hopefully, assauge some of those concerns. Once more, because I want you to keep it in mind, my only formal job, the source of 90%+ of my income, is this podcast. This is not an after-work extracurricular for me, this is how I pay my bills. I hope this post will bring those who have offered criticism of my introduction of ads into the podcast around to a more empathic position on the matter.

Podcasting for a living is like starting a small businessI used to own a recording and post-production studio in South Portland, Maine and had you told me then that podcasting was like owning a business, I would have told you to go take a long walk off a short pier. But it's almost exactly the same. Just like my studio business I need clients (listeners), products/services (ad-free feed, books, etc), and investors (advertisers). Without listeners I can't sell books or ads, but without books or ads I cannot make money. Deciding to become a full-time philosophy podcaster and writer is, without a doubt, the riskiest small business undertaking I have ever set out upon. It's also, perhaps, the craziest. Let me explain why.

Podcasts have always been free.Since the inception of podcasts as a form of entertainment media, podcasts have been free. It is extremely difficult to transform a thing expected to be free by 99.9% of the population into something that costs money. If podcasts all cost money tomorrow, podcasting would die. That presents a unique problem to anyone who wants to make a living in podcasting, namely: they must monetize the audience indirectly. But why, you might ask, don't they just charge the audience money? If they're a good podcast, they should get a high number of supporters, right?

The value of Patreon and "premium feeds."A common refrain from listeners of podcasts, especially when a podcast gripes about not making any money is, "well if you were good, people would pay you." But that's not true. My podcast receives 500K(1) downloads per month and I have around 75K listeners. I don't use Patreon, but I do use Supercast. Do you know how many subscribers I have on Supercast, each of whom pay me $6/mo to support the podcast and get rid of ads? 49.

Out of 75,000 listeners, who very evidently enjoy my show (because they show up every week, twice a week, to listen to it) just 49 people pay me $6/mo to support it. That's 0.065%(2) of my audience. It also equates to just $300/mo.

You may think, "Well, guess you better get more listeners!"

But did you know that Practical Stoicism is in the top .01% of all podcasts globally?

That means the problem isn't the size of my audience, the problem is that the conversion of free "regular listener" to premium "paying listener" is too low to make a living on. That's not a judgement, it's a fact. Part of this small business is the fact that most listeners will never pay you, no matter how much they enjoy your show. That value proposition just isn't there.

So then, as with any other free product (like a game on your phone, for example) ads have to be introduced to make the endeavor profitable. But, as you'll see in a moment, that's not too terribly effective either.

The value of a "host-read" ad.For every 1,000 listens a podcast episode gets, a podcaster earns between $18-$25 for a traditional host-read ad (the average is $23). A host-read ad is what it sounds like, it's an ad that I, as the host, read. My podcast currently gets about 500K downloads per month. That means a host-read ad has the potential to earn me about $11,000 a month. That's a lot of money, right? But here's the catch: that host-read ad doesn't play for everyone. It may only play for 50K of those 500K listens because the advertiser can only afford a budget to reach 50K listens, it also won't play for every listener because the targeting for the ad might be so specific that it excludes a large chunk of my audience demographically. So it's much more likely that a host-read ad earns me $1,150 a month than it does $11,000. I'm not making $11,000 a month, I promise (I'll share what I am making at the end of this post).

The value of "programmatic ads" ads.Programmatic ads are the ones no one likes. These are 30-60 second ads not read by the host (not read by me) and which are for all sorts of things like Amazon or IBM or insurance companies or whatever. I don't have control over these ads beyond the ability to ban certain categories (like drugs & alcohol or adult content). These ads are worth far, FAR less than a host-read ad. In my experience they're worth about $8 for every 1000 listens. So, again, with 500k that has the potential to gross me about $4000 a month. In reality, however, programmatic ads have the same considerations that host-reads do: they don't play all the time, they aren't available all the time, and their progenitors have budgets.

The ads takeaway (and my actual current earnings)Since ad slots will never be filled at 100%, and since they will never be delivered to 100% of an audience, the only way to make them truly valuable is to have more of them.

I currently release two episodes a week. On Saturday I have two programmatic pre-rolls (they play before the episode) and two programmatic post-rolls (they play after the episode). I have no mid-rolls on Saturdays because the meditations are too short to interrupt with an ad. I promised my listeners at the outset that I would never place an ad in the middle of a Saturday episode. Programmatic pre-rolls are worth $5 per 1000 listens. Programmatic post-rolls are worth about $2 per 1000 listens.

On Wednesday I release a longer form episode, about 45-minutes or so. These episodes have two programmatic pre-rolls, five mid-rolls (spaced out over two breaks, partially programmatic and partially host-read), and two programmatic post-rolls.

So, across both episodes in a week I have 13 ad slots. Remember, not all 13 will be filled, and those that are filed won't be delivered to everyone.

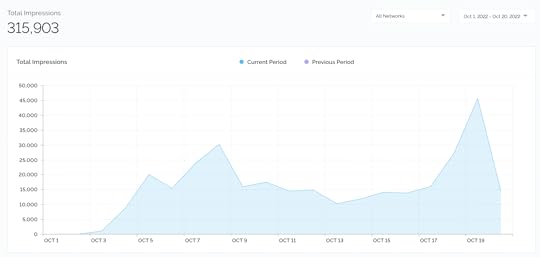

If we average the per 1000 value of all these ads we get an ad value of around $12. So, how much am I making in October? It's the 20th of October today so I'll double my current number of ad listens (that'll be a little more that what will be real, but that's okay), making my ad listens (across all 13 slots) in October ~600K. If every listener heard every ad that number would be ~6.5M (just to drive home the point that not all slots are filled).

$12 x 600 = $7200.

I get 75% of that. That's $5400.

That's gross income, I still have to pay taxes. I live in Colorado.

After state and federal tax I'm taking home (if we extrapolate the figure to an annual earning) $57K/yr or $4750/mo.

This is excluding self-employment tax, and the overhead of producing the show, which will probably lower this to about $4000/mo.

The purpose of this article is not to complain, its to illustrate my situationI'm very happy to earn $4000/mo through my podcasting, even if it's never more than that. That's a healthy income and I can afford to live the modest life I've designed for myself. I have two handsome dogs, a wonderful partner, a living room full of books, and the gorgeous weather of Colorado. Anything else is just extra stuff I don't need. And, truth be told, I'm currently looking into setting up a scholarship fund for kids who can't afford additional schooling after high school, so if I ever do make a bunch of money from podcasting and writing I will be using it in the most stoic way I can imagine using it, helping my fellow human beings live good lives.

But, as it stands, for a podcaster like me, who has no other form of income than that income which is in direct alignment with my podcast (I don't have a "day job"), ads are the only thing that allow me to do this work full-time.

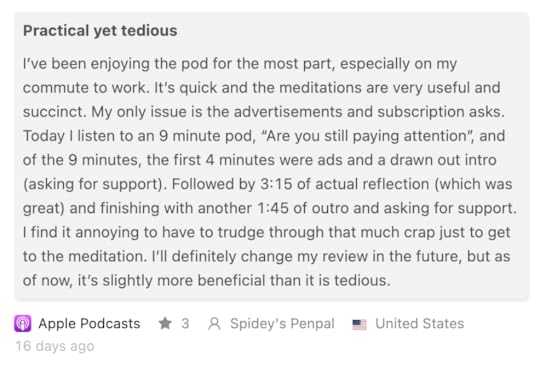

So, when I get reviews like this:

I absolutely feel them in my gut. I get it. I'm not mad at this person, I don't like ads any more than they do. I mean, who wants to break from a great discussion about Stoicism to hear an ad for XYZ company? I know I don't, I know you don't, but the reality is what it is: if I want to podcast full-time I need ads and I need more of them than I prefer (because I prefer zero). So when a listener who loves my content reaches out to me and says something like this:

I am all to quick to provide the link to the premium version of the podcast because I don't want them to have to hear ads, I'd rather trade them $6/mo for no ads both because that's a better experience for them and because if 1000 people hear an ad it's worth, at the most, $23 once, but if 1000 people subscribe to the premium feed, that's worth $6000/mo. Which do you think I'd prefer? But the reality is that most people cannot afford or do not want to budget for media that is already free. Why buy something when it's free?

My final thoughts on the topic (which I will never broach again)...I care more about philosophy than I care about anything else. By listening to this show and dealing with ads, or by supporting it as a premium subscriber, you are the only thing allowing me to do this full-time. My ability to do what I love most in life is inextricably linked to your willingness to tolerate ads or become a premium subscriber. If you keep listening, I'll keep working my ass off to make a good show, but it's a two way street. If you're not there for me, I cannot be there for you. That's the reality of this small business of mine.

Thanks for reading.

----------

(1) My podcast isn't serialized, but it's listened to like it is. While I get 500K listens a month, much of that comes from my back catalogue as the show builds on itself (since it's a reading and exploration of the Meditations of Marcus Aurelius). Anyone who listens to my show as a new listener is going to go back and listen to every single item in the back catalogue necessarily. If this were not the case, I'd get far fewer listens. This is important to keep in mind because a podcast with weekly episodes that had 500K monthly listens would more than likely have 3x the number of listeners I do.

(2) My audience is largely between 18 and 30. Part of the reason for this low conversion rate is that young people don't have as much disposable income as older individuals further along in their careers and lives. A more common conversion rate is around 1%. A high conversion rate is 3%. But this will vary depending on who you're speaking to. If your audience is older and more affluent, you will likely see better performance here.

October 19, 2022

5 Takeaways From My Discussion With James Romm

In October 2022 I had a discussion with James Romm, Professor of Classics at Bard College, about death, dying, and Seneca. The discussion can be heard here, and my primary takeaways are below.

5 Takeaways from James Romm1. Seneca was a complicated individual.

With what texts we have, there appear to be two versions of Seneca.

The first is one that reflects how most non-academic people would think of him: an upright Roman philosopher, focused on ethics and morality, who never compromised his philosophic principles and died on his own terms.

The second is less gracious, and is one mostly only well-read individuals or academics would be aware of. This understanding paints Seneca as a machiavellian character, a man who was, yes, a Senator and a philosopher concerned with morality and ethics, but only on the surface and only as it fit his needs. This Seneca was a manipulator, a conspirator, and hungry for power. In the end, he struggled to die as he preached because he was not really who he said he was.

Most of us want to believe that the former is the true and unassailable truth of who Seneca was, but there are writers from antiquity who seem intent on not allowing us to. That said, those writers had agendas, and we can't know if they're telling the truth, a half truth, or a complete fabrication of the truth.

What is most safe to believe seems to be a balance of the two versions of Seneca. This composite version paints Seneca as a man who cared about becoming a good and upright man, who idolized Socrates, and who tried his best to be everything he said he was. However, this version of Seneca does have an interest power, he thinks, perhaps, that his influence could create a better Rome, and he likely manipulated more than a few conversations to wind up in the positions of influence he wound up in. He probably lied, he probably mislead, and he probably did have at least something to do with the plot against Emperor Nero's life -- but does this make him a bad person?

I don't think so. If he did help to plot the assassination of a tyrant like Nero, I can't see how that would be a bad thing.

I walked away from my conversation with James thinking of Seneca as a flawed man with a mind and a heart to do good; and a man who was about 90% of what he really wanted to be--and that's better than most of us ever do.

2. We shouldn't monstrify death and the human corpse. During our conversation James spoke about his wife's desire to get into bed with the dead body of her mother in the moments after she passed. I, like most people would, recoiled at such an idea. Getting into a bed with a dead body? How strange!

But after thinking about it for a few seconds, it's not strange at all. If our beloved pet died, let's imagine it's our dog or cat, would we not pick it up and hold it close? And mourn the loss of it? I know that I would.

James talked about how we monstrify the human body at its final rest, that is to say, as a corpse. It's a zombie, an undead thing, or a thing we're afraid to become ourselves, so it is difficult to imagine embracing it. But, in the end, if we do not learn to be comfortable with death, then we cannot ever overcome our fear of it, or leverage it as motivation for being more efficacious in our living lives.

3. We can become useful after we die. Some years ago I came across Bios Urn. The idea is that when you die your body is cremated and mixed into a mixture of soil, seed, and nutrients. That mixture, contained in a biodegradable urn, is then planted and you, over time, become the material that nurtures and grows a great tree.

If we look at death as a rite of passage, as a state within which we can still be useful and beneficial to the world, that can help reduce some of the anxieties we have around death.

4. A skull on your desk is a good reminder. After the episode I ordered this skull on Amazon to set on my desk while I work. The idea being that a constant reminder of our mortality achieves two things, the first is a sort of acceptance and thus a decrease in fear of death and the second is a means by which to motivate our current focuses (if we're going to die, we had better get to work!).

5. You cannot be truly brave if you are afraid of death. James talked about how our modern political leaders lack any true bravery, and while that might have more to do with a loss of money or power than it does a fear of death, he suggested that if we are afraid of death, then when it comes time for us to be truly brave--especially in a situation where physical harm is at play--we won't be up to the task.

Of course being brave doesn't mean not being scared, you have to be scared (or at least aware you should be) in order to be brave otherwise you're just performing a mundane action, but your bravery will fail you and you will become a coward in the moment if you are afraid to die.

If the dictator of a country threatens to kill you if you tell the truth, you will not tell the truth if you are afraid of death. If you are not afraid of death, then you will act bravely and that dictator will lose their power over you.

Being comfortable with the inevitability of your own death is, in short, a sort of invulnerability.

What did you learn from James Romm?I've received a number of emails since the James Romm episode released, each sharing ideas and responses to the discussion. I'm sure you have thoughts as well. If you do, I invite you to drop them into the contact form here.

How do you feel about your own death? About the things we spoke about? About death in general? Is it possible to be truly unafraid of death? Let me know your thoughts on these questions and anything else that may have come to you while listening.

October 7, 2022

Be Like The Mighty Honeybee

For a while I've been kicking around a thought that goes something like this: "To be a good Stoic, to be a good person, one must effort to be like a honeybee." I wanted to take a few minutes to flesh that idea out a bit.

Why is a honeybee so good?A honeybee wakes in the morning and does its honeybee duty. It leaves the hive, pollinates the world, returns with pollen all over its body which it then hands over to whatever process it is in a hive that makes honey (so they can survive the winter). The honeybee does everything it does in order that it might serve the world (through pollination) and take care of its community (by helping its hive to survive). The honeybee is the perfect being; selfless, un-dauntingly committed, and always ready to do what is good and useful.

But the honeybee has an unfair advantage...

The honeybee has absolutely no choice in its behavior, because it lacks the necessary mental faculties to make choices. The honeybee is almost like a robot in this way; it is so good because it can be no other way.

Human beings are not so lucky... or are they?Born with the ability to contemplate the future, to ruminate on the past, and to decide their behavior, human beings are, in a way, cursed. When we wake, we wake with no programmed purpose, no robotic drive to help or serve--we simply wake, remain awake for a few hours, and then sleep until next we wake. Everything in-between is a choice, a litany of choices we are free to make no matter their utility or goodness.

But our curse comes with the magic incantation necessary to lift it.

We have the curse of choice, but with that choice we can choose to be like the honeybee.

In Stoicism we learn that Nature is as divine as divinity can get.We further learn, as a consequence of this, that human beings, with their ability to choose, are, in a way, apart from the rest of the natural world. However, if we can recognize this, and prioritize the work necessary to choose to become more in-alignment with Nature, we can become more like that which is divine. This requires, of course, the belief that to be more like Nature is, if not divine, then, at least, a very good thing. This belief, whether religious or logical, must be held by any Stoic, for the rest of Stoicism is based on it.

If we believe that Nature is divine, or, alternatively, if you're not open to that word, logical and worth mimicking, then we can formulate an ideal of what it means to be a human being doing its human being duty. What does that ideal and duty look like?

We wake in the morning and we leave the hive. Once outside, we play a part in the world that benefits the world. While engaged in the work/effort of benefitting the world, we collect that which would benefit our hive (which refers to both our communities and our homes). And, above all, we invest no small amount of effort in ensuring our minds and bodies stay fit for this work.

If you wish to be a stoic, then do what I do and take a few pages from the playbook of the mighty honeybee.

September 28, 2022

Nihilism and the Need for Good Philosophy

Because philosophy is, as most every philosopher has ever described it, including Aristotle, the search for the good life, I don't consider Nihilism to be a philosophy. Rather, I consider Nihilism to be philosophy's antithesis -- I view it as practically cancerous; as did Nietzsche. I know my last post discussed it, but in this post I'd like to really drive home the point of why it's so problematic.

Nihilism is the belief that life is meaningless and that nothing matters as a resultI want you to think about what this means. It means friendship doesn't matter, it means holiday dinners don't matter, it means trying doesn't matter, and it means you don't matter.

Of course if we make a requirement of anything mattering that it must be eternal then, yes, nothing matters because nothing is, ultimately, eternal.

But is that what we're saying? And if it is, should we be saying it?

True, you will die. True, one day, humanity will go extinct (no matter how long it takes). True, someday, our sun will go red giant and engulf the Earth, turning it into a charred ball of rock and then, presumably, some sort of liquid magma. But what has that got to do with whether or not something we do today matters?

Why do we require the absence of death, or expiration, in order to say something matters?

Regardless of why, we do. That's what gives Nihilism its allure.We can easily excuse any behavior, any lack of effort, any lack of involvement in our own lives and in our communities with a flippant, "Well, it doesn't matter anyway."

And so many people, young people especially, who are already disenchanted by the fact that they are likely the first generation in history (certainly modern history) for whom life is not less difficult than their parents' (in very many cases), seem particularly vulnerable to this truism offered to us by the Nihilists.

If I were a 21-year-old college graduate today, I'd be looking at what was available to my parents at my age and wondering why it wasn't available to me. Like reasonably costed home ownership.

There are a smattering of other less-better things that I don't have the patience to dive into, suffice it say there are compelling reasons to throw one's arms up in the air and say, "Well f*ck this. I'd rather just live in the moment and have the most fun I can have because.... none of this matters anyway."

And, you know what? It's hard to fault them for it. It's hard to fault them for it because they don't really learn much about the value of philosophy in school do they? They learn about the value of employment, and career, and how to keep the lights on and the fridge full -- and the ones who don't go to college tend learn those things even better. When you're poor, and no one has taught you anything other than the idea that your value is derived from your earning potential, or your labor, it's really easy to see how a young kid with no prospects, or a very long difficult road of failure and struggle ahead of them, would check out of the system entirely.

Nihilism is a convenient justification not to look at the open road ahead of them and see that struggle and difficulty and say, "Damn! What a great quest I have just set out upon! What will I learn in these trials? How will I grow? Let's get to work and find out what my life will be!"

Philosophy is a tool of examination and betterment, it's not meant to be a conclusion.Philosophy is the only tool we have to answer the questions: how can I live a good life? How can I become a good man or good woman? How can I make the world better?

We need young people, and also not-young people, to see philosophy as the thing capable of allowing them to discover their purpose and meaning.

Religion used to be the answer to this, but when we killed god we needed to create another answer.

Now we're here -- human beings who need life to last forever in order to feel like life is worth living at all -- living in a world that has realized death is a real thing and everything is temporary when given enough time. That's a hell of a situation to find oneself in!

What then do we cling to?

Work is one option, certainly. Chasing the almighty dollar, chasing fame or status, those things are fairly good stand-ins... for a time.

When you get into your 50s (for most people) however, and you start to ask questions of yourself about legacy and wasted time, money and status seem to lose their power. At this point most people have their mid-life crisis and start searching in earnest for their meaning. Sometimes they turn back to religion, sometimes to new-age spirituality, sometimes to vice or a consuming hobby, or sometimes they find nothing and become dusty old curmudgeons that die dissatisfied and feeling cheated.

But with the gap between the almighty dollar and young people just starting out increasing by the day, midlife crisis aren't event given a chance to arrive because the institutions we've shifted the foundations of our meaning and purpose to are now being dashed to bits and scapegoated as the reasons life is so unfair and difficult for most everyone.

That's a bleak place to be when you're 16-years-old, right?

Makes Nihilism pretty damn sensible, doesn't it?

It's easier to believe that none of this matters than it is to look up the shear side of a towering mountain and decide to invest your life into figuring out how to climb it regardless of how impossible it seems.

This was always the power of philosophy: it taught us to see life as a challenge that needed to be overcome, a raging sea that needed to be navigated, a challenging puzzle that must needs be solved -- Nihilism suggests, instead, we shouldn't bother starting the race, we should drown in that sea, and we should leave that puzzle right where it is.

What utility is there in that?

Other than leaving us in a state of utter hopelessness, what does Nihilism give to us?

Or is that its only purpose? To dump a bleak truism on us and then wish us luck figuring out what to do about it?

Yes it's a fiction, but Stoicism gives you a foundation on which to build a purposeful and meaningful life!You're going to die, get over it. But do you want to be a useless, miserable, unhappy, and lonely drain on your family, friends, and society as you march towards that death? Or would you rather have friends, solve problems, make people happy during their lives, improve the world for the next generation, and look at yourself in the mirror every night at the end of the day and say,

"I did something that mattered to someone today. I want to do the same thing tomorrow. I want to effort, I want to toil, I want to make the most out of this meaningless life by giving meaning to it!"

Because that's the secret to a happy life: adopting a fiction that means something to you, and that you can invest your life into embodying.

Philosophy can help you find your fiction. So, go get after it.

September 26, 2022

Stoicism Is Not Nihilism

To call someone stoic, in modern times, is more a pejorative than a compliment. When we say it, we usually mean to imply that the person is without feeling or emotion. Stoicism doesn't teach us not to have emotion, quite the opposite in fact. Stoicism teaches us, among other things, that a mind ruled by emotion leads to a chaotic life. A chaotic life, in turn, results in an individual being less useful to their community, less contented in themselves, less resilient to the ups and downs of life, and less able to find peace.

So pernicious is the belief that feelings and emotions are antithetical to the precepts of Stoicism, that one of the problems people have with the philosophy is their entirely affected perception that Stoicism is a form of Nihilism. "We can't control anything, so nothing really matters."

As a Stoic, this fundamental and widespread misunderstanding is frustrating beyond measure. To me it is like thinking banana pudding is bad because it tastes too much of spinach. If you don't like banana pudding, there's nothing wrong with that, but at least base your like or dislike on the actual merits of banana pudding, don't ascribe your aversion to it to qualities that it objectively does not possess.

Nihilism is problematic because of how true it is and how unequipped it leaves its victimsNihilism, Existentialism, and Absurdism are, perhaps, the worst philosophies to ever be dreamed up. Not because they are wrong, but because they are far too accurate and then go on to provide no solutions for the problems they present.

It is objectively true, as far as any mortal knows, that we die and there is no after life. We live, we die, and then we are forgotten. That is the way of things.

On mattering.Humans have psychological tension with the concept of mattering. To many, in order for something or someone to "matter", ultimately, death (at least death without transcendence to another plane of existence) cannot exist.

In the minds of many it is believed that any great thing someone does for humanity will, ultimately, not matter because one day everyone will die. Humanity will go extinct eventually, the universe will collapse in on itself eventually, and all that is more than nothing will be gone forever.

When you tell a human being that life has no inherit, built-in, eternal or god-given purpose, it poses an immense problem for them--best incapsulated in the question "What's the point of existence then?" or the concept of an existential crisis.

These philosophies (Nihilism, Absurdism, et al) simply tell you, the individual human happily living under whatever purpose-delusion you've created for yourself, that all purpose is delusion and nothing truly matters because everything ends.

Friedrich Nietzsche, who was not a Nihilist, warned us of the fallout of this when he said the thing he's most known for saying,

God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him. How shall we comfort ourselves, the murderers of all murderers? What was holiest and mightiest of all that the world has yet owned has bled to death under our knives: who will wipe this blood off us? What water is there for us to clean ourselves? What festivals of atonement, what sacred games shall we have to invent? Is not the greatness of this deed too great for us? Must we ourselves not become gods simply to appear worthy of it?

This isn't Nietzsche advocating for Nihilism, he's warning us.

We went from placing faith in Gods to placing faith in Institutions, which we are now tearing down to place faith in ever-shrinking ideas of shared identities and ideologies. The next obvious step is to put faith only in our individual selves.

But how will that work? A planet of people who place faith only in themselves? A planet of people so divorced from the ideas of shared belief, shared culture, shared values, and community... what does that world look like and how could it possibly function to the shared benefit of anyone?

Stoicism isn't a refutation of Nihilism, it's an answer to it.So we know nothing lasts forever, there's no afterlife, and this is all we've got.

What do we do with that information? Do we check out? Live like hedonists with no care for the future? Do we continue to tear down every last artifice we've used as platforms upon which to scream into the void and defy the truths of Nihilism? Do we give up? Do we sit alone in the darkness, devoid of any delusion of purpose?

Or could we, instead, do as Stoicism suggests?

Accept the truth, and build a worthwhile character and world in spite of it.

Not for some egotistical reason like eternal legacy, but because we are here now, right now, feeling things, experiencing things, and existing!

The modern stoic might say, and I would say it too:

"Life matters because it ends. Our time is limited, people will survive us, the suffering of life doesn't end with me, my children will inherit it. My friends children, too. I have barely any time to enjoy the experience of living, or to help others to enjoy it too, or to ensure that experience of living is healthy for the next generation to enjoy it as well. I have chosen to have a duty, a responsibility. It is true that I am but a cog in a great machine of life and death, but if I keep myself oiled and in great working conditions, I can effect every other cog's experience, and the machine's overall output. This isn't why I am here, but it is the thing I choose to do because I have chosen to care."

This is at the root of the philosophy of Stoicism: that in order to be good citizens, in order to take care of this world and our brothers and sisters in it, be those humans, animals, or ecosystems, we must discipline and shape ourselves into upright examples of living and caring things so that we can be living and caring things.

Everything depends on it.