Eric Enno Tamm's Blog: Eric Enno Tamm, page 2

March 12, 2011

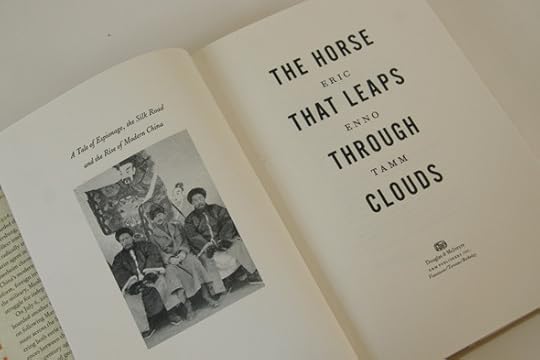

"A wonderfully fat new work of travel and history…" – The Diplomat

A century ago, Gustaf Mannerheim and Paul Pelliot took a portait with Kurmanjan Datka, the Queen of Alai, near Chigirchiq Pass. A century later, Eric Enno Tamm (far left) posed for a photograph with Sardarbek Ismailov (second from left), the great grandson of Kurmanjan Datka, and his relatives in a yurt atop Chigirchiq Pass.

Book review by George Fetherling in Diplomat magazine.

There's a connection to be made between Pearl Buck in China and The Horse That Leaps through Clouds (Douglas & McIntyre, $34.95), a wonderfully fat new work of travel and history by Eric Enno Tamm, of Ottawa. As the 19th Century melted into the 20th, writes the author, "Western technology and imported consumer goods — along with radical political ideas, democracy and Christianity — were spreading to every corner of the Chinese Empire," eliciting not joy but fear in Western capitals. One result was the so-called Great Game (the term popularized by Rudyard Kipling's novel Kim) in which Imperial Russia and Britain, along with France and some other European players, tried to out-spy one another to get control of Central Asia's oil and other resources (a story well told in The Great Game: The Struggle for Empire in Central Asia and other works by Peter Hopkirk).

Just as this tomfoolery was winding down, Russia sent Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim on a two-year espionage mission from St. Petersburg to the farthest reaches of northern and western China. In later life, Mannerheim (1867−1951) became a controversial national hero in his native Finland and, for a time, its prime minister.

But, in 1906, he was a colonel in the tsar's service, posing as an ethnographer and travelling with 16 steamer trunks on a mission that would last two years. Mr. Tamm sets out to retrace his famous predecessor's steps, following the same path across, for example, Eurasia, that "vast continent ruled by a bizarre patchwork of oil-soaked aristocrats, one outlandishly ruthless crackpot and the world's last major Communist regime and rising superpower."

A sophisticated journalist indeed, Mr. Tamm gathers observations like gemstones as he crosses "a gauntlet of political and geographical extremes, including some of the world's hottest deserts, highest mountains and cruellest dictatorships" stretching 17,000 kilometres. He is too clever to pretend he can intuit the future, but he clearly sees the present reflected in the past. For example, he notes while crossing Uzbekistan that "Khanates of blended races and tongues traditionally ruled Inner Asia. People identified themselves according to their local oases, their ruling dynasties and their allegiance to Islam. That didn't quite fit the Soviet concept of nationality."

"A wonderfully fat new work of travel and history…"

A century ago, Gustaf Mannerheim and Paul Pelliot took a portait with Kurmanjan Datka, the Queen of Alai, near Chigirchiq Pass. A century later, Eric Enno Tamm (far left) posed for a photograph with Sardarbek Ismailov (second from left), the great grandson of Kurmanjan Datka, and his relatives in a yurt atop Chigirchiq Pass.

Book review by George Fetherling in Diplomat magazine.

There's a connection to be made between Pearl Buck in China and The Horse That Leaps through Clouds (Douglas & McIntyre, $34.95), a wonderfully fat new work of travel and history by Eric Enno Tamm, of Ottawa. As the 19th Century melted into the 20th, writes the author, "Western technology and imported consumer goods — along with radical political ideas, democracy and Christianity — were spreading to every corner of the Chinese Empire," eliciting not joy but fear in Western capitals. One result was the so-called Great Game (the term popularized by Rudyard Kipling's novel Kim) in which Imperial Russia and Britain, along with France and some other European players, tried to out-spy one another to get control of Central Asia's oil and other resources (a story well told in The Great Game: The Struggle for Empire in Central Asia and other works by Peter Hopkirk).

Just as this tomfoolery was winding down, Russia sent Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim on a two-year espionage mission from St. Petersburg to the farthest reaches of northern and western China. In later life, Mannerheim (1867−1951) became a controversial national hero in his native Finland and, for a time, its prime minister.

But, in 1906, he was a colonel in the tsar's service, posing as an ethnographer and travelling with 16 steamer trunks on a mission that would last two years. Mr. Tamm sets out to retrace his famous predecessor's steps, following the same path across, for example, Eurasia, that "vast continent ruled by a bizarre patchwork of oil-soaked aristocrats, one outlandishly ruthless crackpot and the world's last major Communist regime and rising superpower."

A sophisticated journalist indeed, Mr. Tamm gathers observations like gemstones as he crosses "a gauntlet of political and geographical extremes, including some of the world's hottest deserts, highest mountains and cruellest dictatorships" stretching 17,000 kilometres. He is too clever to pretend he can intuit the future, but he clearly sees the present reflected in the past. For example, he notes while crossing Uzbekistan that "Khanates of blended races and tongues traditionally ruled Inner Asia. People identified themselves according to their local oases, their ruling dynasties and their allegiance to Islam. That didn't quite fit the Soviet concept of nationality."

December 25, 2010

Merry Christmas, Chairman Mao!

The seemingly only thing Chairman Mao and Santa Claus have in common is an infatuation with the colour red. After all, only a short time ago Ye Olde Saint Nick and his merry elves would have been attacked as counterrevolutionaries and agents of Western Imperialism in Communist China. But change is now fast afoot in China.

In 2006, I stayed in Beijing for two months over the Christmas season. The day I arrived at the Soho high-rise complex in the city's Central Business District, crews were erecting a ten-metre-tall Christmas tree in its plaza. My local supermarket, not far away, was festooned with Christmas decorations: Santa portraits, red and green banners, ornaments, fake Christmas trees, tinsel. I strolled the well-stocked aisles listening to "Jingle Bells" and "Santa Claus Is Coming to Town." Cashiers wore velvety elf hats. Beijing was awash in Santa's favourite colour—evidence of both a spiritual and consumer revolution sweeping the country.

Dialectical materialism—the Marxist theory that social conflicts over material needs are the driving force of history—is unraveling in China and being overshadowed by a new dialectic. The Communist Party has been so successful at meeting the material needs of its 1.3 billion citizens—at least for now—that many Chinese are finding themselves spiritually wanting. Economic growth rates are being eclipsed by the even more meteoric growth in the number of religious believers—primarily evangelical Christian converts, but also Buddhists, Taoist and Muslims.

The contradictory, yet complimentary forces of materialism and spirituality, like yin and yang, are profoundly shaping the country and present one of the greatest challenges to Communist rule.

Lets start with the temporal: the reform movement launched in 1978 by Deng Xiaoping has lifted a quarter of a billion Chinese out of poverty. Everyone's plight is improving, which is one reason why the Chinese, up to this point, have shown such a high level of tolerance for official corruption and grotesque levels of inequality. The legitimacy of the Communist Party rests largely on its ability to deliver jobs and rising incomes. Should that falter there could be trouble, as a restive population grows resentful towards the regime's corruption, greed and failures.

Yet China's rulers are damned if they do deliver economic growth and damned if they don't. Here's why: With their material needs met, an increasing number of Chinese have come to realize that they still aren't happy.

"After the Cultural Revolution, there was a collapse in the Chinese belief system," Linda, a student in Lanzhou, told me. "People are improving their material wealth. They are making a lot of money, but they are confused. They don't know what will make them happy."

She took me to the Catholic cathedral in downtown Lanzhou where we met a young priest. "People really need something spiritual to sustain them," he told us. "There's now a crisis of belief among the Chinese. In the past, people were forced to believe in Marxism and its propaganda. Some people have come to realize that Marxist ideology isn't so helpful in their daily lives."

During my six months traveling through China, I witnessed a country in the midst of a religious awakening. Even the Catholic church—as battered and emaciated as it is in the West—is growing in China. Wherever I travelled, I heard stories about underground house churches and saw churches and temples under construction.

In Jiuquan, near the western terminus of the Great Wall, I came across worshippers putting the finishing touches on a new church that could hold fifteen hundred people. "Hallelujah!" one old guy exclaimed as I entered the churchyard. One fifty-year-old woman, in her Sunday best, was wielding a pick axe, chipping away at old concrete to make way for a garden. Christianity is indeed blooming in China.

In the blighted industrial town of Taiyuan, I met a Western missionary who told me that many Chinese students talk about kongxu, or their "emptiness."

"There is a crisis of faith," the missionary told me. "There was a value system and it had a shiny head and red star. It collapsed and the emperor wore no clothes." The Chinese are now groping to fill that void. "There's an emptiness in people's hearts," he went on. "After 1989 [and the Tiananmen Square massacre], people said 'You can't put faith in the Party anymore.' "

In business-speak, missionaries are exploiting a gap in the spiritual marketplace. Evangelicals offer an irresistible two-for-one deal: the promise of a better life and a better afterlife. This offering—a blending of commerce and Christianity—is gaining loyal customers.

In 2010, the official number of Christians in China surpassed 28 million, but is likely as high as 90 million if the estimated number of worshippers at unofficial house churches is counted. "Nearly 69 percent of believers said they converted to Christianity after either they or members of their family fell ill," reported Li Lin, a researcher for the state-run Institute of World Religions which conducted a survey of religious worshippers in China. The survey found that the ecclesiastical boom is tied to China's economic boom. It noted that 73 percent of Chinese Christians joined the church after 1993, and nearly 18 percent of them between 1982 and 1992.

It would be wrong to just dismiss Beijing's Yuletide decorations as meaningless marketing ploys of cynical shopkeepers. It is certainly that, but it's also much more. Paradoxically, the material success of China's godless rulers has set the conditions for a spiritual reawakening in the country.

At the same time, Beijing gravely fears the divided loyalties of religious worshippers, as witnessed by their attempts to control Catholic and Protestant churches in China and brutally suppress Falun Gong.

And so, red is once again the revolutionary colour of China. This time, however, it is not emblazoned on banners and a little book of quotations, but on the nose of a reindeer named Rudolf.

December 20, 2010

One of 15 outstanding books of 2010 – Georgia Straight

Writers at Vancouver's Georgia Straight picked 15 books that "did the most to capture our imagination and get us talking… they've stuck with us the closest, and loom largest in our memory." The Horse That Leaps Through Clouds was picked as one of them. Here's what the reviewer Alexander Varty has to say:

Using Baron Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim's early-20th-century journey into the wilds of central Asia as his template, Canadian author Eric Enno Tamm embarks on a multifaceted exploration of the Great Game as it was played then and as it is being played today. Statesman, ethnographer, and Russian spy, Mannerheim is a fascinating character, but Tamm's most gripping conclusions have to do with China's commercial and territorial ambitions, which have not changed much despite the country's transformation from imperial power to industrial giant.

“a brilliantly complex piece of non-fiction storytelling” – TheTyee.ca

TheTyee.ca recommends The Horse That Leaps Through Clouds for “the person who likes to read spy stories alone in Chinese restaurants.” The reviewer goes on: “A Russian agent sets forth on orders to document China’s modernization and is stunned to see what’s going on there — in 1906. That yarn is intertwined with Tamm’s first-hand reporting on China today in a brilliantly complex piece of non-fiction storytelling.”

"a brilliantly complex piece of non-fiction storytelling" – TheTyee.ca

TheTyee.ca recommends The Horse That Leaps Through Clouds for "the person who likes to read spy stories alone in Chinese restaurants." The reviewer goes on: "A Russian agent sets forth on orders to document China's modernization and is stunned to see what's going on there — in 1906. That yarn is intertwined with Tamm's first-hand reporting on China today in a brilliantly complex piece of non-fiction storytelling."

December 10, 2010

A practical, though lethal, gift for the Dalai Lama

Gustaf Mannerheim met the Thirteenth Dalai Lama, Thupten Gyatso, at the holy mountain of Wutai Shan in 1908.

Excerpt from Chapter 17 of The Horse That Leaps Through Clouds published in the Ottawa Citizen.

"The Chinese authorities seem to guard the Dalai Lama closely," Baron Gustaf Mannerheim wrote in his diary in July 1908. The Russian colonel, who was on a secret intelligence-gathering mission in China, had just arrived at Wutai Shan, the most sacred of four Buddhist mountains in China. One of its mountaintop temples was, he wrote, "the present abode, not to say prison, of the Buddhists' pope, the Dalai Lama."

A Chinese army captain named Wang told Mannerheim that "a cordon of soldiers" guarded the approaches to Wutai Shan in northeast Shanxi province. In the event of an attempt to escape, Wang explained, the Dalai Lama "would be stopped, by armed force if necessary." But in his wanderings around Wutai Shan, Mannerheim saw no such cordon. "I could not help noticing, however, that [Wang] watched my movements with the greatest interest."

Wang urged Mannerheim to take him as his interpreter during his audience with the Thirteenth Dalai Lama. But a Tibetan prince had already secretly informed Mannerheim that Wang was not welcome. The Tibetans despised Wang, whom they considered a spy, and prohibited him and his troops from the inner precincts of the temple.

Wutai Shan was more podium than prison for the Dalai Lama. Upon arriving here in the spring of 1908, His Holiness sent messages to the Peking Legations inviting envoys to visit. William Woodville Rockhill, the American ambassador to China, was the first. He pulled on his walking boots and set out for Wutai Shan on foot, a five-day trek from Peking. Rockhill was a scholar and diplomat who had explored Inner Asia in the 1890s and spoke Tibetan. He had left Wutai Shan only a day before Mannerheim's arrival.

"The Talé Lama seems to me a man of undoubted intelligence, open-minded… a very agreeable, kindly, thoughtful host, and a personage of great dignity," Rockhill reported back to President Theodore Roosevelt. The Dalai Lama told Rockhill about his struggles against the Chinese and how his country's remoteness meant Tibet had "no friends abroad." Rockhill assured His Holiness that he was mistaken: Tibet had many foreign well-wishers who hoped to see Tibetans "prosper and happy." Later, during the Dalai Lama's visit to Peking, Rockhill became a confidant to the Tibetan leader, quietly pushing a rapprochement with the Chinese.

In the summer of 1908, the Dalai Lama received a parade of envoys: a German doctor from the Peking Legation; an English explorer named Christopher Irving; R.F. Johnson, a British diplomat from the Colonial Service; and Henri D'Ollone, a French army major and viscount. The Dalai Lama hoped to patch up his relations with Britain after its invasion of Lhasa in 1904 and bolster his international standing. These first audiences with the mysterious Buddhist pontiff were much anticipated.

On his second day in Wutai Shan, a messenger ran into Mannerheim's room in the Tayuan Temple and gestured that the Dalai Lama was ready to receive him. Mannerheim duly prepared himself. While he was shaving and changing his clothes, another frantic messenger arrived to express the Dalai Lama's impatience. "I was just as impatient," he wrote, "but could not possibly dress any faster." A few minutes later, an anxious Tibetan prince appeared to ask what Mannerheim meant by keeping His Holiness waiting. At a swift pace, the Baron and prince climbed the steep staircase to Pusading Temple.

Staircase to the Pusading Temple in Wutai Shan

Wang, in full dress uniform, was waiting at the top with a Chinese honour guard. The Chinese had reason to worry about Mannerheim's visit. Chinese authorities had just arrested two Russian military officers who were inciting the Mongols to break from China and become a Russian protectorate. During his stay in Urga (now Ulan Baatar), the Dalai Lama sent messages to the Tsar through various envoys. His Holiness told one Russian military intelligence officer that both Tibet and Mongolia should "irrevocably secede from China to form an independent allied state, accomplishing this operation with Russia's patronage and support, avoiding bloodshed." If Russia wouldn't help, the Dalai Lama insisted, he would even ask Britain—his former foe—for help. After his visit with the Dalai Lama, Mannerheim, in fact, trekked to Inner Mongolia to gauge the rebellious mood of the Mongols.

Wang could barely hide his wrath when Mannerheim told him that he could not attend his audience with the Tibetan pontiff. The Chinese captain argued with two of the Dalai Lama's assistants. As the Baron slipped into a small reception hall, he caught sight of Wang "making vain efforts to force his way in behind me."

The Dalai Lama sat on a gilded armchair placed on a dais along the back wall of the small room. Two old Tibetans, unarmed, with beards and hair speckled with grey stood behind him. The Dalai Lama was frocked in "imperial yellow with light-blue linings" and a "traditional red toga." The thirty-three-year-old pontiff had a dark brown face, shaved head, moustache and a tuft of hair under his lower lip. His eyes were large and his teeth gleamed. Mannerheim noticed "slight hollows in the skin of his face, which are supposed to be pockmarks." He appeared a bit nervous, "which he seems anxious to hide." Otherwise, Mannerheim thought he was "a lively man in full possession of his mental and physical faculties."

Mannerheim made a "profound bow," which the Dalai Lama acknowledged with a slight nod. They exchanged silk scarves. His Holiness began with small talk, asking Mannerheim about his nationality, age and journey. The Dalai Lama then paused and, twitching nervously, asked if the Tsar had sent a secret message for him. "He awaited the translation of my reply with obvious interest," wrote Mannerheim, who informed him that he hadn't the opportunity to personally speak with Tsar Nicholas II before his departure. The Dalai Lama then gestured, and a beautiful piece of white silk with Tibetan letters was brought out. It was a gift that Mannerheim was to deliver personally to Nicholas II.

The Dalai Lama told Mannerheim he had been enjoying his journeys in Mongolia and China, but "his heart was in Tibet." Many Tibetans were urging him to return. His officials claimed up to twenty thousand pilgrims visited the Dalai Lama each month, but Mannerheim thought it was "an undoubted exaggeration." The Tibetan pontiff was in the midst of a showdown with Empress Dowager Cixi, who wanted him to come to Peking to perform the kowtow. The Dalai Lama, Mannerheim wrote, "does not look like a man resigned to play the part the Chinese Government wishes him to, but rather like one who is only waiting for an opportunity of confusing his adversary." The wily Tibetan pontiff had postponed his journey so many times that a joke was circulating in Peking referring to him as the "Delay Lama."

Mannerheim spoke encouragingly about Russia's sympathies for Tibet's struggles against the Chinese. Russia's troubles were over, the Baron assured him, and "the Russian Army was stronger than ever." Now, all Russians watched His Holiness's footsteps with great interest, he added. The Dalai Lama, Mannerheim recalled, "listened to my polite speeches with unconcealed satisfaction."

Twice the Dalai Lama ordered his bodyguards to check if Wang was eavesdropping on their conversation. It was a dangerous time for the Dalai Lama, who knew his life may be in danger if he returned to Lhasa. The Chinese were tightening their grip on Tibet. Lamas were being assassinated, monasteries plundered and Tibetans evicted from their nomadic pastures. Peking needed the Dalai Lama to be a compliant vassal who could calm his restless followers and ease Tibet's incorporation into the Chinese Empire.

But the Dalai Lama proved defiant. He visited Peking that September and immediately fell out with the Imperial Court, which issued a decree demoting him to "a loyal and submissive Vicegerent bound by the laws of the sovereign state." A prominent Imperial censor also openly denounced him as "a proud and ignorant man." Rumours spread in Tibet that he had been assassinated. Outraged at various reforms, lamas threatened a "holy war" against the Chinese. By the end of 1908, a rebellion broke out, leading to the defeat of Chinese troops. The Dalai Lama eventually returned to Lhasa in 1909 and sent telegrams to Britain and all European countries attacking Peking's claim over Tibet.

In February 1910, Chinese troops invaded Lhasa. The Dalai Lama fled to India. An Imperial decree denounced His Holiness as "an ungrateful, irreligious obstreperous profligate who is tyrannical and so unacceptable to the Tibetans, and accordingly an unsuitable leader of Lamas." After the fall of the Qing Dynasty, His Holiness returned to Tibet in 1913, declaring the country independent. He died in 1933, leaving a prophetic last testament for the next Dalai Lama:

We must guard ourselves against the barbaric red communists… the worst of the worst. It will not be long before we find the red onslaught at our own front door… and when it happens we must be ready to defend ourselves. Otherwise our spiritual and cultural traditions will be completely eradicated… and the days and nights will pass slowly and with great suffering and terror.

Recognizing the clear and present danger, Mannerheim offered the Dalai Lama an unusual, though practical, gift: a Browning revolver. The Baron apologized that he didn't have a better offering, but explained that after two years' journey he had no other items of value. The Dalai Lama laughed, "showing all his teeth," as Mannerheim showed His Holiness how to quickly reload seven cartridges into the revolver. The Dalai Lama relished the demonstration. "The times were such," Mannerheim wrote, "that a revolver might at times be of greater use, even to a holy man like himself, than a praying mill."

From The Horse That Leaps Through Clouds: A Tale of Espionage, the Silk Road and the Rise of Modern China by Eric Enno Tamm. Copyright © 2010 by Eric Enno Tamm. Published by arrangement with Douglas & McIntyre.

November 2, 2010

The Soot Road: Trekking along one of the most polluted energy corridors on Earth

Excerpt from Chapter 17 of The Horse That Leaps Through Clouds published in the Ottawa Citizen, September 29, 2010

In 2006, I celebrated the 800th anniversary of Genghis Khan's inauguration as Mongol ruler at a Mongolian restaurant in Hohhot, the capital of China's Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region.

It was a bittersweet affair. Once the base of Genghis Khan's empire, Inner Mongolia seemed hardly Mongolian at all. Only four million people, about 17 per cent of the region's population, are ethnic Mongols. In Hohhot, it's even less, about 10 per cent. The rest, by and large, are Han Chinese. The dramatic influx of Chinese began a century ago, the final conquest of a settled, agrarian civilization over pastoral nomads.

"Genghis Khan didn't like to drink so much," said Buhchulu, a Mongolian folklore researcher at the Inner Mongolia Academy of Social Sciences, pouring me another glass of "Great Wall" brand red wine. "He said a man should drink only three times a month."

"How do you know he said that?" I asked.

"Folklore. We have a lot of oral stories. If you travel in the Inner Mongolia countryside you can hear a lot of stories of Genghis Khan," Buhchulu said. "Mongols remember very clearly about Genghis Khan just like it was yesterday. It was 800 years ago, though. The tales aren't necessarily true, but they are oral stories." A book titled Genghis Khan's Word, he said, was still wildly popular among Mongols. It is a compendium of sayings that have been passed down from generation to generation.

"For example," Buhchulu said. " 'Don't wash clothes in rivers and lakes.' That's a rule of Genghis Khan."

The folklorist then paused and leaned back pensively.

" 'Don't cut the trees freely. It's not good.' That's another saying of Genghis Khan."

"He sounds like an environmentalist," I said.

That prompted Buhchulu to quote yet another saying of this medieval eco-crusader: " 'Don't freely dig up the earth!' "

Freely digging up the earth is exactly what I saw during a long, numbingly cold bus ride the next day to Genghis Khan's mausoleum in the heart of the Ordos prefecture.

From Hohhot, the bus drove along the southern foot of the Daqing mountain range. Fallow farmland and fields of broken corn stocks lined the highway. After an hour, the cornfields gave way to rammed-earth greenhouses with coal-burning stoves and retractable reed roofs to keep crops from freezing during the bone-chilling nights. In the steely morning light, I saw Chinese farmers rolling back the reed mats as the sun climbed into the sooty sky.

Despite water shortages, poor soil and a severe climate, Han Chinese farmers had already begun to dig up this Mongol pastureland a century ago. By 1908, Chinese colonists had settled all the way to the modern city of Baotou, where the highway now swings south across the Yellow River into Ordos. As we drove south along Route 210, farmland became scarcer, replaced by sand and prickly shrubs. After 125 kilometres, the bus arrived in Dongsheng, the capital of Ordos prefecture.

Ordos covers some 87,000 square kilometres. It is bounded on three sides by the Yellow River, which makes a dramatic elbow-shaped detour into Inner Mongolia from Central China. Almost 50 per cent of the prefecture is desert, which deposits 100 million tons of yellow sand into the river each year. The rest of Ordos is a wilderness of mangy pasture. These lands had once been home to powerful Mongol clans, but by 1908 up to 30,000 Chinese had colonized the area.

The prefecture, with a population of 1.5 million, is now 88 per cent Han Chinese. So many Chinese farmers dig up so much of Inner Mongolia that most sandstorms in Beijing, some 600s kilometres to the east, occur during March and April, when farmers till their chalky fields for the spring planting. Vicious windstorms blow away the topsoil, leading to horrendous erosion and gritty squalls throughout Northern China. In Ordos, deserts have been growing at an alarming rate. Excessive cultivation, over-grazing and drought have degraded the natural grassland. As a result, the Chinese government has relocated 400,000 farmers from the margins of Ordos's two deserts into the city and surrounding townships.

Despite its declining agricultural land base, the prefecture was experiencing phenomenal growth: GDP had skyrocketed 40 per cent this year, the sixth-fastest-growing city in China. As it turns out, the Chinese have found an even more lucrative way to dig up the earth than tilling the soil.

The previous year, Ordos had overtaken Datong as the country's coal capital, producing 150 million tons. The prefecture's proven coal reserves of 168 billion tons account for one-sixth of China's total.

Leaving Dongsheng the next day aboard another bus, I watched hundreds and hundreds of coal trucks streaming north. The convoy of orange, green and purple trucks — and even three-wheeled motorized carts heaped with coal — stretched almost a hundred kilometres. It ended at the Shulinzhao power plant just south of Baotou. Dozens of cranes were completing what looked like a massive expansion. Clouds of steam rose from a half-dozen cooling towers. New smokestacks painted with red and white stripes looked like gigantic candy canes.

A century ago, Peking reined in the corrupt military governor of Inner Mongolia for his greed and ambition in colonizing the grasslands. Inner Mongolia is again under the control of rogue officials. The construction of illegal coal-burning power plants was largely driving Inner Mongolia's excessive growth. Unlicensed power plants worth some $5 billion U.S. were under construction, despite repeated orders from Beijing to stop. The previous year, six workers died and eight others were injured at one illegal construction site. The scandal provoked Beijing to send an investigative team to Inner Mongolia. The regional Party Chairman was forced to hand in a "self-criticism." Seven other officials were disciplined, and two more faced prosecution.

China burns 42 per cent of the world's coal and is adding the equivalent of nearly the entire U.K. power grid each year in new coal-fired plants. Northern China's smokestacks spew a noxious cloud so gargantuan that satellites have tracked it floating over the Pacific. Mountaintop sensors in Washington, Oregon and California have detected sulphur compounds, carbon and other toxic byproducts from China's smokestacks. The country's coal plants have become the main cause of the rapid increase in greenhouse gas emissions that cause global warming. Coal will remain king in the foreseeable future too: it represents 60 per cent of the world's remaining recoverable hydrocarbon reserves.

As I watched carbon streaming from the towering funnels, I realized that the route I had trekked was a veritable "Soot Road," the newest iteration of that storied trade route of yore. A World Bank environmental report on China later confirmed my suspicion: my route retracing the journey of a Russian secret agent from a century ago traversed what are now the most polluted areas of China, perhaps even the world.

The Soot Road is the greatest energy corridor on Earth in terms of the production, distribution and consumption of fossil fuels. The region holds 33 per cent of the world's proven gas reserves and 36 per cent of the world's coal, plus almost nine per cent of the world's oil. One hundred and eight thousand kilometres of pipeline in Central Asia and China now replace the old caravan routes.

#maker_map_14845 {width: 100%; height: 400px;}

From the oil-soaked autocracy that is the New Russia, I flew to the boomtown of Baku and followed these new pipelines across the deserts and steppes of Inner Asia. In Xinjiang, China's western region, I saw oil refineries on the edge of the Taklimakan, coal mines cut into the Tian Shan range, coal-fired power plants in every oasis and massive petrochemical plants on the outskirts of Urumqi.

I then shadowed the pipeline route to the steel mills of Jiayuguan and choked on the photochemical smog belching from Lanzhou's vast oil refineries. Heading east to Central China and then north into Inner Mongolia, I soon found myself in coal country and in the most polluted cities in the world. Yet it wasn't until I arrived in Ordos, China's fledgling new coal capital, that I came to a brutal realization about the sooty trail that I had been trekking.

What happens on the Soot Road will likely determine the future of the world, especially as a rising China extends its influence in Central Asia through new energy and security alliances, such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Yet this New Great Game is already nearing its endgame. China is depleting its mammoth coal reserves faster than any other country, and peak oil, according to some analysts, is already upon us. As the region's hydrocarbon reserves are drained, the rivalry for their remaining riches may grow more intense.

At the same time, global warming is likely to produce severe environmental shifts that could prove deadly to this dusty region already suffering from drought, desertification and pollution. Energy conflicts, increased social and environmental stresses on an already vulnerable population and growing Islamic radicalization caused by ruthless regimes could further rock the region — and the world.

In this new rivalry, China is no hapless pawn. In 2009, for example, China completed its first direct oil pipeline (some 2,200 kilometres) to the Caspian Sea through Kazakhstan and opened an 1,800-kilometre gas pipeline to Turkmenistan that undermined Russia's long-standing dominance over Central Asia's natural gas. Beijing is profoundly changing the rules of the game.

I was now dying — in more ways than one — to get to Beijing, the terminus of my journey. I had been travelling the Soot Road for nearly five months, covering more than 15,000 kilometres by train, plane, ferry, car, horse and camel. In that time, I had slept in 47 different hostels, hotels, inns, private homes, yurts, tents, train sleepers and even a converted tractor-trailer at the Irkeshtam Pass on the Kyrgyzstan-Chinese border. On Nov. 16 in Dongsheng, I woke late and wrote in my journal:

"I don't feel well this morning — low energy and a sore throat from the dry climate and dust and pollution. I don't even feel like getting out of bed. What is there to see? I'm in a provincial industrial town. I must have passed through a hundred just like it."

Leaving Ordos by bus later that day, the weather bitterly cold, my mind became gripped by an apocalyptic vision from the past. Peering out at the endless caravan of coal trucks thundering down the highway in clouds of black dust, I was reminded how the world must have trembled at the sight of the dust storms kicked up by the hooves of advancing Mongol armies. Eight hundred years later, we still have much to fear from the land of Genghis Khan.

Excerpted and adapted from Chapter 17 of The Horse That Leaps Through Clouds: A Tale of Espionage, the Silk Road and the Rise of Modern China by Eric Enno Tamm. Copyright © 2010 by Eric Enno Tamm. Published by arrangement with Douglas & McIntyre.

November 1, 2010

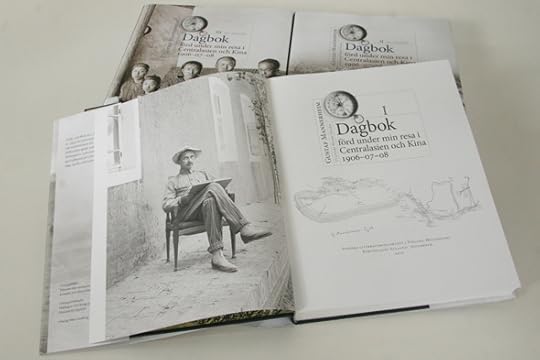

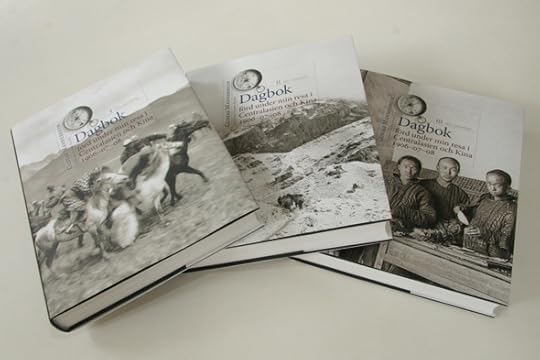

New edition of Mannerheim's Asia diary nominated for Finnish book award

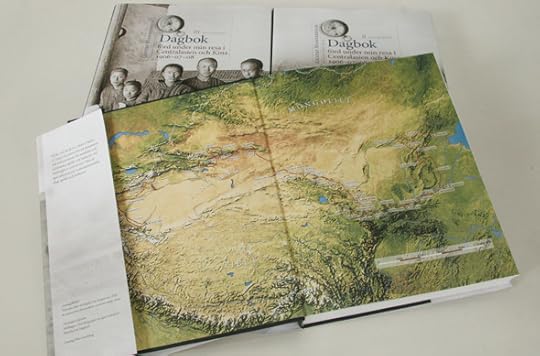

The books' design is both beautiful and classic, evoking the grand traditions and artistry of 19th-century travelogues.

Harry Halén, a philologist and the foremost expert on Gustaf Mannerheim's Asian expedition, has just been nominated for the Teito-Finlandia book award for nonfiction for his masterful new edition of Mannerheim's travelogue. Like his original diary, or dagbok in Swedish, this three-volume book is in Mannerheim's mother tongue. Co-published by Svenska litteratursällskapet in Helsinki and Atlantis Books in Stockholm, it has been called "an ethnographic gold mine."

Here's my original blog post describing the book. And Here's what the Teito award's jury had to say about the book:

Harry Halen (Editor): Gustaf Mannerheim: Diary Performed during my trip to Central Asia and China 1906-07-08. Helsinki: Society of Swedish Literature in Finland & Atlantis, 2010.To date, the travel diaries, which the Tsarist officer Mannerheim took during his more than two year-long visit to Central Asia and China, have been released only in abbreviated form. The photographs have been published twice separately.

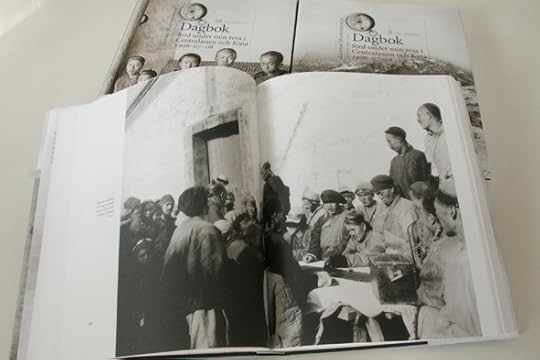

The entire diary, which is now published in three parts, totals almost 1200 pages and goes beyond the diary entries to include other more personal notes, drawings, sinologist terminology and details of the equipment needed for the trip. About 170 of Mannerheim's 1,000 photographs have also been published. Many of these have not previously been available in print.

As a connoisseur of languages and cultures in Central Asia, Harry Halén masters the content throughout. He has also modernized the diaries and place names so that they comply with modern spellings.

The travelogue presents Mannerheim's multifaceted mission in Asia. He served as the Russian expatriate cartographer, made anthropological observations and collected items for Finland. The notes reveal the true character of the journey. His spy mission was masked as a scientific expedition. The purpose was to serve Imperial Russia's expansion efforts in China's direction.

In the diary entries, the real man appears which are better than the memoirs which were written decades later by the great man and field marshal.

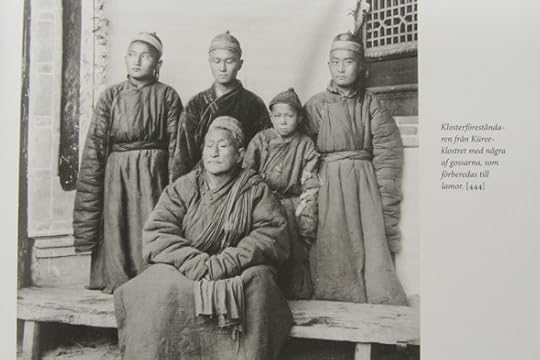

The technically brilliant photographs convey the journey efforts, but also the fascination and genuine interest of the people you met during your journey.

The opening pages of the book show Mannerheim seated at the Russian consulate in Kashgar, China.

Photo editor Peter Sandberg has succeeded in creating visually compelling volumes.

The facial complexion on these Kalmyk monks has been lightened.

Evocative photographs, beautifully reproduced, give the volumes visual umph!

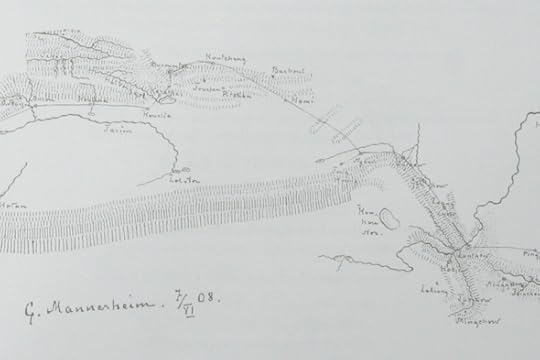

A hand-drawn map by Mannerheim of his route through China.

This satellite map of Mannerheim's route on the volumes' endpapers is disappointing and feels out-of-place. I would have preferred a black-and-white reproduction or perhaps even Mannerheim's hand-drawn map.

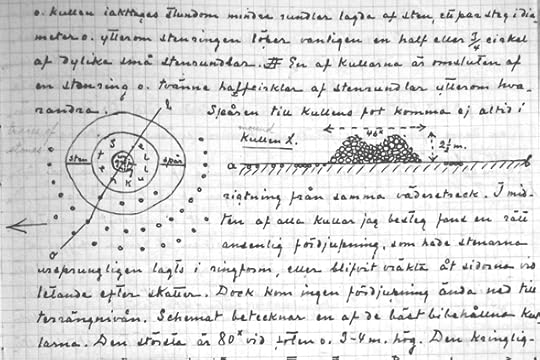

Here are diagrams in Mannerheim's original hand-written diary.

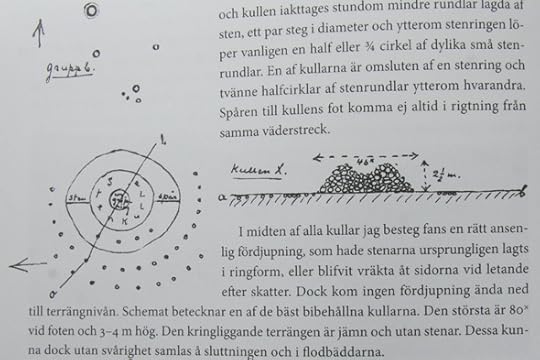

Here are those same diagrams reproduced in Halén's new Swedish edition.

A small drawing of a hut in Halen's new Swedish edition.

Tables have been introduced into Halén's new edition.

A masterful new edition and magnum opus.

.

October 25, 2010

The next emperor of China

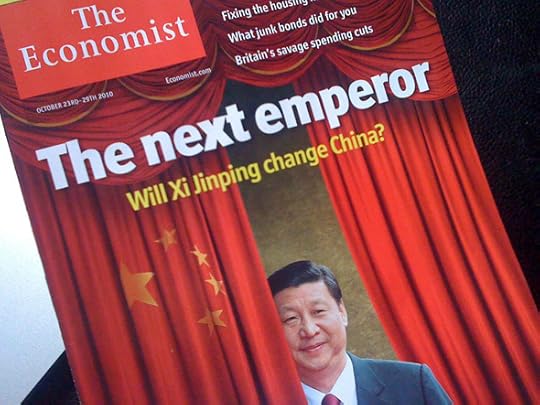

The Economist ran a typically cheeky cover on this week's issue showing a photograph of an elusive Xi Jinping poking out from behind a red curtain under the headline "The next emperor." On Oct. 18th, Xi was appointed Vice-President and given a new job as vice-chairman of China's Central Military Commission. That was enough for The Economist to dub him the "crown prince" of "a vast kingdom facing vaster stresses." He is likely to take over command of both the Communist Party and the Presidency of the republic in 2012.

The Economist's cover is both cheeky and prescient: China's Communist leaders are, in fact, ruling and reforming the country much like the late Qing Dynasty a century ago. Back then, the Manchu rulers instituted widespread reforms in almost every sphere of life in China. The empire underwent massive social and economic transformation. There is one area, however, where the Imperial rulers of yore, like the Communists today, refused to make significant changes. That's political reform, an issue which The Economist correctly raises as central to China's future.

A lack of political reform makes the ruling regime especially vulnerable in the face of slowing growth and rising expectations from its citizenry. As I point out in my book, the country is beset by innumerable challenges:

violent ethnic unrest sporadically flares up among the Uyghur and Tibetans; the population is aging at a troubling rate thanks to the one-child policy; selective abortion has created a dangerous imbalance of young men in parts of the country; corruption is rife; an angry nationalism is percolating among the disenfranchised; vast areas appear on the verge of ecological collapse; climate change could seriously undermine food security; the stock exchange, according to one economist I met, is "a gaming casino;" there aren't enough good jobs for millions of graduates; many state-owned enterprises remain stubbornly inefficient; easy credit, politicized lending and murky balance sheets threaten the stability of the banking system. Many of these problems are interconnected so that a crisis in one area could spill over into others, potentially leading to widespread social breakdown. The Communist Party thus maintains a seemingly iron grip, recognizing that it faces stresses unimaginable to the Manchus a century ago.

Yet what China really needs is to loosen censorship over the media and begin to institute more significant political reforms, especially at the local level where citizens are often the victims of callous and corrupt officials. More accountable government and legitimate avenues (elections) that allow citizens to air their concerns and grievances will help to create a more stable and prosperous China.

Of course, while things are going well – and they have been going well in China despite the Great Recession in the West – there is little demand for political reform, even from the bottom up. It is when things aren't going well that there will be vocal and strident demands for political reform. That's why the Communist Party is so focused on growth and employment: keeping its citizens happy will stave off calls for political reform. The cautionary tale from the Qing Dynasty, however, is that if political reform is "too late, too little" then social and economic crises can snowball into a political crisis and widespread social unrest. That's ultimately what happened in 1911 when the Qing Dynasty was overthrown.

"Too many Westerners… assume that they are dealing with a self-confident, rational power that has come of age," The Economist cautions. "Think instead of a paranoid, introspective imperial court, already struggling to keep up with its subjects and now embarking on a slightly awkward succession—and you may be less disappointed."

As The Economist rightly points out, China is a fragile empire. I expect that as economic growth slows, there will be growing calls for political reform. Eventually, a tipping point will be reached, and the demands will then come fast and furious. Many will be surprised by this rapid development. But for anyone willing to look, the writing isn't just on the wall, it's also in the history books.