Geneva Durand's Blog, page 3

July 5, 2022

Behind the Scenes: Port Royal

This bustling port scene was a four-day collaboration between my brother Isaiah and I. It’s got lots of tiny details, forced perspective, palm trees, and those obnoxiously difficult things to build, gabled roofs.

Like most all-LEGO scenes, it was hard to get all the details in one shot!

The whole MOC is pretty large, with the biggest section being the houses and port. You can also see the lights under the water in this picture, though unfortunately they didn’t really come through at all in the final angles.

I built all the tudor houses, which aside from the roofs, were pretty fun. I used a lot of the relatively new 1×1 hump pieces to add some texture to the walls and built the stonework on the bottom with lots of half-plate offsets and sideways bricks.

It was fun to find multiple scales for the same object–like the barrels, which are full size in the foreground, then the size of an upside down pail, and finally just a round 1×1 brick.

The same for the palm trees, which gradually became shorter and with less leaves until the farthes ones are just the tiny 3-leaf stems on brown horns.

This microscale ship was built separately by Isaiah, but it was just the right size for our collab here, so although it’s barely visible in the final pictures, it’s there and fully rigged!

The build started with this house, and from there I down-scaled my techniques to build the smaller tudor houses.

Of course, none of the houses are 360 viewable. This one has some scaffolding around back.

On this next one you can see better what I did for the stone work–mostly brackets and bricks with studs on one side, but a few clip and bar connections too.

The mountains around back are completely sideways–a technique that allowed us to build fairly large mountains without using too many pieces.

Of course, the best part of this creation was building all the little crates and boxes for the foreground! I had fun with the turtle cage especially.

You can find the story this build is meant to tell on Eurobricks, and you might also enjoy looking behind the scenes of some of my other creations:

LEGO Fighting PitBehind the Scenes: Forbidden FriendshipBuild Log: WaterwheelBehind the Scenes: Space Travel PosterBehind the Scenes: Red SeaBehind the Scenes: Fire!Behind the Scenes – LadyhawkeBehind the Scenes: Space TankBehind the Scenes: A Forest DriveBehind the Scenes: Tea ShopBehind the Scenes: Rice TerracesBehind the Scenes: Qarkyr Box GardensApril 7, 2022

LEGO Castle

I’ve been a “castle builder” almost as long as I’ve been a LEGO builder–the medieval theme was my first love, and I’ve built scenes of knights chasing pigs, fighting battles, confronting dragons, riding through cathedrals, battling snowstorms, being ambushed in forests–you name it! But I had never built a proper castle for my knights until… well, until now!

I have two dream castles: one is almost a palace, set in a beautiful landscape, with hundreds of towers and sparkling crenellations and stuff like that. This one is the other one: a compact stone affair with every possible convenience and inconvenience I could squeeze into such a tiny space.

Of course, that includes a working drawbridge.

I’ve yet to figure out what the truly proper direction for the slopes at the top of the battlement crenelations on a castle really is: should they slope out, so the arrows glance harmlessly upward, or should they slope in, so as to present the maximum defense height? I slightly suspect that medieval builders didn’t know either and just did whatever struck their fancy at the moment. The outward slope seemed to suit this castle, so that’s what I ended up with.

As you can see, this castle doesn’t have a very big footprint–less than 32×32 when it’s all shut up.

Nevertheless, it’s packed full of details, starting with a floating cobblestone floor on the bottom. I was slightly lacking in foresight here; I built the walls first and then had to carefully lower each piece of loose cobblestone into place!

Around back I broke up the grey walls with this tudor-style corner building. I chose black and white to be in keeping with the Black Falcon’s colors.

My first plan for the edges of this large tower was to use 1×2 tiles all the way up–but I quickly ran out and so the tower got a more weathered look.

Inside are three rooms–the bottom one is an armory, with a weapons rack, a statue, a chest, and opening doors.

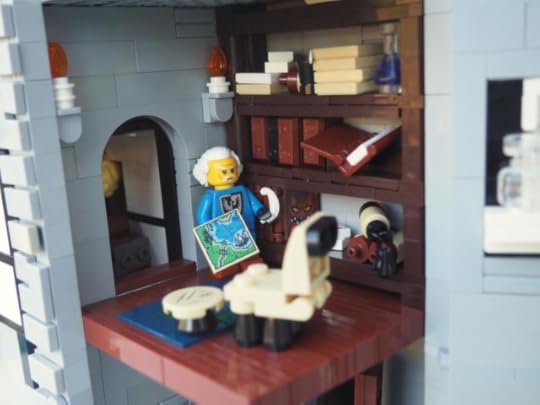

Next is the library, full of books and scrolls and papers!

The highest story is the owner’s bedroom, complete with a canopy bed…

…and a chandelier that actually swings!

One of the hardest parts of this build was the roof over the tudor section, especially the corner.

I wasn’t able to get quite as smooth a seam as I would have liked, but it didn’t turn out too bad.

Under this roof is the dining hall and fireplace.

Underneath that are the stables!

As you can see, you have to take the chimney off to access the stables. In fact, the chimney locks the roof in place and keeps everything snuggly together.

And there you have it: the first minfigure-size castle I’ve ever built, but hopefully not the last!

You might also be interested in these other creations I’ve built:

LEGO WindmillLEGO Fighting PitBuild Log: WaterwheelBuild Log: Classic Pirates FortBuild Log: Seaside FortBuild Log: LEGO Ninjago ScrollBuild Log: Wading PoolBuild Log: Ninjago Legacy LighthouseMarch 5, 2022

Wayland Terraformers, INC: A Little Bit of Everything

This story was inspired by a recent collaborative LEGO project I did with my siblings. I enjoyed caricaturing our personalities for the story.

Jaydie (Geneva), H.O. (Josiah), West Alia (Anna), Bronth (Isaiah)

Jaydie (Geneva), H.O. (Josiah), West Alia (Anna), Bronth (Isaiah)Jaydie was late to lunch as usual and H.O threw a sandwich at her. “You missed the briefing,” he said.

“No one told me it was an important one,” Jaydie said, deftly catching the sandwich as it floated through the hatch.

“You’re supposed to be at ALL the briefings,” said Bronth, lazily stretched out on the roof, sucking a straw. “Also this one was actually important.”

“Sorry, decided getting the ship’s reserve air condensers back up and running was more critical. You’ll have to fill me in.”

“Well,” Bronth said, sitting up and flipping his holographic visor down over his face, “when the meeting started we were at T minus two hours of landing on Craxis L. Now it’s T minus forty-three minutes.” He touched the right of his visor and swiped, looking for the first slide.

“Craxis L? Krancore owned, isn’t it?”

“Krancore owned,” Bronth nodded.

“Doesn’t Krancore usually work with Aegis?” Jaydie asked.

“Not anymore,” H.O. said smugly. “After Parute last week we are now the heroes of terraforming.”

“Really? I didn’t think Parute went that well,” Jaydie said.

“It didn’t. Don’t listen to H.O. He just likes it when he gets to leave craters behind.” West Alia looked up from her spot at the control panel.

“We came out of that place in a cloud of blue Limium smoke, you all in the ship and me swinging along behind, popping holes in the obnoxious gators that wouldn’t let us do our job,” H.O. bragged. “It got televised from Station Alpha to Stroid 764. It was gorgeous.”

“Well back to Krancore,” Bronth said. “They usually do work with Aegis, but Aegis refused to go in on this one, I’ve forgotten why. The mission’s pretty straightforward. Aegis planted Craxis thirty years ago and these days it’s one of Krancore’s biggest rice exporters, but on-planet farmer units show unusual plant-based biological activity on the wetland fringes. So Krancore wants some samples of the flora, especially anything you wouldn’t expect on a rice planet. Just gotta get in, get samples, get out. We do this job well, Krancore might be bringing us their next job. If not, they might go back to Aegis.”

“Sounds simple,” Jaydie said.

“There is a hitch. Craxis is in a Stroid belt, so this baby”—he slapped the ship’s side lovingly—“and I will have to wait outside. And you three will have to barcloud in.”

“So not so simple.”

“Aw, barclouding’s not so bad,” H.O. shrugged. “Did it once. The dangers are exaggerated. Stay tight on the bar, watch out for meteors. You’re good.”

Jaydie stared at him. “I used to barcloud for a living,” she said.

“Oh.”

“That’s how I lost my left arm.”

“But you have your left arm,” West Alia said.

“Only ‘cause I got it back again.”

“Oh—I remembered why Aegis wouldn’t go in,” Bronth said. “The Stroid belt around Craxis has an ionic barium ring. You can’t take an Ava shield through it. That doesn’t matter to you, you’ll be barclouding in anyways.”

Jaydie frowned. “You can run an Ava shield through ionic barium just fine. Who told you that’s why Aegis wouldn’t take it?”

“Krancore said so.”

Jaydie shook her head.

“T minus thirty-eight minutes,” West Alia said. “Here’s where we rev up the barclouds.”

“All right,” Bronth said. “Remember, get in, get the flora, get out. You’ll be taking all the samples, West?”

West Alia nodded, double checking the contents of her instrument case and scrolling at a breakneck pace through pages of her holographic clipboard.

“H.O., your job is protection. We would rather not leave craters, so try to keep it low profile.”

“Low profile,” H.O. said, slapping his plasma blaster.

“Jaydie—if anything goes wrong, you’re there fix it. Now I’m off to the controls. You three will be jumping in T minus fifty seconds.”

Jaydie buckled on her tool belt and strapped her handheld power saw to her wrist. She slammed her visor shut and adjusted the airflow. “Y’all ready for the Stroids?” she asked.

“Ready to hit some rocks!” H.O. replied, and his voice crackled clearly through the comms system on her helmet.

West Alia spun the knobs on the ship hatch and the door flew open.

Bronth’s voice came over the ship loudspeaker. “Jumping in 9… 8… 7…”

Jaydie gave her unit one last check. Air? Moisturizer? G-suspension? Comms was obviously fine, you could hear H.O. trying to whistle.

“4… 3… 2… 1!”

“Whooo!” That was H.O., jumping feet first out of the ship, spinning wildly on his bar, shooting two aimless blasts into empty space.

West Alia was already lying flat on her bar, slicing toward the Stroid field.

Jaydie clicked her boots into position and followed her lead.

“So when did you barcloud for a living?” H.O. asked over the comms.

“Back during the Vengeance. I planted Stroid mines.”

“The Peace put you out of a job?”

“Did free-lance repairs until West Alia offered me this,” Jaydie said, slapping the Wayland Terraformer badge on her speedsuit.

West Alia’s voice cut H.O. off before he could reply. “You two might want to concentrate, my scanner is picking up a high ratio of meteors.”

Jaydie focused on the space ahead, where a belt of moving asteroids stretched between them and their destination, Craxis L. She adjusted her trajectory slightly toward the left and seconds later went zipping past the first rock.

“Oh look, a comet!” H.O. said. “Make a wish!”

“That was just a stroid,” Jaydie said.

“No, not that one, the other one,” H.O said. “Oh ow! I’m fine guys, I’m fine!”

“What happened?” West Alia asked.

“Just a pebble sized rock, nothing more,” H.O. explained.

“Trust your cloud and don’t try to steer yourself,” Jaydie advised.

“Entering the dust ring now,” West Alia said.

The dust ring was the most dangerous slice of any Stroid belt, and where many solo barclouders had lost their lives. It was safer in a trio, because the momentum of the extra bodies created a slight field that acted as a dust shield, keeping the tiny particles from interfering with the barcloud sensors. Jaydie, H.O., and West Alia sliced through the dust in close formation, swaying left and right around rocks that flitted past them like brown blurs.

“Sight contact on Craxis L,” Jaydie said suddenly.

“Evening out velocity,” West Alia announced.

“Bracing for landing,” Jaydie said.

“Wait what are the specs on this landing?” H.O. asked. “Should I be ready for 3Gs or… oh… owww…” He crashed noisily through layers of leafy trees, landing on his palms in a dirty swamp, ploughing through the mud and flipping over onto his back. “Ohhh… that was at least 5.”

Jaydie and West Alia glided smoothly down next to him.

“Too bad we didn’t need dirt samples,” West Alia said.

“Consider it camo,” H.O. said.

Jaydie glanced at the sensor numbers on the inside of her visor. “This planet’s got good air levels,” she said, flipping the helmet open and taking a deep breath. “It’s been too long.” She glanced from the swampy rice lands in front of her to the denser forest behind.

“Nice plant cover too,” West Alia said, taking off her helmet and tossing it on the ground next to her case. “Good balance between the big oxygen producers and this rice. Loads of water in this moist soil. This planet must be worth a million.” She brought out a core sampler and deftly screwed its three parts together.

“What I wanna know is why Aegis wouldn’t come in here,” Jaydie said.

“Maybe it really is the ionic barium,” H.O. said, switching his scanner on and starting to analyze threats.

“Maybe there are gators like on Parute,” West Alia suggested. Her drill was biting through the nearest tree, a tall umbrageous jungle dweller. In a minute she retrieved a long, pencil thin sample of wood. She stared at it.

Jaydie froze. “What? What is it? Is it infected? Does it have a venom vein? Is it an atmosphere pollutant? What is it West?! How are we gonna die?!?!”

“No it’s nothing. Just counting the rings. She’s 18 years old. Big for her age.”

Jaydie blew a stream of air through her lips. “Biologists,” she breathed.

“Jaydie! I found something!” H.O. shouted from where he stood ten meters away, knee-deep in slimy water.

“What is it, a dead rabbit?”

“No man, it’s a human skull.”

“What?!?!”

“It’s been cracked in two,” H.O. said, wading back to the edge. “It had a metal eye socket implant. That’s what my scanner picked up,” he said.

“Isn’t it weird to find a human skull with an eye implant on a rice planet?” Jaydie asked.

“Yeah it is, isn’t it? Makes you wonder what kind of unusual biological activity we’re talking about. Oh well, none of our business.”

“How is it none of our business?”

“We’re just here to get plant samples, right? Cracked skulls are irrelevant. I wonder how this one happened. Did he split his skull first, or was that a post-mortem accident? What’dya think?”

West Alia’s drill was buzzing through another sample and she held up a hand for silence. “Shut up, H.O.”

“I’m going by Soldier 12 for this job,” he said, tossing the skull recklessly behind him.

“Soldier 12?” Jaydie asked. “Aren’t you the only one?”

“Yeah. That’s how I got to pick my number.”

“Shut up, Soldier 12,” West Alia said, drawing her hand sharply across her neck. She switched off the drill. “Listen!”

From somewhere in the wetlands came vague sounds of popping bubbles. Plop! Plop! Ssssuck!

H.O. shrugged. “That’s nothing. I was on a planet once with bubbles the size of spaceships. I went through on a hover board. Pricked ‘em like I was deflating balloons. I needed so many kinds of showers after that.”

West Alia tore off her glove and laid her bare hand on the ground.

“What is it?” Jaydie asked. “After the 18 year old tree I don’t wanna panic prematurely but… what is it?”

“It’s… vibrating,” West Alia said, her eyes glinting.

“Which means?”

“Something’s coming. Something’s coming through the swamp,” she said.

“More like… the swamp is coming,” H.O. said, stumbling backwards and pointing to a seething mass rising from the water’s edge only feet from them.

“What in the…”

West Alia snapped her instrument case shut and jumped to her feet. “Run!”

H.O. unslung his plasma blaster and took a shot at the rising shape of lichen covered matter forming at the edge of the wetland. His blast ricocheted harmlessly from the monster.

“Man,” H.O. said, turning tail and running after West Alia and Jaydie. “What is that thing?” he shouted.

“Unusual biological activity,” Jaydie panted, brushing through the undergrowth.

“It’s fungi,” West Alia said.

“It’s so big,” H.O. gasped, jumping sideways as a tree the beast hit fell in his direction.

“Try your lasers on it!” Jaydie exclaimed.

H.O. yanked a laser pistol from his pocket and trained it on the fungi. “How’s this for size?” he shouted, slicing right through the center of the rock and dirt and lichen.

“You just doubled the fungi beats,” West Alia said.

“But they’re half the size!” H.O. gasped.

“Okay, plan B!” Jaydie pointed through the trees. “Every Krancore planet has an emergency bunker. There’s ours.”

“I hope you know the entrance code,” West Alia panted, reaching the door and shaking it.

“I know all the entrance codes,” Jaydie said, hesitating at the lock panel.

“Well!”

“I just don’t remember which is which.”

“Hurry!” H.O. yelled, bursting through the trees with four separate quarters of the beast closing in behind him.

West Alia pushed Jaydie aside and swiped 234. The lock clicked and spun and the door yielded to her push.

Jaydie jumped in and H.O. tumbled over her. West Alia pulled him out of the opening, slammed the door shut, and punched the lock key. “You’re welcome,” she said.

“What in the Milky Way is that thing?” H.O. gasped.

“Fungi possessed rock?” Jaydie guessed.

West Alia crossed the room to the bunker computers and dropped into a rolling chair. “That’s a biological impossibility. Fungi possession needs a live host.”

“What is it then?” Jaydie asked.

“Whatever it is, it doesn’t like us,” H.O. said, cringing as the bunker vibrated with the blows of the beast’s fist.

West Alia threw her instrument case open and pulled out a recent sample. “There’s something here that’s acting like a live host for that fungi. How long before this place cracks, Jaydie?” she asked.

Jaydie looked up from the defense control panel by the door. “The shield’s been damaged. We’ll be doing good to get three more minutes out of it.”

“It’ll take me five just to isolate the problem,” West Alia snapped.

“I guess this is why Aegis wouldn’t come in here,” H.O. said, biting into a chocolate bar he’d found in the emergency food stash.

West Alia jumped from her seat. “Aegis uses triphosphate sildoran to harden soil for rock beds! I should have known.”

“What?”

“It’ll host possessive fungi like the one outside.” She drummed her fingers on the bunker wall, then started scrambling through her case. “At least we isolated the problem.”

“On the contrary, it’s breaking in to join us,” Jaydie said, jumping out of the way of a loosened chunk of cement that dropped from the roof.

“Keep it out a minute more, will you? H.O., your blaster. Soldier 12, whatever. Give me your blaster!”

Jaydie flipped the wall panel in front of the shield generator open and yanked at the wires, trying to coax a little more life out of the damaged mechanism.

“I need a reagent,” West Alia exclaimed.

H.O. took another bite of his chocolate bar.

“Give me that!”

“Hey!”

“Give me the chocolate!”

“West! H.O.!” Jaydie shouted. “This beast’ll be in here any minute, get your act together!”

H.O. let go and West Alia tore off the wrapper. She crushed the chocolate in her fist and crammed it into the barrel of H.O.’s plasma gun.

“That’s gonna be so bad to clean out,” H.O. growled.

“The shield’s down!” Jaydie yelled, and the next instant the bunker was filled with a grating sound of stone against stone as the fungi beast crushed the far corner to powder.

West Alia slung the gun to her shoulder and let fly, blasting out a wild dose of chocolate plasma.

The beast reared full height, towering for a second over the bunker. Then it fell apart, raining in a shower of slimy pebbles.

H.O. grabbed his gun back. “Are we done here?” he demanded.

“Another day, another Aegis disaster cleaned up,” Jaydie said. “Figuratively speaking, I’d say the Wayland Terraformers have finished this job.”

H.O. slung the blaster back over his speedsuit and snapped his visor shut.

“Hold on, you’ll have to wait for me to retake my samples,” West Alia said. “I blasted all the first ones at that beast.”

“Did you just… blast it with… everything?” Jaydie asked.

“Mm-hm.”

“And that worked?”

“Of course it worked,” said West Alia. “A little bit of everything always works.”

Enjoyed the story? You might also have fun reading these other stories of mine:

Malcolm DefrosterPrating PiratesA Ghost, a Graveyard, and a GirlfriendThe Master Gunner’s RevengeChasing TroodonFebruary 10, 2022

Book Review: An Old-Fashioned Girl (by Louisa May Alcott)

Polly the country girl is off on a visit to her city friend Fanny—and Fanny’s rich, somewhat dissipated lifestyle throws several perplexing challenges in Polly’s way. How will Polly do walking the tightrope between sticking stubbornly out like a sore thumb and letting worldly wisdom spoil her?

An Old-Fashioned Girl isn’t a long book—shorter than Anne of Green Gables, around the length of The Railway Children or The Scarlet Pimpernel.

The book is written for a young girl audience—it’s probably aimed at 10+ but a younger audience might enjoy hearing it read too. It’s thoughtful enough that older readers may also find it interesting.

As usual, jump to the end if you just want a brief conclusion, or go straight through for all the details!

The Plot [spoiler alert!]

An Old-Fashioned Girl was written in two parts, so the first third covers country-bred Polly Milton’s first visit to her city friend, Fanny Shaw, while the next two-thirds take place six years later, when Polly returns to the city to be a music teacher. The two flow pretty seamlessly and overall the plot is decidedly a romance; but of course the first section does nothing but almost unintentionally set the stage.

The plot of the first section revolves mostly around Polly winning the esteem and liking of the Shaw family and influencing them for good by her wholesome, simple kindness and glad-heartedness. That sounds rather dull but it’s not, for Polly is no impossible angel and her adventures are both realistic and full of humor. This section also sets the stage for the romance to follow, as Polly meets not only the Shaws—Fanny, her younger brother Tom, and her youngest sister Maud—but also friends of the family, including Arthur Sydney and Fanny’s friends Isabelle “Belle” and Beatrix “Trix.”

I could describe some of the thoroughly enjoyable scrapes and adventures Polly and the Shaws have during this first part of the book, but they aren’t deeply influential to the main plot, other than setting the scene by introducing the cast, so I won’t spoil them. Instead, we’ll jump right into Polly’s career as a music teacher. Tom, now grown up and in college, is engaged to Trix—an engagement that none of his family take very seriously, for Trix is a notorious jilter. But just before Tom, Trix got jilted herself, and played that card for all it was worth—“did the forsaken very prettily,” to use Fanny’s words—and Tom, out of pity, lost his head and proposed to her. Meanwhile Fanny has grown into a fashionable, bored young woman, discontented with her life but not energetic enough to try any tough cures. Maud has significantly improved from her old spoiled brat self, however.

As for Arthur Sydney, he’s the same gentleman he’s always been—and he begins to find that Polly has grown from an agreeable girl to an attractive woman. Polly is inevitably flattered by his preference, but, upon reflection, finds that for whatever inexplicable reason proper, sensible, gentlemanly Arthur Sydney stands no chance when compared to Tom the scapegrace. And when Fanny unintentionally reveals that at least half her growing discontent in life is due to disappointment over Sydney, Polly’s half-formed resolve crystalizes, and she decides to make it clear to Sydney that she’ll never marry him. This she does more effectively than may have been expected, unwittingly revealing that Tom is the reason Sydney stands no chance.

But of course, Tom is still engaged to Trix. Polly can’t take this seriously, since no one else does, but it still causes her some uneasiness. And when Mr. Shaw’s business fails, and Tom comes home from college expelled (due to his numerous scrapes) and in debt, and Trix still doesn’t dump him, Polly begins to despair. But her friends’ misfortune gives her other things to think of—and even more importantly, it gives Fanny other things to think of, as she is now forced to take charge of a move into a smaller house and oversee a much reduced complement of servants. These tasks fall on Fanny because her mother, always a bit of an invalid, is incapable of making the effort.

But Mrs. Shaw serves one useful purpose—she gives Tom something to do. That young man having nothing but debts and disgrace to his name so far, is pretty miserable, but he finds occupation in attending to his mother, a service which keeps him out of mischief. Once he overcomes his initial despair and guilt, Tom decides that he must face the world for himself. He resolves to join one of Polly’s brothers out west and try to make his fortune.

Shortly before leaving, Tom receives two letters—one from Trix, and one from Arthur Sydney. Trix has finally dumped him—but more surprisingly, Arthur has paid all his college debts and is ready to give Tom all the time Tom needs to repay him. Tom rather suspects Polly to be the bottom reason for this—and maybe she is, but not the way Tom thinks. Still, Tom is humble enough to decide that Polly would be much better off marrying Sydney than marrying him—and so he leaves.

It takes a year or so in time for the story to wind down, but in events there’s not much to tell. Fanny has been improving at a great rate—doing something was just what she needed—and Sydney, always a firm friend of the Shaw family, begins to admire and finally love her. And although Tom scares Polly dreadfully about a certain Maria Bailey out west, it turns out that it’s Polly’s brother who’s interested in Maria—so when Tom comes back and hears of his sister’s engagement to Sydney, he loses no time in proposing to Polly.

There’s nothing particularly unpredictable about this plot, but the twist with Sydney in love with Polly and then her going out of her way to tell him he’s wasting his time is kind of unique. But the part that impresses me most is the brilliant way Alcott manages to make the hero, Tom, engaged to the wrong girl without ruining him as a character—in fact, making him all the more lovable. It’s Tom’s good nature that made him propose to Trix—a bit of hilarious stupidity that’s perfectly in character—and that same good nature keeps him engaged to her despite her obviously shallow character. As a rule I’m not a fan of triangles, but the Tom-Trix-Polly triangle is one I actually like.

On the other hand, the attempt to make a triangle out of Tom, Maria, and Polly felt a little forced. Sydney was also a pretty flat character—personally I don’t wonder that Polly preferred Tom, he had much more spice to him—and especially in the second half of the book, I felt that Alcott didn’t do as good a job as she could have with some of her secondary characters, who often seemed to be introduced purely for the sake of some moral, without advancing the plot at all.

Still, with a heroine as likeable as Polly and a hero as fun as Tom, I can’t be too hard on An Old-Fashioned Girl and will give it a score of:

7/10

The Point

An Old-Fashioned Girl’s principal moral has two sides—one is a critique of fashionable life and its rules, “which drill the character out of girls till they are as much alike as pins in a paper, and have about as much true sense and sentiment in their little heads.” On its flip side, this means an appreciation for old fashioned virtues of courtesy, hard work, and humility. Fanny Shaw grows out of modeling the former (some of her friends take it to farther extremes), Polly successfully models the latter.

This moral is more specific and complete in the first part of the book—the second section, six years later, takes the story and spins it out farther but only incidentally continues the moral. To compensate for that, the second half features several side morals—not to say side rants—of its own. A lot of these side morals felt tacked on to me; Alcott introduces, just for their moral value, otherwise irrelevant characters who did virtually nothing to advance the plot. This is okay, and Alcott does it more tastefully than many authors, but a moral is always more memorable, more impactful, and less likely to be resented, if it’s smoothly intertwined with the plot.

For the most part I thought the moral reflections throughout the book were good. Alcott’s ideal woman is perhaps the part I have most trouble with, not so much for the concept as for the somewhat mystical thought that women who live lives as close to the ideal as they can somehow help bring the ideal to life at some future time—a thought that smacks of the blind 18th century faith in progress.

7/10

The Style

Alcott’s style is always pleasant to read—it’s friendly, occasionally breaks the fourth wall, and moves smoothly between scenes and characters. There’s nothing especially distinctive about it to set it apart, but it’s livened throughout by touches of humor and Alcott does a good job too (at least in An Old-Fashioned Girl) of not sounding very preachy even when she is essentially preaching.

7/10

Conclusion

7/10

My favorite thing about An Old-Fashioned Girl is hands down its characters—Polly, Tom, and Maud in particular are super fun and realistic. The book emphasizes the “old-fashioned” virtues of humility, hard work, and courtesy in a pleasant way; it’s an enjoyable read and well worth a few hours of reading time!

You can find an ebook version of An Old-Fashioned Girl on Project Gutenberg: https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/2787

If you found this book review helpful, you might also want to check out:

Book Review: The Circuit Rider (by Edward Eggleston)Book Review: Cranford (by Elizabeth Gaskell)Book Review: Three Men in a Boat (by Jerome K. Jerome)Book Review: A Little Princess (by Frances Burnett)Book Review: What Katy Did (by Susan Coolidge)Book Review: Lorna Doone (by R. D. Blackmore)February 3, 2022

Book Review: Little Dorrit (by Charles Dickens)

Born and raised in a debtor’s prison, with a broken father, a haughty sister, and a thoughtless brother, Amy Dorrit’s patient, gentle character is still able to find happiness in serving others. But when her father inherits a vast estate and is suddenly freed, her old life is relentlessly swept away—the old friendships and simple pleasures as well as the old hardships and trials. How will Amy cope with the wealth that instantly spoils the rest of her family?

Little Dorrit is no afternoon read—it’s long, rivalling Bleak House, War and Peace, or The Count of Monte Cristo.

Given its length and Dickens’ literary writing style, Little Dorrit would be hard for younger readers to wade through, but readers 15+ would likely enjoy the book. Readers is a key word though—if you don’t like reading much, Little Dorrit is not the book for you!

Jump straight to the bottom to avoid spoilers and catch my brief conclusion along with a link to the ebook, or read on through for the details!

The Plot [spoiler alert!]

In typical Dickens fashion, Little Dorrit has a host of characters, far too many for an outline! I’ll start with the title character and see who demands a place in a summarized story of her life.

Amy Dorrit is born in an English debtor’s prison—not only born there; she’s lived there all her life. Her father, not a very money-wise man, got in debt shortly before her birth and has stayed in debt ever since. But although Amy’s older brother Edward (Tip) and her sister Fanny have grown up with a sense of injustice and a determination to get what they can from the world while looking down at it from over their noses, Amy is humble, hardworking, and generous.

Amy helped Fanny get a job at a dancing hall where the sisters’ uncle works, and she’s tried many times to help Tip to a job—but Tip doesn’t stick with anything. On her own account, Amy is a seamstress—and among her clients is Mrs. Clennam.

Mrs. Clennam is a paralyzed invalid, head of a commercial house in a small-wealthy way. Her husband worked and died in China—and now that his father is dead, Arthur Clennam is coming home.

But home isn’t very homelike to Arthur—with his mother’s rigid, unsympathetic figure to welcome him and with the consciousness that his decision to leave the family business will not be favorably received. Under the circumstances, the friendship he makes on the trip back to England with Mr. and Mrs. Meagles—and with their beautiful daughter Minnie—is a welcome relief.

Sure enough, Mrs. Clennam gives Arthur the cold shoulder when she learns that he has decided to leave the business. Although he begs her to still confide in him and let him help her—Arthur, based on some words of his father, suspects some particular secret, some case when perhaps the Clennam business did a monetary wrong and never made reparation—Mrs. Clennam refuses to let him know any details.

Arthur, trying to figure out what his father’s mysterious words meant, notices Amy Dorrit and wonders why his mother hires her; it seems out of character. He discovers where she lives and worries that his mother might have had something to do with Mr. Dorrit’s imprisonment. Through an unintentional combination of circumstances he sets Mr. Pancks, a workaholic with a constant eye to putting this and that odd scrap of information together, to work trying to decipher the ins and outs of Mr. Dorrit’s case.

In the process, Mr. Pancks discovers a vast property to which Mr. Dorrit—the imprisoned debtor!—is of all people the rightful heir. He follows out his discovery and it leads to Mr. Dorrit not only leaving the debtor’s prison, but being elevated suddenly to a position of significant wealth.

At first this has a bewildering effect on Mr. Dorrit personally. But he resolves to rise to his new position—and unfortunately, to him that means forgetting, and doing his best to make others forget, everything about his past. Everything—literally everything, the good as well as the bad, lessons that should have been learned as well as the hardships that are well over. But Amy cannot forget, or want to forget, the many good things of her early life, nor the lessons of caring friendliness that it taught her. Still less can she forget Arthur Clennam and his kindness. While the rest of the family struts around in the highest levels of society, trying to pretend that they’ve always been there, Amy feels a little lost.

The Dorrits’ first act was to “go abroad,” and there Fanny renews the acquaintance of a brainless but in the main good-hearted youth who had first admired her as a dancer. This youth is the step-son of the “man of the age,” Mr. Merdle, a rather dull and unsocial man himself, but immensely wealthy and head of a multitude of enterprises. Mrs. Merdle remembers Fanny distinctly from the days when she bribed her to ignore her son’s attentions when she was a dancer, and knows perfectly well that Fanny would make the most tormenting daughter-in-law that ever was. Fanny doesn’t care much for Edmund (this is the step-son’s name), but the idea of torturing Mrs. Merdle appeals to her intensely. To Amy’s dismay, she accepts Edmund’s proposal just before Edmund returns to England to accept a position in the Circumlocution Office that Mr. Merdle, at the instigation of his wife desperate to rush Edmund away from Fanny, has obtained for him.

I flatter myself that was a fittingly roundabout way to introduce the Circumlocution Office; now I’ll have to pause and explain what it is. This is the place where “How Not To Do It” has been reduced to a science, where even the most important and urgent business can be buried under years’ worth of paperwork. In short, this is Dickens’ satire on bureaucracy, and he draws it out pretty strong—though not too strong, by any means.

By the by, another person the Dorrits meet abroad is (of all people) Minnie. I don’t expect you to remember her, but if you were to happen to scroll up you’d notice that I hinted that Arthur Clennam enjoyed her society. However, though Minnie doesn’t dislike Arthur, she happened to be already in love with one Mr. Gowan (a rather worthless young artist, remotely related to the Barnacles, head family of the Circumlocution Office). The long and short of it is that by the time Amy makes Minnie’s acquaintance she’s Mrs. Gowan, and Arthur has had to bear his disappointment as best he might—with Amy’s sympathy, though not exactly with her regret.

Amy and Minnie become good friends, but other than that, Amy finds little to enjoy in her new life and a good deal to alarm her. Fanny’s marriage could certainly be worse, but it doesn’t promise to be an especially happy one, Tip is rather on the dissipated end of things, and her father rejects everything that looks like a return to the old days—hinting to Amy that he’s very pleased with her sister’s match and hopes she will make an equally advantageous one. More than that, Mr. Dorrit is evidently himself falling into the clutches of the widowed Mrs. General, engaged as travelling companion for Fanny and Amy, but fast worming her way into a more permanent position. He takes a trip to London to see Fanny and Edmund settled and returns with every intention of proposing to Mrs. General.

But Mr. Dorrit has reckoned without his age. Shortly after returning, he attends a party thrown by Mrs. Merdle, where he totally forgets where he is and makes a spectacle of himself, addressing the company with one of his old debtors’ prison speeches. Amy—no more ashamed of him now than then—helps him home and watches over his last hours.

Mr. Dorrit’s death is of little enough concern to anyone but Amy—but another death happens about this time that has far greater repercussions. Mr. Merdle, the wealthy capitalist, commits suicide. And the reason he does so is that his schemes were all a fraud and are now collapsing, to the ruin of millions of duped investors.

Among those now ruined is Arthur. He feels especially bad for his partner (currently working in another country), who had trusted him with the management of the finances of his company. Arthur pays as much of his debts as he can and goes to the debtors’ prison—the same prison that had been Mr. Dorrit’s home for so many years.

Here we’ll have to step back a moment to recall the old suspicions Arthur had about his mother. It turns out that he was right to smell a rat when he caught his mother being nice to Amy Dorrit. In fact, Mrs. Clennam had long ago suppressed a will made by her father-in-law in Amy Dorrit’s favor. The wherefore of this is complex, but basically; Arthur’s mother (Mrs. Clennam) is not actually his mother—Mr. Clennam, Arthur’s father was already secretly (and presumably not altogether legally) married to another woman when Mrs. Clennam married him. This was unknown to Mrs. Clennam (of course) and Mr. Clennam, in terror of his father, was not willing to risk exposure; he sent his first wife away. But she was already pregnant with Arthur. Mrs. Clennam was furious when she learned of it all, but she struck out a compromise whereby Arthur would stay with his father and herself on condition of never seeing his biological mother again. Said biological mother got decidedly the short end of the stick for a situation which was far more her misfortune than her fault—and eventually Arthur’s father relented of his part in the story and tried to benefit her. But she was already dead—and the best thing he found to do was to bequeath a small fortune to the youngest daughter of her kind landlord. That kind landlord just so happened to be Mr. Dorrit’s brother—and he just so happened to not have children. So the small fortune reverted to Amy.

But, Mrs. Clennam does not want the story to get out, so she suppresses the will, never tells Arthur that he’s not her child, and squares matters with her conscience by hiring Amy as a seamstress. To do her justice, she didn’t know how poor Amy actually was.

So why bring up this family skeleton now? Well, it turns out that a notorious brigand has got his fingers on the suppressed will, and blackmail is the name of his game. Mrs. Clennam at first doesn’t believe that he has the will, but eventually her partner in business admits that he didn’t destroy the will when Mrs. Clennam told him to. Long story short, the brigand has deposited a sealed copy of his knowledge with Amy Dorrit.

Which requires a bit of explanation, so here’s a not-so-quick digression: Arthur Clennam is in prison, right, and there he discovered what an idiot he was for not having married Amy a long time ago. I’ve done a bad job so far of keeping tabs on Amy’s love story, but basically she’s loved Arthur ever since she got to know him, but Arthur always thought of himself as twice as old as her (which he was) and in love with Minnie (which, maybe, he also was), and, in short, was an idiot after the most approved fashion. Besides the idiot thing, Arthur’s character, although upright and brave enough in a passive way, is not very sturdy or actively courageous—he’s more of a dreamer. Stuck in his narrow prison with very little hope of ever coming out, he goes into a decline and becomes sick.

Meanwhile Amy has returned to England after her father’s death. She finds Arthur and takes care of him through his sickness. So that’s why the brigand deposits a copy with her—and he gives her instructions to give it to Arthur at a certain time if he hasn’t personally reclaimed it by then.

So, back to Mrs. Clennam. Learning from the brigand of the exposure impending if she fails to pay his blackmail, she takes a bold step. Although she’s been an invalid for years, she manages to get up, leave her house, and walk to the debtors’ prison where she rightly expects to find Amy. Amy would have given her the copy, but in a surprising turn of events, Mrs. Clennam tells Amy to open and read it. She asks (and of course receives) Amy’s forgiveness. The two return to the house together, only to find it in the act of tumbling to the ground as long years of disrepair catch up to it. The brigand is conveniently buried in the ruins, Mrs. Clennam returns to her invalid state, and Amy chooses not to tell Arthur the story.

For the rest, Arthur tells Amy he could never marry her, because he’s so poor and she’s so rich, but turns out Amy’s father had invested all their money with Mr. Merdle, so she’s not so rich—and Arthur’s business partner returns from an overseas business venture that went extremely well, so Arthur’s not poor either. And so they marry, and live happily ever after.

Fanny, on the other hand, is not half as pleased to find that she’s broke as Amy was—but she consoles herself with the fact that Mrs. Merdle is now totally dependent upon her charity. Edmund’s job in the Circumlocution office is plenty for their needs, if not for their wants. So they too do well enough.

I admire the plot of Little Dorrit very much; it’s thoroughly cohesive and also sufficiently unpredictable—though not in a cliff-hanging way. It wraps up very well and very satisfactorily.

Amy is an admirable character, though a touch more spirit could have improved her—and I even like her sister Fanny in a way. Many of the secondary characters that I haven’t mentioned or just briefly touched were great in their own ways—Mr. Pancks, Flora Casby, Cavalleto, and Mr. and Mrs. Meagles especially. On the other hand Arthur is not exciting by any stretch of the imagination and is occasionally a bit pathetic—not more than a “good enough” character.

One other character I want to mention is Miss Wade. She intersects with the plot at various points, in the character of an old lover of Mr. Gowan’s, a contact of the brigand’s, and so forth. Miss Wade is the exact opposite of Amy—she puts the worst possible construction on everybody’s motives. While I think the idea of including a total contrast character in a novel like this is an intriguing one from a literary point of view, it strikes me as something that ought to be done very subtly—otherwise it doesn’t feel natural. Miss Wade doesn’t feel natural at all to me.

To sum up, the plot of Little Dorrit is incredibly complex yet impressively resolved. Although I felt that some of the characters—including the main ones—were a little lacking, there were lots of great secondary characters to make up for that. I give it:

9/10

The Point

One of the points of Little Dorrit is a critique of government bureaucracy. I appreciate the way this critique fits naturally into the book, with the Circumlocution Office and its official tardiness having a large role to play in the developing plot. Dickens does a good job pointing out the absurdity of bureaucratic protocol. With minor changes, this point is just as relevant today as it was in his time—if not more so.

The other point of the book—and the more central point—is an analysis of the right uses of wealth—or rather, of the wrong uses of wealth. The biggest example is the Dorrits themselves, who gripe all their days (with the exception of Amy, of course) over not being wealthy, and then are completely unable to get true happiness out of it when it comes. Mr. Merdle, too, risks and ultimately loses everything he has for wealth, and gets no happiness out of it. Arthur and Amy, with their more correct perspective on wealth, are far happier even when in poor circumstances, content with what little they have and happy whenever they can be of service to others.

With the huge contrast between the Dorrits before and after they became wealthy (a contrast that divides the book into two sections), a clear moral emerges: happiness does not depend on riches.

Besides this, there is also a lot of emphasis on Mrs. Clennam’s hypocrisy—while she prides herself on being upright and an instrument of judgment (against Arthur’s father), in reality she has only done what her own vindictive spirit prompted her to do. There’s a great contrast between this and Arthur’s forgiving, gentle disposition. I’ve been trying to find a way to connect this somehow with the previous moral, but they don’t seem to intersect. As a reader who likes to see the main moral of a book weave its tendrils into every little corner in unsuspectedly clever ways, I’m a bit disappointed that I can’t see that here.

I would be remiss if I did not also mention a motif that shows up throughout Little Dorrit: travelers through life moving to meet and act and react upon each other. This introduces a bit of a sense of flux, of constant motion, and in this motion—in the wheels that turn and make the Dorrits first poor, then rich—that make the Merdles first rich, then poor—that grant Mrs. Clennam her vengeance, then turn it upon her own head—in this state of flux, finding something solid to inform a wise and happy life means turning away from the bustling of human affairs (particularly money affairs) and finding some quiet way of helpfulness, finding a way to love and be loved. This could be paradoxically expressed as recognizing the unreality of reality and instead practicing the impractical dreams of love and nobleness in the highest sense. I say all that very glibly, but this is more my interpretation of a slight feeling the motif left me with, rather than anything explicit or even implicit in the book.

To summarize: Little Dorrit is a great critique of bureaucracy and also a vivid illustration of the futility of wealth. The moral regarding wealth is not integrated as clearly with other morals of the book (such as a condemnation of Mrs. Clennam’s hypocrisy or the traveler motif) as I would have liked; but it is certainly a great moral and is powerfully shown through the rising and fallings of the Dorrit family’s fortune.

7/10

The Style

I’ve described Dickens’ style plenty of times (see links below), so I won’t go into much depth here—but I did enjoy the unusual but highly realistic style Dickens’ used for Flora Casby’s dialogue in Little Dorrit—and there were several other characters with their own unique way of speaking, making the personality filled dialogues of Little Dorrit really shine.

For the rest, you’ll have to give Dickens your full attention if you expect to understand him, but his unique turn of phrase and wide vocabulary will definitely reward you.

I notice that I habitually give Dickens’ style 7/10—except when I want to bring down the overall score a notch but can’t bring myself to lower the score on plot or point. This is one of those times, so:

6/10

Conclusion

7.3/10

Little Dorrit is one of those books that I wish I liked better than I do. The plot is brilliant and exciting, the main points—especially the truth that happiness does not depend on wealth—are very good, and Dickens’ style is intriguing as always. But for me Little Dorrit just doesn’t cut it with the main characters—while I like Amy Dorrit, she’s not quite as awesome as she should be, and Arthur is even less inspiring. That said, I certainly recommend reading the book, though it’ll take a lot more than one rainy afternoon or even a rainy week to get through it—maybe a whole rainy month!

You can find Little Dorrit for free as an ebook on Project Gutenberg: https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/963

Already read Little Dorrit and have opinions of your own to share? Let me know what you think in the comment section below!

You might also enjoy these other book reviews:

Book Review: Hard Times (by Charles Dickens)Book Review: Our Mutual Friend (by Charles Dickens)Book Review: Bleak House (by Charles Dickens)Book Review: Dombey and Son (by Charles Dickens)Book Review: The Picture of Dorian Gray (by Oscar Wilde)Book Review: Jane Eyre (by Charlotte Bronte)Book Review: Cranford (by Elizabeth Gaskell)Book Review: Emma (by Jane Austen)January 27, 2022

Book Review: The Circuit Rider (by Edward Eggleston)

Set in a bygone era of second generation pioneers, The Circuit Rider commemorates a little remembered group of heroic men—early Methodist preachers who gave up comfort, convenience, and sometimes even their lives in order to ride their preaching circuits and establish their church on the very borders of civilization.

The Circuit Rider is not a very long book—it’s around the length of Anne of Green Gables or Northanger Abbey. I’m having a bit of trouble estimating its age range—the plot is not super complex and might be interesting to some young readers, but it’s historical side and just Eggleston’s writing tone in general is aimed for a slightly older audience, say 15+.

You can jump straight to the end if you’d like to read my brief conclusion on the book and find a link to the ebook—or read on through for all the details!

The Plot [spoiler alert!]

It’s hard to know how much of the plot of The Circuit Rider needs to be included in a summary in order to do the book justice. At its core it’s a romance set in frontier Ohio in the days of the early Methodist revivals. Morton Goodwin, a somewhat wild and rather poor young man, has always loved Patty Lumsden, the daughter of one of the wealthiest landowners in the settlement and a remote connection of the “old Virginia” families. Patty is rather partial to Morton herself, but her father certainly isn’t. However, Morton is popular enough among the settlers that Captain Lumsden (a proud and ruthless man) decides to be nice long enough to secure his influence in an upcoming election. This gives Morton some hope… but it also puts pressure on him to take Captain Lumsden’s side, not just in the election, but also in his anti-Methodist sentiments—and even worse, in his feud with his feisty nephew Hezekiah “Kike.”

When Captain Lumsden threatens to take advantage of legal technicalities and sell some of Kike’s land, Morton’s sympathies are all on Kike’s side, but he hardly dares to risk Captain Lumsden’s anger. Then when to top that off Kike becomes a Methodist, repenting of his fury towards his uncle, Morton is torn—wanting to be anti-Methodist and stay on Captain Lumsden and Patty’s good side, but feeling like a coward as Kike braves sneers and physical hardships in order to become a Methodist pastor. (Captain Lumsden’s brand of anti-Methodism, be it mentioned, is rather violent—and while Morton is plenty willing to mock and disturb meetings by noise and revelry, he disapproves of the Captain’s more brutal method of beating up the pastor.) Caught between these cross fires, Morton goes a little wild, gambles away everything he has, nearly commits suicide, and even almost gets lynched. But after being rescued from that fate, and now on his way back home, he lodges at a house where a Methodist meeting is being held. Already pretty well convinced of his sinfulness and need for a changed heart, he becomes converted under the preaching and resolves to do right—which includes boldly avowing his new faith, though it will certainly cost him Captain Lumsden’s favor, and probably Patty’s as well. For Patty, though not irreligious in her father’s way, looks down on Methodism as vulgar and fanatical.

So when Morton avows his Methodism, Patty orders him to abandon it. Seeing how powerfully this affects him, she is sure a little sternness on her part will be effectual. But in this she is wrong. Morton, though devastated, stands by his new convictions and leaves.

Leaves to join Kike in becoming a Methodist pastor—a “circuit rider”, so called because their preaching appointments were arranged by circuits and they traveled by horseback between them. Morton’s bold and courageous bearing gains him a reputation and he eventually gets assigned the district with some of the most troublesome “rowdies.” Besides rowdies, he also makes the acquaintance of the apparently devout Ann Eliza Meacham. Ann Eliza needs help in a lawsuit, and Morton undertakes to give it—finding afterwards with great dismay that everyone now expects him to marry her—herself included. Morton has never overcome his preference for Patty, but he feels bad over breaking Ann Eliza’s heart and is perplexed as to what to do.

Meanwhile back in Morton’s hometown a grand Methodist meeting is being held, and Patty, who has already heard the rumors about Morton’s engagement to Ann Eliza, decides to attend the meeting just to break her monotonous routine. But although she goes determined not to be converted, she changes her mind in the course of the sermon, and as the preacher preached he “won her famished hear to Christ. For such a Master she could live or die; in such a life there was what Patty needed most—a purpose…”

Now a Methodist, Patty is turned out of doors by her father, and goes to make her own living by teaching at a school. Here she is particularly befriended by the doctor of the town, who soon finds her cheerful helpfulness invaluable. Thus it happens that when a suspicious looking wounded character is laid up in another suspicious character’s house, Patty visits every morning to look after him.

Said suspicious character knows a certain something that turns out to be deeply interesting to Patty—namely, he knows of a planned attack on Morton’s life. For reasons yet to be revealed, “Pinkey” (as the suspicious character is known) does not want Morton killed, but he’s still too weak to warn him himself. But of course, Patty is more than willing to brave anything for the sake of warning Morton—which she does. This, as Pinkey later taunts her with, has no doubt earned Morton’s gratitude, and possibly to something more. But Patty promptly quenches him with the information that Morton is by now engaged to Ann Eliza. This information shocks Pinkey, who happens to have known Ann Eliza long ago and knows that she’s playing the hypocrite now—a bit of a self-deceived hypocrite, but hypocrite none the less. He promises to spoil her game. Not long afterwards, he disappears.

Meanwhile Morton, on a visit home, is surprised to learn that his older brother, long since supposed dead, has returned home. Lewis Goodwin had been quite the prodigal son, but like the prodigal son, he finds everyone ready to forgive him. But he’s more than just any prodigal son—in fact, he’s “Pinkey,” highwayman and robber, but also responsible for saving Morton’s life. And, too, he has fulfilled his promise to Patty—he’s extorted a letter from Ann Eliza—on pain of himself telling Morton all he knows about her unflattering past—and in that letter he forced her to break her engagement.

Of course that quickly wraps up the scene as there’s nothing left but for Morton and Patty to be reunited. Incidentally I must mention Kike, who has died sometime past, a sacrifice to his heroic endurance of the hard life of a circuit rider.

All things considered, the plot of The Circuit Rider is not a stunning one, but it’s solid, especially with the twist of Pinkey’s identity. Morton and Patty are both enjoyable if not brilliant characters and despite Kike’s sad death, the story comes to a satisfactory conclusion.

7/10

The Point

Eggleston’s main intention in The Circuit Rider seems to have been to commemorate a calling (for lack of a better word) that he knew well from his own early experience but that had nearly if not quite disappeared by the time he wrote—and is gone almost out of memory by now. I knew what a circuit rider was before I picked up the book—but I expect I’m the exception. Eggleston’s treatment is fair and thoughtful; he’s no blind admirer of early Methodism, but he’s sympathetic to the sincerity and heroism of these preachers. Some of Eggleston’s critiques are particularly insightful—such as, “It seems to have been a favorite delusion of pietism, in all ages, that God could direct an inanimate object, guide a dumb brute, or impress a blind impulse upon the human mind, but could not enlighten or guide the judgment itself.”

Making an understudied corner of history come alive is a worthy goal for any book, and Eggleston does an effective job.

9/10

The Style

Edward Eggleston’s writing style is casual, almost conversational. It’s agreeable and occasionally humorous, without being especially polished or witty. On occasions I think it feels a little slow, but it’s not tedious.

7/10

Conclusion

7/10

With a solid plot and a pleasant style, The Circuit Rider makes for an enjoyable read. Despite being a book about preachers, it’s not preachy—it presents the early Methodist circuit riders from a sympathetic but not partisan point of view. In doing so, the book brings to life a bygone era of heroic pioneers and settlers. I doubt The Circuit Rider is anyone’s favorite ever book—but it’s a great read, particularly if you’re interested in American religious history.

Unfortunately no edited ebook version of The Circuit Rider has been prepared, but you can get a digitalized version at: https://archive.org/details/the-circuit-rider Be warned, there are plenty of errors!

You might also enjoy these other book reviews I’ve written:

Book Review: Cranford (by Elizabeth Gaskell)Book Review: Three Men in a Boat (by Jerome K. Jerome)Book Review: A Little Princess (by Frances Burnett)Book Review: What Katy Did (by Susan Coolidge)Book Review: Lorna Doone (by R. D. Blackmore)January 19, 2022

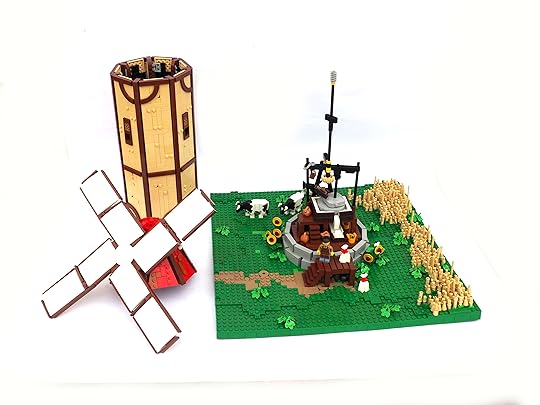

LEGO Windmill

A few weeks ago I was brainstorming for my next LEGO build. I wanted something with some fun motion and lots of gears. A windmill seemed like a good idea: the basic problems of windmill gears were solved hundreds of years ago, so I wouldn’t have to design anything from scratch, but turning that motion into LEGO would still take some trial and error!

Before we get into the internal mechanism, let’s take a look at the outside. This windmill represents one of the later medieval designs. Wind in Europe often changes direction, so it didn’t take Europeans long to figure out that they should make their windmills able to change directions too. At first, mills were square boxes with the sails in the middle of the wall. The whole box could be turned to catch the wind from any angle.

Later on, the sails were moved to the roof, and only the roof was designed to rotate. I chose to copy this design, because it’s more visually appealing.

So I built a tall round tower on a stone foundation, and then the red roof on top, which instead of being attached to the walls is attached to a center axle.

So as you can see in this next picture, the roof can be turned (without removing it) to face anywhere in the sky and make the best use of the breeze!

The gear box that transforms the sail motion from horizontal to vertical is inside the roof. So there’s a short axle coming down from the roof that attaches to the worm gear on top of the inside axle in this next picture. The worm gear (the grey gear on top) is an interesting piece–it’s got a + shaped hole inside, but it has no friction. That worked perfectly in this case–you can slide the roof on and off easily, but still get the traction needed to turn the axle when the roof is on.

The center axle of the windmill reaches down to the largest gear–tan in my mill. This turns a smaller gear which then turns a small grindstone.

Theoretically there’s a little hole in the top grindstone that allows the wheat to drop through and get caught between the two stones. There it gets ground into flour. The flour empties from the box around the grindstones into a lower box, where it can be scooped into sacks!

This creation was designed to be seen inside as well as out, so the roof and walls were built in two sturdy segments that are easy to remove!

Of course, I couldn’t build a functioning windmill and not make a video for it! This video includes a time lapse of the building process where you can see how many tries it took me to get that roof and sails just right!

If you’d like to see this as an actually LEGO set, you can support it on LEGO Ideas!

You might also enjoy these other LEGO creations of mine:

LEGO Fighting PitBuild Log: WaterwheelBuild Log: Classic Pirates FortBuild Log: Seaside FortBuild Log: LEGO Ninjago ScrollBuild Log: Wading PoolBuild Log: Ninjago Legacy LighthouseJapanese Fortress Build LogBehind the Scenes: Space Travel PosterBuild Log: Cherry Blossom FortOctober 29, 2021

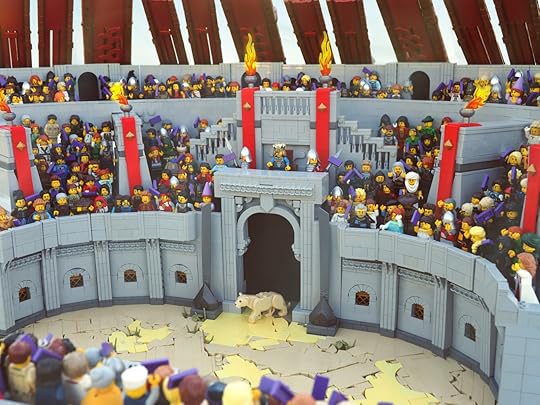

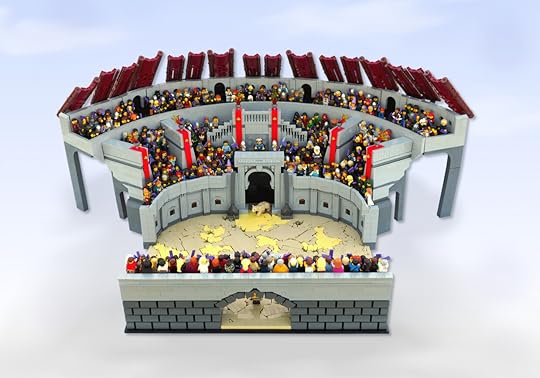

LEGO Fighting Pit

The Summer Joust competition left me wanting to build something really big. So though this creation doesn’t set my record for the largest footprint, it sure does use more minifigures than I’ve ever used before!

I designed this creation to have two different immersive scenes. There’s a lot more to it than just the bit of theater you can see behind the gladiator!

This build took me about five weeks to build, though the first week was mostly just me procrastinating on that tedious desert floor.

I had a terrible time trying to narrow down all the pictures I took of this build. So although there are still more than usual, trust me, there were far more yesterday!

Although a lot of the build is lost in these gladiator shots, I love the way the stone walls frame the theater.

Usually when I build all LEGO scenes there are lots of rough edges. But because I wasn’t quite sure what I was doing when I started, I finished off the edges as I went along.

I had fun taking some pictures in the sunlight.

It was a lot of fun to see this build get bigger and bigger as I added the layers, though it did make it pretty difficult to take outside for the photography session. I ended up rebuilding most of the middle layer where the big crowd is!

This layout was inspired by this piece of concept art.

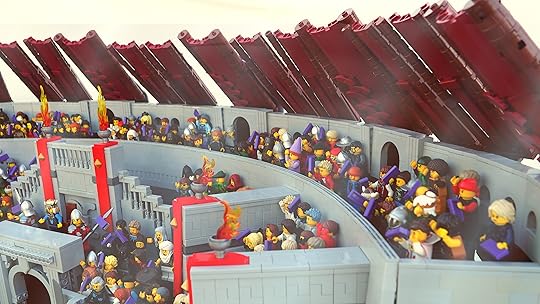

You might have noticed the rows of mixel joints I used as architectural details. I doubt I’ve ever found those joints this useful before!

The dark red awnings were the last thing I added, and I have some mixed feelings about how they turned out. I think they do help finish the pit off, but they’re so gappy! They look better in some pictures than in others.

As I mentioned earlier, I’ve never used this many minifigures in a build before. Basically, I filled the lower stand with all the torsos I had that looked even remotely medieval. Then I went and borrowed all my brothers medieval minifigs for the second stand!

I threw in a bunch of 1×2 purple tiles in order to bring some cohesiveness to the crowd. In theory these are the gladiator’s colors (notice that he’s wearing a purple cape!).

One of my favorite things about this build is the way the red drapes over the pillars looks. Those sections were all very fun to build… not so fun to try to attach at weird angles.

By the time I had finished the last level, I was pretty tired of finding ways to attach each wall in a circle!

I also put together a time lapse video of the build process. I highly recommend watching at least the first forty seconds, it’s got some fun effects!

So there we have the Fighting Pit! My goal with this was to build the Fighting Pit to end all Fighting Pits… how did I do?

You might enjoy these similar posts:

Build Log: WaterwheelBuild Log: Classic Pirates FortBuild Log: Seaside FortBuild Log: LEGO Ninjago ScrollBuild Log: Wading PoolBuild Log: Ninjago Legacy LighthouseJapanese Fortress Build LogBehind the Scenes: Space Travel PosterBuild Log: Cherry Blossom Fort