AE McRoberts's Blog, page 2

September 26, 2022

Bestsellers Code: Anatomy of a Blockbuster Novel Review

Greetings, Padawan!

Today we’re going over one of my favorite books, The Bestsellers Code: Anatomy of a Blockbuster Novel. Let me use animated language to express my love for this book. LOVE SUPER LOVE EXTORDINARY LOVE LOTS OF LOVE. I almost love it as much as I love pancakes. There, now you know how much I loved this how-to book. Me and how-to books usually get along well because I find them interesting and informative.

Usually that is, but I found Hero with a Thousand Faces by Joseph Campbell, and the Writers Journey by Christopher Vogler hard to digest.

I’m never really hesitant to pick up a new how-to book. I enjoy them because they usually teach me so much. Well, Bestsellers Code didn’t disappoint. It was a big bonus that the authors were entertaining. I really enjoyed reading what Jodie Archer and Matthew L. Jockers had to say.

Well, let me get on with what the book is actually about. It’s about stuff. HA! See, there is my humor getting in the way again, bad humor!

The Bestsellers Code describes exactly what it’s about. Basically, Archer and Jockers programmed an AI, (or Artificial Intelligence for those of you under a rock) to read, recognize, and it shifted through twenty thousand books. After years of I’m sure was backbreaking, eye bleeding work analyzing and measuring data, they found patterns in “best selling” books.

You’ve read that right and isn’t that AMAZING!

Here’s an actual-from-the-book-quote: “First, the machine tells us which topics exist in our collection and as part of that, which words compose each topic, such as those words seen in the bar and body topics. Seconds, the machine tells us the proportion of each topic in every book.”

Interesting, right? Well, it gets better.

“It turns out that successful authors consistently give that sweet spot of 30% to just one or two topics. To reach a third of the book, the lesser-selling author uses at least three and often more topics. To get to 40% of the average novel, a bestseller only uses four topics. A non-bestseller, on average, uses six. Telling the heart of the story with fewer topics implies focus. It implies a lack of unneeded subplots. It implies a more organized and precise writerly mind. It implies experience.”

Makes sense, right? Totally.

These guys can tell you exactly why E. L. James or Dan Brown sell so many books. Crazy right! I know, it’s like a mix of voodoo and LSD. They analyze words, and can tell you if your manuscript has the juice to make it a bestseller.

When I get my YA manuscript back from my beta readers, I’m totally submitting it to them. Because like how cool would it be to know I have a bestseller before it’s an actual bestseller!

Well, I’m sure you’re asking, how in the hell can they actually tell? For the complete answer you’ll have to read the book, and I strongly urge you to, because it’s amazing. But, I’ll give you the skinny because why else would I write a post on it? Right, right?

Let’s start this off with some numbers, but don’t worry, there’s no math involved, I hate math. Dan Brown’s novel, Inferno, had a 97.5% chance of being a bestseller. Michael Connelly’s The Lincoln Lawyer had a 99% chance. Spoilers! They were both number one (in hardback) on the NYT (New York Times) bestseller list. JK Rowling came in at 95%, John Grisham was 94%, Patterson was 99%.

I’m sure you’re thinking, duh! They’re both well-known authors, but the AI didn’t know names! It’s only based on the writing itself. Bat shit crazy, right!!

Okay, let’s get into some meat.

The AI identified style as important, and since it’s the mechanism through which plot, theme, and character are presented.

“In the world of fiction publishing, especially as a new writer, it’s not so much who wrote what but how it was written that might change your life. The best writers- or those who will achieve the most readers- are able to establish this kind of presence from the opening sentence with tiny and seemingly effortless modulations in style.”

This is probably why so many authors emphasize developing a unique “voice” for new writers. But, prepare yourself, it’s about to get super interesting.

What’s your opinion on the word do?

I approve. HA!

The word do is twice as likely to appear in a bestseller than a book that doesn’t hit the list. So add that one to your do use. HA! I’m full of it!

Let’s continue. What’s your opinion on “n’t” contractions? I don’t know. Or I shouldn’t tell you. Maybe I couldn’t think of anything else? Yep, all those.

Well, get this! The contraction “n’t” appears FOUR times more often in books that are bestsellers. FOUR TIMES! I’m amazed also.

Here’s another direct quote from the book “Dropping letters, is a good idea in writing popular prose because it helps create that believable, authentic, modern voice that is essential to winning over readers. The narrator’s voice, be it third, or first person, has to stroke readers as real and appropriate if they are going to stay with it.”

It’s beautiful advice.

So want more? I’ll give ‘em. The contraction “-d” is twelve times more common in bestsellers, while “-re” is five times more common, along with “m”.

He’d pass out, they’re going to laugh, and… I can’t think of a “m” contracted word… shit… Ug.

Ug is also common! Yep, super surprising, right?

Okay also appears three times more often in bestsellers.

So let’s start a list. Right now we’ve found ug, okay, do, n’t, d, -re, and m contractions. This is coming together, right? And this is just the beginning.

Here’s my favorite part, characters in bestsellers as more questions. They found more question marks in books that hit the list. But, exclamation marks are a negative indicator for bestsellers. Who woulda guessed! And this is just a post about the book. The actual book is so much more wonderful!

So Let’s get into some nitty-gritty with some details.

“In bestsellers, adjectives and adverbs are less common, particularly adjectives. What this means is that bestsellers are about shorter, cleaner sentences, without unneeded words. Sentences do not need decorating with additional clauses. Their nouns don’t need modifying three times.”

Hence why you edit mercilessly!

Verbs are more common in bestsellers, but they shouldn’t be followed with a string of “really very pretty lovely little words ending in ly. Verbs are key”. Is that legal blending a direct quote like that? Oh well.

Now, regardless if the character was make or female, bestselling protagonist must have and express their needs. The protagonist must want things, and we have to learn about those.

The verbs need and want are the two biggest differentiators between selling and not selling. Which is super awesome. Because that reminds me of a good character arc, and the thing he needs and wants. Familiar?

But it gets better, bestselling novels contain a world in which the characters know, control and display their agency. The verbs they use are clean and self-assured. Characters often grab, do, think, ask, look, and hold. And, get ready for this, they more often love. This doesn’t mean they have to like themselves, but they must own themselves. They live their lives and make things happen.

Isn’t this stuff awesome?

Okay, this next bit, I will list out, since it’s basically a list.

Bestselling characters (male or female), tells, likes, sees, hears, smiles, reaches, pulls, pushes, starts, works, knowns, and arrives.

I’m sure you’re asking what in the hell? I’ll give you an example.

She told him she likes to see the ocean, hear bells, and gave him a smile. Then she reached for the bell and pushed the little button. See? It’s all about the words.

Here is the complete list of popular character verbs: Want, grab, do, think, ask, look, hold, love, eats, nods, opens, closes, says, sleeps, types, watches, turns, runs, shoots, kisses, dies, survives.

Here is a complete list of unpopular verbs: demands, seems, waits, interrupts, shouts, flings, whirls, thrusts, murmur, protest, hesitate, halt, drop, grunts, clutches, peers, gulps, flashes, trembles, clings, jerks, shivers, breaks, fumbles, flings, yawning,

Definitely have little hesitating by the protectionist.

And the lists go on!

Both men and women: spend, walk and pray.

But, male protagonists: kissing, drive, kill, travels, assume, promises, love, stares, worries, punches, die, survives.

Women: hugging, talk, read, imagine, stays, decides, believes, love, hate, see, screams, shoves, dies, survives.

So much good stuff! And this isn’t even the actual book! See you should go buy it.

Okay, I’m still going, because there’s so much good stuff in this gem. There are twenty-two verbs that appear significantly more often in bestsellers, and non-bestselling books had only eight repeated verbs.

There are four top verbs to describe the mental and emotional expression of bestselling character and they are need, want, miss, and love.

Here’s a direct quote, “On average, bestselling characters “need” and “want” twice as often as non-bestsellers, and bestselling characters “miss” and “love” about 1.5 times more often than non-bestsellers.”

Bestselling characters not only do the right things in the right way, but they also speak in the right way. “The data on dialogue tags tells us that if you are a reader of heroines, for example, you likely won’t favor her if she begins, speaks, accepts, remarks, exclaims, mutters, answers, protests, addresses, shouts or demands.

Isn’t that awesome?

When I read this book, I almost died because it made so much sense. So many of the stories I love fit this exact model. The protagonists are active and strong who solve their own problems, and these word lists fit that model exactly.

I know I’ve said it several times, but the Bestsellers Code is one of the best books I’ve read and implemented in my writing. I printed out the entire list of use and don’t use words. I taped it on my computer so I could reference it whenever I needed to.

Now, I don’t sweat it if I’ve got a few don’t or shouldn’t, because I want to be a bestseller!

Let me talk to you (at you? Which one is more proper?), about a little more of what the guys at Bestseller Code do. You can submit your manuscript to them and they’ll analyze it for you. They use over 3000 data points, interpret, and organize them into seven aspects. After they give the manuscript a set of scores in star ratings.

The seven aspects are:

1) Plot and Emotion: They create a visualization of your plot shape in two ways. First is the traditional three act structure, then they look for a symmetrical and rhythmic plot line that will make pages turn.

2) Topic and Theme: Top selling achieve focus and clarity by having three or four focalized themes that claim 30% of the manuscript. They use two proprietary thematic models on every manuscript.

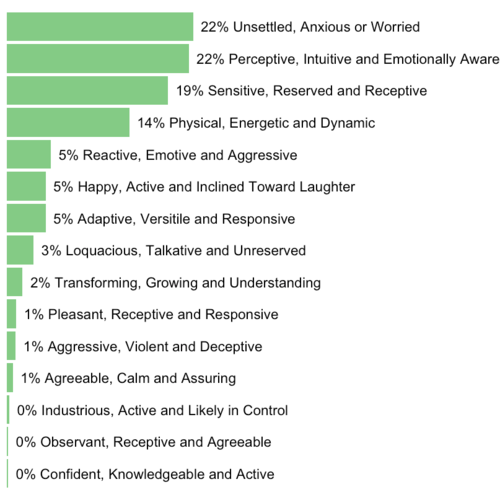

3) Character agency: The algorithms study the way characters behave and identify characters who will move the plot. (Um that picture isn’t mine, I got it from the bestseller website).

4) Character personalities: Authors should create some contrast in temperaments in order to develop a gripping plot. They discuss how adding and subtracting key scenes in certain plot moments can help authors create better character personalities.

5) Style: Their metrics provide information about the way a manuscript uses language. They examine sentence structure and syntactical complexity and then compare the data from your manuscript to similar data mined from thousands of other books.

6) Setting: Editors like to know about the geographical setting when they are choosing books for their specific list. Their process identifies the most prominent places in a manuscript.

7) Ratings: Bestselling is about finding the sweet spot in many of these areas. They rate every category using a five star rating system.

You can even download a sample review! They also have different services you can choose from.

Like I said earlier, when I’m ready I’ll submit my manuscript for them to analyze. I love data, and I know that they can help me make the most out of my manuscript! Yay!

So there you have it, a compelling argument to go purchase Bestsellers Code, and if you’re so inclined getting them to pick apart your manuscript too!!

Now, go forth and write

The post Bestsellers Code: Anatomy of a Blockbuster Novel Review appeared first on The Dangling Participle.

August 17, 2022

New Release Slivers of Infinity

I’m so excited and proud to announce the release of my book, Slivers of Infinity! Remember the pretty cover?

Time to celebrate Slivers of Infinity

Time to celebrate Slivers of InfinityTo be completely honest, there was a part of me that never really believed I’d release a book. That sounds so completely strange, because I’m such a big fan of story and writing. I mean, I do all this preaching at ya’ll! But I was convinced that I’d never really be good enough to release a book into the world.

Sounds stupid, right? But we all have our fears, and this is…or was mine. Because I know I’m not exactly Stephen King or Brandon Sanderson. My writing has its flaws, and I know it might not be super acceptable to admit flaws, but I have them. Surprising right! Hahahah.

Because of those flaws, I thought that I’d never really be accepted as a ‘real’ writer. But then I had a realization. I didn’t care.

I don’t care if I outsell Stephenie Meyer, or EL James. All I want to do is write stories, I want to tell stories. So they might be the biggest pile of crap in the universe, but they’re mine. I’ve got to say that my husband was a big help in coming to this realization and giving me that final push to publish.

Because of him, I can say that today Slivers of Infinity is out in the world. This book is close to my heart, probably because I love the story so much and I worked very hard on it.

Now, y’all can pop over to amazon and either get it through Kindle Unlimited, or drop a few bones to own it!

Now that you have a chance to take home an original AE product, your lives are complete.

Now, go forth and write!

The post New Release Slivers of Infinity appeared first on The Dangling Participle.

August 15, 2022

Slivers of Infinity!

I wrote Slivers of Infinity several years ago, and I was really excited about it. Probably because it combines some of my most favorite things (magic and pop-culture) into one glamorous book. There are even pancakes! It was a true labor of love, and I had some great expectations for it. But after receiving lots of rejections, I shelved it. Then I decided to scrap it for parts and moved on to romance. But this story kept hovering in the back of my mind, and with some urging from husband…I decided to self-publish it. Yep.

And I’ve got to be honest, at first I was very hesitant and terrified to finally release a book. There is a lot of emotions involved with being so vulnerable and so open with a creative labor. But, then I came to the realization that I always want to write. Even if I only get one star reviews. Even if everyone in the world rails against me and tells me what a horrible writer I am. Writing is a part of my very soul, and I have to write. I have to get these stories out and into the world. So I took the plunge. This will be the first book to bear my name, but it won’t be the last. Not even by a long shot.

So here we are, the cover reveal for my debut novel Slivers of Infinity.

The beautiful cover!

The beautiful cover!The Blurb:

5,000 years ago, in Ancient Babylon, a god named Infinity was killed, leaving behind Slivers of her essence and power.

Twelve men and women acquired much of that power (though not all), and quickly rose far above their fellow men. In time, they became known as gods, and were given new names. As far as humankind is concerned, they were nothing but myths and legends.

In reality, they moved.

15-year old Kace and 17-year old Jordan, a quirky pair of movie-obsessed siblings living in a New York City orphanage have a rather simple life: avoid dish duty, sneak into R-rated movies, and occasionally crash red-carpet events in their hometown of New York.

But they’re about to learn that there’s far more to the past, to themselves, and to the very nature of reality than even their wild imaginations can conceive.

I hope you’ll enjoy it as much as I loved writing it.

Now, go forth and write!

The post Slivers of Infinity! appeared first on The Dangling Participle.

March 22, 2022

The Scene Outlining Method

What’s up Padawan’s! Today I’ll be typing at you about my scene outlining process. I made this my next post because I covered my Plot Point Method last time, and in that post I mentioned my scene outlining. And instead of making you wait, I wanted to jump on it. It’s also because I’m in an especially good mood. The pancakes I made for breakfast this morning were very delicious. Yum.

You can think of scenes as mini-plots within themselves, because a strong scene should be structured like a little novel, with all the major plot points hit within it. Now scenes in themselves are something I’ll go in-depth later, because they’re more than just a grouping of words. A scene is a complex organism all to itself, with requirements and proper applications. But for now, I’ll just go into how I plot out individual scenes, because that’s the plan, Stan.

A scene is a sort of its own entity, a planet floating in a solar system, surrounded by other awesome planets, a life-giving sun, maybe a few annoying asteroids, a comet or two. Shit, should I have used a pancake analogy? Naw, this one works well.

So, every scene contains the same pieces of information, just presented in different ways, perspectives, or with new information. So what are those elements? I’m so glad you asked, Padawan.

The protagonist’s goals. Now, in a dual (or more) perspective book, this expands to whoever is the POV of that scene.Antagonists and allies: Characters that are there to support or thwart (that sounds like the name of a kick ass heavy-metal band ) the protagonist goals. These are the landmasses of your planet.Momentum: Also called action, which can be presented as actual action or dialogue. If you can’t guess, this element is essential for giving the readers a sense of forward movement through time and space. If you have no action or momentum, then you have no scene. However, you can have a highly contemplative scene with no forward movement. But too many of these and you’ve dramatically altered your readers’ experience. But there are some genres, like literary fiction with more contemplative scenes. But that’s getting into nitty-gritty details. Think of this as your scene planet spinning through space.New plot information: This can be presented as either a reaction/consequence of a previous scene, or a new plot goal. Think of this as the individual elements needed to create your scene planet.Thematic imagery: This is the meaning of your story shown through images and sensory details. This is your scene planet gravity. It holds everything together, gives it more meaning than just random rocks flying through space.Tension: Tension is the feeling of conflict and uncertainty that keeps the reader wanting and guessing. Tension is a natural by-product if the three layers of scene, action, emotion and theme are present in every scene. This is like your scene planet’s atmosphere.

) the protagonist goals. These are the landmasses of your planet.Momentum: Also called action, which can be presented as actual action or dialogue. If you can’t guess, this element is essential for giving the readers a sense of forward movement through time and space. If you have no action or momentum, then you have no scene. However, you can have a highly contemplative scene with no forward movement. But too many of these and you’ve dramatically altered your readers’ experience. But there are some genres, like literary fiction with more contemplative scenes. But that’s getting into nitty-gritty details. Think of this as your scene planet spinning through space.New plot information: This can be presented as either a reaction/consequence of a previous scene, or a new plot goal. Think of this as the individual elements needed to create your scene planet.Thematic imagery: This is the meaning of your story shown through images and sensory details. This is your scene planet gravity. It holds everything together, gives it more meaning than just random rocks flying through space.Tension: Tension is the feeling of conflict and uncertainty that keeps the reader wanting and guessing. Tension is a natural by-product if the three layers of scene, action, emotion and theme are present in every scene. This is like your scene planet’s atmosphere. Now to get into my scene outlining process, as with my Plot Point Method, I do all my scene planning on paper. It makes it easier to see what elements I have, and how to connect them together in the right fashion.

Now to get into my scene outlining process, as with my Plot Point Method, I do all my scene planning on paper. It makes it easier to see what elements I have, and how to connect them together in the right fashion.

First, I determine POV (Point Of View). This is who’s head we are going to be in during the scene. So POV goes to the top of my page, and next to it, the character featured. I’ll use the outline of the Sailor Moon inspired story I started recently for this post. Mostly because I have that right here, and I don’t have to dig through Dropbox to find it

At the top of my page, I write POV. In this example, it would be POV: Beryl.

Now to decide what the hook should be. Like the hook of a novel, it needs to be the grabbing element of the scene. It’s what’s going to keep the reader going. This means it needs to be something catching, unusual. Use what you know about crafting a killer hook, for your scenes. Remember, a scene is just a mico-novel.

In this first scene, the hook is Beryl crying at an ancient and cursed stone altar. She laments and bitches that Prince Endymion doesn’t love her, doesn’t want her. How he loves Princess Serenity, even though they are forbidden by the gods to be together. The nerve of some people!

Next on my scene outline is the inciting incident. This introduces the conflict/character goal of the scene. And just like the inciting incident of a novel, it should be character specific and exciting. The inciting incident of this scene is when a dark and foreboding force materializes through the darkness. The figure becomes more obvious, a red star gleaming on its forehead. While Beryl is afraid, she doesn’t leave the cave, screaming in terror. She stays to see what the dark figure wants.

This is the perfect place to dangle some new story questions for your reader. Info dumps can come once you’ve hooked your reader with some unusual and interesting tidbits. Using my example, so far the reader only knows that this chick is totally pining for some dude. Granted, he has the title of Prince, so I guess that’s why.

Like in your novel, this is where things move forward!

I call it the progressive complication. It’s sort of like the first pinch point. The protagonist’s goals are being exposed. It’s where things are heating up, they’re getting… complicated! This is where you sort of ratchet up the feel of the scene. So in my Sailor Moon story, the progressive complication is where the dark figure introduces herself as Queen Metalia of the Dark Kingdom. Queen Metalia then tells Beryl that she can win her prince, and become ruler of the entire planet! All Beryl needs to do for this to happen is to betray her people, and the two power crystals of the moon and Earth. Queue dramatic music.

Up next is the crisis. Sort of like the midpoint, the crisis is where things get really bad. This is where shit hits the fan. Where things go totally wrong. In my story, Beryl tells Queen Metalia everything for the ability to make Endymion hers, and rule the world. So basically, she sold her soul to the devil. Counts as a crisis, right? I think so.

Now up for the climax. Just like in your novel outline, the climax is the last fight, the ultimate confrontation. The last chance for things to go horribly right, or terribly wrong. In this Sailor Moon outline, the climax is where Queen Metalia changes Beryl into her minion, into a thing of darkness and shadow and despair. Poor girl, all over a bloke, too.

We’ve arrived at the resolution. The conclusion. The wrap-up. In my scene, it’s where Beryl leaves the cave, a changed person, a new woman, a force to be reckoned with. She walks from the dark cave into the light of a new day. An apt resolution.

Holy shit! There’s more? You bet there is. Because now we have organizational matters to take care of, house-keeping. Mostly because scenes can bleed into each other, and you should always have a clear idea of what each scene contains. So after the resolution you have setting.

This is where you define exactly where your scene takes place. Because remember, unless it’s under very specific circumstances, a scene is in one location.

So the location for this scene is a very extensive list: cave. Yep. She’s in the cave the entire time.

To be thorough, I also list out all the characters that are in this scene. Now, this isn’t for minor walk-on characters. This is for your main, of course, but also your secondary characters. In this example scene, there are two characters on the list. Queen Metalia, and Beryl.

Following characters I have foreshadowing. This is important, because foreshadowing needs to be taking place all the time! Now, I’m not saying each scene needs to have them listed out, but the majority of them do. Until you get later into the book, in which case it’s no longer needed.

Last but not least, I have tension. This is a sort of glossary for you to look over to make sure you included the elements that are needed to help create tension. For example, in my Sailor Moon story, under tension, I have listed as Beryl turning evil; betraying her people and the power crystals, and knowledge of what will happen because of that decision.

Once I get everything all written out, I spend a while reviewing it. This is where I have a last chance to alter the flow of the scenes before I type them all up. I’m not saying you can’t do that once it’s on the computer, but I find it a little easier to do on pages.

And for ease of use, I’ll list out my items so you can see them all in list format.

POV

Hook

Inciting Incident

Progressive Complication

Crisis

Climax

Resolution

Setting

Characters

Foreshadowing

Tension

So there you have it! My scene outline! This makes it so easy for me to craft scenes within my story. I can be as granular or as broad as I’d like. I can spend paragraphs describing the hook or crisis or just a few sentences. But, like always, this is just a rough frame of what works for me. Now you can take it and use it, adapt it, or totally disregard it. The power is yours, Padawan!

Now, go forth and write!

Go Forth and Write!

Go Forth and Write!

The post The Scene Outlining Method appeared first on The Dangling Participle.

December 24, 2021

The Plot Point Outlining Method

Salutations Padawan! Today, I decided to write about something very near and dear to my heart…Pancakes!

Lol, no, not really. Although, those are one of my most favorite things

A while back, I found myself really struggling to outline a manuscript. Shocking, I know, but it’s the truth.

It was a slog. I just couldn’t find an outlining method that I could latch onto and understand.

Sure, it sounds simple, “just follow the three act structure,” or “plot according to hero’s journey,” but that’s sorta like saying paint your kitchen blue. Everyone forgets there are 260 shades of blue. I tried the Sanderson Method, Action/Reaction method, Beat Sheets, Energetic Markers, the Brett Method.

Nothing really clicked for me, and I got frustrated.

Like, SO frustrated.

And then, in a moment of clarity, I decided… screw it, I’ll design my own.

For a while I just called it the Ashy Method, but that doesn’t sound as professional as the Plot Point Method… so I changed it. Cause I’m an adult. Sometimes.

If you’ve read my Plot Points post, then you already know all about the various plot points. Those really click for me because they are something I completely understand. Then I got to wondering if I could create an outlining method using those as the backbone. So I tried, and this is what I came up with.

Once you’ve done all your world building and character creation, once you know where your story will begin and end (where it ends is very important to know before you write), you can sit down and eat pancakes to celebrate.

But seriously, once those steps are complete, you can move onto actually outlining!

For this post I’ll use my zombie story I wrote a while back as the example.

The next step involves putting your thinking cap on. At the top of a paper, I write Hook. Then I write possible ideas for that hook. So, in my zombie story, my hook is where my big bad hero, Josh, kills a zombie!

Simple, straightforward, and a good hook.

Then here’s where it gets good. I write everything that has to happen before the hook for it to make sense, and everything after. So the lead up to the hook, and the reaction to the hook.

The next point is the inciting incident, and I basically rinse and repeat. I list potential ideas, working off what I’ve brainstormed coming off the hook. Making sure I keep in mind the purpose and intent of the point. Once I’ve decided on something, I decide what needs to happen before it, to lead up to it, and what happens after it, in response to that event.

Get the idea? This is a rough idea of what my zombie book outline looked like. Now, depending on your scene length, you’ll want to have more than just a few between the major points, but since this is just an example, I’m keeping it simple:

—

-Josh waking up in his cubicle home in T-Mobile park.

-Josh attending morning brief about zombie movements.

Hook: Josh kills a zombie in downtown Seattle.

-Josh consulting with the council about the increased zombies.

-Josh providing escort to the fishermen as they leave their boats.

Inciting Incident: Zombies attack in mass. Josh meets Max, a female survivor from the wilderness.

—

Make sense? This outlining method has really helped me organize my thoughts and allowed me to optimize my outlines. So I’ll continue with this example.

After the inciting incident rocks the boat, we need to have the character reaction to that event. So I’d follow with several reaction scenes to hit home the meaning of the inciting incident.

So the following scenes might look like these:

—

-Josh and Max defeat the remaining zombies and begin treating the survivors.

-Josh and Max meet with the council to discuss this new threat. Max tells her story and the info she’s gathered from the wilderness.

-Josh and Max eat together, both bloody and tired from the fight. Josh expresses his hopelessness.

—

Now that there are a few reaction scenes, it’s time to move on. The next big point is the midpoint, and the buildup to that point. And as I pointed out in the plot point post, the midpoint is an important moment to reveal new information. So as before, I brainstorm the best possible midpoint events. Once I settle on an event that really embraces the meaning of the midpoint and helps move the story forward, I list what needs to happen before and after:

—

-A coherent, injured zombie stumbles to the gate, begging for an audience.

-Max, Josh, and the council decide to hear them out, and they’re admitted under heavy guard.

Midpoint: The zombie tells them how zombie scientists are working on creating artificial blood/organs for zombies. That will allow them to kill off the meat (humans) and become the new world power!

-That information divided the council, half believe it, the others don’t.

-Josh volunteers to journey into the dangerous city to seek the scientists. Others, including Max, decide to join him.

-Problems and attacks plagued the trip into the city.

-Some of the volunteers are killed.

—

Getting interesting isn’t it? Are you seeing how this works? It’s almost like a sort of crossword puzzle. You have your major events, and the events that need to take place for them to make sense. I usually go through several drafts like this, mixing and matching events, determining which events make sense and whichdon’t.

To make it simple, I usually get a cheap dollar store notebook to fill out. I can rip out pages as they get crossed out and not worry about it.

Now, after the midpoint and midpoint reactions, the next plot point is the second pinch point:

—

-Josh, Max and the volunteers stay in a penthouse apartment to regroup. Max and Josh have a hot make-out session. (Yes, this zombie book had a romance subplot, so juicy!)

-The next morning the volunteers encounter a group of teens, with information about a scientist who defected.

Second pinch point- Josh, Max, and the volunteers come upon the scientist, injured, close to death. She tells them about the current location of the scientists. They’re attacked by zombies.

-Max, Josh, and some volunteers escape the zombie attack.

-Max, Josh, and the others regroup and head for the scientists.

—

We’re on the downward slope now! All that remains is the climax, so things are going to pick up quickly:

—

-Max, Josh and the others find the building where the scientists are hidden away.

-After investigating the building, they discover a group of human test subjects. Max convinces Josh to help them escape. He agrees.

-They help the test subjects escape, but trigger alarms.

-The scientists send a mass of zombies to stop them. Josh is injured.

Climax: Max and Josh discover the abandoned remnants of the scientists’ laboratories. And a virus meant to kill all humans. But the scientists are nowhere to be found.

-Max and Josh follow the scientists to a local airstrip where a plane is fueled and waiting to go.

-Max gets captured and taken onto the airplane. Josh cannot save her. The plane takes off, and Josh is devastated.

-Months later, the humans determine the scientists have created a new zombie base in Idaho. Josh packs a van and heads out to save Max.

The end.

—

Once I’ve got these all written out on their own pages, I lay them all out where I can see them. Then I go through each page carefully, making sure it flows logically. This gives me the chance to switch things around if it would make more sense in a different position. So perhaps scene two should be scene seven, and scene twelve would make more sense as scene fifteen. Once I’m happy with the order, I number them, and put them all into a word document. There I’ll flesh out each scene, outlining that scene with a scene outlining process I also developed!

Hahah, go figure.

Now, this is more than a quick sit down and sort of word vomit method. Each one of these points takes some serious thought and consideration. It takes brainstorming and a lot of paper to come up with these.

But the foundation is simple.

Each plot point is determined, then you fill out what comes before and after. It can take a while, so don’t be discouraged. But here’s the thing, this method allows you to consider the best approach and path you want your story to take. You can fiddle with each point until you’ve got everything just perfect.

That’s probably why I like this method the best, because I’m a fiddler. I like to mess with things for a while before I really decide which is best.

But, as always, you, as the unique starfish you are, can choose exactly which method to do. Which one works for you? Which one do you feel more comfortable with?

Experiment, test each one out, and eventually you’ll find one that works for you.

Or, you can follow my lead and develop one!

Now, go forth and write!

The post The Plot Point Outlining Method appeared first on The Dangling Participle.

December 12, 2021

All About Plot Points

Greetings, padawan  I hope that wherever you are, life is glorious! And to make it just a little more amazing, today I’ll be telling you all about plot points… Yay!

I hope that wherever you are, life is glorious! And to make it just a little more amazing, today I’ll be telling you all about plot points… Yay!

You luck dogs.

Now, in the world of writing, there are a lot of different ‘methods’ out there in regards to structuring your novel. There are energetic markers, three acts, four acts, the hero’s journey, and so many more. You could choose a different structuring method with each new novel you write and probably never run out. #truth.

But it’s up to you to decide which works best for you and how your mind works, because everyone is different. I know that’s shocking, but it’s true. So one method might not completely compute for you. Plot points in combo with the three act structure works for me. It totally makes sense to my brain, so that’s the method I use most when plotting out my manuscripts. But you, being the unique entity you are, can choose a different method, and even design your own!

Without further ado, enjoy this deep dive into plot points and you can thank me later

Some don’t include this within the whole ‘plot point’ bucket, but I do. Because in the beginning, you need something to grab the reader’s attention. This is the first time where your character’s morals, their values, will be shown for all to see. Readers will get to see what the hero is willing to sacrifice and suffer.

In the hero’s journey it would be closely related to the call to adventure. Now, in different genres, this is presented differently. If you’re writing a murder mystery, this is where the detective discovers the body. Or, in an action adventure, it might be the fireman running into a burning building. In romance, it’s where the two prospective lovers meet.

Let’s do some examples, because everyone loves a good example. An inciting incident would be when you pull out your leftover pancakes (clink the link and get my pancake recipe!) and spot a giant blob of mold on them! Gasp! The horror!

Okay, you want a better example? Got it.

The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins. The inciting incident for book 1 is where Effie calls out Primrose’s name, and Katniss volunteers to take her place in the games. Gripping, check. Emotional, check. Character defining, check. Introduces conflict, check. It’s an excellent inciting incident because you know exactly what’s at stake when the poor girl’s name is called. Certain death. And when her sister yells out, “I volunteer as tribute”, you know exactly what it will cost her. Excellent.

Now, the inciting incident is not to be confused with the hook. But they’re like cousins. Because the hook should occur within a page or two, and it should be attention grabbing. So in the Hunger Game, the hook would be Katniss hunting and the descriptions of the broken world. But its small fish, it’s getting a whiff of pancake. Not the entire thing, just something to ensnare the senses. Whereas the inciting incident is more meaty, has some stuff to chew on. So, like putting a delicious, fluffy pancake in front of someone, and asking them not to eat it.

Impossible to resist

The inciting incident occurs within the first act of your story, or the beginning. If you’re looking for a number, it should occur around the 15% mark. But it can fall wherever is natural in the story. If that’s the second page, go for it. The only caution is that if it falls too late, you might lose readers to boredom. And if it occurs too early, your readers might get bored as well. So, as with everything in life, it’s a balance.

Now, I love the inciting incident because it has the power to catapult the novel into the stratosphere. I’ll dive deep into the inciting incident later, but for now I hope you get the idea.

But this is what plot points are all about. They aren’t little ponds that can be skipped over. They are deep oceans that take months to cross…

Okay, that might be taking it a little far, but the idea works. Plot points are major events.

First Plot Point

Some say, and I might agree with them, that the first plot point is the most important moment in your story. Even more grand than the inciting incident, midpoint, or climax. Why you ask? Because this plot point begins the entire dance. This event is the bridge between part 1 and 2. Which means everything that happens before is set up. And everything that happens after is a response. In terms of story, this is huge! If you flop when writing the first plot point, your story might not recover, because your reader won’t know exactly what to expect.

Why you ask?

The essential story, the bones of it, the conflict, all of it is fully defined with the first plot point. Yes, this one moment in your story introduces the upcoming journey, question, or mission that your hero has. That’s all a story is. Tracing the path of a MC (hero or otherwise) through a journey, question, or mission. If you flop on the first plot point, your reader may not truly grasp where the character’s path lies, and that is dangerous. Because then a reader can make assumptions and become very disappointed when those assumptions aren’t met.

Let’s try to boil this down a little more clearly. The first plot point is the moment when something affects and alters your hero (status, plans, beliefs, life, etc.) and forces them to take action. The stakes are now tangible. The opposition is firmly in place. There is no going back. There is no other way except forward except through the murk.

It’s the inciting incident on crack.

Basically, if I can borrow a term from the hero’s journey, it’s the point of no return.

In our Hunger Games example, the first plot point is where the lie of a romantic connection between Katniss and Peeta begins, and in a double whammy where Katniss scores an 11 in her private practice. After those events, she can no longer be obscure and unnoticed. Her life is irrevocably changed, and there is no way to return to before.

Give the first plot point a lot of love and attention, and a ton of thought and consideration. Because if you nail it, you’ve got a tremendous advantage going into the second half of your story.

Like the inciting incident, the exact location of the first plot point can be up to the writer’s discretion, within reason, of course. But typically it’s found around the 25% mark. But by definition, the first plot point occurs toward the end of part one and beginning of part two (assuming a three-act story), so it can’t be too early, or too late or it’s no longer a first plot point.

First Pinch Point

There are only going to be two pinch points in a story. The first pinch point is smack dab in the middle of act two. The second pinch point is found in the middle of part three (again assuming a three-act story). So going by the numbers, at the 40% and 65% marks, respectively.

A pinch point is the most simple and efficient of the plot points. It’s like a baby plot point.

This is the place where the reader gets to meet the antagonistic force in its most pure, most dangerous, and most intimidating form. Yeah, that’s a lot of mosts, but they’re all important. This is the place where the reader will get a reminder of the danger and clearly sees the monster under the bed.

At this point, the hero needs to look into the antagonists’ eyes and know without a doubt what the bad guy wants and the power of that desire.

At this first pinch point, the hero needs to come face to face with the antagonist, not just hear it talked about or discussed. But the antagonist isn’t always a person. The antagonist could be whatever conflict is driving your hero. A big test, a first date, corporate America, lava. So, in this pinch point, your hero would spot lava flowing down the mountain, racing toward his home. See? He’s facing the antagonist, getting a first glimpse at the conflict to come.

The beauty of a pinch point is that it can be quick. It can be a simple scene, a glimpse of the storm. But it gets even more fantastic, the more simple and direct it is, the more effective it will be.

In the Hunger Games the first pinch point is where tributes start to die, and Katniss is forced to flee her safe place when the wall of fire comes for her. Then the careers find her and she goes up the tree, only to dump a hive of tracker jackers down onto the careers.

Katniss gets faced with the big bad of the story, both the careers and the game makers themselves. It’s the first glimpse of just how bad the games can get, and how much she’ll have to fight to escape.

The Midpoint

Oh boy, we’ve really gotten into it now! First, the inciting incident comes swooping in to catch our attention. Then the first plot point shifts everything and forces us down the path, and the first pinch point has shown us just how bad the baddies really are. Now, we arrive at the midpoint. The midpoint is like a flamboyant aunt. All dressed up, jewels, bobbles, fancy clothes. Ready for a night out on the town.

First, let’s define it: The midpoint is where new information is revealed, and it changes the experience and understanding of the hero, reader, or both. Yes, the character or reader suddenly knows that which wasn’t known before. It’s revelation. It’s knowledge. And some approach the midpoint like a plot twist, and that can really work.

Now, this can be previously existing, yet hidden information, or completely new information. But, I’ll get my big red flag out again; this doesn’t mean that you should withhold information in the first part of your novel just to have something to reveal at the midpoint. Sometimes the best way to increase tension is to reveal that information, because knowledge is power.

A good midpoint changes things through meaning. It’s like a good pancake. You’ve got the raw batter, tenderly mixed with love, then the midpoint arrives. The batter is heated, and flipped, to create something new and golden and delicious. That’s the recipe for a good midpoint. You have all the ingredients before, and the midpoint transforms it.

The midpoint is the turning point for the story. So far, your hero has been struggling under their burdens, slogging, miserable, down on their luck, just sort of shit combined with shit. They’re convinced that there is no way through it. The conflict is stronger than they are. But at the midpoint, that changes.

Ideally, the first half of the second act has altered them. You’ve presented them with challenges and surmounted them (even if they’re badly beaten up—physically and mentally.) Unless you’ve killed them, then that’s a whole other ballgame.

Think of the midpoint as a sort of turnstile. This is a swivel for the story, a point of movement, a pivot. Because before this point, your hero’s only been re-acting. They’ve been bombarded and beaten. But after this point is where they are finally reactive. They’ve transitioned into an active participant, and decided to go kick ass and take names.

In the Hunger Games midpoint Katniss allies with Rue. By uniting, they even the odds between them and the rest of the tributes. Then, in a stroke of madness or genius, they decide to destroy all the supplies outside the cornucopia.

See? Up to this point, Katniss has only been running and hiding. She’s avoided all conflict that wasn’t placed directly in her path. But at this moment, they decide to be proactive and begin to truly participate in the games.

The tides are turning.

Second Pinch Point

As with the first pinch point, this is a snack. A sort of yummy treat to go along with all the drama that you’ve already set forth.

So like blueberries or chocolate chips on your pancakes

But the first and second pinch points are twins. You’ll use the same sort of approach to this one as the first. Make it gloomy. Make it full of the feels.

In the Hunger Games the second pinch point is where Rue dies, and Katniss kills the boy responsible. It’s another grim reminder of what the games truly are, and what Katniss will have to surrender to win.

As I said above, the second pinch point is right in the middle of part three. So it should fall at about the 65% mark.

Third Plot Point

We’re coming down the home stretch. We’ve got the climax in our sights and we’re hurtling toward it like a Jedi seeking a Sith. The second half of the second act should empower your hero. They should have a victory, mental or physical, and they should feel renewed. Like he just finished his first pancake. It tastes so good, all that maple syrup and sweet flavors. But, alas, that victory is short-lived, because he still has to face another empty plate, and more struggles to fill it again.

Damn, I love my pancakes.

Now, the third plot point arrives. A reminder that your hero isn’t invincible. That they still have plenty of work to do to conquer the antagonist. This point point directly results from the antagonist. This is the bad guy making sure they remind your hero that at this stage, he still sucks.

By this point things are again looking grim. He’s failed at this conflict, he’s lost something, and he’s sure that the bad dude will bury him forever.

In the Hunger Games, Seneca Crane announces the rule change, that two people from the same district can win the games together. So, Katniss finds Peeta, and nurses him back to health. To do so, she risks her life to get medicine, and poof! She succeeds! But more icing is that she accepts the romance that she’s been fighting against. Things are going great until the game guys remove all the water and force them into their final confrontation.

This point should fall at about the 75% mark.

Climax!

No, I’m not talking about that special moment between you and your pancake

I’m talking about the peak, the culmination of all your hard work. The ultimate combination of struggles, fear, sadness, and all those negative things. Because this is it! This is the final showdown between your hero and your antagonist.

And boy did your hero have to earn it.

The climax is where your hero takes everything they’ve learned from this point and applies it. They transforms into an avenging badass who’ll chop through whatever your antagonist throws at him. But it’s still a struggle, because nothing is free here in story land. Being this important means that this is the point in your story with the greatest amount of drama, action, and movement.

Most final battles are grand and epic. Two forces of nature smashing against each other until one breaks. And even if it’s just a battle of wits, the climax should be just that. Two immovable forces colliding. Only one can succeed. Most likely, it will be your hero who wins, though not always. But don’t make it easy for them!

None of that Deus Ex Machina shit allowed in Good Story Land.

The climax is the high point of your story, and without it, your story will lack excitement or an overarching meaning. The climax is a signal to the reader that things are ending. Because nothing lasts forever, even the best stories. Except maybe that song “this is the song that never ends. It goes on and on, my friends!” Man, that’s a great song.

The climax should fall at the 90% mark-ish, but that depends on you. Most writers have a resolution to show the hero in their new world. But again, that’s up to writer discretion.

In Hunger Games, the conclusion is vicious! Cato, Katniss, and Peeta are being chased by these nasty beast creature things. They climb the cornucopia to get to safety. But then Cato tries some underhanded manipulation and Katniss ain’t havin’ none of it. So she shoots him in the hand. Except he falls, and as luck would have it, survives only for the beast things to chew on him. So Katniss, in her mercy, shoots him. Then there is some back and forth about some poisonous berries until both Peeta and Katniss are declared the victors!

The conclusion is sorta like a huge fat stack of pancakes, dripping with real maple syrup.

It’s a hard won victory. It’s struggle and blood and torment wrapped into one. But a good conclusion will leave readers feeling satisfied and hopefully leaving 5 star ratings all over the place.

That’s it, we’ve discussed all the major plot plots a successful novel should (usually) entail. These are just the briefest of glances at them, because they’re each more than a few paragraphs of explanation. But you’ve got the idea, right?

I use these plot points to outline my manuscripts. I decide what each of these events will entail, then I fill out the scenes that need to come before and after each point. And because I’m just a little humble, I call it the Ashy Point Method. Maybe I’ll go into detail for y’all. I’m sure it will be great.

But for now I’ll bid you adieu and happy writing!

Now, go forth and write!

The post All About Plot Points appeared first on The Dangling Participle.

November 30, 2021

Pixar’s 22 Rules of Storytelling

Pixar rocks, duh, and is probably (guessing here…) one of the most recognizable film studios in the world. Let’s skim over some facts, since I spent the time doing the research

Pixar’s films have been awarded 485 awards, including 18 Academy Awards, 10 Golden Globes, and 11 Grammys. 14 Pixar films are among the top 50 highest grossing films ever, and it has produced 24 feature films and counting.

People, that’s some serious story telling power!

Aside from the awesomeness that are their movies, we’re also lucky because a former Pixarian, Emma Coates, has given us what she has distilled as “Pixar’s 22 Rules of Storytelling.”

So let’s look at them!!

#1: You admire a character for trying more than for their successes.

This is a good one. Because how many times have you failed? Seriously, take a good long moment to think about the failures. Guess what? We’ve all failed. I’ve crashed and burned spectacularly, many times.

But now take a moment to think of all the ways you’ve tried.

This next statement is coming with a… strong note? A caveat? I love the Twilight series because Meyer does beautiful things with emotion and the senses… but… Bella. She does nothing. She mopes around, almost gets hit by a car, and asks questions. I think she’s an okay literary character, but she just doesn’t do much. That’s one of the big critiques of her character.

There are other characters who don’t “do” much. Hester Prynne from The Scarlet Letter. Despite my love for Pride and Prejudice, Elizabeth Bennet doesn’t do much.

But, think of the stories with MCs who put forth some effort. Hunger Games. Katniss DOES things. She tries and fails and tries again. Dory, she tries and fails, and tries again. She takes a moment to be all mopey, then rallies her spirits and tries. See!

Let’s drop a quote, from good old Einstein: “You never fail until you stop trying.”

It’s truth for you. It’s truth for your characters.

#2 You gotta keep in mind what’s interesting to you as an audience, not what’s fun to do as a writer. They can be very different.

I’ll debate this one, at least partially. I believe that as a writer you should write about what interests you, and you should have fun writing. You should never write a book, or short story, or novella, or anything with the sole purpose of selling books. That’s a recipe for failure.

That being said, you also need to consider market appeal.

Is most (or even some) of the public going to want to read about a gardener who sits and watches his veggies grow. All. Day. Long…

Is the public going to want to read about a serial killer who butchers babies and puppies?

Those might be the most interesting things for you to write, but they probably don’t have mass market appeal. But you can always adapt an idea for more mass market appeal. Maybe the gardener sneaks into his neighbor’s yards to save their dying plants. Maybe the serial killer butchers baby dolls and has yet to work up his courage.

I have many stories that will never see the light of day because they aren’t what the mass market wants to read. But they’re what I wanted to write at the time, and that’s okay. Not every story written needs to be published.

But if you’re planning on publishing and hoping to make any money (indie or traditional), you’ve got to consider what the public likes to read. It’s a must. So try to find the intersection of what you want to write AND what the readers want to read.

#3 Trying for theme is important, but you won’t see what the story is actually about ’til you’re at the end of it. Now rewrite.

This one hits close to my heart. Theme is one of those concepts that’s hard to pin down. I still have moments when I’m like, “What in the hell is theme?” Sure, you’ve got all these definitions and entire books dedicated to theme. But to me it’s one of those abstract concepts that everyone has their own opinion on.

Once you’ve gotten a first draft done, it’s much easier to see the theme that’s naturally occurred. Sure, you can start with a theme in mind, like man vs. nature, or society’s tendency to shove outliers out or burn heretics. But until you get the entire story out, you can’t really tell what theme shines through.

Sometimes it’s easier to let the theme determine itself through character, setting, and situations. After that first draft, you can look and say, “Oh shit! This story is about man’s natural inclination toward goodness”. Without having a first draft, there may be no way to determine theme perfectly.

Once your first draft is finished and you see the clear theme, THEN you can rewrite to highlight the theme through character, setting, and situations (or go back and change things if it isn’t the theme you want). See how that works? Now, you have a well-polished book (after like 3 or 4 drafts), that has a good theme.

Boom. You rock!

#4 Once upon a time there was _____. Every day, ____. One day _____. Because of that, ______. Because of that, ______. Until finally _____.

I’m gonna be a little brutal. If you don’t recognize the basic story structure in this rule, you need to go read more how-to books. Is that mean? #sorrynotsorry

This is THE classic Hero’s Journey, and you should burn it into your brain because it works consistently.

“Story is character. Story is conflict. Story is narrative tension. Story is thematic resonance. Story is plot.” (A great quote from Larry Brooks, Story Engineering). This rule encompasses most of those.

Once upon a time – a classic beginning, and all stories need to start somewhere. Every day – this sets up the Normal World. One day – introduces the New World. Because of that – introduces the Conflict. Because of that – is the Climax. Until finally – the Conclusion.

Character -> Normal World -> New World -> Conflict -> Climax -> Conclusion

Every good story can fit into that rule. Let’s test it.

Once upon a time, there was an orphan boy named Harry Potter. Every day, his aunt and uncle and cousin tormented and abused him. One day, he discovered he was a wizard and an evil wizard killed his parents. Because of that, he went to a prestigious wizard school and came face to face with the evil wizard. Because of that, the evil wizard tried to kill Harry and take over the world. Until finally, there was a huge fight, and people died, and Harry killed the evil wizard.

Granted that’s a loose summary, but it works, doesn’t it? Don’t believe me? I’ll come up with a story idea on this very spot.

Once upon a time there was a boy who walked in the surf, digging in the sand to find clams. Every day, he’d try to find enough clams to fill his bucket, or he’d face the wrath of the Governor. One day in the surf, he didn’t find clams. He found a dagger that spoke to him when he held it. Because of that, The Governor tried to have the boy killed. Because of that, the boy escaped his seaside village and found a weapon smith who taught him to fight and speak to other weapons so he could overthrow the Governor. Until finally the boy returned to his seaside village to face the Governor and successfully freed his people.

See! That might not be the most compelling story ever, but I bet it would be interesting. Maybe I’ll save this for a prompt, and perhaps one day you’ll see this story on bookshelves everywhere

#5: Simplify. Focus. Combine characters. Hop over detours. You’ll feel like you’re losing valuable stuff but it sets you free.

Oh, the truth. I can’t even describe the amount of truth here. I’ve got several stories loaded with scenes and sections I didn’t want to cut. The stories get so bogged down with the little things I thought were “soooo cool!” But in fact, many are unnecessary.

My trick is simple. Write a section or scene without whatever. Whatever character, scene, situation, dialogue. Then you can see just how that omission helps (or hurts) the story.

The best example I can use is Wheel of Time. Fantastic books, but they could have easily been 50% shorter without losing any of the story just by trimming back on Jordan’s excessive descriptive style.

It’s hard, but challenge yourself, it will make worlds of difference.

#6 What is your character good at, comfortable with? Throw the polar opposite at them. Challenge them. How do they deal?

This is one of those statements that is much easier to say than to do. Basically, to implement this one, you must know your character inside and out. Your character’s motivations, planned character arcs, normal human reactions, ya know, the works. It’s hard. I’d really recommend Orson Scott Card’s book Character and Viewpoint and K. M Weiland Creating Character Arcs: The Masterful Author’s Guide to Uniting Story Structure, Plot and Character Development. I’ll speak more on these titles later. But for now, just know they rock.

When I was dating my husband, a long, long, long time ago, my mother told me he needed to see my “every season.” Meaning he had to see me at my best, and worst, no makeup, hair messy, PMS, homicidal moods. He did, and he still wanted to marry me. That’s super relevant to your character!

To make a good story, you need good characters. To have good characters, you need to KNOW them. What are they afraid of? How do they react to that fear? What makes them happy? How do they react when they’re happy?

A good place to start, aside from the above books, is by building out a detailed Character Map. Until you know your character deeply, you won’t be able to write them effectively.

Once you know your character so intimately you could marry them, then it’s time to make their lives a living hell.

Story is conflict, and part of that conflict comes from making your characters miserable and seeing how they deal. Seriously.

Hunger Games. Katniss is good with a bow. Does she get one immediately in the games? Nope. Conflict. She’s not a people person. She’s partnered with a boy. Conflict.

Harry Potter. He’s used to being alone. Suddenly, he’s famous. Conflict. I could go on, and on, and on. But I think you get the idea.

Know your character. Bombard your character with everything that makes them squirm. Yank things away. Kill besties. Challenge them, and your story will suddenly be so much better.

Another relevant and wonderful quote: “When in doubt, make trouble for your character. Don’t let her stand on the edge of the pool, dipping her toe. Come up behind her and give her a good hard shove. That’s my advice for you now. Make trouble for your character… Protagonists need to screw up, act impulsively, have enemies get into trouble.” – Janet Fitch.

#7: Come up with your ending before you figure out your middle. Seriously. Endings are hard, get yours working up front.

There are a lot of writers who admitted to writing, or at least knowing the ending first. Robert Jordan wrote the ending to Wheel of Time first. I’ve heard rumors that JK Rowling planned the ending of Harry Potter first. Same thing with Stephenie Meyer and the ending to her Twilight series.

When you know where your characters and story will end up, you can plan backwards. If you know Frodo will destroy the Ring, then you can focus on those character complications and conflict, and progressive complications. You can plan all those deviations to his journey.

Here’s a famous scene from Alice in Wonderland:

Alice: “Would you tell me, please, which way I ought to go from here?”

The Cheshire Cat: “That depends a good deal on where you want to get to.”

Alice: “I don’t much care where.”

The Cheshire Cat: “Then it doesn’t much matter which way you go.”

Until you know where the story is going, you can’t effectively write how to get there.

What do you have to lose? Plan your ending first and see what happens.

A quote from someone you’d recognize: Joyce Carol, “The first sentence can’t be written until the final sentence is written.” (Yes, pantsers will fight me on this one. They’re wrong  )

)

#8: Finish your story, let go even if it’s not perfect. In an ideal world you have both, but move on. Do better next time.

Another one I completely understand because I started out as an artist. Way back in the day, my mom enrolled me in oil painting lessons. I learned from a most talented artist who lived down the block. Every Saturday morning I’d run down in my PJs, and paint. #truth. It was then I learned the essential habit of being able to let go. You can work on a painting, or a manuscript endlessly. Months. Years. Decades. Eons. Forever.

Just ask Pat Rothfuss or George R.R. Martin

There isn’t something I can say to define when it’s done. I can’t say “When you reach this point… It’s done.” It’s not that simple.

You need to come to terms with that yourself. Endless massaging and word changes could ultimately end up ruining the perfection. Reach the end of your story, edit mercilessly, submit or indie publish.

If you’re a true author you’ll be endlessly learning and improving. You’ll have a thirst to improve. You can’t do that if you’re stuck on a manuscript. Move on. Take what you’ve learned and apply that to a new manuscript.

Every single manuscript I’ve written, new or re-write, has been better than the one before. Because I’m always learning.

Finish. Move on. It might be hard, but (I’m being mean here…) don’t be a coward. The world deserves your best work.

#9 When you’re stuck, make a list of what WOULDN’T happen next. Lots of times the material to get you unstuck will show up.

Now, here’s blunt me. I don’t believe in writer’s block. I don’t. A writer’s job is to write. Now, that’s not saying I don’t believe in being creatively drained. I TOTALLY think that’s a thing. But I don’t think traditional “stuck and unable to write” writer’s block exists.

So let’s assume you’re stuck somewhere; this is a great exercise you can either do it on the character or conflict level. You can list things that would make the character uncomfortable, or sad, or embarrassed. Character drives conflict. Conflict drives story. Another way someone can do it is at the conflict level, via events that would drive the story forward. That might be a little harder if you’re already struggling with what happens next. But that’s where a good outline comes from. See the circle people?

Most times, making your protagonist uncomfortable is what drives the story forward. That provides the events to get you unstuck.

Quote from someone vastly more famous than I am:

“As writers we’re lucky. If we’re not productive, we can blame it on ‘writer’s block,’ an ailment that doesn’t seem to exist for other professions. For instance, shoe salesmen do not get ‘shoe salesmen block.” – Neil Gaiman

#10: Pull apart the stories you like. What you like about them is part of you; you’ve got to recognize it before you can use it.

Oh, the beauty of this. One of my most favorite practices is “analyzing” books. Namely, my favorites and whatever is best-selling in my genre. I find it so helpful in so many areas, like sentence structure, organization, character, scenes, and a host of others.

The key to becoming a great author is not just writing, but READING. Read, read, read. I know that’s what everyone says, but it’s true. You learn by experiencing and feeling and exploring.

Storytellers need to learn how to tell stories. Some storytellers have an instinctive ability to tell stories well, but even those “naturals” need to read for ideas and raw material to sculpt with.

Whenever I find a story I like, I sometimes read it three or four times. My favorite books I’ve devoured repeatedly. And I know exactly why I like them. Because I’ve pulled them apart.

The best actors always draw from some part of themselves that they have in common with the character they will be playing, fueling the false with something real to imbue it with substance. To use a fun analogy, just as a Voodoo doll requires a bit of the target’s physical material to empower it, so too does a good character require some part of you to enliven it.

#11: Putting it on paper lets you start fixing it. If it stays in your head, a perfect idea, you’ll never share it with anyone.

I’m such a big advocate of just writing. Even if you never, ever publish, just write. As of 2021, I’ve got about 2 million words written. I’d say 90% of those won’t ever be published, and were for practice and learning.

Just write. It doesn’t matter if you don’t know how to spell library (I didn’t for the longest time… seriously), or if you don’t know the proper use of a ; (I’m still a little hazy on that one…), or if your story is just a rip off Rapunzel with a male lead. It doesn’t matter. Just write.

Because every word you write, every sentence you create, every flawed character or unconvincing villain you write will make you better. You’ll improve with every word.

Then after you practice, you can identify the issues with your story, or craft, or ideas, then POOF, you can fix them. But you’ve got to take the biggest step. JUST WRITE.

Another quote that will make you grin:

“Fill your paper with the breathings of your heart” – William Wordsworth

#12: Discount the 1st thing that comes to mind. And the 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th– get the obvious out of the way. Surprise yourself.

Man, these Pixar guys really know their stuff. This is beyond true. I can’t tell you how true it is. The number of times I’ve come up with the most brilliant idea, for anything, story, scene, character, anything…then noodled on it, and decided it wasn’t so brilliant. Then repeated.

Finally, after I’ve exhausted all the routine and normal, I’ve come up with an actual brilliant idea. Never settle. Always be thinking of different angles and ways. You’ll be rewarded for the extra work.

Showers and baths are my favorite places to noodle and come up with stellar advancements. But, the trick is without music, because music occupies the brain and you can’t think. My go-to brain-turn-off-sounds, thunder. Yep, get one of those white noise apps, and put on some rain and thunderstorms. So soothing and lets your brain wander.

#13: Give your characters opinions. Passive/malleable might seem likable to you as you write, but it’s poison to the audience.

It’s my opinion that this might be one of the main foundations of character. So many times, authors neglect character for story, or events. But the entire reason to craft a story is to allow readers to inject themselves into character, to go along for a ride in someone else and experience life and events and adventures they never would otherwise.

If you’ve got a character that’s so unlike the reader, because they’re soft balls of undefined fluff, you won’t sell a copy to anyone but your mom. #truth

You need to write characters that someone wants to take for a ride!

Flaws create character. Motivations and drivers create character. If you don’t give your character compelling and strong opinions, then you’ll be missing out on creating memorable characters.

I’d really recommend reading Orson Scott Card’s book Characters and Viewpoints (regardless of how you may feel about him personally, his writing skills are legendary and worth learning from). It’s an invaluable resource about character and learning how to craft one hell of a character. Shit, how many times can I say character? Lot’s I guess.

Character, especially the protagonist and antagonist, deserve a lot of your attention, a lot. Because character is story, and your readers will dive into a well-developed and interesting character with ease.

Parting thought; you have opinions, beliefs, biases, likes, dislikes and quirks. Why shouldn’t your characters?

Quote from someone you recognize (for good reasons or bad ones, lol):

“I write to give myself strength. I write to be the characters that I am not. I write to explore all the things I’m afraid of.” – Joss Whedon

#14: Why must you tell THIS story? What’s the belief burning within you that your story feeds off? That’s the heart of it.

I’ll start this one off with my most favorite quote, Franz Kafka said, “A non-writing writer is a monster courting instantly.”

Now, if that doesn’t get your heart beating just a little faster, I don’t know what will. Being a writer doesn’t mean sitting down at a keyboard and typing. It’s the intense burning that happens when I have a story that needs to be told.

If whatever story you’re trying to write doesn’t burn within you, if you don’t suffer when you’re not typing (or writing), if you don’t dwell and daydream about this story, it might not be the right one.

Write the story you can’t not write.

#15: If you were your character in this situation, how would you feel? Honesty lends credibility to unbelievable situations.

Now, this one I might have a bone to pick with, but it’s a tiny one. I’m a firm believer you shouldn’t base your characters entirely on real people, or yourself. Using some of their character traits is fine, but pieces, not the whole. But I don’t base my characters wholesale off myself, or anyone I know. Why?

For one, you can never truly know someone else, not really, even spouses or children. Because you’re never in their head, you don’t know what makes them tick. And most people don’t even know themselves all that well. So why risk representing anyone poorly?

I also think every character should be crafted to the extreme. I’ve even taken the Myers-Briggs type indicator for my characters, to figure out what they’ll do. You need to be completely familiar with what your character’s personality will allow for. Are they so shy they stumble over words when a new person arrives? Do they shout uncontrollably when they’re angry?

You need to know with extreme precision HOW your character will act in any situation. Even if that means consulting with a psychologist to figure out exactly how they’ll react. Or you can Google it. I’m sure Google has the answer, lol.

Quote from someone famous: MJ Bush, “step into a scene and let it drip from your fingertips.”

#16: What are the stakes? Give us reason to root for the character. What happens if they don’t succeed? Stack the odds against.

Ah, steaks, I love me a good steak. Medium rare, a nice sear, maybe some good marinated mushrooms or asparagus and béarnaise sauce…

Oh, stakes, not steaks. My bad. Well, since I’m not a vampire, I’m okay with stakes too.

Stakes. Now, not gonna lie, this is something I have trouble with. Sometimes creating a story with high stakes can be challenging. But I’m getting the hang of it, primarily because I’ve studied great books (for a complete list see here).

Now, it must be understood that reading is not a passive process. The reader has got to FEEL all the things, through a combo of raw emotion and story tension. Now, in Orson Scott Card’s Character and Viewpoints, he outlines all the different ways to create the stakes and tension. I’ll just give a brief overview.

There are emotional, physical, and situational tension, things like grief, suffering, pain, and more. Probably the best way for a reader to feel tension is to make the stakes known.

Children of Men, a movie I know where they make the stakes known early on (women can’t have any babies), and every time the single pregnant woman is in danger you feel TENSION, because you know the STAKES! Poof. It’s an amazing movie, because you know exactly what will happen if she dies.

Tension and stakes people, and the best way is to reveal information. Secrets aren’t the best way to increase tension. I’d say it’s one of the worst.

#17: No work is ever wasted. If it’s not working, let go and move on – it’ll come back around to be useful later.

I wonder if they sang ‘Let it go! Let it go! Turn away and slam the door!’ while writing this. I know I did.

I’ve got files, and folders, and drawers, and notebooks all full of ideas, characters, settings, plots, ideas, and phrases. I’ve cut entire people, scenes, situations, dialogue, and so much more. Deleted? NO! Absolutely not. I delete nothing, I just tuck it away into a future possibilities folder.

Because anything can be transplanted (usually with minor alteration) into other stories. I’m not sure I can stress this enough, don’t give up. That character you loved but just doesn’t fit into your current story? Save them! The really awesome dialogue you can’t find a place for? KEEP IT! Everything is a remix.

#18: You have to know yourself: the difference between doing your best & fussing. Story is testing, not refining.

Backstory warning! I rewrote one of my books, an epic fantasy FIFTEEN times. Partly because I was fussing, I was trying to shove all these things into the book that didn’t really belong. But I desperately wanted it to work, and it never did. I shelved that project for later, when I improve as a storyteller to a point I can do the story justice.