Edward Willett's Blog, page 45

January 17, 2013

I finish a play…and sing of Saskatchewan

As I’ve mentioned, I’ve been writing a play, tentatively titled The Piano Bench: A Love Story with Evening and Ghosts. Today I finished the draft script, which I’ll be passing on the fine folks at Regina Lyric Musical Theatre, which I hope will be staging the play (with me directing it) this fall.

As I’ve mentioned, I’ve been writing a play, tentatively titled The Piano Bench: A Love Story with Evening and Ghosts. Today I finished the draft script, which I’ll be passing on the fine folks at Regina Lyric Musical Theatre, which I hope will be staging the play (with me directing it) this fall.

Since it’s a play with music, I’ve assembled a CD of the songs I’m thinking of including in the play, all of which are drawn from the old sheet music in this house of mine, which has been in my wife’s family since 1939. (The house, and specifically the piano and this music, are in fact the inspiration for the play.)

I was able to find recordings of every piece of sheet music I had, except one: “Saskatchewan,” the song by Irving Caesar, Sammy Lerner and Gerald Marks I posted the lyrics to a little while ago.

So…I recorded it myself. The accompaniment was generated by Band in a Box, an absolutely astonishing program I’m having a blast experimenting with.

It’s actually a pretty swinging little number!

Enjoy!

January 16, 2013

On narrating the audiobook of my own novel

The audiobook version of my young adult fantasy novel Spirit Singer (the book which is also soon to have a new print and ebook edition from Tyche Books), is now for sale at Audible.com, which is exciting because a) you never know, someone might buy it, and b) I narrated it myself.

The audiobook version of my young adult fantasy novel Spirit Singer (the book which is also soon to have a new print and ebook edition from Tyche Books), is now for sale at Audible.com, which is exciting because a) you never know, someone might buy it, and b) I narrated it myself.

Spirit Singer is the third book I’ve narrated for Iambik Audiobooks: the first was The Other by Matthew Hughes, and the second was a non-fiction book on child development (well, a few chapters of it) for Pearson.

And what have I learned?

Different things for each book.

Narrating The Other, I discovered there’s no pleasing everyone: although the proof listener at Iambik praised my narration, the only reviewer to thus far post an opinion of the audiobook (even though her name is Alice, like my daughter) was…um…less than impressed.

On the other hand, my almost-blind 90-year-old mother-in-law (who is also named Alice), who listens to a lot of audiobooks, liked my narration way more than many others she hears, so there.

Narrating the textbook on child development, I learned that you should really look up the pronunciation of difficult words before you start recording, so you don’t have to run off to the computer in the middle of the chapter and edit out the swearing.

And narrating my own book…

I discovered if you’re a man with a deep voice and your narrating a book featuring a teenage girl protagonist, you really can’t make yourself sound like the character. The closest I can come to a teenage girl’s voice is actually a pretty good impersonation of Mickey Mouse, and Mickey, though a talented rodent, just wasn’t right for the part.

I discovered…well, reinforced my existing knowledge of the fact…that reading out loud is the best way to find, not only typos, but awkward phrasing and clumsy sentences. Alas, much like looking up pronunciations before recording, one should really do the reading out loud and finding of said typos and awkwardnesses prior to the book being published, when there is nothing to be done about them but hope no one else noticed them…which, alas, someone, somewhere, almost certainly has.

But I also discovered, at least in this instance when years have passed between the writing of the book and my reading of it out loud, that I rather like my own stories: that I can, in fact, occasionally turn a felicitous phrase, construct an effective and exciting action scene, and craft characters to care about.

That may sound odd, but it’s actually very easy to come to the end of a book project and be more disappointed than anything else. You’ve been focusing on the flaws for so long that the flaws are pretty much all you can see, and when other people tell you the book is good, you accept the compliment with a gracious smile, but inwardly you’re thinking they’re idiots, because you know perfectly well the book is a mess and is probably the last thing you’ll ever write or get published.

Or maybe that’s just me.

At any rate, it was a pleasure to come back to an old book of mine and find that, in fact, it really is pretty good.

I enjoyed reading it out loud. I hope a few people, at least, will enjoy listening.

Although I probably can’t count on that Audible reviewer of The Other to be among them.

January 14, 2013

The science of tall trees

Sometimes science is focused on really big questions: where did life come from? How did the universe begin?

Sometimes science is focused on really big questions: where did life come from? How did the universe begin?

But sometimes, the focus is much smaller. Sometimes, researchers set out to answer a simple question, one that many people have perhaps asked, but no one has ever set out systematically to answer.

A question, for example, about trees.

Trees are everywhere. You’d think there’d be very little to learn about them at this late date. But there are still questions to be asked and answered.

For example…why do the tallest trees all top out at about the same height? And why are the leaves of those trees all pretty much the same size?

That was the question that Maciej Zwieniecki, a biologist in the UC Davis Department of Plant Sciences, and biophysicist Kaare Jensen of Harvard University set out to answer. And though the question itself falls firmly in the realm of biology, they found the answer lies within physics.

Also, plumbing.

According to Zwieniecki, “It all comes down to the leaf size and tree height that provide for the optimal flow of sap and energy throughout the tree.”

The researchers chose to focus on angiosperm trees (angiosperms are the flowering plants; angiosperm tree species include things like oaks and sycamores, as opposed to the gymnosperm trees like pine and spruce).

They analyzed data on 1,925 angiosperm tree species and found leaf lengths ranging from less than one inch all the way up to more than four feet. But there was nowhere near that much variation in leaf size in the tallest angiosperm species, all of which had leaves between about four inches and eight inches long.

The reason, Zwieniecki (boy, is that a hard name to type) and Jensen say, lies in the tree’s fluid dynamics: that is, the way fluids move through it.

Plants, of course, feed themselves through photosynthesis, a process which uses the energy from sunlight to convert water, carbon dioxide and minerals into carbohydrates: plant food.

This plant food takes the form of a sugar-rich fluid, which is transferred from the leaves to other parts of the tree via a system of channels, called phloem.

The researchers simplified the problem by creating a computer model of the phloem, treating it as if it were composed of permeable, cylindrical tubes. In the model, as in a tree, the leaf phloem collected the sugar-rich fluid and generated energy to transport it down to the much longer tube running through the trunk down to the roots.

What they found was that the fluid gathered speed as it passed through the leaf phloem as more and more water was pulled into it from the leaf through osmosis, just as tiny rivulets high on a mountain flow together to create a rushing river further down. The longer the leaf, the faster the fluid flowed.

Once the liquid reached the trunk, no more sugar was being pulled into it from the surrounding tissue: instead, it drew only water. The much longer trunk phloem also presented much more resistance to the fluid’s flow.

Larger leaves can be beneficial because they produce more nutrient-rich fluid, which flows more quickly toward the trunk and the roots. Trunk height can also be beneficial, because it provides better access to sunlight—but trunk height also increases the resistance faced by the nutrients. A very tall trunk provides enough resistance that there is no benefit in a larger leaf size.

Within the model, those two things—optimal leaf size and optimal trunk size—intersect at a point where the trunk is about 100 metres tall and the leaves are no more than eight inches long: just like in the tallest angiosperms in nature.

These findings also help explain why there are very few tall trees in environments with limited water; or, to put it another way, why the tallest trees are found in the world’s wettest environments, such as tropical rain forests or foggy river ravines. To grow tall, a tree has to have a substantial flow of liquid coming from its leaves and tissue in order to overcome the resistance of its trunk. In a dry environment, that liquid just isn’t available.

An earth-shaking discovery? No. But it’s a little too easy to focus on the big discoveries in science. Most are of a much smaller scale…but of such small pieces is the mosaic of our understanding of the universe constructed: and you never know when one small piece will suddenly make a much larger section become clear.

January 13, 2013

Retro Sunday: Saskatchewan Roughrider ashtrays…and the Italian connection

I know that sports teams have avid followings in many cities, but I doubt there are many places whose pride and interest in a team exceeds that of the fans of the Saskatchewan Roughriders. I won’t delve into it here—there are whole books about it, not to mention art exhibits—but although there are certainly people in this province who don’t cheer for the Riders or follow their fortunes (it’s fashionable among some artsy types to decry the money “wasted” by fans on the Riders, by which they mean they are as green with jealousy as the fans are with face paint: one way or the other, in Saskatchewan, you bleed green), most folks are onside.

I know that sports teams have avid followings in many cities, but I doubt there are many places whose pride and interest in a team exceeds that of the fans of the Saskatchewan Roughriders. I won’t delve into it here—there are whole books about it, not to mention art exhibits—but although there are certainly people in this province who don’t cheer for the Riders or follow their fortunes (it’s fashionable among some artsy types to decry the money “wasted” by fans on the Riders, by which they mean they are as green with jealousy as the fans are with face paint: one way or the other, in Saskatchewan, you bleed green), most folks are onside.

I’m not the most rabid of fans, but I do follow the team’s fortunes, and I married into a family with terrific season tickets (row 13, home side, 50-yard line), so I’ve become a regular game-goer.

It was my wife’s grandparents who first purchased the season tickets, probably in the 1960s, and it was also they who at some point acquired these…ahem…lovely early examples of team merchandising.

One of the ashtrays bears a sticker: Ceramicana by Danesi, Toronto, Canada. So although you’d swear looking at these things that they were made by some local potter with lots of Rider Pride but not an inordinate amount of design skill, they were actually mass-produced in Toronto.

Possibly they were a Saskatchewan design which Danesi was commissioned to make. Equally possibly, and maybe more probably, Danesi made a football ashtray that any team could purchase and adorn with its name. They were clearly made in a mold, since the letters, though they look hand-applied using thin strips of clay, are identical on both ashtrays.

Danesi Art, the company that made them, has left very little of a footprint on the Internet: a few pieces of pottery show up on antiques sites and eBay, but as for the company itself, all I could find was this mention, on a site devoted to Canadian Pottery:

Danesi Arts (1937-1975), a Toronto plaster and pottery giftware manufacturer. Their ceramic items (produced from 1955) were cast from original designs created by founder Primo Danesi or commercial moulds. A Danesi copy of the Blue Mountain Pottery angelfish appeared on eBay in June and sold for $45. It’s (sic) slightly smaller size indicated that it was molded from a Blue Mountain Pottery original.

I would have guessed the ashtray dated from the 1960s or early 1970s, and this seems to support that.

From that brief description, I also gleaned a name: Primo Danesi. It’s a name that does not show up much on the Web, either, which is actually useful for this kind of research, since it means you don’t have to worry too much whether you have the right Primo Danesi or not. (Had it been the John Smith Pottery Company, it would be much harder.)

Which led me to this: on a site devoted to the experiences of Italian Canadians in the Second World War, a letter from Primo Danesi to to Ruggero Bacci. Dated February 16, 1943, it’s on stationery from the Danesi Art Manufacturing Co., eventual makers of these Rider ashtrays.

Ruggero Bacci was arrested and interned, as were many other Italian Canadians, at the start of the Second World War. Prior to his arrest, the site states, Ruggero Bacci had been working for the Florentine Lighting Company. He was arrested at his workplace along with co-workers Antonio and Pietro Danesi. “The exact relationship of the Danesi brothers to the writer of this letter is not known,” the site comments, but “The writer notes that Bacci’s son Aldo is employed by the company, and implies a strong friendship between himself and the Bacci family.”

The letter reads:

How are you coming along now? Good I hope. Everything here is fine except the weather. It’s terrific!!! Aldo is still working for me and he is coming along real good with his painting. Aldo was telling me he thought there was hopes of your coming home. I was speaking to your wife and they are all happy with the prospects of your home coming. I really want to see you back myself, Ruggero and I’m sure lots of other people do. I guess you know how hard it is to get people for my type of work just now and I want you to know I have a job for you as soon as you’re released. I’m in my new home now but however I won’t explain that as you’ll see it when you come out.

It’s signed, “Your Friend, Primo Danesi.”

Finally, I found one other mention of Primo Danesi: the dedication to a book entitled Cool: The Signs and Meanings of Adolescence by Marcel Danesi (University of Toronto Press, 1994). It reads:

This book is dedicated to the memory of my late uncle, Primo Danesi. He made me understand, early in life, that the human spirit manifests itself continuously in actions that are kind and generous.

From one other brief note, I think Primo died in 1979.

Marcel Danesi, his nephew, is a professor of anthropology at the University of Toronto. Which means, if I now wanted to use this as a springboard into researching the life and work of Primo Danesi and the Danesi Art company, and eventually trace back the precise lineage of my rather ugly ashtray, I could call Marcel and go from there.

I won’t–because, you know, no one is paying me to do this, so the time I can devote to it is limited–but I remain fascinated by the endless webs of connections that surround us…and the remarkable ease with which you can at least begin to untangle those webs thanks to the greater Web into which almost all of us are now plugged.

January 12, 2013

Free Novel Saturday: Star Song, Chapters 7 & 8

Every Saturday I post a chapter or two of my young adult science fiction novel

Star Song

. Coming in in the middle? The whole thing starts here with Chapter 1 and an explanation.

Every Saturday I post a chapter or two of my young adult science fiction novel

Star Song

. Coming in in the middle? The whole thing starts here with Chapter 1 and an explanation.

Enjoy!

Star Song

By Edward Willett

Chapter 7

Kriss lay sleepless late into the night, staring up into the darkness. Whatever Tevera said, he wouldn’t give up so easily. She had to be wrong. There had to be a way for him to get into space. Tomorrow he’d ask Andru.

At the thought of the innkeeper he felt guilty. The man who had attacked him in the alley had also broken into Andru’s, and Kriss knew how much Andru would have liked to get his hands on him. But a promise is a promise, he told himself, and I promised Tevera I wouldn’t tell anyone about us being together if she’d find out what she can about my parents.

He threw himself onto his right side, uncomfortably aware that he was using, in a way even blackmailing, the offworld girl. But she wouldn’t have helped me otherwise! he told his conscience.

Somehow that didn’t make him feel any better.

The next morning after breakfast he hesitated outside Andru’s office door. It’s not that I doubt Tevera’s word, he told himself, it’s just that Andru’s older, more experienced. He may know something she doesn’t.

Finally he knocked diffidently. “Enter,” Andru said, and Kriss pushed the door open and looked in. The innkeeper sat before his computer, eyes flicking over the display. “What is it?” he said without looking up.

“May I talk to you, sir?”

“In a moment. Sit down.”

Kriss sat in the wooden chair and waited. After a few uncomfortable minutes Andru touched the control pad and looked up. “Yes?”

“I want to ask you something about—uh, starship crews.”

His employer raised an eyebrow, but nodded.

“Someone told me last night that only Union or Family members can get berths on starships. Is that true?”

“It’s true,” Andru said flatly.

Kriss slumped. “Then I should have stayed in Black Rock,” he muttered.

“Anything else?” The innkeeper looked down at his screen again.

On impulse, Kriss said, “Yes. What do you know about the Family?”

Andru’s head snapped up, eyes glaring. “Get out,” he growled. Kriss sat frozen with shock, and Andru rose, fists clenched. “Get out!” He started around the desk.

Kriss scrambled up, his chair clattering to the floor, backed to the door, and fumbled his way through it into the corridor. The door slammed in his face. Heart thudding, he leaned against the paneled wall and took a couple of deep breaths. What had brought that on?

He remembered the words of the innkeeper who had first told him about Andru. “He’s a strange man, with a whipcrack temper.” For the first time, he’d seen evidence that was true.

He spent the rest of the day at loose ends. He didn’t want to see the spaceport, not after what he’d learned. He did want to see Tevera, but plainly that was impossible. Instead he wandered the streets, kicking at bits of trash and brooding. When he returned to Andru’s that night he doubted he could play anything worth listening to, and he really didn’t care. He picked at his supper, slouching in his chair and glaring at the crowd in the common room with a dull mixture of anger and self-pity. Every one of them is either Union or Family, he thought. They can go anywhere in the galaxy. Some of them probably don’t even like it. They’d love to settle down on a nice quiet planet like this, while I want to leave and can’t. It’s not fair!

When he took his place by the fire his music began harshly, with angry discords that drew frowns from the listeners and a black look from Andru. But almost instantly, with frightening speed and intensity, he felt the instrument’s ghostly fingers in his mind, brushing aside depression and anger and touching the dream at the core of his soul, the dream that, despite everything, lived on.

When the music died he raised his eyes to a room so silent the crackle of the fire seemed an intrusion, and Tevera’s strange words about projected emotions came back to him. Could it be true? Certainly the offworlders seemed to share something of what he felt. He saw a young man not much older than him surreptitiously wiping his eyes.

But he didn’t see Tevera, or the man who had attacked them; and if their mysterious rescuer were on hand, he had no way of knowing.

When he took the money bowl to the bar, he handed it to Andru a little hesitantly, but the innkeeper gave no hint of his morning rage. He simply divided the credits and said, “Good job.”

It’s as if nothing happened, Kriss thought as he climbed to his room later. It’s as if it were my first night here.

That day set a pattern for the next two weeks: nothing happened. No sign of Tevera, their attacker, or their rescuer. No suggestion from anyone that he might ever find his way into space. And every night he played, and every night it seemed the touchlyre dug a little deeper into his soul, and his music moved his listeners a little more.

During the days, Kriss systematically explored the city, from the primitive suburbs to the glittering but half-empty center to the sordid, run-down section on the other side of the spaceport from Andru’s, a place where shadows lurked even in daytime between tall buildings leaning drunkenly toward each other.

Yet even Stars’ Edge, so strange and wonderful when he first saw it, began to pall as the days passed. At night, lying in his bed, Kriss spun an elaborate fantasy in which his parents proved to be important people in the Family, and Tevera escorted him triumphantly to her ship. But it remained fantasy; he began to think Tevera had broken their agreement, and toyed with the idea of telling Andru about their meeting and the attack on them outside his inn that night, in the spiteful hope the news would get back to Tevera’s ship and she would be punished.

Then, just when he had made up his mind he wouldn’t see her again, she returned.

She entered one night while he played, so that when he looked up at the end of the performance, he saw her waiting by the door, her face white and strained above the high collar of her blue crewsuit. She jerked her head toward the door and went out.

When he could he followed, searching the street carefully before crossing to the alley. He saw no one, but stepping into the dark passage where he had once been attacked still made him feel unpleasantly vulnerable. “Tevera?” he whispered as he rounded the corner into darkness.

“Here,” she said, and he felt her light touch on his arm.

“I’d about given up on you.”

Her touch vanished. “I promised I would help you. No one in the Family breaks a promise.”

He bit off a hot retort. He hadn’t waited two weeks to see her again so he could start an argument. “What did you find out?”

“Only one couple named Lemarc disappeared in the time period you outlined—at least, only one was recorded in the Commonwealth Library.”

“My parents!” Kriss’s pulse raced.

“Maybe.” He heard rustling, and a moment later a tiny light clicked on in Tevera’s right hand, lighting a sheet of paper in her left and also dimly illuminating her face. “I’ll just read this to you. It’s a transcript of a news report. I made a hard copy so I could erase the file from my data storage.” She held the light close to the paper. “Jon and Memory Lemarc, extraterrestrial archaeologists, were officially declared missing today by the Commonwealth Space Force when their scheduled monthly report became two weeks overdue.

“The Lemarcs, who were funded by an anonymous wealthy patron, kept the location of their research secret, making a search impossible. Although their patron may know where they were working, the Space Force has been unable to identify him.

“Anyone having any information about the Lemarcs’ whereabouts is asked to contact their local or planetary police or the Commonwealth Space Force directly.” She stopped.

“There’s nothing else?” Kriss asked after a moment.

“That’s all I can tell you. I tried to access any personal files they might have left in the Library, but everything was privacy-locked.”

“What about this mysterious patron?”

Tevera sighed. “Kriss, I really tried, but no luck. What I read you is all I know.”

“My parents died on Farr’s World. Could they have been doing research here?”

Tevera folded the printout and slipped it into her pocket, but left the light on, setting it on a window ledge close at hand. “The only ancient remains here are fish fossils. We’re the first civilization on this planet. Even the vanished spacefaring races we find traces of from time to time never came here.”

“They probably didn’t have much use for it,” Kriss muttered. He tried the names Tevera had given him on his tongue. “Jon and Memory Lemarc. Jon and Memory…” He glanced at Tevera, barely visible in the glow from the little light. “Did you find out where they’re from?”

She hesitated a moment. “Earth,” she said finally.

“Earth!” He swallowed. Passage to Earth would cost not just thousands but tens of thousands of feds, and even then he couldn’t be sure of getting to the planet’s surface. It was like Tevera had told him about the Union: you had to have connections.

Or else… “But then…then I’m an Earth citizen!”

Tevera shook her head. “It’s not that simple. How can you prove it? You have no real evidence Jon and Memory Lemarc were your parents. Earth authorities are used to people trying to bluff their way onto the home planet. They’ll never believe you.”

She’s right. He leaned heavily against the wall. Another dead end. He gazed up at the narrow strip of star-studded sky visible between the buildings and wondered if the whole galaxy were against him. “So now what?” he said to the distant, uncaring constellations. “I can’t join a crew, I can’t afford to buy passage, and even if I could they wouldn’t let me land!” He felt like a hand were closing on his throat, choking him, and he fought through it to cry, “Do I have to spend the rest of my life here?”

His shout echoed away to silence. Tevera stepped closer. “Don’t give up! You can still get off this planet. Buy a short passage somewhere else—Estercarth, or Dunnigan’s Doom, anywhere. Your instrument is your ticket. People will pay to hear you play wherever you go!”

“But it’s not just the travel!” He turned to her. “I want to see what’s out there, but I…” The words choked off. “I don’t want to see it alone,” he finished in a whisper.

She took his shoulder and turned him toward her. Her cool fingers slid down his arm until they clasped his hand. “I know how you feel,” she said.

Kriss didn’t dare move. His body tingled at her touch. “How can you?”

“Three years ago an on-board explosion damaged the Thaylia, and killed three people. We limped to the nearest planet, an inhabited but low-technology world like this one. Without proper facilities, it took us a long time to repair the ship. For almost a year we lived on that planet, like the ‘worldhuggers’ we claim to despise.

“Most of the Family stayed close to the ship, with only brief forays into the city. But I went everywhere, saw everything I could—mountains, seas, prairies, forests; cities and farms and villages.” She paused, her hand warm around his. “I saw a lot of beauty, Kriss. I’d lived on-planet once before, briefly, when…when my parents were still alive, but I was very small then. This time, for the first time, I realized there is something to be said for ‘worldhugging,’ that there can be other ways of living just as worthwhile as ours. Ever since I’ve seen planets differently, as more than just places where we unload and pick up cargo and make money off gullible worldhuggers.” She squeezed his hand tighter. “That’s why I know how you feel. No one else on the Thaylia feels the way I do, Kriss. They’d be shocked to hear what I just told you. I’ve seen a hundred different worlds—but even though I’m surrounded by my Family all the time, I’ve seen them alone.”

Kriss, without really knowing how it had happened, found he had his arms around her, her head resting on his chest. For a long time they simply stood that way, Kriss feeling happy and sad and awkward, all at the same time. He felt as if he held a rare, fragile sculpture, afraid he might break it, yet at the same time wanting to hold it close and tight and make the moment last forever.

But of course it couldn’t, and at last Tevera pushed herself away. “I have to go,” she said softly. “Before someone finds us together.” She switched off the light, but starlight still glittered in her eyes when she looked back at him.

Unable to speak, he nodded. Hand in hand, they walked out into the light, where she turned and thrilled him with a light, sweet kiss before breaking away and starting toward the spaceport.

“Tevera!” The harsh voice from across the street demanded obedience. “Stay where you are!”

She whirled and gasped. One of the young men who had been with her the first night in Andru’s strode toward her. “Rigel!” she cried.

Kriss clenched his fists and moved forward, but Tevera stopped him with a hand on his forearm. “Don’t, Kriss. He’s my brother.”

Kriss lowered his fists, but didn’t relax.

Rigel stopped a few feet away and glared at his sister. “Return to the ship, Tevera. You are confined to port for the remainder of our stay on this planet. And once I report to Captain Nicora…”

Tevera gave Kriss one last, agonized look, then fled. He took an involuntary step after her, but Rigel stepped in front of him. “You are no doubt unaware of our law prohibiting close contact between the Family and planet-dwellers,” he said in a voice like ice. “But be warned now: we begin by punishing our own, but if necessary we can deal with you, too.” He took a step closer. “And as Tevera’s brother, I swear—leave her alone, or we will deal with you!” He spun and strode toward the spaceport.

In his fury Kriss hardly heard the threat. “Tevera! Come back!” he shouted into the night.

Not even an echo answered.

#

Chapter 8

For an hour Kriss walked the streets, blaming himself. He should never have gotten Tevera involved! Now I’ll never see her again—and she’ll never forgive me! He could still feel the touch of her lips on his. He could hardly bear the ache in his heart. When at last he returned to Andru’s and went upstairs to his bed, the room closed around him like a trap from which he could never escape. He had lost his only contact with the universe beyond Farr’s World.

It took him a long time to fall asleep.

The thunder of a rocket jolted him awake. He jerked upright, heart pounding, then recognized the noise, threw off the covers, ran to the window and banged open the shutters, sickly certain that the Thaylia was leaving.

But no, the roar didn’t fade, it grew louder. A fifth starship was coming to Farr’s World.

His first impulse was to dress and rush to the port, but his excitement died as the night’s events swept down to roost like black starklings. “Why bother?” he muttered. He slammed the shutters shut, and crawled back into the sweat-dampened, wrinkled bed, where sleep mercifully reclaimed him.

Shortly after noon he finally got up and went downstairs, not rested, but unable to stay in bed any longer. He sat at his usual table and stared glumly out the window at the sun-drenched street. A groundcar buzzed past, its choking exhaust fouling the fresh breeze.

“I wondered if we would see you today,” Zendra said cheerfully behind him. “You’re too late for breakfast, but I can still get you lunch.”

He didn’t even look at her. “I’m not hungry.”

She circled the table to stand between him and the window; he looked down at his hands, lying listless on the dark wood. “Don’t you feel well?”

“No.” True, though not in the way she meant.

“I thought so. I told Andru there must be something wrong with you when you didn’t come dashing downstairs the moment that ship landed this morning.” She paused. “You did hear it, didn’t you?”

“Yes.”

“Well, you should see it, too! It’s a tiny thing, barely half as tall as even that Family trader, and gold as a sunset.” She lowered her voice and leaned toward him. “Rumor is it belongs to Carl Vorlick.”

“Who?” The question emerged before Kriss remembered he wasn’t interested.

“Carl Vorlick. Vorlick Interstellar? United Galaxy Spaceways? Pleasure Planets, Inc.?”

Kriss shrugged. “Never heard of him.”

“Black Rock must be even more isolated than I thought. He’s only one of the richest men in the Commonwealth—always in the news.”

“Then what’s he doing on a nothing planet like this?”

Zendra laughed. “Oddly enough, he didn’t tell me. Probably here to see our own local tycoon, Salazar. They’re two of a kind, from what I hear. Buying and selling, that’s all they care about, never mind who loses their job or home. You know Salazar was in here a few days ago trying to buy Andru’s?”

“The inn?” That startled Kriss out of his lethargy. “Why?”

“Who knows? He already owns a bunch of so-called ‘inns’ south of the port.” Her voice dripped disapproval. “You can get anything you want over there, they say. Anything at all. But maybe Salazar wants a place over here, closer to the main gate. A respectable place.”

Kriss remembered his one sojourn into the area south of the port, and shuddered. “Why don’t the police do something about those places?”

Zendra snorted. “Salazar owns the police, too—or at least enough of them to do what he wants.”

“And Vorlick is just like that?”

“Probably worse. Salazar buys and sells factories and businesses and corporations—and the lives of the people involved with them—here on Farr’s World and a couple of other nearby planets. Vorlick buys and sells whole planets, all over the Commonwealth.” Her tone turned businesslike. “But this is no time for gossip. If you don’t feel well then soup is the thing for you. Think you could get some down?”

He nodded, then thought of something. “Andru—he didn’t sell, did he?” If Andru sold the inn, he’d lose his job and his last tenuous link with the stars…

“Andru wouldn’t sell to Salazar if the alternative were being roasted alive on our own barbecue spit,” Zendra said. “Right. Soup and hot stimtea. That’ll pick you up.” She hurried off.

Kriss shook his head. Nothing could pick him up.

But supper the night before had been a long time ago, and despite himself his mouth watered when the soup was set in front of him, steaming and spicy, with fresh-baked bread on the side. He polished it off and even drained the cup of stimtea, a strong green drink he normally avoided. When he was done he felt a little better, though the bitterness of the tea lingered in his mouth. He decided he would go take a look at the new ship, after all.

He hardly dared to admit, even to himself, that he also hoped to glimpse Tevera.

The moment he came out onto the road circling the spaceport he saw the new ship, nearer the perimeter fence than any of the others. Sleek, needle-prowed, glittering in the sunlight, it put its scarred and tubby gray neighbors to shame.

A ramp extended from a small hatch near the base, and four people stood near one of the landing supports, talking. One of them, a short man whose bald head and silver-braided uniform both shone, Kriss thought was the portmaster. Beside him stood another Farrsian, a woman, probably his assistant. One of the remaining two, tall and fair-skinned, was obviously an offworlder, but the fourth was even shorter than the portmaster. From his complexion Kriss thought he must be an offworlder, too, but he wasn’t certain. The tall offworlder struck him as familiar for some reason, but he had his back turned and the intervening traffic prevented Kriss from getting a good look at him. As he watched, all four moved up the ramp into the starship.

Kriss looked both ways along the road, thinking he would cross and get a better look—and spotted the big man who had attacked him and Tevera two weeks before, standing near the fence, eyes on the golden ship. Heart racing, Kriss ducked behind a parked groundcar and knelt there. A passing woman looked at him suspiciously, but to his relief didn’t stop or say anything. When he finally poked his head up again, the big man was gone.

He headed for police headquarters. Enough was enough, and the reason for keeping the attack secret had vanished when Tevera’s brother had seen her with Kriss the night before. She could hardly be in worse trouble if her Family found out it hadn’t been their first meeting; by now she’d probably told them herself.

He walked with his head down, watching the ground and thinking hard. Why was his attacker so interested in the golden ship? Had he sent for reinforcements? Did he work for this Carl Vorlick that Zendra seemed to think he ought to know about?

He glanced up to get his bearings—and froze. The big offworlder was just emerging from the police tower, only a few yards away. He saw Kriss and showed his teeth in a savage grin.

After one heart-stopping moment, Kriss turned and ran, darting into the nearest alley and zigging and zagging his way through back streets until he finally had to stop, gulping huge lungfuls of dank, garbage-fouled air. He listened, but heard no running footsteps in pursuit; and slowly he made his troubled way back to Andru’s. Why hadn’t the man chased him? The only answer he could come up with wasn’t very comforting—that his attacker had a surer way to get what he wanted than nabbing him in full daylight.

He couldn’t go to police with the stranger watching their headquarters. Nor did he see how he could talk to Andru, not after the way the innkeeper had exploded when he’d asked about the Family. Andru seemed to hate the mysterious spacefarers—he might throw Kriss out of the inn altogether if he found out he’d been involved with the crew of the Thaylia, and if that happened, he’d be at the mercy of all his enemies…

…whoever they are.

Wait, he told himself as he climbed to his room. Just wait and see. If that golden ship is connected to this whole mess, then something else is going to happen very soon. Maybe then I’ll be able to sort out what I should do.

He descended to the common room that night to find it packed to the rafters with offworlders and, to his astonishment, even a few Farrsians. Sweet and foul smoke of a dozen different weeds from as many planets filled the air, mingling with the strong odors of offworld food and drink. The clink and rattle of glasses and dishes formed a counterpoint to the murmur of voices, some speaking languages from planets hundreds of light years from Farr’s World. Kriss drank it all in with every sense, thinking bitterly that the sights, smells and sounds of Andru’s might be as close as he could ever come to the myriad worlds of the Commonwealth.

“Feeling better?” Zendra asked as she brought his supper to him at the bar.

He nodded.

“Good! I hoped you would be, so I brought you something a little more substantial than soup.” She lowered her voice. “Keep your eyes open tonight. I hear Vorlick himself may be here.” She put her finger to her lips, winked, then spun in a swirl of skirts and returned to the kitchen.

Kriss turned and slowly scanned the room. Many of the faces were familiar, but every night there were a few new ones. None of them looked particularly wealthy, but then, he doubted this Vorlick would advertise his riches, especially not in a city like Stars’ Edge.

He shrugged and attacked the roast darbuk Zendra had brought. Andru motioned to him just as he finished eating. He gulped down the last of his iced frenta juice, then headed for the platform, unwrapping the touchlyre as he walked. As Andru introduced him he laid his fingers on the copper plates and the strings hummed to life; and as he closed his eyes, he felt the touchlyre reaching into his mind more powerfully than ever.

This time it exposed more than just his dream of traveling into space. This time it bared even those feelings he had tried to hide from himself—pain, guilt, the beginning of despair; fear, confusion and bewilderment. Tevera had said hearing him play the instrument was like seeing him standing in front of the crowd naked to his very soul, and for the first time, that was the way it felt to him, too, as if his innermost being were being stripped bare for everyone to see—including himself.

I’m not playing the touchlyre, he though in one passing moment when, for an instant, he was dimly aware of himself. The touchlyre is playing me. Then it plunged him back into the music.

When he surfaced at last, as if from a deep green pool, his whole body shook. For a long moment he sat with eyes closed and head bowed, trying to compose himself before facing the audience. When at last he looked up, he saw his pain mirrored in every face; then offworlders and Farrsians alike crowded forward to drop feds into his bowl.

It should have cheered him to think they understood what he felt…but instead he began to understand Tevera’s near-anger when she’d first told him her feeling that the touchlyre projected, not just sounds that conjured up emotions in his listeners, but the actual emotions themselves. If that were true, he was manipulating these people, using them as he had tried to use Tevera; and abruptly he got up and took the money bowl to the bar, roughly shoving the touchlyre back into its wrapping while Andru counted the feds. As he pulled the leather thongs tight he sensed someone behind him, and turned, finding himself face-to-face with an offworlder.

Shorter than Kriss, short even for a Farrsian, the man emanated a sense of power and control that belied his lack of height. He smiled, showing even white teeth in a tanned, fine-lined face, but the smile did not warm his ice-blue eyes. “Kriss Lemarc?” High-pitched and soft, his voice nevertheless carried an undertone like sharpened steel.

Kriss nodded uneasily.

“May I speak with you in private?”

Kriss felt he should not talk to this dangerous man in private, or in public either, but… “Is that your ship that came in this morning?”

The man nodded.

Carl Vorlick!

“Then I’ll talk.” He tried to sound self-assured. “Where?”

“What could be more private than the streets of Stars’ Edge at night?”

“Out front, in ten minutes?”

Vorlick—if it really was he—inclined his head. “Ten minutes.” He turned and crossed the crowded room, sidestepping people like a cat avoiding puddles in the street.

Andru’s face bore no expression when Kriss turned back to him. “Two hundred fifty-seven feds,” he said. “Do you want any of it now?”

“No, put it away.” On impulse, he handed the touchlyre over the bar, too. “And put this with it. I don’t want to leave it in my room tonight.”

Andru accepted it without surprise. “As you wish.”

“Thank you.” Dry-mouthed, Kriss turned toward the door—and the stranger waiting beyond it.

January 11, 2013

Bundoran Press buys my SF novel Right to Know

I’m very pleased to announce that Bundoran Press, a small Canadian press that’s put out some terrific books in its short life and has a new owner and managing editor, Aurora Award-winning author Hayden Trenholm, has bought my science fiction novel Right to Know (that’s the working title–it could still change), with the goal of having it out by August, in time for the When Words Collide conference in Calgary.

I’m very pleased to announce that Bundoran Press, a small Canadian press that’s put out some terrific books in its short life and has a new owner and managing editor, Aurora Award-winning author Hayden Trenholm, has bought my science fiction novel Right to Know (that’s the working title–it could still change), with the goal of having it out by August, in time for the When Words Collide conference in Calgary.

Here’s how Hayden describes the book in his press release:

Edward Willett’s novel, Right To Know (working title), is a fast-paced space opera about the power of information – and disinformation – in closed societies and whether the public has a ‘right to know’ the plans and strategies of their governments in times of conflict.

It’s a book that’s been seeking a home for some time, so I’m thrilled it has found such a good one. I’ll keep you posted with cover art and launch information and sample chapters as publication date draws near!

Two songs from The Dragonslayer

Many years ago I took it into my head to turn a short story of mine, “The Dragonslayer, “into one-act stage musical, intended for high schools. In brief, it was about a teenager who was a whiz at killing dragons when playing Dungeons & Dragons, who gets called into an alternate world to deal with a real dragon after a demon mistakes his roleplaying abilitiy for real-life ability.

Many years ago I took it into my head to turn a short story of mine, “The Dragonslayer, “into one-act stage musical, intended for high schools. In brief, it was about a teenager who was a whiz at killing dragons when playing Dungeons & Dragons, who gets called into an alternate world to deal with a real dragon after a demon mistakes his roleplaying abilitiy for real-life ability.

I still haven’t written it.

However, I just came across two of the song lyrics I wrote for it, and spruced them up a bit just for fun.

And here they are!

The Wizard’s Song

I am the Wizard

The singular Wizard

The proper-noun Wizard

I’m one of a kind.

I’m master of monsters,

A changer of skins,

I like to throw fireballs–

It helps me unwind.

I’ve made princes tremble and quiver with fright,

I’ve wiped out whole kingdoms with hail and blight.

It wasn’t for money or some little slight

That they’d done to me—no, I just did it for spite!

For I am the Wizard

The singular Wizard

The proper-noun Wizard

I’m one of a kind!

(He steps into the pentagram on the floor.)

I call on rain and thunder and the mighty winds that roar,

I call on fire and flood and things that lurk outside the door,

I call on hell and heaven and the seven planes between,

To things that have not been, and never must be ever, seen.

I call to creatures that, within a nightmare, set men screamin’…

I call, I call, I summon you, to come and serve me–DEMON!

(The DEMON appears.)

Here is the task I set for you, oh creature of the night.

Fly forth from here and search the worlds that lie behind our sight.

Seek out for me a warrior, one of such exceeding might,

That he can rid our land of this abominable plight.

Bring back for me an answer to the Lord King’s fervent prayer:

Bring back to me a man to be our Kingdom’s DRAGONSLAYER!

(The DEMON departs.)

Yes, I am the Wizard

The singular Wizard

The proper-noun Wizard

I’m something to see.

(Nothing is happening, but the song continues.)

Um…

I control demons

I can … um…grow leemons

Marvellous leemons

Just for your tea.

I–

(The Demon returns.)

Thank goodness!

***

The Good Knight Song

Once upon, upon a time

There was a very special knight.

A knight who wore a metal suit

And fought for the right.

The knight lived in a castle grim,

As all good knights are wont to do,

Why, if you were a real good knight,

You’d live in one too.

This knight rode out one sunny day.

And as he rode the day away

He came upon a scary sight:

A dragon in flight.

The worm came down and landed in

The road that was in front of him

And roared at him and threatened to

Burn all his hair white.

But the good knight wasn’t fearful,

No, the good knight wasn’t scared;

(No, the good knight wasn’t stupid!)

Instead he just glared.

For the good knight had a long pike,

Made of sharpened steel and pine,

And he warned the worm, “I’ll stick this

“Where the sun don’t shine.”

Then the dragon thought over,

Said, “I’m just not in the mood

“To fight an armored warrior.

“And I don’t like canned food.”

Then he spread his wings to fly,

But the good knight, pike to fore,

Spurred his steed, and through the dragon

The steel point tore.

Now the dragon’s head’s a trophy

That hangs just above the door,

And his hide’s a shiny rug of scales

Covering the floor.

And the good knight’s many visitors

Never the see the little hole

He keeps tucked under the sofa:

The hole made with his pole.

January 10, 2013

Why books are better than the movies made from them

My 11-year-old daughter Alice and I, during a before-school stop in a coffee shop this morning, were discussing books that have been made into movies: specifically The Hunger Games, which won several People’s Choice Awards last night.

“Why are the books always so much better than the movies?” asked Alice.

A question for the ages.

From her point of view, what’s wrong with movies is that they leave stuff out. She loved the look of the Harry Potter movies— but she didn’t like the changes they made to the story.

but she didn’t like the changes they made to the story.

That’s certainly one problem people have with movie adaptations of their favorite books. It’s the problem I have with The Lord of the Rings movies. We watched those together just after I finished reading the books out loud to Alice, and maybe because the books were so fresh in my mind, I found the changes made for the movies more glaring and annoying than when I saw the movies in the theatre. (The treatment of Faramir, the decision to make Gimli comedy relief, the absence of the Scouring of the Shire, the Army of the Dead coming all the way up-river with Aragorn instead of Gondor’s human allies arriving in the black ships, the ridiculously giant elephants, etc., etc.)

But I think that’s just a symptom of the real problem.

What it really comes down to, I think, is that books are active, and movies are passive.

Books consist of nothing more than words on paper (or on a screen): just words. The author has, within his or her mind, ideas, images, characters and emotions he or she wishes to convey to other people, and has chosen the words he or she thinks can accomplish that task.

But the author cannot control, or even really know, what ideas, images, characters and emotions those words will conjure in someone else’s mind. I know exactly what Mara, the lead character in Masks, my next book for DAW, looks like; I can see her world clearly in my mind, I know how she feels about things and how she will react to the people and events around her.

Yet when you read the book (you will read the book, won’t you?), you will have a very different image of her and her adventures. To you, your mental images will be the “right” ones.

Well, you know what? You’re absolutely correct. They are right. That’s because the story in a book is created not only by the author who writes it, but by the reader who reads it. It’s a collaboration—no matter how annoying that collaboration may sometimes be for writers who discover, from the reactions and comments of readers, that what people got out of the book wasn’t really what was intended.

(I remember a story from one of Isaac Asimov’s autobiographical books—probably Opus 100—in which he described sitting in on a university class in which his class science fiction story “Nightfall” was being discussed. After the class, he went up to the professor and said, “That was very interesting, but I’m Isaac Asimov. I wrote that story, and I didn’t put any of that stuff in there.” To which the professor replied, “I’m very glad to meet you, but just because you wrote it, what makes you think you know what is in it?”)

Movies, of course, are also collaborative, but in a different way. In movies, the collaboration is among the writers, director, actors, set designers, makeup people, costume designers, etc., etc. The end result is a combination of many different people’s ideas of what a particular story should look like…but once that result is produced, it is static. That movie will always look that way (unless George Lucas made it and decides to stick in new special effects somewhere down the road…and, yes, Han shot first!), and it will look the same to every viewer.

So the biggest reason books are almost always better than movies? The story in your head can run as long as it needs to, has an unlimited special effects budget, is filled with real people rather than with actors pretending to be those people…and best of all, is produced and directed by you.

It’s a rare movie that can compete with that.

January 9, 2013

My introduction to science fiction for non-SF audiences

I’ve occasionally been called on to talk to various groups—teachers, librarians, others—about science fiction. It’s an interesting challenge, since you can’t be sure that your audience knows the first thing about the topic.

I start, of course, by establishing my bona fides: talking about my own writing and publications. Then I go on to say something like this…

First, I need to deal with the question, “Why do you  write that stuff?” It sometimes seems that, like Rodney Dangerfield, SF “can’t get no respect.”

write that stuff?” It sometimes seems that, like Rodney Dangerfield, SF “can’t get no respect.”

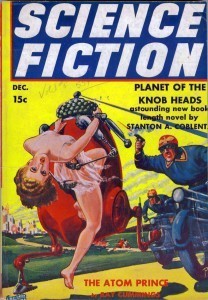

Though the situation is better than it once was, there has been a well-documented tendency over the years for “serious,” “literary” writers, editors and critics to look down on science fiction as something childish and inferior. (Looking at the accompanying image from one of the lesser “pulp” magazines of the 1930s, it’s perhaps not hard to see where that tendency came from…)

For SF readers, this attitude becomes amusing when one of these “serious” writers decides to write a novel set in the future, extrapolating from the present (the very essence of science fiction) and then hastens to assure everyone (as does his or her publisher and every critic that reviews it) that what he or she has written absolutely is not science fiction–even though those well-read in the SF field know that the writer has simply rehashed (and not as well as they were originally hashed) ideas long since explored by SF writers.

(Margaret Atwood is sometimes guilty of this, having infamously dismissed SF as “talking squids in outer space” while insisting that her futuristic novels The Handmaid’s Tale and Oryx & Crake are not SF—when, of course, by any reasonable definition of the term, they are. But I don’t want to be too hard on Atwood: she really does have affection for and understanding of the genre—she just also understands that the literary world sees it as a bit of a ghetto, and she understandably doesn’t want to be consigned to it.)

Condescension, ignorance and insult from literary types has led to a corresponding backlash among some SF fans and writers against mainstream stories, which are stereotyped as plotless, pointless character studies that fail to understand or deal with some of the most powerful forces shaping our world: the advances in science and technology.

Personally, I believe there is good writing to be found in every genre, from literary to SF to mysteries to romances, and the walls between them are artificial creations of publishers, marketers, critics and academics. I believe equally strongly there is bad writing to be found in every genre, some of it produced by the most well-respected writers and publishers. As Theodore Sturgeon, himself an SF writer (and a very good one) put it, “Sure, ninety percent of science fiction is crud. That’s because ninety percent of everything is crud.”

So I’ve never felt I was lowering myself to write SF and fantasy. Quite the contrary; writing fiction strictly about the here and now, or the recent past, seems incredibly limiting to me; it’s like typing while wearing a strait-jacket. SF and fantasy allow my imagination free rein; any time in the past, the present or the distant future and any place in this universe or any other are available to me as settings; creatures both human and non-human are at my beck and call to serve as characters; and there is no idea so outré that it cannot be couched in SF terms and turned into a story.

SF writers often speak of “the sense of wonder.” That’s what the best SF and fantasy appeals to.

What is science fiction? Well…it’s not as easy to define as you might think. Norman Spinrad says “SF is what SF editors buy,” but that just puts the definition off on the editors. The aforementioned Theodore Sturgeon said, “When science is so integral to the plot that the story falls apart without it, it’s a SF story.” Robert Heinlein, paraphrasing Reginald Bretnor, stated that it’s “that sort of fiction in which the author shows awareness of the nature and importance of the…scientific method,…of the great body of human knowledge already collected…,and takes into account…the future effects on human beings of scientific method and scientific fact.”

Science is obviously a part of science fiction, or it wouldn’t be called science fiction, but it’s important to remember that the word “science” is being used in a broader way than might be expected. In fact, rather than chemistry or physics or biology, the science perhaps most often seen in science fiction stories is sociology, if that is taken to include history, economics, mob psychology, and combinations of the above.

Of course, the hard sciences are frequently featured, too. But whatever the science content, the most important part of that last definition for me is that science fiction “takes into account…the future effects (of science) on human beings.”

Good science fiction forces the reader to engage his or her brain. Part of the pleasure of reading science fiction is picking out the background assumptions which are behind the plot, finding the connections between a strange new world (even if that world is called Earth) and our own, and thinking about what will happen next, even after the story is done. Good science fiction is an incitement to deep thought about a story, the ideas it contains, and the issues it concerns.

My friend and former writing instructor Robert J. Sawyer, Hugo and Nebula Award-winning science fiction author (and certainly Canada’s best known writer in the field), says that “SF writers themselves argue this question (what is SF?) all the time, but here’s one good definition: science fiction is a laboratory for thought experiments about the human condition; it lets us examine what it means to be human in ways that we simply can’t in real life, because it would be unethical or impractical to conduct the experiments. Using literary devices such as displacement in time or space, or metaphorical others who let us exaggerate or isolate parts of the human psyche, science fiction allows us to see ourselves from odd angles, catching glimpses of truths that might otherwise be hidden from view. “

“Thought experiments about the human condition,” of course, could be used to describe ordinary fiction, but it seems to me that most ordinary fiction does not sufficiently address the fast-changing nature of the world in which we live.

I like to call science fiction an inoculation against future shock. Every day, the world changes. And one change leads to another, often in ways you wouldn’t expect. The automobile, spaceflight, television, computers…all changed society in ways no one expected. Including science fiction writers. But science fiction writers at least recognized the central role scientific and technological change has in shaping our world, and readers of science fiction, though perhaps startled by the way in which some of these changes played out, at least weren’t startled by the fact that things changed.

In Star Trek IV, where the crew of the Enterprise journeys back in time to 20th-century San Francisco, a woman asks Captain Kirk if he’s from outer space. He says, “No, I’m from Iowa. I just work in outer space.”

An SF writer could say, “I’m from the present. I just work in the future.”

January 8, 2013

2012 through the first lines of my blog

A quick meme for today, which I picked up from Norman Geras: the first lines of the first blog posts for each month of 2012…which in my case tend to be science columns!

A quick meme for today, which I picked up from Norman Geras: the first lines of the first blog posts for each month of 2012…which in my case tend to be science columns!

When the first post happened to be one of my Saturday Specials, where I posted some bit of the many different types of writing I’ve done over the years, I’m giving the first line of the posted writing sample, not the introductory bit I wrote in front of it.

Maybe you’ll see something you missed. Here’s your chance to catch up!

Enjoy, and look forward to lots more in the already not-so-new year…

January: Delayed once more by festive cheer, I make my first post of the year!

February: Most of the time, we don’t really want other people to know what we’re thinking.

March: Sometimes people ask me why I like to write about science.

April: On Saturday afternoon, June 17, 1967, a band with the unlikely name of Big Brother and the Holding Company took to the stage of the Monterey International Pop Festival at the Monterey County Fairgrounds, eighty miles south of San Francisco.

May: On January 13, 1968, a gray, gloomy Saturday, Johnny Cash entered Folsom State Prison in Repressa, California.

June: Cumberland House, founded in 1774, is the oldest permanent settlement in Canada west of Ontario.

July: There’s a public perception that somebody must be pulling the strings on gas prices, that somewhere in some shadowy secret lair mustache-twirling oilmen are gleefully conspiring to raise prices across the board just in time for summer holidays.

August: While I was browsing for another Olympic-themed column idea (as promised last week) one story particularly caught my eye: a Reuters piece by Kate Kelland headlined (in the Regina LeaderPost, at least), “Scientists skeptical as Olympic athletes get all taped up.”

September: Most people plan their summer vacations based on places they’d really like to go or people they’d really like to see.

October: I’ve sung all my life, in church, in choirs, and on-stage, both just for fun and professionally.

November: It’s always a mistake to make a grand pronouncement that one is going to make a valiant attempt to post regularly to one’s blog again, especially after having made similar grand pronouncements in the past and then not following through, but…

December: We’re coming up on the shortest day of the year in the northern hemisphere: at the latitude I live at, in Regina, Saskatchewan, that means that today the sun rose at 8:49 a.m. and will set at 4:54 p.m.