Claire Hennessy's Blog, page 21

September 10, 2015

Book review: Immaculate

Katelyn Detweiler – Immaculate

Katelyn Detweiler – Immaculate

There are books you come across unexpectedly and know immediately that you must have right now. Katelyn Detweiler’s debut novel offers up a question that will instantly pull in anyone who’s been through a Catholic education (particularly, perhaps, those of us who resented it) – what would happen if there was a real-life virgin pregnancy in today’s world?

Seventeen-year-old Mina, or ‘Meenius’ the genius, plans to spend her senior year maintaining her perfect grades, continuing to date her longterm boyfriend Nate, and hanging out with her two best friends before college separates them all. Instead, after a mysterious message from an old woman named Iris, and an inexplicably intense dream of fireworks and bright lights, Mina discovers she’s pregnant. She knows she can’t be – she’s never had sex, not even close – but at the same time she knows she must be. And that this baby is special.

Her mother believes her. Her father is sure she’s lying, that his perfect daughter has made a mistake she can’t admit. Her younger sister is excited. Nate hates her, and quickly dumps her, convinced that she’s cheated on him. And while one of her best friends stands by her, the other agrees with what most of the community – and later the media – believe: Mina’s lying.

This is a novel about a miracle: not one that fits in with what the Church wants, and not one that manages to be explained by science. Much as I would have loved some more scientific attempts to explain the pregnancy and the special nature of the child (I very much want a sequel in which we discover that the child’s blood cures cancer because of its unusual conception), the focus here is on faith, on believing in intuition and the people you love. And aside from this one element, the rest is pure realism: the cruel reactions of Mina’s classmates and later her opponents, as the story about the pregnant virgin spreads to the national media, are one hundred percent believable.

As a novel about teen pregnancy, it mostly handles the issue of choice well; there is a slightly shudder-inducing part where Mina describes herself as a ‘vessel’ and ‘human incubator’ in a positive way, which I found unsettling. But abortion is addressed, and it’s clear that it is a choice she might have made in other circumstances, if she and Nate had slept together. Mina chooses not to have an abortion or to give the baby up for adoption, and she has also said yes to this child, despite the unusual circumstances.

Immaculate is a tricky novel: spiritual enough to be off-putting for some, not sufficiently religious or perhaps sacrilegious for many others. I found it a thought-provoking read about a girl faced with a situation she never imagined but nevertheless embraces and defends. But it is also very much about faith and belief, and what happens when these beliefs don’t fit into neat or tidy boxes.

September 6, 2015

This is not abstract

I read this piece this morning.

Women like Tara shouldn’t need to tell their own stories to make a point. She’s smart and funny and wise on the matter, and has been for years. I was lucky enough to be at an event with her at the start of the year where she had a great piece on how this country only values women if they’re… baking.

People’s medical and life decisions are their own business. Or they should be. The trouble is that Ireland doesn’t agree. We’re all, apparently, entitled to an opinion on this matter.

We’re expected to – in a country whose media are so terrified of not having ‘balance’ that there were obligatory homophobes invited to every debate on marriage equality – ‘respect differences of opinion’, as this was some kind of abstract philosophical discussion where we just all needed to tolerate one another.

Being ‘pro life’, or rather ‘pro-embryo’, as Youth Defence and the Life Institute and their ilk will never be found speaking up for, say, the huge number of refugees fleeing war-torn countries, or children in an inadequate foster care system, is not a position you can hold without having absolutely no respect or empathy for women.

When you tell me you are ‘pro life’, we cannot have a discussion, because already I am lesser to you in your eyes. I am not a person. My body is not my own. When you tell me you are ‘pro life’, you are telling me that in the event of a crisis pregnancy, in the event of my body being asked to grow another human inside it for nine months, regardless of whether I want it or not, regardless of whether it was consensual sex or not, regardless of any risk to my health, regardless of the physical and emotional strain, you simply don’t care. You would rather see me imprisoned than have an abortion. You would rather see me strapped down to a table and have a premature baby sliced out of me. You would rather see me die.

This sounds like hyperbole. Except it isn’t. Fourteen years imprisonment for an abortion: that’s the law. Miss Y. Savita. These are real cases.

(We are coming up to the third anniversary of Savita Halappanavar’s death but we are still comfortable with the ten to twelve women who get on a boat or a plane each day to have a medical procedure that cannot be performed safely or legally in their own country.)

(We brought in a law that radically suggested women whose lives were at risk could have abortions, but even after psychiatrists declared a teenage rape victim suicidal, it wasn’t enough.)

If abortion law is an abstract for you, you are lucky. You are fortunate. For many of us, it is something hanging over our bodies constantly. We are lesser. We are vessels. We are not really people.

But it’s important we don’t get emotional or irrational about it. Otherwise we’re not worth listening to. We’re hysterical, then. Hysteria, from the Greek hystera. Uterus. The only part of us that seems to count.

September 5, 2015

Book review: Katy

A little birdie told me a while back that Jacqueline Wilson was working on a retelling of Susan Coolidge’s classic What Katy Did, a book I read (along with its sequel What Katy Did At School) many times as a youngling, and I was utterly charmed by the idea. In her note to the reader, Wilson explains that when she talks about that book, and others like it, with children who have disabilities, they wonder why the miracle solution afforded to so many of those Victorian heroes and heroines never applies to them. Have they not been saintly enough? Not good enough? So she has given us a modern Katy – and it’s magnificent.

Modern Katy is naughty and tomboyish, and her family have been reshuffled slightly so that the younger siblings in the original are now half-siblings, and Aunt Izzie is her stepmother. But all the characters are there – most particularly the irritating-yet-endearing Elsie who just wants to be friends with the older girls. Katy is a difficult, headstrong child, but she is also very likeable and relatable – which makes it all the more horrifying when an accident lands her in hospital and she is told she will be in a wheelchair for the rest of her life.

Readers of the original will expect a miracle cure, or at least a saintly acceptance of what has happened so that Katy might learn a lesson from all this. Not quite. There is no cure forthcoming, and instead Katy must learn to navigate life in a wheelchair, and figure out what she is still able to do, or what might need to be modified for her. But there’s no getting around the fact that this is an awful thing that’s happened to her. This is a real loss, not to be glossed over or fixed once Katy has become a better, kinder girl. And yet it’s not a gloomy book – there’s hope, and there’s fun, amidst the very real sadness and anger. I think it may be one of the best things Jacqueline Wilson has ever written, and for an author with over a hundred books to her name, that is saying something.

September 4, 2015

Book review: Miss Emily

Miss Emily and Miss Ada are worlds apart, but become friends with Ada is hired as the new maid in the Dickinson household. Having just emigrated from Ireland, she is very chatty and very Catholic – so when a young man assaults her, it is devastating.

Told in alternating chapters, this novel gives voices to two very different women dealing with the restrictions and mores of their society. We see some of Emily’s poetry, but we also see her as a rounded character who finds comfort in words but also in people and in baking – someone who is of the world rather than just witnessing it. We also see the extreme vulnerability of young women at this time – Ada goes through an awful lot of psychological and physical turmoil and it’s heartbreaking. The historical period is captured wonderfully, and it’s terrific to see Nuala’s work reach a wider audience with this novel.

September 3, 2015

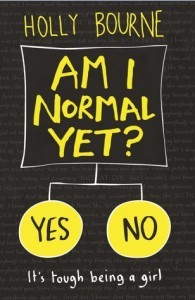

Book review: Am I Normal Yet?

Holly Bourne – Am I Normal Yet?

Holly Bourne – Am I Normal Yet?

The first in a trilogy focusing on the three members of the Spinster Club, Am I Normal Yet? introduces us to sixteen-year-old Evie, who’s started college away from most of the people who knew her as ‘that mental girl’, the one whose OCD and anxiety led her to be hospitalised and miss out on what she thinks of as crucial teen experiences. Now she’s in recovery – reducing her medication, developing strategies for addressing her compulsive worries and the attendant behaviour, and getting ready to be ‘normal’. Which means hanging out with her new friends, Lottie and Amber; going on dates, even if her first one leads to the boy in question sleeping with someone else at the party; and looking towards the future. But as her medication decreases, some of Evie’s symptoms return, and she develops new ones. And isn’t it true that love makes you crazy anyway?

Despite the heavy subject matter – this book is about mental health and feminism and the difficulties of fighting the patriarchy while also being a teenage girl who quite likes boys – this is a marvellous read, dancing between hilarious and painfully authentic. Evie’s voice is spot on, and she and her new friends discuss feminist issues without ever sounding preachy or self-righteous. The structural inequalities and the gendered stereotypes that they’re facing aren’t about women in boardrooms – they’re directly related to the ways many of the guys they know treat them, and how they treat those guys, too. This is a smart, funny, realistic look at what it means to be a girl today, and what it means to be ‘normal’. It offers up sharp insights into how we are newly comfortable talking about mental illness – but still unwilling to deal with the lived experience of it. It manages to be both readable and thought-provoking, and I can’t recommend it highly enough.

August 24, 2015

New story!

Illustration by Elizabeth Burgess

I’ve a new short story over at HeadStuff for their Fortnightly Fiction section, which comes with a nifty illustration. It’s called ‘What it Says in the Papers’ and is set during the Irish presidential election campaign in 2011 (four years ago – does that count as historical fiction these days?).Glad it’s found such a lovely home!

August 22, 2015

Book-review post!

Some recent YA…

James Dawson – All of the Above

Toria moves to a new town, a new school, and befriends the cool-misfit crowd – a group that hang out on an almost-abandoned mini-golf course and have all kinds of issues of their own, ranging from unrequited love to eating disorders. She quickly finds herself smitten with local rock-god Nico, but then there’s also Polly – filthy-mouthed, flirty, and utterly compelling. Toria’s definitely not gay, even though a fair proportion of her new friends seem to be, but as time goes on she starts to wonder where exactly the line is between friendship and love. This is a terrific read that touches on a lot of heavy and important issues but never feels too weighed down or solemn; Toria’s voice is brilliantly modern-teen-girl. Do read.

Lynn Weingarten – Suicide Notes from Beautiful Girls

You know that friend that you have who knows you better than anyone, who fascinates you more than anyone else, and who ultimately ends up being too much trouble? That’s Delia for June – and she’s just turned up dead. Everyone insists it’s suicide, but June refuses to believe it. Delia wouldn’t have done that. But is June just in denial, or is there more to Delia’s death than meets the eye? For anyone who likes their YA dark and twisty – this is for you.

Cat Clarke – The Lost and the Found

Laurel disappeared thirteen years ago, when she was six. There’s no way she’s coming home. Faith knows this, but Laurel’s disappearance still haunts her family, and filters into every aspect of her life. Then one day, out of the blue, Laurel returns – the happy ending they’ve all been waiting for – or is it? What’s it like when the sister whose shadow you’ve always lived in comes home, and isn’t quite as perfect as everyone seems to think she is? This is a thought-provoking read about missing children and how the media handle the cases – one of the journalists the family refuse to speak to has written a scathing book about how many missing-child cases there are, and how sickening it is that such attention was paid to pretty, white, blonde Laurel – and has a kick in the end that will leave you feeling as though… well, as though you’ve read a Cat Clarke novel. Terrific read.

Sarra Manning – The Worst Girlfriend in the World

I do so love Sarra Manning’s YA, and this one focuses on a pair of best friends – Alice, the titular ‘worst girlfriend in the world’ (an epithet stolen proudly from bathroom-stall graffiti), and Franny, the narrator, who’s just started a fashion course rather than pursuing A-levels along with most of her classmates. She’s living outside of Alice’s shadow for the first time in a long while, and making new friends – but Alice is not happy, and decides to pursue the local rock god (the same one Franny’s been lusting after for the past four years). And what Alice wants, Alice gets. This is a great look at studying fashion and design, at complicated friendships, at girls and how they’re judged by others, and at life in a small town where nothing much seems to happen. There’s also a heartbreaking subplot involving family and mental illness, and the strains put on the children of sufferers. Suffice it to say I had a lot of feelings while reading this.

August 18, 2015

Book review: Asking For It

This is another one where I had a lot of thoughts, so just this YA/crossover title for this post.

Louise O’Neill – Asking For It

(Thanks muchly to Quercus, via Hachette Ireland, for the review copy.)

Louise O’Neill’s debut was a dark dystopian novel in which women were valued for how they look. Her second novel is set in the modern world, where – well, the same applies. In a small town in Cork, Emma O’Donovan has just turned eighteen. She’s beautiful and she knows it. She has her bitchy moments; she’s jealous of her friends; she’s slept with a number of different guys and made them promise not to tell. She has sex because it’s there – because the guys want it – because it’s what you do after a few drinks. She’s a teenage girl caught in a world that gives her mixed messages about her sexuality, and she understands this instinctively without ever articulating it. One of her closest friends comes to her once, after having sex without consenting. You didn’t say no, Emma says, and tells her not to make a fuss. And as heartless as this may seem, it’s also savvy advice.

Because one night, one party, it’s Emma who’s out of it, Emma who’s determined to prove that she’s cool, Emma who accepts the offer of drugs, Emma who’s been drinking. And it’s Emma who wakes up the next day with no memory of what’s happened, having been dumped on her front porch half-naked.

Whatever happened to her, she must’ve had it coming to her. This is the logic she applies to her own situation, and the logic most others do too. And what happened doesn’t remain a secret in the era of the smartphone. It’s not too long before the photos emerge – four guys and an unresponsive Emma in a variety of positions, both intimate and degrading. Being barely legal means there’s no issue around pornography involving a minor, but it does mean that when these photos become known to the teachers in her school, they need to be reported to the police. And so begins a year of hell for Emma, which we see snapshots of as the narrative jumps ahead to the anniversary and the days when everyone’s talking about ‘the Ballinatoom case’ and ‘the Ballinatoom girl’ – not just in Ireland but all over the internet. Emma doesn’t want to be brave. She doesn’t want to be the girl who’s viewed in her small town as ruining the lives of the defendants, of their families – she just wants all of it to never have happened.

This is not an easy read, but it’s an important one. It is achingly honest – much as it would be lovely to see Emma view herself as a brave, unconflicted victim of a horrific crime, she can’t. And much as my own angry-feminist voice says that of course that’s what she is, her inability to see things that way is incredibly relatable and true-to-life – as well as echoing what so many of her community and the world at large thinks. Even if the boys were maybe a bit in the wrong, didn’t she have it coming… wasn’t she responsible in some way? Shouldn’t she have taken action to prevent…? No one made her drink or take drugs or wear that outfit… Not only that, but this is part of a broader culture where drunken, dubious-consent sexual experience is normalised. Emma is not the ideal rape victim – these are guys she knows! Guys she’s flirted with! Even guys she wouldn’t mind sleeping with! But that doesn’t make what happens any less of a sexual assault.

This is a book that empathises, rather than imagines. Because there is too much in here that is painfully familiar – priests shaking the hands of rapists to offer support, photos of teenage girls going viral and having her blamed for it, the ongoing slut-shaming. This is not some distant future or some hypothetical situation. This is a story that has been lived by many young women in our digital age, and what O’Neill’s novel does is give the survivor a voice and makes us listen. We mightn’t like Emma, or want her to be our BFF. But we can step into her shoes for a bit and feel how unfair it is. How powerless it makes her feel. How guilty, how ashamed.

How scary it is to live in a world, our world, as a girl people would rather use than respect, rather shame than believe.

Asking For It is published by Quercus Books on September 3rd, and is launching in Dublin in Eason’s O’Connell St on Wednesday September 2nd.

Book-review post!

This is another one where I had a lot of thoughts, so just this YA/crossover title for this post.

Louise O’Neill – Asking For It

(Thanks muchly to Quercus, via Hachette Ireland, for the review copy.)

Louise O’Neill’s debut was a dark dystopian novel in which women were valued for how they look. Her second novel is set in the modern world, where – well, the same applies. In a small town in Cork, Emma O’Donovan has just turned eighteen. She’s beautiful and she knows it. She has her bitchy moments; she’s jealous of her friends; she’s slept with a number of different guys and made them promise not to tell. She has sex because it’s there – because the guys want it – because it’s what you do after a few drinks. She’s a teenage girl caught in a world that gives her mixed messages about her sexuality, and she understands this instinctively without ever articulating it. One of her closest friends comes to her once, after having sex without consenting. You didn’t say no, Emma says, and tells her not to make a fuss. And as heartless as this may seem, it’s also savvy advice.

Because one night, one party, it’s Emma who’s out of it, Emma who’s determined to prove that she’s cool, Emma who accepts the offer of drugs, Emma who’s been drinking. And it’s Emma who wakes up the next day with no memory of what’s happened, having been dumped on her front porch half-naked.

Whatever happened to her, she must’ve had it coming to her. This is the logic she applies to her own situation, and the logic most others do too. And what happened doesn’t remain a secret in the era of the smartphone. It’s not too long before the photos emerge – four guys and an unresponsive Emma in a variety of positions, both intimate and degrading. Being barely legal means there’s no issue around pornography involving a minor, but it does mean that when these photos become known to the teachers in her school, they need to be reported to the police. And so begins a year of hell for Emma, which we see snapshots of as the narrative jumps ahead to the anniversary and the days when everyone’s talking about ‘the Ballinatoom case’ and ‘the Ballinatoom girl’ – not just in Ireland but all over the internet. Emma doesn’t want to be brave. She doesn’t want to be the girl who’s viewed in her small town as ruining the lives of the defendants, of their families – she just wants all of it to never have happened.

This is not an easy read, but it’s an important one. It is achingly honest – much as it would be lovely to see Emma view herself as a brave, unconflicted victim of a horrific crime, she can’t. And much as my own angry-feminist voice says that of course that’s what she is, her inability to see things that way is incredibly relatable and true-to-life – as well as echoing what so many of her community and the world at large thinks. Even if the boys were maybe a bit in the wrong, didn’t she have it coming… wasn’t she responsible in some way? Shouldn’t she have taken action to prevent…? No one made her drink or take drugs or wear that outfit… Not only that, but this is part of a broader culture where drunken, dubious-consent sexual experience is normalised. Emma is not the ideal rape victim – these are guys she knows! Guys she’s flirted with! Even guys she wouldn’t mind sleeping with! But that doesn’t make what happens any less of a sexual assault.

This is a book that empathises, rather than imagines. Because there is too much in here that is painfully familiar – priests shaking the hands of rapists to offer support, photos of teenage girls going viral and having her blamed for it, the ongoing slut-shaming. This is not some distant future or some hypothetical situation. This is a story that has been lived by many young women in our digital age, and what O’Neill’s novel does is give the survivor a voice and makes us listen. We mightn’t like Emma, or want her to be our BFF. But we can step into her shoes for a bit and feel how unfair it is. How powerless it makes her feel. How guilty, how ashamed.

How scary it is to live in a world, our world, as a girl people would rather use than respect, rather shame than believe.

Asking For It is published by Quercus Books on September 3rd, and is launching in Dublin in Eason’s O’Connell St on Wednesday September 2nd.

August 16, 2015

Bits and pieces from around the internet

The latest ‘what I’ve been reading online’ for your perusal:

‘how to get a book deal’, with advice from Irish editors, agents & authors

why we need gender quotas in politics

Rebecca Solnit discusses rape jokes and rape culture

let’s talk about periods

Louise O’Neill on sexism in publishing

the gender pay gap, and the lesbian/straight woman pay gap

Taylor Swift + Star Trek = joy

on why trigger warnings in academic settings do more harm than good

Nova Ren Suma on models for an author life, and finding what works for you

on free speech, hate speech and American exceptionalism

what teens want in YA fiction

Ariel Winter talks about breast reduction surgery and the difference it’s made to her

science takes on the anti-choice brigade

on kids’ media and video-on-demand services

alcohol in cartoons

two kinds of political comedy

learning through arts in school

why do girls out-perform boys in exams? (no mention of how this doesn’t help with the pay gap, mind you…)