Rada Jones's Blog, page 2

November 2, 2020

20 tips on surviving the COVID winter.

October 28, 2020

Jones Update

September 24, 2020

COVID travels 2: Turkey\’s heart.

After five days spent chasing Mehmet the Conqueror\’s shadow in a scorching Istanbul, haunted by moody cats and hungry carpet sellers, we left for dusty Edirne. The second Ottoman capital is a sleepy town in the tiny, bland European Turkey, and renting a car was a challenge, since they hadn\’t heard of one-way rentals, but we eventually lucked out with Budget.

Our automatic Renault Clio had no power windows or seats, nor GPS, but it did have a Check Engine warning. That got us worried, but the young Turk who set us up couldn\’t care less. He shrugged, bent over his volumes of paperwork and waved us off an hour later.

We made good time on the excellent, empty roads. We caught the ferry across the Dardanelles with minutes to spare and got to watch the cars rolling in. Ferry loading in Eceabat is nothing like the orderly ferry loading on Lake Champlain; it\’s more like Walmart on Black Friday: cars, trucks, and pedestrians wrestle to get in, while the attendants smoke on the dock.

Fortunately, nobody got hurt, and half an hour later we landed in Asia at Canakkale, near Gallipoli, the bloodiest battle of the first world war. There, the allies suffered more than 150K casualties, mostly ANZAC, trying to secure a passage over the Dardanelles. They failed. His career over, the Lord of Admirality, Winston Churchill, got demoted to an obscure cabinet post, resigned, and joined The Royal Scots Fusiliers to fight on the Western Front.

Canakkale\’s other claim to fame is its neighbor, legendary Troy of Homer fame. We saw the Trojan Horse leftover from the 2004 movie, but failed to get in. We acquired some adventurous Turkish wines instead and headed East to Anatolia.

Untouristy Manisa used to be one of the provinces designated as training grounds for the Sehzades, the young Ottoman princes. Here, Mehmet the Conqueror started his governorship at age 5. He came supervised by Huma Hatun, his mother – his father\’s third wife – and some of the most learned people of the day. Muhammad Shams al-Din bin Hamzah – let\’s call him Ak – was a doctor, a philosopher, and a theologian who wrote about germs hundreds of years before the West started washing its hands.

\”It\’s incorrect to assume that diseases appear one by one in humans,\” he said. \”Disease infects by spreading from one to another. Infection occurs through seeds too small to be seen, but still alive.\”

\”It\’s incorrect to assume that diseases appear one by one in humans,\” he said. \”Disease infects by spreading from one to another. Infection occurs through seeds too small to be seen, but still alive.\”

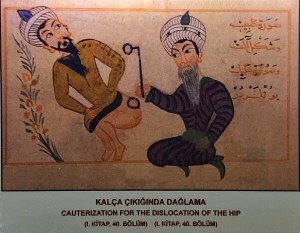

We\’re talking 1400\’s here. Hospital museums in Turkey still display his utensils, books and prescriptions. More than five hundred years ago, he used music and aromatherapy in the care of his patients – alongside using cautery for headaches and dislocated hips. Not sure if that works, since that procedure hasn\’t made it into modern medicine yet.

After Manisa, we proceeded East to Pamukkale, where the ancient ruins struggle to compete with the white travertines and fail. Mineral hot springs coated the hills in calcium, creating a white wonderland. Barefooted tourists crawl over each other, taking unmasked selfies with their new two hundred close friends. Unlike Hieropolis, the place to see, Pamukkale is the place to be seen.

But the place to be is the ancient pool, where ruins meet the mineral waters. You swim in the warm, fizzy mineral water over sculpted marble columns, you caress ancient artifacts, and immerse yourself in history.

But the place to be is the ancient pool, where ruins meet the mineral waters. You swim in the warm, fizzy mineral water over sculpted marble columns, you caress ancient artifacts, and immerse yourself in history.

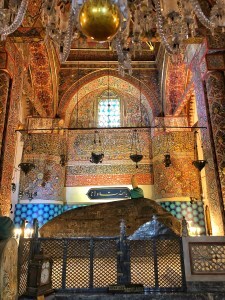

East again, to conservative Konya, the heart of Anatolya, where women are scarved, restaurants dry, and pigs absent. This most conservative Turkish town happens to be the home of Rumi, aka Mevlana, a famous poet, mystic and philosopher. Before he died, eight hundred years ago, Rumi spoke about love and tolerance and taught us to look for God inside ourselves.

East again, to conservative Konya, the heart of Anatolya, where women are scarved, restaurants dry, and pigs absent. This most conservative Turkish town happens to be the home of Rumi, aka Mevlana, a famous poet, mystic and philosopher. Before he died, eight hundred years ago, Rumi spoke about love and tolerance and taught us to look for God inside ourselves.

\”Looking for God, I went to the temple, where the magi chant for fire. He wasn\’t there.

I went to Jerusalem to see if he was on the cross, but he wasn\’t there either.

I went to Mecca, but he wasn\’t in the sanctuary.

Then I looked into my heart. And there he was, and nowhere else.\”

His message inspired the Whirling Dervishes, whose mesmerizing dance is a meditation and a prayer to commune with God. Inspired by Rumi\’s uplifting message, we tried to feel love for the vocal carpet sellers harassing us. We failed, so we headed further East.

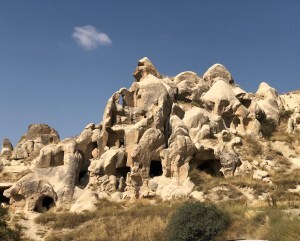

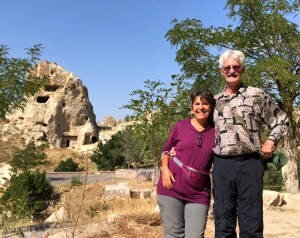

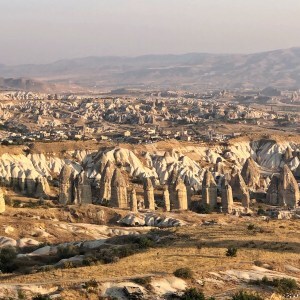

Capadoccia\’s otherworldly landscape is like nothing else on earth. Thousands of years ago, overactive volcanoes spewed tons of lava that cooled to become tufa, a soft volcanic rock. Winds shaped the tufa into a phallic landscape that guidebooks call \”fairy chimneys.\” Less romantic and more anatomically inclined, I see no chimneys. What do you see?

People dug the soft rock into mazes of dwellings and churches, some still in use. You can walk, ride a horse, or take a four-wheeler to explore, but THE thing to do is a balloon ride. Hundreds of outfits compete for your business. They\’ll pick you up before sunrise and take you to the launch site, where you watch the balloons come alive, full of flame-heated air. You tumble into the bath-sized basket with your twenty closest new friends. Then, for an hour, you get to ride the wind.

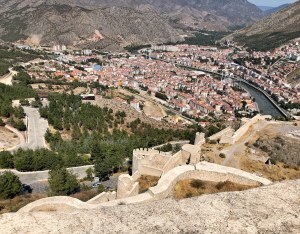

Still further East, perched upon an imposing cliff, the Tokat castle used to be a prison where the ememies of the Ottoman Empire spent miserable years hoping to die. Five hundred years ago, its dark, dingy dungeons hosted Vlad Tepes, the teenage Wallachian prince who, thanks to Bram Stoker\’s morbid imagination, was to, someday, become Dracula.

To find his steps, I navigated us through narrow back streets past scarved women scrubbing Persian carpets, bald angry roosters, and wide-eyed kids. We pushed through until we could go no more. Then, unable to turn, we backed up, until Steve stuck the car sideways. I got to watch, wondering if helicopters can lift cars, as Steve managed to turn it in only two dozen swift moves. Tokat watched breathlessly as a new legend was born.

After Tokat we turned North. Amasya, the city of apples and another former training groung for the Sehzades, is now a quiet small town where the only remnant of its glory days is the well-restored 9th-century castle.

Why all this princely training, you may ask?

Unlike Western states, the Ottoman Empire didn\’t recognise primogeniture. As in, the firstborn son didn\’t walk away with the loot. When a Sultan died, it was all about the survival of the fitest. His sons from many wives would compete for the throne, killing each other and weakening the empire. That went on until Mehmet legalized fratricide, and had his eight-months old brother drowned in his own bath. After that, each sultan\’s death meant immediate death for all their sons, but the one who took the throne. That\’s why Sultan\’s mausoleums all over Turkey are full of tiny coffins.

That makes two thousand miles through the heart of Turkey, before we headed back to Istanbul. As for my highs and lows,

My highs

1. The Turks. From the man who picked us on a dark stormy night in his rickety car and drove us to our hotel, to the one filling up our gas, they all ask: \”Where you\’re from? America? New York?\” and their eyes fill with longing. We can hardly communicate, since their English is no better than my Turkish – yok – but their friendliness always comes through.

2. The sweets. Sweet stores are everywhere, clean, bright, and tempting. Decadent confections like baklava and cataif drip with butter and honey, making your mouth water. Turkish Delight filled with nuts, pistachio, and chocolate cream comes in wobbly cubes or in wiggling sugar-powdered snakes that you cut with scissors to taste before you buy. Sold by the kilo, (2.2 pounds,) they glue your teeth, coat your fingers and stick to your hips.

3. Bathing with the columns in Pamukkale and immersing myself in history. I hope I never forget.

4. Finances. Prices got better the deeper we got into Turkey. So did the exchange rate from 6.9TL for 1$ in Istanbul airport, to 7.65 in last night\’s hotel. Outside Istanbul, a comfortable hotel room with wi-fi, parking, and impressive breakfast runs around $40, a decent dry dinner $25, a good Turkish red wine $10, an ice-cream cone $0.5.

5. The fruit. One fruit stand after another, we ate our way through Turkey: Succulent peaches, golden grapes and fleshy figs gave way to walnuts and crisp green apples, then to wrinkled yellow melons. We\’re back to grapes now, but I can\’t wait to be back in fig land. Fresh figs are to the dry what grapes are to raisins: luscious, decadently delicious, and full of flavor.

My lows

1. Gender segregation. One could be forgiven for thinking that Turkey is a country of men. Men only, wherever you look. They chat on long benches in shaded parks, smoke in front of old houses, mind the stores, ogle you in the street. Women are rare, hurried, and shrouded.

2. Pizza. My worst food memory was a Chinese take-out twenty years ago in Cairo, but our Tokat pizza is a strong contender. Loaded with dry cheese and sliced hot-dogs, it had sticky dough and no tomato sauce. It came with ketchup, mayo, and one set of cutlery. For Steve.

3. Unilingual tourist businesses. People in the street don\’t speak English – why should they? But those working at TI, rental cars, and money changers should.

4. Cardboard policing. At intersections, cardboard police cars flash their lights, fooling drivers, while policemen are nowhere in sight. The locals know it, of course, but we don\’t.

5. Masks. Like everybody else, Turkey struggles with them, too, though they are mandatory in public unless you\’re sitting in a restaurant – we even got stopped to put them on while driving in our car. But people take them off to smoke or take selfies; they wear them around their chin, and they poke holes in them to breathe better.

That\’s all I\’ve got for the heart of Turkey. Sign up if you want the updates. Next time: Turkey\’s many capitals. Hope to see you soon

Rada Jones is an ER doc in Upstate NY, where she lives with her husband and his deaf black cat Paxil. After authoring three ER thrillers, Overdose , Mercy and Poison , and “ Stay Away From My ER ,” a collection of medical essays, she’s now working on a historical novel featuring Vlad Țepeș, his gay brother Radu, and Mehmet the Conqueror.

September 13, 2020

COVID Travels: Istanbul

A couple months ago, when Steve left Thailand to get our home on the market, we thought Thai borders would soon crack open, to allow him back. We were wrong. These days in Thailand, whoever\’s out stays out. If I wanted to see him again, I had to join him. So I did.

I flew out via Turkey to research my new books. Steve joined me, and we met at Istanbul Airport.

Besides eight boring hours in the empty Bangkok Airport, my trip was excellent: no crowds and no delays. In Doha, I even got a shower.

Twenty hours into my trip, I stepped in the business lounge carrying my old backpack and many worries. The attendant glanced at me.

\”Would you like a shower?\”

I opened my mouth to give him a piece of my mind.

\”Yes, please,\” my mouth said.

I loved the private shower with hot water, clean towels, and nice toiletries. I came out happier and better smelling. Sadly, that effect was mostly gone when I landed in Istanbul, but it didn\’t matter. Steve didn\’t smell any better.

We recognized each other despite masks, shields, and the Sauvignon Blanc Steve admitted to. Our hired car took us to our two-star hotel in Istanbul\’s heart with a splendid view of the Marmara, outstanding breakfast, and lousy Internet, and our hosts dragged us to our first overpriced Turkish dinner at their family\’s restaurant. Here, it\’s all about the family.

For days and days we dragged our achy feet on the cobbled streets of Istanbul, formerly Constantinople, sweating under our masks, to find the history I came here for. We got lost looking for toilets in Topkapi. We stared at incomprehensible Turkish inscriptions of monuments, and we turned down more carpets than I can count. We petted cats, chatted with locals, and fumbled through Istanbul without GPS or a map. No GPS to avoid roaming. No map, since Steve dropped it in a Turkish toilet. You know Turkish toilets? Imagine a toilet without a toilet: two porcelain footprints and a hole in between. The hole is for the maps. Works for pens too. Your legs must be strong enough to hold you in a low squat as you do your business, then stand up without touching the walls. It\’s an experience worth a Turkish lira, about 15 cents, I thought, until I saw people crawling in under the turnstiles. The other way to free pooping is finding a mosque. They provide free toilets and a live show: there, proper black-clad ladies tie their skirts around their waist to keep them from touching the floor, then wash in the sink for the ablution before prayer.

After four days of Istanbul immersion, we left to see the rest of Turkey. We\’ll be back, but for now, these are my highlights and lowlights of Istanbul.

The highlights:

1. The waters. Istanbul lives around its waters. The Bosporus Strait, running from the Black Sea to the Marmara, is alive with ships. Fishing boats, yachts and tankers frolic together over the turquoise (Turkish style) water. The Sea of Marmara starts its day blood-red. The Golden Horn, a dagger of water slicing the old Istanbul from the new, turns yellow at sunset.

2. The cats. Istanbul belongs to cats. Dignified, standoffish, and well-fed, they sun themselves on top of fences and socialize around ruins. They talk back when you speak to them, and show you where to put it if you try to pet them. Just ask Steve, who never met a cat he didn\’t try to touch.

[image error]

3. The food. The scrumptious breakfast spread in our modest hotel, prepared by a smiling Turkish lady that speaks no English, changes every morning. Fresh pitta, warm pastries, five kinds of cheese, cold cuts, green and black olives, roasted eggplant with red peppers, solid chunks of translucent green cantaloupe, and bright red watermelon with black seeds – they all call your name, delicious and hard to resist.

4. The people. Black-clad women with just a slit for the eyes rub shoulders with tourists exposing soft midriffs and sporting shorts too short to matter. Elderly men drink tea from tulip glasses watching screaming kids throwing water bottles at each other. Istanbul has room for people of all kinds.

5. Pigeons. On Sundays, pigeon lovers meet at the bird market by the old Theodossian walls to sell, buy or trade birds. Tumbling pigeons, doing tricks as they fly, like planes at airshows, cost thousands of dollars for the bird with the right breeding. Sellers outdo each other singing praise for their birds, and negotiations mean long hours of happy shouting, checking every feather of the bird, and drinking tea.

[image error]

6. Turkish baths. I had my first Turkish Bath in a fifteenth-century hamam, bathhouse built for a long dead Sultan\’s mother. The attendant, a Turkish lady with fading charms loosely packaged in a skimpy bikini, scrubbed me with a rough glove until I turned white, covered me in soapsuds and massaged me, then scrubbed me again. By the end, I had no dirt left and hardly any skin. Her no-nonsense efficiency reminded me of that one time when our cat Paxil got skunked. I washed her in the sink with abandon, dedication, and dishwashing detergent. Unlike Paxil, I didn\’t bite.

The lowlights.

1. The carpets. If I never see another carpet seller, I\’ve seen too many. They lay in wait to leap on you, anytime, anywhere. In the mosque, over lunch, as you cross the street. \”Where are you from? Where are you going? You want to buy a carpet?\” Being polite doesn\’t work. Being rude is rude. And it doesn\’t work either. As they see it, you\’re only here to buy what they sell, so you might as well make yourself useful. They shout at you from far away, they get in your face, they follow you in the street, and they won\’t take no for an answer. I prefer mosquitoes.

2. The Blue Mosque. Whatever there\’s left of it isn\’t blue, it\’s covered in scaffolds and shrouded in cloth. That appears to be its new permanent condition now, since the Turkish government uses eternal restoration projects to keep people employed.

3. The traffic. Istanbul\’s 15 million people – twice as many as NYC – spend up to five hours a day in traffic if they live one side of the Golden Horn and work on the other. The endlessly blowing horns made me wonder if cars here navigate by audio-location, like bats.

4. Hagia Sophia. The 1500 years old former Orthodox Church became a Mosque in 1453, when the Ottomans conquered Constantinople. Half a century later, when Ataturk, the creator of modern Turkey, separated the state from the mosque, it turned into a museum. Then, a couple of months ago, she went back to a mosque. No wonder she\’s struggling with an identity crisis. Posters with Mohammed\’s sayings hide thousand years old Christian Mosaics, while scantily dressed tourists wrapped in hooded paper gowns scramble to find their shoes and stern police officers try to keep men away from the women\’s mosque, while nobody knows which is which.

5. Cold French Fries. There\’s something perverse about the Turkish infatuation with stale fries. They\’re served everywhere, all the time: at breakfast, alongside chalky Turkish yogurt, spicy red pepper paste, and scrumptious sour cherry preserves, stuffed into wraps for lunch, and with the mezze for dinner. BUT WHY?

6. The COVID factor. It isn\’t crowded, and that\’s nice. But walking with a mask in 90 degrees heat gets old soon, and we\’re avoiding public transport to socially distance. And, since our flights to the US have vanished, we\’re here for now.

That\’s my first take on Istanbul. There\’s much I haven\’t seen, and more I don\’t understand, but I wanted to share my wonder to those stuck at home. Sign up for my update if you want more, since Facebook is not my friend.

Güle Güle – bye-bye for now.

Rada

Rada Jones is an ER doc in Upstate NY, living with her husband and his deaf black cat Paxil. She authored three ER thrillers, Overdose , Mercy and Poison , and “ Stay Away From My ER ,” a collection of medical essays.