Kristine Hughes's Blog, page 73

July 10, 2015

THE DUKE OF WELLINGTON TOUR: WE INVADE WELLINGTON ARCH

Across the crazy traffic circle in front of Apsley House, the Wellington Arch stands in isolated magnificence. With some exceptions we will note further along.

To read what Victoria wrote about the history of the Wellington Arch last year, click here.

Looking through the arch toward Buckingham Palace

Looking through the arch toward Buckingham Palace Our Guide Clive points out the Wellington statue nearby.

Our Guide Clive points out the Wellington statue nearby. \The doors bear the royal crest.

\The doors bear the royal crest. Decimus Burton, architect of the arch and the Hyde Park Screen across the street, also designed the iron doors, cast by Joseph Bramah & Sons of Pimlico. They are painted to resemble a bronze patina.

Decimus Burton, architect of the arch and the Hyde Park Screen across the street, also designed the iron doors, cast by Joseph Bramah & Sons of Pimlico. They are painted to resemble a bronze patina.For information on the exhibitions at the Arch, go their website, click here.

We elevated to the top of the arch for the daily parade of guards and were excited at the view. Took many many pictures!

Through the screen and into the park beside Apsley House.

Through the screen and into the park beside Apsley House.

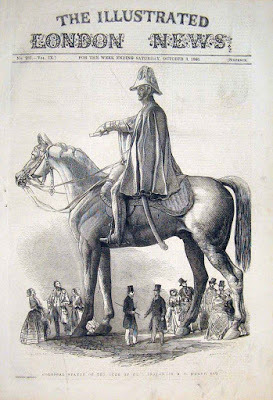

The Quadriga by Adrian Jones, finished 1912, replaced the monumental statue atop the Arch. The equestrian statue of the Duke had provoked considerable controversy, even ridicule, before it was dismantled and moved to its present location in Aldershot.

The Quadriga by Adrian Jones, finished 1912, replaced the monumental statue atop the Arch. The equestrian statue of the Duke had provoked considerable controversy, even ridicule, before it was dismantled and moved to its present location in Aldershot. The monumental equestrian statue (8.5 metres high, aka 28 feet) overwhelmed the arch.

The monumental equestrian statue (8.5 metres high, aka 28 feet) overwhelmed the arch.Completed in 1846, the statue was cast from 40 tons of bronze, mostly from melted down French cannons, at a cost of £30,000. Though everyone was unhappy, it was raised on the arch, where it stood until the necessity for moving the location of the arch itself in the late 1880's.

Gigantic size!

Gigantic size! In its present position atop a hill in Aldershot, Hampshire, near the Military Museum, the statue has found a suitable home. The responsible artist was Matthew Coates Wyatt (1777-1862). It was restored in recent years.

In its present position atop a hill in Aldershot, Hampshire, near the Military Museum, the statue has found a suitable home. The responsible artist was Matthew Coates Wyatt (1777-1862). It was restored in recent years. Today on the grounds of the Arch.

Today on the grounds of the Arch.

Wellington Statue near the Arch, by Joseph Boehm, 1888

Wellington Statue near the Arch, by Joseph Boehm, 1888

Apsley House from atop the Arch

Apsley House from atop the Arch

Close up of the capital of the Corinthian Columns

Close up of the capital of the Corinthian Columns

Apsley House from the traffic circle

Apsley House from the traffic circle

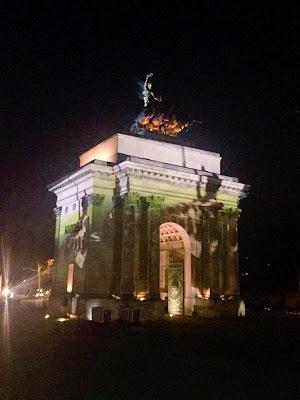

The Wellington Arch, illuminated during the celebration of the Battle of Waterloo Centenary, 2015

The Wellington Arch, illuminated during the celebration of the Battle of Waterloo Centenary, 2015After a fond farewell to the Wellington Arch and its nearby statue of the Duke of Wellington, our tour group proceeded to the bus and our drive across London to the Tower.

Published on July 10, 2015 00:30

July 8, 2015

WATERLOO'S AFTERMATH, PART TWO

DISPOSING OF NAPOLEON

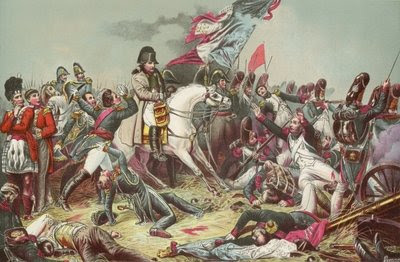

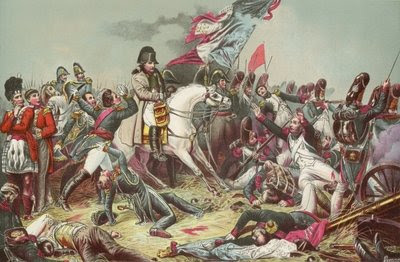

Napoleon and the Garde

Napoleon and the Garde

After the Battle on the 18th of June, Napoleon tried unsuccessfully to re-group. Unable to sort out the demoralized and scattered sildiers, he turned over command of his armies to General Soult and fled to Paris. The armies had about 150,000 troops stationed around France, including General Grouchy’s 60,000, who returned to Laon by June 26. Another 175,000 (?) conscripts were in training. There were also General Rapp’s Armee of the Rhine and General Lamarque’s Armee of La Vendee, still in place waiting for the Austrians and Russians. Napoleon wanted to continue the war, but he needed political and financial support.

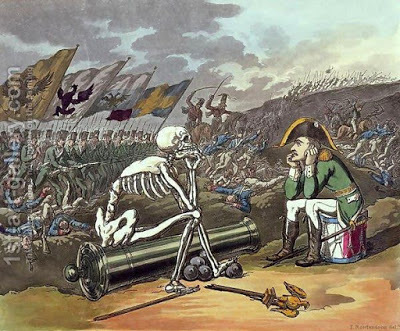

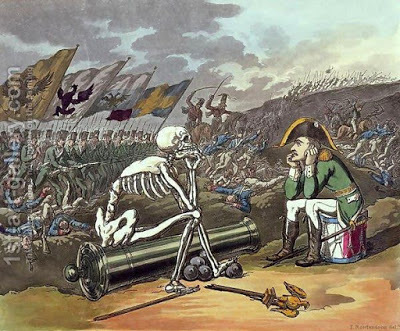

Rowlandson on Napoleon's Legacy

Rowlandson on Napoleon's Legacy

Napoleon was unsuccessful in getting the Chamber of Deputies -- or anybody else except his closest confidantes -- to agree to renew the war.

Marquis de Lafayette, 1790

Marquis de Lafayette, 1790

Lafayette, 1825

Lafayette, 1825

The hero of the American Revolution, the Marquis de Lafayette (1757-1834) spoke against Napoleon in the Chamber, in answer to pleas of the disgraced emperor by his brother Lucien Bonaparte. Lafayette said:“By what right do you dare accuse the nation of…want of perseverance in the emperor’s interest? The nation has followed him on the fields of Italy, across the sands of Egypt and the plains of Germany, across the frozen deserts of Russia. … The nation has followed him in fifty battles, in his defeats and his victories, and in doing so we have to mourn the blood of three million Frenchmen.”

Lafayette’s views prevailed and Napoleon was rejected. His attempted abdication in favor of his four-year-old son on June 22 (and by some reports, a failed suicide) was ignored by the Allies.

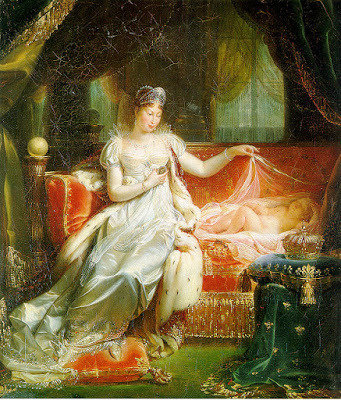

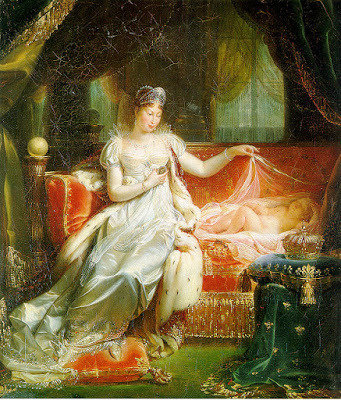

Marie Louise had fled to Austria with her son.

Marie Louise had fled to Austria with her son.

Fouché, president of the new provisional government, sent word Napoleon should leave Paris. Napoleon stayed for a few days at his late first wife’s chateau, Malmaison, just west of Paris. Here he and Josephine(who died in 1814) had enjoyed happiness and success. How he must have yearned for those days to return.

Malmaison, 2014

Malmaison, 2014

The Prussians were approaching by June 29, and he did not want to be captured. When he got word from the provisional government that he was not be issued any safe conduct by Blücher or Wellington, Napoleon decided to travel to the Atlantic coast and find a ship to take him to the United States, where he hoped to find refuge; he arrived in Rochefort on July 3. However, the British blockade, in effect again since his escape from Elba, made that impossible. Instead, he negotiated his surrender to Captain Frederick Maitland aboard the HMS Bellerophon on July 15.

An amusing aside: Upon boarding the HMS Bellerophon, Napoleon took over the cabin of the Captain and invited him and others to breakfast with him. Captain Humphrey Senhouse, captain of another ship in the fleet, later wrote to his wife: “I have just returned from dining with Napoleon Bonaparte. Can it be possible?”

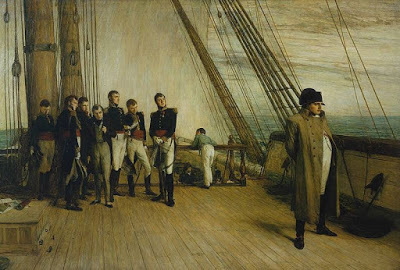

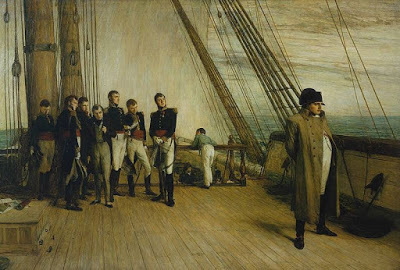

Napoleon Aboard the Bellerophon, by Sir Charles Lock Eastlake

Napoleon Aboard the Bellerophon, by Sir Charles Lock Eastlake

Napoleon appealed to the Prince Regent: “the most powerful, the most constant, and the most generous of my foes.” But the Government of Lord Liverpool was not inclined to make any allowances, and Prinny had enough troubles of his own.

Napoleon Aboard the Bellerophon by Sir William Quiller Orchardson (1832-1910)

Napoleon Aboard the Bellerophon by Sir William Quiller Orchardson (1832-1910)

In the meantime, the Allies had entered Paris on July 7, 1815, and successfully arranged for Louis XVIII to take the throne, which he did on July 8.

The Bellerophon sailed to Torbay arriving July 24 and on to Plymouth where Napoleon became a sort of tourist attraction as people hired boats to go out and see him aboard the Bellerophon where he was kept.

Tourists seeking Napoleon aboard the Bellerophonpainting by John James Chalon, 1817

Tourists seeking Napoleon aboard the Bellerophonpainting by John James Chalon, 1817

On August 7, he was transferred to the HMS Northumberland for the voyage to his imprisonment on the Island of St. Helena in the South Atlantic, arriving August 17.

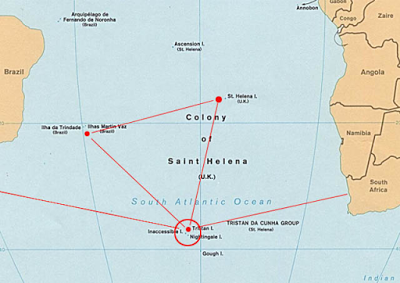

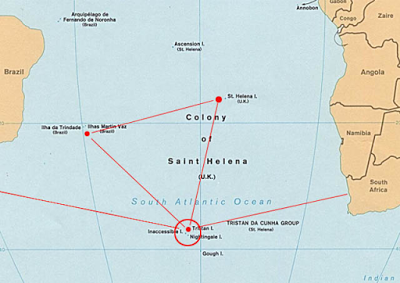

Remoteness of St. Helena in the South Atlantic

Remoteness of St. Helena in the South Atlantic

St. Helena is more than 1,200 miles from the nearest landmass. He lived there, until his death on May 5, 1821.

Napoleon on St Helena

Napoleon on St Helena

The island was small, wind-blown and not particularly pleasant. The ex-emperor was accompanied by a few companions. The British governor of the island, Sir Hudson Lowe, was determined there would be no second escape from captivity.

Longwood, Napoleon;s residence on St Helena

Longwood, Napoleon;s residence on St Helena

On St Helena, Napoleon composed his self-congratulatory memoirs. He found excuses in the mistakes of his generals and others for all his defeats and shortcomings. But however shallow these justifications, many of his observations are applauded by the devotees of the cult which has grown around his memory. He never stopped complaining about the conditions of his captivity, but none of the far-fetched schemes for his rescue ever materialized in the face of the British navy and the remote position of St. Helena.

Death of Napoleon by Carl von Steuben

Death of Napoleon by Carl von Steuben

Napoleon died in 1821 of a stomach ailment, probably cancer. He was 51 years of age. A similar disease had caused his father’s death at the early age of 40. Napoleon in middle age often complained of stomach problems. Many believe he was poisoned, as large amounts of arsenic were found in his remains. Nothing can be disproven about the poison as arsenic was often found in various ointments and lotions of the day, as well as in the formula for the green inks and dyes in the wallpaper of his living quarters.

He was buried on St. Helena until his remains were returned to France in 1840.,

Napoleon and the Garde

Napoleon and the GardeAfter the Battle on the 18th of June, Napoleon tried unsuccessfully to re-group. Unable to sort out the demoralized and scattered sildiers, he turned over command of his armies to General Soult and fled to Paris. The armies had about 150,000 troops stationed around France, including General Grouchy’s 60,000, who returned to Laon by June 26. Another 175,000 (?) conscripts were in training. There were also General Rapp’s Armee of the Rhine and General Lamarque’s Armee of La Vendee, still in place waiting for the Austrians and Russians. Napoleon wanted to continue the war, but he needed political and financial support.

Rowlandson on Napoleon's Legacy

Rowlandson on Napoleon's LegacyNapoleon was unsuccessful in getting the Chamber of Deputies -- or anybody else except his closest confidantes -- to agree to renew the war.

Marquis de Lafayette, 1790

Marquis de Lafayette, 1790 Lafayette, 1825

Lafayette, 1825The hero of the American Revolution, the Marquis de Lafayette (1757-1834) spoke against Napoleon in the Chamber, in answer to pleas of the disgraced emperor by his brother Lucien Bonaparte. Lafayette said:“By what right do you dare accuse the nation of…want of perseverance in the emperor’s interest? The nation has followed him on the fields of Italy, across the sands of Egypt and the plains of Germany, across the frozen deserts of Russia. … The nation has followed him in fifty battles, in his defeats and his victories, and in doing so we have to mourn the blood of three million Frenchmen.”

Lafayette’s views prevailed and Napoleon was rejected. His attempted abdication in favor of his four-year-old son on June 22 (and by some reports, a failed suicide) was ignored by the Allies.

Marie Louise had fled to Austria with her son.

Marie Louise had fled to Austria with her son.Fouché, president of the new provisional government, sent word Napoleon should leave Paris. Napoleon stayed for a few days at his late first wife’s chateau, Malmaison, just west of Paris. Here he and Josephine(who died in 1814) had enjoyed happiness and success. How he must have yearned for those days to return.

Malmaison, 2014

Malmaison, 2014The Prussians were approaching by June 29, and he did not want to be captured. When he got word from the provisional government that he was not be issued any safe conduct by Blücher or Wellington, Napoleon decided to travel to the Atlantic coast and find a ship to take him to the United States, where he hoped to find refuge; he arrived in Rochefort on July 3. However, the British blockade, in effect again since his escape from Elba, made that impossible. Instead, he negotiated his surrender to Captain Frederick Maitland aboard the HMS Bellerophon on July 15.

An amusing aside: Upon boarding the HMS Bellerophon, Napoleon took over the cabin of the Captain and invited him and others to breakfast with him. Captain Humphrey Senhouse, captain of another ship in the fleet, later wrote to his wife: “I have just returned from dining with Napoleon Bonaparte. Can it be possible?”

Napoleon Aboard the Bellerophon, by Sir Charles Lock Eastlake

Napoleon Aboard the Bellerophon, by Sir Charles Lock EastlakeNapoleon appealed to the Prince Regent: “the most powerful, the most constant, and the most generous of my foes.” But the Government of Lord Liverpool was not inclined to make any allowances, and Prinny had enough troubles of his own.

Napoleon Aboard the Bellerophon by Sir William Quiller Orchardson (1832-1910)

Napoleon Aboard the Bellerophon by Sir William Quiller Orchardson (1832-1910)In the meantime, the Allies had entered Paris on July 7, 1815, and successfully arranged for Louis XVIII to take the throne, which he did on July 8.

The Bellerophon sailed to Torbay arriving July 24 and on to Plymouth where Napoleon became a sort of tourist attraction as people hired boats to go out and see him aboard the Bellerophon where he was kept.

Tourists seeking Napoleon aboard the Bellerophonpainting by John James Chalon, 1817

Tourists seeking Napoleon aboard the Bellerophonpainting by John James Chalon, 1817 On August 7, he was transferred to the HMS Northumberland for the voyage to his imprisonment on the Island of St. Helena in the South Atlantic, arriving August 17.

Remoteness of St. Helena in the South Atlantic

Remoteness of St. Helena in the South AtlanticSt. Helena is more than 1,200 miles from the nearest landmass. He lived there, until his death on May 5, 1821.

Napoleon on St Helena

Napoleon on St HelenaThe island was small, wind-blown and not particularly pleasant. The ex-emperor was accompanied by a few companions. The British governor of the island, Sir Hudson Lowe, was determined there would be no second escape from captivity.

Longwood, Napoleon;s residence on St Helena

Longwood, Napoleon;s residence on St HelenaOn St Helena, Napoleon composed his self-congratulatory memoirs. He found excuses in the mistakes of his generals and others for all his defeats and shortcomings. But however shallow these justifications, many of his observations are applauded by the devotees of the cult which has grown around his memory. He never stopped complaining about the conditions of his captivity, but none of the far-fetched schemes for his rescue ever materialized in the face of the British navy and the remote position of St. Helena.

Death of Napoleon by Carl von Steuben

Death of Napoleon by Carl von SteubenNapoleon died in 1821 of a stomach ailment, probably cancer. He was 51 years of age. A similar disease had caused his father’s death at the early age of 40. Napoleon in middle age often complained of stomach problems. Many believe he was poisoned, as large amounts of arsenic were found in his remains. Nothing can be disproven about the poison as arsenic was often found in various ointments and lotions of the day, as well as in the formula for the green inks and dyes in the wallpaper of his living quarters.

He was buried on St. Helena until his remains were returned to France in 1840.,

Published on July 08, 2015 00:30

July 5, 2015

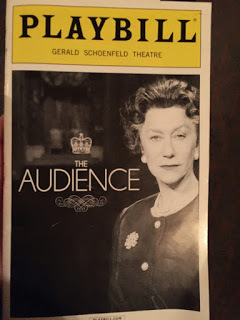

THE AUDIENCE - A REVIEW

Recently, my daughter, Brooke, decided to surprise herself with tickets to see Billy Joel for her birthday. She bought two tickets to the concert and sent me a text message -

Brooke: Just got two tix to see Billy Joel for my birthday. No one I'd rather spend my birthday with than you so you're coming. Already bought. You can't say no.

Me: OK. Where?

Brooke: MSG

Me: Huh?

Brooke: Madison Square Garden.

Me: In NYC?!

And so we planned a long weekend in Manhattan. It occured to me to look online to see what was playing in the theatres during our stay. And look what I found -

It took me a New York minute to click on the "buy" button. And then I sent Brooke a text -

Me: I just got us two tix to see Helen Mirren in The Audience.

Brooke: Who?

Me: Helen Mirren. British actress. You'll know her when we see her. She's playing the Queen.

Brooke: K

K? That's what you say to two tickets to see The Audience? K?

So, Thursday night we went to see Billy Joel at the Garden. He was fabulous. Here's a clip of Piano Man from the show we attended on May 28.

And on Friday night we had dinner at Patsy's iconic Italian restaurant and then headed to the theatre to see Dame Helen (Yay!)

The Schoenfeld Theatre is intimate in size, so when we found our seats, I was delighted to find that we were just six rows back from the stage. I could write my own review of the play, which, unsurprisingly, was fabulous, but there are others who have written better and so I give you the excellent piece written for the Huffington Post:

Take a revered, honored and accomplished actress (Dame Helen Mirren) and put her in a new play which reprises a character that won her a Best Actress Oscar in 2006 (as Elizabeth in "The Queen"). And not a mere ripoff. Put it in the hands of Peter Morgan, who wrote "The Queen," and whose theatrical bonafides include the astonishingly good Frost/Nixon; and director Stephen Daldry, of the stunning 1992 revival of An Inspector Calls and the international musical hit Billy Elliott. There are enough fans of Mirren, and H.R.H., and Anglophile television, to attract S.R.O. audiences in the West End and on Broadway for as long as the star wishes to wear the crown.

"Snapshots from The Queen," you might call it; in this case, it is more like a scrapbook. "The Queen" was set in one year of Elizabeth's reign, 1997, when she was dealing with the death of Princess Diana; Morgan's The Audience centers on sixty years-worth of Elizabeth's weekly audiences with her Prime Ministers (eight of whom are represented, starting with Winston Churchill and ending with the current David Cameron). And there's the rub. While most theatergoers are likely to be thrilled byThe Audience--or more precisely, by Mirren's performance in The Audience--the concept dictates that we will be seeing pages from a scrapbook, without the dramatic heft that would make it a fine and/or important play.

Yes, there is great life for The Audience with Helen Mirren; but the script itself seems to be merely an element of the evening devised to support the star performance, in the same manner as Bob Crowley's sets and costumes and Ivana Primorac's hair and make-up. Consider The Audience without the participation of Helen Mirren; while other stars are likely to try it--Kristin Scott Thomas is scheduled to do the play at London's Apollo next month--the appeal, here, is watching the star of "The Queen" playing The Queen live and in person. Compare this to Frost/Nixon; while original stars Sheen and Langella were unforgettable in the roles, the play is more than strong enough to work with any number of actors.

The format is simple enough. The Equerry--a combination butler/narrator--sets the scene; Geoffrey Beevers, one of the four actors imported with Mirren from London, has a droll and authoritative, raised-eyebrow manner which keeps the evening moving. One is slightly surprised that he doesn't start the affair with one of those "the action starts in 1936, before the age of cell phones, so please do toggle yours off" speeches. We then see Elizabeth with one of her more familiar prime ministers, John Major (a somewhat restrained and not-quite-comfortable Dylan Baker). Major exits; Equerry makes a little speech; a team of ladies-in-waiting help Mirren through an impressive, onstage costume change that trims forty-three years; and we see the silhouette of her first prime minister, Winston Churchill. Daldry gives Dakin Matthews a grand reveal, almost as if the silhouette of Alfred Hitchcock sprang to life. (This was presumably effective in not-so-merry olde England, but at the press preview attended it was clear that a major portion of the patrons had no idea who this Mr. Churchill was.)

That's the framework. Between ministers, Mirren has costume and wig changes; some onstage, some off, and some rather remarkable--but there's something faulty when one of the major highlights of an entertainment are the costume changes. (The most memorable element of the recent musical Cinderella, alas, was a costume change--which kept people talking but was indicative of the lackluster show itself.) Morgan also gives us a running character he calls "Young Elizabeth"--played at the performance attended by Sadie Sink, who alternates in the role with Elizabeth Teeter--who talks to one servant or other (and eventually her elder self) about how she would rather be able to go outside and play like all the other girls and boys.

The "imaginary conversations from history" nature of things is interrupted by the appearance of Harold Wilson, the Labour minister who served from 1964-70 and 1974-76. Wilson has an awkward, bull-in-the-china-shop scene in the first act, and a highly amusing scene with the queen in Scotland, in which he describes the Queen's Balmoral Castle as a "Rheinland Schloss." (He continually kids the Regent about her family's Germanic heritage.) The play ends with a third Wilson encounter, this one moving and emotionally affecting.

I can't say whether the Wilson scenes are better than the rest of the play because of the actor, Richard McCabe; or whether Mr. McCabe, who won the Olivier Award for this performance (as did Mirren), sparks the play alive because of the writing. In any event, Wilson is the only Minister up there created as more than a revue sketch. In fact, Elizabeth and Wilson--as drawn by Morgan--could populate their own play, and it might well be as compelling as Frost/Nixon.

Mr. McCabe is a treat to watch. So, to a lesser extent, is Michael Elwyn as Anthony Eden. His participation is restricted to one, short scene; but it offers high stakes writing, centering on the Suez crisis of 1956, which tarnished the United Kingdom's place in the postwar world and caused Eden's resignation in disgrace. The Suez scene, following Balmoral and followed by the Margaret Thatcher sequence, makes the second act far more involving than the first. This despite the fact that Judith Ivey, who storms on like a Texan Thatcher, seems somewhat out of place (although this might be a question of the writing).

So look to The Audience for an audience with Helen Mirren, dressed and coiffed as Elizabeth II. An audience with Helen Mirren makes a fine night's entertainment, but not--in this case--a compelling dramatic event.

You can watch a clip of Dame Helen's acceptance speech from the 2015 Tony Awards when she was voted Best Leading Actress. She also won the Olivier Award for this role in 2013.

After the show, when Brooke and I were leaving the theater, we saw that barricades had already been erected either side of the stage door and a car was parked, ready and waiting, at the curb. Brooke offered to stand with me if I had my heart set on seeing Dame Helen, but I declined. I decided that it was best to recall her as she was on the stage, rather than when being hounded by autograph seekers.

So we turned away and began to walk down the block on our way to the Rum House for some much anticipated cocktails. Note: I had my very first Pimm's Cup. Yumm.

However, we'd only gone a few steps towards the next door theatre when we found that the actors who'd appeared in that play were already on their way out. I stood on tip toes and craned my neck in order see the actor who was causing such a stir.

Brooke: Can you see who it it?

Me: Yes.

Brooke: Well, who is it?

Me: Bill Nighy!

Brooke: Who?

Me: A British actor. He's been in Best Exotic Marigold Hotel, Pirates of the Caribean. You'd know him if you could see him, he looks exactly like himself! Too bad you're too short to see. We'll Google him when we get to the Rum House.

Bill Nighy is starring in Skylight with Carey Mulligan

New York was wonderful, as it turned out, and it was great to have four whole days alone with Brooke. Still, I didn't see myself returning any time soon - until I read that Colin Firth is set to play Henry Higgins in the Broadway revival of My Fair Lady.

Published on July 05, 2015 23:00

July 3, 2015

WATERLOO'S AFTERMATH, PART ONE

THE BATTLE OF WATERLOO'S AFTERMATH

As evening approached on June 18, 1815, the Allied forces were repelling the attack of the French Imperial Garde in the center and the Prussian forces had arrived from the east.

The Prussians attack Plancenoit by German painter Adolph Northen (1828-1876)

The arrival of the Prussians was timely indeed. The Prussians took the hamlet of Plancenoit and soon, the French forces were fleeing in disarray, leaving equipment and wounded behind in their haste.

Napoleon at Waterlooby Charles de Steuben, (1788-1856)

Napoleon at Waterlooby Charles de Steuben, (1788-1856)

Meeting of Wellington and Blücherdetail of mural in Palace of Westminster (Houses of Parliament) by Irish Artist Daniel Maclise (1806-1870), completed 1858

Meeting of Wellington and Blücherdetail of mural in Palace of Westminster (Houses of Parliament) by Irish Artist Daniel Maclise (1806-1870), completed 1858

Late in the evening after the battle, Blücher and Wellington met at the inn La Belle Alliance and shook hands. In a great ironic twist, the two victorious generals spoke in the language of their enemy – the only language they both knew was French, though Blücher supposedly only knew a few words: “Mon Dieu, quelle affaire!”

Royal Gallery, Palace of Westminster, London

They decided Wellington’s troops should rest up, bury the dead, and then come toward France. The Prussians, relatively fresh, would pursue the French army.The two victorious generals met and agreed the Prussians woould continue to pursue the French troops south toward France. The Allied troops would bury the dead, treat the wounded, rest up and catch up soon. Neither man probably realized that for the most part, Napoleon was finished and they would be taking over Paris in weeks.

Prussians Capture Napoleon's Carriage

Prussians Capture Napoleon's Carriage

In the evening of the 18th, Prussian troops captured Napoleon’s carriage which he had to abandon and flee on horseback. Later the carriage was displayed in London where it was a famous attraction; it later was part of Madame Tussaud’s wax museum, but was destroyed in a fire there in 1925.

Thomas Rowlandson's 1816 version of the display at Bullock's Museum

Thomas Rowlandson's 1816 version of the display at Bullock's Museum

Though the battle had been won and the Prussian troops were chasing the remnants of Napoleon’s armies south toward France, more battles were expected in the coming days. Perhaps no one would have predicted it was, for all practical purposes, over – or would be in a couple of weeks. There was resistance and further fighting, but it was minimal, on a Napoleonic scale, that is.

Wellington crosses the battlefield

Wellington crosses the battlefield

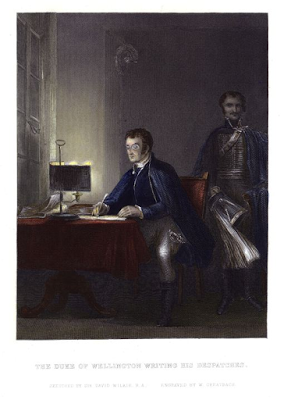

The Duke of Wellington rode through the carnage back to his headquarters in the village of Waterloo where he would write his despatch to Lord Bathurst in London declaring victory. Later the Duke of Wellington said, “I hope to God I have fought my last battle…I am wretched even at the moment of victory, and I always say that next to a battle lost, the greatest misery is a battle gained.”

Waterloo by Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775 - 1851)

Waterloo by Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775 - 1851)

This painting by Turner was created after he toured the battlefield and sketched the scene. It emphasizes the tragedy of so many deaths, so many lost forever. It was the first battle in which Napoleon faced Wellington, and for both men, indeed their last military battle. The Battle of Waterloo left 9,500 dead; 32,000 wounded.

Battle of Waterloo by Irish painter William Sadler II (1782-1839)

Battle of Waterloo by Irish painter William Sadler II (1782-1839)

The Morning After the Battle by John Heaviside Clark

The Morning After the Battle by John Heaviside Clark

On the battlefield, there were tens of thousands of dead and dying men and horses. Thieves crept among the bodies, robbing them of anything valuable. Parties of soldiers collected the wounded and took them to field hospitals. The dead were buried, sometimes in mass graves. The army surgeons were exhausted having spent the battle and the night tending the injured.

Fitzroy Somerset, later 1st Baron Raglan, by William Salter

Fitzroy Somerset, later 1st Baron Raglan, by William Salter

One of Wellington’s ADCs, Fitzroy Somerset (1788-1855), had his right arm amputated. Before they carried off the arm, he demanded to have the ring his wife (one of the Duke’s nieces) had given him removed from the lost hand. He learned to write with his left hand and was a secretary to Wellington for many years. He was named 1st Baron Raglan in 1852 and led the British Army in the Crimean War. He died before the Allied victory at Sevastopol was complete, partly of depression over criticism of his conduct of the war.

General Henry Paget, 1st Marquess of Anglesey, 1815by artist Peter Edward Stroehling (1768-1826)

General Henry Paget, 1st Marquess of Anglesey, 1815by artist Peter Edward Stroehling (1768-1826)

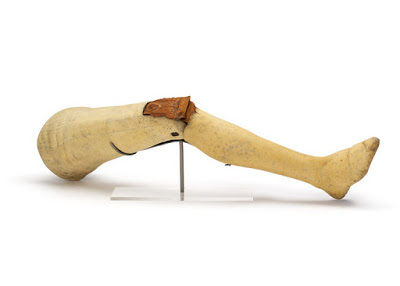

Another famous Waterloo amputation was Paget’s leg. Henry Paget, Earl of Uxbridge (soon to be Marquess of Anglesey), commanded the cavalry at Waterloo. He was seated on his horse talking to Wellington near the conclusion of the battle when his leg was shattered by a cannon shot. He said, "By God, sir, I've lost my leg. The Duke said, "By God, sir, so you have!"

Surgical Saw and bloodied glove from Waterloo

Surgical Instruments

Surgical Instruments

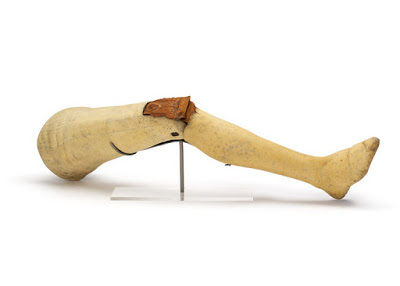

Artificial leg of Marquess of Anglesey

Artificial leg of Marquess of Anglesey

Waterloo Teeth for more relics from Waterloo 200, click hereOne of the gruesome aspects was the collection of the teeth. It was done after every battle in those days, as the teeth were valuable and much better than most false teeth – for many years, dentists advertised Waterloo Teeth.

Waterloo Teeth for more relics from Waterloo 200, click hereOne of the gruesome aspects was the collection of the teeth. It was done after every battle in those days, as the teeth were valuable and much better than most false teeth – for many years, dentists advertised Waterloo Teeth.

Wounded arriving in Brussels; Excerpt from Sir Walter Scott's Poem The Field of WaterlooThe wounded shew'd their mangled plightIn token of the unfinish'd fight,And from each anguish-laden wainThe blood-drops laid the dust like rain!

Wounded arriving in Brussels; Excerpt from Sir Walter Scott's Poem The Field of WaterlooThe wounded shew'd their mangled plightIn token of the unfinish'd fight,And from each anguish-laden wainThe blood-drops laid the dust like rain!

Many of the wounded were carried in carts (aka wains) into Brussels where thousands were nursed in makeshift hospitals and homes. Some of these men were luckier than those carried directly into field hospitals, as in the open air they were much less exposed to infection than in the crowded piles of dying in the hospitals.

After meeting with Blücher, the Duke returned to the village of Waterloo and wrote his despatches to Lord Bathurst and the Prince Regent. When the despatches were ready, on June 19, Wellington asked Major Henry Percy, either (according to which account you believe) the only unwounded ADC or the least-wounded of the eight ADCs Wellington had on June 18, to take the despatches and the captured Eagle standards and flags to London.

Jacket worm by Henry Percy when on the battlefield and delivering the despatch to London

Jacket worm by Henry Percy when on the battlefield and delivering the despatch to London

Percy got a chaise to the port of Ostend and embarked on the brig HMS Peruvian. Some accounts tell of the becalmed ship and the completion of the voyage by rowing – the Captain James White RN and Percy, with several other sailors, taking the oars themselves. From their landing at Broadstairs, Kent, about 3 pm on June 21, Percy hurried to London, changing horses at Canterbury, Sittingbourne, and Rochester. At first he could not find Lord Bathurst or Prime Minister Lord Liverpool. But with the French Eagles of the 45th and 105th sticking out of the windows of the carriage, they soon attracted a crowd, following them and cheering.

A French Eagle as on the top of the battle flags

A French Eagle as on the top of the battle flags

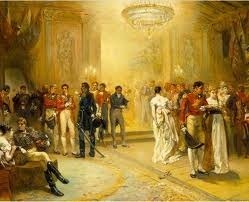

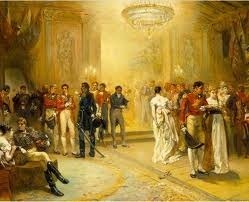

Eventually he found the officials and together they carried the news and the Eagles to #14 (or #16 in some accounts) St. James’s Square, the home of Mr. and Mrs. Boehm who were hosting a grand party for the Prince Regent and his brother the Duke of York, C-in-C of the Army.

The Boehm residence, St. James Square, today the East India United Service Club

The Boehm residence, St. James Square, today the East India United Service Club

According to most accounts, the excited crowds following Percy’s mad dash around London were heard by those at the party. When the disheveled Percy, still in blood-stained uniform, came inside and laid the Eagles at the Regent’s feet, the Prince immediately promoted him to Colonel Percy. The Prince Regent withdrew to read the despatches and returned in tears at the carnage, but elated at the victory.

An artist's version of Presenting the Eagles; actually there were only two

An artist's version of Presenting the Eagles; actually there were only two

As the party dispersed without the planned dancing or supper, Mrs. Boehm was said to have observed that it would have been much better to have waited until after the party to present the despatches. No one else agreed of course. Mr. Boehm later died bankrupt. Mrs. Boehm lived out her life in a Grace and Favor apartment at Hampton Court.

Major Henry Percy (1785-1825)

Major Henry Percy (1785-1825)

Major, now Colonel Percy, retired in 1821, and became a member of the House of Commons in 1823; however, he died only a year later, age 40.

Nathan Rothschild (1777-1836)

Nathan Rothschild (1777-1836)

Among the many legends that have grown around the Battle of Waterloo, perhaps none is more controversial and even inflammatory than the story of the Rothschild fortune – or lack of it. Some versions say that banker Nathan Rothschild, who had been providing gold to the British government through his network of relatives in banking houses on the continent, learned about the Waterloo victory before anyone else in London and made a killing in stocks and/or bonds by buying low when hopes were dim and selling high when victory had been secured. Various versions of the story have him gaining the knowledge from his company spies at the exiled entourage of Louis XVIII, another that he communicated with the continent by carrier pigeon. Many other researchers claim all such stories are bunk, inspired by jealousy and anti-Semitism, even fueled by Nazi propaganda during WWII. A careful study of the variable rates in British markets of the immediate period around Waterloo would prove no one made a killing in stocks, consols, or bonds of any kind, many conclude.Whatever the arguments, the Rothschild brothers had long proved their ability to handle financial matters on behalf of business, government and their own interests. Perhaps no special circumstances are needed to account for their wealth.

Chelsea Pensioners by Sir David Wilkie

Chelsea Pensioners by Sir David Wilkie

A happier story is the arrival of the Waterloo despatch at Chelsea Hospital where copies were read by retired soldiers. This famous painting, commissioned from artist David Wilkie by the Duke of Wellington, completed in 1822, hangs in Apsley House.

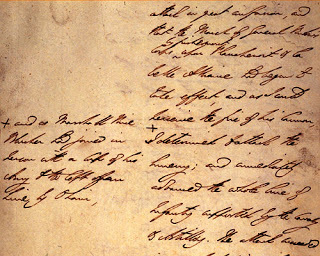

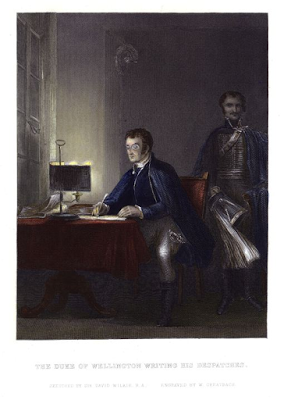

An excerpt from the Waterloo Despatch in Wellington's hand

An excerpt from the Waterloo Despatch in Wellington's hand

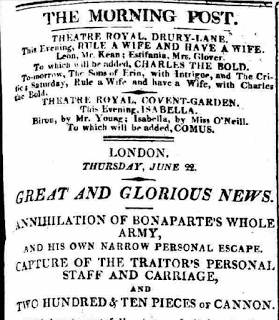

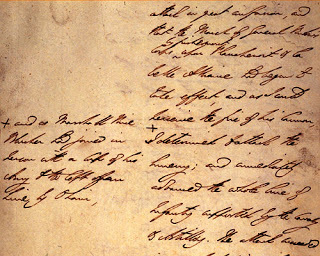

From The Morning Post, 22 June, 1915

From The Morning Post, 22 June, 1915

To read the official publication of the Despatch in the London Gazette, click here.

Re-enactment of despatch delivery. 2015

Re-enactment of despatch delivery. 2015

For an account of the reenactment of the delivery of the Wellington despatch, click here.

IN WATERLOO'S AFTERMATH, PART TWO, WE WILL DEAL WITH THE DISPOSAL OF NAPOLEON, NEXT WEEK.

As evening approached on June 18, 1815, the Allied forces were repelling the attack of the French Imperial Garde in the center and the Prussian forces had arrived from the east.

The Prussians attack Plancenoit by German painter Adolph Northen (1828-1876)

The arrival of the Prussians was timely indeed. The Prussians took the hamlet of Plancenoit and soon, the French forces were fleeing in disarray, leaving equipment and wounded behind in their haste.

Napoleon at Waterlooby Charles de Steuben, (1788-1856)

Napoleon at Waterlooby Charles de Steuben, (1788-1856) Meeting of Wellington and Blücherdetail of mural in Palace of Westminster (Houses of Parliament) by Irish Artist Daniel Maclise (1806-1870), completed 1858

Meeting of Wellington and Blücherdetail of mural in Palace of Westminster (Houses of Parliament) by Irish Artist Daniel Maclise (1806-1870), completed 1858Late in the evening after the battle, Blücher and Wellington met at the inn La Belle Alliance and shook hands. In a great ironic twist, the two victorious generals spoke in the language of their enemy – the only language they both knew was French, though Blücher supposedly only knew a few words: “Mon Dieu, quelle affaire!”

Royal Gallery, Palace of Westminster, London

They decided Wellington’s troops should rest up, bury the dead, and then come toward France. The Prussians, relatively fresh, would pursue the French army.The two victorious generals met and agreed the Prussians woould continue to pursue the French troops south toward France. The Allied troops would bury the dead, treat the wounded, rest up and catch up soon. Neither man probably realized that for the most part, Napoleon was finished and they would be taking over Paris in weeks.

Prussians Capture Napoleon's Carriage

Prussians Capture Napoleon's CarriageIn the evening of the 18th, Prussian troops captured Napoleon’s carriage which he had to abandon and flee on horseback. Later the carriage was displayed in London where it was a famous attraction; it later was part of Madame Tussaud’s wax museum, but was destroyed in a fire there in 1925.

Thomas Rowlandson's 1816 version of the display at Bullock's Museum

Thomas Rowlandson's 1816 version of the display at Bullock's MuseumThough the battle had been won and the Prussian troops were chasing the remnants of Napoleon’s armies south toward France, more battles were expected in the coming days. Perhaps no one would have predicted it was, for all practical purposes, over – or would be in a couple of weeks. There was resistance and further fighting, but it was minimal, on a Napoleonic scale, that is.

Wellington crosses the battlefield

Wellington crosses the battlefieldThe Duke of Wellington rode through the carnage back to his headquarters in the village of Waterloo where he would write his despatch to Lord Bathurst in London declaring victory. Later the Duke of Wellington said, “I hope to God I have fought my last battle…I am wretched even at the moment of victory, and I always say that next to a battle lost, the greatest misery is a battle gained.”

Waterloo by Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775 - 1851)

Waterloo by Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775 - 1851)This painting by Turner was created after he toured the battlefield and sketched the scene. It emphasizes the tragedy of so many deaths, so many lost forever. It was the first battle in which Napoleon faced Wellington, and for both men, indeed their last military battle. The Battle of Waterloo left 9,500 dead; 32,000 wounded.

Battle of Waterloo by Irish painter William Sadler II (1782-1839)

Battle of Waterloo by Irish painter William Sadler II (1782-1839) The Morning After the Battle by John Heaviside Clark

The Morning After the Battle by John Heaviside ClarkOn the battlefield, there were tens of thousands of dead and dying men and horses. Thieves crept among the bodies, robbing them of anything valuable. Parties of soldiers collected the wounded and took them to field hospitals. The dead were buried, sometimes in mass graves. The army surgeons were exhausted having spent the battle and the night tending the injured.

Fitzroy Somerset, later 1st Baron Raglan, by William Salter

Fitzroy Somerset, later 1st Baron Raglan, by William SalterOne of Wellington’s ADCs, Fitzroy Somerset (1788-1855), had his right arm amputated. Before they carried off the arm, he demanded to have the ring his wife (one of the Duke’s nieces) had given him removed from the lost hand. He learned to write with his left hand and was a secretary to Wellington for many years. He was named 1st Baron Raglan in 1852 and led the British Army in the Crimean War. He died before the Allied victory at Sevastopol was complete, partly of depression over criticism of his conduct of the war.

General Henry Paget, 1st Marquess of Anglesey, 1815by artist Peter Edward Stroehling (1768-1826)

General Henry Paget, 1st Marquess of Anglesey, 1815by artist Peter Edward Stroehling (1768-1826)Another famous Waterloo amputation was Paget’s leg. Henry Paget, Earl of Uxbridge (soon to be Marquess of Anglesey), commanded the cavalry at Waterloo. He was seated on his horse talking to Wellington near the conclusion of the battle when his leg was shattered by a cannon shot. He said, "By God, sir, I've lost my leg. The Duke said, "By God, sir, so you have!"

Surgical Saw and bloodied glove from Waterloo

Surgical Instruments

Surgical Instruments Artificial leg of Marquess of Anglesey

Artificial leg of Marquess of Anglesey Waterloo Teeth for more relics from Waterloo 200, click hereOne of the gruesome aspects was the collection of the teeth. It was done after every battle in those days, as the teeth were valuable and much better than most false teeth – for many years, dentists advertised Waterloo Teeth.

Waterloo Teeth for more relics from Waterloo 200, click hereOne of the gruesome aspects was the collection of the teeth. It was done after every battle in those days, as the teeth were valuable and much better than most false teeth – for many years, dentists advertised Waterloo Teeth. Wounded arriving in Brussels; Excerpt from Sir Walter Scott's Poem The Field of WaterlooThe wounded shew'd their mangled plightIn token of the unfinish'd fight,And from each anguish-laden wainThe blood-drops laid the dust like rain!

Wounded arriving in Brussels; Excerpt from Sir Walter Scott's Poem The Field of WaterlooThe wounded shew'd their mangled plightIn token of the unfinish'd fight,And from each anguish-laden wainThe blood-drops laid the dust like rain!Many of the wounded were carried in carts (aka wains) into Brussels where thousands were nursed in makeshift hospitals and homes. Some of these men were luckier than those carried directly into field hospitals, as in the open air they were much less exposed to infection than in the crowded piles of dying in the hospitals.

After meeting with Blücher, the Duke returned to the village of Waterloo and wrote his despatches to Lord Bathurst and the Prince Regent. When the despatches were ready, on June 19, Wellington asked Major Henry Percy, either (according to which account you believe) the only unwounded ADC or the least-wounded of the eight ADCs Wellington had on June 18, to take the despatches and the captured Eagle standards and flags to London.

Jacket worm by Henry Percy when on the battlefield and delivering the despatch to London

Jacket worm by Henry Percy when on the battlefield and delivering the despatch to LondonPercy got a chaise to the port of Ostend and embarked on the brig HMS Peruvian. Some accounts tell of the becalmed ship and the completion of the voyage by rowing – the Captain James White RN and Percy, with several other sailors, taking the oars themselves. From their landing at Broadstairs, Kent, about 3 pm on June 21, Percy hurried to London, changing horses at Canterbury, Sittingbourne, and Rochester. At first he could not find Lord Bathurst or Prime Minister Lord Liverpool. But with the French Eagles of the 45th and 105th sticking out of the windows of the carriage, they soon attracted a crowd, following them and cheering.

A French Eagle as on the top of the battle flags

A French Eagle as on the top of the battle flagsEventually he found the officials and together they carried the news and the Eagles to #14 (or #16 in some accounts) St. James’s Square, the home of Mr. and Mrs. Boehm who were hosting a grand party for the Prince Regent and his brother the Duke of York, C-in-C of the Army.

The Boehm residence, St. James Square, today the East India United Service Club

The Boehm residence, St. James Square, today the East India United Service Club According to most accounts, the excited crowds following Percy’s mad dash around London were heard by those at the party. When the disheveled Percy, still in blood-stained uniform, came inside and laid the Eagles at the Regent’s feet, the Prince immediately promoted him to Colonel Percy. The Prince Regent withdrew to read the despatches and returned in tears at the carnage, but elated at the victory.

An artist's version of Presenting the Eagles; actually there were only two

An artist's version of Presenting the Eagles; actually there were only twoAs the party dispersed without the planned dancing or supper, Mrs. Boehm was said to have observed that it would have been much better to have waited until after the party to present the despatches. No one else agreed of course. Mr. Boehm later died bankrupt. Mrs. Boehm lived out her life in a Grace and Favor apartment at Hampton Court.

Major Henry Percy (1785-1825)

Major Henry Percy (1785-1825)Major, now Colonel Percy, retired in 1821, and became a member of the House of Commons in 1823; however, he died only a year later, age 40.

Nathan Rothschild (1777-1836)

Nathan Rothschild (1777-1836)Among the many legends that have grown around the Battle of Waterloo, perhaps none is more controversial and even inflammatory than the story of the Rothschild fortune – or lack of it. Some versions say that banker Nathan Rothschild, who had been providing gold to the British government through his network of relatives in banking houses on the continent, learned about the Waterloo victory before anyone else in London and made a killing in stocks and/or bonds by buying low when hopes were dim and selling high when victory had been secured. Various versions of the story have him gaining the knowledge from his company spies at the exiled entourage of Louis XVIII, another that he communicated with the continent by carrier pigeon. Many other researchers claim all such stories are bunk, inspired by jealousy and anti-Semitism, even fueled by Nazi propaganda during WWII. A careful study of the variable rates in British markets of the immediate period around Waterloo would prove no one made a killing in stocks, consols, or bonds of any kind, many conclude.Whatever the arguments, the Rothschild brothers had long proved their ability to handle financial matters on behalf of business, government and their own interests. Perhaps no special circumstances are needed to account for their wealth.

Chelsea Pensioners by Sir David Wilkie

Chelsea Pensioners by Sir David WilkieA happier story is the arrival of the Waterloo despatch at Chelsea Hospital where copies were read by retired soldiers. This famous painting, commissioned from artist David Wilkie by the Duke of Wellington, completed in 1822, hangs in Apsley House.

An excerpt from the Waterloo Despatch in Wellington's hand

An excerpt from the Waterloo Despatch in Wellington's hand From The Morning Post, 22 June, 1915

From The Morning Post, 22 June, 1915To read the official publication of the Despatch in the London Gazette, click here.

Re-enactment of despatch delivery. 2015

Re-enactment of despatch delivery. 2015For an account of the reenactment of the delivery of the Wellington despatch, click here.

IN WATERLOO'S AFTERMATH, PART TWO, WE WILL DEAL WITH THE DISPOSAL OF NAPOLEON, NEXT WEEK.

Published on July 03, 2015 00:30

June 30, 2015

GUEST BLOGGER JO MANNING VISITS POLESDEN LACEY IN SURREY

AND HERE IS POLESDEN LACEY, A STATELY HOME IN SURREY WITH A BEAUTIFUL VIEW AND A CONNECTION TO REGENCY PLAYWRIGHT AND POLITICIAN RICHARD BRINSLEY SHERIDAN…

Polesden Lacey, the Edwardian country estate on a spectacular natural site overlooking a deep valley in Great Bookham, near Dorking, in Surrey, is best known for its influential hostess-with-the-mostest, Mrs Ronald Greville (aka “Mrs Ronnie”), who was an intimate of the royal family and anyone else who could claim to be anyone at the turn of the 20thcentury.

But it actually has a very long history dating back to Roman times – and, indeed, would it not have been a perfect site for a Roman temple? – though documentation of buildings on that site date back only to the 14thcentury or thereabouts.

One of Oliver Cromwell’s roundhead officers – the Parliamentarians who fought against the Cavalier forces of King Charles I in the English Civil War – bought this divine property in 1630, keeping the existing farm and constructing a new residence in situ.

The Regency-era playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan – after a long line of other owners and leaseholders – came into the picture in 1797, when his trustees, one Lord Grey and a Mr Whitbread, bought the Polesden Lacey lease for 12,384 pounds, using the 8,000 pound dowry of Sheridan’s second wife, Hester Jane Ogle, and money raised from the sale of shares in the Drury Lane Theatre, which he owned. (another source stated a higher price of 20,000 pounds was paid.)

The Rivals and The School for Scandal are Sheridan’s best-known plays, still widely performed today. In my opinion, the world lost a literate and witty wordsmith when Sheridan decided to enter the world of Whig politics, but there was perhaps another motive to his service in parliament. As an MP he was safe against arrest for debt, and the playwright was chronically in debt. When he lost his seat in 1812 his creditors showed up in droves to claim what was owed them. Hence the loss of Polesden Lacey after a leasehold that spanned almost twenty years.

The breathtakingly beautiful Elizabeth Lynley, from the painting by Thomas Gainsborough. Elizabeth was from a very well-known family of musicians in Bath with whom the painter was extremely friendly; he painted many family members.

The breathtakingly beautiful Elizabeth Lynley, from the painting by Thomas Gainsborough. Elizabeth was from a very well-known family of musicians in Bath with whom the painter was extremely friendly; he painted many family members.

This sympathetic piece in the theatrehistory.com website sums him up:

“The real sheridan was not a pattern of decorous respectabilty, but we may fairly believe that he was very far from being the Sheridan of vulgar legend. Against stories about his reckless management of his affairs we must set the broad facts that he had no source of income but the Drury Lane Theatre, that he bore from it for thirty years all the expenses of a fashionable life, and the theatre was twice rebuilt during his proprietorship, the first time (1791) on account of its having been pronounced unsafe, and the second (1809) after a disastrous fire. Enough was lost in this way to account ten times over for all his debts. The records of his wild bets in the betting book of Brooks’ Club date from the years after the loss, in1792, of his first wife [the incomparable beauty Elizabeth Lynley] … the reminiscences of his son’s tutor, Mr Smyth, show anxious and fidgetty [sic] family habits curiously at variance with the accepted tradition of his imperturbable recklessness. He died on the 7thof July 1816, and was buried with great pomp in Westminster Abbey.”

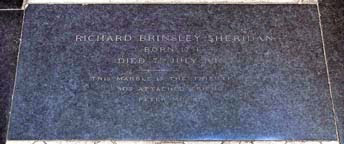

If you are so inclined, you can pay Sheridan a visit in the Poets’ Corner at Westminster Abbey the next time you are in London:

Although Sheridan began to demolish parts of the house around 1814, he did not get very far owing to burgeoning ill health and those always-problematic finances. He is credited, however, with extending the charming Long Walk to 1,300 feet from 900 feet. This walk was first laid out along the valley in 1761 on the 1,400 acre estate and it remains a very popular hiking trail with national trust visitors from far and wide as well as with local families and walking groups. Parallel to the Long Walk is another, called the Nun’s Walk, which is lined with beech, yew, and holly trees. (And, yes, for those of you who like to know these things, there is even a ha-ha, below a yew hedge that marks the garden’s boundary.)

Sheridan also made some attempts at landscaping the Polesden Lacey garden. In respect to that garden – and to his legendary reputation as a ladies’ man – the National Trust booklet attributes this quote to him: “Won’t you come into the garden? I would like my roses to see you.” Sheridan to a beautiful female guest at Polesden Lacey

The text in that booklet emphasizes how much Sheridan loved his country home, which he called “the nicest place, within a prudent distance of town, in England.” Notwithstanding his creditors, and the dual responsibilities of managing the Drury Lane Theatre and his parliamentary duties, he surely relished his role of country landlord and entertained, as they say, lavishly.

This “portrait of a gentleman”, by John Hoppner, has been traditionally identified as that of Richard Brinsley Sheridan

This “portrait of a gentleman”, by John Hoppner, has been traditionally identified as that of Richard Brinsley Sheridan

But, alas, the property was sold again, to a Joseph Bonsor (1768-1835), who commissioned the period’s master builder, Thomas Cubitt, to design and erect a new house, and this redesign formed the nexus of the current stately home. According to Bonsor’s obituary in The Gentleman’s Magazine , he was a self-made man, “the founder of his own fortune.” His success in the wholesale stationery trade enabled him to secure the sale of Polesden Lacey from Sheridan’s son in 1818.

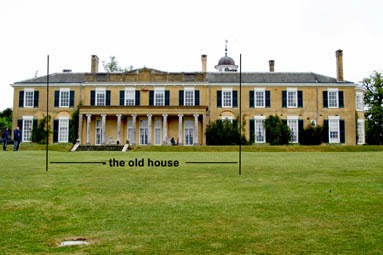

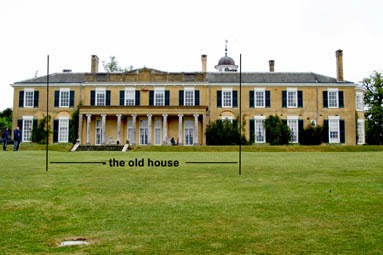

Thomas Cubitt rebuilt the house in the neo-classical style. On the south front of the house, part of Cubitt’s villa is still visible: six bay windows with an Ionic-columned portico.

Some repairs taking place recently on the neo-classical south front of Polesden Lacey (what you don’t see is the graffiti chalked by schoolchildren on the steps leading to the great lawn)

Some repairs taking place recently on the neo-classical south front of Polesden Lacey (what you don’t see is the graffiti chalked by schoolchildren on the steps leading to the great lawn)

The next owner in line was a prominent Scottish physician (and, yes, a Scots theme runs through this history) named Sir Walter Farquahar. It was this good doctor who extended the walled garden and put more order into the various plantings. But more was to come for this splendid parcel of land.

In 1902 the estate became the property of Sir Clinton Dawkins, who commissioned the architect Sir Ambrose Macdonald Poynter, a major London architect whose grandfather was also an architect (a co-founder of the Institute of British Architects whose father was a distinguished painter) to make extensive renovations to Polesden Lacey. He went on to build the Royal Over-Seas League, Park Place, St James’s, a few years later.

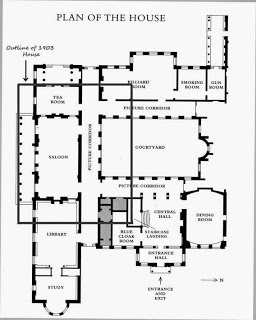

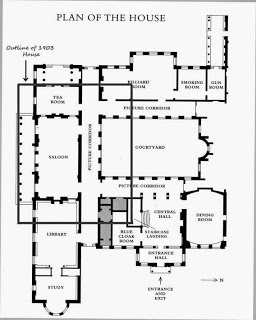

And then, in 1906, along came the redoubtable Mrs Greville… who employed the architectural firm of Mewes and Davis (the designers of the Ritz Hotel in London) and the interior decorating firm of white, Allom & Co., to further gild the lily this house was becoming. (See below for the changes and expansions from the 1903 house to the present-day.)

This gives an even better idea of the expansion!

This gives an even better idea of the expansion!

Some family background… Margaret Helen Anderson was born out of wedlock in 1863 to a Scottish brewery multimillionaire named William Mc Ewan and a woman named Helen Anderson. Mrs Anderson was said to be married to – or lived with – a man named William Anderson, who was a porter employed in Mc Ewan’s brewery. Mrs Anderson and Mr Mc Ewan wed after the death of Mr Anderson in1885. On Mc Ewan’s death in 1913, Margaret inherited his entire estate, becoming one of the wealthiest women in Britain.

This gorgeous portrait (above) painted in 1891 by Carolus-Duran (who was John Singer Sargent’s teacher) sits on the landing of the central hall, on the way to the dining room… exactly where MrsGgreville loved to make a dramatic entrance and meet her guests as they went in to dinner…

This gorgeous portrait (above) painted in 1891 by Carolus-Duran (who was John Singer Sargent’s teacher) sits on the landing of the central hall, on the way to the dining room… exactly where MrsGgreville loved to make a dramatic entrance and meet her guests as they went in to dinner…

Margaret had been married in 1891 to the Honorable Ronald Henry Fulke Greville, a handsome gentleman identified as “a member of the racy Marlborough House set” who was said to have been “witty and good-natured.” Photos show him with a rakish moustache and piercing light blue eyes. He was the eldest son of the 2nd Lord Greville and a conservative MP for Bradford as well as a Captain in the 1st Life Guards. Greville and Margaret were, by all accounts, happily wed for seventeen years, until he died suddenly from complications of an emergency operation. She never remarried, though, as an immensely wealthy widow she probably had a number of men desirous of being in her company.

Why is this National Trust property, Polesden Lacey, important?

Well, for one, it is so closely associated with events in British history and with prominent historic personages – like Sheridan, like the assorted royals and foreign visitors with whom the Grevilles interacted – and Mrs Greville herself was an amazing character whose talent lay in bringing people together in an intimate salon setting and who was said to have had a remarkably sharp and witty tongue.

We would, I think, like to know much more about what she thought about what and whom, living through those two horrific world wars that upended British society as she had known it, but, as all of her personal letters, diaries and other papers were destroyed after her death, at her request...

One can be sure. then that the many things that swirled about her, all the racy and intriguing political/private/scandalous goings-on/et al., of the Edwardian era and the reign of King George VI (father to the present Queen, Elizabeth II) will never see her viewpoint’s light of day. It was too bad, because as an intimate of so many well-connected and powerful people, she was in a position to hear and see a great many things that could be illuminating, even obliquely.

She was, for one, very close to Elizabeth, the Queen Mother – Elizabeth and George VII (before he became king) spent part of their honeymoon at Polesden Lacey -- and Mrs Greville left the Queen Mother and her daughters the Princesses Elizabeth and Margaret, her most precious jewels…one a diamond necklace purported to have been owned by the French Queen Marie Antoinette.

The widely-held expectation, in fact, was that she was going to leave Polesden Lacey to the House of Windsor in her will. (She and Ronald had no children.) However, she did not do that, gifting it to the National Trust instead.

(For those who want to know and see a little more than can be covered in this piece, there is an extensively-illustrated biography, published by the National Trust in 2013, written by Sian Evans: Mrs Ronnie: The Society Hostess Who Collected Kings. )

The Paterson Children, by Sir Henry Raeburn

The Paterson Children, by Sir Henry Raeburn

One of the outstanding collections amongst the many exquisite and valuable collections at Polesden Lacey that I must mention hearkens back to that Scottish connection I mentioned previously, and those are the remarkable paintings in the dining room, many of them by the Scottish portraitists Sir Henry Raeburn (a favorite of King George IV), Allan Ramsay (a favorite of King George III), and by other Scots of lesser renown.

So, again, what is so special about Polesden Lacey?

Along with the above glorious paintings (and the fabulous collections of miniature paintings, ceramics, etc., and Polesden Lacey’s place in history and association with historical personages, it is also (and this is not such a minor thing), as the National Trust describes it:

“an English estate in the traditional manner – a blend of open lawns and enclosed rose gardens, mature native trees and exotic species from overseas, formal terraces and informal shrubs.... An appealing yet practical complete landscape.”

And this is very true:

“the estate was bought by successive owners because it was beautiful… but…its maintenance was only possible because of Mrs Greville’s considerable personal fortune.”

We must not forget that we visitors (including this child from London pictured below and the many families lounging on deck chairs in the background and those walking all the beautiful trails) are much the richer for it, as its maintenance – keeping it beautiful – was possible only because of Mrs Ronnie’s considerable personal fortune and her concern for future generations. It’s in trust for everyone in Britain and all should be very grateful it passed on to the people of Britain and not to the royal family of Windsor.

Jo ManningPolesden lacey April 2015

Click here to read a 2012 Daily Mail article about the brouhaha surrounding pheasant shooting rights on the Estate.

Polesden Lacey, the Edwardian country estate on a spectacular natural site overlooking a deep valley in Great Bookham, near Dorking, in Surrey, is best known for its influential hostess-with-the-mostest, Mrs Ronald Greville (aka “Mrs Ronnie”), who was an intimate of the royal family and anyone else who could claim to be anyone at the turn of the 20thcentury.

But it actually has a very long history dating back to Roman times – and, indeed, would it not have been a perfect site for a Roman temple? – though documentation of buildings on that site date back only to the 14thcentury or thereabouts.

One of Oliver Cromwell’s roundhead officers – the Parliamentarians who fought against the Cavalier forces of King Charles I in the English Civil War – bought this divine property in 1630, keeping the existing farm and constructing a new residence in situ.

The Regency-era playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan – after a long line of other owners and leaseholders – came into the picture in 1797, when his trustees, one Lord Grey and a Mr Whitbread, bought the Polesden Lacey lease for 12,384 pounds, using the 8,000 pound dowry of Sheridan’s second wife, Hester Jane Ogle, and money raised from the sale of shares in the Drury Lane Theatre, which he owned. (another source stated a higher price of 20,000 pounds was paid.)

The Rivals and The School for Scandal are Sheridan’s best-known plays, still widely performed today. In my opinion, the world lost a literate and witty wordsmith when Sheridan decided to enter the world of Whig politics, but there was perhaps another motive to his service in parliament. As an MP he was safe against arrest for debt, and the playwright was chronically in debt. When he lost his seat in 1812 his creditors showed up in droves to claim what was owed them. Hence the loss of Polesden Lacey after a leasehold that spanned almost twenty years.

The breathtakingly beautiful Elizabeth Lynley, from the painting by Thomas Gainsborough. Elizabeth was from a very well-known family of musicians in Bath with whom the painter was extremely friendly; he painted many family members.

The breathtakingly beautiful Elizabeth Lynley, from the painting by Thomas Gainsborough. Elizabeth was from a very well-known family of musicians in Bath with whom the painter was extremely friendly; he painted many family members.

This sympathetic piece in the theatrehistory.com website sums him up:

“The real sheridan was not a pattern of decorous respectabilty, but we may fairly believe that he was very far from being the Sheridan of vulgar legend. Against stories about his reckless management of his affairs we must set the broad facts that he had no source of income but the Drury Lane Theatre, that he bore from it for thirty years all the expenses of a fashionable life, and the theatre was twice rebuilt during his proprietorship, the first time (1791) on account of its having been pronounced unsafe, and the second (1809) after a disastrous fire. Enough was lost in this way to account ten times over for all his debts. The records of his wild bets in the betting book of Brooks’ Club date from the years after the loss, in1792, of his first wife [the incomparable beauty Elizabeth Lynley] … the reminiscences of his son’s tutor, Mr Smyth, show anxious and fidgetty [sic] family habits curiously at variance with the accepted tradition of his imperturbable recklessness. He died on the 7thof July 1816, and was buried with great pomp in Westminster Abbey.”

If you are so inclined, you can pay Sheridan a visit in the Poets’ Corner at Westminster Abbey the next time you are in London:

Although Sheridan began to demolish parts of the house around 1814, he did not get very far owing to burgeoning ill health and those always-problematic finances. He is credited, however, with extending the charming Long Walk to 1,300 feet from 900 feet. This walk was first laid out along the valley in 1761 on the 1,400 acre estate and it remains a very popular hiking trail with national trust visitors from far and wide as well as with local families and walking groups. Parallel to the Long Walk is another, called the Nun’s Walk, which is lined with beech, yew, and holly trees. (And, yes, for those of you who like to know these things, there is even a ha-ha, below a yew hedge that marks the garden’s boundary.)

Sheridan also made some attempts at landscaping the Polesden Lacey garden. In respect to that garden – and to his legendary reputation as a ladies’ man – the National Trust booklet attributes this quote to him: “Won’t you come into the garden? I would like my roses to see you.” Sheridan to a beautiful female guest at Polesden Lacey

The text in that booklet emphasizes how much Sheridan loved his country home, which he called “the nicest place, within a prudent distance of town, in England.” Notwithstanding his creditors, and the dual responsibilities of managing the Drury Lane Theatre and his parliamentary duties, he surely relished his role of country landlord and entertained, as they say, lavishly.

This “portrait of a gentleman”, by John Hoppner, has been traditionally identified as that of Richard Brinsley Sheridan

This “portrait of a gentleman”, by John Hoppner, has been traditionally identified as that of Richard Brinsley SheridanBut, alas, the property was sold again, to a Joseph Bonsor (1768-1835), who commissioned the period’s master builder, Thomas Cubitt, to design and erect a new house, and this redesign formed the nexus of the current stately home. According to Bonsor’s obituary in The Gentleman’s Magazine , he was a self-made man, “the founder of his own fortune.” His success in the wholesale stationery trade enabled him to secure the sale of Polesden Lacey from Sheridan’s son in 1818.

Thomas Cubitt rebuilt the house in the neo-classical style. On the south front of the house, part of Cubitt’s villa is still visible: six bay windows with an Ionic-columned portico.

Some repairs taking place recently on the neo-classical south front of Polesden Lacey (what you don’t see is the graffiti chalked by schoolchildren on the steps leading to the great lawn)

Some repairs taking place recently on the neo-classical south front of Polesden Lacey (what you don’t see is the graffiti chalked by schoolchildren on the steps leading to the great lawn)

The next owner in line was a prominent Scottish physician (and, yes, a Scots theme runs through this history) named Sir Walter Farquahar. It was this good doctor who extended the walled garden and put more order into the various plantings. But more was to come for this splendid parcel of land.

In 1902 the estate became the property of Sir Clinton Dawkins, who commissioned the architect Sir Ambrose Macdonald Poynter, a major London architect whose grandfather was also an architect (a co-founder of the Institute of British Architects whose father was a distinguished painter) to make extensive renovations to Polesden Lacey. He went on to build the Royal Over-Seas League, Park Place, St James’s, a few years later.

And then, in 1906, along came the redoubtable Mrs Greville… who employed the architectural firm of Mewes and Davis (the designers of the Ritz Hotel in London) and the interior decorating firm of white, Allom & Co., to further gild the lily this house was becoming. (See below for the changes and expansions from the 1903 house to the present-day.)

This gives an even better idea of the expansion!

This gives an even better idea of the expansion!Some family background… Margaret Helen Anderson was born out of wedlock in 1863 to a Scottish brewery multimillionaire named William Mc Ewan and a woman named Helen Anderson. Mrs Anderson was said to be married to – or lived with – a man named William Anderson, who was a porter employed in Mc Ewan’s brewery. Mrs Anderson and Mr Mc Ewan wed after the death of Mr Anderson in1885. On Mc Ewan’s death in 1913, Margaret inherited his entire estate, becoming one of the wealthiest women in Britain.

This gorgeous portrait (above) painted in 1891 by Carolus-Duran (who was John Singer Sargent’s teacher) sits on the landing of the central hall, on the way to the dining room… exactly where MrsGgreville loved to make a dramatic entrance and meet her guests as they went in to dinner…

This gorgeous portrait (above) painted in 1891 by Carolus-Duran (who was John Singer Sargent’s teacher) sits on the landing of the central hall, on the way to the dining room… exactly where MrsGgreville loved to make a dramatic entrance and meet her guests as they went in to dinner…Margaret had been married in 1891 to the Honorable Ronald Henry Fulke Greville, a handsome gentleman identified as “a member of the racy Marlborough House set” who was said to have been “witty and good-natured.” Photos show him with a rakish moustache and piercing light blue eyes. He was the eldest son of the 2nd Lord Greville and a conservative MP for Bradford as well as a Captain in the 1st Life Guards. Greville and Margaret were, by all accounts, happily wed for seventeen years, until he died suddenly from complications of an emergency operation. She never remarried, though, as an immensely wealthy widow she probably had a number of men desirous of being in her company.

Why is this National Trust property, Polesden Lacey, important?

Well, for one, it is so closely associated with events in British history and with prominent historic personages – like Sheridan, like the assorted royals and foreign visitors with whom the Grevilles interacted – and Mrs Greville herself was an amazing character whose talent lay in bringing people together in an intimate salon setting and who was said to have had a remarkably sharp and witty tongue.

We would, I think, like to know much more about what she thought about what and whom, living through those two horrific world wars that upended British society as she had known it, but, as all of her personal letters, diaries and other papers were destroyed after her death, at her request...

One can be sure. then that the many things that swirled about her, all the racy and intriguing political/private/scandalous goings-on/et al., of the Edwardian era and the reign of King George VI (father to the present Queen, Elizabeth II) will never see her viewpoint’s light of day. It was too bad, because as an intimate of so many well-connected and powerful people, she was in a position to hear and see a great many things that could be illuminating, even obliquely.

She was, for one, very close to Elizabeth, the Queen Mother – Elizabeth and George VII (before he became king) spent part of their honeymoon at Polesden Lacey -- and Mrs Greville left the Queen Mother and her daughters the Princesses Elizabeth and Margaret, her most precious jewels…one a diamond necklace purported to have been owned by the French Queen Marie Antoinette.

The widely-held expectation, in fact, was that she was going to leave Polesden Lacey to the House of Windsor in her will. (She and Ronald had no children.) However, she did not do that, gifting it to the National Trust instead.

(For those who want to know and see a little more than can be covered in this piece, there is an extensively-illustrated biography, published by the National Trust in 2013, written by Sian Evans: Mrs Ronnie: The Society Hostess Who Collected Kings. )

The Paterson Children, by Sir Henry Raeburn

The Paterson Children, by Sir Henry RaeburnOne of the outstanding collections amongst the many exquisite and valuable collections at Polesden Lacey that I must mention hearkens back to that Scottish connection I mentioned previously, and those are the remarkable paintings in the dining room, many of them by the Scottish portraitists Sir Henry Raeburn (a favorite of King George IV), Allan Ramsay (a favorite of King George III), and by other Scots of lesser renown.

So, again, what is so special about Polesden Lacey?

Along with the above glorious paintings (and the fabulous collections of miniature paintings, ceramics, etc., and Polesden Lacey’s place in history and association with historical personages, it is also (and this is not such a minor thing), as the National Trust describes it:

“an English estate in the traditional manner – a blend of open lawns and enclosed rose gardens, mature native trees and exotic species from overseas, formal terraces and informal shrubs.... An appealing yet practical complete landscape.”

And this is very true:

“the estate was bought by successive owners because it was beautiful… but…its maintenance was only possible because of Mrs Greville’s considerable personal fortune.”

We must not forget that we visitors (including this child from London pictured below and the many families lounging on deck chairs in the background and those walking all the beautiful trails) are much the richer for it, as its maintenance – keeping it beautiful – was possible only because of Mrs Ronnie’s considerable personal fortune and her concern for future generations. It’s in trust for everyone in Britain and all should be very grateful it passed on to the people of Britain and not to the royal family of Windsor.

Jo ManningPolesden lacey April 2015

Click here to read a 2012 Daily Mail article about the brouhaha surrounding pheasant shooting rights on the Estate.

Published on June 30, 2015 23:30

June 28, 2015

STAY A WHILE AT HISTORIC COMBERMERE ABBEY

The Duke of Wellington was Godfather to the 2nd son of Viscount Combermere and attended his Christening in 1820, when he planted an oak tree in celebration of the event. Now, guests can stay in accommodations on the grounds and enjoy full access the property and historic gardens.

Stone Lodge ~

A Whole Estate to Explore in your ‘back garden’!

Combermere Estate lies on the Cheshire/Shropshire border and features a 143 acre lake, the largest in private ownership in Cheshire, and a total of 1,000 rolling acres. The medieval Cistercian Combermere Abbey is set in the heart of the Estate and was founded in 1133 by Hugh de Malbanc, Lord of Nantwich. It once had 22 monks in residence. During the Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1536 by Henry VIII, most of the monastic buildings were destroyed leaving only the Abbot’s Hall and in 1820 it was re-designed as a gothic mansion.

Famous occupants of Combermere Abbey include Elizabeth, Empress of Austria; William of Orange, Dr. Johnson and Mrs Thrale and Sir Stapleton Cotton, a brilliant General, who fought under Wellington at the Battle of Salamanca. The present occupants are Sarah Callander Beckett, who inherited the estate from her great grandfather, Sir Kenneth Crossley Bt, and her husband, Peter.

The North Wing of the Abbey is currently undergoing major restoration, following the successful enabling development award in 2013. The project will see the complete repair of the wing and transformation into a separate dwelling which will be offered as the bridal suite for wedding couples. The restoration is expected to complete in 2016.

In 1994, the restored 1837 Stables were opened as luxury holiday cottages and have since won awards and acclaim for their high standards. In 2011 the number of cottages was increased from 7 to 10, with the addition of three new stylish and contemporary cottages. The business was awarded a Gold Award from the Green Tourism Business Scheme and was Highly Commended at the inaugural Hudson’s Heritage Awards for their ‘Best Accommodation’ category.