Kristine Hughes's Blog, page 173

October 7, 2010

A Morning at the Milwaukee Art Museum

Victoria here, welcoming you to the Milwaukee Art Museum, one of my favorite hang-outs. In fact, I used to work here writing grant proposals for exhibitions and conservation projects. The building is the iconic winged structure on the shore of Lake Michigan designed by Spanish architect Santiago Calatrava, opened in 2001 as the second major addition to the original building by Eero Saarinen (1910–1961), a Finnish-American architect.

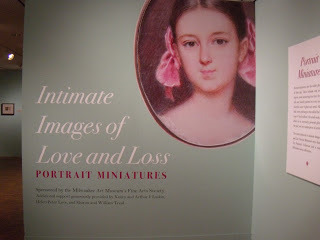

Victoria here, welcoming you to the Milwaukee Art Museum, one of my favorite hang-outs. In fact, I used to work here writing grant proposals for exhibitions and conservation projects. The building is the iconic winged structure on the shore of Lake Michigan designed by Spanish architect Santiago Calatrava, opened in 2001 as the second major addition to the original building by Eero Saarinen (1910–1961), a Finnish-American architect.  One of the current exhibitions on view at the MAM is Intimate Images of Love and Loss: Portrait Miniatures which continues through October 31, 2010. The Koss Gallery is filled with miniatures by British, American, French, Austrian and Argentinian artists and photographers. Click here for more information.

One of the current exhibitions on view at the MAM is Intimate Images of Love and Loss: Portrait Miniatures which continues through October 31, 2010. The Koss Gallery is filled with miniatures by British, American, French, Austrian and Argentinian artists and photographers. Click here for more information. One of my favorites is this portrait, A Young Girl, with her hair unbound and blowing in the wind. It was painted by John Barry (British, active 1784–1827) ca. 1790. The gift of Richard and Erna Flagg, it is part of the museum's permanent collection. Other examples come from the Haggerty Museum of Art at Marquette University, the Charles Allis Art Museum and other local collectors, but cannot be displayed here under the terms of the loans. Sorry, but that is standard operating procedure for borrowed works in an exhibition.

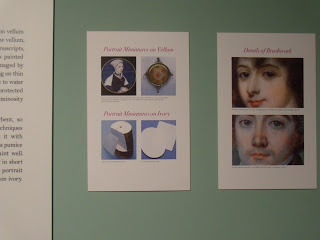

One of my favorites is this portrait, A Young Girl, with her hair unbound and blowing in the wind. It was painted by John Barry (British, active 1784–1827) ca. 1790. The gift of Richard and Erna Flagg, it is part of the museum's permanent collection. Other examples come from the Haggerty Museum of Art at Marquette University, the Charles Allis Art Museum and other local collectors, but cannot be displayed here under the terms of the loans. Sorry, but that is standard operating procedure for borrowed works in an exhibition. Text panels explain how the works were created, usually painted on thin slices of ivory as illustrated on the left. Because of the nature of the surface, the painting was done with tiny brushstrokes or dots, which can be seen in the gallery in the enlarged photos, right of the slice.

Text panels explain how the works were created, usually painted on thin slices of ivory as illustrated on the left. Because of the nature of the surface, the painting was done with tiny brushstrokes or dots, which can be seen in the gallery in the enlarged photos, right of the slice.  Other text panels show uses of the miniatures for jewelry or bibelots. To the right, Queen Elizabeth II wears two portrait miniatures of her predecessors on her shoulder.

Other text panels show uses of the miniatures for jewelry or bibelots. To the right, Queen Elizabeth II wears two portrait miniatures of her predecessors on her shoulder.  This tiny picture was taken from a painting by Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-92) of Lady Smith and her Children, miniaturized and handsomely framed. Though is it a bit too large to be worn, it could easily have been carried on travels.

This tiny picture was taken from a painting by Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-92) of Lady Smith and her Children, miniaturized and handsomely framed. Though is it a bit too large to be worn, it could easily have been carried on travels.

This lovely example is by celebrated miniaturist George Engleheart (1750-1829), Woman in a Hat, c. 1790. It is a recent addition to the museum's collections. Engleheart was a miniature painter to George III and finished at least 25 portraits of the king himself as well as many others.

Here is the MAM's official photo of the miniature.

Here is the MAM's official photo of the miniature. George Engleheart, Woman in a Hat, ca. 1790. Gift of Edith Maclay in memory of Frederick H. von Schleinitz.

Photo by John R. Glembin

One of the special events planned during the exhibition was a discussion of Jane Austen's Persuasion led by Museum Educator Amy Kirschke, at the right of the picture. Amy leads a monthly book salon at the museum with each book choice related to a current MAM exhibition. She looked to Jane Austen and her oft-quoted statement about her work being like a fine brush on a tiny piece of ivory.

In case you had forgotten (as I had), in Persuasion, Captain Harville has brought to Bath a miniature of Captain Benwick to have it reset as a gift from Benwick to his new fiancee Louisa Musgrove, though it had originally been painted for his late love, Fanny Harville. This sparks a discussion between Capt. Harville and Anne about the nature of love and fidelity, overheard by Captain Wentworth. Anne's expressions further motivate him to propose again to her. How clever of Ms. Kirschke to find such a perfect example of a miniature in literature.

In case you had forgotten (as I had), in Persuasion, Captain Harville has brought to Bath a miniature of Captain Benwick to have it reset as a gift from Benwick to his new fiancee Louisa Musgrove, though it had originally been painted for his late love, Fanny Harville. This sparks a discussion between Capt. Harville and Anne about the nature of love and fidelity, overheard by Captain Wentworth. Anne's expressions further motivate him to propose again to her. How clever of Ms. Kirschke to find such a perfect example of a miniature in literature. I was reminded of my recent visit to the Wallace Collection in London where I saw the famous portrait of Perdita, Mrs. Robinson, in which she holds a miniature of the Prince of Wales, her former lover.

I was reminded of my recent visit to the Wallace Collection in London where I saw the famous portrait of Perdita, Mrs. Robinson, in which she holds a miniature of the Prince of Wales, her former lover.Miniatures are ever so fascinating and this exhibition with its wide selection of examples is well worth seeing.

Published on October 07, 2010 02:00

October 6, 2010

A Legacy of Needlework - Part Two - Mrs. Delaney Continued

Tiffany and Company were inspired to create a china pattern called "Mrs. Delany's Flowers."

A few years ago I had the opportunity to visit an exhibition called "Mrs. Delany and Her Circle," at the Yale Center for British Art. The show, organized by the Center for British Art and Sir John Soane's Museum in London, included work in every conceivable medium.

One of the items included in the exhibition was the needlework Mrs. Delany executed on a black ground for the court dress mentioned in a previous post and shown here.

The piece of fabric was placed between two panes of glass, allowing visitors to examine it closely. I have been doing crewel, embroidery and needlepoint for decades and must say that I've never seen anything so astonishing. Mrs. Delany's stitches were neat and well placed, but that was only the beginning. The reverse of the fabric had been as neatly wrought as the front, with nary a knot in sight. The threads were as vibrantly coloured today as they must have been two hundred years ago, showing the detail of the design and the subtlety of color variations throughout the work. It is astonishing to realize that the designs for Mrs. Delany's work originated in her own mind. Perhaps she worked her pieces directly from that picture in her mind's eye. However, she was also able to translate those designs onto other pieces of fabrics and to write instructions and colour directions down, thus making needlework "kits" for her friends and family to execute.

In 1861, Augusta Hall (Baroness Llanover) edited a volume called The Autobiography and Correspondence of Mary Granville, Mrs. Delany. In the appendix, the editor wrote:

"Were it possible to give a list of the work designed and executed by Mrs. Delany with the needle, independent of the quantity of various works in various ways designed by her for her friends to execute, it would be a much more extraordinary exemplification of what may be achieved by human industry and ingenuity, aided by natural talent, than the catalogue of her paintings. The Editor is not able to give an account of more than the specimens of Mrs. Delany's needlework which are in her own possession, and that of her sister, and a few other relations. Of these are a number of chairs, the backs and seats of which are embroidered in a manner entirely different to anything that has ever (in the knowledge of the Editor) been done for a similar purpose. They consist of magnificent groups of flowers from nature, some on light and some on dark grounds, all different from each other, and all executed in worsted chenille, (made upon linen thread;) possessing the finest semi-tones of colour, which produce a variety of tint and harmony, as well as depth of colour, which never appear in the modern dyes of wool of any description. Some of these chairs are worked in embroidery stitch upon canvas, by which means the utmost freedom of outline was possible, and the most exact imitation of nature. In other sets of chairs cloth was used as the ground upon which the outline of the flowers must have been sketched, and the shades and colours filled in by sewing down the worsted chenilles by the eye, and cutting them off where required. These specimens prove Mrs. Delany's marvellous talent for design, as well as ability in execution, and are suitable for furniture which though ornamental was yet useful; but there also exist bed hangings, and chair and sofa covers, which combine in as remarkable a manner striking effect with every day utility. Some of these were the covers of her drawing-room chairs in London, where the ground was brilliant dark blue linen, bordered with leaves cut out by herself in white linen, and edged and veined with white knotting of different sorts and thickness, sewed down along the edge. A bed completed by herself, and her sister Ann Granville, was of nankeen, with designs executed in white linen, for the headboard and hangings, all different, but well adapted to the various parts, and of a washing material, the durability of which as well as the excellence of the work is best proved by its endurance for near a hundred years in continual use! Mrs. Delany did not employ silk for her furniture, but woollen or linen materials; and the worsted chenilles, made on linen thread, never were attacked by the moths: there is now a box of them in the Editor's possession left from Mrs. Delany's work, which are still fit for use; it ought also to be mentioned that all these chenilles were wound on two cards folded together by herself in a peculiar manner, which prevented the chenilles being cut by the edges of the cards."

Mrs. Delany died April 10th, 1788, and was interred in a vault belonging to St. James' church, where a monument has been erected to her memory.

For further reading on Mrs. Delany read Mrs. Delany: Her Life and Her Flowers by Ruth Hayden (ISBN: 071418022X / 0-7141-8022-X ); Mrs. Delany (Mary Granville): A Memoir, 1700-1788 by George Paston (ISBN: 1150362642 ) and The Autobiography and Correspondence of Mary Granville, Mrs. Delany by Augusta Hall (Baroness Llanover).

Published on October 06, 2010 02:24

October 5, 2010

We've Won the Vetcy Award!

Huzza! Previously, Number One London had won the Vetcy Award for Blog Excellence in the Historical Category. This blog, along with three others in various categories, then vied for the place of overall blog winner and we are now pleased to announce that we've won the Grand Prize.

Huzza! Previously, Number One London had won the Vetcy Award for Blog Excellence in the Historical Category. This blog, along with three others in various categories, then vied for the place of overall blog winner and we are now pleased to announce that we've won the Grand Prize. Of course, none of this would have happened without your support and votes over the past month and we once again offer a hearty `thank you' to Patty Suchy, who brought us to the attention of the Vetcy Award judges.

Published on October 05, 2010 01:57

October 4, 2010

Upstairs, Downstairs - The Remake

PBS and BBC will be offering what PBS is calling a "new production" of "Upstairs Downstairs" for debut in 2011 as part of the 40th anniversary season of "Masterpiece Theatre." Winning seven Emmys, the 1970's series was a landmark event that defined excellence in dramatic story telling on television. Dame Eileen Atkins (at right in a scene from Cranford), one of the creators of the orginal version, will star this time around, along with Jean Marsh, who will be reprising her role as Rose, the parlor maid/now housekeeper, in the new series. Marsh won an Emmy as best actress for her work in the original version. The new series will again be set in the house at 165 Eaton Place, this time in 1936 on the eve of World War II and will follow a different family, the Hollands, now living in the house. The house has been inherited by the wealthy Sir Hallam Holland, a young and well-connected diplomat, following the unexpected death of his Baronet father.

PBS and BBC will be offering what PBS is calling a "new production" of "Upstairs Downstairs" for debut in 2011 as part of the 40th anniversary season of "Masterpiece Theatre." Winning seven Emmys, the 1970's series was a landmark event that defined excellence in dramatic story telling on television. Dame Eileen Atkins (at right in a scene from Cranford), one of the creators of the orginal version, will star this time around, along with Jean Marsh, who will be reprising her role as Rose, the parlor maid/now housekeeper, in the new series. Marsh won an Emmy as best actress for her work in the original version. The new series will again be set in the house at 165 Eaton Place, this time in 1936 on the eve of World War II and will follow a different family, the Hollands, now living in the house. The house has been inherited by the wealthy Sir Hallam Holland, a young and well-connected diplomat, following the unexpected death of his Baronet father.Holland is played by 35-year-old Ed Stoppard, the son of playwright Sir Tom, and takes up residence with his wife and his imposing mother Lady Maud, a free-thinking intellectual played by Dame Eileen who keeps a pet monkey called Solomon.

The series will see two new 90 minute scripts penned by writer Heidi Thomas (Cranford, Madame Bovary, Ballet Shoes). Actress Keeley Hawes will play Lady Agnes Holland and you can follow her blog here. Actress Claire Foy will appear as her temptress sister, Lady Persie.

Art Malik, Anne Reid, Ed Stoppard, Adrian Scarborough, Ellie Kendrick and Nico Mirallegro are also part of the cast. BBC is planning to screen the drama as early as autumn and it will be broadcast on Masterpiece in the US shortly after it makes its British debut. They hope to find similar success to the original, which was broadcast in more than 70 countries to an audience of more than a billion.

Writer Heidi Thomas, who also scripted the successful BBC's drama Cranford, said: 'The series will be shot through with sensuality. This is a drama very much about warm-blooded human beings. In a house like Eaton Place, there is a limit to what you can keep behind closed doors. The place is a pressure cooker and the tensions continue to rise and rise until they boil over. Whether the characters are upstairs or downstairs they are living in close proximity to each other and these are the dramas that will engage viewers.'

Oh, joy!

By the way, the setting for Upstairs, Downstairs, 165 Eaton Place, is in actuality the house standing at 65 Eaton Place (above). For the new series, a full-scale replica of Eaton Place has been built at studios in Cardiff, where filming began in August.

Published on October 04, 2010 02:37

October 2, 2010

The Death of Miss Cholomdeley

The town of Leatherhead, two miles south of Ashsted, was an ancient market town in Surrey, the market having long been discontinued by the early nineteenth century. The town still held a fair on Lady's Day, three weeks before Michaelmas, during the Regency period, "but otherwise the town possessed no trade or privilege than what its being a great thoroughfare produces." The only "remarkables" were the fourteenth-century church and the bridge, which was a very neat structure over the River Mole, built of brick and consisting of fourteen arches.

The town of Leatherhead, two miles south of Ashsted, was an ancient market town in Surrey, the market having long been discontinued by the early nineteenth century. The town still held a fair on Lady's Day, three weeks before Michaelmas, during the Regency period, "but otherwise the town possessed no trade or privilege than what its being a great thoroughfare produces." The only "remarkables" were the fourteenth-century church and the bridge, which was a very neat structure over the River Mole, built of brick and consisting of fourteen arches. At this quite and idyllic a spot, however, there occurred a Regency tragedy in 1806 – a coaching accident involving the Princess of Wales. Dr. Hughson described the incident thusly in his Description of London:

"A most dreadful accident occurred in this town in the year 1806. Her royal highness the Princess of Wales, on the afternoon of October 2, was on her way in a barouche, attended by Lady Sheffield and Miss Harriet Mary Cholmondeley, to pay a visit to Mrs. Lock, at Norbury Park (right), and was driven by the princess's own servants as far as Sutton. At this place post-horses were put to the carriage, driven by the post-boys belonging to the Cock Inn; her highnesses horses remained at Sutton till she returned. On her arrival at Leatherhead, the carriage, which was drawn by four horses, whilst turning around an acute angle of the road, was overturned. It appears that the drivers, through extreme caution, had taken too great a sweep in turning the corner, which brought the barouche on a rising ground, by which it was overset; but before its fall it swung about a great tree.

"A most dreadful accident occurred in this town in the year 1806. Her royal highness the Princess of Wales, on the afternoon of October 2, was on her way in a barouche, attended by Lady Sheffield and Miss Harriet Mary Cholmondeley, to pay a visit to Mrs. Lock, at Norbury Park (right), and was driven by the princess's own servants as far as Sutton. At this place post-horses were put to the carriage, driven by the post-boys belonging to the Cock Inn; her highnesses horses remained at Sutton till she returned. On her arrival at Leatherhead, the carriage, which was drawn by four horses, whilst turning around an acute angle of the road, was overturned. It appears that the drivers, through extreme caution, had taken too great a sweep in turning the corner, which brought the barouche on a rising ground, by which it was overset; but before its fall it swung about a great tree. "The dreadful consequence was, that Miss Cholmondeley was killed on the spot; providentially the princess received no other injury, except a cut on her nose, and a bruise on her arm. Lady Sheffield did not receive the slightest hurt, besides that which overwhelmed the royal party, by the shocking accident. Her royal highness returned to Blackheath the next day."

The Annual Register expands on the incident:

It is with great concern we have to state the following melancholy accident. Her royal highness the Princess of Wales was this afternoon on her way to the seat of Mr. Locke, at Norbury Park, near Leatherhead, Surrey, in a barouche, attended by Lady Sheffield and Miss Harriet Mary Cholmondeley, and was driven by her royal highness's own servants. They took post horses, and were driven by the post-boys belonging to the Cock Inn. Her royal highnesses horses and servants were left to refresh in order to take her home that evening. Her royal highness proceeded to Leatherhead, when on turning a sharp corner to get into the road which leads to Norbury Park, the carriage was overturned, opposite to a large tree, against which Miss Cholmondeley was thrown with such violence, as to be killed on the spot. She was sitting on the front seat of the barouche alone. Her royal highness and Lady Sheffield occupied the back seat, and were thrown out together. They went into the Swan Inn, at Leatherhead. Sir Lucas Pepys, who lives in that neighbourhood, and had not left Leatherhead (where he had been to visit a patient) more than a quarter of an hour, was immediately followed, and brought back; and a servant was sent to Mr. Locke's, with an account of the accident. Mrs. L. arrived in her carriage with all expedition, and conducted the princess to Norbury Park, where Sir Lucas Pepys attended her royal highness and, as no surgeon was at hand, bled her himself. On the following day the princess returned to Blackheath. Her royal highness received no other injury than a slight cut on her nose, and a bruise on one of her arms. Lady Sheffield (wife of Lord Sheffield, who was with her, did not receive the slightest injury. — An inquest was held on the 4th, before C. Jemmet, esq. coroner for Surrey, on the body of Miss Cholmondeley, at the Swan Inn, Leatherhead. It appeared, by the evidence of a Mr. Jarrat at Leatherhead, and of an hostler belonging to the inn, that the princess's carriage, drawn by four horses, with two postillions, while turning round a very acute angle of the road, was overturned. The drivers, through extreme caution, had taken too great a sweep in turning) the corner, which brought the carriage on the rising ground, and occasioned its being upset. The carriage swung round a great tree before it fell. When the surgeon saw the Princess of Wales, she most benevolently desired him to go up stairs, as there was a lady who stood more in need of his assistance. The surgeon (Mr. Lawden, of Great Bookham) then went to Miss Cholmondeley, and found her totally deprived of life. There was a violent contusion on her left temple; and her death appeared to have been occasioned by the rupture of a blood vessel. The jury returned a verdict of Accidental Death. Miss Cholmondeley was born in 1753, and was the daughter of the late lion, and Rev. Robert Cholmondeluy, rector of Hartingford-Bury, and St. Andrews, Hertford, who was son of the third earl of Cholmondeley, and uncle to the present earl. Her mother is living, and resides in Jermyn-street. On the 8th, at 12 o'clock, the remains of this unfortunate lady were interred in Leatherhead church, close to the spot where lady Thompson, wife of sir John Thompson, some years since lord mayor of London, is buried. The body was, on the evening of the sixth, removed from the Swan Inn to an undertaker's near the church-yard, and was followed to the grave by her brother, George Cholmondcley, esq. one of the Commissioners of excise; the hon. Augustus Phipps ; William Locke, esq ; S. Gray, esq. and several other gentlemen. The fatal spot where this amiable lady met her sudden death is still visited by crowds.

It may be noted that the Locke's were also close friends of famed diarist and novelist Frances Burney, Mme d'Arblay who mentions the family often in her journal, as seen by the entries here for 1784. At this period the health of Mrs. Phillips (Fanny's sister Susan) failed so much that, after some deliberation, she and Captain Phillips decided on removing to Boulogne for change of air. The anxiety evidenced in the letter below was due to Burney's waiting to here of her sister's safe arrival in France.

It may be noted that the Locke's were also close friends of famed diarist and novelist Frances Burney, Mme d'Arblay who mentions the family often in her journal, as seen by the entries here for 1784. At this period the health of Mrs. Phillips (Fanny's sister Susan) failed so much that, after some deliberation, she and Captain Phillips decided on removing to Boulogne for change of air. The anxiety evidenced in the letter below was due to Burney's waiting to here of her sister's safe arrival in France.Friday, Oct. 8th.—I set off with my dear father for Chesington, where we passed five days very comfortably; my father was all good humour, all himself,— such as you and I mean by that word. The next day we had the blessing of your Dover letter, and on Thursday, Oct. 14, I arrived at dear Norbury Park at about seven o'clock, after a pleasant ride in the dark. Mr. Lock most kindly and cordially welcomed me; he came out upon the steps to receive me, and his beloved Fredy waited for me in the vestibule. Oh, with what tenderness did she take me to her bosom! I felt melted with her kindness, but I could not express a joy like hers, for my heart was very full—full of my dearest Susan, whose image seemed before me upon the spot where we had so lately been together. They told me that Madame de la Fite, her daughter, and Mr. Hinde, were in the house; but as I am now, I hope, come for a long time, I did not vex at hearing this. Their first inquiries were if I had not heard from Boulogne.

Saturday.—I fully expected a letter, but none came; but Sunday I depended upon one. The post, however, did not arrive before we went to church. Madame de la Fite, seeing my sorrowful looks, good naturedly asked Mrs. Lock what could be set about to divert a little la pauvre Mademoiselle Burney ? and proposed reading a drama of Madame de Genlis. I approved it much, preferring it greatly to conversation; and, accordingly, she and her daughter, each taking characters to themselves, read "La Rosiere de Salency." It is a very interesting and touchingly simple little drama. . . . Next morning I went up stairs as usual, to treat myself with a solo of impatience for the post, and at about twelve o'clock I heard Mrs. Locke stepping along the passage. I was sure of good news, for I knew, if there was bad, poor Mr. Locke would have brought it. She came in, with three letters in her hand, and three thousand dimples in her cheeks and chin! Oh, my dear Susy, what a sight to me was your hand! I hardly cared for the letter; I hardly desired to open it; the direction alone almost satisfied me sufficiently. How did Mrs. Locke embrace me! I half kissed her to death. Then came dear Mr. Locke, his eyes brighter than ever— "Well, how does she do?"

This question forced me to open my letter; all was just as I could wish, except that I regretted the having written the day before such a lamentation. I was so congratulated! I shook hands with Mr. Locke; the two dear little girls came jumping to wish me joy; and Mrs. Locke ordered a fiddler, that they might have a dance in the evening, which had been promised them from the time of Mademoiselle de la Fite's arrival, but postponed from day to day, by general desire, on account of my uneasiness.

Published on October 02, 2010 03:30

Death of Miss Cholomdeley

The town of Leatherhead, two miles south of Ashsted, was an ancient market town in Surrey, the market having long been discontinued by the early nineteenth century. The town still held a fair on Lady's Day, three weeks before Michaelmas, during the Regency period, "but otherwise the town possessed no trade or privilege than what its being a great thoroughfare produces." The only "remarkables" were the fourteenth-century church and the bridge, which was a very neat structure over the River Mole, built of brick and consisting of fourteen arches.

The town of Leatherhead, two miles south of Ashsted, was an ancient market town in Surrey, the market having long been discontinued by the early nineteenth century. The town still held a fair on Lady's Day, three weeks before Michaelmas, during the Regency period, "but otherwise the town possessed no trade or privilege than what its being a great thoroughfare produces." The only "remarkables" were the fourteenth-century church and the bridge, which was a very neat structure over the River Mole, built of brick and consisting of fourteen arches. At this quite and idyllic a spot, however, there occurred a Regency tragedy in 1806 – a coaching accident involving the Princess of Wales. Dr. Hughson described the incident thusly in his Description of London:

"A most dreadful accident occurred in this town in the year 1806. Her royal highness the Princess of Wales, on the afternoon of October 2, was on her way in a barouche, attended by Lady Sheffield and Miss Harriet Mary Cholmondeley, to pay a visit to Mrs. Lock, at Norbury Park (right), and was driven by the princess's own servants as far as Sutton. At this place post-horses were put to the carriage, driven by the post-boys belonging to the Cock Inn; her highnesses horses remained at Sutton till she returned. On her arrival at Leatherhead, the carriage, which was drawn by four horses, whilst turning around an acute angle of the road, was overturned. It appears that the drivers, through extreme caution, had taken too great a sweep in turning the corner, which brought the barouche on a rising ground, by which it was overset; but before its fall it swung about a great tree.

"A most dreadful accident occurred in this town in the year 1806. Her royal highness the Princess of Wales, on the afternoon of October 2, was on her way in a barouche, attended by Lady Sheffield and Miss Harriet Mary Cholmondeley, to pay a visit to Mrs. Lock, at Norbury Park (right), and was driven by the princess's own servants as far as Sutton. At this place post-horses were put to the carriage, driven by the post-boys belonging to the Cock Inn; her highnesses horses remained at Sutton till she returned. On her arrival at Leatherhead, the carriage, which was drawn by four horses, whilst turning around an acute angle of the road, was overturned. It appears that the drivers, through extreme caution, had taken too great a sweep in turning the corner, which brought the barouche on a rising ground, by which it was overset; but before its fall it swung about a great tree. "The dreadful consequence was, that Miss Cholmondeley was killed on the spot; providentially the princess received no other injury, except a cut on her nose, and a bruise on her arm. Lady Sheffield did not receive the slightest hurt, besides that which overwhelmed the royal party, by the shocking accident. Her royal highness returned to Blackheath the next day."

The Annual Register expands on the incident:

It is with great concern we have to state the following melancholy accident. Her royal highness the Princess of Wales was this afternoon on her way to the seat of Mr. Locke, at Norbury Park, near Leatherhead, Surrey, in a barouche, attended by Lady Sheffield and Miss Harriet Mary Cholmondeley, and was driven by her royal highness's own servants. They took post horses, and were driven by the post-boys belonging to the Cock Inn. Her royal highnesses horses and servants were left to refresh in order to take her home that evening. Her royal highness proceeded to Leatherhead, when on turning a sharp corner to get into the road which leads to Norbury Park, the carriage was overturned, opposite to a large tree, against which Miss Cholmondeley was thrown with such violence, as to be killed on the spot. She was sitting on the front seat of the barouche alone. Her royal highness and Lady Sheffield occupied the back seat, and were thrown out together. They went into the Swan Inn, at Leatherhead. Sir Lucas Pepys, who lives in that neighbourhood, and had not left Leatherhead (where he had been to visit a patient) more than a quarter of an hour, was immediately followed, and brought back; and a servant was sent to Mr. Locke's, with an account of the accident. Mrs. L. arrived in her carriage with all expedition, and conducted the princess to Norbury Park, where Sir Lucas Pepys attended her royal highness and, as no surgeon was at hand, bled her himself. On the following day the princess returned to Blackheath. Her royal highness received no other injury than a slight cut on her nose, and a bruise on one of her arms. Lady Sheffield (wife of Lord Sheffield, who was with her, did not receive the slightest injury. — An inquest was held on the 4th, before C. Jemmet, esq. coroner for Surrey, on the body of Miss Cholmondeley, at the Swan Inn, Leatherhead. It appeared, by the evidence of a Mr. Jarrat at Leatherhead, and of an hostler belonging to the inn, that the princess's carriage, drawn by four horses, with two postillions, while turning round a very acute angle of the road, was overturned. The drivers, through extreme caution, had taken too great a sweep in turning) the corner, which brought the carriage on the rising ground, and occasioned its being upset. The carriage swung round a great tree before it fell. When the surgeon saw the Princess of Wales, she most benevolently desired him to go up stairs, as there was a lady who stood more in need of his assistance. The surgeon (Mr. Lawden, of Great Bookham) then went to Miss Cholmondeley, and found her totally deprived of life. There was a violent contusion on her left temple; and her death appeared to have been occasioned by the rupture of a blood vessel. The jury returned a verdict of Accidental Death. Miss Cholmondeley was born in 1753, and was the daughter of the late lion, and Rev. Robert Cholmondeluy, rector of Hartingford-Bury, and St. Andrews, Hertford, who was son of the third earl of Cholmondeley, and uncle to the present earl. Her mother is living, and resides in Jermyn-street. On the 8th, at 12 o'clock, the remains of this unfortunate lady were interred in Leatherhead church, close to the spot where lady Thompson, wife of sir John Thompson, some years since lord mayor of London, is buried. The body was, on the evening of the sixth, removed from the Swan Inn to an undertaker's near the church-yard, and was followed to the grave by her brother, George Cholmondcley, esq. one of the Commissioners of excise; the hon. Augustus Phipps ; William Locke, esq ; S. Gray, esq. and several other gentlemen. The fatal spot where this amiable lady met her sudden death is still visited by crowds.

It may be noted that the Locke's were also close friends of famed diarist and novelist Frances Burney, Mme d'Arblay who mentions the family often in her journal, as seen by the entries here for 1784. At this period the health of Mrs. Phillips (Fanny's sister Susan) failed so much that, after some deliberation, she and Captain Phillips decided on removing to Boulogne for change of air. The anxiety evidenced in the letter below was due to Burney's waiting to here of her sister's safe arrival in France.

It may be noted that the Locke's were also close friends of famed diarist and novelist Frances Burney, Mme d'Arblay who mentions the family often in her journal, as seen by the entries here for 1784. At this period the health of Mrs. Phillips (Fanny's sister Susan) failed so much that, after some deliberation, she and Captain Phillips decided on removing to Boulogne for change of air. The anxiety evidenced in the letter below was due to Burney's waiting to here of her sister's safe arrival in France.Friday, Oct. 8th.—I set off with my dear father for Chesington, where we passed five days very comfortably; my father was all good humour, all himself,— such as you and I mean by that word. The next day we had the blessing of your Dover letter, and on Thursday, Oct. 14, I arrived at dear Norbury Park at about seven o'clock, after a pleasant ride in the dark. Mr. Lock most kindly and cordially welcomed me; he came out upon the steps to receive me, and his beloved Fredy waited for me in the vestibule. Oh, with what tenderness did she take me to her bosom! I felt melted with her kindness, but I could not express a joy like hers, for my heart was very full—full of my dearest Susan, whose image seemed before me upon the spot where we had so lately been together. They told me that Madame de la Fite, her daughter, and Mr. Hinde, were in the house; but as I am now, I hope, come for a long time, I did not vex at hearing this. Their first inquiries were if I had not heard from Boulogne.

Saturday.—I fully expected a letter, but none came; but Sunday I depended upon one. The post, however, did not arrive before we went to church. Madame de la Fite, seeing my sorrowful looks, good naturedly asked Mrs. Lock what could be set about to divert a little la pauvre Mademoiselle Burney ? and proposed reading a drama of Madame de Genlis. I approved it much, preferring it greatly to conversation; and, accordingly, she and her daughter, each taking characters to themselves, read "La Rosiere de Salency." It is a very interesting and touchingly simple little drama. . . . Next morning I went up stairs as usual, to treat myself with a solo of impatience for the post, and at about twelve o'clock I heard Mrs. Locke stepping along the passage. I was sure of good news, for I knew, if there was bad, poor Mr. Locke would have brought it. She came in, with three letters in her hand, and three thousand dimples in her cheeks and chin! Oh, my dear Susy, what a sight to me was your hand! I hardly cared for the letter; I hardly desired to open it; the direction alone almost satisfied me sufficiently. How did Mrs. Locke embrace me! I half kissed her to death. Then came dear Mr. Locke, his eyes brighter than ever— "Well, how does she do?"

This question forced me to open my letter; all was just as I could wish, except that I regretted the having written the day before such a lamentation. I was so congratulated! I shook hands with Mr. Locke; the two dear little girls came jumping to wish me joy; and Mrs. Locke ordered a fiddler, that they might have a dance in the evening, which had been promised them from the time of Mademoiselle de la Fite's arrival, but postponed from day to day, by general desire, on account of my uneasiness.

Published on October 02, 2010 03:30

October 1, 2010

The Room by Emma Donoghue

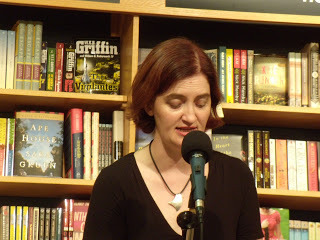

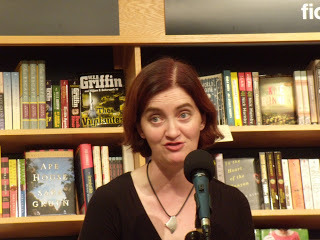

Victoria here, lucky enough to have attended a recent reading and signing by Emma Donoghue at the Next Chapter Book Store in the Milwaukee suburb of Mequon. She read from her latest novel The Room, which has been short-listed for the Man Booker Prize, Britain's most prestigious literary award.

Victoria here, lucky enough to have attended a recent reading and signing by Emma Donoghue at the Next Chapter Book Store in the Milwaukee suburb of Mequon. She read from her latest novel The Room, which has been short-listed for the Man Booker Prize, Britain's most prestigious literary award. She read from the first chapter of the book, in the unusual point of view of the five-year-old boy who has lived in the room alone except for his mother. I was almost unable to put the book down once I started reading it. I found it entirely gripping and extremely well written.

She read from the first chapter of the book, in the unusual point of view of the five-year-old boy who has lived in the room alone except for his mother. I was almost unable to put the book down once I started reading it. I found it entirely gripping and extremely well written. You can find more about Ms. Donoghue and her novel here. It was recently reviewed on the front page of the New York Times Book Review Sunday, September 19, read it here. Although you will be unable to avoid some description of the story, try not to find out anything about it beyond the basic premise. No spoilers, please!

You can find more about Ms. Donoghue and her novel here. It was recently reviewed on the front page of the New York Times Book Review Sunday, September 19, read it here. Although you will be unable to avoid some description of the story, try not to find out anything about it beyond the basic premise. No spoilers, please! Following her reading, Ms. Donoghue answered many questions about the novel, it's voice, it's inspiration, and her newly found prominence. In all humility, she said, while talking of her attempts to work on her next novel, "Being famous is very exhausting." She spoke about her children, a son and a daughter, and how her relationships with them fed into the novel. She was born in Ireland and now lives in Canada.

Following her reading, Ms. Donoghue answered many questions about the novel, it's voice, it's inspiration, and her newly found prominence. In all humility, she said, while talking of her attempts to work on her next novel, "Being famous is very exhausting." She spoke about her children, a son and a daughter, and how her relationships with them fed into the novel. She was born in Ireland and now lives in Canada.

I first read Donoghue's 2004 novel Life Mask, set in London in the 1790's. Major characters include Elizabeth Farren, an actress; the Earl of Derby, her devoted admirer; and Anne Damer, a sculptress and society widow. It was well-researched and I found it fascinating that she has not returned to this period to investigate further interesting characters of the time. But she disclosed her next project will be set in mid-19th century California. Wow!

Best of luck to you, Emma Donoghue. May you follow in the footsteps of Hilary Mantel (see my post of 9/5/10) and win the Man Booker!

Published on October 01, 2010 01:42

September 30, 2010

A Legacy of Needlework - Mrs. Delany

Mary Granville, or Mrs. Delany, is remembered for her letters and for her elaborate paper flower work and her magnificent needlework. What's most remarkable about Mrs. Delany is the fact that she only hit her artistic stride after reaching the age of 72! Twice widowed with no children, Mrs. Delany became a royal favorite and sought after by society, numbering Handel, Jonathan Swift, the Duchess of Portland, Fanny Burney and the king and queen of England among her closest friends, all while executing an astonishing body of work that includes the Flora Delanica - almost 1,000 botanical collages that took a decade to complete.

Mary Granville was married at seventeen to the Cornish squire, Alexander Pendarves of Roscrow, who was more than forty years older than she and described by a contemporary as being 'ugly, disagreeable and gouty'. After he died in 1724, Mary discovered that she'd been left annuity in the hundreds of pounds, far less than she'd anticipated, yet enough to allow her travel amongst relatives and forge ties and friendships that would serve her well in later life.

In the following years, Mary designed an unusual court dress of intricately detailed floral embroidery on black satin. Portions of the dress, preserved in frames by her heirs, reveal the sort of attention to detail that would later be the hallmark of her lifelike floral collages.

While in Dublin in 1740, Mary met Patrick Delany, a Anglican cleric, widower and close friend of Swift's who would become her second husband in 1743. The marriage was a true love match and Mary flourished under Mr. Delany's affection and his support of her talents. She had her own workroom at their home in Ireland, with a large bow window overlooking the gardens. Here, Mary made landscape drawings, silhouettes and "japanned" (lacquered) objects. A larger project was the garden grotto Mary designed and executed at Alexander Pope's estate.

Upon Mr. Delany's death in 1768, Mary took up residence with her friend and fellow widow the Duchess of Portland. It was the Duchess who introduced Mrs. Delany to Queen Charlotte, and she became a firm favourite at court, where her talents, intellect and 'social refinement' were much admired.

Mrs Delany's tools from needlework pocket-book, given by Queen Charlotte to Mrs Delany, 1781.

The Duchess of Portland died in 1785, and the King and Queen, concerned for the welfare of their old friend, offered Mrs. Delany an annuity and a small house at Windsor.

Queen Charlotte

On September 3rd, Queen Charlotte wrote: 'My dear Mrs. Delany will be glad to hear that I am charged by the king to summon her to her new abode at Windsor for Tuesday next, when she will find all the most essential parts of the house ready, excepting some little trifles that it will be better for Mrs. Delany to direct herself in person or by her little deputy, Miss Port. I need not, I hope, add that I shall be extremely glad and happy to see so amiable an inhabitant in this our sweet retreat, and wish very sincerely that our dear Mrs. Delany may enjoy every blessing among us that her merits deserve, and that we may long enjoy her amiable company. Amen. These are the true sentiments of my dear Mrs. Delany's very affectionate queen, Charlotte.'

Mrs. Delany wrote the following account of her arrival at Windsor to her friend Mrs. Hamilton : 'I arrived here about eight o'clock in the evening and found his Majesty in the house ready to receive me. I threw myself at his feet, indeed unable to utter a word; he raised and saluted me, and said he meant not to stay longer than to desire I would order everything that could make the house comfortable and agreeable to me, and then retired. Truly, I found nothing wanting, as it is as pleasant and commodious as I could wish it to be, with a very pretty garden, which joins that of the Queen's Lodge. The next morning her Majesty sent one of her ladies to know how I had rested, and how I was in health, and whether her coming would not be troublesome. I was lame, and therefore could not go down to the door as I ought to have done, but her Majesty came upstairs. Our meeting was mutually affecting; she well knew the value of what I had lost, and it was some time after we were seated before either of us could speak. She repeated in the strongest terms her wish and the king's, that I should be as easy and happy as they could possibly make me; that they waived all ceremony, and desired to come to me as friends! The queen also delivered me a paper from the king: it contained the first quarter of £300 per annum, which his majesty allows me out of his privy purse. Their majesties have drunk tea with me five times, and the princesses three. They generally stay two hours or longer. In short, I have either seen them or heard of them every day, but I have not yet been at the Queen's Lodge, though they have expressed impatience for me to come, as I have still so sad a drawback on my spirits that I must decline that honour till I am better able to enjoy it, and they have the goodness not to press me. Their visits here are paid in the most quiet, private manner, like those of the most consoling, disinterested friends; so that I may truly say they are a royal cordial, and I see very few people besides. I have been three times in the king's private chapel at early prayers, where the royal family constantly attend, and they walk home to breakfast afterwards, whilst I am conveyed in a very elegant chair which the king has made me a present of for that purpose.'

While at Windsor, Mrs. Delany would befreind Fanny Burney and receive regular visits from Mrs. Garrick, the late actor's widow.

Perhaps it was the Duchess of Portland's friendship that had the most influence on the art Mrs. Delany would undertake later in life. Each year, Mrs. Delany made a visit of several months to Bulstrode, the duchess's estate in Buckinghamshire, where she had access to an extraordinary cabinet of curiosities that included rare and exotic plants and flowers. Also at Bulstrode were the botanist John Lightfoot, the botanical artist Georg Dionysius Ehret and other advocates of the revolutionary taxonomy developed by the Swedish scientist Carl Linnaeus. Mrs. Delany observed their dissections of flowers and taught herself the art of the "hortus siccus," or pressed-flower composition. These experiments would give her the knowledge and understanding of flowers that would breathe life into her collages.

Eventually, Mrs. Delany devised a means of cutting tiny pieces of paper to create her flower collages and she went on to create several volumes of these 'paper mosaic' plants and flowers. So amazing were their realistic qualities that King George III ordered the volumes to be preserved in the British Museum "as a standard work of art unparalleled for accuracy of drawing, form, and perspective, as well as colouring, truth of outline, and close resemblance to nature." Horace Walpole called her collages "precision and truth unparalleled," while author William Gilpin wrote, "These flowers have both the beauty of painting, and the exactness of botany."

Part Two coming soon!

Published on September 30, 2010 02:45

September 29, 2010

The Tale of Lady Hertford, Prinny, Audubon and Chinese Wallpaper

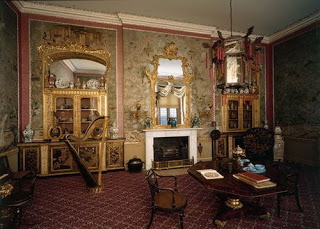

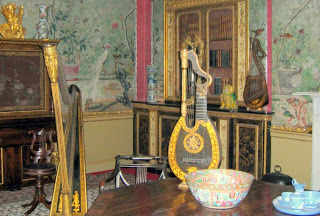

A current exhibit at Temple Newsam in Leeds entitled 'A House of Birds: American Birds in a Chinese Garden' is running to the end of November. The exhibit tells the amazing story of what happened when the former owner of Temple Newsam House, Isabella Ingram (known as Lady Hertford), decided to get creative with the décor in her sitting room in 1827. Once upon a time, Prinny (the future King George IV) was courting Isabella, and after a visit to the house in 1806 he gifted her mother, Frances, Lady Irwin, several rolls of blue, handpainted Chinese wallpaper.

This wallpaper was hand-painted in China for the export market. It dates from c.1800 and was intended to form a panoramic view of an Oriental garden. The garden is planted with flowering trees and shrubs in vases, and the viewer looks out over an alabaster balustrade.

These wallpapers were made in panels about four feet square and were shipped in this form to Europe. When an upholsterer like Thomas Chippendale was employed to redecorate a room, he expected the owner to supply the Chinese paper himself. In this case, Lady Irwin apparently had no liking, or use, for the paper, which mouldered away in a closet for the next twenty-one years.

Lady Hertford

Finally, Lady Hertford dug out the rolls of wallpaper in 1827 when she was redecorating the house and used them as the basis for the Blue Drawing Room (also known as the Chinese Drawing Room), creating the space in what had been the best dining room. By this time, however, the wallpaper had become a tad dated and its design was much more subdued than current fashion dictated. What's a Lady to do? Lady Herford eventually hit upon a unique decor scheme and used a bit of decoupage to add some zip to Prinny's wallpaper, embellishing the design with prints of exotic birds cut from John James Audubon's famous publication The Birds of America. Audubon visited England in order to get financial backing for the series and Lady Hertford had subscribed to the first issue. In a letter to his wife, Audubon tells her that Lady Hertford had cut out and used his prints to jazz up the wallpaper so that we know he was aware of the fact. Unfortunately, Audubon did not expand upon the mention, so we will never his views on the matter.

It should be noted that in 2000 an original copy of Audubon's The Birds of America sold for $8.8 million dollars, which is still a world record price for a book.

Temple Newsam house itself has a long history and was first mentioned in the Domesday Book. In 1155 it was given to the Knights Templar and Thomas Lord Darcy built a four-sided courtyard house on the site in the early sixteenth century. In 1537 the property was seized by the Crown following his execution for treason (he was involved in the Pilgrimage of Grace rising). Henry VIII gave the house to Margaret Countess of Lennox in 1544, and her son, Henry Lord Darnley, was born in the house the following year. In 1565 the estate was again seized by the Crown, this time by Elizabeth I, after Lord Darnley made the mistake of marrying Mary Queen of Scots.

The house fell into disrepair, and upon his accession in 1603, James I of England gave the estate to his cousin Ludovic Duke of Lennox, and it languished tenantless until Sir Arthur Ingram bought the estate in 1622 for £12,000; he rebuilt the house as the three-sided building which exists today, one wing of the old house being kept as the central wing of the new house. There was a financial crisis when the family lost a fortune in the South Sea Bubble, but that was sorted out by a son marrying an heiress; so more work could be done on the house, and Capability Brown landscaped the park.

Through the nineteenth century there were major works done on the interiors and the grounds, and in 1904 the estate was inherited by a nephew, Edward Wood, first Earl of Halifax; in 1922 he sold some of the parkland to Leeds Corporation for £35,000 and they eventually acquired the house for free.

Published on September 29, 2010 02:36

September 28, 2010

Do You Know About Monarch of the Glen?

No, not that Monarch of the Glen.

This Monarch of the Glen.

Monarch of the Glen was a BBC TV drama series featuring the exploits of an impecunious and somewhat dysfunctional Highland family in their efforts to keep the estate of Glenbogle going after Archie MacDonald, a young restaurateur, is called back to his childhood home where he must act as the new Laird.

Adapted from the so-called "Highland" novels of Compton MacKenzie, author of Sylvia Scarlett, the series originally starred Richard Briers, Susan Hampshire, Hamish Clark, Alastair Mackenzie, Dawn Steele and Sandy Morton. The programme ran for seven series, from 2000 to 2006, becoming the longest running non-soap drama ever run by the BBC, beating Ballykissangel by one year.

Adapted from the so-called "Highland" novels of Compton MacKenzie, author of Sylvia Scarlett, the series originally starred Richard Briers, Susan Hampshire, Hamish Clark, Alastair Mackenzie, Dawn Steele and Sandy Morton. The programme ran for seven series, from 2000 to 2006, becoming the longest running non-soap drama ever run by the BBC, beating Ballykissangel by one year.  In reality, Archie is not really the new Laird, as his eccentric father, Hector, is still alive, though increasingly unable, or unwilling, to fulfill the role. Archie's mother, Molly (Susan Hampshire, right) uses this as a crafty excuse to call her son home. In the first season, Archie resents his obligations as various problems arise at Glenbogle - not the least of which is that Hector's neglect of the estate has put it in dire financial straights. As the episodes progress, Archie finds himself increasingly attached to both the estate and it's inhabitants, including Lexie (Dawn Steele), the estate's sexy, street-smart cook; the shy and bumbling kilt-wearing handyman Duncan (Hamish Clark), and a quintessentially Scots gilly named Golly (Alexander Morton). Archie is constantly tasked with making the estate profitable, or at least marginally solvent, and schemes for raising money include turning the estate into a museum, a wedding hall, a hotel and a wildlife park. As the series goes on, we learn more about the lives of these characters, their connections to one another and their own reasons for wanting Glenbogle, and Archie, to succeed.

In reality, Archie is not really the new Laird, as his eccentric father, Hector, is still alive, though increasingly unable, or unwilling, to fulfill the role. Archie's mother, Molly (Susan Hampshire, right) uses this as a crafty excuse to call her son home. In the first season, Archie resents his obligations as various problems arise at Glenbogle - not the least of which is that Hector's neglect of the estate has put it in dire financial straights. As the episodes progress, Archie finds himself increasingly attached to both the estate and it's inhabitants, including Lexie (Dawn Steele), the estate's sexy, street-smart cook; the shy and bumbling kilt-wearing handyman Duncan (Hamish Clark), and a quintessentially Scots gilly named Golly (Alexander Morton). Archie is constantly tasked with making the estate profitable, or at least marginally solvent, and schemes for raising money include turning the estate into a museum, a wedding hall, a hotel and a wildlife park. As the series goes on, we learn more about the lives of these characters, their connections to one another and their own reasons for wanting Glenbogle, and Archie, to succeed.  Another of the stars of Monarch of the Glen is the atmospheric setting and gorgeous Highland scenery. The series was filmed around Badenoch and Strathspey - mainly in the Laggan, Newtonmore and Kingussie area, and the fairy-tale like Ardverikie House, on the far shore of Loch Laggan, became Glenbogle Castle. Ardverikie is itself a grand Scottish estate which, through time, has faced many of the problems that underpinned the stories of the dramatized in the series.

Another of the stars of Monarch of the Glen is the atmospheric setting and gorgeous Highland scenery. The series was filmed around Badenoch and Strathspey - mainly in the Laggan, Newtonmore and Kingussie area, and the fairy-tale like Ardverikie House, on the far shore of Loch Laggan, became Glenbogle Castle. Ardverikie is itself a grand Scottish estate which, through time, has faced many of the problems that underpinned the stories of the dramatized in the series.Ardverikie was built in 1878 by local craftsmen and has been owned by the same family since then. It has had a rich history, almost chosen by Queen Victoria instead of Balmoral as her Scottish retreat and ironically used briefly in the film `Mrs Brown' for some scenes. English painter John Millais spent many months here on the estate sketching and drawing. Landseer's influence is also evident within the house, as well as in the adoption of his most famous stag painting for the title of the television series.

You can watch a bit of Monarch of the Glen here, but the series is widely available through Blockbuster, Netflix and local libraries.

Published on September 28, 2010 02:11

Kristine Hughes's Blog

- Kristine Hughes's profile

- 6 followers

Kristine Hughes isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.