Kristine Hughes's Blog, page 101

November 1, 2013

The Magnificent Waterloo Chamber: The Wellington Tour

Victoria here, inviting you to join Kristine and me on The Wellington Tour, 4-14 September, 2014. For details on our planned itinerary, costs and other info, click here. Among the features of the tour is a visit to Windsor Castle and especially to its Waterloo Chamber.

Windsor Castle from the Thames The Waterloo Chamber was constructed within the Castle to commemorate the victory of the Allied Armies over the French in the Battle of Waterloo, June 18, 1815. Architect Sir Jeffry Wyattville (1766 – 1840) created the Chamber in 1824 out of several existing rooms. Parliament designated £300,000 for the project. Like most of King George IV's inspirations, it ran well over budget, eventually costing about £1,000,000. Wyattville also remodeled many other areas of Windsor Castle for George IV, William IV, and Queen Victoria; he was buried in the Castle's St. George's Chapel in 1840.

Windsor Castle from the Thames The Waterloo Chamber was constructed within the Castle to commemorate the victory of the Allied Armies over the French in the Battle of Waterloo, June 18, 1815. Architect Sir Jeffry Wyattville (1766 – 1840) created the Chamber in 1824 out of several existing rooms. Parliament designated £300,000 for the project. Like most of King George IV's inspirations, it ran well over budget, eventually costing about £1,000,000. Wyattville also remodeled many other areas of Windsor Castle for George IV, William IV, and Queen Victoria; he was buried in the Castle's St. George's Chapel in 1840.

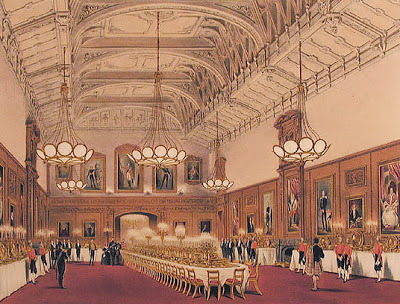

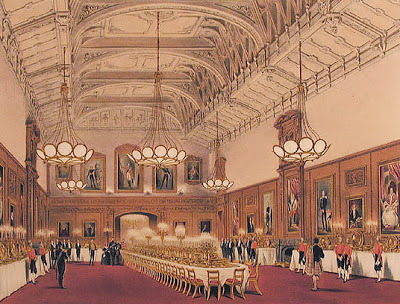

Watercolour of the Waterloo Chamber in 1844 by Joseph Nash

Watercolour of the Waterloo Chamber in 1844 by Joseph Nash

Waterloo Chamber, currently For a virtual tour of the entire Waterloo Chamber, click here.

Waterloo Chamber, currently For a virtual tour of the entire Waterloo Chamber, click here.

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of WellingtonCommander of the Victorious Allied Armies The walls of the Waterloo Chamber are filled with large portraits of the leaders of the Allied efforts. Most of them are painted by Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769-1830), the Regency era's favorite artist. Many were reproduced several times by his studio for numerous placements in other palaces, stately homes and distinguished galleries.

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of WellingtonCommander of the Victorious Allied Armies The walls of the Waterloo Chamber are filled with large portraits of the leaders of the Allied efforts. Most of them are painted by Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769-1830), the Regency era's favorite artist. Many were reproduced several times by his studio for numerous placements in other palaces, stately homes and distinguished galleries.

Prussian General Gebhardt von BlücherWellington's Comrade-in-arms at WaterlooSir Thomas Lawrence 1816 The Prince Regent (later George IV) commissioned Lawrence to paint all the Allied Sovereigns, military leaders, and statesmen. Lawrence traveled around Europe to complete the portraits.

Prussian General Gebhardt von BlücherWellington's Comrade-in-arms at WaterlooSir Thomas Lawrence 1816 The Prince Regent (later George IV) commissioned Lawrence to paint all the Allied Sovereigns, military leaders, and statesmen. Lawrence traveled around Europe to complete the portraits.

Austrian Field Marshal Karl Philipp, Prince of Schwartzenberg,

Austrian Field Marshal Karl Philipp, Prince of Schwartzenberg,

Alexander I, Emperor of Russia (1777-1825)painted by Sir Thomas Lawrence, 1818 According to the Royal Collection Website, "While working on the portrait Lawrence altered the position of the legs, much to the consternation of the Tzar and those courtiers attending the portrait sitting, especially when for a while the sitter was shown with four legs." Obviously, this condition was corrected!

Alexander I, Emperor of Russia (1777-1825)painted by Sir Thomas Lawrence, 1818 According to the Royal Collection Website, "While working on the portrait Lawrence altered the position of the legs, much to the consternation of the Tzar and those courtiers attending the portrait sitting, especially when for a while the sitter was shown with four legs." Obviously, this condition was corrected!

Pope Pius VII, 1819-20 The portrait of Pope Pius VII (1742-1823), painted in Rome, is widely agreed to be Lawrence's masterpiece, both incisive and sympathetic. While heads of state and leading generals were depicted full length, politicians and statesmen were honored with 3/4 length portraits, perhaps putting them in their place?

Pope Pius VII, 1819-20 The portrait of Pope Pius VII (1742-1823), painted in Rome, is widely agreed to be Lawrence's masterpiece, both incisive and sympathetic. While heads of state and leading generals were depicted full length, politicians and statesmen were honored with 3/4 length portraits, perhaps putting them in their place?

Viscount CastlereaghSir Thomas Lawrence, 1830 Robert Stewart (1769-1822), Viscount Castlereagh, later second Marquess of Londonderry, served as Secretary of State for War 1805-09, and Foreign Secretary 1812-1822

Viscount CastlereaghSir Thomas Lawrence, 1830 Robert Stewart (1769-1822), Viscount Castlereagh, later second Marquess of Londonderry, served as Secretary of State for War 1805-09, and Foreign Secretary 1812-1822

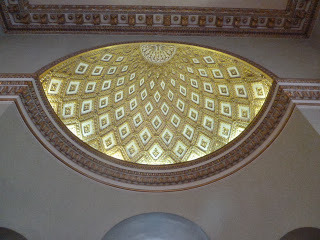

Robert Banks Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool Robert Banks Jenkinson (1770-1828), 2nd Earl of Liverpool was Prime Minister from 1812 to 1827, and also preceded the Duke of Wellington as the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports, about which more soon!! In the words of the Windsor Castle guidebook, "Most of the twenty eight portraits were delivered after his [Lawrence's] death on 7 January 1830. By this time work was already begun of the space of the Waterloo Chamber created by covering a courtyard at Windsor Castle with a huge sky-lit vault; the room was completed during the reign of William IV (1830-7)...the arrangement which survives to this day: full-length portraits of warriors hang high, over the two end balconies and around the walls; at ground level full-length portraits of monarchs alternate with half-lengths of diplomats and statesmen."

Robert Banks Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool Robert Banks Jenkinson (1770-1828), 2nd Earl of Liverpool was Prime Minister from 1812 to 1827, and also preceded the Duke of Wellington as the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports, about which more soon!! In the words of the Windsor Castle guidebook, "Most of the twenty eight portraits were delivered after his [Lawrence's] death on 7 January 1830. By this time work was already begun of the space of the Waterloo Chamber created by covering a courtyard at Windsor Castle with a huge sky-lit vault; the room was completed during the reign of William IV (1830-7)...the arrangement which survives to this day: full-length portraits of warriors hang high, over the two end balconies and around the walls; at ground level full-length portraits of monarchs alternate with half-lengths of diplomats and statesmen."

The limewood carvings on the walls were removed from the former Royal Chapel before it was demolished in the 1820s. The carvings date from the 1680's, the work of renowned artist Grinling Gibbons. According to the Castle Guidebook, "The Indian carpet was woven for this room by the inmates of Agra prison for Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee, finally reaching Windsor in 1894. Thought to be the largest seamless carpet in existence, it weighs two tonnes. During the 1992 fire it took 50 soldiers to roll it up and move it to safety." Which brings up a sorrowful subject, the terrible fire of eleven years ago.

The limewood carvings on the walls were removed from the former Royal Chapel before it was demolished in the 1820s. The carvings date from the 1680's, the work of renowned artist Grinling Gibbons. According to the Castle Guidebook, "The Indian carpet was woven for this room by the inmates of Agra prison for Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee, finally reaching Windsor in 1894. Thought to be the largest seamless carpet in existence, it weighs two tonnes. During the 1992 fire it took 50 soldiers to roll it up and move it to safety." Which brings up a sorrowful subject, the terrible fire of eleven years ago.

20 November, 1992 Extensive damage resulted from the fire though the Waterloo Chamber was only slightly damaged, due to the thickness of the walls. Other areas were destroyed and eventually repaired. To pay for the £36.5 million repairs, the Queen opened the State Rooms of Buckingham Palace to the Public, but only when she is in residence elsewhere. When you tour Windsor Castle with Kristine and me, you will see the renovated areas and where the fire burned. And we will view the Waterloo Chamber -- and all the State rooms, most of them still very much as they were when redone for George IV by Sir Jeffry Wyattville. Again to access more information on the Wellington Tour, go to http://wellingtontour.blogspot.com/

20 November, 1992 Extensive damage resulted from the fire though the Waterloo Chamber was only slightly damaged, due to the thickness of the walls. Other areas were destroyed and eventually repaired. To pay for the £36.5 million repairs, the Queen opened the State Rooms of Buckingham Palace to the Public, but only when she is in residence elsewhere. When you tour Windsor Castle with Kristine and me, you will see the renovated areas and where the fire burned. And we will view the Waterloo Chamber -- and all the State rooms, most of them still very much as they were when redone for George IV by Sir Jeffry Wyattville. Again to access more information on the Wellington Tour, go to http://wellingtontour.blogspot.com/

.

.

Windsor Castle from the Thames The Waterloo Chamber was constructed within the Castle to commemorate the victory of the Allied Armies over the French in the Battle of Waterloo, June 18, 1815. Architect Sir Jeffry Wyattville (1766 – 1840) created the Chamber in 1824 out of several existing rooms. Parliament designated £300,000 for the project. Like most of King George IV's inspirations, it ran well over budget, eventually costing about £1,000,000. Wyattville also remodeled many other areas of Windsor Castle for George IV, William IV, and Queen Victoria; he was buried in the Castle's St. George's Chapel in 1840.

Windsor Castle from the Thames The Waterloo Chamber was constructed within the Castle to commemorate the victory of the Allied Armies over the French in the Battle of Waterloo, June 18, 1815. Architect Sir Jeffry Wyattville (1766 – 1840) created the Chamber in 1824 out of several existing rooms. Parliament designated £300,000 for the project. Like most of King George IV's inspirations, it ran well over budget, eventually costing about £1,000,000. Wyattville also remodeled many other areas of Windsor Castle for George IV, William IV, and Queen Victoria; he was buried in the Castle's St. George's Chapel in 1840.

Watercolour of the Waterloo Chamber in 1844 by Joseph Nash

Watercolour of the Waterloo Chamber in 1844 by Joseph Nash

Waterloo Chamber, currently For a virtual tour of the entire Waterloo Chamber, click here.

Waterloo Chamber, currently For a virtual tour of the entire Waterloo Chamber, click here.

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of WellingtonCommander of the Victorious Allied Armies The walls of the Waterloo Chamber are filled with large portraits of the leaders of the Allied efforts. Most of them are painted by Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769-1830), the Regency era's favorite artist. Many were reproduced several times by his studio for numerous placements in other palaces, stately homes and distinguished galleries.

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of WellingtonCommander of the Victorious Allied Armies The walls of the Waterloo Chamber are filled with large portraits of the leaders of the Allied efforts. Most of them are painted by Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769-1830), the Regency era's favorite artist. Many were reproduced several times by his studio for numerous placements in other palaces, stately homes and distinguished galleries.

Prussian General Gebhardt von BlücherWellington's Comrade-in-arms at WaterlooSir Thomas Lawrence 1816 The Prince Regent (later George IV) commissioned Lawrence to paint all the Allied Sovereigns, military leaders, and statesmen. Lawrence traveled around Europe to complete the portraits.

Prussian General Gebhardt von BlücherWellington's Comrade-in-arms at WaterlooSir Thomas Lawrence 1816 The Prince Regent (later George IV) commissioned Lawrence to paint all the Allied Sovereigns, military leaders, and statesmen. Lawrence traveled around Europe to complete the portraits.

Austrian Field Marshal Karl Philipp, Prince of Schwartzenberg,

Austrian Field Marshal Karl Philipp, Prince of Schwartzenberg,

Alexander I, Emperor of Russia (1777-1825)painted by Sir Thomas Lawrence, 1818 According to the Royal Collection Website, "While working on the portrait Lawrence altered the position of the legs, much to the consternation of the Tzar and those courtiers attending the portrait sitting, especially when for a while the sitter was shown with four legs." Obviously, this condition was corrected!

Alexander I, Emperor of Russia (1777-1825)painted by Sir Thomas Lawrence, 1818 According to the Royal Collection Website, "While working on the portrait Lawrence altered the position of the legs, much to the consternation of the Tzar and those courtiers attending the portrait sitting, especially when for a while the sitter was shown with four legs." Obviously, this condition was corrected!

Pope Pius VII, 1819-20 The portrait of Pope Pius VII (1742-1823), painted in Rome, is widely agreed to be Lawrence's masterpiece, both incisive and sympathetic. While heads of state and leading generals were depicted full length, politicians and statesmen were honored with 3/4 length portraits, perhaps putting them in their place?

Pope Pius VII, 1819-20 The portrait of Pope Pius VII (1742-1823), painted in Rome, is widely agreed to be Lawrence's masterpiece, both incisive and sympathetic. While heads of state and leading generals were depicted full length, politicians and statesmen were honored with 3/4 length portraits, perhaps putting them in their place?

Viscount CastlereaghSir Thomas Lawrence, 1830 Robert Stewart (1769-1822), Viscount Castlereagh, later second Marquess of Londonderry, served as Secretary of State for War 1805-09, and Foreign Secretary 1812-1822

Viscount CastlereaghSir Thomas Lawrence, 1830 Robert Stewart (1769-1822), Viscount Castlereagh, later second Marquess of Londonderry, served as Secretary of State for War 1805-09, and Foreign Secretary 1812-1822

Robert Banks Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool Robert Banks Jenkinson (1770-1828), 2nd Earl of Liverpool was Prime Minister from 1812 to 1827, and also preceded the Duke of Wellington as the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports, about which more soon!! In the words of the Windsor Castle guidebook, "Most of the twenty eight portraits were delivered after his [Lawrence's] death on 7 January 1830. By this time work was already begun of the space of the Waterloo Chamber created by covering a courtyard at Windsor Castle with a huge sky-lit vault; the room was completed during the reign of William IV (1830-7)...the arrangement which survives to this day: full-length portraits of warriors hang high, over the two end balconies and around the walls; at ground level full-length portraits of monarchs alternate with half-lengths of diplomats and statesmen."

Robert Banks Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool Robert Banks Jenkinson (1770-1828), 2nd Earl of Liverpool was Prime Minister from 1812 to 1827, and also preceded the Duke of Wellington as the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports, about which more soon!! In the words of the Windsor Castle guidebook, "Most of the twenty eight portraits were delivered after his [Lawrence's] death on 7 January 1830. By this time work was already begun of the space of the Waterloo Chamber created by covering a courtyard at Windsor Castle with a huge sky-lit vault; the room was completed during the reign of William IV (1830-7)...the arrangement which survives to this day: full-length portraits of warriors hang high, over the two end balconies and around the walls; at ground level full-length portraits of monarchs alternate with half-lengths of diplomats and statesmen."

The limewood carvings on the walls were removed from the former Royal Chapel before it was demolished in the 1820s. The carvings date from the 1680's, the work of renowned artist Grinling Gibbons. According to the Castle Guidebook, "The Indian carpet was woven for this room by the inmates of Agra prison for Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee, finally reaching Windsor in 1894. Thought to be the largest seamless carpet in existence, it weighs two tonnes. During the 1992 fire it took 50 soldiers to roll it up and move it to safety." Which brings up a sorrowful subject, the terrible fire of eleven years ago.

The limewood carvings on the walls were removed from the former Royal Chapel before it was demolished in the 1820s. The carvings date from the 1680's, the work of renowned artist Grinling Gibbons. According to the Castle Guidebook, "The Indian carpet was woven for this room by the inmates of Agra prison for Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee, finally reaching Windsor in 1894. Thought to be the largest seamless carpet in existence, it weighs two tonnes. During the 1992 fire it took 50 soldiers to roll it up and move it to safety." Which brings up a sorrowful subject, the terrible fire of eleven years ago.

20 November, 1992 Extensive damage resulted from the fire though the Waterloo Chamber was only slightly damaged, due to the thickness of the walls. Other areas were destroyed and eventually repaired. To pay for the £36.5 million repairs, the Queen opened the State Rooms of Buckingham Palace to the Public, but only when she is in residence elsewhere. When you tour Windsor Castle with Kristine and me, you will see the renovated areas and where the fire burned. And we will view the Waterloo Chamber -- and all the State rooms, most of them still very much as they were when redone for George IV by Sir Jeffry Wyattville. Again to access more information on the Wellington Tour, go to http://wellingtontour.blogspot.com/

20 November, 1992 Extensive damage resulted from the fire though the Waterloo Chamber was only slightly damaged, due to the thickness of the walls. Other areas were destroyed and eventually repaired. To pay for the £36.5 million repairs, the Queen opened the State Rooms of Buckingham Palace to the Public, but only when she is in residence elsewhere. When you tour Windsor Castle with Kristine and me, you will see the renovated areas and where the fire burned. And we will view the Waterloo Chamber -- and all the State rooms, most of them still very much as they were when redone for George IV by Sir Jeffry Wyattville. Again to access more information on the Wellington Tour, go to http://wellingtontour.blogspot.com/

.

.

Published on November 01, 2013 00:30

October 30, 2013

At the King's Table by Susanne Groom

Victoria here, reporting on a meeting I attended recently at Chicago's Newberry Library. Cosponsored by the Royal Oak Foundation, the U.S. support group for Britain's National Trust, and Historic Royal Palaces Inc., I met my pal Susan Forgue to hear Suzanne Groom speak about her new book, At the King's Table.

In addition to many other activities, the Royal Oak Foundation brings speakers to various cities around the U.S. for fascinating illustrated lectures. To learn more about the Royal Oak Foundation, click here. Historic Royal Palaces website is here. And, to complete the picture, click here for the Newberry Library website.

In addition to many other activities, the Royal Oak Foundation brings speakers to various cities around the U.S. for fascinating illustrated lectures. To learn more about the Royal Oak Foundation, click here. Historic Royal Palaces website is here. And, to complete the picture, click here for the Newberry Library website. Suzanne Groom, author of At the King's Table

Suzanne Groom, author of At the King's Table The Newberry Library in October Ms. Groom spent 25 years with Historic Royal Palaces, working at projects at Hampton Court, the Banqueting House and Kew Palace. Her account, beautifully illustrated, of the feasts held by the Kings of England, goes back to William the Conqueror. I cannot begin to reproduce all her fascinating stories of Royal Banquets, but I can recount a few. You will find much, much more in the book.

The Newberry Library in October Ms. Groom spent 25 years with Historic Royal Palaces, working at projects at Hampton Court, the Banqueting House and Kew Palace. Her account, beautifully illustrated, of the feasts held by the Kings of England, goes back to William the Conqueror. I cannot begin to reproduce all her fascinating stories of Royal Banquets, but I can recount a few. You will find much, much more in the book.

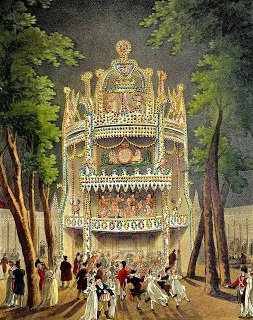

The Field of Cloth of Gold, 1774 Print by James Basire from a 16th-century painting in the Royal Collection. In June of 1520, two young kings, accompanied by their queens, large retinues of knights and retainers and hundreds of servants, met for a conference, jousting and games, music and dancing, and an unprecedented effort to out-impress one another with their sumptuous banquets and extravagant arrangements. Henry VIII and François I of France met at the Field of Cloth of Gold in France, for weeks of celebration of the recent treaty of friendship between the two traditional enemy nations. Despite the fine cuisine and the jolly time for all of those above the scullery help, the friendship was enmity again within a few years. The name of the event grew out of the lavish use for tents, furnishing, and attire of cloth woven with gold thread.

The Field of Cloth of Gold, 1774 Print by James Basire from a 16th-century painting in the Royal Collection. In June of 1520, two young kings, accompanied by their queens, large retinues of knights and retainers and hundreds of servants, met for a conference, jousting and games, music and dancing, and an unprecedented effort to out-impress one another with their sumptuous banquets and extravagant arrangements. Henry VIII and François I of France met at the Field of Cloth of Gold in France, for weeks of celebration of the recent treaty of friendship between the two traditional enemy nations. Despite the fine cuisine and the jolly time for all of those above the scullery help, the friendship was enmity again within a few years. The name of the event grew out of the lavish use for tents, furnishing, and attire of cloth woven with gold thread.

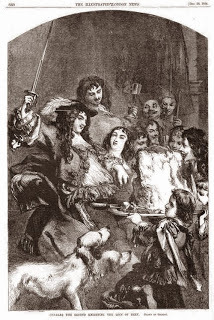

Charles II knighting the beef: Sir Loin An old tale that is difficult to verify tells of a monarch -- in various versions Henry VIII, Elizabeth I, James I, or Charles II -- who drew a sword and knighted a delicious cut of beef. "Arise, Sir Loin," the monarch supposedly said, and thus the finest cuts of beef are so named. True or not, it is an amusing story.

Charles II knighting the beef: Sir Loin An old tale that is difficult to verify tells of a monarch -- in various versions Henry VIII, Elizabeth I, James I, or Charles II -- who drew a sword and knighted a delicious cut of beef. "Arise, Sir Loin," the monarch supposedly said, and thus the finest cuts of beef are so named. True or not, it is an amusing story. Coronation Banquet for James II

Coronation Banquet for James IIA story that is substantiated in many accounts is the coronation banquet of James II (1633-1701), held in Westminster Hall, April 23, 1685. It began at 11:30 am with the arrival of the King and Queen, but other participants had to be in place much earlier. Royalty departed at 7 pm, after the diners had been served 1,145 dishes, including many cuts of meat, sweetmeats, jellies and blancmange. James II did not last long as king; he was replaced in the Glorious Revolution of 1688 by William III of Orange and his Queen, James's daughter Mary.

King's Eating Room, Hampton Court Palace William and Mary added on to Hampton Court Palace, and the King's Eating Room is now available for you to hire for your own soiree, if you so desire. As the website says, "It seems an odd idea to us now, but if you visited court in the 18th century one of the highlights would be watching the king eating his dinner. Anyone respectable enough and well-dressed enough (ie, wearing their coat, wig, sword….) would be admitted to see the sight, which took place several times a month. During public dining, King William III or King George II would not sit down to eat with their friends, but would be served in solitary splendour at a table in this room, with the crowds of spectators respectfully standing back. For more information, click here.

King's Eating Room, Hampton Court Palace William and Mary added on to Hampton Court Palace, and the King's Eating Room is now available for you to hire for your own soiree, if you so desire. As the website says, "It seems an odd idea to us now, but if you visited court in the 18th century one of the highlights would be watching the king eating his dinner. Anyone respectable enough and well-dressed enough (ie, wearing their coat, wig, sword….) would be admitted to see the sight, which took place several times a month. During public dining, King William III or King George II would not sit down to eat with their friends, but would be served in solitary splendour at a table in this room, with the crowds of spectators respectfully standing back. For more information, click here.

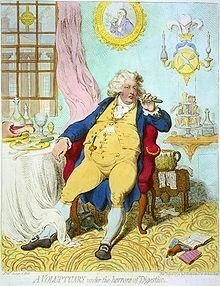

Coronation Banquet of George IV, 1821 Westminster Hall was also the scene of George IV's coronation banquet, the last one held there, although many of us certainly remember the Diamond Jubilee luncheon served there in 2012. As his reputation as a Voluptuary (see Gillray, below) might predict, George IV presided over an expensive and (melo)dramatic pageant for his coronation, which is probably best remembered for locking the door against his estranged wife, who was prepared to be crowned as queen. One of the accounts of the banquet enumerated some of the dishes served, "soups including turtle, salmon, turbot, and trout, venison and veal, mutton and beef, braised ham and savoury pies, daubed geese and braised capon, lobster and crayfish, cold roast fowl and cold lamb, potatoes, peas and cauliflower. There were mounted pastries, dishes of jellies and creams, over a thousand side dishes, nearly five hundred sauce boats brimming with lobster sauce, butter sauce and mint."

Coronation Banquet of George IV, 1821 Westminster Hall was also the scene of George IV's coronation banquet, the last one held there, although many of us certainly remember the Diamond Jubilee luncheon served there in 2012. As his reputation as a Voluptuary (see Gillray, below) might predict, George IV presided over an expensive and (melo)dramatic pageant for his coronation, which is probably best remembered for locking the door against his estranged wife, who was prepared to be crowned as queen. One of the accounts of the banquet enumerated some of the dishes served, "soups including turtle, salmon, turbot, and trout, venison and veal, mutton and beef, braised ham and savoury pies, daubed geese and braised capon, lobster and crayfish, cold roast fowl and cold lamb, potatoes, peas and cauliflower. There were mounted pastries, dishes of jellies and creams, over a thousand side dishes, nearly five hundred sauce boats brimming with lobster sauce, butter sauce and mint.".

A Voluptuary under the horrors of Digestion, James Gillray, 1792British Museum This post is just nibble (pun intended) of the delights in Suzanne Groom's new book, At the King's Table. I will add that the sponsors of her talk had the good taste to serve cheese and crackers and a small glass of wine rather than compete with royalty!

A Voluptuary under the horrors of Digestion, James Gillray, 1792British Museum This post is just nibble (pun intended) of the delights in Suzanne Groom's new book, At the King's Table. I will add that the sponsors of her talk had the good taste to serve cheese and crackers and a small glass of wine rather than compete with royalty!Soon, an account of an exhibition at the Newberry Library concerning the American Civil War -- including the role of Great Britain

Published on October 30, 2013 00:30

October 28, 2013

Victoria Explores Euston/St. Pancras

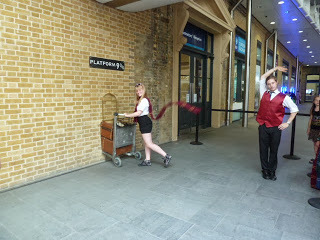

On a warm morning last July, Ed and I returned to London from our marvelous foray into East Anglia. Ed was still worried about his sore foot and not too enthused about running around in London for the rest of our trip. So we decided to stay close to "home" for the afternoon. On our way out of the King's Cross RR Station we saw this cute display of Platform 9 3/4 where the students at Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry leave London in the Harry Potter books.

Outside, the Northern Hotel, next to Kings Cross has been attractively renovated.

Outside, the Northern Hotel, next to Kings Cross has been attractively renovated.

St. Pancras Station And next door to King's Cross and the Northern Hotel is St. Pancras, now the terminal for the Eurostar trains to Paris and Brussels. As such, it has caused a dramatic gentrification in the neighborhood. Almost all the buildings nearby along Euston Road were wrapped in scaffolding and cranes pierced the skies everywhere. We saw many signs for the offices of international conglomerates.

St. Pancras Station And next door to King's Cross and the Northern Hotel is St. Pancras, now the terminal for the Eurostar trains to Paris and Brussels. As such, it has caused a dramatic gentrification in the neighborhood. Almost all the buildings nearby along Euston Road were wrapped in scaffolding and cranes pierced the skies everywhere. We saw many signs for the offices of international conglomerates.

through the traffic to Chalton Street We found several pubs and bistros on Chalton Street beside our hotel, and I wondered how long this thoroughfare of little shops and newsstands could withstand the pressure of rising prices and new construction all around. Seems sad they might have to move and be replaced by the same chains one sees in Piccadilly. That's the down side of gentrification.

through the traffic to Chalton Street We found several pubs and bistros on Chalton Street beside our hotel, and I wondered how long this thoroughfare of little shops and newsstands could withstand the pressure of rising prices and new construction all around. Seems sad they might have to move and be replaced by the same chains one sees in Piccadilly. That's the down side of gentrification.

St. Pancras Hotel The upside of gentrification is the renovation of great old buildings like the Northern Hotel and the St. Pancras Hotel. a fantasy of Victorian wretched excess that is quite charming for all its Neo-Gothic extremes. Here are a few shots of the exterior décor.

St. Pancras Hotel The upside of gentrification is the renovation of great old buildings like the Northern Hotel and the St. Pancras Hotel. a fantasy of Victorian wretched excess that is quite charming for all its Neo-Gothic extremes. Here are a few shots of the exterior décor.

I assume the Hotel, a very posh place, has antidotes to nightmares caused by these gargoyles. The architect of the hotel, opened originally in 1868 as the Midland Grand Hotel, was Sir George Gilbert Scott (1811-1878), who is also responsible for the Albert Memorial in Hyde Park and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office in Whitehall at King Charles Street. Sir George would be proud of the restoration I am sure. Although we could hardly afford to stay there, we did enjoy a wonderful luncheon in the restaurant called "The Booking Office."

I assume the Hotel, a very posh place, has antidotes to nightmares caused by these gargoyles. The architect of the hotel, opened originally in 1868 as the Midland Grand Hotel, was Sir George Gilbert Scott (1811-1878), who is also responsible for the Albert Memorial in Hyde Park and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office in Whitehall at King Charles Street. Sir George would be proud of the restoration I am sure. Although we could hardly afford to stay there, we did enjoy a wonderful luncheon in the restaurant called "The Booking Office."

Vicky, Rev. Susan, Dr. Jim, and Ed

Vicky, Rev. Susan, Dr. Jim, and Ed

View from Pullman St. Pancras Hotel of the British Library (foreground) and the St. Pancras Hotel and Station in Euston Road

View from Pullman St. Pancras Hotel of the British Library (foreground) and the St. Pancras Hotel and Station in Euston Road

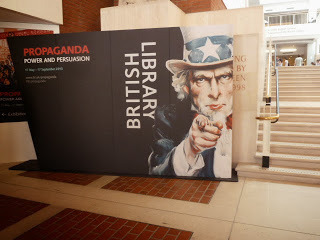

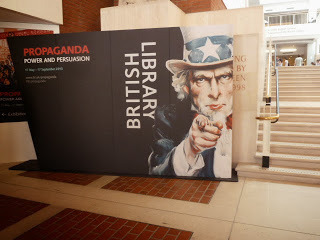

Exhibit in the British Library In the courtyard of the BL, an people were enjoying the warm afternoon, sipping cool drinks, reading, talking and/or checking their mobiles. We visited the Propaganda exhibit, then walked around the permanent exhibit where there are copies of the Magna Carta, ancient maps, the Beatles' songs, Jane Austen's desk, and other fascinating manuscripts and objects.

Exhibit in the British Library In the courtyard of the BL, an people were enjoying the warm afternoon, sipping cool drinks, reading, talking and/or checking their mobiles. We visited the Propaganda exhibit, then walked around the permanent exhibit where there are copies of the Magna Carta, ancient maps, the Beatles' songs, Jane Austen's desk, and other fascinating manuscripts and objects.

Sir Joseph Banks (1743-1820)by sculptor Anne Seymour DamerAmong the busts of the Library Founders.

Sir Joseph Banks (1743-1820)by sculptor Anne Seymour DamerAmong the busts of the Library Founders.

In the gift/book shop

In the gift/book shop

Looking at our tall hotel from the BL Courtyard

Looking at our tall hotel from the BL Courtyard

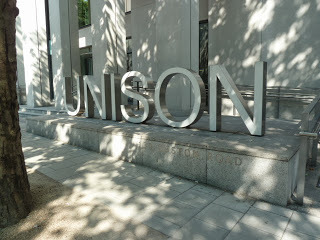

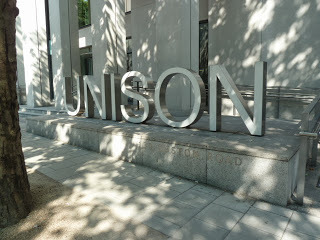

The Elizabeth Garret Anderson Hospital A little farther west on Euston Road, near Euston Station, is the building above, which was built by Britain's first woman physician and surgeon. It has become part of the new National Headquarters for the public service trade union Unison. Elizabeth Garret Anderson's life story is fascinating. Check it out here.

The Elizabeth Garret Anderson Hospital A little farther west on Euston Road, near Euston Station, is the building above, which was built by Britain's first woman physician and surgeon. It has become part of the new National Headquarters for the public service trade union Unison. Elizabeth Garret Anderson's life story is fascinating. Check it out here.

Two more neighborhood institutions were well worth our visit. The St. Pancras Church at the corner of Euston Road and Upper Woburn Place was constructed in 1819-1822 and designed by architect William Inwood and his son, Henry Inwood.

Two more neighborhood institutions were well worth our visit. The St. Pancras Church at the corner of Euston Road and Upper Woburn Place was constructed in 1819-1822 and designed by architect William Inwood and his son, Henry Inwood.

The building was modeled on two Athens landmarks from the Acropolis: the Tower of the Winds and the Erechtheum, the latter with its Ionic columns and the Porch of the Caryatids.

The building was modeled on two Athens landmarks from the Acropolis: the Tower of the Winds and the Erechtheum, the latter with its Ionic columns and the Porch of the Caryatids.

Porch of the Caryatids

Porch of the Caryatids

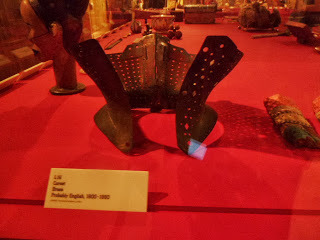

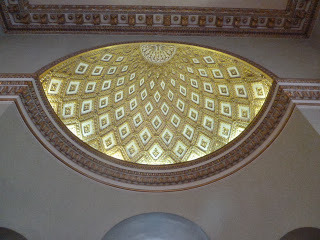

The Apse, St. Pancras Church The final neighborhood attraction we visited was the fascinating premises of the Wellcome Collection. The objects displayed were acquired by Sir Henry Wellcome (1845-1936), who explored the relationship of art, medicine, and the human body.

The Apse, St. Pancras Church The final neighborhood attraction we visited was the fascinating premises of the Wellcome Collection. The objects displayed were acquired by Sir Henry Wellcome (1845-1936), who explored the relationship of art, medicine, and the human body.

beakers, two of 100's

beakers, two of 100's

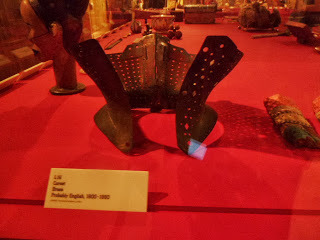

Iron Corset

Iron Corset

A Chastity Belt of iron and velvet The Wellcome Collection advertises itself as "the free destination for the incurably curious." Ed ad I found this a perfect description of the odd assortment of items in the museum. Also part of the Wellcome Trust are educational organizations and a medical library. If you are looking for the unusual in London, you will find it here. We enjoyed this Euston Road neighborhood, with its diverse institutions and attractions.

A Chastity Belt of iron and velvet The Wellcome Collection advertises itself as "the free destination for the incurably curious." Ed ad I found this a perfect description of the odd assortment of items in the museum. Also part of the Wellcome Trust are educational organizations and a medical library. If you are looking for the unusual in London, you will find it here. We enjoyed this Euston Road neighborhood, with its diverse institutions and attractions.

View of the City from the Pullman Hotel, St. Paul's Cathedral at the far right in the distance My visit to the Wellington Arch is coming soon.

View of the City from the Pullman Hotel, St. Paul's Cathedral at the far right in the distance My visit to the Wellington Arch is coming soon.

Outside, the Northern Hotel, next to Kings Cross has been attractively renovated.

Outside, the Northern Hotel, next to Kings Cross has been attractively renovated.

St. Pancras Station And next door to King's Cross and the Northern Hotel is St. Pancras, now the terminal for the Eurostar trains to Paris and Brussels. As such, it has caused a dramatic gentrification in the neighborhood. Almost all the buildings nearby along Euston Road were wrapped in scaffolding and cranes pierced the skies everywhere. We saw many signs for the offices of international conglomerates.

St. Pancras Station And next door to King's Cross and the Northern Hotel is St. Pancras, now the terminal for the Eurostar trains to Paris and Brussels. As such, it has caused a dramatic gentrification in the neighborhood. Almost all the buildings nearby along Euston Road were wrapped in scaffolding and cranes pierced the skies everywhere. We saw many signs for the offices of international conglomerates.

through the traffic to Chalton Street We found several pubs and bistros on Chalton Street beside our hotel, and I wondered how long this thoroughfare of little shops and newsstands could withstand the pressure of rising prices and new construction all around. Seems sad they might have to move and be replaced by the same chains one sees in Piccadilly. That's the down side of gentrification.

through the traffic to Chalton Street We found several pubs and bistros on Chalton Street beside our hotel, and I wondered how long this thoroughfare of little shops and newsstands could withstand the pressure of rising prices and new construction all around. Seems sad they might have to move and be replaced by the same chains one sees in Piccadilly. That's the down side of gentrification.

St. Pancras Hotel The upside of gentrification is the renovation of great old buildings like the Northern Hotel and the St. Pancras Hotel. a fantasy of Victorian wretched excess that is quite charming for all its Neo-Gothic extremes. Here are a few shots of the exterior décor.

St. Pancras Hotel The upside of gentrification is the renovation of great old buildings like the Northern Hotel and the St. Pancras Hotel. a fantasy of Victorian wretched excess that is quite charming for all its Neo-Gothic extremes. Here are a few shots of the exterior décor.

I assume the Hotel, a very posh place, has antidotes to nightmares caused by these gargoyles. The architect of the hotel, opened originally in 1868 as the Midland Grand Hotel, was Sir George Gilbert Scott (1811-1878), who is also responsible for the Albert Memorial in Hyde Park and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office in Whitehall at King Charles Street. Sir George would be proud of the restoration I am sure. Although we could hardly afford to stay there, we did enjoy a wonderful luncheon in the restaurant called "The Booking Office."

I assume the Hotel, a very posh place, has antidotes to nightmares caused by these gargoyles. The architect of the hotel, opened originally in 1868 as the Midland Grand Hotel, was Sir George Gilbert Scott (1811-1878), who is also responsible for the Albert Memorial in Hyde Park and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office in Whitehall at King Charles Street. Sir George would be proud of the restoration I am sure. Although we could hardly afford to stay there, we did enjoy a wonderful luncheon in the restaurant called "The Booking Office."

Vicky, Rev. Susan, Dr. Jim, and Ed

Vicky, Rev. Susan, Dr. Jim, and Ed

View from Pullman St. Pancras Hotel of the British Library (foreground) and the St. Pancras Hotel and Station in Euston Road

View from Pullman St. Pancras Hotel of the British Library (foreground) and the St. Pancras Hotel and Station in Euston Road

Exhibit in the British Library In the courtyard of the BL, an people were enjoying the warm afternoon, sipping cool drinks, reading, talking and/or checking their mobiles. We visited the Propaganda exhibit, then walked around the permanent exhibit where there are copies of the Magna Carta, ancient maps, the Beatles' songs, Jane Austen's desk, and other fascinating manuscripts and objects.

Exhibit in the British Library In the courtyard of the BL, an people were enjoying the warm afternoon, sipping cool drinks, reading, talking and/or checking their mobiles. We visited the Propaganda exhibit, then walked around the permanent exhibit where there are copies of the Magna Carta, ancient maps, the Beatles' songs, Jane Austen's desk, and other fascinating manuscripts and objects.

Sir Joseph Banks (1743-1820)by sculptor Anne Seymour DamerAmong the busts of the Library Founders.

Sir Joseph Banks (1743-1820)by sculptor Anne Seymour DamerAmong the busts of the Library Founders.

In the gift/book shop

In the gift/book shop

Looking at our tall hotel from the BL Courtyard

Looking at our tall hotel from the BL Courtyard

The Elizabeth Garret Anderson Hospital A little farther west on Euston Road, near Euston Station, is the building above, which was built by Britain's first woman physician and surgeon. It has become part of the new National Headquarters for the public service trade union Unison. Elizabeth Garret Anderson's life story is fascinating. Check it out here.

The Elizabeth Garret Anderson Hospital A little farther west on Euston Road, near Euston Station, is the building above, which was built by Britain's first woman physician and surgeon. It has become part of the new National Headquarters for the public service trade union Unison. Elizabeth Garret Anderson's life story is fascinating. Check it out here.

Two more neighborhood institutions were well worth our visit. The St. Pancras Church at the corner of Euston Road and Upper Woburn Place was constructed in 1819-1822 and designed by architect William Inwood and his son, Henry Inwood.

Two more neighborhood institutions were well worth our visit. The St. Pancras Church at the corner of Euston Road and Upper Woburn Place was constructed in 1819-1822 and designed by architect William Inwood and his son, Henry Inwood.

The building was modeled on two Athens landmarks from the Acropolis: the Tower of the Winds and the Erechtheum, the latter with its Ionic columns and the Porch of the Caryatids.

The building was modeled on two Athens landmarks from the Acropolis: the Tower of the Winds and the Erechtheum, the latter with its Ionic columns and the Porch of the Caryatids.

Porch of the Caryatids

Porch of the Caryatids

The Apse, St. Pancras Church The final neighborhood attraction we visited was the fascinating premises of the Wellcome Collection. The objects displayed were acquired by Sir Henry Wellcome (1845-1936), who explored the relationship of art, medicine, and the human body.

The Apse, St. Pancras Church The final neighborhood attraction we visited was the fascinating premises of the Wellcome Collection. The objects displayed were acquired by Sir Henry Wellcome (1845-1936), who explored the relationship of art, medicine, and the human body.

beakers, two of 100's

beakers, two of 100's

Iron Corset

Iron Corset

A Chastity Belt of iron and velvet The Wellcome Collection advertises itself as "the free destination for the incurably curious." Ed ad I found this a perfect description of the odd assortment of items in the museum. Also part of the Wellcome Trust are educational organizations and a medical library. If you are looking for the unusual in London, you will find it here. We enjoyed this Euston Road neighborhood, with its diverse institutions and attractions.

A Chastity Belt of iron and velvet The Wellcome Collection advertises itself as "the free destination for the incurably curious." Ed ad I found this a perfect description of the odd assortment of items in the museum. Also part of the Wellcome Trust are educational organizations and a medical library. If you are looking for the unusual in London, you will find it here. We enjoyed this Euston Road neighborhood, with its diverse institutions and attractions.

View of the City from the Pullman Hotel, St. Paul's Cathedral at the far right in the distance My visit to the Wellington Arch is coming soon.

View of the City from the Pullman Hotel, St. Paul's Cathedral at the far right in the distance My visit to the Wellington Arch is coming soon.

Published on October 28, 2013 00:30

October 25, 2013

Artist Thomas Sully in Milwaukee

Victoria here, reporting on a wonderful exhibition at my local hang-out, the Milwaukee Art Museum. Last year about this time I was observing the wonderful exhibition at the MAM from London's Kenwood House. Click here if you need a reminder.

This autumn we are fortunate to have a gathering of works from many museums for Thomas Sully: Painted Performance. After it closes in Milwaukee in January, the exhibition will travel to the San Antonio Museum of Art February 7 through May 11, 2014.

Lady with a Harp Eliza Ridgeway, 1818, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. This is one of my favorite paintings in Washington and I usually breeze by to say hello on my annual forays to the capital. Now here she is in my front yard.

Lady with a Harp Eliza Ridgeway, 1818, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. This is one of my favorite paintings in Washington and I usually breeze by to say hello on my annual forays to the capital. Now here she is in my front yard.

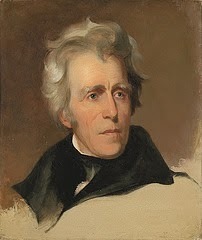

Andrew Jackson, 1845National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. The Andrew Jackson portrait is very familiar to all Americans as the inspiration of the etching on the $20 bill.

Andrew Jackson, 1845National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. The Andrew Jackson portrait is very familiar to all Americans as the inspiration of the etching on the $20 bill.

Thomas Sully (1783–1872) was born in Lincolnshire, England, to a family in the theatrical business. In 1792, they settled in Charleston, South Carolina. Though young Tom often acted, his skills in sketching and painting were soon evident. Eventually he worked with his brother Lawrence, also a painter. Tom moved around from Richmond, VA, to New York, and for a while to Boston to study with Gilbert Stuart, perhaps the young republic's most renowned artist. Sully settled in Philadelphia in 1806; there he stayed for the rest of his life, other than time in 1809 studying in London with Benjamin West and later a London trip to paint the young Queen Victoria in 1837-38.

Thomas Sully (1783–1872) was born in Lincolnshire, England, to a family in the theatrical business. In 1792, they settled in Charleston, South Carolina. Though young Tom often acted, his skills in sketching and painting were soon evident. Eventually he worked with his brother Lawrence, also a painter. Tom moved around from Richmond, VA, to New York, and for a while to Boston to study with Gilbert Stuart, perhaps the young republic's most renowned artist. Sully settled in Philadelphia in 1806; there he stayed for the rest of his life, other than time in 1809 studying in London with Benjamin West and later a London trip to paint the young Queen Victoria in 1837-38.

Queen Victoria, Metropolitan Museum of Art Other versions of this painting hang in the Wallace Collection in London and the Royal Collection as well. Below, a full length version, not in this exhibition.

Queen Victoria, Metropolitan Museum of Art Other versions of this painting hang in the Wallace Collection in London and the Royal Collection as well. Below, a full length version, not in this exhibition.

Queen Victoria, 1838Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC Among the amazing 2300 pictures Sully painted are many American politicians and other citizens, both men and women. The focus of this MAM exhibition is performance, particularly on the stage.

Queen Victoria, 1838Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC Among the amazing 2300 pictures Sully painted are many American politicians and other citizens, both men and women. The focus of this MAM exhibition is performance, particularly on the stage.

George Frederick Cooke, in the role of Shakespeare's Richard III Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts

George Frederick Cooke, in the role of Shakespeare's Richard III Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts

Famed Actress Frances Anne (Fanny) Kemble as Beatrice, 1833Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts

Famed Actress Frances Anne (Fanny) Kemble as Beatrice, 1833Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts

Sarah Esther Hindman as Little Red Riding Hood, 1833 The Maryland State Archives, Photo by Harry Connolly Sully not only painted actors; he also produced many paintings illustrating scenes from books and other "Fancy" pictures, many of which were reproduced for widespread purchase and display in everyday homes.

Sarah Esther Hindman as Little Red Riding Hood, 1833 The Maryland State Archives, Photo by Harry Connolly Sully not only painted actors; he also produced many paintings illustrating scenes from books and other "Fancy" pictures, many of which were reproduced for widespread purchase and display in everyday homes.

Prison Scene from James Fenimore Cooper's "The Pilot", 1841Birmingham (AL) Museum of Art

Prison Scene from James Fenimore Cooper's "The Pilot", 1841Birmingham (AL) Museum of Art

Little Nell Asleep in Dickens' The Old Curiosity ShopFree Library of Philadelphia

Little Nell Asleep in Dickens' The Old Curiosity ShopFree Library of Philadelphia

Cinderella at the Kitchen Fire, 1843Dallas Museum of Art Among Thomas Sully's most prized paintings are his many portraits, and particularly the adorable lad below, beloved to generations of MFA visitors.

Cinderella at the Kitchen Fire, 1843Dallas Museum of Art Among Thomas Sully's most prized paintings are his many portraits, and particularly the adorable lad below, beloved to generations of MFA visitors.

The Torn Hat, 1820© 2013, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The Torn Hat, 1820© 2013, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Major Thomas Biddle, 1818Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia I am looking forward to rambling around among these pictures many times in the next couple of months. Sully's work has a luminosity I love. When this blog visited the Look of Love exhibition in Birmingham, we became acquainted with Tom Sully, great , great, great grandson of Thomas Sully and himself a renowned artist. For our interview with Tom, click here. This is the first Thomas Sully retrospective in thirty years, showing about eighty paintings. Thomas Sully: Painted Performance is organized by the Milwaukee Art Museum, co-curated by Dr. William Keyse Rudolph, the Museum’s Dudley J. Godfrey Jr. Curator of American Art and Decorative Arts and Director of Exhibitions, and Dr. Carol Eaton Soltis, Project Associate Curator of American Art, Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Major Thomas Biddle, 1818Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia I am looking forward to rambling around among these pictures many times in the next couple of months. Sully's work has a luminosity I love. When this blog visited the Look of Love exhibition in Birmingham, we became acquainted with Tom Sully, great , great, great grandson of Thomas Sully and himself a renowned artist. For our interview with Tom, click here. This is the first Thomas Sully retrospective in thirty years, showing about eighty paintings. Thomas Sully: Painted Performance is organized by the Milwaukee Art Museum, co-curated by Dr. William Keyse Rudolph, the Museum’s Dudley J. Godfrey Jr. Curator of American Art and Decorative Arts and Director of Exhibitions, and Dr. Carol Eaton Soltis, Project Associate Curator of American Art, Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Published on October 25, 2013 00:30

October 23, 2013

The Jane Austen Society in Minneapolis

Seven hundred fans and scholars met in Minneapolis at the end of September for immersion in All Things Jane. Victoria here, relating my experience celebrating two hundred years of Pride and Prejudice with so many of those who love it too. Many thanks to Dave O'Brien for the use of his excellent photos, more of which can be seen on the JASNA-WI website.

Minneapolis, 2013 As always at an AGM, part of the fun is touring the city and surroundings...and we had perfect weather to enjoy such treats as the Guthrie Theatre, the Mill Museum, tours devoted to F. Scott Fitzgerald and Sherlock Holmes, plus the art museums and pub crawls.

Minneapolis, 2013 As always at an AGM, part of the fun is touring the city and surroundings...and we had perfect weather to enjoy such treats as the Guthrie Theatre, the Mill Museum, tours devoted to F. Scott Fitzgerald and Sherlock Holmes, plus the art museums and pub crawls.

The Emporium Another popular feature of an AGM the Emporium where JASNA chapters and commercial providers have their sales tables. Books, hats, fans, pens and paper, English antique tea cups, all sorts of temptations abound.

The Emporium Another popular feature of an AGM the Emporium where JASNA chapters and commercial providers have their sales tables. Books, hats, fans, pens and paper, English antique tea cups, all sorts of temptations abound. Kathy O'Brien entertains the Queen, Liz Cooper and a customer forJASNA-WI's 2014 Calendar. To order yours, click here.

Kathy O'Brien entertains the Queen, Liz Cooper and a customer forJASNA-WI's 2014 Calendar. To order yours, click here.

Below, editor Tim Bullamore collects subscribers to Jane Austen's Regency World magazine.

For more information on JARW, click here.

For more information on JARW, click here.

Jane Austen Books is always a popular vendor.

Jane Austen Books is always a popular vendor.

The Regency Room featured the antique collection of author Candice Hern, left with JASNA President Iris Lutz (in May 2013 in Madison, WI)

The Regency Room featured the antique collection of author Candice Hern, left with JASNA President Iris Lutz (in May 2013 in Madison, WI)

For more on Candice's Collections, click here.

For more on Candice's Collections, click here. As in the past few years, the JASNA AGM events have become so numerous that many are held on the day before the official Keynote. In additions to tours and workshops, Thursday's speakers included Candice Hern on Regency Magazines; Bruce Richardson on the History of Tea and Jane Austen; a High Tea and Fashion Show; and Curtain Raiser Jocelyn Harris speaking on "Introducing Elizabeth Bennet."

As in the past few years, the JASNA AGM events have become so numerous that many are held on the day before the official Keynote. In additions to tours and workshops, Thursday's speakers included Candice Hern on Regency Magazines; Bruce Richardson on the History of Tea and Jane Austen; a High Tea and Fashion Show; and Curtain Raiser Jocelyn Harris speaking on "Introducing Elizabeth Bennet."

William Phillips of Chicago, a JASNA favorite speaker, spoke on card games: "Pride, Prejudice and Piquet" Friday morning was also crowded with tours, workshops dance lessons and excellent presentations.

William Phillips of Chicago, a JASNA favorite speaker, spoke on card games: "Pride, Prejudice and Piquet" Friday morning was also crowded with tours, workshops dance lessons and excellent presentations.

Sandy Lerner spoke on "Pen and Parsimony: Carriages in the Novels of Jane Austen"

Sandy Lerner spoke on "Pen and Parsimony: Carriages in the Novels of Jane Austen"

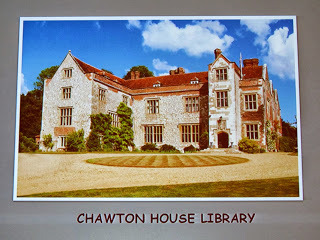

Steve Lawrence, CEO of Chawton House Library, updated us on events there.

Steve Lawrence, CEO of Chawton House Library, updated us on events there.

I attended the Frances Burney Society AGM, Luncheon, and excellent talk by Dr. Lorna Clark who spoke about Burney's private writings in the context of her work editing a new edition of two volumes of The Court Journals and Letters of Frances Burney.

I attended the Frances Burney Society AGM, Luncheon, and excellent talk by Dr. Lorna Clark who spoke about Burney's private writings in the context of her work editing a new edition of two volumes of The Court Journals and Letters of Frances Burney.

Dr. Lorna Clark

Dr. Lorna Clark  The Opening Plenary Session of the 2013 JASNA AGM,The Carol Medine Moss Keynote Lecture,a very entertaining and insightful session.

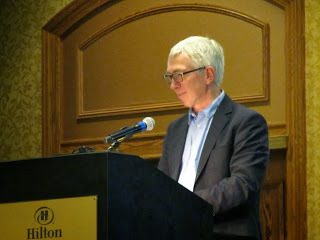

The Opening Plenary Session of the 2013 JASNA AGM,The Carol Medine Moss Keynote Lecture,a very entertaining and insightful session. Professor James Mullan of University College LondonSpeechless in Pride and Prejudiceauthor of What Matters in Jane Austen: 20 Crucial Puzzles Solved

Professor James Mullan of University College LondonSpeechless in Pride and Prejudiceauthor of What Matters in Jane Austen: 20 Crucial Puzzles Solved

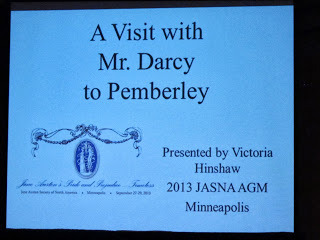

My turn for a Break-out Session

My turn for a Break-out Session

She is SERIOUS!ABC Nightline filmed my entire presentation, but I fear I ended up on the cutting room floor.

She is SERIOUS!ABC Nightline filmed my entire presentation, but I fear I ended up on the cutting room floor.

Here I am at the book signing on Friday evening. In the middle is the Japanese Manga version ofMiss Milford's Mistake. I'd brought it as an object of curiosity, but a lady bought it to send to a library in Japan. What fun! Thanks to Julie Klassen for the picture! Here are some other views of Break-out speakers.

Here I am at the book signing on Friday evening. In the middle is the Japanese Manga version ofMiss Milford's Mistake. I'd brought it as an object of curiosity, but a lady bought it to send to a library in Japan. What fun! Thanks to Julie Klassen for the picture! Here are some other views of Break-out speakers.  Juliet McMaster

Juliet McMaster Jeffrey Nigro

Jeffrey Nigro The Bingley Sisters: Liz Philosophos Cooper and Molly Philosophos

The Bingley Sisters: Liz Philosophos Cooper and Molly Philosophos Susan Forgue

Susan Forgue Teresa Kinney, Joan Ray, and Cheryl Kinney

Teresa Kinney, Joan Ray, and Cheryl Kinney

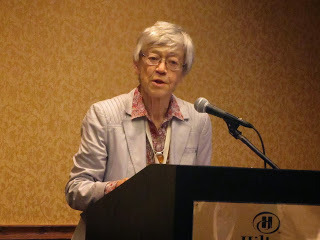

Plenary speaker Joan K. Ray on "Do Elizabeth and Darcy Really Improve Upon Acquaintance?"Dr. Ray challenged us with a new approach to Darcy's tolerance and Elizabeth's grudge. Plenary speaker Janine Barchas discussed "Naming Names in Pride and Prejudice" particularly the Fitzwilliam family of Wentworth Woodhouse and other "celebrity teasers" hidden in plain sight. These and other interesting sidelights on Jane Austen's characters can be found in Barchas's book, Matters of Fact in Jane Austen.

Plenary speaker Joan K. Ray on "Do Elizabeth and Darcy Really Improve Upon Acquaintance?"Dr. Ray challenged us with a new approach to Darcy's tolerance and Elizabeth's grudge. Plenary speaker Janine Barchas discussed "Naming Names in Pride and Prejudice" particularly the Fitzwilliam family of Wentworth Woodhouse and other "celebrity teasers" hidden in plain sight. These and other interesting sidelights on Jane Austen's characters can be found in Barchas's book, Matters of Fact in Jane Austen.

Nili Olay and Jerry Vetowich, after the Saturday Banquet

Nili Olay and Jerry Vetowich, after the Saturday Banquet

The Bingley Sisters lead the costumed promenade through the neighborhood

The Bingley Sisters lead the costumed promenade through the neighborhood

Bill Pierson instructs us on tasting "Libations In the Regency Manner"

Bill Pierson instructs us on tasting "Libations In the Regency Manner"

Sunday's Closing Brunch

Sunday's Closing Brunch

The Lizzie Bennet Diaries team on how they adapted Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice for You-Tube episodes and won an Emmy!

The Lizzie Bennet Diaries team on how they adapted Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice for You-Tube episodes and won an Emmy!  After packing in so many activities in just a few days, we say farewell to the Minneapolis AGM and look forward to Montreal in 2014Thanks again to Dave O'Brien for most of the photos. See more athttp://jasnawi.org/

After packing in so many activities in just a few days, we say farewell to the Minneapolis AGM and look forward to Montreal in 2014Thanks again to Dave O'Brien for most of the photos. See more athttp://jasnawi.org/

Published on October 23, 2013 00:30

October 21, 2013

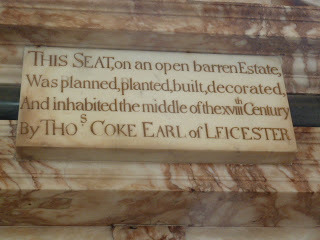

Victoria at Holkham Hall, Part Two

My first post on Holkham Hall told you about my visit to the great mansion, but a trip to Norfolk to see the Coke estates involves more than the Hall. There is a wonderful hotel on the grounds, with the very appealing name of The Victoria Inn. Click here. Of course, I could not resist.

Entrance to the Victoria Inn

Entrance to the Victoria Inn

On the evening after my visit to nearby Houghton Hall with the still limping hubby Ed, we met our trusty taxi driver who took us to the Victoria Inn for our long-reserved two-night stay. The Inn is part of the Holkham Estate, officially in Wells-by-the-Sea.

Victoria Inn from the road

Victoria Inn from the road

When we went into the dining room, we found that most of the other residents had spent hours on the beach, sandy sun-burned, and in the case of the children, all tired from an exciting treat of a day. You will remember, July was an unusually warm month in England.

Ancient Antlers at The Victoria Lounge

Ancient Antlers at The Victoria Lounge

The cuisine was excellent, local specialties for the most part. After dinner, despite his aching foot, we took a few turns around the quaint village, and investigated the local wine store which also carried a Norfolk-distilled English Whiskey.

Holkham Village

Holkham Village

The next morning, deferring to Ed's painful foot, we decided against a walk on the beach, and accepted the kind offer of a young Inn employee to drive us up to the house. The Victoria is at the beginning of the driveway, but it is almost a mile to reach the mansion. We were most appreciative, especially when he agreed to return for us later in the afternoon. Norfolk people are the BEST!!!

The House did not open for an hour or two, so we toured the Bygones Museum, in the outbuildings and stables near the Hall.

The Museum is an eclectic collection of objects from long ago and the recent past. Ed, former TV journalist and anchorman, enjoyed this bulky old TV camera. How well we remember it, now replaced with smaller digital HD descendants.

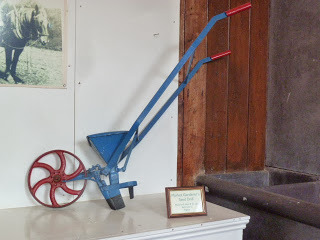

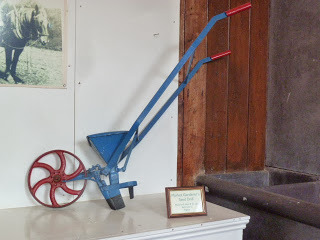

Seed Drill Many of the displays related to Coke of Norfolk's agricultural achievements. He was a great advocate of improvements in land, draining, fertilizing, and renewing the soil. Crop rotation was advocated, with a four year repeating cycle of planting root crops such as turnips, barley or oats the next year, then clover and grass for grazing and natural fertilization, and wheat in the fourth year, after which the cycle begins again.

Seed Drill Many of the displays related to Coke of Norfolk's agricultural achievements. He was a great advocate of improvements in land, draining, fertilizing, and renewing the soil. Crop rotation was advocated, with a four year repeating cycle of planting root crops such as turnips, barley or oats the next year, then clover and grass for grazing and natural fertilization, and wheat in the fourth year, after which the cycle begins again.

Mantrap

Mantrap

The less accommodating side of estate life is represented by the devices used to prevent or catch poachers. The deer in the park, the birds in the bush, and the fish in the streams were carefully cultivated and reserved for the use of the estate owners.

Dairy implements The dairy was an important supplier of milk, cream, butter and cheese from the estate herds.

Dairy implements The dairy was an important supplier of milk, cream, butter and cheese from the estate herds.

hand-pumped fire engine To protect the hundreds of people (and animals) who lived and worked on the estate, many dealing with open fires, it was necessary to have fire-fighting equipment ready to use.

hand-pumped fire engine To protect the hundreds of people (and animals) who lived and worked on the estate, many dealing with open fires, it was necessary to have fire-fighting equipment ready to use.

From horse-drawn carriages to a Rolls Royce, the museum was filled with vehicles of all sorts. After a little snack at the lovely tea ship on the premises, we decided to ride (on a small electric bus) to the walled garden, where restoration of the glass-houses and the flower beds is underway

From horse-drawn carriages to a Rolls Royce, the museum was filled with vehicles of all sorts. After a little snack at the lovely tea ship on the premises, we decided to ride (on a small electric bus) to the walled garden, where restoration of the glass-houses and the flower beds is underway

The lake

The lake  The ice house On the way, we passed acres of lawn, a large lake, and many outbuildings. The renewal of the 6.5- acre walled garden is a relatively new project, expected to be finished in the next year or two.

The ice house On the way, we passed acres of lawn, a large lake, and many outbuildings. The renewal of the 6.5- acre walled garden is a relatively new project, expected to be finished in the next year or two.

I simply cannot resist photographing the roses.

I simply cannot resist photographing the roses.

Ed spent most of his time in the garden sitting on a convenient bench. I must say he was not up for the game of cricket on the lawn either. Not that we know the rules, but it certainly looked like the proper thing to do on a Sunday afternoon in Norfolk. The following day we returned to London and I will relate those adventures soon. Would it tempt you if I hinted that I was about to visit the British Library?

Ed spent most of his time in the garden sitting on a convenient bench. I must say he was not up for the game of cricket on the lawn either. Not that we know the rules, but it certainly looked like the proper thing to do on a Sunday afternoon in Norfolk. The following day we returned to London and I will relate those adventures soon. Would it tempt you if I hinted that I was about to visit the British Library?

Entrance to the Victoria Inn

Entrance to the Victoria InnOn the evening after my visit to nearby Houghton Hall with the still limping hubby Ed, we met our trusty taxi driver who took us to the Victoria Inn for our long-reserved two-night stay. The Inn is part of the Holkham Estate, officially in Wells-by-the-Sea.

Victoria Inn from the road

Victoria Inn from the roadWhen we went into the dining room, we found that most of the other residents had spent hours on the beach, sandy sun-burned, and in the case of the children, all tired from an exciting treat of a day. You will remember, July was an unusually warm month in England.

Ancient Antlers at The Victoria Lounge

Ancient Antlers at The Victoria LoungeThe cuisine was excellent, local specialties for the most part. After dinner, despite his aching foot, we took a few turns around the quaint village, and investigated the local wine store which also carried a Norfolk-distilled English Whiskey.

Holkham Village

Holkham VillageThe next morning, deferring to Ed's painful foot, we decided against a walk on the beach, and accepted the kind offer of a young Inn employee to drive us up to the house. The Victoria is at the beginning of the driveway, but it is almost a mile to reach the mansion. We were most appreciative, especially when he agreed to return for us later in the afternoon. Norfolk people are the BEST!!!

The House did not open for an hour or two, so we toured the Bygones Museum, in the outbuildings and stables near the Hall.

The Museum is an eclectic collection of objects from long ago and the recent past. Ed, former TV journalist and anchorman, enjoyed this bulky old TV camera. How well we remember it, now replaced with smaller digital HD descendants.

Seed Drill Many of the displays related to Coke of Norfolk's agricultural achievements. He was a great advocate of improvements in land, draining, fertilizing, and renewing the soil. Crop rotation was advocated, with a four year repeating cycle of planting root crops such as turnips, barley or oats the next year, then clover and grass for grazing and natural fertilization, and wheat in the fourth year, after which the cycle begins again.

Seed Drill Many of the displays related to Coke of Norfolk's agricultural achievements. He was a great advocate of improvements in land, draining, fertilizing, and renewing the soil. Crop rotation was advocated, with a four year repeating cycle of planting root crops such as turnips, barley or oats the next year, then clover and grass for grazing and natural fertilization, and wheat in the fourth year, after which the cycle begins again. Mantrap

MantrapThe less accommodating side of estate life is represented by the devices used to prevent or catch poachers. The deer in the park, the birds in the bush, and the fish in the streams were carefully cultivated and reserved for the use of the estate owners.

Dairy implements The dairy was an important supplier of milk, cream, butter and cheese from the estate herds.

Dairy implements The dairy was an important supplier of milk, cream, butter and cheese from the estate herds.

hand-pumped fire engine To protect the hundreds of people (and animals) who lived and worked on the estate, many dealing with open fires, it was necessary to have fire-fighting equipment ready to use.

hand-pumped fire engine To protect the hundreds of people (and animals) who lived and worked on the estate, many dealing with open fires, it was necessary to have fire-fighting equipment ready to use.

From horse-drawn carriages to a Rolls Royce, the museum was filled with vehicles of all sorts. After a little snack at the lovely tea ship on the premises, we decided to ride (on a small electric bus) to the walled garden, where restoration of the glass-houses and the flower beds is underway

From horse-drawn carriages to a Rolls Royce, the museum was filled with vehicles of all sorts. After a little snack at the lovely tea ship on the premises, we decided to ride (on a small electric bus) to the walled garden, where restoration of the glass-houses and the flower beds is underway

The lake

The lake  The ice house On the way, we passed acres of lawn, a large lake, and many outbuildings. The renewal of the 6.5- acre walled garden is a relatively new project, expected to be finished in the next year or two.

The ice house On the way, we passed acres of lawn, a large lake, and many outbuildings. The renewal of the 6.5- acre walled garden is a relatively new project, expected to be finished in the next year or two.

I simply cannot resist photographing the roses.

I simply cannot resist photographing the roses.

Ed spent most of his time in the garden sitting on a convenient bench. I must say he was not up for the game of cricket on the lawn either. Not that we know the rules, but it certainly looked like the proper thing to do on a Sunday afternoon in Norfolk. The following day we returned to London and I will relate those adventures soon. Would it tempt you if I hinted that I was about to visit the British Library?

Ed spent most of his time in the garden sitting on a convenient bench. I must say he was not up for the game of cricket on the lawn either. Not that we know the rules, but it certainly looked like the proper thing to do on a Sunday afternoon in Norfolk. The following day we returned to London and I will relate those adventures soon. Would it tempt you if I hinted that I was about to visit the British Library?

Published on October 21, 2013 00:30

October 18, 2013

Visit Basildon Park with Kristine and Victoria...September 2014

We are busy investigating every aspect and all the details of our upcoming tour -- which we hope YOU will join! The details are here. www.wellingtontour.blogspot.com Victoria here, remembering her previous visit to Basildon Park and reprising a blog post from December, 2010 . . . And while you read it, think about how it will feel as you approach the great house...enter the halls and view the sumptuous rooms. You will love every moment of it...and especially the fascinating story of the couple who turned it from a sad wreck of a place into a brilliant National Trust stately home.

from Sunday, December 26, 2010:Basildon Park Rebirths

Basildon Park is in Berkshire overlooking the lovely Thames Valley, built in the 1770's in the strict Palladian style by architect John Carr of York.

Basildon Park is in Berkshire overlooking the lovely Thames Valley, built in the 1770's in the strict Palladian style by architect John Carr of York.  Basildon Park was abandoned about 1910 and stripped of its furnishings even including flooring, fireplace surrounds and woodwork. It was used to house troops or prisoners in both world wars. Some rooms were removed and reconstructed in the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in New York City (ballroom, below).

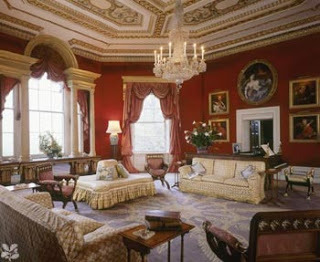

Basildon Park was abandoned about 1910 and stripped of its furnishings even including flooring, fireplace surrounds and woodwork. It was used to house troops or prisoners in both world wars. Some rooms were removed and reconstructed in the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in New York City (ballroom, below). Basildon Park stood mostly empty and deteriorating until 1952 when Lord and Lady Iliffe, a newspaper tycoon and his wife, rescued the house. Lady Iliffe writes, "To say it was derelict is hardly good enough: no window was left intact, and most were repaired with cardboard or plywood; there was a large puddle on the Library floor, coming from the bedroom above, where a fire had just been stopped in time; walls were covered with signatures and graffiti from various occupants….It was appallingly cold and damp. And yet, there was still an atmosphere of former elegance, and a feeling of great solidity. Carr's house was still there, damaged but basically unchanged."

Basildon Park stood mostly empty and deteriorating until 1952 when Lord and Lady Iliffe, a newspaper tycoon and his wife, rescued the house. Lady Iliffe writes, "To say it was derelict is hardly good enough: no window was left intact, and most were repaired with cardboard or plywood; there was a large puddle on the Library floor, coming from the bedroom above, where a fire had just been stopped in time; walls were covered with signatures and graffiti from various occupants….It was appallingly cold and damp. And yet, there was still an atmosphere of former elegance, and a feeling of great solidity. Carr's house was still there, damaged but basically unchanged." Views of the outside show the Bath stone construction. The Palladian window in the Garden Front is in the Octagon Room.

Views of the outside show the Bath stone construction. The Palladian window in the Garden Front is in the Octagon Room.  The Iliffes were fortunate enough to find genuine Carr fireplaces and woodwork removed from other houses, mostly in Yorkshire. Carr employed meticulous craftsmen and used standard measurements so that the pieces were virtually interchangeable.

The Iliffes were fortunate enough to find genuine Carr fireplaces and woodwork removed from other houses, mostly in Yorkshire. Carr employed meticulous craftsmen and used standard measurements so that the pieces were virtually interchangeable.  Again, Lady Iliffe: "Carr was such a precise architect that his mahogany doors from Panton (in Lincolnshire) fitted exactly in the sockets of the missing Basildon ones." Thus Basildon is both authentic and a recreation in one.

Again, Lady Iliffe: "Carr was such a precise architect that his mahogany doors from Panton (in Lincolnshire) fitted exactly in the sockets of the missing Basildon ones." Thus Basildon is both authentic and a recreation in one.

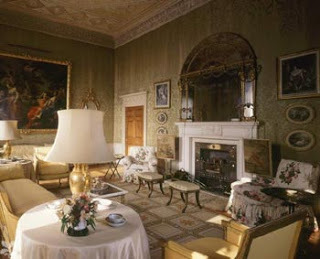

Lady Iliffe collaborated with leading designers of the English Country House style of decorating to fit out the house with a combination of antiques and contemporary pieces, including the inevitable floral chintzes that simply drip with that country house charm. Right, the Octagon Room interior.

Upstairs the generously sized rooms were adapted to alternating bedrooms and huge bathrooms. It is a bit of a shock to see one of the perfectly proportioned rooms with its decorative plaster ceiling and elaborate woodwork and marble fireplace decked out with nothing more than the finest 1950's plumbing fixtures.

Upstairs the generously sized rooms were adapted to alternating bedrooms and huge bathrooms. It is a bit of a shock to see one of the perfectly proportioned rooms with its decorative plaster ceiling and elaborate woodwork and marble fireplace decked out with nothing more than the finest 1950's plumbing fixtures. Basildon Park was built between 1776 and 1782 by Sir Francis Sykes, created a baronet in 1781. His roots were in Yorkshire and he chose Carr of York to build his house, a classical Palladian villa with a main block of rooms joined to pavilions on either side. The Sykes fortune was made during his service in India. Right is the view of the countryside.