Kristine Hughes's Blog, page 74

June 22, 2015

SIR WALTER SCOTT AT WATERLOO

This post was originally posted here on June 15, 2011

Sir Walter Scott

Sir Walter ScottFrom Memoirs of the Life of Sir Walter Scott by John Gibson Lockhart (1838)

I found the letter in question preserved among Scott's papers, I perused it with a peculiar interest; and I now venture, with the writer's permission, to present it to the reader. It was addressed by Sir Charles Bell to his brother, an eminent barrister in Edinburgh, who transmitted it to Scott. "When I read it," said he, "it set me on fire." The marriage of Miss Maclean Clephane of Torloisk with the Earl of Compton (now Marquis of Northampton), which took place on the 24th of July, was in fact the only cause why he did not leave Scotland instantly; for that dear young friend had chosen Scott for her guardian, and on him accordingly devolved the chief care of the arrangements on this occasion. The extract sent to him by Mr George Joseph Bell is as follows:—

"Brussels, 2d July, 1815.

"This country, the finest in the world, has been of late quite out of our minds. I did not, in any degree, anticipate the pleasure I should enjoy, the admiration forced from me, on coming into one of these antique towns, or in journeying through this rich garden. Can you recollect the time when there were gentlemen meeting at the Cross of Edinburgh, or those whom we thought such? They are all collected here. You see the very men, with their scraggy necks sticking out of the collars of their old-fashioned square-skirted coats— their canes—their cocked-hats; and, when they meet, the formal bow, the hat off to the ground, and the powder flying in the wind. I could divert you with the odd resemblances of the Scottish faces among- the peasants, too—but I noted them at the time- with my pencil, and I write to you only of things that you won't find in my pocket-book.

"I have just returned from seeing the French wounded received in their hospital; and could you see them laid out naked, or almost so—100 in a row of low beds on the ground—though wounded, exhausted, beaten, you would still conclude with me that these were men capable of marching unopposed from the west of Europe to the east of Asia. Strong, thickset, hardy veterans, brave spirits and unsubdued, as they cast their wild glance upon you,—their black eyes and brown cheeks finely contrasted with the fresh sheets,—you would much admire their capacity of adaptation. These fellows are brought from the field after lying many days on the ground; many dying—many in the agony—many miserably racked with pain and spasms; and the next mimicks his fellow, and gives it a tune,—Aha, vous chantez bien! How they are wounded you will see in my notes. But I must not have you to lose the present impression on me of the formidable nature of these fellows as exemplars of the breed in France. It is a forced praise; for from all I have seen, and all I have heard of their fierceness, cruelty, and bloodthirstiness, I cannot convey to you my detestation of this race of trained banditti. By what means they are to be kept in subjection until other habits come upon them, I know not; but I am convinced that these men cannot be left to the bent of their propensities.

"This superb city is now ornamented with the finest groupes of armed men that the most romantic fancy could dream of. I was struck with the words of a friend —E.: 'I saw,' said he, 'that man returning from the field on the 16th.'—(This was a Brunswicker of the Black or Death Hussars.)—' He was wounded, and had had his arm amputated on the field. He was among the first that came in. He rode straight and stark upon his horse—the bloody clouts about his stump—pale as death, but upright, with a stern, fixed expression of feature, as if loth to lose his revenge.' These troops are very remarkable in their fine military appearance; their dark and ominous dress sets off to advantage their strong, manly, northern features and white mustachios; and there is something more than commonly impressive about the whole effect."This is the second Sunday after the battle, and many are not yet dressed. There are 20,000 wounded in this town, besides those in the hospitals, and the many in the other towns ;—only 3000 prisoners; 80,000, they say, killed and wounded on both sides."

I think it not wonderful that this extract should have set Scott's imagination effectually on fire; that he should have grasped at the idea of seeing probably the last shadows of real warfare that his own age would afford; or that some parts of the great surgeon's simple phraseology are reproduced, almost verbatim, in the first of "Paul's Letters to his Kinsfolk."

. . . . . At Brussels, Scott found the small English garrison left there in command of Major-General Sir Frederick Adam, the son of his highly valued friend, the present Lord Chief Commissioner of the Jury Court in Scotland. Sir Frederick had been wounded at Waterloo, and could not as yet mount on horseback ; but one of his aides-de-camp, Captain Campbell, escorted Seott and his party to the field of battle, on which occasion they were also accompanied by another old acquaintance of his, Major Pryse Gordon, who being then on halfpay, happened to be domesticated with his family at Brussels. Major Gordon has since published two lively volumes of " Personal Memoirs;" and Gala bears witness to the fidelity of certain reminiscences of Scott at Brussels and Waterloo, which occupy one of the chapters of this work. I shall, therefore, extract the passage.

Louis-Victor Baillot, last French veteran of Waterloo"Sir Walter Scott accepted my services to conduct him to Waterloo: the General's aide-de-camp was also of the party. He made no secret of his having undertaken to write something on the battle; and perhaps he took the greater interest on this account in every thing that he saw. Besides, he had never seen the field of such a conflict; and never having been before on the Continent, it was all new to his comprehensive mind. The day was beautiful; and I had the precaution to send out a couple of saddle-horses, that he might not be fatigued in walking over the fields, which had been recently ploughed up. In our rounds we fell in with Monsieur de Costar, with whom he got into conversation. This man had attracted so much notice by his pretended story of being about the person of Napoleon, that he was of too much importance to be passed by: I did not, indeed, know as much of this fellow's charlatanism at that time as afterwards, when I saw him confronted with a blacksmith of La Belle Alliance, who had been his companion in a hiding-place ten miles from the field during the whole day; a fact which he could not deny. But he had got up a tale so plausible and so profitable, that he could afford to bestow hush-money on the companion of his flight, so that the imposition was but little known; and strangers continued to be gulled. He had picked up a good deal of information about the positions and details of the battle; and being naturally a sagacious Wallon, and speaking French pretty fluently, he became the favourite cicerone, and every lie he told was taken for gospel. Year after year, until his death in 1824, he continued his popularity, and raised the price of his rounds from a couple of francs to five; besides as much for the hire of a horse, his own property; for he pretended that the fatigue of walking so many hours was beyond his powers. It has been said that in this way he realized every summer a couple of hundred Napoleons.

Louis-Victor Baillot, last French veteran of Waterloo"Sir Walter Scott accepted my services to conduct him to Waterloo: the General's aide-de-camp was also of the party. He made no secret of his having undertaken to write something on the battle; and perhaps he took the greater interest on this account in every thing that he saw. Besides, he had never seen the field of such a conflict; and never having been before on the Continent, it was all new to his comprehensive mind. The day was beautiful; and I had the precaution to send out a couple of saddle-horses, that he might not be fatigued in walking over the fields, which had been recently ploughed up. In our rounds we fell in with Monsieur de Costar, with whom he got into conversation. This man had attracted so much notice by his pretended story of being about the person of Napoleon, that he was of too much importance to be passed by: I did not, indeed, know as much of this fellow's charlatanism at that time as afterwards, when I saw him confronted with a blacksmith of La Belle Alliance, who had been his companion in a hiding-place ten miles from the field during the whole day; a fact which he could not deny. But he had got up a tale so plausible and so profitable, that he could afford to bestow hush-money on the companion of his flight, so that the imposition was but little known; and strangers continued to be gulled. He had picked up a good deal of information about the positions and details of the battle; and being naturally a sagacious Wallon, and speaking French pretty fluently, he became the favourite cicerone, and every lie he told was taken for gospel. Year after year, until his death in 1824, he continued his popularity, and raised the price of his rounds from a couple of francs to five; besides as much for the hire of a horse, his own property; for he pretended that the fatigue of walking so many hours was beyond his powers. It has been said that in this way he realized every summer a couple of hundred Napoleons."When Sir Walter had examined every point of defence and attack, we adjourned to the 'Original Duke of Wellington' at Waterloo, to lunch after the fatigues of the ride. Here he had a crowded levee of peasants, and collected a great many trophies, from cuirasses down to buttons and bullets. He picked up himself many little relics, and was fortunate in purchasing a grand cross of the legion of honour. But the most precious memorial was presented to him by my wife—a French soldier's book, well stained with blood, and containing some songs popular in the French army, which he found so interesting that he introduced versions of them in his 'Paul's Letters;' of which he did me the honour to send me a copy, with a letter, saying, 'that he considered my wife's gift as the most valuable of all his Waterloo relics.'

Published on June 22, 2015 00:39

June 19, 2015

THE HON. KATHERINE ARDEN'S ACCOUNT OF WATERLOO

This post was originally published here on June 11, 2011

The following letter was written by the Hon. Katherine Arden*, daughter of the first Lord Alvanley (Richard, 1744-1804) and published in the Cornhill Magazine in 1891. With her mother and sister, she was resident in Brussels at the time of the great battle, and took an active part in nursing the wounded. The letter is addressed to her aunt, Miss Bootle Wilbraham, afterwards, Mrs. Barnes. It is franked from Windsor to Ormskirk in Lancashire by Miss Arden’s uncle, Mr. E. Bootle Wilbraham (afterwards Lord Skelmersdale), July 17, 1815.

*Sister of William Arden, 2nd Lord Alvaney (1789-1849) , famous dandy who squandered his fortune and died unmarried; the title went to their younger brother.

Brussels, Sunday 9th (July)

My Dearest Aunt, I can assure you most truly that I did not require reminding, to fulfill the promise I made you of writing, and every day since our return from Antwerp I have settled for the purpose, but what with visiting the sick, and making bandages and lint, I can assure you my time has been pretty well occupied. As my patients are, thank goodness, most of them now convalescent, I think the best way I can reward my dear Aunt’s patience, is by giving her a long account of our hopes, fears, and feelings from the time the troops were ordered to march down to the present moment. (If you are tired with my long account, remember you expressed a wish in Mama’s letter to hear all our proceedings.)

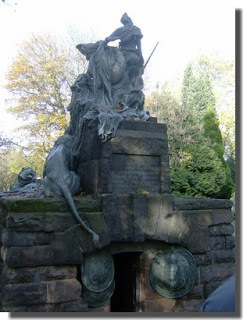

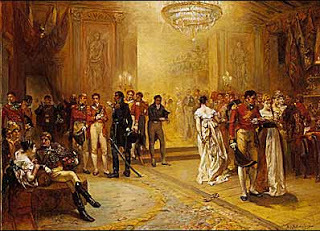

On Thursday the 15th of June, we went to the great ball that the Duchess of Richmond gave, and which we expected to see from Generals down to Ensigns, all the military men, who with their regiments had been for some time quartered from 18 to 30 miles from this town, and consequently so much nearer the frontiers; nor were we disappointed, with the exception of 3 generals, every officer high in the army was to be there seen.

Though for nearly ten weeks we had been daily expecting the arrival of the French troops on the Frontiers, and had rather been wondering at their delay, yet when on our arrival at the ball, we were told that the troops had ordered to march at 3 in the morning, and that every officer must join his regiment by that time, as the French were advancing, you cannot possibly picture to yourself the dismay and consternation that appeared in every face.

Those who had brothers and sons to be engaged, openly gave way to their grief, as the last parting of many took place at this most terrible ball; others (and thank Heaven ranked amongst that number, for in the midst of my greatest fears, I still felt thankfulness, was my prominent feeling that my beloved Dick (her brother) was not here), who had no near relation, yet felt that amongst the many many friends we all had there, it was impossible that all should escape, and that the next time we might hear of them, they might be numbered with the dead; in fact, my dear Aunt, I cannot describe to you my mingled feelings, you will, however, I am sure, understand them, and I feel quite inadequate to express them.

We staid at the ball as short a time as we could but long enough to see express after express arrive to the Duke of Wellington, to hear of Aides de Camp arriving breathless with news, and to see, what was much more extraordiniary than all, the Duke’s equanimity a little discomposed. We took a mournful farewell of some of our best friends, and returned home to anything but repose.

The morning (Friday June 16) dawned most lovelily, and before seven o’clock we had seen 12,000 Brunswickers, Scotch, and English pass before our windows, of whom one third before night were mingled with the dust. Mama took a farewell of the Duke as he passed by, but Fanny and myself, at last wearied out, had before he went, retired to bed. The first person that we saw in the morning brought us the news, that the advanced guard of the French had in the night come on as far as Genappe, 18 miles off, and had had several skirmishes with the Prussians.

This intelligence, as you may suppose, did not tend to compose us, but still everything went on in quiet calmness, when (Gracious heavens, never never shall I forget it), at three o’clock a loud cannonading commenced, which upon the ramparts was heard nearly as plain as we do the Tower guns in London; it went on without intermission till 8 o’clock, when it was thought to appear more distant, and therefore hopes were entertained that the French had retreated; nothing certain was known, but it was reported that the Prussians had been principally attacked, and were rather giving way when the Highlanders and the regiments who had marched from here in the morning joined them, and compleately repulsed the French.

So far the news was good, but still the English had fought, and what our loss was, nobody knew; however, we bore up pretty well till above twelve o’clock, a gentleman (Mr. Leigh, of Lyme in Cheshire) came from off the field of battle, where he had been looking on, with the intelligence that there had been a dreadful battle, the Duke of Brunswick was killed, and that the Brigade of 1st Guards and the Highlanders were literally cut to pieces. I will not attempt to say what we felt, for it would be quite vain.

I must only tell you that that Regiment of Guards contained all our greatest friends, independent of our having to regret them as Englishmen. The next morning by six o’clock, Saturday 17th numbers of Belgians and others of our brave Allies came flying into the town, with the report that the French were at their heels, but this intelligence occasioned but a temporary fright, as a bulletin was published officially saying that we had gained a great victory, and the French were retreating (neither of which was true). About ten o’clock the real horrors of war began to appear, and though we were spared hearing cannonading, yet the sights that we saw were infinitely more frightful than anything we had heard the day before. I mean the sight of wounded. I must tell you before I proceed, that Sir James Gambier (the Consul General to the Paysbas, who is the best man that ever was) came to us about eight o’clock, and told us that there really had been a severe engagement, but that we had the advantage, that though the Guards had suffered most dreadfully, yet that their loss was not quite so great as had been reported, but that the Highlanders were literally nearly annihilated, after having performed prodigies of valor; and very good proof had we how dreadfully they had suffered, by the numbers who were brought in here, literally cut to pieces. Our house being unfortunately near the gate where they were brought in, most of them passed our door; their wounds were none of them drest, and barely bound up, the wagons were piled up to a degree almost incredible, and numbers for whom there was no room, were obliged, faint and bleeding, to follow on foot; their heads being what had most suffered, having been engaged with cavalry, were often so much bound up, that they were unable to see, and therefore held by the wagons in order to know their road. Everybody, as you may suppose, pressed forward, anxious to be of some service to the poor wounded Hero’s but the people had orders that those who could go on should proceed to Antwerp, to make room for those who were to follow (dreadful idea), and therefore we could be of no further use to them than giving them refreshments as they passed.

In the middle of the day, we heard further particulars of the last night’s battle, and if all danger had been removed far from us, which Heaven knows was very far from being so, we still should have felt nervous at the danger that had nearly befallen us. Conceive it having been run so near, that the French were within ten minutes of getting possession of the road to Brussels, which had they once gained, in all probability they would have reached the town in three hours.

Providence, however, ordered it otherwise, and the Guards, who had marched from Enghien 27 miles off, arrived at the lucky moment, and got possession of the road. They were shortly afterwards joined by the Highlanders, who some of them fought with their knapsacks on, having marched 20 miles and accordingly were enabled to keep their ground against the French.

The conduct of the English soldiers on that day was perfect, and would have been sufficient to have immortalized them, without the addition of the Sunday’s battle, after which the Duke of Wellington said he should never feel sufficiently grateful to the Guards for their conduct on both days, which from the Duke means more than it would from anybody else.

Our Hero, Wellington, who had been deceived with the intelligence given him (for it is said that Bony had bribed most of his outposts), and had no idea that the French were so near, nor advancing in such force, was so distressed when he discovered the truth, that as usual totally regardless of his personal safety, he was exposing himself in the most dreadful way (I am speaking of the Friday’s business at Quatre Bras, so named from four roads meeting), and already a party of French horse, having marked him out, were rushing on him with the greatest violence, when the Highlanders, who saw his danger, and it is said he never was in so great before, rushed between him and the French, and with the lives of hundreds, saved his still more precious one. On coming off the field, the Duke told some whom he met with, that their conduct had been noble and he should make a good report of them; of the 92nd regiment, out of seven hundred men, but one hundred and fifty remain to share the glory.

But to resume my narrative. We remained the whole of Saturday, in great suspense, to know that the armies were about, and whether the French were really retreating as had been reported; about four o’clock in the day, we were dreadfully undeceived, by being told from very good authority that instead of the enemy it was Lord Wellington who had retreated, and who with his whole army were within ten miles of the town; the reason given for his doing so, was that the Prussians had been attacked on the Friday evening whilst they were quietly cooking, and that having lost a tremendous number of men, Blucher had judged it prudent to retire, which being the case, he had left Lord Wellington’s left flank so exposed, that it was impossible for him to remain where he was, and that he had therefore retreated to a strong position near Waterloo, whilst our cavalry were engaged in playing before them, to hide, as much as possible, their retreat from the French.

copyright 1st Artgallery.com

copyright 1st Artgallery.com

It was likewise added, that it was to be hoped that the Prussians would rejoin the English, as at that present time, the armies were near nine miles asunder, and that orders had been issued by the Duke for all baggage to be sent from the army through this town, and for the wounded, if possible, to be moved from it. All this looked so like retreating on the town, that we were told we must have horses ready, and everything prepared to go at an instant’s notice, which accordingly we commenced doing, and from that hour 4 o’clock till eight in the morning (Sunday June 18) when we were fairly in Antwerp, were, I hope, the most harassing 16 hours I ever passed, or ever shall.

From that time the baggage wagons passed in such quick succession, that they formed cavalcades through the town, as not only those who were ordered to go, but those who desired to stay with the army, passed through, a general panic having seized all the officers’ servants, by which means many have lost all they had, and everybody is minus something.

About every half-hour a man was heard scampering down the street calling out that the French were coming; some, indeed said they were at the gates, and though we knew that that could not be true, yet it was impossible to know how much foundation there was for saying so. About seven o’clock (Saturday June 17) our friend Sir James Gambier arrived to say that he hoped our things were nearly packed up, as though it was not necessary to go immediately, yet that he begged our things might be put to the carriage as we might be obliged to start at an instant’s notice, for it was known that the Prussians were not joined, and if Buonaparte were to attack that night, there was no knowing what the event might be. (We have since heard, that if he had done so, the tide of affairs would in all probability have turned completely for him instead of being as it is now).

James Gambier, First Baron Gambier

James Gambier, First Baron Gambier

(1756–1833).

After Sir James went, we went out to see what our friends intended doing; we found that some were gone, others going, and all were prepared for the worst. We accordingly agreed, that at the time Lady Charlotte Greville went, we would accompany her, as everybody told us if we waited for the worst we could never get away; and as we knew for certain that Buonaparte had promised his soldiers after he had drawn 20,000,000 francs from the town, that they should have three days pillage of it, which, as the enraged French soldiery are not the most kind hearted possible, and as the English could expect no mercy for them, we though it madness to put ourselves in such danger, and accordingly everything was got ready. To increase the horror and noise, about ten o’clock, a most horrible storm of wind and rain came on, which lasted without intermission till three o’clock, when the wind abated, but the rain continued at intervals, the whole of Sunday, to which the whole of our poor soldiers were exposed with the additional hardship of having very little to eat, as they had been so continually changing their place for the last two days, that the officers have since told us, that for nearly eight and forty hours, they had barely two pounds of bread to eat; luckily, the Sunday morning, after the dreadful night they passed, the common men had a double supply of spirits, which enabled them to fight as they did.

The baggage wagons and fuyards [fugitives] continued passing, without intermission, and what with being deafened with the noise, and worn out with anxiety, we were in a terrible state of fatigue, when at half past two (Sunday the 18th) Lady Charlotte sent to say the Mayor of the town had sent to advise all the English to quit the town, and that she was waiting for us. We accordingly joined her, and though we were very much impeded by the road being blocked up with wagons in which were numbers of the wounded, lying exposed to all the inclemency of the weather, and were several times in danger of being overturned, yet providentially we arrived safe at Antwerp about eight o’clock (Note: The distance from Brussels to Antwerp by road is about twenty-seven miles). We found the greatest difficulty in getting a hole to put our heads in, but at last succeeded: Lady Charlotte proceeded on the Hague immediately, but we remained to wait the event. We were told by many people that the rain would prevent them fighting, which gave us ease for the time, and though we spent the day in great suspense, yet we were saved the dreadful indescribable anxiety of those who remained here; never can I be sufficiently thankful that we left this place. For the first time for three nights, Fanny and myself were enabled to sleep, and the next morning, Monday (the 19th) we were awoke, with the delightful news, that a decisive victory had been obtained, and that the French were retreating in disorder. The account of killed and wounded which we then heard made us shudder; how much more dreadful was it, when the whole list was made out! There are 724 English officers killed and wounded, and nearly 11,000 common men, without Hanoverians.

The conduct of the English infantry in the battle of Sunday was something so extraordinary, that Cambaceres, Buonaparte’s A.D.C. who was taken, said Buonaparte himself had said that it was useless to fight against such troops, nothing could make them give way. They were formed into hollow squares, upon which the French cavalry, particularly the Cuirassiers, who wear complete armour, poured down, but without any avail, not one of their squares were ever broken, though perhaps from being six or eight lines deep, they came at last to only one.

Hougemont

Hougemont

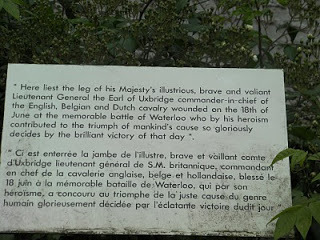

There is a little wood and a farm-house in the midst of the field of battle, which is called Hougemont, and which it was necessary for the English to maintain possession of: 500 of the Guards under Lord Saltoun and Co. Macdonnell were put into it, to defend it, and though they were attacked by above 10,000 French, and the Farm-house was set fire to, and burnt to the ground, yet our Invincible countrymen still maintained possession of it, and finally repulsed the enemy. Do not you feel, while you hear these accounts, that your national pride increases every instant, and that you feel more thankful than ever that you are English born and bred? I have that sort of enthusiasm about me, that I almost feel inclined to shake hands with every soldier I meet walking in the streets. The light cavalry, I am sorry to say, for the first time in their lives, did not behave like Englishmen; the 7th Hussars and 23rd dragoons refused to advance when they were ordered, and poor Lord Uxbridge, who is as brave as a lion, and doats upon his regiment (the 7th) went up to Lord Wellington in the midst of the engagement, and said in the bitterness of his heart, My cavalry have deserted me! The heavy dragoons behaved admirably, and the horse Guards and Blue’s who though they have been in Spain, were never before personally engaged, performed prodigies.—The Duke of Wellington has since said, that he never exerted himself in his life as he did on that day, but that notwithstanding, the battle was lost three times; he exposed himself in every part of the line, often threw himself into the squares when they were about to be attacked, and did what it is said he never had done before, talked to the soldiers, and told them to stand firm; in fact, I believe without his having behaved as he did, the English would never have stood their ground so long, till the arrival of 30,000 fresh Prussians under Bulow finished the day, for as soon as the French saw them, they ran.

La Belle Alliance

La Belle Alliance

The conduct of the French cavalry is represented as having been most beautiful, and nothing could have withstood them but our soldiers. The day after the battle, when the Duke had leisure to consider the loss he had sustained in both officers and men, he was most deeply affected, and Mrs. Pole, who breakfasted with him said the tears were running down upon his plate the whole time. How much more noble the Hero appears when possessed of so much feeling!

You ask how we like the Duke, and whether he is haughty? To men, I believe he is, very often, but all his personal staff are extremely attached to him, and towards women his manners excessively agreeable and very gallant; we like him vastly. We went a few days since to see the field of battle, and everything offensive was removed, a most interesting visit; we went with an A.D.C. of Gen. Cooke, (who poor man, the General, has lost his arm), and who explained to us all about the battle.—I am quite ashamed, my dear Aunt, to think how much I have written; pray forgive me.

The following letter was written by the Hon. Katherine Arden*, daughter of the first Lord Alvanley (Richard, 1744-1804) and published in the Cornhill Magazine in 1891. With her mother and sister, she was resident in Brussels at the time of the great battle, and took an active part in nursing the wounded. The letter is addressed to her aunt, Miss Bootle Wilbraham, afterwards, Mrs. Barnes. It is franked from Windsor to Ormskirk in Lancashire by Miss Arden’s uncle, Mr. E. Bootle Wilbraham (afterwards Lord Skelmersdale), July 17, 1815.

*Sister of William Arden, 2nd Lord Alvaney (1789-1849) , famous dandy who squandered his fortune and died unmarried; the title went to their younger brother.

Brussels, Sunday 9th (July)

My Dearest Aunt, I can assure you most truly that I did not require reminding, to fulfill the promise I made you of writing, and every day since our return from Antwerp I have settled for the purpose, but what with visiting the sick, and making bandages and lint, I can assure you my time has been pretty well occupied. As my patients are, thank goodness, most of them now convalescent, I think the best way I can reward my dear Aunt’s patience, is by giving her a long account of our hopes, fears, and feelings from the time the troops were ordered to march down to the present moment. (If you are tired with my long account, remember you expressed a wish in Mama’s letter to hear all our proceedings.)

On Thursday the 15th of June, we went to the great ball that the Duchess of Richmond gave, and which we expected to see from Generals down to Ensigns, all the military men, who with their regiments had been for some time quartered from 18 to 30 miles from this town, and consequently so much nearer the frontiers; nor were we disappointed, with the exception of 3 generals, every officer high in the army was to be there seen.

Though for nearly ten weeks we had been daily expecting the arrival of the French troops on the Frontiers, and had rather been wondering at their delay, yet when on our arrival at the ball, we were told that the troops had ordered to march at 3 in the morning, and that every officer must join his regiment by that time, as the French were advancing, you cannot possibly picture to yourself the dismay and consternation that appeared in every face.

Those who had brothers and sons to be engaged, openly gave way to their grief, as the last parting of many took place at this most terrible ball; others (and thank Heaven ranked amongst that number, for in the midst of my greatest fears, I still felt thankfulness, was my prominent feeling that my beloved Dick (her brother) was not here), who had no near relation, yet felt that amongst the many many friends we all had there, it was impossible that all should escape, and that the next time we might hear of them, they might be numbered with the dead; in fact, my dear Aunt, I cannot describe to you my mingled feelings, you will, however, I am sure, understand them, and I feel quite inadequate to express them.

We staid at the ball as short a time as we could but long enough to see express after express arrive to the Duke of Wellington, to hear of Aides de Camp arriving breathless with news, and to see, what was much more extraordiniary than all, the Duke’s equanimity a little discomposed. We took a mournful farewell of some of our best friends, and returned home to anything but repose.

The morning (Friday June 16) dawned most lovelily, and before seven o’clock we had seen 12,000 Brunswickers, Scotch, and English pass before our windows, of whom one third before night were mingled with the dust. Mama took a farewell of the Duke as he passed by, but Fanny and myself, at last wearied out, had before he went, retired to bed. The first person that we saw in the morning brought us the news, that the advanced guard of the French had in the night come on as far as Genappe, 18 miles off, and had had several skirmishes with the Prussians.

This intelligence, as you may suppose, did not tend to compose us, but still everything went on in quiet calmness, when (Gracious heavens, never never shall I forget it), at three o’clock a loud cannonading commenced, which upon the ramparts was heard nearly as plain as we do the Tower guns in London; it went on without intermission till 8 o’clock, when it was thought to appear more distant, and therefore hopes were entertained that the French had retreated; nothing certain was known, but it was reported that the Prussians had been principally attacked, and were rather giving way when the Highlanders and the regiments who had marched from here in the morning joined them, and compleately repulsed the French.

So far the news was good, but still the English had fought, and what our loss was, nobody knew; however, we bore up pretty well till above twelve o’clock, a gentleman (Mr. Leigh, of Lyme in Cheshire) came from off the field of battle, where he had been looking on, with the intelligence that there had been a dreadful battle, the Duke of Brunswick was killed, and that the Brigade of 1st Guards and the Highlanders were literally cut to pieces. I will not attempt to say what we felt, for it would be quite vain.

I must only tell you that that Regiment of Guards contained all our greatest friends, independent of our having to regret them as Englishmen. The next morning by six o’clock, Saturday 17th numbers of Belgians and others of our brave Allies came flying into the town, with the report that the French were at their heels, but this intelligence occasioned but a temporary fright, as a bulletin was published officially saying that we had gained a great victory, and the French were retreating (neither of which was true). About ten o’clock the real horrors of war began to appear, and though we were spared hearing cannonading, yet the sights that we saw were infinitely more frightful than anything we had heard the day before. I mean the sight of wounded. I must tell you before I proceed, that Sir James Gambier (the Consul General to the Paysbas, who is the best man that ever was) came to us about eight o’clock, and told us that there really had been a severe engagement, but that we had the advantage, that though the Guards had suffered most dreadfully, yet that their loss was not quite so great as had been reported, but that the Highlanders were literally nearly annihilated, after having performed prodigies of valor; and very good proof had we how dreadfully they had suffered, by the numbers who were brought in here, literally cut to pieces. Our house being unfortunately near the gate where they were brought in, most of them passed our door; their wounds were none of them drest, and barely bound up, the wagons were piled up to a degree almost incredible, and numbers for whom there was no room, were obliged, faint and bleeding, to follow on foot; their heads being what had most suffered, having been engaged with cavalry, were often so much bound up, that they were unable to see, and therefore held by the wagons in order to know their road. Everybody, as you may suppose, pressed forward, anxious to be of some service to the poor wounded Hero’s but the people had orders that those who could go on should proceed to Antwerp, to make room for those who were to follow (dreadful idea), and therefore we could be of no further use to them than giving them refreshments as they passed.

In the middle of the day, we heard further particulars of the last night’s battle, and if all danger had been removed far from us, which Heaven knows was very far from being so, we still should have felt nervous at the danger that had nearly befallen us. Conceive it having been run so near, that the French were within ten minutes of getting possession of the road to Brussels, which had they once gained, in all probability they would have reached the town in three hours.

Providence, however, ordered it otherwise, and the Guards, who had marched from Enghien 27 miles off, arrived at the lucky moment, and got possession of the road. They were shortly afterwards joined by the Highlanders, who some of them fought with their knapsacks on, having marched 20 miles and accordingly were enabled to keep their ground against the French.

The conduct of the English soldiers on that day was perfect, and would have been sufficient to have immortalized them, without the addition of the Sunday’s battle, after which the Duke of Wellington said he should never feel sufficiently grateful to the Guards for their conduct on both days, which from the Duke means more than it would from anybody else.

Our Hero, Wellington, who had been deceived with the intelligence given him (for it is said that Bony had bribed most of his outposts), and had no idea that the French were so near, nor advancing in such force, was so distressed when he discovered the truth, that as usual totally regardless of his personal safety, he was exposing himself in the most dreadful way (I am speaking of the Friday’s business at Quatre Bras, so named from four roads meeting), and already a party of French horse, having marked him out, were rushing on him with the greatest violence, when the Highlanders, who saw his danger, and it is said he never was in so great before, rushed between him and the French, and with the lives of hundreds, saved his still more precious one. On coming off the field, the Duke told some whom he met with, that their conduct had been noble and he should make a good report of them; of the 92nd regiment, out of seven hundred men, but one hundred and fifty remain to share the glory.

But to resume my narrative. We remained the whole of Saturday, in great suspense, to know that the armies were about, and whether the French were really retreating as had been reported; about four o’clock in the day, we were dreadfully undeceived, by being told from very good authority that instead of the enemy it was Lord Wellington who had retreated, and who with his whole army were within ten miles of the town; the reason given for his doing so, was that the Prussians had been attacked on the Friday evening whilst they were quietly cooking, and that having lost a tremendous number of men, Blucher had judged it prudent to retire, which being the case, he had left Lord Wellington’s left flank so exposed, that it was impossible for him to remain where he was, and that he had therefore retreated to a strong position near Waterloo, whilst our cavalry were engaged in playing before them, to hide, as much as possible, their retreat from the French.

copyright 1st Artgallery.com

copyright 1st Artgallery.comIt was likewise added, that it was to be hoped that the Prussians would rejoin the English, as at that present time, the armies were near nine miles asunder, and that orders had been issued by the Duke for all baggage to be sent from the army through this town, and for the wounded, if possible, to be moved from it. All this looked so like retreating on the town, that we were told we must have horses ready, and everything prepared to go at an instant’s notice, which accordingly we commenced doing, and from that hour 4 o’clock till eight in the morning (Sunday June 18) when we were fairly in Antwerp, were, I hope, the most harassing 16 hours I ever passed, or ever shall.

From that time the baggage wagons passed in such quick succession, that they formed cavalcades through the town, as not only those who were ordered to go, but those who desired to stay with the army, passed through, a general panic having seized all the officers’ servants, by which means many have lost all they had, and everybody is minus something.

About every half-hour a man was heard scampering down the street calling out that the French were coming; some, indeed said they were at the gates, and though we knew that that could not be true, yet it was impossible to know how much foundation there was for saying so. About seven o’clock (Saturday June 17) our friend Sir James Gambier arrived to say that he hoped our things were nearly packed up, as though it was not necessary to go immediately, yet that he begged our things might be put to the carriage as we might be obliged to start at an instant’s notice, for it was known that the Prussians were not joined, and if Buonaparte were to attack that night, there was no knowing what the event might be. (We have since heard, that if he had done so, the tide of affairs would in all probability have turned completely for him instead of being as it is now).

James Gambier, First Baron Gambier

James Gambier, First Baron Gambier (1756–1833).

After Sir James went, we went out to see what our friends intended doing; we found that some were gone, others going, and all were prepared for the worst. We accordingly agreed, that at the time Lady Charlotte Greville went, we would accompany her, as everybody told us if we waited for the worst we could never get away; and as we knew for certain that Buonaparte had promised his soldiers after he had drawn 20,000,000 francs from the town, that they should have three days pillage of it, which, as the enraged French soldiery are not the most kind hearted possible, and as the English could expect no mercy for them, we though it madness to put ourselves in such danger, and accordingly everything was got ready. To increase the horror and noise, about ten o’clock, a most horrible storm of wind and rain came on, which lasted without intermission till three o’clock, when the wind abated, but the rain continued at intervals, the whole of Sunday, to which the whole of our poor soldiers were exposed with the additional hardship of having very little to eat, as they had been so continually changing their place for the last two days, that the officers have since told us, that for nearly eight and forty hours, they had barely two pounds of bread to eat; luckily, the Sunday morning, after the dreadful night they passed, the common men had a double supply of spirits, which enabled them to fight as they did.

The baggage wagons and fuyards [fugitives] continued passing, without intermission, and what with being deafened with the noise, and worn out with anxiety, we were in a terrible state of fatigue, when at half past two (Sunday the 18th) Lady Charlotte sent to say the Mayor of the town had sent to advise all the English to quit the town, and that she was waiting for us. We accordingly joined her, and though we were very much impeded by the road being blocked up with wagons in which were numbers of the wounded, lying exposed to all the inclemency of the weather, and were several times in danger of being overturned, yet providentially we arrived safe at Antwerp about eight o’clock (Note: The distance from Brussels to Antwerp by road is about twenty-seven miles). We found the greatest difficulty in getting a hole to put our heads in, but at last succeeded: Lady Charlotte proceeded on the Hague immediately, but we remained to wait the event. We were told by many people that the rain would prevent them fighting, which gave us ease for the time, and though we spent the day in great suspense, yet we were saved the dreadful indescribable anxiety of those who remained here; never can I be sufficiently thankful that we left this place. For the first time for three nights, Fanny and myself were enabled to sleep, and the next morning, Monday (the 19th) we were awoke, with the delightful news, that a decisive victory had been obtained, and that the French were retreating in disorder. The account of killed and wounded which we then heard made us shudder; how much more dreadful was it, when the whole list was made out! There are 724 English officers killed and wounded, and nearly 11,000 common men, without Hanoverians.

The conduct of the English infantry in the battle of Sunday was something so extraordinary, that Cambaceres, Buonaparte’s A.D.C. who was taken, said Buonaparte himself had said that it was useless to fight against such troops, nothing could make them give way. They were formed into hollow squares, upon which the French cavalry, particularly the Cuirassiers, who wear complete armour, poured down, but without any avail, not one of their squares were ever broken, though perhaps from being six or eight lines deep, they came at last to only one.

Hougemont

HougemontThere is a little wood and a farm-house in the midst of the field of battle, which is called Hougemont, and which it was necessary for the English to maintain possession of: 500 of the Guards under Lord Saltoun and Co. Macdonnell were put into it, to defend it, and though they were attacked by above 10,000 French, and the Farm-house was set fire to, and burnt to the ground, yet our Invincible countrymen still maintained possession of it, and finally repulsed the enemy. Do not you feel, while you hear these accounts, that your national pride increases every instant, and that you feel more thankful than ever that you are English born and bred? I have that sort of enthusiasm about me, that I almost feel inclined to shake hands with every soldier I meet walking in the streets. The light cavalry, I am sorry to say, for the first time in their lives, did not behave like Englishmen; the 7th Hussars and 23rd dragoons refused to advance when they were ordered, and poor Lord Uxbridge, who is as brave as a lion, and doats upon his regiment (the 7th) went up to Lord Wellington in the midst of the engagement, and said in the bitterness of his heart, My cavalry have deserted me! The heavy dragoons behaved admirably, and the horse Guards and Blue’s who though they have been in Spain, were never before personally engaged, performed prodigies.—The Duke of Wellington has since said, that he never exerted himself in his life as he did on that day, but that notwithstanding, the battle was lost three times; he exposed himself in every part of the line, often threw himself into the squares when they were about to be attacked, and did what it is said he never had done before, talked to the soldiers, and told them to stand firm; in fact, I believe without his having behaved as he did, the English would never have stood their ground so long, till the arrival of 30,000 fresh Prussians under Bulow finished the day, for as soon as the French saw them, they ran.

La Belle Alliance

La Belle AllianceThe conduct of the French cavalry is represented as having been most beautiful, and nothing could have withstood them but our soldiers. The day after the battle, when the Duke had leisure to consider the loss he had sustained in both officers and men, he was most deeply affected, and Mrs. Pole, who breakfasted with him said the tears were running down upon his plate the whole time. How much more noble the Hero appears when possessed of so much feeling!

You ask how we like the Duke, and whether he is haughty? To men, I believe he is, very often, but all his personal staff are extremely attached to him, and towards women his manners excessively agreeable and very gallant; we like him vastly. We went a few days since to see the field of battle, and everything offensive was removed, a most interesting visit; we went with an A.D.C. of Gen. Cooke, (who poor man, the General, has lost his arm), and who explained to us all about the battle.—I am quite ashamed, my dear Aunt, to think how much I have written; pray forgive me.

Published on June 19, 2015 00:44

June 17, 2015

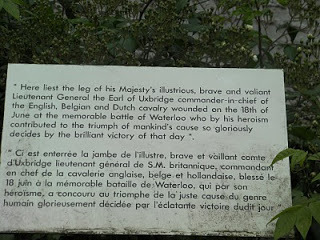

SIR FREDERICK CAVENDISH PONSONBY

This post was originally published on June 18, 2010.

As Victoria and I will be in Waterloo when you read this, I thought it might be fitting to tell you of the remarkable story of the survival of Sir Frederick Cavendish Ponsonby on the field of Waterloo. When one thinks of the great British soldiers at the Battle of Waterloo, one naturally conjures up visions of the Duke of Wellington, Alexander Gordon and, of course, the Marquess of Anglesey, but one rarely thinks of Sir Frederick Cavendish Ponsonby, whose Waterloo experience is, in my opinion, one of the most remarkable.

Here is the exceedingly dry manner in which Sir Frederick is summed up in The Waterloo Roll Call By Charles Dalton:

Aftds. Maj.-Gen. Sir Frederick Cavendish Ponsonby, K.C.B. and K.M.T., Gov. of Malta. 2nd son of Frederick, 3rd Earl of Bessborough, by Lady Henrietta, 2nd dau. of 1st Earl Spencer. Bn. 6th July, 1783. Cornet 10th Lt. Dgns. 1800. Maj. 23rd Lt. Dgns. 1807. At head of this regt. distinguished himself at Talavera, in 1809. Lt.-col. of the regt. 1810. At Barossa, with a squadron of German dragoons, he charged the French cavalry covering the retreat, overthrew them, and took two guns. Lt.-Col. 12th Lt. Dgns. 1811. Again signally distinguished himself at the battles of Salamanca and Vittoria.

From this, one would have nary a clue of the truly death-defying experience of this officer, a favorite of the Duke of Wellington's. Ponsonby was the the second son of the 3rd Earl of Bessborough and Henrietta (Harriet) Spencer, whose sister was Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire. Sir Frederick's own sister was the notorious Lady Caroline Lamb. Talk about your Regency soap opera - Lady Bessborough had had a brief affair with Richard Brinsley Sheridan and another with Lord Granville Leveson Gower, with whom she had two children before marrying him off to her niece, Lady Harriet Cavendish.

But I digress . . . . . .

In 1815, Frederick was 33 years of age when he was called to accompany Lord Castlereagh (above) to the Congress of Vienna, which sat after Napoleon's first abdication to restore the balance of power in Europe and to divide the spoils. The Congress was showing signs of violent disagreement, when to the horror and amazement of Europe, Napoleon escaped from Elba and landed at Cannes. The French Army rallied to him regiment by regiment as he marched through France toward the capital. He entered Paris on March 20, while the King and his family fled. Those English familites who had gone to Brussels to economize after the war knew that they were in a terrible position when Napoleon, who by then commanded an army of 535,000 men, marched to join it on the Belgian frontier on June 12.

At Waterloo, Sir Frederick was attached to the 12th Light Dragoons, who were ordered, along with the 16th Light Dragoons, to charge down a slope to support the withdrawal of the Union Brigade of heavy cavalry, which was being led by his second cousin, William Ponsonby, who lost his life that day. It would have been all too easy for Sir Frederick to have met his own death, as well. In fact, he would presently, and within a very short span of time, be presented with several ways in which he could have lost his life.

The best account of what occurred is the one given by Sir Frederick himself, as written in a letter to his mother by Lady Shelley:

Dear Lady Bessborough,

You have often wished for some written account of the adventures and sufferings of your son, Colonel Ponsonby, on the field of Waterloo; the modesty of his nature is however no small obstacle in the way. Will the following imperfect sketch supply its place until it comes? The battle of the 18th of June was one morning alluded to in the library at Althorpe, and his answers to many of the questions which were put to him are here thrown together, as nearly as I can remember in his own words.

"The weather cleared up at noon, and the sun shone out a little just as the battle began. The armies were within 800 yards of each other; the videttes, before they were withdrawn, being so near as to be able to converse. At one moment I imagined I saw Bonaparte; a considerable staff was moving rapidly along the front of our line. I was stationed with my regiment, about 300 strong, at the extreme of the left wing, and directed to act discretionally; each of the armies was drawn up on a gentle declivity, a small valley lying between them.

'"At one o'clock, observing, as I thought,unsteadiness in a column of French infantry of 1,000 men or thereabouts, which was advancing with an irregular fire, I resolved to charge them. As we were descending at a gallop we received from our own troops on the right a fire much more destructive than theirs, they having begun long before it could take effect, and slackening as we drew nearer. When we were within 50 paces of them, they turned, and much execution was done amongst them, as we were followed by some Belgians who had remarked our success. But we had no sooner passed through them, than we were attacked in our turn before we could form, by about 300 Polish Lancers, who had come down to their relief—the French artillery pouring in amongst us a heavy fire of grape-shot, which, however, for one of our men killed three of their own. In the melee I was disabled almost instantly in both my arms, and followed by a few of my men who were presently cut down—for no quarter was asked or given—I was carried on by my horse, till receiving a blow on my head from a sabre, I was thrown senseless on my face to the ground. Recovering, I raised myself a little to look round, being I believe at that time in a condition to get up and run away, when a Lancer, passing by, exclaimed : " Tu n'es pas mort, coquin," and struck his lance through my back. My head dropped, the blood gushed into my mouth; a difficulty of breathing came on, and I thought all was over. Not long afterwards (it was then impossible to measure time, but I must have fallen in less than ten minutes after the charge) a tirailleur came up to plunder me, threatening to take away my life. I told him that he might search me, directing him to a small side pocket, in which he found three dollars, being all I had. He unloosed my stock, and tore open my waistcoat, then leaving me in a very uneasy posture. He was no sooner gone, than another came up for the same purpose, but assuring him I had been plundered already, he left me. When an officer, bringing on some troops (to which probably the tirailleurs belonged) and halting where I lay, stooped down and addressed me, saying he feared I was badly wounded, I replied that I was, and expressed a wish to be removed into the rear. He said it was against the orders to remove even their own men, but that if they gained the day, as they probably would, for he understood the Duke of Wellington was killed and that six battalions of the English army had surrendered, every attention in his power should be shown me. I complained of thirst, and he held his brandy bottle to my lips, directing one of his men to lay me down on my side, and placed a knapsack under my head. He then passed on into the action, and I shall never know to whose generosity I was indebted, as I conceive, for my life. Of what rank he was I cannot say; he wore a blue great-coat. * By-and-bye another tirailleur came, and knelt down and fired over me, loading and firing many times, and conversing with great gaiety all the while. At last he ran off, saying: "Vous serez bien aise d'entendre que nous allons nous retirer. Bon jour, mon ami."

"Whilst the battle continued in that part, several of the wounded men and dead bodies near me were hit with the balls, which came very thick in that place. Towards evening, when the Prussians came up, the continued roar of cannon along their and the British line, growing louder and louder as they drew near, was the finest thing I ever heard. It was dusk when the two squadrons of Prussian cavalry, both of them two deep, passed over me in a full trot, lifting me from the ground, and tumbling me about cruelly—the clatter of their approach and the apprehensions it excited may be easily conceived. Had a gun come that way, it would have done for me. The battle was then nearly over, or removed to a distance. The cries and groans of the wounded all around me became every instant more and more audible, succeeding to the shouts, imprecations, and cries of " Vive l'Empereur," the discharges of musketry and cannon, now and then intervals of perfect quiet which were worse than the noise. I thought the night would never end. Much about this time one of the Royals lay across my legs—he had probably crawled thither in his agony—his weight, convulsive motions, his noises, and the air issuing through a wound in his side, distressed me greatly—the latter circumstance most of all, as the case was my own.

"It was not a dark night, and the Prussians were wandering about to plunder, and the scene in "Ferdinand Count Fathom" came into my mind, though no women, I believe, were there. Several Prussians came, looked at me, and passed on. At length one stopped to examine me. I told him as well as I could, for I could speak but little German, that I was a British officer, and had been plundered already. He did not desist, however, and pulled me about roughly before he left me. About an hour before midnight I saw a soldier in an English uniform coming towards me. He was, I suspect, on the same errand, but he came and looked in my face. I spoke instantly, telling him who I was, and assuring him of a reward if he would remain by me. He said that he belonged to the 40th Regiment, but that he had missed it. He released me from the dying man, and being unarmed, he took up a sword from the ground, and stood over me, pacing backwards and forwards.

"'At 8 o'clock in the morning some English were seen at a distance. He ran to them, and a messenger was sent off to Colonel Harvey. A cart came for me—I was placed on it, and carried to a farmhouse, about a mile and a half distant, and laid in the bed from which poor Gordon, as I understood afterwards, had been just carried out. The jolting of the carriage and the difficulty of breathing were very painful. I had received seven wounds; a surgeon slept in my room, and I was saved by continual bleeding—120 ounces in two days, besides a great loss of blood on the field.

"' The lances from their length and weight would have struck down my sword long before I lost it, if it had not been bound to my hand. What became of my horse I know not. It was the best I ever had."

As it happened, Lord and Lady Bessborough had been on a Continental tour in the months prior to Waterloo and were coming slowly home when the news reached them on July 8 that their son had been desperately wounded at the Battle of Waterloo. Lady Bessborough (at right) made a forced journey to Brussels to nurse him, and Lady Caroline Lamb joined her there. To her credit, Lady Bessborough nursed her son as he recuperated, but Lady Shelley's letter quoted above indicates that mother and son had not the opportunity, or the inclination, to then discuss Posonby's harrowing experience.

A few days later, that old gossip Creevey wrote: "On Tuesday the 20th . . . Barnes and Hamilton would make me ride over to see the field of battle, which I would willingly have declined, understanding all the French dead were still on the field—unburied, and having no one to instruct me in detail as to what had passed—I mean as to the relative positions of the armies, etc. However, I was mounted, and as I was riding along with Hamilton's groom behind me about a mile and a half on the Brussells side of the village of Waterloo, who should overtake me but the Duke of Wellington in his curricle, in his plain cloaths and Harvey by his side in his regimentals. So we went on together, and he said as he was to stop at Waterloo to see Frederick Ponsonby and de Lancey, Harvey should go with me and shew me the field of battle, and all about it. When we got to Waterloo village, we found others of his staff there, and it ended in Lord Arthur Hill being my guide over every part of the ground."

If Creevey's tour of the ground so soon after the battle seems goulish, here's a letter written by the recuperating Sir Frederick's own sister, Lady Caroline Lamb (at left), to the Viscountess Melbourne from Brussels, 1815. It is a pouty letter which brilliantly displays Caroline's petulance and immaturity in the face of so much heartbreak.

Dearest Lady Melbourne . . . The great amusement at Bruxelles, indeed the only one except visiting the sick, is to make large parties etc; go to the field of Battle and pick up a skull or a grape shot or an old shoe or a letter, etc.; bring it home. W[illia]m has been, I shall not go —unless when Fred [Ponsonby] gets better,etc; goes with me. There is a great affectation here of making lint etc.; bandages—but where is there not some? etc; at least it is an innocent amusement. It is rather a love making moment, the half wounded Officers reclining with pretty ladies visiting them—is dangerous. I also observe a great coxcombality in the dress of the sick— which prognosticates a speedy recovery. It is rather heart-breaking to be here, however, etc; one goes blubbering about—seeing such fine people without their legs etc.; arms, some in agony, etc; some getting better. The Prince of Orange enquired much after all his acquaintance; he suffers a great deal, but bears it well. The next door to us has a Col. Millar, very patient, but dreadfully wounded. Lady Conyngham is here—Lady C. Greville—Lady D. Hamilton, Mrs. A. B. Smith, Lady F. Somerset, Lady F. Webster most affected; Lady Mountmorress, who stuck her parasol yesterday into a skull at Waterloo. . . .

Sir Frederick recovered and went on to enjoy a close relationship with the Duke long after the battle, as shown in the following letter the Duke wrote to Lady Shelley:

London, September 21, 1821

My Dear Lady Shelley, I write to tell you that there is some prospect that the King will go out of town on Saturday, and in that case we might be able to go to you on Saturday evening, and stay till Tuesday or Wednesday. I will let you know positively to-morrow. Shall I bring down Frederick Ponsonby, who was going with me to S. Saye? Ever yours affectionately, W.

Sir Frederick married Lady Emily Charlotte Bathurst, daughter of Henry Bathurst, 3rd Earl Bathurst of Bathurst and Lady Georgina Lennox, on 16 March 1825. On 27 May 1825, he was promoted major-general, commanding the troops in the Ionian Islands and on 22 December 1826, he was appointed Governor of Malta, holding that post for eight and a half years. Sir Frederick died on 11 January 1837 at the age of fifty-three.

* This French officer was Major de Laussat of the Imperial Guard Dragoons, as Sir Frederick would learn in 1827 when the two met socially and soon after, through a conversation regarding the experiences of each during the Battle, discovered the coincidence of their first meeting upon the field.

As Victoria and I will be in Waterloo when you read this, I thought it might be fitting to tell you of the remarkable story of the survival of Sir Frederick Cavendish Ponsonby on the field of Waterloo. When one thinks of the great British soldiers at the Battle of Waterloo, one naturally conjures up visions of the Duke of Wellington, Alexander Gordon and, of course, the Marquess of Anglesey, but one rarely thinks of Sir Frederick Cavendish Ponsonby, whose Waterloo experience is, in my opinion, one of the most remarkable.

Here is the exceedingly dry manner in which Sir Frederick is summed up in The Waterloo Roll Call By Charles Dalton:

Aftds. Maj.-Gen. Sir Frederick Cavendish Ponsonby, K.C.B. and K.M.T., Gov. of Malta. 2nd son of Frederick, 3rd Earl of Bessborough, by Lady Henrietta, 2nd dau. of 1st Earl Spencer. Bn. 6th July, 1783. Cornet 10th Lt. Dgns. 1800. Maj. 23rd Lt. Dgns. 1807. At head of this regt. distinguished himself at Talavera, in 1809. Lt.-col. of the regt. 1810. At Barossa, with a squadron of German dragoons, he charged the French cavalry covering the retreat, overthrew them, and took two guns. Lt.-Col. 12th Lt. Dgns. 1811. Again signally distinguished himself at the battles of Salamanca and Vittoria.

From this, one would have nary a clue of the truly death-defying experience of this officer, a favorite of the Duke of Wellington's. Ponsonby was the the second son of the 3rd Earl of Bessborough and Henrietta (Harriet) Spencer, whose sister was Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire. Sir Frederick's own sister was the notorious Lady Caroline Lamb. Talk about your Regency soap opera - Lady Bessborough had had a brief affair with Richard Brinsley Sheridan and another with Lord Granville Leveson Gower, with whom she had two children before marrying him off to her niece, Lady Harriet Cavendish.

But I digress . . . . . .

In 1815, Frederick was 33 years of age when he was called to accompany Lord Castlereagh (above) to the Congress of Vienna, which sat after Napoleon's first abdication to restore the balance of power in Europe and to divide the spoils. The Congress was showing signs of violent disagreement, when to the horror and amazement of Europe, Napoleon escaped from Elba and landed at Cannes. The French Army rallied to him regiment by regiment as he marched through France toward the capital. He entered Paris on March 20, while the King and his family fled. Those English familites who had gone to Brussels to economize after the war knew that they were in a terrible position when Napoleon, who by then commanded an army of 535,000 men, marched to join it on the Belgian frontier on June 12.

At Waterloo, Sir Frederick was attached to the 12th Light Dragoons, who were ordered, along with the 16th Light Dragoons, to charge down a slope to support the withdrawal of the Union Brigade of heavy cavalry, which was being led by his second cousin, William Ponsonby, who lost his life that day. It would have been all too easy for Sir Frederick to have met his own death, as well. In fact, he would presently, and within a very short span of time, be presented with several ways in which he could have lost his life.

The best account of what occurred is the one given by Sir Frederick himself, as written in a letter to his mother by Lady Shelley:

Dear Lady Bessborough,

You have often wished for some written account of the adventures and sufferings of your son, Colonel Ponsonby, on the field of Waterloo; the modesty of his nature is however no small obstacle in the way. Will the following imperfect sketch supply its place until it comes? The battle of the 18th of June was one morning alluded to in the library at Althorpe, and his answers to many of the questions which were put to him are here thrown together, as nearly as I can remember in his own words.

"The weather cleared up at noon, and the sun shone out a little just as the battle began. The armies were within 800 yards of each other; the videttes, before they were withdrawn, being so near as to be able to converse. At one moment I imagined I saw Bonaparte; a considerable staff was moving rapidly along the front of our line. I was stationed with my regiment, about 300 strong, at the extreme of the left wing, and directed to act discretionally; each of the armies was drawn up on a gentle declivity, a small valley lying between them.

'"At one o'clock, observing, as I thought,unsteadiness in a column of French infantry of 1,000 men or thereabouts, which was advancing with an irregular fire, I resolved to charge them. As we were descending at a gallop we received from our own troops on the right a fire much more destructive than theirs, they having begun long before it could take effect, and slackening as we drew nearer. When we were within 50 paces of them, they turned, and much execution was done amongst them, as we were followed by some Belgians who had remarked our success. But we had no sooner passed through them, than we were attacked in our turn before we could form, by about 300 Polish Lancers, who had come down to their relief—the French artillery pouring in amongst us a heavy fire of grape-shot, which, however, for one of our men killed three of their own. In the melee I was disabled almost instantly in both my arms, and followed by a few of my men who were presently cut down—for no quarter was asked or given—I was carried on by my horse, till receiving a blow on my head from a sabre, I was thrown senseless on my face to the ground. Recovering, I raised myself a little to look round, being I believe at that time in a condition to get up and run away, when a Lancer, passing by, exclaimed : " Tu n'es pas mort, coquin," and struck his lance through my back. My head dropped, the blood gushed into my mouth; a difficulty of breathing came on, and I thought all was over. Not long afterwards (it was then impossible to measure time, but I must have fallen in less than ten minutes after the charge) a tirailleur came up to plunder me, threatening to take away my life. I told him that he might search me, directing him to a small side pocket, in which he found three dollars, being all I had. He unloosed my stock, and tore open my waistcoat, then leaving me in a very uneasy posture. He was no sooner gone, than another came up for the same purpose, but assuring him I had been plundered already, he left me. When an officer, bringing on some troops (to which probably the tirailleurs belonged) and halting where I lay, stooped down and addressed me, saying he feared I was badly wounded, I replied that I was, and expressed a wish to be removed into the rear. He said it was against the orders to remove even their own men, but that if they gained the day, as they probably would, for he understood the Duke of Wellington was killed and that six battalions of the English army had surrendered, every attention in his power should be shown me. I complained of thirst, and he held his brandy bottle to my lips, directing one of his men to lay me down on my side, and placed a knapsack under my head. He then passed on into the action, and I shall never know to whose generosity I was indebted, as I conceive, for my life. Of what rank he was I cannot say; he wore a blue great-coat. * By-and-bye another tirailleur came, and knelt down and fired over me, loading and firing many times, and conversing with great gaiety all the while. At last he ran off, saying: "Vous serez bien aise d'entendre que nous allons nous retirer. Bon jour, mon ami."

"Whilst the battle continued in that part, several of the wounded men and dead bodies near me were hit with the balls, which came very thick in that place. Towards evening, when the Prussians came up, the continued roar of cannon along their and the British line, growing louder and louder as they drew near, was the finest thing I ever heard. It was dusk when the two squadrons of Prussian cavalry, both of them two deep, passed over me in a full trot, lifting me from the ground, and tumbling me about cruelly—the clatter of their approach and the apprehensions it excited may be easily conceived. Had a gun come that way, it would have done for me. The battle was then nearly over, or removed to a distance. The cries and groans of the wounded all around me became every instant more and more audible, succeeding to the shouts, imprecations, and cries of " Vive l'Empereur," the discharges of musketry and cannon, now and then intervals of perfect quiet which were worse than the noise. I thought the night would never end. Much about this time one of the Royals lay across my legs—he had probably crawled thither in his agony—his weight, convulsive motions, his noises, and the air issuing through a wound in his side, distressed me greatly—the latter circumstance most of all, as the case was my own.

"It was not a dark night, and the Prussians were wandering about to plunder, and the scene in "Ferdinand Count Fathom" came into my mind, though no women, I believe, were there. Several Prussians came, looked at me, and passed on. At length one stopped to examine me. I told him as well as I could, for I could speak but little German, that I was a British officer, and had been plundered already. He did not desist, however, and pulled me about roughly before he left me. About an hour before midnight I saw a soldier in an English uniform coming towards me. He was, I suspect, on the same errand, but he came and looked in my face. I spoke instantly, telling him who I was, and assuring him of a reward if he would remain by me. He said that he belonged to the 40th Regiment, but that he had missed it. He released me from the dying man, and being unarmed, he took up a sword from the ground, and stood over me, pacing backwards and forwards.

"'At 8 o'clock in the morning some English were seen at a distance. He ran to them, and a messenger was sent off to Colonel Harvey. A cart came for me—I was placed on it, and carried to a farmhouse, about a mile and a half distant, and laid in the bed from which poor Gordon, as I understood afterwards, had been just carried out. The jolting of the carriage and the difficulty of breathing were very painful. I had received seven wounds; a surgeon slept in my room, and I was saved by continual bleeding—120 ounces in two days, besides a great loss of blood on the field.

"' The lances from their length and weight would have struck down my sword long before I lost it, if it had not been bound to my hand. What became of my horse I know not. It was the best I ever had."

As it happened, Lord and Lady Bessborough had been on a Continental tour in the months prior to Waterloo and were coming slowly home when the news reached them on July 8 that their son had been desperately wounded at the Battle of Waterloo. Lady Bessborough (at right) made a forced journey to Brussels to nurse him, and Lady Caroline Lamb joined her there. To her credit, Lady Bessborough nursed her son as he recuperated, but Lady Shelley's letter quoted above indicates that mother and son had not the opportunity, or the inclination, to then discuss Posonby's harrowing experience.

A few days later, that old gossip Creevey wrote: "On Tuesday the 20th . . . Barnes and Hamilton would make me ride over to see the field of battle, which I would willingly have declined, understanding all the French dead were still on the field—unburied, and having no one to instruct me in detail as to what had passed—I mean as to the relative positions of the armies, etc. However, I was mounted, and as I was riding along with Hamilton's groom behind me about a mile and a half on the Brussells side of the village of Waterloo, who should overtake me but the Duke of Wellington in his curricle, in his plain cloaths and Harvey by his side in his regimentals. So we went on together, and he said as he was to stop at Waterloo to see Frederick Ponsonby and de Lancey, Harvey should go with me and shew me the field of battle, and all about it. When we got to Waterloo village, we found others of his staff there, and it ended in Lord Arthur Hill being my guide over every part of the ground."

If Creevey's tour of the ground so soon after the battle seems goulish, here's a letter written by the recuperating Sir Frederick's own sister, Lady Caroline Lamb (at left), to the Viscountess Melbourne from Brussels, 1815. It is a pouty letter which brilliantly displays Caroline's petulance and immaturity in the face of so much heartbreak.

Dearest Lady Melbourne . . . The great amusement at Bruxelles, indeed the only one except visiting the sick, is to make large parties etc; go to the field of Battle and pick up a skull or a grape shot or an old shoe or a letter, etc.; bring it home. W[illia]m has been, I shall not go —unless when Fred [Ponsonby] gets better,etc; goes with me. There is a great affectation here of making lint etc.; bandages—but where is there not some? etc; at least it is an innocent amusement. It is rather a love making moment, the half wounded Officers reclining with pretty ladies visiting them—is dangerous. I also observe a great coxcombality in the dress of the sick— which prognosticates a speedy recovery. It is rather heart-breaking to be here, however, etc; one goes blubbering about—seeing such fine people without their legs etc.; arms, some in agony, etc; some getting better. The Prince of Orange enquired much after all his acquaintance; he suffers a great deal, but bears it well. The next door to us has a Col. Millar, very patient, but dreadfully wounded. Lady Conyngham is here—Lady C. Greville—Lady D. Hamilton, Mrs. A. B. Smith, Lady F. Somerset, Lady F. Webster most affected; Lady Mountmorress, who stuck her parasol yesterday into a skull at Waterloo. . . .

Sir Frederick recovered and went on to enjoy a close relationship with the Duke long after the battle, as shown in the following letter the Duke wrote to Lady Shelley:

London, September 21, 1821

My Dear Lady Shelley, I write to tell you that there is some prospect that the King will go out of town on Saturday, and in that case we might be able to go to you on Saturday evening, and stay till Tuesday or Wednesday. I will let you know positively to-morrow. Shall I bring down Frederick Ponsonby, who was going with me to S. Saye? Ever yours affectionately, W.

Sir Frederick married Lady Emily Charlotte Bathurst, daughter of Henry Bathurst, 3rd Earl Bathurst of Bathurst and Lady Georgina Lennox, on 16 March 1825. On 27 May 1825, he was promoted major-general, commanding the troops in the Ionian Islands and on 22 December 1826, he was appointed Governor of Malta, holding that post for eight and a half years. Sir Frederick died on 11 January 1837 at the age of fifty-three.