Kristine Hughes's Blog, page 60

May 6, 2016

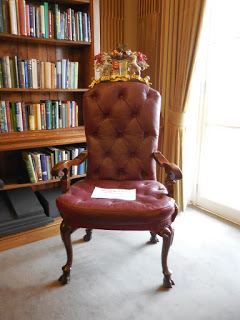

OPEN CITY DAYS: THE BRITISH ACADEMY

IN CARLTON TERRACE, occupying Numbers 10 and 11, the British Academy is the UK's national body for the humanities and social sciences – the study of peoples, cultures and societies, past, present and future. It funds fellowships, research grants, awards, and charitable activities, including British Film Awards.

The British Academy website is here.

On the ground floor for the Open City visitors, the BA displayed an exhibition of photos from the history of the house. Here is their explanation of the exhibition:

"From 1830 until 1920, 10 Carlton House Terrace was the London Home of the Ridley family. The Ridleys were a wealthy Northumberland family who had made their fortune in Coal mining. When war broke out, in 1914, Lady Ridley decided to open up her London home as a hospital for wounded officers.

Affiliated with Queen Alexandria’s Military Hospital in Milbank, it was principally a convalescent hospital. It was staffed by a house doctor, trained nurses, and members of London/52 Voluntary Aid Detachment (VADs). According to newspaper clippings of the time, it quickly established itself as ‘by far the most fashionable hospital for officers in the war'; and it soon became a popular sight-seeing spot. One report from the period states that ‘every morning an interested crowd collects to see the public shaving of the wounded soldiers, who are so comfortably situated in the temporary hospitals which are perched on the top of terraces behind Carlton House Terraces.’

In 1918, Lady Ridley was made a Dame in recognition of her work as donor and administrator of the Hospital. Upon the hospital’s closure in February 1919, she wrote to express her gratitude to those who had worked there: ‘It is largely owing to the devoted band of VADs that the hospital achieved such a standard of efficiency and comfort, and was and was able to bring such a great measure of relief and happiness to those who suffered so much in the War.’"

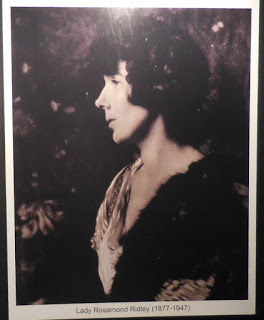

Lady Rosamund Ridley (1877-1947)

Lady Rosamund Ridley (1877-1947)

Lady Ridley was a cousin of Sir Winston Churchill and wife of Matthew White Ridley, 1st Viscount Ridley. At the beginning of the 20th century, the Ridleys redecorated the house in the French style and installed the grand staircase.

French Staircase

French Staircase

Beginning in 1914 with 25 beds, Lady Ridley expanded her hospital to 60 beds by 1917. One volunteer, Aileen Maunsell, became a nurse and worked at Lady Ridley's Hospital where she also entertained the patients by playing concerts for them. Eventually she married 2nd Lt. Gell in 1920.

Lady Ridley’s Hospital stayed open for several months after the war ended. In later years, the building was the residence of Lord Monson, four-time Prime Minister William Gladstone (1856 to 1875), and the Guinness family, before becoming home to the British Academy in 1998.

The music room from the wedding venue page

The music room from the wedding venue page

The British Academy was established in 1902; a fellowship of more than 900 leading scholars spanning all disciplines across the humanities and social sciences. it is an independent registered charity. The exterior of the building 10-11 Carlton House Terrace can be seen on the popular BBC's Sherlock,as the Diogenes Club.

Our next goal was a stroll down Pall Mall to Marlborough House...

The British Academy website is here.

On the ground floor for the Open City visitors, the BA displayed an exhibition of photos from the history of the house. Here is their explanation of the exhibition:

"From 1830 until 1920, 10 Carlton House Terrace was the London Home of the Ridley family. The Ridleys were a wealthy Northumberland family who had made their fortune in Coal mining. When war broke out, in 1914, Lady Ridley decided to open up her London home as a hospital for wounded officers.

Affiliated with Queen Alexandria’s Military Hospital in Milbank, it was principally a convalescent hospital. It was staffed by a house doctor, trained nurses, and members of London/52 Voluntary Aid Detachment (VADs). According to newspaper clippings of the time, it quickly established itself as ‘by far the most fashionable hospital for officers in the war'; and it soon became a popular sight-seeing spot. One report from the period states that ‘every morning an interested crowd collects to see the public shaving of the wounded soldiers, who are so comfortably situated in the temporary hospitals which are perched on the top of terraces behind Carlton House Terraces.’

In 1918, Lady Ridley was made a Dame in recognition of her work as donor and administrator of the Hospital. Upon the hospital’s closure in February 1919, she wrote to express her gratitude to those who had worked there: ‘It is largely owing to the devoted band of VADs that the hospital achieved such a standard of efficiency and comfort, and was and was able to bring such a great measure of relief and happiness to those who suffered so much in the War.’"

Lady Rosamund Ridley (1877-1947)

Lady Rosamund Ridley (1877-1947)Lady Ridley was a cousin of Sir Winston Churchill and wife of Matthew White Ridley, 1st Viscount Ridley. At the beginning of the 20th century, the Ridleys redecorated the house in the French style and installed the grand staircase.

French Staircase

French Staircase Beginning in 1914 with 25 beds, Lady Ridley expanded her hospital to 60 beds by 1917. One volunteer, Aileen Maunsell, became a nurse and worked at Lady Ridley's Hospital where she also entertained the patients by playing concerts for them. Eventually she married 2nd Lt. Gell in 1920.

Lady Ridley’s Hospital stayed open for several months after the war ended. In later years, the building was the residence of Lord Monson, four-time Prime Minister William Gladstone (1856 to 1875), and the Guinness family, before becoming home to the British Academy in 1998.

The music room from the wedding venue page

The music room from the wedding venue pageThe British Academy was established in 1902; a fellowship of more than 900 leading scholars spanning all disciplines across the humanities and social sciences. it is an independent registered charity. The exterior of the building 10-11 Carlton House Terrace can be seen on the popular BBC's Sherlock,as the Diogenes Club.

Our next goal was a stroll down Pall Mall to Marlborough House...

Published on May 06, 2016 00:00

May 4, 2016

TRACY GRANT WRITES OF APSLEY HOUSE, AKA NUMBER ONE LONDON

Welcome author Tracy Grant, who newest title, London Gambit. is released tomorrow. She is continuing her series about Malcolm and Suzanne Rannoch...and this time, they are to be found at none other than our favorite Apsley House, residence of the Dukes of Wellington and the Wellington Museum.

Tracy's website can be found here.

From Tracy Grant: A decade ago, on a research trip to London, I spent a wonderful morning at Apsley House, the Duke of Wellington’s London home, now the Wellington Museum, which stands at Hyde Park Corner. Along with taking in fascinating details, from the beautiful and surprisingly livable rooms, to the Waterloo memorabilia, to the naked statue of Napoleon Bonaparte at the base of the stairs, I learned about the banquets Wellington gave for Waterloo veterans on the anniversary of the battle. The idea of those banquets stayed with me through the years. Through writing the adventures of married spies Malcolm and Suzanne Rannoch at the Congress of Vienna, the battle of Waterloo, and post-Waterloo Paris (the latter of which two books, Imperial Scandal and The Paris Affair, include Wellington himself and several of his officers as characters), through the birth of my daughter (now four), through researching numerous other settings and bringing Malcolm and Suzanne and the series back to London.

Apsley House (English Heritage)

Apsley House (English Heritage)The timeline of the series naturally set the most recent book, London Gambit (which will be released tomorrow, May 5), in June 1818. Perhaps the date, three years after Waterloo, subconsciously influenced me, because as I developed the plot, I found echoes of the battle running through the story, both for the fictional characters - Malcolm and Suzanne, their friend Harry who was wounded at Waterloo, Harry’s wife Cordelia, their friends David and Simon who helped Suzanne and Cordelia nurse the wounded during the battle - and the real historical characters such as Fitzroy Somerset, Wellington’s military secretary, who lost his arm at Waterloo.

I needed a major social event for the denouement of the book, and I really wanted it to revolve round the anniversary of Waterloo on 18 June. But in 1818, Wellington was still British ambassador to France and based in Paris, though he already had come into possession of Apsley House. The house was designed by Robert Adam and built in the 1770s for the second Earl of Bathurst (who had been Baron Apsley before he succeeded to the earldom). Wellington's brother Richard, Marquess Wellesley, purchased Apsley House in 1807 and engaged James Wyatt to improve it (with the assistance of Thomas Cundy). Though the grateful nation offered to build Wellington a London home, Wellington instead bought Apsley House from his brother in 1817 (to help Richard out of financial difficulties). In 1818 Wellington engaged Benjamin Dean Wyatt, James Wyatt’s son, to make repairs to the house. Wyatt installed the nude statue of Napoleon by Antonio Canova, which Wellington had acquired, at the base of the stairs.

Napoleon by Canova, in Apsley House (Victoria's photo)

Napoleon by Canova, in Apsley House (Victoria's photo)Though he purchased Apsley House in 1817, Wellington probably didn’t give his first banquet for Waterloo veterans at Apsley House until 1820, and the first of his banquets took place in a dining room that could only seat 35, so the guests were limited to senior officers. After the Waterloo Gallery was completed in 1830, up to 85 guests could attend, including guests who had not been present at the battle, but the guest list was limited to men. There’s a painting of the banquet in 1836 by William Salter (capturing the moment when Wellington proposed a toast to the sovereign, after which the band played the national anthem) that shows some ladies standing by the door, including Fitzroy Somerset’s wife Emily Harriet, who was Wellington’s niece, and a “Miss Somerset” who may be their daughter who was a baby at the time of Waterloo, born in Brussels in the weeks before the battle. Perhaps they had been dining separately in the house and joined the gentlemen for the toast.

Waterloo Banquet by William Salter, 1836

Waterloo Banquet by William Salter, 1836While I worked on the first draft of London Gambit, I danced round what to do with the Waterloo anniversary. I thought about having a fictional character give a dinner on 18 June. I even thought about having Wellington come over from Paris for the fictional dinner. And then I thought—Wellington did own Apsley House in 1818. He could have given a dinner on the anniversary of Waterloo (even if in fact he did not). And, since the dinner in my book would be fictional, he could include women among the guests…

Historical novelists always to a certain degree combine fact and fiction because we fill in gaps in the historical record. This is even more true when one writes novels such as I do with fictional main characters and real historical figures in major supporting roles. One inevitably combines historical events with fictional ones. I try to stick closely to the historical record, but of course I end up taking some liberties with it whether it's Lady Caroline Lamb, a childhood friend of my fictional Cordelia Davenport, putting Lord and Lady Castlereagh at a fictional ball they of course wouldn’t have attended, having Malcolm pressed not delivering messages for Wellington during Waterloo (though in point of fact with so many of his aides-de-camp wounded, Wellington did press some civilians into service), or having Castlereagh, Wellington, and Sir Charles Stuart preoccupied with the intrigue surrounding the death of my fictional Antoine Rivère in post-Waterloo Paris. I try to stick to having real historical characters only do things they might have done. For instance, if a real historical figure was known to have a string of love affairs, I might involved them in a fictional one, but if they were known to be a famously faithful spouse, I wouldn’t think it was fair to do so.

By that logic, since Wellington could have come to London and given a dinner on the third anniversary of Waterloo, having him host a dinner in the book was in line with the sort of historical liberties I take in the series. Fitzroy Somerset was Wellington’s secretary at the British embassy in Paris in June 1818, but he stood for and won a parliamentary seat at Truro in the General Election in 1818, and he was in Truro for the election, so I had already decided it was all right to have him visiting England in June so he could be a character in the book. I debated some more about the banquet, wrote the ending with Wellington giving the dinner at Apsley House, debated changing it in subsequent drafts. In the end I left it, with an historical note explaining the liberties I had taken. Reading over the galleys, I was glad I did. The Waterloo anniversary ties the themes in the book together beautifully and having the event at Apsley House with Wellington present gives the added resonance to the echoes of Waterloo that run through the story.

Author Tracy Grant with her daughter and their kitties

Author Tracy Grant with her daughter and their kittiesFor more information about Apsley House and Wellington, the Victoria and Albert Museum offers an excellent publication book Apsley House: Wellington Museum(London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 2001). The Apsley House website is here.

Readers, how do you feel about writers taking liberties with the historical record? Writers, what liberties have you taken with historical figures, events, and timing?

Published on May 04, 2016 00:00

May 2, 2016

KERRYN REID LEARNING TO WALTZ

Last fall, when I found out Learning to Waltz had been chosen best Regency romance for 2014 by Chanticleer Book Reviews, Victoria and Kristine invited me to Number One London to share my excitement. (See that post here.)

I’m back again, because at long last I have received my prize: A free Chanticleer review. Five stars! I’d say it was worth the wait. (Read the review here.)

“Reid's focus,” says the reviewer, “is on her richly developed characters, not just costumes and carriages.” She is right that character comes first. A novel without memorable characters isn’t worth reading. And beyond memorable, there has to be at least one I really like and can root for, however flawed he or she might be. (In Learning to Waltz, of course, there is more than one. In fact, I have a soft spot for each and every one of them. Yes, even Doctor Overley and Deborah’s feckless brother!)

But setting runs a pretty close second, and that makes “costumes and carriages” important too. Setting encompasses a lot of different elements, from geography and climate to the scene outside – and inside – the window. But in historical fiction, so much of setting is wrapped up in when the story takes place. Costumes and carriages, of course, but also language, food, holidays, religion, political events… aargh, the list goes on forever. Yet these details of daily life add so much! They make it feel authentic, realistic. They help draw a reader into the story and persuade her it really could have happened.

Which brings me (finally!) to today’s topic: research. Most of the historical writers I know love research as much as they love writing. Many of us could get lost in it and never come out again. After all, if we didn’t like history, we would probably choose a different genre.

Research is critical to a good historical novel – thankfully there’s a lot of information out there! Too much, I sometimes think. Books from the period ran the gamut from Gothic novels to sermons, travelogues to gardening. Newspapers covered politics, entertainment and more. (Even the ads are fascinating.) A wide variety of periodicals provide abundant information about literature, science, fashion. And there are the personal documents: letters, ledgers, household lists and “receipts” (recipes), and so much more.

Plenty of important history took place during the Regency, from the Napoleonic wars on down; there were bound to be historical researchers digging in and writing about their findings. But it makes a difference, I think, that Regency Romance has been popular for so long. Since Georgette Heyer published Regency Buck in 1935, this brief ten-year span (1811-1820) has received more than its share of attention from novelists. While the historians pry out political secrets, others delight in discovering the daily facts of life and write their own books, not only novels but also non-fiction to help other writers and enthusiasts.

My humble Regency research library consists of some 70 volumes. Sounds like a lot, yet there are probably thousands more. Unfortunately I don’t have the money to buy them, the space to keep them, or the time to read them. In fact, I don’t often sit down and read the books I have; when I have a question I need answered, I pull out the most likely ones and utter some swear words about inadequate indexing. Then I go to the internet, where there are hundreds of blogs and newsletters on the subject, most of them easy to navigate. Maybe that’s because they’re mostly published by my fellow Regency writers, who know how important it is to be able to find what you’re looking for!

My second book will have the benefit of another type of research! I expect to have a complete first draft by the time I visit Yorkshire in October, but there will still be time for changes. I want to see those northern moors in person, and the 1808 library in Leeds where I’ve set a crucial scene. I want to see historical buildings large and small, rich and poor, and find out what they’re made of. Leeds has some fantastic online resources, but I want more! I only wish I could see it as it was in 1822! A couple of hours would do, just until I needed a proper toilet.

I’m sorry I couldn’t give Learning to Waltz that kind of attention. Measham, where most of the action takes place, is fictional, but Lydford, where Deborah grew up, is very real. Dawlish too, where Evan explores the natural arch in what was then Langstone Headland and rides breakneck down the beach in a storm. Finding that arch online inspired the scene, which is a turning point in the story. I’m sure the local residents in both places – particularly the town historians – would have no trouble finding inaccuracies.

Dawlish Beach, 1881

Dawlish Beach, 1881

(You can see the arch at the far left in this 1881 photo. At low tide it was, and still is, approachable on foot – or horseback. What you can’t see is the railroad, built directly along the beachfront in the 1840s. In laying the railbed, they also cut through the headland. The arch, and the rock that contains it, still exist, however. And I sure would have liked to see them before I wrote about them!)

I could, and probably should, have spent ten years doing research before ever setting pen to paper. And traveling all around the British Isles taking notes on absolutely everything! But I’m betting there would still be questions. I would still be searching books and the internet to find the answers. And alas, I would still be making mistakes. I just have to hope the reviewers don’t catch them!

Join my newsletter family! You can find a recent issue here. Each month I share some of my research on social history, and much more besides.

www.kerrynreid.comfacebook.com/kerrynreid.fictionhttps://twitter.com/kerryn_reid

I’m back again, because at long last I have received my prize: A free Chanticleer review. Five stars! I’d say it was worth the wait. (Read the review here.)

“Reid's focus,” says the reviewer, “is on her richly developed characters, not just costumes and carriages.” She is right that character comes first. A novel without memorable characters isn’t worth reading. And beyond memorable, there has to be at least one I really like and can root for, however flawed he or she might be. (In Learning to Waltz, of course, there is more than one. In fact, I have a soft spot for each and every one of them. Yes, even Doctor Overley and Deborah’s feckless brother!)

But setting runs a pretty close second, and that makes “costumes and carriages” important too. Setting encompasses a lot of different elements, from geography and climate to the scene outside – and inside – the window. But in historical fiction, so much of setting is wrapped up in when the story takes place. Costumes and carriages, of course, but also language, food, holidays, religion, political events… aargh, the list goes on forever. Yet these details of daily life add so much! They make it feel authentic, realistic. They help draw a reader into the story and persuade her it really could have happened.

Which brings me (finally!) to today’s topic: research. Most of the historical writers I know love research as much as they love writing. Many of us could get lost in it and never come out again. After all, if we didn’t like history, we would probably choose a different genre.

Research is critical to a good historical novel – thankfully there’s a lot of information out there! Too much, I sometimes think. Books from the period ran the gamut from Gothic novels to sermons, travelogues to gardening. Newspapers covered politics, entertainment and more. (Even the ads are fascinating.) A wide variety of periodicals provide abundant information about literature, science, fashion. And there are the personal documents: letters, ledgers, household lists and “receipts” (recipes), and so much more.

Plenty of important history took place during the Regency, from the Napoleonic wars on down; there were bound to be historical researchers digging in and writing about their findings. But it makes a difference, I think, that Regency Romance has been popular for so long. Since Georgette Heyer published Regency Buck in 1935, this brief ten-year span (1811-1820) has received more than its share of attention from novelists. While the historians pry out political secrets, others delight in discovering the daily facts of life and write their own books, not only novels but also non-fiction to help other writers and enthusiasts.

My humble Regency research library consists of some 70 volumes. Sounds like a lot, yet there are probably thousands more. Unfortunately I don’t have the money to buy them, the space to keep them, or the time to read them. In fact, I don’t often sit down and read the books I have; when I have a question I need answered, I pull out the most likely ones and utter some swear words about inadequate indexing. Then I go to the internet, where there are hundreds of blogs and newsletters on the subject, most of them easy to navigate. Maybe that’s because they’re mostly published by my fellow Regency writers, who know how important it is to be able to find what you’re looking for!

My second book will have the benefit of another type of research! I expect to have a complete first draft by the time I visit Yorkshire in October, but there will still be time for changes. I want to see those northern moors in person, and the 1808 library in Leeds where I’ve set a crucial scene. I want to see historical buildings large and small, rich and poor, and find out what they’re made of. Leeds has some fantastic online resources, but I want more! I only wish I could see it as it was in 1822! A couple of hours would do, just until I needed a proper toilet.

I’m sorry I couldn’t give Learning to Waltz that kind of attention. Measham, where most of the action takes place, is fictional, but Lydford, where Deborah grew up, is very real. Dawlish too, where Evan explores the natural arch in what was then Langstone Headland and rides breakneck down the beach in a storm. Finding that arch online inspired the scene, which is a turning point in the story. I’m sure the local residents in both places – particularly the town historians – would have no trouble finding inaccuracies.

Dawlish Beach, 1881

Dawlish Beach, 1881(You can see the arch at the far left in this 1881 photo. At low tide it was, and still is, approachable on foot – or horseback. What you can’t see is the railroad, built directly along the beachfront in the 1840s. In laying the railbed, they also cut through the headland. The arch, and the rock that contains it, still exist, however. And I sure would have liked to see them before I wrote about them!)

I could, and probably should, have spent ten years doing research before ever setting pen to paper. And traveling all around the British Isles taking notes on absolutely everything! But I’m betting there would still be questions. I would still be searching books and the internet to find the answers. And alas, I would still be making mistakes. I just have to hope the reviewers don’t catch them!

Join my newsletter family! You can find a recent issue here. Each month I share some of my research on social history, and much more besides.

www.kerrynreid.comfacebook.com/kerrynreid.fictionhttps://twitter.com/kerryn_reid

Published on May 02, 2016 00:00

April 29, 2016

POST-TOUR JAUNTS: THE JOYS OF OPEN CITY DAYS

WE TOUR SOME GREAT OLD BUILDINGS

OPEN CITY is a thriving organization which runs many tours and programs. See their website here, and learn all about their many activities throughout the year. We attended as many events as we could during their annual opening of London Buildings in September 2014. In 2016, Open City days are Saturday and Sunday, September 17 and 18. Free open weekends are held in many cities, including in the U.S. Some great viewing available!!

Victoria here. Though no one can see Carlton House, the Prince Regent's demolished palace, pulled down in 1824-5-6, we did the next best thing. The location of the former palace is now occupied by Waterloo Place and Carlton House Terrace, two rows of tall white stuccoed mansions built in 1827-32. Most of them are occupied by institutions rather than the grand aristocratic families who once resided there.

Here is the door of #6, now the Royal Society. Before WWII, this was the German Embassy, domain of Ambassador von Ribbentrop.

Here is the door of #6, now the Royal Society. Before WWII, this was the German Embassy, domain of Ambassador von Ribbentrop.

The Royal Society is an independent scientific academy in Britain and the Commonwealth, founded in 1660 as an "invisible college of natural philosophers." Today there are 1,600 fellows.

James Watt F.R.S. (Fellow of the Royal Society)

James Watt F.R.S. (Fellow of the Royal Society)

The rooms are beautifully appointed, certainly redone since its beginning, but preserving the character of the early 19th Century.

The rooms are beautifully appointed, certainly redone since its beginning, but preserving the character of the early 19th Century.

Stairway details

Stairway details

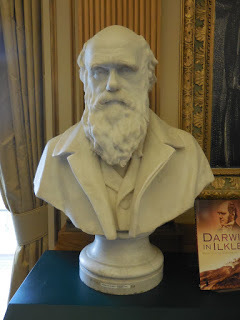

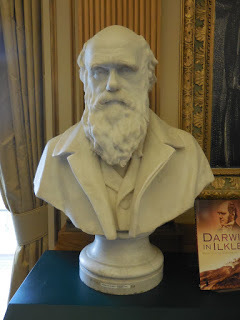

Charles Darwin 1809-1882naturalist and writer on evolution

Charles Darwin 1809-1882naturalist and writer on evolution

looking out

looking out

library

library

Benjamin Franklin, who spent many years in London, was a member.

Benjamin Franklin, who spent many years in London, was a member.

The Royal Society's website is here.

The Royal Society's website is here.

Though we certainly appreciated the many scientific achievements of the fellows and the contributions of the Royal Society to the advancement of science, I have to admit we we even more captivated by examining the architecture and decor, imagining what it must have been long ago. Luckily we had another spot to visit in the Carlton House Terrace, next time.

OPEN CITY is a thriving organization which runs many tours and programs. See their website here, and learn all about their many activities throughout the year. We attended as many events as we could during their annual opening of London Buildings in September 2014. In 2016, Open City days are Saturday and Sunday, September 17 and 18. Free open weekends are held in many cities, including in the U.S. Some great viewing available!!

Victoria here. Though no one can see Carlton House, the Prince Regent's demolished palace, pulled down in 1824-5-6, we did the next best thing. The location of the former palace is now occupied by Waterloo Place and Carlton House Terrace, two rows of tall white stuccoed mansions built in 1827-32. Most of them are occupied by institutions rather than the grand aristocratic families who once resided there.

Here is the door of #6, now the Royal Society. Before WWII, this was the German Embassy, domain of Ambassador von Ribbentrop.

Here is the door of #6, now the Royal Society. Before WWII, this was the German Embassy, domain of Ambassador von Ribbentrop.

The Royal Society is an independent scientific academy in Britain and the Commonwealth, founded in 1660 as an "invisible college of natural philosophers." Today there are 1,600 fellows.

James Watt F.R.S. (Fellow of the Royal Society)

James Watt F.R.S. (Fellow of the Royal Society) The rooms are beautifully appointed, certainly redone since its beginning, but preserving the character of the early 19th Century.

The rooms are beautifully appointed, certainly redone since its beginning, but preserving the character of the early 19th Century.

Stairway details

Stairway details

Charles Darwin 1809-1882naturalist and writer on evolution

Charles Darwin 1809-1882naturalist and writer on evolution looking out

looking out

library

library

Benjamin Franklin, who spent many years in London, was a member.

Benjamin Franklin, who spent many years in London, was a member. The Royal Society's website is here.

The Royal Society's website is here.Though we certainly appreciated the many scientific achievements of the fellows and the contributions of the Royal Society to the advancement of science, I have to admit we we even more captivated by examining the architecture and decor, imagining what it must have been long ago. Luckily we had another spot to visit in the Carlton House Terrace, next time.

Published on April 29, 2016 00:00

April 26, 2016

THE ADVENTURES OF A TOUR GUIDE

Number One London is preparing a line up of new tours for 2017!

We don't have details yet, as various components of the tours still have to be finalized. To that end, Kristine will be making the ultimate sacrifice - another trip to England beginning on May 1.

Regency author Diane Gaston (Perkins) will be along for the ride. And I do mean ride. Whilst I'll be busy attending to serious tour business, there's no telling what Diane will be getting up to. I've travelled to England with Diane in the past - I know whereof I speak. Here's the proof -

At Belvoir Castle, Diane picked up a pair of Highwaymen.

Next thing I knew, she was taking riding lessons at The Jockey Club in Newmarket. She said it was all in the name of research, but I have my doubts.

Check out her latest release and see if you can find any passages based on this "research."

Diane and I will be visiting London, the Peak District, Derby and Brighton. Along the way, in addition to attending to business, we'll be visiting with old friends, making new friends and business partners, attending the theatre, viewing stately homes, strolling a beach or two, checking out museums, taking a private tour of Buckingham Palace and seeing a few exhibitions. And yes, we will be re-visiting Apsley House.

Of course, we'll be taking new selfies all along the way. And while we're in England, I'll be regularly posting to social media so be sure to check my personal Facebook page and our Number One London Facebook page, as well as Twitter and Instagram.

Stay tuned for details on all 2017 Tours coming soon!

Published on April 26, 2016 23:30

April 25, 2016

WHAT KRISTINE SAW ON THE TUBE

Published on April 25, 2016 00:00

April 22, 2016

OUR TOUR OF THE THEATRE ROYAL DRURY LANE

The souvenir brochure at the Drury Lane Theatre opens with this statement: "Theatre Royal Drury Lane has, over the last three centuries, established itself as a centre of performing excellence and extraordinary versatility. Tragedy, fire, bankruptcy and argument have all taken their toll, nonetheless "Old Drury" has survived to earn itself a reputation second to none."

Victoria, here, reporting on the tour Kristine and I took of the theatre a few days after the conclusion of the Duke of Wellington Tour in September 2014. The Grade One Listed building claims to be the oldest theatre still in use in London.

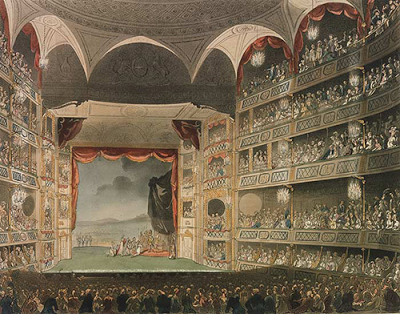

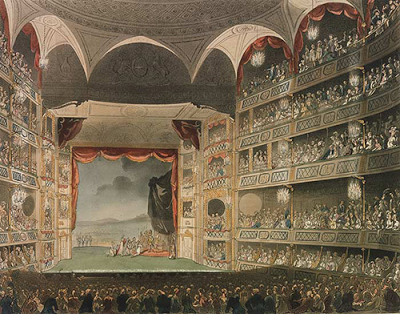

Drury Lane Theatre, c. 1808, third building of the name on the siteby Rowlandson and Pugin

Drury Lane Theatre, c. 1808, third building of the name on the siteby Rowlandson and Pugin

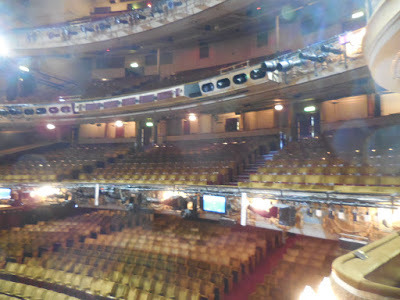

Today's Theatre Royal Drury Lane

Today's Theatre Royal Drury Lane

\

\

In 1809, the Theatre Royal Drury Lane burned down. A famous story is told about Richard Brinsley Sheridan, an MP, playwright, and owner of the theatre. Supposedly, he watched the flames from the street while sipping a glass of wine, and said, "Surely a man may be allowed to take a glass of wine by his own fireside."

The present building dates from 1812, the fourth theatre here since Restoration times. However, as we learned, portions of the "workings" below stage date from earlier years.

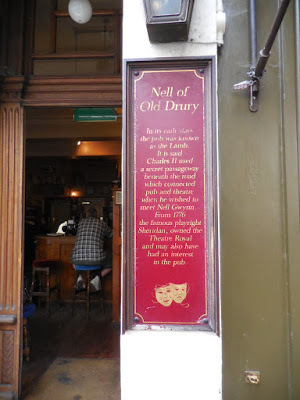

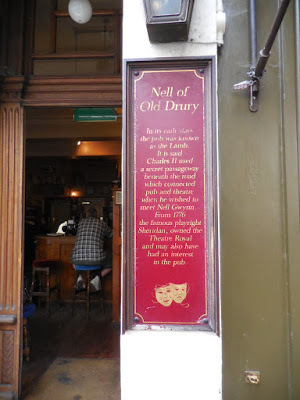

Nell of Old Drury: In its early days the pub was known as The Lamb. It is said Charles II used a secret passage way beneath the road which connected pub and theatre when he wished to meet Nell Gwynn.

Nell of Old Drury: In its early days the pub was known as The Lamb. It is said Charles II used a secret passage way beneath the road which connected pub and theatre when he wished to meet Nell Gwynn.

The inside of the theatre, the rotunda, lobbies, and bars are lavishly built and decorated, as befit the place to see and be seen.

In 2013, Andrew Lloyd Webber purchased this copy of Antonio Canova's famous sculpture "The Three Graces" to stand in the lower rotunda. Restoration of the theatre had returned the decor and colors to their Georgian originals, in keeping with Webber's desire to have it reflect authentic Regency design.

Edmund Kean (1787-1833) performed at as Shylock in Shakespeare's Merchant of Venice in 1814, supposedly causing some to faint in their seats at his realism.

Edmund Kean (1787-1833) performed at as Shylock in Shakespeare's Merchant of Venice in 1814, supposedly causing some to faint in their seats at his realism.

King George III loved watching the audience members arriving from the balcony of the rotunda. When he became outraged that his son, the future Prince Regent and George IV, created a disturbance with his noisy friends, the theatre managers were upset.

King George III loved watching the audience members arriving from the balcony of the rotunda. When he became outraged that his son, the future Prince Regent and George IV, created a disturbance with his noisy friends, the theatre managers were upset.

Ultimately they split the entrance into King's and Prince's sides, which remain today.

Ultimately they split the entrance into King's and Prince's sides, which remain today.

Michael William Balfe, (1808-1870), Composer, Violinist and Singer

Michael William Balfe, (1808-1870), Composer, Violinist and Singer

David Garrick (1717-1779) Poet, Actor, and Producer, managed the Drury Lane for 29 years.

David Garrick (1717-1779) Poet, Actor, and Producer, managed the Drury Lane for 29 years.

William Shakespeare (1564-1616) Poet, Playwright

William Shakespeare (1564-1616) Poet, Playwright

Above and below, The Royal Retiring Room

Above and below, The Royal Retiring Room

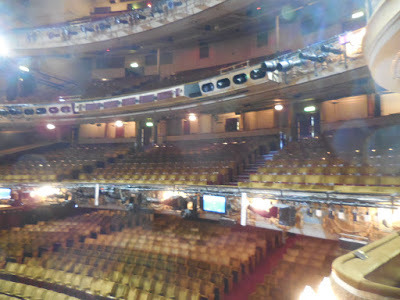

Below, the Auditorium, stage at left

The Prince's Side

The Prince's Side

The King's Side, above and below

The King's Side, above and below

lighting above the stage

lighting above the stage

Above and below, the Grand Saloon

Above and below, the Grand Saloon

Ivor Novello (1893-1951) Composer and Actor

Ivor Novello (1893-1951) Composer and Actor

Ira Aldridge (1807-1867) Famous Shakespearean Actor"The African Roscius"

Ira Aldridge (1807-1867) Famous Shakespearean Actor"The African Roscius"

Bomb Casing from the Blitz; the theatre continued to operate during WWII

Bomb Casing from the Blitz; the theatre continued to operate during WWII

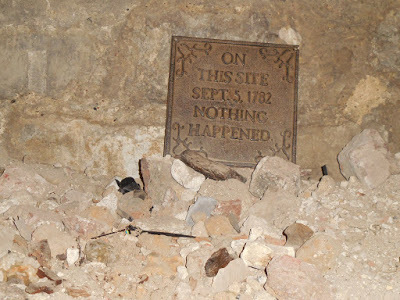

Some wag's comment on the "luminaries" throughout the building

Some wag's comment on the "luminaries" throughout the building

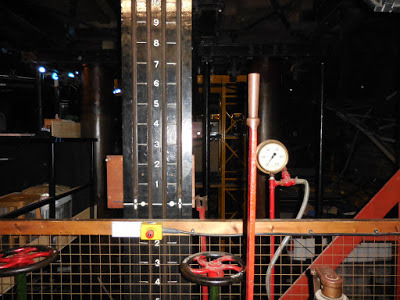

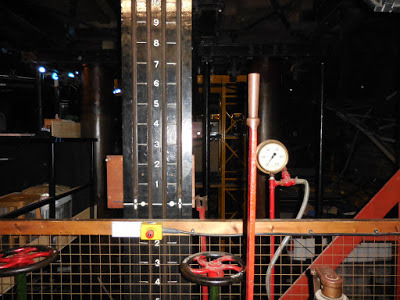

Above and below; deep under the stage some of the mechanicals date back to the 18th Century

Above and below; deep under the stage some of the mechanicals date back to the 18th Century

The excellent technical equipment and huge stage have allowed vast spectacles to be performed at Drury Lane, including one I saw a few years ago, Miss Saigon, which had a helicopter land on the stage. The production showing when we visited was Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.

The excellent technical equipment and huge stage have allowed vast spectacles to be performed at Drury Lane, including one I saw a few years ago, Miss Saigon, which had a helicopter land on the stage. The production showing when we visited was Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.

Outside, the Stage Door

Outside, the Stage Door

Nearby, a memorial to Sir Augustus Harris (1825-1873)Actor, Dramatist and Impresario, manager of the Drury Lane

Nearby, a memorial to Sir Augustus Harris (1825-1873)Actor, Dramatist and Impresario, manager of the Drury Lane

Our intrepid tour guide who did a wonderful job, but couldn't turn up any of the theatre's ghosts

Our intrepid tour guide who did a wonderful job, but couldn't turn up any of the theatre's ghosts

Victoria, here, reporting on the tour Kristine and I took of the theatre a few days after the conclusion of the Duke of Wellington Tour in September 2014. The Grade One Listed building claims to be the oldest theatre still in use in London.

Drury Lane Theatre, c. 1808, third building of the name on the siteby Rowlandson and Pugin

Drury Lane Theatre, c. 1808, third building of the name on the siteby Rowlandson and Pugin Today's Theatre Royal Drury Lane

Today's Theatre Royal Drury Lane

\

\In 1809, the Theatre Royal Drury Lane burned down. A famous story is told about Richard Brinsley Sheridan, an MP, playwright, and owner of the theatre. Supposedly, he watched the flames from the street while sipping a glass of wine, and said, "Surely a man may be allowed to take a glass of wine by his own fireside."

The present building dates from 1812, the fourth theatre here since Restoration times. However, as we learned, portions of the "workings" below stage date from earlier years.

Nell of Old Drury: In its early days the pub was known as The Lamb. It is said Charles II used a secret passage way beneath the road which connected pub and theatre when he wished to meet Nell Gwynn.

Nell of Old Drury: In its early days the pub was known as The Lamb. It is said Charles II used a secret passage way beneath the road which connected pub and theatre when he wished to meet Nell Gwynn.

The inside of the theatre, the rotunda, lobbies, and bars are lavishly built and decorated, as befit the place to see and be seen.

In 2013, Andrew Lloyd Webber purchased this copy of Antonio Canova's famous sculpture "The Three Graces" to stand in the lower rotunda. Restoration of the theatre had returned the decor and colors to their Georgian originals, in keeping with Webber's desire to have it reflect authentic Regency design.

Edmund Kean (1787-1833) performed at as Shylock in Shakespeare's Merchant of Venice in 1814, supposedly causing some to faint in their seats at his realism.

Edmund Kean (1787-1833) performed at as Shylock in Shakespeare's Merchant of Venice in 1814, supposedly causing some to faint in their seats at his realism. King George III loved watching the audience members arriving from the balcony of the rotunda. When he became outraged that his son, the future Prince Regent and George IV, created a disturbance with his noisy friends, the theatre managers were upset.

King George III loved watching the audience members arriving from the balcony of the rotunda. When he became outraged that his son, the future Prince Regent and George IV, created a disturbance with his noisy friends, the theatre managers were upset. Ultimately they split the entrance into King's and Prince's sides, which remain today.

Ultimately they split the entrance into King's and Prince's sides, which remain today.

Michael William Balfe, (1808-1870), Composer, Violinist and Singer

Michael William Balfe, (1808-1870), Composer, Violinist and Singer David Garrick (1717-1779) Poet, Actor, and Producer, managed the Drury Lane for 29 years.

David Garrick (1717-1779) Poet, Actor, and Producer, managed the Drury Lane for 29 years. William Shakespeare (1564-1616) Poet, Playwright

William Shakespeare (1564-1616) Poet, Playwright Above and below, The Royal Retiring Room

Above and below, The Royal Retiring Room

Below, the Auditorium, stage at left

The Prince's Side

The Prince's Side

The King's Side, above and below

The King's Side, above and below

lighting above the stage

lighting above the stage Above and below, the Grand Saloon

Above and below, the Grand Saloon

Ivor Novello (1893-1951) Composer and Actor

Ivor Novello (1893-1951) Composer and Actor Ira Aldridge (1807-1867) Famous Shakespearean Actor"The African Roscius"

Ira Aldridge (1807-1867) Famous Shakespearean Actor"The African Roscius" Bomb Casing from the Blitz; the theatre continued to operate during WWII

Bomb Casing from the Blitz; the theatre continued to operate during WWII Some wag's comment on the "luminaries" throughout the building

Some wag's comment on the "luminaries" throughout the building Above and below; deep under the stage some of the mechanicals date back to the 18th Century

Above and below; deep under the stage some of the mechanicals date back to the 18th Century The excellent technical equipment and huge stage have allowed vast spectacles to be performed at Drury Lane, including one I saw a few years ago, Miss Saigon, which had a helicopter land on the stage. The production showing when we visited was Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.

The excellent technical equipment and huge stage have allowed vast spectacles to be performed at Drury Lane, including one I saw a few years ago, Miss Saigon, which had a helicopter land on the stage. The production showing when we visited was Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.

Outside, the Stage Door

Outside, the Stage Door

Nearby, a memorial to Sir Augustus Harris (1825-1873)Actor, Dramatist and Impresario, manager of the Drury Lane

Nearby, a memorial to Sir Augustus Harris (1825-1873)Actor, Dramatist and Impresario, manager of the Drury Lane Our intrepid tour guide who did a wonderful job, but couldn't turn up any of the theatre's ghosts

Our intrepid tour guide who did a wonderful job, but couldn't turn up any of the theatre's ghosts

Published on April 22, 2016 00:00

April 21, 2016

HAPPY 90TH BIRTHDAY, YOUR MAJESTY

APRIL 21, 1926

George VI (then Duke of York) and Queen Elizabeth (then Duchess of York) with Princess Elizabeth, 1926

George VI (then Duke of York) and Queen Elizabeth (then Duchess of York) with Princess Elizabeth, 1926

Today Queen Elizabeth II becomes the first reigning British monarch to reach the age of 90.

The official celebration will be held May 12-15, 2016. For all the details, click here. Ninety years in ninety seconds: click here.

To see the Queen's birthday week's busy schedule, click here.

Why the Queen Is the Hardest Worker of Them All: click here.

Happy Birthday, Your Majesty.

Happy Birthday, Your Majesty.

George VI (then Duke of York) and Queen Elizabeth (then Duchess of York) with Princess Elizabeth, 1926

George VI (then Duke of York) and Queen Elizabeth (then Duchess of York) with Princess Elizabeth, 1926

Today Queen Elizabeth II becomes the first reigning British monarch to reach the age of 90.

The official celebration will be held May 12-15, 2016. For all the details, click here. Ninety years in ninety seconds: click here.

To see the Queen's birthday week's busy schedule, click here.

Why the Queen Is the Hardest Worker of Them All: click here.

Happy Birthday, Your Majesty.

Happy Birthday, Your Majesty.

Published on April 21, 2016 05:21

April 20, 2016

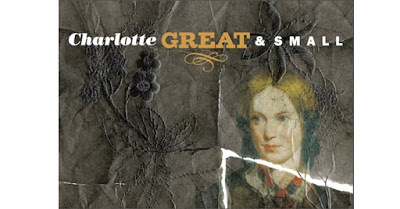

CHARLOTTE BRONTE BICENTENARY

Victoria here, wishing Happy 200th Birthday to Miss Bronte.

Portrait by George Richmond, 1850

Portrait by George Richmond, 1850Among many other events planned for the bicentenary, the Bronte Society and Bronte's home, the Haworth Parsonage Museum, are mounting an exhibition curated by Tracy Chevalier, here, entitled Charlotte Great and Small.

The National Portrait Gallery, London, will show Bronte items through August 15, 2016.

The Bronte Sisters, NPG

The Bronte Sisters, NPG

Charlotte, born April 21 1816, was the oldest of the Bronte sisters. Her most famous novel, Jane Eyre, was published in 1847; Charlotte used the pen name Currer Bell. One of the best-known works of English literature, it has been filmed many times with varying interpretations of both Jane and Rochester.

Personally, as a young person, I loved it, Then I came across an analysis which criticized the way in which Rochester dealt with his first wife, Bertha (madwoman in the attic); other women, including Jane; and how he and Jane cannot fulfill their love until he is maimed. Okay then...I changed my mind and I no longer care for it.

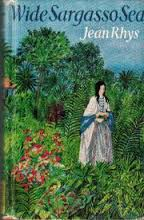

Plus I read a very interesting novel about the first Mrs. Rochester, her life in Jamaica, and her mental disturbances. Out in 1966, Wide Sargasso Sea written by Jean Rhys, is a disturbing story involving British plantation owning families, their slaves, and the dangerous, disease-laden life on the island. It also has been filmed.

A further chapter in my personal encounter with Jane Eyre came some years ago when Kristine and I visited Norton Conyers, a decaying country house in North Yorkshire. According to its website, "The discovery in 2004 of a blocked staircase connecting the first floor to the attics and clearly mentioned in the novel, aroused world-wide interest in Norton Conyers and confirmed it as a principal original of 'Thornfield Hall'."

Norton Conyers

Norton ConyersThe owners welcomed our little group, told us about the history of the very old house, probably dating back to before the 15th century. But it might be most famous for the story of how Charlotte Bronte, then a governess nearby, visited the house. For now lost reasons, a madwoman had been imprisoned in the attic, giving Charlotte ideas for the story of Jane Eyre.

They invited us to go upstairs and take a look, so we clambered up to the very dusty and cobwebby attic to see the place supposedly occupied by the madwoman.

spider heaven

spider heaven hip bath

hip bath more trunks

more trunksI recall there was a sort of cell-like room. The door had a small opening into which food could be passed for the poor resident, but I don't find a picture among my files.

According to reports, Norton Conyers is due to reopen soon after extensive renovations, changing the way it looked in my pictures! More information is here.

The gardens at Norton Conyers are beautiful, probably even more so because they have gone a little wild. The grounds are sometimes used for weddings.

Ken Weeks beside the conservatory

Ken Weeks beside the conservatory The Bronte Parsonage Museum

The Bronte Parsonage MuseumIrish-born Patrick Bronte (1777-1861), father of the six Bronte children, survived all of them, as well as his wife. They lived in Haworth, where he was curate of St, Michael's and All Angels Church. Set amidst the moors, the town even today has a dreary and dismal atmosphere. When I visited, I couldn't wait to get away. No wonder all the children suffered ill health and most died young.

Charlotte Bronte wrote poetry, several other novels, most notably Shirley (1849) and Villette (1853). Anne wrote as well, primarily The Tenant of Wildfell Hall. Emily is most famous for Wuthering Heights, another novel I once admired until I realized how abusive Heathcliff was.

After the deaths of all her siblings, Charlotte accepted a marriage proposal from Arthur Bell Nichols in 1854, but she lived only a short time after the wedding.

To cheer you, a few more pictures from Norton Conyers.

Published on April 20, 2016 00:00

April 18, 2016

THE PLAGUE VILLAGE OF DERBYSHIRE

Victoria here, reporting on a a wonderful book I read recently, chosen for one of my book groups. The author Geraldine Brooks, who has written several novels in addition to her career as a reporter in some of the world's most dangerous locales, gives us a fictionalized account of real events in the village of Eyam in Derbyshire in 1665-66.

The Year of Wonders by Geraldine Brooks

The Year of Wonders by Geraldine Brooksfrom the Amazon.com review:"Geraldine Brooks's Year of Wonders describes the 17th-century plague that is carried from London to a small Derbyshire village by an itinerant tailor. As villagers begin, one by one, to die, the rest face a choice: do they flee their village in hope of outrunning the plague or do they stay? The lord of the manor and his family pack up and leave. The rector, Michael Mompellion, argues forcefully that the villagers should stay put, isolate themselves from neighboring towns and villages, and prevent the contagion from spreading. His oratory wins the day and the village turns in on itself. Cocooned from the outside world and ravaged by the disease, its inhabitants struggle to retain their humanity in the face of the disaster. ... there is no mistaking the power of Brooks's imagination or the skill with which she constructs her story of ordinary people struggling to cope with extraordinary circumstances." --Nick Rennison, Amazon.co.uk

My photo from the neighborhood of Eyam some years ago

My photo from the neighborhood of Eyam some years agoA friend and I visited Eyam on a whirlwind tour of the region a few years ago. We were fascinated with the story of the community which quarantined itself to protect the neighboring villages and thus may have save the entire nation from a wider tragedy.

Derbyshire

DerbyshireThough I hadn't realized it at the time, Eyam Hall, below, actually dates from the years just after the plague ended.

Eyam Hall

Eyam HallThe National Trust operates programs at Eyam Hall and its gardens. Tours of the village and its museum are often scheduled.

Boundary Stone

Boundary StoneThe 3rd Earl of Devonshire supplied the village with food and other needs in exchange for lists and vinegar-soaked coins left on the stone by the villagers. It was assumed that the vinegar cleaned the coins of infection.

The Eyam parish church figures prominently in the novel.

The Eyam parish church figures prominently in the novel.A long list of books, articles, plays, even operas, deal with the Plague Village. I can enthusiastically recommend Year of Wonders as an admirable reading experience. Despite the desperate struggle of the villagers, there are illuminating and satisfying insights into character and growth, particularly for Anna Frith, the story's heroine. Not exactly a cheery novel, but one you will long remember.

Published on April 18, 2016 07:00

Kristine Hughes's Blog

- Kristine Hughes's profile

- 6 followers

Kristine Hughes isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.