Kristine Hughes's Blog, page 55

September 28, 2016

GUEST POST BY AUTHOR ABIGAIL DANE, PART TWO

GUEST POST BY AUTHOR ABIGAIL DANE, PART TWO

From Victoria: Abigail Dane, author of The Pirate and the Virgin, presents the second installment of her research notes. Welcome back, Abigail!

Battle of Worcester and its AftermathPart 2 of 3

Cromwell’s army took on its own grueling march—20 miles a day in extreme heat for seven days—to reach Ferrybridge on August 19th. Once again, the ever-pragmatic Worcester decided to align itself with the faction occupying it at the time. Cromwell’s New Model Army forces were, by then, 31,000 strong. Delaying the battle just long enough to build two pontoon bridges, Cromwell launched his attack against Charles on September 3rd—the one-year anniversary of the victory at Dunbar. With a 2:1 troop advantage stretching over a four-mile-long arc toward the town of Worcester, Cromwell was able to push back the Royalist forces, despite fierce fighting. The Royalist retreat turned into a trouncing after the capture of Fort Royal, a redoubt on a small hill to the southeast of the town. Among Charles’ army, 3,000 were killed and 10,000 captured. Some leaders were executed; some prisoners were sent to fight for Cromwell in Ireland; and around 8,000 Scots were deported to the New World and made to labor as indentured workers there. By contrast, the Parliamentarian casualties were estimated at a mere 200. A clear and complete rout for Cromwell. The Proscribed Royalist, 1651, by John Everett Millais, (1853)After the Battle of Worcester, a young Puritan woman helps a fleeing Royalist—Charles II himself?—to escape, by hiding him in a hollow tree.

The Proscribed Royalist, 1651, by John Everett Millais, (1853)After the Battle of Worcester, a young Puritan woman helps a fleeing Royalist—Charles II himself?—to escape, by hiding him in a hollow tree.

In the next day’s report of the victory to the Speaker of the House of Commons, Cromwell famously wrote: The dimensions of this mercy are above my thoughts. It is, for aught I know, a crowning mercy.

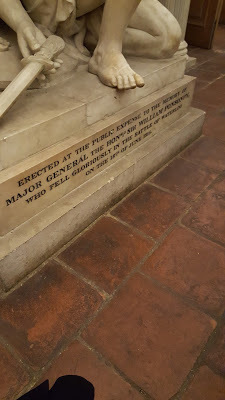

That last sentence, later inscribed on the plaque placed on the Sidbury Gate in Worcester, reads in full:

THE LAST BATTLE OF THE CIVIL WARWAS FOUGHT AT WORCESTER ON3rdSEPTEMBER 1651

IT IS FOR AUGHT I KNOWA CROWNING MERCYOLIVER CROMWELL

NEAR THIS SPOT IN THE CITY WALL STOODTHE SIDBURY GATE, WHICH WAS STORMEDBY THE PARLIAMENTARIAN TROOPS.ERECTED BY THE CROMWELL ASSOCIATIONAND WORCESTER CITY COUNCILWITH THE AID OF PUBLIC SUBSCRIPTION1993

Thus, the Royalist Army was destroyed and the bloody and costly conflict known as the “English Civil War” finally ended. As preacher Hugh Peters put it: “…at Worcester, where England’s sorrows began…they were happily ended.” Ironically, as a result of Charles II’s ill-fated decision to detour to Worcester, the final battle was fought just where the first battle had been fought on September 23, 1642—almost exactly nine years earlier. Unable to rally his troops and realizing his cause was lost, the thoroughly defeated monarch removed his armor, found a fresh mount and escaping as darkness fell, began a harrowing six-week-long flight. At one point, he hid from the patrols in an oak tree (now referred to as the “Royal Oak”) on the grounds of Boscobel House, as depicted in Millais’ painting, The Proscribed Royalist, 1651. A fearless actor, the fugitive king sometimes hid in plain sight; on one occasion striding through a crowd of Cromwell’s soldiers; on another boldly declaring to the blacksmith who was shoeing his horse: “If that rogue Charles Stuart is taken, he deserves to be hanged more than all the rest, for bringing in the Scots.” At a time when the average man was 5’6”, the fugitive king was 6’2” and swarthy. Being so distinctive and hard to disguise made him an exceptional target. The £1,000 reward on his head and the “death without mercy” decree for anyone found helping him made him a tempting one, as well.

Source: “Historical Notes: Battle of Worcester and its Aftermath,” in The Baron and the Lady, book two in the “Whitleigh series” by Abigail Dane. http://TransitionsUnlimited.biz, AbigailDaneRomance@gmail.org.

Abigail Dane

Abigail Dane

From Victoria: Abigail Dane, author of The Pirate and the Virgin, presents the second installment of her research notes. Welcome back, Abigail!

Battle of Worcester and its AftermathPart 2 of 3

Cromwell’s army took on its own grueling march—20 miles a day in extreme heat for seven days—to reach Ferrybridge on August 19th. Once again, the ever-pragmatic Worcester decided to align itself with the faction occupying it at the time. Cromwell’s New Model Army forces were, by then, 31,000 strong. Delaying the battle just long enough to build two pontoon bridges, Cromwell launched his attack against Charles on September 3rd—the one-year anniversary of the victory at Dunbar. With a 2:1 troop advantage stretching over a four-mile-long arc toward the town of Worcester, Cromwell was able to push back the Royalist forces, despite fierce fighting. The Royalist retreat turned into a trouncing after the capture of Fort Royal, a redoubt on a small hill to the southeast of the town. Among Charles’ army, 3,000 were killed and 10,000 captured. Some leaders were executed; some prisoners were sent to fight for Cromwell in Ireland; and around 8,000 Scots were deported to the New World and made to labor as indentured workers there. By contrast, the Parliamentarian casualties were estimated at a mere 200. A clear and complete rout for Cromwell.

The Proscribed Royalist, 1651, by John Everett Millais, (1853)After the Battle of Worcester, a young Puritan woman helps a fleeing Royalist—Charles II himself?—to escape, by hiding him in a hollow tree.

The Proscribed Royalist, 1651, by John Everett Millais, (1853)After the Battle of Worcester, a young Puritan woman helps a fleeing Royalist—Charles II himself?—to escape, by hiding him in a hollow tree.In the next day’s report of the victory to the Speaker of the House of Commons, Cromwell famously wrote: The dimensions of this mercy are above my thoughts. It is, for aught I know, a crowning mercy.

That last sentence, later inscribed on the plaque placed on the Sidbury Gate in Worcester, reads in full:

THE LAST BATTLE OF THE CIVIL WARWAS FOUGHT AT WORCESTER ON3rdSEPTEMBER 1651

IT IS FOR AUGHT I KNOWA CROWNING MERCYOLIVER CROMWELL

NEAR THIS SPOT IN THE CITY WALL STOODTHE SIDBURY GATE, WHICH WAS STORMEDBY THE PARLIAMENTARIAN TROOPS.ERECTED BY THE CROMWELL ASSOCIATIONAND WORCESTER CITY COUNCILWITH THE AID OF PUBLIC SUBSCRIPTION1993

Thus, the Royalist Army was destroyed and the bloody and costly conflict known as the “English Civil War” finally ended. As preacher Hugh Peters put it: “…at Worcester, where England’s sorrows began…they were happily ended.” Ironically, as a result of Charles II’s ill-fated decision to detour to Worcester, the final battle was fought just where the first battle had been fought on September 23, 1642—almost exactly nine years earlier. Unable to rally his troops and realizing his cause was lost, the thoroughly defeated monarch removed his armor, found a fresh mount and escaping as darkness fell, began a harrowing six-week-long flight. At one point, he hid from the patrols in an oak tree (now referred to as the “Royal Oak”) on the grounds of Boscobel House, as depicted in Millais’ painting, The Proscribed Royalist, 1651. A fearless actor, the fugitive king sometimes hid in plain sight; on one occasion striding through a crowd of Cromwell’s soldiers; on another boldly declaring to the blacksmith who was shoeing his horse: “If that rogue Charles Stuart is taken, he deserves to be hanged more than all the rest, for bringing in the Scots.” At a time when the average man was 5’6”, the fugitive king was 6’2” and swarthy. Being so distinctive and hard to disguise made him an exceptional target. The £1,000 reward on his head and the “death without mercy” decree for anyone found helping him made him a tempting one, as well.

Source: “Historical Notes: Battle of Worcester and its Aftermath,” in The Baron and the Lady, book two in the “Whitleigh series” by Abigail Dane. http://TransitionsUnlimited.biz, AbigailDaneRomance@gmail.org.

Abigail Dane

Abigail Dane

Published on September 28, 2016 00:00

September 23, 2016

A TOUR GUIDE IN ENGLAND: DAY FOUR - PART THREE: DINNER AT SIMPSON'S IN THE STRAND

You may recall that in Part One of our Day Four post Diane, Jo and I had gone on a London Walk of the Covent Garden area that included a stop at Simpson's in the Strand restaurant. I told you then that there would be more about this venerable and much loved eatery to come and so there shall be. Now.

From the Simpson's in the Strand website:

Originally opened in 1828 as a chess club and coffee house - The Grand Cigar Divan - Simpson's soon became known as the "home of chess", attracting such chess luminaries as Howard Staunton the first English world chess champion through its doors. It was to avoid disturbing the chess games in progress that the idea of placing large joints of meat on silver-domed trolleys and wheeling them to guests' tables first came into being, a practice Simpson's still continues today. One of the earliest Master Cooks insisted that everything in the restaurant be British and the Simpson's of today remains a proud exponent of the best of British food. Famous regulars include Charles Dickens, George Bernard Shaw, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (and his fictional creation, Sherlock Holmes), Benjamin Disraeli and William Gladstone.

Known for it's joints of beef wheeled tableside on huge, steel trollies, Simpsons has always been a favourite of those with a literary bent. From Wikipedia : In E. M. Forster's Howards End , Henry Wilcox is a devotee of Simpson's. P. G. Wodehouse devoted several paragraphs of Something New to the restaurant, and in his novel Psmith in the City , his two heroes dine there: "Psmith waited for Mike while he changed, and carried him off in a cab to Simpson's, a restaurant which, as he justly observed, offered two great advantages, namely, that you need not dress, and, secondly, that you paid your half-crown, and were then at liberty to eat till you were helpless, if you felt so disposed, without extra charge." Simpson's is also featured in Wodehouse's "Cocktail Time" as the restaurant that one of the characters, Cosmo Wisdom, chooses to lunch at after leaving Prison. Simpson's also features in the Sherlock Holmes stories. Watson joins Holmes there during the story "The Illustrious Client" the detective is sitting "looking down at the rushing stream of life in the Strand."

The window in the upstairs bar at Simpsons. Possibly the window Holmes himself had gazed out from.

The window in the upstairs bar at Simpsons. Possibly the window Holmes himself had gazed out from. So you see, it's not unusual that I should have chosen Simpson's as the scene of this evening's dinner party, for a party it was to be and, as Diane and I had some time before the rest of my guests arrived, we headed upstairs to Knight's Bar for a cocktail. Wodehouse would no doubt have approved.

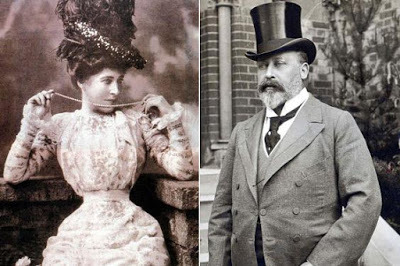

Literary connections aside, Simpson's has also been the site of a Royal intrigue or two, the most widely known being that Simpson's, this very bar no less, was used by King Edward VII to secretly meet with his mistress, Lillie Langtry.

Lillie Langtry and King Edward VII

Lillie Langtry and King Edward VII

Diane and I took a table by the window, which gave us a direct view of the table and mural, above. This was Edward VII's table, as it stands by itself in a corner alcove, away from prying eyes. The mural disguise's a hidden door, through which the lovely Lilly would slip in order to sit beside her Royal lover.

And so Diane and I sat with our cocktails and waited for the rest of the party to arrive. Can you guess who they were? A member of the Royal Family, perhaps? Much better - my guests this evening were some of the fabulous guest speakers and guides who will be part of Number One London's 2017 Tours.

From left to right: Diane Perkins (Diane Gaston), Kristine Hughes Patrone, Ian Fletcher, Nicola Cornick and Melanie Hilton (Louise Allen)

Oysters, dinner, wine and a grand time were had by all!

Full Details Regarding Number One London's

2017 Tours Coming Soon!

Published on September 23, 2016 23:30

September 21, 2016

GUEST POST BY AUTHOR ABIGAIL DANE, PART ONE

From Victoria: Abigail Dane has undertaken an ambitious project, a trilogy, of which the first book is now available. Welcome, Abigail!

Author Abigail Dane

Author Abigail Dane

My books are set during the English Civil War. I have immersed myself in the history of the period, and I can make the case that this conflict changed England forever and set the stage for all that followed—in England and in the colonies of the Indies and America, as well. In brief, as much as Henry VIII’s war against Catholicism and as much as Luther’s calls for reformation of the church, Charles’ claims of “the divine right of kings” and Cromwell’s radical Puritanism forged the times, creating the spurt in colonization of the New World and fueling calls for religious freedom and independence that followed. Basically, WITHOUT THIS, NEVER THAT.

The Battle of Worcester (September 3, 1651) ended the third phase of the long and costly English Civil War conflict (1642-1651). The exiled Charles II (then the crowned King of Scotland and son of the beheaded Charles I) invaded England with 16,000 troops, mostly Scotsmen. They originally intended to storm London and retake the throne, but Cromwell learned of the invasion and sent a superior troop (2:1) to meet them. The armies met at Worcester and the fight ended with a mere 200 of Cromwell’s troops dead, compared to 3,000 dead and 10,000 taken prisoner from Charles’ forces. In the aftermath, Cromwell spent six frantic weeks scouring the countryside for the fugitive king, and Charles spent six perilous weeks evading capture in a bid to make his way to France.

I believe the following paragraph, from the “Prologue” of my first novel in the series, The Pirate and the Virgin, captures the spirit of the conflict between Charles I and Cromwell:

To the bloody end in 1649, Charles held to his claim of divine appointment and divine right to rule as he willed. No need to consult Parliament or the people since he, the Sovereign appointed by God, was responsible only to God for his actions. Charles’ stubbornness about this was outmatched only by Cromwell’s implacable belief that kings served the people and, thus, served at the will of the people. In the end, the king submitted to the axe rather than concede his principles, and Cromwell laid the king to the axe rather than concede his.

Battle of Worcester and its AftermathPart 1 of 3

The people in the neighborhood appeared so ignorant and careless at Worcester that I was provoked and asked “And do Englishmen so soon forget the ground where liberty was fought for?” Tell your neighbors and your children that this is holy ground, much holier than that on which your churches stand. All England should come in pilgrimage to this hill, once a year. —John Adams, April 1786

This admonition was written by John Adams on the occasion of his visit, in company of Thomas Jefferson, to Fort Royal Hill—scene of the Battle of Worcester, which ended the English Civil War. Adams was deeply moved by the place, and deeply disappointed that locals knew so little about the battle and its significance. If Adams’ words sound a bit like a lecture, that may be because he intended them to be just that. One assumes he might have been thinking of the recently-concluded American Revolution, which ended at another bit of “holy ground” and pilgrimage site: namely Yorktown, scene of Cornwallis’ surrender to the Americans on October 19, 1781. The Second English Civil War—or perhaps more accurately the second phase of the English Civil War—ended with the execution of King Charles I at Whitehall, London, on a cold and blustery January 30th 1649. Two years later, on September 3rd, 1651, the third and final phase of this “war without an enemy” ended when Cromwell’s army routed Charles II and his forces at Fort Royal Hill in Worcester.

The Battle of Worcester, 3 September 1651by Thomas Woodward (1801-1852)Worcester City Museum

The Battle of Worcester, 3 September 1651by Thomas Woodward (1801-1852)Worcester City Museum

Charles, while in exile as King of Scotland, had rounded up a force of 16,000 men—mostly Scots—and raced toward London to retake the British throne. His had army trekked 150 miles in a week, finally earning a bit of rest on August 8th. Charles had decided against a direct march on London, instead detouring to the Severn Valley in hopes of recruiting greater numbers for his army from this area where support for his father had been so strong. Perhaps because his was mostly a foreign army, and likely because people were simply tired of war after so long, the level of support fell far short of his expectations. Pressing on despite this, Charles II arrived in Worcester on August 22nd, prepared for battle after five days of rest.

That delay would prove fatal.

Source: “Historical Notes: Battle of Worcester and its Aftermath,” in The Baron and the Lady, book two in the “Whitleigh series” by Abigail Dane. http://TransitionsUnlimited.biz, AbigailDaneRomance@gmail.org.

Abigail Dane's post continues next week.

Author Abigail Dane

Author Abigail DaneMy books are set during the English Civil War. I have immersed myself in the history of the period, and I can make the case that this conflict changed England forever and set the stage for all that followed—in England and in the colonies of the Indies and America, as well. In brief, as much as Henry VIII’s war against Catholicism and as much as Luther’s calls for reformation of the church, Charles’ claims of “the divine right of kings” and Cromwell’s radical Puritanism forged the times, creating the spurt in colonization of the New World and fueling calls for religious freedom and independence that followed. Basically, WITHOUT THIS, NEVER THAT.

The Battle of Worcester (September 3, 1651) ended the third phase of the long and costly English Civil War conflict (1642-1651). The exiled Charles II (then the crowned King of Scotland and son of the beheaded Charles I) invaded England with 16,000 troops, mostly Scotsmen. They originally intended to storm London and retake the throne, but Cromwell learned of the invasion and sent a superior troop (2:1) to meet them. The armies met at Worcester and the fight ended with a mere 200 of Cromwell’s troops dead, compared to 3,000 dead and 10,000 taken prisoner from Charles’ forces. In the aftermath, Cromwell spent six frantic weeks scouring the countryside for the fugitive king, and Charles spent six perilous weeks evading capture in a bid to make his way to France.

I believe the following paragraph, from the “Prologue” of my first novel in the series, The Pirate and the Virgin, captures the spirit of the conflict between Charles I and Cromwell:

To the bloody end in 1649, Charles held to his claim of divine appointment and divine right to rule as he willed. No need to consult Parliament or the people since he, the Sovereign appointed by God, was responsible only to God for his actions. Charles’ stubbornness about this was outmatched only by Cromwell’s implacable belief that kings served the people and, thus, served at the will of the people. In the end, the king submitted to the axe rather than concede his principles, and Cromwell laid the king to the axe rather than concede his.

Battle of Worcester and its AftermathPart 1 of 3

The people in the neighborhood appeared so ignorant and careless at Worcester that I was provoked and asked “And do Englishmen so soon forget the ground where liberty was fought for?” Tell your neighbors and your children that this is holy ground, much holier than that on which your churches stand. All England should come in pilgrimage to this hill, once a year. —John Adams, April 1786

This admonition was written by John Adams on the occasion of his visit, in company of Thomas Jefferson, to Fort Royal Hill—scene of the Battle of Worcester, which ended the English Civil War. Adams was deeply moved by the place, and deeply disappointed that locals knew so little about the battle and its significance. If Adams’ words sound a bit like a lecture, that may be because he intended them to be just that. One assumes he might have been thinking of the recently-concluded American Revolution, which ended at another bit of “holy ground” and pilgrimage site: namely Yorktown, scene of Cornwallis’ surrender to the Americans on October 19, 1781. The Second English Civil War—or perhaps more accurately the second phase of the English Civil War—ended with the execution of King Charles I at Whitehall, London, on a cold and blustery January 30th 1649. Two years later, on September 3rd, 1651, the third and final phase of this “war without an enemy” ended when Cromwell’s army routed Charles II and his forces at Fort Royal Hill in Worcester.

The Battle of Worcester, 3 September 1651by Thomas Woodward (1801-1852)Worcester City Museum

The Battle of Worcester, 3 September 1651by Thomas Woodward (1801-1852)Worcester City MuseumCharles, while in exile as King of Scotland, had rounded up a force of 16,000 men—mostly Scots—and raced toward London to retake the British throne. His had army trekked 150 miles in a week, finally earning a bit of rest on August 8th. Charles had decided against a direct march on London, instead detouring to the Severn Valley in hopes of recruiting greater numbers for his army from this area where support for his father had been so strong. Perhaps because his was mostly a foreign army, and likely because people were simply tired of war after so long, the level of support fell far short of his expectations. Pressing on despite this, Charles II arrived in Worcester on August 22nd, prepared for battle after five days of rest.

That delay would prove fatal.

Source: “Historical Notes: Battle of Worcester and its Aftermath,” in The Baron and the Lady, book two in the “Whitleigh series” by Abigail Dane. http://TransitionsUnlimited.biz, AbigailDaneRomance@gmail.org.

Abigail Dane's post continues next week.

Published on September 21, 2016 00:00

September 17, 2016

SCOTLAND BOUND

I loathe telling "lay" people that I know anything about British history. Invariably, they'll enthuse about Henry VIII or the medieval period and I then have to explain that my interest is confined to roughly the time period from 1750-1950. I freely admit that I know very little, almost nothing, about anything that transpired prior to that. I don't mind in the least admitting what I don't know. Take Scotland, for instance. I know nothing about Scotland other than it's where they drink whiskey, which I hate, and eat shortbread, which I love. To be honest, almost all I know about Scotland is that which involves Queen Victoria. Which is why I have enlisted the help of my old pal, Sue Ellen Welfonder, to help me plan Number One London's Scottish Castles and Palaces Tour. She has been a gold mine of information and suggestions and will be joining me on my trip to Scotland in September to scout out locations for the tour. Knowing my great affection for Queen Victoria, Sue Ellen suggested that we go to the Ardverikie Estate.

"Since we'll be in the area and passing right by, we can stop and see the Ardverikie Estate when we're in Scotland," Sue Ellen proposed.

"Yeah. Whatever you want to do. Scotland is all you."

"It's really pretty. It sits on the shores of Loch Laggan."

"Ah."

"It should interest you. Queen Victoria considered it when she was looking for a place in Scotland, but decided on Balmoral instead," Sue Ellen elaborated in an effort to garner a bit more enthusiasm from me.

"Oh. Right."

"There were too many midges about when she visited and they put her off the property."

"Uh huh."

"So now, instead of being a Royal residence, Ardverikie has to settle for being Glenbogle."

"Wait . . . What?"

"There's this Scottish television show called Monarch of the Glen and . . . "

"Are you kidding me? Glenbogle? We're actually going to Glenbogle?"

"You mean you know Monarch of the Glen?"

"Know it? I love Monarch of the Glen. I've seen every episode. Hector, Archie, Julian Fellowes! Can we go inside? Can we?"

"No! It's a private house now, but we can walk over the bridge by the gate house and follow a trail that will bring us up fairly close to the house."

"Oh, I can hardly stand it!"

"Well, who knew you'd be so excited to see something Scottish," Sue Ellen said.

Who knew, indeed. It appears I know more about Scotland than I'd first thought. Hoot man, I cannae wait to get there! We're UK bound on September 18th, stopping in London for a few days before flying on to Edinburgh. You can stay up to date with all of our travels on my Facebook Page.

Do you have a favourite place in Scotland? Somewhere that speaks to your heart? Somewhere you long to visit? Let us know by leaving a comment here.

Published on September 17, 2016 23:00

September 13, 2016

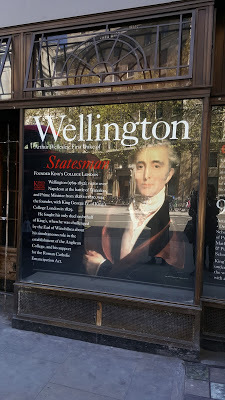

ONCE AGAIN WEDNESDAY: THE DEATH OF WELLINGTON AT WALMER

The Duke of Wellington died at Walmer Castle on September 14, 1852

From The History of Walmer and Walmer Castle by Charles Robert Stebbing Elvin (1894)The Duke of Wellington was Lord Warden for nearly four and twenty years, and during all that time rarely missed coming to Walmer after the prorogation of Parliament, staying usually till about the middle of November; and, before leaving for Strathfieldsaye, generally held at Dover a Court of Lodemanage, to discuss and settle the affairs of the Cinque Ports' pilots.

For some years before his death, the Duke had been in failing health. Seated in the drawing-room in his favourite armchair, he would often, after dinner, take a newspaper in one hand and a candle in the other, and fall asleep while reading in this dangerous position, to the great anxiety of his friend and companion, Mr. Arbuthnot. The end came suddenly at last. The Duke was accustomed to rise early, but, on September 14th, 1852, when his valet called him as usual at six o'clock, he found the Duke particularly drowsy, and thought it best to leave him undisturbed for an hour longer. He therefore withdrew, but remained within hearing. It was fortunate he did so, for soon after he was alarmed at hearing groans from the Duke's room, and on re-entering was requested to send for Dr. Hulke of Deal, who came, prescribed some simple remedies, and, seeing nothing serious in the Duke's condition, departed. Shortly after this, however, the Duke became much worse, and messages were despatched for further help. On the return of Dr. Hulke with his son and Dr. McArthur, they found his Grace breathing laboriously, unconscious, and very restless. To assist respiration he was raised and put into his easy chair, where for a time he breathed more freely; but the end was very near, and at five and twenty minutes past three he expired. A message had meanwhile been sent to London for Dr. Williams, who only arrived in time to find the mortal remains of his illustrious patient laid out upon his little camp-bed.

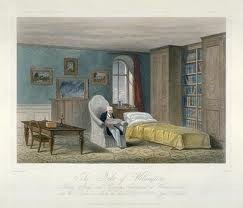

The Union Jack now drooped at half-mast high upon the castle ramparts; announcing to the world that the Iron Duke, the nation's idol was no more. The body of the departed hero remained at Walmer Castle until the eleventh of November, in the irregularly-shaped room shown in the engraving; which still retains the name of "The Duke's Room." The scene at Walmer, subsequent to the removal, cannot be better described than in the following extract from a contemporary record, which conveys a most graphic idea of all the solemn proceedings of this time :—" In the small irregularly shaped death-chamber lay the body of the Duke, inclosed in an outer coffin covered with crimson velvet, and with handles and funeral decorations richly gilt. On the lid, near the head, rested the ducal coronet, and beyond it the pall, gathered back, to give visitors a complete view. The coffin rested on a low stand, covered with black cloth, round which candelabra with huge wax lights and plumes of feathers were arranged. The walls and roof of the small apartment were, of course, hung with black cloth, the single deep-recessed window closed, and candles, reflected against silver sconces, barely relieved the gloom of the sombre display. Visitors entering at one door passed by the end of the coffin, and then out at another without interruption. The ante-chambers and corriders were also darkened, hung with black, and lighted with candles placed at intervals on the side walls.

"The first day for admission of the public was Tuesday (Nov. 9th). Through the low strong archway of the entrance the visitors passed, first, along the curved glass-covered passage, then through the dimly lighted anterooms into the chamber of death, and then along corridors and down staircases and across the garden on to the beach. All the way at a few paces distance from each other on either hand, the guard of honour of the Rifle Brigade were placed, each man with his arms reversed, and leaning in a sorrowful attitude on his musket. Along the beach, as far as the eye could reach towards Deal, a long train of visitors dressed in mourning passed and repassed throughout the day, while from greater distances conveyances arrived and took their departure in quick succession."

The stream of visitors continued throughout the Tuesday, and until four o'clock in the afternoon of the following day; during which time upwards of nine thousand people are said to have visited the chamber of the late Duke to witness the lying in state. But about 7 p.m. on Wednesday (Nov. 10th), the body was removed to Deal Station, en route for London, under an escort of about 150 men of the Rifle Brigade, commanded by Colonel Beckwith, and attended by mourning coaches in which were seated the Duke's eldest son and successor, Lord Arthur Hay, Captain Watts, Mr. Marsh of the Lord Chamberlain's office, and others.

The Duke of WellingtonAs the funeral cortege prepared to leave the grounds, the solemn booming of the minute-guns resounded from the castle walls; while the wind brought back the echo from Deal and Sandown, where the like honour was paid to the memory of the deceased. Down the "sombre avenue," lighted by the lurid glare from the flambeaux with which a body of men led the way, and through the silent crowds who lined the road undeterred by chill darkness of a November night, winded the slow procession; moving with measured tread, until at length they reached Deal Station; the melancholy march of a mile and three-quarters having occupied no less than one hour and a half. There they were awaited by Mr. James Macgregor, M.P., the chairman of the South-Eastern Railway Company; and the hearse having been transferred to a truck, the journey onward to London was resumed at a quarter past nine.

The Duke of WellingtonAs the funeral cortege prepared to leave the grounds, the solemn booming of the minute-guns resounded from the castle walls; while the wind brought back the echo from Deal and Sandown, where the like honour was paid to the memory of the deceased. Down the "sombre avenue," lighted by the lurid glare from the flambeaux with which a body of men led the way, and through the silent crowds who lined the road undeterred by chill darkness of a November night, winded the slow procession; moving with measured tread, until at length they reached Deal Station; the melancholy march of a mile and three-quarters having occupied no less than one hour and a half. There they were awaited by Mr. James Macgregor, M.P., the chairman of the South-Eastern Railway Company; and the hearse having been transferred to a truck, the journey onward to London was resumed at a quarter past nine. "Funeral of the Duke of Wellington the funeral car passing the archway at Apsley House"

"Funeral of the Duke of Wellington the funeral car passing the archway at Apsley House" On arriving at the Bricklayers' Arms station, the hearse with the coffin was removed to Chelsea Hospital, under an escort of the 1st Life Guards; and there the remains of the Duke continued to lie in state till removed for the Grand State Funeral which took place on the following Thursday, November 18th.

In 1861, shortly after the appointment of Lord Palmerston (as Lord of the Cinque Ports), several articles were removed from (the Duke of Wellington's room at Walmer) to Apsley House, with the consent of Lord Dalhousie's executors, in consequence of a threatened sale by auction; but these have all been recently restored, through the generosity of the present Duke of Wellington, as related further on; and "The Duke's Room" is once again as it used to be, even to the yellow moreen curtains and the orignal bedding and chair-cover. The bookshelves have, however, been wisely covered with glass doors, and so converted into a cabinet, in which many articles of interest are kept under lock and key; including the Duke's set of his own printed despatches, in twelve vols., the first volume of which has been despoiled of its title-page by some thief, or thievish collector, for the sake no doubt of the autograph. This cabinet also contains, among other things, two pairs of "Wellington" boots, and a volume of Statutes relating to the Cinque Ports, of the date of 1726. The latter was presented to the Duke of Wellington by Lord Mahon, and contains the autograph of each. One pair of the "Wellingtons," described in the schedule of heirlooms as a pair of "Field Marshall's 'Wellington' boots," are believed to be the same that were worn by the Duke at the Battle of Waterloo. The famous camp-bedstead has now a green velvet coverlet, presented by the Countess of Derby in 1893.

The engravings in this room include portraits of Mrs. Siddons, Mr. Burke, and Lord Onslow, as well as the Duke's print of the Chelsea pensioners reading the Gazette announcing the victory at Waterloo; and in the adjoining dressing-room, is a curious piece of work, made by the Duke's house carpenter and shown at the Exhibition in 1851, being the representation of Strathfieldsaye House, in the form of a picture, composed it is said of 3,500 pieces of wood. The Duke of Wellington thought so much of this picture that it used to hang during his lifetime in the dining-room.

Published on September 13, 2016 23:00

September 9, 2016

A TOUR GUIDE IN ENGLAND: DAY 4 - PART TWO

Saying goodbye to Jo Manning after our lunch at the Duke of Wellington pub, Diane and I walked down the Strand to Somerset House, where we walked out to the terrace at the back and gazed for a while upon the Thames.

Leaving Somerset House, Diane and I undertook another aimless walk round London - our favourite activity.

"What's that church up ahead?" Diane asked after a while.

I looked at the church as we approached. "No idea."

"No idea?" she asked, sounding surprised.

"Nope. Afraid not. I really don't know this part of London like the back of my hand, as I dare say I do in Mayfair and the West End. This is all pretty much virgin territory for me, except for Twinings. I know where Twinings is. But I do know how we can figure out what church this is."

"How?"

"We'll read the sign."

After stopping in to Twinings to buy copious amount of Lapsang Souchong tea, we headed towards St. Paul's Cathedral.

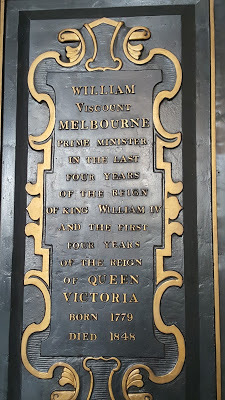

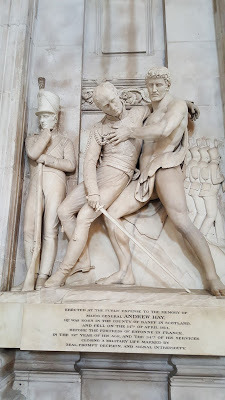

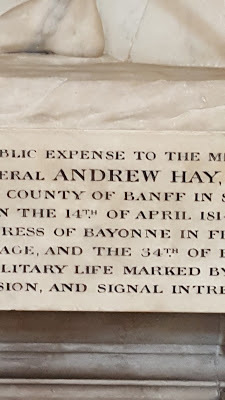

In case there was any doubt, our main reason for visiting St. Paul's was to pay our respects to the Duke of Wellington, but we took the time to visit most of the other war graves, as well.

Once we'd had our fill, we once more headed outside into the breach and soon found ourselves before the Cockpit Tavern in Blackfriars.

"Where are we?" asked Diane.

"Well, as luck would have it, we're at the Cockpit. Let's have a drink."

"Okay, but where are we?"

"We're in London. More than that I can't tell you."

"You mean you don't know where we are?"

"We're in London and the River is that way. I kinda know where we are. Ish. I do know that the bar has to be this way," I said, pulling her after me through the front door.

Not only did the Cockpit have liquor, they also had a sense of humour.

Once again, a good time was had by all.

Part Three Coming Soon!

Published on September 09, 2016 23:00

September 6, 2016

SOMETHING I'VE NEVER DONE BEFORE BY GUEST BLOGGER MARILYN CLAY

Actually, with my new Regency Mystery release, Murder at Morland Manor, there are two “somethings” I have never done before. One, even though I’ve written more than twenty books, I had never before written an entire novel using first person viewpoint and two, I had never before written a Regency-set mystery. Not sure “why” I wanted to write a mystery set in the Regency period, it was just an idea that had been churning around in my mind for a while.

So, when I finished writing The Wrong Miss Fairfax, a traditional Regency Romance released in print and e-book in January 2016, which I also wrote in first person although I switched back and forth from the heroine to the hero and found it a lot of fun, I was already in that mind-set so I began my Morland Manor mystery the same way except that I stayed exclusively in the heroine’s viewpoint. Partly because there is no hero, per se, although Juliette, being young and attractive, does notice the gentlemen in the story and she does find one more appealing than the others, still there is no real hero in this Regency-set murder mystery.

Back when I first started writing, I remember it helped me to “get into my character’s head” if I first wrote out her internal dialog in first person and then when I felt comfortable with her (or his) feelings and emotions I would rewrite everything in third person. Now that I’ve completed two books in first person, I find I like the discipline. With first person your main character must be in every scene and you cannot “show” or “reveal” anything to the reader that your character isn’t looking at, or thinking about. To maintain that degree of focus as a writer can sometimes be a challenge since you have to figure out ways that she can “learn” something that did not happen while she was right there on the premises. With third person, and certainly with omniscient viewpoint, you (the author) can take your readers all over the place. With first person, the viewpoint is by definition limited. However, a pitfall for the writer is to think it’s okay to reveal every little thing she is thinking about, but you have to remember to sift through her random thoughts and choose only those that apply to the situation at hand and that move the story forward.

My next choice as I began to set up my Regency-set mystery was to decide “when”, as in exactly what year, the story would take place. Because I knew that this plot, meaning the murder and solving the crime, would happen within a scant fortnight, I did not want to choose a year in which a lot was happening in England politically. I did not want political events, such as the war, or the death of a royal, to overshadow the heightened drama and emotional angst that the murder itself would create for my characters, i.e. I did not want anything to distract anyone, so I chose a two-week period in the fall of 1820.

To be certain that this was the exact time period I wanted to go with, I consulted my stack of back issues of The Regency Plume Newsletter, which I must say still come in handy even though the publisher (oh wait, that’s me!) is no longer publishing. I re-read every Regency Plume article containing information that would add details and authenticity to my story, such as how the Bow Street Runners operated, the English judicial system, who was sent to what prison and exactly where it was located, and more. I needed to know what happened when one merely suspecteda person of having committed a crime, how to go about having them arrested and what happened to the criminal afterward such as, where was a suspect held over for trial? Exactly who made the arrest? In a small village in the English countryside was there a great difference between a constable and a magistrate? Would there even be a magistrate in, or nearby, a small village? And what about a medical examiner? Would one of them also be called in, and what did he do?

I also went on-line and looked up a period calendar for October 1820 so when I noted the date at the beginning of a chapter, I would be putting in the correct day, such as Saturday 14 October and so on. In some cases, little details like these don’t stump a writer until she comes face-to-face with them while she’s writing the book, but then, you have to abandon your story while you go in search of the answer. I like to anticipate what sort of information I’ll need and have the answers at my fingertips before I even start writing. Of course, I never think of everything, but I do my best. And, having all those little notes I write to myself scattered here and there amid back issues of The Regency Plume, which are generally strewn across several thick books open to a particular page containing information I anticipate needing, does make for a pretty messy desk, but . . . I live with it. And when I finish the book, I sort through everything so at least when I’m ready to start another book, I begin with fresh notes that apply only to the new story.

For this particular book, Murder at Morland Manor, I knew I would have at least five young ladies at the house party at Morland Manor who would be from aristocratic families, so I wanted to be certain that I got their titles correct and also those of their parents. You’d think that by now, this would not be an issue, but hey, I’m an American and much about the British title system is still Greek to me, so I also dug out those Regency Plume articles written by the late Jo Beverley and other fabulous Regency authors on English titles and made my choices. In the list of characters that I put at the beginning of my book, I included little notes for readers on English titles and why different ranks were addressed in the manner they are.

I also chose personalities and physical characteristics for each of the young ladies and attempted to give them and their lady’s maids enough differences that it would not be difficult for readers to keep the characters straight. So, that meant no two names that began with the same letter; not all of the girls are blonde with blue eyes, or all petite, or even all pretty. I admit I was half way through writing the book before I quit consulting my cheat sheet on the characters and remembered who was who.

The next thing I had to decide was the age of my lead character Juliette Abbott. Since I intend this to be an on-going series, I knew Juliette would be solving a number of murders so I decided to have her start out young and age as each story unfolds, rather than have her be in her twenties in the first book and “on the shelf” by book three or four. At the end of Murder at Morland Manor Juliette is on her way . . . oh, I guess I shouldn’t give away the ending of the story. Anyhow . . . the next book in the series picks up right where this one leaves off. I hope you’ll want to follow along and find out what crime Miss Juliette Abbott is obliged to solve next.

I will tell you this much, the next story in the Juliette Abbott Regency Mystery Series takes place in London. In the meantime, you can become acquainted with Juliette Abbott in Murder at Morland Manor available from most online e-book sites and also in print here or from Amazon.

If you’d like to read more about my other Regency romance novels, or my Colonial American historical suspense novels, DANGEROUS DECEPTIONS or DANGEROUS SECRETS, both published a few years ago in hardcover, or about my BETSY ROSS: ACCIDENTAL SPYstory, please visit my author website here. Of course, all these titles and more are also available on Amazon and other online e-book sites.

Happy Reading everyone!

Marilyn Clay

Published on September 06, 2016 23:00

September 3, 2016

A TOUR GUIDE IN ENGLAND: DAY 4 - PART ONE

On day four, Diane and I met our pal author Jo Manning in Covent Garden and went along on a London Walk of the area. I adore London Walks, the company has engaging guides and enough walks on a variety of topics so wide ranging that absolutely everyone who visits London can find a walk that will not only interest, but also delight. Because the Covent Garden area will feature on a few upcoming Number One London Tours, I wanted to make sure that my knowledge of the area was up to snuff.

Covent Garden has a fascinating history, spanning centuries, and there is so much to see, if one knows where to look, point in fact the surviving herbalist's sign below. From flower markets a la My Fair Lady to Harris's List of Covent Garden Ladies , the mind boggles at all who have trod here.

If you're in the area, do make time to explore the garden behind St. Paul's Church, also known as The Actor's Church

The tour included areas outside of Covent Garden, including the Strand, where we saw the Coal Hole. I was first introduced to the Coal Hole decades ago by Dr. David Parker, then curator of the Dicken's House Museum. Tip - don't visit right at five o'clock as the place is packed then with City types wanting their well earned cocktail at the end of the day. The place is packed with atmosphere, like something right out of a Dicken's novel, so it really is worth a visit.

We also passed The Savoy Hotel, which has been on my "to do" list for the past five or six trips to London, but which I still haven't found the time to visit. I'm dying to suss out the place and to have at least one cocktail at their bar.

The tour also included a stop into Simpson's in the Strand, the venerable restaurant venue which has figured large in both London and Royal history. But more on that later . . . . .

The tour did provide me with a new shortcut from the Strand through to Covent Garden, so that's alright. If only I remember where it is.

We took in the Oscar Wilde memorial beside St. Martin's in the Field on our walk. The statue is entitled A Conversation With Oscar Wilde. You can read about it here.

When the walking tour ended, Jo, Diane and I went for lunch to the Duke of Wellington Pub in the Strand. You may recall that Victoria and I had lunch there during the Duke of Wellington Tour with Marilyn, Diane's sister. And I've posted about my meal there with with Hubby - delicious lamb shanks. I realize that it all sounds rather incestuous, but the important bit is that the food is wonderful.

A grand time was had by all!

Published on September 03, 2016 00:00

August 30, 2016

ONCE AGAIN WEDNESDAY: Mary Anne Clark by Jo Manning - Part Four

Mrs M.A.Clarke, as drawn & engraved by C.Williams, published Feb 25, 1809

by S.W.Fores, 50 Piccadilly

In the above print, titled “Committee of Inquiry” (available for £180 @Grosvenor Prints in Hampton, Middlesex), the descriptive text from Grosvenor Prints has Mrs. Clarke “standing in the lobby of the House of Commons, a section of which is seen through the partly open door: the corner of three tiers of empty benches and the gallery, with a strip of the Speaker's chair, showing his right elbow.” Mrs. Clarke wears a blue pelisse over a simple white dress; on her head rests a straw bonnet with a lace veil. With her left hand she raises the hat’s veil from her face. The very, very large object on her right hand is a fur muff. Again, as per the description, “She is elegant, alluring, and assured.”

But where was Mary Anne Clarke during the period of the trial and through 1813, when, under the terms of her annuity from the Duke of York, she had to leave England for the Continent?

In her questioning at the 1809 trial she stated that she was a widow living in “Loughton Lodge, in the county of Essex.” So, apparently – or, according to her – her husband, Joseph Clarke, the philandering drunkard, is deceased. But was she actually living where she said she was? The truth and Mary Anne Clarke were never friends, so some skepticism is in order.

According to an article by one Richard Morris in the March/April 2008 newsletter of the Loughton Historical Society, there are some doubts as to her residence in the area at all, though Morris, covering his bases, does write at the end of his piece:

“I am, however, convinced that there must be some truth in the story, if only because of Daphne du Maurier’s relationship to Mary Anne Clarke, her reputation as a novelist, the research she did for her book, and the many references in it to Loughton and Loughton Lodge.”

Bless the man, to have such faith in an author’s research! But we know from what Du Maurier said in the preface to her novel Mary Anne that she relied on someone’s “notes” and on the library research of two others. Dicey. So, here’s the dubious part:

“There are in total nine references to Loughton in [the] novel, and one refers to Mary Anne Clarke looking out of the window at Loughton Lodge: ‘at the neat box-garden, the gravel drive, the trim smug Essex landscape’. This can only considered as author’s licence as Loughton Lodge stands on top of Woodbury Hill with its front facing what is now Steeds Way…in 1809 [it] would have given clear views over the Roding Valley and beyond, and the rear which overlooks an attractive part of the Forest.”

The reference in the last line is to Epping Forest, a considerable parcel of wooded area. Hard to overlook.

Morris goes on to say that he can find no specific evidence of Mary Anne Clarke’s time in Loughton, even though a local street – in acknowledgement of her supposed time in the town -- was changed from Mutton Row to York Hill in 1850. When Mary Anne was supposedly in residence at Loughton Lodge, though, it belonged to a family named Shiers. True, she could have been a lodger at the Lodge, but lodging in someone else’s digs was never Mary Anne’s style.

And what of this Loughton Lodge today? Turned into an old folks’ home after World War II, it was subsequently divided into two separate houses. I have not been able to find an image of it, either as it was then, or as it is today. Nor was I able to verify that “a blue plaque” was affixed to the building in April of 2009.

In 1811, wherever Mary Anne was, she did one other thing for posterity, that is, she commissioned the Irish-born sculptor Lawrence Gahagan to sculpt a marble bust of her (now in London’s National Portrait Gallery). It’s very beautiful.

Mary Anne Clarke rises from the open petals of a sunflower. She’s thought to represent Clytie, the abandoned lover of the sun god, Helios, changed into a sunflower so that she could follow her perfidious lover's progress across the sky each day

Mary Anne Clarke rises from the open petals of a sunflower. She’s thought to represent Clytie, the abandoned lover of the sun god, Helios, changed into a sunflower so that she could follow her perfidious lover's progress across the sky each daySo, we come to the question… Do all old English courtesans die impoverished – and disgraced -- in France? Grace Dalrymple Elliott died there, in the village of Meudon, and, if not in poverty, close to it; Dorothy Jordan definitely died in awful poverty in Saint-Cloud; Mary Robinson didn’t die in France – she died at home, in England -- but she died as poor as it was possible to be; likewise Emma Hamilton, who met her sad demise in Calais.

And then there’s Mary Anne Clarke. Yes, she died in France – after extensive travels through Italy and Belgium -- in Boulogne-sur-Mer, but decidedly not in poverty. That generous annuity from the Duke of York saw her through, as it did her daughter Ellen Clarke Busson du Maurier, who raised her family on it.

The irony – there’s always the irony – is that poor Ellen Clarke (said to be as unattractive as her mother was beautiful, with sallow skin and sharp features) apparently was under the illusion for years that she was the by-blow of the Duke of York, but though she was probably not the daughter of her mother’s husband Joseph Clarke, neither could she have been the daughter of Frederick. Her mother – though she certainly knew many men intimately between Clarke and Frederick – did not meet the Duke of York until Ellen was at least six years old. Her biological father is a mystery.

Ellen, so unlike her mother in every way – save perhaps for the sharpness of her tongue -- married the inventor Louis-Mathurin Busson du Maurier, a charming, talented dreamer (said to have a beautiful singing voice) who never amounted to anything and was prone, as were others in his family, to depression. His so-called inventions were laughable and he was forever in debt. Although it appeared to have been a love-match, it was disastrous. Ellen had to borrow from her mother and her sister-in-law Louise all her married life. When she came into the annuity in 1852 – either in whole or in part -- upon the death of Mary Anne Clarke, she still found it difficult to make ends meet, as her children seemed to have a hard time making decent livings.

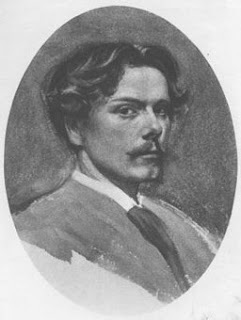

George Du Maurier, author of Trilby

Late in his life, however, her eldest child, and her favorite, George Du Maurier, became a successful cartoonist for Punch and other political publications of the day, and, at age sixty, he wrote a bestselling novel, Trilby, inspired by his experiences as an art student in Paris. His son, Gerald Du Maurier, the well-known actor-manager, was the father of Daphne Du Maurier. (There is a marked resemblance in the image above between George and Daphne. Look at their noses.)

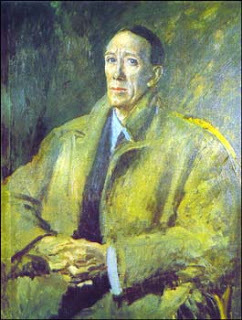

Gerald Du Maurier, respected actor-manager and father of Daphne Du Maurier, by Augustus John

Quite a legacy, this of the Busson du Mauriers and the Clarkes. It was a spirited one, for sure, thanks largely to Mary Anne. Daphne Du Maurier, whose attitude towards her ancestor I find somewhat ambivalent, summed up this legacy in The Du Mauriers:

“The pleasant, sweet-natured, melancholy Bussons of Sarthe had not such fortitude. These fighting qualities were bequeathed…by a woman, a woman without morals, without honour, without virtue, a woman who had known exactly what she wanted at fifteen years of age, and, gutter-born and gutter-bred, treading on sensibility and courtesy with her exquisite feet, had achieved it laughing – her thumb to her nose.”

As for the blog post by Kristine comparing Sarah Ferguson, Duchess of York, to Mary Anne Clarke? Mary Anne could have taught her a thing or two, methinks. Yes, Mary Anne was as greedy as they come, but she was a whole lot smarter and a good deal more conniving. The greed and love of luxury ultimately brought her down – as, indeed, it appears to have brought down this 21st century Duchess – but, while Mary Anne was down, dear readers, she was never really out. The spunky baggage was a survivor, as so many of her courtesan sisters were not. A dreadful woman, but one has to admire her survival skills. I think that, in the end, her great-great-grand-daughter surely did.Her last words to her son and daughter-in-law were said to be, “It is high time we had another party.”

The novelist Daphne Du Maurier as a young woman

The novelist Daphne Du Maurier as a young womanThe End

Originally published on October 28, 2010

Published on August 30, 2016 23:30

August 26, 2016

A TOUR GUIDE IN ENGLAND: RANDOM WELLINGTONS SEEN ALONG THE WAY

Most people think that Victoria, Diane and I go out of way when in England to find all things Wellington, but it's just not so. Oh, sometimes we do, like when I visit my antiques dealer in London or when we go to places like Apsley House and Walmer Castle, but you'd be surprised how many random Wellington's there are to be found in England. Here are just a few examples, most of which were randomly happened upon.

Above, my favourite antique dealer, Mark Sullivan, holding my latest Artie-fact

Above and below, National Portrait Gallery

Above Royal Chelsea Hospital

Above, the Duke of Wellington Pub, Sloane Square

Above and below, the Wellington Pub, Strand

Above Somerset House

Above, Preston Manor, Brighton

Above lobby, Royal Horseguards Hotel

Above, moored on the Thames

Above, Apsley House

Published on August 26, 2016 22:30

Kristine Hughes's Blog

- Kristine Hughes's profile

- 6 followers

Kristine Hughes isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.