Kristine Hughes's Blog, page 101

November 4, 2013

Victoria Visits the Wellington Arch

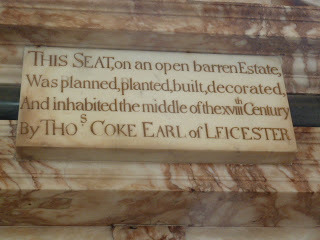

When we returned to London from our three-day trip -- one each in Cambridge, at Houghton Hall, and at Holkham Hall, I had a busy agenda for the remaining few days of our trip. Poor hubby Ed suffered every day from that very sore foot, aching now in addition to blisters, scrapes and -- well, you get the picture. I always gave him the option of staying put at the hotel, but he stoically limped onward.

Despite the fact that I had visited Apsley House several times, with Kristine, with Pat, my sister-in-law, and others, Ed had never been there. So that was second on my list, just behind the Wellington Arch, which I'd never visited. I'd walked past it plenty of times, but it had not been open before. A bit of web checking told me that the Arch recently opened exhibition space, at that time devoted to a study of the many past and current attempt to SAVE British heritage, particularly by protecting buildings and open spaces.

The Wellington Arch website is here.

Soapbox alert!!! It doesn't take much beyond a glance at the London skyline to see how contemporary skyscrapers overpower and almost obliterate the beautiful early 20th century view of St. Paul's Dome and the many graceful steeples and spires. Okay, call me a traditionalist (Guilty!) but I wish the powers-that-be could have kept the tall buildings in groups away from the City, Mayfair and Westminster. Alas, it is far too late.

View from the Wellington Arch (including a few stray smudges) I have nothing against tall buildings -- I live in one. But if they had been clustered in various neighborhoods away from the center of London, the beautiful skyline would have been preserved. True of a few cities, Washington, D C for example. No high rises downtown, all clustered in the surrounding communities to preserve the views of the Capitol and other monuments. End of soapbox. Please resume your usual activities.

View from the Wellington Arch (including a few stray smudges) I have nothing against tall buildings -- I live in one. But if they had been clustered in various neighborhoods away from the center of London, the beautiful skyline would have been preserved. True of a few cities, Washington, D C for example. No high rises downtown, all clustered in the surrounding communities to preserve the views of the Capitol and other monuments. End of soapbox. Please resume your usual activities.

At the height of the Roman Empire, triumphal arches were built to commemorate great events. Think of Rome's Arch of Constantine, the Arch of Titus, and so on. The French started building one in 1806 to mark Napoleon's victory in the Battle of Austerlitz, but it remained unfinished for thirty years, now known as the Arc de Triomphe de l'Etoile in Paris. Not to be outdone, the Prince Regent, later King George IV, wanted to memorialize British victory over France..

At the height of the Roman Empire, triumphal arches were built to commemorate great events. Think of Rome's Arch of Constantine, the Arch of Titus, and so on. The French started building one in 1806 to mark Napoleon's victory in the Battle of Austerlitz, but it remained unfinished for thirty years, now known as the Arc de Triomphe de l'Etoile in Paris. Not to be outdone, the Prince Regent, later King George IV, wanted to memorialize British victory over France..

Wellington Arch; Apsley House at the far right Both the Wellington Arch (aka the Green Park Arch and the Constitution Arch) and the Marble Arch were affected by political arguments over cost, design and placement in the 19th century. Both were moved from their original positions and both stand relatively isolated in the middle of traffic circles surrounded by buses, autos, lorries and other noisy vehicles. Traffic too often trumps landscape. Whoops, soapbox again.

Wellington Arch; Apsley House at the far right Both the Wellington Arch (aka the Green Park Arch and the Constitution Arch) and the Marble Arch were affected by political arguments over cost, design and placement in the 19th century. Both were moved from their original positions and both stand relatively isolated in the middle of traffic circles surrounded by buses, autos, lorries and other noisy vehicles. Traffic too often trumps landscape. Whoops, soapbox again.

One of the gates, cast in iron by Joseph Bramah and Sons, restored recently The Wellington Arch was designed by Architect Decimus Burton (1800-1881), as his name indicates, the tenth child in his family. He worked with his father, also an architect and John Nash as well. He also designed the Hyde Park screen next to Apsley House.

One of the gates, cast in iron by Joseph Bramah and Sons, restored recently The Wellington Arch was designed by Architect Decimus Burton (1800-1881), as his name indicates, the tenth child in his family. He worked with his father, also an architect and John Nash as well. He also designed the Hyde Park screen next to Apsley House.

The Hyde Park Screen, 1825

The Hyde Park Screen, 1825

This picture shows the screen in relation to Apsley House; the Wellington is Arch off the picture to the right A few years ago, English Heritage took over the Wellington Arch and changed it from a small police into to a small gift shop with an exhibition space above. There is access to the viewing balcony at the top as well, all by elevator. Ed's sore foot appreciated that particularly!

This picture shows the screen in relation to Apsley House; the Wellington is Arch off the picture to the right A few years ago, English Heritage took over the Wellington Arch and changed it from a small police into to a small gift shop with an exhibition space above. There is access to the viewing balcony at the top as well, all by elevator. Ed's sore foot appreciated that particularly!

View down Constitution Hill towards Buckingham Palace

View down Constitution Hill towards Buckingham Palace

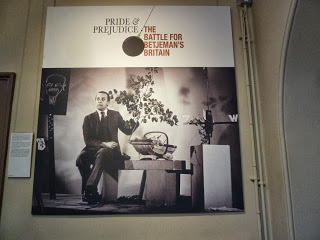

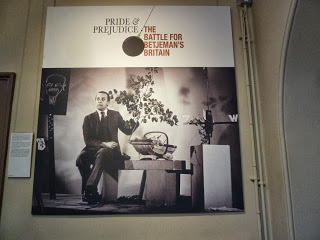

The Exhibition: Pride and Prejudice: The Battle for Betjeman's Britain John Betjeman (1906-1984) was Britain's Poet Laureate in addition to being a popular radio and tv commentator and an avid campaigner for the protection of architectural heritage. Below, the maquette for his statue located in St. Pancras Station, one of the buildings he successfully fought to save.

The Exhibition: Pride and Prejudice: The Battle for Betjeman's Britain John Betjeman (1906-1984) was Britain's Poet Laureate in addition to being a popular radio and tv commentator and an avid campaigner for the protection of architectural heritage. Below, the maquette for his statue located in St. Pancras Station, one of the buildings he successfully fought to save.

John Betjeman (maquette) by sculptor Martin Jennings, 2006

John Betjeman (maquette) by sculptor Martin Jennings, 2006

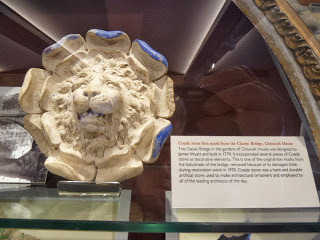

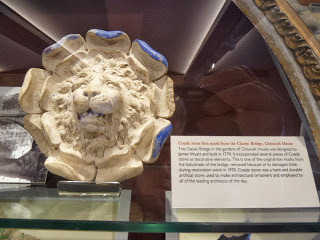

Coade Stone Lion Mask The rosette above came from the Classic Bridge at Chiswick, designed by James Wyatt in 1774; Coade Stone is artificial, often used by leading architects for statues and ornaments.

Coade Stone Lion Mask The rosette above came from the Classic Bridge at Chiswick, designed by James Wyatt in 1774; Coade Stone is artificial, often used by leading architects for statues and ornaments.

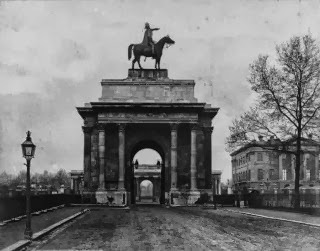

Devonshire House, before and during demolition For more information on this exhibition, click here A group hoping to honor the Duke of Wellington erected a gigantic equestrian statue on top of the arch in 1846. Being out of all proportion to the arch, the statue caused great criticism and even laughter.

Devonshire House, before and during demolition For more information on this exhibition, click here A group hoping to honor the Duke of Wellington erected a gigantic equestrian statue on top of the arch in 1846. Being out of all proportion to the arch, the statue caused great criticism and even laughter.

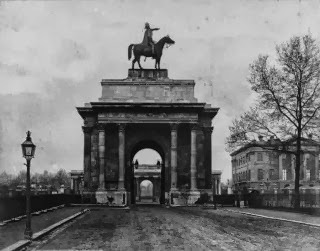

view, about 1860 In 1882-83, The arch was dismantled and rebuilt in its present traffic-bound position. The Statue was moved to Aldershot (after much discussion) where it can be seen today. A few years later, in 1899, Adrian Jones (1845-1938) designed the Quadriga, four horses driven by a boy and crowned by the Angel of Peace. It was completed in 1912.

view, about 1860 In 1882-83, The arch was dismantled and rebuilt in its present traffic-bound position. The Statue was moved to Aldershot (after much discussion) where it can be seen today. A few years later, in 1899, Adrian Jones (1845-1938) designed the Quadriga, four horses driven by a boy and crowned by the Angel of Peace. It was completed in 1912.

From the front and from the back

From the front and from the back

Wellington on Copenhagen holding his telescope Erected in 1888, the statue on the Arch grounds, across the road from Apsley House, was sculpted and cast in bronze by Sir Joseph Edgar Boehm (1834-1890). Boehm was a favorite artist of the royal family and a teacher of sculptress Princess Louise, Duchess of Argyll (1848-1939), Queen Victoria's fourth daughter.

Wellington on Copenhagen holding his telescope Erected in 1888, the statue on the Arch grounds, across the road from Apsley House, was sculpted and cast in bronze by Sir Joseph Edgar Boehm (1834-1890). Boehm was a favorite artist of the royal family and a teacher of sculptress Princess Louise, Duchess of Argyll (1848-1939), Queen Victoria's fourth daughter.

The figures at the four corners of the red granite plinth are guardsmen from Wellington's troops: a Grenadier, a Welsh Fusilier, a Royal Highlander, and an Inniskilling Dragoon.

The figures at the four corners of the red granite plinth are guardsmen from Wellington's troops: a Grenadier, a Welsh Fusilier, a Royal Highlander, and an Inniskilling Dragoon.

As I mentioned before, the Wellington Arch and the equestrian statue stand in the middle of a traffic circle, joined to the adjacent streets and the Hyde Park Corner Tube stop by underground walkways. The white tile walls are decorated with scenes of Wellington and his troops. Below, a few examples as we walked -- or I walked and Ed limped -- to visit Apsley House.

As I mentioned before, the Wellington Arch and the equestrian statue stand in the middle of a traffic circle, joined to the adjacent streets and the Hyde Park Corner Tube stop by underground walkways. The white tile walls are decorated with scenes of Wellington and his troops. Below, a few examples as we walked -- or I walked and Ed limped -- to visit Apsley House.

Next, Victoria and Ed visit Apsley House

Despite the fact that I had visited Apsley House several times, with Kristine, with Pat, my sister-in-law, and others, Ed had never been there. So that was second on my list, just behind the Wellington Arch, which I'd never visited. I'd walked past it plenty of times, but it had not been open before. A bit of web checking told me that the Arch recently opened exhibition space, at that time devoted to a study of the many past and current attempt to SAVE British heritage, particularly by protecting buildings and open spaces.

The Wellington Arch website is here.

Soapbox alert!!! It doesn't take much beyond a glance at the London skyline to see how contemporary skyscrapers overpower and almost obliterate the beautiful early 20th century view of St. Paul's Dome and the many graceful steeples and spires. Okay, call me a traditionalist (Guilty!) but I wish the powers-that-be could have kept the tall buildings in groups away from the City, Mayfair and Westminster. Alas, it is far too late.

View from the Wellington Arch (including a few stray smudges) I have nothing against tall buildings -- I live in one. But if they had been clustered in various neighborhoods away from the center of London, the beautiful skyline would have been preserved. True of a few cities, Washington, D C for example. No high rises downtown, all clustered in the surrounding communities to preserve the views of the Capitol and other monuments. End of soapbox. Please resume your usual activities.

View from the Wellington Arch (including a few stray smudges) I have nothing against tall buildings -- I live in one. But if they had been clustered in various neighborhoods away from the center of London, the beautiful skyline would have been preserved. True of a few cities, Washington, D C for example. No high rises downtown, all clustered in the surrounding communities to preserve the views of the Capitol and other monuments. End of soapbox. Please resume your usual activities.

At the height of the Roman Empire, triumphal arches were built to commemorate great events. Think of Rome's Arch of Constantine, the Arch of Titus, and so on. The French started building one in 1806 to mark Napoleon's victory in the Battle of Austerlitz, but it remained unfinished for thirty years, now known as the Arc de Triomphe de l'Etoile in Paris. Not to be outdone, the Prince Regent, later King George IV, wanted to memorialize British victory over France..

At the height of the Roman Empire, triumphal arches were built to commemorate great events. Think of Rome's Arch of Constantine, the Arch of Titus, and so on. The French started building one in 1806 to mark Napoleon's victory in the Battle of Austerlitz, but it remained unfinished for thirty years, now known as the Arc de Triomphe de l'Etoile in Paris. Not to be outdone, the Prince Regent, later King George IV, wanted to memorialize British victory over France..

Wellington Arch; Apsley House at the far right Both the Wellington Arch (aka the Green Park Arch and the Constitution Arch) and the Marble Arch were affected by political arguments over cost, design and placement in the 19th century. Both were moved from their original positions and both stand relatively isolated in the middle of traffic circles surrounded by buses, autos, lorries and other noisy vehicles. Traffic too often trumps landscape. Whoops, soapbox again.

Wellington Arch; Apsley House at the far right Both the Wellington Arch (aka the Green Park Arch and the Constitution Arch) and the Marble Arch were affected by political arguments over cost, design and placement in the 19th century. Both were moved from their original positions and both stand relatively isolated in the middle of traffic circles surrounded by buses, autos, lorries and other noisy vehicles. Traffic too often trumps landscape. Whoops, soapbox again.

One of the gates, cast in iron by Joseph Bramah and Sons, restored recently The Wellington Arch was designed by Architect Decimus Burton (1800-1881), as his name indicates, the tenth child in his family. He worked with his father, also an architect and John Nash as well. He also designed the Hyde Park screen next to Apsley House.

One of the gates, cast in iron by Joseph Bramah and Sons, restored recently The Wellington Arch was designed by Architect Decimus Burton (1800-1881), as his name indicates, the tenth child in his family. He worked with his father, also an architect and John Nash as well. He also designed the Hyde Park screen next to Apsley House.

The Hyde Park Screen, 1825

The Hyde Park Screen, 1825

This picture shows the screen in relation to Apsley House; the Wellington is Arch off the picture to the right A few years ago, English Heritage took over the Wellington Arch and changed it from a small police into to a small gift shop with an exhibition space above. There is access to the viewing balcony at the top as well, all by elevator. Ed's sore foot appreciated that particularly!

This picture shows the screen in relation to Apsley House; the Wellington is Arch off the picture to the right A few years ago, English Heritage took over the Wellington Arch and changed it from a small police into to a small gift shop with an exhibition space above. There is access to the viewing balcony at the top as well, all by elevator. Ed's sore foot appreciated that particularly!

View down Constitution Hill towards Buckingham Palace

View down Constitution Hill towards Buckingham Palace

The Exhibition: Pride and Prejudice: The Battle for Betjeman's Britain John Betjeman (1906-1984) was Britain's Poet Laureate in addition to being a popular radio and tv commentator and an avid campaigner for the protection of architectural heritage. Below, the maquette for his statue located in St. Pancras Station, one of the buildings he successfully fought to save.

The Exhibition: Pride and Prejudice: The Battle for Betjeman's Britain John Betjeman (1906-1984) was Britain's Poet Laureate in addition to being a popular radio and tv commentator and an avid campaigner for the protection of architectural heritage. Below, the maquette for his statue located in St. Pancras Station, one of the buildings he successfully fought to save.

John Betjeman (maquette) by sculptor Martin Jennings, 2006

John Betjeman (maquette) by sculptor Martin Jennings, 2006

Coade Stone Lion Mask The rosette above came from the Classic Bridge at Chiswick, designed by James Wyatt in 1774; Coade Stone is artificial, often used by leading architects for statues and ornaments.

Coade Stone Lion Mask The rosette above came from the Classic Bridge at Chiswick, designed by James Wyatt in 1774; Coade Stone is artificial, often used by leading architects for statues and ornaments.

Devonshire House, before and during demolition For more information on this exhibition, click here A group hoping to honor the Duke of Wellington erected a gigantic equestrian statue on top of the arch in 1846. Being out of all proportion to the arch, the statue caused great criticism and even laughter.

Devonshire House, before and during demolition For more information on this exhibition, click here A group hoping to honor the Duke of Wellington erected a gigantic equestrian statue on top of the arch in 1846. Being out of all proportion to the arch, the statue caused great criticism and even laughter.

view, about 1860 In 1882-83, The arch was dismantled and rebuilt in its present traffic-bound position. The Statue was moved to Aldershot (after much discussion) where it can be seen today. A few years later, in 1899, Adrian Jones (1845-1938) designed the Quadriga, four horses driven by a boy and crowned by the Angel of Peace. It was completed in 1912.

view, about 1860 In 1882-83, The arch was dismantled and rebuilt in its present traffic-bound position. The Statue was moved to Aldershot (after much discussion) where it can be seen today. A few years later, in 1899, Adrian Jones (1845-1938) designed the Quadriga, four horses driven by a boy and crowned by the Angel of Peace. It was completed in 1912.

From the front and from the back

From the front and from the back

Wellington on Copenhagen holding his telescope Erected in 1888, the statue on the Arch grounds, across the road from Apsley House, was sculpted and cast in bronze by Sir Joseph Edgar Boehm (1834-1890). Boehm was a favorite artist of the royal family and a teacher of sculptress Princess Louise, Duchess of Argyll (1848-1939), Queen Victoria's fourth daughter.

Wellington on Copenhagen holding his telescope Erected in 1888, the statue on the Arch grounds, across the road from Apsley House, was sculpted and cast in bronze by Sir Joseph Edgar Boehm (1834-1890). Boehm was a favorite artist of the royal family and a teacher of sculptress Princess Louise, Duchess of Argyll (1848-1939), Queen Victoria's fourth daughter. The figures at the four corners of the red granite plinth are guardsmen from Wellington's troops: a Grenadier, a Welsh Fusilier, a Royal Highlander, and an Inniskilling Dragoon.

The figures at the four corners of the red granite plinth are guardsmen from Wellington's troops: a Grenadier, a Welsh Fusilier, a Royal Highlander, and an Inniskilling Dragoon.

As I mentioned before, the Wellington Arch and the equestrian statue stand in the middle of a traffic circle, joined to the adjacent streets and the Hyde Park Corner Tube stop by underground walkways. The white tile walls are decorated with scenes of Wellington and his troops. Below, a few examples as we walked -- or I walked and Ed limped -- to visit Apsley House.

As I mentioned before, the Wellington Arch and the equestrian statue stand in the middle of a traffic circle, joined to the adjacent streets and the Hyde Park Corner Tube stop by underground walkways. The white tile walls are decorated with scenes of Wellington and his troops. Below, a few examples as we walked -- or I walked and Ed limped -- to visit Apsley House.

Next, Victoria and Ed visit Apsley House

Published on November 04, 2013 00:30

November 1, 2013

The Magnificent Waterloo Chamber: The Wellington Tour

Victoria here, inviting you to join Kristine and me on The Wellington Tour, 4-14 September, 2014. For details on our planned itinerary, costs and other info, click here. Among the features of the tour is a visit to Windsor Castle and especially to its Waterloo Chamber.

Windsor Castle from the Thames The Waterloo Chamber was constructed within the Castle to commemorate the victory of the Allied Armies over the French in the Battle of Waterloo, June 18, 1815. Architect Sir Jeffry Wyattville (1766 – 1840) created the Chamber in 1824 out of several existing rooms. Parliament designated £300,000 for the project. Like most of King George IV's inspirations, it ran well over budget, eventually costing about £1,000,000. Wyattville also remodeled many other areas of Windsor Castle for George IV, William IV, and Queen Victoria; he was buried in the Castle's St. George's Chapel in 1840.

Windsor Castle from the Thames The Waterloo Chamber was constructed within the Castle to commemorate the victory of the Allied Armies over the French in the Battle of Waterloo, June 18, 1815. Architect Sir Jeffry Wyattville (1766 – 1840) created the Chamber in 1824 out of several existing rooms. Parliament designated £300,000 for the project. Like most of King George IV's inspirations, it ran well over budget, eventually costing about £1,000,000. Wyattville also remodeled many other areas of Windsor Castle for George IV, William IV, and Queen Victoria; he was buried in the Castle's St. George's Chapel in 1840.

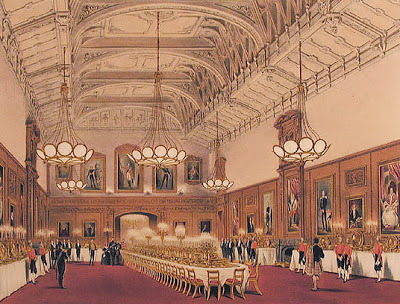

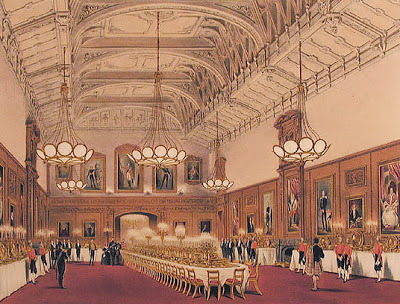

Watercolour of the Waterloo Chamber in 1844 by Joseph Nash

Watercolour of the Waterloo Chamber in 1844 by Joseph Nash

Waterloo Chamber, currently For a virtual tour of the entire Waterloo Chamber, click here.

Waterloo Chamber, currently For a virtual tour of the entire Waterloo Chamber, click here.

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of WellingtonCommander of the Victorious Allied Armies The walls of the Waterloo Chamber are filled with large portraits of the leaders of the Allied efforts. Most of them are painted by Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769-1830), the Regency era's favorite artist. Many were reproduced several times by his studio for numerous placements in other palaces, stately homes and distinguished galleries.

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of WellingtonCommander of the Victorious Allied Armies The walls of the Waterloo Chamber are filled with large portraits of the leaders of the Allied efforts. Most of them are painted by Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769-1830), the Regency era's favorite artist. Many were reproduced several times by his studio for numerous placements in other palaces, stately homes and distinguished galleries.

Prussian General Gebhardt von BlücherWellington's Comrade-in-arms at WaterlooSir Thomas Lawrence 1816 The Prince Regent (later George IV) commissioned Lawrence to paint all the Allied Sovereigns, military leaders, and statesmen. Lawrence traveled around Europe to complete the portraits.

Prussian General Gebhardt von BlücherWellington's Comrade-in-arms at WaterlooSir Thomas Lawrence 1816 The Prince Regent (later George IV) commissioned Lawrence to paint all the Allied Sovereigns, military leaders, and statesmen. Lawrence traveled around Europe to complete the portraits.

Austrian Field Marshal Karl Philipp, Prince of Schwartzenberg,

Austrian Field Marshal Karl Philipp, Prince of Schwartzenberg,

Alexander I, Emperor of Russia (1777-1825)painted by Sir Thomas Lawrence, 1818 According to the Royal Collection Website, "While working on the portrait Lawrence altered the position of the legs, much to the consternation of the Tzar and those courtiers attending the portrait sitting, especially when for a while the sitter was shown with four legs." Obviously, this condition was corrected!

Alexander I, Emperor of Russia (1777-1825)painted by Sir Thomas Lawrence, 1818 According to the Royal Collection Website, "While working on the portrait Lawrence altered the position of the legs, much to the consternation of the Tzar and those courtiers attending the portrait sitting, especially when for a while the sitter was shown with four legs." Obviously, this condition was corrected!

Pope Pius VII, 1819-20 The portrait of Pope Pius VII (1742-1823), painted in Rome, is widely agreed to be Lawrence's masterpiece, both incisive and sympathetic. While heads of state and leading generals were depicted full length, politicians and statesmen were honored with 3/4 length portraits, perhaps putting them in their place?

Pope Pius VII, 1819-20 The portrait of Pope Pius VII (1742-1823), painted in Rome, is widely agreed to be Lawrence's masterpiece, both incisive and sympathetic. While heads of state and leading generals were depicted full length, politicians and statesmen were honored with 3/4 length portraits, perhaps putting them in their place?

Viscount CastlereaghSir Thomas Lawrence, 1830 Robert Stewart (1769-1822), Viscount Castlereagh, later second Marquess of Londonderry, served as Secretary of State for War 1805-09, and Foreign Secretary 1812-1822

Viscount CastlereaghSir Thomas Lawrence, 1830 Robert Stewart (1769-1822), Viscount Castlereagh, later second Marquess of Londonderry, served as Secretary of State for War 1805-09, and Foreign Secretary 1812-1822

Robert Banks Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool Robert Banks Jenkinson (1770-1828), 2nd Earl of Liverpool was Prime Minister from 1812 to 1827, and also preceded the Duke of Wellington as the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports, about which more soon!! In the words of the Windsor Castle guidebook, "Most of the twenty eight portraits were delivered after his [Lawrence's] death on 7 January 1830. By this time work was already begun of the space of the Waterloo Chamber created by covering a courtyard at Windsor Castle with a huge sky-lit vault; the room was completed during the reign of William IV (1830-7)...the arrangement which survives to this day: full-length portraits of warriors hang high, over the two end balconies and around the walls; at ground level full-length portraits of monarchs alternate with half-lengths of diplomats and statesmen."

Robert Banks Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool Robert Banks Jenkinson (1770-1828), 2nd Earl of Liverpool was Prime Minister from 1812 to 1827, and also preceded the Duke of Wellington as the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports, about which more soon!! In the words of the Windsor Castle guidebook, "Most of the twenty eight portraits were delivered after his [Lawrence's] death on 7 January 1830. By this time work was already begun of the space of the Waterloo Chamber created by covering a courtyard at Windsor Castle with a huge sky-lit vault; the room was completed during the reign of William IV (1830-7)...the arrangement which survives to this day: full-length portraits of warriors hang high, over the two end balconies and around the walls; at ground level full-length portraits of monarchs alternate with half-lengths of diplomats and statesmen."

The limewood carvings on the walls were removed from the former Royal Chapel before it was demolished in the 1820s. The carvings date from the 1680's, the work of renowned artist Grinling Gibbons. According to the Castle Guidebook, "The Indian carpet was woven for this room by the inmates of Agra prison for Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee, finally reaching Windsor in 1894. Thought to be the largest seamless carpet in existence, it weighs two tonnes. During the 1992 fire it took 50 soldiers to roll it up and move it to safety." Which brings up a sorrowful subject, the terrible fire of eleven years ago.

The limewood carvings on the walls were removed from the former Royal Chapel before it was demolished in the 1820s. The carvings date from the 1680's, the work of renowned artist Grinling Gibbons. According to the Castle Guidebook, "The Indian carpet was woven for this room by the inmates of Agra prison for Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee, finally reaching Windsor in 1894. Thought to be the largest seamless carpet in existence, it weighs two tonnes. During the 1992 fire it took 50 soldiers to roll it up and move it to safety." Which brings up a sorrowful subject, the terrible fire of eleven years ago.

20 November, 1992 Extensive damage resulted from the fire though the Waterloo Chamber was only slightly damaged, due to the thickness of the walls. Other areas were destroyed and eventually repaired. To pay for the £36.5 million repairs, the Queen opened the State Rooms of Buckingham Palace to the Public, but only when she is in residence elsewhere. When you tour Windsor Castle with Kristine and me, you will see the renovated areas and where the fire burned. And we will view the Waterloo Chamber -- and all the State rooms, most of them still very much as they were when redone for George IV by Sir Jeffry Wyattville. Again to access more information on the Wellington Tour, go to http://wellingtontour.blogspot.com/

20 November, 1992 Extensive damage resulted from the fire though the Waterloo Chamber was only slightly damaged, due to the thickness of the walls. Other areas were destroyed and eventually repaired. To pay for the £36.5 million repairs, the Queen opened the State Rooms of Buckingham Palace to the Public, but only when she is in residence elsewhere. When you tour Windsor Castle with Kristine and me, you will see the renovated areas and where the fire burned. And we will view the Waterloo Chamber -- and all the State rooms, most of them still very much as they were when redone for George IV by Sir Jeffry Wyattville. Again to access more information on the Wellington Tour, go to http://wellingtontour.blogspot.com/

.

.

Windsor Castle from the Thames The Waterloo Chamber was constructed within the Castle to commemorate the victory of the Allied Armies over the French in the Battle of Waterloo, June 18, 1815. Architect Sir Jeffry Wyattville (1766 – 1840) created the Chamber in 1824 out of several existing rooms. Parliament designated £300,000 for the project. Like most of King George IV's inspirations, it ran well over budget, eventually costing about £1,000,000. Wyattville also remodeled many other areas of Windsor Castle for George IV, William IV, and Queen Victoria; he was buried in the Castle's St. George's Chapel in 1840.

Windsor Castle from the Thames The Waterloo Chamber was constructed within the Castle to commemorate the victory of the Allied Armies over the French in the Battle of Waterloo, June 18, 1815. Architect Sir Jeffry Wyattville (1766 – 1840) created the Chamber in 1824 out of several existing rooms. Parliament designated £300,000 for the project. Like most of King George IV's inspirations, it ran well over budget, eventually costing about £1,000,000. Wyattville also remodeled many other areas of Windsor Castle for George IV, William IV, and Queen Victoria; he was buried in the Castle's St. George's Chapel in 1840.

Watercolour of the Waterloo Chamber in 1844 by Joseph Nash

Watercolour of the Waterloo Chamber in 1844 by Joseph Nash

Waterloo Chamber, currently For a virtual tour of the entire Waterloo Chamber, click here.

Waterloo Chamber, currently For a virtual tour of the entire Waterloo Chamber, click here.

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of WellingtonCommander of the Victorious Allied Armies The walls of the Waterloo Chamber are filled with large portraits of the leaders of the Allied efforts. Most of them are painted by Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769-1830), the Regency era's favorite artist. Many were reproduced several times by his studio for numerous placements in other palaces, stately homes and distinguished galleries.

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of WellingtonCommander of the Victorious Allied Armies The walls of the Waterloo Chamber are filled with large portraits of the leaders of the Allied efforts. Most of them are painted by Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769-1830), the Regency era's favorite artist. Many were reproduced several times by his studio for numerous placements in other palaces, stately homes and distinguished galleries.

Prussian General Gebhardt von BlücherWellington's Comrade-in-arms at WaterlooSir Thomas Lawrence 1816 The Prince Regent (later George IV) commissioned Lawrence to paint all the Allied Sovereigns, military leaders, and statesmen. Lawrence traveled around Europe to complete the portraits.

Prussian General Gebhardt von BlücherWellington's Comrade-in-arms at WaterlooSir Thomas Lawrence 1816 The Prince Regent (later George IV) commissioned Lawrence to paint all the Allied Sovereigns, military leaders, and statesmen. Lawrence traveled around Europe to complete the portraits.

Austrian Field Marshal Karl Philipp, Prince of Schwartzenberg,

Austrian Field Marshal Karl Philipp, Prince of Schwartzenberg,

Alexander I, Emperor of Russia (1777-1825)painted by Sir Thomas Lawrence, 1818 According to the Royal Collection Website, "While working on the portrait Lawrence altered the position of the legs, much to the consternation of the Tzar and those courtiers attending the portrait sitting, especially when for a while the sitter was shown with four legs." Obviously, this condition was corrected!

Alexander I, Emperor of Russia (1777-1825)painted by Sir Thomas Lawrence, 1818 According to the Royal Collection Website, "While working on the portrait Lawrence altered the position of the legs, much to the consternation of the Tzar and those courtiers attending the portrait sitting, especially when for a while the sitter was shown with four legs." Obviously, this condition was corrected!

Pope Pius VII, 1819-20 The portrait of Pope Pius VII (1742-1823), painted in Rome, is widely agreed to be Lawrence's masterpiece, both incisive and sympathetic. While heads of state and leading generals were depicted full length, politicians and statesmen were honored with 3/4 length portraits, perhaps putting them in their place?

Pope Pius VII, 1819-20 The portrait of Pope Pius VII (1742-1823), painted in Rome, is widely agreed to be Lawrence's masterpiece, both incisive and sympathetic. While heads of state and leading generals were depicted full length, politicians and statesmen were honored with 3/4 length portraits, perhaps putting them in their place?

Viscount CastlereaghSir Thomas Lawrence, 1830 Robert Stewart (1769-1822), Viscount Castlereagh, later second Marquess of Londonderry, served as Secretary of State for War 1805-09, and Foreign Secretary 1812-1822

Viscount CastlereaghSir Thomas Lawrence, 1830 Robert Stewart (1769-1822), Viscount Castlereagh, later second Marquess of Londonderry, served as Secretary of State for War 1805-09, and Foreign Secretary 1812-1822

Robert Banks Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool Robert Banks Jenkinson (1770-1828), 2nd Earl of Liverpool was Prime Minister from 1812 to 1827, and also preceded the Duke of Wellington as the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports, about which more soon!! In the words of the Windsor Castle guidebook, "Most of the twenty eight portraits were delivered after his [Lawrence's] death on 7 January 1830. By this time work was already begun of the space of the Waterloo Chamber created by covering a courtyard at Windsor Castle with a huge sky-lit vault; the room was completed during the reign of William IV (1830-7)...the arrangement which survives to this day: full-length portraits of warriors hang high, over the two end balconies and around the walls; at ground level full-length portraits of monarchs alternate with half-lengths of diplomats and statesmen."

Robert Banks Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool Robert Banks Jenkinson (1770-1828), 2nd Earl of Liverpool was Prime Minister from 1812 to 1827, and also preceded the Duke of Wellington as the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports, about which more soon!! In the words of the Windsor Castle guidebook, "Most of the twenty eight portraits were delivered after his [Lawrence's] death on 7 January 1830. By this time work was already begun of the space of the Waterloo Chamber created by covering a courtyard at Windsor Castle with a huge sky-lit vault; the room was completed during the reign of William IV (1830-7)...the arrangement which survives to this day: full-length portraits of warriors hang high, over the two end balconies and around the walls; at ground level full-length portraits of monarchs alternate with half-lengths of diplomats and statesmen."

The limewood carvings on the walls were removed from the former Royal Chapel before it was demolished in the 1820s. The carvings date from the 1680's, the work of renowned artist Grinling Gibbons. According to the Castle Guidebook, "The Indian carpet was woven for this room by the inmates of Agra prison for Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee, finally reaching Windsor in 1894. Thought to be the largest seamless carpet in existence, it weighs two tonnes. During the 1992 fire it took 50 soldiers to roll it up and move it to safety." Which brings up a sorrowful subject, the terrible fire of eleven years ago.

The limewood carvings on the walls were removed from the former Royal Chapel before it was demolished in the 1820s. The carvings date from the 1680's, the work of renowned artist Grinling Gibbons. According to the Castle Guidebook, "The Indian carpet was woven for this room by the inmates of Agra prison for Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee, finally reaching Windsor in 1894. Thought to be the largest seamless carpet in existence, it weighs two tonnes. During the 1992 fire it took 50 soldiers to roll it up and move it to safety." Which brings up a sorrowful subject, the terrible fire of eleven years ago.

20 November, 1992 Extensive damage resulted from the fire though the Waterloo Chamber was only slightly damaged, due to the thickness of the walls. Other areas were destroyed and eventually repaired. To pay for the £36.5 million repairs, the Queen opened the State Rooms of Buckingham Palace to the Public, but only when she is in residence elsewhere. When you tour Windsor Castle with Kristine and me, you will see the renovated areas and where the fire burned. And we will view the Waterloo Chamber -- and all the State rooms, most of them still very much as they were when redone for George IV by Sir Jeffry Wyattville. Again to access more information on the Wellington Tour, go to http://wellingtontour.blogspot.com/

20 November, 1992 Extensive damage resulted from the fire though the Waterloo Chamber was only slightly damaged, due to the thickness of the walls. Other areas were destroyed and eventually repaired. To pay for the £36.5 million repairs, the Queen opened the State Rooms of Buckingham Palace to the Public, but only when she is in residence elsewhere. When you tour Windsor Castle with Kristine and me, you will see the renovated areas and where the fire burned. And we will view the Waterloo Chamber -- and all the State rooms, most of them still very much as they were when redone for George IV by Sir Jeffry Wyattville. Again to access more information on the Wellington Tour, go to http://wellingtontour.blogspot.com/

.

.

Published on November 01, 2013 00:30

October 30, 2013

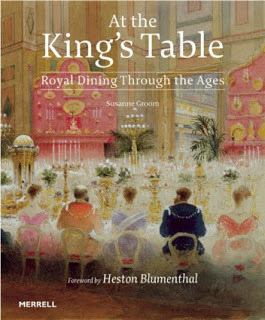

At the King's Table by Susanne Groom

Victoria here, reporting on a meeting I attended recently at Chicago's Newberry Library. Cosponsored by the Royal Oak Foundation, the U.S. support group for Britain's National Trust, and Historic Royal Palaces Inc., I met my pal Susan Forgue to hear Suzanne Groom speak about her new book, At the King's Table.

In addition to many other activities, the Royal Oak Foundation brings speakers to various cities around the U.S. for fascinating illustrated lectures. To learn more about the Royal Oak Foundation, click here. Historic Royal Palaces website is here. And, to complete the picture, click here for the Newberry Library website.

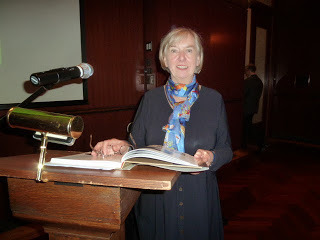

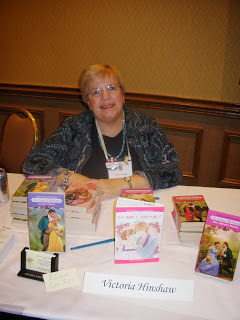

In addition to many other activities, the Royal Oak Foundation brings speakers to various cities around the U.S. for fascinating illustrated lectures. To learn more about the Royal Oak Foundation, click here. Historic Royal Palaces website is here. And, to complete the picture, click here for the Newberry Library website. Suzanne Groom, author of At the King's Table

Suzanne Groom, author of At the King's Table The Newberry Library in October Ms. Groom spent 25 years with Historic Royal Palaces, working at projects at Hampton Court, the Banqueting House and Kew Palace. Her account, beautifully illustrated, of the feasts held by the Kings of England, goes back to William the Conqueror. I cannot begin to reproduce all her fascinating stories of Royal Banquets, but I can recount a few. You will find much, much more in the book.

The Newberry Library in October Ms. Groom spent 25 years with Historic Royal Palaces, working at projects at Hampton Court, the Banqueting House and Kew Palace. Her account, beautifully illustrated, of the feasts held by the Kings of England, goes back to William the Conqueror. I cannot begin to reproduce all her fascinating stories of Royal Banquets, but I can recount a few. You will find much, much more in the book.

The Field of Cloth of Gold, 1774 Print by James Basire from a 16th-century painting in the Royal Collection. In June of 1520, two young kings, accompanied by their queens, large retinues of knights and retainers and hundreds of servants, met for a conference, jousting and games, music and dancing, and an unprecedented effort to out-impress one another with their sumptuous banquets and extravagant arrangements. Henry VIII and François I of France met at the Field of Cloth of Gold in France, for weeks of celebration of the recent treaty of friendship between the two traditional enemy nations. Despite the fine cuisine and the jolly time for all of those above the scullery help, the friendship was enmity again within a few years. The name of the event grew out of the lavish use for tents, furnishing, and attire of cloth woven with gold thread.

The Field of Cloth of Gold, 1774 Print by James Basire from a 16th-century painting in the Royal Collection. In June of 1520, two young kings, accompanied by their queens, large retinues of knights and retainers and hundreds of servants, met for a conference, jousting and games, music and dancing, and an unprecedented effort to out-impress one another with their sumptuous banquets and extravagant arrangements. Henry VIII and François I of France met at the Field of Cloth of Gold in France, for weeks of celebration of the recent treaty of friendship between the two traditional enemy nations. Despite the fine cuisine and the jolly time for all of those above the scullery help, the friendship was enmity again within a few years. The name of the event grew out of the lavish use for tents, furnishing, and attire of cloth woven with gold thread.

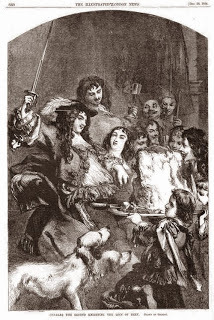

Charles II knighting the beef: Sir Loin An old tale that is difficult to verify tells of a monarch -- in various versions Henry VIII, Elizabeth I, James I, or Charles II -- who drew a sword and knighted a delicious cut of beef. "Arise, Sir Loin," the monarch supposedly said, and thus the finest cuts of beef are so named. True or not, it is an amusing story.

Charles II knighting the beef: Sir Loin An old tale that is difficult to verify tells of a monarch -- in various versions Henry VIII, Elizabeth I, James I, or Charles II -- who drew a sword and knighted a delicious cut of beef. "Arise, Sir Loin," the monarch supposedly said, and thus the finest cuts of beef are so named. True or not, it is an amusing story. Coronation Banquet for James II

Coronation Banquet for James IIA story that is substantiated in many accounts is the coronation banquet of James II (1633-1701), held in Westminster Hall, April 23, 1685. It began at 11:30 am with the arrival of the King and Queen, but other participants had to be in place much earlier. Royalty departed at 7 pm, after the diners had been served 1,145 dishes, including many cuts of meat, sweetmeats, jellies and blancmange. James II did not last long as king; he was replaced in the Glorious Revolution of 1688 by William III of Orange and his Queen, James's daughter Mary.

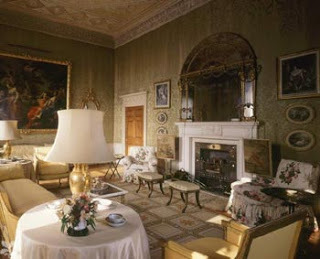

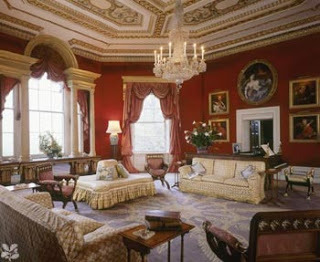

King's Eating Room, Hampton Court Palace William and Mary added on to Hampton Court Palace, and the King's Eating Room is now available for you to hire for your own soiree, if you so desire. As the website says, "It seems an odd idea to us now, but if you visited court in the 18th century one of the highlights would be watching the king eating his dinner. Anyone respectable enough and well-dressed enough (ie, wearing their coat, wig, sword….) would be admitted to see the sight, which took place several times a month. During public dining, King William III or King George II would not sit down to eat with their friends, but would be served in solitary splendour at a table in this room, with the crowds of spectators respectfully standing back. For more information, click here.

King's Eating Room, Hampton Court Palace William and Mary added on to Hampton Court Palace, and the King's Eating Room is now available for you to hire for your own soiree, if you so desire. As the website says, "It seems an odd idea to us now, but if you visited court in the 18th century one of the highlights would be watching the king eating his dinner. Anyone respectable enough and well-dressed enough (ie, wearing their coat, wig, sword….) would be admitted to see the sight, which took place several times a month. During public dining, King William III or King George II would not sit down to eat with their friends, but would be served in solitary splendour at a table in this room, with the crowds of spectators respectfully standing back. For more information, click here.

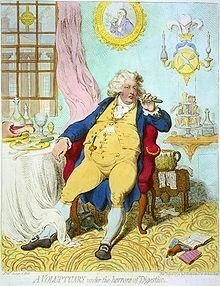

Coronation Banquet of George IV, 1821 Westminster Hall was also the scene of George IV's coronation banquet, the last one held there, although many of us certainly remember the Diamond Jubilee luncheon served there in 2012. As his reputation as a Voluptuary (see Gillray, below) might predict, George IV presided over an expensive and (melo)dramatic pageant for his coronation, which is probably best remembered for locking the door against his estranged wife, who was prepared to be crowned as queen. One of the accounts of the banquet enumerated some of the dishes served, "soups including turtle, salmon, turbot, and trout, venison and veal, mutton and beef, braised ham and savoury pies, daubed geese and braised capon, lobster and crayfish, cold roast fowl and cold lamb, potatoes, peas and cauliflower. There were mounted pastries, dishes of jellies and creams, over a thousand side dishes, nearly five hundred sauce boats brimming with lobster sauce, butter sauce and mint."

Coronation Banquet of George IV, 1821 Westminster Hall was also the scene of George IV's coronation banquet, the last one held there, although many of us certainly remember the Diamond Jubilee luncheon served there in 2012. As his reputation as a Voluptuary (see Gillray, below) might predict, George IV presided over an expensive and (melo)dramatic pageant for his coronation, which is probably best remembered for locking the door against his estranged wife, who was prepared to be crowned as queen. One of the accounts of the banquet enumerated some of the dishes served, "soups including turtle, salmon, turbot, and trout, venison and veal, mutton and beef, braised ham and savoury pies, daubed geese and braised capon, lobster and crayfish, cold roast fowl and cold lamb, potatoes, peas and cauliflower. There were mounted pastries, dishes of jellies and creams, over a thousand side dishes, nearly five hundred sauce boats brimming with lobster sauce, butter sauce and mint.".

A Voluptuary under the horrors of Digestion, James Gillray, 1792British Museum This post is just nibble (pun intended) of the delights in Suzanne Groom's new book, At the King's Table. I will add that the sponsors of her talk had the good taste to serve cheese and crackers and a small glass of wine rather than compete with royalty!

A Voluptuary under the horrors of Digestion, James Gillray, 1792British Museum This post is just nibble (pun intended) of the delights in Suzanne Groom's new book, At the King's Table. I will add that the sponsors of her talk had the good taste to serve cheese and crackers and a small glass of wine rather than compete with royalty!Soon, an account of an exhibition at the Newberry Library concerning the American Civil War -- including the role of Great Britain

Published on October 30, 2013 00:30

October 28, 2013

Victoria Explores Euston/St. Pancras

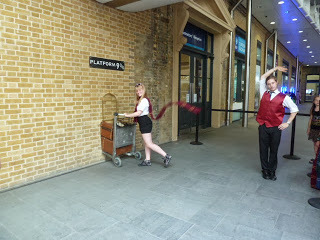

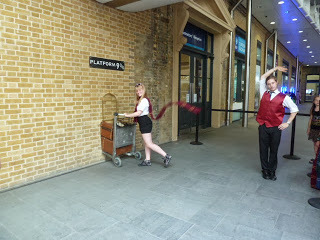

On a warm morning last July, Ed and I returned to London from our marvelous foray into East Anglia. Ed was still worried about his sore foot and not too enthused about running around in London for the rest of our trip. So we decided to stay close to "home" for the afternoon. On our way out of the King's Cross RR Station we saw this cute display of Platform 9 3/4 where the students at Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry leave London in the Harry Potter books.

Outside, the Northern Hotel, next to Kings Cross has been attractively renovated.

Outside, the Northern Hotel, next to Kings Cross has been attractively renovated.

St. Pancras Station And next door to King's Cross and the Northern Hotel is St. Pancras, now the terminal for the Eurostar trains to Paris and Brussels. As such, it has caused a dramatic gentrification in the neighborhood. Almost all the buildings nearby along Euston Road were wrapped in scaffolding and cranes pierced the skies everywhere. We saw many signs for the offices of international conglomerates.

St. Pancras Station And next door to King's Cross and the Northern Hotel is St. Pancras, now the terminal for the Eurostar trains to Paris and Brussels. As such, it has caused a dramatic gentrification in the neighborhood. Almost all the buildings nearby along Euston Road were wrapped in scaffolding and cranes pierced the skies everywhere. We saw many signs for the offices of international conglomerates.

through the traffic to Chalton Street We found several pubs and bistros on Chalton Street beside our hotel, and I wondered how long this thoroughfare of little shops and newsstands could withstand the pressure of rising prices and new construction all around. Seems sad they might have to move and be replaced by the same chains one sees in Piccadilly. That's the down side of gentrification.

through the traffic to Chalton Street We found several pubs and bistros on Chalton Street beside our hotel, and I wondered how long this thoroughfare of little shops and newsstands could withstand the pressure of rising prices and new construction all around. Seems sad they might have to move and be replaced by the same chains one sees in Piccadilly. That's the down side of gentrification.

St. Pancras Hotel The upside of gentrification is the renovation of great old buildings like the Northern Hotel and the St. Pancras Hotel. a fantasy of Victorian wretched excess that is quite charming for all its Neo-Gothic extremes. Here are a few shots of the exterior décor.

St. Pancras Hotel The upside of gentrification is the renovation of great old buildings like the Northern Hotel and the St. Pancras Hotel. a fantasy of Victorian wretched excess that is quite charming for all its Neo-Gothic extremes. Here are a few shots of the exterior décor.

I assume the Hotel, a very posh place, has antidotes to nightmares caused by these gargoyles. The architect of the hotel, opened originally in 1868 as the Midland Grand Hotel, was Sir George Gilbert Scott (1811-1878), who is also responsible for the Albert Memorial in Hyde Park and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office in Whitehall at King Charles Street. Sir George would be proud of the restoration I am sure. Although we could hardly afford to stay there, we did enjoy a wonderful luncheon in the restaurant called "The Booking Office."

I assume the Hotel, a very posh place, has antidotes to nightmares caused by these gargoyles. The architect of the hotel, opened originally in 1868 as the Midland Grand Hotel, was Sir George Gilbert Scott (1811-1878), who is also responsible for the Albert Memorial in Hyde Park and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office in Whitehall at King Charles Street. Sir George would be proud of the restoration I am sure. Although we could hardly afford to stay there, we did enjoy a wonderful luncheon in the restaurant called "The Booking Office."

Vicky, Rev. Susan, Dr. Jim, and Ed

Vicky, Rev. Susan, Dr. Jim, and Ed

View from Pullman St. Pancras Hotel of the British Library (foreground) and the St. Pancras Hotel and Station in Euston Road

View from Pullman St. Pancras Hotel of the British Library (foreground) and the St. Pancras Hotel and Station in Euston Road

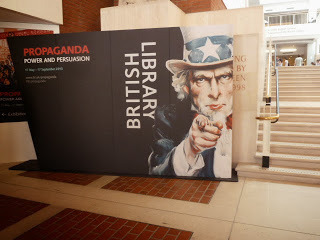

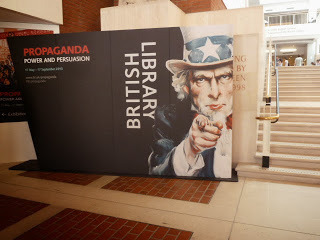

Exhibit in the British Library In the courtyard of the BL, an people were enjoying the warm afternoon, sipping cool drinks, reading, talking and/or checking their mobiles. We visited the Propaganda exhibit, then walked around the permanent exhibit where there are copies of the Magna Carta, ancient maps, the Beatles' songs, Jane Austen's desk, and other fascinating manuscripts and objects.

Exhibit in the British Library In the courtyard of the BL, an people were enjoying the warm afternoon, sipping cool drinks, reading, talking and/or checking their mobiles. We visited the Propaganda exhibit, then walked around the permanent exhibit where there are copies of the Magna Carta, ancient maps, the Beatles' songs, Jane Austen's desk, and other fascinating manuscripts and objects.

Sir Joseph Banks (1743-1820)by sculptor Anne Seymour DamerAmong the busts of the Library Founders.

Sir Joseph Banks (1743-1820)by sculptor Anne Seymour DamerAmong the busts of the Library Founders.

In the gift/book shop

In the gift/book shop

Looking at our tall hotel from the BL Courtyard

Looking at our tall hotel from the BL Courtyard

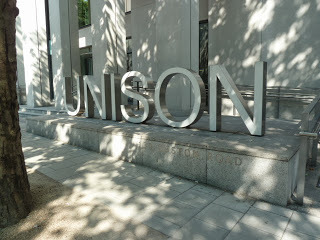

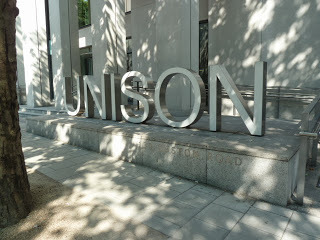

The Elizabeth Garret Anderson Hospital A little farther west on Euston Road, near Euston Station, is the building above, which was built by Britain's first woman physician and surgeon. It has become part of the new National Headquarters for the public service trade union Unison. Elizabeth Garret Anderson's life story is fascinating. Check it out here.

The Elizabeth Garret Anderson Hospital A little farther west on Euston Road, near Euston Station, is the building above, which was built by Britain's first woman physician and surgeon. It has become part of the new National Headquarters for the public service trade union Unison. Elizabeth Garret Anderson's life story is fascinating. Check it out here.

Two more neighborhood institutions were well worth our visit. The St. Pancras Church at the corner of Euston Road and Upper Woburn Place was constructed in 1819-1822 and designed by architect William Inwood and his son, Henry Inwood.

Two more neighborhood institutions were well worth our visit. The St. Pancras Church at the corner of Euston Road and Upper Woburn Place was constructed in 1819-1822 and designed by architect William Inwood and his son, Henry Inwood.

The building was modeled on two Athens landmarks from the Acropolis: the Tower of the Winds and the Erechtheum, the latter with its Ionic columns and the Porch of the Caryatids.

The building was modeled on two Athens landmarks from the Acropolis: the Tower of the Winds and the Erechtheum, the latter with its Ionic columns and the Porch of the Caryatids.

Porch of the Caryatids

Porch of the Caryatids

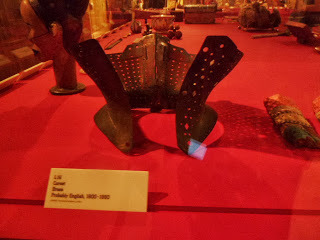

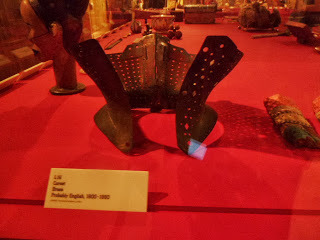

The Apse, St. Pancras Church The final neighborhood attraction we visited was the fascinating premises of the Wellcome Collection. The objects displayed were acquired by Sir Henry Wellcome (1845-1936), who explored the relationship of art, medicine, and the human body.

The Apse, St. Pancras Church The final neighborhood attraction we visited was the fascinating premises of the Wellcome Collection. The objects displayed were acquired by Sir Henry Wellcome (1845-1936), who explored the relationship of art, medicine, and the human body.

beakers, two of 100's

beakers, two of 100's

Iron Corset

Iron Corset

A Chastity Belt of iron and velvet The Wellcome Collection advertises itself as "the free destination for the incurably curious." Ed ad I found this a perfect description of the odd assortment of items in the museum. Also part of the Wellcome Trust are educational organizations and a medical library. If you are looking for the unusual in London, you will find it here. We enjoyed this Euston Road neighborhood, with its diverse institutions and attractions.

A Chastity Belt of iron and velvet The Wellcome Collection advertises itself as "the free destination for the incurably curious." Ed ad I found this a perfect description of the odd assortment of items in the museum. Also part of the Wellcome Trust are educational organizations and a medical library. If you are looking for the unusual in London, you will find it here. We enjoyed this Euston Road neighborhood, with its diverse institutions and attractions.

View of the City from the Pullman Hotel, St. Paul's Cathedral at the far right in the distance My visit to the Wellington Arch is coming soon.

View of the City from the Pullman Hotel, St. Paul's Cathedral at the far right in the distance My visit to the Wellington Arch is coming soon.

Outside, the Northern Hotel, next to Kings Cross has been attractively renovated.

Outside, the Northern Hotel, next to Kings Cross has been attractively renovated.

St. Pancras Station And next door to King's Cross and the Northern Hotel is St. Pancras, now the terminal for the Eurostar trains to Paris and Brussels. As such, it has caused a dramatic gentrification in the neighborhood. Almost all the buildings nearby along Euston Road were wrapped in scaffolding and cranes pierced the skies everywhere. We saw many signs for the offices of international conglomerates.

St. Pancras Station And next door to King's Cross and the Northern Hotel is St. Pancras, now the terminal for the Eurostar trains to Paris and Brussels. As such, it has caused a dramatic gentrification in the neighborhood. Almost all the buildings nearby along Euston Road were wrapped in scaffolding and cranes pierced the skies everywhere. We saw many signs for the offices of international conglomerates.

through the traffic to Chalton Street We found several pubs and bistros on Chalton Street beside our hotel, and I wondered how long this thoroughfare of little shops and newsstands could withstand the pressure of rising prices and new construction all around. Seems sad they might have to move and be replaced by the same chains one sees in Piccadilly. That's the down side of gentrification.

through the traffic to Chalton Street We found several pubs and bistros on Chalton Street beside our hotel, and I wondered how long this thoroughfare of little shops and newsstands could withstand the pressure of rising prices and new construction all around. Seems sad they might have to move and be replaced by the same chains one sees in Piccadilly. That's the down side of gentrification.

St. Pancras Hotel The upside of gentrification is the renovation of great old buildings like the Northern Hotel and the St. Pancras Hotel. a fantasy of Victorian wretched excess that is quite charming for all its Neo-Gothic extremes. Here are a few shots of the exterior décor.

St. Pancras Hotel The upside of gentrification is the renovation of great old buildings like the Northern Hotel and the St. Pancras Hotel. a fantasy of Victorian wretched excess that is quite charming for all its Neo-Gothic extremes. Here are a few shots of the exterior décor.

I assume the Hotel, a very posh place, has antidotes to nightmares caused by these gargoyles. The architect of the hotel, opened originally in 1868 as the Midland Grand Hotel, was Sir George Gilbert Scott (1811-1878), who is also responsible for the Albert Memorial in Hyde Park and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office in Whitehall at King Charles Street. Sir George would be proud of the restoration I am sure. Although we could hardly afford to stay there, we did enjoy a wonderful luncheon in the restaurant called "The Booking Office."

I assume the Hotel, a very posh place, has antidotes to nightmares caused by these gargoyles. The architect of the hotel, opened originally in 1868 as the Midland Grand Hotel, was Sir George Gilbert Scott (1811-1878), who is also responsible for the Albert Memorial in Hyde Park and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office in Whitehall at King Charles Street. Sir George would be proud of the restoration I am sure. Although we could hardly afford to stay there, we did enjoy a wonderful luncheon in the restaurant called "The Booking Office."

Vicky, Rev. Susan, Dr. Jim, and Ed

Vicky, Rev. Susan, Dr. Jim, and Ed

View from Pullman St. Pancras Hotel of the British Library (foreground) and the St. Pancras Hotel and Station in Euston Road

View from Pullman St. Pancras Hotel of the British Library (foreground) and the St. Pancras Hotel and Station in Euston Road

Exhibit in the British Library In the courtyard of the BL, an people were enjoying the warm afternoon, sipping cool drinks, reading, talking and/or checking their mobiles. We visited the Propaganda exhibit, then walked around the permanent exhibit where there are copies of the Magna Carta, ancient maps, the Beatles' songs, Jane Austen's desk, and other fascinating manuscripts and objects.

Exhibit in the British Library In the courtyard of the BL, an people were enjoying the warm afternoon, sipping cool drinks, reading, talking and/or checking their mobiles. We visited the Propaganda exhibit, then walked around the permanent exhibit where there are copies of the Magna Carta, ancient maps, the Beatles' songs, Jane Austen's desk, and other fascinating manuscripts and objects.

Sir Joseph Banks (1743-1820)by sculptor Anne Seymour DamerAmong the busts of the Library Founders.

Sir Joseph Banks (1743-1820)by sculptor Anne Seymour DamerAmong the busts of the Library Founders.

In the gift/book shop

In the gift/book shop

Looking at our tall hotel from the BL Courtyard

Looking at our tall hotel from the BL Courtyard

The Elizabeth Garret Anderson Hospital A little farther west on Euston Road, near Euston Station, is the building above, which was built by Britain's first woman physician and surgeon. It has become part of the new National Headquarters for the public service trade union Unison. Elizabeth Garret Anderson's life story is fascinating. Check it out here.

The Elizabeth Garret Anderson Hospital A little farther west on Euston Road, near Euston Station, is the building above, which was built by Britain's first woman physician and surgeon. It has become part of the new National Headquarters for the public service trade union Unison. Elizabeth Garret Anderson's life story is fascinating. Check it out here.

Two more neighborhood institutions were well worth our visit. The St. Pancras Church at the corner of Euston Road and Upper Woburn Place was constructed in 1819-1822 and designed by architect William Inwood and his son, Henry Inwood.

Two more neighborhood institutions were well worth our visit. The St. Pancras Church at the corner of Euston Road and Upper Woburn Place was constructed in 1819-1822 and designed by architect William Inwood and his son, Henry Inwood.

The building was modeled on two Athens landmarks from the Acropolis: the Tower of the Winds and the Erechtheum, the latter with its Ionic columns and the Porch of the Caryatids.

The building was modeled on two Athens landmarks from the Acropolis: the Tower of the Winds and the Erechtheum, the latter with its Ionic columns and the Porch of the Caryatids.

Porch of the Caryatids

Porch of the Caryatids

The Apse, St. Pancras Church The final neighborhood attraction we visited was the fascinating premises of the Wellcome Collection. The objects displayed were acquired by Sir Henry Wellcome (1845-1936), who explored the relationship of art, medicine, and the human body.

The Apse, St. Pancras Church The final neighborhood attraction we visited was the fascinating premises of the Wellcome Collection. The objects displayed were acquired by Sir Henry Wellcome (1845-1936), who explored the relationship of art, medicine, and the human body.

beakers, two of 100's

beakers, two of 100's

Iron Corset

Iron Corset

A Chastity Belt of iron and velvet The Wellcome Collection advertises itself as "the free destination for the incurably curious." Ed ad I found this a perfect description of the odd assortment of items in the museum. Also part of the Wellcome Trust are educational organizations and a medical library. If you are looking for the unusual in London, you will find it here. We enjoyed this Euston Road neighborhood, with its diverse institutions and attractions.

A Chastity Belt of iron and velvet The Wellcome Collection advertises itself as "the free destination for the incurably curious." Ed ad I found this a perfect description of the odd assortment of items in the museum. Also part of the Wellcome Trust are educational organizations and a medical library. If you are looking for the unusual in London, you will find it here. We enjoyed this Euston Road neighborhood, with its diverse institutions and attractions.

View of the City from the Pullman Hotel, St. Paul's Cathedral at the far right in the distance My visit to the Wellington Arch is coming soon.

View of the City from the Pullman Hotel, St. Paul's Cathedral at the far right in the distance My visit to the Wellington Arch is coming soon.

Published on October 28, 2013 00:30

October 25, 2013

Artist Thomas Sully in Milwaukee

Victoria here, reporting on a wonderful exhibition at my local hang-out, the Milwaukee Art Museum. Last year about this time I was observing the wonderful exhibition at the MAM from London's Kenwood House. Click here if you need a reminder.

This autumn we are fortunate to have a gathering of works from many museums for Thomas Sully: Painted Performance. After it closes in Milwaukee in January, the exhibition will travel to the San Antonio Museum of Art February 7 through May 11, 2014.

Lady with a Harp Eliza Ridgeway, 1818, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. This is one of my favorite paintings in Washington and I usually breeze by to say hello on my annual forays to the capital. Now here she is in my front yard.

Lady with a Harp Eliza Ridgeway, 1818, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. This is one of my favorite paintings in Washington and I usually breeze by to say hello on my annual forays to the capital. Now here she is in my front yard.

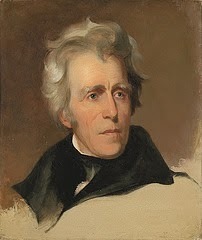

Andrew Jackson, 1845National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. The Andrew Jackson portrait is very familiar to all Americans as the inspiration of the etching on the $20 bill.

Andrew Jackson, 1845National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. The Andrew Jackson portrait is very familiar to all Americans as the inspiration of the etching on the $20 bill.

Thomas Sully (1783–1872) was born in Lincolnshire, England, to a family in the theatrical business. In 1792, they settled in Charleston, South Carolina. Though young Tom often acted, his skills in sketching and painting were soon evident. Eventually he worked with his brother Lawrence, also a painter. Tom moved around from Richmond, VA, to New York, and for a while to Boston to study with Gilbert Stuart, perhaps the young republic's most renowned artist. Sully settled in Philadelphia in 1806; there he stayed for the rest of his life, other than time in 1809 studying in London with Benjamin West and later a London trip to paint the young Queen Victoria in 1837-38.

Thomas Sully (1783–1872) was born in Lincolnshire, England, to a family in the theatrical business. In 1792, they settled in Charleston, South Carolina. Though young Tom often acted, his skills in sketching and painting were soon evident. Eventually he worked with his brother Lawrence, also a painter. Tom moved around from Richmond, VA, to New York, and for a while to Boston to study with Gilbert Stuart, perhaps the young republic's most renowned artist. Sully settled in Philadelphia in 1806; there he stayed for the rest of his life, other than time in 1809 studying in London with Benjamin West and later a London trip to paint the young Queen Victoria in 1837-38.

Queen Victoria, Metropolitan Museum of Art Other versions of this painting hang in the Wallace Collection in London and the Royal Collection as well. Below, a full length version, not in this exhibition.

Queen Victoria, Metropolitan Museum of Art Other versions of this painting hang in the Wallace Collection in London and the Royal Collection as well. Below, a full length version, not in this exhibition.

Queen Victoria, 1838Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC Among the amazing 2300 pictures Sully painted are many American politicians and other citizens, both men and women. The focus of this MAM exhibition is performance, particularly on the stage.

Queen Victoria, 1838Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC Among the amazing 2300 pictures Sully painted are many American politicians and other citizens, both men and women. The focus of this MAM exhibition is performance, particularly on the stage.

George Frederick Cooke, in the role of Shakespeare's Richard III Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts

George Frederick Cooke, in the role of Shakespeare's Richard III Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts

Famed Actress Frances Anne (Fanny) Kemble as Beatrice, 1833Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts

Famed Actress Frances Anne (Fanny) Kemble as Beatrice, 1833Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts

Sarah Esther Hindman as Little Red Riding Hood, 1833 The Maryland State Archives, Photo by Harry Connolly Sully not only painted actors; he also produced many paintings illustrating scenes from books and other "Fancy" pictures, many of which were reproduced for widespread purchase and display in everyday homes.

Sarah Esther Hindman as Little Red Riding Hood, 1833 The Maryland State Archives, Photo by Harry Connolly Sully not only painted actors; he also produced many paintings illustrating scenes from books and other "Fancy" pictures, many of which were reproduced for widespread purchase and display in everyday homes.

Prison Scene from James Fenimore Cooper's "The Pilot", 1841Birmingham (AL) Museum of Art

Prison Scene from James Fenimore Cooper's "The Pilot", 1841Birmingham (AL) Museum of Art

Little Nell Asleep in Dickens' The Old Curiosity ShopFree Library of Philadelphia

Little Nell Asleep in Dickens' The Old Curiosity ShopFree Library of Philadelphia

Cinderella at the Kitchen Fire, 1843Dallas Museum of Art Among Thomas Sully's most prized paintings are his many portraits, and particularly the adorable lad below, beloved to generations of MFA visitors.

Cinderella at the Kitchen Fire, 1843Dallas Museum of Art Among Thomas Sully's most prized paintings are his many portraits, and particularly the adorable lad below, beloved to generations of MFA visitors.

The Torn Hat, 1820© 2013, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The Torn Hat, 1820© 2013, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Major Thomas Biddle, 1818Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia I am looking forward to rambling around among these pictures many times in the next couple of months. Sully's work has a luminosity I love. When this blog visited the Look of Love exhibition in Birmingham, we became acquainted with Tom Sully, great , great, great grandson of Thomas Sully and himself a renowned artist. For our interview with Tom, click here. This is the first Thomas Sully retrospective in thirty years, showing about eighty paintings. Thomas Sully: Painted Performance is organized by the Milwaukee Art Museum, co-curated by Dr. William Keyse Rudolph, the Museum’s Dudley J. Godfrey Jr. Curator of American Art and Decorative Arts and Director of Exhibitions, and Dr. Carol Eaton Soltis, Project Associate Curator of American Art, Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Major Thomas Biddle, 1818Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia I am looking forward to rambling around among these pictures many times in the next couple of months. Sully's work has a luminosity I love. When this blog visited the Look of Love exhibition in Birmingham, we became acquainted with Tom Sully, great , great, great grandson of Thomas Sully and himself a renowned artist. For our interview with Tom, click here. This is the first Thomas Sully retrospective in thirty years, showing about eighty paintings. Thomas Sully: Painted Performance is organized by the Milwaukee Art Museum, co-curated by Dr. William Keyse Rudolph, the Museum’s Dudley J. Godfrey Jr. Curator of American Art and Decorative Arts and Director of Exhibitions, and Dr. Carol Eaton Soltis, Project Associate Curator of American Art, Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Published on October 25, 2013 00:30

October 23, 2013

The Jane Austen Society in Minneapolis

Seven hundred fans and scholars met in Minneapolis at the end of September for immersion in All Things Jane. Victoria here, relating my experience celebrating two hundred years of Pride and Prejudice with so many of those who love it too. Many thanks to Dave O'Brien for the use of his excellent photos, more of which can be seen on the JASNA-WI website.

Minneapolis, 2013 As always at an AGM, part of the fun is touring the city and surroundings...and we had perfect weather to enjoy such treats as the Guthrie Theatre, the Mill Museum, tours devoted to F. Scott Fitzgerald and Sherlock Holmes, plus the art museums and pub crawls.

Minneapolis, 2013 As always at an AGM, part of the fun is touring the city and surroundings...and we had perfect weather to enjoy such treats as the Guthrie Theatre, the Mill Museum, tours devoted to F. Scott Fitzgerald and Sherlock Holmes, plus the art museums and pub crawls.

The Emporium Another popular feature of an AGM the Emporium where JASNA chapters and commercial providers have their sales tables. Books, hats, fans, pens and paper, English antique tea cups, all sorts of temptations abound.

The Emporium Another popular feature of an AGM the Emporium where JASNA chapters and commercial providers have their sales tables. Books, hats, fans, pens and paper, English antique tea cups, all sorts of temptations abound. Kathy O'Brien entertains the Queen, Liz Cooper and a customer forJASNA-WI's 2014 Calendar. To order yours, click here.

Kathy O'Brien entertains the Queen, Liz Cooper and a customer forJASNA-WI's 2014 Calendar. To order yours, click here.

Below, editor Tim Bullamore collects subscribers to Jane Austen's Regency World magazine.

For more information on JARW, click here.

For more information on JARW, click here.

Jane Austen Books is always a popular vendor.

Jane Austen Books is always a popular vendor.

The Regency Room featured the antique collection of author Candice Hern, left with JASNA President Iris Lutz (in May 2013 in Madison, WI)

The Regency Room featured the antique collection of author Candice Hern, left with JASNA President Iris Lutz (in May 2013 in Madison, WI)

For more on Candice's Collections, click here.

For more on Candice's Collections, click here. As in the past few years, the JASNA AGM events have become so numerous that many are held on the day before the official Keynote. In additions to tours and workshops, Thursday's speakers included Candice Hern on Regency Magazines; Bruce Richardson on the History of Tea and Jane Austen; a High Tea and Fashion Show; and Curtain Raiser Jocelyn Harris speaking on "Introducing Elizabeth Bennet."

As in the past few years, the JASNA AGM events have become so numerous that many are held on the day before the official Keynote. In additions to tours and workshops, Thursday's speakers included Candice Hern on Regency Magazines; Bruce Richardson on the History of Tea and Jane Austen; a High Tea and Fashion Show; and Curtain Raiser Jocelyn Harris speaking on "Introducing Elizabeth Bennet."

William Phillips of Chicago, a JASNA favorite speaker, spoke on card games: "Pride, Prejudice and Piquet" Friday morning was also crowded with tours, workshops dance lessons and excellent presentations.

William Phillips of Chicago, a JASNA favorite speaker, spoke on card games: "Pride, Prejudice and Piquet" Friday morning was also crowded with tours, workshops dance lessons and excellent presentations.

Sandy Lerner spoke on "Pen and Parsimony: Carriages in the Novels of Jane Austen"

Sandy Lerner spoke on "Pen and Parsimony: Carriages in the Novels of Jane Austen"

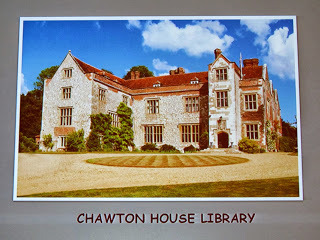

Steve Lawrence, CEO of Chawton House Library, updated us on events there.

Steve Lawrence, CEO of Chawton House Library, updated us on events there.

I attended the Frances Burney Society AGM, Luncheon, and excellent talk by Dr. Lorna Clark who spoke about Burney's private writings in the context of her work editing a new edition of two volumes of The Court Journals and Letters of Frances Burney.

I attended the Frances Burney Society AGM, Luncheon, and excellent talk by Dr. Lorna Clark who spoke about Burney's private writings in the context of her work editing a new edition of two volumes of The Court Journals and Letters of Frances Burney.

Dr. Lorna Clark

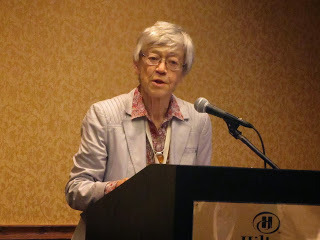

Dr. Lorna Clark  The Opening Plenary Session of the 2013 JASNA AGM,The Carol Medine Moss Keynote Lecture,a very entertaining and insightful session.

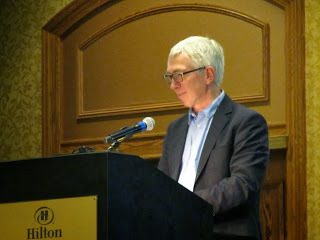

The Opening Plenary Session of the 2013 JASNA AGM,The Carol Medine Moss Keynote Lecture,a very entertaining and insightful session. Professor James Mullan of University College LondonSpeechless in Pride and Prejudiceauthor of What Matters in Jane Austen: 20 Crucial Puzzles Solved

Professor James Mullan of University College LondonSpeechless in Pride and Prejudiceauthor of What Matters in Jane Austen: 20 Crucial Puzzles Solved

My turn for a Break-out Session

My turn for a Break-out Session

She is SERIOUS!ABC Nightline filmed my entire presentation, but I fear I ended up on the cutting room floor.

She is SERIOUS!ABC Nightline filmed my entire presentation, but I fear I ended up on the cutting room floor.