Andrew Chatora's Blog, page 2

July 2, 2023

Who Needs a Writer? There is More to Writing than Dollars and Cents

Art is a higher power. Art, which literature is a part of, is linked to the initial forces that created the world. The creative production of reality through words and images is understood by some cultures to be the elementary first cause, the force that brought our universe into being. In that regard, the artist becomes a God, a ruler of sorts, though I do not consider myself to be the former.

Think about Ezeulu, the headstrong priest who clutches onto a fallen god in the disenchanted world of Chinua Achebe’s novel, Arrow of God. He is an artist-type. In one of his prayers to the God, Ulu, Ezeulu asks to be turned into an arrow in the bow of a higher power. When he is released at the perfect moment, he would then hit the target perfectly. Just that would be enough!

This is in keeping with Achebe’s well known view that every artist is a committed man or woman. Achebe says all that the artist has to ask is: On whose side do I want to be committed? Achebe is sweet, he goes on, after the tenor of Igbo cosmology: “Wherever something stands, something else will stand besides it.” In a world here is the oppressor and the oppressed. The artist’s work is laid.

But there is the other daunting question on the lips of many, the somewhat Philistine byword: ‘‘Why write when you can’t make a living out of it?’’ is one an artist gets to rehearse for more than his own readings. I have run into it many times in my daily labor of love for letters. As if the consuming passion for literature spares you a place in your heart for the famous thirty pieces of silver. I am not faulting colleagues who have been able to count numbers from our mutual trade, but I want to think of money made out of writing as a welcome bonus.

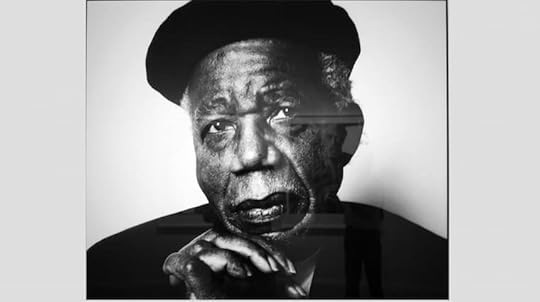

Chinua Achebe. Photo: Cliff/Flickr/Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0)/No changes made

Writing pays. There is no question about it. Things Fall Apart, Achebe’s pioneering novel is widely estimated to have sold millions of copies.

The late Nobel Prize winning Gabriel García Márquez, who died on 17 April 2014, was considered by many as the greatest author ever in the Spanish language. Marquez’s most successful work as a writer is the long and expansive novel, One Hundred Years of Solitude which became a huge success in the years after its publication in 1967, selling more than 10 million copies in more than 30 languages!Itmade García Márquez a leader of the Latin American literary “boom” and an international phenomenon.

Writing begins as a passion, then it becomes an investment, and for some, it may eventually result in huge returns

And yet these people and many others; Sydney Sheldon, Danielle Steel, Barbara Cartland, Steven King, did not set out on day one to write to make money! It is said that 95% of the money in writing is made by 5% of the writers. It means that writing begins as a passion, then it becomes an investment, and for some, it may eventually result in huge returns.

Vicissitudes of Life as a Writer

‘‘Do you enjoy writing?’’ Now that should be the starting point. For me, the mere enjoyment of my writerly craft is all the initial justification I need to write. Charles Mungoshi once said, “The landscape, the physical life of the book became much more alive, much more there because I was living it as I was writing it and I have never felt as blessed as I felt writing (or re-writing) Waiting for the Rain…”

Mungoshi’s works have been influential school texts since the 1980s, when his classic novel, Waiting for the Rain, became the first set text by an African writer.

I am not yet at that stage where I write to live. I live to write amongst other chores. In return, writing, like the many other things that I do, makes me live on.

I often think about the prolific American writer, John Grisham who sold millions of copies of his second novel, The Firm. He took three years to write his first book, A Time to Kill which got published in June 1988 after being rejected by 28 publishers! Wynwood Press, an unknown publisher, agreed to give it a modest 5,000 copy printing. The day after Grisham completed A Time to Kill, he began work on his second novel, The Firm. He did that before realising much from the first book. He says that right from the beginning, he wanted to make a brand and what kept him going was just the desire to write. Then boom, the money started to come. The Firm is a 1991 legal thriller and the second novel by John Grisham. It was his first widely recognised book and, in 1993, after it sold 1.5 million copies, was made into a film starring Tom Cruise and Gene Hackman.

As a writer, I also love the fact that I am leaving something behind, even if it’s only a fart in the universe, better still a by-lined footprint. In this sense you could say I write to live. I write to live forever.

Equally, I do realise, that writing means different things to different scribes, and each has to be respected for their motivational compass.

Of all the words of Kurt Vonnegut’s Of Mice and Men, the saddest got to be, ‘‘It might have been.’’ As writers, we got to hold society to what might have been. I like to see myself in this realm, with my books, short stories and literary essays, affirming to me that I have done my fair bit, taking aim at those spreading bigotry and xenophobia in post-Brexit Britain.

I quit my PhD to devote more time to writing. The PhD had become a dispirited performance whereas writing makes me alive

I have had a taste of backlash already with cancel culture and, of course, the trusty reminder, “You should be grateful, this country gave you a home and a safe haven. Careful, you don’t bite the hand that feeds you.” As if I am here illegally and the host country is also not benefitting from my manpower.

“So you got to hold down your day job to write at all?” That is the other question I’ve had to contend with.

Writing is one of my oldest hobbies. Now that I have started publishing, it’s becoming something more.

I actually quit my PhD to devote more time to writing. It had become a dispirited performance whereas writing makes me alive.

There I was interacting with unknown readers from different parts of the world, in some cases sparring over my content, the way I represented the gender divide, identity politics, what have you. I loved the vibes and kicks this gave me. Perhaps this was my eureka moment when the penny dropped and I realised writing was for me and beckoning I give it my all, which is what I have done.

I’m aware my finances would be better if I took some soulless boring data entry job, but my spirit would shrivel and die like a forgotten potted plant. I measure my worth by lives affected. And writing affords me just that.

One is always best off doing what one truly loves. John Grisham has this to say: “I find my story, find its voice, its people, its pace, and I retreat into my attic for six hours a day and shut out everything but family. As I write, I don’t think about the readers, the sales, the movies. I think about the story. If I get it right, everything else falls into place.”

To Gift Mheta my friend of many years, thank you for the inspirational message here which has kept me going: ‘‘Keep writing, Chatora.’’

Some of the one-liners over the years. I’ve taken up the “Why we write” conversation with fellow writers and naysayers. The many responses I got have been nigh instructive at times anecdotal as exchanges below shows.

‘‘I support a family of eight as a writer. People can believe what they wish.

Of course, it’s a terrible financial choice. But if you’re doing it with no money expectations, what’s the problem?’’

‘‘The problem is people who are out of writing think you’re raking in the thousands, but the reality obtaining is far from that.’’

‘‘Ignore the party poopers. I found a way to earn a 6-figure sum the first four months of writing. There are many ways to make lots of money. Ignore them. They’re jealous they can’t be free or doing what makes them happy.’’

My uncle told me that once.

My own father also had these words of ‘‘encouragement’’ for me: ‘‘Writing isn’t a real job. It won’t pay the bills. Who wants to read the exact same shit every other two-bit author is writing? Not me, I’m afraid. Got better things to do.’’

‘‘Cheers dad! Thanks for the support.’’ What else can I say?

Some of my writer colleagues argue: Those naysayers’ comments may be true. Everyone wants to publish a book with dreams of making money. There is much more to it than meets the eye. Publishers will not tell you the struggles you face because they want your money.

I have a day job like that I trained for, and I do that. I also write novels and short stories. I write what I love and what I want and don’t worry about money or about what other people think. One great writer once advised: “I hate to give advice. It’s so easy to dispense and even easier to ignore. Get a real job in a real career and stake your claim in your chosen field, then write as a serious hobby.”

Perhaps, it is best to draw insight from Arthur Miller who once remarked: ‘‘Do not be beguiled into thinking that that which is without profit is without value.’’

Do not be beguiled into thinking that that which is without profit is without value.

I suppose some people have no idea what it means for someone to pursue their passion. I feel sorry for the miserable lives they must be living.

Royalties come in dribs and drabs and they’re minuscule for want of a better word.

A colleague opined:

I’ve been writing full time for 12 years now. I answer to nobody. My time is my own. I don’t need to commute, and I live in a house on the shore with a great view. Okay, I’m not super-rich in money, but I’m rich in all the ways that matter to me.

Any route can potentially be a bad choice, but you can’t let that stop you from making choices. I wonder how many books are read by these folks giving you this advice. I don’t currently earn as much as I did working full-time in software management, but tell you what? I’m 100 times happier.

There are many jobs for writers. Companies pay good money for people who can write. Besides, there are always exceptions, one may write a best seller novel and be like J.K. Rowling. She made a billions of dollars. So, what’s not to like there?

There’s even a hilarious Einstein meme on Twitter: ‘‘Stop listening to negative people. They have a problem for every solution you may come up with.’’

Any kind of art is a “bad financial choice” as a full-time job. But if you are doing art just for the money, it’s silly because there are better and easier ways to make money.

Perhaps none sums it better as my other respected colleague; fellow writer Josh, he remarks:

I don’t care if it makes me money or not. One day, one hundred years from now someone may find something I wrote on a flash drive, and it could inspire them long after my death. Or it could be something that makes someone laugh. Through writing we live on, can’t price that good feeling.

“Get a real job!” They tell me.

Not remotely interested, writing will do me just fine. Actually, I ended up quitting my 9 to 5pm job in favour of writing.

And boy! Ain’t I happy I followed my passion and chose writing in the end. Best decision of my life ever!

Now, let’s do some number crunching. The average income for a writer in the UK is £12,000 per annum. Way below minimum wage. But hold on, the figure is misleading – some earn mega and some, nothing.

Royalties come in dribs and drabs and they’re minuscule

We do it for love, damn it. For a teeny weeny chance at our names and ideas living for longer than we do.

Iconic anti-apartheid South African poet, Donato Francisco Mattera, affectionately known as Don, who passed away Monday 18 July 2022 had a way with words and he wrote with deep passion about freedom, friendship and the dream for a better South Africa in which people of all races coexisted.

In one of his iconic poems, he demonstrates that his poetry was part of his being and the way he felt and responded to the world:

I feel a poem

Thumping deep, deep

I feel a poem inside

wriggling within the membrane

of my soul;

tiny fists beating,

beating against my being

trying to break the navel cord,

crying, crying out

to be born on paper

Thumping

deep, so deeply

I feel a poem,

inside

He felt deeply. He was passionate about the world around him. Don meant an idea, an opinion dying to be spelt out so that one feels at peace again with his environment.

Don was a committed poet, more like David Diop and Agonstinho Neto. Don often felt that, if need be, the poet, the artist, may just have to pay the supreme prize. Coming from a background of strife, segregation, arrest, banning and many ills during apartheid, he saw art not as a luxury but something that often brought the artist to the brink. He felt that “the poet must die” in order to make his or her point.

“The poet must die

her murmuring threatens their survival

her breath could start the revolution;

she must be destroyed…”

The more books you have out there, the bigger the chances to make a living, that’s my theory. My first three books just got published. I hope more will follow.

That’s only good advice if you are only in it for the money. I grew up in a family of avid readers, so I enjoy writing up a good story and seeing each one through until the very end!

Who says, simply picking an occupation for its earning capacity is a guarantee of success? There is the little matter of talent and luck. Ignore them and do what you are good at and gives you the most satisfaction. After all, it’s giving unwanted advice that’s a bad life choice.

I work with colleagues who profess their undying love for writing and yet can’t lift a pen to write anything. Their usual mantra being, ‘‘I’ll do it in retirement when I have more time at my disposal.’’ I don’t know when I will have time or when I won’t, so writing is my business in the now.

What is fulfilling to me, and fellow writers surveyed is; Our craft maybe considered bad financial choices, but bad financial choices are the bedrock of a happy, normal life.

Well, I’m glad James Baldwin, Charles Mungoshi, Dambudzo Marechera and countless others didn’t do something else.

Hitting it big in any of the arts has always been a long shot. But if you hit it, wow!

This whole debate reminds of Ernst Fishers seminal essay: the necessity of art perspective:

Perhaps, “Writing is for writing’s sake” after all.

Most artists do not keep score that way through their painting, sculpting, music, and writing. Birmingham songwriters I know told me: writing songs for the money is like getting married for the sex.

Writing is the heart of communicating accuracy, empathy, history. Few things could be more important than bringing clarity and complexity to the human condition.

To hear Tempus Fugit tell it in The War of Art:

“The artist committing himself to his calling has volunteered for hell, whether he knows it or not. He will be dining for the duration on a diet of isolation, rejection, self-doubt, despair, ridicule, contempt, and humiliation.”

Many more:

If I could please add to this amazing chat brewing, I would share Charles Bukowski’s “Roll the Dice” poem:

If you’re going to try, go all the way

otherwise, don’t even start.

I write because I enjoy it and to me is fulfilling. I just need a lot more sales, which reminds me: I’m not in it for money, am I?

Perhaps, it’s instructive to end by quoting that lowercase icon, bell hooks: ‘‘We write because we respect time and we have that realisation, it may not be on our side, thus we just have to write.’’

We are in it for the long haul. In any case, I was a writer before book advances or royalties, and I will still be a scribe long after this.

As Ernst Fischer puts it, ‘‘Art is necessary in order that man should be able to recognise and change the world. But that is also necessary by virtue of the magic inherent in it.’’

One day I will write about agents, those who can’t write but stifle and crush writer’s dreams! First though, happy writing!

The post Who Needs a Writer? There is More to Writing than Dollars and Cents appeared first on Andrew Chatora .

Navigating New Identities – A Review of Andrew Chatora’s “Diaspora Dreams”

2002 was a year of economic upheaval that resulted in Zimbabweans leaving their country for greener pastures in the diaspora. While Australia, Canada and the United States of America were some destinations chosen by would-be economic refugees, most Zimbabwean emigrants settled in Johannesburg, South Africa – what would be coined Harare South and London, the United Kingdom which was subsequently dubbed Harare North. Therein lay the connotation that Zimbabwe and its people only existed in southern Africa as the Zimbabwean diaspora gained a greater cultural and economic significance. It is to this Harare North that the protagonist of Diaspora Dreams, Kundai Mafirakureva, arrives in the opening paragraph of Andrew Chatora’s debut novella:

I arrived in England on a freezing March morning circa, 2002, aboard a South African Airways flight. I felt nervous as I made the long walk to the immigration exit point. “Good luck,” a young white couple who had been sitting next to me on the eleven-hour flight from Johannesburg, South Africa, politely whispered in my ear, as I prepared to disembark from the plane. Perhaps, they had sussed me out; wet behind the ears, a newbie, out to trying my luck in entering England, for my fair share of what they term the American dream across the transatlantic in the United States.

Since Zimbabwe’s transition into a migratory nation, many Zimbabwean authors have dealt with the migrant question, Brian Chikwava’s Harare North and Sue Nyathi’s Gold Diggers being two stellar examples. Although our protagonist, Kundai first arrives in London (Harare North), ill-luck soon pushes him to Thames Valley where he must endure differing periods of good and bad fortune.

In Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s novel, Americanah, one character, Obinze, remarks that British racism differs from American racism in that Americans have no qualms working with Africans, yet they are averse to living with them, while Brits will readily live with Africans but are averse to working with them. This characterisation is brought to the fore in Diaspora Dreams as Kundai’s white mistress is keen to take up with him but his colleagues are not always as welcoming.

In his first British job, Kundai works illegally as a valet in Aylesbury. As he is a foreigner with no work permit, his colleagues take advantage of this fact to make him do the grunt work and paying him an unfair wage, threatening to report him to immigration authorities if he complains. After getting a permanent visa and getting accreditation as a teacher, Kundai enters Britain’s public school system and although his position there is more formalised and secure, this is not the end of his woes.

While the racism and xenophobia of Kundai’s blue-collar colleagues in the valet service is vicious and blatant, the racism he encounters as a teacher in the public school system is nuanced and thus more sinister as it chips away at him slowly. A disheartening fact as it brings to mind Sidney Poitier’s stellar performance in James Clavell’s To Sir With Love. The 1967 film details the constant microaggressions a black teacher faces while teaching white children in 1960s Britain and highlights the restraint he must apply in being “the good black.”

The grand irony of the setting here is that the petty squabbles and bullying one expects from school children is rather enacted by the pedagogues and disciplinarians entrusted to shape the minds of the youth

Sadly, while Kundai’s students are more respectful in the 2000s, he still faces systemic racism enacted by his fellow colleagues and superiors. The grand irony of the setting here is that the petty squabbles and bullying one expects from school children is rather enacted by the pedagogues and disciplinarians entrusted to shape the minds of the youth. Chatora deftly uses the race and nationalities of Kundai’s colleagues as counterpoints to reinforce and highlight Kundai’s plight and the plight of other teachers of African descent, creating a sense of isolationism as African teachers are tacitly excluded by British teachers and often paid lower wages:

…for here I was, leading a highly successful Media department but without a financial acknowledgment of teaching and learning responsibility (TLR) to go with it, and in scenes reminiscent of my UPS1 threshold application at PRS, I had to approach the head; Simon Reece to rightfully ask what other middle managers were getting. After much haggling and arm-twisting Simon agreed to give me the lowest TLR on the scale! Such is the black man’s experience in English schools. I am not bitter, but I am clearly recounting my experiences for the over two decades I taught in English schools. It is only now, following the dreadful killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis in the United States in 2020, that I feel brave to speak out against some injustices I experienced. As tragic as it is; George Floyd’s cataclysmic death has given me a voice.

Apart from the isolationism Kundai experiences in the work environment, his personal life is a suffocating series of messes that go from bad to worse with each passing chapter. The narrator, Kundai, believes in his Shona values and seeks to uphold them especially while he is in the diaspora as this culture is his only real link to his motherland. In all his decision making and his worldview, Kundai refers to his people, his hunhu (ethos), and his mutupo (totem) characteristics.

Unfortunately, his wife Kay chooses to rather adopt Western individualism and falls prey to materialism, manipulating the court system to her own advantages. Thus, while Kundai and Kay dreamed of the UK as the ‘greener pastries” the change in environment splinters their relationship further. Kundai and Kay’s relationship is a point of departure to look closely at globalisation and the death of the traditional Shona wife. While Kay was in Africa, in a society that was more patriarchal and communal, she and Kundai had fewer marital problems, but when she forges a new individualistic identity for herself in the West, things fall apart. Furthermore, in the traditional Shona household, men are providers and the heads of the families but with the Mafirakureva’s changing fortunes and reversal of roles in the UK, Kundai finds himself emasculated by his wife:

The relationship was lopsided against me. Perhaps, I resented Kay for earning more money than I; quite a huge reversal of fortunes from when we worked in Zimbabwe. Inwardly, I felt like Kay was challenging my masculinity now that her salary was way ahead of mine, and she tried to exercise her newfound dominance in the marriage by sometimes making unilateral decisions without evening asking me my input on matters which also impacted on me. I felt muted in the marriage as if my voice did not matter.

Kundai fails to grasp this new identity resulting in the decline of their marriage. This splinter is further explained in Kundai’s identity as a member of the Gwai (sheep) clan who value humility and as such can neither understand nor entertain Kay’s abrasive behaviour.

Similar themes are echoed in other Zimbabwean novels on the topic of migration, Tendai Huchu’s 2014 novel, The Maestro, the Magistrate, and the Mathematician zooms in on the dislocation experienced by three Zimbabwean expatriates residing in Scotland while Chikwava’s Harare North is an examination of London’s seedier underbelly that is preoccupied with the deterioration of immigrants’ loss of social fabric. Such circumstances tend to have cumulative effects on one’s mental health as shown in Chatora’s Diaspora Dreams. While Kundai acknowledges that living in the UK has damaged his relationships and mental health, his status as an economic refugee does not allow him the privilege of permanently returning to Zimbabwe. This aspect of immigrant life is captured eloquently in Rodolfo Gonzalez’ poem, “I am Joaquin”:

My fathers

Have lost the economic battle

And won the struggle for cultural survival

And now! I must choose between the paradox of victory of the spirit despite physical hunger,

Or to exist in the grasp of American social neurosis,

Sterilization of the soul and a full stomach.

ADVERTISEMENT

The added pressures of Kundai’s immediate and distant relatives increase this pressure as they assume all Zimbabweans in the diaspora are wealthy and thus apply to him for money on a regular basis:

Over the years, it has increasingly been difficult to pinpoint one single reason to why our union soured so quickly. There are moments when I think I get it, but even now I am not so sure anymore. I know the overbearing family demands and expectations from Zimbabwe also ended up taking their toll on the marriage, but to what extend did both of us play a part in the dissolution?

Such overtures are also discussed in NoViolet Bulawayo’s We Need New Names, which tackles the lives of Zimbabwean immigrants living in the United States of America.

There is more to the narrative than just Kundai’s cataclysmic relationships with women as the author deftly paints the touching relationship both Kundai’s children have with their father. These outings are juxtaposed against the protracted custody battles that Kundai and Kay engage in, causing the reader to have sympathy for second generation immigrant children, who often bear the brunt of deteriorating marriages in the diaspora, and thus Kundai ends the chapter on a poignant note:

”There was no need for all this, I didn’t need to prove to anyone that I love my children …my conscience is my master.”

Thus, Kundai’s relationship with his children humanises him by showing him as a fully fleshed human being with different interpersonal relationships and sheds a brighter light on the lives of migrant families.

Apart from the timely themes that Diaspora Dreams touches on, Chatora’s minimalistic/simplistic writing style is reminiscent of Buchi Emecheta’s Second Class Citizen (In the Ditch)

Apart from the timely themes that Diaspora Dreams touches on, Chatora’s minimalistic/simplistic writing style is reminiscent of Buchi Emecheta’s Second Class Citizen (In the Ditch) and the protagonist, Kundai, takes on the persona of the everyman, allowing the reader to cheer for his success and balk at his failures and setbacks. As more and more Zimbabweans leave the southern African nation for greener pastures, stories such as Diaspora Dreams will increasingly become more relevant and pertinent to the Zimbabwean canon as they highlight new identities that Zimbabweans living in the diaspora are forced to assume and new challenges they must overcome to survive.

The post Navigating New Identities – A Review of Andrew Chatora’s “Diaspora Dreams” appeared first on Andrew Chatora .

June 28, 2023

Diaspora Dreams Conceptualizations-Inspiration – Up Close with Andrew Chatora

“Kundai loses it all and his subsequent charmed incantations and chants while in an English madhouse, are the most revealing part of this novel. As a result, Diaspora Dreams could be of interest to those who study the male psyche and manhood. The losing black male is still a dark area, rich with distances to be travelled and depths to be probed.”

Memory Chirere – University of Zimbabwe

Prominent Harare bookseller in Zimbabwe Book Fantastics recently had the chance to catch up with Diaspora Dreams Zimbabwean born author Andrew Chatora resident in England: Excerpts of the interview below:

Book Fantastics (BF): Thanks for this latest addition to the documentation of our living and dying in the dispersion season. I don’t know if you have any idea if this dispersion season will ever end. What pushed you to weave this beautiful piece when we all thought everything to be written of the Zimbabwean diaspora in particular (and African diaspora in general) is over?Andrew Chatora (Chatora): Diaspora Dreams can best be understood within the globalisation prism where as cliched as it may sound but increasingly, the world has become compressed in one global village in (Marshall McLuhan’s) parlance, and I don’t see our journey from the periphery into the centre ending any time soon. Diaspora Dreams is our story, the story of every migrant, regardless of gender, ethnicity, creed or colour and thus for the sake of presenting an authentic narrative, the story had to be told through the portrait of Kundai, the protagonist a Zimbabwean man living in England. Diaspora Dreams was also borne out of the tragic death of George Floyd, a black man murdered in Minnesota, Minneapolis, America by the police in May 2020, in a clear case of heavy handedness, callous police brutality. As fellow immigrants in the diaspora, we are all George Floyd! And his story resonates with our own personal stories, our lived culture.

There are also other variables to Diaspora Dreams. I reckon there was a lacuna both on the Zimbabwean and African diaspora especially in terms of a narrative which recounted what it means to teach English to English kids when you’re from a former colony, as is Kundai’s experience as a black English Teacher in posh Oxfordshire County in England. In fact, one reviewer Memory Chirere of the University of Zimbabwe reviewed Diaspora Dreams as such and reckoned this could be the strongest aspect of the book.

In addition, Diaspora Dreams subverts the often-bandied notion of toxic masculinity through the portrait of Kundai an impotent, emasculated hapless man at the mercy of the wily hands and manipulation of his various paramours. Masculinity is flipped on its head as Kundai recounts work place bullying at the hands of women, whilst he is also on the receiving end of marital violence and trauma from his partners.

Moreso, mental health illness in men is a subject rarely touched on both in Zimbabwean and African literature and as some reviewers have asserted, Diaspora Dreams marks a niche by breaking new grounds in this area tackling mental illness of both Kundai and his wife Kay. So Chatora has made the unspeakable talked about through Literature. Another first!

BF: I’m fascinated by marital relationships as a reader. I open my eyes and try to focus differently when a writer focuses on such. With reference to Kundai and Kay’s squabbles, Mbuya Mafirakureva’s interference, Relate Counselling and probably the courts in their attempts to save the dying marriage do you think there is hope in the intactness of modern families especially in the diaspora?

BF: I’m fascinated by marital relationships as a reader. I open my eyes and try to focus differently when a writer focuses on such. With reference to Kundai and Kay’s squabbles, Mbuya Mafirakureva’s interference, Relate Counselling and probably the courts in their attempts to save the dying marriage do you think there is hope in the intactness of modern families especially in the diaspora?Chatora: Lest I be dubbed a pessimist, but the unfolding realities obtaining in the diaspora are that modern marriages are in a constant state of flux and crisis, thus vulnerable and ready to disintegrate. When we moved into these new lands, we were wet behind the ears without any attendant social and family support structures to cushion us from a new culture, work related stress and the daily grind pressures which sadly impacted and continues to have a negative backlash on marriages. Marriages in the diaspora reminds me of Mungoshi’s inongova njake-njake phrase, as couples’ bicker and squabble over trivia and in the end the children suffer when mummy and daddy go their separate ways.

BF: I read Diaspora Dreams at a time I’ve just finished Ignatius Mabasa’s Ziso reZongororo whose main character is struggling with memories of childhood from a disjointed family. In as much as Mabasa’s book is recounted from a child’s perspective, I see it conversing with Kundai’s tale as a father yearning to show off some love to his children during and after divorce. My question then is what do you think should be done to mitigate some unnecessary and unreasonable antagonism from divorcing adults which has a negative impact on children?Chatora: Beautiful question! Sit down and talk together as adults. Push those misplaced inflated egos aside and converse rationally, if not for you two anymore, then for the sake of the off spring in the marriage, children our future. Now, I am not naïve and do realise that sometimes things do not work out with the best of intentions in the world of relationships and people have to part ways. But even if that’s the case, then the children have a right to continue to have a positive and meaningful relationship with both parents, unlike the toxicity witnessed in Diaspora Dreams whereby Kay turns the children against their father. This is nigh despicable and should never be condoned.

BF: Now the story is filled with a beautiful nostalgic tinge when the narrator was hopeful and participating in initiatives meant to better the environment and living conditions. He is a man of many beautiful jackets: a contributor to local newspapers, a participant at ZIBF, a student activist. How did the writing process work as a reconnecting process with Zimbabwe and the past that now seemingly look beautiful to you as a writer?Chatora: I must say, writing has certainly worked well as a much-needed antidote to me, enabling me to reconnect with the multifaceted nostalgic Zimbabwe of yester-year particularly for one living so far away from home. In a way, writing has enabled me to live vicariously through my characters such as Diaspora Dreams protagonist Kundai. Perhaps it’s no coincidence therefore some of the harshest criticism on the book has been from those who claim they saw Kundai in me particularly those readers who knows me personally, (a chuckle…).

But yes, there’s that reconnection that writing about my beautiful homeland Zimbabwe affords me. Writing Diaspora Dreams for instance provided that panacea for me to bond with my native Zimbabwe heritage, kurukuvhute – where it all started. You will see for instance my searing passion jumping out from the passages as I recount and reference places, I like for instance growing up in the dusty streets of Dangamvura, Mutare, writing prodigiously to the local newspaper: The Manica Post, being a student activist at the University of Zimbabwe, my incarceration at Avondale police station, ZIBF forays, Mutare museum poetry reading sessions, all this of course is reflected through my central character Kundai. And no, I am not a misogynist as some readers have charged pointing accusatory fingers at the portrait of Kundai and his difficult relationships with women.

BF: Still on relationships, Kundai remarked “One survival trick I learnt with white people in England was to play the politics of survival; sometimes you had to act the fool and know when to say something or keep your mouth shut”. Shed more light on the sometimes-tumultuous space of race relations in the global north. Looking at paradoxical reactions from the whites in the book and black reaction to white supremacy do you have hope in better racial relations in Europe and the globe?Chatora: Race relations is considered divisive and touchy a subject by many thus I saw some deliberate smears by certain sections of some readers who possibly felt uncomfortable with Diaspora Dreams content and therefore sought to detract from the race relations subject matter it covers by peddling an alternative, facile narrative that the book is misogynistic and not helpful to the Feminist movement as if writers write to ingratiate themselves to particular or sectarian organisations!

Now, this may appear a winding response to your question but let me come to the crux of the matter in a minute. Post-Brexit Britain has increasingly become toxic and racist, with a binary dichotomous us versus them society created and sadly, foreigners, immigrants have become the object of racist vitriol, relentless scapegoating, needless bashing and attacks in Britain, all the while fanned by a predominantly right wing, xenophobic, gutter British press. Much as I would want to appear optimistic about race relations in Britain, I have to be honest, I can’t. Unfolding events in Britain today points to an increasingly polarised nation along the racial divide. And let’s get this straight Folks, this is not me, playing victim hood here.

Immigrants continue to experience racist micro-aggressions in England, particularly at the workplace and in their mundane private lives. A day after the Brexit referendum results, a white friend of mine, a fellow Teacher from Poland was brazenly told ‘go back home, you’re not wanted here,’ by her students. So, to come back to your question, summing up, I doubt things will become any better soon, and this is where narratives like Diaspora Dreams become relevant as they call out the institutionalised racism in Britain and its establishment. I doubt I need to even go far to elucidate some of my claims and observations here, the horrendous maligning and ‘lynching’ of Megan Markle by the rabid right wing British press is but a tip of the proverbial iceberg for what I’m saying here.

The recent Euro 21 aftermaths racist tirade directed against black England team players has been an ugly development in contemporary Britain, with all its cringeworthy negative headlines. The three England black players who missed the penalties have borne the brunt of a vicious racist vitriol at the hands of trolls and unashamed bigots. In America they rejected Trumpism and white supremacy in the last elections and I hope our day will come soon in England through democratic means to rid ourselves of this vermin that is Toryism and its servile acolytes.

This article was first published by Book Fantastics and it is published here with permission of Book Fantastics and the writer.

Author Bio:

Andrew Chatora writes prose and polemical articles and hails from Zimbabwe. His writing is steeped in migrant experiences, and he explores themes of belonging, identity politics, citizenship, nationhood, the black experience and the global politics of inequality inter-alia. Diaspora Dreams is his debut novella, published by Kharis Publishing in the US, an imprint of KHARIS MEDIA LLC. Andrew’s second novel Where the Heart Is, will be published on November 2021.

The post Diaspora Dreams Conceptualizations-Inspiration – Up Close with Andrew Chatora appeared first on Andrew Chatora .

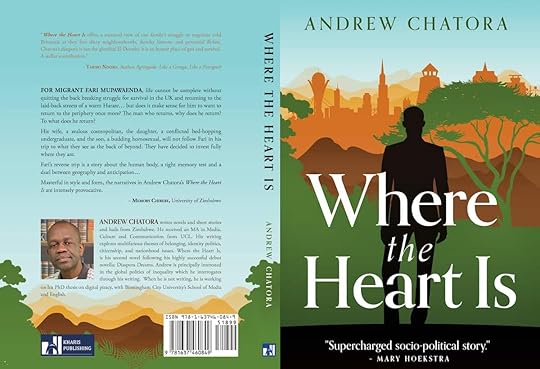

KwaChirere Previews “Where the Heart Is”, a Novel by Andrew Chatora

The fast-rising UK-based Zimbabwean writer, Andrew Chatora, has a second novel in the wings. It is set to be released soon on November 30, by his US Publishers: Kharis Publishing. Already, I can stick my neck out and declare that the forthcoming Where the Heart Is is, partly, ‘a novel of ideas.’

Just like what we witnessed with Chatora’s first novel, Diaspora Dreams, the latest novel will surely throw the readers into irreconcilable camps because the men and women in this story are not always sharing the same ideological pedestal. And the men, too, are not always agreeing with one another.

The story clearly expounds on and explores a particular debate; when the native leaves the periphery (Harare) for the centre (England) for a long time, due to economic reasons, does it make sense for him to want to return to the periphery once more?

You may also ask; is this homecoming or second coming, really possible? Are people really able to fully return to their source without sparking contradictions? The man who returns, why does he return at all? Or, to what does he return? You may go back to the source physically but is it viable economically, spiritually and socially?

But there are some in our midst who may say, wait a minute, even if going back to one’s country from the diaspora is difficult, could it be viewed as an entirely wrong thing to do, if one wants to? Which one is one’s country?

Well, Fari Mupawaenda tries to return to good old Harare from England and through him, the novel sparks a storm.

When it finally hits the market, Where the Heart Is, is going to be one of the very few novels by a Zimbabwean that fully imagines the joys and hazards of a physical return home from the diaspora. Olley Maruma tries it with his text Coming Home (2008), but I think his main character does not leave behind any stake in the UK. His is the return of a post pubertal man. Stanley Nyamfukudza tries it with Aftermaths (1983), but he is only working on the matter in one short story from a whole collection. Sekai Nzenza Shand tries it with Songs to an African Sunset (1997), but her work did not get much circulation.

The diaspora-based literature by Zimbabwean writers rarely thinks about this crucial reverse trip and its subsequent rich psychology. It is often assumed that it is easy to return because one was born here, anyway.

Yet, as dramatized here by Chatora, the reverse trip is also a story about the human body, a memory test and the struggle between geography and anticipation. During this reverse trip, the traveller is actually carrying heavier and multivarious cargo than during the first outward trip.

In Fari’s case, part of his crucial cargo has actually remained behind in the UK. His wife, a zealous cosmopolitan, the daughter, a conflicted bed hopping undergraduate and the son; a budding homosexual, will not follow Fari in his trip to what they see as the back of beyond. They have decided to invest fully where they are.

Fari is convinced that whatever he achieves in the diaspora should only make adequate sense only if one returns to the source. He constantly judges people and things around him from the point of view of a country that he has long left behind. And yet he has changed.

I enjoy the underlying suggestion that Fari is both right and wrong in trying to return. That is the strongest lesson that I took away from this novel. If you return you are damned. If you don’t return, you are damned too!

I also want to call Where the Heart Is, a ‘thinker’s novel’ because you can never read it and not re-examining issues like culture, distance, centre, periphery, family, love, sex, marriage etc etc.

The author also uses sexual intercourse as an extra language of unity and disunity, and this will set tongues wagging.

As in Pepetela’s Mayombe (1979), Charles Mungoshi’s Kunyarara Hakusi Kutaura? (1983), Ignatius Mabasa’s Mapenzi (1999) etc the characters in Chatora’s latest offering come out very clearly individualised. Each of them has a distinct signature.

The article was originally published on KwaChirere on November 8, 2021 and is published here with permission of the writer.

Where the Heart Is, is Andrew Chatora’s second novel after Diaspora Dreams which was published by Kharis Publishing in the US.

It’s now available to pre-order on Amazon.

In Harare, copies will be sold by Book Fantasticks Booksellers reachable on:

Brian: +263 77 921 0403

Kudzi + 263 715 072 288

Email:

fantasticbooks.21st@gmail.com

The post KwaChirere Previews “Where the Heart Is”, a Novel by Andrew Chatora appeared first on Andrew Chatora .

‘‘Home is Where One Is’’ – A Review of Andrew Chatora’s Where the Heart Is

Andrew Chatora’s new novel, Where the Heart Is, tackles a very important issue, namely the experiences of those in the diaspora. Invariably, there is an unmitigated longing for the familiar comforts of ‘home’. However, the identity and location of ‘home’ are fiendishly complex matters. For some, ‘home’ denotes their current physical location. For others, ‘home’ equates to the country of their birth and initial upbringing. These polarities find excellent expression in Chatora’s second book, and they chip away at the fabric of the protagonists’ judgment and relationships. In the end, ‘home’ is where one is. Fari Mupawaenda the narrative’s central character toys with a homecoming of sorts but stark economic and health exigencies compel him to leave ‘home.’ However, the matter does not rest there. Fari’s eventual homecoming takes a morbid and final turn – an event which was marked with little if any ceremony. Where the Heart is raises compelling questions relating to identity and place. These cardinal questions are not capable of a settled answer, but they received prominent attention in the book.

Where the Heart is raises themes of a different but important order of which human trafficking is quite prominent. Here, the distinction between villains and victims becomes quite nebulous. Deceit and physical need reign supreme until everything is unravelled. Because of the relevant characters’ ingrained sexual incontinence and lack of self-awareness, matters take an almost farcical twist.

A sublime read. Chatora offers a vibrant new voice in African Literature.

The diaspora challenges accepted local wisdom on the formation and prosecution of personal relationships. Convenience replaces the value of probity with the usual consequences. Chief among these is Fari’s ability to lurch from one poor choice to the next. These shifting sands plague filial relationships too. In a foreign world what is sexually appropriate for one’s children is mired in controversy. Fari’s relationship with his children is shaped by matters relating to sex and sexuality – a recipe for disaster.

Fari’s relationship with his children is shaped by matters relating to sex and sexuality – a recipe for disaster.

Another subtle but important theme in the book concerns the inability of some men to adapt to the new social realities. Fari and Maidei inhabit a universe in which mutual respect and affection is negotiated on crude patriarchal norms. Initially, Fari sees himself as the head of the house who should control his family and whose word is final. However, for women, the diaspora brings freedom, and this is brought out palpably through the portrait of the mercurial Madei, Fari’s estranged wife. A woman ceases to be one of her husband’s chattels. She has agency and can make choices relating to her future. At a lesser, level the fluidity of ‘being’ in the diaspora gives rise to frayed personal relationships in which monogamy is dispensable and various short-term liaisons reign supreme. Even basic and prudent financial decisions including financing the purchase of a house become intense but unnecessary battlegrounds. These disturbed bonds and conflicts percolate into filial relationships and generate mistrust and misgivings.

Chatora’s latest offering is to be congratulated for handling numerous big themes deftly and without judgment. The characters become strange partners in a journey of self-destruction and misplaced priorities. There is a raw honesty in the book and the sensitivity to detail is excellent. Where the Heart Is, is highly recommended. It will appeal to numerous audiences including observers of some of the less than salutary effects of migration on established social norms. It also provides an immediate perspective on how to identify the physical location.

Originally published in This Is Africa. All Rights Reserved.

The post ‘‘Home is Where One Is’’ – A Review of Andrew Chatora’s Where the Heart Is appeared first on Andrew Chatora .

March 11, 2021

Introducing Andrew Chatora

Born in Harare and raised in Mutare, Andrew Chatora is a Zimbabwean writer who currently resides in England. His debut novella, Diaspora Dreams was released in April 2021. With two other books up his sleeve, Andrew has much to say about the migrant experience.

Although journalism is his first love, he received an MA in Media, Culture, and Communication from UCL and has published on topical issues with This is Africa. Andrew keeps coming back to fiction as his mother was a master storyteller. Although he is completing a PhD thesis on Digital Piracy, with Birmingham City University’s School of Media and English, the BLM uprising sparked by the killing of George Floyd helped him find the voice to write Diaspora Dreams.

Diaspora Dreams was published in April 2021 by Kharis Publishing.

Diaspora Dreams Review (by Memory Chirere)

There are strong indications that the UK-based Zimbabwean writer, Andrew Chatora, is going to release his debut novel, Diaspora Dreams with Kharis Publishing in the US very soon.

On noting the subject matter, I was initially tempted to assume that this new author would take the usual route about a young Zimbabwean coming to the UK because of the crisis back home.

Ever since Dambudzo Marechera of The House of Hunger’s “I got my things and left…” of 1978 to the present, the central character of such novels, who is almost always a young fellow, flees home and country in search of an alternative existence. After that, he becomes double faced, constantly checking on the new ground while peeping at the political goings on back home. He then becomes a keen political eye.

However, Chatora takes a very courageous and startling detour with this new book. The main character, Mr. Kundai Mafirakureva, is following up on his teacher wife, Kay, in England. Her pregnancy is now very advanced and Kundai has come to be with the beautiful Kay in her time of need, something far away from Chikwava’s single-minded man in Harare North.

But Kundai walks late. He does not know that he has in fact come to ‘school.’ He does not know that he is coming to the UK to learn about what women can do, sometimes, to their unsuspecting men when the survival instincts rise above love ties. If you are used to the many novels that dwell on how men typically abuse women, then this book is something else.

From the moment Kundai from N133A Dangamvura- Mutare, manages to secure a visa at Heathrow, a whirlwind takes over. Husband and wife are on new turf. This is the UK. Their constant power struggles over which relatives should receive money from the UK and who should not, begin in earnest. Traditional African filial ties are on trial.

Kay constantly reminds Kundai that he is just a black man, anyway and that black men in the UK have no favorable recourse to the law. “Kundai, remember, you are just a black man in the UK.” On several occasions when they have a row, the British police are called to the house and they come with a clear assumption that; when a black man is in a quarrel with a woman, it must just be him who is on the wrong. They are ready to assume judge and jury. They often advise Kundai to either come to the station with them or go put up somewhere else for the night. The stereotypes run deep and Kundai is walking down a well laid script.

The climax of their fights with Kay comes when Kundai notices that Kay’s mother, vaFugude, has the temerity to use DHL to send love potions or concoctions to Kay from her sangomas, all the way from Zimbabwe! These mixtures are to be used on Kundai so that he becomes a compliant husband. An avid believer in seers, medicine men and dark mystical forces, vaFugude makes it her specialty to consult these darker, underworld forces on behalf of her daughter, Kay.

Everything becomes a power issue with Kay. From sex to normal conversation, she has to have the last word. Their divorce is tumultuous and tends to prove to Kundai that the British legal system is rather impatient with the protestations of men folk in these matters. Kundai has to go to court a record eleven times, to be allowed mere contact with his children. This involves meeting periodically with the children under observation, in a neutral empty hall. The children become tormented and disgusted. They have a distant look in their eyes.

In search of comfort, Kundai goes on to cohabit with a white workmate, Zettie, whom he calls ‘a stunning looker.’ Zettie is a young liberal-minded white girl from an affluent Buckinghamshire family. She appears to be the answer to Kundai’s questing spirit. She quickly learns to cook traditional Zimbabwean dishes and tries to speak Shona. She wants to be the ideal wife to an African man far away from Africa. But on their first visit to Zimbabwe, Zettie falls for and gets impregnated with Kundai’s cousin, Kian! They hit it off straightaway with Kian, as they both sit long drawn-out hours on the veranda at the Vumba homestead, downing lagers and continuously chain smoking weed, as if they have known each other for ages. Once more, things fall apart for Kundai.

Kundai quickly moves on. He does not want to be alone. He hooks up with a woman on an online dating website. She is a Zimbabwean called Jacinda. They quickly get married and Jacinda joins Kundai in the UK. In no time, she starts to treat Kundai to the bitterest and scariest lesson of his life. You read on with a numbed face!

Kundai loses it all and his subsequent charmed incantations and chants while in an English madhouse, are the most revealing part of this novel. As a result, Diaspora Dreams could be of interest to those who study the male psyche and manhood. The losing black male is still a dark area, rich with distances to be traveled and depths to be probed.

Original post: http://memorychirere.blogspot.com/2021/03/kwachirere-previews-diaspora-dreams.html (reblogged with the author’s permission)