Michael Elliott's Blog, page 12

July 23, 2022

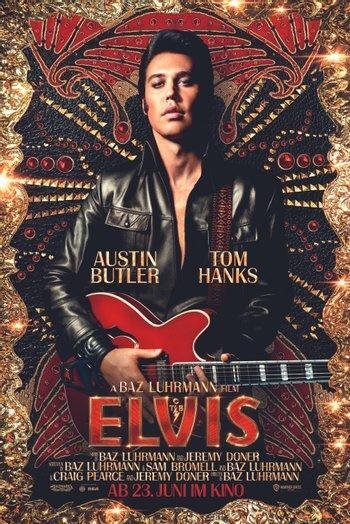

From the Ghetto to Graceland: Elvis Still Stirs Emotions

Baz Luhrmann brings his gaudy, flashy touch to the gaudy, flashy world of the King of Rock’n’Roll

Baz Luhrmann’s Elvis has so many moments that thrill and excite even as they frustrate and confound, it could get downright exhausting. Even a month after first seeing it, I’m still wrestling with my feelings about it.

Like any good southern white kid of a certain vintage, Elvis was my gateway to everything that came before or after. He was an angelic figure that had tragically fallen to Earth even while he was still alive. I witnessed in real-time the (in)famous final concert portrayed in the last act of this film and although I was very young when it aired, I remember feeling sad and disappointed that the badass in leather I’d sang along with during his legendary ‘68 comeback special, that had shook and shimmied throughout that famous scene in Jailhouse Rock, and that sang all those incredible, ghostly, incendiary Sun sides, looked like a bloated, sweaty mess. But still, that voice soared. It was no surprise even to my young mind when he was found dead just weeks afterward.

Still, my mama cried. And so did I.

So yeah, Elvis and I go way back.

I’ve Never Been a Fan of Biopics.I much prefer my music histories to be delivered via documentary or in book form. I’ve never wanted to see actors trying to portray my musical heroes. They never measure up to the real thing. I can’t think of one biopic (outside of Walk Hard) where I haven’t walked away thinking, “Why did they even bother?” That said, for some reason, I’ve always watched the Elvis ones. The first one I remember was with Kurt Russell playing the King in a TV movie that was released just a year or two after Elvis died. It was a big deal and I remember being very impressed with Russell’s portrayal. To me, after all Russell has accomplished since then, he’s still “that guy that first played Elvis.”

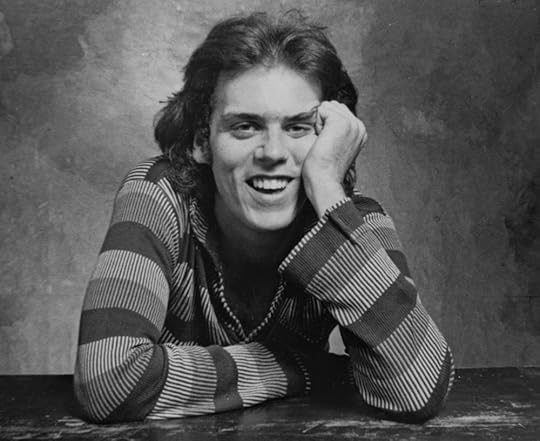

Kurt Russell as the King in 1979’s TV movie, ‘Elvis’

But in truth, Elvis’s story is so big, so unprecedented, his presence so large, it’s impossible to fully encapsulate his reach and influence. That doesn’t stop generation after generation of musicians, filmmakers, critics, and producers from trying however. In this respect, Luhrmann is as good a filmmaker as any to attempt to tackle the spectacle of the Elvis Presley phenomenon. He mostly succeeds, in his own way.

Much has been said elsewhere about the structure of the film; how it’s told from the POV of Andreas Cornelis van Kuijk, and how Tom Hanks plays the part. As for Austin Butler, it’s an insurmountable task to play Elvis without succumbing to parody or exaggerated affectations. Butler, however, plays the part as well as any I’ve ever seen, and better than most any that have ever attempted the King’s elusive combination of innocent, southern aw-shucks charm and dangerous yet natural sexual energy. So instead of trodding down the same path other reviewers have already traveled, I’ll simply fall back on that lazy, all-too-common current use of that most reviled of all modern journalistic tricks, the list.

The Good

Austin Butler as Elvis - See above, but to reiterate, an arresting presence and quite possibly an Oscar-worthy performance of one of the most enigmatic characters of the 20th century. See frame-by-frame comparisons of his performance and the real deal. Amazing attention to detail.

Set Design/Costumes - Speaking of attention to detail - especially from the 1960s through the ‘70s - jaw-droppingly accurate re-creations of his movie years and the Vegas era made me overlook the sometimes frustratingly glaring inaccuracies. It’s no doubt a beautiful film.

Yola as Sister Rosetta Tharpe - The amazing Yola’s big screen debut is electrifying as the groundbreaking founding mother of rock’n’roll. She proves she’s got the goods for a long, long career in music and, now, the movies, if she wants it.

The BadSam Phillips - Nothing against (the actor who portrays the larger-than-life legendary founder of Sun Records) personally, or even professionally, but saying this character wasn’t “fleshed-out” is a severe understatement. Sam Phillips was one of the most colorful and enigmatic characters in rock’n’roll history, but you’d never know it from his portrayal here. Here, he seems like a sweet, understanding puppy dog. In real life, he refused to ever acknowledge Tom Parker as “Colonel.” He also helped steer Elvis - and many others - into what he - and they - became.

Gladys - Yes, Elvis loved his mama. Yes, Elvis was a mama’s boy. Why, though, did Luhrmann portray their relationship in a near-Oedipal fashion? There are moments that are eye-rollingly awkward, uncomfortable, and downright cringe-worthy.

Jerry Lee Lewis - What’s that? You don’t remember seeing him in the movie? Yeah. Exactly.

The Unnecessary Modernism - We don’t need Elvis’s pelvic thrusts accented by heavy metal guitar punches, nor do we need a modernization of the music. The original music is still as powerful as ever, thank you. (That said, kudos to super-producer Dave Cobb for a fantastic soundtrack, as distracting as some parts are in the movie.)

The Meh

Hanks as The Colonel - His portrayal as the evilest manager in history has been dragged all over the internet. It’s really not that bad, but it’s not the Oscar-worthy performance he was probably shooting for.

Little Richard - Again, nothing personal against Alton Mason, who had to portray another larger-than-life character in the film, the inimitable “Little Richard” Penniman. Like Elvis, it’s almost impossible to embody such an enigmatic and groundbreaking artist, and in the big scene he gets, he comes across as downright tame compared to the real deal. Usually, biopics go overboard in their dramatizations. It’s a testament to Little Richard that they aren’t wild enough.

B.B. King - A fine, fine performance by ., who captures perfectly the calming demeanor of the blues legend. The problem is, again, the script. King was not that type of friend to Elvis, although they were acquaintances. It’s a little cringe-worthy in the way King and others are utilized in an “I have a lot of black friends” way that is completely unnecessary and almost offensively pandering.

Priscilla - Her complexity in real life, unfortunately, ends up in the film being utilized as a typical “spouse of the rock star” formula role. handles the performance well, I just wish she’d been given more depth. She - and Priscilla - damn well deserve it.

All in all, Elvis is a movie that does what it should: it entertains and provokes discussion. On that note, it has succeeded. Yes, it has its flaws, but overall, it is a major spectacle that will delight fans of Baz Luhrmann’s style, and it’ll keep Elvis fans - and his detractors - talking for quite a while. The best news, probably, is that a whole new generation is being introduced to an unequaled body of music from several architects of rock’n’roll. How can you argue with that?

In memory of Shonka Dukureh, who did a wonderful performance as Big Mama Thornton. She unfortunately passed away way too soon, at the age of 44, on July 21.

June 22, 2022

1992

A look back at a year of funky divas and ingenues, southern harmony, crunching rock’n’roll, moody atmospherics, and a whole lotta chronic.

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

Yes, 1992 was 30 damn years ago.

The big news: Young Elvis won out in the great postage stamp debate of ‘92 while Honeymoon In Vegas hit theaters and gave us a King-centric soundtrack that far surpassed the movie. Speaking of movies, the ‘92 box office also gave us A League Of Their Own, The Bodyguard, Wayne’s World, Basic Instinct, and A Few Good Men just to name, well, a few.

Bill Clinton was elected the 42nd President of the United States, John Gotti was sentenced to life. The Washington Redskins won Super Bowl XXVI. The Chicago Bulls, with Michael Jordan, took home the NBA Championship trophy for the 2nd consecutive year.

Despite the feeling of renewal in the air, the rock music world was beginning to sound downright angry and depressed. Yes, the bubblegum metal scene that had partied without consequence and covered us all in hairspray for the better part of the previous decade had gotten a bit out of hand. But the overcorrection by the incoming hard rock Debbie-Downers made listening to rock radio (as the Gin Blossoms put it) a New Miserable Experience. Everyone from Alice In Chains to Rage Against the Machine had started pissing and moaning their angst and aggressions all over the airwaves, forgetting what everyone from Chuck Berry to Joey Ramone had been preaching for years: that rock’n’roll, first and foremost, is supposed to be fun, at least most of the time.

On the bright side, there were some quality albums released by heritage artists - from Neil Young to Roger Waters, and some bonafide classics first saw the light of day that year: from R.E.M. and the Black Crowes to kd lang. Mainstream country had its moments of brilliance, but mostly it continued its steady decline into the saccharine world of Adult Contemporary/milquetoast/singer-songwriter cheese. (It was also the year of both “Achy Breaky Heart.” and “Boot Scootin’ Boogie.”) The big news, however, was hip-hop. From Arrested Development to the unmatched power of Dr. Dre, 1992 was the year when hip-hop began its ascent to the top of the heap, eventually replacing rock as the main soundtrack of America’s youth.

What follows is quite simply the 30 albums - one for each year passed - I listened to the most in 1992, in no particular order.

Emmylou Harris & The Nash Ramblers - At the Ryman

It’d be a few more years before Emmylou would gift us the astonishing mid-career masterpiece, Wrecking Ball. In the meantime, we were treated to a pleasant night out at the Ryman with an unrivaled group of pickers that included Sam Bush, Larry Atamanuik, Al Perkins, John Randall Stewart, and the late Roy Huskey, Jr. Kicking things off with a scene-setting “Guitar Town” is great fun, but the show-stopper is undeniably the coupling of Nanci Griffith’s “It’s A Hard Life Wherever You Go” with Dick Holler’s “Abraham, Martin, and John” a medley whose collective sentiment is frustratingly just as true now as it’s ever been.

Lou Reed - Magic and Loss

New York instantly became this lifelong Lou Reed fan’s favorite Lou Reed album upon its release, and it remains so to this day. So much so that any follow-up was guaranteed to disappoint. In that respect, Magic and Loss at first did just that. Yet, it was so magnificently captivating, I frustratingly had to succumb to its deep, dark brilliance. Dammit, Lou.

Eric Clapton - Music from the Motion Picture Soundtrack

As 1992 began, Clapton was on an upward trajectory again. His mid to late ‘80s output was awash in all the cold, digital trappings of the time, but Journeyman signaled that Slowhand had got his mojo workin’ again. By the time he was commissioned to compose the soundtrack to the dark, in-too-deep druggy cop thriller, Rush (featuring a menacing, scene-stealing Gregg Allman at the peak of his powers), EC was already a relative veteran of movie scores (Lethal Weapon, Homeboy). Yet the music here signifies his best soundtrack work before or since. It also included a jaw-dropping Buddy Guy version of “Don’t Know Which Way To Go” that was better than anything off Guy’s Grammy-winning Damn Right, I’ve Got The Blues of the same era.

Oh, and this is where “Tears In Heaven’ first appeared. Little did we know that song would soon kick off a career resurgence; a whole new era that longtime Clapton fans were not quite ready for, but would soon become the soundtrack to dentist’s offices all over the country.

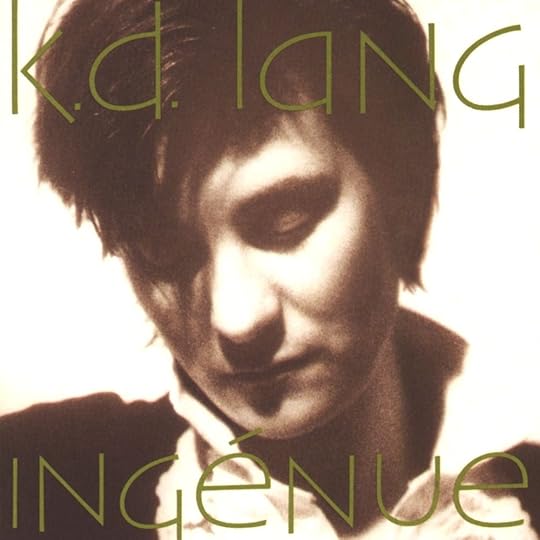

k.d. lang - Ingénue

Stylish and timeless, Ingenue was a welcome distraction from an increasingly polarized musical landscape. Here, lang effortlessly perfects her signature torch twang while making smooth pop so catchy that even Mick and Keith couldn’t ignore it. (“Has Anybody Seen My Baby” from 1997’s Bridges to Babylon was so inspired by “Constant Craving” that the Stones gave lang a co-writing credit).

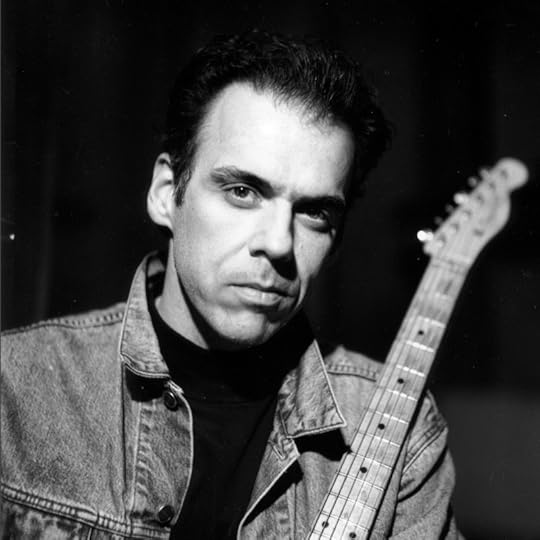

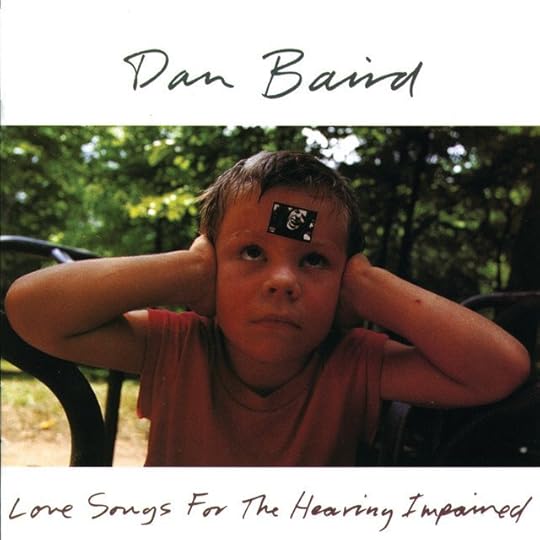

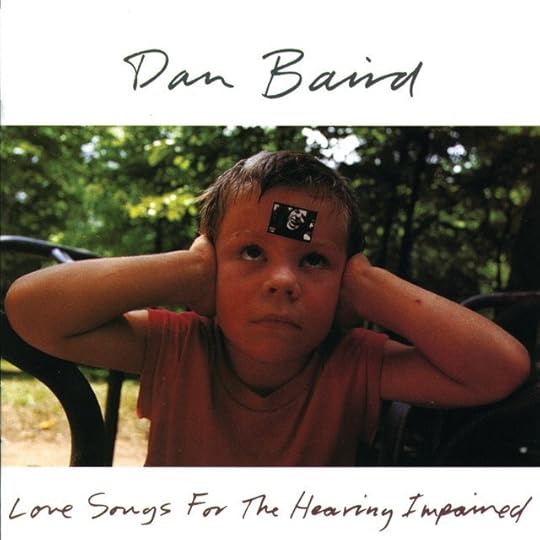

Dan Baird - Love Songs for the Hearing Impaired

The mastermind behind the Georgia Satellites ventured out on his own with Love Songs for the Hearing Impaired. Signed to Rick Rubin’s Def American and assisted by former one-time Sat and future producer to the stars, Brendan O’Brien, Dan Baird delivered a master class in rhunka-rhunka rock’n’roll for his classic first solo album. Chocked full of catchy choruses, ass-shaking rhythms, and witty lyrics courtesy of Baird and longtime co-conspirator Terry Anderson, who penned the big hit off the album, a “Hot For Teacher” for hillbillies (while somehow being smarter and dumber all at once), the eternally goofy sing-a-long, “I Love You, Period,” Love Songs sounds as vital and timeless now as it did upon its release.

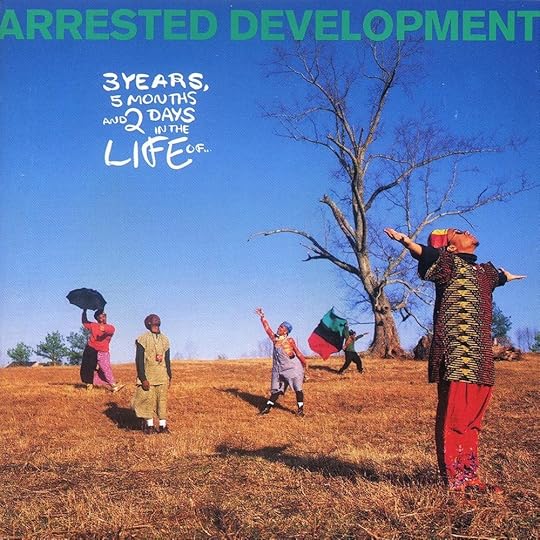

Arrested Development - 3 Years, 5 Months and 2 Days in the Life Of...

The same year Dr. Dre gave us The Chronic, Ice T unleashed Body Count, and Ice Cube released The Predator, Atlanta, before it was known as the Dirty South, gave us Arrested Development. Replacing the cliched tropes of violence and misogyny with messages of positivity, spirituality, and empowerment, Speech and the rest of this highly original ensemble offered a welcome gateway into the world of hip-hop for this uninitiated rock, country, blues, and gospel guy. Thanks to AD and brilliant tracks like “People Everyday” and “Tennessee”, I finally got to see what all the fuss was about.

Bruce Springsteen - Human Touch / Lucky Town

Probably the only evidence of The Boss being influenced, at least commercially, by Guns n’ Roses, and in the process yielding similar results, Springsteen released two albums on the same day in 1992. One was a bloated, unfocused ramble through half-baked ideas with the occasional brilliant track (Human Touch), the other a sparse, down-and-dirty, assault of roots-rock, finely-tuned with some powerful observations on aging, contentment, and the human condition - the perfect follow-up/antidote to the uncertainty that was Tunnel of Love (Lucky Town). The best tracks on both rate os Bruce’s best of the decade and can proudly stand not too many steps behind his classics. But both albums - especially Touch - are too weighed down by ambition to be front-to-back great. And we won’t mention that abominable cover art…

En Vogue - Funky Divas

Before Destiny’s Child, there was En Vogue.

Their second album catapulted these Funky Divas to critical and commercial success, and with good reason. Mixing hip-hop and New Jack Swing with funk, rock, and soul, they found the perfect storm of their R&B melting pot. The flawless harmonies of “My Lovin’” and the heavy-metal-thunder of “Free Your Mind”, in particular, guaranteed their place in history as divas of the highest, funkiest order.

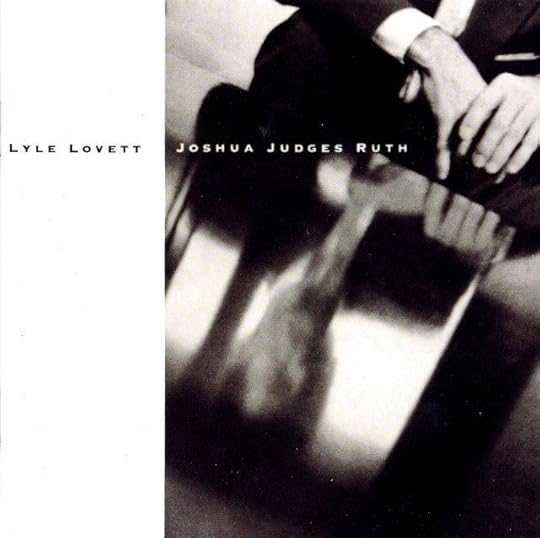

Lyle Lovett - Joshua Judges Ruth

A conflicted, sprawling masterwork, Lyle Lovett’s Joshua Judges Ruth is where the Texas singer-songwriter fully flexed his songwriting and arranging muscles. From the sparse, dark studies of heartbreak and loneliness (“All My Love Is Gone”, “North Dakota”) to rocked-up blues - or blues’ed-up rock (“You’ve Been So Good Up To Now”), to thorough and bizarre ruminations of the goings-on at religious gatherings (“Since the Last Time”, “Church”), JJR is Lovett’s finest moment in a career that has yet to see a moment that wasn’t.

Tom Waits - Bone Machine

Ugly, visceral, unhinged, brilliant. Waits continued his ascent/descent into the madcap world of post-music-madness while enlisting David Hidalgo, Les Claypool, and Keith Richards as accomplices. From crazed street-corner preacher musings to punk rock Peter Pan syndrome, Bone Machine rattled the senses, upset the nervous system, and picked up a Grammy (for Best Alternative Music Album) for its efforts.

Sass Jordan - Racine

Raw, Stonesy, Faces-y(?), Racine was Sass Jordan’s moment in the sun. UK-born, Canadian-bred, LA-bruised, Jordan’s second album boasted the better-than-all-the-hair-bands-put-together ballad, “You Don’t Have To Remind Me” and the balls-out opening track as highlights. Also that year, she showed up on the gargantuan soundtrack to The Bodyguard (singing with Joe Cocker, no less). She’d later occupy a judge’s slot on Canadian Idol, and was briefly in the running to replace the great Kelly Holland in Cry of Love. (All’s well, though. In 2006, Cry of Love’s Audley Freed - now a veteran journeyman for the likes of the Chicks, the Black Crowes, and Sheryl Crow -played on Jordan’s fine Nashville-made, Get What You Give.) On Racine’s 25th anniversary, she made the risky decision to re-record the album. The result was no embarrassment, as the songs benefited from the perspective - and performance - of someone older and wiser. And in that respect, Jordan is very much still alive and well; Bitches Blues was just released in June of this year.

Charlie Rich - Pictures and Paintings

Writer Peter Guralnick is to be credited for this one. He titled his classic book of profiles on roots artists, Feel Like Going Home, after a 1973 recording by Charlie Rich. If you only know Rich from his Billy Sherrill-produced mega-hits, “Behind Closed Doors” and “The Most Beautiful Girl In The World,” then stop reading this and go listen to his earlier, primal stuff, from “Mohair Sam” to “Who Will the Next Fool Be.” Or better yet, just cue up this, his final album. Cut a couple of years before Rick Rubin brought Johnny Cash “back to his roots” and got all the attention and accolades, this out-of-left-field jaw-dropper built on the powerful interview and profile Guralnick did with Rich years before. Every track is worth hearing, but the pièce de résistance is the final cut; where he revisits “Feel Like Going Home” and gives it the soul and yearning the original deserved. Rich was called home just three years after this album’s release, dying in a Florida hotel room from a blood clot on his lung. Although it wasn’t planned, Pictures and Paintings was as find a career cap as anyone could ask for.

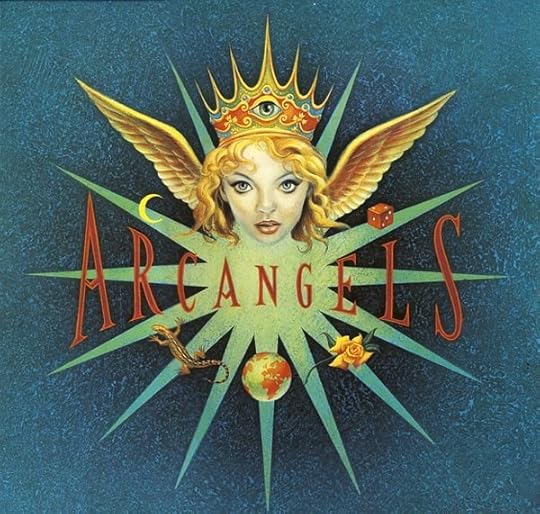

Arc Angels - Arc Angels

Chris Layton and Tommy Shannon, better known as Double Trouble, started jamming with Texas guitar firebrands Doyle Bramhall II and Charlie Sexton to kill some time at the Austin Rehearsal Center (ARC). Next came the label signing (to Geffen) and the self-titled debut, which is one helluva slab of Texas rock’n’roll, complete with two strong homages to their former friend and bandmate, Stevie Ray Vaughan (“Sent By Angels”, “Look What Tomorrow Brings”), along with the fierce crunch of “Too Many Ways To Fall”, “Paradise Cafe”, and “Living In A Dream.” Thankfully, they’re back to playing a handful of shows around their native Austin and surrounding area. Frustratingly, this is still their only studio album.

Robert Cray - I Was Warned

More of the same from Robert Cray is still better than some other artists’ best stuff. That’s why I Was Warned deserves a spot here. That, and “Just A Loser” is just a damn good song.

Faith No More - Angel Dust

Sneaking their way onto MTV’s Headbanger’s Ball past all the soundalikes and lookalikes of the era, Faith No More’s “Epic” pointed the way to the decade to come, for better and worse. Angel Dust, however, was where everything clicked. The relentless pop of the snare, the thump and slap of the bass, and inventive arrangements sounded completely fresh and still thrills 30 years on.

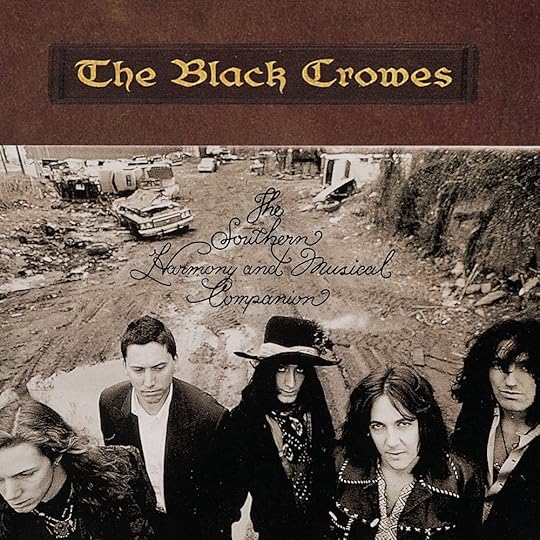

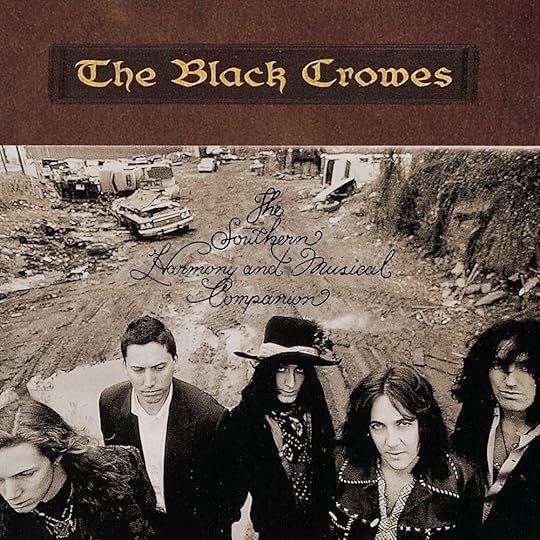

The Black Crowes - The Southern Harmony and Musical Companion

I could write a whole essay on my feelings for this beast. (Actually, I have, and it’s been on my hard drive for about six years). But it’s too much to put here, so I’ll just quote myself from my piece for Albumism: “No sophomore slump in sight. In fact, the Black Crowes' second album remains their masterpiece. Adding Marc Ford and Eddie Harsch, along with the superb backing vocals of Barbara Mitchell and Taj Harmon, this is where the Crowes joined the ranks of those they idolized.”

Lindsey Buckingham - Out of the Cradle

This is how the best pop should sound: inventive, quirky, effortless, a little off-kilter, but catchy as hell.

Mary Chapin Carpenter - Come On Come On

The smirk says it all.

Mary Chapin Carpenter elevated country music to damn-near high art without even trying and when hardly no one else could be bothered. She first appeared during the “New Traditionalist” movement of the mid to late 1980s, having moderate success with some highly-acclaimed material, but Come On Come On was a well-deserved critical and commercial hit, right at the height of Garth-mania. Funneling her folk leanings slyly through a radio-friendly-enough country facade, she got a Lucinda Williams song into the Top 5 of the country charts, co-wrote two fantastic songs with the great Don Schlitz (the subtle feminist jab “He Thinks He’ll Keep Her” and the remarkable “I Take My Chances”), and not-so-subtly hinted at a possible ménage à trois with Dwight Yoakam and Lyle Lovett. Hot dog!

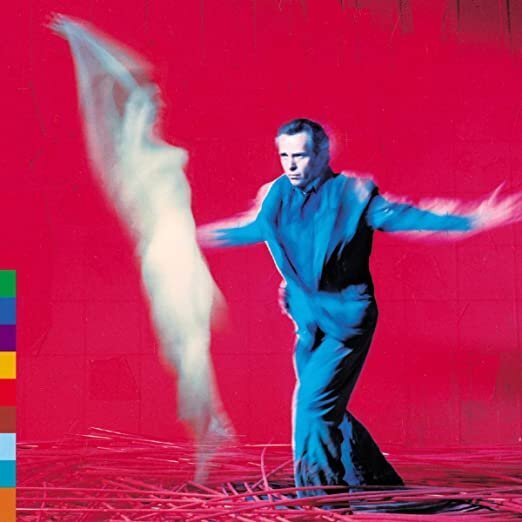

Peter Gabriel - Us

Every Peter Gabriel album is an event, and Us was no exception. Yes, it built upon what made So such a defining moment in an already incomparable career, but in doing so, it revealed even more layers of art, soul, and soul-searching - while adding much welcome world music textures - that’s always informed Gabriel’s best work.

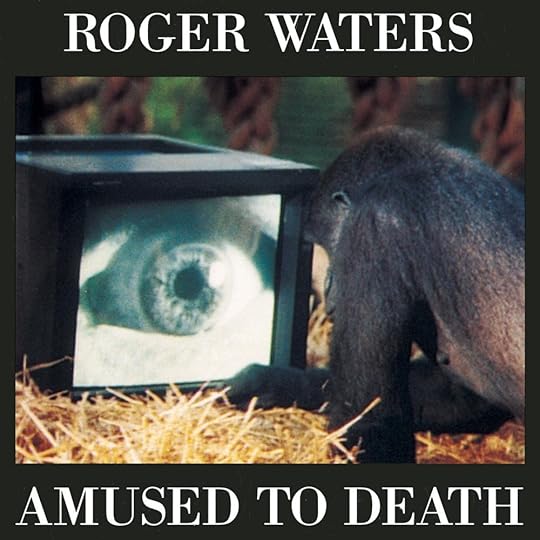

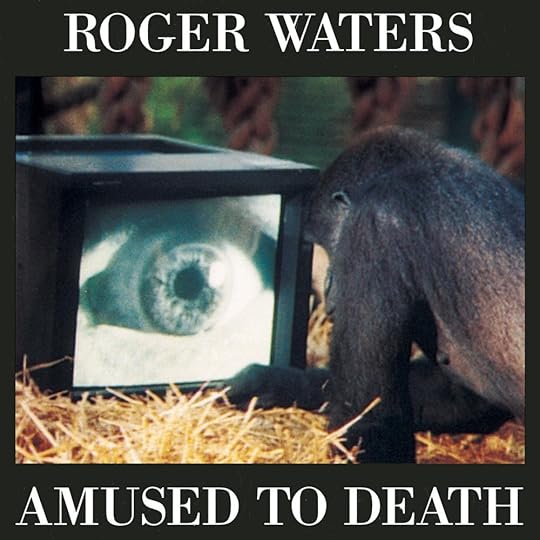

Roger Waters - Amused to Death

“What God wants, God gets. God, help us all.”

Following up the mess that was Radio KAOS and the unsettling beauty that was The Pros and Cons of Hitchhiking, Roger Waters went full Floyd and unleashed an prescient aural attack on complacency, fake news, apathethic nihilism, and media addiction long before social media, the internet, and cell phones took over the world. If that wasn’t enough, he brought along Jeff Beck as his wingman. Waters’ best moment since The Wall and easily one of the best albums of the ‘90s.

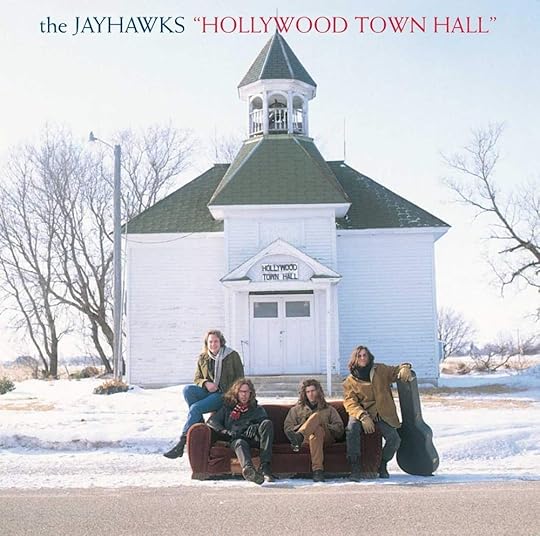

The Jayhawks - Hollywood Town Hall

Whether you want to call them alt.country, Americana, y’allternative, or just rock’n’roll, the Jayhawks have been giving us catchy, melodic, groovy brilliance for decades now, and it all started with this masterwork, led by the darkly joyous “Waiting for the Sun.”

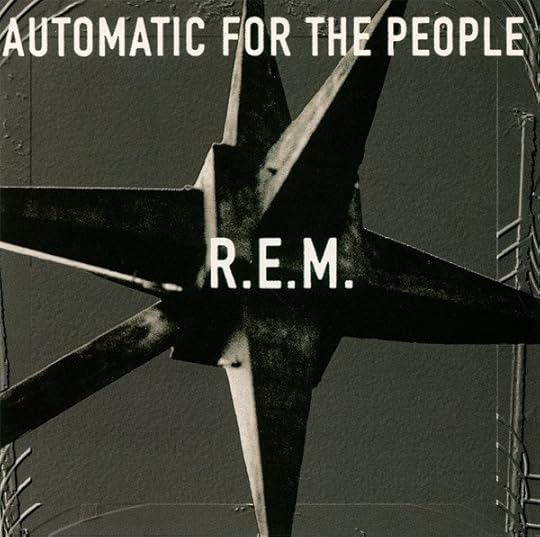

R.E.M. - Automatic for the People

Out Of Time pointed toward the direction Berry, Buck, Mills, and Stipe would take on its follow-up, Automatic For The People. The grays and black-and-white of the cover art reflected the music contained herein. There were no shiny happy people here; instead we were reminded that “Everybody Hurts” and that both Andy Kaufman and David Essex occupy equal space in Michael Stipe’s mind.

Tori Amos - Little Earthquakes

NC native Tori Amos displayed more angst and attitude with 88 keys than the whole of Seattle with their arsenal of amps and cheap guitars. A child prodigy, yes, but when sister started doing it for herself is when the true artist was revealed, and we’ve been reaping the rewards ever since.

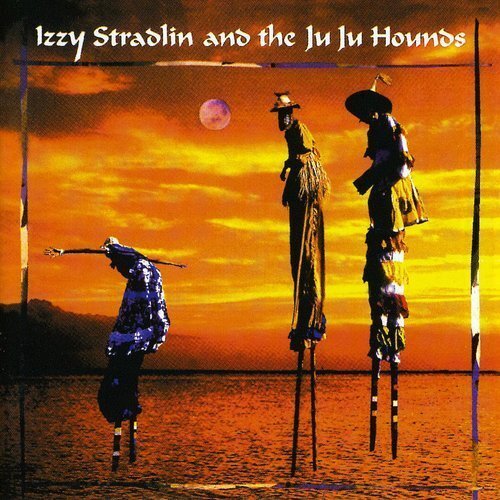

Izzy Stradlin’ and the JuJu Hounds - Izzy Stradlin’ and the JuJu Hounds

After the bloated Use Your Illusions debacle, it’s as if Izzy Stradlin’ woke up one day and decided he wanted to actually play rock’n’roll again. Gn’R just wasn’t it anymore, man. So he grabbed a former Georgia Satellite (Rick Richards) and threw together the JuJu Hounds, reacquainting himself with what excited him about this gig to begin with.

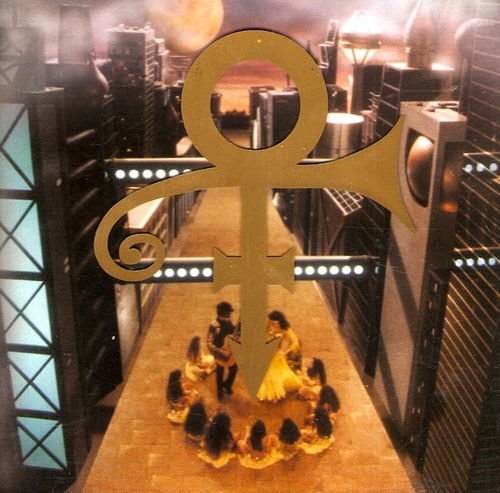

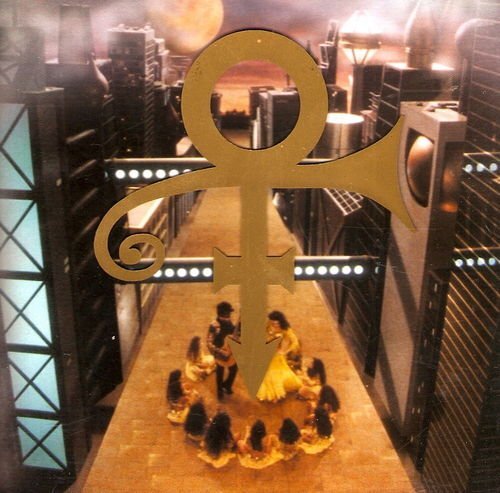

Prince - Love Symbol Album

His name is Prince and he is funky.

The Artist Formerly and Futurely Known As Prince’s best album since Sign o’ the Times was an epic journey with all the twists and turns one expects from the Great One, but turned up to eleven. From the soulful pop of “7” to the whacked-out James Brown/Frank Zappa-frantic-funk of “Sexy M.F.”, this was the best house party of the year.

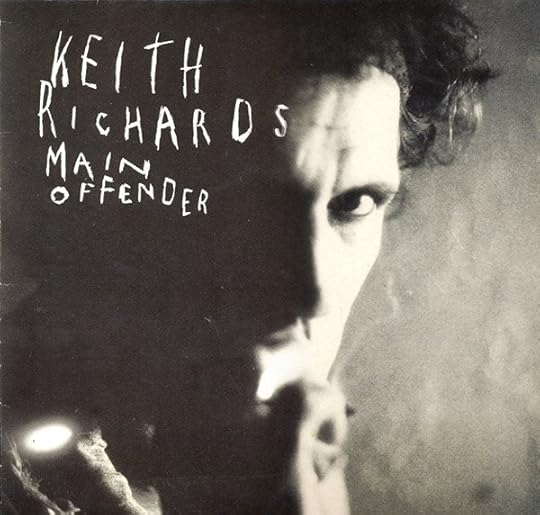

Keith Richards - Main Offender

Since it was released the same week in mid-October as Madonna’s multimedia Erotica project, Keith Richards’s second solo outing, Main Offender, was advertised on the inside back cover of that week’s issue of Billboard. On the back cover was a bright, captivating, wordless photo of Madonna, exuding her usual confidence. Flip open the back cover, however, there was a stark, black and white photo of Keith, partly in the shadows, with only the words, “Not Madonna. God.”

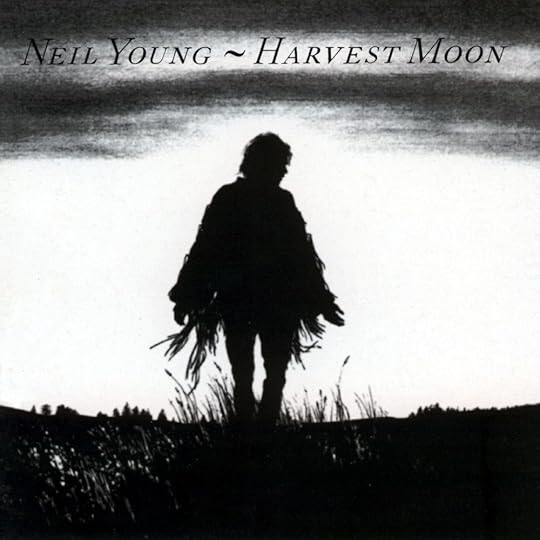

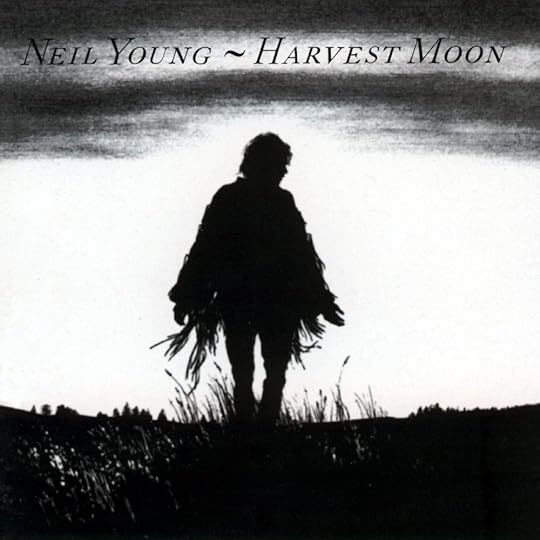

Neil Young - Harvest Moon

Young followed up the feeback frenzy of the monumental Ragged Glory with the divine beauty of Harvest Moon. Sure, it was a belated sequel to his mainstream masterpiece, Harvest, but any possible cynicism faded away as the first verse of “Unknown Legend” unfolds. From there, it only gets more lived-in, more comfortable, more perfect. This was peak mellow Neil, setting up a decade of living up to his legendary status as the godfather of both country-rock and grunge. That’s one helluva hat trick.

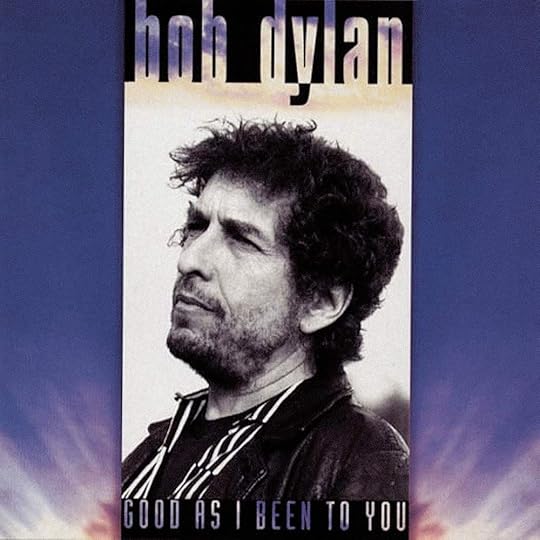

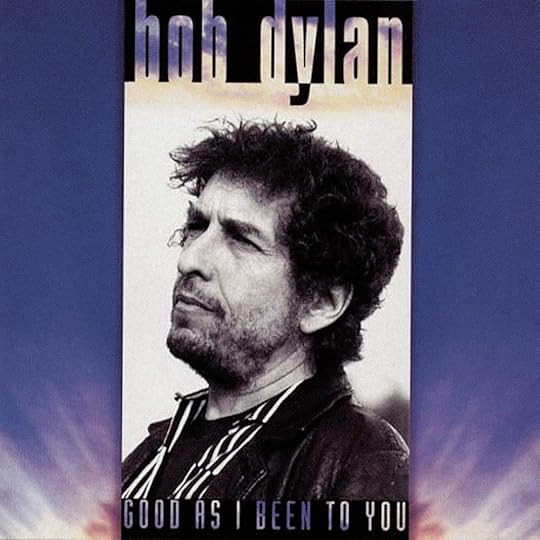

Bob Dylan - Good As I Been to You

Under the Red Sky did what so many Bob Dylan albums have done over the years after following up critically-acclaimed comebacks, it disappointed his fans and critics alike. The brilliant Oh Mercy had everyone excited again, especially after a decade of WTF moment after WTF moment. Red Sky just didn’t keep that momentum going (although it’s a fine album from this writer’s viewpoint). So to many, Good As I Been To You was Dylan heading back to the drawing board, to refuel and reassess. It was the first of two all acoustic, all cover albums of blues, folk, and pre-rock warhorses, both obscure and otherwise. And he sounded more engaged than he had since Oh Mercy. Even “Froggy Went A-Courtin’” works. If you want any more, you can sing it yourself.

Eric Clapton - Unplugged

When Eric Clapton sat for an “MTV Unplugged” taping, little did we know that it would kickstart an entirely new phase of the guitar legend’s career. Yet this little session begat a phenomenon; artists from all genres and all ages and stages had been cashing, um, joining in on the unplugged craze, with varying degrees of success, but Clapton’s turn made the big guns take notice. Yes, “Layla” was the surprise and “Tears In Heaven” was the hit, but the devastating “Circus Left Town” (finally released in a much less impactful, slicked-up studio version on Pilgrim a few years later) and a stripped-down “Old Love” are the moments that proved ol’ Slowhand was still worthy of the hype.

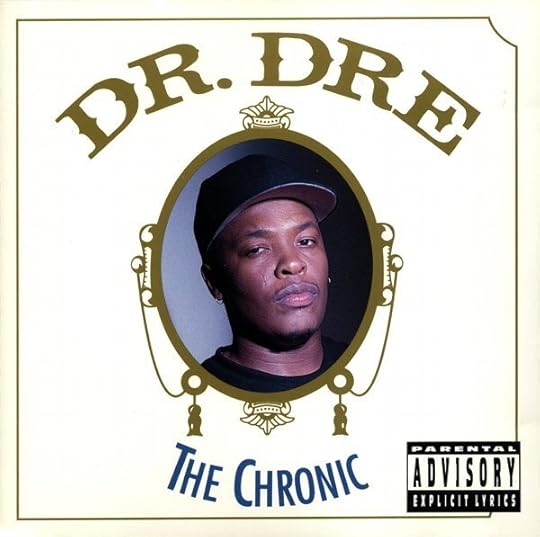

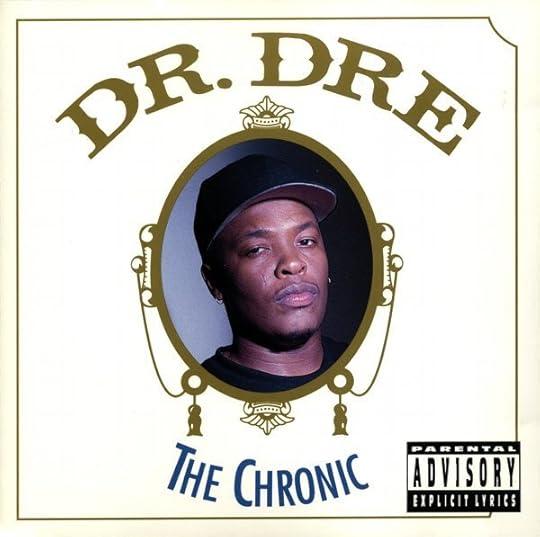

Dr. Dre - The Chronic

Dr Dre gave hip-hop its smooth and funky flow. Crafting soul, old-school funk and cool jazz into the mix, while layering over it all lyrics that revealed truly terrifying themes in a such nonchalant way. making the message even more powerful. By introducing us to Snoop Doggy Dogg, he gave us comic relief the album needed while introducing the most laid-back voice of the ‘90s. The Chronic is a milestone in American music, as deserving to be in the conversation as Highway 61 Revisited, What’s Going On, Pet Sounds, Rumours, and Songs In The Key Of Life. Its influence is still being felt thirty years on. Now let’s chill ‘til the next episode…

Honorable Mentions:

Wynonna - Wynonna

Ronnie Wood - Slide On This

Jude Cole - Start the Car

Melissa Etheridge - Never Enough

Los Lobos - Kiko

May 29, 2022

35 Years of ‘Bring the Family’

Looking back at what became a landmark album for both John Hiatt’s career and an entire music genre that was yet to be named.

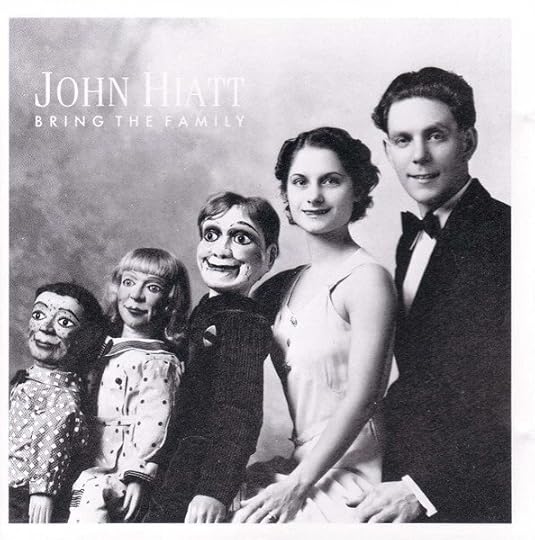

Original UK cover for the Demon Records release of ‘Bring the Family’. Photograph courtesy of the Great American Family Archive.

“I had just gone through a hell of my own making and came out the other side which had the effect of rendering all these other seeming monsters to be kind of toothless. They weren’t nearly as scary as any I’d created on my own.” - John Hiatt interviewed by Graham Reid, 1991.

By the mid-1980s, John Hiatt was considering giving up recording altogether and just living off royalties. After all, his songs were still being sought after and recorded. Maybe he could pick up some live gigs here and there. Maybe he could just join another band as he had done in the past with both Ry Cooder and Nick Lowe. Either way, Geffen had cut him loose, and to him, that was strike three. He was starting to think the record industry was trying to tell him something; they didn’t want him to make any more records.

One could hardly blame him for that outlook. By what was now well over a decade into a recording career, three major labels had dropped him. Geffen was the first label where he made more than two albums, yet they’d cut him loose, too. Although his songs were being noticed and, most importantly, recorded by more and more artists, and critics and fellow musicians were constantly lavishing praise, that big hit song, brought forth from his lips instead of just his pen, had so far eluded him. Still, he had two things going for him that he hadn’t had for quite some time: sobriety and a new love, and both were inspiring him to write about all these new experiences and emotions he was in the process of discovering.

“When you have a stable environment going for you, it gives you the courage to look at yourself and put what you see into your songs,” Hiatt explained in No Depression. “That takes balls, creating art informed by your life. A lot of people don’t want to know who they are. When they look in the mirror, they look past themselves. But what are the tough times good for if not to learn something, if only that you don’t know shit?”

That quote sums up John’s perspective during his newfound sobriety, which came before the suicide of Isabella, his second wife. At the time, he was living alone in an apartment over a garage, as he and Isabella had separated. In that little apartment is where he would begin work on the songs that would become Bring the Family.

Bring the Family not only stood out from other rock and pop albums from the 1980s due to its more organic sound, but also because of its subject matter. It was an album made by adults for adults. Released in the same year Motley Crue and Guns n’ Roses were celebrating the hedonistic lifestyle on the Sunset Strip with Girls, Girls, Girls and Appetite for Destruction respectively, Bring the Family represented adulthood, parenthood, sobriety, monogamy, domesticity, and responsibility - traditionally very un-rock and roll themes, and in fact, subject matter rock and roll rebelled against from its inception. In that respect, Bring the Family rebelled against the rebellion. Becoming a sort of 1980s version of Music from Big Pink, it shunned what was popular in favor of authentic sonics and mature values.

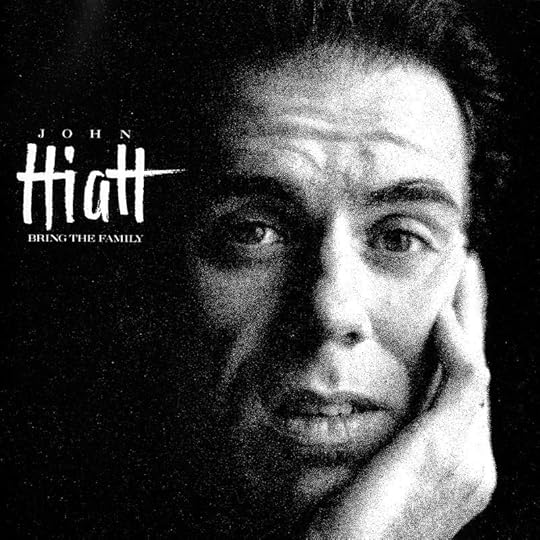

The US version, released on A&M on May 29, 1987. Unfortunately, A&M decided to forego surreality and the bizarre for the good ol’ tried-and-true artist headshot cover. “I lobbied for it,” Hiatt says. “But they wanted a picture of me.”

Memphis in the MeantimeOn the opening, “Memphis in the Meantime”, Hiatt plays the role, no doubt autobiographically, of the frustrated singer-songwriter who isn’t exactly setting Music Row on fire with his songs. Maybe he imagined himself back at Tree, filling up reels and reels of tape with songs for every occasion and/or artist's style, only to be turned down time and time again. Maybe that frustrated singer-songwriter was more than ready to drive three hours west to Memphis for some charcoal ribs at Charlie Vergos’s Rendezvous, in the alley, downstairs behind 52 South Second Street. Maybe he imagined himself tuning into WDIA or WHBQ on the way in, listening to Rufus Thomas or Dewey Phillips spinning those hot r&b and blues tunes. Maybe after hitting town, he’d head to Beale Street and catch a live band. Not one with a crying pedal steel, either, but one with those hot Memphis Horns and a Fender Telecaster played through a Fender Vibrolux Reverb amplifier, turned up to ten, of course.

Lyrically, the genius of “Memphis” also rests with the fact that the narrator isn’t sharing his experience or his intentions directly with the listener, instead, we’re listening in on a conversation he’s having with his partner/lover/spouse. She may be a performer herself (“You say you’re gonna get your act together, gonna take it out on the road”) but it’s obvious that, for now, they’re relying on his songwriting to get by (“Until hell freezes over, maybe you can wait that long / but I don’t think Ronnie Milsap’s gonna ever record this song). It’s not hard to picture a disheveled, frustrated wordsmith steeped in blues and r&b but eking out a living in Nashville trying to convince a fledgling country music-loving starlet to get good and greasy in a juke joint and a rib shack three hours away, where the soul of man never dies, as Sam Phillips would say.

Alone in the Dark“Alone In the Dark” is a harrowing piece of music. The narrator describes a “still life study of a drunken ass” howling at the moon, alone in the dark, but not wanting to face the day; instead, he’s hoping the sun doesn’t rise too soon because he’ll then have to possibly confront his demons, or maybe just his friends and family: those concerned for his well-being. He doesn’t want to hear it. Right now, he’s having a dark night of the soul, an evening of “extreme self-pity.” It’s a process. Leave him alone.

It cuts even deeper, though. This is the singer’s last stand. If we are to take these songs as autobiographical - and for Bring the Family, let’s face it, we must - this is Hiatt’s moment of clarity. He cries, “I’m on my knees at last!” It’s an epiphany, the moment of redemption when all past sins are brought to bear. The boy who flunked religion in Catholic school is ready to confess. Only when he’s alone in the dark can he finally see the light.

The song features some of Ry Cooder’s most ferocious slide playing on record, cutting through the steady, ominous groove laid down by Keltner and Lowe. With Hiatt’s bluesy howl wailing over his understated acoustic strumming, the song succeeds in its effortless goal of being equally frightening and dripping with sexual tension. (Its sexiness didn’t go unnoticed by James Cameron, director of the 1994 action-comedy, True Lies, who, at the suggestion of star Jamie Lee Curtis, used the song to great effect as Curtis danced erotically for her movie-husband Arnold Schwarzenegger, leaving him - and most moviegoers - speechless.)

Thank You GirlYes, there were moments of deep, deep lows on Bring the Family, but there was also plenty to celebrate, including finding his new love, Nancy, who’d help him out of the dark and into a lifelong journey of love and sobriety that continues to this day. With Cooder’s playful slide and Keltner’s driving beat, the music is as celebratory as the lyrics which boast, “If all men are equal, this must be against the law. ‘Cause I can’t help but feeling I’m one up on my brother when night falls.”

Lipstick Sunset“We’d been out on this long, epic tour,” Sonny Landreth recalls. “We weren’t getting sleep. We’d just gone out night after night. Just before we walk out on stage, John goes, ‘Oh, by the way, I understand Mr. Cooder and Keltner have requested tickets for the night.’ And I said, ‘Really? You might have told me that sooner, you know! But maybe he did me a favor so I couldn’t think about it too much. “I was okay until we got to ‘Lipstick Sunset.’ So we’re getting into the song, and I think, OK, Ry’s out there; just don’t think about it. Do your thing. And then I realized I was playing a Fender Strat that used to be Ry’s guitar that he gave to John. So here I am, playing ‘Lipstick Sunset’ and Ry’s iconic solo, just one of the greatest things you’ve ever heard in your life, on stage. He’s in the audience. We haven’t had enough sleep; we’re just burned out. And that’s the only time it ever kind of got to me. I don’t know what kind of job I did. At any rate, it was kind of a moment; then after that, I was fine.”

“I got lucky that time,” Ry Cooder admits when speaking about that famous solo. “I didn’t overplay. Those days, if I got excited, I’d play too hard and too much, and I had to get cured of that. But on that one my nervous system was in good form, and I didn’t overdo it.”

Thing Called Love“Bonnie found the song,” Don Was explains. “We both knew Bring the Family, but Bonnie’s the one that wanted to do (‘Thing Called Love’). And we had a hell of a time cutting it, too. It was the hardest song to record, and that was because of Jim Keltner. It’s this crazy juxtaposition. He’s got like two different feels going at once. It’s a shuffle against straight time, and without that, you can’t really do justice to the song. So we struggled with that for a long time, trying to figure out what was going on there, what was the thing that was making it dance.”

Keltner humbly credits Ry Cooder’s guitar work, however, as being the secret ingredient to that particular song’s success. “That’s Ry, that’s totally Ry,” Keltner confesses. “That’s Cooder at his best, his finest.”

Another change was to transpose the electric riff Cooder played over Keltner’s groove to acoustic guitar, which allowed Raitt more freedom to add her signature slide fills throughout the song, making it more radio-friendly than the original, which ultimately led to its success; success for both the artist and the writer. “The thing that really characterizes John's writing to me,” Was explains, “is that above all else, he’s an emotional writer that approaches it with talent, humor, and cleverness but never just for the sake of showing you how smart he is or showing you how clever he is. He does it without ego and always in service to the emotional content. I think ‘Thing Called Love’ is that kind of song. It goes very deep. I mean, ‘I ain’t no porcupine, take off your kid gloves,’ I’ve never heard anyone say that before. It’s so right.”

Stood UpHere, John addresses his alcoholism in, well, quite sobering terms. It resonated with me at first due to its clever wordplay, but later, as I fought my own battle with alcohol, it became a validation of sorts.

After the first verse sets up the plot, with Hiatt recalling his first steps and his “schooling years,” we get to the second verse, where we hear the regret in his voice over the way he left the woman with the “flaming red hair” (most likely an allusion to his first wife, Barbara). “I didn’t know how to be a husband or what marriage was all about, or even what being an adult was,” John recalls of that time. “Not just because of my age, but by being so emotionally stunted by drugs and alcohol.”

It’s the third verse that brings it home, though. The regret of the previous verse is replaced by pride and resiliency revealed by his recent sobriety. He finds himself still playing music in those bars and clubs, but not partaking while relishing the fact that he’s not giving in to temptation ever again.

Tip Of My Tongue“There was one song that we did that, later on, I couldn’t listen to,” drummer Jim Keltner recalls. “I just couldn’t get through it. That was ‘Tip of My Tongue.’ I never listen to it. I remember listening [to the album] in the car, and when that song came on, I remembered the story that Ry had told me about [John’s former] wife. And the story is about that. And I was just crying uncontrollably while I was driving.”

Your Dad Did“He had an obesity problem and he gambled,” Hiatt recalls of his father. “Those were his two addictions: food and gambling. But this enormous man was so charming, funny, and wonderful. I mean, people at these home shows would just fall in love with him. He was a great storyteller, just a wonderful guy.” And he was great at closing the deal. “He was responsible for a lot of those harvest gold, avocado green, and burnt orange kitchens around the Midwest back in the early ’60s.”

“Your Dad Did” is Bring the Family’s best example of Hiatt’s sardonic wit: the suburban all-American dream with an underpinning of darkness just to keep you on your toes. “You love your wife and kids,” Hiatt sings with almost a sneer, “just like your dad did.”

LegacyHe’s not a household name like many of the artists that have covered his songs over the years (Bob Dylan, BB King, Eric Clapton, Rosanne Cash, Iggy Pop, Willie Nelson, Bob Seger, Emmylou Harris, The Everly Brothers, Paula Abdul, Buddy Guy, and so on and so forth), but John Hiatt is one of America’s greatest songwriters, and Bring the Family is his greatest album. In the years since its release, at least one of its songs has become a modern-day standard and covered by dozens of artists (“Have a Little Faith in Me”); one revitalized the career of blues-pop legend Bonnie Raitt (“Thing Called Love”) and was included on her Grammy-winning album, Nick of Time; and even a throwaway line on the album-closing “Learning How to Love You” inspired the title of an album that has sold over 21 million copies (Hootie & the Blowfish’s Cracked Rear View). In 1989, Rolling Stone awarded Bring the Family spot number 53 on their list of the top 100 albums of the ‘80s.

Have A LIttle FaithUp in that above-garage apartment with only a little piano, for arguably the most famous song on Bring the Family, Hiatt reached back to those nights in his room listening to WLAC and those soul-stirring Gospel songs the DJ known as “The Hossman” would play. He started repeating a simple piano figure, over and over again until the words came:

When the road gets dark

“I'm not sure if I was singing it to myself...”

And you can no longer see

“Or if I was singing it to everybody in my life that I was trying to suit up and show up for but had no idea how to do that...”

Just let my love throw a spark

“And just the idea of having some faith in general, I think, which is what I needed at the time.”

And have a little faith in me

Listening to Bring the Family, one can clearly hear in the ballads John Hiatt searching for redemption as he works through his regrets, just as the up-tempo numbers celebrate his new life and marriage with the excitement of possibility.

It is in this sense that Bring the Family has its most profound impact on the listener. It can be enjoyed on the surface as an album that sways and swaggers with inventive, funky rhythms and inescapable hooks, yet it rewards close listening by revealing that adulthood can not only be just as exciting as adolescence but for one of the first times reflected on a rock album, it’s celebrated as being even more so.

For the complete story of Bring the Family and the circumstances surrounding it, pick up a copy of Have A Little Faith: The John Hiatt Story , available wherever books are sold in hardcover, as an e-book, as an audiobook, and, coming in September 2022, in paperback .

March 15, 2022

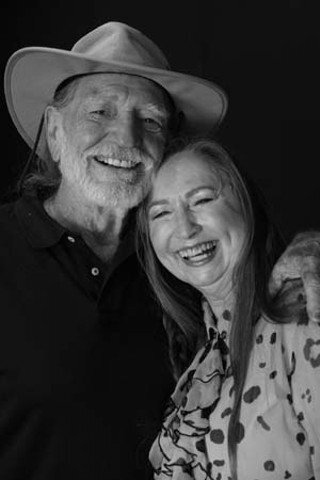

Remembering Bobbie Nelson (1931-2022)

The first member of Willie Nelson’s Family Band, and his first inspiration, passed away on Thursday, March 10. She was 91.

There’s a moment on Willie Nelson’s 1976 album, The Sound in Your Mind – it happens in the middle of “Amazing Grace” – where every player in the Family Band pauses, and all that’s left is the sound of Bobbie Nelson’s piano. She plays the melody all the way through, then the band rejoins as Willie begins the final verse. It’s in that moment where her Methodist roots were laid bare. You can hear Abbott Methodist Church, where she and her younger brother would sing and play before anyone outside of their hometown knew their names. It’s the sound of Sunday, a respite of worship and an afternoon of relaxation before returning to the cotton fields the next day. It’s a sound of the Nelson siblings’ first musical love, their love of gospel music, that carried them throughout their careers and their lives.

Bobbie Nelson was born on New Year’s Day, 1931, in the small farming community of Abbott, Texas. She and Willie (who joined the family two years later, on April 29, 1933) came into the world during the Great Depression. They were raised by their grandparents, whom they called “Mama and Daddy Nelson,” since their parents, Ira Doyle and Myrle Marie, left just months after Willie was born, no doubt looking for better opportunities.

Bobbie and Willie grew up working the fields and playing music. Mama Nelson, a music teacher by trade, taught Bobbie to play pump organ by age five, while Daddy Nelson, a blacksmith, bought Willie his first guitar, a Stella, when Willie turned six. Daddy Nelson succumbed to pneumonia not long after. The siblings helped Mama Nelson however they could, while honing their musical skills at Abbott Methodist Church (Bobbie had by then added piano to her repertoire).

They learned and practiced all the familiar Methodist hymns, songs that they would perform for that tiny church congregation as well as for thousands of fans all over the world for the better part of the next century, from “Amazing Grace” and “Precious Memories” to “In the Garden” and “Uncloudy Day.” Bobbie would also study classical, including the works of Bach, while Willie discovered the stylings of the Great American Songbook. The music they learned as kids they carried with them throughout their careers, showing up on albums as diverse and acclaimed as Stardust and The Troublemaker, both released with a raised eyebrow by the suits at Columbia Records at the time (The Troublemaker, in fact, had been recorded during Willie’s tenure at Atlantic, but shelved. It was finally released on Columbia following the huge success of Red Headed Stranger).

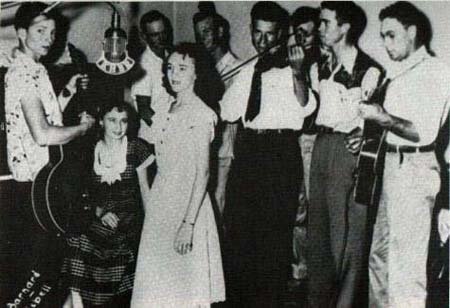

Before then, however, Willie and Bobbie first played with others in a group fronted by Bobbie’s future husband, Arlyn “Bud” Fletcher. Bud Fletcher and the Texans consisted of Bobbie on piano, Willie on lead guitar, their father, Ira, on rhythm, and Bud as the frontman and promoter. Together, they hit the rough and rowdy Texas beer joint circuit. Bobbie and Willie’s gospel roots got mixed up with hard-driving country and honky-tonk. Bobbie and Bud got married and had three sons. Tragically, Bud died in an automobile accident in 1961, leaving Bobbie a single mother of three.

Bud Fletcher and the Texans. Willie and Bobbie on the far left; their father, Ira, on the far right.

To make ends meet, Bobbie taught music and demonstrated organs for the Hammond company, so she was never far away from music or the piano. Then, in the early ‘70s, Wiilie, after a few false starts in Nashville, signed a deal with Atlantic Records, becoming their very first country artist. He asked Bobbie to join him on the sessions. She remained by his side on stage until the end.

The Family band quickly grew to include, among others, bassist Dan “Bee” Spears, drummer Paul English, and harmonica legend Mickey Raphael. Other members came and went, but the ones who stayed, stayed for life. (Spears died in 2011, followed by English in 2020. Mickey’s still going strong.) Their performances could rival that of the Grateful Dead or the Allman Brothers in their ragged-but-right jam band ethos. At once point in the ‘70s, the Family Band boasted two drummers and even two bassists. Even with all that force of sound, however, somehow, Sister Bobbie’s Steinway was the anchor keeping them grounded.

Photo by Todd V. Wolfson

No matter how popular Willie became, how many awards and platinum records he received, he always had “Sister Bobbie” by his side, and he always credited her with being his inspiration. She was the first to tell him what key they were in, what chord to play to compliment her. She was his rock, and no one sounded quite like her.

At every show, her solo turns would give Willie a break while taking audience members either to Sunday morning service or a Saturday night honky-tonk. Her take on Del Reeves’ “Down Yonder” was praised by Del herself, and she turned a whole new generation onto “Beer Barrel Polka” or “Pinetop’s Boogie Woogie.” Whenever her solo breaks came around in the Family Band’s occasional extended jams, they were almost always introduced by Willie with a sly, “Play it, Sister Bobbie.”

It was gospel, however, that resonated the most. Over the years, the Nelson siblings recorded several albums revisiting their roots (the best still being 1980’s Family Bible). And in 2006, they helped renovate the Abbott Methodist Church, the place where it all began, returning it to its former glory. It was a gesture that was born out of appreciation for a town, a community, and a higher power, that had helped make them the successes they became. When they started to play the ceremony commemorating the renovation that hot July day, all those miles and decades faded away and they were kids again, pushing against what the rest of America at the time was calling a Great Depression with faith in God, a love of music, and a belief that everything was going to be all right, no matter what. “What A Friend We Have in Jesus” is how they opened the ceremony, and they were right back where it all began, with each other. With family.

February 18, 2022

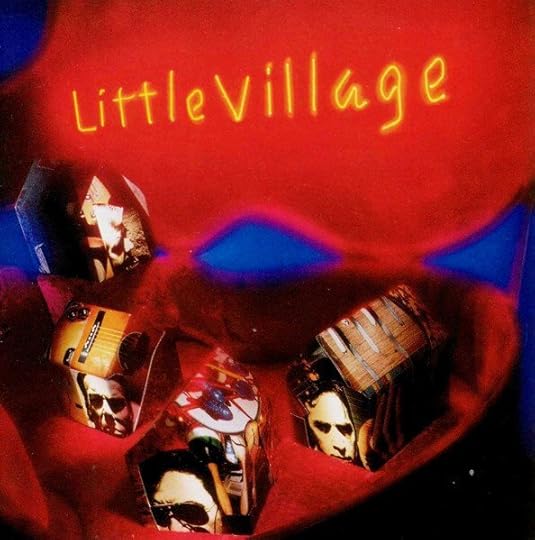

Don’t Bug Me When I’m Working: Little Village At 30

A look back at the only studio album by Ry Cooder, John Hiatt, Jim Keltner, and Nick Lowe released under the moniker Little Village, 30 years later.

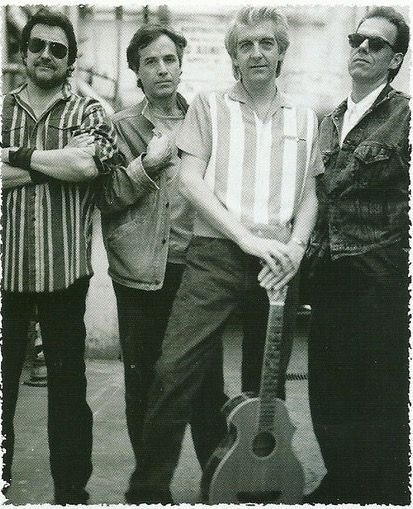

l-r: Jim Keltner, Ry Cooder, Nick Lowe, John Hiatt

The following includes outtakes never before published from Chapter 13, “Don’t Bug Me When I’m Working,” of Have A Little Faith: The John Hiatt Story , available here and wherever books are sold.

“Go ahead, we’re rolling, take one.”

“Go ahead, we’re rolling, take one.” Leonard Chess was perched behind the board in the control room at 2120 South Michigan Avenue - the storied address of the legendary Chess Records - in Chicago, Illinois one afternoon in early September 1957. The label had recently moved into its new location (which was originally conceived and constructed by architect Horatio Wilson in 1911 and updated in 1956 by John S. Townsend Jr. and Jack S. Wiener) earlier that spring, where it would produce some of the most exciting and lasting music of the twentieth century and beyond. Towering figures in blues, soul, doo-wop, and rock and roll all recorded for Chess in that era: Chuck Berry, Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Little Walter Jacobs, Etta James, and so on. On this day, however, Leonard was overseeing a session for Sonny Boy Williamson II, an artist from (it’s assumed) Glendora, Mississippi that had been with Chess’s subsidiary, Checker, for a couple of years, recording such seminal blues classics as “Don’t Start Me To Talkin’” and “Keep It to Yourself,” among many others.

Williamson was born Aleck Ford (somewhere between 1897 and 1912, no one really knows) but later changed his surname to Miller after his stepfather, Jim Miller. He picked up the nickname “Rice” as a child, due to his love of rice and milk. He would also occasionally go by “Little Boy Blue,” eventually settling on the nickname of the already popular bluesman John Lee “Sonny Boy” Williamson as his own. (The original Sonny Boy passed away in 1948.)

Not much is known of Williamson (we’re referring to Aleck “Rice” Miller, or Sonny Boy II as “Williamson” for the duration, so as not to fully confuse) in the first thirty years of his life, other than he used to pal around with Robert Johnson, Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup, and Elmore James, playing music in various juke joints and parties, and on various street corners throughout the south. He also worked for tips with Robert Junior Lockwood, Johnson’s stepson, from Clarksdale, Mississippi to Helena, Arkansas in the late 1930s into the 1940s. After adopting the moniker Sonny Boy Williamson II, he appeared on KFFA in Helena with Lockwood during “King Biscuit Time.” The program was simulcast throughout the delta and he would tour as part the King Biscuit Entertainers during the better part of the forties. Williamson toured a few more years with the likes of Howlin’ Wolf and Elmore James before signing with Checker in 1955. He would live another ten years, influencing and later even sitting in with, an up-and-coming generation of white boys devoted to the blues, from the Yardbirds to The Band.

Aleck “Rice” Miller, a/k/a Sonny Boy Williamson II

“Name It What You Wanna”“What’s the name of this?”

Back at the board at 2120 South Michigan, Leonard Chess was, by his point of view, asking a simple question.

“‘Little Village,’” Sonny Boy Williamson II replied, his voice booming into the vocal mic with the confidence and devil-may-care attitude of someone who’s spent a lifetime singing, playing, and living the blues.

His reply is followed by just enough silence for one to be able to picture the look of confusion Williamson undoubtedly witnessed wash over Chess.

“A little village, motherfucker! A little village!” Williamson shouts. Not with anger or malice, but impatience.

Chess talks over him. “There's isn't a mother fuckin' thing there about a village, you son of a bitch! Nothin' in the song has got anything to do with a village!” In the background, you hear some of the musicians gathered at the session, a who’s who of Chicago blues session royalty (drummer Fred Below, bassist and bandleader Willie Dixon, pianists Lafayette Leake and Otis Spann, guitarists Eddie King Milton, Luther Tucker, and Williamson’s old sidekick, Robert Junior Lockwood) cracking up.

“Well, a small town!” Williamson attempts to clarify. Not that he really cares. He just wants to get on with the take.

Chess isn’t having it. “I know what a village is!” He snaps back. In the background, Lockwood, Milton, and Tucker noodle around as the two alpha males trade barbs.

“Well all right, goddamn it!” Williamson responds. “You know, you don't need no title! You name it after I get through with it, son-of-a-bitch! You name it what you wanna. You name it your mammy if ya wanna!”

With that, and a snare hit from Below as a final punctuation to Williamson’s mild annoyance at Chess, who’s laughing it off as he repeats, “Take one, rollin’,” the song “Little Village” begins.

That exchange - seemingly heated to virgin ears but just another day on the job for those who were there - though recorded in September of 1957, didn’t see the light of day until 1969 (after both Williamson and Leonard Chess had left this world) when it was released in a twelve-minute version, complete with false starts and all the fly-on-the-wall between-takes-banter, on the fantastic odds and ends compilation, Bummer Road. Leonard Chess had a habit of holding on to an artist’s work, not releasing it until he felt it was the right time. This could mean songs could sit in the vaults for months - years even - before they would hit the streets, if they ever did at all. After Leonard’s death, the vaults were sifted through, and compilations like Bummer Road of several Chess artists’ material was packaged and released out into the world, supervised by Leonard’s son, and future head of Rolling Stones Records, Marshall Chess.

It Takes A VillageAt least one copy of Bummer Road, or in particular the track, “Little Village,” made it to the ears of John Hiatt, Ry Cooder, Nick Lowe, Jim Keltner, and/or then-president of Warner Brothers Lenny Waronker, because “Little Village” was chosen as the official band name of the four musicians that had been reassembled to grace the world with another album - and this time a world tour - for the first time since recording the now-classic John Hiatt album, Bring the Family over four days back in February of 1987.

“I think Ry came up with that,” John Hiatt replies when asked who suggested the name, Little Village. As for what brought Hiatt, Ry Cooder, Nick Lowe, and Jim Keltner back together for the first time since Bring the Family, “We just thought it’d be good to make another record together and have it not be one or the others’ solo records. We thought it'd be fun to make a record as a band.”

Ry Cooder recalls, “It seems to me that Keltner and I were sitting around one day. ‘What could we do?’ We talked about John and we talked about Nick. ‘Well, what if we were a group but not as a high backup band for Hiatt, but as a cooperative band, you know, as a real band. So then the calls went out and we went to Lenny Waronker.”

Nick Lowe explains, “I think because Bring the Family was so well received, and people were so excited about it, I think that got Lenny Waronker to get his checkbook out. And in a way, that was one of the reasons why the record didn't really work.”

Lenny Waronker, a second-generation record man (his father Sy started Liberty Records) who grew up in Hollywood and was childhood pals with Randy Newman, started working under Mo Ostin at Reprise as an A&R man. Over the years, he helped build Warner/Reprise into one of the most powerful and respected record companies in the world, guiding the careers of everyone from Neil Young and Joni Mitchell to Little Feat, Rickie Lee Jones, and the Doobie Brothers. He also threw his label’s support behind the Traveling Wilburys, a “supergroup” - Bob Dylan, George Harrison, Jeff Lynne, Roy Orbison, and Tom Petty - that came together quite organically at first.

In January of 1987, a month before Jim Keltner would meet up with Cooder, Lowe, and Hiatt for the four-day session that would become Bring the Family, he had started working with George Harrison on the ex-Beatle’s next album, the Jeff Lynne-produced, Cloud Nine.

Keltner remembers: “The Wilburys came about from Jeff and George when we were doing Cloud Nine at Friar Park (Harrison’s estate in Henley-on-Thames, England). That record was Jeff's first time working with George, and they really got on well, having fun. One particular night, I remember they were being really silly with that crazy Monty Python type of humor that we all love so much. And they were saying all these silly names: Willoughbys - something about Willoughbys, I remember; the “Climbing Willoughbys” and then the “Traveling Willoughbys” and then...it somehow finally worked its way to the Wilburys.”

The debut album by the Traveling Wilburys, Volume One, was released in October of 1988, eventually selling over three million copies in the US. In light of its success, Waronker figured the public - especially middle-aged, money-making, spend-happy baby boomers would be hungry for more Avengers or X-Men-style groupings of veteran musicians, or “supergroups.” After all, this was a generation that grew up with the likes of Cream and Blind Faith. They were no strangers to superstars collaborating.

Aside from the commercial aspect of it, Waronker was a big fan of Rockpile, the rock and roll powerhouse composed of Dave Edmunds, Billy Bremner, Terry Williams, and Nick Lowe that were responsible for, among others, Lowe’s Labour of Lust album and Dave Edmunds’ Repeat When Necessary, both from 1979, and, sadly, their only album under their own name, 1980’s impossible-to-live-up-to-its-hype-but-still-not-bad-at-all, Seconds of Pleasure. Rockpile had Nick Lowe, Lowe had produced side two of Hiatt’s Riding With the King album, Hiatt had toured with both Lowe and Cooder over the years, and with Keltner, all four had played on the now-classic Hiatt album, Bring the Family. Waronker had been associated with Cooder going back to his first album, and Cooder had also played on Randy Newman’s landmark, 12 Songs. It all started adding up.

Since the Bring the Family lineup had never toured, fans of that album were undoubtedly hungry for a reunion. Why not give it a shot? The fact that the Wilburys were still fresh on everyone’s mind, and that Keltner was also that outfit’s drummer (under the alias, Buster Sidebury), couldn’t have hurt, either.

“We all have a lot of respect for each other, that helps,” Hiatt admitted in 1992. “I’ve worked with Ry since 1980 and he's taught me a lot. He was the first guy I felt that really liked the way I played guitar. It meant a lot to me. Nick is a natural bass player with a sound you can hang your hat on. Jim is the most musical drummer I've ever worked with. He's the secret ingredient for the band... the outside curveball that made it all interesting.”

Ry Cooder admitted in the press materials for Little Village’s self-titled album, “For years I thought I was missing something because, for my money, bands make the best music. It might be the Louis Amstrong/Earl Hines band or Sleepy John Estes and Hammy Nixon or whatever, but you get a buzz that way...a spin. Things happen that you can't predict and sometimes you get more than just what you put into it. Anyway, I've been slogging along for a while, having an okay time, but I realized that I really wanted to be in just that kind of unpredictable situation. I wanted to be pulled along by something in an unknown direction. Keltner, who I've worked with for going on twenty years, and I talked a lot about this and when we got together to do John's Bring the Family with Nick on bass, we came up with a really good quartet sound. Eventually, amorphously, it just kind of pulled itself together. It's miraculous, I think.”

At the same time, Cooder was still apprehensive about the band dynamic. “I always thought bands were a hotbed of fighting and contention and that you had to throw tv sets out the window, or something.”

The SongsIt all comes down to the songwriting, and Little Village had three exquisite master craftsmen - and one secret weapon - all working together. The results may not have been revelatory or groundbreaking, but taking a closer look at the songs that comprise Little Village 30 years on, it’s obvious that most of them were not really given a fair shake due to unrealistic expectations.

“Don’t Go Away Mad” for instance, sneaks into your subconscious. With lyrics that turn the old line, “don’t go away mad, just go away” on its head: “don’t go away mad, stay here and be angry, too,” the track is just plain infectious. The melody has the hook, yes, but what shouldn’t be overlooked is the rhythmic template. Keltner is a master of groove and rhythm; as anyone who’s played with, or even watched him over the years will attest. In fact, many of the more interesting moments musically on Little Village occur due to the help of Keltner’s wacky but inventive grooves and that guitar compost of his.

“Inside Job” is another highlight of Little Village. Keltner’s “crazy sequence sounds” lay down the groove until Hiatt’s voice slides over a subtle guitar figure. The song finds John Hiatt in pure soul mode, with a feel that wouldn’t sound out of place on any Robert Cray album. Hiatt’s falsetto hits in just the right spots. After the first chorus, the intensity picks up; Keltner comes in on the full kit and the track starts grooving even harder as the soul flows deeper. Hiatt sings of giving love to get love, and by keeping it inside, a relationship will never realize its full potential. As he sings, “it was an inside job, but baby we worked it out.”

Invariably, comparisons were made between Little Village and this lineup’s previous effort, Bring the Family. Although there were some fun moments on Family (“Memphis In the Meantime” being the most obvious example), “quirky” would not be the first thing to come to mind when one thinks about that album. Whereas Little Village seemed steeped in quirk. Its opening track is “Solar Sex Panel,” to drive the point home. Based around the old bald man’s joke that his baldness is actually a “solar panel for a sex machine,” the song includes such phrases as “I’m an ultra-violet penetrator.” Not exactly high art (but neither was “Since His Penis Came Between Us'' for that matter). Actually, it could’ve been seen as a perfectly apropo anthem for a middle-age man in the early 1990s. The chorus was catchy, that inimitable Keltner groove was irresistible, and the lyrics were cheeky without being vulgar. Not a bad way to open the album, even if it was no “Memphis In the Meantime.”

"’Solar Sex Panel’ is a cheerful song for people who find themselves losing their hair,” Lowe explained in 1992. “The idea is that it's really a divine intervention that you're developing this patch on your head to take rays in that will improve your life in every way.”

Keltner added, “it's about not worrying when you get bald. It just means you've got more testosterone than other guys, that's all.”

Cooder clarified, “Actually, it's an ecological love song that simply says love energy is clean and non-polluting. We're burning clean.”

Cooder, Hiatt, and Lowe all traded lead vocals for the album’s first single, “She Runs Hot.” “All you need to write a song is a little something to kick you over the edge,” Hiatt explained in 1992. “Ry is always collecting titles, like the song ‘She Runs Hot.’ My natural inclination was to put it in a car motif and place it in Hardin County, Tennessee, where I’ve been spending some time lately. a popular bootlegging territory.”

Hiatt also elaborated to Graham Reid in 1991 on research he did by looking through Low Rider magazine that led to coming up with the idea for “She Runs Hot.” “There’s a wonderful subculture of car worship here in Southern California among Mexican-Americans where they chop cars to the ground, install elaborate hydraulics and then have these hopping contests or go cruising down the boulevards. Because I came from Indianapolis where they have the Indie 500 I’ve always been into cars. In this magazine, they have these open love letters in a column at the back and it’s very touching...so open and direct and ultimately more poetic than anything I could come up with. It’s very inspiring and that stuff just gets to me.”

Do You Want My Job?Looking back, it’s understandable to hear how as a group they reached the sound they had on Little Village. They all had an offbeat approach and they weren’t afraid to show their senses of humor on their (Hiatt’s, Cooder’s, Lowe’s) own albums. At the same time, that sense of humor could turn dark, or the following song could completely change direction emotionally and become captivatingly sincere or devastatingly heartbreaking. The need for strong, committed companionship in “Big Love” and the immense sorrow laid bare on “Don’t Think About Her When You’re Trying To Drive” being the most obvious examples here.

“You wait to see what's going to work,” Ry explained in 1992. “You look for tile signs. ideas start to accumulate and gather their own momentum and pretty soon it's like greased lightning. The ballads are the ones to watch because they have to be real. Anybody can rock and twang and get off on the energy and hope for the best, but a ballad has to touch the emotions.”

As far as ballads go, “Big Love” is probably the closest Little Village comes to the sound listeners may have been expecting due to the impossibly large shadow cast by Bring the Family. Acoustic guitar-based and a simple chord progression add up to the album’s most traditional arrangement. The tempo is at tortoise speed; it’s as if Keltner’s beat is suspended in mid-air each time before the two and four. Lowe’s bass anchors the song while Cooder’s slide is at its most biting and guttural. It cuts out of the dark like a moaning beast, punctuating the soulful pleas of Hiatt’s vocal. It’s spare, it’s powerful, it’s the album’s best moment.

On the flip side, “Don’t Think About Her When You’re Trying To Drive,” a fan favorite, is a surprisingly slick production, complete with keyboard strings and radio-ready reverb. It wouldn’t have sounded out of place on a Jimmy Buffett album at the time, yet it proves once again how adept Hiatt was at crafting radio-ready pop diddies when the need arose. An almost quiet storm-type R&B melody rides atop beautiful guitar work by Ry and sympathetic straight-ahead rhythm section work from Lowe and Keltner.

"Don't Think About Her When You're Trying To Drive" was a Ry title,” Hiatt revealed in 1992. “When we started working on the words together, we'd fax the version back and forth, me in Nashville and Ry in LA. That's the way things evolved.”

Little Village closes with “Don’t Bug Me When I’m Working.” All three vocalists once again trade verses, this time elaborating on the warning of the title (“I’ve got a job to do...I don’t work for you,” etc). The music, naturally, is off-kilter yet infectious, and it all comes full circle as it concludes with - what else? - the audio of Sonny Boy Williamson II yelling at Leonard Chess, “little village, motherfucker! Little village!”

Don’t bug me when I’m working, indeed.

For the complete story of Little Village, including original interviews with all four members, be sure to pick up a copy of Have A Little Faith: The John Hiatt Story , available for sale here and anywhere books are sold.

To dig even deeper, check out this recent podcast as I discuss the album with hosts Matt Wardlaw and Jeff Giles.

February 16, 2022

The Record Player

Little Village was released on February 18, 1992. In recognizing its 30th anniversary, I talked with Matt Wardlaw and Jeff Giles on the album’s impact and how its aged over the years.

Click the image above to listen, get it on Apple, or wherever you listen to podcasts.

February 15, 2022

New & Notable for 2022 (Vol. 1)

The new year is already overrun with plenty of fantastic music. Here are a baker’s dozen of my faves so far…

[image error]

Bobby Rush - “Chicken Heads” (featuring Buddy Guy, Gov’t Mule, and Christone “Kingfish” Ingram)

Celebrating 50 years of his signature jam, the unstoppable force that is Bobby Rush is joined by another unstoppable force (and fellow octogenarian), Buddy Guy, as well as Christone “Kingfish” Ingram, and supported by the fierce muscle of Gov’t Mule. Smell the funk.

Kurt Vile - “Like Exploding Stones”

Set for a tax day release, the new album from Kurt Vile, (watch my moves), proves to be another spaced-out dream-fest, judging by the strength of this advance track. Let the swaying commence.

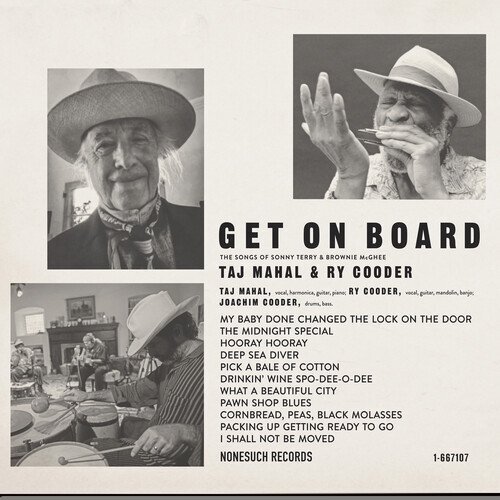

Taj Mahal & Ry Cooder - “Hooray Hooray”

The first taste of the first collaboration between Taj Mahal and Ry Cooder in well over 50 years, “Hooray Hooray” is a sneak peek at their upcoming tribute to Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, Get On Board, in stores April 22, 2022.

Big Thief - “12,000 Lines”

From their acclaimed new double-album, Dragon New Warm Mountain I Believe In You, Big Thief continue their dreamy-folk-Americana-whatever-you-call-it take on acoustic-based pop with a track that sums up their sound and approach in three glorious minutes.

Orville Peck - “Outta Time”

Teasing Bronco, his follow-up to his debut, Pony, Orville Peck shows off his impressive range on this top-down, freewheeling lament. One of the best songs of the year so far.

The Weeknd - “Less Than Zero”

From his magnificent project, Dawn FM, The Weeknd burrows himself into dark ‘80s synth-pop for this highlight on an album overflowing with them.

Aofie O’Donovan - “Phoenix”

From her third, and latest, Age of Apathy, O’Donovan channels strong Joni Mitchell vibes in this sublime, captivating track.

Eric Krasno - “Where I Belong”

Singer-songwriter/producer/multi-instrumentalist (and Lettuce co-founder), Eric Krasno’s new album, Always, is one of those all-killer-no-filler albums you hope would come along more often, but rarely does. The only downside is having to pick just one song for a list like this. I settled on the groove-that-won’t-let-go funk of “Where I Belong.”

Dig.

Spoon - “The Devil & Mister Jones”

Yes, rock’n’roll is still alive and well, and Spoon’s new album, Lucifer on the Sofa, is testament to that.

Exhibit A:

The Cactus Blossoms - “Hey Baby”

Yes, there are obvious nods to the Everlys, but the Cactus Blossoms also scratch that itch that was left by Foster & Lloyd and the O’Kanes in those glorious long-lost days of the “New Traditionalists” of mid-’80s county. You can’t help but get swept up in their easy-rolling thing.

Brent Cobb - “When It’s My Time”

Cobb’s latest album is his love letter to Gospel. Among all the usual suspects that filled Baptist and Methodist Hymnals over the years, is this late-night confession that’s as honest as it is moving.

Adia Victoria - “You Was Born To Die” (featuring Kyshona, Margo Price, & Jason Isbell)

From the fantastic A Southern Gothic, Adia Victoria reaches back to the roots of us all for this raw and chilling slice of gritty blues, with a little help from Kyshona, Margo Price, and Jason Isbell channeling his best Ry Cooder.

Bigdumbhick - “Ain’t Nobody Listening To Me”

Jeff Wall, a/k/a Bigdumbhick, is one of a kind, which is probably a good thing (as he’ll tell you), but we’re lucky to have his skewed take on the weird as well as the mundane. From his latest appropriately-titled, appropriately, A Little Bit Weird, “Ain’t Nobody Listening To Me” will immediately be felt by anyone who’s ever played for tips, beer, a slice of pizza, or anything - or nothing - at all, in front of a crowd that couldn’t care less.

If you’re more into handy playlists, here you go (or better yet, go buy physical copies of everyone featured here and elsewhere on this site, if it moves you).

February 11, 2022

Love Songs of John Hiatt

For Valentine’s Day/Weekend, here are 20 of John Hiatt’s greatest love songs. From “Feels Like Rain” to “Angel Eyes,” snuggle up with your better half and let these modern romantic masterpieces set the mood.

Leftover Feelings Doc Releases New Trailer, Announces Film Festival Appearances

John Hiatt and Jerry Douglas debut the first official trailer for their documentary Leftover Feelings: A Studio B Revival to coincide with the 2022 lineup reveal from the Boulder International Film Festival.

Directed by Ted Roach and Lagan Sebert, the film features interviews with Dolly Parton, Lyle Lovett, Rodney Crowell, Emmylou Harris, and more testifying their respect for Hiatt and Douglas, and their reverence for the Historic RCA Studio B located on Nashville’s Music Row. The documentary musically weaves the narrative together, led by Hiatt and The Jerry Douglas Band in up-close, all-access footage shot during the recording of their 2022 Grammy Award nominated album Leftover Feelings available from New West Records.

“I am such a fan of John Hiatt and his songwriting,” offers Dolly Parton in the film. “He has written some of the biggest hits ever and some of the greatest songs ever written in this whole wide world.” Rodney Crowell says, “Jerry Douglas…where would I start? Well, the dude’s won 14 Grammys, you can start right there.” Emmylou Harris adds, “It’s just a joy to play with him, he can play anything. It’s a beautiful marriage between them.”

Leftover Feelings: A Studio B Revival will be screening at the Boulder International Film Festival twice on Saturday, March 5th, in addition to upcoming screenings at the Amelia Island Film Festival February 24-27th, and at the Durango Film Festival on March 4-5th. These selections follow a World Premiere at the 2021 Nashville Film Festival, with more upcoming festival announcements coming soon.

Historic RCA Studio B serves as the perfect backdrop for John Hiatt and Jerry Douglas’ musical journey. Lyle Lovett explains, “Just walking into the room, you can’t help but imagine standing where Elvis Presley stood. There is an extra energy that comes from that.” The studio was one of the cradles of the “Nashville Sound” in the 1950s and 60s. A sophisticated style characterized by background vocals and strings, the Nashville Sound and Studio B played major roles in establishing Nashville’s identity as an international recording center. Hitmakers in Studio B included Country Music Hall of Fame members Eddy Arnold, Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson, Dolly Parton, Elvis Presley, and more. Songs recorded within its walls span decades, genres and emotions, with Presley’s forlorn “Are You Lonesome Tonight?” and Parton’s autobiographical “Coat of Many Colors” among them. Built when Hiatt was five years old, Studio B was designed for music to be made in real time by musicians listening to each other and reacting in the emotional moment. That’s what happened during the Leftover Feelings sessions: Five players on the studio floor, making decisions on instinct rather than calculation.

Find out more about Leftover Feelings: A Studio B Revival here.

January 13, 2022

My Favorite Album Podcast

I sat down with host Jeremy Dylan to talk all things Bring the Family, Have A Little Faith, and John Hiatt.