Raghavan Srinivasan's Blog, page 2

February 24, 2021

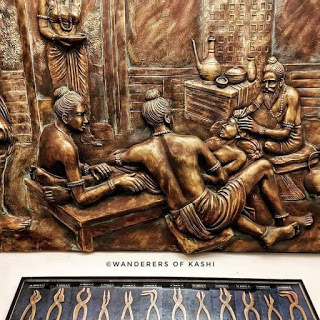

Sushruta Samhita – An awesome 2500 year old Sanskrit text on medicine and surgery!

The Sushruta Samhita is among the most important ancient medical treatises. It is one of the foundational texts of the medical tradition in India, alongside the Charaka-Saṃhitā, the Bheḷa-Saṃhitā, and the medical portions of the Bower Manuscript.

The Sushruta Samhita was composed after Charaka Samhita, and except for some topics and their emphasis, both discuss many similar subjects such as General Principles, Pathology, Diagnosis, Anatomy, Sensorial Prognosis, Therapeutics, Pharmaceutics and Toxicology.

The Sushruta and Charaka texts differ in one major aspect, with Sushruta Samhita providing the foundation of surgery, while Charaka Samhita being primarily a foundation of medicine.

The Sushruta Samhita, in its extant form, is divided into 186 chapters and contains descriptions of 1,120 illnesses, 700 medicinal plants, 64 preparations from mineral sources and 57 preparations based on animal sources.

The Sushruta-Saṃhitā is divided into two parts: the first five chapters, which are considered to be the oldest part of the text, and the "Later Section" (Skt. Uttaratantra) that was added by the author Nagarjuna. The content of these chapters is diverse, some topics are covered in multiple chapters in different books

The Sushruta Samhita is best known for its approach and discussions of surgery. It was one of the first in human history to suggest that a student of surgery should learn about human body and its organs by dissecting a dead body. A student should practice, states the text, on objects resembling the diseased or body part. Incision studies, for example, are recommended on Pushpaphala (squash, Cucurbita maxima), Alavu (bottle gourd, Lagenaria vulgaris), Trapusha (cucumber, Cucumis pubescens), leather bags filled with fluids and bladders of dead animals.

The ancient text describes haemorrhoidectomy, amputations, plastic, rhinoplastic, ophthalmic, lithotomic and obstetrical procedures.

The treatise mentions various methods including sliding graft, rotation graft and pedicle graft. Reconstruction of a nose (rhinoplasty) which has been cut off, using a flap of skin from the cheek is also described. Labioplasty too has received attention in the samahita.

The Sushruta Samhita, along with the Sanskrit medicine-related classics Atharvaveda and Charaka Samhita, together describe more than 700 medicinal herbs. The description includes their taste, appearance and digestive effects to safety, efficacy, dosage and benefits.

A number of Sushruta's contributions have been discussed in modern literature. Some of these include Hritshoola (heart pain), circulation of vital body fluids (such as blood (rakta dhatu) and lymph (rasa dhatu), Madhumeha, obesity, and hypertension. The first mention of leprosy is described in Sushruta Samhita. The text discusses kidney stones and its surgical removal.

February 11, 2021

Review by NewsworldInc - Yugantar by Raghavan Srinivasan ��� A Riveting Historical Fiction Exploring the Aspects that United Bharatavarsha 2300 Years Ago

Published by Leadstart, Yugantar by Raghavan Srinivasan is an intense historical fiction set in 4th century BC. The book is poignant in depicting the ossification of many aspects that built Bharatavarsha. As the tagline of the book states ��� The Dream of Bharatavarsha Takes Shape 2300 Years Ago.

The author is a well-read person, who must have done tremendous historical research to pen down this saga-like book. The ancient past of Indian sub-continent is interesting yet intriguing. According to the novel, the 4th century BC was a time of most conflicting philosophies and ideologies happening in and around Bharatavarsha. The author has considered philosophies and ideologies to understand the undercurrent development of Bharatavarsha in that time, around 2300 years ago. He has left religions and sects better ignored.

At this time the Indian sub-continent was chaos due to internal conflicts between provinces and was also exposed to outsiders like Macedonian and Greeks for invasion. As just after the preface, the author has put 7 interpretations that present an otherwise story of the making of this land, contrary to textbook context.

The book holds a meaningful stance in understanding the development our country. The better way to understand historical facts is through fictionalization. Raghavan introduces many indispensable characters in a fictional tone that acts as massive force to change that time ��� that���s why they are called Yugantar ��� it is a Hindi title which means changing the time. The political maps presented at the start of the book will definitely help readers to understand the main characters with their designated locations. The book is divided into 2 parts to keep confusion at bay.

Overall, it could be that book which can satiate your historical fiction craving with some amazing yet alternate facts and stats. The author used all his immense imagination and well-sketched figures to transport the readers in that time. From pleasure to research, this book holds a great relevance to those who wish to delve deeper to understand the multi-faceted aspects of the present Indian subcontinent.

Buy from Amazon/Kindle.

About the Author:

Raghavan Srinivasan is a graduate in Chemical Engineering from Madras University and a post-graduate in MBA from McMaster University, Canada. At present, he is a professional consultant in the social development area. He lives in New Delhi. As a consultant he has written and edited a number of documents. He has also been editing a magazine called Ghadar Jari Hai for several years now. It started as a print publication and is now an online magazine. He has written several cover stories, articles and travelogues for print and online newspapers. Raghavan is passionately interested in Indian literature, philosophy and history.

Review by NewsworldInc - Yugantar by Raghavan Srinivasan – A Riveting Historical Fiction Exploring the Aspects that United Bharatavarsha 2300 Years Ago

Published by Leadstart, Yugantar by Raghavan Srinivasan is an intense historical fiction set in 4th century BC. The book is poignant in depicting the ossification of many aspects that built Bharatavarsha. As the tagline of the book states – The Dream of Bharatavarsha Takes Shape 2300 Years Ago.

The author is a well-read person, who must have done tremendous historical research to pen down this saga-like book. The ancient past of Indian sub-continent is interesting yet intriguing. According to the novel, the 4th century BC was a time of most conflicting philosophies and ideologies happening in and around Bharatavarsha. The author has considered philosophies and ideologies to understand the undercurrent development of Bharatavarsha in that time, around 2300 years ago. He has left religions and sects better ignored.

At this time the Indian sub-continent was chaos due to internal conflicts between provinces and was also exposed to outsiders like Macedonian and Greeks for invasion. As just after the preface, the author has put 7 interpretations that present an otherwise story of the making of this land, contrary to textbook context.

The book holds a meaningful stance in understanding the development our country. The better way to understand historical facts is through fictionalization. Raghavan introduces many indispensable characters in a fictional tone that acts as massive force to change that time – that’s why they are called Yugantar – it is a Hindi title which means changing the time. The political maps presented at the start of the book will definitely help readers to understand the main characters with their designated locations. The book is divided into 2 parts to keep confusion at bay.

Overall, it could be that book which can satiate your historical fiction craving with some amazing yet alternate facts and stats. The author used all his immense imagination and well-sketched figures to transport the readers in that time. From pleasure to research, this book holds a great relevance to those who wish to delve deeper to understand the multi-faceted aspects of the present Indian subcontinent.

Buy from Amazon/Kindle.

About the Author:

Raghavan Srinivasan is a graduate in Chemical Engineering from Madras University and a post-graduate in MBA from McMaster University, Canada. At present, he is a professional consultant in the social development area. He lives in New Delhi. As a consultant he has written and edited a number of documents. He has also been editing a magazine called Ghadar Jari Hai for several years now. It started as a print publication and is now an online magazine. He has written several cover stories, articles and travelogues for print and online newspapers. Raghavan is passionately interested in Indian literature, philosophy and history.

Micro review: 'Yugantar' by Raghavan Srinivasan

By -TIMESOFINDIA.COM

Created: Jan 29, 2021, 08:00 IST Photo: Leadstart Publishing Pvt LtdHighlightsTitle: Yugantar: The Dream of Bharatavarsha Takes Shape 2300 Years Ago

Photo: Leadstart Publishing Pvt LtdHighlightsTitle: Yugantar: The Dream of Bharatavarsha Takes Shape 2300 Years AgoAuthor: Raghavan Srinivasan

Genre: Historical fiction

Publisher: Leadstart Publishing Pvt Ltd

Price: 299

Pages: 274 pagesYugantar is a historical fiction that gives a deep insight into ancient India.

Set in the fourth century BCE, the book follows a cast of interesting characters as they show how life was in those times. There is a blacksmith from Ujjayini, a Siddha doctor from Madurai, a mariner from Muziris, a trader from Pataliputra and a widow nun from Kaushambi. It was a time of great change as old systems were changing and foreign aggressors were invading and all the characters were drawn to and affected by the events.

Blog Espresso: Yugantar

https://infoespresso.data.blog/2021/02/06/yugantar-the-dream-of-bharatavarsha-takes-shape-2300-years-ago-by-author-raghavan-srinivasan/ February 6, 2021 by blogespresso

Book: Yugantar: The Dream Of Bharatavarsha Takes Shape 2300 Years Ago

Author: Raghavan Srinivasan

Available On: Amazon

Language: English

Rating: 4/5

Yugantar: The Dream of Bharatavarsha Takes Shape 2300 Years Ago is a historical fiction written by the author Raghavan Srinivasan. This book is set in 4th century BCE and is written in two parts: The gathering storm and the storm. It takes readers on the journey of the ancient India.

Map of mahajanapadas and trade routes also makes reader more aware about ancient India. Knowing about the period of 4th century BCE by reading this book is a great experience. It is about the time where opportunities and dangers were equal in Bharatavarsha. Reading about the situation in Ujjayini was a great experience.

Key actors and glossary given at the end of the book helped me to understand the book better. Cover photo is eye catchy and language of the book is simple. I am sure author must have done vast research to write this novel. Those who are interested in reading historical fiction should go ahead with this. It’s an insightful read.

Book Is Available On Amazon

Yugantar: The Dream of Bharatavarsha Takes Shape 2300 Years Ago

Nony's Reviews > Yugantar: The Dream of Bharatavarsha Takes Shape 2300 Years Ago

Yugantar: The Dream of Bharatavarsha Takes Shape 2300 Years Ago

byRaghavan Srinivasan (Goodreads Author)

Nony's review Feb 06, 2021

Yugantar: The Dream of Bharatavarsha Takes Shape 2300 Years Ago is a historical fiction written by the author Raghavan Srinivasan. This book is set in 4th century BCE and is written in two parts: The gathering storm and the storm. It takes readers on the journey of the ancient India.

Map of mahajanapadas and trade routes also makes reader more aware about ancient India. Knowing about the period of 4th century BCE by reading this book is a great experience. It is about the time where opportunities and dangers were equal in Bharatavarsha. Reading about the situation in Ujjayini was a great experience.

Key actors and glossary given at the end of the book helped me to understand the book better. Cover photo is eye catchy and language of the book is simple. I am sure author must have done vast research to write this novel. Those who are interested in reading historical fiction should go ahead with this. It's an insightful read.

https://www.goodreads.com/review/show/3821866891

December 26, 2020

Aryan Invasion vs Aryan Migration

Members of an archaeological team work in Rakhigarhi on March 4, 2015. Credit: Manoj Dhaka/AFP.and Scroll.in

Members of an archaeological team work in Rakhigarhi on March 4, 2015. Credit: Manoj Dhaka/AFP.and Scroll.in

In my novel, Yugantar, I had made several interpretations of Indian history, first of which was:

“There was no Aryan invasion from outside India. The earlier Indus civilisation disintegrated over several centuries due to various factors. By 330 BCE'—the period of this novel—there had been sufficient mixing of cultures, languages, religions, scripts and schools of thought which defined the concept of India”.

A reader while congratulating my efforts said “I do not agree with 1st interpretation. In the last decade there have been multiple genetic studies that there was an influx of large number of persons from central Asia 4500 years ago. Their genes are found in Indian population. Kokanastha Brahmins of Pune have 73%. The least are found in certain castes in Andhra and north Tamilnadu. The Gond tribals do not have these genes. Brahmins have higher % than others. Some of my school mates were genetically tested all of them have the central Asian genes”.

The point is that there is a difference between an influx or migration spread over several hundreds of years and an invasion, which is usually short-term and destructive. The Aryan ‘invasion’ was a British concoction to create a dividing line among Indians.

Recent studies published in Science and Cellthrow more light on this. The picture that emerges from these studies is one of diverse origin for the modern South Asian population. The main building blocks at the time of the Bronze Age (around four millennia ago) are the Ancient Ancestral South Indians, the people of the Indus Valley Civilisation and a significant migration from the Pontic Steppe. None of these people exist today but it is their mixing that caused most of the modern Indian population to be formed.

Of these, the Ancient Ancestral South Indians are probably the least studied and were present across parts of the subcontinent that did not fall under the Indus Valley Civilisation. Their closest modern-day relatives are the tribes of the Andaman Islands.

For all practical purposes, the people of the Indus Valley had no Steppe DNA. They mainly had a mixture of Iranian-farmer-related DNA as well as some DNA from Ancient Ancestral South Indians.

The Steppe population came in from grasslands in Eastern Europe corresponding to modern-day Ukraine, Russia and Kazakhstan. The genetic research identifies that this Steppe ancestry migrated between 2,000 BC and 1,500 BC, in about a span of 500 years.

So, the present day Indian population has three ancestors. I don’t know whether a DNA count has any meaning today when these original ancestors have mixed together for about 4500 years now. In the final count we are all Homo Sapiens who started migrating from Africa around 300,000 years back.

December 9, 2020

Is there something called Indianness?

To define Indianness in a country as tremendously diverse as India, home to a billion and above people, communicating through a mind-boggling 1652 languages and dialects(1), belonging to many regions and religions and to many thousands of castes, subcastes and tribal groups, is not an easy task. Any attempt to paint this broad landscape must necessarily involve some selection. In the discussion that follows I have attempted to look selectively at how various people viewed Indianness in various times and circumstances. To define Indianness in a country as tremendously diverse as India, home to a billion and above people, communicating through a mind-boggling 1652 languages and dialects(1), belonging to many regions and religions and to many thousands of castes, subcastes and tribal groups, is not an easy task. Any attempt to paint this broad landscape must necessarily involve some selection. In the discussion that follows I have attempted to look selectively at how various people viewed Indianness in various times and circumstances.

Before proceeding with this discussion, I wish to clarify that the idea is not to establish an exclusivity of Indian identity, but to look more closely at the different dimensions of this identity, all its different shades, to examine what really makes Indians tick and what they have to offer the world in this 21st century.

Lord Thomas Macaulay saw such high moral values and calibre in Indians that he came to the conclusion that the British colonialists would never ever conquer the country if they did not break the backbone of the nation, her spiritual and cultural heritage. So he recognised in Indianness various qualities such as spirituality, cultural heritage and enlightenment and started on a project to make Indians think that all that is foreign and English was good and greater than their own.

Indians have come a long way from the colonial enslavement of the period of Macaulay, the dark ages when their self-esteem was hauled over burning coals, when their ancient traditions and rich heritage were trampled underfoot. Today the Indian economy is supposed to be the third largest in terms of purchasing power parity. The government has already staked a claim for permanent membership in the UN Security Council. The Indian software techie has become ubiquitous, running programs and fixing IT systems in any part of the globe. With India having more degree holders than the entire population of France, the image of an Indian in the eyes of foreigners has changed drastically from the “mendicant doing the rope trick” stereotype. In the eyes of the world, the abstract trait called Indianness seems to be going through a massive transformation. But, is there something substantial under this ephemeral veneer, something distinctive and different from other cultures?

Over the millennia different people had different qualities attached to Indianness. Xuan Zang (Hieun Tsang), the famous Chinese traveller of the 8th century, spent many years in Nalanda University, and considered India as the fountainhead of knowledge and spirituality. Mark Twain likened Indianness to dreams and romance, fabulous wealth cohabiting with fabulous poverty. During the colonial period, British writers described Indianness with diametrically opposite adjectives – either being forever fragmented or spiritually transcendent, phenomenally talented or pathetically imitative, astonishingly superstitious or remarkably evolved, disgustingly servile or proudly rebellious. Mohandas Gandhi described Indianness above all as being tolerant and non-violent. The noted economist John Kenneth Galbraith once connected Indianness to an attitude of tolerating a “functioning anarchy”(2) . One can say that Indianness is all these combined, a typical Indian curry rich in all favours, tingling to all senses, an exotic mixture of a variety of spices. But can we leave it at that?

When commenting on Indianness why do independent observers seem to be at complete variance with each other? For example, let us look at the popular perception that Indianness is an insatiable desire for position and power. Mukesh Ambani has to live in the world’s costliest house that is only 27 stories tall! Lakshmi Mittal had to organise his daughter’s engagement in a place no less grand than the Palace of Versailles. In today’s Indian society everyone is judged by the position he or she occupies in the hierarchical scale. In the past, the caste hierarchy was prescriptive, positioning individuals in the social scale as a consequence of their birth. Today, various additional factors determine one’s position in society. What was started in 1947 by the new rulers has caught the imagination of future generations of the powerful as well.

Just as the British colonialists awed the natives with their power and position, today’s ministers and politicians awe their constituencies. While the civil servant cringes before his minister, he expects the same behaviour from his own subordinate. The body language of a person changes drastically depending on the situation – whether he is in front of his superior or his subordinate. Corruption, ghotala and sycophancy, chamchagiri are words in daily use in India. Every day the newspapers carry full-page advertisements commemorating a leader’s birthday or death anniversary or lauding some achievement. Sky high cut-outs and huge hoardings are typical landmarks in Indian cities. Chamchas of political leaders hang around their gates and are at hand to loudly applaud them when they make their fiery speeches. Film stars have fan clubs boasting millions of members who are willing to wait hours in the queue for tickets for the first show. MGR, who became Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu in 1977 had an estimated 27,000 fan clubs which had 1.5 million members at that time. The status of Ministers is proportional to the length of their convoys or the number of black cats guarding them. But hero worship has its black side too. A rising star will get a disproportionate following, excessive adulation, godlike reverence. But a fallen hero will overnight attract equally disproportionate vehemence and hatred. Those who fawned on him will desert him with lightning speed. One can witness this kind of behaviour in every society, but in India perhaps this is taken to the extreme.

But if one were to paint all Indians as incorrigible sycophants, venally corrupt and shameless show-offs they would be wrong. The majority of working people in India have nothing to fl aunt, and can hardly afford sycophants. The Bhaktas despised status, position and discrimination. Appar, a Saivite in the Bhakti tradition of the South, expressed his anger against discrimination in these words:

Why the meaningless chatter about the scriptures? What do you really gain by the meaningless castes and lineages?

"sathiram pala pesum salakkarghaal, kothiramum kulamum kondhu en seiveer?"

Another attribute that is often attached to Indianness is factionalism. Swami Vivekananda once said that ‘three Indians cannot act together for five minutes. Each one struggles for power and in the long run the whole organisation comes to grief’. All political parties of the ruling elite in India are faction-ridden. Members of Parliament and Legislatures defecting to other parties became so common that a special law had to be introduced in 2003 to prevent run-away defections. Splits in political parties and the jockeying of various groups for power is common news. Members who defect or threaten to defect are often herded off by their parties to remote locations and pacified with all kinds of handouts until the threat of a noconfidence motion passes away. The central leadership of the ruling and opposition parties of the ruling class has to be constantly vigilant, and use all the four principal methods or upayas, to retain power – sama (conciliation), dama (blandishment), bheda (sowing dissensions in the enemy camp) and danda (punishment).

Can we conclude that all Indians are and have been compulsive factionalists? The story of the Great Ghadar of 1857 refutes this hypothesis. During this uncompromising struggle against British colonialism a vast majority of Indians were united in purpose, irrespective of their caste, religion and region. People simultaneously rose up in many cities from Raigad in the West to Jalpaiguri in the East, from Thanjavur in the South to Peshawar in the North-west. Hundreds of patriotic kings and princes joined the Ghadar. Major sections of the army, the Madras Cavalry, the Bombay infantry and the Punjab garrisons together revolted against their British officers along with the bulk of the Bengal Army in the Indo-Gangetic plain. The same unity and purpose of action pervaded the entire struggle for freedom from the colonial yoke. The emergency of 1975 provoked a massive and united opposition from Indians across the entire length and breadth of the country. While on a day-to-day basis Indians are divided by region, caste, religion, language and political affiliation, these divisions tend to vanish when they are faced with a national crisis.

Today, a handful of big Indian business magnates such as the Tatas, Birlas, Mittals and the Ambanis claim that they are the driving force behind the recent phenomenal growth of the Indian economy. The Finance Minister claims that it is his clever policies that saved India from the recent global crisis. The Governor of the Reserve Bank claims that it is his monetary policy that will control inflation and spur demand. Even the Prime Minister doesn’t hesitate to give his advice to global leaders about how to manage their economies. This hubris is being lauded by The New York Times as a sign of the “awakening elephant”. John Lawrence, the Viceroy of India once declared that “we have not been elected or placed in power by the people, but we are here through our moral superiority, by the force of circumstances, by the will of providence”(3) These colonial and imperialist values have rubbed off on the Indian rulers as well. While it is the rich natural resources and the vast labour and talent of our people that is contributing to the growing respect and admiration that the country is getting from all over the world, the cabinet, bureaucrats and business tycoons take all the credit.

One rarely comes across the egotistical “I” in the evolution of Indian thought over the millennia. The Indian conception of rights never fell into the crass pit of the conception that “the individual is above everything else”. Indians recognised that they had both rights and duties as members of society. The interests of individuals have to be in harmony with those of the immediate collectives and the larger society. The King had his duty and so had the traders and artisans. Those who did not perform their duty had no rights as well.

Even today, vast tracts of resources such as hills, watersheds and grazing land are commonly owned, and jointly managed by communities. A huge movement is growing against multinationals such as Posco and Vedanta, because they refuse to acknowledge this tradition. Knowledge was also common property handed down from generation to generation. For example:

There is no one author for the huge compendium of Indian thought called the Vedas. The Ramayana and the Mahabharata have been freely translated and adapted in different regions in different ways. In what could be alarmingly termed as plagiarism in the West, there are an estimated 1000 versions of the Ramayana in eleven Indian languages and ten South and South-east Asian languages(4). Although these versions acknowledge Valmiki as .their inspiration, they are far from translations. They are independent works drawing on the immortal myth adorned with the philosophical and literary influences of their time. While the Arthashastra, the ancient Indian text on political theory and statecraft, is attributed to Chanakya, historians believe that there were at least three Chanakyas who lived at different times, and that the first version of the text itself was an improvisation over earlier texts. Avvaiyar was the name given to many women poets who lived at different times and contributed to Tamil literature. The name was actually a title which meant “respectable good lady”. The quality of the author mattered more than the individual’s personal traits.One may conclude that the idea of patents and copyrights was alien to Indian thought and tradition, where texts on philosophy, medicine, art, music and craft were feely exchanged, embellished and handed over from generation to generation. The possibility that ginger and turmeric, grown, improvised and used for millennia, can be patented and owned by some multinational, surprises the Indian peasants. Similar would be the astonishment if one were to suggest patenting the Bhagavad Gita or the concept of zero. Perhaps there is something called Indianness after all.

Kishore Biyani, the retail trade magnate, who owns massive retail chains such as Big Bazaar, once declared in an interview that when hiring people, he looks out for Indianness(5) ,Anybody who does not understand India or Indian thinking” . we don’t hire”, he said. When the interviewer doggedly asked him how he would judge that, he was confident that just one meeting with the applicant would establish that. There are, of course, some easily identifiable traits in Indians. For example, one has to be aware of selected members in the World Cup cricket team to be called an informed Indian. Indian cricket today earns as much as the rest of the world put together. Though predominantly a masculine pursuit, 77 million Indians watched the Champions League in 2010 (6) Love for films is again one more trait that Indians can be identified with. India is the world’s the most prolific movie market and the largest producer of films.(7) In 2009, India produced a staggering total of 2961 films. 3.2 billion movie tickets were sold last year (8), almost 3 tickets per head. The myths around Rajnikant, the superstar of Tamil films, would make Superman look like a wannabe. Just as the English love football and the Swiss love cheese, Indians love cricket and movies. Besides these superficial traits, however, is there a trait which the whole world recognises as something distinctly Indian?

Often foreigners associate Indianness with Gandhi’s credo of ahimsa, non-violence. So intense was the influence of this doctrine on the Indian freedom movement that India is perhaps the only country in the world where colonial institutions were preserved intact and even embellished by those it dominated for centuries. The new Indian rulers effortlessly moved into palaces and posts vacated by their colonial masters. The myth of ahimsa as intrinsic to the Indian psyche was sold by Gandhi and conveniently bought by the British. Warren Hastings, the British Governor General, once described the Indian character as: “They are gentle and benevolent, more susceptible of gratitude for kindness shown them, and less prompted to vengeance for wrongs inflicted than any people on the face of the earth”. And then he proceeded to cruelly take advantage of this disposition. A gentle and forgiving disposition on the part of the ruled is definitely a god’s gift for the invader. Gandhi devised a form of protest that was a perfect fit for this colonial perception of the Indian temperament. The Ghadar of 1857 had earlier shattered this perception to pieces, but forces were unleashed by the colonial establishment to reinforce this myth to make violent overthrow of colonialism look non-Indian and alien. Indians may not have the murderous passion of the Crusaders, or the brutal disdain of the Turkish conquerors for their subjects. But when pushed to the brink, they can be as retributive as any insurgent people. Revolutionary movements like those led by Bhagat Singh and the countless number of armed uprisings such as the Tebhaga and the Telengana confirm this. In his book, “India: Emerging Power”, Stephen Cohen observed that India was “uniquely unassertive towards others”. Historians have pointed out that unlike Mongols, Turks or the European powers, Indian kings never pursued military conquests. Rajaraja Chola led an expedition all the way to Kampuchea, left many temples and viharas behind but not military outposts. Many strategists of the ruling class go so far as to argue that it is this so-called unassertiveness that is leading to the acceptance of India’s rise by other powers as a “peaceful” phenomenon.

In 2008, Indian authorities reluctantly admitted that at least 47,000 people were killed in the recent two decades of insurgency in Kashmir (9). When hundreds of battalions of the Indian army have been deployed to contain the insurgency in Kashmir and the North-east, it is hard to believe that Indians are innately unassertive. If survival and safety of life and limb was the main consideration, then Indians would have never resisted the onslaughts of foreign invaders at great cost to life and property from the time of the Mughals and even earlier.

The argumentative tradition of Indians has been discussed extensively in literature. The Vedas, composed in the second millennium BC, tell stories, speculate about the world and ask a lot of questions, including such questions as “did someone make the world or was it a spontaneous emergence, and is there a God who knows what really happened?”(10). Even an epic hero such as Rama was treated as a hero with both good and bad qualities, and subjected to uncomfortable questions by a pundit called Javali. Even emperor Alexander had to contend with argumentative Indians in the 4th century BC. When he expressed his annoyance at the scant respect that a group of Jain philosophers showed him, he received the following reply:

“King Alexander, every man can possess only so much of the earth’s surface as this we are standing on. You are but human like the rest of us, save that you are always busy and upto no good, travelling so many miles from your home, a nuisance to yourself and to others!… You will soon be dead, and then you will own just as much of the earth as will suffice to bury you”(11)

It seems that the Buddhist emperor Ashoka, as early as the 3rd century BC, laid down perhaps the oldest rules for conducting debates and disputations, and advised that opponents should be duly honoured in every way on all occasions. Women were not lagging behind men in such discussions. The examples of the ‘arguing combat’ between Yajnavalkya and Gargi, the argument that Draupadi has with her husband King Yudhisthira, and the magnificent speech by the wronged Kannagi in the court of the Pandya King are examples. This tradition was followed by the exponents of the Bhakti and Sufi movements, when they questioned the caste system and inequality. Many of these exponents came from the working class: Kabir was a weaver, Ravidas a shoe maker, Nandanar an untouchable.

It is no surprise that this argumentative tradition and the political discussions gave rise to a robust political theory and institutions. Even at the time of the Vedas, there was a seven part state (king, minister, friend/ally, treasury, country, fort and army). The King and the seven institutions were subordinate to the people. The relationship between the raja and the praja changed in the post-vedic period. Nevertheless the continuing debate on political theory gave rise to various people’s institutions such as the Buddhist “sangha” (council), and the Sabhas and Samitis, each having specific roles and responsibilities.

Some authors such as Amartya Sen see a connection between this trait of Indianness — the tradition of argument, respect for divergent views, the acceptance of heterodoxy – and the current system of democracy and the “secularism” of the Indian state. But today’s parliamentary institutions are a far cry from the seven part state of the Vedic period or the councils, sabhas and samitis that thrived later and which were vibrant centres of debate and discussion, close to people’s concerns and fully accountable to them. India has been home to several religions – Hindus, Buddhists, Jains, Jews, Christians, Muslims, Parsis, Sikhs, Bahai’s and others – and several sects and subsects. Ashoka demanded “restraint in regard to speech, so that there should be no extolment of one’s own sector disparagement of other sects on inappropriate occasions, and it should be moderate even on appropriate occasions”. In contrast, the “secular fabric” that has been woven by the rulers covers up regular communal tensions and communal holocausts without punishing the guilty.

The 21st century is witnessing the emergence of a modern Indianness. It is a product of the challenges of the present and the opportunities of the future. In equal measure it draws strength from its past. Unlike in colonial times, no one can deny today that the Indian people who have evolved in the same crucible for thousands of years have developed common traits, cultural similarities, overlapping identities and above all a distinctive philosophy and world outlook. But under this awning of Indianness there is a growing assertiveness from below against the obstinate efforts of the “brown sahebs” to continue in the colonial tradition to paint Indianness as something backward, divisive, discriminatory and parochial, while a blind admiration of the European point of view or lifestyle is promoted as being global, modern and cosmopolitan. This portrayal has helped the ruling elite to advance their own interests at the cost of the vast majority of the Indian people. For the big business houses and the politicians, ministers, bureaucrats and judges who serve them, Indianness has been a convenient handle so far to keep the people divided while at the same time rallying them behind their ambitions to become an aggressive super power. But the search for a modern Indianness is making it increasingly difficult for the rulers to continue in the old way.

Footnotes:

1 Defining Indianness: Contributor Sam Chacko Shares His Thoughts on Indian Identity, http://geography.about.com/od/indiama...

2 “Being Indian”, Pavan K Varma, Penguin Books

3 Crisis of Values: For a modern Indian political theory

4 “The Kamba Ramayana”, Penguin Books

5 ‘We look for Indianness in every hire’ – Rediff Getahead.mht

6 http://www.espncricinfo.com/t20champi...

7 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cinema_o...

8 http://www.businessweek.com/news/2010... lmgoers.html

9 http://www.reuters.com/article/idUSDE...

10 The Argumentative Indian, Amartya Sen, Penguin Books

11 ibid

S Raghavan is the editor of the Ghadar Jari Hai Magazine. He has a deep interest in India’s cultural, economic and social past, present and future.

December 7, 2020

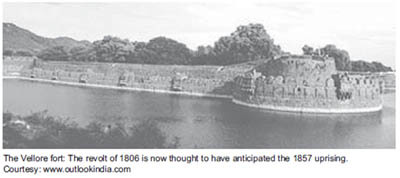

The story of the Vellore uprising

Nov 16, 2012

Not much is known about the Vellore uprisings against the British which took place in 1806. Other than British records which present the colonial perspective of the uprising, there are few reliable local records of this important milestone in the struggle of our people against colonial rule. Amaresh Mishra’s magnum opus, “War of Civilizations: India AD 1857, The Long Revolution” gives a well-researched rendering of the events that swiftly followed one another in the grim days of 1806.

Not much is known about the Vellore uprisings against the British which took place in 1806. Other than British records which present the colonial perspective of the uprising, there are few reliable local records of this important milestone in the struggle of our people against colonial rule. Amaresh Mishra’s magnum opus, “War of Civilizations: India AD 1857, The Long Revolution” gives a well-researched rendering of the events that swiftly followed one another in the grim days of 1806.

Not much is known about the Vellore uprisings against the British which took place in 1806. Other than British records which present the colonial perspective of the uprising, there are few reliable local records of this important milestone in the struggle of our people against colonial rule. Amaresh Mishra’s magnum opus, “War of Civilizations: India AD 1857, The Long Revolution” gives a well-researched rendering of the events that swiftly followed one another in the grim days of 1806.

The Vellore fort: The revolt of 1806 is now thought to have anticipated the 1857 uprising.

Looting was an organized activity among the East India Company officers. Lord Wellesley, later Duke of Wellington, was in the Seringapatnam battle where Tipu Sultan was defeated. In keeping with the times, he laid down the share of every officer and sepoy from the loot that was organized after Tipu was killed. The defeat of Hyder Ali and the death of Tipu, accompanied by the most widespread looting of Seringapatnam, rankled Indians at all levels. After Tipu Sultan was killed, his two sons were held in British custody in Vellore Fort.

Contrary to British propaganda, during the Anglo-Mysore wars, Hindu Madras army sepoys were not willing East India Company employees. They sympathized actively with Tipu. Things came to a head when in June 1806, Hindu and Muslim grievances coalesced. In 1806, the British administration decreed that soldiers can no longer wear caste marks, and would have to wear headdress like the British. Muslims were also required to shave their beard and trim their mustache.

In this way, right in 1806, the British adopted 1857-style defiling of the religious. This led the sons of Tipu, who were prisoners in their own palace at Vellore, to raise a revolt. There were other reasons also for the resentment. Changes in pay and refusal of permission to keep families, the use of soldiers for menial duties, were among them.

Acting cautiously, the Commander-in-Chief, Sir John Craddock, advised Bentick, Governor of Madras, to cancel the offending orders. But the latter refused. The troops, seething under the orders perceived as unjust and affecting their religious practices, and angry at inconsiderate officers, decided to march to Vellore and free Tipu Sultan’s sons.

Three companies of the 1st, 2nd and 23rd Madras Army Infantry garrisoned the Vellore fort which boasted a long and pro-Hyder Ali history. The Fort is believed to have been built around the 17th century.

In 1806, four companies of the 69th Foot, the Vellore based European regiment, ensured that English soldiers outnumbered Indians. Tipu Sultan’s sons and revolutionaries, probably initial Walliullahites, planned their move deftly. One of Tipu Sultan’s daughters was to be married on July 9 1806. The plotters of the uprising gathered at the Fort under the pretext of attending the wedding. Two hours after midnight, on July 10, the sepoys surrounded the Fort and killed most of the British. Rebels seized control by dawn and raised the flag of the Mysore Sultanate over the Fort. Tipu’s second son, Fateh Hyder, was declared King.

But, by defying to pillage the Fort, they allowed the surviving British to congregate on the ramparts. An officer who was outside the Fort when the rising began, went to the nearest military post, Arcot, the station of the 19th Light Dragoons and some Madras Native Cavalry.

The timing was crucial. Madras men did not expect a swift British response. Yet, with amazing courage they fought on. The initial attempts of the British were repulsed. But when the rest of the 19th Cavalry arrived, the British troops blew open the gates of the Fort with their galloper guns. They then charged and slaughtered any sepoy who stood in their way. No mercy was shown. About 100 sepoys who had sought refuge in the palace were dragged out, placed against a wall and blasted with canister shot until all were dead. John Blakiston, the engineer who had blown in the gates, recalled that although such punishment was revolting to all civilized beliefs, “this appalling sight I could look upon, I may almost say, with composure… it was an act of summary justice, and in every respect a most proper one”. Such was the nature of combat in India where the “civilized” conventions of European warfare did not apply! This snuffed out the unrest at a stroke.

Nearly 350 Madras Army soldiers were killed and shot. Many were court-martialled and sent to life imprisonment. Summary punishment of blowing up nearly a hundred soldiers by tying them to guns had a devastating impact in the Madras Army. On the other hand, Governor Bentick was recalled. New rules prohibiting tampering with soldiers’ religious and social customs were issued. The flogging of soldiers, which was common, was abolished.

Learning from the experience, the British started their infamous social engineering. They organized the army on caste and religious lines. They discouraged the Hindu middle castes from enlisting in the army. By 1857, the Madras army was not what it was during the Vellore uprising.

December 3, 2020

Angels and Demons in Indian Thought

Demonization is alien to Indian thought. Demonization is actually preparing the ground for justifying the most heinous acts against the designated ‘demon’ and totally violating the widely accepted concept of a rule based dharmayuddha. It is no wonder that the so-called “war on terror” that demonizes various peoples is totally alien to everything that makes us Indian, says S Raghavan.

In the best-selling mystery-thriller novel by the American author, Dan Brown, called “Angels & Demons”, a Harvard symbologist Robert Langdon tries to stop the Illumaniti, a legendary secret society, from destroying the Vatican City. It is a typical plot, sensationally presented no doubt, about the eternal conflict between angels and demons, between good and evil. When this novel was made into a movie, the conflict looked even more sensational on the celluloid screen. But can humanity be differentiated into Angels and Demons as easily as we differentiate day and night, life and death? Is there something called pure good and pure evil?

Demonization is alien to Indian thought. Demonization is actually preparing the ground for justifying the most heinous acts against the designated ‘demon’ and totally violating the widely accepted concept of a rule based dharmayuddha. It is no wonder that the so-called “war on terror” that demonizes various peoples is totally alien to everything that makes us Indian, says S Raghavan.

Demonization is alien to Indian thought. Demonization is actually preparing the ground for justifying the most heinous acts against the designated ‘demon’ and totally violating the widely accepted concept of a rule based dharmayuddha. It is no wonder that the so-called “war on terror” that demonizes various peoples is totally alien to everything that makes us Indian, says S Raghavan.

In the best-selling mystery-thriller novel by the American author, Dan Brown, called “Angels & Demons”, a Harvard symbologist Robert Langdon tries to stop the Illumaniti, a legendary secret society, from destroying the Vatican City. It is a typical plot, sensationally presented no doubt, about the eternal conflict between angels and demons, between good and evil. When this novel was made into a movie, the conflict looked even more sensational on the celluloid screen. But can humanity be differentiated into Angels and Demons as easily as we differentiate day and night, life and death? Is there something called pure good and pure evil?

For an Indian, who has inherited values from his or her forefathers, handed over from generation to generation over the millennia, good and evil are relative terms, one of which cannot exist without the other. What is termed as good depends upon the existence of what we call evil, and evil exists only in relation to good. Being interdependent values they cannot be separated. If we try to make evil stand by itself as entirely separate from good, we can no longer recognize it as evil. Probably, according to Indian philosophers, the difference between good and evil is not one of kind, but of degree.

For example, in that great Indian epic—the Mahabharata, the Kurukshetra where the great war was fought is declared a dharmakshetra and the ensuing 18 day war as dharma yuddha not because the evil Kauravas representing adharma are faced with the noble Pandavas representing dharma, as is commonly understood. It is called dharmakshetra because the rules of engagement of war are said to have been followed in this epic war.

No doubt there are many instances where both sides violate various rules of engagement. A pack of Kauravas ambush a lone Abhimanyu, Arjuna kills an unarmed Karna, the Pandavas play a trick on Drona regarding the death of his son Ashvatthaama; and Bhima gives a fatal illegal blow to Duryodhana below the waist, in the final gadaayuddha. But then the violators have to face the consequences. The chronicler Vyasa just records it. After all, Mahabharata is called itihaasa: this happened.

The Kauravas led by Duryodhana suffer defeat and destruction because they went against an important principle of statecraft called coexistence or ‘live and let live’. Duryodhana’s weaknesses like lack of control over hate and jealousy lead him not to accept the offer of coexistence that Pandavas had made through Krishna’s diplomacy. Such a principle which was in the interest of humanity was rejected. He preferred to be the unchallenged sole ruler, an absolute monarch and did not let Pandavas live independently even in five villages.

Unalloyed heroes and villains do not exist in the real world and hence they do not exist in Mahabharata. Vyaasa is not a hagiographer but an honest chronicler. Perhaps modern historiography has a lot to learn from him.

For example, Duryodhana’s virtue of valuing friendship above all else is hailed. The example given is that of his friendship with Karna. The moment Duryodhana recognised Karna’s merits he embraced him crossing the Varna barrier (Karna was supposed to be a sutaputra, a shoodra) and declared him a Kshatriya and his own equal by making him the King of the region of Anga. Duryodhana was loyal to this friendship till the end and in fact when Karna is killed in the war he mourns for him even more than at the death of his own brothers. At the same time his hatred of Pandavas and his jealousy are immense and beyond his control. According to the epic that is what led to his down fall, since one should control one’s senses and win over the six weaknesses: lust, anger, arrogance, jealousy, greed and infatuation for a fulfilled life.

Nothing is permanently good or evil. People are not classified as saints and sinners, followers of God or Satan (who incidentally does not exist in Indian thought). At birth no one is good or evil. External circumstances may force an individual into evil ways, but it is up to the individual to make the right choice.

Nothing is permanently good or evil. People are not classified as saints and sinners, followers of God or Satan (who incidentally does not exist in Indian thought). At birth no one is good or evil. External circumstances may force an individual into evil ways, but it is up to the individual to make the right choice.

According to Rg Veda, sin is conceived as a defilement clinging externally to somebody which can be expiated with external means. The concept of good and evil, right and wrong, virtue and vice, Rju and Vrijan, is essentially external in nature. That is why Indians tend to avoid categorising someone as absolutely good or absolutely evil. Only when an individual has lived his entire life in virtue and breathed his last, when it is no longer possible for him to stray from this virtuous path, can he be called a good person.

But what about expiation? Does a wrong doer redeem himself or is his fate sealed? Despite a common understanding of Indian culture as ‘fatalistic’ Indian world outlook and darshan is full of discussion of the dialectic between fate and individual human effort or individual choice. What is considered fate is actually the forces that one individual or even the whole human kind cannot control. These are the objective laws of nature and society, what Engels called ‘necessity’. (“freedom is the recognition of necessity”-F Engels). For example, Duryodhana violated the law that for social harmony there should be coexistence or diversity just as it is expressed in nature too. After that a devastating existential war became inevitable.

To reiterate, Indian thought does not consider anyone an eternal sinner. It is possible for him to make amends and turn a new leaf. Kedar Nath Tiwari argues in his book, “Classical Indian ethical thought”, that the Indian scriptures say that man can expiate his sin through the attainment of knowledge. This emphasis on knowledge is often noted in the Brahmanas such as

“He who has this knowledge conquers all directions”.

In verses such as

“He who has knowledge becomes a light among his own people”.

The emphasis of Upanishads on knowledge for the attainment of the highest good is marked.

The story of Prajapati is very enlightening in this respect. According to the story based on the Vedas, there was a great saint called Kasyapa Prajapathi. The Devas, Asuras as well as men were his children. He one day called them and told them, “The time has come for you to learn from me. But for that you should get prepared”. Preparation meant studying books, learning from teachers, and discussing with peers.

Once they were prepared, Prajapati called the Devas and told them, “Da” and asked them, did you understand? They replied, “Yes, sir we have understood.” The Devas understood Da as meaning Daama that is to exercise control over oneself. Prajapati repeated the exercise with the Asuras with the same word. But the Asuras understood, “Da” as Daana , which meant charity. When Prajapati did the same to humans, they interpreted Da as Dayaa which meant Mercy.

Prajapati recognised that Devas, Asuras and humans had both strengths and weaknesses in them. He taught whatever they needed to overcome their shortcomings. Since they had come prepared to learn, the words meant different things to each of them. The Devas needed self-control and humility of pride, the powerful Asuras needed to become charitable and the men needed to be merciful.

The moral of the story seemed to be that good and evil exists everywhere. One can overcome this evil by learning to address what causes that evil. This is true for individuals and nations.

My son was grappling with an essay on “Villains – Traditional and Modern”. He had many villains lined up for his essay – Othello’s Iago, Prof Moriarty, the archenemy of Sherlock Holmes, Lex Luthor of Superman fame, Batman’s nemesis Joker, and so on. You might have guessed by now that he is studying in a ‘cool’ English medium school and naturally even his examples would be Anglo-American! But when I mentioned to him about the villains from Indian epics he was struck. The villains in Indian epics were good and bad, compassionate and cruel, humble and arrogant, all at the same time. Even more of a problem – the heroes in Indian epics were also two-faced!

Take Ravana, the most well-known demon-king, for example. Valmiki describes him as the greatest devotee of Shiva. According to many folk versions of the epic such as Ram-kathas and Ram-kiritis, Ravana is believed to have composed the Rudra Stotra in praise of Shiva. He designed the lute known as Rudra-Vina using one of his ten heads as the lute’s gourd, one of his arms as the beam and his nerves as the strings! The image of Ravana carrying Mount Kailash, with Shiva’s family on top, is an integral part of Shiva temple art.

Take Ravana, the most well-known demon-king, for example. Valmiki describes him as the greatest devotee of Shiva. According to many folk versions of the epic such as Ram-kathas and Ram-kiritis, Ravana is believed to have composed the Rudra Stotra in praise of Shiva. He designed the lute known as Rudra-Vina using one of his ten heads as the lute’s gourd, one of his arms as the beam and his nerves as the strings! The image of Ravana carrying Mount Kailash, with Shiva’s family on top, is an integral part of Shiva temple art.

He is an even bigger hero in the South. It is not uncommon to see folk forms in the Tamil countryside that celebrate Ravana as a hero and Rama as the villain who treated women unfairly. In the Tamil version of the Ramayana, the Kamba Ramayanam, Ravana is highly venerated as a Vedic scholar, a connoisseur of music, a warrior, and an epitome of everything moral. In fact, a vedic scholar told me that Ravana created a mnemonic to remember the Vedic shlokas and it is used to this day by students of Vedas! In short, Ravana is a tragic hero, not a villain. While Rama questioned Sita’s chastity leading to her agnipariksha, Ravana is seen as the man who never violated her although he abducted her and took her away to his kingdom in Lanka. The beheading of Tadaka, the killing of Shambhooka—a shoodra who was engaged in Tapasya, the banishing of Sita, the killing of Vali, are considered as instances of Rama’s own wrong doings.

Here is a story by Devdutt Patnaik2 that somewhat tries to interpret this struggle between good and evil in a more enlightened way. The story goes that after firing the fatal arrow on the battlefield of Lanka, Ram told his brother, Lakshman, “Go to Ravana quickly before he dies and request him to share whatever knowledge he can. A brute he may be, but he is also a great scholar.” The obedient Lakshman rushed across the battlefield to Ravana’s side and whispered in his ears, “Demon-king, do not let your knowledge die with you. Share it with us and wash away your sins.” Ravana responded by simply turning away. An angry Lakshman went back to Ram, “He is as arrogant as he always was, too proud to share anything.” Ram comforted his brother and asked him softly, “Where did you stand while asking Ravana for knowledge?” “Next to his head so that I hear what he had to say clearly.” Ram smiled, placed his bow on the ground and walked to where Ravana lay. Lakshman watched in astonishment as his brother knelt at Ravana’s feet. With palms joined, with extreme humility, Ram said, “Lord of Lanka, you abducted my wife, a terrible crime for which I have been forced to punish you. Now, you are no more my enemy. I bow to you and request you to share your wisdom with me. Please do that for if you die without doing so, all your wisdom will be lost forever to the world.” To Lakshman’s surprise, Ravana opened his eyes and raised his arms to salute Ram, “If only I had more time as your teacher than as your enemy. Standing at my feet as a student should, unlike your rude younger brother, make you a worthy recipient of my knowledge. I have very little time so I cannot share much but let me tell you one important lesson I have learnt in my life. Things that are bad for you seduce you easily; you run towards them impatiently. But things that are actually good for you, fail to attract you; you shun them creatively, finding powerful excuses to justify your procrastination. That is why I was impatient to abduct Sita but avoided meeting you”.

This beautiful story gives an excellent perspective on good and evil. The demon-king is full of wisdom. And the man-god wants to benefit from it! In Indian culture, which not only “tolerates” diversity but celebrates it, there are very few binary answers. Every conclusion and judgement—which in itself is very rare—has to be qualified with context and many caveats that are full of relativisim. Certainty that can lead to absolutism is looked at with suspicion and tentativeness is more the norm. The parable of our search for truth (understanding reality) as the attempt of blind men trying to understand and describe the elephant is a very humbling one for anyone who thinks he has got it all!

Fundamentally the Indian mind sees change as a fundamental characteristic of the world around us and tries to grapple with it. It reacts to change, motion and development all around us. It reacts mostly with wonder and at times it tentatively theorises through phenomenological models.

The same applies to ‘judging’ a person. After all Indian theory of human nature (svabhaava) does not start with the binary theory of good and evil but with an empirical observation of coexistence of three broad characteristics (guna) namely satva, rajas and tamas in all individuals. It observes that proportion of these three gunas can change and manifest itself differently at different phases of the dynamic of the life of the individual. There is inheritance and ‘nature’ as well as modification by the environment (sanga—satsanga and dussanga) or ‘nurture’.

Does a realistic conception of good and evil exist only in ancient Indian texts? Does it have relevance in the modern world? D D Kosambi, the famous historian, mathematician, Indologist, used to say that in reconstructing the past India had a tremendous advantage in that even today cultural survivals from the ancient past exist all over the country. I would say that this is true of ancient Indian thought also. A modern Indian would not easily subscribe to the view, as various presidents of USA have propounded at various times, that there is an “axis of evil” which has to be eliminated by the civilized world in the interests of “our way of life” no matter what it costs.

Why go so far? Similar attempts at unalloyed demonization have been made by various organs of Indian state at various times regarding whoever they were trying to suppress unjustly or even physically eliminate within India or outside our borders

This practice of demonisation has led to wars of aggression and wars against “terrorists and fundamentalists” and the killings of innocent people—the most unjust and unjustifiable of all wars, while painting the act as dharmayuddha, carried out under the most extraordinary conditions of fighting pure evil. An Indian who has been taught to be self-critical would not subscribe to this self-righteous, absolutist approach. An Indian is constantly reminded since childhood that when one is pointing a finger at others, the remaining fingers are pointing back at oneself.

Criticism and self-criticism are ingrained in the Indian ethos. Demonization is alien to Indian thought. Demonization is not just a difference in philosophical approach but actually preparing the ground for justifying the most heinous acts against the designated ‘demon’ and totally violating the widely accepted concept of a rule based dharmayuddha. It is no wonder that the so-called “war on terror” that demonizes various peoples is totally alien to everything that makes us Indian.