Corey Robin's Blog, page 59

August 14, 2015

Why I’m Not Crying Over the Fate of Chancellor Wise

I’m hearing a certain amount of ruefulness being expressed over Chancellor Wise’s fate: that she’s somehow the victim here, that she was compelled to do the bidding of forces more powerful than she, that she’s a scapegoat for a larger, more fetid community of rule. I wish we on the left had memories that extended past yesterday’s headlines—and a larger appetite for justice. That Wise is being thrown under the bus by her co-conspirators I have no doubt. And I’m thrilled. For two reasons. First, Wise was never without agency. There’s sometimes a tendency on the left—whether out of a manic structuralism or a liberal sentimentality at moments of poetic justice, I don’t know—to so want to make individuals in power the faceless emblems of a structure that those individuals cease to have power at all. There are structures, there are constraints, but Wise always had the option of bucking those structures and constraints. She could have resigned in protest (not to mention get a better outcome for Steven Salaita) if she opposed the direction of things. Indeed, she’d be in a much stronger position now if she had: her reputation would be burnished rather than stained, and she’d probably have that goddamn $400,000 bonus, too. But she didn’t. Instead, for whatever combination of reasons, she pursued the course that got her to the place she’s now in. And for that she has no one to blame but herself. She was part of the rotten structure that did what it did to Steven Salaita; if she thought she was exempt from its workings, she was a fool. Second, if we want to honor our structuralism, we have to have a better sense of how this structure works. Right now, it’s a bit of a mystery: Who’s pulling the strings? The donors, the trustees, the president, who knows? The more pressure is put on Wise, the more she’ll be inclined to talk. And then not only may we find out how this damn thing works but we may also be able to throw it—or at least more emblems of it—under the bus. And get Steven Salaita his job back, which has always been my number-one priority in this fight. I often complain around here that we academics are optimists of the intellect and pessimists of the will. But in this case we seem to lack a will to power AND a will to knowledge. This is a moment to press on, to demand more, to expose more. It is not the time to express concern for someone who, whatever happens, will still return to a tenured position on the faculty where she earns $300,000 a year. Steven Salaita should have been so lucky.

On the Cult of Personality and the Tolerance of Rich People

Looking back on the fierce debate over “socialism in one country” between Trotsky and Stalin before the Executive Committee of the Comintern in 1926, which he witnessed personally, Joseph Freeman, editor of The New Masses and founding editor of Partisan Review, had this to say:

If I had known and understood more, I would have foreseen there and then that the dogma that personality counts for nothing in history would lead to the cult of personality; and what that dogma really meant, as it turned out, is that you don’t count and I don’t count and our neighbors don’t count and most of us must be content to be as they had not been—but HE, the great, brilliant, genial Leader, the most colossal thinker and hero of all times, HE counts all the time in every thing.

In a different vein, here’s Mike Gold in a reply to Ezra Pound from 1930:

Oh, this charming trait of tolerance one finds in people who have incomes.

August 13, 2015

Wise throws down the gauntlet, consults with lawyers over her legal “options” against UIUC

In a stunning turn of events tonight at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, the chancellor who hired the professor, then fired the professor by claiming he had never been hired in the first place; who resigned in the wake of an ethics scandal over her use of a personal email account (and destruction of emails) in order to hide evidence related to pending litigation over the firing of the professor; whose resignation was rejected by the UI Board of Trustees so that they could formally fire her instead (and thereby avoid paying her a $400,000 bonus previously agreed upon), is now resubmitting her resignation to UIUC and consulting with lawyers in order to consider her legal options and to protect her reputation from the very university that, under her leadership, systematically destroyed the reputation of the professor she fired by claiming he had never been hired in the first place.

Let’s back up.

Last Thursday, Phyllis Wise resigned from her position as chancellor of UIUC. The immediate cause, it seemed, was a federal judge’s ruling that day against UIUC’s motion to dismiss Steven Salaita’s lawsuit. The judge held in no uncertain terms that UIUC’s claim that it had never truly hired Salaita—and thus had not denied him the academic freedom and free speech rights it was bound to honor—was horse manure.

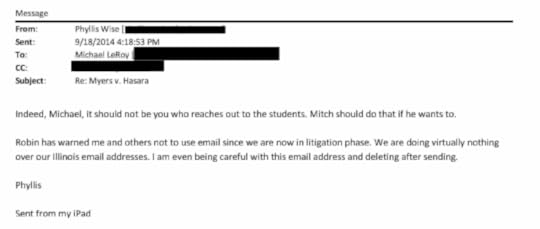

By Friday, however, it became clear that there may have been another reason for Wise’s resignation. UIUC released 1100 pages of emails, many related to the Salaita case, that Wise had sent from her personal account—and that she (or they) had not previously released as they had been obligated to do. In one of those emails, Wise admits that she had been warned by UIUC officials not to use UIUC email “since we are now in the litigation phase,” that she was “even being careful with this email address [her personal account],” and that she was even “deleting after sending” emails.

It was also announced that day that UIUC had conducted an internal ethics probe of Wise’s behavior regarding the emails.

In the next few days, two controversies exploded.

The first was over the email revelations, which not only cast Wise in the potentially criminal role of destroying—or “spoliating”—evidence relevant to a federal lawsuit but also potentially undermined, and rather severely so, UIUC’s own position in the Salaita lawsuit.

The second involved the $400,000 bonus Wise had managed to extract from UI President Timothy Killeen for herself upon her departure. Everyone from the governor of Illinois, who sits on the UIUC Board of Trustees, to Chris Kennedy, the former chair of the Board, criticized the massive payout to Wise. In Kennedy’s words:

I wouldn’t give someone $400,000 to leave peaceably if they (did what she did). My belief is that those emails will reveal behavior that should be investigated. This is actionable information. You can fire someone for cause for this. When have we started giving money to people who (do this)?

Yesterday, the Board reconsidered the payout to Wise. Hoping to avoid litigation (the terms of her contract seemed to stipulate that she was due some kind of bonus upon departure), the Board refused her resignation, made an arrangement for her to assume another position in the university, and voted to initiate proceedings to dismiss her. The operating assumption seemed to be that if the proceedings were successfully concluded against her, Wise would have no standing to sue for breach of contract.

Now we come to tonight’s stunning turn of events. Wise has rejected the university’s offer of a temporary position, has resubmitted her letter of resignation, and has issued the following statement:

In the past week, the news media has reported that I and other campus personnel used personal email accounts to communicate about University business; some reports suggested I did so with illegal intentions or personal motivations. This is simply false. I acted at all times in what I believed to be the best interests of the University. In fact, many of these same communications included campus counsel, Board members, and other campus leaders.

…

On Tuesday, in the spirit of placing the University first, I acceded to the Board’s and the President’s request that I tender my resignation. In return, the University agreed to provide the compensation and benefits to which I was entitled, including $400,000 in deferred compensation that was part of my 2011 employment contract. The $400,000 was not a bonus nor a golden parachute; it was a retention incentive that I earned on a yearly basis.

…

Yesterday, in a decision apparently motivated more by politics than the interests of the University, the Board reneged on the promises in our negotiated agreement and initiated termination proceedings. This action was unprecedented, unwarranted, and completely contrary to the spirit of our negotiations last week. I have no intention, however, of engaging the Board in a public debate that would ultimately harm the University and the many people who have devoted time and hard work to its critical mission. Accordingly, I have again tendered my resignation as Chancellor and will decline the administrative position as advisor to the President.

These recent events have saddened me deeply. I had intended to finish my career at this University, overseeing the fulfillment of groundbreaking initiatives we had just begun. Instead, I find myself consulting with lawyers and considering options to protect my reputation in the face of the Board’s position. I continue to wish the best for this great institution, its marvelous faculty, its committed staff, and its talented students.

Long story short: she’s calling her lawyers, preparing her next move against the University. One expert on these matters predicts she will sue. And UI’s President Killeen admits that the trustees’ move against her, in the words of ABC News, “could bring more litigation.”

This story has more irony than a Brecht play. In no particular order.

1. Salaita is hired but then is told, no, you’re not really hired, so that he can be fired. Wise is forced to resign, but then is told, no, you’re not really resigned, so that she can be fired.

2. Wise complains that not only is she the victim of a university administration that puts politics above principles and reneges on its contracts with its employees—all true, by the way—but that such actions are also “unprecedented.”

3. Suddenly, the UI Board of Trustees is concerned about contracts with its employees.

[Chair of the UI Board of Trustees Ed] McMillan said that his primary concern in negotiations with Wise was to be in compliance with her employment contract.

“That was the important thing from my standpoint, was trying as best we could to be in compliance with the agreement that she signed four years ago. That was the part I was very concerned about,” he said. “The lawyers were concerned about that also.”

4. In an article on Wise’s situation earlier today, before this latest news was announced, Inside Higher Ed devoted four full paragraphs to the, well, read for yourself:

But Raymond Cotton, a lawyer who specializes in contract negotiations on behalf of college and university presidents, was critical of the Illinois board. Wise is not Cotton’s client, and he said he doesn’t know the details of her contract or the board’s thinking. But he predicted that Wednesday’s developments will hurt the university.

Boards and presidents sometimes need to part ways, he said. And presidents may be less likely to do so if they think an agreement they make won’t be honored. And this in turn will affect the way the university is seen by potential candidates to succeed Wise. “As soon as Dr. Wise is gone, the board is going to be looking for a new president,” Cotton said. “What my clients tell me is that one of the key decision points is to look at how the board treated the prior president.”

Further, Cotton said that $400,000 may seem like a lot of money, but that the university was going to get “closure” for paying that sum. Instead, he said, the university may face other costs. “When presidents are fired for cause, they have nothing left to lose, so these cases end up in litigation, and that’s expensive, time-consuming and generally ends up being injurious to the reputation of the university.”

Cotton also said that academics should not be quick to cheer the board’s actions, whatever they think of Wise. University leaders made a deal with Wise and backed out after getting pressure from the governor and other politicians, he noted. “It is rarely in the best interest of a university for a board to yield to political interference by elected politicians,” Cotton said. “A question for the board is: Have they turned over their responsibilities to politicians?”

All this concern for how the Trustees’ move against Wise may negatively affect UIUC’s ability to recruit future presidents and chancellors. Not a word about how UIUC’s actions against Steven Salaita have already—not hypothetically but demonstrably— affected its ability to recruit graduate students, speakers, and new faculty. And all reported without any hint of irony. The pains of power are registered so precisely here. And those of the not-so-powerful?

In the meantime, the boycott continues. Just four days ago, another professor refused an invitation to speak at the UIUC.

Update (12:30 am)

As David Palumbo-Liu asks on Facebook, “She’s worried about her reputation?” That ship sailed long ago.

August 10, 2015

Academic Freedom at UIUC: Freedom to Pursue Viewpoints and Positions That Reflect the Values of the State

John K. Wilson has examined all of the emails that were released this past Friday: not merely the emails regarding the Salaita case, but also the emails dealing with two other cases, which Wilson makes a strong argument are related to the UIUC’s handling of the Salaita case.

Wilson’s piece is long and well worth reading, but lest readers overlook three astonishing quotes that Wilson has uncovered, which together comprise a rough definition of what academic freedom at UIUC might mean, I thought I’d highlight them here.

First, education professor Nicholas Burbules, a real piece of work as far as I can see, has emerged in the last few days as one of Chancellor Wise’s close confidants on the faculty. He seems to fancy himself, in these writings at least, as a kind of Machiavellian consigliere. But where Machiavelli’s counselor knew how to mould the prince to his own purposes, Burbules reminds one of nothing so much as those hapless Cold War intellectuals who thought they were taming and influencing the American state—only to discover, after it was too late, that it was it that was taming and influencing them. Christopher Lasch aptly characterized the farce of these buffoons more than a half-century ago:

In our time intellectuals are fascinated by conspiracy and intrigue, even as they celebrate the “free marketplace of ideas”…They long to be on the inside of things; they want to share the secrets ordinary people are not permitted to hear.

What drives these courtiers of knowledge “into the service of the men in power,” Lasch concluded, is “a haunting suspicion that history belongs to men of action and that men of ideas are powerless in a world that has no use for philosophy.”

Enter Professor Burbules. On February 14, 2014, Burbules advises Wise:

A related policy might address the question of “controversial” hires—this is murkier, because people’s ideas of what is controversial will differ. But a crude rule of thumb is, if you think someone’s name is going to end up on the front page of the newspaper as a U of I employee, you can’t make that decision on your own say so. You need to get some higher level review and approval.

Notice that Burbules doesn’t say that the university should exclude positions that have been proven to be fraudulent or false (e.g., the earth is flat, the sun revolves around the earth, etc.) No, what Burbules thinks is excludable are viewpoints and positions “that are not consistent with our values.” Now, you might instantly get suspicious here: one would have thought that if what marks a university is the freedom to pursue multiple and conflicting viewpoints and positions, it would be tough to get a more than thin consensus on what “our values” are. What are those values? Who gets to define them? Burbules doesn’t say. So we’re left with that “kick it upstairs” standard: the higher-ups get to define our values.

But, as if aware of what a craven standard this in fact is, Burbules decides to look for “a more principled statement of what the U of I stands for.” Here we come to our second astonishing statement:

We welcome the widest possible range of viewpoints and positions, but not all positions. And that there are some things that are not consistent with our values.

And who gets to define those values? Burbules doesn’t say. So we’re left with that “kick it upstairs” standard: the higher-ups get to define our values.

So let’s now go to the higher ups. And here we come to our third and final astonishing statement. From about as higher up as it gets: Chris Kennedy, chairman of the UIUC Board of Trustees.

The University, as the state’s public university, needs to, in many ways, reflect the values of the state.

So that’s it: at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, academic freedom is the freedom to pursue the widest possible range of viewpoints and positions, except for those that are not consistent with our values, which must reflect the values of the state.

This the marketplace of ideas from which Chancellor Wise was buying her wares.

August 8, 2015

Keeping Kosher and the Salaita Boycott

Since a federal judge ruled on Thursday that the Steven Salaita lawsuit would go forward—and rejected the UIUC argument that Salaita did not have a contract with the university—I’ve gotten a lot of queries from academics wondering whether the boycott of the UIUC is now over. I’ve replied that, no, to my knowledge, it’s not over, since the demand of the boycott is that Salaita be reinstated. Which he has not yet been. Until he’s reinstated, the boycott continues.

Ever since we declared the boycott, I’ve gotten these sorts of queries. From academics wondering whether the boycott has been called off or asking me whether some particular course of action they are considering would violate the boycott. I’m always made uncomfortable by these queries. For two reasons.

First, the boycott is a genuinely grassroots campaign with no formal or recognized leadership. For better or for worse, it doesn’t have any strict or agreed upon rules of engagement. Some signatories to it have declared their refusal to accept any and all invitations to speak at UIUC. Others have declared that they won’t read tenure and promotion files. And so on. So who am I to be denying or granting permission? I usually try to respond to folks by explaining my own position, what I am willing or not willing to do. But I’m not the Pope. Second, and related to that Pope question, I sometimes feel like I’m being asked to grant absolution. The person asking me seems dead-set on breaking the boycott, and merely checks in with me so that I’ll say it’s okay.

But this isn’t what I wanted to talk about. What all this back and forth about the boycott really makes me think about is…being Jewish. Specifically, about all those rules—so cockamamie and obsessive, so picayune and seemingly pointless—that hem in a Jew’s life from the day’s she born till the day she dies. The rule-bound nature of Judaism has long been a source of bemused irritation—and genuine wonder—to Jews and non-Jews alike. It’s also been a source or symptom of a not inconsiderable amount of anti-Semitism. But whether friend or foe, people have often asked of these rules: Why? Why this obsessiveness about the smallest, seemingly most irrelevant, details of life? As I wrote in my recent Nation piece on Hannah Arendt and Eichmann in Jerusalem:

If you stumble upon a bird’s nest, take the eggs to sustain yourself, but not the mother. So says the law. If you build a house, put a railing round the roof so no one falls off. If you lend money to the poor, don’t charge interest; if your neighbor gives you his coat as collateral, give it back to him at night lest he be cold. A king should not “multiply horses to himself”: perhaps to make him and his people stay put, perhaps to keep his kingdom focused on God rather than war. Who the hell knows?

In my Nation piece, I explored one possible answer.

That combination of seemingly antithetical ideas—that we always and everywhere think about what it is that we’re doing, that we always and everywhere think beyond what we’re doing—lies at the heart of a religion so dedicated to the extraction of the sacred from the profane, of locating the sacred within the profane, that it encircles human action with 613 commandments, lest any moment or gesture of a Jew’s life be without thought of God.

…

The point is that Judaism imposes a mindfulness about material life—the knowledge that it is out of our littlest deeds that heaven and hell are made—that turns our smallest practices into the peaks and valleys of a most difficult and demanding ethical terrain.

Over Passover, I mooted another: that maybe all the emphasis on rules and regulations reflects the Jews’ experience or memory—real or imagined—of bondage in Egypt. A slave’s life is a condition of subjection to the arbitrary will of another, of permanent lawlessness at the hands of a master. Is it so surprising that a class of men and women who only became a people through their emancipation from slavery, whose every injunction to believe in and obey God is justified via the memory of that slavery and emancipation, would make so much of a muchness of obedience to rules? The prefatory comment to the Ten Commandments reads: “I am the LORD thy God, which have brought thee out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of bondage.” The Ten Commandments—and the other 603—are meant to be the antipode to, the antithesis of, that experience of power unbound. However insane and fetishistic this religion of rules may seem, perhaps it would seem less fetishistic if we recalled that experience of lawlessness, of unbounded and unregulated power, that preceded it.

But today, in the context of a Salaita boycott, I want to explore a different explanation. Perhaps this religion of rules has something to do with the quotidian reality of organizing a collective mode of life. Whenever we initiate a collective course of action—be it for the sake of something as grand as politics or religion or as pedestrian as a road trip—we run into unforeseen circumstances, bumps in the road that force us to rethink the course we have set out on. We declare something as seemingly simple and straightforward as a boycott of UIUC, and suddenly there are a thousand details and unanticipated contingencies that have to be dealt with. Am I allowed to submit an article to a journal that is connected to the UIUC? Can you speak off-campus? What if she pays her own way and refuses to accept any honorarium? Is he allowed to participate in a conference that is being held on another campus but is partially funded by the UIUC? And on and on.

Think about a strike. As anyone who has participated in a strike will tell you, there are all sorts of questions that come up in the course of a strike as to what constitutes strike-breaking. Teachers, for example, have to run a minefield of individualized requests and extracurricular circumstances—the graduating student who needs a letter of recommendation, the test-taking junior who was supposed to receive special evening tutoring, and so on—that complicate the simple injunction to stop work. Or the strikers’ themselves may have individualized needs and requests. Strike leaders have to navigate these requests, maintaining solidarity and discipline while making allowances for these complicating factors of everyday life.

I am just speculating here, but I wonder if something similar is not at play in the development of the Judaic code. From the very beginning, Jews inherited a way of life, replete with ancient and simple rules that possessed, initially, an easy intelligibility and easy applicability, but which, with time, had to be adapted—perhaps even at the moment of their promulgation—to unforeseen circumstances. And because of that memory of bondage, where lawlessness seemed akin to slavishness, the Jews wanted to act rule-fully in the face of these unforeseen circumstances. So they proclaimed new rules. And then new rules. To avoid the very arbitrariness—that feeling of making it up on the fly, which can threaten solidarity—that so often confronts the organizers of any large-scale action.

That is how, maybe, we’ve made our religion—like our boycott—kosher.

New Questions Raised About Who Exactly Made the Decision to Fire Salaita

There’s an excellent piece this morning in the News-Gazette, the newspaper of Urbana-Champaign, raising serious questions about who made the decision to fire Steven Salaita and when/how it was made. Initially, the paper reports, after Salaita’s tweets were publicly criticized in the right-wing media, Chancellor Wise and the UIUC publicly stood by him.

Then, on July 24, 2014, the Board of Trustees met in closed session with Wise, and “something changed,” as Salaita’s attorney, Anand Swaminathan, puts it:

It’s very clear that the university administration understood all the way through, at least through July 24, that they had obligations and commitments to Professor Salaita. Something changed in their attitude since then.

The News-Gazette provides this handy timeline, suggesting that the Board of Trustees may have played more of a role in this decision than we originally realized:

— On July 23, at 5:49 p.m., UI spokeswoman Robin Kaler laid out a plan for Wise: The chancellor would instruct American Indian Studies department head Robert Warrior to contact Salaita and express Wise’s dissatisfaction and send him the UI’s ethics code. Warrior would instruct Salaita to meet with Wise when he arrived on campus in the fall, and she would convey her unhappiness with him. But Salaita was still expected to be approved by the board.

— The next morning, July 24, at 5:44 a.m., Provost Ilesanmi Adesida referred to Salaita’s contract being “delayed” and noted that he had been offered the job almost a year earlier.

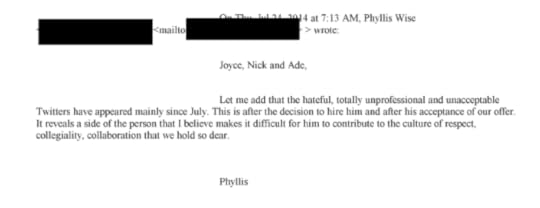

— At 7:13 a.m., Wise criticized Salaita’s Twitter comments as “hateful, totally unprofessional and unacceptable” and said they had appeared only “after the decision to hire him and after his acceptance of our offer. It reveals a side of the person that I believe makes it difficult for him to contribute to the culture of respect, collegiality, collaboration that we hold so dear.”

— At 7:25 a.m., going into the executive session, Wise asked Kaler to draft a joint statement with Adesida about how Salaita’s behavior was inappropriate, but she did not say his appointment would not be forwarded to the board.

— The first mention of that occurred after the meeting, at 1:55 p.m. When Kaler asked for an update, Wise said: “Too complicated to do in email. But they will be considering carefully whether to approve in September. Definitely not a given.”

Emails released yesterday also show Wise expressing deep dissatisfaction with the notion—advanced by Chris Kennedy, Chair of the Board of Trustees—that she was the sole or main decision-maker. Wise writes on December 14, 2014:

What angers me about this report is that they believe that I made the decision and that the BOT followed my recommendation. That is just plain not true. I have been carrying the water since (public relations firm) Edelman said that we have to stay as one voice. I don’t think I can do that any longer. I am going to talk with (university counsel) Scott (Rice) about setting the record straight.

A lot of this timeline of the switch in Wise’s tune is in keeping with what I observed last September. Though I was more focused on the question of donor influence than the Board of Trustees, and I treat the Board of Trustees as more reactive than it seems they were, my timing of the decision also places critical emphasis on that July 24 date.

When the Salaita story first broke in the local press, Associate Chancellor for Public Affairs Robin Kaler said, “Faculty have a wide range of scholarly and political views, and we recognize the freedom-of-speech rights of all of our employees.” That was on July 21. The UIUC documents reveal that not only was Chancellor Wise apprised of that statement minutes after it was emailed to the media, but that she also wrote back to Kaler: “I have received several emails. Do you want me to use this response or to forward these to you?” (p. 101) In other words, this was not the rogue statement of a low-level spokesperson; it reflected Wise’s own views, including the view that Salaita was already a university employee. Even though Wise already had been informed of Salaita’s tweets.

In the days following this forthright defense of Salaita, the Chancellor and her associates begin to back-pedal. Around July 23, Wise starts reaching out to select alumni, trying to arrange phone calls (and in one instance, struggling to rearrange her travel schedule just so she can meet one alum in person [pp. 78-94]). To another such alum, she writes, “Let me say that I just recently learned about Steven Salaita’s background, beyond his academic history, and am learning more now.” (p. 293) That “beyond his academic history” is going to get Wise in trouble on academic freedom grounds.

In the background of this change of tune are the donors and the university’s fundraising and development people. In a July 24 email to Dan Peterson, Leanne Barnhart, and Travis Michael Smith (all part of the UIUC money machine), Wise reports about a meeting she has had with what appears to be a big donor. In Wise’s words:

He said that he knows [REDACTED] and [REDACTED] well and both have less loyalty for Illinois because of their perception of anti-Semitism. He gave me a two-pager filled with information on Steven Salaita and said how we handle this situation will be very telling. (p. 206)

Once Wise and her team start back-tracking, the trustees are brought into the picture.

The only wrinkle here, as I say, is that the Board of Trustees may have played more of an initiating role than I initially realized. As the News-Gazette reports:

Emails released by the University of Illinois on Friday may raise new questions about the decision not to hire Steven Salaita, with Chancellor Phyllis Wise saying at one point she was tired of “carrying the water” for the controversial move.

Wise has been the focal point of the faculty uproar about the decision to revoke Salaita’s job offer after his harsh, profanity-laden tweets about Israel last summer, just days before he was to begin teaching. But comments in Wise’s emails indicate that former Board Chairman Chris Kennedy may have played a bigger role than previously indicated.

Though there again, as the controversy began to explode throughout August, Wise began to disavow some of her ownership over the decision. As I reported on September 5, 2014:

And then she drops this bombshell: that in dehiring Steven Salaita, Wise was expressing “the sentiment of the Board of Trustees, it was not mine.”

So not only did her decision not reflect any of the academic voices on campus; it didn’t even reflect her own opinion.

August 7, 2015

Chancellor Wise Forced To Release Emails From Personal Account

The Chicago Tribune reports today that UIUC was forced to release 1100 pages of emails from Chancellor Wise, many of them from her personal email account, many of them related to the Steven Salaita case. According to a statement from UIUC:

A desire to maintain confidentiality on certain sensitive University-related topics was one reason personal email accounts were used to communicate about these topics. Some emails suggested that individuals were encouraged to use personal email accounts for communicating on such topics.

The statement may be referring to this email from Wise, on September 18, 2014.

Equally interesting is this one from July 24, 2014. Note that statement by Wise re “after the decision to hire him and after his acceptance of our offer.”

August 6, 2015

On the One-Year Anniversary of the Salaita Story, Some Good News

Big news out of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign today.

First, a federal judge firmly rejected UIUC’s argument that it never hired Steven Salaita because the Board of Trustees hadn’t yet given its final seal of approval at the time of his firing last year. According to Judge Henry Leinenweber of the US District Court for the Northern District of Illinois (a Reagan appointee):

If the court accepted the university’s argument, the entire American academic hiring process as it now operates would cease to exist, because no professor would resign a tenure position, move states, and start teaching at a new college based on an ‘offer’ that was absolutely meaningless until after the semester already started.

As the Chronicle of Higher Education goes onto report:

If the university truly regarded such job contracts as hinging on board approval, he said, it would have the board vote on them much earlier in the hiring process, before paying a prospective faculty member’s moving expenses and offering that professor an office and classes. “Simply put, the university cannot argue with a straight face that it engaged in all these actions in the absence of any obligation or agreement,” he said.

The university’s board actually might have undermined itself legally in deciding to hold a formal vote on Mr. Salaita’s employment after Phyllis M. Wise, the campus’s chancellor,attempted to rescind the job by not forwarding it for board approval, the ruling indicated. If the university had not made some sort of offer to Mr. Salaita, the judge asked, “why hold a vote at all?”

Based heavily upon his determination that such an agreement existed, Judge Leinenweber said Mr. Salaita can proceed in trying to prove that university administrators and board members conspired to breach his contract, violate his free-speech rights under the First Amendment, and deny him academic due process.

Last summer, at just about this time, many defenders of Chancellor Wise’s decision to fire Salaita, including many readers of and commenters on this blog, tried to make the case that the UIUC proceeded to make in federal court and that has now been firmly rejected by that court. Indeed, Judge Leinenweber makes many of the same arguments against UIUC’s claim that many of us made against that claim last summer (see especially, pp. 13-19). While it was depressing and exhausting to have to make these arguments over and over again—arguments that were plain as day to most of us in academia—it’s nice to see them vindicated in court.

Second, Chancellor Wise resigned today. With, to my mind, an unprecedented statement admitting to the costs this controversy has imposed upon her and her administration.

External issues have arisen over the past year that have distracted us from the important tasks at hand. I have concluded that these issues are diverting much needed energy and attention from our goals. I therefore believe the time is right for me to step aside.

While Wise was battling critics on an array of issues, the Chicago Tribune reports that it was the Salaita case that was truly taking the greatest toll.

But the harshest criticism against Wise focused on the decision last summer to withdraw a job offer to professor Steven Salaita after he made a series of critical and profane comments about Israel on social media. U. of I. rescinded Salaita’s offer for a tenured faculty position in the American Indian studies department weeks before he was scheduled to start teaching.

That decision led to much fallout, including a recent censure by the American Association of University Professors, a prominent professors group, which said U. of I. violated the principles of academic freedom. More than a dozen U. of I. academic departments voted no confidence in Wise’s leadership, and faculty across the country have boycotted the campus and canceled events there. Salaita has filed a federal lawsuit alleging breach of contract and violation of his free speech rights.

Those controversies apparently came to a head this week, and Wise submitted a one-sentence resignation letter Thursday.

…

“It is the right thing for her to step down. I wish that I could be more supportive of her, but unfortunately during the last year, she has made so many missteps that have cost the university so many hundreds of thousands of dollars in legal fees,” said U. of I. religion professor Bruce Rosenstock, president of the Campus Faculty Association, a faculty advocacy group.

It was exactly one year ago today that the Salaita story broke nationally. It’s been a grueling year for Steven, which he discusses in Uncivil Rites, a terrific little book that I read and blurbed not long ago and that I heartily recommend to all of you. But on this, the one-year anniversary of the breaking of his story, I hope he can take some solace in these bits of good news.

Update (11:15 pm)

After reading Leinenweber’s opinion, Brian Leiter affirms a point I’ve long been making about the threat of discovery:

Thus, the court asked the question: if the facts are as Salaita alleges, does he have a valid breach of contract claim, and the court gave that a resoundingly affirmative answer (coming pretty close to ridiculing the university’s position that there wasn’t really a contract). The breach of contract and the First Amendment claims are Salaita’s most potent in terms of damages. It was obviously agreed in advance that Chancellor Wise would step down given an adverse decision, presumably because the University knows that the outrageousness of her conduct will be exposed to view once discovery begins and presumably also thinking that it will be easier to settle with Salaita once they are rid of the University official who said, “We will not hire him.” My bet is that, in order to block discovery, which would throw open to public view the bad behavior of many actors behind the scenes, and in order to avoid the damages attached to losing the breach of contract and First Amendment claims (which they would almost certainly lose, and for which the damages could easily amount to compensation for his entire career, i.e., 35 years of salary and benefits, plus additional damages for the constitutional claims), the University will now try to reach a settlement in which he is reinstated (subject to some face-saving terms for the University, like Salaita promising not to scare students in the classroom), and compensation is limited to damages for the last year plus his attorney fees. This is a very good day for tenure, for contracts, and for free speech.

August 2, 2015

Capitalism Can’t Remember Where I Left My Keys

My column in Salon this morning is about left v. right and why time—history, tradition, past, present, and future—is not what divides left from right. With the help of two new books by Steve Fraser and Kristin Ross, I discuss the bloody civil wars of the Gilded Age, the Paris Commune, Marx’s archaism, and how the memory of pre-capitalist society can fire the anticipation of a post-capitalist society.

Ever since Edmund Burke, founder of the conservative tradition, declared, “The very idea of the fabrication of a new government, is enough to fill us with disgust and horror,” pundits and scholars have divided the political world along the axis of time. The left is the party of the future; the right, the party of the past. Liberals believe in progress and the new; conservatives, in tradition and the old. Hope versus history, morrow versus memory, utopia versus reality: these are the stuff of our great debates.

In “The Reactionary Mind,” I argued that this view of the political divide is incorrect, at least as it pertains to the right. Beginning with Burke, conservatives have been less committed to tradition or the past than to a hierarchical vision of society. In Burke’s case, it was aristocrats over commoners; in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, it would be masters over slaves, employers over employees, husbands and men over women and wives. And so it remains: the most consistent feature of contemporary American conservatism is the GOP’s war on reproductive freedom and worker rights.

…

But if the right’s window does not open onto the past, must the left’s open onto the future? Not necessarily, claim two fascinating new books: Steve Fraser’s “The Age of Acquiescence: The Life and Death of American Resistance to Organized Wealth and Power” and Kristin Ross’s “Communal Luxury: The Political Imaginary of the Paris Commune.” When it comes to past and future, they show, the left can be as ambidextrous as the right. What’s more, it may be the left’s ability to look backward while marching forward that explains its most potent moments of power and possibility.

…

What Fraser shows, with vivid set pieces drawn from the nation’s most violent battlefields, is that far from presenting itself as the enemy, the past was viewed by workers and farmers as a resource and an ally. In part because the capitalist right so heartily embraced the rhetoric of progress and the future (no one, it seems, was content with the present). But more than that, historical memory enabled workers and farmers to see beyond the horizon of the capitalist present, to know, in their bones, what Marx was constantly struggling to imprint upon the mind of the left: that capitalism was but one mode of economic life, that its existence was contingent and historical rather than natural and eternal, and that because there was a past in which it did not exist there might be a future when it would cease to exist. Like the nation, capitalism rests upon repeated acts of forgetting; a robust anti-capitalism asks us to remember.

…

In his “Reflections on the Revolution in France,” Burke is supposed to have given voice to the conservative dispensation by describing society as “a partnership not only between those who are living, but between those who are living, those who are dead, and those who are to be born.” Yet who in and around the Commune had greater sensitivity to the delicate and mutual dependencies of past and future: The anarchist Kropotkin, who spent an entire week in prison tapping out the history of the Commune to his young neighbor in the next cell, lest it be forgotten? The Communard geographer Élisée Reclus, who called for solidarity “between those who travel through the conscious arena and those who are longer here”? Or the reactionaries in charge of the French regime, who spent the better part of the 1870s forbidding anyone who managed to survive the Commune from carving any mention of it on their gravestones?

July 31, 2015

The Bullshit Beyond Ideology

I have a great impatience with people who—whether for normative or empirical reasons (the second is often driven by the first)—claim that we need to dispense with terms like “left” and “right.” The world is too complicated, they say, for such simpleminded categories. We need a Third Way, they say (and have said since the French Revolution). My ideology is “neither Right Nor Left,” they say, which is what fascists so often said of themselves. I am beyond ideology.

Some of the reasons for my impatience were laid out by the Italian political theorist Noberto Bobbio in a short masterpiece he penned in the last decade of his life: Left and Right: The Significance of a Political Distinction. But another reason has to do with the bad faith—and political instrumentalism—of the ideologues who so often make that move.

As did Sidney Hook at the first meeting of the Congress of Cultural Freedom in Berlin in 1950. As quoted in the Times (according to Christopher Lasch), Hook anticipated an “era when references to ‘right,’ ‘left,’ and ‘center’ will vanish from common usage as meaningless.” This, at a conference where, according to the Times, it was declared by everyone that “the time is at hand for a decision as between the East and West.”

Corey Robin's Blog

- Corey Robin's profile

- 163 followers