Corey Robin's Blog, page 47

April 29, 2016

Neoliberalism: A Quick Follow-up

My post on neoliberalism is getting a fair amount of attention on social media. Jonathan Chait, whose original tweet prompted the post, responded to it with a series of four tweets:

The four tweets are even odder than the original tweet.

First, Chait claims I confuse two different things: Charles Peters-style neoliberalism and “the Marxist epithet for open capitalist economies.” Well, no, I don’t confuse those things at all. I quite clearly state at the outset of my post that neoliberalism has a great many meanings—one of which is the epithet that leftists hurl against people like Chait—but that there was a moment in American history when a group of political and intellectual actors, under the aegis of Peters, took on the name “neoliberal” for themselves. That’s who I was talking about in my post.

Second, contrary to Chait, Peters did not in fact invent the term “neoliberal” or “neoliberalism” in 1983. The term was coined by a group of mostly conservative free market intellectuals, meeting in Paris in 1938 at the Colloque Walter Lippmann, in order to counter the rise of democratic socialism and welfare-state liberalism in Western Europe and the United States. Eventually, that group would coalesce after World War II as the Mont Pelerin Society, with Friedrich Hayek at the intellectual helm.

Third, the reason that earlier coinage matters, and isn’t just a point of scholarly pedantry, is that while some scholars will challenge what I’m about to say, the program that that original group of neoliberals set out at Mont Pelerin does in fact bear a resemblance to the word “neoliberalism” that often gets bandied around by the left today. Insofar as that was a program to rollback the welfare state and social democracy, to revalorize capital and the capitalist as a moral good, to proclaim the ideological supremacy of the market over the state (the practice is more complicated), “neoliberal” is in fact a useful term to describe a political program that has gained increasing traction around the globe in the last half-century.

It’s important to distinguish neoliberalism in this sense—that is, neoliberalism as a political program—from neoliberalism as a system of political economy. Scholars and activists on the left disagree, fundamentally, about the latter, with some claiming that what we call neoliberalism as a form of political economy is merely capitalism. I’m deliberately side-stepping that debate in order to focus on neoliberalism as a political and ideological program.

(It’s also important to acknowledge that one of the reasons the term “neoliberalism” can be confusing is that outside of the United States, particularly in Europe, liberal has often meant support for free markets and a critique of the welfare state and social democracy. Inside the United States, liberal, at least throughout most of the 20th century, meant support for the welfare state and state intervention in the economy. Get into a discussion about neoliberalism on Twitter, and you inevitably find yourself crashing on a beachhead of this confusion. Personally, I think it’s about as interesting and relevant as that Founding Fathers fanboy who’ll periodically pop up in a discussion thread claiming that the United States is a republic, not a democracy. I merely note it here in order to acknowledge the point and move on.)

Fourth, insofar as Peters and his group of neoliberals in the United States declared the fundamentals of their political program to be: a) opposition to unions; b) opposition to big government (except for the military); and c) support for big business, I find the term “neoliberal” to be useful not only for describing Peters and his crew but also for relating that crew to the overall program of neoliberalism, which I noted in point 3 above, and which today characterizes a good part of the Democratic Party. In other words, while I deliberately did not conflate Peters’s neoliberalism with the leftist epithet for Democrats that Chait objects to, there is in fact a relationship between Peters’s neoliberalism and today’s Democrats (more on this below).

(Incidentally, if you think I was being unfair to Peters-style neoliberalism, I urge you to read this interview Peters gave to Ezra Klein back in 2007, where he reiterates the basics of the program as I outline them here and in my post, and says, forthrightly, “I think in many, many areas, the neoliberals, in effect, won.” That is, they changed liberalism (again, more on this below.) The only plank of the original program that Peters thinks needs to be pursued more forcefully is crushing teachers’ unions and means testing mass entitlement programs like Social Security and Medicare.)

Fifth, the inspiration for my post, as I said, was a tweet from Chait in which he takes particular delight in professing an impish disbelief in the term “neoliberal,” as if it were a made-up word of paranoid leftists used to abuse liberals like Chait. And in this series of tweets, he doubles down on that disbelief, claiming that Peters-style neoliberalism had at best a shadowy half-life in the magazine world; it “barely existed,” tweets Chait, “then died.” No one’s used the word in ages.

In my post, I claimed that one of the reasons contemporary writers like Chait write from this state of amnesiac euphoria—where they fail to recognize the distance they’ve traveled from the midcentury world of labor liberalism—is that they’ve so completely absorbed the neoliberal critique, almost unconsciously, that they can’t even remember a time when liberals thought otherwise.

It turns out that that wasn’t quite fair. There was a journalist back in 2013 who recognized precisely what I was talking about. Here’s what this writer said about the impact of neoliberal magazines on traditional Democratic Party liberalism (h/t the guy whose Twitter handle is HTML Mencken):

Those magazines once critiqued Democrats from the right, advocating a policy loosely called “neoliberalism,” and now stand in general ideological concord.

Why? I’d say it’s because the neoliberal project succeeded in weaning the Democrats of the wrong turn they took during the 1960s and 1970s. The Democrats under Bill Clinton — and Obama, whose domestic policy is crafted almost entirely by Clinton veterans — has internalized the neoliberal critique.

The name of that writer was Jonathan Chait.

Update (6:30 pm)

I was just re-reading the introduction to The Road from Mont Pelerin, which I link to above (and which I highly recommend), and the authors claim that the first usage of “neoliberal” along the lines of what I mention above was actually by a Swiss economist in 1925 (there was actually a 1898 usage as well, but they claim it was rather different). In the 1930s, neoliberal took off as a term, particularly in France, culminating in that 1938 meeting that I mention above. As the Cornell historian Larry Glickman pointed out to me in a Facebook thread, the term neoliberal was also used by anti-New Dealers in the United States in the 1930s, only their point was to stress that FDR had transformed liberalism from its 19th century understanding (an understanding that was much more sympathetic to markets) into a “neoliberalism” that was too critical of the market and indulgent of the state’s intervention. According to the authors of the introduction to The Road to Mont Pelerin, Frank Knight, a close associate of Milton Friedman and George Stigler at the University of Chicago, wrote an essay criticizing the New Deal in the 1930s along these lines.

Update (9 pm)

Jonathan Chait has a longer response on his Facebook page. It’s kind of a non-response response that I’m posting here merely for the sake of, whatever. More amusing to me is how Damon Linker—think of him as Mark Lilla’s Mini-Me—shows up faithfully in the comments section, like one of the Super Friends in response to a summons from the Bat Signal. Anyway, here’s Chait:

I wrote a tweet a few days ago complaining about the use of “neoliberal” as a term of abuse on the left against liberals. “What if every use of ‘neoliberal’ was replaced with, simply, ‘liberal’? Would any non-propagandistic meaning be lost?,” I wrote. My meaning is that no current group of people defines itself as “neoliberal.” The term is simply used by leftists, usually of the Marxist and/or socialist variety, to denigrate liberals.

Corey Robin has fired back in two posts. None of them, however, answer my question. The first post focuses on a small sect on intellectuals called “neoliberals,” a term that was invented by Washington Monthly editor Charles Peters in the early 1980s. Neoliberalism was not really an ideology (though Peters sort-of tried to flesh it out into it) but a collection of Peters hobbyhorses that mostly revolved around streamlining the functioning of the federal government. Some writers tried to take other aspects of moderate liberalism and call it “neoliberalism.” But the main point is that the label died years ago, and nobody uses it any more as a form of self-identification. Importantly, even though elements of its ideas made their way into the Democratic Party, the label also never attracted any real following in the Democratic mainstream. Bill Clinton, probably the closest thing to an ally neoliberals would have found, called himself a “New Democrat.”

I was never a fan of the “neoliberal” label, for reasons that were persuasively explained to me by Paul Starr when I worked at the American Prospect out of college. Neoliberal writers called their farther-left counterparts “paleoliberals.” As Starr told me, the terms were an attempt to win an argument by using an epithet — “neo” implying that its side had already won the future, and “paleo” implying the other was consigned to the past.

That debate was consigned to a handful of writers (most of them baby boomer men from the Washington Monthly and the New Republic of the 1980s) who passed from the scene or lost interest in it. Modern liberals are all just liberals, though of course we have internal differences. Robin does not refute my point that no current faction uses the label to describe itself. Instead, in his follow-up post, he notes that some right-wingers also used the phrase in the 1930s to oppose the New Deal. To a leftists like Robin, this proves that the ideology is all one and the same. “Insofar as that was a program to rollback the welfare state and social democracy, to revalorize capital and the capitalist as a moral good, to proclaim the ideological supremacy of the market over the state (the practice is more complicated), “neoliberal” is in fact a useful term to describe a political program that has gained increasing traction around the globe in the last half-century,” he writes.

And, yes, if you believe that Charles Peters took his inspiration from the anti-New Deal right, and the modern Democratic Party took its inspiration from Peters, then that is an important connection. But the first connection is preposterous. Peters was a New Dealer who worshipped Roosevelt. He did not see himself as an heir to the 1930s Old Right. Peters was much less a statist than Robin, but clearly belonged on the left half of the political spectrum throughout his career.

Of course, it is convenient for Robin to lump the center-left, with figures like Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton, in with the far right. This was all Robin’s ideological foes, those who stand for somewhat higher taxes and more generous social spending and decarbonization and regulation of finance can be lumped together with the conservatives who wish to roll all those things back.

So obviously Robin and many of his allies will continue to use the term “neoliberal” to describe liberals, because it serves an important propagandistic function for them. But it will continue to be used only by those people to describe current politics, and by nobody else, because it is not a neutral term or a fair-minded attempt to describe the world.

April 27, 2016

When Neoliberalism Was Young: A Lookback on Clintonism before Clinton

Yesterday, New York Magazine’s Jonathan Chait tweeted this:

What if every use of “neoliberal” was replaced with, simply, “liberal”? Would any non-propagandistic meaning be lost?

— Jonathan Chait (@jonathanchait) April 26, 2016

It was an odd tweet.

On the one hand, Chait was probably just voicing his disgruntlement with an epithet that leftists and Sanders liberals often hurl against Clinton liberals like Chait.

On the other hand, there was a time, not so long ago, when journalists like Chait would have proudly owned the term neoliberal as an apt description of their beliefs. It was The New Republic, after all, the magazine where Chait made his name, that, along with The Washington Monthly, first provided neoliberalism with a home and a face.

Now, neoliberalism, of course, can mean a great many things, many of them associated with the right. But one of its meanings—arguably, in the United States, the most historically accurate—is the name that a small group of journalists, intellectuals, and politicians on the left gave to themselves in the late 1970s in order to register their distance from the traditional liberalism of the New Deal and the Great Society. The original neoliberals included, among others, Michael Kinsley, Charles Peters, James Fallows, Nicholas Lemann, Bill Bradley, Bruce Babbitt, Gary Hart, and Paul Tsongas. Sometimes called “Atari Democrats,” these were the men—and they were almost all men—who helped to remake American liberalism into neoliberalism, culminating in the election of Bill Clinton in 1992.

These were the men who made Jonathan Chait what he is today. Chait, after all, would recoil in horror at the policies and programs of mid-century liberals like Walter Reuther or John Kenneth Galbraith or even Arthur Schlesinger, who claimed that “class conflict is essential if freedom is to be preserved, because it is the only barrier against class domination.” We know this because he recoils in horror today he so resolutely opposes the more tepid versions of that liberalism that we see in the Sanders campaign.

It’s precisely the distance between that lost world of 20th century American labor liberalism and contemporary liberals like Chait that the phrase “neoliberalism” is meant, in part, to register.

We can see that distance first declared, and declared most clearly, in Charles Peters’s famous “A Neoliberal’s Manifesto,” which Tim Barker reminded me of last night. Peters was the founder and editor of The Washington Monthly, and in many ways the éminence grise of the neoliberal movement. In re-reading Peters’s manifesto—I remember reading it in high school; that was the kind of thing a certain kind of nerdy liberal-ish sophomore might do—I’m struck by how much it sets out the lineaments of Chait-style thinking today.

The basic orientation is announced in the opening paragraph:

We still believe in liberty and justice for all, in mercy for the afflicted and help for the down and out. But we no longer automatically favor unions and big government or oppose the military and big business. Indeed, in our search for solutions that work, we have to distrust all automatic responses, liberal or conservative.

Note the disavowal of all conventional ideologies and beliefs, the affirmation of an open-minded pragmatism guided solely by a bracing commitment to what works. It’s a leitmotif of the entire manifesto: Everyone else is blinded by their emotional attachments to the ideas of the past. We, the heroic few, are willing to look upon reality as it is, to take up solutions from any side of the political spectrum, to disavow anything that smacks of ideological rigidity or partisan tribalism.

That Peters wound up embracing solutions in the piece that put him comfortably within the camp of GOP conservatism (he even makes a sop to school prayer) never seemed to disturb his serenity as a self-identified iconoclast. That was part of the neoliberal esprit de corps: a self-styled philosophical promiscuity married to a fairly conventional ideological fidelity.

Listen to how former New Republic owner Marty Peretz described (h/t Tim Barker) that ethos in his lookback on The New Republic of the 1970s and 1980s:

My then-wife and I bought the New Republic in 1974. I was at the time a junior faculty member at Harvard, and I installed a former student, Michael Kinsley, as its editor. We put out a magazine that was intellectually daring, I like to think, and politically controversial.

We were for the Contras in Nicaragua; wary of affirmative action; for military intervention in Bosnia, Rwanda and Darfur; alarmed about the decline of the family. The New Republic was also an early proponent of gay rights. We were neoliberals. We were also Zionists, and it was our defense of the Jewish state that put us outside the comfort zone of modern progressive politics.

Except for gay rights and one or two items in that grab bag of foreign interventions, what is Peretz saying here beyond the fact that his politics consisted mainly of supporting various planks from the Republican Party platform? That was the intellectual daring, apparently.

Returning to that first paragraph of Peters’s piece, we find the basic positions of the neoliberal persuasion: opposition to unions and big government, support for the military and big business.

Above all, neoliberals loathed unions, especially teachers unions. They still do, except insofar as they’re useful funding devices for the contemporary Democratic Party.

But reading Peters, it’s clear that unions were, from the very beginning, the main target. The problems with unions were many: they protected their members’s interests (no mention of how important unions were to getting and protecting Social Security and Medicare); they drove up costs, both in the private and the public sector; they defended lazy, incompetent workers (“We want a government that can fire people who can’t or won’t do the job.”)

Against unions, or conventional unions, Peters held out the promise of ESOPs, where workers would forgo higher wages and benefits in return for stock options and ownership. He happily pointed to the example of Weirton Steel:

…where the workers accepted a 32 percent wage cut to keep their company alive. They will not be suckers because they will own the plant and share in the future profits their sacrifice makes possible. It’s better for a worker to keep a job by accepting $12 an hour than to lose it by insisting on $19.

(Sadly, within two decades, Weirton Steel was dead, and with it, those future profits and wages for which those workers had sacrificed in the early 1980s.)

But above all, Peters and other neoliberals saw unions as the instruments of the most vile subjugation of the most downtrodden members of society:

A poor black child might have a better chance of escaping the ghetto if we fired his incompetent middle-class teacher.

…

The urban public schools have in fact become the principal instrument of class oppression in America, keeping the lower orders in their place while the upper class sends its children to private schools.

And here we see in utero how the neoliberal argument works its magic on the left.

On the one hand, Peters showed how much the neoliberal was indebted to the Great Society ethos of the 1960s. That ethos was a departure from the New Deal insofar as it took its stand with the most desperate and the most needy, whom it set apart from the rest of society. Michael Harrington’s The Other America, for example, treated the poor not as a central part of the political economy, as the New Deal did. The poor were superfluous to that economy: there was America, which was middle-class and mainstream; there was the “other,” which was poor and marginal. The Great Society declared a War on Poverty, which was thought to be a project different from from managing and regulating the economy.

On the other hand, Peters showed how potent, and potently disabling, that kind of thinking could be. In the hands of neoliberalism, it became fashionable to pit the interests of the poor not against the power of the wealthy but against the working class that had been made into a middle class by America’s unions. (We still see that kind of talk among today’s Democrats, particularly in debates around free trade, where it is always the unionized worker—never the well paid journalist or economist or corporate CEO—who is expected to make sacrifices on behalf of the global poor. Or among Hillary Clinton supporters, who leverage the interests of African American voters against the interests of white working-class voters, but never against the interests of capital.)

Teachers’ unions in the inner cities were ground zero of the neoliberal obsession. But it wasn’t just teachers’ unions. It was all unions:

In both the public and private sector, unions were seeking and getting wage increases that had the effect of reducing or eliminating employment opportunities for people who were trying to get a foot on the first run of the ladder.

And it wasn’t just unions that were a problem. It was big-government liberalism as a whole:

Too many liberals…refused to criticize their friends in the industrial unions and the civil service who were pulling up the ladder. Thus liberalism was becoming a movement of those who had arrived, who cared more about preserving and expanding their own gains than about helping those in need.

That government jobs are critical for women and African Americans—as Annie Lowrey shows in a excellent recent piece—has long been known in traditional liberal and labor circles. That that fact has only recently been registered among journalists—who, even when they take the long view, focus almost exclusively, as Lowrey does, on the role of GOP governors in the aughts rather than on these long-term shifts in Democratic Party thinking—tells us something about the break between liberalism and neoliberalism that Chait believes is so fanciful.

Oddly, as soon as Peters was done attacking unions and civil-service jobs for doling out benefits to the few—ignoring all the women and people of color who were increasingly reliant on these instruments for their own advance—he turned around and attacked programs like Social Security and Medicare for doing precisely the opposite: protecting everyone.

Take Social Security. The original purpose was to protect the elderly from need. But, in order to secure and maintain the widest possible support, benefits were paid to rich and poor alike. The catch, of course, is that a lot of money is wasted on people who don’t need it.

…

Another way the practical and the idealistic merge in neoliberal thinking in is our attitude toward income maintenance programs like Social Security, welfare, veterans’ pensions, and unemployment compensation. We want to eliminate duplication and apply a means test to these programs. They would all become one insurance program against need.

As a practical matter, the country can’t afford to spend money on people who don’t need it—my aunt who uses her Social Security check to go to Europe or your brother-in-law who uses his unemployment compensation to finance a trip to Florida. And as liberal idealists, we don’t think the well-off should be getting money from these programs anyway—every cent we can afford should go to helping those really in need.

Kind of like Hillary Clinton criticizing Bernie Sanders for supporting free college education for all on the grounds that Donald Trump’s kids shouldn’t get their education paid for? (And let’s not forget that as recently as the last presidential campaign, the Democratic candidate was more than willing to trumpet his credentials as a cutter of Social Security and Medicare, though thankfully he never entertained the idea of turning them into means-tested programs.)

It’s difficult to make sense of what truly drives this contradiction, whereby one liberalism is criticized for supporting only one segment of the population while another liberalism is criticized for supporting all segments, including the poor.

It could be as simple as the belief that government should work on behalf of only the truly disadvantaged, leaving everyone else to the hands of the market. That that turned out to be a disaster for the truly disadvantaged—with no one besides themselves to speak up on behalf of anti-poverty programs, those programs proved all too easy to eliminate, not by a Republican but by a Democrat—seems not to have much troubled the sleep of neoliberalism. Indeed, in the current election, it is Hillary Clinton’s support for the 1994 crime bill rather than the 1996 welfare reform bill that has gotten the most attention, even though she proudly stated in her memoir that she not only supported the 1996 bill but rounded up votes for it.

Or perhaps it’s that neoliberals of the left, like their counterparts on the right, simply came to believe that the market was for winners, government for losers. Only the poor needed government; everyone else was made for capitalism. “Risk is indeed the essence of the movement,” declared Peters of his merry band of neoliberal men, and though he had something different in mind when he said that, it’s clear from the rest of his manifesto that the risk-taking entrepreneur really was what made his and his friends’ hearts beat fastest.

Our hero is the risk-taking entrepreneur who creates new jobs and better products. “Americans,” says Bill Bradley, “have to begin to treat risk more as an opportunity and not as a threat.”

Whatever the explanation for this attitude toward government and the poor, it’s clear that we’re still living in the world the neoliberals made.

When Clinton’s main line of attack against Sanders is that his proposals would increase the size of the federal government by 40%, when her hawkishness remains an unapologetic part of her campaign, when unions barely register except as an ATM for the Democratic Party, and Wall Street firmly declares itself to be in her camp, we can hear that opening call of Peters—”But we no longer automatically favor unions and big government or oppose the military and big business”—shorn of all awkward hesitation and convoluted formulations, articulated instead in the forthright syntax of common sense and everyday truth.

Perhaps that is why Jonathan Chait cannot tell the difference between liberalism and neoliberalism.

April 25, 2016

John Palattella: A Writer’s Editor

Last week, an announcement went out from The Nation that, while barely mentioned in the media-obsessed world of the Internet, echoed throughout my little corner of the Internet. John Palattella will be stepping down from his position as Literary Editor of The Nation in September, transitioning to a new role as an Editor at Large at the magazine.

For the last nine years, John has been my editor at The Nation. I wrote six pieces for him. That may not seem like a lot, but these were lengthy essays, some 42,000 words in total, several of them taking me almost a year to write. That’s partially a reflection of my dilatory writing habits, but it also tells you something about John’s willingness to invest in a writer and a piece.

John is not just an editor. Nor is he just an editor of one of the best literary reviews in the country. John is a writer’s editor.

Over the years, I’ve worked with more editors than I can remember. A few were stellar: Alex Star at Lingua Franca (now, at Farrar, Straus and Giroux) was one; an editor at the New York Times oped page whose name I can never recall is another. John, however, is in a class by himself.

Looking over the literally hundreds of emails he and I exchanged about my pieces—from the opening “Hey, Corey, would you be interested” to the final “This is the last change we can make”—I see the presence of an editor unlike any other I’ve worked with.

For starters, John knows his writers. I turn down many assignments, for reasons of time or lack of interest. But I don’t think I’ve ever said no to John. Even when I didn’t have time, I made the time. Not because I felt loyal to him, though I do, but because John knows how to pique my interest and how to avoid anything that would feel like a chore.

Every time we worked together on a piece, it felt as if an ideal roommate, unobtrusive but scrupulous and attentive, had moved into the apartment. An alter-ego who cared about only one thing: the work (and making it better). But without that hectoring, punishing, censorious inner voice that so often accompanies one’s best efforts.

John does more than read your prose carefully; he gets right in there with you, inhabiting the space of your argument (one of John’s writers told me that when she was writing a piece about a novelist, John actually read or re-read the novels she was writing about), respecting the perimeters that have to be respected but also noticing the holes in the fence. Holes that either need mending—or that give you, the writer, the opportunity to light out for new territory.

I can’t remember how many times, after working on a piece for six or so months, breaking promise after deadline promise, I would send John a draft, only to have him notice an un-pursued line of the argument, requiring another month or so of new writing, which he would happily encourage me to undertake. It was work, but it never felt like work. Or perhaps it felt like work as the early Marx—or Sherlock Holmes (“My mind rebels at stagnation. Give me problems, give me work, give me the most abstruse cryptogram or the most intricate analysis, and I am in my own proper atmosphere. I can dispense then with artificial stimulants.”)—imagined it.

But as generous as John is with time and space (one of my pieces clocked in at 11,000 words), he’s never careless or indulgent. At one point in a piece I was working on about Hannah Arendt, I wanted to introduce a whole new section on Arendt, Phillip Roth, and comedy. John gently reined me in, reminding me that the stage was already crowded with a cast of characters; introduce one or two more, he warned, and I’d overwhelm the play.

Above all, John respects the writer. That doesn’t mean he caters to the writer; he can be as tough and uncompromising as anyone. But when he is tough and uncompromising, you trust—you know—he’s doing it for the piece.

Other editors serve other gods. Some care only about what their bosses tell them, so they pass on the directives from on high, often as if they were their own, which makes for a crazy-making relationship with writers. Others want to impose their political line on a piece, which has led me to explode on more than one occasion, “If that’s what you want the piece to say, why don’t you fucking write it?” And still others are simply frustrated writers, who view their authors as competition or the enemy.

Not John. John is like one of those editors you read about in those elegiac hagiographies of literary New York—William Shawn at The New Yorker, at least as Ved Mehta described him (“Every New Yorker piece is different,” Shawn said to Mehta, “You should feel free to write any way you want to”) or Maxwell Perkins, “editor of genius” to Hemingway and Fitzgerald—where the point is to celebrate and mourn, in equal parts, the lost art of editing.

John’s art is not lost. This is how he described it in an interview last summer:

You’re trying to put yourself into a state of “negative capability,” in the sense that the poet John Keats meant: a state of being in mysteries and uncertainties without any irritable reaching after fact and reason. For me, in terms of editing, negative capability means becoming preoccupied with the way a piece thinks, the way a writer wants his or her thinking to sound in language….I think good editors are invisible and present, but their presence is undetectable. How are they present? Through what’s been selected and the way a piece has been shaped through the conversation or the exchange that happens during the editorial process.

Ordinarily, when I hear this kind of talk, I get suspicious. There’s a certain liberal sensibility among writers and editors that holds itself to be open to any and all ideas that are good and true and strong, and opposed only to what is bad or false or weak. In my experience, that sensibility is usually a case of monumental self-deception or the flimsiest cover for an inexplicable attachment to a conventional set of not terribly interesting opinions.

Not with John. I’ve never met an intellectual who is so open to other people’s ideas. Just look at this list (at the bottom) of some of the authors and pieces he champions. Try to find a unifying voice, a line of march. Each piece is so much its own, each voice so distinct, you wonder how a single sensibility could have midwived them all into being. John certainly has a sensibility, but it’s a sensibility that wants voices as various as Vivian Gornick, Sam Moyn, Jana Prikyl, David Rieff, and Marilyn Robinson (on William James!) to sing.

And not just established voices, but the unfamiliar voices of newer writers and scholars (many of them graduate students). Writers like Tim Shenk, Jesse McCarthy, Neima Jahromi, Sophie Pinkham, Ava Kofman.

When other media mavens talk—and talk—about public intellectuals, they bask in the halo of an avant garde that has long since become the canon. John, by contrast, truly champions the tradition of the new. When he organizes a panel on public intellectuals, his aim is not to celebrate the voices we know or to mourn the voices we’ve lost. His goal is to examine “the extent to which [graduate] students are involved in launching and sustaining a host of new publications that are also part of the current renaissance in cultural journalism.”

It’s not that John is a literary philanthropist, generously doling out his intellectual charity to the needy. He’s just interested in what is interesting and thinks you should be interested in it, too: “A guiding principle for me,” he tells his interviewer, “is for a piece to tell the reader about something she didn’t know she needed to know.”

That desire to interest you, the reader, explains something I’ve always found so delightful about John. For all his literary abstemiousness—he refuses, almost as an ethical principle, to jump on any bandwagon; buzz is for bees—he has a shrewd eye for marketing an idea or a piece. As I write this post on a Sunday in a week that has seen the death of Prince and the ratcheting up of the war between Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders, it is a piece by intellectual historian Richard Bourke on the eighteenth-century philosopher David Hume—a classic Palattella assignment—that occupies one of the coveted “most popular” slots at the magazine.

When John and I were working on my “Nietzsche’s Marginal Children” piece, which generated a tremendous amount of controversy, it was he who made it into an intellectual event: by commandeering a space in literary Brooklyn where he organized three or four critics to respond to the piece on stage, by encouraging me to respond at length to my critics, and by standing by me through all the debate over that piece. Part of that last bit came from his sense of literary ethics: John’s the type of editor who would always stand by his writers. But part of it came from that sense of the intellectual camaraderie and literary conspiracy that are so critical to making a writer, or a piece of writing, into something more. Without pandering, without huckstership, John makes literary happenings.

As an editor, John brings to mind an unlikely comparison: Bertolt Brecht. Not Brecht the poet or the playwright (though John is a poet), not even Brecht the collaborator (though John is a collaborator), but Brecht the impresario of a new kind of theater, a theater that would be both popular and potent.

Make no bones about it, we have our eye on those huge [stadiums], filled with 15,000 men and women of every variety of class and physiognomy, the fairest and shrewdest audience in the world.

…

People are always telling us that we mustn’t simply produce what the public demands. But I believe that an artist, even if he sits in strictest seclusion in the traditional garret working for future generations, is unlikely to produce anything without some wind in his sails. And this wind has to be the wind prevailing in his own period, and not some future wind. There is nothing to say that this wind must be used for travel in any particular direction (once one has a wind one can naturally sail against it; the only impossibility is to sail with no wind at all or with tomorrow’s wind), and no doubt an artist will fall far short of achieving his maximum effectiveness today if he sails with today’s wind. It would be quite wrong to judge a play’s relevance or lack of relevance by its current effectiveness. Theatres don’t work that way.

A theater which makes no contact with the public is a nonsense.

Like Brecht, John wants an audience. But like Brecht, it must not be an audience created on any old terms. It must be an audience that is fair and shrewd, an audience that will learn, upon reading, that it needed to know what it now knows. John wants there to be a wind: not to sail with it or against it, but simply to sail.

That is what John has managed to achieve at The Nation. He has created a space for writers to find their audience. Not just to find, but to make, their audience.

While I wish John all the best in his new ventures, a part of me hopes there’s some shrewd Brechtian impresario of ideas out there—an editor’s publisher, perhaps, an uncommonly wise and ambitious patron, with cash to spare—who’ll be shrewd enough to lavish upon John the opportunity to build his own epic theater of ideas.

April 21, 2016

What’s a Jewish holiday without a little pressure or guilt? Maybe it’s not a holiday at all.

NB: Like the matzoh the Jews prepared in ancient Egypt, this post was written in great haste.

A few weeks ago, I invited my friend Lizzie to our seder Friday night. I knew that Lizzie had some ambivalence about the seder, so I stressed in my invitation that she should only come if she wanted to. Her response gave me a big laugh: “Only if I want to? How is it a holiday if there isn’t a little guilt and pressure thrown in?”

Which got me thinking about the Passover story and guilt. I originally was going to write something much longer on this, but I’m so exhausted at this point—having been shopping and cooking for a few days, with 26 more hours to go—that I don’t know that I can do much here beyond listing some random thoughts with no attempt at order or coherence.

My first thought was that the holiday is, of course, about emancipation and freedom, and it seems not quite Kosher for Passover to be celebrating it in a spirit of guilt and duty and obligation.

But who am I kidding? Every year, part of me thinks I wish I didn’t have to do this, I’m exhausted, I just want a break. And part of what keeps me going is a sense of duty and obligation and the guilt I know I would feel if I didn’t do the seder. And having attended my share of celebrations out of a similar sense of guilt and obligation, I know that some people must be coming to mine with comparable feelings.

Besides, I thought to myself, the freedom we talk about at Passover isn’t freedom from guilt or duty. Insofar as it is emancipation from the material conditions of slavery we celebrate, perhaps it is not even a species of psychic freedom at all. What has all this mannered obsessions with social conventions to do with slavery?

Well, if you read your Nietzsche, a lot. I don’t think Nietzsche ever quite comes out and says in the Genealogy of Morals that guilt is the invention of the slave class—if I weren’t so tired, I’d fish out the text and read it through again—but one could stitch the pieces together. Like so.

Early in the text, in Book I, before he gets to the concept of guilt, Nietzsche claims that our basic conceptions of good and evil are the ideas of the slave class. The slaves, who are without much power, who feel aggrieved and resentful about their lack of power, invent the idea of good and evil, of doing right by ourselves and by others, of acting justly, which then gradually migrates from their fetid souls, so filled with ressentiment, and the souls of the priests into the more beautiful minds of the master class. The masters internalize these ideas of good and evil, and are gradually tamed by them. Good and evil, in other words, are the weapons of vengeful slaves hoping to tame if not topple their masters.

Nietzsche has not yet broached the question of guilt in Book I, but one can see it slowly taking shape in this notion of the master class internalizing certain moral norms of behavior, which arise from the most aggrieved classes, and which force the masters to act with some forbearance, to limit if not give up their power altogether.

In Book II, Nietzsche changes tack, directly asking what are the origins of guilt. His answer is that guilt is rooted in or arises from or has some kind of correspondence to (whenever it comes to origins and causes in Nietzsche, you have to tread carefully) the relationship between debtors and creditors. He reminds us that Schuld, the German word for guilt, arises from Schulden, the German word for debts. Though creditors can come from all social ranks, Nietzsche seems to fixate on the creditor from the lower ranks (perhaps he’s thinking of the Jews here?) What the creditor achieves over the debtor is a kind of power: if the debtor doesn’t repay his debt, the creditor gets to do with him what he will. Perhaps even take a part of the debtor’s body in lieu of what he is owed (think Shylock in The Merchant of Venice). The creditor gets to partake of the rights of the master (I think Nietzsche uses almost that exact phrase). He gets to vent his spleen, his power, upon a social superior.

Gradually these norms of debt, of what we owe each other, are codified as morals and laws, and ultimately get internalized by the self. A bit later in the essay, Nietzsche makes what for me has always been one of his more luminous points about how previously the master—and humanity as a whole—was without depth. He, and they, were shallow beings. But it is with the creation of guilt, the invention of internal psychic space, that humanity, particularly the master, acquires psychic depth. He moves from contesting with his fellow masters on the battlefield to suppressing his desires for power and violence. That great external flat battlefield of his social existence gets introjected into the psychological existence of his mind. His mind is transformed into a vertical battlefield between reason and virtue and prudential restraint, on the one hand, and desire and aggression and violent amplitude on the other. As painful and cruel as it is—and Nietzsche spares no words in describing the cruelty we do to ourselves in the name of guilt—it is through that process that we become beings of depth, artists of the soul. (Freud has a line somewhere about how in our dreams, we are all artists of the soul. Or something like that.)

Again, I’d have to re-read the text to justify what I’m about to say, but I recall there being a correspondence between these two stories: in which morality is the tool of the slave class, and the guilt the tool of creditor class, which is often drawn from a lower class of social beings, and how both morality and guilt are used to tame if not dispossess the master class of all of its powers.

So perhaps the guilt that funds and fuels our celebration at Passover is not so surprising after all. We, the Jews, are a slave people, at least according to the text (I make no historical claims about the truth of the Exodus story here; it’s just the cultural narrative of who we are). We, the Jews, did not have an existence as a people before we were slaves; we were at best a family, Abraham’s family. Through our enslavement, and then our emancipation, we become a people. Perhaps that sense of guilt—not, obviously, the simple sense of social obligation that gets kicked in whenever we’re invited to a friend’s celebration, but the deeper sense of duty, of what we owe to each other and God, what we owe to our ancestors and to our children—was the necessary price we paid to become free.

Or at least to overpower our masters.

Happy Passover.

April 17, 2016

Maybe if you’re not at war with reality, you’re not focused enough: Bernie in Brooklyn

My eight-year-old daughter Carol and I went to hear Bernie in the park today. We went with our friends Greg Grandin, Manu Goswami, their daughter Eleanor, Manu’s mom Toshi, and thousands of others.

Three highlights.

First, New York City Council Member Jumaane Williams, who’s a former student of mine, stole the show. For me at any rate. He gave a great opening speech for Bernie (see the 8 minute mark here). After quoting a Daily News editorial that accused Bernie of being at “war with reality,” Williams responded, “You’re goddam right!…Maybe if you’re not at war with reality, you’re not focused enough.” Perfect. And then Williams added, “So all we’re asking is: The people who say that it cannot be done, please move out of the way of the people who are doing it.” Exactly.

Second, Bernie’s biggest applause line came—after he talked about how drugs and drug addiction should be treated as a medical problem, not a criminal offense— when he said, “We’re going to revolutionize mental health care in this country.” You could hear all of bourgeois Brooklyn scream with joy at the thought of “free psychoanalysis for everyone.”

Third, someone had two mock street signs. The first said “Liberty Avenue,” the second “Ambivalence Boulevard.” The person was holding them up as if they were an intersection. I wondered aloud what that was all about. My daughter offered: “They’re both good things.”

April 15, 2016

CUNY and NYS hypocrisy on academic freedom: okay to boycott North Carolina and Mississippi, but not Israel

The graduate students at CUNY voted today to support the call for an academic boycott of Israel. Good for them.

The vote was greeted with unsurprising opposition from the CUNY Graduate Center administration and from CUNY Chancellor James Milliken.

The Graduate Center stressed in a public statement that the vote is “not a resolution supported by the GC nor the university as a whole” and that the center is “opposed to academic boycotts which “directly violate academic freedom.”

“We are disappointed by this vote from one student group,” a statement from CUNY’s Chancellor James B. Milliken read, “but it will not change CUNY’s position.”

…

In the lead up to the vote, Milliken already made clear that he opposed the doctoral students’ endorsement of BDS.

“Other CUNY leaders and I have consistently and publicly opposed a boycott of Israel institutions of higher education,” Milliken wrote in a letter to the Forward.

Milliken also suggested that the student government’s endorsement would not have bearing on CUNY policy.

“At the end of the day,” he wrote, this is a call to action, but “a decision on this matter is the province of the CUNY Board of Trustees.”

Unsurprising, yet not without irony.

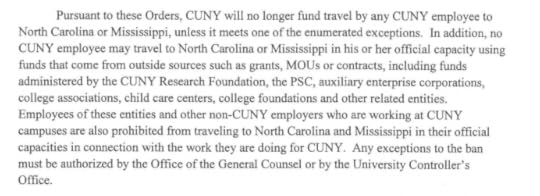

For in the very week that the Graduate Center and the chancellor were making these august pronouncements on behalf of academic freedom, Chancellor Milliken’s top lawyer was sending out a memo to all college presidents (including the president of the Graduate Center), provosts (including the provost of the Graduate Center) and other related financial officials, announcing that CUNY would be strictly enforcing Governor Cuomo’s ban on all non-essential travel of New York State employees to North Carolina and Mississippi. This ban is in response to both states’ passage of laws allowing discrimination against gays, lesbians, and transgender individuals.

If you think this ban has no impact on academic exchange, on our ability to interact with scholars in North Carolina and Mississippi, or indeed scholars from across the nation, or our ability to carry on our basic research, think again.

Should I, as a CUNY professor, wish to attend a conference or in North Carolina or do research in Mississippi, I would not be eligible to use any university funds to do so. Nor would I be allowed to use external or union grants to pay for these trips if—as is almost always the case with university faculty and such grants—these grants are administered through CUNY.

As any professor will tell you, without the university funding these trips or with the university preventing us from using our grants to fund these trips, we simply can’t do them.

CUNY’s announcement of this travel ban also reveals how empty Milliken’s claim is about how boycott decisions are “the province” of the Board of Trustees. As we can see here, the governor proposes and the governor disposes.

For the record, I have no problem with either this travel ban or CUNY’s decision to enforce it. I think it is a salutary use of state power and I hope it brings about the desired change.

But I wish people like Chancellor Milliken—and all the opponents of BDS at CUNY and elsewhere—would get off their high horse about the grave threat to academic freedom that would come from an academic boycott of Israel—which would not, unlike these North Carolina and Mississippi boycotts, be enforced through the state but would instead be entirely voluntary, the actions of both individuals and voluntarily associated collectives of individuals—and instead acknowledge that these are all legitimate ways of promoting the human rights and dignity, and indeed the academic freedom, of oppressed minorities and subjugated populations everywhere.

Magical Realism, and other neoliberal delusions

At Vox, Dylan Matthews offers a sharp analysis of last night’s debate, which I didn’t watch or listen to. His verdict is that the three big losers of the night were Hillary Clinton, the New Democrats, and liberal technocrats. (The two winners were Bernie Sanders and Fight for $15 movement.) As Matthews writes:

But just going through the issues at tonight’s debate, it’s striking to imagine a DLCer from the ’90s watching and wondering what his party had come to. Sanders was asked not if he was sufficiently tough on crime, but if his plans to let millions of convicted criminals out of prison would actually free as many felons as promised. Clinton was criticized not for being insufficiently pro-Israel, but for being insufficiently willing to assail the killing of Palestinian civilians. Twenty years after Clinton named former Goldman Sachs chief Robert Rubin as his Treasury secretary, so much as consorting with Goldman Sachs had become toxic.

Though I’m obviously pleased if Sanders beat Clinton in the debate, it’s the other two victories that are most important to me. For those of us who are Sanders supporters, the issue has never really been Hillary Clinton but always the politics that she stands for. Even if Sanders ultimately loses the nomination, the fact that this may be the last one or two election cycles in which Clinton-style politics stands a chance: that for us is the real point of this whole thing.

I‘m always uncertain whether Clinton supporters have a comparable view. While there are some, like Jonathan Chait or Paul Starr, for whom that kind of politics is substantively attractive, and who will genuinely mourn its disappearance, most of Clinton’s supporters seem to be more in synch with Sanders’s politics. They say they like Bernie and agree with his politics; it’s just not realistic, they say, to think that the American electorate will support that.

Which makes these liberals’ attraction to Clinton all the more puzzling. If it’s all pure pragmatism for you—despite your personal support for Bernie’s positions, you think only her style of politics can win in the United States—what are you going to do, the next election cycle, when there’s no one, certainly no one of her talent or skills and level of organizational support, who’s able to articulate that kind of politics?

2.

If she could turn back time:

Cher has been a vocal supporter of Hillary Clinton during this presidential election year, but now she may be changing her mind.

The singer took to Twitter on Wednesday to talk about the internal conflict she feels over which Democratic candidate to support for the presidency. In the past, Cher has criticized Bernie Sanders and his campaign staff….

However, on Wednesday, Cher said that after blocking people on Twitter she started to “feel uneasy” and went into “marathon research mode” with an open mind. She said that “in the quiet of the night,” she discovered that Sanders’ beliefs “mirrored” her own more than she had realized. The singer said she was “shaken to [her] core” by this revelation.

Cher went on to talk about how much she liked and respected Clinton, whom she spent time with when Clinton was running for the Senate. Cher said that she hopes the woman she fought hard for is still there, but that now she’s faced with a difficult decision.

“Realize now that I have MUCH common ground and new respect for [Bernie Sanders],” said Cher, adding that she’s torn up.

And don’t you dare say anything against Cher. I won’t have it.

3.

Until last night, I’d been seeing lots of Facebook posts and tweets from Clinton supporters citing Sanders’s appointment of Simone Zimmerman, who’s a critic of Israel, as his Jewish outreach coordinator, as an example of Sanders’s insufficient realism and political immaturity. Like the millennials he represents, goes the argument, Sanders is a starry-eyed dreamer who just doesn’t get it, who just doesn’t understand how the game is played.

Well, now we know that he does.

See how much skill, maturity, and sophistication it requires to fire someone just because she once called Netanyahu an asshole? See how quickly a candidate can get educated to do the kind of thuggish politics you Clinton folks think it takes years of experience and qualifications for a politician to learn? And doesn’t it just give you a Jean Arthur-like thrill to see the impractical idealist forced to play politics like the most practiced of pols? Aren’t you excited, gratified, that he’s shown you he’s got what it takes? I hope so.

I can be as Machiavellian or Weberian as the best of them. I just have this cockeyed optimist belief that if the ruthlessness you’re supposed to learn in politics really requires the kind of realism and skill and experience that people who pride themselves on their realism, skill, and experience think that it requires, then that ruthlessness should involve a slightly higher order of business than whether or not a campaign staffer once called a head of state an asshole.

4.

The men and women who drive and maintain New York City’s subways and buses think it’s more important that Sanders supports them and other workers than that he imagines we still use tokens. They’re unrealistic.

5.

By his own admission, President “I am not opposed to all wars. I’m opposed to dumb wars” made the same mistake in Libya that President “Mission Accomplished” made in Iraq. It’s almost as if that Best and the Brightest thing doesn’t always work out.

Obama’s admission that his failure to plan for a post-reconstruction Libya was his greatest mistake—and his concomitant refusal to say that the intervention was a mistake—makes me wonder how many times a government gets to make the same “mistake” before we get to say that the mistake is no mistake but how the policy works.

I mean when you have a former University of Chicago Law School professor/former Harvard Law Review editor doing the exact same thing that his alleged ignoramus of a predecessor did in Iraq, when you see that the failure to plan for a post-intervention reconstruction is not a contingency but a bipartisan practice, don’t you start wondering about the ideology of intervention itself?

I wrote about a version of this question in a piece I did in the London Review of Books on the ideology of national security after the revelations of Abu Ghraib:

The 20th century, it’s said, taught us a simple lesson about politics: of all the motivations for political action, none is as lethal as ideology. The lust for money may be distasteful, the desire for power ignoble, but neither will drive its devotees to the criminal excess of an idea on the march. Whether the idea is the triumph of the working class or of a master race, ideology leads to the graveyard.

Although liberal-minded intellectuals have repeatedly mobilised some version of this argument against the isms of right and left, they have seldom mustered a comparable scepticism about that other idée fixe of the 20th century: national security. Some liberals will criticise this war, others that one, but no one has ever written a book entitled ‘The End of National Security’. This despite the millions killed in the name of security, and even though Stalin and Hitler claimed to be protecting their populations from mortal threats.

There are fewer than six degrees of separation between the idea of national security and the lurid crimes of Abu Ghraib. First, each of the reasons the Bush administration gave for going to war against Iraq – the threat of WMD, Saddam’s alleged links to al-Qaida, even the promotion of democracy in the Middle East – referred in some way to protecting America. Second, everyone agrees that getting good intelligence from Iraqi informers is a critical element in defeating the insurgency. Third, US military intelligence believes that sexual humiliation is an especially forceful instrument for extracting information from recalcitrant Muslim prisoners.

Many critics have protested against Abu Ghraib, but none has traced it back to the idea of national security. Perhaps they believe such an investigation is unnecessary. After all, many of them opposed the war on the grounds that US security was not threatened by Iraq. And some of national security’s most accomplished practitioners, such as Brent Scowcroft and Zbigniew Brzezinski, as well as theoreticians like Steven Walt and John Mearsheimer, even claimed that a genuine consideration of US interests militated against the war. The mere fact that some politicians misused or abused the principle of national security need not call that principle into question. But when an idea routinely accompanies, if not induces, atrocities – Abu Ghraib was certainly not the first instance of the United States committing or sponsoring torture in the name of security – second thoughts would seem to be in order. Unless, of course, defenders of the idea wish to join that company of ideologues they so roundly condemn, affirming their commitment to an ideal version of national security while disowning its ‘actually existing’ variant.

6.

What was it Jonathan Chait said last month? “Reminder: liberalism is working.”

Thought of that reading this headline from last year.

7.

I’m always amused by the way that non-experts in the media and politics insist that on every issue, our presidential candidates should have the expertise of a university professor.

Any university professor will tell you that you can only have that kind of expertise in one, maybe two, areas.

In the wake of the controversy over Sanders’s interview with the Daily News, where ill-informed journalists made ill-informed judgments about Sanders’s lack of expertise, Charli Carpenter, a genuine academic expert on international relations, makes the necessary points:

Yes, he’s still vague on details. But if Sanders doesn’t know enough about foreign policy (yet) at least he’s willing to say so. Ultimately Sanders is taking most heat because he refused to bullshit his way through places where he felt out of his depth. But as a foreign policy expert, I was heartened by his willingness to say, ‘I haven’t thought enough about that yet,’ and his comfort in acknowledging and correcting mistakes of fact or semantics. I see this as a strength, not a weakness – in my students, in my colleagues, in people generally and certainly in a Presidential candidate. The world is a complex place and none of us are or can be experts on everything. Indeed, as someone who lived under the rule of George W. Bush – a President who also knew precious little about the world but acted as if he didn’t need guidance from experts – this foreign policy ‘pro’ finds the humility of Sanders’ stance, coupled with the sensibility and morality of his vision, not a little reassuring.

8.

I’m seeing a lot of folks posting this piece, attributing the election victory of a right-wing Republican judge in Wisconsin to the failure of Bernie supporters in Wisconsin to vote in that down-ballot election or to vote the right way, and more generally going after Bernie for not doing enough for down-ballot Democratic candidates. (And there have been many other pieces like that in Mother Jones and elsewhere.)

I find this a peculiar line of attack, particularly for people who say that it’s what leading them not to support Sanders and to vote for Clinton instead.

Many of these folks voted twice for Obama, and would vote for him again, despite the fact that he presided over the greatest loss of down-ballot seats of any two-term president since Truman. Under Obama, Democrats lost 11 governorships, 13 Senate seats, 69 House seats, and 913 state legislative seats and 30 state legislative chambers. According to various analysts, that’s about twice the average of postwar presidents. Yet somehow we live with it. But Bernie’s failure to get a judge elected in Wisconsin? That’s crossing a line.

Oh, and by the way, in 2008, there was another election of a Republican State Supreme Court judge in Wisconsin in tandem with the state primary. The Democratic incumbent lost that judicial election—despite the victory in that primary a certain Senator by the name of Barack Obama.

I don’t mind good solid critiques of Bernie, but I find these kinds of concerns to be little more than a performance of hard-headed civic realism, replete with that usual combination of requisite journo-speak (“down ballot”) and faux wonkery.

9.

Dateline for this headline: August 11, 2015.

#Realists

10.

Fathers and Sons…

Arthur Goldhammer is one of the most brilliant and acclaimed translators of our time. He’s also firmly in Clinton’s camp. Zack Goldhammer is a radio producer/ freelance writer and Art’s son. He’s also firmly in Bernie’s camp. They disagree, and argued it out here.

Their exchange brings out the generational divide so clearly, between the Boomers who, in this case, voted for Eldridge Cleaver as a write-in candidate in 1968—and as I’ve argued before, have been repenting for their sins ever since—and the millennials who, well, have other memories and experiences.

What I particularly like about Zack’s response is this:

For me, this distinction between incremental versus revolutionary change is a false dualism.

Nothing sets my teeth on edge more than these earnest droning lectures we get—not from Art, whose earnest droning lectures I love (seriously, he’s a good guy)—about the need for realism and moderation against our youthful penchant for revolution and idealism.

In part because at the age of 48, this is hardly my first time at the rodeo. (Nothing like being lectured to by journalists who are half my age about the need to grow up.)

But more important because the distinction is itself so surreal, so much the idée fixe of the Luftmensch, so much an artifact of academic seminars and common room debates. When I hear these lectures, I don’t hear someone who’s had real political experience, someone who’s been around the block; I hear someone who’s a college freshman and has just read this really exciting text—it could be Reinhold Niebuhr, Czesław Miłosz, or the latest squib in Vox—and decided, maybe after a bad encounter with an annoying campus activist, that he’s discovered the secret of the universe.

And who then slips into a lifetime of enchantment, periodically emitting, in an incantatory mode, words like “moderate” or “slow” or “nuance” or “subtle.”

Now that’s what I call Magical Realism.

April 13, 2016

Once upon a time, leftists purged from American academe could find a refuge abroad. Not anymore.

During the Cold War, leftist scholars purged from American academe at least had the opportunity, sometimes, to start again outside the country. That’s how Moses Finley became Sir Moses Finley, the internationally acclaimed classicist at Cambridge. That’s how Chandler Davis, aka Mr. Natalie Zemon Davis, became an internationally acclaimed mathematician at the University of Toronto. But now it seems as if even that escape route is being denied to Steven Salaita, who was unanimously recommended by a search committee for a position at the American University of Beirut, only to have the university’s president scuttle the search. There’s a petition circulating here; please sign it.

April 9, 2016

What’s going to happen to liberals when the Right begins to give way?

So much of liberals’ orientation these past five decades has been shaped by the rise of the right; by the sense that the US is really, truly, in its heart of hearts, a center/right country; that the people who elected Nixon, Reagan, and Bush really are the permanent majority.

But a lot of demographic research is showing that this is radically changing among younger voters. Not just what we’re seeing in the Democratic Party, where younger voters are moving, galloping, to the left, but also among younger Republican voters, who are far less conservative than their Republican elders. As this Vox piece reports:

Piles of research had already indicated that the youngest generation is much more liberal than its predecessors.

But it turns out it’s not just that young people are in general more likely to identify as liberal or that young liberals are to the left of older liberals — though both of these phenomena do appear to be true.

It turns out young Republicans are also likely to be to the left of older Republicans, according to a new study from Gary C. Jacobson, a political scientist at the University of California San Diego.

Going into the research, Jacobson said he more or less expected young conservatives to be to their parents’ left on issues like same-sex marriage and immigration.

But Jacobson said he found sharp splits by age among Republicans on almost every topic, from whether they believe President Barack Obama is a Muslim to whether they listen to conservative talk radio. (Jacobson used a new Gallup data set involving 400,000 responses that he said hadn’t been previously analyzed.)

Perhaps just as surprising: Fewer young Republicans are willing to identify themselves as conservative.

…

One big question is if these trends will hold up as these younger conservatives grow up, have children, and begin paying taxes.

There’s reason to believe they will. Jacobson’s research is built around a well-known phenomenon in political science known as “generational imprinting” that’s been documented since the 1950s.

It’s a simple idea: Essentially, young people decide their political identities when they’re “coming of political age” — or when they first really begin paying attention to what’s going on in politics.

These large-scale demographic shifts are going to pose a big challenge to liberals.

Neoliberals will increasingly lose the ability to discipline the left by invoking the fear of the right. More genuine liberals, whose sympathies lie with the left but whose sensibility has been so disciplined by the right that they’ve sincerely internalized these norms as the outermost edge of what is politically legitimate, will also have to rethink. When your mental horizons are so constructed and constrained by something like Reaganism, you grow attached to them and find it hard to give them up, even when conditions change.

As Emily Dickinson wrote, “Because that fearing it so long/ Had almost made it dear.”

April 7, 2016

I love my students

I’m not one of those professors who says, “I love my students,” but…I love my students.

This semester, I’m teaching the department capstone seminar. For the first half, I have the students read classics of political economy, from Aristotle through Gary Becker. In the second half, they choose a book about the contemporary political economy, and write an analysis of it through the lens of, or against the grain of, one of our class readings. They also do a class presentation of their final papers, something I haven’t tried since my first year at Brooklyn College.

So tonight was our first night of presentations. One student had chosen as his text Mark Blyth’s Austerity: The History of a Dangerous Idea, which he used to very powerful effect as a critique of Hayek, whom we had read in class. Then, in the middle of our discussion of his paper, another student asked, “After reading Hayek, do you think you can truly value something if you don’t have to pay for it?” Bam, the conversation’s off!

Another student used Aristotle’s Ethics and his Politics as a launching point for Elisabeth Armstrong’s and Laura Hamilton’s Paying for the Party: How College Maintains Inequality. She did a great analysis of how Aristotelian hierarchies of labor, leisure, and knowledge are reproduced by colleges and universities today. Then, in our discussion of her paper, another student asks, tentatively, timidly, “What…would happen … if we separated … the economy … from … education?” The class explodes in discussion and debate.

I’m not one of those professors who says, “I love my students,” but…I love my students.

And as much as I complain about everything at CUNY, tonight is one of those nights when I feel truly sorry for those of you who don’t get a chance to teach here.

Corey Robin's Blog

- Corey Robin's profile

- 163 followers