Corey Robin's Blog, page 102

June 14, 2013

Think you have nothing to hide from surveillance? Think again.

People often say that they don’t think government surveillance is such a big deal because they have nothing to hide. They post on Facebook or Twitter, their life is an open book.

What they don’t realize, as this excellent article points out (h/t Chase Madar), is that they might very well have something to hide. And the reason they don’t realize that is that they—like all of us—have no clue as to just how extensive the federal criminal code is.

The US criminal code is scattered across 27,000 pages. And that doesn’t include the roughly 10,000 additional administration regulations the government has promulgated. So extensive and sprawling are these laws and regulations that the Congressional Research Service cannot even count how many federal crimes there are.

This can have grave consequences: not for your privacy but for your immunity from government harassment and coercion.

As Justice Breyer puts it:

The complexity of modern federal criminal law, codified in several thousand sections of the United States Code and the virtually infinite variety of factual circumstances that might trigger an investigation into a possible violation of the law, make it difficult for anyone to know, in advance, just when a particular set of statements might later appear (to a prosecutor) to be relevant to some such investigation.

And as the author of the piece goes onto comment:

For instance, did you know that it is a federal crime to be in possession of a lobster under a certain size? It doesn’t matter if you bought it at a grocery store, if someone else gave it to you, if it’s dead or alive, if you found it after it died of natural causes, or even if you killed it while acting in self defense. You can go to jail because of a lobster.

If the federal government had access to every email you’ve ever written and every phone call you’ve ever made, it’s almost certain that they could find something you’ve done which violates a provision in the 27,000 pages of federal statues or 10,000 administrative regulations. You probably do have something to hide, you just don’t know it yet.

The selective invocation and application of criminal prosecutions and penalties is one of the oldest tools of repressive government. (Anyone wanting a refresher should consult Otto Kirchheimer’s classic discussion of “patterns of prosecution” in his Political Justice: The Use of Legal Procedures for Political Ends. As Kirchheimer writes, “Modern administrative practices create infinite ways to become liable to criminal prosecution.”) The sheer sprawl of federal (and don’t forget state and local) law—and the surveillance of men and women that now accompanies that sprawl—only enables this furhter.

June 13, 2013

Theory and Practice at NYU

New York University’s mission is to be an international center of scholarship, teaching and research defined by a culture of academic excellence and innovation. That mission involves retaining and attracting outstanding faculty, encouraging them to create programs that draw the best students, having students learn from faculty who are leaders in their fields, and shaping an intellectually rich environment for faculty and students both inside and outside the classroom. In reaching for excellence, NYU seeks to take academic and cultural advantage of its location in New York City and to embrace diversity among faculty, staff and students to ensure the widest possible range of perspectives, including international perspectives, in the educational experience.

It is ironic that at a time when sustaining the university as sanctuary is so important to society at large, society itself has unleashed forces which threaten the vitality if not the existence of that sacred space….

Forces outside our gates threaten the sanctity of the dialogue on campus. Begin with an obvious example. Every university president, and most deans, at some point have to face sometimes enormous external pressure because a controversial speaker is coming to campus. Inviting speakers from the right or from the left, from the fringes or even from the majority, often attracts varying degrees of protest and accompanying demands that the speaker be banned.

…

Frequently the external pressure is not reserved for protesting visiting speakers. Once unleashed, those who would exclude or punish certain views are more than willing to apply their muscle in an attempt to silence members of the university’s faculty or other members of the community.

…

At the same time, again in the name of security, we see an increasing official intolerance toward foreign professors and students, with new immigration restrictions which bear no apparent relation to genuine security concerns but which certainly hamper the capacity of America’s universities to bring into the conversation on campus those who are most talented, regardless of their country of origin. Foreign nationals interested in coming to our universities face longer application periods, extensive background checks, and constant monitoring; and many perfectly innocent professors and students effectively have been denied entry through burdensome and lengthy application procedures—and, astonishingly, some simply have been seeking to return after brief visits home to universities where they already have spent months or even years. The result: the Institute of International Education now reports that the number of foreign nationals coming to teach and study in the United States has all but stagnated, reversing a fifty-year trend of increased enrollment and thereby depleting our capacity to understand other cultures and diminishing our chance to have them understand us.

Today’s New York Post:

NYU isn’t letting a pesky thing like human rights stand in the way of its expansion in China.

The university has booted a blind Chinese political dissident from its campus under pressure from the Communist government as it builds a coveted branch in Shanghai, sources told The Post.

Chen Guangcheng has been at NYU since May 2012, when he made a dramatic escape from his oppressive homeland with the help of Hillary Rodham Clinton.

But school brass has told him to get out by the end of this month, the sources said.

Chen’s presence at the school didn’t sit well with the Chinese bureaucrats who signed off on the permits for NYU’s expansion there, the sources said.

June 11, 2013

David Brooks: The Last Stalinist

David Brooks disapproves of NSA whistle-blower Edward Snowden.

Snowden’s actions, Brooks says, are a betrayal of virtually every commitment and connection Snowden has ever made: his oath to his country, his promise to his employer, his loyalty to his friends, and more.

But in one of those precious pirouettes of paradox that only he can perform, Brooks sees those betrayals as a symptom of a deeper pathology: Snowden’s inability to make commitments and connections.

According to The Washington Post, he has not been a regular presence around his mother’s house for years. When a neighbor in Hawaii tried to introduce himself, Snowden cut him off and made it clear he wanted no neighborly relationships. He went to work for Booz Allen Hamilton and the C.I.A., but he has separated himself from them, too.

Though thoughtful, morally engaged and deeply committed to his beliefs, he appears to be a product of one of the more unfortunate trends of the age: the atomization of society, the loosening of social bonds, the apparently growing share of young men in their 20s who are living technological existences in the fuzzy land between their childhood institutions and adult family commitments.

If you live a life unshaped by the mediating institutions of civil society, perhaps it makes sense to see the world a certain way: Life is not embedded in a series of gently gradated authoritative structures: family, neighborhood, religious group, state, nation and world. Instead, it’s just the solitary naked individual and the gigantic and menacing state.

This lens makes you more likely to share the distinct strands of libertarianism that are blossoming in this fragmenting age: the deep suspicion of authority, the strong belief that hierarchies and organizations are suspect, the fervent devotion to transparency, the assumption that individual preference should be supreme.

This is an old argument on the communitarian right and left: the loss of social bonds and connections turns men and women into the flotsam and jetsam of modern society, ready for any reckless adventure, no matter how malignant: treason, serial murder, totalitarianism.

It’s mostly bullshit, but there’s a certain logic to what Brooks is saying, albeit one he might not care to face up to.

In the long history of state tyranny, it is often those who are bound by close ties of personal connection to family and friends that are most likely to cooperate with the government: that is, not to “betray” their oaths to a repressive regime, not to oppose or challenge authoritarian rule. Precisely because those ties are levers that the regime can pull in order to engineer an individual’s collaboration and consent.

Take the Soviet Union under Stalin. Though there’s a venerable tradition in social thought that sees Soviet totalitarianism as the product of atomized individuals, one of the factors that made Stalinism possible was precisely that men and women were connected to each other, that they were in families and felt bound to protect each other. To protect each other by cooperating with rather than opposing Stalin.

Nikolai Bukharin’s confession in a 1938 show trial to an extraordinary career of counterrevolutionary crime, crimes he clearly did not commit, has long served as a touchstone of the manic self-liquidation that was supposed to be communism. It has inspired such treatments as Arthur Koestler’s Darkness at Noon, Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s Humanism and Terror, and Godard’s La Chinoise. Yet contrary to the myth that Bukharin somehow chose to sacrifice himself for the sake of the cause, Bukharin was brutally interrogated for a year and he was repeatedly threatened with violence against his family. In the end, the possibility that a confession might save them, if not him, proved to be potent. (1)

Threats against family members were one of the most effective means for securing cooperation with the Soviet regime; in fact, many of those who refused to confess had no children. As I wrote in Fear: The History of a Political Idea:

Stalin corralled many individuals to cooperate with his tyranny by threatening their families, and had less success among those with no families. In a 1947 letter, the head of Soviet counterintelligence recommended invoking suspects’ “family and personal ties” during interrogation sessions. Soviet interrogators would put on their desks, in full view, the personal effects of suspects’ relatives as well as a copy of a decree legalizing the execution of children. (2)

It wasn’t just under Stalin that family ties could be leveraged like this. The entire history of McCarthyism, that sordid story of the blacklist and naming names, is littered with similar concerns, albeit of a less lethal variety.

Sterling Hayden—best known for his roles as General Jack D. Ripper in Dr. Strangelove and the corrupt Captain McCluskey in The Godfather—named seven names (including his former lover) in part because he was worried that if he didn’t cooperate with the government he might lose custody of his children (he was in the middle of divorce proceedings.) (3)

More often, those who cooperated with the government did so because they feared they wouldn’t be able to support their families. That was certainly the case with Roy Huggins, a now forgotten screenwriter, producer, and director, who gave us television shows like The Fugitive and The Rockford Files. Huggins named 19 names to HUAC—though he refused to spell them for the committee, prompting Victor Navasky to drily comment that Huggins deemed it more principled “to give the names but not the letters.” Though Huggins daydreamed of the political theater of going to prison rather than betray his comrades—witnesses refusing to name names could be cited for contempt of Congress and then be tried, convicted, and jailed—he worried too much about his family to resist: “Who the hell is going to take care of two small children, a mother, and a wife, all of whom are totally dependent on me?” (4)

As Elia Kazan deliberated over whether to name names (he eventually did), he told the producer Kermit Bloomgarden—who was responsible for bringing such plays as Death of a Salesman, The Diary of Anne Frank, and Equus to the American stage—that “I’ve got to think of my kids.” To which Bloomgarden responded, “This too shall pass, and then you’ll be an informer in the eyes of your kids, think of that.” And while Kazan had other options that would have kept his family afloat, as did writers who could write under pseudonyms, that was not the case with well known actors like Lee J. Cobb, who declared “It’s the only face I have.” Or Zero Mostel, who said, “I am a man of thousand faces, all of them blacklisted.” (Cobb named names. Mostel did not.) (5)

But it’s not just family connections that do the enabling work of state repression. Other trusted figures in our lives—teachers and preachers, lovers and therapists, even lawyers—can be used by the state (or can make themselves useful to the state) to encourage us to cooperate, to remind us that our local obligations to family and friends, to partners and loved ones, trump our larger moral and political commitments.

Hayden’s example is again instructive. As I wrote in Fear:

The more immediate influences on Hayden’s decision, however, were Martin Gang, his lawyer, and Phil Cohen, his therapist. When Hayden first began to suspect that he was being blacklisted, he turned to Gang for advice. Gang suggested that he draft a letter to J. Edgar Hoover, explaining his past involvement in the party and expressing sincere repentance. Cooperating with the FBI, said Gang, would keep Hayden under HUAC’s radar and out of the television lights. Unconvinced, Hayden turned to Cohen, who assured him that Gang’s recommendation was reasonable. So advised, Hayden submitted the letter. But on the day he was scheduled to speak with the FBI, he had second thoughts. “Martin,” he told his lawyer,

“I still don’t feel right about –”

“Sterling, now listen to me. We’ve been over this thing time and time again. You make entirely too much of it. The time to have felt this way was before we wrote the letter.”

“Yes, I guess you’re right.”

“You know I’m right. You made the mistake. Nobody told you to join the Party. You’re not telling the F.B.I. anything they don’t already know.”

Hayden spoke with the FBI, which only made him feel worse and turned him against his therapist. “I’ll say this, too,” he told Cohen, “that if it hadn’t been for you I wouldn’t have turned into a stoolie for J. Edgar Hoover. I don’t think you have the foggiest notion of the contempt I have had for myself since the day I did that thing.” Not long after, HUAC issued him a subpoena. Cohen again tried to pacify him. “Now then,” said Cohen, “may I remind you there’s really not much difference, so far as you yourself are concerned, between talking to the F.B.I. in private and taking the stand in Washington. You have already informed, after all. You have excellent counsel, you know.” Again, Hayden capitulated.

And as I went onto conclude:

In recent years, scholar and writers have extolled the virtues of an independent civil society, in which private circles of intimate association are supposed to shield men and women from a repressive state. To the extent that these links are explicitly political and oppositional, this account of civil society holds true. Few of us have the inner strength or sustaining vision to opt for the lonely path of a Socrates or a Solzhenitsyn. Deprived of the solidarity of comrades, our visions seem idiosyncratic and quixotic; fortified by our political affiliations, they seem moral and viable.

But what analysts of civil society often ignore is the experience of Hayden and others like him, how our everyday connections can echo or amplify our inner counsels of fear. “Friends and family worry about me,” writes Mino Akhtar, a Pakistani American management consultant in New Jersey who has campaigned against the war in Iraq and the secret detention of Arabs and Muslims after 9/11. “They tell me to be careful, that I’m taking risks. They say that if my face and name keep coming up in public I won’t get any more consulting jobs. I think about that sometimes. You work hard to establish yourself, you have the good job, big home, these mortgage payments; it’s scary to think you can lose it all.”

It is precisely the nonpolitical, personal nature of these connections that makes them so powerful a voice for cooperation. Afraid, we think about our lives and livelihoods, loved ones and friends, and we doubt the meaning or efficacy of our politics. When comrades advise us to resist, we discard their counsel as so much political rhetoric; when trusted intimates advise us to submit, we hear the innocent, apolitical voice of natural reason. Because these counsels of submission are not seen as political recommendations, they are ideal packages of covert political transmission.

Back to David Brooks. Brooks likes to package his strictures in the gauzy wrap of an apolitical communitarianism. But Brooks is also, let us not forget, an authority- and state-minded chap, who doesn’t like punks like Snowden mucking up the work of war and the sacralized state. And it is precisely banal and familial bromides such as these—the need to honor one’s oaths, the importance of family and connection—that have underwritten popular collaboration with that work for at least a century, if not more.

Stalin understood all of this. So does David Brooks.

Notes

(1) J. Arch Getty and Oleg V. Naumov, The Road to Terror: Stalin an the Self-Destruction of the Bolsheviks, 1932-1939 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999), 40, 48-49, 369-70, 392-399, 411, 417-419, 526; Stephen F. Cohen, Bukharin and the Bolshevik Revolution: A Political Biography, 1888-1938 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1971), 375-380; The Great Purge Trial, ed. Robert C. Tucker and Stephen F. Cohen (New York: Grosset and Dunlap, 1965), xlii-xlviii.

(2) Robert Conquest, The Great Terror: Stalin’s Purge of the Thirties (London: Macmillan, 1968), 142, 301; Getty and Naumov, 418, 526; Sheila Fitzpatrick, Everyday Stalinism: Ordinary Life in Extraordinary Times (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 25; Anne Applebaum Gulag: A History (New York: Doubleday, 2003), 139; Cohen, 375; Adam Hochschild, The Unquiet Ghost: Russians Remember Stalin (New York: Viking, 1994), 13, 21-22; Tina Rosenberg, The Haunted Land: Facing Europe’s Ghosts After Communism (New York: Vintage, 1995), 28-29.

(3) Sterling Hayden, Wanderer (New York: Knopf, 1963), 371-372; Larry Ceplair and Steven Englund, The Inquisition in Hollywood: Politics in the Film Community, 1930-1960 (Garden City: Anchor Press, 1980), 386-389; Victor Navasky, Naming Names (New York: Penguin, 1980), 100-101.

(4) Navasky, 258, 260, 281.

(5) Navasky, 178, 201-202.

June 10, 2013

Snitches and Whistleblowers: Who would you rather be?

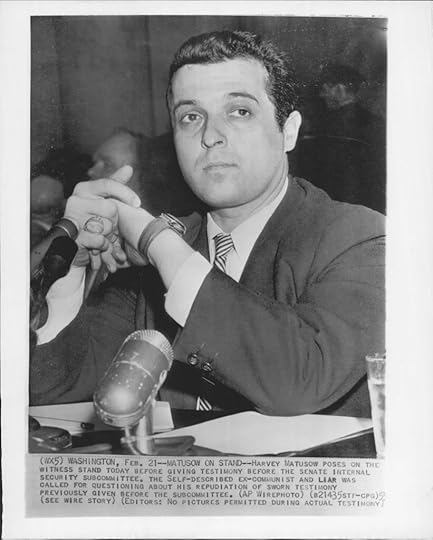

Who would you rather be?

Edward Snowden

Or this guy?

Harvey Matusow testifying before Senate Internal Subcommittee

The twentieth century was the century of Matusow, Kazan, and other assorted informers, informants, and snitches, behind the Iron Curtain, in Nazi Germany, in Latin America, in the United States. Everywhere.

Let the 21st be the century of Snowden, Manning, and more.

June 6, 2013

Jumaane Williams and the Brooklyn College BDS Controversy Revisited

There’s a long profile of NYC Councilman Jumaane Williams in BKLYNR, a new Brooklyn-based magazine, by Eli Rosenberg. It’s a fascinating read of a fascinating politician, who played a less than fascinating role during the Brooklyn College BDS controversy. Williams is a former student of mine, and he and I wound up in a heated Twitter argument about his role.

In his piece, Rosenberg discusses the Williams and the BDS controversy at length. You should read the whole article, but I’m excerpting the BDS part here:

The perils of navigating the dual worlds of politics and activism were resoundingly clear earlier this year. Two leaders of a movement critical of Israel — pioneering gender theorist and activist Judith Butler and Palestinian rights activist Omar Barghouti — were scheduled to speak at Brooklyn College in an event billed as a lecture on the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement, which advocates for economic protests against Israel. The event was sponsored by a student group, Brooklyn College Students for Justice in Palestine, but the college’s political science department had signed on as a co-sponsor.

A couple weeks before the event, another student organization, the college’s United4Israel chapter, posted a petition online that expressed “deep concern” over the school’s co-sponsorship of the lecture. By the time Harvard law professor and Brooklyn College alum Alan Dershowitz weighed in a week before the event with a Daily News op-ed that called it a “propaganda hate orgy,” the story had bloomed into a full-blown controversy.

Local politicians like assemblymen Dov Hikind and Steven Cymbrowitz, who both hail from heavily Jewish districts near Brooklyn College, organized a press conference to denounce the college. Much of the city’s political establishment soon weighed in on the controversy, with nearly all of everyone coming down heavily against the school.

A self-proclaimed “progressive” coalition officials sent a letter to college president Karen Gould, signed by a who’s who of politicians in the city — including four of the top Democratic candidates for mayor — expressing “concern” that the college had signed onto the event and accusing it of stifling academic freedom. A group of ten council members, led by Lew Fidler, penned a letter to Gould asking her to cancel the event entirely, and hinted that the CUNY school’s funding, some of which passes through the city council each year, could be affected by the decision.

For a couple of days, as event spiraled into a larger and larger story, Williams and his office were quiet on the issue. It was a notable silence given both Williams’ strong connections to the school and its political science department, as well as the simple fact that its 26-acre campus lies squarely in his district.

But on February 1, Williams’ office released a copy of a letter the councilman had sent Gould. “I have concerns regarding the sponsorship by the Political Science Department of this event,” Williams wrote. “I am asking for your intervention with Chair Paisley Currah in an effort to allow both sides of this hot-button matter to be discussed with equity, preferably in the same forum. If that cannot be accomplished, I urge the removal of the department’s sponsorship of this event.”

The chorus of voices was getting louder for the department to cancel the event; media across the globe picked up the story, with articles in the Jerusalem Post and Al Jazeera in addition to the city’s major news sources. Glenn Greenwald weighed in on the pages of The Guardian, calling the liberal politicians a “lynch mob.”

For a moment, it seemed Brooklyn College would have to buckle. But it stood its ground and, at the last minute, received some support from an unlikely ally. At a press conference on Hurricane Sandy relief, Mayor Bloomberg, prompted by a reporter’s question, forcefully defended the college’s right to hold the event.

“If you want to go to a university where the government decides what kind of subjects are fit for discussion, I suggest you apply to a school in North Korea,” he said. “The last thing we need is for members of our city council or state legislature to be micromanaging the kinds of programs that our public universities run.”

In two minutes, any steam left behind the movement to get the college to cancel or change the event was gone. The idea of the mayor, the most powerful official in New York City and an avid supporter of Israel, announcing his support for the school caught the rest of the establishment off-guard.

Most of the city’s politicians who had so loudly protested the event released statements in support of it. The so-called progressive group of politicians sent a follow-up letter to Gould, thanking her for her “leadership on the issue,” and expressing support for the college and its forum. Council members Steve Levin and Letitia James revoked their support for the letter they had inked earlier in the week, claiming they “unsigned” it. And Williams released another statement expressing support for the forum and “confidence” in the state of academic freedom at Brooklyn College.

“No institution of learning should stifle voices in a debate, no matter how controversial or problematic they may be,” he wrote.

But the damage had already been done.

“The gr8 progressive @JumaaneWilliams ‘supports views expressed by my fellow alumnus Alan Dershowitz’ on #BDS event … SMH,” remarked Alex Kane, an editor at progressive sites AlterNate and Mondoweiss, on Twitter. Soon Williams’ feed and Facebook page were ablaze with comments from academics, progressive journalists, and enraged commenters.

Corey Robin, a political science professor at Brooklyn College who served as the department’s unofficial spokesman during the controversy and a former professor of Williams, entered into the most heated debate with him, in a lengthy exchange that Robin published online.

By the end of the hour-long debate, during which Williams was thoroughly chided by Robin, the councilman conceded numerous points to the academic and had assumed the role of a chastened student, referring to Robin as “professor,” and admitting that he would definitely “do more homework,” in the future.

“What I was trying to get across was correct. I don’t think that got across in my first letter,” Williams said recently. “I had not spoken to the chairperson, which I should have done. So my intention with the first letter was basically to say that there needs to be some rules about how sponsorship happens, and that everybody should have access to that sponsorship.”

Still, if you believe people like Robin, the event may yet come back to haunt him.

“He’s the pride and joy of the department, but people were surprised and are not going to forget that easily,” said Robin. “Everyone expected that Christine Quinn would do what she did, but I think we all expected more of him. I expected more of him.”

Williams has made a career out of calling it like he sees it, cultivating the image that he is the rare politician who will speak the truth without regard for the consequences. But part of that veneer was lost with the week’s events.

“It takes a Republican mayor who is horrible on many issues that progressives care about to explain that politicians do not meddle with curriculum or extracurricular discussions to people like Christine Quinn, Jumaane Williams, and Brad Lander?” said Robin. “It shows there are real constraints on liberalism and leftism in New York.”

Dobbs said the dust-up demonstrated the fundamental conflict between Williams’ identity as an activist and as a politician. “They’re incompatible,” said Dobbs. “Most people believe that politicians and elected officials are leaders, but actually they follow much more than they lead.”

Perhaps most damaging for Williams reputation was the perception of him as weak and susceptible, vulnerable in the game of politics.

“The media misunderstands liberals and thinks they want someone who is pure, but what the left really wants politicos who are shrewd about power and use it to achieve progressive goals,” said Robin. “He got played on this one; the moral reasons are very troubling, but it’s also very a troubling politically. He should have been shrewder about this. He went to Brooklyn College, he should have called the damn school, found out the facts first and spoken as an alum, to say ‘I understand the issues around this, I understand the department. Let me tell you about what I learned.’ It would have been a very moving statement. Instead he comes out looking like a chump.”

June 3, 2013

Panel discussion tonight: Hayek’s Triumph, Nietzsche’s Example, the Market’s Morals

If you’re in Brooklyn tonight, I’ll be joined by financial journalist Moe Tkacik, economist Suresh Naidu, and intellectual historian Thomas Meaney for a Nation-sponsored discussion of my essay “Nietzsche’s Marginal Children” in the May 27 issue of the The Nation. The discussion will be at Melville House in DUMBO (145 Plymouth Street) at 7 pm. Here’s a write-up of the event:

Is the Nobel Prize-winning economist Friedrich Hayek the link between the übermensch and the businessman?

In a provocative essay for the May 27 issue of The Nation, Corey Robin offers a radical reconsideration of the work of Hayek, its influence on neoliberalism and its elective affinities with Nietzsche’s thinking about labor and value. How did Hayek’s conservative ideas become our economic reality? Robin asks. By turning the market into the realm of aristocratic politics and morals.

Join us for a panel discussion about the essay and the issues.

Hope to see you all there.

May 27, 2013

Arbeit Macht Frei

Taking workplace feudalism up a notch:

A New York-based real estate firm Rapid Realty has offered its 800 employees a 15% pay raise if they tattoo the company’s logo onto their bodies, and the offer is snowballing, according to CBS New York. So far, nearly 40 employees accepted the challenge, AOL Jobs reported.

…

Employees who agreed to get inked said getting a substantially larger paycheck was motivation enough to get a tattoo. In a video, Brooklyn-based broker Adam Altman said the ink would be a reminder to work harder. “I don’t see myself going anywhere, and if I have it on my arm, it’ll force me to keep going and working hard [sic],” Altman said.

H/t Douglas Edwards

May 20, 2013

Obama at Morehouse, LBJ at Howard

Barack Obama at Morehouse College:

Well, we’ve got no time for excuses. Not because the bitter legacy of slavery and segregation have vanished entirely; they have not. Not because racism and discrimination no longer exist; we know those are still out there. It’s just that in today’s hyperconnected, hypercompetitive world, with millions of young people from China and India and Brazil — many of whom started with a whole lot less than all of you did — all of them entering the global workforce alongside you, nobody is going to give you anything that you have not earned.

Nobody cares how tough your upbringing was. Nobody cares if you suffered some discrimination. And moreover, you have to remember that whatever you’ve gone through, it pales in comparison to the hardships previous generations endured — and they overcame them. And if they overcame them, you can overcome them, too.

…

But if you stay hungry, if you keep hustling, if you keep on your grind and get other folks to do the same — nobody can stop you.

Lyndon Johnson at Howard University:

But freedom is not enough. You do not wipe away the scars of centuries by saying: Now you are free to go where you want, and do as you desire, and choose the leaders you please.

You do not take a person who, for years, has been hobbled by chains and liberate him, bring him up to the starting line of a race and then say, “you are free to compete with all the others,” and still justly believe that you have been completely fair.

Thus it is not enough just to open the gates of opportunity. All our citizens must have the ability to walk through those gates.

This is the next and the more profound stage of the battle for civil rights. We seek not just freedom but opportunity. We seek not just legal equity but human ability, not just equality as a right and a theory but equality as a fact and equality as a result.

For the task is to give 20 million Negroes the same chance as every other American to learn and grow, to work and share in society, to develop their abilities–physical, mental and spiritual, and to pursue their individual happiness.

To this end equal opportunity is essential, but not enough, not enough.

Update (May 21, 8:15 am)

Via Jordan Adam Banks, this from Ta-Nehisi Coates is excellent:

Taking the full measure of the Obama presidency thus far, it is hard to avoid the conclusion that this White House has one way of addressing the social ills that afflict black people — and particularly black youth — and another way of addressing everyone else. I would have a hard time imagining the president telling the women of Barnard that “there’s no longer room for any excuses” — as though they were in the business of making them. Barack Obama is, indeed, the president of “all America,” but he also is singularly the scold of “black America.”

It’s worth revisiting the president’s comments over the past year in reference to gun violence. Visiting his grieving adopted hometown of Chicago, in the wake of the murder of Hadiya Pendleton, the president said this:

For a lot of young boys and young men in particular, they don’t see an example of fathers or grandfathers, uncles, who are in a position to support families and be held up in respect. And so that means that this is not just a gun issue; it’s also an issue of the kinds of communities that we’re building. When a child opens fire on another child, there is a hole in that child’s heart that government can’t fill. Only community and parents and teachers and clergy can fill that hole.

Two months earlier Obama visited Newtown. The killer, Adam Lanza, was estranged from his father and reportedly devastated by his parents divorce. But Obama did not speak to Newtown about the kind of community they were building, or speculate on the hole in Adam Lanza’s heart.

…

No president has ever been better read on the intersection of racism and American history than our current one. I strongly suspect that he would point to policy. As the president of “all America,” Barack Obama inherited that policy. I would not suggest that it is in his power to singlehandedly repair history. But I would say that, in his role as American president, it is wrong for him to handwave at history,…

May 16, 2013

Everything you know about the movement against the Vietnam War is wrong

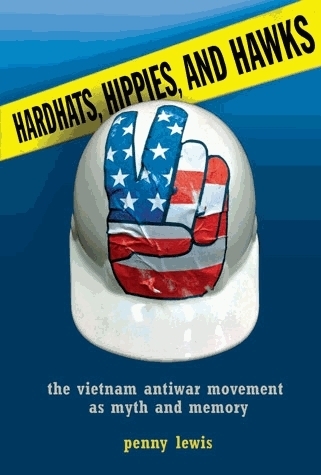

Penny Lewis, a sociologist at CUNY’s Murphy Institute for Worker Education and Labor Studies, has a new book out: Hardhats, Hippies, and Hawks: The Vietnam Antiwar Movement as Myth and Memory.

It’s a revisionist account of the movement against the Vietnam War that completely upends our sense of who was for and against the war. Even more interesting, it tells us how we came to such an upside down view of the antiwar movement.

Luckily I don’t have to summarize the book because Penny’s got a terrific piece out in this week’s Chronicle of Higher Education where she lays out the argument.

Just a quick excerpt:

The story we tell ourselves about social division over the war in Vietnam follows a particular, class-specific outline: The war “split the country” between “doves” and “hawks.” The “doves,” most often conflated with “the movement,” were upper-middle-class in their composition and politics. The movement was the New Left, and a big part of what made the New Left “new” was its break from the working-class politics and roots of the Old Left. Think of Dr. Benjamin Spock, Tom Hayden, Jane Fonda, Eugene McCarthy, George McGovern, Students for a Democratic Society, Weathermen: students, intellectuals, professionals, celebrities; liberal or radical privileged elites.

And what of the “hawks”? Beyond the military brass, war supporters are often imagined as “ordinary” Americans: white people from Middle America (a term coined in the 1960s), who supported God, country, and “our boys in the ‘Nam.” They were working-class patriots who insisted that criticism of the war meant criticism of the soldier. “If you can’t be with them, be for them,” as the sign read. Many of these Middle Americans epitomized moderate middle-class solidity and stolidity, while the workers among them, or members of the lower middle class, are remembered for having supported George Wallace and Richard Nixon, and their status as Reagan Democrats was imminent, even immanent, as early as 1968.

Most accounts of the working class depict them as largely supportive of the war and hostile to the numerous movements for social change. We need look no further than the most enduring image of the working class from that period, a certain cranky worker from Queens, N.Y. The TV character Archie Bunker, who brought the working class to prime time as white, bigoted, sexist, homophobic, and yearning for the good old days before the welfare state, when everybody pulled his weight, when girls were girls and men were men.

“Hardhats,” a stereotype based primarily on construction workers in New York City who assaulted antiwar protesters at a Manhattan rally in May 1970, were the iconic hawks. The most important working-class institution in the postwar era, the AFL-CIO, is remembered for being virulently anticommunist and vociferously pro-war; big labor’s embrace of the Vietnam cause confirmed the image of the working-class patriot who shouts “Love it or leave it!” at young, entitled hippies.

But this memory of the Vietnam era contains only half-truths, and overall it is a falsehood. The notion that liberal elites dominated the antiwar movement has served to obfuscate a more complex story. Working-class opposition to the war was significantly more widespread than is remembered, and parts of the movement found roots in working-class communities and politics.

In fact, by and large, the greatest support for the war came from the privileged elite, despite the visible dissension of a minority of its leaders and youth. The country was divided over the war, alongside many other pressing social issues—but the class dynamics of those divisions were complex, contradictory, and indeterminate.

Many books briefly discuss the discrepancy between our historical impression of class-based sentiment and its reality. Yet no account systematically explains why such a misperception exists, its extent, or its impact.

So read Penny’s piece. And then go buy her book. Trust me: you won’t regret it.

May 13, 2013

Critics respond to “Nietzsche’s Marginal Children”

I’ve been traveling for several days, but in the last 24 hours, a bunch of people have responded, all critically, to my “Nietzsche’s Marginal Children.” I just got back and have a bunch of teaching to do, so I haven’t had time to read them all and may not be able to get to them for a while. But I thought I’d post them here. I’ll try to get to them as soon as I can.

Kevin Vallier, one of the sharpest libertarian theorists out there with whom I’ve argued in the past, has what seems on a very quick glance to be a thorough critique (not trying to suggest it’s not thorough; I just only had time to skim it) over at Bleeding Heart Libertarians.

From the left, Philip Pilkington, who did a great interview with me about my book, also delivers what seems to be a lengthy and thorough critique over at Naked Capitalism. (Same caveat as above.)

Brian Doherty, who wrote a great book on libertarianism and with whom I’ve disagreed before, agrees with Vallier over at Reason. Jordan Bloom, at The American Conservative, also agrees with Vallier.

Anyway, that’s it for now. More soon, I hope.

Corey Robin's Blog

- Corey Robin's profile

- 163 followers