Glenn Greenwald's Blog, page 117

May 9, 2011

Bin Laden's death doesn't end his fear-mongering value

On Friday, government officials anonymously claimed that "a rushed examination" of the "trove" of documents and computer files taken from the bin Laden home prove -- contrary to the widely held view that he "had been relegated to an inspirational figure with little role in current and future Qaeda operations" -- that in fact "the chief of Al Qaeda played a direct role for years in plotting terror attacks." Specifically, the Government possesses "a handwritten notebook from February 2010 that discusses tampering with tracks to derail a train on a bridge," and that led "Obama administration officials on Thursday to issue a warning that Al Qaeda last year had considered attacks on American railroads." That, in turn, led to headlines around the country like this one, from The Chicago Sun-Times:

[image error]

The reality, as The New York Times noted deep in its article, was that "the information was both dated and vague," and the official called it merely "aspirational," acknowledging that "there was no evidence the discussion of rail attacks had moved beyond the conceptual stage" In other words, these documents contain little more than a vague expression on the part of Al Qaeda to target railroads in major American cities ("focused on striking Washington, New York, Los Angeles and Chicago," said the Sun-Times): hardly a surprise and -- despite the scary headlines -- hardly constituting any sort of substantial, tangible threat.

But no matter. Even in death, bin Laden continues to serve the valuable role of justifying always-increasing curtailments of liberty and expansions of government power. From Reuters (h/t Atrios):

Sen. Schumer proposes "no-ride list" for Amtrak trains

A senator on Sunday called for a "no-ride list" for Amtrak trains after intelligence gleaned from the raid on Osama bin Laden's compound pointed to potential attacks on the nation's train system.

Sen. Charles Schumer said he would push as well for added funding for rail security and commuter and passenger train track inspections and more monitoring of stations nationwide.

"Circumstances demand we make adjustments by increasing funding to enhance rail safety and monitoring on commuter rail transit and screening who gets on Amtrak passenger trains, so that we can provide a greater level of security to the public," the New York Democrat said at a news conference.

So Al Qaeda breathes the word "trains" and Schumer jumps and demands the creation of a massive, expensive and oppressive new Security State program to keep thousands and thousands of people off trains. The "no-fly" list has been nothing short of a Kafkaesque disaster: with thousands of people secretly placed on it without any explanation or real recourse, oftentimes causing them to be stranded in faraway places and unable to return home.

To replicate that for trains -- all because some documents mentioned them among thousands of other ideas Al Qaeda has undoubtedly considered over the years -- is hysteria and ludicrous over-reaction of the highest order. Trains can obviously be attacked without boarding them (indeed, these documents apparently discussed tampering with the rails, which wouldn't require boarding the trains at all). And if there's a "no-ride" list for Amtrak, why not for subways and buses, too? If Al Qaeda is found to have discussed targeting restaurants, will we have a no-eat list? If Al Qaeda is found to have discussed targeting large intersections or landmarks, will we have a no-walk list? How about a no-shop list in response to the targeting of malls?

But this, more or less, encapsulates the U.S. response to Terrorism since 9/11: the minute Al Qaeda utters a peep about anything, the political class collectively jumps to restrict our freedoms, empower the Government, and bankrupt ourselves in self-destructive pursuit of the ultimate illusion: Absolute Security. Al Qaeda has caused us to do more harm to ourselves than it could have ever dreamed of imposing on its own. And even in death, Osama bin Laden continues to serve as the pretext for all of this.

* * * * *

I recently sat for an interview with the ACLU in Massachusetts on a variety of topics, including the trade-off between security and freedom. Here is the two-minute segment on that topic, obviously related to all of this:

May 7, 2011

U.S. tries to assassinate U.S. citizen Anwar al-Awlaki

That Barack Obama has continued the essence of the Bush/Cheney Terrorism architecture was once a provocative proposition but is now so self-evident that few dispute it (watch here as arch-neoconservative David Frum -- Richard Perle's co-author for the supreme 2004 neocon treatise -- waxes admiringly about Obama's Terrorism and foreign policies in the Muslim world and specifically its "continuity" with Bush/Cheney). But one policy where Obama has gone further than Bush/Cheney in terms of unfettered executive authority and radical war powers is the attempt to target American citizens for assassination without a whiff of due process. As The New York Times put it last April:

It is extremely rare, if not unprecedented, for an American to be approved for targeted killing, officials said. A former senior legal official in the administration of George W. Bush said he did not know of any American who was approved for targeted killing under the former president. . . .

That Obama was compiling a hit list of American citizens was first revealed in January of last year when The Washington Post's Dana Priest mentioned in passing at the end of a long article that at least four American citizens had been approved for assassinations; several months later, the Obama administration anonymously confirmed to both the NYT and the Post that American-born, U.S. citizen Anwar al-Awlaki was one of the Americans on the hit list.

Yesterday, riding a wave of adulation and military-reverence, the Obama administration tried to end the life of this American citizen -- never charged with, let alone convicted of, any crime -- with a drone strike in Yemen, but missed and killed two other people instead:

A missile strike from an American military drone in a remote region of Yemen on Thursday was aimed at killing Anwar al-Awlaki, the radical American-born cleric believed to be hiding in the country, American officials said Friday.

The attack does not appear to have killed Mr. Awlaki, the officials said, but may have killed operatives of Al Qaeda's affiliate in Yemen.

The other people killed "may have" been Al Qaeda operatives. Or they "may not have" been. Who cares? They're mere collateral damage on the glorious road to ending the life of this American citizen without due process (and pointing out that the Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution expressly guarantees that "no person shall be deprived of life without due process of law" -- and provides no exception for war -- is the sort of tedious legalism that shouldn't interfere with the excitement of drone strikes).

There are certain civil liberties debates where, even though I hold strong opinions, I can at least understand the reasoning and impulses of those who disagree; the killing of bin Laden was one such instance. But the notion that the President has the power to order American citizens assassinated without an iota of due process -- far from any battlefield, not during combat -- is an idea so utterly foreign to me, so far beyond the bounds of what is reasonable, that it's hard to convey in words or treat with civility.

How do you even engage someone in rational discussion who is willing to assume that their fellow citizen is guilty of being a Terrorist without seeing evidence for it, without having that evidence tested, without giving that citizen a chance to defend himself -- all because the President declares it to be so? "I know Awlaki, my fellow citizen, is a Terrorist and he deserves to die. Why? Because the President decreed that, and that's good enough for me. Trials are so pre-9/11." If someone is willing to dutifully click their heels and spout definitively authoritarian anthems like that, imagine how impervious to reason they are on these issues.

And if someone is willing to vest in the President the power to assassinate American citizens without a trial far from any battlefield -- if someone believes that the President has that power: the power of unilaterally imposing the death penalty and literally acting as judge, jury and executioner -- what possible limits would they ever impose on the President's power? There cannot be any. Or if someone is willing to declare a citizen to be a "traitor" and demand they be treated as such -- even though the Constitution expressly assigns the power to declare treason to the Judicial Branch and requires what we call "a trial" with stringent evidence requirements before someone is guilty of treason -- how can any appeals to law or the Constitution be made to a person who obviously believes in neither?

What's most striking about this is how it relates to the controversies during the Bush years. One of the most strident attacks from the Democrats on Bush was that he wanted to eavesdrop on Americans without warrants. One of the first signs of Bush/Cheney radicalism was what they did to Jose Padilla: assert the power to imprison this American citizen without charges. Yet here you have Barack Obama asserting the power not to eavesdrop on Americans or detain them without charges -- but to target them for killing without charges -- and that, to many of his followers, is perfectly acceptable. It's a "horrific shredding of the Constitution" and an act of grave lawlessness for Bush to eavesdrop on or detain Americans without any due process; but it's an act of great nobility when Barack Obama ends their lives without any due process.

Not even Antonin Scalia was willing to approve of George Bush's mere attempt to detain (let alone kill) an American citizen accused of Terrorism without a trial. In a dissenting opinion joined by the court's most liberal member, John Paul Stevens, Scalia explained that not even the War on Terror allows the due process clause to be ignored when the President acts against those he claims have joined the Enemy -- and this was for a citizen found on an actual active battlefield in a war zone (Afghanistan) (emphasis added):

The very core of liberty secured by our Anglo-Saxon system of separated powers has been freedom from indefinite imprisonment at the will of the Executive. Blackstone stated this principle clearly: "Of great importance to the public is the preservation of this personal liberty: for if once it were left in the power of any, the highest, magistrate to imprison arbitrarily whomever he or his officers thought proper … there would soon be an end of all other rights and immunities. … To bereave a man of life, or by violence to confiscate his estate, without accusation or trial, would be so gross and notorious an act of despotism, as must at once convey the alarm of tyranny throughout the whole kingdom." . . . .

Subjects accused of levying war against the King were routinely prosecuted for treason. . . . The Founders inherited the understanding that a citizen's levying war against the Government was to be punished criminally. The Constitution provides: "Treason against the United States, shall consist only in levying War against them, or in adhering to their Enemies, giving them Aid and Comfort"; and establishes a heightened proof requirement (two witnesses) in order to "convic[t]" of that offense. Art. III, §3, cl. 1.

There simply is no more basic liberty than the right to be free from Presidential executions without being charged with -- and then convicted of -- a crime: whether it be treason, Terrorism, or anything else. How can someone who objected to Bush's attempt to eavesdrop on or detain citizens without judicial oversight cheer for Obama's attempt to kill them without judicial oversight? Can someone please reconcile those positions?

One cannot be certain that this attempted killing of Awlaki relates to the bin Laden killing, but it certainly seems likely, and in any event, highlights the dangers I wrote about this week. From the start, it was inconceivable to me that -- as some predicted -- the bin Laden killing would bring about a ratcheting down of America's war posture. The opposite seemed far more likely to me for the reason I wrote on Monday:

Whenever America uses violence in a way that makes its citizens cheer, beam with nationalistic pride, and rally around their leader, more violence is typically guaranteed. Futile decade-long wars in Iraq and Afghanistan may temporarily dampen the nationalistic enthusiasm for war, but two shots to the head of Osama bin Laden -- and the We are Great and Good proclamations it engenders -- can easily rejuvenate that war love. . . . We're feeling good and strong about ourselves again -- and righteous -- and that's often the fertile ground for more, not less, aggression.

The killing of bin Laden got the testosterone pumping, the righteousness pulsating, and faith in the American military and its Commander-in-Chief skyrocketing to all-time highs. It made America feel good about itself in a way that no other event has since at least Obama's inauguration; we got to forget about rampant unemployment, home foreclosures by the millions, a decade's worth of militaristic futility and slaughter, and ever-growing Third-World levels of wealth inequality. This was a week for flag-waving, fist-pumping, and nationalistic chanting: even -- especially -- among liberals, who were able to take the lead and show the world (and themselves) that they are no wilting, delicate wimps; it's not merely swaggering right-wing Texans, but they, too, who can put bullets in people's heads and dump corpses into the ocean and then joke and cheer about it afterwards. It's inconceivable that this wave of collective pride, boosted self-esteem, vicarious strength, and renewed purpose won't produce a desire to replicate itself. Four days after bin Laden is killed, a missile rains down from the sky to try to execute Awlaki without due process, and that'll be far from the last such episode (indeed, also yesterday, the U.S. launched a drone attack in Pakistan, ending the lives of 15 more people: yawn).

Last night, in a post entitled "Reigniting the GWOT [Global War on Terrorism]" -- Digby wrote about why the reaction to the killing of bin Laden is almost certain to spur greater aggression in the "War on Terror," and specifically observed: "They're breathlessly going on about Al Qaeda in Yemen 'targeting the homeland' right now on CNN. Looks like we're back in business." The killing of bin Laden isn't going to result in a reduction of America's military adventurism because that's not how the country works: when we eradicate one Enemy, we just quickly and seamlessly find a new one to replace him with -- look over there: Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula is the True Threat!!!! -- and the blood-spilling continues unabated (without my endorsing it all, read this excellent Chris Floyd post for the non-euphemistic reality of what we've really been doing in the world over the last couple years under the 2009 Nobel Peace Prize Winner).

A civil liberties lawyer observed by email to me last night that now that Obama has massive political capital and invulnerable Tough-on-Terror credentials firmly in place, there are no more political excuses for what he does (i.e., he didn't really want to do that, but he had to in order not to be vulnerable to GOP political attacks that he's Weak). In the wake of the bin Laden killing, he's able to do whatever he wants now -- ratchet down the aggression or accelerate it -- and his real face will be revealed by his choices (for those with doubts about what that real face is). Yesterday's attempt to exterminate an American citizen who has long been on his hit list -- far from any battlefield, not during combat, and without even a pretense of due process -- is likely to be but a first step in that direction.

May 6, 2011

The Osama bin Laden exception

When I first wrote about the bin Laden killing on Monday, I suggested that the intense (and understandable) emotional response to his being dead would almost certainly drown out any discussions of the legality, ethics, or precedents created by this event. That, I think, has largely been borne out, at least in the U.S. (one poll shows 86% of Americans favor the killing, though that's hardly universal: a poll in Germany finds 64% view this as "no reason to rejoice," while 52% believe an attempt should have been made to arrest him; many European newspapers have harshly criticized U.S. actions; and German Prime Minister Angela Merkel's declaration of happiness over bin Laden's death provoked widespread criticism even in her own party). I expected -- and fully understand -- that many people's view of the bin Laden killing is shaped first and foremost by happiness over his death.

But what has surprised me somewhat is how little interest there seems to be in finding out what actually happened here. We know very little about the circumstances of bin Laden's killing, because the U.S. government has issued so many contradictory claims, which in turn contradict the reported claims of those at the scene. When I wrote about this on Monday, I said that the use of force would be justified if, as the U.S. Government claimed, he was violently resisting his capture. But that turned out to be totally false. It's now beyond dispute that bin Laden was unarmed when killed and there was virtually no violent resistence in the house. Still, the range of possibilities for what actually happened is vast -- everything from he was lunging for his AK-47 to he was already captured when shot (in front of his family) to the order from the start was to kill, not capture, him -- and I personally don't see how it's possible to assess the justifiability (or legality) of what took place without knowing which of those are true.

Beyond the apparent indifference to how this killing took place, what has also surprised me somewhat is the lack of interest in trying to figure out how the bin Laden killing fits into broader principles and viewpoints about state power and the War on Terror. I've seen people who have spent the last decade insisting that the U.S. must accord due process to accused Terrorists before punishing them suddenly mock the notion that bin Laden should have been arrested and tried.

Beyond that, the formal position of the Democratic Party for years -- since John Kerry enunciated it when running against Bush -- has been that Terrorism should be primarily dealt with within a law enforcement rather than war paradigm, and that Terrorists should be viewed as criminals, not warriors; and yet many of the same people who once rejected the war paradigm now turn around and cite war theories to justify bin Laden's killing as a "proper military target" (that isn't necessarily contradictory -- it's possible to argue against a war paradigm while still recognizing that that's the paradigm created by our law -- but the comfort in citing war theories among those who long argued against them is quite striking). Obviously, in a law enforcement setting, one is barred from shooting an unarmed, non-resisting suspect; that can be justified only by resort to war and military theories. If you believe that Terrorists are criminals and not warriors, and that the law enforcement context is the proper one to apply, how can the shooting of an unarmed suspect be justified?

Then there's the strange indifference to finding out whether bin Laden was actually captured before executed. Not only have reports conveyed, via Pakistani officials, that his daughter claims this (a report [like U.S. government claims] deserving substantial skepticism, though not dismissal), but also the President's formulation when first announcing the killing provides added evidence for that possibility (though the CIA denies this happened). How can that not matter? Hasn't the entire debate about torture centered on the proposition that states have a moral and legal obligation not to abuse helpless detainees, given that their captivity means they have been rendered harmless? Shouldn't we want to know if bin Laden was captured before being killed, and wouldn't that make some difference in assessing one's views of his killing?

I think what's really going on here is that there are a large number of people who have adopted the view that bin Laden's death is an unadulterated Good, and it therefore simply does not matter how it happeend (ends justify the means, roughly speaking). There are, I think, two broad groups adopting this mindset: (1) those, largely on the Right, who believe the U.S. is at War and anything we do to our Enemies is basically justifiable; and (2) those, mostly Democrats, who reject that view -- who genuinely believe in general in due process and adherence to ostensible Western norms of justice -- yet who view bin Laden as a figure of such singular Evil (whether in reality or as a symbol) that they're willing to make an exception in his case, willing to waive away their principles just for him: creating the Osama bin Laden Exception.

Although I don't agree with it, I have a healthy respect for that latter reaction. None of us is a pure rationality machine. We all at some point depart from our principles in particular cases, or find reasons to make exceptions, or simply view the outcome as so desirable that we don't care how it can be reconciled with our claimed views. But I think if one is going to do that here, then one is obligated to acknowledge it and then grapple with what it means and what the implications are -- rather than just pretending that it's not happening.

That's why I found this confession from Jonathan Capehart of The Washington Post's Editorial page to be so commendable as an act of intellectual honesty and even courage. Capehart explains that, if you had asked him even a month ago, he would have said that he wanted bin Laden brought to trial -- not killed without process -- and would have vehemently objected to the use of torture to find him. But upon hearing the news of his death, Capehart was so happy at the outcome that he did not care about those principles at all:

But a funny thing happened when my feelings smacked up against the reality of bin Laden's sudden and violent death.

When questions started being asked about the role enhanced interrogation techniques may have played, I found myself thinking, "I don't care what was done." When the question about whether he should have been captured instead of killed arose, I found myself not caring that bin Laden took two bullets to the head. What I cared about was that bin Laden was dead.

John Cole was equally forthright about this:

I'm the hypocrite here. I'm stridently against extrajudicial killings, the death penalty, targeted assassination, etc. I'd wager most of you are, too.

But when I heard that Osama had been killed, I'll be damned if I didn't think "Thank God that monster is gone." Sure, in my ideal world he'd be brought back to the US, tried, and then imprisoned for the rest of his life. But you know what? I can not honestly say I give a damned that he took a double tap to the skull. Sorry. And I'd be also willing to bet that is where most of you all are- this may or may not have been legal, but you don't give a shit, because that scumbag is at the bottom of an ocean somewhere and got what he deserved. I'd be lying if I didn't admit that a primitive part of me was sort of sad he didn't experience any pain.

What Capehart and Cole are expressing is the Osama bin Laden Exception: yes, I believe in all these principles of due process and restraining unfettered Executive killing and the like, but in this one case, I don't care if those are violated. Like I said, though I strongly disagree with that view, I understand and respect it, particularly given the honesty with which it's expressed.

My principal objection to it -- aside from the fact that I think those principles shouldn't be violated because they're inherently right (which is what makes them principles) -- is that there's no principled way to confine it to bin Laden. If this makes sense for bin Laden, why not for other top accused Al Qaeda leaders? Why shouldn't the same thing be done to Anwar al-Awlaki, the U.S. citizen who has been allegedly linked by the Government to far more attacks over the last several years than bin Laden? At Guantanamo sits Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the alleged operational mastermind of 9/11 -- who was, if one believes the allegations, at least as responsible for the attack as bin Laden and about whom there is as little perceived dobut; why shouldn't we just take him out back today and shoot him in the head and dump his corpse into the ocean rather than trying him?

Once you embrace the bin Laden Exception, how does it stay confined to him? Isn't it necessarily the case that you're endorsing the right of the U.S. Government to treat any top-level Terrorists in similar fashion? Again, this isn't an argument that the bin Laden killing was illegal; it very well may have been legal, depending on the facts. But if we just cheer for this without caring about those facts, isn't it clear that we're endorsing a dangerous unfettered power -- one that runs afoul of multiple principles which opponents of the Bush/Cheney template have long defended?

For me, the better principles are those established by the Nuremberg Trials, and numerous other war crimes trials accorded some of history's most gruesome monsters. It should go without saying for all but the most intellectually and morally stunted that none of this has anything to do with sympathy for bin Laden. Just as was true for objections to the torture regime or Guantanamo or CIA black sites, this is about the standards to which we and our Government adhere, who we are as a nation and a people.

The Allied powers could easily have taken every Nazi war criminal they found and summarily executed them without many people caring. But they didn't do that, and the reason they didn't is because how the Nazis were punished would determine not only the character of the punishing nations, but more importantly, would set the standards for how future punishment would be doled out. Here was the very first paragraph uttered by lead Nuremberg prosecutor Robert Jackson when he stood up to deliver his Opening Statement:

The privilege of opening the first trial in history for crimes against the peace of the world imposes a grave responsibility. The wrongs which we seek to condemn and punish have been so calculated, so malignant, and so devastating, that civilization cannot tolerate their being ignored, because it cannot survive their being repeated. That four great nations, flushed with victory and stung with injury stay the hand of vengeance and voluntarily submit their captive enemies to the judgment of the law is one of the most significant tributes that Power has ever paid to Reason.

And here was the last thing he said:

Civilization asks whether law is so laggard as to be utterly helpless to deal with crimes of this magnitude by criminals of this order of importance. It does not expect that you can make war impossible. It does expect that your juridical action will put the forces of international law, its precepts, its prohibitions and, most of all, its sanctions, on the side of peace, so that men and women of good will, in all countries, may have "leave to live by no man's leave, underneath the law."

I actually believe in those precepts. And if those principles were good enough for those responsible for Nazi atrocities, they are good enough for the likes of Osama bin Laden. It's possible they weren't applicable here; if he couldn't be safely captured because of his attempted resistence, then capturing him wasn't a reasonable possibility. But it seems increasingly clear that the objective here was to kill, not capture him, no matter what his conduct was. That, at the very least, raises a whole host of important questions about what we endorse and who we are that deserves serious examination -- much more than has thus far prompted by this celebrated killing.

* * * * *

Yesterday, I recorded a one-hour BloggingheadsTV session with former Bush speechwriter, the neoconservative David Frum, debating these and related matters.

May 4, 2011

The illogic of the torture debate

The killing of Osama bin Laden has, as The New York Times notes, reignited the debate over "brutal interrogations" -- by which it's meant that Republicans are now attempting to exploit the emotions generated by the killing to retroactively justify the torture regime they implemented. The factual assertions on which this attempt is based -- that waterboarding and other "harsh interrogation methods" produced evidence crucial to locating bin Laden -- are dubious in the extreme, for reasons Andrew Sullivan and Marcy Wheeler document. So fictitious are these claims that even Donald Rumsfeld has repudiated them.

But even if it were the case that valuable information were obtained during or after the use of torture, what would it prove? Nobody has ever argued that brutality will never produce truthful answers. It is sometimes the case that if you torture someone long and mercilessly enough, they will tell you something you want to know. Nobody has ever denied that. In terms of the tactical aspect of the torture debate, the point has always been -- as a consensus of interrogations professionals has repeatedly said -- that there are far more effective ways to extract the truth from someone than by torturing it out of them. The fact that one can point to an instance where torture produced the desired answer proves nothing about whether there were more effective ways of obtaining it.

This highlights what has long been a glaring fallacy in many debates over War on Terror policies: that Information X was obtained after using Policy A does not prove that Policy A was necessary or effective. That's just basic logic. This fallacy asserted itself constantly in the debate over warrantless surveillance. Proponents of the Bush NSA program would point to some piece of intelligence allegedly obtained during warrantless eavesdropping as proof that the illegal program was necessary and effective; obviously, though, that fact said nothing about whether the same information would also have been discovered through legal eavesdropping, i.e., eavesdropping approved in advance by the FISA court (and indeed, legal eavesdropping [like legal interrogation tactics] is typically more effective than the illegal version because, by necessity, it is far more focused on actual suspected Terrorism plots; warrantless eavesdropping entails the unconstrained power to listen in on any communications the Government wants without having to establish its connection to Terrorism). But in all cases, the fact that some piece of intelligence was obtained by some lawless Bush/Cheney War on Terror policy (whether it be torture or warrantless eavesdropping) proves nothing about whether that policy was effective or necessary.

And those causal issues are, of course, entirely independent of the legal and moral questions shunted to the side by this reignited "debate." There are many actions that the U.S. could take that would advance its interests that are nonetheless obviously wrong on moral and legal grounds. When Donald Trump recently suggested that we should simply take Libya's oil and that of any other country which we successfully invade and occupy, that suggestion prompted widespread mockery. That was the reaction despite the fact that stealing other countries' oil would in fact produce substantial benefits for the U.S. and advance our interests: it would help to lower gas prices, reduce our dependence on hostile oil-producing nations, and avoid having to degrade our own environment in order to drill domestically. Trump's proposal is morally reprehensible and flagrantly lawless despite how many benefits it would produce; therefore, no person of even minimal decency would embrace it no matter how many benefits it produces.

Exactly the same is true for the torture techniques used by the Bush administration and once again being heralded by its followers (and implicitly glorified by media stars who keep suggesting that they enabled bin Laden's detection). It makes no difference whether it extracted usable intelligence. Criminal, morally depraved acts don't become retroactively justified by pointing to the bounty they produced.

* * * * *

It was striking to note in yesterday's New York Times the obituary of Moshe Landau, the Israeli judge who presided over the 1961 war crimes trial of Adolf Eichmann. It's a reminder that when even the most heinous Nazi war criminals were hunted down by the Israelis, they weren't shot in the head and then dumped into the ocean, but rather were apprehended, tried in a court of law, confronted with the evidence against them for all the world to see, and then punished in accordance with due process. The same was done to leading Nazis found by Allied powers and tried at Nuremberg. It's true that those trials took place after the war was over, but whether Al Qaeda should be treated as active warriors or mere criminals was once one of the few ostensible differences between the two parties on the question of Terrorism.

Speaking of which: I know that very few people have even a slight interest in the unexciting, party-pooping question of whether our glorious killing comported with legal principles, but for those who do, both The Guardian and Der Spiegel have good discussions of that issue.

May 3, 2011

In bin Laden killing, media -- as usual -- regurgitates false Government claims

Virtually every major newspaper account of the killing of Osama bin Laden consists of faithful copying of White House claims. That's not surprising: it's the White House which is in exclusive possession of the facts, but what's also not surprising is that many of the claims that were disseminated yesterday turned out to be utterly false. And no matter how many times this happens -- from Jessica Lynch's heroic firefight against Iraqi captors to Pat Tillman's death at the hands of Evil Al Qaeda fighters -- it never changes: the narrative is set forever by first-day government falsehoods uncritically amplified by establishment media outlets, which endure no matter how definitively they are disproven in subsequent days.

Yesterday, it was widely reported that bin Laden "resisted" his capture and "engaged in a firefight" with U.S. forces (leaving most people, including me, to say that his killing was legally justified because he was using force). It was also repeatedly claimed that bin Laden used a women -- his wife -- has a human shield to protect himself, and that she was killed as a result. That image -- of a cowardly through violent-to-the-end bin Laden -- framed virtually every media narrative of the event all over the globe. And it came from many government officials, principally Obama's top counter-terrorism adviser, John Brennan.

Those claims have turned out to be utterly false. From TPM toda:

It was a fitting end for the America's most wanted man. As President Barack Obama's Deputy National Security Adviser John Brennan told it, a cowardly Osama bin Laden used his own wife as a human shield in his final moments. Except that apparently wasn't what happened at all.

Hours later, other administration officials were clarifying Brennan's account. Turns out the woman that was killed on the compound wasn't bin Laden's wife. Bin Laden may have not even been using a human shield. And he might not have even been holding a gun.

Politico's Josh Gerstein adds: "The White House backed away Monday evening from key details in its narrative about the raid that killed Osama bin Laden, including claims by senior U.S. officials that the Al Qaeda leader had a weapon and may have fired it during a gun battle with U.S. forces." Gerstein added: "a senior White House official said bin Laden was not armed when he was killed."

Whether bin Laden actually resisted his capture may not matter to many people; the White House also claimed that they would have captured him if they had the chance, and this fact seems to negate that claim as well. But what does matter is how dutifully American media outlets publish as "news reports" what are absolutely nothing other than official White House statements masquerading as an investigative article. And the fact that this process continuously produces highly and deliberately misleading accounts of the most significant news items -- falsehoods which endure no matter how decisively they are debunked in subsequent days -- doesn't have the slightest impact on the American media's eagerness to continue to serve this role.

* * * * *

Mona Eltahwy has an excellent column in The Guardian today headlined: "No dignity at Ground Zero. As a US Muslim I abhor the frat boy reaction."

Speaking of "frat boy reactions," Leon Panetta is excitingly speculating about which actors should portray him in the movie about the Hunt for bin Laden, helpfully suggesting Al Pacino. It's been a long time since Americans felt this good and strong about themselves -- nothing like putting bullets in someone's skull and dumping their corpse into an ocean to rejuvenate that can-do American sense of optimism.

May 2, 2011

Killing of bin Laden: What are the consequences?

(updated below)

The killing of Osama bin Laden is one of those events which, especially in the immediate aftermath, is not susceptible to reasoned discussion. It's already a Litmus Test event: all Decent People -- by definition -- express unadulterated ecstacy at his death, and all Good Americans chant "USA! USA!" in a celebration of this proof of our national greatness and Goodness (and that of our President). Nothing that deviates from that emotional script will be heard, other than by those on the lookout for heretics to hold up and punish. Prematurely interrupting a national emotional consensus with unwanted rational truths accomplishes nothing but harming the heretic (ask Bill Maher about how that works).

I'd have strongly preferred that Osama bin Laden be captured rather than killed so that he could be tried for his crimes and punished in accordance with due process (and to obtain presumably ample intelligence). But if he in fact used force to resist capture, then the U.S. military was entitled to use force against him, the way American police routinely do against suspects who use violence to resist capture. But those are legalities and they will be ignored even more so than usual. The 9/11 attack was a heinous and wanton slaughter of thousands of innocent civilians, and it's understandable that people are reacting with glee over the death of the person responsible for it. I personally don't derive joy or an impulse to chant boastfully at the news that someone just got two bullets put in their skull -- no matter who that someone is -- but that reaction is inevitable: it's the classic case of raucously cheering in a movie theater when the dastardly villain finally gets his due.

But beyond the emotional fulfillment that comes from vengeance and retributive justice, there are two points worth considering. The first is the question of what, if anything, is going to change as a result of the two bullets in Osama bin Laden's head? Are we going to fight fewer wars or end the ones we've started? Are we going to see a restoration of some of the civil liberties which have been eroded at the altar of this scary Villain Mastermind? Is the War on Terror over? Are we Safer now?

Those are rhetorical questions. None of those things will happen. If anything, I can much more easily envision the reverse. Whenever America uses violence in a way that makes its citizens cheer, beam with nationalistic pride, and rally around their leader, more violence is typically guaranteed. Futile decade-long wars in Iraq and Afghanistan may temporarily dampen the nationalistic enthusiasm for war, but two shots to the head of Osama bin Laden -- and the We are Great and Good proclamations it engenders -- can easily rejuvenate that war love. One can already detect the stench of that in how Pakistan is being talked about: did they harbor bin Laden as it seems and, if so, what price should they pay? We're feeling good and strong about ourselves again -- and righteous -- and that's often the fertile ground for more, not less, aggression.

And then there's the notion that America has once again proved its greatness and preeminence by killing bin Laden. Americans are marching in the street celebrating with a sense of national pride. When is the last time that happened? It seems telling that hunting someone down and killing them is one of the few things that still produce these feelings of nationalistic unity. I got on an airplane last night before the news of bin Laden's killing was known and had actually intended to make this point with regard to our killing of Gadaffi's son in Libya -- a mere 25 years after President Reagan bombed Libya and killed Gadaffi's infant daughter. That is something the U.S. has always done well and is one of the few things it still does well. This is how President Obama put it in last night's announcement:

The cause of securing our country is not complete. But tonight, we are once again reminded that America can do whatever we set our mind to. That is the story of our history, whether it's the pursuit of prosperity for our people, or the struggle for equality for all our citizens; our commitment to stand up for our values abroad, and our sacrifices to make the world a safer place.

Does hunting down Osama bin Laden and putting bullets in his skull really "remind us that we can do whatever we set our mind to"? Is that really "the story of our history"? That seems to set the bar rather low in terms of national achievement and character.

In sum, a murderous religious extremist was killed. The U.S. has erupted in a collective orgy of national pride and renewed faith in the efficacy and righteousness of military force. Other than that, the repercussions are likely to be far greater in terms of domestic politics -- it's going to be a huge boost to Obama's re-election prospects and will be exploited for that end -- than anything else.

UPDATE: Recall what happened in 2003 when Howard Dean interrupted the national celebratory ritual triggered by Saddam Hussein's capture when he suggested that that event would likely not make us safer. He was demonized by political leaders in both parties, with Joe Lieberman finally equating him with Saddam by accusing Dean of being in a "spider hole of denial." That will be the same demonizing reaction targeted at anyone who deviates from today's ritualistic script.

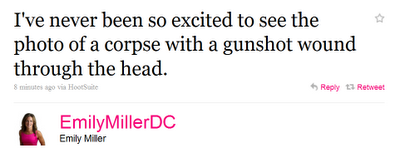

Meanwhile, here is the reaction to today's events from Emily Miller of The Washington Times Editorial Page:

Those primitive, bloodthirsty Muslim fanatics sure do love to glorify death and violence.

Those primitive, bloodthirsty Muslim fanatics sure do love to glorify death and violence.

May 1, 2011

This week

Extensive traveling over the last few days prevented me from writing; regular posting should resume tomorrow. Until then, here is video and audio from several events and appearances I did last week:

(1) The FAIR event at which I spoke on Thursday in New York was one of the best political events I've attended. The sold-out event had in excess of 1,000 people in attendance. The crowd was loud and enthused; the energy in the auditorium was invigorating; and all of the speeches were truly great. Only segments of the video seem to be online thus far at Free SpeechTV, but the full, downloadable audio for all four of the speeches -- from me, Amy Goodman, Noam Chomsky and Michael Moore -- are here. To convey the feel of the event, here are a couple of video snippets from my speech -- regarding the evolution of my views of the media -- but all four speeches are truly worth listening to:

freespeechtv on livestream.com. Broadcast Live Free

(2) I was on MSNBC with Dylan Ratigan on Thursday discussing the last post I wrote -- regarding the militarization of the CIA -- as well as Obama's foreign policy and secrecy fixation, WikiLeaks and Bradley Manning. The video of the segment is here:

(3) I was on Democracy Now on Friday morning discussing a variety of topics. The two-part segment can be seen here:

April 28, 2011

A more militarized CIA for a more militarized America

The first four Directors of the CIA (from 1947-1953) were military officers, but since then, there has been a tradition (generally though imperfectly observed) of keeping the agency under civilian rather than military leadership. That's why George Bush's 2006 nomination of Gen. Michael Hayden to the CIA provoked so many objections from Democrats (and even some Republicans).

The Hayden nomination triggered this comment from the current Democratic Chairwoman of the Senate Intelligence Committee, Dianne Feinstein: "You can't have the military control most of the major aspects of intelligence. The CIA is a civilian agency and is meant to be a civilian agency." The then-top Democratic member of the House Intelligence Committee, Jane Harman, said "she hears concerns from civilian CIA professionals about whether the Defense Department is taking over intelligence operations" and "shares those concerns." On Meet the Press, Nancy Pelosi cited tensions between the DoD and the CIA and said: "I don't see how you have a four-star general heading up the CIA." Then-Sen. Joe Biden worried that the CIA, with a General in charge, will "just be gobbled up by the Defense Department." Even the current GOP Chair of the House Intelligence Committee, Pete Hoekstra, voiced the same concern about Hayden: "We should not have a military person leading a civilian agency at this time."

Of course, like so many Democratic objections to Bush policies, that was then and this is now. Yesterday, President Obama announced -- to very little controversy -- that he was nominating Gen. David Petraeus to become the next CIA Director. The Petraeus nomination raises all the same concerns as the Hayden nomination did, but even more so: Hayden, after all, had spent his career in military intelligence and Washington bureaucratic circles and thus was a more natural fit for the agency; by contrast, Petraues is a pure military officer and, most of all, a war fighting commander with little background in intelligence. But in the world of the Obama administration, Petraeus' militarized, warrior orientation is considered an asset for running the CIA, not a liability.

That's because the CIA, under Obama, is more militarized than ever, as devoted to operationally fighting wars as anything else, including analyzing and gathering intelligence. This morning's Washington Post article on the Petraeus nomination -- headlined: "Petraeus would helm an increasingly militarized CIA" -- is unusual in presenting such a starkly forthright picture of how militarized the U.S. has become under the 2009 Nobel Peace Prize winner:

Gen. David H. Petraeus has served as commander in two wars launched by the United States after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks. If confirmed as the next director of the Central Intelligence Agency, Petraeus would effectively take command of a third -- in Pakistan.

Petraeus's nomination comes at a time when the CIA functions, more than ever in its history, as an extension of the nation's lethal military force.

CIA teams operate alongside U.S. special operations forces in conflict zones from Afghanistan to Yemen. The agency has also built up a substantial paramilitary capability of its own. But perhaps most significantly, the agency is in the midst of what amounts to a sustained bombing campaign over Pakistan using unmanned Predator and Reaper drones.

Since Obama took office there have been at least 192 drone missile strikes, killing as many as 1,890 militants, suspected terrorists and civilians. Petraeus is seen as a staunch supporter of the drone campaign, even though it has so far failed to eliminate the al-Qaeda threat or turn the tide of the Afghan war. . . .

Petraeus has spent relatively little time in Washington over the past decade and doesn't have as much experience with managing budgets or running Washington bureaucracies as CIA predecessors Leon E. Panetta and Michael V. Hayden. But Petraeus has quietly lobbied for the CIA post, drawn in part by the chance for a position that would keep him involved in the wars in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq and Yemen.

It's rare for American media outlets to list all of our "wars" this way, including the covert ones (and that list does not even include the newest one, in Libya, where drone attacks are playing an increasingly prominent role as well). But Barack Obama does indeed preside over numerous American wars in the Muslim world, including some that he started (Libya and Yemen) and others which he's escalated (Afghanistan and Pakistan). Because our wars are so often fought covertly, the CIA has simply become yet another arm of America's imperial war-fighting machine, thus making it the perfect fit for Bush and Obama's most cherished war-fighting General to lead (Petraeus will officially retire from the military to take the position, though that obviously does not change who he is, how he thinks, and what his loyalties are).

One reason why it's so valuable to keep the CIA under civilian control is because its independent intelligence analyst teams often serve as one of the very few capable bureaucratic checks against the Pentagon and its natural drive for war. That was certainly true during the Bush years when factions in the CIA rebelled against the dominant neocon Rumsfeld/Wolfowitz/Feith clique, but it's been true recently as well:

Others voiced concern that Petraeus is too wedded to the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq -- and the troop-heavy, counterinsurgency strategy he designed -- to deliver impartial assessments of those wars as head of the CIA.

Indeed, over the past year the CIA has generally presented a more pessimistic view of the war in Afghanistan than Petraeus has while he has pushed for an extended troop buildup.

That's why, noted The Post, there is "some grumbling among CIA veterans opposed to putting a career military officer in charge of an agency with a long tradition of civilian leadership." But if one thing is clear in Washington, it's that neither political party is willing or even able to stand up to the military establishment, and especially not a General as sanctified in Washington circles as Petraeus. It's thus unsurprising that "Petraeus seems unlikely to encounter significant opposition from Capitol Hill" and that, without promising to vote for his confirmation, Sen. Feinstein -- who raised such a ruckus over the appointment of Hayden -- yesterday "signaled support for Petraeus."

The nomination of Petraeus doesn't change much; it merely reflects how Washington is run. That George Bush's favorite war-commanding General -- who advocated for and oversaw the Surge in Iraq -- is also Barack Obama's favorite war-commanding General, and that Obama is now appointing him to run a nominally civilian agency that has been converted into an "increasingly militarized" arm of the American war-fighting state, says all one needs to know about the fully bipartisan militarization of American policy. There's little functional difference between running America's multiple wars as a General and running them as CIA Director because American institutions in the National Security State are all devoted to the same overarching cause: Endless War.

* * * * *

I'm excited to be speaking tonight at FAIR's 25th anniversary event in New York, along with Noam Chomsky, Amy Goodman and Michael Moore. The event, which begins at 7:00 p.m., is sold out, but will be live-streamed in its entirety here.

April 27, 2011

FBI serves Grand Jury subpoena likely relating to WikiLeaks

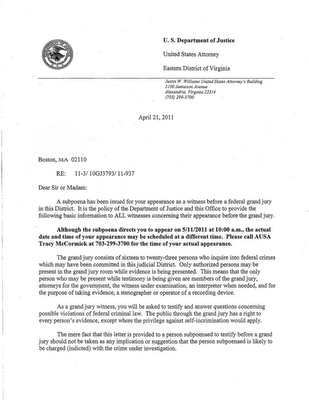

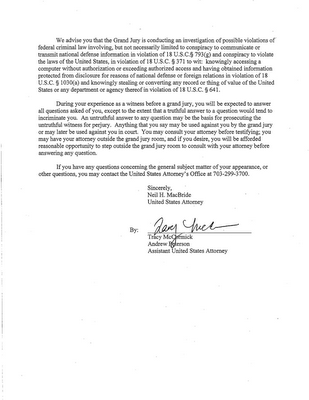

In the wake of a massive disclosure of Guantanamo files by WikiLeaks, the FBI yesterday served a Grand Jury subpoena in Boston on a Cambridge resident, compelling his appearance to testify in Alexandria, Virgina. Alexandria is where a Grand Jury has been convened to criminally investigate WikiLeaks and Julian Assange and determine whether an indictment against them is warranted. The individual served has been publicly linked to the WikiLeaks case, and it is highly likely that the Subpoena was issued in connection with that investigation.

Notably, the Subopena explicitly indicates that the Grand Jury is investigating possible violations of the Espionage Act (18 U.S.C. 793), a draconian 1917 law under which no non-government-employee has ever been convicted for disclosing classified information. The most strident anti-WikiLeaks politicians -- such as Dianne Feinstein and Newt Gingrich -- have called for the prosecution of the whistle-blowing group under this law, and it appears that the Obama DOJ is at least strongly considering that possibility.

The investigation appears also to focus on Manning, as the Subpoena indicates the Grand Jury is investigating parties for "knowingly accessing a computer without authorization" -- something that seems to refer to Manning -- though it also cites the conspiracy statute, 18 U.S.C. 371, as well as the conspiracy provision of the Espionage Act (subsection (g)), suggesting that they are investigating those who may have helped Manning obtain access. The New York Times previously reported that the DOJ hoped to build a criminal case against WikiLeaks and Assange by proving they conspired with Manning ahead of time (rather than merely passively received his leaked documents). Also cited is 18 U.S.C. 641, which makes it a crime to "embezzle, steal, purloin, or knowingly convert . . any record, voucher, money, or thing of value of the United States."

The serving of this Subpoena strongly suggests that the DOJ criminal investigation into WikiLeaks and Assange continues in a serious way; perhaps it was accelerated as a result of this latest leak, though that's just speculation. It also appears clear that the DOJ is strongly considering an indictment under the Espionage Act -- an act that would be radical indeed for non-government-employees doing nothing other than what American newspapers do on a daily basis (and have repeatedly done in partnership with WikiLeaks). The Subpoena is here; the two page letter accompanying the Subpoena are below (click on images to enlarge):

April 26, 2011

Strong anti-American sentiment in Egypt

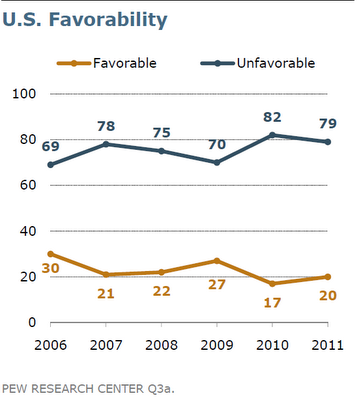

One of the central promises of the Obama presidency was that it would "restore America's standing" -- both in the world generally and the Muslim world specifically. In 2008, Andrew Sullivan famously wrote that Obama's face, by itself, would transform how the world perceives of the U.S. for the better: a not unreasonable expectation at the time ("What does he offer? First and foremost: his face. Think of it as the most effective potential re-branding of the United States since Reagan."). It's certainly true that Western Europeans view the U.S. more favorably now than they did during the Bush years (as do other nations who have benefited from his policies, such as India), but there's no evidence that there's been any such improvement in the Middle East, and ample evidence that there hasn't been.

Public opinion in Egypt is very instructive -- and troubling -- in this regard. Americans cheered in consensus for the democratic rebellion against the Mubarak regime. But most Egyptians aren't cheering for America, which long supported that regime until the very end. A new Pew poll was just released -- the first taken since the fall of Mubarak -- and its findings were summarized by today's Washington Post:

Egyptians are deeply skeptical about the United States and its role in their country . . . according a poll released Monday by the Pew Global Attitudes Project. Most Egyptians distrust the United States and want to renegotiate their peace treaty with Israel, the poll found. . . .

The poll found that 39 percent of Egyptians believe the U.S. response to the upheaval in Egypt was negative, almost double the 22 percent who said it was positive. . . .

Egyptian attitudes toward the United States more generally stayed about the same between 2010 and 2011 -- with just 20 percent holding a favorable opinion of the United States this year, an increase of three percentage points from 2010, and 79 percent holding an unfavorable opinion, a decrease of three percentage points.

More Egyptians -- 64 percent -- said they had low or no confidence in President Obama in 2011 than they did last year, up five percentage points.

What's most remarkable about that 20/79 favorability disparity toward the U.S. is that it's worse now than it was during the Bush years (a worldwide Pew poll of public opinion found a 30% approval rating in Egypt for the U.S. in 2006 and 21% in 2007). In one of the most strategically important countries in that region -- a nation that has been a close U.S. ally for decades -- public opinion toward the U.S. is as low as (if not lower than) ever, more than two years into the Obama presidency. Consider the recent Egyptian public opinion history toward the U.S.:

Those findings are even more striking given that Obama chose Cairo as the venue for what was to be his 2009 transformative speech to the Muslim world. Yet at least in Egypt, perceptions of the U.S. are as negative as ever.

It's not hard to see why; the crux of Obama policy -- steadfast support for compliant dictators, endless war-making, blind loyalty to Israeli desires -- is what has long generated intense anti-American sentiment in that part of the world. It's no surprise, then, that the closest U.S. ally who long served as the nation's Vice President and whom the Obama administration tried to empower -- Omar Suleiman -- is now the most unpopular Egyptian politician after Mubarak, with 66% having an unfavorable opinion of him.

Most remarkable about this new polling data is the huge gap between the views of the Arab dictators we prop up and the Arab citizenry generally: the reason why the U.S., despite its lofty rhetoric, wants anything but democracy in that part of the world. Consider, for instance, that "54 percent [of Egyptians] want to annul the peace treaty with Israel, compared with 36 percent who want to maintain it." Moreover, "a majority of the country [62%] wants Egypt's laws to strictly follow the Koran"; 27% want the law to "follow the values and principles of Islam," while only 5% say the law should "not be influenced by the Koran." And Egyptians are divided in their support for "Islamic fundamentalists," with 31% supportive (1/3 more than have favorable views toward the U.S.). And polls have long shown that Arab citizens generally -- as opposed to their unelected tyrants -- view the U.S. and Israel as far greater threats to world peace than any Iranian nuclear program.

In an article this week for Tom Dispatch, re-published by Salon, Noam Chomsky wrote:

The U.S. and its Western allies are sure to do whatever they can to prevent authentic democracy in the Arab world. To understand why, it is only necessary to look at the studies of Arab opinion conducted by U.S. polling agencies. . . . They reveal that by overwhelming majorities, Arabs regard the U.S. and Israel as the major threats they face: the U.S. is so regarded by 90% of Egyptians, in the region generally by over 75%. Some Arabs regard Iran as a threat: 10%. Opposition to U.S. policy is so strong that a majority believes that security would be improved if Iran had nuclear weapons -- in Egypt, 80%. Other figures are similar. If public opinion were to influence policy, the U.S. not only would not control the region, but would be expelled from it, along with its allies, undermining fundamental principles of global dominance.

This is exactly what he was talking about: ongoing U.S. actions in that part of the world do little other than sustain -- and even intensify -- anti-U.S. sentiments. That makes democracy the least desirable form of government in those countries from the perspective of the U.S. Government (and it's why I was so skeptical of the claim that we were intervening in Libya for humanitarian reasons and, now, to help bring about regime change and democracy there: real democracy is generally the exact opposite of what the U.S. wants in that region).

Whatever else is true, it is simply a fact that -- with a handful of exceptions -- perceptions of the U.S. in the Muslim world are as negative as ever. One can debate how significant that is, but what is undebatable is that a central promise of the Obama presidency has failed to manifest there and, as a result, few things would more potently subvert U.S. policy in that region that the spread of democracy.

Glenn Greenwald's Blog

- Glenn Greenwald's profile

- 808 followers