Glenn Greenwald's Blog, page 108

August 18, 2011

Obama v. Bush on power over Congress

(updated below - Update II)

Scott Lemieux hauls out the presidency-is-weak excuse to explain away some of Obama's failures; I've addressed that theory many times at length before and won't repeat those points here, but this bit of historical revisionism, made in service of that excuse-making, merits a response:

I've asked this before, but since I've never received a decent answer let me ask again: for people who believe in the Green Lantern theory of domestic presidential power, how do you explain the near-total lack of major legislation passed during George W. Bush's second term, including a failure to even get a congressional vote on his signature initiative to privatize Social Security? He didn't give enough speeches? He wasn't ruthless enough? Help me out here.

Lemieux's strangely selective focus on Bush's second rather than first term is worth a brief comment. After all, the current President in question is in his first term, which would seem to make that period (when Bush dictated to a submissive Congress at will, including when Democrats controlled the Senate) the better point of comparison; moreover, by his second term, Bush was plagued by a deeply unpopular war, fatigue over his voice after so many years, and collapsed approval ratings, which explains his weakness relative to his first term. None of that has been true of Obama over the last two years. And Bush never enjoyed Congressional majorities as large as Obama had for his first two years.

But more to the point, to claim that there was a "near-total lack of major legislation passed during George W. Bush's second term" means Lemieux has either forgotten about numerous events during that period or has a very narrow definition of the word "major." There was, for instance, this:

That bill -- passed with substantial Democratic support -- basically legalized Bush's previously illegal warrantless domestic spying program and bestowed retroactive immunity on the entire telecom industry, which seems pretty "major" to me. So does this:

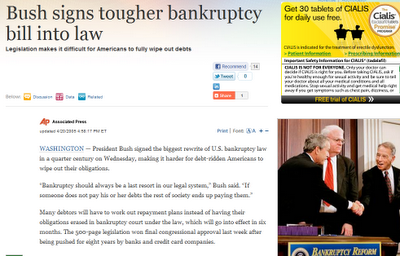

That bill, a huge boon to the credit card industry, strangled the ability of ordinary Americans to work their way out of debt, which also strikes me as quite "major." Then there's this:

That bill, a huge boon to the credit card industry, strangled the ability of ordinary Americans to work their way out of debt, which also strikes me as quite "major." Then there's this:

That's referring to the Military Commissions Act, enacted upon the demands of the Bush administration with substantial Democratic support; I trust I don't need to explain how "major" that was. There was also this:

Democrats babbled about the evils of the Patriot Act for years and then meekly submitted to Bush's demands that its key and most controversial provisions be renewed; that also seems "major." Just as significant was the legislation Bush prevented the Congress from passing, even when both houses were controlled by Democrats, such as this:

Given that the Democrats in the 2006 midterm election convinced the American people to hand them control of the Senate and House by promising to end the deeply unpopular war in Iraq, Bush's repeated success in blocking any such efforts -- accomplished by things such as steadfast, serious veto threats -- strikes me as a very "major" victory.

Given that the Democrats in the 2006 midterm election convinced the American people to hand them control of the Senate and House by promising to end the deeply unpopular war in Iraq, Bush's repeated success in blocking any such efforts -- accomplished by things such as steadfast, serious veto threats -- strikes me as a very "major" victory.

Granted, Bush's success on Iraq falls into the foreign rather than domestic realm, and some of the other examples are hybrids (Patriot Act and domestic spying), but they illustrate the real power Presidents can exert over Congress. Moreover, this presidency-is-weak excuse is often invoked to justify Obama's failures in all contexts beyond purely domestic policy (e.g., closing Guantanamo and the war in Libya). And all this is to say nothing of the panoply of domestic legislation -- including Bush tax cuts, No Child Left Behind, and the Medicare D prescription drug entitlement -- that Bush pushed through Congress in his first term, or his virtually unrestrained ability to force Congress to confirm even his most controversial nominees, including when Democrats were in control of Congress.

That doesn't seem too weak or ineffectual to me: quite the opposite. In fact, so dominant was the Bush White House over Congress that Dan Froomkin, in 2007 -- when Democrats controlled both houses -- memorably observed: "Historians looking back on the Bush presidency may well wonder if Congress actually existed." In sum, nobody -- and I mean nobody -- was talking about how weak the presidency supposedly is before Barack Obama was inaugurated: neither in the domestic nor foreign policy realm. To the contrary, just a few years ago, the power of the Presidency was typically conceived of as far too robust, not too limited.

It is true, as Lemieux suggests, that Bush suffered some legislative defeats in his second term (three in particular), but even those defeats highlight critical points about Obama. Two of those defeats -- failure of immigration reform and the forced withdrawal of the Harriet Miers Supreme Court nomination -- happened not because a powerful Congress overrode him, but rather because his own right-wing base rose up and refused to accept those proposals on the ground that they so violently conflicted with their political values: imagine that! The other defeat -- Social Security privatization -- was a real defeat because that's a very difficult goal to achieve in American politics (The Third Rail), but Bush did everything possible to succeed (including frenzily touring the country for months with speeches making his case), which is how one knew that he really wanted that to happen. That's what Presidents do when they're genuinely committed to a goal rather than pretending to be.

In that regard, Lemieux, ironically, claims to be burning down a strawman even as he props up his own: a very common one among those making this weak-presidency excuse. Nobody -- and I mean nobody -- argues that Obama can impose without constraints whatever policy outcomes he wants (what Lemieux and many others deride as the "Green Lantern Theory"). That viewpoint is a non-existent caricature. Of course it's the case that Presidents sometimes fail even when they use all the weapons in their arsenal (as Bush did with Social Security privatization).

The critique of Obama isn't that he tries but fails to achieve certain progressive outcomes and his omnipotence should ensure success. Nobody believes he's omnipotent. The critique is that he doesn't try, doesn't use the weapons at his disposal: the ones he wields when he actually cares about something (such as the ones he uses to ensure ongoing war funding -- or, even more convincing, see the first indented paragraph here). That evidence leads to the rational conclusion that he is not actually committed to (or, worse, outright opposes) many of the outcomes which progressive pundits assume he desires.

That's why Paul Krugman has been pointing out over and over that Obama wasn't helplessly forced into an austerity mindset by an intransigent Congress but actually believes in it, that he wants severe cuts. Identically, the evidence is now overwhelming that the public option was excluded from the health care bill because Obama wanted that outcome and thus secretly negotiated it away with the insurance industry, not because Congress or the 60-vote requirement prevented it. Similarly, while Congress did enact legislation preventing the closing of Guantanamo, Obama never wanted to shut it down in any meaningful way, but simply move it (and its defining abuse: indefinite detention) a few thousand miles North to Illinois.

The criticism isn't that Obama tried but failed to stave off austerity policies, a public-option-free entrenchment of the private health insurance industry, the preservation of indefinite detention or similar "centrist"/right/corporatist policies; it's that his lack of fight against them (or his affirmative fight for them) shows he craves those outcomes (just as nobody forced him to continue the vast bulk of the Bush/Cheney Terrorism approach he (and most Democrats) once so vehemently denounced). And whatever else is true, claiming that George Bush was similarly "weak" in the face of Congress is revisionist in the extreme.

* * * * *

One last point: Lemieux's very literalist criticism of Vast Left's cartoon isn't exactly wrong -- it's a two-line cartoon that relies on caricature -- but its central point is accurate: there is a serious, obvious tension between, on the one hand, saying things like this to explain away Obama's failures, and then turning around and announcing that his re-election must be the overarching, supreme priority that outweighs and subordinates all other political concerns, both short- and long-term.

UPDATE: Elissar008 reminds me in comments that I neglected to include this:

[image error]

Bailing out Wall Street with $700 billion seems to be yet another "major" legislative accomplishment no matter how one might define that term.

UPDATE II: In comments, dgt004 notes another irony: "Bush's major failure during his second term was the inability to gut social security. However, Obama appears to be on the verge of doing so successfully." If that happens -- and it is a prime purpose of the Super Committee, since those eager to cut Social Security have long said it can happen only with a bipartisan, fast-tracked Commission -- we will undoubtedly hear the same claim: that a helpless Obama was tragically forced into accepting it by Congress. That Obama has said over and over -- in public -- that he desires and is fighting for exactly this outcome will not deter the proffering of that "weakness" excuse. It is strange indeed -- and revealing -- that some Obama supporters think the best way to defend him is by constantly emphasizing his weakness.

August 16, 2011

The misery of the protracted presidential campaign season

The 2012 presidential election is 15 months away. The first primary vote will not be cast until almost six months from now. Despite that, the political media are obsessed -- to the exclusion of most other issues -- with the cast of characters vying for the presidency and, most of all, with the soap opera dynamic among them. It is not a new observation that the American media covers presidential elections exactly like a reality TV show pageant: deeply Serious political commentators spent the last week mulling whether Tim P. would be voted off the island, bathing in the excitement of Rick P. joining the cast, and dramatically contemplating what would happen if Sarah P. enters the house. But there are some serious implications from this prolonged fixation that are worth noting.

First, the fact that presidential campaigns dominate news coverage for so long is significant in itself. From now until next November, chatter, gossip and worthless speculation about the candidates' prospects will drown out most other political matters. That's what happened in 2008: essentially from mid-2007 through the November, 2008 election, very little of what George Bush and Dick Cheney did with the vast power they wielded -- and very little of what Wall Street was doing -- received any attention at all. Instead, media outlets endlessly obsessed on the Hillary v. Giuliani showdown, then on the Hillary v. Barack psycho-drama, and then finally on the actual candidates nominated by their parties.

Obviously, at least in theory, presidential campaigns are newsworthy. But consider the impact from the fact that they dominate media coverage for so long, drowning out most everything else. A presidential term is 48 months; that the political media is transfixed by campaign coverage for 18 months every cycle means that a President can wield power with substantially reduced media attention for more than 1/3 of his term. Thus, he can wage a blatantly illegal war in Libya for months on end, work to keep U.S. troops in Iraq past his repeatedly touted deadline, scheme to cut Social Security and Medicare as wealth inequality explodes and thereby please the oligarchical base funding his campaign, use black sites in Somalia to interrogate Terrorist suspects, all while his Party's Chairwoman works literally to destroy Internet privacy -- all with virtually no attention paid.

Paradoxically, nothing is more effective in distracting citizenry attention away from events of genuine political significance than the protracted carnival of presidential campaigns. It's not merely the duration that accomplishes this, but also how it is conducted. Obviously, how the candidates brand-market themselves has virtually nothing to do with what they do in power; the 2008 Obama campaign, which justifiably won awards from the advertising industry for how it marketed its product (Barack Obama), conclusively proved that; or recall the 2000 George W. Bush's campaign vow for a "more humble" foreign policy.

But worse still is that the media coverage all but ignores even these pretenses of policy positions in lieu of vapid, trite, conventional-wisdom horse-race coverage -- who will be the next American Idol? -- that virtually all ends up being worthless. Over and over, commentary throughout 2007 fixated on the inevitability of Hillary and Giuliani, the death of McCain's GOP candidacy, and various other forms of trivial idiocies; now we are bombarded with identical forms of shallow, speculative chatter from self-proclaimed experts who know nothing and babble about the most ultimately irrelevant matters (as but one illustrative example, see this bit of prescient brilliance from Jonathan Bernstein in The Washington Post a mere three weeks ago, mocking as "silly" the notion that the Pawlenty campaign was in trouble ("It's time to buy Tim Pawlenty stock. . . . He remains a very viable candidate in a field without many of them"); then once Pawlenty dropped out a mere 22 days later, Bernstein went to his blog to proclaim it "no great surprise"). That's the cheap, easy, empty, accountability-free, trivial punditry nonsense -- called "coverage of the presidential campaign" -- that swamps political discourse for a full year-and-a-half.

* * * * *

But coverage of these presidential campaigns has even more pernicious effects than mere distraction. They are also vital in bolstering orthodoxies and narrowing the range of permitted views. Few episodes demonstrate how that works better than the current disappearing of Ron Paul, all but an "unperson" in Orwellian terms. He just finished a very close second to Michele Bachmann in the Ames poll, yet while she went on all five Sunday TV shows and dominated headlines, he was barely mentioned. He has raised more money than any GOP candidate other than Romney, and routinely polls in the top 3 or 4 of GOP candidates in national polls, yet -- as Jon Stewart and Politico's Roger Simon have both pointed out -- the media have decided to steadfastly pretend he does not exist, leading to absurdities like this:

[image error]

And this:

[image error]

There are many reasons why the media is eager to disappear Ron Paul despite his being a viable candidate by every objective metric. Unlike the charismatic Perry and telegenic Bachmann, Paul bores the media with his earnest focus on substantive discussions. There's also the notion that he's too heterodox for the purist GOP primary base, though that was what was repeatedly said about McCain when his candidacy was declared dead.

But what makes the media most eager to disappear Paul is that he destroys the easy, conventional narrative -- for slothful media figures and for Democratic loyalists alike. Aside from the truly disappeared former New Mexico Governor Gary Johnson (more on him in a moment), Ron Paul is far and away the most anti-war, anti-Surveillance-State, anti-crony-capitalism, and anti-drug-war presidential candidate in either party. How can the conventional narrative of extremist/nationalistic/corporatist/racist/warmongering GOP v. the progressive/peaceful/anti-corporate/poor-and-minority-defending Democratic Party be reconciled with the fact that a candidate with those positions just virtually tied for first place among GOP base voters in Iowa? Not easily, and Paul is thus disappeared from existence. That the similarly anti-war, pro-civil-liberties, anti-drug-war Gary Johnson is not even allowed in media debates -- despite being a twice-elected popular governor -- highlights the same dynamic.

It is true, as Booman convincingly argues, that "the bigfoot reporters move like a herd" and "put[ their] fingers on the scales in elections all the time." But sometimes that's done for petty reasons (such as their 2000 swooning for George Bush's personality and contempt for Al Gore's); in this case, it is being done (with the effect if not intent) to maintain simplistic partisan storylines and exclude important views from the discourse.

However much progressives find Paul's anti-choice views to be disqualifying (even if the same standard is not applied to Good Democrats Harry Reid or Bob Casey), and even as much as Paul's domestic policies are anathema to liberals (the way numerous positions of Barack Obama ostensibly are: war escalation, due-process-free assassinations, entitlement cuts, and whistleblower wars anyone?), shouldn't progressives be eager to have included in the discourse many of the views Paul uniquely advocates? After all, these are critical, not ancillary, positions, such as: genuine opposition to imperialism and wars; warnings about the excesses of the Surveillance State, executive power encroachments, and civil liberties assaults; and attacks on the one policy that is most responsible for the unjustifiable imprisonment of huge numbers of minorities and poor and the destruction of their families and communities: Drug Prohibition and the accompanying War to enforce it. GOP primary voters are supporting a committed anti-war, anti-surveillance candidate who wants to stop imprisoning people (dispropriationately minorities) for drug usage; Democrats, by contrast, are cheering for a war-escalating, drone-attacking, surveillance-and-secrecy-obsessed drug warrior.

The steadfast ignoring of Ron Paul -- and the truly bizarre un-personhood of Gary Johnson -- has ensured that, yet again, those views will be excluded and the blurring of partisan lines among ordinary citizens on crucial issues will be papered over. That's precisely the opposite effect that a healthy democratic election would produce.

* * * * *

Perhaps the worst outcome of the protracted obsession with presidential campaigns is how it intensifies partisan tribalism, and bolsters divisions among ordinary Americans who have far more in common than differences. I recall a conversation I had early on in the Obama presidency with a civil libertarian; at the time, progressives were rarely critical of the new President, but because civil liberties was the very first area where he so blatantly embraced Bush policies and revealed how he truly operates, that was the one area where harsh criticisms were somewhat common. I suggested in that conversation that the trend of progressive criticism of Obama would be expressed by an inverted "U": it would continuously increase as the Real Obama revealed himself in more and more areas of prime importance to progressives, and then would decline precipitously -- more or less back to its original levels -- as the 2012 election approached. I think that's being roughly borne out.

Because presidential elections are such a stark either/or affair, many people feel compelled to choose one side and then elevate its victory into the overarching -- even the only -- political priority that matters. For that reason, even those willing to criticize their own side's Leader a couple of years before the election become unwilling to do so as the election approaches, on the ground that nothing matters except boosting one's own team and undermining the other. That, in turn, further reduces the already-low levels of independence, intellectual honesty, and -- most importantly -- accountability for those in power.

Those depressing, destructive trends are exacerbated by the manipulative fear-mongering that drives these campaigns. Every four years, The Other Side is turned into the evil spawn of Adolf Hitler and Osama bin Laden. Each and every election cycle, each party claims that -- unlike in the past, when Responsible Moderates ruled and the "crazies" and radicals were relegated to the fringes (the Democrats were once the Party of Truman!; Ronald Reagan was a compromising moderate!) -- the other party has now been taken over by the extremists, making it More Dangerous Than Ever Before. That the Other Side is now ruled by Supreme Evil-Doers means that anything other than full-scale fealty to their defeat is viewed as heresy. Defeat of the Real Enemy is the only acceptable goal. Election-time partisan loyalty becomes the ultimate Litmus Test of whether you're on the side of Good: it's the supreme With-Us-or-With-the-Terrorists test, and few are willing to endure the punishments for failing it. It's an enforcement mechanism for Party loyalty that -- by design -- breeds slavish partisan fealty.

None of this has anything to do with reality. For as long as I can remember, Republicans -- every election cycle -- have insisted that the Democratic Party has "now become more radical than ever," while Democrats insist that the GOP has now -- for the first time ever! -- been taken over by the extremists. That was what was said when Ronald Reagan was nominated in 1980 and then appointed people like Ed Messe, James Watt, and Robert Bork; it's what was said with the rise of the Moral Majority and Pat Robertson's 1988 second-place finish in the Iowa caucus (ahead of Vice President George H.W. Bush); it's what was said of the 1994 Contract with America and the Gingrich-led GOP's impeachment of Bill Clinton, and was repeated after Pat Buchanan's 1992 "culture and religious war" Convention speech in Houston and again after Buchanan's 1996 victory in the New Hampshire primary; and it's what was said repeatedly throughout the Bush/Cheney presidency.

Yes, some of the leading GOP presidential candidates (Bachmann, Perry) are truly extreme -- -but no more so than was Pat Robertson, Newt Gingrich, Dick Cheney, or (in his own way) Pat Buchanan. Jesse Helms was the Chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and all but threatened Bill Clinton's life. The GOP is extreme now and has been extreme for 30 years. The "Tea Party" is little more than a rebranding of conservatism in the post-Bush age. That they're MORE EXTREME THAN EVER!! is a fear-mongering slogan -- hauled out every four years -- to cause Democrats to forget about, or willfully ignore, their own leader's glaring, gaping failures.

The reality is that both parties' voters, early on in the process, like to flirt with candidates who present themselves as ideologues, but ultimately choose establishment-approved, establishment-serving functionaries perceived as electable (e.g., the Democrats' 2004 rejection of Dean in favor of Kerry, the GOP's 2008 embrace of the "maverick" McCain). In those rare instances when they nominate someone perceived as outside the establishment mainstream (Goldwater, McGovern), those candidates are quickly destroyed. The two-party system and these presidential campaigns are virtually guaranteed -- by design -- to produce palatable faces who perpetuate the status quo, placate the citizenry, and dutifully serve the nation's most powerful factions.

They can have some differences -- they'll have genuinely different views on social issues and widely disparate cultural brands (the urbane, sophisticated, East Coast elite intellectual v. the down-home, swaggering, Southern/Texan evangelical) -- but the process ensures a convergence to establishment homogeneity. The winner-takes-all, Most-Important-Election-Ever hysteria that precedes it masks that reality, creating the illusion of fundamentally stark choices. That's what makes the 18 months of screeching, divisive, petty, trivial rancor so absurd, so distracting, so distorting. Yes, it matters in some important ways who wins and sits in the Oval Office chair, but there are things that matter much, much more than that -- all of which are suffocated into non-existence by the endless, mind-numbing election circus.

* * * * *

In cartoon form, Vast Left summarizes much progressive discourse on these matters over the past two years:

[image error]

August 15, 2011

Pakistani belief about drones: perceptive or paranoid?

Two weeks ago, President Obama's former Director of National Intelligence, Adm. Dennis Blair, excoriated the White House for its reliance on drones in multiple Muslim nations, pointing out, as Politico put it, that those attacks "are fueling anti-American sentiment and undercutting reform efforts in those countries." Blair said: "we're alienating the countries concerned, because we're treating countries just as places where we go attack groups that threaten us." Blair has an Op-Ed today in The New York Times making a similar argument with a focus on Pakistan, though he uses a conspicuously strange point to make his case:

Qaeda officials who are killed by drones will be replaced. The group's structure will survive and it will still be able to inspire, finance and train individuals and teams to kill Americans. Drone strikes hinder Qaeda fighters while they move and hide, but they can endure the attacks and continue to function.

Moreover, as the drone campaign wears on, hatred of America is increasing in Pakistan. American officials may praise the precision of the drone attacks. But in Pakistan, news media accounts of heavy civilian casualties are widely believed. Our reliance on high-tech strikes that pose no risk to our soldiers is bitterly resented in a country that cannot duplicate such feats of warfare without cost to its own troops.

Though he obviously knows the answer, Blair does not say whether this widespread Pakistani perception about civilian casualties is based in fact; if anything, he insinuates that this "belief" is grounded in the much-discussed affection which Pakistanis allegedly harbor for fabricated anti-American conspiracy theories. While the Pakistani perception is significant unto itself regardless of whether it's accurate -- the belief about drones is what fuels anti-American hatred -- it's nonetheless bizarre to mount an anti-drone argument while relegating the impact of civilian deaths to mere "belief," all while avoiding informing readers what the actual reality is. Discussions of the innocent victims of American military violence is one of the great taboos in establishment circles; that Blair goes so far out of his way to avoid discussing it highlights how potent that taboo is.

Last month, I interviewed Chris Woods of the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, which had just published a report conclusively documenting the falsity of John Brennan's public claim that "in the last year, 'there hasn't been a single collateral death'" from U.S. drone attacks. Last week, the Bureau published an even more detailed report focusing on the number of Pakistani children killed by American drone attacks:

The Bureau has identified credible reports of 168 children killed in seven years of CIA drone strikes in Pakistan's tribal areas. These children would account for 44% of the minimum figure of 385 civilians reported killed by the attacks. . . .

The highest number of child deaths occurred during the Bush presidency, with 112 children reportedly killed. More than a third of all Bush drone strikes appear to have resulted in the deaths of children. . . . President Obama, too, has been as Commander-in-Chief responsible for many child deaths in Pakistan. The Bureau has identified 56 children reported killed in drone strikes during his presidency . . . .

The report indicates that the number of Pakistani children dying from drone attacks has decreased substantially over the past several months -- since September, 2010, when one man's son, two daughters and nephew were all killed by a single U.S. strike -- but such deaths nonetheless continue (including one in April of this year, in which a 12-year-old boy, Atif, was killed). These facts make John Brennan's blatant lie particularly disgusting: it's one thing to kill children using remote-controlled weaponized air robots in a country in which we're not formally at war, but it's another thing entirely to stand up in public and deny that it is happening.

[image error]

In several ways, the Bureau's study significantly understates the extent of U.S.-caused civilian deaths in the region. As Woods told me, the Bureau uses such a rigorous methodology -- counting civilian deaths only when they can be definitively confirmed up to and including the victims' names -- that some deaths almost certainly go uncounted in the notoriously inaccessible Waziristan region. Other credible reports provide an even starker assessment of the number of innocents killed. Moreover, this latest report from the Bureau counts only child deaths, not those of innocent adult men and women in Pakistan, nor does it discuss the large number of civilian deaths from drones outside of Pakistan (Yemen, Libya, Somalia, Afghanistan, Iraq), nor the U.S.-caused deaths of civilians from means other than drones (such as the "amazing number" of innocents killed at checkpoints in Afghanistan).

[image error]

Adm. Blair's Op-Ed may have had a much greater impact had it included a discussion of these facts, rather than implying that the problem with American drone attacks is Pakistani paranoia. That's precisely why the Op-Ed -- like most discussions in establishment venues of this topic -- didn't include those facts.

* * * * *

Thanks so much to Yves Smith, Maz Hussain, and Mark Adomanis for providing such stimulating and enlightening discussions during my absence last week. Filling in for a writer is not easy, as I learned when I did it for Digby way back in early 2006, very soon after I began writing about politics. You try to maintain your own voice and focus while realizing that you're writing for someone else's readership with its own pre-existing set of interests and expectations. All three did a superb job of balancing those considerations and it made my week off more enjoyable knowing that excellent content was being provided. You can continue reading Yves at her Naked Capitalism blog, Maz on his blog and on Twitter, and Mark on his Forbes blog and on Twitter.

August 14, 2011

Why "business needs certainty" is destructive

By Yves Smith

If you read the business and even the political press, you've doubtless encountered the claim that the economy is a mess because the threat to reregulate in the wake of a global-economy-wrecking financial crisis is creating "uncertainty." That is touted as the reason why corporations are sitting on their hands and not doing much in the way of hiring and investing.

This is propaganda that needs to be laughed out of the room.

I approach this issue as as a business practitioner. I have spent decades advising major financial institutions, private equity and hedge funds, and very wealthy individuals (Forbes 400 level) on enterprises they own. I've run a profit center in a major financial firm and have have also operated a consulting business for over 20 years. So I've had extensive exposure to the dysfunction I am about to describe.

Commerce is all about making decisions and committing resources with the hope of earning profit when the managers cannot know the future. "Uncertainty" is used casually by the media, but when trying to confront the vagaries of what might happen, analysts distinguish risk from "uncertainty", which for them has a very specific meaning. "Risk" is what Donald Rumsfeld characterized as a known unknown. You can still estimate the range of likely outcomes and make a good stab at estimating probabilities within that range. For instance, if you open an ice cream store in a resort area, you can make a very good estimate of what the fixed costs and the margins on sales will be. It is much harder to predict how much ice cream you will actually sell. That is turn depends largely on foot traffic which in turn is largely a function of the weather (and you can look at past weather patterns to get a rough idea) and how many people visit that town (which is likely a function of the economy and how that particular resort area does in a weak economy).

Uncertainty, by contrast, is unknown unknowns. It is the sort of risk you can't estimate in advance. So businesses also have to be good at adapting when Shit Happens. Sometimes that Shit Happening can be favorable, but they still need to be able to exploit opportunities (like an exceptionally hot summer producing off the charts demand for ice cream) or disaster (like the Fukushima meltdown disrupting global supply chains). That implies having some slack or extra resources at your disposal, or being able to get ready access to them at not too catastrophic a cost.

So why aren't businesses investing or hiring? "Uncertainty" as far as regulations are concerned is not a major driver. Surveys show that the "uncertainty" bandied about in the press really translates into "the economy stinks, I'm not in a business that benefits from a bad economy, and I'm not going to take a chance when I have no idea when things might turn around."

The "certainty" they are looking for is concrete evidence that prevailing conditions have really turned. But with so many people unemployed, growth flagging in advanced economies, China and other emerging economies putting on the brake as their inflation rates become too high, and a very real risk of another financial crisis kicking off in the Eurozone, there isn't any reason to hope for things to magically get better on their own any time soon. In fact, if you look at the discussion above, we actually have a very high degree of certainty, just of the wrong sort, namely that growth will low to negative for easily the next two years, and quite possibly for a Japan-style extended period.

So why this finger pointing at intrusive regulations, particularly since they are mysteriously absent? For instance, Dodd Frank is being water down in the process of detailed rulemaking, and the famed Obamacare actually enriches Big Pharma and the health insurers.

The problem with the "blame the government" canard is that it does not stand up to scrutiny. The pattern businesses are trying to blame on the authorities, that they aren't hiring and investing due to intrusive interference, was in fact deeply entrenched before the crisis and was rampant during the corporate friendly Bush era. I wrote about it back in 2005 for the Conference Board's magazine.

In simple form, this pattern resulted from the toxic combination of short-termism among investors and an irrational focus on unaudited corporate quarterly earnings announcements and stock-price-related executive pay, which became a fixture in the early 1990s. I called the pattern "corporate dysmorphia", since like body builders preparing for contests, major corporations go to unnatural extremes to make themselves look good for their quarterly announcements.

An extract from the article:

Corporations deeply and sincerely embrace practices that, like the use of steroids, pump up their performance at the expense of their well-being...

Despite the cliché "employees are our most important asset," many companies are doing everything in their power to live without them, and to pay the ones they have minimally. This practice may sound like prudent business, but in fact it is a reversal of the insight by Henry Ford that built the middle class and set the foundation for America's prosperity in the twentieth century: that by paying workers well, companies created a virtuous circle, since better-paid staff would consume more goods, enabling companies to hire yet more worker/consumers.

Instead, the Wal-Mart logic increasingly prevails: Pay workers as little as they will accept, skimp on benefits, and wring as much production out of them as possible (sometimes illegally, such as having them clock out and work unpaid hours). The argument is that this pattern is good for the laboring classes, since Wal-Mart can sell goods at lower prices, providing savings to lower-income consumers like, for instance, its employees. The logic is specious: Wal-Mart's workers spend most of their income on goods and services they can't buy at Wal-Mart, such as housing, health care, transportation, and gas, so whatever gains they recoup from Wal-Mart's low prices are more than offset by the rock-bottom pay.

Defenders may argue that in a global economy, Americans must accept competitive (read: lower) wages. But critics such as William Greider and Thomas Frank argue that America has become hostage to a free-trade ideology, while its trading partners have chosen to operate under systems of managed trade. There's little question that other advanced economies do a better job of both protecting their labor markets and producing a better balance of trade—in most cases, a surplus.

The dangers of the U.S. approach are systemic. Real wages have been stagnant since the mid-1970s, but consumer spending keeps climbing. As of June, household savings were .02 percent of income (note the placement of the decimal point), and Americans are carrying historically high levels of debt. According to the Federal Reserve, consumer debt service is 13 percent of income. The Economist noted, "Household savings have dwindled to negligible levels as Americans have run down assets and taken on debt to keep the spending binge going." As with their employers, consumers are keeping up the appearance of wealth while their personal financial health decays.

Part of the problem is that companies have not recycled the fruits of their growth back to their workers as they did in the past. In all previous postwar economic recoveries, the lion's share of the increase in national income went to labor compensation (meaning increases in hiring, wages, and benefits) rather than corporate profits, according to the National Bureau of Economic Analysis. In the current upturn, not only is the proportion going to workers far lower than ever before—it is the first time that the share of GDP growth going to corporate coffers has exceeded the labor share.

And businesses weren't using their high profits to invest either:

Companies typically invest in times like these, when profits are high and interest rates low. Yet a recent JP Morgan report notes that, since 2002, American companies have incurred an average net financial surplus of 1.7 percent of GDP, which contrasts with an average deficit of 1.2 percent of GDP for the preceding forty years. While firms in aggregate have occasionally run a surplus, ". . . the recent level of saving by corporates is unprecedented. . . .It is important to stress that the present situation is in some sense unnatural. A more normal situation would be for the global corporate sector—in both the G6 and emerging economies—to be borrowing, and for households in the G6 economies to be saving more, ahead of the deterioration in demographics."

The problem is that the "certainty" language reveals what the real game is, which is certainty in top executive pay at the expense of the health of the enterprise, and ultimately, the economy as a whole. Cutting costs is as easy way to produce profits, since the certainty of a good return on your "investment" is high. By contrast, doing what capitalists of legend are supposed to do, find ways to serve customer better by producing better or novel products, is much harder and involves taking real chances and dealing with very real odds of disappointing results. Even though we like to celebrate Apple, all too many companies have shunned that path of finding other easier ways to burnish their bottom lines. and it has become even more extreme. Companies have managed to achieve record profits in a verging-on-recession setting.

Indeed, the bigger problem they face is that they have played their cost-focused business paradigm out. You can't grow an economy on cost cutting unless you have offsetting factors in play, such as an export led growth strategy, or an ever rising fiscal deficit, or a falling household saving rate that has not yet reached zero, or some basis for an investment spending boom. But if you go down the list, and check off each item for the US, you will see they have exhausted the possibilities. The only one that could in theory operate is having consumers go back on a borrowing spree. But with unemployment as high as it is and many families desperately trying to recover from losses in the biggest item on their personal balance sheet, their home, that seems highly unlikely. Game over for the cost cutting strategy.

And contrary to their assertions, just as they've managed to pursue self-limiting, risk avoidant corporate strategies on a large scale, so too have they sought to use government and regulation to shield themselves from risk.

Businesses have had at least 25 to 30 years near complete certainty -- certainty that they will pay lower and lower taxes, that they' will face less and less regulation, that they can outsource to their hearts' content (which when it does produce savings, comes at a loss of control, increased business system rigidity, and loss of critical know how). They have also been certain that unions will be weak to powerless, that states and municipalities will give them huge subsidies to relocate, that boards of directors will put top executives on the up escalator for more and more compensation because director pay benefits from this cozy collusion, that the financial markets will always look to short term earnings no matter how dodgy the accounting, that the accounting firms will provide plenty of cover, that the SEC will never investigate anything more serious than insider trading (Enron being the exception that proved the rule).

So this haranguing about certainty simply reveals how warped big commerce has become in the US. Top management of supposedly capitalist enterprises want a high degree of certainty in their own profits and pay. Rather than earn their returns the old fashioned way, by serving customers well, by innovating, by expanding into new markets, their 'certainty' amounts to being paid handsomely for doing things that carry no risk. But since risk and uncertainty are inherent to the human condition, what they instead have engaged in is a massive scheme of risk transfer, of increasing rewards to themselves to the long term detriment of their enterprises and ultimately society as a whole.

August 12, 2011

Iraq foots the bill for its own destruction

By Murtaza Hussain

When considering the premise of reparation being paid for the Iraq War it would be natural to assume that the party to whom such payments would be made would be the Iraqi civilian population, the ordinary people who suffered the brunt of the devastation from the fighting. Fought on the false pretence of capturing Saddam Hussein's nonexistent weapons of mass destruction, the war resulted in massive indiscriminate suffering for Iraqi civilians which continues to this day. Estimates of the number of dead and wounded range from the hundreds of thousands into the millions, and additional millions of refugees remain been forcibly separated from their homes, livelihoods and families. Billions of dollars in reparations are indeed being paid for the Iraq War, but not to Iraqis who lost loved ones or property as a result of the conflict, and who, despite their nation's oil wealth, are still suffering the effects of an utterly destroyed economy. "Reparations payments" are being made by Iraq to Americans and others for the suffering which those parties experienced as a result of the past two decades of conflict with Iraq.

Iraq today is a shattered society still picking up the pieces after decades of war and crippling sanctions. Prior to its conflict with the United States, the Iraqi healthcare and education systems were the envy of the Middle East, and despite the brutalities and crimes of the Ba'ath regime there still managed to exist a thriving middle class of ordinary Iraqis, something conspicuously absent from today's "free Iraq." In light of the continued suffering of Iraqi civilians, the agreement by the al-Maliki government to pay enormous sums of money to the people who destroyed the country is unconscionable and further discredits the absurd claim that the invasion was fought to "liberate" the Iraqi people.

In addition to making hundreds of millions of dollars in reparation payments to the United States, Iraq has been paying similarly huge sums to corporations whose business suffered as a result of the actions of Saddam Hussein. While millions of ordinary Iraqis continue to lack even reliable access to drinking water, their free and representative government has been paying damages to corporations such as Pepsi, Philip Morris and Sheraton; ostensibly for the terrible hardships their shareholders endured due to the disruption in the business environment resulting from the Gulf War. When viewed against the backdrop of massive privatization of Iraqi natural resources, the image that takes shape is that of corporate pillaging of a destroyed country made possible by military force.

Despite the billions of dollars already paid in damages to foreign countries and corporations additional billions are still being sought and are directly threatening funds set aside for the rebuilding of the country; something which 8 years after the invasion has yet to occur for the vast majority of Iraqis. While politicians and media figures in the U.S. make provocative calls for Iraq to "pay back" the United States for the costs incurred in giving Iraq the beautiful gift of democracy, it is worth noting that Iraq is indeed already being pillaged of its resources to the detriment of its long suffering civilian population.

The perverse notion that an utterly destroyed country must pay reparations to the parties who maliciously planned and facilitated its destruction is the grim reality today for the people Iraq. That there are those who actually bemoan the lack of Iraqi gratitude for the invasion of their country and who still cling to the pathetic notion that the unfathomable devastation they unleashed upon Iraqi civilians was some sort of "liberation" speaks powerfully to the capacity for human self-delusion. The systematic destruction and pillaging of Iraq is a war crime for which none of its perpetrators have yet been held to account (though history often takes[though history often takes time to be fully written] time to be fully written), and of which the extraction of reparation payments is but one component.

Murtaza Hussain blogs at Revolution by the Book and is on Twitter at @MazMHussain.

August 11, 2011

Income inequality is bad for rich people too

By Yves Smith

One of the major fights in the debt ceiling battle is how much top earners should contribute to efforts to close deficits. Australian economist John Quiggin makes an eloquent case as to why they need to pony up:

My analysis is quite simple and follows the apocryphal statement attributed to Willie Sutton. The wealth that has accrued to those in the top 1 per cent of the US income distribution is so massive that any serious policy program must begin by clawing it back.

If their 25 per cent, or the great bulk of it, is off-limits, then it's impossible to see any good resolution of the current US crisis. It's unsurprising that lots of voters are unwilling to pay higher taxes, even to prevent the complete collapse of public sector services. Median household income has been static or declining for the past decade, household wealth has fallen by something like 50 per cent (at least for ordinary households whose wealth, if they have any, is dominated by home equity) and the easy credit that made the whole process tolerable for decades has disappeared. In these circumstances, welshing on obligations to retired teachers, police officers and firefighters looks only fair.

In both policy and political terms, nothing can be achieved under these circumstances, except at the expense of the top 1 per cent. This is a contingent, but inescapable fact about massively unequal, and economically stagnant, societies like the US in 2010. By contrast, in a society like that of the 1950s and 1960s, where most people could plausibly regard themselves as middle class and where middle class incomes were steadily rising, the big questions could be put in terms of the mix of public goods and private income that was best for the representative middle class citizen. The question of how much (more) to tax the very rich was secondary – their share of national income was already at an all time low.

And the fares of the have versus the have-nots continue to diverge. A new survey found that 64% of the public doesn't have enough funds on hand to cope with a $1000 emergency. Wages are falling for 90% of the population. And disabuse yourself of the idea that the rich might decide to bestow their largesse on the rest of us. Various studies have found that upper class individuals are less empathetic and altruistic than lower status individuals.

This outcome is not accidental. Taxes on top earners are the lowest in three generations. Yet their complaints about the prospect of an increase to a level that is still awfully low by recent historical standards is remarkable.

Given that this rise in wealth has been accompanied by an increase in the power of those at the top, is there any hope for achieving a more just society? Bizarrely, the self interest of the upper crust argues in favor of it. Profoundly unequal societies are bad for everyone, including the rich.

First, numerous studies have ascertained that more money does not make people happier beyond a threshold level that is not all that high. Once people have enough to pay for a reasonable level of expenses and build up a safety buffer, more money does not produce more happiness.

But even more important is that high levels of income inequality exert a toll on all, particularly on health. Would you trade a shorter lifespan for a much higher level of wealth? Most people would say no, yet that is precisely the effect that the redesigning of economic arrangements to serve the needs at the very top is producing. Highly unequal societies are unhealthy for their members, even members of the highest strata. Not only do these societies score worse on all sorts of indicators of social well-being, but they exert a toll even on the rich. Not only do the plutocrats have less fun, but a number of studies have found that income inequality lowers the life expectancy even of the rich. As Micheal Prowse explained in the Financial Times:

Those who would deny a link between health and inequality must first grapple with the following paradox. There is a strong relationship between income and health within countries. In any nation you will find that people on high incomes tend to live longer and have fewer chronic illnesses than people on low incomes.

Yet, if you look for differences between countries, the relationship between income and health largely disintegrates. Rich Americans, for instance, are healthier on average than poor Americans, as measured by life expectancy. But, although the US is a much richer country than, say, Greece, Americans on average have a lower life expectancy than Greeks. More income, it seems, gives you a health advantage with respect to your fellow citizens, but not with respect to people living in other countries….

Once a floor standard of living is attained, people tend to be healthier when three conditions hold: they are valued and respected by others; they feel 'in control' in their work and home lives; and they enjoy a dense network of social contacts. Economically unequal societies tend to do poorly in all three respects: they tend to be characterised by big status differences, by big differences in people's sense of control and by low levels of civic participation….

Unequal societies, in other words, will remain unhealthy societies – and also unhappy societies – no matter how wealthy they become. Their advocates – those who see no reason whatever to curb ever-widening income differentials – have a lot of explaining to do.

It's easy to see how "big status differences" alone have an impact. The wider income differentials are, the less people mix across income lines, and the more opportunties there are for stratification within income groups. Thus a decline in income can easily put one in the position of suddenly not being able to participate fully or at all in one's former social cohort (what do you give up, the country club membership? the kids' private schools? the charities on which you give enough to be on special committees?). And lose enough of these activities that have a steep cost of entry but are part of your social life, and you lose a lot of your supposed friends. Making new friends over the age of 35 is not easy.

So a perceived threat to one's income is much more serious business to the well-off than it might seem to those on the other side of the looking glass. Loss of social position is a fraught business indeed.

Robert Frank has also pointed out that the issue is relative status. Changes that hit all members of a particular cohort more or less the same way does not disrupt the existing social order:

As psychologists have long known, individuals typically find belt-tightening painful. But recent psychological research suggests that if all in that group spent less in unison, their perceptions of their standard of living would remain essentially unchanged....

With less after-tax income, top earners also wouldn't be able to spend as much on cars or their children's weddings and coming-of-age parties. But why did they feel compelled to spend so much in the first place? In most cases, they simply wanted a car that felt spirited, or a celebration that seemed special. But concepts like "spirited" and "special" are inescapably relative: when others in your circle spend a lot, you must spend accordingly or else live with the disappointment that results from unmet expectations.

And the costs of living in more unequal societies extend beyond health, although that impact is particularly dramatic. If you look at broader indicators of social well being, you see the same finding: greater income inequality is associated with worse outcomes. From a presentation by Kate Pickett, Senior lecturer at the University of York and author of The Spirit Level, at the INET conference in 2010:

You might argue: Why do these results matter to rich people, who can live in gated compounds? If you've visited some rich areas in Latin America, particularly when times generally are bad, marksmen on the roofs of houses are a norm. Living in fear of your physical safety is not a pretty existence.

Japan, which made a conscious decision to impose the costs of its post bubble hangover on all members of society to preserve stability, has gotten through its lost two decades with remarkable grace. The US seems to be implementing the polar opposite playbook, and there are good reasons to think the outcome of this experiment will be ugly indeed.

The conservative press and Israel's "miracle"

By Mark Adomanis

The conservative press has, over the past several years, regularly touted Israel's "economic miracle."

Indeed, the "economic miracle" has become a full-fledged conservative talking point -- Israel's economic dynamism and pro-business posture supposedly sets the country apart not just from its backward and authoritarian neighbors, but even from "decadent" developed countries in Western Europe and North America. The current Israeli government is even more overtly right-wing in its economic approach than its forbearers, and is fervently convinced of the need for liberalization, lower taxes, deregulation, and the entire panoply of Washington-consensus neoliberalism.

I have no interest in writing a needlessly contrarian Slate-like article that would attempt to argue that, despite its appearance, Israel is actually a poverty-stricken backwater. Israel's economy has, of course, made significant and noteworthy progress -- it would be simply impossible to argue that Israel hasn't become a world leader in certain sectors such as robotics, biotechnology, and defense.

However, while it was writing its paeans to Israel's economic dynamism, the conservative press apparently never thought to ask what Israelis themselves thought about the "miracle" their country was undergoing. If they had, they might have discovered a vast well of long-simmering anger and rage of the sort that almost always seems to accompany the implementation of neoliberalism (concerns about low wages, increased inequality, a shrinking middle class, and rising costs of living).

These concerns have now exploded to the surface and hundreds of thousands of people have marched all throughout Israel to register their discontent with the current situation. As the Financial Times recently reported:

In a striking procession of strollers, young parents marched through Tel Aviv to demand better childcare. Dairy farmers, meanwhile, decided to flood a busy intersection with milk in an effort to highlight their low income.

The demands, too have grown. What started out as a protest against housing costs has morphed into calls for a sweeping overhaul of Israel's economy and society: the protesters want a new taxation system (lower indirect taxes, higher direct taxes), free education and childcare, an end to the privatisation of state-owned companies and more investment in social housing and public transport. There is talk of imposing price controls on basic goods and a broader desire to see an end to "neo-liberal" government policies.

As time has passed the protests have grown and, if anything, become even more radical in their demands. In a noteworthy, and slightly ominous, bit of political theatre activists recently placed a guillotine in the middle of the tent city that has served as a nexus for the protests. I highly doubt even the famously obtuse Netanyahu failed to understand the symbolism.

Now 300,000 people (an absolutely enormous figure for a country whose entire population is only 7.5 million) don't wake up in the morning and suddenly decide, "Rather than going to work, I'm going to live in a tent city for several weeks to protest the government's economic policies." The sort of discontent, frustration, and anger so clearly visible in the Israeli protests were there all along -- they were simply ignored because they were considered inconvenient and distasteful.

Now the impulse to ignore information that contradicts one's worldview is not purely the province of conservatives, but I am still astounded at the remarkably ham-handed way in which they go about advocating for their preferred policies. In practice, the only way that neoliberalism can actually work is if the bulk of the population doesn't become violently enraged at the inevitable iniquities. You would therefore expect advocates of neoliberalism to be extremely wary of the possibility of widespread discontent and to do something (even insincere half-measures) to attempt to head it off.

Yet the conservatives who so regularly touted Israel and its "miracle" economy will surely not lose a moment's sleep. They regularly touted the Baltics before they suffered some of the most shocking economic collapses in history and went right back to flacking for them the minute they stopped collapsing.

It's surely not a very shocking development to learn that the conservative media feels comfortable cutting a few corners, but it's always very entertaining to see their propaganda exposed for what it is. In the conservative telling of the story, average Israelis ought to be overjoyed at their material circumstances and should applaud the "world beating" success of their economic model. Yet, in reality, hundreds of thousands of Israelis are so enraged and desperate, so exasperated with the failures of their economy, that they have taken to the streets. How ungrateful the little people can be!

Lastly, as a takeaway: If the "free market" press starts relentlessly touting your country's economic model, head for the hills. Immediately. Having one's economic policies gain the full-throated support of the WSJ and National Review is an almost certain sign that apocalyptic social conflict, or full-scale economic collapse, is just around the corner.

Austerity and the roots of Britain's turmoil

By Murtaza Hussain

"There's going to be riots, there'll be riots." Less than a week before a police shooting in the North London neighbourhood of Tottenham triggered the worst social unrest to hit Britain in decades, these were the words of a young man predicting the effect of youth club closures on his community. While the wanton violence and destruction still occurring in London and other places within Britain has shocked the world, it has not been as much of a surprise to many UK residents who have been warning of growing anger and alienation within British society, especially among youth.

While the rioters have come from backgrounds which cut across lines of race and social status, in the broadest sense what most of them have in common is that they are young men from economically deprived parts of the country. While many individuals have rightly pointed out that much of the violence appears borne of opportunistic criminality, this does not address the observable correlation between lack of economic opportunity, cuts to social services and the attraction of engaging in these types of destructive behaviours. Not only does Britain have one of the highest violent crime rates in the European Union, its unemployment rate for those between the ages of 16-24 currently stands at 18%. As Matthew Goodwin, a politics professor at the University of Nottingham, explained to Forbes:

"There's income inequality, extremely high levels of unemployment between 16 and 24-year-olds and huge parts of this population not in education or training…there's a general malaise amongst a particular generation."

The idea that we must not earnestly try to understand these actions is not only counterproductive but potentially suicidal in the long term. Far from being an isolated incident, these riots are but the largest and most recent incident of unrest to rock Britain in recent years. Most unrest has taken the form of protest, and has come in response to increasingly stringent government austerity measures and a perceived push to dismantle the social welfare state which has historically provided affordable healthcare and education to British society. In response to plans in 2010 to end government subsidies to UK universities, a move which would triple the cost of university education for the average student and largely destroy the meritocratic ideal of class mobility through education, tens of thousands of young Britons took to the streets in sometimes violent protests that in many ways appear to have been the harbinger of the riots we are witnessing today. Indeed, just a few months ago over 250,000 thousand people protested in London over further proposed cuts to social services, which nevertheless went ahead as planned.

The Cameron government's five-year plan of austerity measures is in only its first year and has already resulted in massive cuts to public sector services such as affordable housing subsidies, job training and culture and sports programs. While this past week of rioting was triggered by a particular incident of violence, it can be observed to be part of a larger pattern of anger and frustration within British society. Government policies that have made circumstances increasingly difficult and often hopeless for those who live close to the margins of society are finally bearing results in the form of a huge number of disaffected, alienated youth without regard for the laws and norms of the country.

While the violence and destruction of property which have occurred this past week are intolerable and worthy of full-throated condemnation, anyone with an interest in maintaining social cohesion should pay heed to the demonstrable results of economic hardship coupled with cuts to social services. The United States has experienced incidents of domestic unrest, some of which have culminated in rioting, but nothing yet on a scale as widespread as what has been glimpsed in Britain in recent days. The current debt crisis and the resulting debate around cuts to government spending is a time to reflect on the serious, tangible, effects of cutting social services. While spending must be curbed, too often politicians make, for them, the easy decision of cutting support to those who are already the least enfranchised members of society. The past week's decision to cut subsidized loans to graduate students from the budget is a prime example of a short sighted policy which will save money in the short term but will be deleterious to long term social stability. Cutting off avenues of class mobility for young people is an excellent way to engender the type of anger on display in Britain this week.

When considering the actual premise of "national security," one would have to look at a country which has descended into widespread internal chaos as being "insecure." For all the money spent on aggressive wars against ill-defined enemies in obscure parts of the world, the most dangerous threat to the actual physical safety of individuals within a country remains from their fellow citizens given a breakdown of social cohesion. It is a sign of dangerously confused priorities that defense spending is considered to be a budgetary holy grail which must be left untouched when discussing cuts to overall spending; but deep cuts to social services which directly affect the lives of millions of Americans are considered fair game. Nothing is more of a threat to the safety of Americans than a social system which will produce a generation of angry, disaffected young people and give rise to the types of scenes Britons are witnessing today. The same ingredients exist in the U.S. that do in Britain; indeed the unemployment rate for young Americans is even higher than the U.K, currently standing at 25 percent.As Phillip Jackson, the founder of the Million Father March, said this week:

"In Chicago and other major American cities, the violent acts are singular and isolated. The violence in London has become collective and focused, but the underlying causes are the same, and as soon as American kids figure that out, we're in trouble."

This debt crisis and the spending decisions it entails may constitute a potentially pivotal moment for the future of the United States. Following the lead of Britain and systematically dismantling the social welfare system may one day result in scenes of rioting and domestic insurrection playing out in major American cities as they are in British ones today. Cutting vital social services in order to protect the massive expenditures required to maintain the national security state and to continue funding countless directionless wars would be an extremely fateful failure of leadership as well as imagination.

Had there been a terrorist attack in Britain this past week as opposed to social unrest, there would undoubtedly be a huge chorus of voices in the U.S. loudly extolling the necessity of maintaining and even increasing defence spending, but there has been no commensurate call for protecting social spending in order to avoid the danger of Britain-style unrest. Those seriously concerned with national security should awaken themselves to the fact that there is absolutely nothing safe or secure about soaking your country in gasoline by ignoring, and exacerbating, the plight of its most disenfranchised citizens. Eventually an event will come along to strike a match; at which time the meaning and utility of "national security" will quite viscerally move from the abstract to the concrete.

Murtaza Hussain blogs at Revolution by the Book and is on Twitter at @MazMHussain.

August 10, 2011

Why are Treasury prices rising after the S&P downgrade?

By Yves Smith

Despite the hysteria that the downgrade of US debt would lead to US funding costs rising and Treasuries crashing, instead we've had stocks crashing and Treasury prices rising sharply. That's completely rational. The policies being implemented as a result of this contrived budget crisis are deflationary. For non-economists, as much as inflation has been touted as a major financial problem over the last 30 years, deflation is widely acknowledged to be Economic Enemy Number One. And high quality bonds like Treasuries are the place to be in deflation.

Deflation occurs when you have a falling level of prices and wages. Even though it isn't included in the Consumer Price index, the most important price in an economy is that of labor. We've had stagnant real worker wages over the last 30+ years, and from 2007 to 2009, IRS data shows that incomes fell 15% in real terms. Most of that is due to unemployment, but remember another pattern of the last decade: when seasoned workers lose jobs, when they find work again, it is often at much lower pay. Stagnant real wages are pretty much stagnant actual wages in a low inflation economy.

As many economists have recognized far too late is that increasing consumer debt levels is what enabled the US to fuel economic growth even with no real wage increases. Rising consumer debt is not a plus over the longer term, since consumers don't make productive investments from debt (the one supposed exception, that of borrowing to fund education, is misleading, since the rising borrowing has led to increased costs of education as well as more people getting graduate degrees that have more to do with credentialing than actual value to economic productivity, such as MBAs).

Since wages in aggregate are not growing, consumers are now trying to or being forced to delever, and the other ways to keep growth going (business investment and government spending) are very much absent or in retreat, the slack in demand can lead to stagnant or falling prices (that doesn't mean particular prices, like milk, won't rise, but the general price level will be flat or lower). That took place in the Great Depression and in a less extreme form, in Japan in its bubble aftermath. Deflation turns an economic downturn into a self-reinforcing spiral. Outstanding debt, which is usually too large to begin with, becomes crushing. The interest payments were set assuming positive inflation, so that the future interest payments and the principal would be paid back in cheaper dollars.

But in deflation, the reverse happens. With prices falling, cash is worth more in the future. That discourages consumers from spending, and means that paying off existing debt becomes harder and harder as incomes fall. The fall in spending as consumers and businesses delay purchases slows economic growth further, which makes the price fall accelerate, which increases the real cost of the debt burden.

Every country that has tried reining in government spending to deal with a debt overhang has only made matters worse. In Ireland, the GDP has contracted nearly 20% in nominal terms, making the debt to GDP ratio considerably worse. Latvia has had similar outcomes, and austerity is also leading to falling GDP in Greece, again making the country more, not less, insolvent.

Japan, which had a more massive bubble relative to the size of its economy in the late 1980s than the US did two decades later, had aggressive government spending through 1997, and barely kept the economy out of deflation. As soon as it tried balancing its budget, on the assumption the economy was now stable, growth promptly went into reverse and Yamaichi, one of the four biggest Japanese brokerage firms, failed.

The better approach with a debt hangover is to write down and restructure the debt that can't or probably won't be repaid. Those very same 1997 financial failures forced the Ministry of Finance to accept a more Darwinian model and allow more bank failures and restructurings. A 2009 recent Economist article stated that it has taken the banks 17 years to work off their bad debts. Not surprisingly, the Japanese told the US in uncharacteristically blunt terms twhen our crisis started, that the number one priority was cleaning up the financial system. Instead, we've copied Japan's mistakes.

But, but, but....you may protest...doesn't the US government have way too much debt? In short, no. Even the work of Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff, which is highly problematic in that it mixed gold standard countries with so-called "fiat" issuers like the US, found that government debt to GDP didn't hurt growth until it exceeded 90%. CBO projections show US debt to GDP before the debt reduction measures were put into motion stabilizing at around 77% as of 2015. (The Reinhart/Rogoff work is also at best a correlation. As occurred in this crisis, government debt to GDP levels rise sharply in the wake of financial crises. Financial crises also feature deep recessions in their aftermath. Thus in many cases, the low growth and high debt to GDP levels were caused by a criss rather than the debt levels causing the low growth).

A fiat issuer like the US can only default by choice. It can never run out of dollars to satisfy creditors (that is hot the case with US states or countries like Greece, which must borrow if they run budget deficits. The US does not need to sell bonds to finance its deficit, but we have kept debt issuance in place as a holdover from the gold standard era).

Some have tried arguing that S&Ps rating change was warranted due to inflation risk, but that's bunk too. The US experienced actual high inflation in the 1970s, and the dollar weakened then, yet the US was not downgraded by any of the ratings agencies.

The S&P downgrade looks to be politically motivated. The President had several routes by which he could have circumvented the debt ceiling restriction and almost certainly would have used one of them if the debt celling talks had dragged on so long that it became difficult to make interest payments out of tax receipts. McGraw Hill, which owns S&P, is headed by Terry McGraw, a prominent figure in the Business Roundtable, which has stated that it wants Social Security privatized. S&P has used its muscle to its advantage in the past, such as a state effort in Georgia in the early 2000s which would have reined in predatory lending and in turn reduced the issuance of private label mortgage backed securities. Rating them was a very profitable business for all the rating agencies. S&P torpedoed that initiative by refusing to rate bonds with Georgia loans in them. That forced Georgia to back down and killed other state efforts underway. Had these laws been in place, it is almost certain the subprime crisis would not have risen to a global-economy-wrecking event.

Austerian policies are sound medicine only when economies are strong. That isn't where we are now. Inducing an economic downturns when an economy is choked with private sector debt is very likely to produce near or actual deflation. Stocks perform badly. They are subject to low general prices with sharp rallies and declines, which favor brave and adept traders, but not ordinary investors. Riskier bonds shunned because they may be restructured or default. As much as S&P tried to diss Treasuries, it is has created conditions that make them a choice investment.

U.S. politicians' favorite terrorist group

By Murtaza Hussain

Given the supreme importance of the fight against terrorism and the terrible ramifications which ostensibly exist for providing material support to terrorists, it is puzzling to see prominent individuals within the U.S. political establishment openly lobbying for, and taking money from, an Iranian organization which is designated by the State Department as a terrorist group.

Mujahedin-e-Khalq (MEK) is an organization with a history of violent terrorism against Americans and others, and was a key strategic asset of Saddam Hussein during his brutal crackdown on Iraqi Kurds in the early 90's. Despite being implicated in the deaths of numerous American and Iranian civilians, (and being designated as a terrorist organization by countries around the world for its actions) U.S. political figures such as Ed Rendell, Andrew Card and John Bolton are openly advocating for MEK and are in many cases receiving significant sums of money for doing so.

Supporting designated terrorist organizations, especially in the context of the indefinitely ongoing War on Terror, is something for which a great number of individuals in the United States are currently serving lengthy prison sentences. It seems to defy logic then that members of MEK, a group which has attacked U.S. interests all over the world, are able to stroll the halls of Congress and exercise significant financial influence over U.S. government representatives in order to achieve their objectives. Make no mistake, the MEK is no less "terrorist" than any of the other groups for which one can go to jail for merely having contact with. In addition to openly acknowledging to have killed thousands of Iranians, MEK is directly implicated in the deaths of American civilians and military officials in Tehran during the 1970's, killings for which no MEK member has ever been brought to justice. As recently as 2007 the State Department had this to say about the organization which currently enjoys the open support of so many prominent figures within the U.S. political establishment:

"MEK leadership and members across the world maintain the capacity and will to commit terrorist acts in Europe, the Middle East, the United States, Canada, and beyond."

"MEK has also displayed cult-like characteristics…. members are also required to undertake a vow of "eternal divorce" and participate in weekly "ideological cleansings." Additionally, children are reportedly separated from parents at a young age. MEK leader Maryam Rajavi has established a "cult of personality."

"….. uses propaganda and terrorism to achieve its objectives and has been supported by reprehensible regimes, including that of Saddam Hussein."