Michael Marshall's Blog, page 2

March 3, 2023

Why I still think covid-19 probably originated in the wild, not in a lab

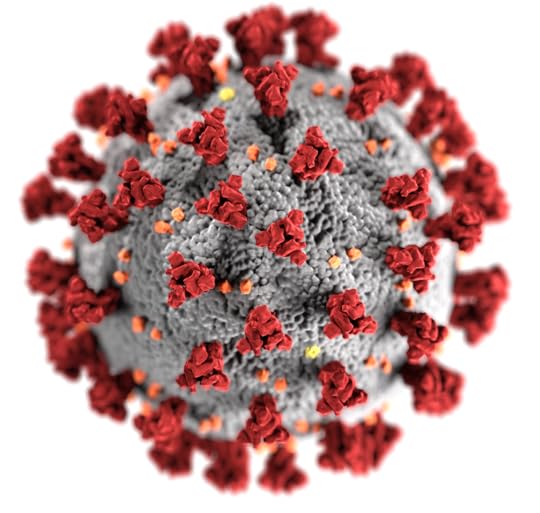

Credit: CDC / Alissa Eckert, MS; Dan Higgins, MAM Where did covid-19 come from?

Credit: CDC / Alissa Eckert, MS; Dan Higgins, MAM Where did covid-19 come from?TL:DR I thought back in early 2020 it probably had a natural origin, and despite all the attention given to the possibility of a lab leak, I still think the natural origin is most likely.

If you want to know why, read on.

There are four stages to this argument:

Why the evidence for a lab leak is weakWhy the evidence for a natural origin is strongHow to think about situations where a government might be lying to you, and conspiracy theories in generalWhat the origin of covid-19 means for our plans to prevent future pandemics

In the long-ago times of March 2020, I wrote a short story for New Scientist arguing that SARS-CoV-2 probably wasn’t engineered as a bioweapon and was more likely to have evolved in the wild: https://www.newscientist.com/definition/coronavirus-come-lab/

The story has since been updated by another writer, Graham Lawton, and I think it’s better for it. In particular, it does a better job of distinguishing two questions, which should be considered separately:

Was the virus engineered by humans?Did it get into the human population via a lab leak?

Let’s tackle them one by one.

First, most virologists will tell you that SARS-CoV-2 is not the product of bioengineering. That’s because its genome doesn’t contain any obvious signs of having been engineered.

You might argue that the engineering could have been done in a clever way that doesn’t leave any traces. Obviously, I can’t disprove that. But in that case I would want some form of evidence that this happened.

It’s been reported that the Wuhan Institute of Virology applied to do gain-of-function experiments. These are studies that would produce a new and dangerous virus, in order to study it and be prepared. They’re very controversial because they could potentially cause an outbreak.

However, the WIV applications were rejected. Of course, it’s possible that the experiments were done anyway, in secret. But again, where is the evidence of that?

Now let’s consider whether the virus got into the human population via a leak from the lab. In this scenario, the WIV collected SARS-CoV-2 from the wild but did a bad job of storing it. Again, there is no hard evidence that the WIV had SARS-CoV-2 in its collection until the virus started spreading.

At this point, many readers will baulk, and not unreasonably. “You keep saying there’s no evidence, but the Chinese government is secretive and covers things up!” is the retort.

This shouldn’t need saying, but clearly the Chinese government is not to be trusted. It’s authoritarian, secretive, and guilty of genocide against the Uyghurs.

However, it’s wrong to take that as evidence for the lab leak hypothesis. That’s because, whichever covid origin story turns out to be true, the Chinese government is at fault.

If the virus escaped from a government-run Chinese lab, that’s the government’s fault, e.g. for not being strict enough about biosecurity. Equally, if it originated in the wild animal trade, that’s also the Chinese government’s fault: they have been warned about the risk of disease outbreaks for years.

Set against this is the fact that diseases spill from animals to humans with depressing regularity, and the strong evidence that the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan was the epicentre of the pandemic

A study published in July 2022 found environmental traces of the virus in sections of the market where live covid-susceptible mammals were sold: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abp8715

This suggests there were animals in the market that had the virus, and that it passed to humans from them.

It’s possible to poke a few holes in that study: we don’t know what those animals were; maybe it was actually the vendor that was infected; maybe someone from the WIV had SARS-CoV-2 and went to the market.

But can you see how we’re having to fiddle around the edges of a body of evidence if we want to get away from an origin in the wildlife trade? Whereas the lab leak evidence is much more conjecture?

I find it useful to step back and think about conspiracy theories in general. How can we decide whether a conspiracy theory is likely to be true, or is just silly?

After all, conspiracies do happen. Watergate, COINTELPRO, Iran-Contra and the Rawalpindi conspiracy all really happened, but if they weren’t documented they could easily sound ludicrous and unbelievable.

Fortunately, there are some useful metrics we can use.

One is how many people have to be in on the secret. The more people are involved in the conspiracy, the more likely it is that the secret will get out: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0147905

This is one of the (many) reasons not to believe the Moon landings were faked: thousands of people would have to be in on it. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sE-tpiAiiHo

If SARS-CoV-2 was made in a lab, or leaked from a lab, quite a lot of people would know and I think we’d have heard from some of them by now.

However, in this case I think the crucial question is whether the evidence is direct or indirect.

When I say direct evidence, I mean something like the Watergate tapes in which you can hear Nixon and his allies conspiring to commit crimes. Or, to give a more contemporary example, Matt Hancock’s WhatsApp history.

In contrast, indirect evidence means facts that can be interpreted as suspicious, but could also just be random or innocuous.

The problem with indirect evidence is that if you look hard enough you’ll always find it, because the historical record is always messy. Plenty of people have pointed out over the years that truth is stranger than fiction, because fiction has to make sense: https://quoteinvestigator.com/2015/07/15/truth-stranger/

For instance, it’s been reported that some staff from the WIV went to hospital with respiratory infections in late 2019. That looks suspicious, right? Maybe they had covid-19!

Think about it for a minute. Autumn and winter are the times when respiratory viruses like influenza and RSV infect us all. Given how many people work at the WIV, it would be surprising if a few *didn’t* go to hospital with respiratory bugs every year.

If you could show that the number of WIV staff with respiratory illnesses was unusually high in late 2019, compared to previous years, that might be circumstantial evidence. But the fact that a handful of them were ill means nothing. It shouldn’t sway us at all, because it’s what would happen in a normal year.

This is the tricky thing about the lab leak hypothesis, and many other conspiracy theories. It’s possible to pile up lots of semi-suspicious details, like the people with the respiratory illness – and the accumulation of detail looks damning. But each piece of evidence is negligible, so all it is is a whole lot of nothing.

This does not mean I am dead set against a lab leak. A whistle-blower from the WIV could sway me, as could physical evidence from within the lab, or verifiable records of experiments. These would all constitute direct evidence that SARS-CoV-2 was there before the virus started spreading.

But in the absence of such direct evidence, I’ll continue to be swayed by the considerable evidence that the virus evolved naturally and started spreading among humans at the Huanan Market.

Finally, how important is this debate for deciding what to do to prevent future pandemics? I'd suggest, hardly at all.

We ought to review biosecurity protocols, but that's because those things ought to be reviewed on a regular basis anyway! It would also be good if labs like the WIV were more transparent, but again that would be true either way.

Meanwhile there's been thousands of disease outbreaks over the last 40 years and many of them came from animals. In the World Disasters Report 2022 that I wrote for the Red Cross (IFRC), I wrote:

“A 2014 study compiled 33 years of disease data from 1980 to 2013. This encompassed 12,102 outbreaks of 215 human infectious diseases. The researchers controlled for confounders such as improvements in disease surveillance. They found significant increases in the total number of outbreaks and in the diversity of diseases. In the early 1980s, there were fewer than 1,000 disease outbreaks per year, but by the late 2000s this had tripled to over 3,000. Bacteria and viruses caused 88% of the outbreaks. Similarly, zoonoses – diseases entering the human population from animals – were responsible for 56% of outbreaks (Smith et al, 2014).”

Here's that study, check it for yourself: https://doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2014.0950

And here’s the Red Cross report: https://www.ifrc.org/document/world-disasters-report-2022

Even if covid-19 is one of the estimated 44% of outbreaks that don’t originate in animals, that shouldn't sway us much. Zoonoses are still a major threat and we still need to take action to make them less likely. That needs a One Health approach, in which human and animal healthcare are integrated, e.g. doing joint surveillance for a disease in both humans and animals.

It would be slightly weird if we had hundreds of zoonoses that never quite turned into pandemics, and then the one lab leak incident did become a pandemic. But hey: sometimes history is weird. Nobody would believe the story of the Titanic if it weren’t demonstrably true.

The fact is, diseases that come from animals, and from other “obvious” sources like dirty water, are some of the biggest threats to our health. They’re also low-hanging fruit: we largely know how to prevent them, and the money spent would be paid back many times over in lives, productivity and happiness.

All of this was true before anybody had heard of covid-19, and it is still true now. The pandemic didn’t actually change our understanding of disease risks very much. What it ought to be is a call to arms, because I never want to have to go through anything like it again.

Published on March 03, 2023 02:12

January 30, 2023

The World Disasters Report 2022, of which I'm lead author, is out now

I spent much of 2022 working on the World Disasters Report for the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. We looked at what went right and wrong during the covid-19 pandemic and how to do better next time. And now the report is out, so here's a summary.

The impact of covid-19 has been staggering. About 1 person in every 1000 has died, all our lives have been changed, and the economy has taken a huge hit.

This happened because the vast majority of countries weren't prepared.

Some of this is obvious: limited stockpiles of masks, hospitals being run at capacity in "normal" times so there was no headroom when cases spiked, etc.

But it goes deeper. We weren't prepared because our governments neglected three crucial things.

Trust: if people trust each other and their governments, they will comply with public health measures, but governments often failed to build trust - especially with marginalised communities.

Equity: the poor and marginalised are the most vulnerable, so diseases both exploit inequities and make them worse. Being prepared means having a plan to handle inequities.

Local action: outbreaks begin in communities, so there has to be preparation at the local level. This allows responses to be tailored to community needs.

If we get those three things right, we'll be in a much better place when the next big bad disease turns up.

Read the World Disasters Report 2022.

World Disasters Report 2022: Trust, Equity and Local Action: Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic to avert the next global crisis (IFRC)

World Disasters Report 2022: Trust, Equity and Local Action: Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic to avert the next global crisis (IFRC)

The impact of covid-19 has been staggering. About 1 person in every 1000 has died, all our lives have been changed, and the economy has taken a huge hit.

This happened because the vast majority of countries weren't prepared.

Some of this is obvious: limited stockpiles of masks, hospitals being run at capacity in "normal" times so there was no headroom when cases spiked, etc.

But it goes deeper. We weren't prepared because our governments neglected three crucial things.

Trust: if people trust each other and their governments, they will comply with public health measures, but governments often failed to build trust - especially with marginalised communities.

Equity: the poor and marginalised are the most vulnerable, so diseases both exploit inequities and make them worse. Being prepared means having a plan to handle inequities.

Local action: outbreaks begin in communities, so there has to be preparation at the local level. This allows responses to be tailored to community needs.

If we get those three things right, we'll be in a much better place when the next big bad disease turns up.

Read the World Disasters Report 2022.

World Disasters Report 2022: Trust, Equity and Local Action: Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic to avert the next global crisis (IFRC)

World Disasters Report 2022: Trust, Equity and Local Action: Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic to avert the next global crisis (IFRC)

Published on January 30, 2023 02:50

March 8, 2022

BBC Earth: What is the point of saving endangered species?

This story was originally published on the BBC Earth website on 14 July 2015. Sadly the BBC Earth website has been deleted, so the original version of this story is now only available via the Wayback Machine.

I have reproduced it here, with notes highlighting passages in need of updating.

Many of the photos were licensed and are not included.

How much is all life on Earth worth? (Credit: NASA) In 1981, mountain gorillas were at rock-bottom. Confined to a small mountain range in central Africa, with humans encroaching on their habitat bringing poaching and civil war, their population was estimated at just 254. They would all have fitted into a single Boeing 747.

How much is all life on Earth worth? (Credit: NASA) In 1981, mountain gorillas were at rock-bottom. Confined to a small mountain range in central Africa, with humans encroaching on their habitat bringing poaching and civil war, their population was estimated at just 254. They would all have fitted into a single Boeing 747.

Today things look a little better. A survey in 2012 reported that the population was up to 880. That is a big improvement, but it's still only two Boeing 747s of mountain gorillas. They remain critically endangered.

[In 2018, the conservation status of mountain gorillas was upgraded to "Endangered", reflecting the growth in the population.]

We hear similar tales of woe all the time, from all around the world. Whether it's tigers, pandas, California condors or coral reefs, much of the world's wildlife is under threat. It's initially upsetting, and eventually just numbing.

Is it worth worrying about it all? Sure, it will be sad if there aren't any more cute pandas on the planet, but it's not like we depend on them. Besides, surely it's more important to take care of humans – who, let's face it, have their own problems to worry about – than to spend millions of dollars preserving animals. What, in short, is the point of conservation?

On the face of it, there are plenty of reasons why we shouldn't bother to save endangered species. The most obvious is the staggering cost involved.

One study in 2012 estimated that it would cost $76 billion (£49 billion) a year to preserve threatened land animals. Saving all the endangered marine species might well cost far more. Why should we spend all that money on wildlife when we could spend it to stop people dying of starvation or disease?

It can be particularly hard to understand why anyone would want to preserve animals like wolves, which pose a threat both to people and livestock. Surely there are some species we would be better off without.

Species go extinct all the time anyway. As well as individual species dying out, there have been five mass extinctions that obliterated swathes of species. The most recent one, 65 million years ago, took out the dinosaurs.

If extinction is a natural process that goes on even in the absence of humans, why should we stop it?

One answer is that species are now going extinct far faster than they used to. A recent study estimated that the extinction rate has increased a hundredfold over the last century, and we seem to be to blame.

But beyond that, there's a simple reason to save species: because we want to.

Many of us love the natural world. We think animals are cute, majestic, or just plain fascinating. We love walking in the dappled sunlight of an old forest, or scuba-diving over a coral reef. Who doesn't think mountain gorillas are awesome?

Nature is beautiful, and that aesthetic value is a reason to keep it, just as we preserve artistic masterpieces like the Mona Lisa or Angkor Wat.

The first problem with this argument is that it spells doom for all those animals and plants that people are less fond of: the ugly, the smelly and the just plain obscure. If we don't find them appealing, they're out.

More fundamentally, it comes from a position of luxury and privilege. It's all very well for a moneyed person in the western world to want to preserve tigers because they're nice to look at, but that doesn't cut much ice with a villager in rural India whose family is in danger from one.

So the fact that some of us find nature beautiful, by itself, won't do. There needs to be a more practical reason to keep species around.

You often hear it said that we should keep ecosystems like rainforests because they probably contain useful things, in particular medicines. The classic challenge is "what if a plant goes extinct that could be the cure for cancer?"

The practice of exploring nature to find commercially useful products is called bioprospecting. It does sometimes lead to useful new things, but it comes with a host of problems.

The first is that we have plenty of ways to find new medicines, which don't involve trekking through thousands of miles of dangerous jungle in the faint hope of finding a miracle plant.

There is also the matter of who controls the knowledge. Often, local people are already aware of the medicinal uses of plants, and object to outsiders trying to co-opt them. Legal battles have been fought over this.

And again, what happens to all the species that don't make useful things like medicines? The blood of mountain gorillas is unlikely to contain a cure for cancer. So this argument, while it has some force, doesn't get us very far.

The big leap forward came in the 1990s, when biologists started outlining all the ways animals and plants benefit us just by being there. These benefits, which most of us take for granted, are called "ecosystem services".

Some of these services are obvious. For instance, there are plants and animals that we eat. Meanwhile, photosynthetic plankton in the sea, and green plants, provide us with the oxygen we breathe.

These are quite direct, but sometimes the services provided can be more subtle. Pollinating insects like bumblebees are an obvious example.

Many of our crop plants rely on these insects to produce seeds, and would not survive – let alone provide us with food – without them. This is why the decline in pollinating insects has provoked so much concern.

To understand how much we rely on ecosystem services, imagine a world where humans are the only species – perhaps in a spaceship far from Earth.

There are no plants releasing oxygen, so you have to engineer a way to make it yourself. So straight away you need a chemical processing plant on board your ship. That same plant will have to make water too.

There is also nothing to eat, so you must artificially make food. You could synthesise chemicals like sugars and fats, but making it appetising would be extremely hard. As of 2015, we can't even make an artificial burger that everyone finds convincing.

Let's not even get started on the microorganisms living in your gut, many of which are beneficial. The point is that, while we could in theory do all these things artificially, it would be very difficult. It is far easier to let the existing wildlife do them for us.

The scale of these ecosystem services, when you add them up, turns out to be extraordinarily large.

In 1997, ecologist Robert Costanza and his colleagues estimated that the biosphere provides services worth around $33 trillion a year. For comparison, they noted that the entire global economy at the time produced around $18 trillion a year.

Five years later, the team took the argument a step further by asking how much we would gain by conserving biodiversity. They concluded that the benefits would outweigh the costs by a factor of 100. In other words, conserving nature is a staggeringly good investment.

By contrast, letting species decline and go extinct looks like a bad move. A 2010 study concluded that unchecked species loss would wipe 18% off global economic output by 2050.

You may perhaps be feeling that all this talk of economics and growth is strange. It's all rather cold and heartless, without any of the love for the natural world that we were talking about earlier. Well, many environmentalists feel the same way.

The environmentalist journalist George Monbiot has been a particularly vocal critic.

Monbiot argues that the valuations are unreliable, which allows those in power to rig the accounting however they see fit. If someone wants to build a road through an important habitat, they can simply overestimate the benefits of the road and downplay those from the wildlife.

"Forests, fish stocks, biodiversity, hydrological cycles become owned, in effect, by the very interests – corporations, landlords, banks – whose excessive power is most threatening to them," Monbiot wrote in 2013.

He may well be right that any such system would be open to abuse. The counter-argument is that without such a system, the abuse happens anyway – which is why many conservation groups now support putting a value on ecosystems.

In fact, one of the good things about the idea of ecosystem services is that it is all-encompassing. As a result, the weaker arguments we mentioned before now start to make some sense.

Take the idea that nature is beautiful and we should preserve it for its aesthetics and wonder. Our pleasure at the beauty of nature can now be thought of as an ecosystem service. Nature provides us with beauty.

You may well ask how we can put a price on that. How do you objectively measure beauty?

Well, you can't, but that doesn't stop us deciding what it's worth. We do it all the time with paintings, music and other forms of art. If we value something and are prepared to pay to have it, then it has value.

To do the same thing with nature, we just need a system that allows us to pay to experience it.

One simple example is safari holidays that take tourists to see mountain gorillas. This is called ecotourism.

The people running those holidays have a clear incentive to keep the animals safe. The gorillas are their livelihood, and running these tours may well pay better than other occupations like farming.

Of course, this idea has its difficulties. Tourists bring unfamiliar diseases with them, which can pose a threat to the gorillas – although facemasks can help. Too many visitors can also disrupt gorilla societies.

But in principle, ecotourism offers a way to make the beauty of nature pay for itself.

This sort of thinking turns our ideas about conservation on their heads, according to the conservation biologist Georgina Mace of University College London in the UK.

[Georgina Mace died on 19 September 2020]

Go back to the 1960s, and we were being told to preserve wildlife simply for its own sake. Mace calls this line of thinking "nature for itself".

Fast forward to the 2000s and we are now talking about "nature for people", thanks to the idea of ecosystem services. Even if you don't buy the moral argument that "wild things and places have incalculable intrinsic value", there are hard-nosed practical reasons to save them. You don't have to care about mountain gorillas to appreciate the value of a strong ecotourism industry.

Still, at first glance it does seem like the idea of ecosystem services should push us towards a rather selective approach to conservation. "Let's keep the things the tourists will go and see, and the things that pollinate our crops or otherwise make themselves useful, and the rest can go hang."

But there is another way of looking at it.

Let's consider the mountain gorillas. They live in a mountain range where the trees are covered with thick forests. If we want to preserve the gorillas, we also have to preserve the ecosystem they live in.

Some of this is obvious. The gorillas need plants to eat, so we must ensure those are there.

But we also can't let the area be overrun by inedible weeds. That in turn means keeping most of the other animals, as they will shape the plant community.

The mountain gorillas are part of a wider network of species, and it's difficult to separate them from it. Wiping out one of these species might not make much difference, or then again it might cause a chain reaction that alters the entire ecosystem. It's hard to predict the effect of killing off a species unless you go ahead and kill it – and then it's too late to reverse it.

So if we decide to save the mountain gorillas, by extension we are also choosing to preserve the particular habitat they live in and the majority of the species that live alongside them.

At this point many people balk. It's one thing to pay to save awesome mountain gorillas, they say, but now we have to pay out to save a bunch of trees, shrubs and insects too? Maybe those gorillas aren't such a good investment after all.

However, there are good reasons to keep the forests, and not just because they support the mountain gorillas.

Forests on hillsides provide a number of useful services that we don't always appreciate. In particular, they help ensure a regular water supply.

Everyone knows that the weather is changeable. Sometimes you get too much rain, which means floods. At other times there isn't enough, which means drought. Both are dangerous.

Trees on the hills help smooth this out, ensuring a more reliable supply of fresh water. This is good news for people living on the lowlands.

For this to really work, the forest needs to be reasonably stable. It's no use if it sometimes dies back suddenly just when really heavy rains come. It needs to be resilient.

Ecologists have amassed evidence that ecosystems with a wider range of species are more stable and resilient, and less prone to sudden die-backs. This has a startling implication. A tiny, obscure worm may not be doing anything that's obviously useful to humans, but it is probably supporting the ecosystem it lives in – and that ecosystem will be providing services.

Whether you put it in economic terms or not, science is telling us that ecosystems provide us with a host of things we can't do without, and that the more diverse each ecosystem is, the better.

So for our own good – both in terms of practical things like food and water, and less physical needs like beauty – we should protect them.

Of course, human society is part of the ecosystem too, and you won't find many people willing to get rid of us. As a result, many conservationists now say that we can't preserve nature without first figuring out how doing so will be good for humans, because any conservation scheme needs popular support.

Equally, we can't take care of ourselves without also preserving nature, because we need it for so many things. In specific situations we might choose to favour one or the other, but overall we have to do both.

This is a new way of thinking about conservation. It's not "nature for itself", because it's explicitly about helping people. It's also not quite "nature for people", because it's not just a matter of the direct goods that ecosystems offer us.

Instead it's about seeing human society and wild ecosystems as one inseparable whole. Mace has called this perspective "nature and people".

This doesn't mean preserving every last species, which we couldn't do even if we tried. It's also not about keeping things exactly the same, because that's impossible too.

But it does mean ensuring that ecosystems are as rich and diverse as possible. That will be good for them, and good for us.

I have reproduced it here, with notes highlighting passages in need of updating.

Many of the photos were licensed and are not included.

How much is all life on Earth worth? (Credit: NASA) In 1981, mountain gorillas were at rock-bottom. Confined to a small mountain range in central Africa, with humans encroaching on their habitat bringing poaching and civil war, their population was estimated at just 254. They would all have fitted into a single Boeing 747.

How much is all life on Earth worth? (Credit: NASA) In 1981, mountain gorillas were at rock-bottom. Confined to a small mountain range in central Africa, with humans encroaching on their habitat bringing poaching and civil war, their population was estimated at just 254. They would all have fitted into a single Boeing 747.Today things look a little better. A survey in 2012 reported that the population was up to 880. That is a big improvement, but it's still only two Boeing 747s of mountain gorillas. They remain critically endangered.

[In 2018, the conservation status of mountain gorillas was upgraded to "Endangered", reflecting the growth in the population.]

We hear similar tales of woe all the time, from all around the world. Whether it's tigers, pandas, California condors or coral reefs, much of the world's wildlife is under threat. It's initially upsetting, and eventually just numbing.

Is it worth worrying about it all? Sure, it will be sad if there aren't any more cute pandas on the planet, but it's not like we depend on them. Besides, surely it's more important to take care of humans – who, let's face it, have their own problems to worry about – than to spend millions of dollars preserving animals. What, in short, is the point of conservation?

On the face of it, there are plenty of reasons why we shouldn't bother to save endangered species. The most obvious is the staggering cost involved.

One study in 2012 estimated that it would cost $76 billion (£49 billion) a year to preserve threatened land animals. Saving all the endangered marine species might well cost far more. Why should we spend all that money on wildlife when we could spend it to stop people dying of starvation or disease?

It can be particularly hard to understand why anyone would want to preserve animals like wolves, which pose a threat both to people and livestock. Surely there are some species we would be better off without.

Species go extinct all the time anyway. As well as individual species dying out, there have been five mass extinctions that obliterated swathes of species. The most recent one, 65 million years ago, took out the dinosaurs.

If extinction is a natural process that goes on even in the absence of humans, why should we stop it?

One answer is that species are now going extinct far faster than they used to. A recent study estimated that the extinction rate has increased a hundredfold over the last century, and we seem to be to blame.

But beyond that, there's a simple reason to save species: because we want to.

Many of us love the natural world. We think animals are cute, majestic, or just plain fascinating. We love walking in the dappled sunlight of an old forest, or scuba-diving over a coral reef. Who doesn't think mountain gorillas are awesome?

Nature is beautiful, and that aesthetic value is a reason to keep it, just as we preserve artistic masterpieces like the Mona Lisa or Angkor Wat.

The first problem with this argument is that it spells doom for all those animals and plants that people are less fond of: the ugly, the smelly and the just plain obscure. If we don't find them appealing, they're out.

More fundamentally, it comes from a position of luxury and privilege. It's all very well for a moneyed person in the western world to want to preserve tigers because they're nice to look at, but that doesn't cut much ice with a villager in rural India whose family is in danger from one.

So the fact that some of us find nature beautiful, by itself, won't do. There needs to be a more practical reason to keep species around.

You often hear it said that we should keep ecosystems like rainforests because they probably contain useful things, in particular medicines. The classic challenge is "what if a plant goes extinct that could be the cure for cancer?"

The practice of exploring nature to find commercially useful products is called bioprospecting. It does sometimes lead to useful new things, but it comes with a host of problems.

The first is that we have plenty of ways to find new medicines, which don't involve trekking through thousands of miles of dangerous jungle in the faint hope of finding a miracle plant.

There is also the matter of who controls the knowledge. Often, local people are already aware of the medicinal uses of plants, and object to outsiders trying to co-opt them. Legal battles have been fought over this.

And again, what happens to all the species that don't make useful things like medicines? The blood of mountain gorillas is unlikely to contain a cure for cancer. So this argument, while it has some force, doesn't get us very far.

The big leap forward came in the 1990s, when biologists started outlining all the ways animals and plants benefit us just by being there. These benefits, which most of us take for granted, are called "ecosystem services".

Some of these services are obvious. For instance, there are plants and animals that we eat. Meanwhile, photosynthetic plankton in the sea, and green plants, provide us with the oxygen we breathe.

These are quite direct, but sometimes the services provided can be more subtle. Pollinating insects like bumblebees are an obvious example.

Many of our crop plants rely on these insects to produce seeds, and would not survive – let alone provide us with food – without them. This is why the decline in pollinating insects has provoked so much concern.

To understand how much we rely on ecosystem services, imagine a world where humans are the only species – perhaps in a spaceship far from Earth.

There are no plants releasing oxygen, so you have to engineer a way to make it yourself. So straight away you need a chemical processing plant on board your ship. That same plant will have to make water too.

There is also nothing to eat, so you must artificially make food. You could synthesise chemicals like sugars and fats, but making it appetising would be extremely hard. As of 2015, we can't even make an artificial burger that everyone finds convincing.

Let's not even get started on the microorganisms living in your gut, many of which are beneficial. The point is that, while we could in theory do all these things artificially, it would be very difficult. It is far easier to let the existing wildlife do them for us.

The scale of these ecosystem services, when you add them up, turns out to be extraordinarily large.

In 1997, ecologist Robert Costanza and his colleagues estimated that the biosphere provides services worth around $33 trillion a year. For comparison, they noted that the entire global economy at the time produced around $18 trillion a year.

Five years later, the team took the argument a step further by asking how much we would gain by conserving biodiversity. They concluded that the benefits would outweigh the costs by a factor of 100. In other words, conserving nature is a staggeringly good investment.

By contrast, letting species decline and go extinct looks like a bad move. A 2010 study concluded that unchecked species loss would wipe 18% off global economic output by 2050.

You may perhaps be feeling that all this talk of economics and growth is strange. It's all rather cold and heartless, without any of the love for the natural world that we were talking about earlier. Well, many environmentalists feel the same way.

The environmentalist journalist George Monbiot has been a particularly vocal critic.

Monbiot argues that the valuations are unreliable, which allows those in power to rig the accounting however they see fit. If someone wants to build a road through an important habitat, they can simply overestimate the benefits of the road and downplay those from the wildlife.

"Forests, fish stocks, biodiversity, hydrological cycles become owned, in effect, by the very interests – corporations, landlords, banks – whose excessive power is most threatening to them," Monbiot wrote in 2013.

He may well be right that any such system would be open to abuse. The counter-argument is that without such a system, the abuse happens anyway – which is why many conservation groups now support putting a value on ecosystems.

In fact, one of the good things about the idea of ecosystem services is that it is all-encompassing. As a result, the weaker arguments we mentioned before now start to make some sense.

Take the idea that nature is beautiful and we should preserve it for its aesthetics and wonder. Our pleasure at the beauty of nature can now be thought of as an ecosystem service. Nature provides us with beauty.

You may well ask how we can put a price on that. How do you objectively measure beauty?

Well, you can't, but that doesn't stop us deciding what it's worth. We do it all the time with paintings, music and other forms of art. If we value something and are prepared to pay to have it, then it has value.

To do the same thing with nature, we just need a system that allows us to pay to experience it.

One simple example is safari holidays that take tourists to see mountain gorillas. This is called ecotourism.

The people running those holidays have a clear incentive to keep the animals safe. The gorillas are their livelihood, and running these tours may well pay better than other occupations like farming.

Of course, this idea has its difficulties. Tourists bring unfamiliar diseases with them, which can pose a threat to the gorillas – although facemasks can help. Too many visitors can also disrupt gorilla societies.

But in principle, ecotourism offers a way to make the beauty of nature pay for itself.

This sort of thinking turns our ideas about conservation on their heads, according to the conservation biologist Georgina Mace of University College London in the UK.

[Georgina Mace died on 19 September 2020]

Go back to the 1960s, and we were being told to preserve wildlife simply for its own sake. Mace calls this line of thinking "nature for itself".

Fast forward to the 2000s and we are now talking about "nature for people", thanks to the idea of ecosystem services. Even if you don't buy the moral argument that "wild things and places have incalculable intrinsic value", there are hard-nosed practical reasons to save them. You don't have to care about mountain gorillas to appreciate the value of a strong ecotourism industry.

Still, at first glance it does seem like the idea of ecosystem services should push us towards a rather selective approach to conservation. "Let's keep the things the tourists will go and see, and the things that pollinate our crops or otherwise make themselves useful, and the rest can go hang."

But there is another way of looking at it.

Let's consider the mountain gorillas. They live in a mountain range where the trees are covered with thick forests. If we want to preserve the gorillas, we also have to preserve the ecosystem they live in.

Some of this is obvious. The gorillas need plants to eat, so we must ensure those are there.

But we also can't let the area be overrun by inedible weeds. That in turn means keeping most of the other animals, as they will shape the plant community.

The mountain gorillas are part of a wider network of species, and it's difficult to separate them from it. Wiping out one of these species might not make much difference, or then again it might cause a chain reaction that alters the entire ecosystem. It's hard to predict the effect of killing off a species unless you go ahead and kill it – and then it's too late to reverse it.

So if we decide to save the mountain gorillas, by extension we are also choosing to preserve the particular habitat they live in and the majority of the species that live alongside them.

At this point many people balk. It's one thing to pay to save awesome mountain gorillas, they say, but now we have to pay out to save a bunch of trees, shrubs and insects too? Maybe those gorillas aren't such a good investment after all.

However, there are good reasons to keep the forests, and not just because they support the mountain gorillas.

Forests on hillsides provide a number of useful services that we don't always appreciate. In particular, they help ensure a regular water supply.

Everyone knows that the weather is changeable. Sometimes you get too much rain, which means floods. At other times there isn't enough, which means drought. Both are dangerous.

Trees on the hills help smooth this out, ensuring a more reliable supply of fresh water. This is good news for people living on the lowlands.

For this to really work, the forest needs to be reasonably stable. It's no use if it sometimes dies back suddenly just when really heavy rains come. It needs to be resilient.

Ecologists have amassed evidence that ecosystems with a wider range of species are more stable and resilient, and less prone to sudden die-backs. This has a startling implication. A tiny, obscure worm may not be doing anything that's obviously useful to humans, but it is probably supporting the ecosystem it lives in – and that ecosystem will be providing services.

Whether you put it in economic terms or not, science is telling us that ecosystems provide us with a host of things we can't do without, and that the more diverse each ecosystem is, the better.

So for our own good – both in terms of practical things like food and water, and less physical needs like beauty – we should protect them.

Of course, human society is part of the ecosystem too, and you won't find many people willing to get rid of us. As a result, many conservationists now say that we can't preserve nature without first figuring out how doing so will be good for humans, because any conservation scheme needs popular support.

Equally, we can't take care of ourselves without also preserving nature, because we need it for so many things. In specific situations we might choose to favour one or the other, but overall we have to do both.

This is a new way of thinking about conservation. It's not "nature for itself", because it's explicitly about helping people. It's also not quite "nature for people", because it's not just a matter of the direct goods that ecosystems offer us.

Instead it's about seeing human society and wild ecosystems as one inseparable whole. Mace has called this perspective "nature and people".

This doesn't mean preserving every last species, which we couldn't do even if we tried. It's also not about keeping things exactly the same, because that's impossible too.

But it does mean ensuring that ecosystems are as rich and diverse as possible. That will be good for them, and good for us.

Published on March 08, 2022 09:15

October 7, 2021

The Genesis Quest reviewed by Adam Roberts

The Genesis Quest has been reviewed by science-fiction author Adam Roberts, on his blog Sibilant Fricative. You can read the full review here, but here's the opening paragraph:

The Genesis Quest has been reviewed by science-fiction author Adam Roberts, on his blog Sibilant Fricative. You can read the full review here, but here's the opening paragraph:"Usually I read books quickly, but this one took me a time, because each chapter is so full of toothsome detail: an expert's guided tour through the many and various scientists who have tried to answer the fundamental question, how did life arise on Earth? It's a question that entails a deeper one, ‘what is life, exactly?’ which Marshall does not shirk. The whole is written with wonderful clarity, occasional moments (especially in the footnotes) of nimble wit, and above all without cutting corners or skimming past any of its rich and fascinating narrative. I know a great deal more about crystals, cells, membranes, RNA, DNA and many other things now than I did before I read this."

I was particular excited about this one because I've been reading Roberts' books for many years. I read his early novels Salt, On and The Snow soon after they were published, and more recently I enjoyed The Thing Itself and have plans to read Purgatory Mount. I can't quite express how joyful it is when someone you've read reads you back, but it's peculiarly satisfying.

Towards the end of his review Roberts writes about consciousness, focusing on how it's seemingly a very recent phenomenon compared to the vast expanse of time for which life has existed on Earth. It so happens that a couple of days ago I gave a talk to Lichfield Science and Engineering Society about the origin of life, and afterwards an audience member asked me about consciousness. Specifically, they wanted to know what came first: life or consciousness?

The obvious answer is that life came first, that the simplest forms of life are wholly unconscious, and that consciousness is something that gradually emerged with the evolution of nervous systems and brains. Perhaps jellyfish have some sparse form of consciousness, but it's far more limited than ours.

This of course doesn't answer the famous "hard problem" of how consciousness can arise from non-conscious components. So some people instead argue for something called panpsychism: the idea that everything in the universe possesses a rudimentary form of consciousness and that in fact consciousness underpins everything. How, they ask, does a proton "know" that it's electromagnetically attracted to an electron, unless it's somehow conscious of it? A version of this idea is explored in Neal Stephenson's Baroque Cycle novels, beginning with Quicksilver. It's also there in Doctor Strange when the Ancient One says: "At the root of existence, mind and matter meet. Thoughts shape reality."

Intriguing as I find panpsychism, I'm dubious about it. I suspect the hard problem of consciousness is one of those things we just have to accept we can't solve. Most of the explanations I've seen for it seem to me to be (well-intentioned) tricks of language rather than true elucidations. There may be limitations to what we can know, and I think this might be one of them.

Published on October 07, 2021 05:53

August 19, 2021

August 6, 2021

A wonderful review of The Genesis Quest from The Inquisitive Biologist

Leon Vlieger, aka

The Inquisitive Biologist

, has posted a lovely review of

The Genesis Quest

. I hope he won't mind if I quote two passages that I particularly liked:

Leon Vlieger, aka

The Inquisitive Biologist

, has posted a lovely review of

The Genesis Quest

. I hope he won't mind if I quote two passages that I particularly liked:"Despite the serious intention, the book is very readable. He provides just the right amount of biographical information without losing focus on people's ideas. There is the occasional footnote with nerdy pop-culture references, which is amusing when used in moderation. And he can be refreshingly brusque and honest."

From now on, whenever someone accuses me of being blunt and rude, I'm going to tell them that I'm merely being refreshingly brusque and honest.

"Given that I have recently been reading a fair bit about astrobiology and the origin of life, this is the book I wish I had read first."

This quote made me very happy, because it hits on one of the reasons I wrote the book in the first place. Put simply, I wrote the book I wanted to read. After years of writing about the origin of life, I wanted an accessible guide to all the different ideas, one that would pit them against each other and critically assess them - as opposed to promoting one at the expense of the others, which is what a lot of journalism on the subject inevitably winds up doing due to space constraints. I wanted a one-stop shop, a book that would stand on its own as the only one you needed to read about how life began. I couldn't find one (though Adam Rutherford's Creation came close) - so I set out to write it, and here we are.

Read the full review on The Inquisitive Biologist.

Published on August 06, 2021 05:44

August 4, 2021

The Genesis Quest is out now in paperback

My first book

The Genesis Quest

is out in paperback in the UK today.

It's been a long hard road to get here: it turns out releasing your debut book in the middle of a society-upending pandemic is really quite difficult. But it's here now, the reviews are wonderfully positive, and I'm still very proud of it. I hope you all enjoy it.

You can get your copy from all good bookstores, but I'll particularly draw your attention to bookshop.org, where I have an actual page all of my very own. If you buy from there, I will earn a slightly higher percentage than if you buy elsewhere.

It's been a long hard road to get here: it turns out releasing your debut book in the middle of a society-upending pandemic is really quite difficult. But it's here now, the reviews are wonderfully positive, and I'm still very proud of it. I hope you all enjoy it.

You can get your copy from all good bookstores, but I'll particularly draw your attention to bookshop.org, where I have an actual page all of my very own. If you buy from there, I will earn a slightly higher percentage than if you buy elsewhere.

Published on August 04, 2021 16:00

April 16, 2021

Two new plaudits for The Genesis Quest

I have two pieces of good news about my book

The Genesis Quest

.

We learned in late March that it has been longlisted for the 2021 Hughes Prize. This is a biennial award given by the British Society for the History of Science, for "the best book in the history of science (broadly construed) published in English which is accessible to a wide audience of non-specialists". Previous winners include Andrea Wulf's The Invention of Nature, one of my favourite books of the last decade, so even to be longlisted is wonderful news. The shortlist will be announced in June 2021.

We also learned that materials scientist and broadcaster Mark Miodownik loved the book, and he has kindly gone on record saying: "This is an incredibly absorbing and insightful book about the most important scientific question of our age." Mark is a terrific science communicator so his good opinion of the book means a lot to me.

This is all very encouraging, as we're gearing up for a paperback edition later this year!

We learned in late March that it has been longlisted for the 2021 Hughes Prize. This is a biennial award given by the British Society for the History of Science, for "the best book in the history of science (broadly construed) published in English which is accessible to a wide audience of non-specialists". Previous winners include Andrea Wulf's The Invention of Nature, one of my favourite books of the last decade, so even to be longlisted is wonderful news. The shortlist will be announced in June 2021.

We also learned that materials scientist and broadcaster Mark Miodownik loved the book, and he has kindly gone on record saying: "This is an incredibly absorbing and insightful book about the most important scientific question of our age." Mark is a terrific science communicator so his good opinion of the book means a lot to me.

This is all very encouraging, as we're gearing up for a paperback edition later this year!

Published on April 16, 2021 04:02

April 14, 2021

Everything I've written about the covid-19 pandemic

I've written a lot of articles about the covid-19 pandemic, for a range of publications. To keep track of them all, I've started a long thread on Twitter.

I'll be doing a thread of my favourite articles this year, but first:

— Michael Marshall (@m_c_marshall) December 18, 2020

Everything I've written about #COVID19 #coronavirus

THREAD:

1/14 pic.twitter.com/cXVCwhW8oX

Published on April 14, 2021 06:39

February 4, 2021

Two new videos of me talking about how life on Earth began

Over the last few weeks I've released two new videos about the origin of life on Earth, as part of my ongoing virtual book tour to support

The Genesis Quest

.

If you'd like something short, I recorded a little YouTube video for my US publishers, the University of Chicago Press. It's part of their Author At Home series and you can watch it here, or embedded below. In it I explain what the book's about and what it says, and about how exploring the origin of life pushes at the boundaries of our knowledge.

Alternatively, if you'd like something a bit more in-depth, I gave an hour-long online talk to the Sidmouth Cafe Scientifique

If you'd like something short, I recorded a little YouTube video for my US publishers, the University of Chicago Press. It's part of their Author At Home series and you can watch it here, or embedded below. In it I explain what the book's about and what it says, and about how exploring the origin of life pushes at the boundaries of our knowledge.

Alternatively, if you'd like something a bit more in-depth, I gave an hour-long online talk to the Sidmouth Cafe Scientifique

Published on February 04, 2021 13:07