Pat Schneider's Blog, page 5

April 15, 2015

Ask Pat… What is the best way to learn how to write better poems?

Writers and leaders of writing groups, teachers of writing, and young writers are invited to write questions to Pat. She will choose one question each month for response. The questions may be edited, and will be anonymous, but if location and identity such as “Writer”, “Poet”, “Teacher”, or age of young writer is offered, that will be included. Offer a question: HERE

___________________________________________________________________

Q: What is the best way to learn how to write better poems?

A: First, let’s eliminate the worst possibilities. In my experience, the worst possible way is to join a class or workshop where the teacher’s or leader’s method is to show everyone what they did wrong, so go home and fix it. A good workshop , for example, using the Amherst Writers & Artists method ,will put praise for what is strong first in every response, giving the emerging poet a foundation of strength on which to offer suggestions that will help him or her to build increasing craft.

Another worst possibility is doing nothing but continuing to love only what you loved in childhood and youth, being unwilling to explore and learn from what is happening right now in the world of poetry.

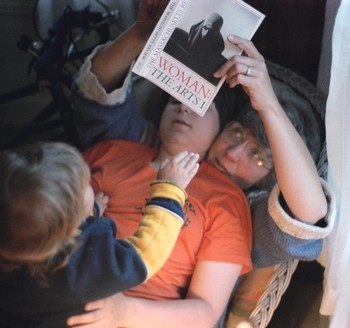

And a third not-so-good possibility is working entirely alone, with no good feedback, suggestion, encouragement, or praise. Family doesn’t count. Almost always, they care too much, know your material too well, have alternate views of your mutual history, and in short, get in the way of your progress. Best to wait for a published poem before sharing it with family members. Or if you must show them, tell them ahead of time you don’t want any opinions except what they love, because your poem is still a “cake in the oven” and with even a breath of cold air (criticism) it may fall.

Now, the good ways to learn. First, leave the old classics alone. What Wordsworth and Keats wrote in their lifetimes was fresh, new, interesting, and brave to their contemporaries. You already know their rhythms, their sentiments, their craft. Read poems written since you yourself became an adult. Go to the library and find your contemporary poets. Give each poet a chance by reading at least three poems by each author. Read the poems out loud, maybe walk around your room as you read, so your body as well as your ears and your mind enter the poem. Read each poem at least three times, listening to it, feeling it. Find in the anthology the poem you like the best, and let that poet become your teacher. Get more of his or her books. Try “copy-cat” poems, following the pattern exactly, but using different words, different images. If, for example, you are liking and copy-catting Wallace Stevens’ poem, “Fourteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird,” you might want to put a little epigraph at the top of your poem, lower-case, italicized, and in a small font, — after Wallace Stevens, to give credit for the form of the poem. If your form is different, as well as your content, you don’t have to give credit. You have made a new poem and it is your own, with a little “literary influence.” Now, do the same with a poem you don’t understand, or don’t like. What is that poet doing, and why? Could you use anything from that poet’s style?

Another important thing is not to work entirely alone. Find a writing partner who will meet with you regularly, or join a group, workshop, or class. The way to know whether what you have chosen is good for you is this simple “acid test.” First, give it a try a couple of times. Examine yourself after each meeting. Do you feel more like writing, or less like writing? If more, great. Do it again. If less, it is poison to you as a writer. Quit.

With your partner or group, follow the method described in my book, Writing Alone and With Others, or some other method that you invent or that you find elsewhere that is supportive of natural voice and encouraging to exploration. You don’t need a lot of authoritative “DO THIS” rules, or “DON’T DO THIS” limitations. (I know, I know, I gave you a few of both above!)

Last, and most important, I do believe that becoming a better poet — or any other kind of artist — is a lifetime process. Pablo Casals, perhaps the greatest cellist of the 20th century, began every day by playing all six Bach unaccompanied cello suites. He was asked, “Why do you play all six suites each day?” He said, “Because I think I’m getting better.” I am eighty now; childcare is far behind me, work as an administrator of Amherst Writers & Artists is a decade behind me. At last my artistic challenge is exactly what you state in your question. “How do I become a better poet?” By committing myself again every day to practice and to learn, so I can say, “I think I’m getting better.”

THERE IS ANOTHER WAY (SoulCollage)

Once, in a poem, I wrote “There is another way / to enter an apple. / A worm’s way.” I am finding another way to enter my writing. It allows me to go inside, through a door I didn’t even know was there, have a fresh experience, savor a new and delicious taste, surprise myself.

Once, in a poem, I wrote “There is another way / to enter an apple. / A worm’s way.” I am finding another way to enter my writing. It allows me to go inside, through a door I didn’t even know was there, have a fresh experience, savor a new and delicious taste, surprise myself.

Sometimes something goes “bump” in the mind. A hint, a tease, or an outright “smack upside the head” when you are trying with all your might to get into your writing. It takes practice to learn the difference between the inner chatter of writer’s block, and the gentle nudge of an idea trying to get in. The chatter is just annoying distraction. The nudge is a gift. Some writers call a magical moment of inspiration “the muse.” I like better the way Goethe understood it. He said, “When one is fully committed, Providence moves, too.” Some writers claim they receive dictation from some source beyond themselves. I have never felt that, although frequently I do feel assisted — by “Providence” or whatever — but only when I am in need, fully committed, and paying attention.

Life is crowded. I got up at 4:30 this morning to answer email that had piled up — more than 130 unanswered messages. Then, sleep deprived and groggy, I turned to my necessary writing task – to create a blog entry inviting readers to come to a workshop I will be leading with Sue Reynolds. I got a cup of coffee, curled up on the couch with my computer, and got nothing. Nada! I wanted to say something about the relation between visual and written art. Something about pictures and writing. But what? What?

The first nudge today was an issue of Smithsonian Magazine that had been lying around our living room for a week or more without attracting my attention. Its full page cover photo is of horses painted in a cave in France 30,000 years ago. They were visible to the artist only by firelight, yet the horses seem almost to dance, muscles rippling in the sun. Why did that prehistoric artist also trace around his or her own hand, leaving handprints that we try to “read” 30,000 years later?

Is it possible that visual art is also a language, and writing is also a visual art? As we read, do we not paint pictures on the cave walls of the mind? And was the cave artist not telling stories with his or her horses, his or her hand?

The second nudge came as I was finishing answering email. A friend had sent a passage from Frederick Buechner’s book, Whistling in the Dark, but I had been too busy to read it. He begins with a haiku poem by Basho:

“An old silent pond. / Into the pond a frog jumps. / Splash! Silence again.” It is perhaps the best known of all Japanese haiku. . . . Basho, the poet, makes no comment on what he is describing. He implies no meaning, message, or metaphor. He simply invites our attention to no more and no less than just this: the old pond in its watery stillness, the kerplunk of the frog, the gradual return of the stillness.

In effect he is putting a frame around the moment, and what the frame does is enable us to see not just something about the moment but the moment itself in all its ineffable ordinariness and particularity. The chances are that if we had been passing by when the frog jumped, we wouldn’t have noticed a thing or, noticing it, wouldn’t have given it a second thought. But the frame sets it off from everything else that distracts us. It makes possible a second thought. That is the nature and purpose of frames. The frame does not change the moment, but it changes our way of perceiving the moment. It makes us NOTICE the moment, and that is what Basho wants above all else. It is what literature in general wants above all else too.

From the simplest lyric to the most complex novel and densest drama, literature is asking us to pay attention. Pay attention to the frog. Pay attention to the west wind. Pay attention to the boy on the raft, the lady in the tower, the old man on the train. In sum, pay attention to the world and all that dwells therein and thereby learn at last to pay attention to yourself and all that dwells therein.

The painter does the same thing, of course. Rembrandt puts a frame around an old woman’s face. It is seamed with wrinkles. The upper lip is sunken in, the skin waxy and pale. It is not a remarkable face. You would not look twice at the old woman if you found her sitting across the aisle from you on a bus. But it is a face so remarkably seen that it forces you to see it remarkably just as Cezanne makes you see a bowl of apples or Andrew Wyeth a muslin curtain blowing in at an open window. It is a face unlike any other face in all the world. All the faces in the world are in this one old face.

“Putting a frame around the moment.” “Paying attention.” Buechner suggests that is what all art does – music, painting, writing. All at once I understood what Sue is helping me to do, and what I want to say about it

I have always, ever had only one art form: writing. The damage was done in a fourth grade classroom when a teacher told us to “draw night,” Then she walked up and down the aisles between rows of desks, stopped beside me, took my paper to the front of the classroom, held it up and said in a loud voice, “This is the way NOT to draw night!” Of course I didn’t hear another word. That was seventy years ago. I can still taste the shame on my tongue. And I still don’t know how to “draw night.”

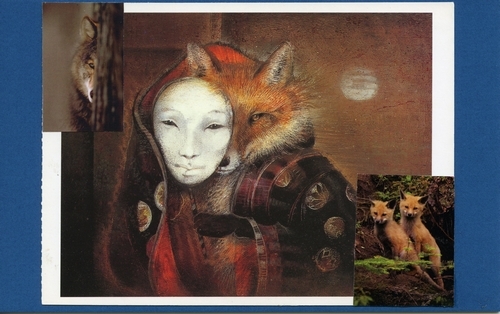

The SoulCollage card of foxes pictured here is one I made in the workshop we led together last summer. It is about my mother. Her complexity, her beauty, her fearsome wildness. The kits are my brother and myself. In making this “SoulCollage” I was able to express something wilder, stranger, and more beautiful, than I had ever expressed about Mama. Working silently looking for images, I found her, saw her more clearly, and began to write about her with a greater depth of understanding of what she gave me, as well as how she hurt me.

The SoulCollage card of foxes pictured here is one I made in the workshop we led together last summer. It is about my mother. Her complexity, her beauty, her fearsome wildness. The kits are my brother and myself. In making this “SoulCollage” I was able to express something wilder, stranger, and more beautiful, than I had ever expressed about Mama. Working silently looking for images, I found her, saw her more clearly, and began to write about her with a greater depth of understanding of what she gave me, as well as how she hurt me.

Flannery O’Connor, perhaps America’s greatest short story writer, too up drawing, she said, to help her see more clearly the images she was describing in her writing,

Sue is teaching me with SoulCollage another way to enter the apple of my poem. She and I will be cutting, pasting, and writing together in Amherst again in June with a dozen other people – we will write in my old farmhouse near the center of this college town, a short walk from Emily Dickinson’s home and grave. We will make collage cards in the “great hall” of a local Protestant church. We will eat sumptuous meals catered by the Black Sheep Deli. For more information, please go to THIS LINK.

March 17, 2015

WHAT I WANT TO SAY: How Writing in a Journal Helps a Writer Get There

What I want to say is . . .

Journal: March 13, 2015.

What I want to say. Often I don’t know, myself. This week is like that. Peter’s brother, Hank died; I, too, loved him deeply. And there’s been scary illness in my family. And there’s been demanding work that left me drained and exhausted. Now everyone has gone to the memorial service three thousand miles from here. I am home alone because my left hip and leg won’t allow me to sit for long flights. I want to write, but that desire fragments into a flock of wild birds that I can neither capture nor name. There are feelings, colors, images, but they fly as soon as I try to word them into captivity.

What I want to say. Often I don’t know, myself. This week is like that. Peter’s brother, Hank died; I, too, loved him deeply. And there’s been scary illness in my family. And there’s been demanding work that left me drained and exhausted. Now everyone has gone to the memorial service three thousand miles from here. I am home alone because my left hip and leg won’t allow me to sit for long flights. I want to write, but that desire fragments into a flock of wild birds that I can neither capture nor name. There are feelings, colors, images, but they fly as soon as I try to word them into captivity.

What I want to say is . . .

March 14, 2015. Journal.

I have created a small, separate journal.

It’s black, with a large black spiral that holds together the pages. It was given to me several years ago by someone who was leaving our town and as it turned out, our friendship. So the object itself holds love and pain. Spirals of both. I first started writing in it to record things I cannot explain and usually tell only to closest friends. The kinds of things I wrote about in a chapter called “Strangeness” in How the Light Gets In. Things that some people – and some parts of myself – want to dismiss as “coincidences,” et cetera. I have about ten pages of those – they are all joyful.

But the last few days have been the stuff that suggest images of hell – and so I turned the little journal upside down and backward and wrote there dreams, nightmares, and the events that created them.

What I want to say is . . .

March 14, 2015. Journal? Maybe something more than that . . .

A whiff of a poem just slid through, between my ears. But it, too, was a wild bird. The memorial service will begin in California in a few hours. Peter will play his clarinet, a gorgeous arrangement of “Simple Gifts” by ___________. Rain drips onto old snow outside my window. It makes a sad, grey music.

I have written my way toward wanting to say something about writing. Maybe this will turn into a blog entry or something. The dreams and nightmares I wrote about earlier today have become something other than what they were. They were deep sores, torn places in my psyche. They have moved out now to images I stand a bit back from, look at as if they are outside myself. Writing does that; once written, images are outside as well as inside.

Yes, this is a healing practice, this writing. Not only writing in a journal. One of the most “crafted” poems I ever wrote, “Letting Go,” in my book, Another River, which took me 37 complete drafts to finish because it rhymes at both ends of every line, (not always the first word on the left side) was profoundly healing to write. It is about leaving the church, leaving institutional religion entirely, after a small congregation had paid my way through college, rescuing me from poverty. Writing can be a healing practice. It can be a spiritual practice. And it is worthy of a lifetime of practice in learning more skill, for it can be an art form.

All of that. Now I will go make myself some lunch. Maybe these words will stay private, but I doubt it. The blog is a strange and wonderful new forum. As I write, and as the reader reads, we are friends.

Now I have said what I want to say.

(To hear Pat read her poem, “What I Want to Say,” please click here)

February 16, 2015

OF POEMS AND PRAISE

Poems are pouring out of me. It is as if they have been storing up behind some door, a door I left open only a crack while I wrote How the Light Gets In, and closed for a time of rest when I finished it. Now poems are coming. Lately, most of them have been about trouble.

I wish my work held a larger quotient of praise, but the truth is, trouble seems to be the key that opens the door for praise finally to come through.

There is a song in the African American Heritage Hymnal 169 that came to mind after I wrote that sentence:

Over my head, I see trouble in the air.

Over my head, I see trouble in the air.

Over my head, I see trouble in the air.

There must be a God somewhere!

The solitude I need for writing is mine to claim – every morning it waits for me in the dark before dawn. A single lamp beside my chair makes a small room of light in half a world of dark. It is a solitude so vast I can feel along the tiny hairs on the back of my neck, the presence. The Presence. And then I can write trouble. And then I can praise.

Who or what is the presence? When I walk out on the plank of that question, I am alone above a dark sea and below a sky full of stars. I don’t have to understand. I don’t need any name. The presence is felt, and is always intensely private.

Going backward in time, the presence takes remembered forms. When Peter left the ministry and we both left the practice of organized religion, and had no idea of how we would survive, (a story that I tell in my book, Wake Up Laughing,) there was Mrs. D’s black face, saying, “God makes a way out of no way!” When I was graduating from high school with no future but the lowest paying jobs, (a story I tell in How the Light Gets In,) there was Reverend Harris’ white face, saying, “We are going to send you to college.” When I was a five or six year old child after the storm of my mother’s divorce, there was a cyclone with no face at all, but with a breath that took away a country store across the gravel road where we lived in a rented farmhouse. It blew down four trees in our yard, one on each side of the house, each one’s top at the foot of the last, like a pencil drawing a line around the house without touching us.

After two years of not being able to do my work because of disability, I have accepted an invitation from Rowe Center to lead a weekend long “poetry party.” I want to do it – to play with poetry, write it with thirty other poets and persons who believe they cannot write poems but are brave enough to try.

I have had times of fear: can I do it? This is a time of trouble for me. Peter’s failing memory, and my left leg’s stubborn refusal to fully heal in the years since I broke the hip in a fall, are heavy challenges. But if I’m attentive, signs of grace are everywhere. The latest “synchronicity” that I take as a sign is a female cardinal at my desk-window birdfeeder whom I caught tipping, flapping one wing. I studied her and saw her lose her balance in a gust of wind. Out of her feathers, fluffed against this record-breaking storm of snow, shot a leg that had no foot. Her left leg. My left leg. A gracious sign: Observe her courage. Observe her determination to survive. Observe her beauty.

Any thing, any occurrence, any remembrance, can be suffused with presence if we are attentive. Observing the courage and endurance of one crippled, beautiful, softly red female cardinal feels a lot like being in the center of a half-written poem. And that state of being feels like praise.

__________________________

Listen to this month’s poem, posted February 15, 2015: “Truth Enough”

January 18, 2015

SAYING IT: I AM A POET!

One of the best things about being eighty years old is knowing who you will be when you grow up. I am a poet. Underneath all the teaching, underneath the two Oxford non-fiction books, in the scariest place, the tenderest place, the most joyful place inside me — I am a poet.

One of the best things about being eighty years old is knowing who you will be when you grow up. I am a poet. Underneath all the teaching, underneath the two Oxford non-fiction books, in the scariest place, the tenderest place, the most joyful place inside me — I am a poet.

When I was young, I thought the only real poets were the ones in books, and the very best poet in the world was T.S. Eliot. But one summer in the middle of my college years, I worked in a mission orphanage and school deep in the mountains of Appalachia. There was a cook in the school named Fanny Jane. She was missing two of her front teeth, and probably a good number of the back ones. One day she asked me, “Are there mountains where you live?”

I said, “No, but we do have hills.”

She looked up at Pine Mountain behind the orphanage and replied softly, “I don’t know what I’d do without mountains to rest my eyes against.”

And I knew, utterly knew, with a knowledge no teacher could ever take from me, that poets are everywhere. But even so, I did not dare to call myself “a poet.”

I have celebrated my truck-driver brother’s stories, I have loved the lyrics of good country-western poets (King of the Road,” “Jackson,” and the best of both white and black gospel lyrics. There are poets who drive Mack trucks deep in the night across this land. I’ve listened to poets in housing projects and jails, shy friends and bruised ex-Ph.D. students finding their way back to their own rich, beautiful, nuanced voices, children in detention writing finally the truth of what they see or what they imagine. Because the voice that begins in the fetus recognizing her mother’s voice, the voice that matures in the toddler for the first time saying a full sentence, already is musical. The cadence, the “minor fall, the major lift” as Leonard Cohen puts it.

I have celebrated my truck-driver brother’s stories, I have loved the lyrics of good country-western poets (King of the Road,” “Jackson,” and the best of both white and black gospel lyrics. There are poets who drive Mack trucks deep in the night across this land. I’ve listened to poets in housing projects and jails, shy friends and bruised ex-Ph.D. students finding their way back to their own rich, beautiful, nuanced voices, children in detention writing finally the truth of what they see or what they imagine. Because the voice that begins in the fetus recognizing her mother’s voice, the voice that matures in the toddler for the first time saying a full sentence, already is musical. The cadence, the “minor fall, the major lift” as Leonard Cohen puts it.

Those who know me well recognize that what I have said above is my theme. This is my story, / This is my song . . . But . . .

. . . something new is happening for me. I have fallen in love with a poet for the second time in my life. Christian Wiman. (Sorry, T.S., but after half a century it’s probably time.) I’m not alone in my love – in fact, I’m a late-comer of a whole flock. And it’s really just one poem of his, and his books about poetry that have me besotted. He says somewhere, and I will find it again; here I misquote – he says either in his book, Ambition and Survival: On Becoming a Poet, or in My Bright Abyss, that there are two kinds of poets. There are those who write many poems, write profusely, and there are those who hunger desperately to write just one perfect poem.

. . . something new is happening for me. I have fallen in love with a poet for the second time in my life. Christian Wiman. (Sorry, T.S., but after half a century it’s probably time.) I’m not alone in my love – in fact, I’m a late-comer of a whole flock. And it’s really just one poem of his, and his books about poetry that have me besotted. He says somewhere, and I will find it again; here I misquote – he says either in his book, Ambition and Survival: On Becoming a Poet, or in My Bright Abyss, that there are two kinds of poets. There are those who write many poems, write profusely, and there are those who hunger desperately to write just one perfect poem.

I know which kind he is, because he has written a perfect poem. It is an invented form of his own; the form is half of what I love. It is also a revelation, an example of writing as a spiritual practice. That’s the other half of what I love. The poem is “God Goes Belonging.”

That one poem is a miracle of form, of music, of intuitive knowledge and of mature theological thought. I want to be a good enough poet to be able to do that. I have memorized it. I have tried to copy-cat it and of course it can’t be copy-catted. The miracle lies in the fullness of the original creation – form as well as content. Music as well as intense exploration.

I am eighty years old. I am who I will be when I grow up. I am a poet.

I have written for a lifetime in my original voice, in what what John Wideman calls “the language of home.” My foundation is solid. But on that foundation (rather than the foundation of grammar, grading, and graphite corrections on our pages) there is this amazing, beautiful challenge: the possibility that our own music, the music we first heard in the womb, the music we have been making as we talk all of our lives – that very music might be the wine that we pour into new vessels – that we offer to the world in the chalice of forms that we ourselves have created or that we have received through the study of poets whose work we have come to love. I have collected shelf full of books I want to study. Christian Wiman and Kay Ryan and Emily Dickinson and Billy Collins, and . . .

At eighty I can say it; I am a poet, and I have chosen my teachers. At last, I am ready.

I do hope you will write poems with me in Rowe in March. Click here to read more about it.

Or you can go directly to the Rowe website to register by clicking here.

December 1, 2014

A TRICK… AND A TREAT

One wonderful thing about becoming an old woman is the revelation that there is always more revelation available. Lift the corner of the sheet on the bed, find a lost pajama piece, begin a fiction in your head: she is in a hotel room, morning has come, and revelation . . .

You are off into another, imagined life. That imagined life is a crazy-quilt of pieces, scraps of your own life, — a morning long ago when you lifted a bedcover, felt the air billow up under it, and made a major decision about your life. That, and where in the world did the hotel room come from?

I am reading Louise Penny’s mystery novel, A Trick of the Light, and she is teaching me something about my own writing. But let me back up and say that it was truly annoying to discover in April, 2013, that just as my book, How the Light Gets In, was being released by Oxford University Press, Louise Penny’s novel was also being released. Titled: How the Light Gets In! And she is a best-selling author. Two friends gently broke the news to me, but I had already known it and figured out how to deal. “Well, thank goodness she’s a best seller! Maybe someone will see mine next to hers!”

It took me a full year to wonder what Louise Penny is like as a writer. I went to the library, got her How the Light Gets In and did that wonderful disappearing act that happens in a really good novel. Reading it allowed me to live for a few days in a little Canadian town where all sorts of trouble happened to utterly believable people. I fell in love with her “Ruth,” suffered, laughed, learned, and had to go read more of her books. I liked it so much I wrote her a note telling her so. Only the third time in my life, I’m rather sorry to say, that I mailed (although I wrote many) a letter to a famous author to thank her or him for writing that mattered greatly to me: Janet Burroway, for one sentence in Raw Silk, and Philip Levine for his collected poems.

It took me a full year to wonder what Louise Penny is like as a writer. I went to the library, got her How the Light Gets In and did that wonderful disappearing act that happens in a really good novel. Reading it allowed me to live for a few days in a little Canadian town where all sorts of trouble happened to utterly believable people. I fell in love with her “Ruth,” suffered, laughed, learned, and had to go read more of her books. I liked it so much I wrote her a note telling her so. Only the third time in my life, I’m rather sorry to say, that I mailed (although I wrote many) a letter to a famous author to thank her or him for writing that mattered greatly to me: Janet Burroway, for one sentence in Raw Silk, and Philip Levine for his collected poems.

So, I am now reading Louise Penny’s A Trick of the Light. She has caused me to acknowledge to myself how much in my life I have feared criticism of my poetry. Not so much my prose writing – there I seem to be able to receive and use critical response without the disabling inner voice that says, “Oh, why, why, why, did I show that to anyone? I know I’m not good enough!” But my poems – they come from a place so private in me, so vulnerable – hearing critique of a certain kind is simply a sharp jab into an already open wound.

Penny uses language precisely, beautifully. In A Trick of the Light her characters examine the life of the artist from as many sides as there are major characters, great artists and – well, not so great. Perhaps the most truly incapable artist in this novel, not at all a major or sympathetic character, really, stills deserves the compassion of Penny’s allowing us to see his disappointment: “ . . . the world-weary artist seemed to sag, dragged down by the great weight of irrelevance.” I recognized myself in him then – recognized myself twice, actually. First, when I was young, hungry to achieve, having no ladder to climb, no experience of life to write in the voice of what I was taught was “the greatest poet: T.S. Eliot.”

I was in college when for the first time I sent a poem to a magazine – Motive, a Methodist magazine for college students. It was accepted and printed. Then I wrote to the editor, scolding him for publishing such a bad poem! He wrote back a short note, obviously confused, saying that he had thought it was quite good. What a strange thing for me to have done! The hope, the need, the desire, and the self-flagellation! The shame.

Secondly, I recognize myself now, working on a new book of poems, coming back to poetry after ten years of focus on writing prose in my How the Light Gets In. Even now the old demons of self-doubt lurk. But that young poet that I was, did dare to try, and something in her already knew that leaning on the opinion of critics was dangerous. Thinking about that now helps me to remember that the important daring is simply to grow as a poet — to give time to reading poets whose work excites me, to learn from them and try to write better poems than I have ever written – for the simple sake of the poem. For my own sake. On the days, the hours, the minutes, when I remember that, it is a lovely freedom.

I closed Penny’s beautiful book (my favorite of the ones I’ve read so far) with the clear thought that my poems are irrevocably in the idiom of the language I myself own out of my particular and parochial sensibility. They require privacy for their gestation, and they require critical response for their ultimate maturation. But I need to be careful about whom I ask for response. I need to practice myself what I have taught: to know when to make changes that strengthen the work, when to toss out suggestions that take it away from my own vision, and I need to accept it when I am told that the work is good.

Penny is not going to tell me a way out of the tangle she so brilliantly studies in A Trick of the Light. I don’t even want her to, because the only way out of it is to write my way out. To write my way even more fiercely into my own voice, my own idiom, the rhythms, the singing of my people – the ones mostly gone now, except as they sing in my memory, and in my poems.

I think of Penny’s character, Ruth, a fierce old woman sitting on a bench, “stoning” the birds” – with chunks of bread. I want to be more like Ruth.

Thank you, Louise Penny.

October 15, 2014

WISHING YOU COULD DO SOMETHING…

For me, Ebola has come home.

A sister in the spirit and in the work of AWA, Bisi Ideraabdullah, is at risk, at personal peril, in the fight agains Ebola. She founded a clinic in Liberia 21 years ago. It now serves apps. 17,000 women and children each year. Now two of its staff have fallen to Ebola. If you can, please join me in reading the material below, and giving what you can.

My friend and colleague Elise Rymer wrote the pieces below and has allowed me to share them with you:

____________________________

Ebola in Liberia – a way to help through a small, highly effective, NY-based non-profit

Click here to jump right to “How to Help”.

There is a pain—so utter—

It swallows substance up—

Then covers the Abyss with Trance—

So Memory can step

Around—across—upon it—

……………….. – Emily Dickinson

Several days ago I sent a copy of Dickinson’s poem to my friend Bisi Ideraabdullah. From the first time I met Bisi, I knew she was a remarkable woman and was the founder and executive director of Imani House in Liberia and in an impoverished area in Brooklyn.

Almost a decade ago, Bisi and I got acquainted during a weekend writing retreat focusing on race. Pat Schneider, life-changing writing teacher and founder of Amherst Writers & Artists, had invited four African-American women and three other Anglo-American women to join her. That arduous yet exhilarating weekend laid the foundation for the friendship that has been deepening between Bisi and me over our years of serving on the Amherst Writers & Artists Board.

This July, after watching the PBS Newshour and one more report on Ebola in West Africa, I was wracking my brain as I sat, like many of us, feeling utterly helpless in the face of “pain so utter” – a scourge, a terror, a disease killing people of all ages, a disease that makes touching, helping, nursing the sick easily lethal. How to help? how to help? The light bulb finally went on in my brain –- well, duh, call Bisi. She’ll be able to tell those of us who want to help what we can do.

This July, after watching the PBS Newshour and one more report on Ebola in West Africa, I was wracking my brain as I sat, like many of us, feeling utterly helpless in the face of “pain so utter” – a scourge, a terror, a disease killing people of all ages, a disease that makes touching, helping, nursing the sick easily lethal. How to help? how to help? The light bulb finally went on in my brain –- well, duh, call Bisi. She’ll be able to tell those of us who want to help what we can do.

Having emigrated from Brooklyn to Liberia in 1985 with her husband and family of four, Bisi early on established the first Imani House. “Never a stranger to helping others,” she saw that literacy and other outreach programs could ease some of the desperate conditions of those living nearby. “Raised by her grandmother as a small child, she witnessed philanthropy as early as she could remember. She had always been aware of the power to change people’s lives. “I was never taught that one person couldn’t change things. My grandmother was the kindest person. I grew up with her as a small child and watched her,’ she said. ‘We don’t realize how much our children are watching, but the way they learn to walk and talk is the same way they learn to care.’”*

Not long after the Ideraabdullahs had settled in Monrovia (Liberia’s capital), civil war was instigated by Charles Taylor. This war became one of Africa’s bloodiest. Bisi and her husband sent their children back to Brooklyn to be safe with family members.

Being firsthand witnesses to the chaos and suffering brought about by the war and feeling a need to help, Bisi and her husband began volunteering, caring for the wounded and sick at a hospital near their home. Neither had a background in health or had ever been through a civil war; certainly they were not prepared for what they witnessed: severe hunger, desolation, atrocities, suffering and death. Large numbers of children were brought to the hospital for treatment or because they had nowhere else to go. Many children were never claimed by family or relatives, so Bisi began a makeshift orphanage in her own home. All the while she managed to continue and expand the work of Imani House, and eventually a clinic was built in Jahtondo Town ten miles north of the capital city of Monrovia.

Being firsthand witnesses to the chaos and suffering brought about by the war and feeling a need to help, Bisi and her husband began volunteering, caring for the wounded and sick at a hospital near their home. Neither had a background in health or had ever been through a civil war; certainly they were not prepared for what they witnessed: severe hunger, desolation, atrocities, suffering and death. Large numbers of children were brought to the hospital for treatment or because they had nowhere else to go. Many children were never claimed by family or relatives, so Bisi began a makeshift orphanage in her own home. All the while she managed to continue and expand the work of Imani House, and eventually a clinic was built in Jahtondo Town ten miles north of the capital city of Monrovia.

Despite her and her husband’s move back to Brooklyn in 1996 due to the civil war, Bisi, with the help of her husband and long-time staff members, has continued relentlessly to pursue and expand the work of Imani House in Liberia as well as in Brooklyn.

When asked how she’s done and is continuing to do so many remarkable things for others over decades, her answer not infrequently has been, “It helps to have post traumatic stress disorder because you do not stop working. You do not want to sleep, because you dream about the things you saw… You just want to work.”*

When I e-mailed her, she responded immediately. She let me know how I could help, yet not once did she ask for a contribution. I finally brought it up, and yes, she said, funding was becoming yet another crisis. Contributions of any size would help, especially with morale. Those on the front lines need to know others care. Here, I thought, was an open avenue to a highly efficient, established organization where I could fully trust the leadership, where even small contributions would go a long way, including keeping hope vitalized in the face of a terrifying disease.

If you’re interested in learning more, the place to start is with the Imani House website. It has updates on the clinic and its work with Ebola patients and also staff efforts to educate people about the disease, including protective measures against being infected.

If you would like to contribute online, information is on the Imani House website. Or you can write a check made out to Imani House and send it to the following address:

Imani House, Inc.

c/o Mrs. Bisi Ideraabdullah

76-A Fifth Avenue

Brooklyn, NY 11217

(Phone: 718 638 2059 Fax: 718 789 1094)

Imani House is a 501(c)3.

__________________________________________________

From Global Giving–

Imani House International (IHI) Clinic is 21 years old. It has lost two of its staff but remains open in the face of the contagious Ebola Virus scurge. Located on the outskirts of Monrovia Liberia, each year the Clinic serves appx. 17,000 women and children.IHI is asking others to join them in this fight against this unseen enemy Ebola that is destroying the lives and fragile infrastructures of W. Africa. Contributions are sought to help the organization keep the clinic open, and to purchase much needed protective supplies for the staff and community, acquire an ambulance, complete the renovation of a small building that will serve as a triage and isolation space for suspected cases of Ebola, to expand the community education and Ebola awareness campaign, and to allow IHI to serve as a public information bridge for other health workers & the Ministry of Health. Donate at http://www.globalgiving.org/projects/ebola-outbreak-help-us-protect-liberians/

$60 – will buy a case of 300 safety masks,

$25 will buy one Hazmat suit for a staff person

$10 will purchase 6 gallons of clorox for clinic daily disinfectingContact Bisi Ideraabdullah at 347 210 8026 www.imanihouse.org

October 6, 2014

HUFFINGTON POST – 04/29/2013

(If you want to read my article directly on Huffington Post, feel free to click the icon to the left – it will take you directly there.)

Writing as a Spiritual Practice

Originally Posted on Huffington Post: 04/29/2013 5:33 pm EDT

I am writing now as a spiritual practice — and I don’t mean writing liturgy or prayers or preaching anything to anyone. I mean using the first and most primary human art form — language — to explore my own deepest questions and express my own most important experiences and imaginings.

A long time ago, I had a hair-dresser named Fred who was a rehabilitated truck-driver. Stepping into his truck one winter day, he slipped on ice and damaged his back so badly he could no longer drive his truck. He went for vocational testing, and when he learned that the top recommendation was hair dressing, he was, to put it mildly, horrified. But it was explained to him: You are very intelligent; you are very independent; you need to be your own boss. Hairdresser. After some agonizing he decided if he had to be a hair dresser, he would be the best hairdresser. He enrolled in a top level school in New York City, and came out of it a talented man with comb and scissors.

What I loved about Fred was, as a high-end hair man, he never lost the twang of the trucker. My brother was a trucker, I knew the breed well. Fred and I became good friends, and when he learned more about me, he offered to do my hair free in return for talking to him about some concerns he had. One of my concerns was the cost of haircuts, so this was a desirable arrangement. He was a practicing Catholic, but had lost the privilege of receiving the Eucharist because he had had a vasectomy. He was vastly afraid of hell. Some time after we worked through that dilemma, he suffered a heart attack, survived and needed to discuss an even more desperate question.

“I’m going to hell, Pat. This time I know I’m going to hell.” As he cut my hair he described the pain of the attack: “It was the worst pain I’ve ever experienced. I lay there on the table, and I said to God, ‘Kill me or let me live, but take away this fuckin’ pain.'” His face in the mirror, meeting my eyes, was blanched with fear. “You can’t talk to God like that,” he said. “I’m gonna go to hell.”

Sometimes when things are so real they hurt, words come that T.S. Eliot called “what we know and do not know we know.” I said, “Fred, I bet God is delighted! For the first time in your life, you talked to God in your native tongue, your own natural voice — like you talk to your best friend. Catholics believe that God is father, right?” He nodded. “Supposing it was your child who cried out like that in pain, what would you do?”

He got it, and I myself “got it,” too — that what we need in our spirituality is intimacy with the mystery that we may call “God” or “Allah” or a presence that is beyond our ability to name. But intimacy with mystery requires that we ourselves be present. We must be most ourselves, not hidden behind religious ritual or rules of grammar. We need our own voices to cry out our deepest cries, to express our wildest joy, to plumb our hardest questions. And we need to begin with our ordinary, complicated, but beautifully nuanced and perfectly adequate, ordinary everyday lives. Let me finish here by quoting from my book with Oxford University Press, “How The Light Gets In: Writing as a Spiritual Practice”:

Writing can be a spiritual practice. To write about what is painful is to begin the work of healing. To write the red of a tomato before it is mixed into beans for chili is a form of praise. To write an image of a child caught in war is confession or petition or requiem. To write grief onto a page of lined paper until tears blur the ink is often the surest access to giving or receiving forgiveness. To write a comic scene is grace and beatitude. To write irony is to seek justice. To write admission of failure is humility. To be in an attitude of praise or thanksgiving, to rage against God, or to open one’s inner self and listen, is prayer. To write tragedy and allow comedy to arise between the lines is miracle and revelation.

September 29, 2014

HUFFINGTON POST – 05/08/2013

(If you want to read my article directly on Huffington Post, feel free to click the icon to the left – it will take you directly there.)

Original Voice, Original Genius

Originally Posted on Huffington Post: 05/08/2013 12:19 pm EDT

We know now that a baby comes out of the womb with a rather sophisticated understanding of language — enough to recognize the particular music of the mother’s speech, distinguishing it from the voice of the other parent, and his or her voice from the voice of the stranger. Language is our original art form, formed as we ourselves are being formed, rooted in the genius that is in every human being. The ancient Hebrew poets said it best: We are created in the image of the creator. If that is true, we, too, are creators, and language, voice, is our first, our primary artistic creation.

Sadly, here and in many places on earth, this still is not understood. Once I was invited to be writer-in-residence in a prestigious school in France.

The ninth-grader in whose home I lived proudly showed me his perfect Shakespearean sonnet written in Shakespearean English. But when I tried to get him to write in his own voice, he was terrified. He wouldn’t even try. An entire roomful of teenagers — in fact, room after room — would not try. Finally, one girl was brave enough to risk reading aloud what she had just written. Halfway through she broke into tears.

One of my last assignments was to have a one-day writing workshop with the school’s six English teachers. I reminded them of my experience with their students, how they were skilled at mimicking famous writers, but unable to do original work in their own voices. I challenged the teachers to try using the voice they used around the kitchen table or with best friends. I put out a group of objects as a prompt: a stained wooden spoon, a well-used baseball, an old, empty whiskey bottle — perhaps 50 familiar objects. There were three men and three women. It was easier for the women, but they read tentatively, anxiously. One man refused to read; the other two broke into tears as they read. One said in a choked voice, “This is the first time anyone ever asked me to write in my own voice.”

As teachers, it has been said, we teach best what we ourselves are still learning. I have had a hard time claiming my own voice. As a kid in a two-room apartment in a St. Louis tenement with a single mother who said frequently, we’re gonna get out of here and education is the way to get out, I understood that the power to get out was somewhere in school. My teacher said T.S. Eliot was born in St. Louis, and that he was, in 1948, when I was a ninth-grader, America’s greatest poet. I wanted to be T.S. Eliot. I desperately wanted to get out, and didn’t Eliot get out? Poetry was the way. Somewhat like the French students, it would never have occurred to me to write openly about my own life. Eliot was educated at Harvard; he wrote his own lived images: In the room the women come and go/ Talking of Michelangelo. No way could I write about standing in line in a dark hallway behind an old man with his pee in a milk bottle waiting for the bathroom where no one cleaned. Or about the roaches under the sink, the dirty milk bottles piled in the pantry, or the rats that came up the broken furnace duct. I was taught subtly — and so very well — that the only good writers were those with privilege. I couldn’t stop trying to write like someone else until I was in my ’40s. And not until I was 70 could I claim my own voice as my spiritual practice.

When will we stop considering as art only the voices of the privileged? The flaw we hear in “bad writing” is not absence of knowing Shakespeare. The flaw is hiding our first, deepest voices, suppressing them and coming to believe they don’t exist. It may not sound at all like Shakespeare, but it is the only platform solid enough to support learning craft — using other voices, which may include writing a Shakespearean sonnet. The voice that has listened in the womb and practiced every day all day and even while dreaming at night is absolutely original, powerful and, therefore, the stuff of genius.

September 21, 2014

HUFFINGTON POST – 05/28/2013

(If you want to read my article directly on Huffington Post, feel free to click the icon to the left – it will take you directly there.)

Writing Your Way Home

Originally Posted on Huffington Post: 05/28/2013 6:18 am

What would it mean to claim ourselves as writer/artist, fully in possession of one brilliant, nuanced voice, and then to learn additional craft, additional voices, without suppressing the innate genius that John Edgar Wideman calls “the language of home” and Paule Marshall calls “the poets in the kitchen”?

For me, it has meant finally coming to terms with my place of origin, geographically, economically and emotionally. It means being braver and far more honest. At age 70, it meant asking myself: What do I want to do before I leave the planet?

and discovering that I wanted to bring everything — the poverty, the orphanage, the years of school, marriage, mothering, teaching and aging; all the tangled and wondrous threads that make up the crazy quilt of my life — to asking the question, What does it all mean? When I told my former agent about the book I wanted to write, she said, “I can sell that book with an outline and one chapter.” And I said, “No, I need as much time as it takes to ask all of my hardest questions.” I had no idea it would take seven years. In saying “no” I realized that this time I was not at all writing for publication, although I hoped someday it might be published. I was not writing for any other reader, although I handed chapters out in my workshops and to friends to get critical responses. I wrote questions, and then wrestled with story, memory, and learned craft, writing always in my own voice.

My place of origin is Missouri (Missourah, the rural part). It is an odd place of origin for a writer. The hilly Ozark land is claimed by neither east nor west, north or south. My friends from Alabama go into shock if I say I grew up in the south. It’s true we didn’t eat grits; apparently Missouri’s cornbread, fried chicken, biscuits and gravy just don’t cut it. I live now in Massachusetts, where the language is different. “Stones” in New England are “rocks” where I came from. “Fireflies” are “lightning bugs”; “Streams” or “cricks” are “creeks.”

And “mother” is “mama.”

In my 40s, that got me into trouble. I had finished my MFA in creative writing, was published in literary journals and had had a libretto performed in Carnegie Hall. A friend suggested we trade poems and critique them. She had a book of poems published; I didn’t. When she returned my poems, they bled red ink on every page. I agonized, Oh, no! I’m not a good poet! Who do I think I am, giving her my poems to read? But a comment on one poem bugged me. It had already been published. It was titled “Mama” and began:

Kerosene, gasoline, Maybelline, Vaseline–

Mama said she knew a family

in the Ozark mountains

named their baby Vaseline Malaria

because the words were pretty.

Her comment was: “Mama is a childish name for mother.” I tried revision: “my mother” and “who named” and maybe “interesting” instead of “pretty.” Stuff like that. But the new words threw off the Ozark rhythm and — finally! — “Mother” was dishonest. It hid something intimate. It was not right. I looked at my other poems. It was the same everywhere: She was taking Missouri out of my poems!

If I had not studied poetry, if I had not learned craft beyond my own voice “of home,” I would never have figured that out. I would have assumed my poems were not good. I would be ashamed and would suppress the greatest gift I have: the original twang and click and clack of my language of home.

Craft is important for the writer, but craft that can be taught must be the servant of craft that is original and innate — not the other way around. Writing as a spiritual practice can be the most freeing of any I have found in a long life of trying different paths. It deserves all we know and all we can learn. Most of all it deserves the brilliant and original voice that began to be formed in the waters of the womb. In the beginning was the word.