Tim Stafford's Blog, page 7

August 10, 2021

Catastrophe, Part 2: Moral Blindness

In my previous post–”Living On the Edge of Catastrophe”—we observed the Joneses of Georgia and their inability to see that their entire way of life was about to be destroyed in the Civil War. Despite dire political circumstances, they couldn’t believe that the worst would come. They shrugged it off and talked themselves into believing that catastrophe couldn’t happen. Like them, I tend to be optimistic and patriotic, thinking that somehow common sense will prevail in America. It ain’t necessarily so!

Now I’d like the consider the moral blindness afflicting the Joneses.

Slaveholders as depicted in the movies are obviously evil. They delight in tormenting black people. If they claim to be Christians, they are transparently hypocritical. Cruelty is their true religion.

The Joneses don’t fit that picture. In almost every way, they show themselves to be kind to their neighbors and principled in their business dealings. They are people of sincere faith, and it pervades their view of life. They rarely come off as sanctimonious. Perhaps the one theme that suggests sanctimony is the constant urging of both parents toward their son Charles to make a public confession of faith and be baptized. They bring it up again and again, and most particularly when his first wife and young daughter die in quick succession of an infection in childbirth and of scarlet fever. His parents are deeply grieved, sympathizing with their son in every way that parents can, but they cannot help themselves from urging that he, too, could die and fail to be reunited with his loved ones in heaven. Again, when Charles becomes a lieutenant in the confederacy, his parents are full of fear that he could die unbaptized in battle. They urge him to make a profession of faith and gain the ease, the comfort of assurance. Their concern seems completely authentic, genuinely and deeply concerned for his eternal welfare, but it’s insistent in a way that would be way over the top in any family I know. Except, Charles doesn’t seem to resent it. He knows they are expressing their care for him, and he believes as they do—it’s just that he can’t bring himself to the point of public profession.

Are they genuine in their faith? I think so.

Regarding their slaves, it’s hard to read exactly how kind the Joneses are, because they rarely detail their interactions. They seem to like their house servants, often referring to them by name and nearly always closing their letters with “howdy to the servants!” I am sure the Joneses would have claimed vociferously to have positive relationships with their slaves, and they certainly saw themselves as their protectors and benefactors. However, the relationships seem superficial, and—at emancipation—would prove to be.

Slavery, the Joneses believed, was a benefit to both black and white. They perceived their servants as simple, occasionally charming, but always in need of the superior discipline and order white people could provide. The servants let them think so. How much corporal punishment was required to keep “order,” and how close acrimony came to the surface between slave and master, is hard to tell from the letters. Such issues rarely appear. Since the Joneses seem to share freely about all kinds of issues in their daily lives, I have to conclude that the system worked smoothly. It was easy for the Joneses to conclude that “smoothly” equaled “well.”

Only one case mars this picture of harmony. An 18-year-old slave woman escapes—her name is Jane–and is discovered working under another name as a free black in Savannah. Caught, she is imprisoned, and Reverend Jones decides to sell her entire family. Evidently this family has been difficult for some time, and he is weary with the continual hassle of trying to bring them in line. Rev. Jones tries to live by his precepts. He makes up his mind to sell the family as a unit, even though he could get more for selling the pieces separately. Determining to find a new owner who he thinks will treat them responsibly, he consoles himself with the thought that a new start is best for everybody.

The cold-blooded reality, however, comes when Reverend Jones lists the family members for sale, including their estimated prices: A father and mother, in their forties; five children between the ages of 20 and 12, and a 29-year-old man who is for some reason attached to the family. Their prices range from a high of $1,000 to a low of $600. They are inventoried like pieces of farm equipment. It’s business. Reverend Jones wants a good master for them, but he also wants the highest price he can get.

I can’t tell whether the question ever occurs to him or his offspring: who gave you the right to own these people? The whole Jones family evidently believes, as indeed almost the whole South believed, that because the system ran smoothly (most of the time) it had to be right and just. No one asked the slaves, of course—but since they were simple people, unable to really care for themselves, their opinion did not matter.

It is a monstrous conception, utterly at odds with the image of God in humankind. Slavery’s pervasiveness throughout history and in biblical times says nothing to temper that judgment. Murder and theft were pervasive too.

Abolitionists from the North (and the South too, before they were driven out) could have taught them a different view. But the Jones family knew that abolitionists were fanatical infidels, godless and devoid of Christian morality. “And what will appear most remarkable to the sober, pious mind,” writes son Charles from Boston, where (while a student) he has attended the trial of Anthony Burns, a captured runaway slave being returned to the South, “is that [anti-slavery opinions] all come as emanations from the respective pulpits of this vicinity—promulgated, moreover, upon a day which the Lord has consecrated for His especial service. Strange and enormous must be the stupefying fanaticism of that man who, professing to be called of God for the revelation of holy things unto men, can so far forget his sacred office, and the solemnities of the season, as to indulge openly in vituperations against his country and fellow man, not only unbecoming a minister but unworthy a sensible person upon a secular occasion. It is really surprising to what an extent a person becomes an actual fool who, possessed of one prejudice, one misconceived idea, surrenders himself a total slave to its miserable influence.” (44)

That might be the wound-up, over-the-top rhetoric of a young man who has attended a life-and-death trial and heard vehement speeches. But in the 1,400 pages of Jones letters, there are really no other opinions. Abolitionists who speak for the slave are fools, infidels and knaves. They seek to destroy the South. Not once is there a hint of humility, of the thought that, “I might be wrong.” Not even, “I realize there are other ways of seeing this.” Nor, “It would be a terrible thing to be born a slave.”

It’s not that they aren’t good people. They are. But they are stupefyingly blind. They have grown up with slavery, prospered from slavery, and dealt with it (successfully) every day of their lives. It has taken away their ability to see.

I am not sure I would have been any different, if I grew up in the same place. And what, I wonder, could be my moral blindness today?

One thing I know: the words “walk humbly” should never be left out of our moral mandates. We must consider every day the possibility that we could be wrong. That in itself will not keep us from moral blindness, but at least it will open us to the possibility of learning something new.

August 9, 2021

Living on the Edge of Catastrophe—Part 1

America is polarized as never in my lifetime. The split between red and blue expresses ancient worldviews, but differences are amplified by social media and news media, and pushed to extremes by a sense on the part of both sides that we are living on the edge of catastrophe.

On the left, dread of catastrophe increased dramatically on January 6, 2021, when rioters stormed the Capitol in an attempt to stop Congress from certifying the election of President Joe Biden. It had never occurred to us that our entire system of government was at risk—that democracy in America could be overthrown and we could wake up living in a North American Hungary or Nicaragua. You think liberals are shrill? That’s why.

On the right, fear of a different kind of catastrophe holds sway. Throughout my lifetime conservatives have been telling of the fall of the Roman Empire as a warning against decadence. Now, the pace of social change has led to social panic that gay marriage, gender fluidity, immigration, drugs, crime and the decline of Christianity are making America a place of unrecognizable moral chaos. To many on the right, we are in the last days, with a final, slender opportunity to rescue the country we love.

A third form of catastrophe, climate change, increases anxiety on all sides. The stakes are vast, the territory unknown, and we begin to feel the effects in our daily lives. It’s unsettling, and our fears leak out and spread.

I never have been a catastrophist, and I don’t believe most Americans are. We have been a nation of optimists and patriots, trusting that no matter what the challenge things will work out for the best because America has deep strengths that preserve it from disaster. When Popie and I lived in Kenya, we observed the fragility of the political order there and in most of Africa. A president feared traveling abroad because a coup might happen while he was out of the country. Elections could be and were stolen. We looked on this with sadness, but it never occurred to us that such things could happen in America.

I still don’t believe, in my gut, that they could. I just can’t believe that we could throw away our democracy or lapse into moral chaos. I’m an optimist. I’m a patriot. I expect that common sense will rule the day.

A book I just finished, however, The Children of Pride, has given me pause. It’s a massive collection of letters from within a Georgia slaveholding family from 1855 to 1868—the years just before, during and after the Civil War. The father of the family, Charles Colcock Jones, is a Presbyterian pastor who has dedicated his life to preaching the gospel to slaves. He and his wife Mary are well educated, thoughtful, temperate and loving. Their two sons, Charles and Joseph, attended Princeton University. Charles went on to study law at Yale, practiced law in Savannah and was elected mayor of the city in 1860. Joseph studied medicine in Philadelphia and became a well-regarded doctor and medical researcher. Mary, the daughter, married a Presbyterian pastor.

It would be hard to read these letters and not like the Jones family. They obviously love each other, and they care about the people in their community (including their house servants, whom they frequently mention). They write well and intelligently. It’s true that their wealth—they own three plantations in coastal Georgia—and their ownership of well over 100 slaves are hard to swallow. But reading their letters, you tend to forget that. Their lives are interesting. Babies are born, people fall in love and marry, people die—little children particularly—and fear of disease is a constant. A hurricane, vividly described, ravages their land. Planting and harvest are followed with intense interest. The Joneses write often of the beauty of the landscape.

They are not a particularly political family, and in the years 1855-1860 their letters rarely mention the national crisis over slavery. They know what is going on, and there is no doubt that they are staunch Southerners, deeply distressed by abolitionist ideas, but you look in vain for any signs of real fear or agitation. I found it fascinating and unnerving, because I noted the dates on the letters and—knowing what was coming–could feel the storm clouds gathering. The Joneses apparently did not. They were living their enviable, enjoyable, mostly-peaceable life, unconcerned that their entire way of life was about to be obliterated. Even in 1860, when firebrand Southerners were spoiling for a fight, and secession was on the table, they couldn’t believe that it would come to much. Like me today, they thought surely common sense would prevail.

Here’s Reverend Jones, writing his son Charles in January, 1860: “Our political sky is very cloudy! Have you read the Vice-President’s speech lately delivered at Frankfort, Kentucky? My hope is the He who has so often and so mercifully preserved our country will again show us favor, unworthy as we are, and deliver us from impending evils and grant us peace. He is able to still the tumult of the people.” (p. 556) Then he goes on to send greetings to Charles’ wife Ruth and a kiss to their baby.

And here is Charles, writing back in October, just before Lincoln’s election: “Should Lincoln be elected, the action of a single state, such as South Carolina or Alabama, may precipitate us into all the terrors of intestine war. I sincerely trust that a kind Providence, that has so long and so specially watched over the increasing glories of our common country, may so influence the kinds of fanatical men and dispose of coming events as to avert so direful a calamity.” (p. 621) He goes on to mention that his wife and child are coming home on Monday. Otherwise, not much is worth noting. “We have but little of interest with us.”

His father writes back a few days later: “I do not apprehend any very serious disturbance in the event of Lincoln’s election and a withdrawal of one or more Southern states, which will eventuate in the withdrawal of all. On what ground can the free states found a military crusade upon the South? Who are the violators of the Constitution? Will the conservatives in the free states make no opposition? If the attempt is made to subjugate the South, what prospect will there be of success? And what benefit will accrue to all the substantial interests of the free states? The business world will think very little benefit. Under all the circumstances attending a withdrawal there would be no casus belli. Is not the right of self-government on the part of the people the cornerstone of the republic? Have not fifteen states a right to govern themselves and withdraw from a compact or constitution disregarded by the other states to their injury and (it may be) their ruin? But may God avert such a separation, for the consequences may in future be disastrous to both sections. Union if possible—but with it we must have life, liberty, and equality!” (p. 625)

Today’s reader cannot help noting that the pastor’s “life, liberty and equality” involve denying liberty and equality to more than one hundred men, women and children whom he purports to own. He is not stupid, and he is not ignorant, but he cannot see what is in front of him.

So the war came, and if the Jones family did not welcome it, they seemed to greet it with a kind of shrug. By mid-November the pastor’s wife, Mary, writes to son Charles: “It is a new era in our country’s history, and I trust the wise and patriotic leaders of the people will soon devise some united course of action throughout the Southern states. I cannot see a shadow of reason for civil war in the event of a Southern confederacy; but even that, if it must come, would be preferable to submission to Black Republicanism, involving as it would all that is horrible, degrading, and ruinous. ‘Forbearance has ceased to be a virtue;’ and I believe we could meet with no evils out of the Union that would compare to those we will finally suffer if we continue in it for we can no longer doubt that the settled policy of the North is to crush the South.” (p. 628)

The war would utterly destroy her way of life. The Joneses lost none of their immediate family members to the fighting (both sons were enlisted as Confederate soldiers) but Sherman’s army swept through their farms and took nearly all their moveable property. The Southern plantation, dependent on slave labor, became impossible, and the Joneses could not find buyers for their thousands of acres of land at any price. The three children would eventually thrive (Charles, ironically, in New York City), because they could call on professional skills; but plantation life was dead. Not until the coming of Jim Crow would a mutant, crippled version of it resurrect.

What stays with me in this part of the story is the blithe unawareness. The Jones family, for all their sense and education, could not see that they lived on the edge of catastrophe. Could they have done anything to prevent it? Perhaps not if they acted alone, but if a large slice of Southern gentility had spoken strongly against Southern radicalism, the outcome might have been different.

The same may be true for us, in our time. We live on the edge of catastrophe, and yet I find it very hard to believe in the threat. Maybe these settled instincts are right. Maybe common sense will prevail. The Joneses remind me, however, that that is hardly guaranteed. It really could all go smash.

The Wisdom of Words

I preached at my church on Sunday, part of a series on Proverbs. The sermon has two parts: one on the importance of life-giving speech in personal life, and one on the dangers of certain kinds of speech in community life, particularly lying and mockery. Here’s the podcast. It’s about 20 minutes long.

April 16, 2021

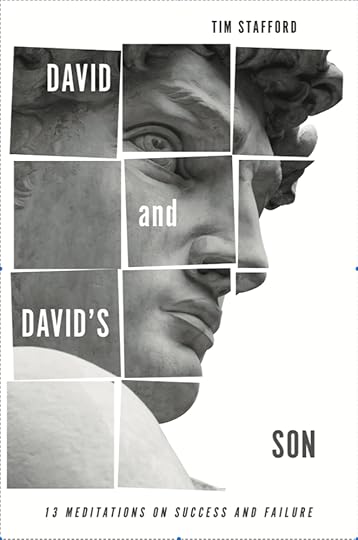

David and David’s Son

The book I’ve been working on for three years, David and David’s Son: 13 Meditations on Success and Failure, is published and available on Amazon. Here’s the link: https://www.amazon.com/David-Davids-Son-Meditations-Success/dp/B092C6B5NT/ref=tmm_pap_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=1618610108&sr=8-1

I’m very excited about this book. It covers virtually every episode in David’s long and fascinating life–including some that never make it into sermons–and explores his personality and character in detail. I frame the book around 13 meditations, tying David’s highs and lows to our experiences of ambition, frustration, success and failure. Anybody with hopes and dreams will find multiple points of connection. Each chapter ends with a Question for Meditation, to help readers use the book for personal devotion or for a group study.

I learned a lot in working on this book, and I am hopeful others will too.

Here’s the back cover copy:

Here’s the back cover copy:

David’s career path was a roller coaster: from teenage nobody to ace commander, from fugitive to king, from high-on-God to lost-in-sin. He lived ecstatic triumphs and devastating failures. In David and David’s Son Tim Stafford carefully analyzes the highs and lows. He asks, “What can we learn about success and failure from David’s drama?”

David is a compelling personality, strong and charismatic and yet enigmatic, too. How was he lifted so high? Why did he fall so low? Through David and David’s Son you’ll accompany him through every challenge, and get to know him deeply.

“David’s Son” is Jesus. There’s a reason he was so often referred to as “Son of David,” and it’s more than genealogy. David’s story is captivating, but it only really has meaning when embedded in God’s story that culminates in Jesus. David and David’s Son explores many parallels between Jesus’ and David’s lives, and shows how Jesus completes David’s story. We learn to see David in Jesus’ redemptive light.

The real David is not a Sunday school hero, but a deeply flawed, deeply troubled, deeply blessed human being—a king, a warrior, a poet, a husband and a father. Come walk with him.

February 10, 2021

The Color of Law

The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America, by Richard Rothstein

Black families in the US have, on average, about a tenth of the average White family’s accumulated wealth. Black men are far more likely than Whites to be stopped by the police, arrested by the police, or shot by the police. Black children lag behind White children in education almost everywhere.

Racism, by my non-academic definition, is personal prejudice against people of color. It’s real, but today not nearly as pervasive as a faceless racism built into the way society functions. Those three discrepancies I cited in the first paragraph? One—policing disparities—may be largely due to personal prejudice. But wealth and schooling? There’s rarely a scowling face of prejudice behind those disparities. Rather, there are multiple societal forces at play, which make it so “it just works out that way.” You can’t find anybody to blame.

More accurately, you can find too many people to blame. Lots of different nicks and scratches add up, but it’s hard to say just when and by whom the car was trashed.

Richard Rothstein, a lawyer, makes the case that segregated housing is responsible for a lot of those nicks and scratches, not to mention the head-on collisions. Since Americans accumulate and pass on wealth mainly through the house they own, the difference between White suburban housing and Black inner-city housing is a major contributor to wealth disparities. That affects how people respond to emergency expenditures, and whether they can afford college for their children.

But there’s more. Because Americans usually send their children to a neighborhood school, housing segregation leads to segregated schools, where “separate is not equal,” as the Supreme Court told us in 1954. Because Black housing tends to concentrate poverty, there’s more crime in Black neighborhoods, which circles back to downgrade the cash value of the housing and degrade the schools, which in turn leads to more crime. Segregated housing isn’t responsible for all our racial woes, but it contributes a lot.

People tend to segregate themselves, it’s true. The main reason Sunday morning is the most segregated hour in America is that most people prefer to worship with people like themselves. Some White churches would deliberately make Black people unwelcome, I’m sure, but I’m also sure there are more White churches that would go over the top in trying to make Blacks welcome, in the process making them more uncomfortable.

In bars, nightclubs, concerts, barbershops and beauty parlors, there’s a fair amount of self-segregation. New immigrants tend to settle near others who come from their home country, for very practical reasons (language and networking) as well as for comfort.

Housing is different, though. You choose where to live mainly on economic grounds: you want to live in a nice house. Having neighbors who look like you—or not having neighbors who don’t look like you—may be a preference, but for a lot of people it’s not an absolute. They’ll buy the nicest house they can afford, regardless of the neighbors. Segregation would tend to break down over time unless the government was working hard behind the scenes to make it stick.

That’s Rothstein’s case: that segregation isn’t just an unfortunate accident of personal preferences. No, the US government worked hard to segregate America, and keep it segregated. Rothstein asserts, therefore, that the US government is obliged to de-segregate America, undoing the damage done in the same way that it’s obliged to do away with nuclear waste in Hanover, Washington.

I liked Rothstein’s book because it’s very factual, proving its case with reams of historical information. I thought I knew a lot of the history of racism in America, but I knew nothing of this. For me, it really came home when he discussed segregation not in war-time Mobile, Alabama, or 1960s Chicago, but in parts of liberal Bay Area that I know well: Richmond, Milpitas, and Palo Alto. I had noticed, of course, that Black people tended to live apart from White people in those places. I had no idea what a concentrated, sustained barrage of work had gone on at all levels of government, federal down to local, to make it that way.

There’s no way a book review can comprehensively review Rothstein’s case, because it’s so information rich you almost have to read the book. In general, though, here’s how it worked:

After WWII there was a terrible shortage of housing, due to five years of the war and ten years of the Depression when almost none was built. Besides that, an exploding economy coming out of the war meant that people had money to buy, including Black people who had qualified for good jobs during the war and made the most of it.

A lot of houses needed building, and the government subsidized them in lots of ways. Public housing was built, lots of it—always segregated. Sometimes it was built by tearing down poor neighborhoods that were mixed, thus turning desegregated housing into segregated housing.

Very importantly, the FHA and the VA guaranteed loans in subdivisions that were available only to Whites. The famous Levittstown was built by a private contractor, but only because the FHA gave a blanket guarantee of housing loans for white people only. That was duplicated all over America.

Cities and counties used exclusionary zoning in suburban neighborhoods, excluding Blacks either by law or (more commonly) by income. By excluding apartments or homes built on small lots, they insured that only middle-income people could afford to buy. And guess what color middle-income people came in?

Furthermore, they allowed restrictive covenants to be written into deeds, and enforced them as though they were law. You couldn’t sell your house to a Black person.

The government further subsidized the (White) suburbs through roads and sewers and water projects, while inner-city (Black) development was deprived of rail and bus transport that would have taken residents to jobs that were moving out of the inner city.

Real estate agents were permitted discriminatory practices, even though they were licensed by the state. Banks were permitted redlining practices, though they were practically wards of the state.

Discriminatory policies of real estate agents meant that Black people were kept from viewing White houses, though the real estate agents were licensed by the state.

Police connived with white mobs using dynamite and arson and armed threats to force Black buyers out of White neighborhoods.

Schools were deliberately situated in locations that reinforced or further encouraged segregation.

Highways were routed through Black neighborhoods, demolishing them and forcing more Black residents into already crowded Black neighborhoods, which were the only places Blacks were allowed to settle.

Section 8 and other low-income-housing policies steered poor people to poor (Black) neighborhoods.

The Fair Housing Act outlawed discrimination in housing in 1968, but most of these practices continued long after.

I found it heartbreaking to read of the lasting, determined government policies that worked in the Bay Area to deprive Black people of decent (integrated) housing. Somehow it seems worse to learn of it in an area that you know, and where you never dreamed of it. Palo Alto?

Neara the end of WWII author Wallace Stegner and other Stanford professors started a co-op to build 400 houses on a 260-acre plot of land adjacent to the Stanford campus. Local teachers, city employees, carpenters and nurses joined in; three of the initial 150 families were African American. But banks would not finance construction nor issue mortgages without government approval, and the FHA would not insure loans to a co-op that included African-American members. The co-op board tried to find a compromise, promising that the proportion of Black homeowners would stay within the proportion of Black Americans in California. The government said no. Eventually the co-op gave up and in 1950 sold the land to a private developer, who built Whites-only homes with FHA-approved lands.

That’s just one small case out of hundreds that Rothstein details.

January 7, 2021

So Character Matters, After All

One of the implicit bargains involved in electing and supporting Donald Trump as president was that character doesn’t matter. He was a mean, lying SOB, but he was our SOB. Like a loudmouth drunk in a bar, or a crazy uncle at Thanksgiving dinner, he could be funny and he livened things up. He said what he really thought. He called out the people we don’t like. And he supported causes we care about: conservative judges, lower taxes, fewer regulations. He put a halt to immigration. So what if he had no more morals than a sow bug?

So now we know “so what.” Somebody who lacks morals will inspire other people who lack morals. Put them in power and sooner or later they will use that power for immoral ends. Thwart them, and they will work themselves into a fever pitch and assault their own country. They will try to bring down the democracy that has protected their right to be outspoken idiots. They will try to overturn an election whose results they reject, and they will eventually become a mob that invades and destroys in the halls of Congress. Nothing will stop them except force, and you know why? Because they lack morals. They don’t believe in character. They believe only in wielding power for their cause.

January 4, 2021

Kristin Lavransdattar

One of my most compelling reads of the past few years is My Brilliant Friend and its three sequels. I think of Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan stories as dark Tolstoy. They have the same deceptively simple surface and the same compelling narrative drive as Tolstoy, with characters that worm their way into your brain and won’t go away. But they are dark. In Tolstoy, light is not hard to find. Even the darkest of Tolstoy’s characters—even Vronsky—might be redeemed. His characters teeter on the knife’s edge between hope and destruction. In Ferrante’s novels, not so much. If you think that loyalty to family, marriage, friendship or other ideals matter greatly, you will be disabused. Her characters are driven by meanness.

Kristin Lavransdattar, by Sigrid Undset, is also long—about 1,100 pages in three volumes, often published as one—and has that same narrative force. Undset’s writing is very good, especially at landscape and weather, but it’s not showy prose. She is writing a story. Like My Brilliant Friend, it is the story of a beautiful, passionate, angry, doubting, willful woman. As in Tolstoy, Kristin is fundamentally in conflict between light and darkness. The light is in her loves and aspirations, especially her unaccountable passion for her charming, errant husband, and her deep-seeing love for the seven sons she births and raises. Darkness, never far away, is in her short-sighted folly, her ability to hold grudges, her perfectionism and, sometimes, her intolerance toward those she loves best, including herself. She is a compelling character whose complications deepen throughout her life. The other characters, principally her family members, are also complex, revealing different sides of themselves in different settings, and in the process becoming entirely believable.

Kristin is set in 14th century Norway. It is a medieval environment preoccupied with land, lineage and marriage, with omnipresent church and a good dose of surviving paganism. There are knights and sheriffs and kings and wandering pilgrims. Undset writes about this world as though she lived in it, and has no idea that her readers don’t. We forget that we are in history. To put it another way, we inhabit the history.

The novel was first translated into English in the 1920s–the same decade in which Undset won the Nobel Prize for Literature. I happened to read the first book in this old translation, and the rest in the new one, made in 2005. I much prefer the new. The old translation deliberately uses archaic, faux-medieval language, which (I read) does not reflect Undset’s simple, clear style. This archaic language may be a reason why the novel has been largely forgotten.

Another possible reason: as much as any novel I have ever read, Kristin is about faith. Kristin is a believer who, raised in Christendom, has never considered that any other option exists. Her father was a faithful believer who taught her prayers from the time she was a very young girl, and as she idealizes him she idealizes her faith. Her trouble is that her belief is difficult to square with herself, with her passionate character that often leads her astray. Her struggle is less with God—though her prayers are questing and questioning—than with herself. She does not know how to go on in life as a guilty person. She wishes deeply to be gracious but is often stuck with harsh attitudes toward those she loves best. This conflict is the root of Kristin.

The story is not primarily psychological or spiritual, however. It involves intensely practical details of life, from farming to infidelity, from sedition to murder, from the plague to the rigors of childbirth. Medieval life existed on the margins of survival. Famine, illness, and injury were common. Kristin deals with all these at a fast pace. It is a lot like life: both long and too soon over, with no time to make sense of one challenge before another appears. Kristin’s crises of faith all face into the vicissitudes of daily life.

I found it a great and absorbing book. I sincerely and passionately hope that my friends will read it.

September 3, 2020

Your Kingdom Come

When I am awake at night, I often think my way through the Lord’s Prayer. That may sound like rote praying, but it’s far from that. I’ve found that the prayer reverberates inside me in a dynamic way, almost as though it were in dialogue with me. Over the years, I’ve experienced each of the clauses taking on different and deeper meanings, depending on my circumstances. The prayer speaks to me.

Lately, I’ve been focused on “Your kingdom come, your will be done on earth as it is in heaven.” I’ve found it a helpful backdrop for my anxiety in these terrible times.

I think everybody in America is suffering. There’s COVID and hundreds of thousands of deaths. There’s isolation and economic disaster. There’s racism and violence, tearing us apart. Centrally in all this, there’s the election. If you’re like me, you fear that the re-election of Donald Trump will scuttle our system of government—that authoritarian lawlessness will take over. (I’ve seen plenty of that kind of government in Africa, but I never, until recently, dreamed that it was possible in America.) Trump supporters fear something else just as much—the ultimate triumph of secularism and globalism, and the transformation of America into a place they don’t recognize. With such polarized fears, we are in for a hard time in the two months before the election—and perhaps after the election, as well. We will experience constant appeals to fear. We will hear lies and personal attacks. We will feel that our beloved nation is coming apart.

When I pray, “your kingdom come,” I’m imagining a timeline that supersedes our agony. I’m imagining God bringing a government of love that lasts forever. Our election turmoil hardly figures in the timeline of God’s plans. He has greater ends in mind. And he, not we, will bring them about. It’s not up to us. We ask him.

This doesn’t diminish the stakes of our election, but it reminds me that something far greater, and far better, is at play—and is in God’s hands. Cradled in that prayer, I can sleep.

August 26, 2020

Jacob Blake Matters

I don’t know Jacob Blake or the police who shot him. I don’t pretend to know exactly what happened. I do know that the video looks way too familiar, and it makes me sick. I don’t ever want to see another movie of police shooting an unarmed black man,

August 11, 2020

Memoir

Dear friends,

Just to let you know, I have published my memoirs under the title, A Gift: The Story of My Life. I wrote it for my grandchildren and great-grandchildren, but some of you have told me you would like to read it. With that in mind I priced it as low as possible–$5 for the paperback, $1 for Kindle. I very much enjoyed writing it, and I’m quite pleased with the result. It’s 138 pages and no pictures (except on the cover).

Thus far searching for it on Amazon is impossible, so use these links:

I’d be tickled if you wanted to read it.

Tim Stafford's Blog

- Tim Stafford's profile

- 13 followers