Sukhjit Singh's Blog, page 4

January 15, 2021

47. 84. 2020.

Walking through the tractor-trolley townships at Tikri and Singhu, one finds posters saying ‘Santali (47) Dekhi, Chaurasi (84) Dekhi. 2020 Dikhawange.’ Most of the youngsters who carry these posters on their tractors, trolleys and tents have only seen 47 and 84 through stories. But stories are powerful. We live in stories and stories live in us. However, there are some here, who define these posters.

Sardar Nachattar Singh Garewal was 13 years old at the time of partition. He remembers going with fellow villagers to walk Muslims from his village to the safety of camp Raikot. He remembers with much more clarity and detail his days in Nagpur during the pogrom of 84. He used to drive a truck and was on road when the killings started. He remembers parking his truck on roadside, removing a tyre, putting a jack and creating an impression of a broken vehicle. He remembers cutting his hair and beard. He remembers hiding in a Gurudwara and then hiding in cotton fields for days.

He isn’t hiding anymore. 84 Dekhi. 2020 Dikhawange. He stands tall, with his unions flag held high. He walks all day long chanting Inquilab Zindabad. As you approach and greet him, he breaks into a radiant smile and gives you hug, full of affection and kindness. And if you spend a few minutes with him, he makes you part of his story, he makes his story part of yours. And if you ask for a photo, he raises his flag and his arms, and his voice rings out Inquilab Zindabad. And when you say goodbyes, he embraces you in a hug again, a hug of brotherhood, a hug of blessing, a hug of memories, a hug for centuries, a hug for humanity.

HUMANS OF FARMERS MOVEMENT SERIES#3

#HumansOfFarmersMovement

#KisanEktaMorcha

JOURNEY IS THE DESTINATION

Ajeetpal Singh is a 2003 Chemical Engineering graduate. He worked with Maruti after graduation. He now runs his own event management firm. He is not involved in agriculture directly, but his family is. He wanted to create awareness about the farmers movement and contribute in what little way he could. So, around 20th December, he along with his family and friends, a group of 12 including elderly, ladies and children, started their journey from Anandpur Sahib towards Singhu on foot.

Anandpur Sahib to Singhu is about 290kms. They walked 570 kms covering many villages and towns on the way and reached Singhu in 12 days. They spoke with residents of villages they visited. They spoke with shopkeepers of the towns they crossed.

‘Our plan was to stay here for 4-5 days, but once we reached here and started sewa, we just don’t have the heart to leave.’ Ajeetpal’s throat chokes, his eyes water as he discusses his journey to this place about fifty meters behind the Sanyukt Kisan Morcha’s stage, where he spends is days cleaning, mending, polishing footwear of the farmers.

He was touched by the hospitality of the Haryana villagers wherever they stayed. And he was moved by the poverty of masses they crossed along the highways. ‘We were not carrying much with us. We had some clothes that we gave to few at one place. In no time there was a big queue of the needy.’ He is a gentle soul, there is pain in his words and water in his eyes as he says his words. ‘I had always heard that the journey is more important than the destination. Now I know.’

The sole of the shoe in his hand has come off on one side. He cleans the shoe with a dry cloth and picks up the tube of fixing lotion. He is cleaning and polishing his society’s soul a shoe at a time. He is mending its hurts a shoe at a time. His humanity seeps into those shoes and becomes a part of many other journeys.

HUMANS OF FARMERS MOVEMENT SERIES#2

#HumansOfFarmersMovement

#KisanEktaMorchaJanuary 14, 2021

MIDNIGHT AT SINGHU

It is dark. The tractor-trolley township at Singhu is asleep (mostly). A solitary figure walks its lanes with a stick in one hand. As he crosses an unlit section of the narrow muddy service road, which sees all the local traffic in the day, he turns on the torch light. Occasionally, he blows the whistle that hangs around his neck.

‘In the first few nights after reaching here, there were some incidents where tractor tyres were punctured. I started spending my nights walking along the camp. Initially I walked for a kilometer or two in one round. Now I walk longer route.’

His longer route is a round of about 7-8 kilometers. He starts at 8pm. He stays on his duty till 5am. He does five rounds during this time. 35-40 kilometers, every cold, foggy, wet, wintery night of this festival of resistance.

Wherever he crosses other group of volunteers, or those who are serving overnight langars – they greet him, they ask him to come sit with them - a talk, a story, a cup of tea maybe, next round he says.

Meet Bir Singh, 62 years young, with a spring in his steps and with God in his words. Walk with him. By the end of that one round of 7-8kms, you would have learned much from the ocean of knowledge that resides in this humble servant of society. He talks politics, he talks society, he talks of Farid, of Kabir, of Nanak, of Gobind, he recites them and explain it with the devotion of a beloved. He talks humanity.

Uth Farida sutteya duniya dekhan ja, shayad koi mil jaye baksheya te tu vi baksheya ja, Tureya Tureya ja Farida Tureya Tureya ja…

HUMANS OF FARMERS MOVEMENT SERIES#1

#HumansOfFarmersMovement#KisanEktaMorcha

January 10, 2021

HARVEST OF RESISTANCE

It was only a century ago a boy named Bhagat Singh, all of eight years, was growing guns in his fields.

(image credit - BKU Ugrahan FB page)

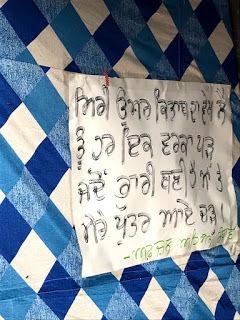

(image credit - BKU Ugrahan FB page)ਮੇਰੀ ਉਮਰ ਕਿਤਾਬ ਦਾ ਵੇਖ ਲੈ

ਤੂੰ ਹਰ ਇਕ ਵਰਕਾ ਪੜ੍ਹ ।

ਜਦੋਂ ਭਾਰੀ ਬਣੀ ਹੈ ਮਾਂ 'ਤੇ

ਮੇਰੇ ਪੁੱਤਰ ਆਏ ਚੜ੍ਹ ।

Open the book of my life,

Each and every page you read.

When mother faced threats

My sons have risen and led.

(Afzal Randhawa @ Tikri)

#KisanEktaMorcha

#StandWithFarmers

#SpeakUpForFarmers

January 8, 2021

PANJAB - Journeys Through Fault Lines

From the first words, ‘Je ho ji tu samjhe mahiya, Oho ji main hain nahin’ ‘What you know of me, my dear, I am not that’, as the epigram to the last words 553 pages later, ‘However, like all communities painted into a corner, Panjab is a lot about not accepting how anyone understands it,’ Amandeep Sandhu’s ‘PANJAB – Journeys Through Fault Lines’ is an attempt, not the first, nor hopefully the last, but a sincere, detailed, timely and a significant one, at understanding the enigma that is Panjab.

Born and brought up outside the state, Sandhu’s journeys to fill a Panjab shaped hole in his heart, provide the reader with an understanding of much that is hidden of the stories of this land of rivers, green revolution, bhangra beats, langars, and perceived prosperity in general, and gives us a peak into what ails it - the agrarian distress, fast disappearing watertable, pesticide-insecticide made toxic lands, cancer trains, mounting farm debts, and farmer suicides, and walks us through its many fault lines - a society deeply divided on caste lines, people hurt at state apathy towards the grain bowl of the nation, a generation still not healed from the injuries from the dark decades, from blue star and 84, a generation caught in the trappings of drugs, and a generation leaving the shores to dollar-lands.

In the epilogue Sandhu writes, ‘Throughout its long history, Panjab has always been more than its geography and its people. It has symbolized an idea of resistance and rebellion. In the past, in spite of grievous wounds, Panjab has always risen and proved its critics wrong. I believe that someday this Panjab too will rise to its challenges – in its own eclectic way.’

Should Sandhu have undertaken his journeys and made this call of his Panjab much earlier? Because it appears that Panjab has heard him. It has risen.

The fault lines are being challenged.

As one ‘journeys’ through the tractor-trolley townships of resistance at Singhu and Tikri, one sees and hears a call of ‘Udhta Panjab nahi Padhta Panjab.’

As the tractors, overloaded with youngsters and their enthusiasm, march past, one doesn’t hear ‘guns’ or ‘ganglands’ or loud sound with meaningless words. The sound systems on these tractors now sing of glorious past, of heroes, of revolution.

Kisan is here in large numbers. Majdoor has arrived. Dalit is supporting Jutt. Kirti Kisan, Kisan Majdoor, show up on union flags together at every few steps. Kisan Majdoor ekta is the resounding slogan.

Bebe is here. Mutiyar is here. Out of the boundaries of home and communities, they are at frontline, their support, strength and voice are here.

Faith is here. Its rigidity a little fluid.

In the first edition of Trolley Times, battleground publication of Farmer’s movement, Tanveer tells a short story of two farmers – ‘My neighboring village is Bappiana, District Mansa. Two farmers from there have gone to Delhi. To the sit in. Their fields share a boundary. One of them has a chicken farm. They had a quarrel and are not on speaking terms. One of them has sued the other. This morning, the one who has filed the case says to the other - “here, brother, drink tea”. He sits near him. After a while of silence, he says - “Brother, first thing when I get back, I’m going to take back my lawsuit against you.” Delhi has lost. Both have won the battle.’

The fault lines in Panjab are real, with deep roots. But this awakening gives it hope. A hope that can be built upon to find a way out of the ‘depression that gnaws at it and erodes it.’

At the beginning of his journeys, a friend advised Sandhu to look beyond the windows and doors of Panjab and try to see which pillars still stand. Another friend said, ‘If you want to understand Panjab, be ready to count its corpses.’

Sandhu concludes, ‘Having walked through the fields filled with corpses to which Danish had pointed, having looked at its windows and doors, I had found that the only pillars that stood in the ruin of Panjab were its resistance to power and hegemony. That was, that is and that will always be Panjab.’

In this festival of resistance, the bodies are piling up. The list of the ‘martyrs’ of the movement continues to grow. And from their ashes new pillars are rising.

It is too early to say which direction this movement will take and where this movement will take Panjab and its people. But there is a new hope. Panjab rises – ‘in its own eclectic way.’

#KisanEktaMorcha

#StandWithFarmers

#SpeakUpForFarmers

2020 – LOCKDOWN BOOKS REVOLUTION SERIES#3 -

PANJAB - Journeys Through Fault LinesFARMERS MOVEMENT – ADDRESSES & MILESTONES

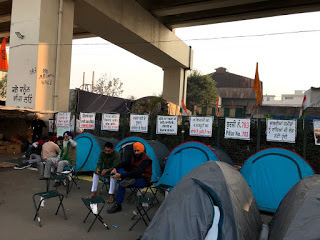

Baba Banda Singh Nagar, Chacha Ajit Singh Nagar, Bibi Gulab Kaur Nagar, Shaheed Bhagat Singh Nagar and Shaheed Sadhu Singh Takhtupura Nagar. Miles long tractor-trolley township of those struggling for their rights at Tikri is divided into these five cities named after historical personalities who represent a legacy of struggles.

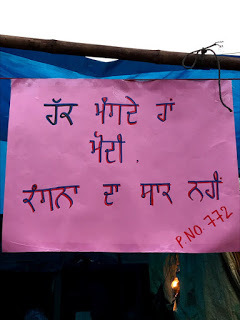

Under the metro line for a few kilometers, each metro pillar is an address for the homes the farmers have made for last seven weeks. Pillar 772 is Faridkotiyan da langar. Pillar 783 on one side is Shaheed Bhagat Singh Library and on the other side a tent city.

And as the coiled snake, that this tractor-trolley township is, unwinds for twenty kilometers away from the metro, markers appear – a new plantation of milestones and addresses.

Village Rodewala is here and so is village Aulakh. These are only a few miles from Sangroor and Kotkapura as the milestones indicate. Talwandi Malian welcomes you, ji aayan nu. A few miles away are Daya Kalan and Kishanpura Kalan. Somewhere in this tractor-trolley township there indeed breathes a Sangroor, a Kotkapura, a Daya Kalan and a Kishanpura Kalan.

Someone has taken up the challenge to raise Pind California. Welcome signs are up and half of the under-construction bus stand next to the road, where resistance lives for now, has already been converted to a comfortable lodging for females. As the labour employed by state continues to complete the construction of the bus stand, so does the labour of the volunteers stay busy making these half-completed rooms at the bus stand into livable lodges.

And in the cemented open space of this un-operational bus stand we meet Sihauda. There are fires burning in their chulhas as children, youngsters, elderly all work on getting their next meal ready. I look at clouds above and try to gauge if the skies can match the fire burning inside the residents of Sihauda.

Bapu Zora Singh, 74 years, welcomes me as he pads the mattress next to him. I jump over the rear door of the trolley. From a village in Sangroor we have soon found relatives who live in villages 5 miles apart. That’s much more acquaintance than required here in this township of resistance than if we were neighbours in the indifferent million bungalows and highrises a few kilometers away.

Their tarpaulin developed some holes so the water from last rain entered their trolley, half of their mattresses and quilts are wet and with no Sun these will stay wet for a while. But that is no deterrent to bapu ji’s spirit. When asked about his health – he says chardi kala, body and spirits are in a blessed high. When asked till when he will stay here – ‘ja tan jitke jawanage, ya marke,’ ‘will return victorious or dead.’

Over seventy deaths in seven weeks. The final address in the journey of many who joined this movement. Each passing day, the number on this particular milestone increases. Yet, the inconsiderate and indifferent tweet for Ganguly’s heart surgery and America’s Capitol Hill. For the moment there is no Sanjay who speaks truth to this Dhritrashtra.

Singhu, Tikri, Ghazipur, Chilla, Shahjahanpur, Palwal are now not just ordinary points on highways and expressways, that we crossed on our travels without a second thought (or while cursing the traffic jams at tolls). These are now names that bring with them images of tractor-trolley townships, roadside tent cities, and lacs of sons of soil raising their and in turn their people’s voice amidst biting winters and pouring rains and a short distance away from inconsiderate center of power and those indifferent millions dwelling in comfortable highrises and bungalows. These names are new addresses of a nation’s awakening and every setting sun, over a day and over a life, a new milestone on this journey.

#KisanEktaMorcha

#StandWithFarmers

#SpeakUpForFarmers

January 5, 2021

CHARLATANS & FREE SPIRITS

The market is in full swing. There are some selling socks – ‘6 jodi garam juraab 100 ke,’ there are few selling bags - from small handbags to full size luggage bags, there are many piles of jackets, shoes, belts, towels, there are a few cobblers, there are mobile cover kiosks, and there are few selling boiled eggs and omellete, fruits walas - guava in particular, and there are salad and chat walas. The market is tailored for the crowd that walks through it. Atmosphere is electric. The crowd more than any Sunday market in any crowded corner of any city.

Squeezed on one side of the highway, left open as pedestrian access by the security barricades, the market has come up on the path that everyone uses to reach the Singhu protest site, the main stage of Kisan Sanyukt Morcha and the tractor-trolley township beyond it. Ever since the stage of Kisan Majdoor Sangharash Committee came up on this side of the barricades the pedestrian traffic has zoomed and so has the number of sellers.

Adjoining the few hundred meters of the market is the barricaded section, now with a handful of security personnel, along with the state machinery for crowd control – the riot control vehicles and Varun – the water canon mounted vehicle. For now, the crowd flows uncontrollably, a river, having created their own channel. For now, the state machinery stands helpless, witness to and at mercy of the real power, people.

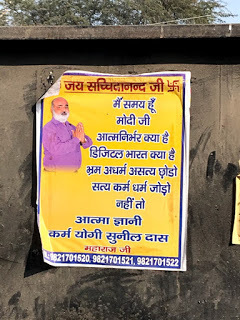

On the barricade raised along the walkway, where the river flows, a charlatan has left a message for another charlatan.

In the sky right above the state machinery, at the point that is marked as a border by the state, a solitary kite flies. It soars like the spirit of people underneath.

#KisanEktaMorcha

#StandWithFarmers

#SpeakUpForFarmers

January 3, 2021

THE RADIANCE OF A THOUSAND SUNS

‘A hundred million and more’ is a kind of dedication that isn’t obvious as one turns the cover and starts reading Manreet Sodhi Someshwar’s literary masterpiece ‘The Radiance of a Thousand Suns.’ As one starts this journey with Niki, at her arrival, born to Roop, under the watch of Biji, Zohra Nalwa, and in the fleshy, stout, ‘capable hands’ of Nooran, we meet partition and its ghosts, we see Punjab of 80s and its dark days, we find India and the madness of mass sterilizations and pogroms, and we find a cast of characters as resilient and deep as the land. We travel with Niki on her journey to complete her father’s unfinished book, we travel with her in search of Jyot, the thread that is woven with pain of 47, of 84 and of 9/11.

And amidst the myth and history, past and present, that surrounds Niki, we meet them. Aborted before they are born, illegally, because the family wanted a son, we meet these hundred million and more unborn girls.

At Singhu border, dressed in white salwar kameej, possibly her school dress, with a portable mike in her hand a young girl leads a group of girls and women. She says – Punjab Haryana, the group behind her shouts – zindabad zindabad.

It is Punjab and Haryana that have led the way in silencing those millions of voices. But… and hopefully this is that key moment… when these voices find themselves.

Dressed in track suit, she drives a tractor. Two girls sit on each side. The trolley behind the tractors is full of women, elderly with her heads covered in pallus sitting in the middle, young with their ponytails swinging and hair flying in the wind standing on the sides.

They come on their scooties. A march of scooties and girl power.

She is volunteering with NGOs and she is out in her schools, colleges, towns, cities organizing support for those sitting at various protest sites.

She is there reporting live, she is there compiling stories, and she is there publishing and distributing trolley times.

She is on social media, creating and supporting the narrative. She fights the IT cell and makes her own hashtags and trends.

She is on stage. Addressing gatherings with her knowledge, her passion, her strength.

She is a voice everywhere at these tractor-trolley townships.

This is that moment, hopefully, from where their voices will carry power to their hinterlands and homes. And those millions and more will not be voiceless anymore.

#KisanEktaMorcha

#StandWithFarmers

#SpeakWithFarmers

2020 – LOCKDOWN BOOKS REVOLUTION SERIES#2 -

THE RADIANCE OF A THOUSAND SUNSJanuary 1, 2021

PUNJAB HARYANA BAAEE BAAEE

Surinder from Mohali feeds dough balls to the roti making machine. The machine delivers 600 rotis an hour. The power for the machine comes from the lines passing along the highway. A few days back the officials came to remove their power supply, but the locals didn’t let them. They have now extended the wires to all trolleys, kitchens and lit up the open areas with halogen lights. Their colony has grown roots.

Their colony and their langar is right in front of a fairly famous highway dhaba – Rasoi. The owner is losing a business of many lacs a month but has opened the facilities for the protesting farmers. The langar runs from early morning to late evening. The hour I spend there with Surinder, the rows of the langar are full to capacity. Along with the protesting farmers, locals working around the area, poor from nearby shanties, travelers passing through, visitors, all partake of the langar.

Supplies? Surinder says after initial few days they haven’t had to touch their rations. Villagers from the region have taken over the supply. Someone brings wood, someone delivers dry ration, someone delivers vegetables or fruits, someone delivers milk and lassi, someone brings water tankers. Everyone in the region is contributing and supporting.

‘You should try the lassi they bring, it is the best.’ Before I say my byes to him a tempo with drums of lassi drives in. Tau with the tempo is from a village few miles away from the highway. ‘The whole village contributes. We bring a tempo of milk and lassi every day.’ How long will they continue? ‘As long as it takes.’ They fill a tub with lassi and drive to the next langar. I get a glass of it. Indeed, the best.

Surinder points me to a table laden with bread. Three days back some locals came with truck full of bread. They have been serving bread pakoras with tea for few hours every morning last two days and the bread will last them another two. I see similar piles of bread at few other langars, voluntarily and anonymously offered.

I am sitting with Balwinder Singh ji from Fatehgarh, a few kilometers from where Surinder has set camp. ‘We haven’t even touched the atta we brought.’ Just to prove the point, at that very moment a young Harayanvi approaches with folded hands, ‘Sardarji aatta laye hain’. Balwinder ji tells him that they have plenty for the moment. The young man insists, ‘please take one bag.’ Balwinder ji shows him the stock. The young man reluctantly moves towards the tempo laden with aata with a promise ‘fir aayenge’ and heads to next langar. Balwinder ji says -‘It is unprecedented, they thought that they could bring the Sutluj Yamuna Link issue and divide Punjab and Haryana. The region has shown that there are some links older and much stronger.’

Ever since a Punjabi baba answered a reporter’s Hindi query with, ‘Modi ko to mookiyon naal kutega jake,’ he and his commandment has gone viral. And Harayanvi pugilists have joined these Punjabi pehalwans with fervor. The differences that borders created or were meant to create have been erased for this moment.

Surinder says, ‘living in Mohali, he moves through Panchkula, Chandigarh and Mohali every day.’ For him these state borders have never existed. For the moment Punjab Haryana stand together Baaee Baaee, as brothers, once again.

#KisanEktaMorcha

#StandWithFarmers

#SpeakUpForFarmers

THE YEAR OF THE RUNAWAYS

In Sunjeev Sahota’s ‘The year of the runaways,’ Avtar, Randeep, Tarlochan, Gurpreet and many others, having made it to UK – via dangerous journeys on illegal routes, with help of visa-wives, under the guise of study visas, having jumped tourist visas – share a rundown house in Sheffield as they struggle for survival and as they attempt to open the doors to a future that they believed they would find here when they undertook those journeys.

They work sixteen hours x seven days to make less than eight hours x five days of ‘legal’ residents as the contractors exploit them, they sleep few hours a day with their little bags packed in case of immigration office raids, they sleep under bridges in freezing nights, they undercut each other to stay on jobs, many a times they fight, they brave sickness and injury, they leave the one who needs hospital care at the emergency doors when there is no other option – as deportation awaits at the other end of hospital exit, they make it through a day at a time, a week’s worth of earning at a time, a work season at a time, they make it alive through a year, through the year of the runaways.

She takes the mike on stage of Kisan Sanyukt Morcha at Singhu Border, ‘Main New Zealand to aayin haan, Delhi airport to siddha ethe protest te, tuhade naal baithan.’ ‘I have come from New Zealand, from Delhi airport straight to protest site, to sit with you.’

He takes the stage of Kisan Majdoor Sangharsh Committee, ‘meri flight si London di December shuruat vich. Hun cancel ai. Jad tak aapan jit nahi jande.’ ‘I had flight for London in the beginning of December. Now it is cancelled. Till the time we don’t win this.’

The banner at a langar reads – ‘Midland Langar seva society.’

A poster on trolley reads – ‘Doaba Kisan March, with the support of NRI brothers.’

Everywhere in these miles of tractor -trolley townships, the runaways, having graduated to become affluent diaspora, show their presence.

They have joined the five boys of KisanEktaMorcha IT Cell in millions and spread the word to every corner of the world.

They have organized rallies in their cities, they have got the parliaments of the world to take notice, they have not allowed the state, the sold-out mainstream media and Joseph Goebbles of our times, the BJP IT cell, to let this movement fall in a voiceless vacuum.

The runaways have stood up and made themselves counted.

#KisanEktaMorcha

#StandWithFarmers

#SpeakWithFarmers

2020 – LOCKDOWN BOOKS REVOLUTION SERIES#1 -

THE YEAR OF THE RUNAWAYS