Deborah Kalin's Blog, page 2

February 10, 2016

2016-02-11 07:12

Spent yesterday and will spend today trying not to notice these poor choking babies

February 9, 2016

2016-02-09 19:43

Today brought me two more books to add to my reward reading pile and I can't start any of them until I've finished reading the current book, gotten back on track with writing the current manuscript, written up seven key selection criteria answers, caught up on the day job backlog, drafted some blog posts and just generally got my life in control. Torture

February 6, 2016

2016-02-06 20:11

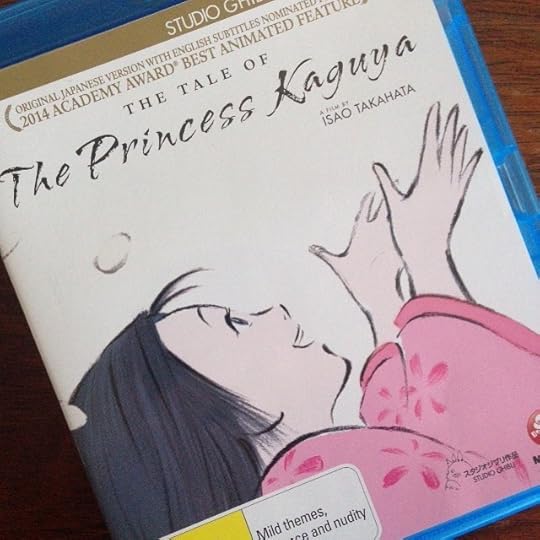

Last night's viewing: Studio Ghibli's "The Tale of Princess Kaguya"

I absolutely adored it. Although (keeping in mind it was about a fully grown thumb-sized woman discovered in a glowing bamboo shoot who spontaneously transformed into a newborn and who then grew into adulthood in the space of 6 months or so…) it jumped the shark when the moon people appeared

February 4, 2016

i really do spend an inordinate amount of time counting

Squawk doesn't quite get Hide & Seek.

Usually, she hides in the same spot used in the last round. If she does come up with her own, it's the cat tunnel.

Where's Squawk…? Oh, she's behind the door. Where's Squawk…? Oh, she's behind the door. Where's Squawk…? Oh, she's in the cat tunnel.

It gets a little repetitive.

Last night, though, things changed. I was up to 9 when she backed out of the cat tunnel and said, with emphatic hand gestures to wait, wait, "I want to hide somewhere else."

Breakthrough!

So I started the count again, while she hared off out of the room. This, I thought, was going well. Finally, she had grokked that last vital aspect of the game, the part where the seeking was meant to be done in earnest, the joy of the mystery and the anticipation and the hunt. At last we would not need to feign ignorance of her hiding spot.

Then she raced back into the room, caught my eye mid-count (I was up to 9 again), pointed, and said, "I'm going to hide under the table!"

So close, and yet so far.

January 31, 2016

A tiny pictorial of my dayjob. #latergram #doodlesofinstagram

A tiny pictorial of my dayjob. #latergram #doodlesofinstagram

A photo posted by Deborah Kalin (@deborahkalin) on Jan 31, 2016 at 4:47pm PST

January 29, 2016

toddlers and writing and making it work

I normally* get up at 5:30am so I can get 1-1.5 hours to myself purely for writing.

*It invariably doesn't work out at all. Squawk will wake at the same time and set up such a hollering that no writing gets done; or she'll have woken up so many times overnight I'll sleep through my alarm and still emerge sleep-deprived and shambling.

But I continue to at least try to make it work. About 20% of the time, I just have to prioritise sleep and let the writing go, much as I hate it. On about 30% of nights, I'll get up as planned and write as planned. On the nights she wakes me mid-slumber — and yes, this is one of them! — I'll settle her and then creep off to my study to write. I'll still have far too little sleep, and broken besides, but at least I'll have written. (The quality of it … well, I'm trying not to think of that part so much. I'm working on a first draft these days, anyway.)

Yesterday morning proved a little harder. I slept through my alarm because Squawk woke me at 2:30 and re-settling myself took just long enough for 5:30 to hit me right in the deepest part of the sleep cycle.

When I did wake at 6:20, and realised how little time I had left to myself, I nearly gave up. But I got the heck up anyway, because I've been giving up too often of late, and I'm sick of myself.

Squawk, however, was already awake and, seeing me slink down the corridor towards the study, she immediately begged to come and sleep in my bed.

I nearly gave up again. But instead, I dragged my laptop with me into her bed, and told her quite firmly she had to keep her eyes closed and try to sleep until “the sun came out” (she has a gro-clock) at 7, and if she could do that then I'd sit with her. (Yay for the king single mattress I bought her just the other day which means I now have the actual room to do this without cracking my spine in 3 different places.)

She duly promised — and duly failed to keep it. Of course. But she was quiet and cuddled up to me for a good ten minutes before she started to speak, so I didn't nag her about closing her eyes. I just wrote, and let her watch. I don't think she's ever seen me type at full speed before; I just let it blast out of me because I only had 40 tiny minutes before she was allowed to get up, and far less before she started to chat.

And Squawk, bless her supportive little heart, with her head snuggled into my left elbow, started to chant very softly under her breath as I typed: "Go! Go, go, go! Keep going, mummy … keep going, keep going … "

Turns out even writing is better with cheerleaders.1

For mums who write and want to know: she’s three. I’ve not tried this before, and I don’t think it will be a routine, but as an emergency for those days when I really want to write and she really can’t sleep, it might work. Although I find the first try at something works fine, and then there’s a whole string of frustrating failures because those next times she’s bored and cranky and just won’t shut the eff up.

January 24, 2016

the twelve planets, for enquiring minds

I've had a few enquiries of late about which books came before mine in the Twelve Planets series, and what exactly is the Twelve Planet series, and should I read them all?

(The short answer to this last being: yes! The slightly longer answer being: it depends on whether you want to read new things — which of course you do, right?)

I've been watching this series for so long, I sometimes forget not everyone knows about it! So for those who don't, here's the list.1

Nightsiders, by Sue Isle Amazon

Love And Romanpunk, by Tansy Raynor Roberts Amazon

Thief of Lives, by Lucy Sussex Amazon

Bad Power, by Deborah Biancotti Amazon

Showtime, by Narelle Harris Amazon

Through Splintered Walls, by Kaaron Warren Amazon

Cracklescape, by Margo Lanagan Amazon

Asymmetry, by Thoraiya Dyer Amazon

Caution: Contains Small Parts, by Kirstyn McDermott Amazon

The Secret Lives of Books, by Roasleen Love Amazon

The Female Factory, by Lisa L. Hannett & Angela Slatter Amazon

Cherry Crow Children, by Deborah Kalin Amazon

The Moth Cycle, by Isobelle Caromdy (forthcoming)

I read the whole series in order in the middle of last year; this year Stephanie Gunn and Ju of The Conversationalist will be doing the same, and blogging their reviews in far more detail, one book per month. If you're interested, you can follow along at A Journey Through The Twelve Planets.

Links are, for the moment at least, only to Amazon, but the books are available through other e-tailers such as Kobo and Smashwords. Paper copies for those which haven't sold out are still available from the publisher directly. Your local bricks and mortar store may or may not stock any copies, but should be able to order one in if you ask.

January 19, 2016

the very hungry caterpillar

A photo posted by Deborah Kalin (@deborahkalin) on Jan 19, 2016 at 3:17pm PST

January 17, 2016

the ecology of monsters

Cherry Crow Children features stories built around the idea of fate being sealed by personality. The idea that, even in a setting where a multitude of monsters stalk our daily lives, the one which ultimately claims us is successful not because it’s the most fearsome or the most powerful or the most tenacious, but because it embodies, and so occupies, our blind spot.

Naturally enough then, each of the stories started not with a character, or a setting, or a monster or community, but with all at once. The community and the geography and the monsters were all one and the same, each having adapted to the others over time and flourished because of it. Everything was inextricably entwined, reflecting and echoing aspects of each other, creating an ecology that was both physical and psychological. Without a doubt, these four stories are the most organic I've ever penned.

Because I was working with fate stories, I wanted a sense of inevitability and an ever-present, pressing feeling to the worlds. So I put each story in a geographically isolated town, to ensure each had credibly developed in relation only to its own unique environment; and I made the towns small, to make for a strong sense of community, banded together against oft-hostile surroundings.

These two factors alone immediately made the stories about the options available for individuals in tight-knit communities, and what happens when one’s aptitude goes against expectations. I distinguished each town by the type of its isolation — a mountain summit; the bottom of a deep valley; a desert outpost; a tractless alpine forest — and it’s fascinating to me how each terrain produced such different societies. In some of the stories I knew the terrain first; in others, it was the community’s values and ideals. In each, I made the two mirror and magnify each other.

Thus The Wages of Honey features a town spanning the broken summit of a mountain, where the streets are cut in half by sudden drops or looming cliffs, where bridges stand permanently half-finished, where floors and roofs are never of a level. Patterned after and adapted to their geography, the townsfolk speak in fragments and answer questions with vagaries and obfuscations. All this jumbling spoke to me of the vista between honesty and dishonesty, whether lying by omission constitutes lying in truth, at what point one ends and the other begins — and, of course, the costs of either choice. And out of that came the town’s monsters. I named them thorn girls: ghostly waifs, enticing and sharp, who were summoned by lies and made wistful by truths.

The village of Briskwater crouches at the base of a dam wall, where nothing but moss and lung rot can grow. The villagers’ livelihoods depend entirely upon the river, and upon holding its killing power at bay. Everything in the town and story, then, references death and water. Mould grows rampant; spray hangs in the air; and the little dead girl, water dripping constantly from her dress, walks among them, waiting for them to come to her. She’s yielding, and quiescent; she hunts by waiting and kills by accepting. All of the stories in the collection touch on the fear that being yourself earns punishment, but it was the writing of The Briskwater Mare which brought that theme into focus for me.

In The Miseducation of Mara Lys, I started with a single premise: that the most prestigious position in society, a clockmaker, was always a blind person. That the school which trained the clockmakers in fact demanded blindness. It was a compellingly horrific thought: how would such a practice form and inform the society surrounding it? It was also the perfect metaphor for a society which prided itself upon being a meritocracy — which, of course, like any attempt to sort on talent and aptitude, is eventually crippled and corrupted by socio-economic factors advantaging some at the cost of others, and only those occupying the most privileged positions can afford to remain blind to the inequalities which helped lift and keep them there. The corruption is reflected in the world Mara encounters: grubs chew away at the academy’s foundations, staining and pitting the stone; the library she revered has become a mechanism for locking away knowledge. As in a desert, where every life must go into feeding another’s and the very air will drink a person dry, everything in Mara’s world is being eaten from the inside out. And for such a relentless environment, it made sense that its creatures – monster and human alike – would be similarly relentless, simultaneously immune to time and a part of making it.

The Cherry Crow Children of Haverny Wood began with the creatures: the cherry crows flitting through the forest; the coffin dogs, screaming at their grisly feasts of a night; and of course the forest itself, preying upon the people who dare tread its byways. It was such a close, oppressive, unpredictable atmosphere, I knew at once the only society which could survive there was one which either prized the unpredictability and enforced solitude, or one which scorned it. It took me several drafts before I realised there were in fact two societies hidden among those trees, one of each — the wild and creative sourkinde, children of the forest who staved off death by embracing its inevitability; and the staid and suspicious Haverners, who disdained any form of dreaming and found safety in such a degree of routine and repetition that it stifled their ability to raise any questions.

Individually, the stories are (for me) tales of isolation, grim wonders, and inner landscapes laid atop the world.

Taken as a whole, they’re a promise that the monsters which haunt and hunt us are of our own making, formed out of the creatures we accept into our lives, even (especially!) if that be by ignoring their presence. Because, for me, true terror isn’t in fangs or claws, but lies instead in what lurks beneath the known and familiar. It lies in our choices, conscious or otherwise, whether the consensus be willing or not. What will we accept? To what will we turn a blind eye, and why?

—

Buy Cherry Crow Children now via

January 14, 2016

the bird behind the cherry crow

For "The Cherry Crow Children of Haverny Wood", I knew the title before I knew the story — which meant I knew the name cherry crow before I knew what the crow itself would actually look like.

They were one of the first things I pondered, then, in trying to uncover the story. Why were they named cherry crows — was it to do with their appearance, or their diet, or something else entirely? Why did the villagers of Haverny Wood fear them, and were they right to?

Beyond mythology and folklore, most of which draws from the northern hemisphere, I'm not all that familiar with crows — my little corner of Australia is home only to ravens. They were far too large, and far too sorrowful, to be the model for the cherry crow. The name implied to me a lightness of wing, a speed and flick-turn-ability, and a keenness of purpose. Nothing like the pondering, mournful ravens.

But there is another Australian bird, one of my favourites, that perfectly fit the bill: the Grey Butcherbird:

Butcherbirds get their name from their habit of hanging captured prey on a hook or in a tree fork, or crevice. This 'larder' is used to support the victim while it is being eaten, to store several victims or to attract mates.

— Birds in Backyards

— photo by @degilbo_on_flickr

I absolutely adore these fearless little fliers.

They have the loveliest song, sweeter even than the Australian Magpie's carolling, and they love to play.

At my mother's house, we have a game of throwing pieces of meat high in the air so the butcher birds can catch it on the wing. The magpies and kookaburras will eat out of your hand, if you've the patience and the daring, but the butcher birds prefer to hunt. Or perhaps they just like the adulation my family heaps on them for their quick turns and precise catches. They perch on the roofline, and watch us sideways until we throw, and then launch themselves at the flying-falling meat, often twisting on to their backs to catch it.

For the story, I made them red and black, to match the name, and I made them willing to attack humans.

[Claudia] stepped into the patchwork shadows of the trees, and the bush closed in around her—offering, for the first time in her life, true solitude.

Her skin crawled with it.

Despite the passage of months, the black of burnt things was still conspicuous, crumbling charcoal edges stark through the white clumps of last night’s untracked snow.

The fire-crumbled undergrowth shifted and crunched with her passage; the ghostly sallee and the stunted stringybarks alike all groaned of listing backs. Brushtails lurked in the empty branches, too hungry to sleep, beady eyes watching from their pointed faces.

And beneath the wind’s bluster, setting her nerves to twanging, came the crow-song.

There was no mistaking the liquid melody, calling of blood and slashed flesh, which warned of those red and black birds, small as a fist and swifter than sight. Most of the calls were distant, but that didn’t slow the drumming of her pulse. The cherry crows must be as hungry, these fading days, as every other forest dweller.

Following the closest call, with no warm and wary body at her back, set Claudia’s every sense on edge. She kept scanning the branches for silvereyes, since they were a sure sign no predators lurked, but their flittery little bodies remained unnervingly absent. Instead, the crow-song grew louder and the grey boughs began yielding up pockets of fine-shredded flesh stuffed into crooks or crevices.

…Each larder she passed brought her closer to the crows, the meat increasingly pink and moist, blood still dripping from some. At least there were no human eyes today.

— photo by @sunphlo

Can't you just imagine one of these little birds, watching you from the trees as you pass by beneath, wanting your eyeballs for its larder?