Kim MacQuarrie's Blog: Peru & South America Blog, page 2

September 7, 2015

Life and Death in the Andes: The Strange Places Book Ideas Come From

Life and Death in the Andes’ Travel Route

The journey down the spine of the Andes, from Colombia to Tierra del Fuego, actually began several years before I left. The idea for such a voyage had been in the back of my mind for several decades, actually, but didn’t crystallize until I finally pitched the idea of a book to my editor at Simon and Schuster, Bob Bender, in 2009. If you really want to know how far back this idea extends, however, it’s best summarized in the first part of the preface of Life and Death in the Andes:

When I was a boy, growing up in Nevada, during the long hot summers I used to read a lot. On burning days when the temperature outside hovered well over a hundred degrees and when if you tried to cross an asphalt street you quickly seared your bare feet, I would remain inside, lie on my back on our floral-patterned couch, open a book–and almost immediately would find myself plunging across icy seas or tunneling deep into other worlds. One of my favorite authors growing up was a German-American sailor named William Willis, who wrote true-life accounts of his various adventures. Willis had sailed on a square rigged ship as a teenager and, later in life, eventually made his way to the western coast of South America. There, he lashed together some balsa logs and sailed across the Pacific Ocean—for no other reason than adventure. Willis’ descriptions of being alone on his raft at night, peering down into an inky blackness where he witnessed great luminescent creatures rising from the deep, still haunts my imagination. At around the same time, when I was about eight or nine years old, I stumbled across Edgar Rice Burrough’s “hollow earth” series, which tell the tale of how a man burrowed down through the Earth’s crust with a machine, only to discover an exotic, interior world called Pelucidar. Within the Earth’s interior, it turned out, existed a world full of half-naked tribes and powerful beasts (mostly dinosaurs), rich, luxuriant vegetation, beautiful women, and so much adventure that I remember spending an entire summer there, immersed in a world as far removed from the deserts of Nevada as the Earth is from Mars.

1st (1922) edition of Burrough’s “At the Earth’s Core”

Many years later, after eventually becoming a writer and documentary filmmaker, I was touring with a film I’d recently made on the rainforest, a film that explored the spirit world of a certain Amazonian tribe, when a magazine writer asked me what had motivated me to spend so much time in the Amazon. Without even thinking, I blurted out “Edgar Rice Burroughs.” And, upon reflection, I realized it was true. Surprised, the journalist told me he’d gone to public school with Burrough’s grandson. About a month later, a package arrived at my door. Inside was an original edition of Burrough’s At The Earth’s Core, published in 1914, the first in the “hollow earth” series. Burrough’s grandson had written an inscription on the frontispiece, saying that his grandfather would have been pleased to know that his work had propelled me to the far reaches of the Amazon. It was while fingering through its pages that I realized that some of the worlds we visit in books when we are children become so buried within our minds that, even though they may remain deeply submerged, they still may prompt us to later subconsciously search for them—much as adoptees might search for their biological parents, or as adults might search for long-lost childhood friends.

Although motivation remain as mysterious as creatures of the deep, I do credit Burroughs with having planted a seed that eventually took me to South America, a continent that, in many ways, contains everything that the best of Burrough’s writing ever did: a massive mountain chain, epic in its proportions; colossal continental plates that continually collide, thrusting up volcanoes and even lifting lakes twelve thousand feet up into the air, and a cloud-wreathed rainforest that stretches more than half way across the continent–a jungle so replete with sloths, giant snakes, bizarre animals and un-contacted tribes that you’d think you had somehow left the modern world and had stumbled into a world as primeval as that of Pelucidar.

If you’re curious, you can read the entire preface here:

Next Up: Getting Ready For a Journey the Length of South America

The post Life and Death in the Andes: The Strange Places Book Ideas Come From appeared first on Kim MacQuarrie Author and Filmmaker.

September 2, 2015

Life and Death in the Andes: How an Epic Journey Came About

Life and Death in the Andes: On the Trail of Bandits, Heroes, and Revolutionaries

The Behind-the-Scenes Story of a 4,500-mile Journey Down the Andes and the Book that Came From it

Entry from my travel journal:

Bogotá, Colombia

At the Centro García Márquez, which is near the La Casa de Moneda and the Botero Museum in Bogotá, Colombia, there’s a large bookstore, built on a circular plan, and a café on the corner. I’m seated at a table in front of the café, the wind rustling the pages of my journal, low gray clouds scudding overhead. Bogotá is a city of red brick and gray buildings, with a knife-like, dark green thrust of the Andes emerging from one side, looming over the city. Hopefully, the weather holds as tomorrow I’m planning on visiting Lake Guatavita, about 40 miles northwest of the city, where the legend of El Dorado comes from.

Yesterday I met and interviewed retired general Hugo Martínez, who a little over twenty years ago brought down the drug czar, Pablo Escobar. The general arrived for the interview at 3:45 P.M., wearing a dark blue suit and slacks, hair still dark black with streaks of gray, six feet tall, lean, a mole on his left cheek, eyes close set like those of my grandfather, but friendly, enthusiastic, not like his portrayal by Mark Bowden in “Killing Pablo.” The general said that he has read my most recent book, “The Last Days of the Incas,” in Spanish, and had liked it. He’d been to Machu Picchu twice, he said, the last time with his family and had driven there from Bogotá. He was going to go again and hike the Inca Trail, with another retired Colombian general, but at the last minute his friend had been appointed to some government post which, in the end, hadn’t gone too well (“Salió mal,” he said, shaking his head).

The general talked non-stop from 3:45 PM until around 7:00 P.M., pausing only to take a sip of water. Although I had questions prepped for the interview, I somehow never used them, as the general tended to launch into entire, rather spell-binding stories, myself interrupting only occasionally to guide him back to points I was interested in, or wanting to make sure that I understood. The red light on my small digital recorder glowed the entire time. The general’s story of tracking down and locating Pablo Escobar was more involved and suspenseful than I had originally read, and now I was hearing it in the first person. Martínez explained how his son had been the one to locate Escobar’s safe house, was only 23 at the time, and that it was a fluke that he had happened to be in the vicinity and was the officer who had ultimately tracked Escobar down. The general told me that he never talked about these things, that he never talks about Escobar to anyone, not even to his family. But he had liked my book, so he had agreed to meet with me. Tomorrow, I’m leaving for Medellin, where I hope to retrace some of the general’s and Escobar’s paths, and where I also hope to meet Escobar’s brother, Roberto, free now after more than a decade in prison.

**

Next up: Putting the book idea together

Life and Death in the Andes Travel Route

The post Life and Death in the Andes: How an Epic Journey Came About appeared first on Kim MacQuarrie Author and Filmmaker.

September 1, 2015

Enter Giveaway for a Free, Signed Copy of “Life and Death in the Andes”

Goodreads Book Giveaway

Life and Death in the Andes

by Kim MacQuarrie

Giveaway ends September 15, 2015.

See the giveaway details

at Goodreads.

The post Enter Giveaway for a Free, Signed Copy of “Life and Death in the Andes” appeared first on Kim MacQuarrie Author and Filmmaker.

August 26, 2015

The Last Days of the Incas Television Series

My book, The Last Days of the Incas, is currently a 13-part series in development at the FX Channel. Click below to watch the original trailer.

The post The Last Days of the Incas Television Series appeared first on Kim MacQuarrie Author and Filmmaker.

August 16, 2015

Life and Death in the Andes–A Voyage From Colombia to Patagonia

Life and Death in the Andes

In 2011 I set off for a 4,500-mile road, boat, bus and train trip down the Andes of South America, from Colombia in the north to Patagonia and Cape Horn in the south, while working on a book that eventually would be called Life and Death in the Andes: On the Trail of Bandits, Heroes, and Revolutionaries. It’s due to be published on Dec 1, 2015 by Simon & Schuster. On the way, I naturally took photos, lots of notes, and video, some clips of which I will gradually post as well as extra materials that never made it into print. The following is my new book’s description from the publisher:

Unique portraits of legendary characters along South America’s mountain spine, from Charles Darwin to the present day, told by a master traveler and observer

The Andes Mountains are the world’s longest mountain chain, linking most of the countries in South America. Emmy Award-winning writer and filmmaker Kim MacQuarrie takes us on a historical journey through this unique region, bringing fresh insight and contemporary connections to such fabled characters as Charles Darwin, Pablo Escobar, Che Guevara, and many others. He describes living on the floating islands of Lake Titicaca, where people still make sacrifices to the gods. He introduces us to a Patagonian woman who is the last living speaker of her language, as he explores the disappearance of indigenous cultures throughout the Andes. He meets a man whose grandfather witnessed Butch Cassidy’s last days in Bolivia and the school teacher who gave Che Guevara his final meal. MacQuarrie also meets the Colombian police officer who made it his mission to capture Pablo Escobar—the most dangerous cocaine king in the world.

Through the stories he shares, MacQuarrie raises such questions as, where did the people of South America come from? Did they create or import their cultures? Why did the Incas sacrifice children on mountaintops—and how did these “ice mummies” remain so well preserved? Why did Peru’s Shining Path leader Guzmán nearly succeed in his revolutionary quest while Che Guevara in Bolivia so quickly failed? And what so astounded Charles Darwin in South America that led him to conceive of the theory of evolution? Deeply observed and beautifully written, “Life and Death in the Andes” shows us this land as no one has before.

Below is an initial clip from the journey, this one from La Paz, Bolivia, where the festival of the Candelaria happened to be revving up as I was journeying ever southwards.

You can pre-order Life and Death in the Andes here

The post Life and Death in the Andes–A Voyage From Colombia to Patagonia appeared first on Kim MacQuarrie Author and Filmmaker.

March 9, 2015

Global Warming and the Andes’ Shrinking Glaciers

The stranded ski resort of Chacaltaya, just outside of La Paz, Bolivia

(Excerpt from the book: Peru: Country of Mountains–In the Shadow of Global Warming by Wust Ediciones, 2014)

By Kim MacQuarrie

“And isn’t it a bad thing to be deceived about the truth, and a good thing to know what the truth is? For I assume that by knowing the truth you mean knowing things as they really are.” –Plato

It was a few years ago when I was visiting La Paz, Bolivia, that I first heard the story about an Andean ski resort that had lost its glacier. The resort’s name was Chacaltaya and it had been in operation since the late 1930s. The resort operated upon a glacier about twenty miles from La Paz, a glacier that had been there since the last Ice Age. At over 17,000 feet, the resort was the highest lift-served resort in the world and, since it was the only ski resort Bolivia possessed, the country’s Olympic ski team naturally used to train there. By 1980, however, half of the glacier had melted and the process seemed to be accelerating. By 2009, only seventeen years later, the glacier had completely disappeared. Not surprisingly, Bolivia no longer has an Olympic ski team. Now, like some beached whale, the wooden ski lodge still sits there, forlornly waiting for guests who will never again appear.

The story of the Chacaltaya Glacier, of course, is hardly unique. During the last 10,000 years, since the Earth began emerging from the last Ice Age, Andean glaciers have shrunk by more than 90%. The majority of that shrinkage, however, has taken place during the last 200 years, since the onset of the Industrial Age. And the acceleration is continuing: Andean glaciers have retreated 30-50% in only the last thirty years. Since glaciers are an important source of water for farmers, cities, and towns throughout the Andes, especially during the dry season, it’s a fair question to ask why South America is losing its glaciers in the first place.

Shrinkage of the Chacaltaya Glacier

To answer that, we need to go back two hundred million years, when South America was joined to Africa and both continents were part of a single landmass called Pangea, surrounded by an immense ocean. After Pangea’s breakup, South America split off and eventually became an island, drifting slowly westward on its tectonic plate. For some eighty million years South America remained cut off from the rest of the world, with evolution producing a plethora of unique animals and plants—at first dinosaurs and later an explosion of marsupials. Eventually, the island of South America began colliding with the Nazca Plate, which moved eastwards, hitting South America head on. About 40 million years ago, that collision began to produce a range of mountains that would later be called the Andes. About three million years ago, the oceans sank as the Ice Age began and an isthmus joining North and South America became exposed, allowing a deluge of new fauna to enter the continent. Eventually, about 20,000 to 30,000 years ago, the first people crossed the land bridge and walked into South America.

The world those first inhabitants beheld was one quite different from that of today—it was a world populated by cave bears, saber tooth cats, and sloths that weighed up to 10,000 pounds and were as large as automobiles. The Andes Mountains, meanwhile were still in the grip of the Ice Age with thick, enormous glaciers and abundant snow. Bringing their languages and tool kits with them, the first inhabitants began to explore ever southwards, eventually heading up into the Andes where they survived by hunting and gathering, using furs and fire to protect themselves from the intense cold.

Around 15,000 years ago, as the Ice Age began to retreat, people were forced to either adapt to changing conditions or perish. By now, many of the large mammals had disappeared—due presumably to both intensive hunting and to the changing environment. Around 8,000-10,000 years ago, the first signs of agriculture began to appear. People also began to selectively breed wild guanacos and vicuñas, creating two new species in the process: the llamas and the alpacas. Gradually, hunter gatherers became farmers and farming began to slowly spread through the Andes. With increased production of potatoes, quinoa, corn, squash, peanuts, and chilies, populations soon began to increase and social classes began to emerge. It was during this period that the first temples and ceremonial platforms began to rise, constructed by societies now composed of priests, nobles, artisans, metallurgists, warriors, and peasants working the fields.

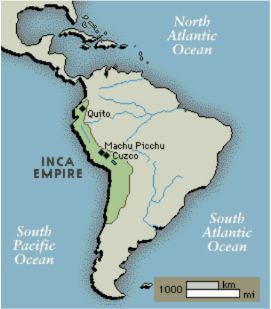

The Andes Mountains, meanwhile, not only collected rain and snow that soon became rivers and could be used for irrigation, but the sheer verticality of the landscape also created what anthropologists call a “vertical archipelago.” The Andes thus resembled an enormous skyscraper—with each “floor” containing different kinds of micro habitats that could be planted with different types of crops. Meanwhile, as the Andes Mountains continued to rise, states and empires rose and fell, eventually producing the Inca Empire, which ultimately spread across 2,500 miles—the largest indigenous empire ever to have existed in the New World.

That the Andes provided an abundance of resources—glaciers being only one of them–and that the native people who lived there had learned to master these resources, is reflected in some of the first reports by Spaniards who began arriving in the early 16th century. Spanish conquistadors quickly discovered a vast system of Inca roads (some 26,000 miles of them, called the Qhapaq Ñan, or “Royal Road”). Alongside the roads stood innumerable warehouses, most stuffed to the ceilings with goods and produce. According to the conquistador, Pedro Sancho de la Hoz,

All the steep mountains…[have roads] of stone…Most of the people on these mountains live on hills and on high mountains. Their houses are of stone and earth [and] there are many houses in each village…Every seventy miles there are important cities, capitals of the provinces, to which the smaller cities brought the tributes they paid with corn, clothes, and other things. All these large cities have storehouses full of the things that are [harvested from] the land….[there are plenty of] vegetables and roots [potatoes, okra, etc.] with which the people sustain themselves and also good grass like that in Spain…There are many herds of sheep [llamas and alpacas], which go about in flocks with their shepherds…The people, as I have said, are very polite and intelligent and always go about dressed [and] with footwear.

Although the Andes provided a rich and varied habitat, the mountains were nevertheless prone to frequent earthquakes, exploding volcanoes, and occasional droughts. The Incas believed that the mountains contained gods and that gods controlled the abundance of food, water, animals, and crops. They not surprisingly made offerings to them. Normally these offerings were of coca leaves, corn, finely woven cloth and animals, such as guinea pigs, llamas, or alpacas. Occasionally, however, at times of great duress, the Incas made human sacrifices. On top of a dozen or more peaks in the central Andes, archaeologists and explorers have discovered the sometimes perfectly preserved bodies of Inca children–offerings made to the mountain gods in a desperate attempt to restore balance and harmony to their world.

Inca Ice Maiden

Five hundred years later, science has provided us with a far deeper understanding of the Andes than the Incas had. We now know that the Andes are partially held up by the force of the impact of the Nazca Plate sliding beneath the South American Plate. The force of that impact, it turns out, acts as a kind of flying buttress, pushing the Andes skywards at the same time as helping to hold them up. The Andes themselves are actually a giant pile of the Earth’s crust, the ongoing remains of an enormous train wreck that is unending, the crust in some places thrust up more than 20,000 feet into the air. Not surprisingly, Peru and the other Andean countries possess great mineralogical wealth—and why wouldn’t they, with so much extra land mass? From the gold and silver of the conquistadors to the lead, copper, zinc, tin, bismuth and molybdenum of today, the mineral wealth of the Andes seems nearly inexhaustible.

The more global view that science has provided has also taught us other things. We now know, for example, that the Andes affect the continent’s entire climate—stopping the trade winds from reaching the Pacific Ocean and forcing humid air to instead dump their water onto the Andes’ eastern flanks. Three quarters of the silt that arrives at the mouth of the Amazon, as a consequence, consists of ground up bits of the Andes Mountains, moved there by a never ending torrent of the Amazon. In addition, because the Andes block the trade winds and because of the cold Humboldt Current sweeping up South America’s coast, Peru and Chile possess enormous stretches of bone-dry coast where it rarely, if ever, rains. Recently, scientists have also discovered that the Andes are a sort of species generator, much like the Galapagos Islands. Since each mountain peak possesses layer after superimposed layer of microhabitats, the mountains themselves resemble a kind of archipelago of islands, with the flora and fauna of each mountain sometimes getting cut off from the others. Thus, the Andes mountain chain acts as a sort of evolutionary pump, supercharging the planet’s biodiversity. Not surprisingly, a county like Peru has some of the highest biodiversity on the planet.

Today, however, the activities of the rest of the world have begun to impact life in even the remotest of Andean villages. And that is primarily because of the dramatic increase in the world’s population. When the first people stepped onto the South American continent, for example, only about four million human beings lived on Earth. Later, as the Ice Age began to retreat, the Earth’s population had increased to about fifteen million—about the present day population of the city of Los Angeles, California. Today, Homo sapiens has reached the extraordinary milestone of more than seven billion members and its population continues to grow. Meanwhile, more than a billion cars now ply the Earth’s highways, spewing out CO2 and contributing to the rise in the Earth’s temperature. Now, not only are glaciers melting throughout the Andes, but so are glaciers around the world, in addition to the rapidly accelerating melting of the twin polar ice caps—the last great thermo-regulators on Earth.

Five hundred years ago, beset by environmental problems they didn’t understand, the Incas made sacrifices to their gods. They did so in order to try and reestablish harmony to their world. Unlike the Incas, however, we have vastly more knowledge about the world than they did and have also created many of our most pressing environmental problems ourselves. And yet we often seem reluctant to do anything about them. If there is one thing we’ve learned, however, it is this: cultures that ignored their negative impacts upon their environments have often vanished, leaving only the ruins of their once magnificent civilizations behind. Will we follow in their footsteps—or will we strive to restore balance to the very planet that has given us life? It’s up to us to decide.

The post Global Warming and the Andes’ Shrinking Glaciers appeared first on Kim MacQuarrie Author and Filmmaker.

November 8, 2014

Machu Picchu Facts

Machu Picchu Facts

Machu Picchu Facts

Where it’s located: in the cloud forest of the Andes Mountains, in southeastern Peru, South America.

Who built it?: The Incan Emperor Pachacutec ordered its construction.

When was Machu Picchu built?: in the mid-15th century A.D.

When was Machu Picchu abandoned? Probably 100 years after its construction, most likely during the time of the Spanish conquest, sometime between 1533-1536.

Who discovered it and when? The American history professor, Hiram Bingham, in 1911.

How does it rank as a site to visit in S America?: It is the most visited archaeological site in South America, is Peru’s #1 tourist attraction and in 2007 was voted one of the new “Seven Wonders of the World.”

How many people visit per year? Nearly one million. The Peruvian government has recently limited visitors to 2,500 per day. Before that, sometimes twice that amount would visit during the high season (May through September).

Is it worth the visit? If you can only visit one place in South America and are interested in getting a sense of the Andes and of the largest indigenous empire ever to have existed on the continent—by all means, Machu Picchu is the one place to visit. Since you have to travel to Cusco to get there, you get double bang for your buck, as Cusco is one of the most interesting cities on the planet.

Machu Picchu Facts: Getting There

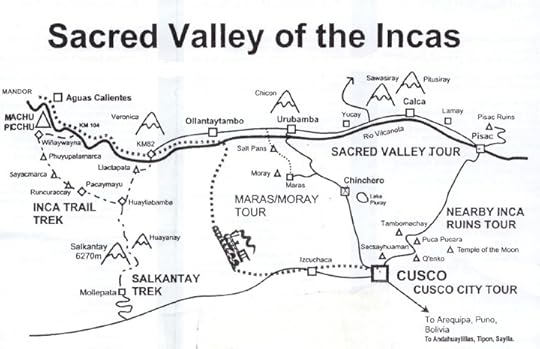

How to get there: Travelers can take international flights to Lima, Peru and from Lima can connect to Cusco by plane or by bus. From Cusco, the normal route is to take a 3.5 hour train ride to Aguas Calientes (now called Machu Picchu Pueblo), a small town located at the base of Machu Picchu Mountain. It is a half-hour bus ride from Aguas Calientes to the entrance of the ruins, although you will often have to form a long queue to secure a bus seat. You can also hike from the valley floor up to the ruins.

Visitor Tickets & Tips: Because of the number of visitors, visitors should buy their tickets at least five days in advance. You can make an on-line reservation and pay for the tickets here:

http://www.machupicchu.gob.pe/

(first, click on the upper left tab “reservas”; then, when you have your reservation number, click on the next tab that says “pagos.” Or, you can make your reservation online here and pay later in person in Cusco, although if you buy your tickets on-line you will avoid standing in lines):

Machu Picchu Facts: Here are the various locations you can do this in person:

Locations to buy Machu Picchu tickets

You have to enter Machu Picchu the same day that you bought your ticket for. If you bought a ticket to enter Machu Picchu on a certain Friday, for example, then you have to enter Machu Picchu on Friday.

Do I need a separate ticket to climb Huayna Picchu? Yes. You can buy a combination ticket.

Best seasons to visit: The dry season in this area of the Andes runs from April through October. Peak visiting season is in July-August, so if possible, try and avoid these months. Ideal months for visiting are April, May, September, or October.

How much time to allow: Allow at least a day. This is a spectacular site.

Can I visit Machu Picchu from Cusco in a day? Yes, but it will be a rushed experience. You can take the 3.5 hour train ride to Aguas Calientes in the morning, visit the ruins in the afternoon, then take the night train back to Cusco. But ideally, you’ll spend a couple of nights in Aguas Calientes so that you can have a full day to enjoy Machu Picchu.

Best time of day to visit: Early and late. The ruins open from 6:00 AM to 5:00 PM, 7 days a week and all year long. If you like, you can go up in the A.M. and then return in the P.M, for the same ticket price, avoiding the mid-day crowds. Tourist buses tend to depart an hour before closing, so the final hour at Machu Picchu is best.

Cusco, the Sacred Valley of the Incas, and Machu Picchu

Machu Picchu Facts: Where to stay

The nicest hotel in Aguas Calientes is the Inkaterra Machu Picchu Posada Hotel, although it’s pricey. After that, there’s a full array of lodging in Aguas Calientes, with a range of prices. You can also stay in the Belmond Sanctuary Lodge up on Machu Picchu mountain itself (it is the only hotel there); but this, too, is pricey.

http://www.inkaterra.com/inkaterra/inkaterra-machu-picchu-pueblo-hotel/

http://www.belmond.com/sanctuary-lodge-machu-picchu/

Is Aguas Calientes an interesting town? Not really. It’s a tourist town that sprang up because of the railway station and its proximity to Machu Picchu. It’s the ruins above that are the reason for the visit.

Machu Picchu Facts: How it was discovered

How did Hiram Bingham discover it? He was searching for a lost Inca city called Vilcabamba, after reading about it in old Spanish chronicles. To find it, he chased down every rumor of a “lost ruin” in the area. Two weeks into his trip, he stumbled upon Machu Picchu. (You can find out more about it in The Last Days of the Incas, which includes four chapters on Machu Picchu’s discovery).

When was Machu Picchu abandoned by the Incas? Probably soon after the arrival of the Spaniards (1533). This was a royal resort, and the Incas had more pressing things to do (combatting the Spaniards) than maintaining it.

Machu Picchu Facts: When was the earliest European visit? Spaniards who received lands in the area knew of its existence in the late 1500s. Local people probably always knew of its existence during the centuries after the Spanish Conquest. However, it wasn’t until Hiram Bingham visited the ruins in 1911 (and found three Peruvian farming families living there!) that he publicized its existence and Machu Picchu became known to the rest of the world.

Were the crates of Inca artifacts Hiram Bingham’s took from Peru ever returned? Yes, one hundred years later, in 2011! And only after the threat of a Peruvian lawsuit! (link)

Machu Picchu Facts: Famous Visitors

Famous visitors: Hiram Bingham, Che Guevara, Pablo Neruda, Mick Jagger, Cole Porter, Ron Howard, Bill Gates, Werner Herzog (while filming “Aguirre, Wrath of God” at Huayna Picchu), Charlton Heston (while filming the Hollywood film, “Secrets of the Incas” there), Jim Carrey, Susan Sarandon, Richard Gere, Shakira, Cameron Diaz, Leonardo di Caprio, etc.

Machu Picchu Facts: A Sacred Site?

Is it a sacred site? Yes, although in the Inca world the entire landscape was filled with sacred places—mountain tops, rivers, lakes, springs, glaciers, etc. Also, the citadel has a large number of temples, including a temple of the sun.

Was it a royal estate? Yes, it is thought to have been the royal estate of the Incan Emperor Pachacutec.

Why was it built on top of a mountain ridge in such a remote area? Because the emperor responsible for the building of Machu Picchu, Pachacutec Inca, had recently conquered the area. The citadel was built on top of a mountain ridge because mountains were sacred to the Incas and the citadel also had views of other sacred peaks.

How far is Machu Picchu from Cusco? About 75 miles.

What is the best route to get there?: One of the best routes to Machu Picchu includes spending a night in Ollantaytambo—the only Inca town that is still inhabited, and which has its own spectacular Inca ruins nearby. It is on the same train line between Cusco and Machu Picchu. If you can fit in a visit to Pisac, a little further up the Sacred Valley, that would be ideal. Pisac also has very good ruins.

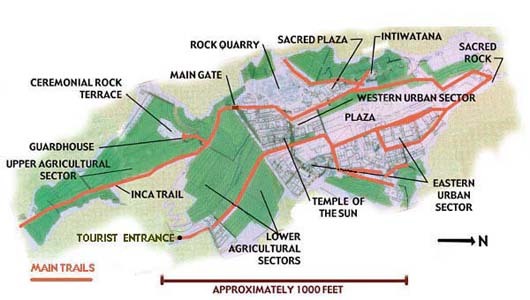

Map of the Machu Picchu ruins with main sectors

Machu Picchu Facts: Daily Life at the Time of the Incas

Who lived there? The Inca emperor, Pachacutec, when he was in retreat, plus his affiliated nobles, retainers, and administrators, plus peasants from around the empire who were there to tend the nearby crops, cut stone, bring in supplies, etc.

How many people lived there? Between 700 and 1,000, depending on whether the Inca Emperor was visiting.

How many houses are there? Around 140.

What kind of crops did they grow there? Corn, potatoes and an unidentified legume (bean).

Are there burials at Machu Picchu? Yes, about 200 of them. Human skeletons and associated pottery and other artifacts have been found in numerous cavities below rocks.

What was the average height of the men and women buried at Machu Picchu? Men: 5’2”; women: 4’11”

Machu Picchu Facts: Amazing Facts

Is there a tomb of gold there? Golden ornaments have been found. Recently, a French explorer claims to have found a hidden tomb, but no solid proof has been offered.

Machu Picchu Facts: Is it true that there was an astronomical observatory there? Yes. The Sun Temple was so constructed that precise measurements of the winter and summer solstices could be made—essential in a society that depended upon agriculture. Also, an astronomical observatory at Machu Picchu has recently been discovered:

http://archaeologynewsnetwork.blogspot.com/2013/09/astronomical-observatory-discovered-in.html

Machu Picchu Facts: Did the Inca road system connect to Machu Picchu? Yes, and part of it is now called “The Inca Trail.” The Incas built 26,000 miles of roadways throughout their empire.

How long did it take Chaski runners to carry a message to Cusco? About half a day. The Inca emperor could send a message to Cusco and receive a reply on the same day. It took Chaski runners about 3 days to carry a message from Cusco to the area that is now Lima, about 430 miles away.

Where did the stones of Machu Picchu come from? There is a rock quarry at the ruins.

Machu Picchu Facts: Who was Pachacutec, the Inca Emperor who Built Machu Picchu?

Read about Pachacutec and more Machu Picchu facts here

The Incan emperor Pachacutec

The post Machu Picchu Facts appeared first on Kim MacQuarrie Author and Filmmaker.

September 21, 2014

Atahualpa: The Inca Lord Who Lost an Empire

The Inca Emperor, Atahualpa

Atahualpa: Emperor of the Incas

Note: Atahualpa, lord of the Incas, was captured in Nov of 1532 by 168 Spaniards. Atahualpa was captured in the Inca town of Cajamarca, in what is now northern Peru. The following is an extract from The Last Days of the Incas:

“Most Inca accounts state that after [Atahualpa’s father] Huayna Capac‘s death, the latter’s son Huascar was crowned as emperor in Cusco, a thousand miles to the south. Another son, Atahualpa, remained in Quito, meanwhile, which Huayna Capac had made into an ancillary capital during his constant campaigns in what is now Ecuador. Born from different mothers, Atahualpa and Huascar were half-brothers.

Huascar, however, being the son of both Huayna Capac and of Huayna Capac’s principal wife, was a “legitimate” son, while Atahualpa, being the son of one of Huayna Capac’s many concubines, was by definition “illegitimate.” In the labyrinthine political intrigues that occurred during Inca successions, however, this did not necessarily rule out the possibility of Atahualpa ever coming to power. Both were in their mid-twenties at the time of their father’s death, yet had completely opposite temperaments. Atahualpa had been born in Cusco, had lived for many years in the far north with his father, had taken an avid interest in military pursuits, and was known for being extremely severe with anyone who differed with him. Huascar, on the other hand, had been born in a small village to the south of Cusco, had little interest in military affairs, drank to excess, commonly slept with married women, and was known to murder their husbands if they complained. If Atahualpa was the serious type, then Huascar was the party boy. Each, however, bore a sense of entitlement that made him ruthless if even the smallest portion of those entitlements was threatened.

Though Atahualpa and Huascar shared the same father, they belonged to completely different royal descent groups, or panaqas. Atahualpa belonged through his mother to the descent group known as the Hatun ayllu, while Huascar belonged through his mother to the group known as the Qhapaq ayllu. Both of these descent groups were competitive with one another, having struggled for supremacy and power now over several generations. And, as royal successions often provided the spark that unleashed open political warfare, from the moment that Atahualpa did not show up in Cusco for his father’s massive funeral and for his brother’s subsequent coronation, Huascar became suspicious. Huascar’s paranoia–derived no doubt from an Inca history that was richly embroidered with tales of brutal palace coups– became so acute that he is even said to have murdered some of his relatives who had accompanied his father’s corpse to Cusco, having suspected them of plotting an insurrection.

Huascar’s suspicions eventually got the better of him, suspicions that were presumably only accentuated by the inefficiency of the many messages and counter–messages that had to be carried between the two brothers over a thousand miles each way by relay runners. The newly crowned emperor finally decided to wage a military campaign in order to settle the question of succession once and for all. His decision to launch a war was not well thought out however, for it immediately put Huascar at a disadvantage.

Since Huascar’s father, Huayna Capac, had been carrying out extensive military campaigns in the north, his brother Atahualpa now had the advantage of being able to take command of the empire’s most seasoned and battle-hardened troops. The troops were led by the empire’s three finest generals, who immediately pledged their allegiance to Atahualpa. Huascar, by contrast, was forced to assemble an army of native conscripts who had little if any military experience. Where Huascar in the south led a largely untested army, Atahualpa commanded a seasoned imperial force. Nevertheless, Huascar quickly went on the offensive, sending an army north into what is now Ecuador, under the command of Atoq (“the Fox”).

The two Inca armies met on the plains of Mochacaxa, to the south of Quito. There the northern army, supervised by Atahualpa, scored the first victory in what was now a full-fledged civil war. Even in victory, however, Atahualpa’s severity with those who dared challenge him was evident when General Atoq was captured. Atoq was first tortured and eventually executed with darts and arrows. Atahualpa then ordered Atoq’s skull to be fashioned into a gilded drinking cup, which the Spaniards would note that Atahualpa was still using four years later.

With the momentum now on Atahualpa’s side, his generals began a long military advance down the spine of the Andes, gradually pushing Huascar’s forces further and further south. After a long series of victories on the part of Atahualpa’s forces and defeats on the part of Huascar’s, a final climactic engagement was fought outside Cusco during which the Inca emperor himself was captured, as described by the sixteenth-century chronicler Juan de Betanzos:

Huascar was badly wounded and his clothing was ripped to shreds.

Since the wounds were not life-threatening, [Atahualpa’s General] Chal-

cuchima did not allow him to be treated. When daylight came and it was

found that none of Huascar’s men had escaped, Chalcuchima’s troops

enjoyed Huascar’s loot. The tunic Huascar wore was removed and he

was dressed in another from one of his Indians who was dead on the

field. Huascar’s tunic, his gold halberd [axe] and helmet, also gold, with

the shield that had gold trappings, his feathers, and the war insignias he

had were sent to Atahualpa. This was done in Huascar’s presence, [as

Generals] Chalcuchima and Quisquis wanted Atahualpa to have the

honor, as their lord, of treading upon the things and ensigns of enemies

who had been subjected.

Atahualpa’s northern Inca army now marched triumphantly into Cusco. It was led by two of Atahualpa’s finest generals, Quisquis and Chalcuchima, who had successfully directed the four-year-long campaign. One can only imagine what the citizens of Cusco thought, seeing their former emperor stripped of his insignias and royal clothing, wearing the bloodstained clothing of a mere commoner, bound and led down the streets on foot, while Atahualpa’s generals rode majestically in their decorated litters, surrounded by their victorious troops.

The aftermath of the civil war to determine who would inherit the vast Inca Empire–and all the peasants and fertile lands within it-was as predictable as it was brutal. Within a short while, Inca troops rounded up Huascar’s various wives and children and took them to a place called Quicpai, outside Cusco. There the official in charge “ordered that each and everyone learn the charges against him or her. Each and every one was told why they were to die.” As Huascar’s captors forced him to watch, native soldiers methodically began to slaughter his wives and daughters, one by one, leaving them to hang. Soldiers then ripped unborn babies from their mothers’wombs, hanging them by their umbilical cords from their mothers’ legs.

The rest of the lords and ladies who were prisoners were tortured by a type

of torture they call chacnac [whipping], before they were killed,” wrote the

chronicler Betanzos. “After being tormented, they were killed by smashing

their heads to pieces with battle-axes they call chambi, which are used in

battle.

Thus, in one final orgy of bloodletting, Atahualpa’s generals exterminated nearly the entire germ seed of Huascar’s familial line. Huascar was then forced to begin a long journey northward on foot to face the wrath of his brother. The lengthy contest between who would inherit the vast Inca Empire had finally reached its bloody and climactic end.

The Inca Empire, circa 1532 A.D., at the time of Atahualpa

Atahualpa, meanwhile, had traveled southward from Quito to the city of Cajamarca, located in what is now northern Peru, some six hundred miles to the north of Cusco. There he waited for word of the outcome of his generals’ attack on the capital. Even via the Incas’ state-of-the-art messenger system, in which messages were carried by relay runners, or chaskis, news of the final battle and of Huascar’s dramatic capture had to pass between more than three hundred different runners. It would take at least five days to arrive. Only then would Atahualpa receive word that he was now the unchallenged lord of the Inca Empire, emperor of the known civilized world.

With all of his attention concentrated upon the steady, though delayed, stream of successful battle reports sent by his generals, Atahualpa was already busy making preparations for the coronation he envisioned in Cusco, the city of his youth. There, he would preside over the usual massive festivities-the processions, feastings, sacrifices, the debauched drinking and copious urinations-and finally, over the majestic coronation itself. Afterward–as his father, grandfather, and great-grandfather had done before him–Atahualpa would no doubt look forward to decades of uninterrupted rule, a monarch whose every action and pronouncement would be considered the divine acts of a god.

Atahualpa Learns of the Arrival of the Spaniards

There was only one minor affair, however, that Atahualpa had yet to attend to before he began his triumphal march southward to claim his empire. Chaski reports of a relatively small band of unusual foreigners, who were now marching into the Andes in his direction, had been reaching him for the last several months. Some of the strangers, he was told, rode giant animals the Incas had no word for as none had ever before been seen. The men grew hair on their faces and had sticks from which issued thunder and clouds of smoke. Although few in number-the royal quipu knots carried by the messengers indicated that there were precisely 168–the foreigners behaved arrogantly and had already tortured and killed some provincial chiefs.Rather than immediately order their extermination, however, Atahualpa decided to allow the strangers to penetrate a short way further into his empire. Protected by his army, Atahualpa was curious to see these strange men and their even stranger beasts for himself.

It was November 1532, the season in which the Andes begins its slow transition into the Southern Hemisphere’s summer. And, as news of the final victory in Cusco continued to race northward on foot along the often lonely and fantastic contours of the Andes, Atahualpa no doubt pondered for a moment this strange intrusion from the west. Who were these people? Why would they dare intrude into an empire where his armies could crush them if he so much as raised his little finger? As Atahualpa listened to the latest report about the bold yet obviously foolish invaders, intermixed with the much more interesting news arriving each day from the south, he lifted up the gilded skull of his former enemy, Atoq, the Fox, took a long cool drink from its rim of gold and bone, then turned his attention to the more pressing matters at hand.”

The post Atahualpa: The Inca Lord Who Lost an Empire appeared first on Kim MacQuarrie Author and Filmmaker.

September 11, 2014

Pachacutec: Incan Emperor Who Created Machu Picchu

Pachacutec: The Incan Emperor Who Built Machu Picchu

By Kim MacQuarrie

(Excerpt from the book, Machu Picchu: Song of Stone)

According to Inca oral history, in the early part of the 15th century an Inca king arose who would not only revolutionize the entire Andean world but who would also create some of the finest architectural monuments ever known. At the time, the Incas lived within a small kingdom centered around the valley of Cuzco, one of many such small kingdoms in the Andes and on the coast. The Incas told the Spaniards that, at the time, they were led by an old Inca king named Viracocha Inca. Faced with an approaching army from the powerful kingdom of the Chancas, the Inca ruler fled, leaving his adult son, Cusi Yupanqui, behind. The latter quickly took charge, raised an army, and somehow miraculously defeated the invaders. Cusi Yupanqui then deposed his father, arranged for his own coronation, and changed his name to Pachacutec, a Quechua word that means “earth-shaker” or “cataclysm,” or “he who turns the world upside down.” The name was a prescient one, for Pachacutec would soon turn the status quo of the Andes entirely upside down.

According to Inca history, Pachacutec had had a profound religious experience when he was young, a sort of epiphany that revealed to him both his divine nature and a vision of a nearly unbounded future. Wrote the Jesuit priest Bernabé Cobo:

It is said of this Inca [Pachacutec], that before he became king, he went

once to visit his father Viracocha, who was . . . five leagues from Cuzco,

and as he reached a spring called Susurpuquiu, he saw a crystal tablet fall

into it; within this tablet there appeared to him the figure of an Indian

dressed in this way: around his head he had a llauto like the headdress of

the Incas; three brightly shining rays, like those of the sun, sprang from

the top of his head; some snakes were coiled around his arms at the

shoulder joints . . . and there was a kind of snake that stretched from the

top to the bottom of his back. Upon seeing this image, Pachacutec became

so terrified that he started to flee, but the image spoke to him from inside

the spring, saying to him: “Come here, my child; have no fear, for I am

your father the Sun; I know that you will subjugate many nations and

take great care to honor me and remember me in your sacrifices”; and,

having said these words, the vision disappeared, but the crystal tablet re-

mained in the spring. The Inca Pachacutec took the tablet and kept it; it is said that

after this it served him as a mirror in which he saw anything he wanted,

and in memory of his vision, when he was king, he had a statue made of

the Sun, which was none other than the image he had seen in the crystal,

and he built a temple of the Sun called Qoricancha, with the magnifi-

cence and richness that it had at the time when the Spaniards came, be-

cause before it was a small and humble structure. Moreover, Pachacutec ordered

that solemn temples dedicated to the Sun be built throughout all the

lands that he subjugated under his empire, and he endowed them with

great incomes, ordering that all his subjects worship and revere the Sun.

Soon after becoming king, Pachacutec wasted no time in remaking the world according to his unique vision, beginning with the city of Cuzco. There, he undertook a major rebuilding campaign, reorganizing the layout of the capital, tearing down old buildings, creating new boulevards, and ordering a host of palaces and temples to be built. All of these were constructed in a new style of stonework that Pachacutec preferred–later referred to as the imperial style–stones cut and fitted together so perfectly that the skill and artistry displayed would eventually become famous as one of the wonders of the New World.

Trapezoidal doorway at Machu Picchu

Not satisfied with defeating the Chancas, however, the ambitious young king soon led his army into the nearby Yucay (Vilcanota) and Vilcabamba Valleys, conquering a number of ethnic groups. To celebrate these victories, Pachacutec ordered the construction of a number of royal estates: one in Pisac, another at Ollantaytambo, and a third that would eventually be known as Machu Picchu. The three estates were unusual, however, in that they were destined to be privately owned by the conqueror himself. It was a model that would soon be copied by succeeding Inca emperors and also by a small number of high-ranking Inca elites. Theirs would be the only privately held lands within the rapidly expanding Inca Empire.

Pachacutec created his new estates with a number of specific purposes in mind, perhaps the most important of which was to support his own family lineage. Each new Inca emperor was supposed to found his own panaca, or descent lineage, in essence becoming the patriarch and founder of a new family line. The crops and animal herds raised on Pachacutec’s private estates were thus slated to be used to support the members of his royal panaca. After his death, the estates would continue to be used and maintained by his descendants.

A second purpose for building the royal estates was to commemorate Pachacutec’s recent conquests: when complete, they would serve as monuments that would reflect the new emperor’s boldness, initiative, and power. Finally, the estates were also meant to serve as secluded royal retreats–luxury resorts located well away from the capital where the emperor and a select group of relatives and elites could rest, relax, and commune with the local mountain gods.

As with the new palaces and buildings he had ordered built in Cuzco, Pachacutec was first presumably shown models of his proposed estates in clay, complete with the projected buildings, agricultural terraces, and temples. Once Pachacuti had approved the designs, a legion of the kingdom’s finest architects, engineers, stonecutters, and masons went to work.

Pachacutec Creates Machu Picchu

To commemorate his conquest of the Vilcabamba Valley, Pachacutec ordered his third royal estate to be built on a high ridge overlooking what is now called the Urubamba River. The Incas apparently called the new site Picchu, meaning “peak.” Since the proposed citadel and nearby satellite communities were planned from the start to form part of a luxurious private estate, the entire complex would display some of the finest examples of Inca engineering and art.

The complex of what is now known as the ruins of Machu Picchu, in fact, was carefully planned and designed long before the first white granite block was ever cut and moved into place. The location, first of all, had to be both suitably sacred and spectacular; the site that Pachacuti selected was set high atop a ridge with an almost God-like view over the entire area and of the surrounding apus, or sacred peaks. It was essential that the site also contain a source of clean water-a substance sacred in itself-that could be used for drinking, bathing, and for ritual purposes. Picchu, in fact, possessed just such a crucial characteristic: on the large peak now known as Machu Picchu, and high above the proposed citadel, Inca engineers located a natural spring. They then designed a gravity-fed water system that would eventually carry water down from the peak to the ridge top site where it would ultimately pass through sixteen descending ritual fountains.

Portions of the ridge top were now carefully planed and flattened as workers created foundations of gravel, stones, and even subterranean retaining walls. Archaeologists who have excavated at Machu Picchu have reported that some 60 percent of the architectural engineering associated with the ruins actually lies beneath the ruins. Because of the heavy granite architecture and the region’s equally heavy rains, Inca engineers had to be certain that the locations chosen for building had solid foundations capable of withstanding both water and weight. Once the foundation was complete, construction finally began on the citadel itself, with workers cutting stone mainly from a quarry located on the same ridge top, using a variety of stone and bronze tools. Only once the first stone blocks had been cut did construction begin on the buildings, palaces, and temples of Machu Picchu.

Workers and specialists from around the country now convened on the remote site, all of them supervised by a bevy of architects and engineers. In order to equip the citadel with the latest, state-of-the-art technology, Inca astronomers worked alongside the engineers and stonemasons to fashion observatories that could accurately mark the summer and winter solstices as well as other astronomical events. Workers fulfilling their mit’a labor tax, meanwhile, busied themselves constructing roads to and from the royal estate, linking Machu Picchu with the capital, Cuzco, and with other newly built centers, such as Ollantaytambo, Pisac, and, eventually, Vitcos and Vilcabamba. Additional laborers were also put to work constructing large agricultural terraces in order to help provide food for the citadel’s future inhabitants as well as for ritual sacrifices. Soon, Inca labor and technology had transformed the steep, jungle-covered slopes into a staggered series of flat terraces that eventually produced fourteen acres of sacred corn.

When Machu Picchu was finally ready for use sometime in the 1450s or 1460s, the first ruler of the newly created Inca Empire, Pachacutec, no doubt arrived there on his royal litter, accompanied by royal guests, a large retinue of servants, and at least part of his harem. The citadel’s furnishings, plumbing, food, supplies, servants, and cooks had all been carefully prepared so that the emperor would be able to relax along with his guests. Then, as now, clouds wreathed the surrounding peaks, alternately exposing and obscuring them. Unlike the ruins today, however, the gabled roofs of the buildings were covered with fresh yellow ichu thatch while the stones of the citadel were white and freshly cut and glistened in the sun.

Temple Complex at Machu Picchu

Similar to the recent architecture in Cuzco, much of the stonework at Machu Picchu had been cut in the imperial style that Pachacutec preferred; some of the buildings, in fact, were constructed with boulders the size of small cars, each cut, fitted perfectly into place, and weighing up to fourteen tons. The water from the nearby peak of Machu Picchu, meanwhile, descended into the citadel through a stone-lined aqueduct and arrived first at Pachacutec’s living quarters, thus allowing the emperor to come into contact with only the purest water available. A stone-cut pool in Pachacutec’s dwelling allowed the emperor to bathe in complete privacy while the emperor’s residence also had the only water-flushed lavatory at Machu Picchu.

As Pachacutec bathed himself in his private bath, the voices of his guests would have floated across the plaza outside along with the distant sounds of metalworkers tending their forges and hammering out gold and silver ornaments, utensils, and jewelry. Strings of llama trains constantly arrived, looking from a condor’s perspective like lengths of knotted quipu cords; the food and supplies they carried up from the jungle and down from the Andes was carefully unpacked at a station just outside the citadel. Even at this private retreat, chaski runners appeared periodically with messages for the emperor and other officials, who in turn sent their commands back to Cuzco and to other parts of the empire. Wherever the emperor went, in fact, his royal court followed. Thus, whenever Pachacutec was in retreat at Machu Picchu, this lofty, isolated citadel temporarily became the power center and locus of the entire Inca world.

Machu Picchu During the Time of Pachacutec: A Royal Estate

Unlike the ruins of Machu Picchu today–which are owned by the Peruvian state and are open to the public, and where tour buses disgorge hundreds of thousands of visitors each year–Machu Picchu in the time of Pachacutec was an exclusive and private affair. The roads here–like the roads elsewhere in the empire–were open only to those individuals traveling on state business. Other than Pachacutec’s immediate family, the workers who kept the citadel functioning, and the invited elites who traveled here on canopied litters, often decorated with precious metals and iridescent bird feathers, Machu Picchu was unknown to the rest of the empire’s inhabitants. Machu Picchu, quite simply, was Pachacutec’s Camp David–a royal resort built by a man who had almost single-handedly transformed a small native kingdom into the largest empire the New World has ever known.

The citadel of Machu Picchu was thus the third and perhaps most important jewel in the crown of architectural monuments that Pachacuti had created, after Pisac and Ollantaytambo. Balmy and warm, the site was no doubt a welcome respite from the often freezing winter weather of the Inca capital and from the high Andes in general. Even after Pachacutec’s death and long after the emperor had been ritually embalmed and mummified, Pachacutec’s servants no doubt continued bringing their divine emperor to visit Machu Picchu and to visit the other estates he had carved out of the Andes, his sightless eyes seeming to gaze off into the distance as the members of his royal panaca continued to enjoy the fruits of their founder’s unparalleled conquests and labors.

The ruins of Pachacutec’s royal retreat of Machu Picchu

The post Pachacutec: Incan Emperor Who Created Machu Picchu appeared first on Kim MacQuarrie Author and Filmmaker.