R.P. Nettelhorst's Blog, page 123

March 3, 2013

Life

Sometimes it is hard to get up in the morning. And sometimes it’s hard to go to sleep at night. It’s easy to identify with the words of Deuteronomy 28:66-67:

You will live in constant suspense, filled with dread both night and day, never sure of your life. In the morning you will say, “If only it were evening!” and in the evening, “If only it were morning!”—because of the terror that will fill your hearts and the sights that your eyes will see.

I especially could identify with that when our foster son died of SIDS 15 years ago and we were sued for 31 million dollars for wrongful death. It was hard to sleep and it was hard to get up. It was hard to do anything at all, in fact.

That’s what the problems in our lives can do to us: they paralyze us and make it hard to function. We know we should read our Bibles, we know we should pray, but when we do either thing, it feels empty. We don’t know what to say to God and we don’t feel much like talking, any more than we feel like getting up out of our chair. Those things that once brought us pleasure, that once made us excited, now seem empty and do nothing for us at all. When we read the Bible—or anything else for that matter—we can read the same paragraph over and over again and get nothing from it. Watching TV or a movie is an empty experience; we may find it hard to even remember what we just saw on the screen.

Jesus told an audience, “Therefore I tell you, do not worry about your life, what you will eat or drink; or about your body, what you will wear. Is not life more important than food, and the body more important than clothes?” (Matthew 6:25)

Jesus told his disciples, not long before he was arrested, convicted, and executed, “Peace I leave with you; my peace I give you. I do not give to you as the world gives. Do not let your hearts be troubled and do not be afraid.” (John 14:27) Sometimes people give us encouragement in the middle of our bad times and we think “easy for you to say.” But given Jesus’ context, knowing what he was about to face, his words carry added force. They were not easy, they were not cliché, and they were not flippant. He believed them even though he faced the ultimate crisis.

March 2, 2013

An Excerpt

John of the Apocalypse

An excerpt from my novel, John of the Apocalypse , available as an e-book for the Kindle:* * *

“So what was that last thing you heard Jesus say?” demanded Albertus. “I wish you’d stick with Greek, you know; or have you noticed? You’re the only Jew here.”

John frowned. “Yeah, I’ve noticed.” He paused. It means, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”

Lydia’s eyes brightened. “Oh, I’ve heard that before; why would he have said such a thing?”

“I heard someone tell me it signified that when God put all the sins of the world on Jesus, that God turned his back on him, that for the first time ever, Jesus was separated from his Father…” began Eusebius.

John laughed, a bitter, derisive sort of laugh. “What a load of B.S,” he commented, then frowned, when he noticed the shocked look that Lydia gave him. As if she had never heard such language before. Of course, she wasn’t a fisherman, was she?

“Excuse me…” she began.

“He’d been betrayed by one of his closest friends, and all the rest of them had run away. He had been beaten nearly to death with a whip, he’d had a crown made out of thorns pushed onto his scalp, he’d been kicked, he’d had his beard and hair plucked out by the roots, he’d been spit on and mocked and then finally nailed naked to a cross and left to die a slow and miserable death. What the hell would you have expected him to say, huh? ‘Oh praise you God, for this great and marvelous blessing?!’”

“Well, he is God’s Son, you know…” began Lydia.

“He was a man!” shouted John, loudly. “Don’t you freaking get it? Jesus was a human being, just like you, just like your husband, just like me.” He could feel his nostrils flaring, his heart was thumping; he wanted to get control of himself again, but the words just kept coming. “How did you respond when you were beaten? You were ready to sacrifice to the great god Domitian, weren’t you?”

Eusebius swallowed.

“But he was God…” began Lydia.

“Tell me Eusebius, did you think that Domitian was divine?”

He shook his head.

“Did you have any doubt about who Jesus was? Had you begun to question the rightness of your cause, the certainty of eternal life?”

Eusebius shook his head.

“But you were still going to pour wine on Caesar’s altar.”

He nodded, bowed his head, started to shake.

“But he was God!” insisted Lydia.

“He was a man; and he died like men die when they’re on a cross, when they’ve been beaten: he was in agony, he was worn out, and he was alone. Everyone had abandoned him, and now he was just dying there, and nothing was happening, and life was going on without him, and tomorrow he was going to be dead, but everyone else would still be there. The sky was dark, no dove descended from the sky, no words shook the earth announcing that “this is my Son, in whom I’m well pleased.” He was stuck on that Roman cross, and three women and one friend stood there helplessly and watched him die and there wasn’t a thing any of us could do to help him, to make him feel better, to make the pain go away.” John sobbed. “And so he just died, alone, abandoned, and hopelessly.”

“But he was God.”

“He died by himself, killed by the enemies of God. What the hell else was he going to say, huh?”

“But how could Jesus feel despair?” asked Lydia.

“How could he not?” asked John. “He was a human being; he had the same feelings, the same hopes, the same needs that all the rest of us have. Sure he was God, is God—since he lives again—but he was human, and that meant all the things it means for us to be human. He never screwed up like the rest of us, but otherwise, he felt what we feel: he was sad, he was happy, he was angry, he was scared, he felt lonely and he felt despair.” John shook his head. “Why are you Greeks so loathe to admit that there’s nothing wrong with being made of flesh?” He picked up his cup, looked at it, rubbed his fingers on the smooth sides of the ceramic bowl. “God created us to be like we are: to sweat, to get tired, to make love, to touch and feel, to laugh and cry. This cup contains wine, and the wine makes me feel good; I like the taste, I savor the experience, I wallow in it; I live my life fully, and rejoice in what I feel, what I taste, what I see, what I touch. The world around us is full of pleasures, of satisfactions, of enjoyment, and it is there to be enjoyed.”

“How Epicurean…” commented Lydia.

John ignored her, went on. “There is no virtue in denying your senses, in pretending that you don’t feel; no virtue attaches to you from seeking discomfort instead of pleasure. You are not any closer to God, you are not any more spiritual when you refrain from anything that might be fun. Why is the sun warm, the air filled with the smell of sweet flowers, the grass green, the water wet? Why is there wine, and bread and fruit? Do you cringe from pain? Why does the noxious, the painful, the ugly and the uncomfortable make you flinch away? Why are you attracted to the pleasant, the sweet, the warm, the loving, the happy? Jesus was human like that. He loved life; he felt life. He experienced the full range of emotions.” John paused. “And you know what? We human beings were created in God’s image; we’re just like him, the lot of us. So feeling, being alive—these were not new experiences to Jesus; God knew those feelings; God has those feelings. Feelings—they’re not an evil thing. They simply are, like the blue in the sky, or the wet in water. You seem bothered by Jesus’ cry of despair when he died.” John paused, shrugged his shoulders. “I’d be bothered only if he hadn’t.”

March 1, 2013

More About Economics

Banking and investments seem impossibly mysterious to many people who have trouble just getting their checkbook to balance.

Let’s begin by looking at what’s called the “money supply.” The money supply is the total amount of money available to the economy at any particular moment. What is money? It’s more than just the metal slugs and slips of green paper in your pocket. Money is simply anything that can be used to settle a debt.

How is the money supply measured? There are four ways of measuring it, referred to as the M0, M1, M2 and M3. M0 money is physical currency: the coins and green paper you carry around–that is, the money in actual circulation–and the cash assets held in a central bank.

M1 money includes the stuff of M0 with the addition of money in “demand accounts”–that is, checking accounts. M1 is the measure that economists use to quantify the amount of money that is in actual circulation.

M2 is made up of everything in M1, with the addition of time deposits (those things like Certificates of Deposit that you can’t access for a specific period of time), savings deposits, and non-institutional money-market funds. Economists use M2 when they are trying to predict inflation.

M3 is made up of everything in M2 and includes large time deposits, institutional money-market funds, short-term repurchase agreements, and other larger liquid assets. It is used by economists when they want to measure the entire supply of money within an economy.

These different sorts of money that exist in the money supply statistics arise from the practice known as fractional-reserve banking.

What’s that?

When a bank gives out a loan, money is actually created by the bank. If you deposit a hundred dollars into the bank, they lend it out ten times with a fractional-reserve rate of twenty percent. This means that of the initial one hundred dollars, twenty percent of it, or twenty bucks, is set aside and kept in the vault, while the remaining eighty percent, or eighty bucks, is loaned out. The recipient of the eighty dollars then spends that money. The receiver of that eighty dollars then deposits it into a bank. The bank then sets aside twenty percent of that eighty dollars, or sixteen dollars, as reserves and lends out the remaining sixty-four dollars. As the process continues, more commercial bank money is created, since the bank only is keeping as a reserve twenty percent of any of the money given to it. The rest it loans out. That’s how the bank makes money on the money you put into it. Otherwise, the bank would have to charge you for holding on to your money. This creation of money by this means inflates the money supply. If the economy grows to match the increase in this money supply, then wages and prices remain stable. If things get out of balance, then you get “inflation.”

The banks lend the money at an interest rate based on how much it costs them to get the money they are lending out, and based on the amount of risk they are taking in making the loan: if banks and other lenders are careful, then they will receive back more money than they lent out, thus making a profit and allowing them to continue lending money. If they are not careful, then they can wind up in a situation where they do not have enough funds to lend any more money, or worse, cannot repay those who have deposited money into the bank.

If you recall the movie A Wonderful Life, when the depression hits and people panic, creating a “run” on the bank, George Baily calms the situation by pointing out that the money the people in his town have put in his Savings and Loan is not in the vault–it’s been lent out to their friends and neighbors: “it’s in Joe’s house.”

This fractional-reserve banking works because over any typical period of time, demands by people to take the money out of the bank–redemption demands– are for the most part offset by new deposits or issues of notes. The bank thus needs only to satisfy the excess amount of redemptions. Second, only a minority of people will actually choose to withdraw their demand deposits or present their notes for payment at any given time. Third, most people keep their funds in the bank for a prolonged period of time. And finally, banks usually keep enough cash reserves in the bank to handle all the demands for cash.

If the demands for cash are unusually large, however, the bank will run low on reserves and will be forced to raise new funds from additional borrowings (that is, by borrowing from the money market or by using lines of credit held with other banks), and/or sell assets, to avoid running out of reserves and defaulting on its obligations. If creditors are afraid that the bank is running out of cash, they have an incentive to redeem their deposits as soon as possible, triggering a bank run.

Bank runs are very unusual today, largely because of the systems set in place following the Great Depression, such as deposit insurance and the current requirements now of how much of a reserve banks must keep. The interest rates that we pay or get for our deposits are determined to a large extent by how much banks charge other banks for the money they lend to each other. The government sets the interest rate that banks charge one another. The decision on what rate to charge is based on how well the economy as a whole is doing. If it isn’t doing well, or if there is a fear that it won’t, the rate will be lowered: that will put more money into circulation. If there is a fear that inflation may be in the works, the interest rate will be raised, thus lessoning the money supply.

How does the stock market work into all of this? It is simply a public market for the buying and selling of securities–that is a percentage shares–in businesses. It is a way for businesses to raise money that they can then use to expand; if the business is successful, they will make a profit, which will allow them to pay back all the people who purchased a percentage of the company, or if people keep the stock, then those share holders will receive a percentage of the profit as a dividend payment. People may buy and sell shares of the company at any time, however, and the price of a company’s shares will rise or fall based on how well the company is doing, or how well people imagine it is doing.

February 28, 2013

Free Return Trip to Mars

Since they are looking for a married couple to do this, I talked to my wife about it and she’s agreeable. Just have to see where you go about signing up. We get along well–we’ve been married nearly 30 years now–so from the compatibility standpoint it would work. And by 2018 all our children will be adults.

Source SPACE.com: All about our solar system, outer space and exploration

February 27, 2013

Perspective

The heavens declare the glory of God;

the skies proclaim the work of his hands.

– Psalm 19:1

The Earth is 7927 miles in diameter.

The Moon is 2163 miles in diameter, and averages 238,857 miles away from the Earth. This is the equivalent of 1.3 light seconds away. Light travels 186,300 miles per second.

The Sun is 864,000 miles in diameter, more than large enough for the Earth-Moon system to slip inside with room to spare. The Earth is an average of 93 million miles away. This is the equivalent of 8.3 light minutes away — the distance light can travel in 8.3 minutes.

Pluto, the furthest planet from the sun, averages 3.67 billion miles from the Sun. This is the equivalent of 5.5 light hours away.

More than 99 percent of the mass of the solar system is in the Sun, whose mass is 4.385 times 10 to the 30th pounds (4,385,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000). This is 333,000 times the mass of the Earth.

The Sun is made of mostly hydrogen gas which is heated by continuous nuclear fusion at the core, where the temperatures are near 27 million degrees Fahrenheit. The visible surface of the Sun has an average temperature of 9950 degrees Fahrenheit and continuously radiates power of 3.85 times 10 to the 26th watts (38,500,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000) into space. The Earth intercepts less than half of one-billionth of that power.

The Sun is a fairly typical star; most stars range from one tenth to ten times the size of our Sun. Antares, the reddish star in the constellation of Scorpius is five hundred times the size of our Sun. Our Sun and all the planets to the orbit of Mars could easily fit inside it. Antares is 400 light years from Earth.

A light year is the distance that light can travel in one year — about 5.88 trillion miles.

Alpha Centauri is the nearest star to Earth. It is 4.3 light years away — 25,000,000,000,000 miles away. The fastest men have ever traveled in space was 25,000 miles per hour (escaping Earth’s gravity on their way to the moon — which took them three days to reach). It would take 115,340 years to travel to Alpha Centauri at that speed.

Let’s look at these distances another way. Suppose you could drive your car to the Sun, 93 million miles away. At sixty miles an hour it would take you almost one hundred seventy-seven years to get there. Now imagine how long it would take you to get to Alpha Centauri in your car.

In their book, The Planetary System by Morrison and Owen, they write (pages 24-25):

To gain an appreciation of the size of the solar system and the distances between the various planets, we can make use of a scale model. Let’s reduce every dimension in the solar system by a factor of 200 million. On this scale, the Earth is the size of an orange, and our Moon would be a grape, orbiting the orange at a distance of six feet. The Sun would be a little less than half a mile away, and it would have a diameter of twenty-three feet, the height of a two-story building. It is the great distance of the Sun from the Earth that makes it appear to be about the same size as the Moon when we see both of them in our skies.

Although the Earth and the other inner planets in this model are only the size of pieces of fruit, we do have some bigger planets. At this scale, Jupiter would be a large pumpkin, still small compared to the Sun but eleven times larger than Earth. Considering the Saturn system, we find that if we measure it from one edge of the rings to the other, the planet and its rings would just fit between the Earth and the Moon. Saturn’s own large satellites would lie far beyond the moon. Obviously scales in the outer solar system are considerably grander than those we find for the planets closer to the sun.

Moving further out, we pass Uranus and Neptune before encountering Pluto, another grape like our Moon at an average distance of 18.5 miles from the twenty-three foot Sun. This is still not the edge of the solar system, however. That lies at a point where the gravitational field of the Sun is changed by the fields of passing stars. Here is where the great spherical cloud of comets lies, at a distance of some 20,000 miles from our scale model Sun. This means that our scale model solar system is about four times the size of the real Earth.

This exercise illustrates how large the Sun is, how much space exists between the planets, even in the inner solar system, and to what an enormous distance the Sun’s gravitational influence extends. The latter simply emphasizes once again how huge the distances are between the stars. The nearest star, Alpha Centauri, is five times as far from the Sun as the comets; to include it, our model would have to extend to a dimension of 100,000 miles.

Our Sun is a star in the Milky Way Galaxy, a pinwheel-shaped glob of stars 100,000 light years across and 10,000 light years thick. The Sun is 30,000 light years from the center of this galaxy. It takes 230 million years for the Milky Way to revolve once on its axis. Our Milky Way Galaxy contains at least 100 billion stars (some estimates put it at 400 billion).

The nearest other galaxy (excluding the Magellanic Clouds about 150,000 light years away) is the Andromeda Nebula which is about two million light years away from Earth (the average distance between all the galaxies in the universe) and it is 200,000 light years in diameter — twice as big as the Milky Way.

The observable universe is 30 billion light years in diameter and contains approximately 100 billion galaxies (each of which then has at least 100 billion stars, often more). Yet, the observable universe (all 30 billion light years of it) is perhaps only a fraction of one percent of the size of the universe as a whole.

When I consider your heavens,

the work of your fingers,

the moon and the stars,

which you have set in place,

what is mankind that you are mindful of them,

human beings that you care for them? –Psalm 8:3-4

February 26, 2013

Turning Point

Today we remember September 11 for what happened in 2001. But it is a memorable day for another event as well: one of the turning points of history.

Between 1667 and 1698, Europe battled the Ottoman Empire, an empire that endured from 1299 until 1923. From the 1500s through the 1600s the Empire was at the height of its powers and controlled most of Southeastern Europe, Western Asia and North Africa: the modern nations of Egypt, Libya, Turkey, Greece, Hungary, Syria, Lebanon Israel, Iraq, Iran, parts of Saudi Arabia (including the Moslem holy cities of Mecca and Medina) were all part of the Ottoman Empire by 1683. During this period of ascendency and power, the Ottomans under the Sultan Mehmed IV had their eyes on the conquest of Europe and were pressing toward the city of Vienna in modern Austria.

They repaired and built roads and bridges leading into Austria and moved large quantities of ammunition to staging areas leading to Vienna. Finally, on January 21, 1682 the Ottoman army itself mobilized. Then on August 6, the Ottoman’s declared war. Months passed before the Ottomans began their full scale invasion, however. This allowed the Habsburg forces in Austria time to prepare defenses and to assemble alliances with other Central European rulers. The most significant of those alliances was with Poland. The Habsburgs made a treaty promising to support the Polish king Jan III Sobieski if the Ottomans attacked the Polish city of Krakow, and Sobieski promised to send his army if Vienna were attacked.

The Ottoman siege of Vienna finally began on July 14. At the very beginning, the Ottoman’s demanded surrender. There were only 11,000 troops and 5000 citizens in Vienna at that time. But they refused to surrender to the Ottomans. The leader of the troops, Ernst Rudiger Graf von Starhemberg, had just received news that the nearby town of Perchtoldsdorf had agreed to such a surrender. Upon their surrender, the Ottomans had slaughtered all its citizens.

Thus, the Viennese decided it was better to die fighting than to die after surrendering. Though the Ottomans had a larger army with very good cannons, the fortifications of Vienna were very strong. The Ottomans attempted to breach the city walls by digging tunnels underneath them and filling the tunnels with gunpowder. Meanwhile, the Ottomans cut off the food supply into Vienna.

By the time the first forces arrived in August, 1683 to aid in the defense of Vienna, the defenders in the city were in desperate straits of hunger and fatigue. On September 6, the Polish army finally arrived, led by Jan III Sobieski. Soon additional forces from Saxony, Bavaria, Baden, Franconia and Swabia arrived.

Meanwhile, the Ottomans repeatedly blew up large sections of the defending walls of the city. But despite the large gaps in the city walls, the Ottomans were unable to get inside the city. The various armies that had come to defend Vienna finally joined together under the command of the Polish king Jan III Sobieski and on September 11-12, 1683 they succeeded in utterly defeating the Ottoman army and driving it back from Vienna.

By the time they were victorious, there were 84,000 troops defending Vienna. They had faced a much larger Ottoman force of between 150,000 and 300,000 troops. The Ottomans lost at least 15,000 men dead or wounded, plus another 5000 captured compared to the loss of about 4500 of the defending troops killed or wounded over the day long battle.

The Ottomans abandoned enormous amounts of material: cannons, tents and cattle. Following the victory, the commander of the troops that had been besieged in Vienna, Ernst Rudiger Graf von Starhemberg, hugged and kissed the king of Poland and called him “my savior.”

This one battle determined the ultimate course of the entire war and meant that Europe would not be overrun by the Ottomans. Although the Ottomans continued fighting against the Europeans for another 16 years, the battle marked the end of the expansion of the Ottoman Empire into Europe. In fact, the Ottoman Empire began losing territory. By the time the conflict ended in 1699 with the Treaty of Karlowitz, the Ottoman Empire had lost much of their territory in Europe, including Hungary and Transylvania.

By the time World War I began in 1914, the Ottoman Empire was a shadow of its former self and was generally referred to as the “sick man” of Europe. It made the mistake of joining Germany in that conflict. When Germany lost World War I, the Ottoman Empire lost as well and its land holdings in Africa and Asia were divided up up among the victorious forces: England took control of Egypt, Palestine and Iraq, leaving the Ottomans with only Turkey. England had promised to establish a Jewish state in part of Palestine with the Balfour Declaration of 1917, which was then incorporated into the peace treaty that the allied forces made with the Ottoman Empire after World War I ended. France took control of Syria and Lebanon. Greece became an independent nation nominally aligned with the Ottoman Empire, though even before the peace treaty was signed, the Ottoman Empire was rife with conflict and revolution.

By 1923 the forces of change enveloped the pitiful remains of the once mighty Ottoman Empire. The last Sultan was overthrown and a secular government was established by Mustafa Kemal, forming the Republic of Turkey, which today is a modern, secular, unitary, constitutional republic. In 2005 it began full membership negotiations with the European Union, having been an associate member of the European Economic Community since 1963. It is also a member of NATO.

February 25, 2013

Economics

Most people never take a course in economics, nor do they ever start their own business. Unsurprisingly then, most people don’t understand how businesses works. The rising cost of gasoline or other commodities is a puzzle that they are tempted to explain by some sort of wicked conspiracy. Unfortunately, many of these people wind up in elected office.

This lack of basic economic understanding is well illustrated in the behavior of public entities such as municipal bus companies or the post office. Each year, the cost of riding the bus or mailing a letter rises. The reason this happens is because the bureaucrats in charge of these entities notice that the amount of money their company has made has declined. They then look at how many letters have been carried or bus riders moved, and divide that by the amount of money they need to get in order to break even. They then raise the rate of postage or bus tickets accordingly. The following year they are shocked when they once again fail to bring in enough money to balance their budget and they go through the same exercise again.

Oddly, the concept of supply and demand, a very basic part of economic theory, seems to have escaped them. As prices rise, the number of people who will purchase a product or service will decline. Thus, by raising the cost of their product, the post office makes ever more people decide to forgo using stamps. This is especially true when there are alternatives to the product being offered. So, people use email which is free, and online bill paying, which is also free, thus bypassing the post office altogether. Likewise, those who might otherwise ride the bus choose to walk, use a bicycle, or hitch a ride with a friend who has a car. Commuters look at the cost of a bus pass and compare that with the cost of carpooling and choose to carpool instead.

Certainly, I could open a restaurant and try selling hotdogs with a bag of chips and a soft drink for five thousand dollars each. Chances are, I would never sell a single meal. Why? Because hungry people would go to the restaurant next door and pay three dollars and fifty cents for the same thing. Why pay five thousand when you can get it for so much less? This is how supply and demand works in the midst of free competition. People seem shocked that businesses are “greedy.” As if they exist for some other reason than making money. Ask yourself a simple question. Why do you go to work every day? No matter how inspiring or satisfying or fulfilling your job might be, the reason you get up in the morning is because of your paycheck, you greedy thing you. Of course business tries to make money. That’s how it works. But businesses, just like individuals, are constrained by the competition from other businesses, both those that exist, and the threat of those that might arise. They are constrained by their expenses and by supply and demand.

So why is gasoline so expensive? Same reason. There is only so much gasoline available as compared to those who want it. In the last few years demand has grown enormously, thanks to the burgeoning economies of India and China. Where before, most oil products were purchased only by the Americas and Europe, now the people of India and China are becoming prosperous and need fuel for all their new automobiles, not to mention all their new factories and power plants. This added demand means that the Americas and Europe must compete with fresh customers for the same amount of commodities. Production of oil and gasoline has not risen significantly since no new refineries have been built and no new drilling is going on. The only way to lower the cost of gasoline is by either increasing the supply, or by decreasing the demand. Unfortunately, our political establishment has a tendency to interfere in this process, prohibiting or restricting sources of supply.

Why do gas stations raise their prices overnight? Because the gasoline they sell today pays for the gas they need to buy tomorrow to replace it. When a hurricane hits one of the primary refinery regions in the US, those markets in the US that get their gasoline from there will have to pay more the very next day to replenish the supply of gasoline that they sold today. Just because they paid 3.50 a gallon yesterday from their supplier won’t help them when they need to pay 4.50 tomorrow. So while the gas they are pumping into your tank today only cost them 3.50, and yesterday they charged you 3.53 for it, they’re still going to have to charge you 4.53 today so they can buy that 4.50 gasoline tomorrow. It’s not price gouging, it’s just basic supply and demand. If they charge you only 3.53 today, they won’t be able to sell you ANY gasoline tomorrow.

The capitalist system of economics is not perfect and the businesses and individuals who are a part of it (that’s everyone of us on the planet now, thanks to the collapse of communism– and the Chinese are capitalists now, despite the fact that they might call themselves something else–and it’s their capitalism that has made their economy boom) are not saints. But it has, nevertheless, worked better than any competing theory that has ever been developed.

And politicians in general have little to do with how the economy is doing (except for those things they actually run, like the post office and municipal bus lines, or the often unintended consequences of the regulations and taxes they might impose that can make it difficult for companies to make a profit or even get started in the first place), despite the tendency for so many to try to blame them for it. The economy runs in cycles, rising and falling as naturally as waves on the ocean. That can be very painful for some individuals during down times, but the down times are just as temporary as the up times. And the rising and falling of the economy, in general, is about as easy as trying to control the waves of the sea. And generally speaking, the more politicians try to fix things, despite how well-intentioned they are, the worse they are likely make the situation. Just look at the post office and the bus companies.

February 24, 2013

It’s Good to Know What You’re Talking About

“Usually, even a non-Christian knows something about the earth, the heavens, and the other elements of the world, about the motion and orbit of the stars and even their size and relative positions, about the predictable eclipses of the sun and moon, the cycles of the years and the seasons, about the kinds of animals, shrubs, stones, and so forth, and this knowledge he holds to as being certain from reason and experience. Now, it is a disgraceful and dangerous thing for an infidel to hear a Christian, presumably giving the meaning of Holy Scripture, talking nonsense on these topics; and we should take all means to prevent such an embarrassing situation, in which people show up vast ignorance in a Christian and laugh it to scorn. The shame is not so much that an ignorant individual is derided, but that people outside the household of faith think our sacred writers held such opinions, and, to the great loss of those for whose salvation we toil, the writers of our Scripture are criticized and rejected as unlearned men. If they find a Christian mistaken in a field which they themselves know well and hear him maintaining his foolish opinions about our books, how are they going to believe those books in matters concerning the resurrection of the dead, the hope of eternal life, and the kingdom of heaven, when they think their pages are full of falsehoods on facts which they themselves have learnt from experience and the light of reason? Reckless and incompetent expounders of Holy Scripture bring untold trouble and sorrow on their wiser brethren when they are caught in one of their mischievous false opinions and are taken to task by those who are not bound by the authority of our sacred books. For then, to defend their utterly foolish and obviously untrue statements, they will try to call upon Holy Scripture for proof and even recite from memory many passages which they think support their position, although they understand neither what they say nor the things about which they make assertion [quoting 1 Tim 1:7].

–St. Augustine, “De Genesi ad litteram libri duodecim” (The Literal Meaning of Genesis)

February 23, 2013

Scolds

H. L. Mencken once characterized Puritans as people possessed by the “haunting fear that someone, somewhere might be happy.” Puritans come in all sorts of political and religious flavors. They are not just people who dress in black and thunder about misdeeds on Sunday mornings. They can be Hollywood types and even singers. Such as Sheryl Crow.

A few years ago, according to the Washington Post, Sheryl Crow wanted to regulate how many squares of toilet paper might be used at any one sitting in order to save trees and reduce pollution. She suggested one square is enough—at least most of the time—with a maximum of three in exceptional situations. She also thought tissues were horribly wasteful. She believed that people should start wiping their noses on their sleeves when they have a cold instead of tissues. She dislikes paper napkins, too. So she wants folks to use their sleeves instead of paper napkins when they eat. She hopes that new sorts of removable, replaceable sleeves can be developed that would make the behavior we were criticized for as children more acceptable to the population at large. She figures that if we do these “simple things” then we’ll save a lot of trees. Obviously having crusty sleeves will improve our lives immensely. Anything for the trees.

Such attitudes, which seem, for those not infected by them, to have as their aim to just make life more nasty, brutish and short—are remarkably common. After all, we all have behaviors that someone, somewhere disapproves of. My wife dislikes it when I make slurping noises, for instance. My children dislike it when I tell them to clean their rooms. The Taliban thinks it’s awful that Americans listen to music and our women wear clothing that won’t make them pass out from heatstroke on hot summer days.

We all have pet peeves, whether it is people downloading porn, owning handguns, smoking, or driving an SUV. There are always people wanting to insist that our video games have too much violence, our books express ideas that are destructive to civilization, and that allowing kids to watch movies with stuff blowing up in them will automatically turn them into serial killers.

There are no shortages of those who want to control what we eat, what we drink, what we read, what we think, where we go, who we talk to. They insist that certain foods will cause our hearts to explode, cancer to bloom, deplete the environment, damage the world, and rot teeth. Some of these people are religious, some are political. Some are conservative, some are liberal. They are all well-intentioned, seeking what’s best for us, what’s best for society, what’s best for the children.

In essence, such people who spend their time telling us what not to do are simply incapable of finding joy in life. The glass is always half-empty. The sky is always falling. The world is forever on the brink. They are forever afraid that being content or being happy is going to destroy life as we know it and life as we know it is always, they insist, barely tolerable. Whether it is a scold berating us for allowing “those” sorts of people to run amuck and warning in dire terms that if such behavior is not nipped in the bud then we face imminent destruction—or someone proclaiming that unless we change our ways in regards to overpopulation, driving cars, eating meat, or owning guns that the world will end, the children will die, and civilization will collapse—the end is always near.

We make fun of the clapboard-draped man with scrawled words announcing, “repent, the world ends tomorrow.” And yet we listen with tolerance and approval to men in suits with celebrity status who solemnly inform us that if we don’t change our profligate ways the world will be destroyed, our arteries will clog, or our children will be stunted, and they’ll be made stupid.

Legalists inform us that if we pass laws regulating what words we are allowed to say, what terms we use to define situations, people and conditions, then the millennium will dawn and we will all live in harmony singing a pleasant tune (but not too loud, lest we damage our ears).

Meanwhile, while one group gets mad when it is suggested that their behavior is immoral in regards to sex or drugs (and will insist that such moralizing is “wrong”), the angry group will then berate those who own guns or drive big cars or eat red meat. Scolds are everywhere, even among those who say they don’t believe in values. And they are certain that they know how everyone else must act—after all, it’s for the good of the planet and for the sake of the children.

And disagreeing with the scolds of the world doesn’t mean that you’re wrong, or merely have a different opinion. No, you’re the enemy and you’re evil and you must be stopped (though we must never judge others). That’s always the bottom line for the scolds of the world: we’re all bad boys and bad girls who need to have our candy taken away. Fun is overrated, anyhow, they’ll have us know.

February 22, 2013

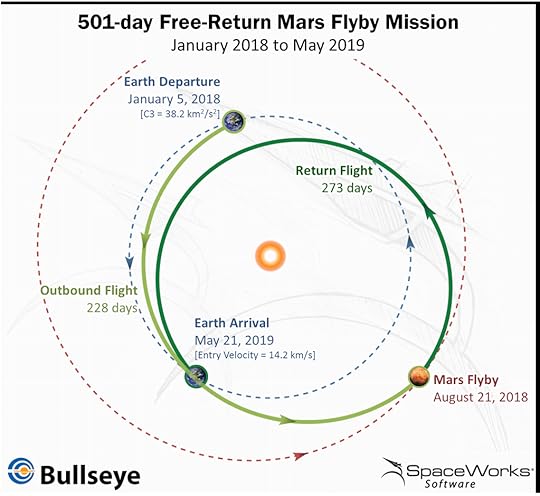

Mars Flyby in 2018?

According to news reports, Dennis Tito, the first tourist to travel in space back in 2001, when he took a trip to the space station, is apparently planning on orchestrating a flyby of Mars in 2018. Why then? Because that’s when the orbital setting is just right for a 501 day free return flight. The orbital geometry won’t be right again until the 2030s. Few details for the plan have emerged; the official press briefing won’t come until next Wednesday, on February 27. But according to some sources, it appears the idea is to use a SpaceX Falcon Heavy to launch a modified Dragon capsule with two astronauts who would then fly their Dragon spaceship past Mars and back again. Some have wondered if perhaps the Dragon would link up with a Bigelow module, but there is no official word to support that speculation, either.

Still, the 21st century is shaping up to be interesting: Space Adventures offers–for very high prices–tourist voyages to the space station and even around the moon. Meanwhile, two corporations have been formed to mine asteroids. Multiple private companies are competing to ferry astronauts to the Space Station for NASA, with SpaceX and their Falcon 9/Dragon combo clearly in the lead. And now this.

Fascinating times.

This is the path the 2018 mission to Mars would probably take.