R.P. Nettelhorst's Blog, page 118

April 22, 2013

SETI

SETI, the Search for Extra-Terrestrial Intelligence, is now more than fifty years old. In 1959, the Cornell physicists Giuseppi Cocconi and Philip Morrison published an article in the journal Nature proposing the idea that it might be possible to use microwave radio to communicate between the stars. The next year, in 1960, Frank D. Drake, a radio astronomer at the National Radio Astronomy Observatory in Green Bank, West Virginian carried out the first attempt to detect such interstellar radio transmissions. Drake named this first attempt Project Ozma, after the Queen in L. Frank Baum’s land of Oz. Oz, he said, was a place “very far away, difficult to reach, and populated by strange and exotic beings.”

Drake chose to listen to two nearby stars, Tau Ceti, which is located in the Constellation Cetus and Epsilon Eridani in the Constellation Eridanus. They are both about 11 light years away and are similar to the sun in age and brightness.

Unfortunately, no radio waves were actually detected during the time that Drake listened to those two stars, from April through July of 1960. Of course, he only listened to one channel during that time, the 1420 MHz line of neutral hydrogen because of its supposed astronomical significance. In fact, no artificial radio waves have ever been detected from anywhere in the sky during any SETI project.

The first scientific conference devoted to SETI research took place at Green Bank, West Virginia the next year, in 1961. Later, throughout the 1960’s, the Soviet Union performed a number of searches with omnidirectional antennas in the hope of picking up powerful radio signals. In 1966, American astronomer Carl Sagan and Soviet Astronomer Iosif Shklovskii wrote the pioneering book in the field entitled, Intelligent Life in the Universe.

In 1971 NASA funded a SETI study that involved Rake, Bernard Oliver of Hewlett-Packard Corporation and others. The resulting report proposed the construction of an Earth-based radio array with 1500 dishes known as Project Cyclops. The array was never constructed.

In 1974, after a major renovation of the radio dish, a largely symbolic attempt was made at the Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico to send a message to other worlds. It was aimed at the globular star cluster M13, which is 25,000 light years away. If that message is detected by anyone out there, we still have about 50,000 years to wait before we’ll receive their reply.

Most SETI research in the United States has been done by universities and private organizations. For one year in 1992 the U.S. Government funded the NASA Microwave Observing Program (MOP) which was planned as a long-term effort to conduct a general survey of the sky and to carry out targeted searches of 800 specific nearby stars. Congress soon eliminated the funding, but the project was resurrected by the nonprofit organization, the SETI Institute of Mountain View, California. MOP was renamed Project Phoenix and was directed by Jill Tartar. Project Phoenix observed about 800 stars over the frequency range of 1200 to 3000 MHz from 1995 through March, 2004. The search was sensitive enough to pick up alien transmissions of a gigawatt or more up to a distance of about 200 light years. The Arecibo message of 1974 was sent at that power level, for instance.

Today, the SETI Institute is still busy. It is collaborating with the Radio Astronomy Laboratory at UC Berkeley to develop a specialized radio telescope array for SETI studies. It is called the Allen Telescope Array, named after Paul Allen, the project’s primary financial benefactor. Paul Allen was a founder of Microsoft and he financed SpaceShipOne, which won the Ansari X-Prize in 2004. When completed, the full radio telescope array will consist of 350 or more radio dishes, each about twenty feet in diameter. The first portion of the array, made up of forty-two dishes, became operational in October, 2007. Unlike the first Ozma search in 1960, the Allen Telescope Array monitors hundreds of millions of radio channels all at once.

Detecting signals at interstellar distances will not be easy to accomplish. And even if there are civilizations out there, they may not be purposely transmitting. For instance, the Earth has been radiating radio signals, radar, and television signals for more than seventy years now, meaning that the earliest signals form a bubble out from Earth seventy light years in diameter, enveloping hundreds of stars. However, even if there were a civilization similar to ours within that distance of Earth, none of the SETI instruments currently operating would be able to detect such radio or television signals. At interstellar distances, they are just too weak to separate from all the more noisy radio signals put out by stars, dust and gas. They are lost in the static.

This is not to say that SETI is a waste of time, however. But it is to say that the absence of any detectable transmissions from beyond Earth thus far doesn’t prove that no one is out there. Given the size of the universe, it would seem an awful waste of real estate if we really are the only intelligent beings in it.

April 21, 2013

Serendipity

Send to Kindle

Send to KindleIn 1945 Nazi Germany was finally defeated. One of the things that had helped bring about its defeat was the successful breaking of what the German’s thought was an unbreakable code.

At the end of the First World War a German engineer named Arthur Sherbius invented a cipher machine called Enigma. As children, many of us played with substitution ciphers using a kind of code machine consisting of concentric circles on which were printed the alphabet. I remember getting a plastic cipher machine out of a box of cereal. It was made of gold colored plastic and was about the size and thickness of a small jelly jar lid. There were two concentric circles, and the one on the outside moved. After twirling, when I compared the two rings, the A on the outside one might be aligned to the D on the inside, the B to the E, and so on. So I could write a “code” that could only be read if someone knew that when I wrote down the letter F it actually stood for the letter C and so on. Such a simple cipher could be broken in minutes, since there are but a small number of possible combinations and certain letters, such as E and the other vowels, are statistically more common.

The Enigma machine was a much more sophisticated and complicated cipher machine, consisting of at first three, and later, five circles or rings. The relationships between the letters on the rings varied with each keystroke. To know how to put a message back together, the recipient of the message would need to have the keycode that told the machine when and how to make the shifts in the rings. The complexity and shifting nature of the substitutions within a single text made the Enigma machine’s ciphers very hard to decipher. The Germans actually believed they were unbreakable.

Before World War II the Enigma machine was used commercially. It was later adopted by the military and government services of several nations. So in December, 1932 the Polish Cipher Bureau managed to break Germany’s military Enigma ciphers on some of the earlier Enigma machines. Five weeks before the outbreak of the Second World War, Poland gave what they had learned to the French and the British.

The British government then created a military intelligence agency called Ultra. Ultra obtained and broke high-level encrypted enemy radio and teleprinter communications at the Government Code and Cypher School in Bletchley Park. The British called their program “ultra” because it was even more secret than top secret. Many of the participants in the war, ranging from Winston Churchill to Dwight D. Eisenhower believed that the decryptions obtained at Bletchley Park were decisive in the allied victory in World War II. One historian, Sir Harry Hinsley, believes that Ultra shortened the war by two to four years.

And how was it that the British were able to break the Enigma ciphers? It was mostly due to the work of two men: Polish mathematician, Marian Rejewski and British mathematician Alan Turing. In 1932 the Polish intelligence bureau received two German documents and two pages of daily key codes from the French. That allowed Rejewski to make a significant breakthrough in using the theory of permutations and groups to work out the Enigma scrambler wiring. He first worked it out using paper, but ultimately came up with an electro-mechanical device that was called the cryptologic bomb. It could sort through and determine which of the more than seventeen thousand possible keycodes was being used in a text in about two hours. This worked well on the Enigma machines using three rings, but not so well after 1938 when the Germans increased the complexity of their Enigma machines by adding two more rings.

Alan Turing, in 1939, designed an electromechanical “bombe,” building on the earlier work of Marian Rejewski. Turing’s machine was designed for the much more general approach to solving the ciphers. From this early system, the Colossus machine was later constructed in 1943. It was the world’s first electronic, digital, programmable computer. Its purpose was narrow, however, since it was tasked with only one job: decrypting the German codes. And unlike modern computers, Colossus had no internally stored programs. For each task it performed, its operators had to set up plugs and switches in order to physically rewire it.

It wasn’t until after the war, in 1946, that Turing presented a paper to the National Physical Laboratory Executive committee, giving them the first complete design of a stored-program computer. Although it still used vacuum tubes, Turing’s design was a computer of the modern sort: it was flexible and programmable.

The modern computer that is today ubiquitous, and used for everything from word processing to playing Angry Birds, is largely the serendipitous result of the need to find a quicker way to decode German cyphers that had been created by their Enigma machines.

Send to Kindle

Send to Kindle

April 20, 2013

The Bartender Effect

Send to Kindle

Send to KindleIf you are an authority figure in the life of people around you, you’ll likely wind up with them confiding their darkest secrets to you. Bartenders, I’m told, experience this. Certainly pastors certainly do. And sometimes administrators, teachers and college professors have it happen to them.

I’m an ordained deacon, an adult Sunday School teacher, and a college professor. It happens to me a lot. I need to point out that most of the people who unburden themselves to me are not my friends (though I have had friends do this to me, too). In fact, most of the folks who have told me the sad tales from their lives barely count as acquaintances. And yet they are happy to tell me details of themselves that are startling. I would be mortified if I had such struggles in my life, and I can’t even imagine why I’d tell someone I hardly know all about them.

Sometimes while I’m struggling to keep the look of surprise off my face while I’m being told an unexpected confession, I remember an old joke. Three pastors met one day for lunch. The first pastor looked at his companions and told them, “I’m burdened with my problems. Would you mind if I shared them?”

“Go right ahead, brother.”

“Ever since I became pastor, I’ve struggled with my greed. It would be so easy, some Sunday, to slip my hand into the collection plate and simply take some of that cash for myself.”

“You’re not alone in having struggles,” confessed the second pastor. “I’ve had a problem with lust all my life. Sometimes when the organist is playing, it’s all I can do not to stare at her legs. And I can’t express how hard it is for me to avoid the porn sites on the internet.”

The third pastor by this time was grinning, barely able to contain himself. At last he burst out, “I’m sorry, but I have to confess that I have a terrible problem with spreading gossip!”

Thankfully, I don’t have a gossip problem. In fact, I find just the opposite: I have trouble remembering the details from what people tell me when they open themselves up like that. Which can be a problem if a week or two later they ask me what I thought, or start telling me what has happened next and I don’t remember what went before.

I think part of the way I handle all the unhappy information is that I don’t internalize it. Instead, I let is slip away from me: in one ear and out the other. I don’t dwell on what they tell me, I don’t contemplate and concern myself with any thought of what I would do in their situation. I don’t let myself focus on what they told me. It doesn’t keep me up at night.

I know, especially since this happens to me regularly, that most folks are just happy to have someone that they can talk to. They want someone who will listen calmly, without reacting negatively. Mostly, all people really need is a warm body to pour their words into.

As to why people feel comfortable unburdening themselves to someone that they don’t really know all that well, I’m not entirely certain. What leads them to trust a stranger with their intimate worries and problems?

I’m not unique in having it happen to me, though. My wife occasionally works with new teachers in her school district. It’s a mentoring position. She finds that it is not uncommon for them to open up to her—and not just about issues in their classrooms, but private matters as well.

Still, I think it happens to me a bit more than to most people. I’ve had strangers in stores, restaurants, and on street corners suddenly start talking to me about the oddest things. It even happens in the virtual world. Given the fact that I run the website for our seminary, I get email from random strangers. Most are simple requests for information, but every so often I’ll get an email that pours out the most heartrending information.

Thankfully, people who turn to me to talk about their misery are rarely, if ever, looking for solutions or advice from me. They just want someone to talk to. As to why they don’t talk to their friends instead, I’m not certain—particularly since I have friends who do the same thing to me that strangers do, but in that case, I don’t find it odd. Friends should be able to open up to one another. Life can be cruel. I can’t imagine facing it alone.

I wonder if there are simply a lot of people out there who don’t have any close friends or family to help support them through life, so they reach out in desperation. Perhaps some percentage of those in therapy are there simply because they don’t have anyone in their lives that they are close enough to, or comfortable enough with, to confide in.

Or maybe someone taped a sign on my back that instead of saying “kick me” says, “therapy for free.”

Send to Kindle

Send to Kindle

April 19, 2013

No Moral Equivallence

Send to Kindle

Send to KindleThe horrible events in Boston bring out the worst in some people.

I really do not understand those who believe that there is no difference between the actions of terrorists and the actions of the U.S. military. And I say this not just because my father spent 28 years in the Air Force and served in Viet-Nam twice.

On Facebook, someone recently posted a photograph of a row of dead babies supposedly killed by an American drone in Afghanistan and suggested that America is no different than those we call terrorists:

Matthew Keys, the social media editor at Reuters, posted audio of a reporter asking White House Press Secretary Jay Carney if U.S. bombings that kill innocent civilians in Afghanistan constitute an “act of terror” given the labeling of the Boston Marathon bombing as “terrorism”. She specifically refers to a U.S. airstrike earlier this month that killed 11 children, just the latest in a seemingly endless line of Afghan civilian deaths at the hands of the U.S. government.

Some people that we’re hypocrites for reacting with outrage over the events in Boston given that what we’re doing (through our military) every day in Afghanistan is just as bad, if not worse.

This all too common attitude is both incredibly offensive and flat out insane.

It is indeed awful when innocent civilians are injured or killed as a result of U.S. military activity (though not all reports of such things are true or accurate, but that’s another issue altogether). Such deaths are what are known as “tragedies.” Such deaths are not murder. They are not terrorism.

There is a significant difference both morally and legally between murder and manslaughter. This is recognized rather early in the Bible, for instance:

When the LORD your God has destroyed the nations whose land he is giving you, and when you have driven them out and settled in their towns and houses, then set aside for yourselves three cities in the land the LORD your God is giving you to possess. Determine the distances involved and divide into three parts the land the LORD your God is giving you as an inheritance, so that a person who kills someone may flee for refuge to one of these cities.

This is the rule concerning anyone who kills a person and flees there for safety—anyone who kills a neighbor unintentionally, without malice aforethought. For instance, a man may go into the forest with his neighbor to cut wood, and as he swings his ax to fell a tree, the head may fly off and hit his neighbor and kill him. That man may flee to one of these cities and save his life. Otherwise, the avenger of blood might pursue him in a rage, overtake him if the distance is too great, and kill him even though he is not deserving of death, since he did it to his neighbor without malice aforethought. This is why I command you to set aside for yourselves three cities.

If the LORD your God enlarges your territory, as he promised on oath to your ancestors, and gives you the whole land he promised them, because you carefully follow all these laws I command you today—to love the LORD your God and to walk always in obedience to him—then you are to set aside three more cities. Do this so that innocent blood will not be shed in your land, which the LORD your God is giving you as your inheritance, and so that you will not be guilty of bloodshed.

But if out of hate someone lies in wait, assaults and kills a neighbor, and then flees to one of these cities, the killer shall be sent for by the town elders, be brought back from the city, and be handed over to the avenger of blood to die. Show no pity. You must purge from Israel the guilt of shedding innocent blood, so that it may go well with you. (Deuteronomy 19:1-13)

The U.S. Government does not try to kill children. Children are not targets of our soldiers. If children die or suffer injury as a result of U.S. actions in Afghanistan or elsewhere it is a tragic accident.

Terrorists, on the other hand—for instance Timothy McVeigh, Hezbollah, Hamas, Al Qaeda and the like—do purposely target children. They delight in killing innocent people. Killing innocent people is their goal when they place bombs in office buildings, at the Boston Marathon, or fly aircraft into sky scrapers.

Beyond that, the terrorists of the world regularly and purposely place women and children around their installations, using the innocents as human shields in the hope that we won’t risk attacking them, but knowing that if we do, then their deaths can be used to demonstrate just how evil America is.

It strikes me as odd when I see the photos of people killed in drone attacks. Who would carefully line up dead children and then snap gruesome pictures of them? How do we even know that an American weapon was responsible for their deaths? And why are so many in the U.S. and around the world willing to take the word of people who gleefully kill civilians, take hostages and cut off their heads, stone women for the crime of being raped, hang homosexuals, and kill Christians and Jews simply because they are Christians and Jews? Are the Timothy McVeighs of the world really trustworthy sources of information?

Look, this is not hard. If a police officer accidently kills someone in his or her attempt to catch a criminal—as for instance in a hostage situation—that is tragic. But the police officer is not the moral equivalent of a criminal who takes a hostage and cuts off his head.

Why do some people find it so hard to tell the difference between Al-Qaeda and the United States?

Send to Kindle

Send to Kindle

April 18, 2013

Seasons

Send to Kindle

Send to KindleSouthern California does not have seasons like most of the rest of the country. The temperature in Los Angeles stays pretty even all year round. But we do have periods of the year where it rains, and periods when it usually doesn’t. We have periods when the winds blow harder than at other times, and we have times when we are more likely to suffer from wild fires. So while we may not have the radical changes of the traditional winter, spring, summer and autumn, there are still noticeable differences between July and January.

Life has seasons and like Southern California, they do not fall into four neat categories; nor do they follow any particular pattern. One cannot experience something in life and then think, well spring is coming or “after this, it’s going to be winter.” Still, the concept of “seasons of life” is a useful analogy.

We sometimes say, “Into each life a little rain must fall.” Sometimes that feels more like a flood, to maintain the Southern California analogy. And then we get hit with the mudslides and forest fires.

With any crowd of people, we can probably arrange them into three seasons: one section will be metaphorically sunning themselves on the Riviera, their lives near to perfect as they can get. Another section will be watching their umbrella tumble down the road as they get drenched in a monsoon. But the bulk of the people will simply be sitting in an office, a half drunk coffee gone to lukewarm on their desk, and a small stack of papers in their inbox: they are largely content, they have a few problems but nothing beyond managing, and life is sort of ordinary. That’s where we all live most of the time: bills to pay, children to get to soccer games, short of time and long on things to do. Everything is mildly hectic and we’re looking forward to a break on the weekend. Tonight we expect to kick back on the couch, watch some TV, and then head off to bed. And in the morning, we’ll do it all over again.

What is important to realize is that we will have to live through all three seasons, in no particular order. Most months will be the just okay place. The Riviera time we won’t have any trouble putting up with. It’s the monsoon season that’s the problem.

In the time of disaster, the comfort is to remember that it won’t last forever. Season’s always change. On September 30, 1859, Abraham Lincoln told a story in an address before the Wisconsin State Agricultural Society in Milwaukee:

“It is said an Eastern monarch once charged his wise men to invent him a sentence, to be ever in view, and which should be true and appropriate in all times and situations. They presented him the words: ‘And this, too, shall pass away.’ How much it expresses! How chastening in the hour of pride! How consoling in the depths of affliction!”

For many, Lincoln’s words are so familiar that they barely register. They have become an empty platitude. But platitudinous or not, Lincoln’s words are still true and if we choose, they give us insight into how to keep life’s seasons in perspective.

In his poem “If,” Rudyard Kipling wrote that triumph and disaster were both imposters and that we should learn to treat them just the same. That is, we need to recognize how transient our seasons are and how to rise above them. “If you don’t like the weather, just wait a bit. It will change.”

Lincoln’s words are but one way to express the old truth of life’s seasons. When a Roman general returned in triumph from his conquests, he was granted a magnificent parade called a Triumph. His soldiers, their captured booty, their defeated foes were paraded down the street and at the end of the parade, in his chariot, rode the general, with a slave whispering words into his ear: “Look behind you, remember you are only a man” and “Remember, you are mortal.”

Similarly, Paul wrote in a letter to a church in the ancient city of Philippi:

“Finally, brothers and sisters, whatever is true, whatever is noble, whatever is right, whatever is pure, whatever is lovely, whatever is admirable—if anything is excellent or praiseworthy—think about such things. Whatever you have learned or received or heard from me, or seen in me—put it into practice. And the God of peace will be with you.

“I rejoiced greatly in the Lord that at last you renewed your concern for me. Indeed, you were concerned, but you had no opportunity to show it. I am not saying this because I am in need, for I have learned to be content whatever the circumstances. I know what it is to be in need, and I know what it is to have plenty. I have learned the secret of being content in any and every situation, whether well fed or hungry, whether living in plenty or in want.” (Philippians 4:8-12)

Life has seasons. We can get through them all. Over and over again.

Send to Kindle

Send to Kindle

April 17, 2013

Science Fiction

Send to Kindle

Send to KindleThe first science fiction novel I remember reading was by Robert Heinlein. It happened to be his first novel, entitled Rocket Ship Galileo. Published originally in 1947, it told the story of a nuclear scientist and some boys who built a rocket, then flew it to the moon where they had to fight against some Nazis. Just the sort of story that would capture the imagination and heart of a third grade boy.

After that, I sought out other books that were, as I called them, “space stories.” My elementary school in Westerville Ohio was rather small. Even remembering it through the eyes of an 8 year old, the library still seems inadequate: little more than a narrow closet packed with dusty volumes. Therefore, I soon exhausted the available stories. But, there was still the local public library, and I quickly located their collection of science fiction. I began with children’s books, of course, but it wasn’t long before, with my mom’s help, I was able to move on to the grown up books.

Over the years, my tastes in science fiction broadened. I discovered that there was much more to science fiction than just space opera.

For the uninitiated, their idea of science fiction might be limited to the bad movies that Hollywood has manufactured. Likewise, a lot of the science fiction books out there are admittedly not really very good. But, as Gene Roddenberry, the creator of Star Trek, once said, 90 per cent of everything is junk.

The remaining ten percent of science fiction has nothing to be ashamed of. A good science fiction story, like all great literature, deals with issues beyond its setting in space, beyond all the fancy gadgetry. In fact, the gee-whiz is mere decoration for the basic human problems that are discussed, ranging from questions of whether life has meaning, to the nature of reality, human relations, and questions of love and war. Coming of age stories, romance, heartbreak and struggle all appear within its pages. But beyond that, the stories can ask questions that no other literature will touch: the implications both philosophical and theological of progress, linked to warnings about the boxes opened by technological Pandoras.

Interesting sub-genres have formed. One of my favorites is most commonly known as “alternate history.” It is a mental experiment: one looks at a turning point in history and contemplates what might have happened had things turned out a different way. For instance, a British soldier had George Washington in his rifle sight and chose not to pull the trigger. What if he had? Or what of the lost battle plans belonging to Robert E. Lee that in the real world were recovered by a northern soldier, thereby contributing to Lee’s loss of an important battle. What if the plans had not been lost?

What if the Spanish Armada had not been wiped out by a storm and instead had successfully conquered England just before the time of Shakespeare?

Harry Turtledove, trained as a historian, is a science fiction author who has contemplated many of these questions and has written detailed novels following up how the world might have turned out differently—focusing often times on how the lives of people we know from history could have been transformed, as in his novel Ruled Britannia, where Shakespeare writes subversive plays against the Spanish overlords and plots rebellion.

What if’s can sometimes be remarkably improbable, and still raise interesting questions worth exploring. Eric Flint has written a series of novels, beginning with one entitled 1632 (and currently available for free on Amazon for the Kindle or Kindle app), in which he assumes a West Virginia mining town from the year 2000 is suddenly and unexpectedly transported whole into Germany in the middle of the Thirty Years War. His focus is on the effect of modern ideas on seventeenth century Europe, rather than on the consequences of unexpected modern technology. So he plays with how American ideas of freedom of speech and religion, democracy, and limited government interact and alter the balance of power in old Europe. He imagines the discussions a post-Vatican II Catholic priest might have with a seventeenth century Pope. And what about our modern concepts of hygiene and disease? Or how do the kings and other tyrants of the seventeenth century react to reading about their lives in twenty-first century textbooks?

John Scalzi wrote a book a couple years ago called Old Man’s War in which he considers an odd question. What if a technology developed that could make people young again after they had gotten old—but it was only given to those who, on their 75th birthday, agreed to sign up to become soldiers fighting an interplanetary war?

Sarah A. Hoyt has written a series of books beginning with Darkship Thieves. The main character, Athena Hera Sinistra wakes up in the middle of the night in her father’s space cruiser, knowing that there was a stranger in her room. From there, she fights for freedom and for explanations; she winds up learning many dark secrets about her father, herself, and the world she thought she knew.

If you haven’t read any science fiction lately, or perhaps never at all, you might want to give it a try. You may be surprised by where it will lead you.

Send to Kindle

Send to Kindle

April 16, 2013

The Problem of Suffering

Send to Kindle

Send to KindleThe problem of suffering—why a good, powerful God would allow pain and misery—is one that has troubled many, at least since the time of Voltaire. In his book Candide, the atheist Voltaire tries to demonstrate that the horrors that can occur, ranging from war to earthquakes, the death of children from disease and famine, is incompatible with a belief in a God who is benevolent. The Deists tried to escape Voltaire’s conclusion by assuming that God created the universe but that he then stepped away from it as a painter might step away from his completed canvas and never touch it again with his paintbrush.

Either way—a God who starts the world up and then ignores it, or no God at all—results in the same sort of world: one lacking the hand of God. So, assuming then, that our world were devoid of God what would it be like? Would it be the world we actually experience, in which case Voltair or the Deists have reality nailed, or would it be something different?

The difference between Voltaire’s or the Deist’s world and a world in which God intervenes, in a certain respect would be subtle—because I believe that God’s involvement in our world is subtle. But subtle does not necessarily mean the differences between the two possible worlds would be small. “For want of a nail the shoe was lost. For want of a shoe the horse was lost. For want of a horse the rider was lost. For want of a rider the message was lost. For want of a message the battle was lost. For want of a battle the kingdom was lost. And all for the want of a horseshoe nail.” So goes the old proverb. For lack of God’s movement among us, the world would be a much darker place than the one we find ourselves in.

If one assumes a benevolent, powerful deity, then one would reasonably also assume that he would create the best of all possible worlds. And by “best” we mean one that maximizes pleasure and minimizes suffering. As a Christian, I would argue that God involves himself only to the extent that it maximizes good and minimizes evil without unduly encroaching human freedom and free will.

Consider a free market economy operating according to Adam Smith’s “invisible hand” of the market. God, to follow the analogy, is essentially the “invisible hand” of the universe. John Allen Paulos, professor of mathematics at Temple University has pointed out that most economists believe that “simple economic exchanges that are beneficial to people become entrenched and then gradually modified as they become part of larger systems of exchange, while those that are not beneficial die out. They accept that Adam Smith’s invisible hand brings about the spontaneous order of the modern economy.” Paulos explains that thanks to the free market, you can walk into any store that sells clothing and find something that fits you in a style you like—or if that particular store lacks your particular and peculiar interests, then you can go to another store and another until you do find what you want. Consider a box of corn flakes and the complex process that gets it into your hands at Wal-Mart. Farmers grew the corn; they used modern chemical fertilizers, perhaps used irrigation to water the crops, used machinery to plow and later harvest the fields—machinery that someone else manufactured through its own complex process. Meanwhile, another corporation made cardboard from trees harvested by a lumbering company, shipped the cardboard to a box making company that printed the labels on the cereal box that had been designed by a marketing department somewhere else, using inks purchased from some other company, using printing equipment made by still another…and then the cereal company took the farmers corn, processed it, cooked it and made the flakes which were then put into the boxes, which were then ordered by stores all over the world, some of which made their way by boat, train, plane or truck to your particular store to be tossed unceremoniously into your shopping cart.

No one central planning committee, no single individual, could make that happen. It is a hard for many to accept: that random and free exchange can produce order. It is counterintuitive. But centralized planning and centralized economies always and without exception fail. Instead, it is the counterintuitive free market that gives us everything that the centralized economies would want but always fail to provide.

Counterintuitively, order comes from freedom, while stasis and anarchy grow from attempts to impose control. I believe that God maximizes the order of his universe and the order on our particular planet by ensuring the free will of his creatures. God’s sovereign will is expressed as a consequence of our free will.

But taking this to an extreme gives us the universe of the Deists, with an uninvolved God. Just as too much government is bad, none at all is likewise a disaster.

With zero intervention by God things could get really bad, really fast. His light and mild hand on our throttle keeps things from getting any worse than they otherwise might. His gentle touch creates a world that is the best possible, given our free will.

So for instance, where was God during the Holocaust? In the armies of the allies. He was bombing the stuffing out of Nazi Germany. The Holocaust is disturbing, but think how much more disturbing it would have been had the Nazis won. With no God, that would have been a possibility. Instead God intervened—perhaps less intensively than we might wish—to limit evil, to put boundaries around it. But he minimizes his interference so as to leave us our freedom.

Consider a totalitarian government. It can control the means of production, what appears on television, what people read, what people say, who they associate with, how they worship, where they go. Minor crimes are punished severely: blasphemers are stoned, thieves have their hands hacked off, adulterers are hanged, and so on. Such a society is ordered and everyone is forced to be “good” and very little “bad” ever happens.

Do you want to live there? A free society is messy: criminals get away with things and are not always punished as severely as we might like. People say and do things that annoy others. People litter. But I think most people would much prefer a free society to a dictatorship.

God apparently thinks that way too. He prefers our freedom. The Bible story of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden illustrates that point. God told them not to eat from the tree of the knowledge of Good and Evil. And yet they did.

If good behavior were what mattered most to God, he would not have given them the opportunity to disobey, nor ever allowed them to do so. All the mess of human history grows from the bad decision Adam and Eve made. Clearly, the God we see revealed in the Bible thought freedom was worth that price.

So, in conclusion, if God did not intervene in the world at all, the Nazis could win, slavery would endure, and evil might never be thwarted. Since God does intervene, good ultimately triumphs. God does prefer good; but he has decided that the best way to get it is by means of, metaphorically, a lightly regulated free market rather than either a command economy or sheer anarchy.

Send to Kindle

Send to Kindle

April 15, 2013

The Incompetence of the Political Class

Send to Kindle

Send to KindleActually, the general incompetence of the government is a good thing; it keeps the government, most of the time, from really doing much that harms us. And that was the goal of those who created the constitution. As Thomas Jefferson has been quoted as saying, “The best government governs least.” By dividing the government into three competing branches, the legislative, executive and judiciary and in other ways making the process cumbersome and inefficient, they have forced our elected servants to scramble, compromise, and busy themselves excessively with attempting to accomplish anything. That’s good, because when they actually do accomplish something, nine times out of ten, their good intentions have really nasty consequences.

For instance, the small seminary I teach at has a website, www.theology.edu. When we first acquired that domain name in the early 1990s it cost us nothing to secure the name and nothing to keep it. Then, about ten years ago, the government gave an exclusive contract to a company called Educause to administer all the websites that have a .edu address. So Educause started charging 40 dollars a year for what before had cost us nothing.

Now, forty dollars isn’t a whole lot, but of course Educause, in reality, doesn’t have much to do except to collect that money. They don’t host the website, they don’t maintain the website, and they don’t have anything to do with managing at all; they just collect the money.

My concern with them is the simple fact that they have a monopoly. If you have a .com address, you can find any number of companies to register your domain and keep it alive and it usually costs ten dollars or even less per year to register the name. Sometimes you can get it for free. The only money you pay then is for whoever actually hosts the site on their servers (in the case of theology.edu, we are fortunate in that one of our former students hosts websites as a side business, and so hosts our site for free). Given that Educause is the only game in town—or anywhere in the US—for registering the .edu addresses, they can charge whatever they want. We have no choice if we want to keep our address. We have to pay them annually. What is to keep them from jacking up the price someday if they so choose? Nothing. Already, they charge four times what most places would charge for any other domain ending in .com, .org. or .net.

On June 29, 2011 the State of California passed a budget bill that our governor signed. Buried inside it, was a little item that was designed to raise sales tax from the likes of Amazon.com. Because Amazon.com is located in Seattle, Washington, rather than California, they are not required to collect sales tax. Unless a vendor has a physical location, or nexus, within a state, the vendor cannot be required to collect tax for that state. This limitation was defined as part of the Dormant Commerce Clause by the Supreme Court in the 1967 decision on National Bellas Hess v. Illinois. An attempt to require a Delaware e-commerce vendor to collect North Dakota tax was overturned by the court in the 1992 decision on Quill Corp. v. North Dakota. Thus, the Supreme Court has determined that states cannot force mail order businesses to collect sales taxes if they do not have a “presence” in the state. Therefore, Amazon was exempt from collecting sales tax except in the state of Washington. This has really annoyed a lot of the other states, and several have attempted to do what our legislature attempted to do in June. Amazon has a program called an Associates Program, whereby individuals, nonprofits and corporations can put a banner or link to a particular item on their website and then get five percent (or thereabouts) of any sales that are made by Amazon if someone purchases through that link.

“Aha!” thought our state legislature. “We’ll say that gives Amazon a ‘presence’ in California and now we can make them collect sales tax on anything they sell in the state.”

So what happened? Amazon simply terminated their Associates Program in California. All the owners of websites—such as theology.edu, or your neighbor’s blog—who collected a few dollars from these transactions—our seminary was lucky to make ten dollars a month—are now cut off. So, all the state of California managed to do was to cut the income of countless small entrepreneurs and nonprofits, while gaining no sales tax revenue. In fact, this was probably a net loss for the state of California, since all those countless people lost the income they were making—and declaring on their income taxes (Amazon made you give them your social security or tax id number when you signed up)—from Amazon’s Associates Program, which sadly no longer existed for California residents.

Eventually, Amazon and the State of California negotiated an agreement. But almost always, the amount of money the politicians imagine they will get for a given tax or fee always under-performs. The best example of this can be seen both in most municipal bus companies as well as in the postal service. The politicians notice that the revenue has declined because not as many people are riding the busses or mailing letters. So what do they do? The opposite of what any businessman would do. They raise their fees, calculating that since, for instance 10,000 people are currently riding the busses, and since they are bringing in X amount of money, then, to get the amount they now need, the must raise the rates by say 10 cents per rider. Then their budge will balance.

Of course they are shocked when next time around they find that ridership has declined again, to 9000; so they calculate how much income they need to meet their budget and add an additional amount to the cost of each ticket. The pattern continues, and they are constantly not bringing in enough money. Thus, surprising only the politicians and bureaucrats who run the postal service, the postal service is always losing money and it only gets worse every time they raise the cost of postage because ever fewer people are now using the postal service. The politicians never get wise.

With taxes, it works the same way; raise taxes too much and revenue will decline because a) employers cannot afford to pay as many workers, b) the workers cannot spend money they don’t have because of taxes, and/or c) there is an exodus of businesses, corporations, and individuals to other states that have lower taxes. Today many motion pictures and television shows are made outside of the state because it is cheaper for the movie and television companies to do it that way: other states offer lower taxes and other incentives, while California just piles on regulations, fees, and taxes. And then the government is always puzzled that they are running out of money and can never make ends meet.

I can’t say I’m terribly surprised. Our elected officials generally don’t seem to be gifted with common sense, let alone have any understanding of such things as tax law, human behavior, science, economics, education or history. They know how to run for office. That’s about it. Otherwise, they are incompetent.

Send to Kindle

Send to Kindle

April 14, 2013

Apollo 13

Send to Kindle

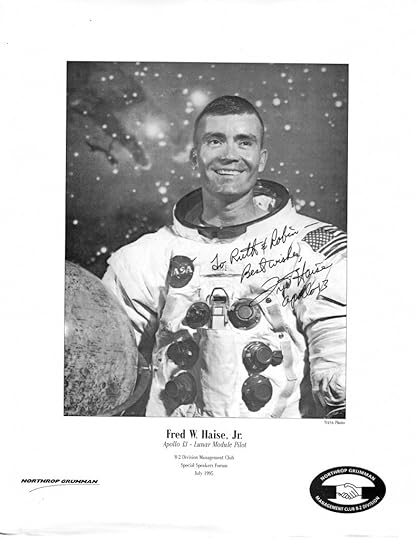

Send to KindleOn the night of April 13, 1970–43 years ago today–the words “Houston, we’ve had a problem” were uttered when an oxygen tank in the Service Module of the moon bound Apollo 13 exploded. The Lunar Module pilot of that mission, Fred W. Haise,Jr., gave a speech at Northrup-Grumman (builder of the Lunar Module) in July, 1995. My father-in-law was there (he worked on the B-2 project) and got Haise to sign and personalize a photograph to my wife and me.

Fred W. Haise, Jr.

I’m old enough to remember this event, just as I can remember the first moon landing. I was just 13 when Apollo 13 launched–at 13:13 CST on April 11. They returned safely to Earth on April 17.

According to Wikipedia:

As a joke following Apollo 13′s successful splashdown, Grumman Aerospace Corporation pilot Sam Greenberg (who had helped with the strategy for re-routing power from the LM to the crippled CM) issued a tongue-in-cheek invoice for $400,540.05 to North American Rockwell, Pratt and Whitney, and Beech Aircraft,[33][34] prime and subcontractors for the Command/Service Module (CSM), for “towing” the crippled ship most of the way to the Moon and back. The figure was based on an estimated 400,001 miles (643,739 km) at $1.00 per mile, plus $4.00 for the first mile. An extra $536.05 was included for battery charging, oxygen, and an “additional guest in room” (Swigert). A 20% “commercial discount”, as well as a further 2% discount if North American were to pay in cash, reduced the total to $312,421.24.[35] North American declined payment, noting that it had ferried three previous Grumman LMs to the Moon (Apollo 10, Apollo 11 and Apollo 12) with no such reciprocal charges.

Send to Kindle

Send to Kindle

April 13, 2013

The Importance of Perspective

Send to Kindle

Send to KindleWe each know remarkably little, no matter how old we may be, no matter how well educated we are. In the course of a single lifetime, how much can we actually read, watch and remember? How much of the world do we see and of what we see, how much do we truly understand? Do we ever get all the facts? Can we really cram the whole world both of today and yesterday into that small space between our ears? At best, our understanding can only be limited.

Benjamin Franklin, as an old man at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia the summer of 1787, commented, as he considered the final draft of the Constitution just before signing it, “I confess that there are several parts of this constitution which I do not at present approve. But I am not sure I shall never approve them. For having lived long, I have experienced many instances of being obliged by better information or fuller consideration, to change opinions even on important subjects, which I once thought right, but found to be otherwise. It is therefore that the older I grow, the more apt I am to doubt my own judgment, and to pay more respect to the judgment of others. Most men indeed as well as most sects in religion, think themselves in possession of all truth, and that wherever others differ from them it is so far error…But though many private persons think almost as highly of their own infallibility as of that of their sect, few express it so naturally as a certain French lady, who in a dispute with her sister, said, ‘I don’t know how it happens, Sister, but I meet with nobody but myself, that’s always in the right….’”

There’s always the subjective problem: all the new stuff that comes to us each day is filtered through what we already know–or think we know. Too often, we will see what we expect to see, rather than what is really there. What we know (or think we know) colors how we perceive things. It’s as if, after a quick glance at an optical illusion, we think we really understand the picture. We jump to conclusions with only half the story told.

Too often we live by slogans, imagining that a catchy phrase will serve the place of actual thought, or if it sounds good, it must be so. For instance, we might have heard the phrase, “Nothing was ever solved by violence.” It sounds profound. It’s certainly what we’d like to be true. And what we’d like to be true, what should be true, must be true. Right? But how did we solve the problem of Nazism? How did we solve the problem of slavery? And those are only two examples. Doubtless there are many soldiers and police officers, not to mention people being attacked by deranged wild animals, who could list several more times when violence was precisely what the doctor ordered. In the real world, facing real problems, the tongue-in-cheek military maxim comes closer to the truth: “There is no problem so large that it can’t be solved with a suitable application of high explosives.”

Another phrase I’ve heard: “Democracy can’t be imposed at gunpoint.” Some people actually believe this, I suppose, but it simply isn’t true, since we have, within relatively recent history, two examples of doing precisely that, with two radically different cultures, and in both cases, quite successfully. As I recall, neither Germany nor Japan had much experience with democracy prior to their defeats in World War II in 1945. And yet, at the very moment we were just starting to successfully transform those two former dictatorships into free societies, the nattering of negativity and pessimism dominated the pundit world.

In Life Magazine of January 7, 1945, an article announced that “Americans are losing the victory in Europe”, while the Saturday Evening Post of January 26, 1946 told its readers about “How we botched the German occupation”. John Dos Passos in his article in Life wrote that “Never has American prestige in Europe been lower.” He went on to discuss the disorder that followed the allied victory in Western Europe.

Meanwhile, the Saturday Evening Post article concentrated on the apparent lack of an exit strategy for getting American troops out of Europe. Demaree Best wrote, “We have got into this German job without understanding what we were tackling or why.”

A simple question. Were the pessimists right back in 1946?

And just how often are the pessimists ever right? As we consider what has gone before, do the bad guys usually and ultimately win? To help answer the question, consider a few other questions. Who won the Revolutionary War? Who won the Civil War? Who won World War II? Who won the Cold War? Have the number of democracies and free societies around the world risen or declined in the last hundred years? Did the Great Depression, which began in 1929 with the stock market crash and lasted more than a decade, render democracy obsolete, destroy America, end capitalism, destroy the American dream and leave everyone in poverty forever?

Is the world a better place today than it was a hundred years ago? Child abuse and spousal abuse were not issues a hundred years ago. Racism was not an issue a hundred years ago. Is that because such things did not exist a hundred years ago? No, it’s because most people didn’t recognize them as bad things a hundred years ago. Not only has technology improved in the last hundred years, but there has been some improvement in morality, despite what some people may feel about a given moral issue that they see as in the dumpster at the moment. And before they carp about some evil practice that bothers them, consider that whatever the evil practice might be, it’s not a new thing, nor is it likely more widespread today than it has ever been. And yes, there are societies before our own where their moral hobbyhorse was far more accepted and common than it is today. Immorality, of whatever stripe, is never new. People are people and have always had a tendency to break the rules. Which reminds us, passing more rules probably won’t solve much either, given our penchant for ignoring them when they are inconvenient. Or do you really always drive the speed limit?

The world is not getting worse and worse. It may seem worse to you now than it did when you were a child, but how much of the world did you know as a child? Getting old, having to go to work and all the attendant pressures of adulthood do make the past, when we were children, seem so much better, after all. Mostly, if we think the world’s worse off, it’s just because we’ve let our brains become cranky and we’ve lost perspective.

Send to Kindle

Send to Kindle