Peter Smith's Blog, page 41

August 20, 2021

Big Red Logic Book, no. 1 — a year on

It is exactly a year ago that the self-published version of An Introduction to Gödel’s Theorems was published as a paperback. It has sold over seven hundred copies in that time, and the monthly trend is slowly upwards. That’s three times as many copies as the CUP paperback was selling: but then, this print-on-demand version is a third of the cost! Still, the figure strikes me as surprisingly high, given that the PDF has also been freely available at the same time as the new paperback. I guess that quite a few people, like me, prefer to work from a physical book, if one is available at a modest price. As far as downloads go, AWStats currently reports about five hundred a month — though who knows exactly what these download stats really mean. And they can be volatile, month by month, though average numbers do stay pretty steady. Anyway, I count that as overall a happy success!

It is exactly a year ago that the self-published version of An Introduction to Gödel’s Theorems was published as a paperback. It has sold over seven hundred copies in that time, and the monthly trend is slowly upwards. That’s three times as many copies as the CUP paperback was selling: but then, this print-on-demand version is a third of the cost! Still, the figure strikes me as surprisingly high, given that the PDF has also been freely available at the same time as the new paperback. I guess that quite a few people, like me, prefer to work from a physical book, if one is available at a modest price. As far as downloads go, AWStats currently reports about five hundred a month — though who knows exactly what these download stats really mean. And they can be volatile, month by month, though average numbers do stay pretty steady. Anyway, I count that as overall a happy success!

Who knows if I will ever get round to a third edition. There’s tidying to be done, and I’d quite like to add a bit more around and about the Second Theorem. It would be fun to catch up with some reading and re-reading and re-thinking. But I don’t cringe when I occasionally have occasion to glance at the book: so I’m not yet feeling an urgent push to getting back to revising it right now.

The post Big Red Logic Book, no. 1 — a year on appeared first on Logic Matters.

August 19, 2021

An Introduction to Proof Theory, Ch. 5.

This chapter is on The Sequent Calculus. We meet Gentzen’s LJ and LK, with the antecedents and succedents taken to be sequences of formulas. It is mentioned that some alternative versions treat the sequent arrow as relating sets or multisets so the corresponding structural rules will be different; but it isn’t mentioned that alternative rules for the logical connectives are often proposed, making for some alternative sequent calculi with nice formal features. The definite article in the chapter title could mislead.

And how are we to interpret the sequent arrow? Taking the simplest case with a single formula on each side, we are initially told that A ⇒ B “has the meaning of A ⊃ B” (p. 169). But then later we are told that “we might interpret such a sequent [as A ⇒ B] as the statement that B can be deduced from the assumption A” (p. 192, with letters changed). So which does it express? — a material conditional or a deducibility relation? I vote for saying that the sequent calculus is best regarded as a regimented theory of deducibility!

Now, the conscientious reader of IPT will have just worked through over a hundred pages on natural deduction. So we might perhaps have expected to get next some linking sections explaining how we can see the sequent calculus as in a sense a development from natural deduction systems. I am thinking of the sort of discussion in the very helpful opening chapter ‘From Natural Deduction to Sequent Calculus’ of Jan von Plato and Sara Negri’s Structural Proof Theory (CUP, 2001). At the least, it would be good to ease the student in by starting with some natural deduction proofs and their sequent calculus analogues, to give a sense of how things work. But as it is, after setting up the calculus, IPT dives straight in to consider proof discovery by working back from the desired conclusion, with the attendant complications that arise from using sequences rather than sets or multisets. This messiness at the outset doesn’t seem well calculated to get a student to appreciate the beauty of the sequent calculus! However, the discussion does give some plausibility to the claim that provable sequents should be provable without cut.

A proof of cut elimination is the topic of the next chapter. The rest of this present chapter goes through some more sequent proofs, and proves a couple of lemmas (e.g. one about variable replacement preserving proof correctness). And then there are ten laborious pages showing how an intuitionist natural deduction NJ proof can be systematically transformed into an LJ sequent proof, and vice versa.

The lack of much motivational chat at the beginning of the chapter combined with these extended and less-than-thrilling proofs at the end do, to my mind, make this a rather unbalanced menu for the beginner meeting the sequent calculus for the first time. At the moment, then, I suspect that many such readers will get more out of, and more enjoy, making a start on von Plato and Negri’s book. But does IPT’s Chapter 6 on cut elimination even up the score?

To be continued

The post An Introduction to Proof Theory, Ch. 5. appeared first on Logic Matters.

A Introduction to Proof Theory, Ch. 5.

This chapter is on The Sequent Calculus. We meet Gentzen’s LJ and LK, with the antecedents and succedents taken to be sequences of formulas. It is mentioned that some alternative versions treat the sequent arrow as relating sets or multisets so the corresponding structural rules will be different; but it isn’t mentioned that alternative rules for the logical connectives are often proposed, making for some alternative sequent calculi with nice formal features. The definite article in the chapter title could mislead.

And how are we to interpret the sequent arrow? Taking the simplest case with a single formula on each side, we are initially told that A ⇒ B “has the meaning of A ⊃ B” (p. 169). But then later we are told that ”we might interpret such a sequent [as A ⇒ B] as the statement that B can be deduced from the assumption A” (p. 192, with letters changed). So which does it express? — a material conditional or a deducibility relation? I vote for saying that the sequent calculus is a regimented theory of deducibility!

Now, the conscientious reader of IPT will have just worked through over a hundred pages on natural deduction. So we might perhaps have expected to get next some nice linking sections explaining how we can see the sequent calculus as in a sense a development from natural deduction systems. I am thinking of the sort of discussion in the nice opening chapter ‘From Natural Deduction to Sequent Calculus’ of Jan von Plato and Sara Negri’s Structural Proof Theory (CUP, 2001). At the least, it would be good to ease the student in by starting with some natural deduction proofs and their sequent calculus analogues, to give a sense of how things work. But as it is, after setting up the calculus, IPT dives straight in to consider proof discovery by working back from the desired conclusion, with the attendant complications that arise from using sequences rather than sets or multisets. This messiness at the outset doesn’t seem well calculated to get a student to appreciate the beauty of the sequent calculus! However, the discussion does give some plausibility to the claim that provable sequents should be provable without cut.

Cut elimination is the topic of the next chapter. The rest of this present chapter goes through some more sequent proofs, and proves a couple of lemmas (e.g. one about variable replacement preserving proof correctness). And then there are ten laborious pages showing how an intuitionist natural deduction NJ proof can be systematically transformed into an LJ sequent proof, and vice versa.

The lack of much motivational chat at the beginning of the chapter combined with these extended and less-than-thrilling proofs at the end do, to my mind, make this a rather unbalanced menu for the beginner meeting the sequent calculus for the first time. At the moment, then, I suspect that many such readers will get more out of, and more enjoy, making a start on von Plato and Negri’s book. But does IPT’s Chapter 6 on cut elimination even up the score?

To be continued

The post A Introduction to Proof Theory, Ch. 5. appeared first on Logic Matters.

August 18, 2021

An Introduction to Proof Theory, Ch. 4

What are we to make of Chapter 4: Normal Deductions? This gives very detailed proofs of normalization, first for the ∧⊃¬∀ fragment of natural deduction, then for the intuitionist system, then for full classical natural deduction, with equally detailed proofs of the subformula property along the way. It all takes sixty seven(!!) pages, often numbingly dense. You wouldn’t thank me for trying to summarize the different stages, though I think things go along fairly conventional lines. I’ll just raise the question of who will really appreciate this kind of very extended treament?

It certainly is possible to introduce this material without mind-blowing tedium. For example, Jan von Plato’s very readable book Elements of Logical Reasoning (CUP 2013) gets across a rich helping of proof theoretic ideas at a reasonably introductory level with some zest, and has a rather nice balance between explanations of general motivations and proof-strategies on the one hand and proof-details on the other. An interested philosophy student with little background in logic who works through the book should come away with a decent initial sense of its topics, and will be able to appreciate e.g. Prawitz’s Natural Deduction. the more mathematical will then be in a position to tackle e.g. Troesltra and Schwichtenberg’s classic with some conceptual appreciation.

Mancosu, Galvan and Zach’s methodical coverage of normalization isn’t, I suppose, much harder than von Plato’s presentation (scattered sections of which appear at different stages of his book); it should therefore be accessible to those who have the patience to plod though the details of their Chapter 4 and who try not to lose sight of the wood for the trees. But I do wonder whether the slow grind here will really produce more understanding of the proof-ideas. I guess that I can recommend the chapter as a helpful supplement for someone who wants to chase up particular details (e.g. because they found some other, snappier, outline of normalization proofs hard to follow on some point). But is it this best place for most readers to make a first start on the topic? I have to say that I really rather doubt it.

To be continued

The post An Introduction to Proof Theory, Ch. 4 appeared first on Logic Matters.

August 17, 2021

An Introduction to Proof Theory, Ch. 3

Chapter 3 of IPT is on Natural Deduction. The main proof-theoretic work, on normalization, is the topic of the following chapter, and so the topics covered here are relatively elementary ones.

In particular, the first four sections of the chapter simply introduce Gentzen-style proof systems for minimal, intuitionist, and classical logic. So, as with most of the previous chapter, the main question about these sections is: just how good is the exposition?

One initial point. The book, recall, is aimed particularly at philosophy students with only a minimal background in mathematics and logic. But if they are reading this book at all, then — a pound to a penny — they will have done some introductory logic course. And it is quite likely that in this course they will already have met natural deduction done Fitch-style (indenting subproofs in the way expounded in no less than thirty different logic texts aimed at philosophers). It seems strange, to say the least, not to mention Fitch-style natural deduction at all; wouldn’t it have helped many readers to do a compare-and-contrast, explaining why (for proof-theoretic work) Gentzen-style tree layouts are customarily the standard?

An explicit comparison might, indeed, have helped in various places. For example, on p. 73 we are bluntly told that the inference from A to (B ⊃ A) is allowed by the conditional proof rule, i.e. vacuous discharge is allowed. No explanation is given to the neophyte of why this isn’t a cheat. A student familiar with conditional proof in a Fitch-style setting (where there is no requirement that the formula at the head of a subproof is essentially used in the derivation of the end-formula of the subproof) should have a head start in understanding what is going on in the Gentzen setting and why it might be thought unproblematic. Why not make the connection?

Next, it is worth saying that, while this chapter is about natural deduction proofs, there isn’t a single actual example of a proof set out! For the tree arrays which populate the chapter aren’t object language proofs, with formulas as assumptions and a formula as conclusion — they are all entirely schematic, with every featured expression a metalinguistic schema. Ok, this is pretty common practice; and wouldn’t be worth my remarking on if it was very clearly explained that this is what is happening. But it isn’t (I suppose a mis-stated single sentence back on p. 20 in the previous chapter is somehow supposed to do the job). And worse, our authors sometimes seem to themselves forget that everything is schematic. For example, at the foot of p. 79 an attempted proof schema is laid out, ending with the schema 𝐴(𝑐) ⊃ ∀𝑥𝐴(𝑥). This is followed by the comment “The end-formula of this ‘deduction’ is not valid, so it should not have a proof”. But the expression at the end of the proof schema isn’t a formula in the sense defined earlier in the chapter (i.e. it isn’t an object-language wff). And it is formulas, not schemas, that have natural deduction proofs according to the definition of a proof on p. 69. OK, so what is “the end-formula” here? — are they generalizing about all instances of the proof schema? Well, the end-formula of an instance of this attempted proof schema could perfectly well be valid. Ok, yes of course, it is easy to tidy this up so it says what is meant, along with a number of related mishaps: but the student reader shouldn’t be left having to do the work.

A third point. Oddly to my mind, the authors have decided to say nothing here about the supposed harmony between the core introduction and elimination rules shared by classical and intuitionist logic (there is just the briefest of mentions in the Preface of this as a topic that the reader might want to follow up). Well, I can certainly understand not wanting to get embroiled in the ramifying debates about the philosophical significance of harmony. But the relevant formal feature of the intuitionist system is so very neat that it is surely worth saying something about it, even when formal issues are at the forefront of attention. More generally — though I do realize this now is a rather unfocused grumble — I’d say that the expository §§3.1–3.4 don’t really bring out the elegance of Gentzen-style natural deduction.

Moving on to the rest of the chapter, §3.5 notes a couple of measures of the complexity of a deduction tree, and then the remaining two sections of the chapter look at a handful of results about deductions proved by induction on complexity. In particular, §3.7 shows that a formula is deducible in the axiomatic system for classical logic given in the previous chapter if and only if it is deducible in the classical natural deduction system described in this chapter. This bit of proof-theory is nicely done.

I’ve more quibbles that I’ll skip over. But overall, I would say that this chapter does fall somewhat short of my ideal of an introduction to Gentzen-style natural deduction. Still, students coming to it already knowing about Fitch-style proofs will surely be able to manage the transition and should get the hang of things pretty well. But I suspect that those who have never encountered a natural deduction system before might find it all significantly harder going.

To be continued

The post An Introduction to Proof Theory, Ch. 3 appeared first on Logic Matters.

August 16, 2021

An Introduction to Proof Theory, Ch. 2

IPT is particularly aimed at those “who have only a minimal background in mathematics and logic”. Well, philosophy students who haven’t done much logic may well not have encountered an old-school axiomatic presentation of logic before. So — perhaps reasonably enough — Chapter 2 is on Axiomatic Calculi. The chapter divides into two uneven parts, which I’ll take in turn.

In the early sections, we meet axiomatic versions of minimal, intuitionist and classical logic for propositional logic (presented using axiom schemas in the usual way). Next, after a pause to explain the idea of proofs by induction, there’s a proof of the deduction theorem, and an explanation of how to prove independence of axioms (more particularly, the independence of ex falso from minimal logic, and the independence of the double negation rule from intuitionist logic) using deviant “truth”-tables. Then we add axioms for predicate logic, and prove the deduction theorem again. So this part of the chapter is routine stuff. And really the only question is: how well does the exposition unfold?

By my lights, not very well. OK, perhaps the general state of the world is rather getting to me, and my mood is less than sunny. But I did find this disappointing stuff.

For a start, the treatment of schemas is a mess. It really won’t do to wobble between saying (p. 19) that axioms are formulas which are instances of schemas, and saying that such a formula is an instance of an axiom (p. 21). Or how about this: “an instance of an instance of an axiom is an axiom” (p. 21). This uses ‘axiom’ in two different senses (i.e. first meaning axiom schema) and then meaning axiom), and it uses ‘instance’ in two different senses (first meaning instance (of schema) and then meaning variant schema got by systematically replacing individual schematic letters by schemas for perhaps non-atomic wffs).

Or how about this? — We are told that a formula is a theorem just if it is the end-formula of a derivation (from no assumptions). We are immediately told, though, that “in general we will prove schematic theorems that go proxy for an infinite number of proofs of their instances.” (p. 20) You can guess what this is supposed to mean: but it isn’t what the sentence actually says. There’s more of the same sort of clumsiness.

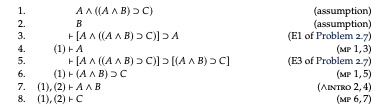

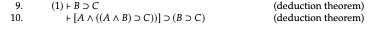

When it comes to laying out proofs, things again get messy. The following, for example, is described as a derivation (p. 32):

This is followed by the comment “Note that lines 1 and 2 do not have a ⊢ in front of them. They are assumptions, not theorems. We indicate on the left of the turnstile which assumptions a line makes use of. For instance, line 4 is proved from lines 1 and 3, but line 3 is a theorem — it does not use any assumptions.” But first, with this sort of Lemmon-esque layout, shouldn’t the initial lines have turnstiles after all? Shouldn’t the first line commence, after the line number, with “(1) ⊢” — since the assumption that the line makes use of is itself? And more seriously, in so far we can talk of line (9) as being derived from what’s gone before, it is the whole line read in effect as a sequent which is derived from line (8) read as a sequent — it’s not an individual formula derived from earlier ones by a rule of inference. So in fact this just isn’t a derivation any more in the original sense given in IPT in characterizing axiomatic derivations.

I could continue carping like this but it would get rather boring. However, a careful reader will find more to quibble about in these sections of the chapter, and — more seriously — a student coming to them fresh could far too easily be misled/confused.

The final long §2.15, I’m happy to say, is a rather different kettle of fish, standing somewhat apart from the rest of the chapter in both topic and level/quality of presentation. This section can be treated pretty much as a stand-alone introduction to classical and intuitionist first-order Peano Arithmetic (with an axiomatic logic), which then shows how to interpret the first in the second, thereby establishing that classical PA is consistent if the intuitionist version is. This is, I think, rather neatly done (though I suspect the discussion might need a slightly more sophisticated reader than what’s gone before).

Just one very minor comment. A student might wonder why what is here called the Gödel-Gentzen translation (atoms are left untouched) is different from what many other references call the Gödel-Gentzen translation (where atoms are double negated). A footnote of explanation might have been useful. But as I say, this twelve page section seems much better.

To be continued

The post An Introduction to Proof Theory, Ch. 2 appeared first on Logic Matters.

August 14, 2021

An Introduction to Proof Theory, Ch. 1

It’s arrived! Ever since it was announced, I’ve been very much looking forward to seeing this new book by Paolo Mancosu, Sergio Galvan and Richard Zach. As they note in their preface, most proof theory books are written at a fairly demanding level. So there is certainly a gap in the market for a book that presents some basic proof theory taking up themes from Gentzen in a more widely accessible way, covering e.g. proof normalization, cut-elimination, and a proof of the consistency of arithmetic using ordinal induction. An Introduction to Proof Theory (OUP, newly published) aims to be that book.

It’s arrived! Ever since it was announced, I’ve been very much looking forward to seeing this new book by Paolo Mancosu, Sergio Galvan and Richard Zach. As they note in their preface, most proof theory books are written at a fairly demanding level. So there is certainly a gap in the market for a book that presents some basic proof theory taking up themes from Gentzen in a more widely accessible way, covering e.g. proof normalization, cut-elimination, and a proof of the consistency of arithmetic using ordinal induction. An Introduction to Proof Theory (OUP, newly published) aims to be that book.

Back in the day, when I’d finished my Gödel book, I had it in mind for a while to write a Gentzen book a bit like IPT (as I’ll refer to it) though a couple of notches more technical. But when I got down to work, I quickly realized that my grip on the area was really quite embarrassingly shallow in places, and I lost all confidence. What I should have done was downsize my ambitions and tried instead to write a book more like this present one. So I have a particular personal interest in seeing how Mancosu, Galvan and Zach write up their project. I’m cheering them on!

Some brisk notes, then, as I read through …

Chapter 1: Introduction has three brisk sections, on ‘Hilbert’s consistency program’, ‘Gentzen’s proof theory’ and ‘Proof theory after Gentzen’.

The scene-setting here is done very cogently and reliably as far as it goes (just as you’d expect). However, on balance I do think that — given the intended readership — the first section in particular could have gone rather more slowly. Hilbert’s program really was a great idea, and a bit more could have been said to explore and illuminate its attractions. On the other hand, an expanded version of the third section would probably have sat more naturally as a short valedictory chapter at the end of the book.

But then, one thing I’ve learnt from writing my own introductory books is that you aren’t going to satisfy everyone — indeed, probably not even a majority of your hoped-for readers will be happy. Wherever you set the dial, many will complain that you take things at far too slow a pace, while others will complain that you lost them only a few chapters in. So, in particular, these questions of how much initial scene-setting to provide are very much a judgement call.

To be continued (and I’ll return to The Many and the One in due course).

The post An Introduction to Proof Theory, Ch. 1 appeared first on Logic Matters.

August 10, 2021

The Chiaroscuro Quartet play Schubert’s Rosamunde

I hadn’t noticed before that there is a video of the Chiaroscuro Quartet playing Schubert’s Rosamunde Quartet from a concert in Gstaad a couple of years ago. Their earlier CD including this piece is wonderful, it goes without saying, but it is terrific to be able to watch them playing in a live performance. (To see the whole recording, you need to register, for free, for the Gstaad Digital Festival.)

The post The Chiaroscuro Quartet play Schubert’s Rosamunde appeared first on Logic Matters.

August 8, 2021

The Many and the One, Ch. 5 & Ch. 6

I confess that I have never been able to work up much enthusiasm for mereology. And Florio and Linnebo’s Chapter 5, in which they compare ‘Plurals and Mereology’, doesn’t come near to persuading me that there is anything of very serious interest here for logicians. I’m therefore quite cheerfully going to allow myself to ignore it here. So let’s move on to Chapter 6, ‘Plurals and Second-Order Logic’. The broad topic is a familiar one ever since Boolos’s classic papers of — ye gods! — almost forty years ago: though oddly enough F&L do not directly discuss Boolos’s arguments here.

In §6.1, F&L give a sketchy account of first-order logic, and then highlight its monadic fragment. Note, they treat the second-order quantifiers as ranging over Fregean concepts. And they perhaps really should have said more about this — for can the intended reader be relied on to have a secure grasp on Frege’s notion? Indeed, what is a Fregean concept?

The following point seems relevant to F&L’s project. According to Michael Dummett’s classic discussion (in his Frege, Philosophy of Language, Ch. 7), Fregean concepts are extensional items: while (for type reasons) we shouldn’t say that co-extensive concepts are identical, the relation which is analogous to identity is indeed being coextensive. So the concept expressions ‘… is a creature with a heart’ and ‘… is a creature with a kidney’ have the same Fregean concept as Bedeutung. I take it that Dummett’s account is still a standard one (the standard one?). For example, I note that Michael Potter in his very lucid Introduction to the Cambridge Companion to Frege — while noting Frege’s reluctance to talk of identity in this context — writes (without further comment)

Concepts, for Frege, are extensional, so that, for instance, the predicates ‘x is a round square’ and ‘x is a golden mountain’ refer to the same concept (namely the empty one).

But now compare F&L. They write

Two coextensive concepts might be discerned by modal properties. Assume, for example, that being a creature with a heart and being a creature with a kidney are coextensive. Even so, these two [sic] concepts can be discerned by a modal property such as possibly being instantiated by something that lacks a heart.

Which seems to suggest that, contra Dummett and Potter’s Frege, co-extensive predicates can have distinct concepts as Bedeutungen. That’s why I really do want more elaboration from F&L of their story about the Fregean concepts which, according to them, feature in an account of second-order quantification.

§6.2 notes how plural logic and monadic second order logic can be intertranslated (with minor wrinkles). And, analogously to §4.3, a question then arises: can we eliminate pluralities in favour of concepts, or vice versa?

So §6.3 discusses the possibility of using second-order language to eliminate first-order plural terms, as once suggested by Dummett. As F&L note, this suggestion has already come in for a lot of criticism in the literature; but they argue that there is some wriggle room for defenders of (something like) Dummett’s line to avoid the arguments of e.g. Oliver and Smiley and others. I’m not really convinced. For example, F&L suggest that a manoeuvre invoking events proposed by Higginbotham and Schein will help the cause — simply ignoring the extended critique of the manoeuvre already in Oliver and Smiley’s Plural Logic. In the end, though, F&L think that there is a pretty compelling argument against the elimination of pluralities in favour of concepts on the basis of their respective modal behaviour (but note, F&L are here seemingly relying on their departure from the standard Dummettian construal of Fregean concepts — or if not, we need to hear more).

§6.4 then looks at the possibility of an elimination going the other way, reducing second-order logic to a logic of plurality. But so far we have only been offered a way of translating monadic second order logic using plurals; the obvious first question is — how can we translate full second-order logic with polyadic predicates, quantifying over polyadic concepts? Perhaps we can do the trick if we help ourselves to a pairing function for the first-order domain (so, for example, dyadic relations get traded in for monadic properties of pairs). F&L raise this familiar idea: but suggest — again very briefly — that there is another modal objection: “while a plurality of ordered pairs can model the extension of a dyadic relation, it cannot in general represent all of its intensional features.” Tell us more! We also get a promissory note forward to discussion of a different objection to eliminating second-order logic.

There’s a short summary §6.5. But, to my mind, this is again a somewhat disappointing chapter. As it happens, my inclinations are with F&L’s conclusion that both plural logic and second order logic can earn their keep (without one being reduced to the other). But I do rather doubt that anyone who already takes a different line will find themselves compelled to change their minds by the arguments outlined here.

To be continued, but after a break.

The post The Many and the One, Ch. 5 & Ch. 6 appeared first on Logic Matters.

August 6, 2021

The Many and the One, Ch. 4

In the next part of their book, ‘Comparisons’, F&L discuss ‘Plurals and Set Theory’ (Chapter 4) and ‘Plurals and Second-order Logic’ (Chapter 6). In between, they also compare ‘Plurals and Mereology’ (Chapter 5). But I confess that I have never been able to work up much enthusiasm for mereology, and F&L’s chapter doesn’t come near to persuading me that there is anything of very serious interest here for logicians; so I’m cheerfully going to allow myself to ignore it.

Here, in bald outline, is what happens in Chapter 4. §4.1 describes a ‘simple set theory’ framed in a two-sorted first-order language, with small-x quantifiers running over a domain of individuals and big-X quantifiers running over sets of those individuals. The two sorts are linked by an axiom scheme of set comprehension, (S-Comp): ∃X∀x(x ∈ X  φ(x)). §4.2 notes that the mutual interpretability of this theory with a simple plural logic. (We can’t just replace big-X set variables by double-x plural variables — we need to work around the usual assumption that there is an empty set in the range of big-X variables but not an empty plurality in the range of double-x plural variables. But that’s minor tinkering.) §4.3 then asks whether this mutual interpretability means we should eliminate plurals in favour of sets or sets in favour of plurals. §4.4 suggests that we need plurals in elucidating the very notion of a set (so don’t eliminate plurals): the root idea is that “For every plurality of objects xx from [a given domain], we postulate their set {xx},” where postulation seems to be tantamount to defining into existence. We are promised more about definitions of this kind in Chapter 12.

φ(x)). §4.2 notes that the mutual interpretability of this theory with a simple plural logic. (We can’t just replace big-X set variables by double-x plural variables — we need to work around the usual assumption that there is an empty set in the range of big-X variables but not an empty plurality in the range of double-x plural variables. But that’s minor tinkering.) §4.3 then asks whether this mutual interpretability means we should eliminate plurals in favour of sets or sets in favour of plurals. §4.4 suggests that we need plurals in elucidating the very notion of a set (so don’t eliminate plurals): the root idea is that “For every plurality of objects xx from [a given domain], we postulate their set {xx},” where postulation seems to be tantamount to defining into existence. We are promised more about definitions of this kind in Chapter 12.

§4.5 then notes that mathematical uses of sets crucially involve not just sets of individuals (numbers, perhaps) but sets of sets, sets of sets of sets. etc.; and, for a start, it is very unclear that these can be eliminated in favour of pluralities of pluralities. §4.6 then says more about the iterative conception of set, and §4.7 gives the axioms of ZFC. §4.8 jumps on to wonder whether we can use plurals in explicating the notion of proper classes. The chapter ends with §4.9 which raises a problem:

We have described two very attractive applications of plural logic: as a way of giving an account of sets, and as a way of obtaining proper classes “for free”. Regrettably, it looks like the two applications are incompatible. The first application suggests that any plurality forms a set. Consider any objects xx. Presumably, these are what Gödel calls “well-defined objects”. If so, it is permissible to apply the “set of” operation to xx, which yields the corresponding set {xx}. The second application, however, requires that

there be pluralities corresponding to proper classes, which by definition are collections too big to form sets.

F&L again promise to return to deal with this apparent tension in their Chapter 12.

Does the chapter work? Well, it is pretty difficult to know quite at whom it is aimed. For example, §4.6 very briskly outlines the iterative conception of set, helping itself along the way to the idea that we take unions at levels indexed by limit ordinals (where ordinals are unexplained). But I wonder who is supposed to (a) already be familiar with the notion of a limit ordinal in §4.6, but (b) still need to have the axioms of ZFC given again in §4.7? And won’t the reader who needs §4.7 need more explanation of the role of proper classes in set theory (and the difference between their appearance as virtual classes in e.g. Kunen, versus a more substantive appearance in NBG)?

And to go back to the beginning of the chapter, I would guess that someone with enough logical education to know about limit ordinals would also know enough to want to ask more about the principle S-Comp: does the comprehension principle apply to predicates φ(x) which themselves involve bound set variables? or involve free set variables as parameters? or neither? We are not told, and there is no hint that the issue might matter. And there is no hint at all that the kind of “simple set theory” with two sorts of quantifier might actually be of real interest, e.g. in reverse mathematics when considering subsystems of second-order arithmetic. This lack of development is typical.

As it happens, I am in sympathy with F&L’s overall line that (i) plural logic is repectable and can earn its keep in certain important contexts, and (ii) set theory is just fine in its place too! But I can’t see that this arm-waving chapter really advances the case for either limb (and I could nag away more at some of the details). In so far as there are hints of novel argumentative moves, the work of elaborating them is left for much later. So I did find this chapter frustratingly rather superficial.

To be continued.

The post The Many and the One, Ch. 4 appeared first on Logic Matters.