Allyson Newburg's Blog, page 6

April 12, 2020

April 12, 1945 - The Onward March to Stalag Luft VIIA

The group of prisoners, including Gerard Kelleher and David Yemen would leave Stalag Luft XIIID near Nuremburg today, continuing the march to Stalag VIIA. learning of the death of US President Roosevelt along the way.

Yet again, the timing would prove unlucky for Kelleher and Yemen as they would find themselves just missing the U.S. Army again. By the time the US Army marched into Stalag Luft XIIID four days later, Kelleher, Yemen and their fellow evacuees were already well on their way to the next camp. The only airmen still at Stalag Luft XIIID were approximately 13,000 quarantined POWs with typhoid fever.

For the marchers, food rations on the march towards Stalag Luft VIIA in Moosburg included a combination of whatever was left over from their Red Cross rations and anything the POWs and their German guards were able to scrounge along the way.

Yet again, the timing would prove unlucky for Kelleher and Yemen as they would find themselves just missing the U.S. Army again. By the time the US Army marched into Stalag Luft XIIID four days later, Kelleher, Yemen and their fellow evacuees were already well on their way to the next camp. The only airmen still at Stalag Luft XIIID were approximately 13,000 quarantined POWs with typhoid fever.

For the marchers, food rations on the march towards Stalag Luft VIIA in Moosburg included a combination of whatever was left over from their Red Cross rations and anything the POWs and their German guards were able to scrounge along the way.

Published on April 12, 2020 07:00

April 11, 2020

The Caterpillar Club

The Irving Air Chute Company Caterpillar Club pin

The Irving Air Chute Company Caterpillar Club pinSource: airborne-sys.com/2018/11/19/the-caterpillar-club/

While recovering from his burns at the Canadian Wing of the Queen Victoria Hospital in East Grinstead, Douglas Hicks would write a letter to Irving Air Chute, formally applying for membership to the Caterpillar Club, a club to which the surviving members of the Harris Crew were fully qualified. The Irvine Air Chute Company started the Caterpillar Club in 1922, and began awarding certificates and gold caterpillar pins to anyone whose life was saved by parachuting from a disabled aircraft. The caterpillar symbolizes the silk worm, since parachutes were originally made from this material. According to Irving’s website:

"One evening in 1922, two airmen, Lieutenant Harold R. Harris and Lieutenant Frank B. Tyndal met Leslie Irvin at McCook Field (near the site of Wright-Patterson AFB) to have drinks and share stories about lives saved by parachutes. One of the airmen said “We ought to start a club for guys like us. As time goes by more and more fliers all over the world will owe their lives to your chutes, it should be quite a thing in years to come.” And that was how the Caterpillar Club, an exclusive club for those who had their lives saved by a parachute, was formed."

During World War II, Irvin Air Chute’s factory in Letchworth, England, was producing nearly 1,500 parachutes per week. By late 1945, there were 34,000 members of the Caterpillar Club.

Three weeks later, Hicks received his acceptance letter, membership card and his caterpillar pin at the hospital.

Irvin Aerospace Limited, as the company is now called, has maintained the club records. Replacement certificates and/or pins may be requested by immediate family members by contacting:

IrvinGQ (AFPSU)Blackhorse Road, Letchworth Garden City, Herts, SG6 1HDTel: +44 (0) 1462 480433

Published on April 11, 2020 07:00

April 10, 2020

April 10, 1945 - Kelleher and Yemen Arrive at Stalag Luft XIIID

With the Allied and Russian forces advancing into Germany, Dulag Luft, the transit camp for Allied airmen, began the evacuation of prisoners on March 20th. The following week, on March 27th, a second group of prisoners, including Gerard Kelleher and David Yemen departed Dulag Luft for the 250 km march to Stalag Luft XIIID near Nuremburg.

This group of evacuees, including Kelleher and Yemen, arrived at the now-defunct Stalag Luft XIIID on or about April 10th after a 15-day journey.

This group of evacuees, including Kelleher and Yemen, arrived at the now-defunct Stalag Luft XIIID on or about April 10th after a 15-day journey.

Published on April 10, 2020 07:00

April 9, 2020

April 9, 1945 - The Youngest Guinea Pig

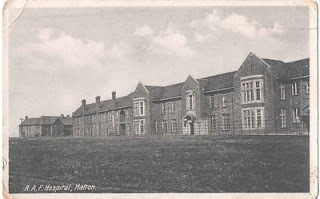

After five days at the RAF Hospital in Halton, Douglas Hicks received his travel orders and on April 9th, was again on the move by train and bus, this time to the Canadian Wing of the Queen Victoria Hospital in East Grinstead, England for the treatment of burns he sustained during the Dessau raid. At nineteen years of age, Hicks was to become the youngest member of the Guinea Pig Club, the club for burned Allied airmen.

Hicks described his awkward journey to East Grinstead:

With new orders I am now on the way to a hospital south of London. I ride the bus to the railway station at Kings Cross. I must now work my way to the other side of London to catch a train to East Grinstead. East Grinstead is south of London, the location of the Queen Victoria Hospital. This hospital specializes in the treatment of burned military personnel.

My dress should arouse suspicion not only from any [military police] but from any of the civilians that I might encounter. But it does not. My uniform now consists of a blue battle dress jacket with my air gunners wing and sergeant stripes, my shirt is khaki in color and is U.S. Army issue, my boots, also U.S. Army issue, are the brown boots worn by the paratroopers, of course let’s not forget my head, because of my burns I am still wearing the white paper bandage as applied by the German hospital staff. It is now looking very grubby. If was decided at the RAF station [Halton] that it should stay in place until I am able to get further hospital attention at my destination, finally my hair, it desperately need not only washing but a good combing.

On arrival, one of Hicks’ first requests was for a hot bath. After a superficial check by Dr. Tilley, it was determined no immediate treatment would be necessary for his burns.

Hicks’ next order of business catch up on letters. The first would be a short note to his mother but another would be far more difficult to write. Writing to the mother of the mid-upper air gunner Eric Robinson, one of the three killed on the raid to Dessau, Hicks remembered: “I apologized for being a survivor, and although the letter was very short I did attempt to convey sympathies which would run with and play with my mind for a long time.”

Hicks described his awkward journey to East Grinstead:

With new orders I am now on the way to a hospital south of London. I ride the bus to the railway station at Kings Cross. I must now work my way to the other side of London to catch a train to East Grinstead. East Grinstead is south of London, the location of the Queen Victoria Hospital. This hospital specializes in the treatment of burned military personnel.

My dress should arouse suspicion not only from any [military police] but from any of the civilians that I might encounter. But it does not. My uniform now consists of a blue battle dress jacket with my air gunners wing and sergeant stripes, my shirt is khaki in color and is U.S. Army issue, my boots, also U.S. Army issue, are the brown boots worn by the paratroopers, of course let’s not forget my head, because of my burns I am still wearing the white paper bandage as applied by the German hospital staff. It is now looking very grubby. If was decided at the RAF station [Halton] that it should stay in place until I am able to get further hospital attention at my destination, finally my hair, it desperately need not only washing but a good combing.

On arrival, one of Hicks’ first requests was for a hot bath. After a superficial check by Dr. Tilley, it was determined no immediate treatment would be necessary for his burns.

Hicks’ next order of business catch up on letters. The first would be a short note to his mother but another would be far more difficult to write. Writing to the mother of the mid-upper air gunner Eric Robinson, one of the three killed on the raid to Dessau, Hicks remembered: “I apologized for being a survivor, and although the letter was very short I did attempt to convey sympathies which would run with and play with my mind for a long time.”

Published on April 09, 2020 07:00

April 8, 2020

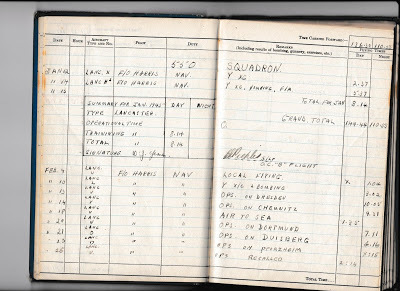

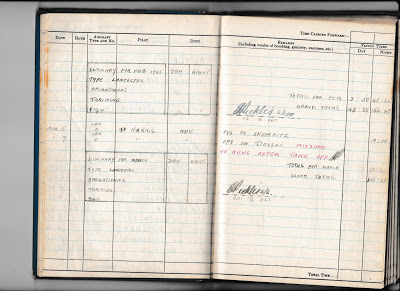

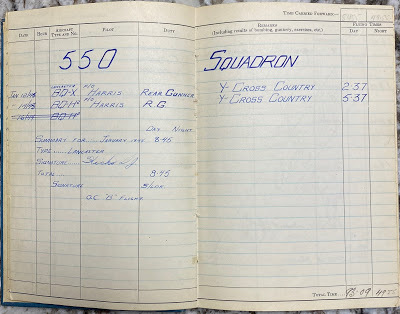

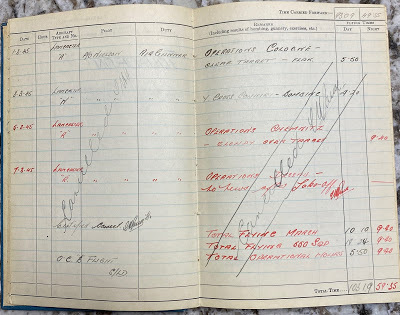

Flight Logs - David Yemen

Published on April 08, 2020 07:00

April 7, 2020

Flight Logs - Gordon Nicol

Published on April 07, 2020 07:00

April 6, 2020

The incredible story of The Harris Crew will soon be available in trade paperback!

Published on April 06, 2020 07:00

April 5, 2020

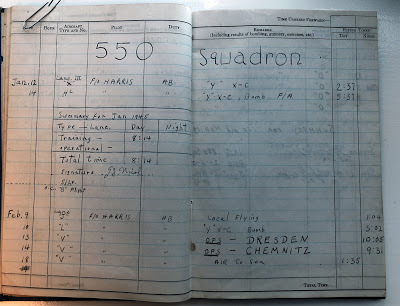

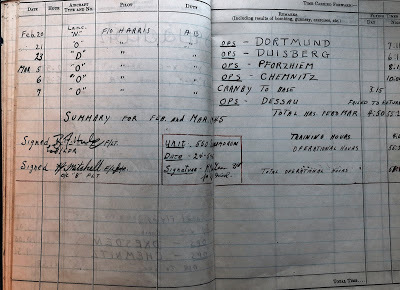

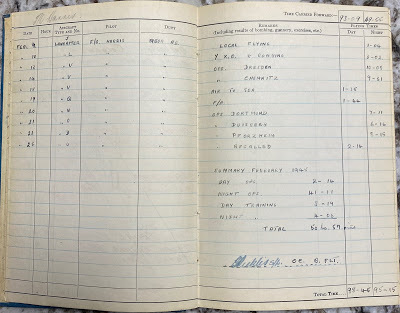

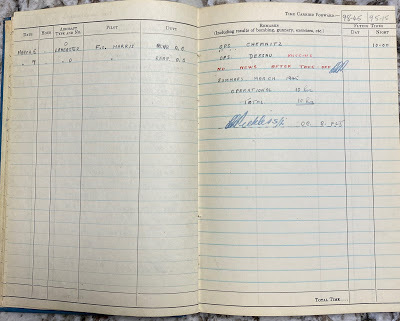

Flight Logs - Douglas Hicks

It is unclear why in Hicks' flight logs (courtesy the Hicks family) a page of March 1945 operations appears on the page prior to February, and stranger still that they are crossed out. There is no record of Hicks having ever flown with Nielson’s crew.

Log discrepancies were not uncommon, particularly since crew did not bring their logs with them on flights and the information contained within them usually came second or third-hand to whatever administrator was completing them on any given day. In some cases, log books were completed after-the-fact by airmen taking details from Squadron records which may or may not have been accurate. It is likely the book was mixed up with a Nielson Crew member as the result of a clerical error.

Published on April 05, 2020 07:00

April 4, 2020

April 4, 1945 - Hicks Arrives at the RAF Hospital in Halton

Now liberated from Dulag Luft POW transit camp at Wetzlar, Douglas Hicks and Gordon Nicol were evacuated by air back to England.

Now liberated from Dulag Luft POW transit camp at Wetzlar, Douglas Hicks and Gordon Nicol were evacuated by air back to England.As arrangements were made to repatriate Nicol back to Canada, Hicks was now admitted to the RAF Hospital in Halton to have his burns and other facial injuries properly tended to.

Published on April 04, 2020 07:00

April 3, 2020

April 3, 1945 - Evacuations from Wetzlar Begin

Colonel Stark, having left Wetzlar on March 31, arrived in Paris on April 3, 1945 to complain to the US Air Force Lieutenant General about the timelines for evacuating the camp. Quesada had Wetzlar air-evacuated within hours of their meeting.

Douglas Hicks, Gordon Nicol and the other liberated prisoners from Dulag Luft would be flown back to England aboard DC-3s from the nearby airfield. Hicks described the warm welcome he and the other former POWs would receive on arrival at RAF Cosford, the RAF reception and rehabilitation centre for returning prisoners of war:

En route to England we fly over the city of Cologne. I can see the devastation in the city. After crossing the Rhine, I really feel liberated. We land at an English fighter station in the south of England. The complete station staff is on hand to greet us. The station has gone to great lengths to make our arrival something to remember. They have baked cupcakes and many other types of goodies. There is a hand-lettered sign welcoming us back to England.

After a short debriefing I am allowed to send a telegram home to my mother. This is foremost in my mind, as the worrying at home can now stop. I also make a local phone call [to Mary Burton, the fiancé of Navigator David Yemen]. When I called her, she was more than elated. I could only tell her that her [fiancé], when last seen, was in good health. I also brought her up to date on the disposition of the rest of the crew. She had, on her own volition, obtained all the names and home addresses of the crew and had been in contact with all of the families. It was very difficult to tell her the names of our crew who did not make it. No doubt the burden of informing the rest of the crew families weighed heavily on her shoulders.

While it was a time of relief for Hicks and Nicol, crewmates Gerard Kelleher and David Yemen were still marching south towards Stalag Luft XIIID near Nuremburg. For Kelleher and Yemen, their liberation was still a month away.

Douglas Hicks, Gordon Nicol and the other liberated prisoners from Dulag Luft would be flown back to England aboard DC-3s from the nearby airfield. Hicks described the warm welcome he and the other former POWs would receive on arrival at RAF Cosford, the RAF reception and rehabilitation centre for returning prisoners of war:

En route to England we fly over the city of Cologne. I can see the devastation in the city. After crossing the Rhine, I really feel liberated. We land at an English fighter station in the south of England. The complete station staff is on hand to greet us. The station has gone to great lengths to make our arrival something to remember. They have baked cupcakes and many other types of goodies. There is a hand-lettered sign welcoming us back to England.

After a short debriefing I am allowed to send a telegram home to my mother. This is foremost in my mind, as the worrying at home can now stop. I also make a local phone call [to Mary Burton, the fiancé of Navigator David Yemen]. When I called her, she was more than elated. I could only tell her that her [fiancé], when last seen, was in good health. I also brought her up to date on the disposition of the rest of the crew. She had, on her own volition, obtained all the names and home addresses of the crew and had been in contact with all of the families. It was very difficult to tell her the names of our crew who did not make it. No doubt the burden of informing the rest of the crew families weighed heavily on her shoulders.

While it was a time of relief for Hicks and Nicol, crewmates Gerard Kelleher and David Yemen were still marching south towards Stalag Luft XIIID near Nuremburg. For Kelleher and Yemen, their liberation was still a month away.

Published on April 03, 2020 07:00