Alex Kakuyo's Blog, page 7

May 31, 2020

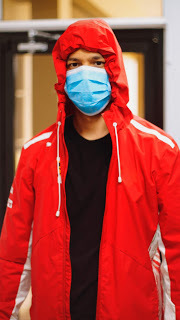

How to Be a Buddhist Protester

On Monday, May 25th, George Floyd died after a police officer held his knee on the back of his neck for more than 8 minutes. Floyd was handcuffed at the time, and he was simultaneously being restrained by several other officers.

On Monday, May 25th, George Floyd died after a police officer held his knee on the back of his neck for more than 8 minutes. Floyd was handcuffed at the time, and he was simultaneously being restrained by several other officers.In the days after his death, protests have erupted in 17 states; resulting in mass arrests, property damage, and calls for peace from local officials. In the wake of these events, many Buddhists are struggling with how to respond.

The truth of the matter is protests ar...

Published on May 31, 2020 11:42

May 3, 2020

Stripping Buddhism of Cultural Baggage

Cultural Baggage is a term that comes up a lot in Western Buddhism. Generally, it's used in reference to any part of the practice that can be traced to a specific geographic region in the world.

Cultural Baggage is a term that comes up a lot in Western Buddhism. Generally, it's used in reference to any part of the practice that can be traced to a specific geographic region in the world.The implication is that there is a pure Buddhism lying underneath all of the traditions and philosophies that flavor Buddhism as it's practiced in different areas.

Some things that are commonly referred to as cultural baggage include bowing, chanting, wearing robes, making offerings, and...

Published on May 03, 2020 10:39

April 26, 2020

Breaking the Cycle of Codependency

Codependency describes a relationship where one party depends entirely on another for feelings of self-worth or validation.

Codependency describes a relationship where one party depends entirely on another for feelings of self-worth or validation.The relationship is generally one-sided with one party either exerting an unhealthy amount of control over the other (e.g. you don't leave the house unless I tell you) or enabling unhealthy behaviors in exchange for affection (e.g. I know he'll use the money for drugs, but he'll leave me if I don't let him have it).

People can also engage in codependent relationships with objects and organizations. For example, if someone is codependent with money, basing their self-worth on how much or little they have, their mood will vary wildly depending on the contents of their bank account.

Similarly, if someone is codependent with their job, depending on it for their sense of identity, they may stay in an abusive or unfulfilling work environment because the thought of leaving is scarier than the thought of being mistreated.

Some of the signs of a codependent relationship are as follows:

Not trusting ourself to make decisions without someone else's approvalFeelings that everyone else's needs are more important than our ownAttempting to control the actions of other people for their own goodWanting to feel intimacy with other people and feeling threatened if they get too closeFeeling threatened if other people's opinions don't align with our own

Most of us show signs codependence in one or more areas of our life. Maybe we use romantic relationships to boost our self-esteem. Maybe we use money or status to build an identity that people will like. Or maybe we try to control the thoughts and actions of others to protect our sense of self.

Thankfully, Buddhist practice offers a teaching that helps us break the cycle of codependency. It's called Hongaku.

Hongaku is a Japanese word that translates to original enlightenment. The essential premise is that all sentient beings are manifestations of the Dharmakaya, so they are by their very nature enlightened. Thus, the practice of Buddhism is less about attaining something new and more about refining and purifying what's already there.

One way to understand hongaku is to contemplate the nature of waves on the ocean. The ocean is made of water, so the waves are also made of water. Humans manifest from the Dharmakaya, which is the primordial source of enlightenment, so they are by their nature enlightened.

Thus, it would be correct to say that humans are inherently enlightened. However, this requires further explanation as humans do not possess a separate, permanently-abiding self. Simply put, water has an inherent nature, possessing two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom. However, it constantly changes states; shifting between liquid, solid, and gaseous forms.

Similarly, humans possess an inherently enlightened nature, however, that doesn't stop us from changing states; shifting between birth, aging, sickness, and then death

One question that needs to be answered, however, before we can understand hongaku is, "If humans are inherently enlightened, why do we do bad things?" This is a fair question, and to understand that we can look at the example of gold.

Gold is a valuable resource, which has both entertainment and industrial uses. And it's been used as a medium of exchange for thousands of years. However, gold isn't useful the moment it comes out of the ground. Generally, it has a number of impurities (silver, lead, copper, etc.) that must be removed before it can be sold.

Similarly, humans have an enlightened nature, but we have a number of impurities in the way of greed, anger, and ignorance that must be removed before that enlightenment can be realized and manifested in daily life.

Buddhism serves as the refinement process that purifies our body, speech, and mind. In the absence of spiritual practice, however, our greed, anger, and ignorance cause us to do foolish things.

That being said, we don't need to fully realize our original enlightenment to break the cycle of codependency. We just need to know that it's there. Because the understanding of our inherent enlightenment naturally leads to a feeling of inherent self-worth;

Self-worth is what allows us to break the cycle of codependency. When we rest comfortably in the knowledge of our own enlightenment, we stop looking outside ourselves for validation. If someone mistreats us, we're able to stand-up for ourselves or break off the relationship because we're okay with the thought of being alone.

We don't feel the need to control others, because our sense of self isn't based on their actions. And our relationship with jobs, money, success, etc. becomes healthier because we don't use those things to measure our self-worth.

Thus, hongaku allows us to move through the world without getting dragged down by the fears, anxieties, and hurtful actions of others. It creates a safe space within ourselves that becomes a refuge when life is hard. And it helps us develop healthy relationships that are free from codependency.

Namu Amida Butsu

Get my new book, Perfectly Ordinary: Buddhist Teachings for Everyday Life

Click here to read a sample chapter of the book

Visit my YouTube channel to hear Dharma Talks

If you'd like to support my work, please consider making a donation

Breaking the Cycle of Codependency

Published on April 26, 2020 10:22

April 17, 2020

Wabi Sabi Flowers and Buddhist Practice

Part of my routine is going for daily walks. My body responds well to the dose of fresh air after being inside all day and I enjoy stretching my legs.

Part of my routine is going for daily walks. My body responds well to the dose of fresh air after being inside all day and I enjoy stretching my legs.Recently, I was walking through a park near my home on a cold, cloudy day. I'd been walking for a long while, and the wind was starting to find it's way inside my coat, freezing my skin. I was about to turn around and head home when a yellow blur caught my eye. When I moved closer to investigate, I saw that it was a daffodil.

The flower swayed violently in the wind and the ground around it was bare except for a few stray pieces of mulch. But that didn't stop the daffodil from blooming with everything that it had. The bright yellow of its petals glowed in contrast to the gray, dreariness of the day. And I stared at it, spellbound for several minutes.

As I looked at the flower, I was filled with melancholy. Part of me was happy that I could see it, but the other part was sad that no one could see it with me.

The weather was getting worse. And the chances of someone else walking through the park before the wind tore the flower from its roots were slim.

But there was nothing that I could do. So, I placed my hands in gassho, bowed deeply to the flower, and walked home. In Japanese, there's a word for what I experienced in the park. It's called wabi-sabi, which literally translates to "lonely desolation".

That sounds terrible. no one wants to spend an evening in lonely desolation. However, wabi-sabi is generally used to describe objects of great beauty or skill. For example, a tea ceremony, a Zen garden, or a flower arrangement could all be used to express wabi-sabi. Thus, a less literal, more artistic translation of the word would be "beauty in the midst of suffering."

Simply put, flowers die, economies crash, and sometimes we must struggle to survive. But the practice of wabi-sabi is learning to be joyful in the midst of struggle. It's learning to be beautiful simply because we can.

One way to express this beauty in daily life is through the Buddhist practice of gratitude. This is different from what people normally consider gratitude because it's free of conditions. We're thankful for the things that cause us happiness. But we're also thankful for things that make us suffer.

For example, we can wash the dishes because our partner will be angry if we don't, that's fine. But there's a certain joy that emerges if we wash them with a sense of gratitude for the meal we just enjoyed.

We can pay bills and be upset about the money leaving our bank account, that's fine. But our lives are more pleasant if we pay bills with a sense of gratitude for the heat, electricity, cable, etc. that we get to enjoy for another month.

It's a subtle shift in mindset. In fact, most people won't even notice what we're doing. But that slight change represents the difference between victory and defeat, between experiencing heaven or suffering through hell in daily life

If we can learn to be thankful when doing unpleasant things, if we can practice gratitude in the midst of suffering, then our lives will be easier. We'll embody the teaching of wabi-sabi. And like a flower that grows in a cold, empty park, we'll learn to be happy simply because we exist.

Namu Amida Butsu

Get my new book, Perfectly Ordinary: Buddhist Teachings for Everyday Life

Click here to read a sample chapter of the book

Visit my YouTube channel to hear Dharma Talks

If you'd like to support my work, please consider making a donation

Wabi Sabi Flowers and Buddhist Practice

Published on April 17, 2020 20:52

April 5, 2020

Buddha Warned Us About Coronavirus (Covid-19). We Should Have Listened.

In the Vimalakirti sutra, we're told the story of a lay Buddhist teacher by the name of Vimalakirti who is on his death bed. Buddha, in his wisdom, sends one of his attendants to Vimalakirti's hut to find out what's happened.

In the Vimalakirti sutra, we're told the story of a lay Buddhist teacher by the name of Vimalakirti who is on his death bed. Buddha, in his wisdom, sends one of his attendants to Vimalakirti's hut to find out what's happened.When he arrives at the hut the young man is greeted by countless gods, devas, and demons who've come to pay their respects.

When the attendant asked Vimalakirti why he was ill, the old man replied, "I am sick because the world is sick."

With that one statement, he summed up the whole of the human condition. When our neighbors are healthy and happy, we naturally get healthier and happier. Similarly, when our neighbors are sick, we suffer with them. Thus, we exist simultaneously as individuals and as parts of a much larger whole.

To put it another way, Vimalakirti used his final teaching to remind us that when we care for others, we care for ourselves. Unfortunately, this is a lesson that we're still struggling to learn. Case in point, the Covid-19 pandemic started in Wuhan, China. We heard about it, we saw the death toll rising, and we all went back to our daily lives.

The pandemic was "their" problem, and it had nothing to do with "us". Due to our apathy, it spread quickly to the Middle East, Europe, and finally the United States. At the time of this writing, 300,000 Americans have been infected with the virus, and Governor Cuomo of New York is fearful that his state will run out of ventilators for patients who develop respiratory problems as a result.

Like Vimalakirti, we are sick because the world is sick, and this won't be the last time this happens. In a world where products and people travel across continents in a matter of hours, we can't ignore the oneness of all things. We can't simply look at our own portion of the map, and ignore the suffering that happens around us.

Because the world's suffering is only one airplane ride away from entering our living room.

In this sutra, Buddha warned us what happens when we turn a blind eye to our neighbor. And in this moment of crisis, we have the chance to finally learn our lesson. Through our actions, we can adapt Vimalakirti's statement to say, "I am well because the world is well."

We can reach out to the stranger and ask, "What do you need?" We can look at the sick and ask, "How can I help?" And we can build a society that reflects the deep interconnectedness of all living things; a society that cares not for differences of race, country, or religion. Because in our suffering we are all one.

I am sick because the world is sick. I hope those words are etched in our hearts by the time this pandemic is over. If not, we'll quickly return to this sad state of affairs.

Namu Amida Butsu

Get my new book, Perfectly Ordinary: Buddhist Teachings for Everyday Life

Click here to read a sample chapter of the book

Visit my YouTube channel to hear Dharma Talks

If you'd like to support my work, please consider making a donation

Buddha Warned Us About the Coronavirus (Covid-19) Pandemic. We should have listened

Published on April 05, 2020 21:02

March 21, 2020

Don't Be Scared of Coronavirus. We Were Built for This

When people think of Buddhist practice, a variety of images appear. Sometimes, they picture a woman with perfectly manicured nails; sitting on the beach in full-lotus position.

When people think of Buddhist practice, a variety of images appear. Sometimes, they picture a woman with perfectly manicured nails; sitting on the beach in full-lotus position.Other times, they envision a bald man in robes; prostrating in front of a Buddha statue. And if they stretch their imaginations, Americans see the typical Buddhist as a college student, resting under a tree as they read the Dhammapada.

When people think of Buddhism, what they almost never see is poor people, hungry people, desperate people who are struggling to survive. But that's been the reality for practitioners of the Way going back to ancient times.

Buddha's mother died a week after his birth. Shinran Shonin lived in exile for most of his life. And Rev. Koyo Kubose was sent to a Japanese internment camp during World War 2.

Thus, the history of Buddhism isn't one of people sitting on beaches and college students reading books in the quad. The history of Buddhism is a history of pain. It's a history of people using their religious practice to survive war, famine, and pestilence. And the practice allowed them to not only survive these things but to come out stronger on the other end.

As Buddhists, we must remember this as we deal with Coronavirus.

Yes, it's scary. Yes, things are spiraling out of control. But we were built for this.

All of those hours spent sitting in meditation halls. The thousands of prostrations we did in front of the altar, the times we chose to go on a retreat instead of partying with friends; those choices prepared us for this moment.

We've spent years building up a core of spiritual resiliency, and we can call on that core in our moments of need. We have rituals in the way of chanting, bowing, and meditation that act as anchors; settling our minds when they're tossed about by worldly seas.

And we have our Dharma ancestors supporting us; holding us up from behind. They didn't fall in the face of adversity, and they won't let us fall either.

Yes, Coronavirus is strong. But we're stronger. And we will come out of this pandemic better than we were before; part of a long legacy of survivors that stretches back to ancient times.

Namu Amida Butsu

Get my new book, Perfectly Ordinary: Buddhist Teachings for Everyday Life

Click here to read a sample chapter of the book

Visit my YouTube channel to hear Dharma Talks

If you'd like to support my work, please consider making a donation

Don't be scared of Coronavirus. We were built for this

Published on March 21, 2020 16:03

March 16, 2020

Contemplating the Coronavirus

The first noble truth of Buddhism states life is suffering. I imagine Buddha chose to start there because life was terrible for most of the people he met.

The first noble truth of Buddhism states life is suffering. I imagine Buddha chose to start there because life was terrible for most of the people he met.Many of them lived hand-to-mouth; only one crop failure or failed hunt away from starvation. They had little to no legal recourse if a neighbor stole their property, and people died regularly from disease outbreaks.

So, when Buddha taught the first noble truth, he wasn't giving a philosophical treatise. He was naming and validating the lived experience of the people he ministered too. More than that, he was positioning Buddhism as a practical, proven method for dealing with the trauma in their lives.

This is important to remember as we cope with our own suffering. We like to imagine ourselves as the model with washboard abs, meditating on a beautiful beach. We want to be the perfect person, with the perfect life, and the perfect practice. But that's not reality

The truth is we don't practice Buddhism because life is easy. We practice because life is hard. We practice because we're human, because we hurt, because there are things in the world that scare us. We practice Buddhism so we can cope with things like the Coronavirus.

Of course, we must do all of the things that the Center for Disease Control recommends. We must wash our hands, stop touching our face, and self-isolate as best we can. But these steps don't heal our mental and spiritual distress. For that, a Buddhist contemplation practice like the one listed below can be useful.

First, it helps if we acknowledge the first noble truth. A lot has changed since that teaching was given 2,600 years ago. But a lot has stayed the same. In spite of our medical advancements, we're still of a nature to grow old, get sick and die.

If we accept that on an intuitive level as opposed to just knowing it intellectually, a lot of fear is removed from lives. This understanding helps us see the Coronavirus less as a scary aberration and more as part of the natural unfolding of life. Of course, that doesn't make it a pleasant part of life, but it does make it manageable.

Second, we can recognize the many ways that we're not suffering. For example, we're in the middle of a pandemic, but the electricity still works, clean water still comes out of our faucets, and employees at stores and restaurants across the country are still making sure that we're fed.

The Lotus Sutra tells us that there is an infinite number of Buddhas in the universe, and it's easy to forget that many of them work in the healthcare, infrastructure, and service industries. These brave individuals work tirelessly stocking supermarket shelves, treating the sick, and ensuring that our utilities function so that each of us can have a pleasant life.

As we sit at home under self-imposed quarantine, it's helpful to reflect on how much we benefit from their work, and how much worse our lives would be without them.

And this leads us to the final phase of our contemplation; gratitude. In times like this, it's easy to forget how much we have to be grateful for, but it's a long list. We have the food, shelter, and medicine that's provided by the Buddhas we discussed earlier.

Then there are the multiple modes of entertainment (books, movies, board games, etc.) that we can enjoy while we wait for things to blow over. There are the pets that keep us company, the family and friends that check in on us each day, and so much more.

The gratitude portion of the contemplation can go on for a long time if we let it. And that's the point; to remind us that even when we sit in darkness, we're surrounded by light.

Namu Amida Butsu

Get my new book, Perfectly Ordinary: Buddhist Teachings for Everyday Life

Click here to read a sample chapter of the book

Visit my YouTube channel to hear Dharma Talks

If you'd like to support my work, please consider making a donation

Contemplating the Coronavirus

Published on March 16, 2020 21:18

March 8, 2020

Buddhist Altars and the Oneness of All Things

When I became a Buddhist I was against the use of altars. In part, this was due to a youth spent in the evangelical Christian church; where we received daily warnings against false idols and eternal damnation.

When I became a Buddhist I was against the use of altars. In part, this was due to a youth spent in the evangelical Christian church; where we received daily warnings against false idols and eternal damnation.It was also due to the arrogance that's typical of most westerners, which writes off devotional Buddhist practices as "cultural baggage".

I believed in seated meditation and I enjoyed spending time on my cushion. But any outward show of faith whether it was an altar, a Buddha statue, or even wearing mala beads was too much for me to handle.

I wanted to keep Buddha and get rid of Buddhism.

However, years of practice have pushed me to the other end of the spectrum. I wear robes, I chant, I bow, and there is a Buddhist altar in my living room. This change occurred because hours in meditation showed me that Buddhism is as much a body-practice as it is an intellectual one. And like the adventurer who finds a hidden waterfall on a map, it's not enough for us to know the path to our destination. We have to lace up our boots and walk there.

My altar helps me walk. Most people would call it minimalistic, but each piece serves a purpose. At its center is a small Buddha statue that I bought the day I took the precepts. There is a Butsudan that was gifted to me the day I became a Buddhist teacher and candles that I use to make light offerings. Finally, there are two stones; one on either side of Buddha.

The one on his right is lemurian quartz and it represents Kannon, the bodhisattva of compassion. The one on his left is striated sandstone. It represents Monju, the bodhisattva of wisdom. I found the stones when I was in San Francisco doing an advanced meditation teacher-training.

So, one could say that my alar is an embodiment of my Buddhist life. Every piece represents a step I've taken along the path. Each piece also represents the people who've walked with me on that path. My altar reminds me of Buddha, who blazed the trail for others to follow. It reminds me of Kannon and Monju who act as guideposts when I've lost my way. And it reminds me of the members of my sangha who rush to pick me up every time I fall.

The practice of having an altar is the practice of remembering. We remember where we've come from. We remember where we're going. And we remember those who've walked the path before us.

The practice of having an alter is the practice of oneness. It's a practice that says there is no "me" without "we". And there is no "I" without "us". Thus, it embodies Eihei Dogen's teaching, which states, "To study the self is to forget the self. To forget the self is to become intimate with a myriad of things."

The practice of having an altar is the practice of speaking with our ancestors. I hear their voices every night when I bow and give an offering. They say, "You are not alone." They say. "Where you go, we go with you. Where you walk, we walk too."

Their words comfort me. The give me warmth when life is cold. And they remind me that when I sit before my altar, the entire world sits with me.

Namu Amida Butsu

Get my new book, Perfectly Ordinary: Buddhist Teachings for Everyday Life

Click here to read a sample chapter of the book

Visit my YouTube channel to hear Dharma Talks

If you'd like to support my work, please consider making a donation

Buddhist Altars and the Oneness of All Things

Published on March 08, 2020 17:08

March 4, 2020

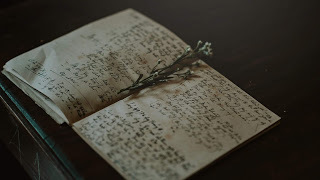

Cursive and the Koan of Life and Death

As a child, I used to get compliments on my handwriting. I'd be bent over my writing workbook with a furrowed brow, dotting my i's and crossing my t's when a teacher would walk over and say, "You have excellent penmanship, Alex".

As a child, I used to get compliments on my handwriting. I'd be bent over my writing workbook with a furrowed brow, dotting my i's and crossing my t's when a teacher would walk over and say, "You have excellent penmanship, Alex".The compliment was nice, but the best part came when I got a gold star on my homework. In grade school, gold stars were the bread and butter of life. They showed that you'd done something good. They showed that you were important. In grade school, a gold star meant that you had value. And I earned lots of stars.

But then my father brought a computer home one fateful day, and the world changed. Handwriting wasn't important anymore. Everything needed to be typed and double-spaced in order to get full points. So, I traded my ballpoint pen for a keyboard and never looked back.

By the time I entered college the inviting loops of my writing had been replaced with unintelligible scribbles. I'd call said scribbles "chicken-scratch" but that'd be praising them too highly. Suffice it to say, on the rare occasion I needed to write something out by hand I'd use print letters.

This lasted until recently when on a whim I took some notes in cursive, came back to them later, and realized that I couldn't read my own writing. The letters were stunted and smashed together to the point that it was hard to tell the r's from the m's. And I felt embarrassment grow in my chest.

So, I purchased a handwriting workbook for adults, and I've been slowly working my way through it; practicing my letters and writing out quotes from dead people. Surprisingly, I've found the practice to be meditative; requiring my full attention.

It's easy to write out twenty lowercase a's in a minute. But it's hard to write a single lowercase 'a' correctly; complete with the proper curves, angles, and accents.

If I rush to the end of an exercise, my letters become jumbled and small. If I worry about past mistakes, I forget the tiny flourishes that turn writing into an art. It's only when my focus is completely in this present moment that the letters take shape.

As I sit hunched over my workbook with a furrowed brow, writing in cursive requires me to take up space, allowing my w's to be as wide and loopy as they need to be. It requires me to pay attention so that my uppercase q's don't look like the number two. And it requires me to show special care when doing an exercise that no one else will see.

This bears many similarities to Zen. A central part of Buddhist practice is solving the koan of life and death. To put it another way, we all want to know how to live a good life and what happens when we die. The uncertainty around these questions has driven philosophers into madness, so they shouldn't be taken lightly.

Sadly, many Buddhist teachers are flippant in response to these inquiries. And while there's wisdom in saying, "Don't think about it so much," we're all human beings. And we all want to know if we'll get a gold star for a life well-lived.

I don't have an answer to the koan of life and death. But I do have an approach to the problem based on my experience with cursive. In order to write out a quote that's both legible and beautiful to look at, I first need to write out several words. And before I write out several words, I have to write out several letters; slowly and correctly.

There's a word for this in Japanese, menmitsu, which translates to loving attention. If I write each letter with menmitsu, giving loving attention to every stroke, the result is a piece of writing that's both good and beautiful to look at. And the same is true in the story of our lives.

Each day, we write a single letter in a book called, "The Life I Lived." We don't know how the book will end, but we can decide what today's letter will look like. If we're careful and attentive with our days, filling them with acts of kindness and generosity, they add up to beautiful paragraphs and stories; until we end up with a life that's both good and beautiful to look at.

But we can't rush to the end, wondering if we'll be rewarded when we die And we can't get bogged down in past mistakes. Rather, in order to live a good life, we need to keep our focus on this present moment; ensuring that we dot our i's and cross our t's.

Namu Amida Butsu

Get my new book, Perfectly Ordinary: Buddhist Teachings for Everyday Life

Click here to read a sample chapter of the book

Visit my YouTube channel to hear Dharma Talks

If you'd like to support my work, please consider making a donation

Cursive and the Koan of Life and Death

Published on March 04, 2020 18:36

February 25, 2020

Shoveling Manure on the Bodhisattva Path

When I wrote my book, Perfectly Ordinary: Buddhist Teachings for Everyday Life, there were several essays that I enjoyed writing, but they didn't quite make the cut.

When I wrote my book, Perfectly Ordinary: Buddhist Teachings for Everyday Life, there were several essays that I enjoyed writing, but they didn't quite make the cut. Some repeated lessons that I'd already taught in an earlier chapter and others didn't fit with the overall narrative.

I thought about saving them for a later project, but I'd rather put them out into the world, and see what happens. The following is one of the aforementioned essays. Enjoy.

When I was farming in New York, one of the jobs that Cindy, the farm owner, had me do was clean the chicken coops on a weekly basis. There's nothing glamorous about farm life, it's difficult, back-breaking work. But cleaning the coops was easily my least favorite part of the job.

Birds, unlike humans, don't have separate tracks for liquid and solid waste. It all comes out at once, from the same place. And for chickens, this results in a wet paste that is sticky and foul-smelling due to the high levels of ammonia. This isn't an issue when they do their business in an open field, but it causes problems when it happens in the coop.

So, we put straw on the floor of the coop to make the cleaning process easier, and once a week I had to go in with a shovel and a pitchfork, gather all of the soiled straw from the floor, place it into a wheel barrel, and put down fresh straw for them to destroy.

The fumes from their waste burned my eyes and throat to the point that sometimes I had to stop and go outside to get fresh air before restarting my work. But I was the low man on the totem pole, so this job was mine and mine alone.

It normally took several trips, but eventually, I would get everything into the compost pile. It was about 4 feet high and several feet long; a mix of manure, straw, and grass clippings. I'd use the pitchfork to mix the new manure in with whatever was already in the pile and then pull out the water hose to mist the pile lightly. Compost needs to be slightly damp for everything to break down completely.

Like I said, it was my least favorite job on the farm. Each time I did it my head ached, my back hurt and my boots smelled terribly for several days. But after three months of doing this consistently, we had a giant pile of nutrient-filled fertilizer that we used to grow strawberries and fruit trees.

Most people don't realize this, but whether it comes from chickens, cows, or pigs, there is a lot of manure involved in growing food. And unless some unlucky farm apprentice spends endless hours carrying animal waste around a farm, no one gets to eat.

I think about this a lot in regards to the Bodhisattva vows. In Mahayana Buddhism, we're taught that it's our job to realize enlightenment so that we can save other beings from suffering. It sounds good, but most people don't realize what's involved in that process. Simply put, it's not easy to walk the Bodhisattva path.

In the same way that farm apprentices must work skillfully with chicken poop in order to grow fruit trees. We, as Bodhisattvas-in-training, must work skillfully with suffering to make life better for ourselves and others. This is unpleasant work. It's painful, and we often don't see positive results right away. But if we work diligently with the suffering in our lives, a better world is the result.

We may not see the results of our work in the same way that I didn't see how all of my compost was used. But we can have faith that it will happen. In the same way that the hard work of Buddha, Shinran, Dogen, and countless others has reached through the centuries and touched our lives. Our practice will make a better world for everyone who comes after us.

The walk of the Bodhisattva is a walk of faith. A faith that says what we do matters. Each time we meditate, chant, or bow in front of our altars we turn the suffering of this world into joy.

At times, it can be challenging. But as long as we walk the path consistently, doing a little bit each day. Something beautiful will grow, and we'll all be better for it.

Namu Amida Butsu

Get my new book, Perfectly Ordinary: Buddhist Teachings for Everyday Life

Click here to read a free sample chapter of the book

Visit my YouTube channel to hear Dharma Talks!

If you'd like to support my work, please consider making a donation.

Shoveling Manure on the Bodhisattva Path

Published on February 25, 2020 19:19